Abstract

Background:

Extensive research indicates that having a positive family history of alcohol use disorder (FHP) and impulsivity are two risk factors for problem drinking. To our knowledge, no study has investigated which facets of impulsivity interact with family history to increase risk for problem drinking. The goal of this study was to 1) examine whether FHP individuals with higher levels of impulsivity are more likely to engage in problematic drinking, and 2) identify which facets of impulsivity interact with FHP to increase risk for problems.

Methods:

The data consisted of a combined sample of 757 participants (50% female, 73% White, mean age = 32.85, SD = 11.31) drawn from the Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center and the Center for the Translational Neuroscience of Alcohol. Analyses of covariance and cumulative logistic regression models investigated the association of family history and impulsivity-related traits with drinking quantity, frequency, and alcohol-related problems. Models were adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnic group, education level, and data source.

Results:

Significant interactions between impulsivity and family history were found for measures of alcohol-related problems. Specifically, there was a stronger positive association of Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS) poor self-regulation with interpersonal (F(1,504)=6.27, p=.01) and impulse control alcohol-related problems (F(1,504)=6.00, p=.01) among FHP compared to FHN individuals. Main effects of family history and impulsivity on alcohol quantity and frequency of use and problems were also found.

Discussion:

These findings suggest that having both a family history of AUD and high BIS poor self-regulation is more strongly associated with alcohol-related consequences in the interpersonal and impulse control domains. Given the heterogeneity of impulsivity, these findings highlight the need for additional research to examine which facets of impulsivity are associated with which alcohol outcomes to narrow phenotypic risk for alcohol misuse.

Keywords: family history of alcohol use disorder, impulsivity-related traits, alcohol quantity and frequency, alcohol consequences

Introduction

Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) is a highly prevalent and disabling disorder with 14% of the population meeting current and 29% meeting lifetime DSM-5 AUD criteria (Grant et al., 2015). Understanding etiological risk factors for AUD could ultimately inform prevention and intervention efforts (Petrakis, 2017). Two key risk factors that have been identified include family history of AUD and high impulsivity. However, no study has investigated which facets of impulsivity interact with family history to increase risk for problem drinking.

Family history of AUD is one of the best-known predictors of AUD. Extensive evidence indicates those with a positive family history of AUD (FHP) are at increased risk for AUD (Cotton, 1979; Grigsby et al., 2016; Mellentin et al., 2016; Sher, 1991; Stone et al., 2012). Epidemiological data suggest approximately 22% of U.S. adults are at increased risk for developing AUD because they have at least one parent with AUD (Yoon et al., 2013). While the odds of developing AUD appears to be similar regardless of which parent has AUD (Sørensen et al., 2011), having two parents with AUD may double the risk for developing AUD in offspring (Mellentin et al., 2016; Yoon et al., 2013).

Impulsivity is another key predictor of AUD. Impulsivity is a heterogenous personality construct, which can be defined broadly as a tendency toward rash action with little forethought about the consequences (Berg et al., 2015; Dick et al., 2010; Nigg, 2016). A wealth of evidence links impulsivity with the onset and development of problem drinking (defined in these studies as frequency of alcohol use, heavy drinking, binge drinking, or consequences due to drinking) (Herman and Duka, 2018; Macpherson et al., 2010; Stautz and Cooper, 2013; Tarter et al., 1985). Given the heterogeneity of the impulsivity construct, there is a need to identify specifically which facets of impulsivity are associated with alcohol outcomes. For example, sensation seeking (defined as the tendency toward novel and stimulating activities) has been found to predict alcohol use, and negative urgency (defined as the tendency toward rash actions when experiencing strong negative emotions) – but not positive urgency (defined as the tendency toward rash actions when experiencing strong positive emotions) – has been found to predict alcohol-related problems (Curcio and George, 2011). Two meta-analytic reviews of the association of impulsivity-related traits and alcohol use and problems found several facets of impulsivity including lack of premeditation (defined as the tendency to act before thinking), lack of perseverance (defined as the tendency to quit before completing a task), sensation seeking, negative urgency, positive urgency, and reward sensitivity (defined as the tendency to engage in behaviors that are rewarding) were positively associated with both alcohol consumption and problematic alcohol use (Coskunpinar et al., 2013; Stautz and Cooper, 2013). Further, Coskunpinar and colleagues (2013) found lack of perseverance had a significantly stronger association with alcohol quantity, whereas negative urgency and positive urgency had significantly stronger associations with alcohol problems compared to the other impulsivity-related traits in the 5-factor model. These findings suggest that although each of the impulsivity-related traits investigated were associated with all the alcohol outcomes examined, the magnitude of the associations varied so it is important to differentiate which facets of impulsivity are associated with which alcohol outcomes. It remains unclear whether the association between impulsivity-related traits and alcohol outcomes varies by family history status.

