Abstract

Animal models reveal that deafferenting forelimb injuries precipitate reorganization in both contralateral and ipsilateral somatosensory cortices. The functional significance and duration of these effects are unknown, and it is unclear whether they also occur in injured humans. We delivered cutaneous stimulation during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to map the sensory cortical representation of the intact hand and lower face in a group of chronic, unilateral, upper extremity amputees (N = 19) and healthy matched controls (N = 29). Amputees exhibited greater activity than controls within the deafferented former sensory hand territory (S1f) during stimulation of the intact hand, but not of the lower face. Despite this cortical reorganization, amputees did not differ from controls in tactile acuity on their intact hands. S1f responses during hand stimulation were unrelated to tactile acuity, pain, prosthesis usage, or time since amputation. These effects appeared specific to the deafferented somatosensory modality, as fMRI visual mapping paradigm failed to detect any differences between groups. We conclude that S1f becomes responsive to cutaneous stimulation of the intact hand of amputees, and that this modality-specific reorganizational change persists for many years, if not indefinitely. The functional relevance of these changes, if any, remains unknown.

INTRODUCTION

Neurons sharing similar response properties are grouped together within the primary sensory cortex (S1) of each cerebral hemisphere to form a detailed somatotopic map of the contralateral body surface (Penfield, 1937). Evidence indicates that this organization is maintained through competitive, largely inhibitory interactions between cortical areas (Kaas, 1991; Jones, 2000). Peripheral injuries that selectively eliminate afferent stimulation to a portion of this map disrupt this balance, inducing an expansion of neighboring representations into the deafferented zone (Kaas et al., 1983; Merzenich et al., 1983; Calford and Tweedale, 1988; Pons et al., 1991). Following hand amputation in non-human primates, for instance, contralateral S1 neurons previously devoted to the hand become responsive to cutaneous stimulation of adjacently represented areas of the hemi-face, and/or residual forelimb (Florence and Kaas, 1995; Florence et al., 1998).

Deafferenting forelimb injuries also induce changes in the S1 representation of the homotopic limb in the hemisphere ipsilateral to the injury. After amputating the distalmost portion of a digit, receptive fields within the deafferented, contralateral zone expand, becoming responsive to stimulation of the remaining phalanges, and these changes are reflected almost immediately in the S1 representation of the homotopic uninjured digit located in the opposite hemisphere (Calford and Tweedale, 1990).

Soon after complete deafferentation of a rodent forepaw, stimulation of the unaffected paw increases activity within both its normal contralateral S1 territory, and in the ipsilateral deafferented zone (Pelled et al., 2007; Pelled et al., 2009; Pawela et al., 2010). These ipsilateral S1 responses to intact forepaw stimulation appear within 60mins post-injury (Pawela et al., 2010) and are associated with increased inhibitory interneuron activity within layer V of the deafferented cortex—a layer that supports dense, reciprocal transcallosal connections (Pelled et al., 2009; Han et al., 2013). Ablation of the healthy forepaw’s S1 representation eliminates these ipsilateral S1 effects, indicating that they depend on interhemispheric transmission from the contralateral side (Pelled et al., 2007). While it has been suggested that this aberrant ipsilateral S1 activity limits recovery from nerve injury (Pelled et al., 2007), empirical support for this hypothesis is missing. Indeed, the functional significance of these changes, if any, has yet to be established.

Whether cutaneous stimulation of the intact hand of traumatic amputees leads to similar increases in activity in the former sensory hand territory (S1f) is unclear. Conversely, several fMRI studies have shown that amputees activate ipsilateral primary motor and sensory cortices when moving their intact hand (Kew et al., 1994; Hamzei et al., 2003; Bogdanov et al., 2012; Makin et al., 2013; Philip and Frey, 2014). In dominant-hand amputees, these ipsilateral response-changes are associated with improved performance on a drawing task with the intact hand, suggesting that they may be functionally adaptive (Philip and Frey, 2014; see also, Makin et al., 2013). In healthy adults, transient unilateral hand deafferentation increases excitability of the ipsilateral hemisphere (Werhahn et al., 2002a), and acutely improves tactile acuity of the opposite hand (Björkman et al., 2004). Whether chronic unilateral amputees exhibit improved tactile acuity with their unaffected hand is unknown.

Here we used fMRI to estimate cortical organization in chronic, unilateral, upper-extremity amputees while delivering precise cutaneous stimulation. Based on the work introduced above, we predicted that amputees would exhibit greater activity than controls in S1f during stimulation of the contralateral face and the intact (ipsilateral) hand. To the extent that these effects are functionally relevant, we expected fMRI responses within S1f to be associated with behavioral differences between amputees and controls in tactile acuity of the hand. One possibility is that amputees would exhibit improved tactile acuity as a result of increased cortical resources dedicated to coding input from the hand. Alternatively, atypical ipsilateral responses in S1f could, at least in principle, increase noise in the representation of the stimulus and thereby impair performance. Finally, we also mapped fMRI responses to visual stimulation. If amputation-driven reorganization is specific to the deafferented somatosensory modality, we expected no differences between amputees and controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

All participants gave informed consent in accordance with the University of Missouri IRB, and the experiment was approved by the local institutional review board in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Nineteen unilateral upper limb traumatic amputees participated: 7 females; 10 below-elbow; 15 right-hand; mean age 45 ± 14 years (range 20 – 67); mean time since amputation 15 ± 13 years (range 2 – 45 years); see Table 1 for full demographics. Twenty-nine healthy adult controls participated: 11 females; mean age 44 ± 14 years (range 26 – 70). One amputee lost all of their right fingers but not the palm. All amputees were right-handed based on self-report of past experiences before amputation (Edinburgh score > 40). All controls were likewise right-hand dominant (Edinburgh score > 33) (Oldfield, 1971).

Table 1.

Amputee participant characteristics and behavior.

| Demographics | Pain | Tactile Acuity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | AH | Level | Age | YSA | AAA | Pros | PLP current | PLP avg | RLP avg | GOT |

| M | R | AE | 42 | 21 | 21 | 0 | 49 | 58 | 0 | 1.81 |

| M | R | AE | 62 | 36 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 2.38 |

| F | R | BE | 46 | 3 | 43 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 22 | – |

| M | R | BE | 32 | 14 | 18 | 77 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.31 |

| F | R | AE | 67 | 2 | 65 | 32.5 | 2 | 12 | 12 | 3.58 |

| F | R | AE | 31 | 7 | 24 | 63 | 11 | 23 | – | – |

| M | R | BE | 50 | 19 | 31 | 0 | 9 | 24 | 40 | – |

| F | R | AE | 43 | 6 | 37 | 0 | 58 | 40 | 0 | – |

| M | R | AE | 56 | 3 | 53 | 31.5 | 11 | 24 | 0 | 2.29 |

| M | L | BE | 52 | 11 | 41 | 98 | 7 | 17 | 0 | 2.42 |

| F | R | AE | 64 | 13 | 51 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| M | L | BE | 20 | 6 | 14 | 4 | 4 | 16 | 0 | 2.46 |

| F | L | BE* | 38 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38 | – |

| M | R | BE | 29 | 7 | 22 | 77 | 24 | 22 | 0 | – |

| M | R | BE | 65 | 45 | 20 | 105 | 9 | 14 | – | 2.5 |

| M | R | AE | 44 | 5 | 39 | 91 | 40 | 53 | 54 | 2.46 |

| M | L | BE | 42 | 20 | 22 | 67 | 42 | 51 | 0 | 2.59 |

| F | R | AE | 22 | 2 | 20 | 1 | 0 | 22 | 26 | – |

| M | R | BE | 40 | 20 | 20 | 112 | 9 | 19 | 24 | – |

AH = affected hand. Level = amputation level (BE = below elbow, AE = above elbow, * = fingers only). YSA = years since amputation. AAA = age at amputation. Pros = prosthesis usage (hours/week over last 6 months). PLP = phantom limb pain. RLP = residual limb pain. GOT = grating orientation threshold (in mm). All pain surveys scaled to 0–100.

