Abstract

Objective:

Healthcare provider recommendation is a key determinant of HPV vaccination. We developed an online training program for providers that addressed vaccine guidelines, hesitancy to strongly recommend the vaccine and reluctance to discuss HPV as a sexually transmitted infection.

Design:

Single group evaluation with three waves. Providers completed a 29-item electronic survey with closed and open-ended response options after course completion.

Setting:

Pediatric and family medicine practices in North Carolina.

Participants:

Prescribing clinicians (MD, DO, FNP, PA) who serve preteens ages 11-12. In Wave III we expanded our communities to include nursing and medical staff.

Intervention:

An asynchronous online course to promote preteen HPV vaccination. Topics included HPV epidemiology, vaccine recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), preteen-provider-parent communication, topics about hesitancy to seek vaccination, subjects related to sexual health, and practice-level strategies to increase vaccination rates. The course, approved for 12 CME and CNE credits, was live for 4 weeks and available on-demand for 3 additional months.

Main Outcome Measures:

Provider-reported change in vaccine communication, perceptions of course content in improving practice, and satisfaction with materials.

Results:

A total of 113 providers from 25 practices enrolled in the course and 69 (61%) completed an evaluation. Providers spent an average of 6.3 hours on the course and rated the CDC-ACIP website and multiple resources on hesitancy and communication about STI vaccines most highly of all materials across the 3 waves. Almost all (96%) agreed the course will improve their practice. About half of all participants said they were either ‘much more likely’ (28%) or ‘more likely’ (19%) to recommend the vaccine after course participation.

Conclusions:

An online format offers a highly adaptable and acceptable educational tool that promotes interpersonal communication and practice-related changes known to improve providers’ vaccine uptake by their patients.

Keywords: HPV vaccine, online education, adolescent medicine, evaluation

Introduction

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the United States, causes genital warts, and is associated with 33,700 newly diagnosed cervical, vaginal, vulvar, anal, penile, mouth and throat cancers in the US each year.1 The US Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends routinely vaccinating 11-12 year olds against HPV, when immune response is highest.2 Despite the availability of a safe and effective vaccine that prevents cancer and an STI, in 2017, coverage for ≥1 dose of HPV vaccine was only 65.5%, and 48.6% of adolescents were up to date (UTD) with a 2 or 3 dose HPV vaccine series. By comparison, ≥1 dose of MenACWY reached 85.1%, and coverage with Tdap remained stable at 88.7%.3 Suboptimal HPV vaccination rates are attributed in part to persistent parental hesitation about vaccine safety, efficacy, its association with an STI4 and provider hesitation to discuss the vaccine with parents and preteens.5,6 HPV vaccine rates also differ by geographical area. Coverage with ≥1 dose of HPV vaccine was 10.8 percentage points lower among adolescents living in non-MSAs and 7.0 percentage points lower among those living in MSA non-principal cities compared with those living in MSA principal cities. This disparity means years of catching up to the standard vaccination schedule.

HPV vaccination has undergone multiple changes in response to new evidence since its introduction in 2006. This includes the release of new vaccine products (ie., HPV-9 vaccine), a revised schedule for the shot series, a reduction from 3 to 2 shots to complete the series, and an expanded recommendation from female-only to females and males.7 Effective communication is essential as provider recommendation is the strongest predictor of vaccine uptake.5,6,8,9

Synchronous online training is supported in the literature as an effective training strategy for healthcare providers.10 In addition, the use of asynchronous training is growing in popularity in healthcare due to its sustainability, cost-effectiveness, and accessibility.11 Online training has been shown to be as efficacious as other methods of training in acquiring knowledge, affecting clinical behavior, fostering confidence, and building health behavior counseling skills (e.g. motivational interviewing) among health care professionals.10,12,13 Online training is particularly advantageous when the target community has extensive barriers to participate in on-site training learning, such as distance, time, and cost. 14,15

In this project, we used the Health Belief Model16 to guide development of an online, interactive, self-paced training program for healthcare providers. Its purpose was to increase HPV vaccine knowledge, enhance interpersonal communication skills, and offer systems-level strategies to support HPV vaccination for 11-12 year olds in North Carolina. This approach was based on formative research and evaluations of prior social marketing interventions with parents of preteens in North Carolina.17,18 This paper describes our evaluation findings from three annual course waves, 2015-2017.

