Abstract

Background:

Alcohol use and misuse are prevalent on many college campuses. The current study examined participation in college environments where alcohol is present and being consumed. We documented students’ alcohol consumption, social abstaining (i.e., attending an alcohol-present event, but not drinking), and refusing invitations to drinking events. We tested for differences by parental education, immigrant status, race-ethnicity, and gender. We charted longitudinal change across college.

Methods:

First-year students attending a large public US university (n=681, 18% first generation college student, 16% first generation immigrant, 73% racial-ethnic minority group member, 51% women) were recruited and followed longitudinally for seven semesters. Each semester, students completed up to 14 daily surveys; responses were aggregated to the semester level (n=4,267).

Results:

Multi-level logistic regression models demonstrated that first generation college students were less likely to drink and refuse invitations to drinking events than students with a college educated parent (AORs .66, .72, respectively). Similarly, first generation immigrants were less likely to drink, socially abstain, and refuse invitations (AORs .58-.73). Compared to White students, Black and Asian American students were less likely to drink (AORs .55, .53) and refuse invitations to drinking events (AORs .68, .66). The proportion of days spent drinking increased across college and refusing invitations was the most common at the start and end of college.

Conclusion:

First generation college students, first generation immigrant students, and Black and Asian students participated less in pro-drinking environments during college. These findings indicate that on drinking and non-drinking days students’ participation in alcohol-present situations differed by background. Furthermore, our results indicate that the students who are most likely to refuse invitations to drinking events are the same students who drink most frequently.

Keywords: college, abstain, immigrant, first generation, longitudinal

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol is often considered to be a central part of the college experience in the United States (Colby et al., 2009; Russell and Arthur, 2016). When students consume alcohol, they may have fun, relieve stress, expand social networks, or experience other positive consequences (Barnett et al., 2014; Maggs, 1997; Park, 2004). At the same time, heavy drinking can be detrimental: short-term negative consequences include vomiting or blacking out and long-term consequences include assault, severe injury, and even death (White and Hingson, 2013). Considering these consequences, understanding contact with and participation in “wet” prodrinking environments is important. In wet environments, alcohol is readily available and some (or all) participants consume alcohol. Across college, students may have different levels of contact with these environments. First, on some occasions they may drink alcohol at a particular location. Second, they may attend activities or events where others are drinking, but abstain themselves (i.e., social abstaining). Third, they may receive invitations to wet events, but decline to attend them and abstain.

Although most college students consume alcohol some of the time, on the vast majority of days, students abstain (Maggs et al., 2011; Neal and Fromme, 2007; Simons et al., 2014). Whether students drink alcohol or abstain may depend on individual characteristics and preferences as well as social contextual factors. For instance, students may abstain because they lack a desire to drink or because they have no one with whom to drink (O’Hara et al., 2014). Students may also abstain because no one invited them to a drinking event. Certainly, students can drink alone, but most drinking during college occurs in social settings (Simons et al., 2005) and consumption is related to attendance at alcohol-present parties. A study of college students at one university found that when students attended a party where alcohol was served, about three fourths of them consumed alcohol that night. Furthermore, attendees at these alcohol-present parties consumed a higher number of drinks than their typical number (Wei et al., 2010).

Examining access to and engagement with social drinking environments during college provides a glimpse into students’ daily social-environmental contexts. Furthermore, whether students attend, decline, or are not invited to drinking events may have implications for their health and well-being. Social abstaining involves a student attending drinking events, but not drinking. Social abstainers may, therefore, gain benefits associated with social interaction (e.g., establishing or maintaining social ties) and they may experience higher quality interactions or improved memory compared to drinkers (Conroy and Visser, 2018). Individuals who receive but decline invitations to drinking events may avoid undesirable peer models of health behaviors and peer pressure to drink (Borsari and Carey, 2001). They also reduce their exposure to secondary effects of alcohol consumption (i.e., negative consequences resulting from other people’s heavy drinking) (Wechsler et al., 1996; Yu, 2001). Nonetheless, being invited may signal that an individual is well-liked or part of a larger social group in which drinking is the norm. Thus, compared to other students, these invited students are more integrated into pro-drinking aspects of the college social environment.