Volunteers with significant psychiatric or neurological illness, or with factors incompatible for MRI (e.g., implanted medical devices) were excluded, as were controls who were currently experiencing pain, or had a significant history of chronic pain.

Behavioral measurements

Pain and referred sensation

For amputee participants, a clinician administered the Neuropathic Pain Scale (Galer and Jensen, 1997) to measure average phantom limb pain (PLP) and average residual limb pain (RLP), as well as the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (Melzack, 1987) to measure current PLP (Table 1). Both types of pain were evaluated by asking the patient to focus their attention on each type, respectively. No patient reported difficulty differentiating between phantom and residual limb pain. Referred sensation testing was also performed by a clinician, by dragging a 4.93 Semmes-Weinstein filament for 5 cm along the bilateral upper arms, lower arms, and face. During testing, participants closed their eyes and verbally reported the location where they felt the sensation. Similar methods have been used previously to identify the presence or absence of referred sensations (Ramachandran et al., 1995; Hunter et al., 2003).

Tactile acuity

Twenty-four (of 29) controls and ten (of 19) amputees participated in the grating orientation task (GOT). The GOT tests cutaneous spatial resolution with a two forced-choice paradigm (Van Boven and Johnson, 1994), and is considered ideal for evaluating tactile acuity thresholds, as the magnitude of the stimulus is held constant while its spatial structure is selectively manipulated (Johnson and Phillips, 1981; Gibson and Craig, 2002).

Gratings were applied via ten hemispherical plastic domes with gratings cut into their surfaces, i.e. parallel ridges and grooves of equal widths for each dome (Tactile Acuity Gratings, MedCore, www.med-core.com). The domes had ridges and grooves of the following widths: 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.2, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, and 3.5 mm.

Participants were comfortably seated with their eyes closed. Their hand rested on the table palm upward, in a custom-made splint that stabilized their hand and exposed the palmar surface of the index finger. A trial involved pressing a dome against the palmar surface of the fingertip for approximately 1.5 seconds, with approximately 2 mm skin displacement. The participant reported their experience of the orientation of the dome’s grating: straight (parallel to the finger) or crossed (perpendicular to the finger).

The GOT was presented in blocks of 30 trials, with feedback provided only in the form of average performance at the end of the block. At the start of each block, the participant was shown the dome for visual inspection, and received 5 familiarization trials with immediate feedback. If the participant achieved 50% or greater accuracy on a block, the experiment continued with another block of the next smaller grating. Following Ragert et al. (2008), the participant’s GOT threshold was determined with the following formula:

Where G75 reflects the GOT threshold, defined as the groove width at which the participant achieves 75% accuracy. G = grating spacing, and P = proportion of correct trials. “Below” = the grating spacing or proportion of correct responses on the highest grating spacing for which the participant responded correctly less than 75% of the time; “above” = grating spacing or the proportion of correct responses on the lowest grating spacing for which the participant responded correctly more than 75% of the time.

For tactile acuity and all other sensory measures, performance of healthy control participants is reported for the left hand.

MRI

Somatosensory mapping

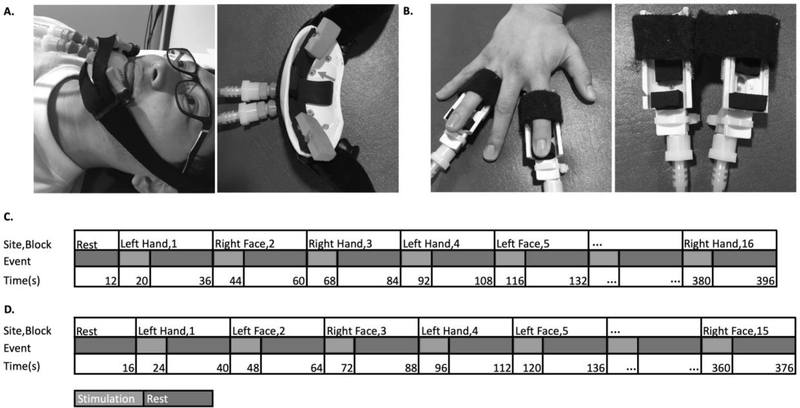

Cutaneous sensory stimulation was delivered during fMRI scanning using a custom-designed, 16-channel, computer-controlled, pneumatic apparatus (Smith, 2009). Four sites (three in amputees, due to absence of one hand) received puffs of compressed air: 1) Left Hand (LH) index and ring fingertips, 2) Right Hand index and ring fingertips (RH), 3) lower Left Face (LF), and 4) lower Right Face (RF). Each site received pneumatic stimulation from two nozzles (i.e. one on each of two fingers, or two on the same side of the lower face) (Figure 1). Index and ring fingers were selected to provide stimulation to median, ulnar and radial nerve distributions.

Figure 1. Apparatus and design.

Cutaneous stimulation was applied to the left or right lower face (A) or tips of the second and fourth digits of the left or right hand (B). These digits were selected to include median, radial and ulnar nerve distributions. Sample timeline of events from a single run for controls (C) and amputees (D).

Stimulation was delivered in a block design. Each block comprised 8 seconds of stimulation (3 Hz, 20% duty cycle, 30 liter/min flow rate), followed by 16 seconds of rest. Each run comprised 15 blocks for amputees (5 blocks for each of 3 sites: L- and R- lower face, and the intact hand), or 16 blocks for controls (4 blocks for each of 4 sites). Each run began with 12 seconds (controls) or 16 seconds (amputees) of rest. Participants completed 4 functional runs.

Throughout the experiment, participants were instructed to lay still, keep their eyes on a fixation cross, and pay attention to the air puffs. Participant’s wakefulness was monitored with an eye-tracker camera, (Eye-Trac 6000, Applied Science Laboratories, Bedford MA), and participant self-report after each run. Self-report refers to how wakeful the participant felt, addressed verbally between runs. If the participant fell asleep, the run was repeated.

Visual mapping

To test for between-groups differences beyond the sensorimotor system, most participants (26 controls, 10 amputees) performed a visual mapping task in the fMRI scanner.

The visual mapping task comprised 1 run of 12 cycles (402 sec total) of alternating 16 second-duration fixation and visual stimulation blocks. Participants were instructed to maintain fixation on a central cross, which was present in both conditions. Visual stimulation involved viewing a high-contrast flashing checkerboard (4 Hz, 50% duty cycle) stimulus presented in a ring (diameter) surrounding the fixation cross. An 18-second fixation period was included after the last cycle. Fixation was monitored by an eye-tracking camera, as described above.