Methods

Protect Them Intervention

This evaluation is part of a larger, 4-year intervention study which aimed to increase HPV vaccination rates among 11-12 year olds through enhanced provider communication with parents and preteens. We developed a set of practice-based communication tools grounded in the Health Belief Model to normalize HPV vaccine discussions about STIs among providers, parents and preteens. An asynchronous, online course was the main provider-focused strategy for the intervention and complemented additional practice, parent, and preteen-focused strategies, including print materials, web-based information, a video game for preteens and an interactive decision aid for parents.19

Online Provider Training Description

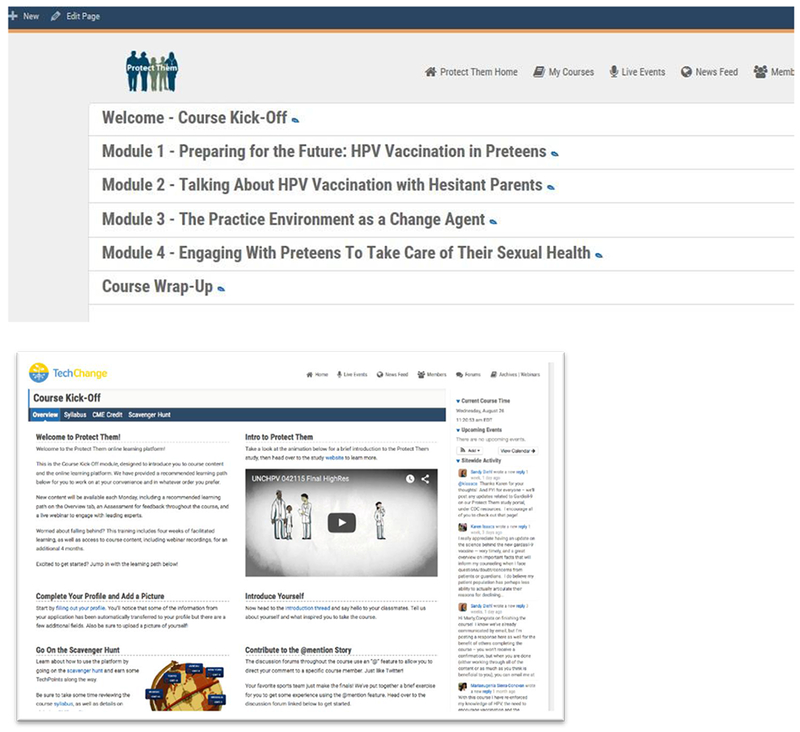

Three waves of providers participated in the Protect Them course from 2015-17. The asynchronous course was delivered live for a 4-week period each wave and then on-demand for an additional 3-month period. Providers started the course June-September on a rolling basis to coincide with back-to-school demand for immunizations. Researchers had full access to the platform, hosted by an external vendor20 for on-demand updates to content. Figure 1 shows examples of the course platform and format. The platform used interactive features, including gamification21 and course discussion. Gamification elements included points for logging in, participating in each learning activity, exploring the site through a scavenger hunt and completing evaluations. Gamification offers the course variety and friendly format appreciated by busy providers and brings them back to the training on their own time. This platform provides far-reaching, flexible provider education that can cross disciplines.

Figure 1.

Course Format and Platform

TechChange Inc. Protect Them. In:2014-2018.

Course objectives were to: (1) state current clinical recommendations about HPV vaccination; (2) use successful communication techniques to (a) introduce HPV vaccination to parents and preteen boys and girls; (b) address parents’ questions and concerns about talking with preteen boys and girls about protection against an HPV infection; (c) provide a strong recommendation for HPV vaccine at age 11-12; and (3) demonstrate intent to implement one or more practice-level technology innovations to improve HPV vaccine administration and series completion (for example, follow up text messages to remind parent about the second dose).