Social location and wet college environments

Contact with social drinking peers and situations in college may vary by student demographic characteristics. Social class, ethnicity (including country of origin and subjective racial identification), and gender are “primary social divisions involving distinctive relations of differentiation and stratification” (Anthias, 2013, p. 846). These divisions may shape daily experiences and participation in wet college environments. For example, first generation college students—those whose parents did not graduate from college—may spend more time in paid employment (Greene and Maggs, 2014) and thus have less available time for drinking alcohol or attending alcohol-present parties. Prior work has indicated that young people from more educated families with higher incomes were more likely to consume alcohol and binge drink than those from less advantaged backgrounds (Humensky, 2010; Patrick et al., 2012). Variation has also been documented by immigrant status and race-ethnicity. Immigrant young people are more likely to abstain and less likely to binge drink than their native born counterparts (Greene and Maggs, 2018), perhaps partially as a result of immigrants’ lower affiliation with substance using peers (Bacio et al., 2013). In addition, White adolescents are more likely to drink alcohol and binge drink than other racial-ethnic groups (Johnston et al., 2017) and college attendance is positively associated with alcohol consumption for Whites, and inversely associated with consumption among Blacks and Asians (Paschall et al., 2005). Importantly, race-ethnicity and immigrant status are correlated in the US, but many studies exploring racial differences do not account for immigrant status. Including immigrant status may partially explain racial-ethnic differences between Whites and groups such as Asian Americans (Iwamoto et al., 2016b, 2016a). In terms of gender, national data suggest that male college students are more likely to drink daily than females and slightly more likely to have consumed alcohol in the past 30 days (Johnston et al., 2013).

Yet, it is important to note that extant work has typically focused on drinking alcohol only; little work has tested whether social abstaining or refusing invitations to drink vary across these demographic groups. One study examined party attendance on a college campus and found that Blacks and Asians attended fewer parties with alcohol available than White students, but men and women did not differ in their alcohol-present party attendance (Wei et al., 2010). Thus, it is possible that the frequency of social abstaining or refusing invitations to alcohol-present parties varies for different demographic groups. Patterns for social abstaining and refusing invitations to drinking events might mirror those for drinking alcohol because social abstaining and refusing invitations indicate more contact with wet environments. Alternatively, the opposite pattern could emerge with individuals from demographic groups who drink less frequently engaging in more social abstaining and refusing more invitations to drinking events.

Change over time in drinking, social abstaining, and refusing invitations

Contact with social drinking environments may change over time because of developmental and interpersonal changes. Alcohol use frequency increases across college (Arria et al., 2016), with binge and high intensity drinking peaking around age 21/22 and declining thereafter (Patrick et al., 2016). Although little work has examined changes in social abstaining or refusing invitations, it is possible that they may change over time as well. For instance, the frequency of social abstaining during college might decline in tandem with increases in drinking frequency. The frequency of refusing invitations might also change as peer networks develop from “relationships of convenience” to tight knit social groups (Maunder et al., 2013). Self-selection into peer groups may result in fewer declined invitations over time because peers know one another better and thus are less likely to extend drinking invitations to those who are unlikely to accept (e.g., abstainers). Exploring these circumstances longitudinally is necessary to identify whether and how participation in wet drinking environments changes over time. Furthermore, testing whether trajectories are similar across groups is necessary to understand if any documented demographic differences are maintained longitudinally as students progress through college.

Current study

There is a dearth of research examining students’ contact with alcohol-present contexts and situations on their abstaining days. For example, little is known about whether students attended a party with alcohol – or were invited to one and declined – on their nondrinking days. The current study contributes to the literature by examining demographic correlates and longitudinal change in alcohol use, social abstaining, and declined invitations. Using a sample diverse with regard to race-ethnicity and nativity status, we empirically identify demographic characteristics of individuals who were most likely to socially abstain and decline invitations. In particular, we tested whether first generation college student status, first generation immigrant status, race-ethnicity, and gender were associated with each circumstance (aim 1). Furthermore, assessing these behaviors repeatedly over seven semesters using a measurement burst design enabled us to document longitudinal change across college (aim 2) and examine whether any demographic disparities were maintained across the college years (aim 3). Understanding social abstaining and declined invitations, in tandem with drinking behavior, is critical for understanding the ways in which alcohol touches the lives of college students. Indeed, social abstaining may increase risk for experiencing secondary alcohol-related consequences through contact with excessive drinkers (Wechsler et al., 1996), but it also is a protective behavioral strategy promoted by some interventions (Lewis et al., 2018). Declined invitations deserve attention because they shed light on the occasions when individuals were given a clear opportunity to drink, but chose to abstain. Declining invitations also has been promoted by some behavioral interventions, but little research has examined the frequency with which students socially abstain or decline invitations to alcohol-present events and instead opt for alcohol-free activities. Thus, the current study contributes to the literature by documenting correlates of social abstaining and declined invitations during college and describing whether patterns contrast with or mirror those of alcohol use.

METHODS

Data

The current study used longitudinal data from the University Life Study (ULS) (Greene and Maggs, 2014; Patrick et al., 2014). Briefly, a sample of college students attending a northeastern US university was recruited during students’ first semester of college. Eligible participants were US citizens or permanent residents who lived within 25 miles of campus and were under age 21 in Semester 1. Drawing from university registrar information, participants were identified using a stratified random sampling design with replacement (by gender and the four largest US racial-ethnic groups on campus). Participants (N=744 at Semester 1) were followed longitudinally for up to seven semesters (82% were retained at Semester 7). Each semester, students completed a semester survey (approximately 30 minutes in length) as well as 14 shorter consecutive daily surveys reporting on their alcohol consumption, activities, and other experiences that day. Thus, each participant completed up to 7 semester surveys and 98 daily surveys. The multi-leveling modeling strategy allowed for incomplete data at level 1 (days); participants could have missed some days and/or some semesters, but still be included in analyses. All surveys were online and links for the daily survey were sent at about 4am so that participants reported on their previous day’s activities.