MRI parameters

Scans were performed on a Siemens (Erlangen, Germany) 3T Trio using a standard birdcage radio-frequency coil. The session started with T1- and T2- weighted structural scans. High-resolution T1-weighted structural images were acquired using 3D MP-RAGE pulse sequence with the following parameters: TR = 2500 ms, TE = 4.38 ms, T1 = 1100 ms, flip angle = 8.0°, 256 by 176 voxel matrix, FoV = 256 mm, 176 contiguous axial slices, thickness = 1.0 mm, and in-plane resolution at 1.0 by 1.0 mm. The total durations of the T1- and T2-weighted structural scans were 8 minutes and 13 seconds, and 6 minutes, respectively.

Functional MRI scans were performed via T2*-weighted functional runs with echo planar imaging sensitive to the blood oxygen-level dependent contrast (BOLD-EPI) with the following parameters: TR = 3000 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 84°, 64 by 64 voxel matrix, FoV = 200 mm, 48 contiguous axial slices (no gap) with interleaved order, thickness = 3.0 mm, in-plane resolution at 4.0 × 4.0 mm, bandwidth = 2004 Hz/pixel. Each BOLD scan comprised 132 volumes (396 sec) for Controls, and fewer for Amputees: 125 volumes (375 sec) for most participants, but due to a technical issue three amputee participants received 121-volume (363 sec) runs. The first two volumes in each scan were discarded to allow steady-state magnetization to be approached. The fMRI session concluded with a double gradient echo sequence to acquire a field map used to correct for EPI distortions.

Functional scan parameters for the visual mapping task differed as follows: TE = 4.38 ms, flip angle = 8.0°, FoV = 256 mm, and in-plane resolution at 3.125 by 3.125 mm. All other parameters were the same as those used for the somatosensory mapping task.

fMRI Preprocessing

DICOM image files were converted to NIFTI format using MRIConvert software (http://lcni.uoregon.edu/~jolinda/MRIConvert/). Structural and functional fMRI data were preprocessed and analyzed using fMRIB’s Software Library (FSL v5.0, http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/) (Smith et al., 2004). Non-brain structures were removed using BET. Head movement was reduced using MCFLIRT motion correction. EPI unwarping was performed to correct for distortions due to magnetic field in-homogeneities using FSL PRELUDE and FUGUE, using a separate field-map collected following the functional runs.

Functional data were spatially smoothed using a Gaussian kernel of 6 mm FWHM. Slice-time correction was applied. Intensity normalization was applied using “grand mean scaling”, wherein each volume in the dataset was scaled by the same factor to allow for valid cross-session and cross-subject statistics. High-pass temporal filtering (100-second cut-off) was applied to remove low frequency artifacts.

Functional data were registered with the high-resolution structural image using boundary-based registration (Greve and Fischl, 2009), and resampled to 1 × 1 × 1 mm resolution using FLIRT; these images were then registered to standard images (Montreal Neurological Institute MNI-152) using FNIRT nonlinear registration at 12 degrees of freedom with warp resolution at 10 mm. Time series statistical analysis was carried out in FEAT v.6.00 using FILM with local autocorrelation correction (Woolrich et al., 2001).

fMRI Data Analysis

The hemodynamic response function was modeled by explanatory (predictor) variables (EVs) locked to the time course of puffer stimulation at each site: LH, RH, LF, and RF. For amputees, the absent hand was included in the model as an empty EV. Additional covariates of no interest were included based on the mean time series of the whole-brain, and single-point predictors for each time point of high-motion outliers. Outliers were identified within each run as time points with framewise displacement exceeding 1.5*interquartile range above the third quartile.

Using these EVs, first-level contrasts of parameter estimates (COPEs) were calculated for each of the following contrasts: LH > Rest, RH > Rest, LF > Rest, and RF > Rest.

Second-level analyses were performed for each participant by combining first-level analyses (i.e. four runs) using a fixed-effects model. Z-statistic (Gaussianized T) images were thresholded at z > 3.1, corrected for multiple comparisons using a cluster-size significance threshold of p < 0.05.

The top-level analysis used the second-level (subject) analyses as inputs for between-group contrasts using a mixed-effects model via FSL FLAME 1. Data from left-hand amputees were left-right flipped to enable combining with right-hand amputees. Three independent third-level analyses were performed: (1) average of amputee participants; (2) average of control participants; (3) group-difference between amputees and controls. An inclusive mask was applied to these data. The mask was defined using an “OR” function to combine resultant maps specified in either group, separately, by the contrasts: LH > Rest; RH > Rest (valid only for controls); LF > Rest; RF > Rest. This method selects voxels showing significant task-related activity in response to any stimulation condition (versus rest), in either group. This makes subsequent tests more sensitive (in this case, specifically the contrasts between groups) by reducing the number of voxels considered for correction for multiple comparisons.

Data from the visual mapping task were analyzed similarly. EVs were locked to the time course of visual stimulation (checkerboard onset and offset), and motion outliers were included as covariates of no interest. A single COPE was calculated for Visual Stimulation > Fixation. Top-level analyses were performed using the first-level analyses as inputs for between-group contrasts using a mixed-effects model via FSL FLAME 1 to identify between-group contrasts (amputees vs. controls). Again, data from left-hand amputees were left-right flipped.

ROI analysis

Left and right hemisphere S1 hand ROIs were functionally defined on the basis of Controls’ (group) data, hereafter referred to as the estimated former (S1f) and intact (S1i) sensory hand ROIs of amputees, respectively. For each ROI, the defining contrast was the contralateral hand > rest. The voxel with the highest Z-value was identified (S1f: MNI coordinates X = 66, Y = 48, Z = 57; S1i X= 21, Y = 52, Z = 29), a 5 mm-diameter-sphere was centered on this coordinate, and significantly active voxels (thresholded at z > 3.1) within the sphere were included if they had a ≥ 25% chance of being in the S1 complex (Broadmann’s area 1, 2, or 3) according to the Juelich Histological Atlas (Geyer et al. 2000). Each group-defined ROI was inverse-registered with FLIRT to individual participant space, producing participant-specific ROIs. Left-hand amputees were retained in the ROI analysis, with their data left-right flipped, as described above.

The time course of changes in image intensity across all voxels of each S1 hand ROI were extracted through FSL’s Featquery, and the percent BOLD signal change (%-BSC) values were calculated for each condition (i.e. COPE) for each participant. To compare responses between groups, these data were entered into a Condition (three levels: LH, LF, RF) by Group (Amputees, Controls) mixed ANOVA. COPEs involving the RH were omitted because they lacked amputee data. Where significant main and interaction effects were identified, and significant differences in covariance matrices between groups were also identified, Welch’s unequal variances t-tests were used to evaluate between-group post-hoc comparisons.

ROI analysis was similar for the visual mapping data, the purpose of which was to quantify visual activation between groups. Visual ROIs were anatomically defined as all areas with ≥ 50% chance of being within any of the areas V1-V5, according to the Juelich Histological Atlas (Geyer et al., 2000) in FSL; separately for left and right hemisphere. Each group-defined ROI was inverse-registered with FLIRT to individual participant space, producing participant-specific ROIs. Visual ROIs were analyzed via a 2 (Group: Amputees, Controls) * 2 (Hemisphere: Contralateral to amputation, Ipsilateral to amputation) ANOVA.