The course used multiple adult learning methods to advance knowledge and build skills. Providers could engage in reading(s), questions about the reading, live webinars (later archived) featuring an expert with an opportunity to submit real time questions via the course platform, videos on interpersonal communication strategies with role plays among the provider, parent and preteen, and a written final reflection of what was gained from the training and how the participant has (or intends to) apply what they have learned.

We addressed cues to action for both patients and providers in our intervention protocol and in our provider training. Practices were expected to display our print materials (posters and brochures) in their practice setting and use them in conversations with preteens and parents as a condition of participating in the study. These materials served as environmental cues to discuss the vaccine and to vaccinate, for both audiences. Our training reinforced this concept in multiple ways. Our first webinar promoted the use of our Protect Them materials and outlined multiple, multi-level strategies to support vaccination from a systems perspective, including chart reminders as a cue to action. Our role play videos in a subsequent module modeled an exam room with the poster prominently displayed on the wall. Furthermore, our module, ‘The Practice Environment as a Change Agent’ offers evidence to support the use of patient appointment reminders, yet another cue to action.

Self-efficacy for providers was strengthened through multiple channels. For example, we offered the most current information at the time to support the clinical need for vaccination. Providers could then knowledgeably communicate this information with parents and preteens. We also included several strategies to address parental hesitation around vaccination. Our “Talking about HPV Vaccination with Hesitant Parents” module included a webinar and a role-play video that modeled specific language to use when addressing vaccine hesitation. A reading offered an overview of motivational interviewing techniques to further build interpersonal communication skills. These types of strategies, in combination, raised provider self-efficacy around vaccine communication. While we did not explicitly evaluate HBM constructs, we see evidence of this reflected in our open-ended quotes from providers.

Self-efficacy for parents is not measured in this evaluation, however our print materials address self-efficacy in action-oriented language that encourages parents to seek vaccination. Our assumption was that parental and preteen self-efficacy is built through enhanced patient-provider communication, coupled with interactive tools to aid in informed decision making

Table 3 [submitted as supplemental digital content] presents more detailed information about course content. Modules addressed HPV epidemiology and vaccine recommendations, provider communication, particularly with hesitant parents; vaccination in the context of optimal sexual health, and practice-level strategies to increase vaccination rates. Content is included as Table 3 as a list of key websites and articles in the course. Providers could choose what material best suited their learning needs, and were asked to complete a minimum of 2 hours and up to 12 hours of training. Up to 12 CME or CNE credits were available to participants based on level of participation.

Evaluation

We evaluated the Protect Them course using a single group post-test design. The evaluation was intended to function as an iterative process, with feedback from the previous wave informing content for future waves. Our university’s Institutional Review Board approved this study (UNC IRB #14-1891). All health care providers completed an online study consent prior to enrolling in the study.

Participants and Setting

Providers (MDs, DOs, PAs, and FNPs) enrolled in Waves I and II of the Protect Them study. In Wave III, we expanded our audience to also include nursing and medical staff. To enroll, participants needed to serve patients 11-12 years old and affirm that they communicate about and/or administer HPV vaccine. We recruited primary care practices that reported to the North Carolina Immunization registry (NCIR) and had at least 100 11-and 12-year olds who had not completed the HPV series. We recruited practices in random order from the NCIR list. We first faxed a study introduction to the address on the NCIR list. We followed up via phone call to the practice representative to determine interest. One of the key communication tools was an online interactive course for providers and nurses and with up to 12 CME or CNE credits. We asked practices to commit 50% of their providers to enroll in the training.

Measurement and Analyses

Clinicians completed an electronic evaluation form that was embedded within the Protect Them platform following their completion of the course. Completion was self-determined according to what materials the participant elected to study. The number of hours could be measured. In Wave I, items were completed after each module and a short series of (post-test) questions at the end of the course. In Waves II and III, all items were offered in a single post-test form. Most items evaluated satisfaction with course materials and course activities (e.g., “…[use] techniques you learned to answer parents’ concerns about HPV vaccination”) using a 3-point Likert scale (very relevant/useful to not relevant/useful) and a fourth option, ‘not applicable’ for participants who did not engage with that particular resource. We assessed overall course satisfaction (e.g., “my overall expectations of this course were met”) using a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree).