The analytic sample for the current paper focused on participants with valid information on demographic variables of interest. Students who were missing data on immigrant status (collected in semesters 2 and 3, n=52), parent education (n=10), and/or did not provide any daily information (n=1) were excluded. Logistic regression analyses suggested that excluded students did not differ systematically from the analytical sample in terms of gender, race-ethnicity, parental education, or parental marital status (ps > .05). Of the final sample of 681 students, about half were female (51.1%) and 71.8% had a parent with a bachelor’s degree. In terms of immigrant status, 16.2% were foreign-born and 83.9% were US-born. Finally, 25.7% were Latinx or Hispanic American, 15.6% were non-Latinx (NL) Black or African American, 27.0% were European American (NL), 22.9% were Asian American (NL), and 8.8% were multi-racial (NL).

Measures

Dependent variables.

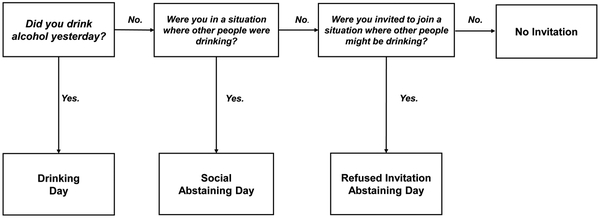

Three dichotomous variables indicated students’ participation in the college drinking environment; each was assessed daily and aggregated to the semester level. Drinking days were coded as days students consumed any alcoholic drinks (1=1 or more drinks, 0=no drinks). Social abstaining days were non-drinking days when participants reported that they had attended a situation where other people were drinking, but did not consume alcohol themselves (1=yes, 0=no). Refused invitation abstaining days were non-drinking days when students did not attend a drinking event, but were invited (1=yes, invited and declined; 0=not invited). From these responses, we calculated the proportion of days that participants experienced each circumstance in each semester. Figure 1 presents a flow chart describing the logic of the nested pattern of questions and response options. Whereas alcohol use was assessed on every daily survey, social abstaining was only queried on abstaining days, and whether someone had been invited was only asked when participants neither consumed alcohol nor attended a drinking event. Therefore, analyses comparing drinking days to non-drinking days include all days that participants had valid data about alcohol use. Analyses comparing social abstaining days to other (non-social) abstaining days include all abstaining days in the analysis. And finally, the third analysis includes all abstaining days that participants did not attend a drinking event. For these analyses, the days when individuals received an invitation (but declined it) were compared to the days that individuals received no invitation.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for Drinking Days, Social Abstaining Days, and Refused Invitation Abstaining Days.

Background characteristics.

First-generation college student. A dichotomous indicator captured whether the student had a parent with a bachelor’s degree (1 = no, 0 = yes). First-generation immigrant. We distinguished students who were native born (i.e., born in the United States) from those who were foreign born (i.e., born in another country; first-generation immigrants) (US Census Bureau, 2016). Race-ethnicity was coded into five categories based on self-reported responses to two race-ethnicity questions suggested by the National Institutes of Health. Participants were categorized as Latinx or Hispanic (regardless of race), White non-Latinx (NL), Black NL, Asian or Hawaiian Pacific Islander NL, and multi-racial NL. White NL is the reference category to which the other groups are compared. In addition, participants were asked to identify their gender as either male (coded 1) or female (coded 0).

Semester.

Semester in college (the time trend) was coded from 1 to 7 and centered.

Analytical strategy

To address aim 1, we began with descriptive data exploration, examining whether drinking days, social abstaining, and invitation days varied by parental education, immigrant status, race-ethnicity, and gender. Subsequently, we computed a series of multilevel logistic regression models in which semester (Level 1) was nested within individuals (Level 2). Multi-level modeling was chosen as an ideal method given the clustered nature of the data and resulting correlated standard errors (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002; Singer and Willett, 2003). Stata’s melogit command was used and the data were specified as binomial; that is, we predicted the number of days spent in each context given the number of possible days that a participant could experience each. To address aim 2, we began by descriptively examining longitudinal change in the three outcomes by graphing the means by semester. We tested a series of polynomial models and included fixed effects for linear, quadratic, or cubic functions based on Wald test p-values. Given the possibility that there might be individual differences in change over time, we included a random slope for time if it improved model fit as indicated by a change in deviance (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002). To examine whether disparities across social location were maintained across the college semesters, we conducted a series of models interacting our demographic variables of interest and the linear time trend (i.e., semester in college).

RESULTS

Demographic predictors.

Across semesters and students, 13.7% of days were drinking days, 5.4% were social abstaining days, and 5.5% were refused invitation abstaining days. Therefore, on most days (75.4%) students did not drink, attend a drinking event, or get invited to one. Because of the sequential survey questions, students could only socially abstain if they did not drink on a given day. Of abstaining days, 6.8% were social abstaining days. Furthermore, of non-drinking days that students did not attend a drinking event, 8.1% were days students had been invited to a drinking event.