Correlational analysis between behavioral/demographics and ROI %-BSC values

A total of six behavioral/demographic factors were tested for correlations with %-BSC in S1f and S1i ROIs during intact hand stimulation: one sensory measure (GOT threshold on the intact hand), three pain measures (average PLP; current PLP; average RLP), and two demographic values (years since amputation; prosthesis use, measured in hours/week over the last six months). Age at amputation and age at test were not included since these factors were fully colinear with years since amputation (r = 1.00).

Spearman’s r was used, supplemented by nonparametric Kendall’s τ for data with small sample sizes or overt outliers. Conclusions did not differ between these methods. For brevity, only τ is shown. Statistical significance was defined at α = 0.0083 (0.05 / 6 factors).

For behavioral factors present in both amputees and controls, analyses of covariance (ANOCOVA) were used to test for reliable between-group differences in the relationships (i.e. slope) between factor and outcome (ROI %-BSC) measures.

RESULTS

Whole-brain fMRI results

Amputees show atypical increased ipsilateral activity during intact hand stimulation

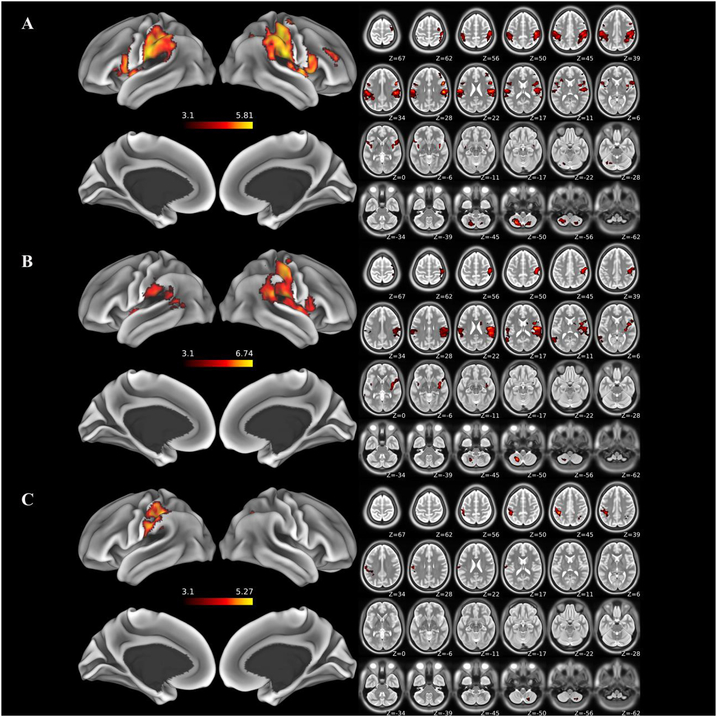

Brain areas showing significant positive fMRI responses during stimulation of the intact hand vs. rest are identified in Amputees (Figure 2A), and, for comparison, during stimulation of the left hand vs. rest in Controls (Figure 2B). A direct test for differences in fMRI responses to hand stimulation between groups reveals significantly greater activity in the postcentral gyrus (putative S1-complex) ipsilateral to hand stimulation in Amputees relative to Controls (Figure 2C). These results demonstrate that cutaneous stimulation of the hand uniquely activates the ipsilateral S1-complex in Amputees relative to Controls. Increased activity in Amputees relative to Controls extends from the left central sulcus medially, along the convexity of the postcentral gyrus to the SPL and intraparietal sulcus. Amputees also show uniquely greater responses in the right cerebellar lobule VIIIa, and the right posterior intraparietal sulcus (visible in slices Z = 45 and 39, Figure 2C). Otherwise, both groups exhibit similar, widespread increases in fMRI responses throughout the extended sensory network, including contralateral S1, bilateral parietal operculum (putative S2), insular cortex, inferior parietal lobule, right inferior frontal gyrus, and left cerebellar lobule VIIIa. No areas are significantly more active in Controls vs. Amputees. All significantly active clusters are reported in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 2. Results of whole-brain fMRI analyses.

Areas exhibiting statistically significant effects are displayed on semi-inflated surface rendering (left) and accompanying axial slices (right): (A) Areas exhibiting significant increases for stimulation of the intact “left” hand in amputees relative to baseline. (B) Areas exhibiting significant increases for stimulation of the “left” hand in controls relative to baseline. (C) Areas exhibiting significantly greater activity during stimulation of the intact “left” hand in amputees compared to the comparable hand in controls. This difference includes S1f and extends caudally across the lateral convexity of the postcentral sulcus, and into the supramarginal gyrus. See text for details.

No evidence for increased responsivity to face stimulation in amputees

Contrary to expectations based on earlier unit-recording studies in animals, we failed to detect differences between Amputees and Controls in response to lower Right Face stimulation, located ipsilateral to the amputation. Left and Right Face stimulation significantly activates sensory areas in both Amputees and Controls, including the lateral and ventral aspects of the postcentral gyrus, bilateral parietal operculum and insular cortex (Supplementary Table 1). No areas were differentially activated between Amputees and Controls.

No differences in visual cortex activation between amputees and controls

To test for possible changes in brain activity patterns to non-tactile stimulation in non-sensorimotor areas following amputation, we used a visual mapping task to identify brain areas responsive to viewing a flashing checkerboard stimulus. Whole-brain analysis reveals no areas showing significant differences between Amputees and Controls.

Similarly, mixed ANOVA results on the basis of visual ROI data (see Methods) reveal no significant main effects of Group or Hemisphere, nor an interaction effect (F(1,86) < 0.7, p > 0.4). Therefore, we find no evidence of task-nonspecific differences in brain activity between Amputees and Controls based on our independent assessment of responses to visual stimuli in visual cortices.

Somatosensory region of interest (ROI) fMRI results

Left and right hemisphere S1 hand ROIs are functionally defined on the basis of the Controls’ data, using the contrasts: contralateral hand > rest, respectively. The left hemisphere S1 ROI represents the estimated S1f of Amputees, while the right S1 ROI represents S1i.

Former sensory hand area (S1f): Contralateral to amputation

A mixed ANOVA reveals significant main effects of Condition (F(1.6, 72.4) = 46.9, p < 0.001) and Group (F(1, 46) = 12.6, p < 0.005), and critically, a significant interaction (F(1.6, 72.4) = 9.0, p < 0.005).

The significant interaction reflects reliably greater activity in Amputees relative to Controls that is specific to stimulation of the ipsilateral hand (t(27) = 4.1, p < 0.001) and not face stimulation (ipsilateral: t(31) = 0.30, p = 0.77; contralateral: t(46) = 1.03, p = 0.31) (Figure 3A). These data provide evidence for amputation-related interhemispheric functional reorganization within S1f that is specific to cutaneous stimulation of the intact hand, consistent with the findings revealed via our whole-brain analyses.

Figure 3. ROI results.

L-S1 (A) and R-S1 (B) hand ROIs are functionally defined by data from controls. Slices show ROI locations and MNI coordinates. L-S1 is the estimated former sensory hand area of amputees (S1f). Boxplots show percent BOLD signal change (%-BSC) values per condition per ROI for amputees and controls, with individual-level data as open circles. Filled circles indicate left-hand amputees (after these data are left-right flipped). The line within boxplots indicates the median, the upper and lower edges indicate the third and first quartiles, respectively, and the error bars indicate the maximum and minimum data points. Grey shading indicates the 95% confidence intervals of the group mean. The * indicates a statistically significant group difference, p < 0.001.