Two items measured influence on vaccination practices (e.g., “the information presented will improve/enhance my practice”; and “how much effect does this course have on your likelihood to recommend the vaccine…”). Open-ended items allowed participants to reflect on course impact (e.g, “What changes have you made (or plan to make) in your practice as a result of participating in this course?”).

Most items were identical for all waves. We adapted the evaluation after each wave to reflect change in course materials; thus some items were evaluated only once or twice over the three waves. Finally, participants completed 6 post-test knowledge questions that covered key points from the course (eg., “HPV vaccine can be given at the same visit as other recommended vaccines.”). Providers needed to score at least 80% on these questions to claim CME/CNE credit. Four questions were multiple choice and two were true/false. Providers had unlimited opportunities to re-answer incorrect questions.

We conducted univariate and bivariate analyses to describe participant feedback to materials and perceived changes in behavior (SAS v9.4).

Results

Course participants

A total of 113 providers from 25 practices enrolled in the course and 69 (61%) completed an evaluation (see Table 1 for participant characteristics). Participants received up to 6 reminders to participate in the course and complete an evaluation. Providers spent an average of 6.3 hours (4.0 sd, range 1–12 hours) on the course, with PAs and FNPs spending the most time (8.1 hours) and MD/DOs spending the least (5.6 hours). Nurses spent an average of 7.5 hours on the course. Wave 3 inclusion criteria expanded to include medical staff such as RNs, LPNs, and Medical Assistants who interact with patients and who often administer the vaccinations. Five medical staff in Wave 3 enrolled in the study, and of those, two enrolled in and completed the course. One was an RN, the other was an LPN, who is represented in the ‘other’ row in wave three.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Wave 1 (n=34)* | Wave 2 (n=22)* | Wave 3 (n=13)* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean; SD; (range)) | 40.3; 12.2; (23-64) | 51.5; 10.5; (33-75) | 50.4; 6.2; (40-63) | |||

| Degree | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| MD/DO | 21 | 70 | 14 | 66.7 | 5 | 38.5 |

| PA | 2 | 6.7 | 1 | 4.8 | 1 | 7.7 |

| NP | 6 | 20 | 5 | 23.8 | 5 | 38.5 |

| RN | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1 | 7.7 |

| Other | 1 | 3.3 | 1 | 4.8 | 1 | 7.7 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 24 | 88.9 | 16 | 80 | 10 | 76.9 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2 | 7.4 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 1 | 3.7 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 23.1 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 29 | 85.3 | 14 | 63.6 | 12 | 92.3 |

| Male | 5 | 14.7 | 8 | 36.4 | 1 | 7.7 |

| Graduation Year (highest clinical degree) | ||||||

| Before 2000 | 10 | 29.4 | 15 | 68.2 | 8 | 61.5 |

| 2000-2010 | 6 | 17.7 | 6 | 27.3 | 3 | 23.1 |

| 2011-2018 | 18 | 52.9 | 1 | 4.6 | 2 | 15.4 |

| Specialty | ||||||

| Peds | 10 | 76.9 | ||||

| Family Medicine | 3 | 23.1 | ||||

numbers may not add to total due to missing data

Practices included 42% private insurance, 39% public, 10% not or underinsured and 9% unknown. In response to our pre-post survey, 22% of the providers reported exposure to other HPV vaccine uptake training.