Table 1 presents the proportion of relevant days that participants drank, engaged in social abstaining, or refused invitations to drinking events. The proportions suggest that exposure to these situations varied by demographic characteristics. Multi-level multivariate logistic regressions (Table 2) indicated that first generation college students were less likely to drink alcohol and receive (and turn down) invites to drinking events than students with a college-educated parent. Immigrant students were less likely than US-born students to drink and socially abstain. On days that they did not drink or attend drinking events, they were also less likely than their US-born counterparts to receive a drinking invitation. In addition, compared to Whites, Blacks were less likely to drink alcohol and to refuse invitations to drink. Likewise, Asian American students were less likely to drink, socially abstain, and refuse invitations to drinking events than Whites. Male students were less likely to refuse invitations to drinking events than female students.

Table 1.

Proportion of Days Spent Drinking, Social Abstaining, and Refusing Invitations

| Drinking Daysa |

Social Abstaining Daysb |

Refused Invitation Abstaining Daysc |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Education | |||

| Parent has Bachelor’s Degree (BA) | 0.149 | 0.069 | 0.085 |

| 1st Generation College (no parent BA) | 0.105 | 0.065 | 0.066 |

| Immigrant Status | |||

| US-born | 0.145 | 0.072 | 0.084 |

| 1st Generation Immigrant | 0.093 | 0.049 | 0.058 |

| Race-Ethnicity | |||

| White, NLd | 0.161 | 0.078 | 0.086 |

| Black, NL | 0.097 | 0.061 | 0.068 |

| Latinx | 0.161 | 0.075 | 0.096 |

| Asian or HPIe, NL | 0.102 | 0.047 | 0.058 |

| Multiracial, NL | 0.149 | 0.084 | 0.091 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 0.138 | 0.065 | 0.097 |

| Male | 0.136 | 0.071 | 0.061 |

Proportion of valid diary days that students drank.

Proportion of abstaining days that students attended drinking events.

Proportion of abstaining days that students did not attend a drinking event, but were invited to attend.

NL=not Latinx.

HPI=Hawaiian Pacific Islander

Table 2.

Multi-level Models of Demographic Factors Predicting Drinking, Social Abstaining, and Refused Invitation Abstaining Days

| Drinking Days | Social Abstaining Daysa |

Refused Invitation Abstaining Daysb |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| eβ | eβ | eβ | |

| Fixed Effects | |||

| 1st Generation College Student | 0.656*** (0.082) |

0.942 (0.098) |

0.724* (0.096) |

| 1st Generation Immigrant | 0.579*** (0.094) |

0.728* (0.100) |

0.609** (0.106) |

| Black, NLc | 0.551*** (0.099) |

0.861 (0.128) |

0.683* (0.129) |

| Latinx | 1.264 (0.190) |

1.103 (0.139) |

1.284 (0.203) |

| Asian-HPId, NL | 0.527*** (0.087) |

0.599*** (0.084) |

0.658* (0.115) |

| Multiracial, NL | 0.777 (0.166) |

0.959 (0.171) |

0.995 (0.223) |

| Male | 0.906 (0.100) |

0.921 (0.085) |

0.547*** (0.064) |

| Random Effects | |||

| Variance in Semester Slope | 0.050*** (0.006) |

0.039*** (0.007) |

0.050*** (0.008) |

| Variance in Individual-Level Intercept | 1.722*** (0.128) |

1.093*** (0.093) |

2.038*** (0.167) |

| Covariance Slope and Intercept | -0.015 (0.022) |

0.086*** (0.020) |

0.173*** (0.033) |

| N (semester) | 4267 | 4267 | 4267 |

| N (person) | 681 | 681 | 681 |

Proportion of abstaining days that students attended drinking events.

Proportion of abstaining days that students did not attend a drinking event, but were invited to attend.

NL=not Latinx.

HPI=Hawaiian Pacific Islander.

Notes: Although the number of days used to calculate the proportions varies, because the outcome is the proportion of days in each semester for each person, the semester sample size is consistent across models. Fixed effects coefficients are exponentiated; Standard errors are in parentheses. The reference category for race/ethnicity is White, NL. Models additionally control for the time trend.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Change over time.