Intact hand area (S1i): Ipsilateral to amputation

A mixed ANOVA reveals a significant main effect of Condition (F(1.4, 63.4) = 134.5, p < 0.001), no main effect of Group (F(1, 46) = 0.16, p = 0.69), and no significant interaction (F(1.4, 63.4) = 3.0, p = 0.08).

The significant main effect of Condition reflects higher activity during cutaneous stimulation of the contralateral hand for both Amputees and Controls (Figure 3B). Contralateral hand stimulation results in higher response-levels compared with both contra- and ipsilateral face stimulation (p < 0.001), which do not differ (p = 0.27).

The ROI is defined by stimulation of the contralateral hand > rest based on Controls data, so these results, at least for the Controls data, are not surprising – ‘prespecified’ by the ROI-defining contrast. This contrast also biases these results in favor of Controls > Amputees; the signal amplitude measures for the contralateral hand for Controls are biased to be high (Kriegeskorte et al., 2009). Despite this, Amputees and Controls show comparable levels of activity in the contralateral S1 hand area during stimulation of the hand (t(1, 35.7) = 1.05, p = 0.31). In other words, we find no evidence for amputation-related functional changes in the intact S1 hand area in response to hand stimulation.

The Condition by Group interaction term that approaches statistical significance (p = 0.08) in the mixed ANOVA reflects a tendency for Controls to show greater response-levels than Amputees during stimulation of the contralateral (left) face. Responses to ipsilateral (right) face stimulation are similar for both groups.

Behavioral results

Pain and referred sensation

Measures of average phantom limb pain (PLP), average residual limb pain (RLP), and current PLP are provided in Table 1. 68% of patients suffered from PLP, 42% RLP, and 26% experienced both types of pain. No participants reported difficulty differentiating between pain types.

No participants reported referred sensations. We found no evidence for mislocalization of stimuli during referred sensation testing (see Methods for details).

Tactile acuity

We found no differences between Amputees and Controls in measures of tactile acuity. GOT thresholds measured on the intact hand of Amputees (mean = 2.48) are statistically comparable to the GOT thresholds measured on the left hand of Controls (mean = 2.20) (t(25.7) = 1.43, p = 0.165). Given the current effect size, power analysis suggests that a minimum sample size of 78 participants per group would be required to identify statistical significance with 80% power.

Somatosensory ROI activation shows no relationship with pain, tactile acuity, or demographics

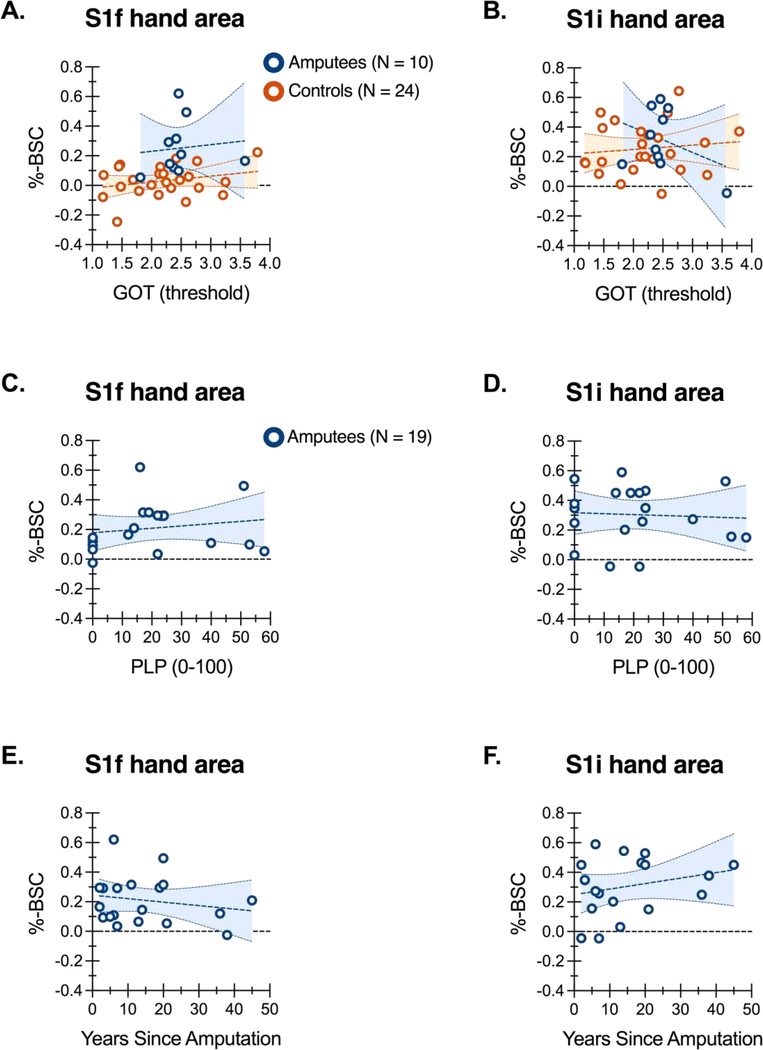

In an attempt to identify the functional significance of aberrant ipsilateral S1f responses to hand stimulation in our amputees, we performed single-factor correlations to test for possible relationships between our six behavioral/demographic factors and fMRI %-BSC values from both S1f and S1i ROIs.

We found no evidence for reliable relationships between any of our behavioral or demographic factors and fMRI activity during intact hand stimulation in either S1f or S1i ROIs (Table 2). To illustrate this, Figure 4 shows data of three sample factors as a function of ROI %-BSC values. GOT thresholds on the intact hand are uncorrelated with fMRI response levels in S1f or S1i (Figure 4A and B, respectively). Data from Controls are shown for comparison (i.e. left-hand GOT thresholds by LH > rest %-BSC values per ROI). Notably, the slopes of the regression lines do not differ between Amputees and Controls, as qualified by a non-significant ANCOVA interaction term found for both ROIs, respectively (S1f: F(1,30) = 0.002, p = 0.97; S1i, F(1,30) = 1.77, p = 0.19). Of additional interest, separate analysis of Controls data indicates that a significant extent of variation in GOT thresholds is attributable to age (r = 0.5829, 95% confidence intervals: 0.2347 to 0.7986, p < 0.005, r2 = 0.3398). Tactile acuity decreases with age, consistent with previous data (Tremblay et al., 2003).

Table 2.

No behavioral/demographic factors predict ROI %-BSC activity during cutaneous stimulation of the fingers (intact hand > rest).

| ROI: S1f | ROI: S1i | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | τ | p | τ | p | |

| Sensation | GOT threshold | −0.082 | 0.649 | 0.047 | 0.806 |

| Pain | Average PLP | 0.139 | 0.436 | −0.042 | 0.832 |

| Current PLP | 0.062 | 0.748 | −0.112 | 0.544 | |

| Average RLP | −0.086 | 0.676 | 0.055 | 0.802 | |

| Demg. | YSA | −0.059 | 0.752 | 0.095 | 0.599 |

| Pros | 0.218 | 0.216 | 0.012 | 0.972 | |

Demg. = demographic factors. For abbreviations, see Table 1.

Figure 4. ROI activity and tactile acuity, phantom limb pain, and years since amputation.