Course outcomes

Table 2 presents course outcomes. Almost all providers ‘strongly agreed’ or ‘agreed’ that the course met their expectations (96%) and will improve or enhance their practice (96%). Almost half (46%) of providers said they were ‘much more likely’ or ‘more likely’ to recommend the vaccine to preteens and parents after participating in the course, 43% indicated they ‘were no more likely’ because they were already strongly recommending the vaccine, and 10% were ‘neutral’ or ‘no more likely.’ Even though 43% of participants were already strongly recommending the HPV vaccine, the course provided in depth knowledge and reinforced confidence in discussing and recommending the vaccine. For example, short videos were included for providers to witness role model discussions with parents and with both younger and older preteens. To examine whether course dose affected outcomes, we created two dichotomous variables: an outcome variable that was defined as ‘more likely’ to recommend the vaccine (ie., all ‘much more likely or ‘more likely’ responses) or ‘no effect’ (ie., all ‘neutral’ or ‘no more likely’ responses). We excluded providers who responded ‘no more likely’ because they were already strongly recommending the vaccine. Providers who spent 6 or more hours on the course were defined as ‘high’ engagers with the remaining defined as ‘low’ (ie., fewer than 6 hours). Outcomes did not vary significantly based on the number of hours spent on the course (Fisher’s Exact test p=.27).

Table 2.

Course Outcomes

| Wave I | Wave II | Wave III | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (34) | % | N (22) | % | N (13) | % | |

| My overall expectations of this course were met. | ||||||

| Strongly Agree | 26 | 76.47 | 10 | 45.5 | 4 | 30.8 |

| Agree | 7 | 20.59 | 10 | 45.5 | 9 | 69.2 |

| Neutral | 1 | 2.94 | 1 | 4.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.6 | 0 | 0 |

| The information presented will improve/enhance my practice. | ||||||

| Strongly Agree | 23 | 67.65 | 9 | 40.9 | 4 | 30.8 |

| Agree | 9 | 26.47 | 12 | 54.6 | 9 | 69.2 |

| Neutral | 2 | 5.88 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | 0 | 1* | 4.6 | 0 | 0 |

| How much effect does this course have on your likelihood to recommend the vaccine to preteens and their parents? | ||||||

| Much more likely | 15 | 44.1 | 2 | 9.1 | 2 | 15.4 |

| No more likely – I was already strongly recommending the vaccine | 13 | 38.2 | 11 | 50.0 | 6 | 46.2 |

| No more likely – the course hasn’t affected me | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7.7 |

| More likely | 4 | 11.8 | 7 | 31.8 | 2 | 15.4 |

| Neutral | 2 | 5.9 | 2 | 9.1 | 2 | 15.4 |

numbers may not add to total due to missing data

Open-ended survey responses to the question, “What features of the course influenced your likelihood to vaccinate, and if the course didn’t affect you, why not?” suggested that for some providers, the course reinforced existing knowledge and behaviors (e.g., “course reinforces what I already know”; “[I was] already recommending”). For others, it increased vaccine knowledge and confidence in discussing and/or recommending the vaccine (e.g., “I knew zero going in”; “I feel more comfortable taking with parents”; “I have no worries now introducing the discussion about the vaccine”; “statistics strengthens my resolve to encourage vaccination, changed my thinking”; “safety data and need is high – learned this in course, swayed my opinion as far as the number and types of cancer this vaccine can protect against”; “helped solidify my understanding and views, better understanding of risks of getting vs not getting, made me feel more comfortable how to address fears and hesitancy, info on boys’ vaccine strengthens my resolve to encourage vaccination”; “data that show patients are more likely to vaccinate based on provider recommendation changed my thinking.”).

Figure 2 summarizes the proportion of providers across the three waves who engaged with materials and their overall satisfaction, by type of material. Key websites (eg., CDC-ACIP), a 1-hour webinar on interpersonal communication, articles on vaccine efficacy, and two short videos that modeled HPV and vaccine communication with a hesitant parent and with a preteen alone were rated most highly of all course materials (data not shown). In open-ended responses, providers enjoyed the course variety and format (e.g., “Liked moving at self-pace, nice to have a variety for different learning styles”) while suggestions for improvement focused mainly on time or quality issues (e.g., ‘some technical glitches’; ‘shorter webinars, even if there are more of them’; ‘a more focused course’). Variation in participant make-up was influenced to some degree by the regional variation in enrollment across the three waves. Wave I included practices located within a large metropolitan area with two large medical schools mainly in the center of the state. Additionally, we enrolled an academic practice with a large resident population in Wave 1. Waves 2 and 3 enrolled practices in the eastern and western areas of the state.

Figure 2.