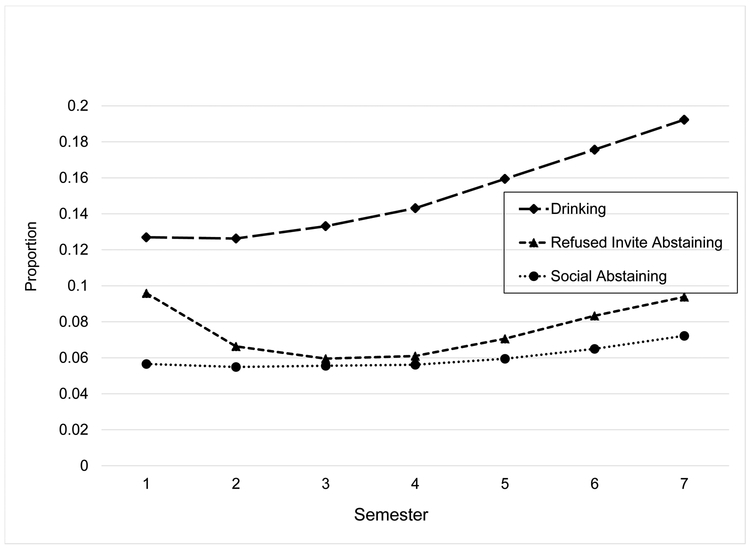

Next, we examined change over time for each of the three outcomes (aim 2). Significant random slopes indicated individual differences in change over time. On average, a cubic time trend fit the data best for drinking and for refused invitations whereas a linear time trend captured change in social abstaining. From these models, we calculated the predicted proportion of days spent in each situation across college (see Figure 2). Drinking days demonstrated noticeable change with the steepest increases in the middle semesters of college. The likelihood of receiving an invitation on non-drinking/non-attending days decreased after semester 1 and then increased slightly toward semester 7. Although statistically significant, changes in refused invitation abstaining days and social abstaining days were quite small and thus, may not be substantively meaningful.

Figure 2.

Change Across College in the Proportion of Days Students Spent Drinking, Social Abstaining, and Refused Invitation Abstaining. Drinking days are the proportion of valid diary days that students drank. Social abstaining days are the proportion of abstaining days that students attended drinking events. Refused invitation abstaining days are the proportion of abstaining days that students did not attend a drinking event, but were invited to attend.

The third aim was to test whether there were demographic differences in change over time in our outcomes. The results indicated that, for drinking and social abstaining, there were not many significant interactions between time (i.e., semester in school) and our demographic variables of interest. However, a few interactions deserve note regarding refused invitation abstaining days. A significant Race × Linear time interaction showed that the likelihood of receiving an invitation decreased more quickly among Asian students than White students (i.e., Asian students were even less likely to get invited to drinking events on their nondrinking/non-attending days as they progressed through college compared to White students, further widening the gap between these two groups). In addition, there was a Gender × Linear time interaction in which the gender difference in refused invitations increased. As they progressed through college, men were even less likely to turn down invitations to drinking events and more likely to not be invited than their female counterparts.

DISCUSSION

The current study explored the likelihood with which a sample of college students drank alcohol, attended drinking events but did not drink, and refused invitations to drinking events. Our results indicated that on the vast majority of days—about 75%—college students did not experience any of these situations. That is, most of the time students did not drink, nor did they attend—or get invited to—a situation where others were drinking.

Nonetheless, there were striking findings linking participation in drinking environments with demographic characteristics. Indeed, we found that first generation college students—students who did not have a parent who graduated from college—were less likely to drink and less likely to get invited to drinking events. First generation immigrants likewise had fewer opportunities for drinking. They were less likely to drink, less likely to socially abstain, and less likely to get invited and turn down invitations to drinking events on their non-attending days. Rather, immigrants were much more likely to abstain and not get invited. Black and Asian American students were less likely to drink and get invited to drinking events than White students. Taken together, our results indicated that the people who were more likely to socially abstain and refuse invitations to drinking events were the same individuals who were more likely to drink alcohol. Although this may seem like a paradox, this pattern of findings may occur because all three outcomes indicate some degree of immersion in wet environments. It seems that invitations to drinking events—whether they are accepted or not—are most likely to be extended to those individuals who drink more frequently (i.e., White, US-born students who have a college educated parent). These individuals may have accepted invitations and consumed alcohol at similar events previously. Alternatively, or in addition, they may be perceived by other students as being more likely to be interested in drinking. Thus, they are more likely to get invitations to alcohol-present events even though sometimes they may socially abstain at these events or decline to attend them.

Alcohol use and participation in pro-drinking culture during college may be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, participation in the drinking environment places students at risk for primary alcohol consequences (in the case of drinking) or secondary alcohol consequences (in the case of both drinking and social abstaining). On the other hand, alcohol is viewed by many as an integral part of the college experience (Colby et al., 2009; Russell and Arthur, 2016). Alcohol consumption can signify higher social status among adolescents (Kramer and Vaquera, 2011) and attending parties with alcohol can enable college students to build social networks and gain social capital, not just get drunk (Buettner and Debies-Carl, 2012). As Keeling (2000) noted, college student binge drinking is “rooted in the inertia of social and economic forces that reinforce class differences and delineate the dynamics of privilege (p.196).” This is not to say that students should be encouraged to participate more in the drinking culture dominant on many college campuses. Instead, there can be an expanded social space protected from the heavy drinking culture that enables students to gain the social benefits associated with drinking, but avoid the accompanying risks.