GOT thresholds (A/B), average phantom limb pain (C/D), and years since amputation (E/F) are shown as a function of percent BOLD signal change (%-BSC) per S1f and S1i ROIs during stimulation of the intact hand of amputees, and for comparison, the left hand of controls (A/B only). Regression lines are shown with 95% confidence intervals.

The absence of any significant correlations between ROI activity levels and average phantom limb pain (Figure 4C–D) and years since amputation (Figure 4E–F) is also shown. Additional tests of pain measures omitting patients who report zero pain (N = 5 for current PLP; N = 6 for average PLP; N = 11 for average RLP), also reveal no significant correlations (all p values > 0.12), even without correcting for multiple comparisons.

We also find no evidence for an association between amputation level and fMRI responses to hand stimulation in S1f (t(13.5) = 1.16, p = 0.27). Conversely, however, amputation level does appear to relate to the magnitude of fMRI responses in S1i (Figure 5). Our subgroup of below-elbow amputees (BE; N = 10) show greater responses to cutaneous hand stimulation in S1i relative to our subgroup of above-elbow amputees (AE; N = 9) (t(16.8) = 2.33, p < 0.05).

Figure 5. ROI results by amputation level.

Boxplots show percent BOLD signal change (%-BSC) values corresponding to stimulation of the intact hand per ROI (A/B) for above and below elbow amputees, respectively, with individual-level data as open circles. The line within boxplots indicates the median, the upper and lower edges indicate the third and first quartiles, respectively, and the error bars indicate the maximum and minimum data points. The * indicates a statistically significant group difference, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Our investigation of post-amputation cortical organization in the human somatosensory system using cutaneous stimulation and fMRI yields several primary results. As predicted on the basis of earlier work in animal models, chronic amputees exhibit significantly greater activity than controls within S1f in response to cutaneous stimulation of the intact hand. Nevertheless, the functional relevance of these reorganizational changes remains unclear. Tactile acuity on the hand is no different between amputees and controls. Likewise, we find no relationship between the magnitude of fMRI responses to hand stimulation within S1f and tactile acuity, or pain. Contrary to expectations, amputees show no evidence for expansion of the somatotopically adjacent face representation into the deafferented S1f. Finally, consistent with the view that the effects of deafferenting injuries are specific to brain areas representing the impacted modality, we fail to detect any evidence that amputation alters the functional organization of the visual cortex. Our main findings and their implications are discussed in detail below.

Stimulation of the intact hand increases responses within the deafferented S1f

Amputees exhibit increased ipsilateral parietal activity in response to cutaneous stimulation of the intact hand. These effects extend along the post-central gyrus—from the caudal bank of the central sulcus through the postcentral sulcus—onto the lateral convexity of the SMG, and into the IPS. Critically, this includes S1f as defined probabilistically based on data from our control group. This finding provides a heretofore missing link with recent demonstrations of responses to stimulation of the intact rat forepaw within the deafferented rodent S1 forepaw region (Pelled et al., 2007; Pelled et al., 2009; Pawela et al., 2010). In rats, these ipsilateral responses appear within 60mins after unilateral transection of forepaw nerves (Pawela et al., 2010), and persist for at least several weeks (Pelled et al., 2007). That we detect apparently similar responses in chronic human amputees suggests that these effects of deafferentation on functional cortical organization are highly persistent, if not permanent. How soon they emerge after amputation remains unknown; although, we find no relationship between the magnitude of responses to hand stimulation within S1f and time since amputation.

The parallel between our findings and the studies in animal models motivates specific hypotheses concerning underlying mechanisms. In rodents, responses within S1f to stimulation of the intact paw depend on interhemispheric transmission from the contralateral side (Pelled et al., 2007; Li et al., 2011). If interhemispheric transmission underlies the S1f responses that we observe during hand stimulation in human amputees, then suppression of the cortical representation of the intact hand (e.g., with non-invasive brain stimulation) might reduce these effects.

Following partial digit amputation in flying foxes and monkeys, Calford and Tweedle (1988, 1990) describe an expansion of the receptive fields of S1 neurons located in the deafferented cortical zone (contralateral to the injury) that is immediately reflected in the homotopic region of the opposite hemisphere (ipsilateral to the injury). They refer to these changes as interhemispheric transfer of cortical plasticity, and attribute the mechanisms to transcallosal signaling involved in maintaining the excitatory-inhibitory balance between homotopic regions of sensory cortices. Since the receptive fields expand when ipsilateral input is removed, the normal function of these signaling pathways is presumed inhibitory.

The current findings differ from these initial reports of bilateral effects of unilateral deafferentation. First, we detect atypical responses within the S1f of chronic unilateral amputees during stimulation of the intact hand, while Calford and Tweedle report no indication that stimulation of the intact digits evokes responses within deafferented cortex. Second, while our data reveal changes that persist chronically, the receptive field changes discovered by Calford and Tweedle were seen to resolve over tens of minutes, at least in the majority of animals (in some individuals, these changes were maintained for the entire 3-hour recording period (Calford and Tweedale, 1988).

Taken together, one possibility is that the extent of deafferentation determines the presence and persistence of aberrant ipsilateral responses in S1f. This would explain why our results better align with those from rodent models involving complete forepaw deafferentation (Pelled et al., 2007; Pelled et al., 2009; Pawela et al., 2010). Accordingly, shortly after partial digit amputation, stimulation of the homotopic intact digit should result in atypical ipsilateral responses in S1 that dissipate with time.

Our data differ significantly from other recent fMRI results revealing stable digit-specific representations in S1 following hand amputation. Using representational similarity analyses, the organizational structure of digit-specific representations in the deafferented sensorimotor areas of chronic upper-limb amputees, including S1, defined by movements of either the intact or phantom digits is no different than the digit-specific organization defined in healthy controls (Wesselink et al., 2019). Conversely, our findings reveal reorganization of S1f defined by increased fMRI responses to passive cutaneous stimulation of the intact hand.

Different underpinning mechanisms related to active movements versus passive stimulation are likely at play. Indeed, while the fMRI representational content of ipsilateral S1 responses to active digit movements yields digit-specific information in healthy controls, no such information is evident for passive cutaneous digit stimulation (Berlot et al., 2019). Together, this underscores the importance of the advancements made here. For the first time, we measure cortical responses to passive cutaneous stimulation of the intact digits of chronic traumatic upper-limb amputees and discover robust atypical (ipsilateral) responses in S1f.

No evidence for changes in sensation of amputees’ intact hands

By demonstrating evidence of both cortical reorganization and the absence of sensory changes within the very same individuals, our study extends earlier psychophysical investigations that fail to detect changes in sensory functions involving regions of the body presumed to have expanded cortical representations following deafferenting injuries (Braune and Schady, 1993; Schady et al., 1994; Moore and Schady, 2000; Vega-Bermudez and Johnson, 2002). Together this work raises the possibility that cortical reorganization following reductions in afferent activity may have minimal impact on function. If this proves true, then efforts to develop therapeutic interventions by reversing such changes may be misguided (MacIver et al., 2008). Given both the theoretical and clinical significance of this issue, more attention is needed.