Ratings of course materials by participants.

Because we had little variation in our 3 main outcomes (ie., almost all agreed or strongly agreed) and small numbers we did not examine if these outcomes differed across group characteristics. That said, beyond describing our participants, we collected these data with the intention of using these variables to assess differences in outcomes.

Providers cited multiple changes or intended changes in interpersonal communication, their practice environment, and in office systems (Table 4: Potential changes in your practice) [submitted as supplemental digital content]

Discussion

Healthcare providers play the primary influential role in parents’ decisions to have their adolescent children vaccinated against HPV.7 Nonetheless, missed opportunities to vaccinate against HPV at the same clinical visit with other preteen vaccines are far too frequent. Online education, like the Protect Them course, represents an effective and contemporary approach to affect provider knowledge and confidence in recommending the HPV vaccine, and addressing parent hesitation. In our evaluation, we found that almost half of all providers were more likely to recommend the HPV vaccine to parents and preteens following participation in the course. Time spent on the course did not affect this outcome. Providers who responded to our open-ended questions noted increased knowledge and comfort in addressing concerns from hesitant parents, addressing sexual health, and in placing equal importance on all preteen vaccines as a result of course participation. Providers also reported practice-related changes known to improve vaccine uptake, such as chart prompts and displaying materials to serve as cues to action.7

Our goals were to equip providers with the knowledge and skills to talk with preteens about prevention of STIs and cancer through HPV vaccination and to strongly recommend the vaccine to preteens and their parents. Current online approaches to disseminating HPV vaccine information to providers focus mainly on cancer prevention messages1,22 Fewer model interpersonal communication skills or give specific approaches to address hesitation or guidance on practice-based strategies to improve vaccination.23 Our training demonstrated the feasibility and effectiveness of using an asynchronous online platform that is user friendly, adaptable, scalable. Furthermore, and in contrast to many other trainings, it extended the focus to include sexual health and STI prevention. Our self-paced and flexible course allowed participants to choose and tailor materials to individual learning needs.

Communication technologies and networks are increasingly expanding in their sophistication and capacity, and new applications are enhancing the ways in which individuals interact. Healthcare providers can now use online interactive materials to stay updated on the rapidly evolving field of HPV vaccination, enhance vaccine conversations with parents and preteens, and share experiences with other providers. The Health Belief Model (HBM) is commonly used in patient education24 and has been incorporated in interventions that positively affect vaccination behavior.25 According to HBM, health behavior change is predicted by the patient’s perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, benefits and barriers associated with the health behavior, cues to action, and self-efficacy.16,25,26 HPV vaccination uptake and series completion can improve if providers effectively guide the patient to recognize and evaluate the threat and severity of HPV and the benefits of the HPV vaccine.

Our evaluation had some limitations. Participants were part of a larger study and thus may be different than providers who are offered the course through continuing education opportunities. Their response to the course may be different. Secondly, we were not able to link changes in provider behavior to vaccine outcomes because we measured outcomes with registry data (published in a separate article) rather than provider-linked practice-level data.19 Finally, we used a design that is common in course evaluation but has limits in establishing strong internal validity. We did not use a pretest, we have no control group, limited response and all data are self-reported. Despite those limitations, this is one of the first evaluations of HPV online education. Future studies can link provider training with provider-level practice data available from EMR to more closely examine the relationship between provider training and HPV vaccine outcomes.

Our provider training is key to the Protect Them intervention, a communication strategy funded by NIH to normalize HPV vaccination for preteens. Adaptability and flexibility are hallmarks of the training approach. The materials will be available for public use once the study is concluded. This online format offers a highly adaptable and acceptable educational tool that promotes interpersonal communication with parents and preteens and practice-related changes such as reminder messages known to improve vaccine uptake.

Supplementary Material

Implications for Policy and Practice.

Promising model and platform for far-reaching, flexible provider education that can cross disciplines

Model can build skills through video role modeling; increase knowledge through key reputable peer reviewed articles and leading websites;

Potential for individual, interpersonal, and practice level change

Useful in fields that are rapidly evolving

New STI vaccines are emerging and this could translate to these clinical developments in disseminating and fostering implementation of new innovations.