For students who were less integrated into drinking environments, we do not know whether they were discriminated against (i.e., not invited because of perceived interests or aspects of their background) or whether they may have had stronger social ties with non-drinking friends and thus did not attend/get invited to drinking events because they and their friends were involved in other rewarding events and activities. College students tend to form friendships with people similar to themselves (Stearns et al., 2009), and somewhat paradoxically, the diversity and number of students at large universities affords students the opportunity to self-select into more homogenous friendship groups than they would at smaller universities (Bahns et al., 2012). Thus, at the current large public university, students may have been excluded from drinking environments or they may have been self-selecting into different social groups.

Some findings for gender were surprising. Men and women did not differ in their likelihood of drinking or social abstaining. These findings correspond to research documenting a gender convergence in drinking patterns in the US (Dawson et al., 2015; Keyes et al., 2008; White et al., 2015). The current study only documented gender differences in refusing invitations. Women refused more invitations than men and this gap widened during college. Although we do not know why, this finding may result from women receiving more invitations—both accepted and refused. Gendered scripts may make it more likely that male students invite female students (rather than the reverse) to alcohol-present parties. In addition, females may prefer attending drinking events in large groups to prevent unwanted alcohol-related consequences such as sexual violence or to avoid scrutiny/surveillance of drinking behaviors that are perceived as violating gender norms (Armstrong et al., 2006; MacNeela and Bredin, 2011; Peralta, 2007). Thus, just as college women “round up” their friends to smoke together (Nichter et al., 2006), similarly, they may be extending many drinking invitations to their female friends resulting in many refused invitations.

Participation in the wet college environment changed somewhat across the college years. The proportion of days that students spent drinking increased substantially as students progressed through college, in line with previous research on college student drinking (Arria et al., 2016). Refused invitation abstaining days were most common during the first semester; their likelihood decreased during the middle semesters. Although we do not know the reasons for these changes, perhaps the higher number of refused invitations at the start of college resulted from exposure to new peers with different drinking patterns, who extend invitations. Peer influence is a reciprocal relationship between selection and socialization processes (Brechwald and Prinstein, 2011; Rulison et al., 2015). At the start of college, certain relationships—such as the relationship with an assigned roommate—may be more heterogeneous. Over time, friendships may become closer and friends may become more similar in their attitudes, interests, and behaviors, including drinking patterns. This may result in fewer invitations that are subsequently declined.

Limitations of this study should be noted. As a result of survey branching, the current study examined social abstaining on nondrinking days and declined invitations on days when students were not at an alcohol-present event. Because the number of drinking days varied across demographic groups, some groups received the questions about social abstaining and invitations on more days, on average, than others. However, drinking days were not common in general (<15% of all days) and therefore participants from all demographic backgrounds had many abstaining days available for analysis. Nonetheless, concern about skip patterns led us to create and predict proportions. The use of proportions allowed us to adjust for the fact that some students received questions about social abstaining/invitations more frequently than others. Furthermore, to examine the robustness of results, we conducted specification tests. We computed supplemental models that changed the denominator of the proportion to be the total number of days the person responded; that is, the supplemental models did not account for the skip patterns. The results from these specification tests were consistent with those presented in the manuscript. Whether or not a control for drinking frequency was included, inferences were similar.

Because of the skip patterns, we could not explore how students combined drinking, social abstaining, and declining initiations on the same day. Students may experience two or three of these contexts on the same day (i.e., they may consume alcohol at one party, but socially abstain at another). Future research should examine how these contexts overlap on drinking days and contrast experiences on drinking and nondrinking days. For instance, when attending a party, there may be a stark difference between sober social abstaining and intoxicated social abstaining (with the latter resulting from previous alcohol consumption earlier that day/evening). Similarly, exploring how students combine these contexts across days will be important. For instance, students who socially abstain or turn down invitations to drink on some days may be the same students who binge drink on other days.

The surveys were also limited because they did not assess broader social participation or invitations to non-drinking social events; thus we do not know the amount of social contact that participants had with situations where no alcohol was present. In addition, the surveys did not assess peer alcohol use and thus we cannot examine whether it explains any of the current findings. Finally, our results reflect the experiences of diverse students from one large predominantly-White public university in the northeast of the US; the extent to which the findings generalize to students in other settings or at other institutions is unknown.

Implications and Future Directions

Our findings help to expand what is currently known about opportunities to drink alcohol and the various ways that alcohol touches the lives of students. Similar to previous work, our data emphasize that on most days students abstained. However, we add to literature by demonstrating that on most days students not only abstained, but also did not attend or get invited to situations where others were drinking. These results contradict the stereotype of college as a never-ending party with free-flowing alcohol, which is especially noteworthy given that the sampled university was known for its party culture.

Our results further contribute to the literature by identifying characteristics of social abstainers and individuals who decline invitations to drinking events. The demographic predictors of these contexts paralleled predictors of alcohol use; thus our results demonstrated that White, US-born children of college educated parents were in contact with alcohol more than others, even when they were abstaining. Because social abstainers are at risk of secondary harms associated with alcohol consumption, they could be targeted by prevention programs. Social abstainers could be armed with information about how to minimize their experienced secondary consequences, taught harm reduction strategies, and informed of relevant campus and city alcohol-related policies (e.g., medical amnesty policies), because these students might be uniquely positioned to intervene to reduce alcohol-related harms among their peers.