By altering the interhemispheric balance of cortical excitability (Werhahn et al., 2002c), transient unilateral deafferentation by ischemic nerve block induces temporary improvements in tactile discrimination of the opposite hand on the GOT (Werhahn et al., 2002b; Björkman et al., 2004). Despite the evidence we provide for pronounced changes in cortical excitability, we fail to detect differences between amputees and controls on GOT performance. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that transient versus chronic deafferentation induces interhemispheric imbalances in cortical excitability through distinct mechanisms. While transient deafferentation induces reorganization by unmasking latent synapses (Werhahn et al., 2002c), chronic deafferentation also involves structural changes in the form of intracortical axonal sprouting (Florence et al., 1998). A similar null result has been reported for tactile acuity on digits with presumably expanded representations following amputation of a neighboring finger (Vega-Bermudez and Johnson, 2002). Likewise, we detect no reliable relationship between responses in S1f to stimulation of the intact hand and pain.

No evidence for expansion of the face representation into the former hand territory

Neither whole-brain nor ROI analyses reveal evidence for increased responsivity to lower face stimulation in amputees versus controls. This is inconsistent with prior evidence indicating expansion of the representation of the somatotopically adjacent hemi-face into the deafferented S1 hand territory. As introduced earlier, single-unit recordings reveal neurons in S1f of unilaterally deafferented primates that respond to cutaneous stimulation of the lower face located ipsilateral to the injury (Pons et al., 1991; Florence and Kaas, 1995; Florence et al., 1998). Likewise, neuroelectric source imaging studies of human amputees report a significant medial shift, toward S1f, of responses to ipsilateral lip stimulation (Ramachandran et al., 1992; Elbert et al., 1994; Yang et al., 1994; Karl et al., 2001). While we are unaware of any fMRI studies that have addressed this issue with cutaneous stimulation, a medial shift in the location of the face representation has been reported in some (Lotze et al., 2001) but not all (Kikkert et al., 2018) studies involving lip movements.

Limitations

The conclusions that can be drawn from our data regarding the absence of a relationship between functional reorganizational changes in S1f of chronic amputees and behaviour are limited. First, our behavioural measures of sensory hand function are limited to estimates of tactile acuity, and to a relatively small number of participants. It is possible that other tests of hand function, including other measures of tactile, proprioceptive, or motor abilities may be found to relate to the increased ipsilateral fMRI responsivity to hand stimulation we have found, and it will be of value to replicate the current findings with larger sample sizes. One particularly important next direction may be to evaluate measures of active touch (Lederman and Klatzky, 2009; Prescott et al., 2011).

Equally, it is possible that other ways of measuring pain and/or referred sensations, or brain function may reveal different results. Also, how our findings relate to the restoration of hand function following less-severe injuries such as nerve transection is unclear. It may be the case that markers of functional brain reorganization following deafferenting injuries, including increased ipsilateral S1 responses, are found to have consequences for the recovery of the injured hand function (Lundborg and Rosen, 2007; Taylor et al., 2009; Rath et al., 2011; Rosen et al., 2012; Chemnitz et al., 2015). There is ample need for continued research in this area.

Conclusions

According to animal models, unilateral deafferenting injuries induce bilateral reorganizational changes in the somatosensory cortex by altering the interhemispheric balance. These investigations do not address the functional consequences of these changes, however, nor their duration. The current study provides the first extension of this work to humans, revealing that tactile stimulation of the intact hand of chronic amputees results in significant response increases in specific regions of sensory cortex formerly dedicated to processing inputs from the now missing hand. Our failure to detect concurrent changes in hand sensibility cautions against assuming that such reorganizational changes in sensory cortex are functionally relevant. We concur with the conclusions put forward by Moore and Schady (2000) regarding the elusive nature of evidence for functional plasticity following deafferenting injuries. Given the substantial theoretical and clinical significance of this issue, there is need for additional research.

Our results also illustrate that individual variability of brain and behavioral responses in both amputees and controls is the rule rather than the exception. Coupled with the fact that preinjury data is very rarely available in cases of traumatic injury (cf. (Pascual-Leone et al., 1996), this natural variation presents an obstacle to formulating simple conclusions about the functional significance of cortical reorganization on the basis of central tendencies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke at the National Institutes of Health (grant # NS0833770, and the United States Department of Defense (grant # W81XWH-13-1-0496) awarded to S.H.F. S.H.F, K.F.V. and B.P. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to data collection and analysis. Figures were prepared by K.F.V., P-W. C., and N.M.