Acknowledgements

We thank Christopher Neu, Emily Fruchterman, Sedinam Worlanyo and Kendra Keith from TechChange, Inc., Washington DC, for creating and managing the learning platform and for technical advice, and Dr. Tracey Zola, Candidate for Master of Science in Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, for her contributions to the course content.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH, NIAID, R1R01AI113305-04 Cates, Joan R. (PI), Coyne-Beasley, Crandell, Diehl, Fuemmeler, Trogdon, Co-Investigators).

Course content on Internet and Publications

1. Website Visit 1 - http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/hpv/vac-faqs.htm

Facts about vaccines

2. Website Visit 2 - http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/index.html

CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that decides recommendations on vaccines. Policy notes on HPV9.

3. Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-Dose Schedule for Human Papillomavirus Vaccination — Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices MMWR. 2016;65(49);1405-8.

4. Markowitz, L. E., et al. (2016). “Prevalence of HPV after introduction of the vaccination program in the United States.” Pediatrics 137(2): e2 0151968.

5. Gottlieb, S. L., et al. (2014). “Toward global prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs): The need for STI vaccines.” Vaccine 32(14): 1527-1535.

6. Allison M.A., et al. (2016) “Primary Care Physicians’ Perspectives About HPV Vaccine.” Pediatrics 137(2): e20152488.

7. Sadaf A, Richards JL, Glanz J, Salmon DA, Omer SB. A systematic review of interventions for reducing parental vaccine refusal and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2013;31(40):4293-4304.

8. Hofstetter AM, Stockwell MS, Al-Husayni N, et al. HPV vaccination: Are we initiating too late? Vaccine. 4/7/ 2014;32(17):1939-1945.

9. Tellerman K. Catalyst for Change: Motivational interviewing can help parents help their kids. Contemporary Pediatrics. December 2010.

10. Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jacson C et al. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatrics. 12:154.

11. Cates, J. R., et al. (2014 PMID: 2525843). “Partnering With Middle School Students to Design Text Messages About HPV Vaccination.” Health Promotion Practice

12. Hofstetter, A. M. and S. L. Rosenthal (2014). “Health care professional communication about STI vaccines with adolescents and parents.” Vaccine 32(14): 1616-1623.

13. Hofstetter, A. M. and S. L. Rosenthal (2014). “Health care professional communication about STI vaccines with adolescents and parents.” Vaccine 32(14): 1616-1623.

14. Matheson, E. C., et al. (2014). “Increasing HPV Vaccination Series Completion Rates via Text Message Reminders.” Journal of Pediatric Health Care 28(4): e35-e39.

15. Thompson, D., et al. (2012). A serious video game to increase fruit and vegetable consumption among elementary aged youth. JMIR Associates.

16. Gable J, Eder J, Noonan K, Feemster K. Increasing HPV vaccination rates among adolescents: Challenges and opportunities. Evidence to Action. Winter 2016. Pages 13-14 only.

Contributor Information

Joan R. Cates, Teaching Associate Professor in the School of Media and Journalism, and Co-Director of the Interdisciplinary Health Communication (IHC) Program, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Sandra J. Diehl, Implementation Specialist, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Bernard F. Fuemmeler, Gordon D Ginder, MD Chair in Cancer Research; Professor, Health Behavior and Policy, Associate Director, Cancer Prevention and Control, Massey Cancer Center, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Stephen W. North, Adolescent Medicine Specialist, Blue Ridge Medical Center, Spruce Pine, North Carolina.

Richard J. Chung, Adolescent Health Specialist at Duke Health, Durham NC.

Jill Forcina Hill, Associate Director, Education and Grants, Duke Cancer Network, Network Services in Duke University Health System.

Tamera Coyne-Beasley, Derrol Dawkins, MD Endowed Chair in Adolescent Medicine; Professor of Pediatrics and Internal Medicine, Division Director, University of Alabama Adolescent Medicine; Vice Chair, Pediatrics for Community Engagement. She served as the primary clinician for the study while she was at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human Papillomavirus for Clinicians,. 2018; https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm Accessed December 28, 2018.