Furthermore, if encouraging social abstaining and declining invitations reduces alcohol consumption or negative consequences, then prevention and intervention programs could promote both behaviors. Brief interventions often provide individual advice on reducing heavy drinking and promoting moderation through the use of protective behavioral strategies. Although definitions of protective behavioral strategies vary (Pearson, 2013), some scales assessing the construct include items related to social abstaining or declining invitations (Novik and Boekeloo, 2011; Sugarman and Carey, 2007). Interventions have included related strategies as well. For instance, work by Lewis and colleagues (2018) explored using text messages about alcohol-related protective behavioral strategies to reduce alcohol use; some of the items related to social abstaining and declining invitations (e.g., encouraging students to “Carry around a cup…with something other than alcohol in it” or “Have a plan for alcohol-free alternatives”). More work is needed to understand whether and when social abstaining and declining invitations can provide the benefits of drinking alcohol (e.g., feeling good; having fun; promoting social connection and expanded social networks) and minimize the risks.

Our work is an important first step using detailed daily data, but much more work is needed on this topic. Future research could explore student perceptions of contact with wet college environments. Some students might prefer more contact, but lack invitations or have conflicting obligations. Others might prefer less contact and desire greater access to other engaging, social leisure opportunities. Understanding why students engage in social abstaining, whether they experience secondary alcohol effects, and how social abstainers are perceived by others will also be important next steps.

The current study is one of the first comprehensive explorations of how social abstaining and refused invitations to drinking events are patterned across people and semesters in college. The daily diary design gave us detailed information about drinking as well as attending and receiving invitations to drinking events and we documented trajectories across seven college semesters spanning four years. The diverse sample enabled us to explore differences across demographic groups that are often understudied in the literature on alcohol use during the transition to adulthood (e.g., immigrant students, Asian American students). Our results underscore the reality that on both drinking and abstaining days, contact with the college drinking environment is patterned by parental education, immigrant status, and/or race-ethnicity.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R03AA024539 and R01AA016016. The National Institutes of Health had no role in data collection, analysis or interpretation. Similarly, they had no role in the writing of the report and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Kaylin M. Greene, Department of Sociology and Anthropology; Montana State University.

Jennifer L. Maggs, Department of Human Development and Family Studies; The Pennsylvania State University.

REFERENCES

- Anthias F (2013) Hierarchies of social location, class and intersectionality: Towards a translocational frame. Int Sociol 28:121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong EA, Hamilton L, Sweeney B (2006) Sexual assault on campus: A multilevel, integrative approach to party rape. Soc Probl 53:483–499. [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Allen HK, Vincent KB, Bugbee BA, O’Grady KE (2016) Drinking like an adult? Trajectories of alcohol use patterns before and after college graduation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40:583–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacio GA, Mays VM, Lau AS (2013) Drinking initiation and problematic drinking among Latino adolescents: Explanations of the immigrant paradox. Psychol Addict Behav 27:14–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahns AJ, Pickett KM, Crandall CS (2012) Social ecology of similarity: Big schools, small schools and social relationships. Group Process Intergroup Relat 15:119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Clerkin EM, Wood M, Monti PM, O’Leary Tevyaw T, Corriveau D, Fingeret A, Kahler CW (2014) Description and predictors of positive and negative alcohol-related consequences in the first year of college. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 75:103–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB (2001) Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. J Subst Abuse 13:391–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechwald WA, Prinstein MJ (2011) Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. J Res Adolesc 21:166–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettner CK, Debies-Carl JS (2012) The ties that bind: Bonding versus bridging social capital and college student party attendance. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 73:604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SM, Colby JJ, Raymond GA (2009) College versus the real world: Student perceptions and implications for understanding heavy drinking among college students. Addict Behav 34:17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy D, de Visser RO (2018) Benefits and drawbacks of social non-drinking identified by British university students. Drug Alcohol Rev 37:S89–S97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Grant BF (2015) Changes in alcohol consumption: United States, 2001–2 to 2012–13. Drug Alcohol Depend 0:56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene KM, Maggs JL (2018) Immigrant paradox? Generational status, alcohol use, and negative consequences across college. Addict Behav 87:138–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene KM, Maggs JL (2014) Revisiting the time trade-off hypothesis: Work, organized activities, and academics during college. J Youth Adolesc 44:1623–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humensky JL (2010) Are adolescents with high socioeconomic status more likely to engage in alcohol and illicit drug use in early adulthood? Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 5:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto DK, Grivel MM, Cheng AW, Zamboanga BL (2016a) Asian American and white college students’ heavy episodic drinking behaviors and alcohol-related problems. Subst Use Misuse 51:1384–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto DK, Kaya A, Grivel M, Clinton L (2016b) Under-researched demographics: Heavy episodic drinking and alcohol-related problems among Asian Americans. Alcohol Res Curr Rev 38:17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM (2013) Monitoring the future: Questionnaire responses from the nation’s high school seniors, 2011. Ann Arbor, MI, Institute for Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE (2017) Demographic subgroup trends among adolescents in the use of various licit and illicit drugs 1975–2016 (Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No. 88). Ann Arbor, MI, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling RP (2000) The political, social, and public health problems of binge drinking in college. J Am Coll Health 195–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS (2008) Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend 93:21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer RA, Vaquera E (2011) Who is really doing it? Peer embeddedness and substance use during adolescence. Sociol Perspect 54:37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Cadigan JM, Cronce JM, Kilmer JR, Suffoletto B, Walter T, Lee CM (2018) Developing text messages to reduce community college student alcohol use. Am J Health Behav 42:70–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeela P, Bredin O (2011) Keeping your balance: Freedom and regulation in female university students’ drinking practices. J Health Psychol 16:284–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL (1997) Alcohol use and binge drinking as goal-directed action during the transition to postsecondary education In: Health Risks and Developmental Transitions during Adolescence , pp 345–371. New York, NY, US, Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Williams LR, Lee CM (2011) Ups and downs of alcohol use among first-year college students: Number of drinks, heavy drinking, and stumble and pass out drinking days. Addict Behav 36:197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder RE, Cunliffe M, Galvin J, Mjali S, Rogers J (2013) Listening to student voices: student researchers exploring undergraduate experiences of university transition. High Educ 66:139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Fromme K (2007) Event-level covariation of alcohol intoxication and behavioral risks during the first year of college. J Consult Clin Psychol 75:294–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichter M, Nichter M, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Flaherty B, Carkoglu A, Taylor N (2006) Gendered dimensions of smoking among college students. J Adolesc Res 21:215–243. [Google Scholar]