Footnotes

No conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Berlot E, Prichard G, O’Reilly J, Ejaz N, Diedrichsen J (2019) Ipsilateral finger representations in the sensorimotor cortex are driven by active movement processes, not passive sensory input. J Neurophysiol 121:418–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkman A, Rosén B, van Westen D, Larsson E-M, Lundborg G (2004) Acute improvement of contralateral hand function after deafferentation. NeuroReport 15:1861–1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov S, Smith J, Frey SH (2012) Former hand territory activity increases after amputation during intact hand movements, but is unaffected by illusory visual feedback. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 26:604–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braune S, Schady W (1993) Changes in sensation after nerve injury or amputation: the role of central factors. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 56:393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calford M, Tweedale R (1990) Interhemispheric transfer of plasticity in the cerebral cortex. Science (New York, NY) 249:805–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calford MB, Tweedale R (1988) Immediate and chronic changes in responses of somatosensory cortex in adult flying-fox after digit amputation. Nature 332:446–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemnitz A, Weibull A, Rosen B, Andersson G, Dahlin LB, Bjorkman A (2015) Normalized activation in the somatosensory cortex 30 years following nerve repair in children: an fMRI study. Eur J Neurosci 42:2022–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbert T, Flor H, Birbaumer N, Knecht S, Hampson S, Larbig W, Taub E (1994) Extensive reorganization of the somatosensory cortex in adult humans after nervous system injury. Neuroreport 5:2593–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florence SL, Kaas JH (1995) Large-scale reorganization at multiple levels of the somatosensory pathway follows therapeutic amputation of the hand in monkeys. J Neurosci 15:80838095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florence SL, Taub HB, Kaas JH (1998) Large-scale sprouting of cortical connections after peripheral injury in adult macaque monkeys. Science 282:1117–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galer BS, Jensen MP (1997) Development and preliminary validation of a pain measure specific to neuropathic pain: the Neuropathic Pain Scale. Neurology 48:332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer S, Schormann T, Mohlberg H, Zilles K (2000) Areas 3a, 3b, and 1 of human primary somatosensory cortex. Part 2. Spatial normalization to standard anatomical space. Neuroimage 11:684–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson GO, Craig JC (2002) Relative roles of spatial and intensive cues in the discrimination of spatial tactile stimuli. Percept Psychophys 64:1095–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve DN, Fischl B (2009) Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary-based registration. NeuroImage 48:63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamzei F, Rijntjes M, Dettmers C, Glauche V, Weiller C, Buchel C (2003) The human action recognition system and its relationship to Broca’s area: an fMRI study. Neuroimage 19:637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Li N, Zeiler SR, Pelled G (2013) Peripheral nerve injury induces immediate increases in layer v neuronal activity. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 27:664–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JP, Katz J, Davis KD (2003) The effect of tactile and visual sensory inputs on phantom limb awareness. Brain 126:579–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KO, Phillips JR (1981) Tactile spatial resolution. I. Two-point discrimination, gap detection, grating resolution, and letter recognition. J Neurophysiol 46:1177–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG (2000) Cortical and subcortical contributions to activity-dependent plasticity in primate somatosensory cortex. Annual Review of Neuroscience 23:1–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH (1991) Plasticity of sensory and motor maps in adult mammals. Annu Rev Neurosci 14:137–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Merzenich MM, Killackey HP (1983) The reorganization of somatosensory cortex following peripheral nerve damage in adult and developing mammals. Annu Rev Neurosci 6:325–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl A, Birbaumer N, Lutzenberger W, Cohen LG, Flor H (2001) Reorganization of motor and somatosensory cortex in upper extremity amputees with phantom limb pain. J Neurosci 21:3609–3618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kew JJ, Ridding MC, Rothwell JC, Passingham RE, Leigh PN, Sooriakumaran S, Frackowiak RS, Brooks DJ (1994) Reorganization of cortical blood flow and transcranial magnetic stimulation maps in human subjects after upper limb amputation. Journal of Neurophysiology 72:2517–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkert S, Johansen-Berg H, Tracey I, Makin TR (2018) Reaffirming the link between chronic phantom limb pain and maintained missing hand representation. Cortex 106:174–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegeskorte N, Simmons WK, Bellgowan PS, Baker CI (2009) Circular analysis in systems neuroscience: the dangers of double dipping. Nat Neurosci 12:535–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederman SJ, Klatzky RL (2009) Haptic perception: a tutorial. Atten Percept Psychophys 71:1439–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Downey JE, Bar-Shir A, Gilad AA, Walczak P, Kim H, Joel SE, Pekar JJ, Thakor NV, Pelled G (2011) Optogenetic-guided cortical plasticity after nerve injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:8838–8843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotze M, Flor H, Grodd W, Larbig W, Birbaumer N (2001) Phantom movements and pain. An fMRI study in upper limb amputees. Brain 124:2268–2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundborg G, Rosen B (2007) Hand function after nerve repair. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 189:207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIver K, Lloyd DM, Kelly S, Roberts N, Nurmikko T (2008) Phantom limb pain, cortical reorganization and the therapeutic effect of mental imagery. Brain 131:2181–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makin TR, Cramer AO, Scholz J, Hahamy A, Henderson Slater D, Tracey I, Johansen-Berg H (2013) Deprivation-related and use-dependent plasticity go hand in hand. Elife 2:e01273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzack R (1987) The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain 30:191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzenich MM, Kaas JH, Wall J, Nelson RJ, Sur M, Felleman D (1983) Topographic reorganization of somatosensory cortical areas 3b and 1 in adult monkeys following restricted deafferentation. Neuroscience 8:33–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CE, Schady W (2000) Investigation of the functional correlates of reorganization within the human somatosensory cortex. Brain 123 ( Pt 9):1883–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC (1971) The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9:97–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Leone A, Peris M, Tormos JM, Pascual AP, Catalá MD (1996) Reorganization of human cortical motor output maps following traumatic forearm amputation. NeuroReport 7:2068–2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawela CP, Biswal BB, Hudetz AG, Li R, Jones SR, Cho YR, Matloub HS, Hyde JS (2010) Interhemispheric neuroplasticity following limb deafferentation detected by resting-state functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging (fcMRI) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Neuroimage 49:2467–2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelled G, Chuang KH, Dodd SJ, Koretsky AP (2007) Functional MRI detection of bilateral cortical reorganization in the rodent brain following peripheral nerve deafferentation. Neuroimage 37:262–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelled G, Bergstrom DA, Tierney PL, Conroy RS, Chuang KH, Yu D, Leopold DA, Walters JR, Koretsky AP (2009) Ipsilateral cortical fMRI responses after peripheral nerve damage in rats reflect increased interneuron activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:14114–14119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, and Boldrey E. (1937) Somatotopic motor and sesnory representation in the cerebral cortex of man as studied by electrical stimulation. Brain 60:389–443. [Google Scholar]

- Philip BA, Frey SH (2014) Compensatory changes accompanying chronic forced use of the nondominant hand by unilateral amputees. J Neurosci 34:3622–3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons TP, Garraghty PE, Ommaya AK, Kaas JH, Taub E, Mishkin M (1991) Massive cortical reorganization after sensory deafferentation in adult macaques. Science 252:1857–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott TJ, Diamond ME, Wing AM (2011) Active touch sensing. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 366:2989–2995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragert P, Vandermeeren Y, Camus M, Cohen LG (2008) Improvement of spatial tactile acuity by transcranial direct current stimulation. Clinical Neurophysiology 119:805–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran VS, Rogers-Ramachandran D, Stewart M (1992) Perceptual correlates of massive cortical reorganization. Science 258:1159–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran VS, Rogers-Ramachandran D, Cobb S (1995) Touching the phantom limb. Nature 377:489–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath J, Klinger N, Geissler A, Hollinger I, Gruber S, Wurnig M, Hausner T, Auff E, Schmidhammer R, Beisteiner R (2011) An fMRI marker for peripheral nerve regeneration. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 25:577–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen B, Chemnitz A, Weibull A, Andersson G, Dahlin LB, Bjorkman A (2012) Cerebral changes after injury to the median nerve: a long-term follow up. J Plast Surg Hand Surg 46:106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schady W, Braune S, Watson S, Torebjork HE, Schmidt R (1994) Responsiveness of the somatosensory system after nerve injury and amputation in the human hand. Ann Neurol 36:68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Bogdanov S, Watrous S, & Frey SH (2009) “Rapid digit mapping in the human brain at 3T.” In: 17th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Magnet Resonance (ISMRM) in Medicine. Honolulu [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM (2004) Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 23 Suppl 1:S208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KS, Anastakis DJ, Davis KD (2009) Cutting your nerve changes your brain. Brain 132:3122–3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay F, Wong K, Sanderson R, Cote L (2003) Tactile spatial acuity in elderly persons: assessment with grating domes and relationship with manual dexterity. Somatosens Mot Res 20:127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boven RW, Johnson KO (1994) The limit of tactile spatial resolution in humans: grating orientation discrimination at the lip, tongue, and finger. Neurology 44:2361–2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Bermudez F, Johnson KO (2002) Spatial acuity after digit amputation. Brain 125:1256–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werhahn K, Mortensen J, Kaelin-Lang A, Boroojerdi B, Cohen L (2002a) Cortical excitability changes induced by deafferentation of the contralateral hemisphere. Brain 125:1402–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werhahn KJ, Mortensen J, Van Boven RW, Zeuner KE, Cohen LG (2002b) Enhanced tactile spatial acuity and cortical processing during acute hand deafferentation. Nat Neurosci 5:936–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werhahn KJ, Mortensen J, Kaelin-Lang A, Boroojerdi B, Cohen LG (2002c) Cortical excitability changes induced by deafferentation of the contralateral hemisphere. Brain 125:14021413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesselink DB, van den Heiligenberg FM, Ejaz N, Dempsey-Jones H, Cardinali L, Tarall-Jozwiak A, Diedrichsen J, Makin TR (2019) Obtaining and maintaining cortical hand representation as evidenced from acquired and congenital handlessness. Elife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolrich MW, Ripley BD, Brady JM, Smith SM (2001) Temporal Autocorrelation in Univariate Linear Modelling of FMRI Data. NeuroImage 14:1370–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang TT, Gallen CC, Ramachandran VS, Cobb S, Schwartz BJ, Bloom FE (1994) Noninvasive detection of cerebral plasticity in adult human somatosensory cortex. Neuroreport 5:701–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.