- 2.Meites E, Kempe A. Use of a 2-Dose Schedule for Human Papillomavirus Vaccination — Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices,. MMWR. 2016;65(49):1405–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years — United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67(33):909–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vielot NA, Butler AM, Brookhart MA, Becker-Dreps S, Smith JS. Patterns of Use of Human Papillomavirus and Other Adolescent Vaccines in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2017;61(3):281–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilkey MB, McRee A- L. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: A systematic review. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2016:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selove R, Foster M, Mack R, Sanderson M, Hull PC. Using an Implementation Research Framework to Identify Potential Facilitators and Barriers of an Intervention to Increase HPV Vaccine Uptake. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2017;23(3):e1–e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:874–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss JL. Evolving Trends in Human Papillomavirus Vaccination by Sex and Time: Implications for Clinicians and Interventionists. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2017;61(3):269–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson EL, Rosen BL, Vamos CA, Kadono M, Daley EM. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: What Are the Reasons for Nonvaccination Among U.S. Adolescents? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2017;61(3):288–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullin DJ, Saver B, Savageau JA, Forsberg L, Forsberg L. Evaluation of online and in-person motivational interviewing training for healthcare providers. Families, Systems, & Health . 2016;34(4):357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.High engagement, high quality: A guiding framework for developing empirically informed asynchronous e-learning programs for health professional educators. Nursing & health sciences. 2017;19(1):126–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richmond H, Copsey B, Hall AM, Davies D, Lamb SE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of online versus alternative methods for training licensed health care professionals to deliver clinical interventions. BMC Medical Education. 2017;17(1):227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin P, Kumar S, Abernathy L, Browne M. Good, bad or indifferent: a longitudinal multi-methods study comparing four modes of training for healthcare professionals in one Australian state. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8):e021264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacNeill HMDBMF Telner DMDMCF, Sparaggis-Agaliotis ABA, Hanna EMrC. All for One and One for All: Understanding Health Professionals’ Experience in Individual Versus Collaborative Online Learning. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions Spring. 2014;34(2):102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berndt A, Murray CM, Kennedy K, Stanley MJ, Gilbert-Hunt S. Effectiveness of distance learning strategies for continuing professional development (CPD) for rural allied health practitioners: a systematic review. BMC Medical Education. 2017;17(1):117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becker MH. The Health Belief Model and Personal Health Behavior Health Education Monographs. Vol Monog. 2 San Francisco, CA: Society for Public Health Education; 1974:324–508. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cates JR, Diehl SJ, Crandell JL, Coyne-Beasley T. Intervention effects from a social marketing campaign to promote HPV vaccination in preteen boys. Vaccine. 2014;32(33):4171–4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cates JR, Shafer A, Diehl SJ, Deal AM. Evaluating a County-Sponsored Social Marketing Campaign to Increase Mothers’ Initiation of HPV Vaccine for their Pre-teen Daughters in a Primarily Rural Area. Social Marketing Quarterly. 2011;17(1):4–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cates JR, Crandell JL, Diehl SJ, Coyne-Beasley T. Immunization effects of a communication intervention to promote preteen HPV vaccination in primary care practices. Vaccine. 2018;36(1):122–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.TechChange. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamari J, Koivisto J, Sarsa H. Does Gamification Work? – A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification. Paper presented at: In proceedings of the 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,; January 6-9, 2014, 2014; Hawaii, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV Vaccine - Questions and Answers. 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/questions-answers.html Accessed May 15, 2014.

- 23.Kornides ML, Garrell JM, Gilkey MB. Content of web-based continuing medical education about HPV vaccination. Vaccine. 2017;35(35, Part B):4510–4514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorig K Patient Education: A Practical Approach,. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones CL, Jensen JD, Scherr CL, Brown NR, Christy K, Weaver J. The Health Belief Model as an Explanatory Framework in Communication Research: Exploring Parallel, Serial, and Moderated Mediation. Health Communication. 2015;30(6):566–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice (pp. 45–66). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.