- Novik MG, Boekeloo BO (2011) Dimensionality and psychometric analysis of an alcohol protective behavioral strategies scale. J Drug Educ 41:65–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara RE, Armeli S, Tennen H (2014) College students’ daily-level reasons for not drinking. Drug Alcohol Rev 33:412–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL (2004) Positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students. Addict Behav 29:311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Bersamin M, Flewelling RL (2005) Racial/Ethnic differences in the association between college attendance and heavy alcohol use: a national study. J Stud Alcohol 66:266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Maggs JL, Lefkowitz ES (2014) Daily associations between drinking and sex among college students: A longitudinal measurement burst design. J Res Adolesc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM, Kloska DD, Schulenberg JE (2016) High-intensity drinking among young adults in the United States: Prevalence, frequency, and developmental change. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40:1905–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Wightman P, Schoeni RF, Schulenberg JE (2012) Socioeconomic status and substance use among young adults: A comparison across constructs and drugs. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 73:772–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR (2013) Use of alcohol protective behavioral strategies among college students: A critical review. Clin Psychol Rev 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralta RL (2007) College alcohol use and the embodiment of hegemonic masculinity among European American men. Sex Roles 56:741–756. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS (2002) Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Rulison K, Patrick ME, Maggs J (2015) Linking peer relationships to substance use across adolescence. Oxf Handb Adolesc Subst Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Russell LD, Arthur T (2016) “That’s what ‘college experience’ is”: Exploring cultural narratives and descriptive norms college students construct for legitimizing alcohol use. Health Commun 31:917–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Oliver MNI, Bush JA, Palmer MA (2005) An experience sampling study of associations between affect and alcohol use and problems among college students. J Stud Alcohol 66:459–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Wills TA, Neal DJ (2014) The many faces of affect: A multilevel model of drinking frequency/quantity and alcohol dependence symptoms among young adults. J Abnorm Psychol 123:676–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB (2003) Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Stearns E, Buchmann C, Bonneau K (2009) Interracial friendships in the transition to college: Do birds of a feather flock together once they leave the nest? Sociol Educ 82:173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman DE, Carey KB (2007) The relationship between drinking control strategies and college student alcohol use. Psychol Addict Behav J Soc Psychol Addict Behav 21:338–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau (2016) Foreign-born Population. Available at: https://www.census.gov/topics/population/foreign-born/about.html Accessed May 30, 2017.

- Wechsler H, Austin B, DeJong W (1996) Secondary Effects of Binge Drinking on College Campuses. Newton, MA, Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention Education Development Center, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Barnett NP, Clark M (2010) Attendance at alcohol-free and alcohol-service parties and alcohol consumption among college students. Addict Behav 35:572–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A, Castle I-JP, Chen CM, Shirley M, Roach D, Hingson R (2015) Converging patterns of alcohol use and related outcomes among females and males in the United States, 2002 to 2012. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39:1712–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A, Hingson R (2013) The burden of alcohol use: Excessive alcohol consumption and related consequences among college students. Alcohol Res Curr Rev 35:201–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J (2001) Negative consequences of alcohol use among college students: Victims or victimizers? J Drug Educ 31:271–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]