Individuals with a family history of AUD often differ on phenotypic characteristics associated with AUD, including impulsivity. Several early studies indicate those with a positive family history of AUD tend to be more impulsive (e.g., Knop, Teasdale, Schulsinger, & Goodwin, 1985; Knowles & Schroeder, 1989; Mann, Chassin, & Sher, 1987; Saunders & Schuckit, 1981; Sher, 1991; Tarter et al., 1985; Windle, Windle, Scheidt, & Miller, 1995). Further, twin and family design studies consistently demonstrate a strong genetic overlap between substance use and impulsivity-related traits (e.g., Hicks et al., 2011; Krueger et al., 2002). However, not every facet of impulsivity is associated with having a family history of AUD. A recent meta-analysis on the association between family history of AUD and impulsivity-related traits found low harm avoidance (defined as the tendency to avoid danger), sensation seeking, lack of planning, and low self-control (defined as the tendency to be reckless or nonreflective) were associated with family history of AUD, and lack of perseverance and reward dependence were not (Haeny et al., Under Review). Prior research indicates that impulsivity accounts for a substantial proportion of the genetic risk for AUD (Khemiri et al., 2019; Slutske et al., 2002), and recent research suggests sensation seeking and lack of perseverance partially mediated the association between polygenic risk scores related to risky behaviors and alcohol consumption among college students (Ksinan et al., 2019). These findings suggest it is possible that specific impulsivity-related traits are more heritable than others, which could explain why impulsivity-related traits reflecting deficits in self-control were associated with family history of AUD and traits reflecting sensitivity to punishment and reward were not in the meta-analysis. Further, the meta-analytic review does not inform whether the compounding effects of both family history of AUD and impulsivity are associated with elevated risk for alcohol use and problems.

Given that a positive family history of AUD and impulsivity are independently associated with developing problem drinking, having both may confer even greater risk for problem drinking. The objective of this study was to 1) investigate the association between both family history of AUD and impulsivity on quantity and frequency of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems and 2) identify which facets of impulsivity interact with family history to increase risk for alcohol use and problems. We hypothesized that the association between impulsivity and alcohol outcomes would be positive and moderated by family history status such that the association would be stronger among FHP individuals. Based on a prior quantitative synthesis (Haeny et al., Under Review), we also hypothesized that impulsivity-related traits reflecting deficits in self-control would interact with family history to increase risk for alcohol outcomes, whereas impulsivity-related traits reflecting sensitivity to punishment and reward would not. In the event there were no significant interaction effects, we expected to replicate prior research indicating that family history of AUD and impulsivity are independently positively associated with adverse alcohol outcomes.

Methods

Participants

De-identified data were drawn from the Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center (TTURC) and the Center for the Translational Neuroscience of Alcohol (CTNA). These two data sets were combined to increase power to investigate interaction effects. TTURC data were collected from 1999-2010 with the aim of evaluating risk factors associated with failure to quit smoking to inform intervention efforts. These studies primarily enrolled current smokers seeking tobacco cessation treatment. CTNA data were collected from 2006-2011 with the objective of understanding the neurobiological risk for alcohol use disorder to inform treatment. These studies primarily enrolled current drinkers who were low or high-risk based on family history of alcohol use disorder. Demographic information for each sample is in Table 1. The combined sample for this study consisted of 757 current drinkers (50% female, 73% White, with a mean age of 32.85, SD = 11.31).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| CTNA (n = 371) |

TTURC (n = 386) |

Combined Sample (N = 757) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Female | 43.40% | 44.56% | 49.54% |

| ≥12 years of education | 98.60% | 92.11% | 95.24% |

| Age | 28.85 (9.25) | 36.65(11.76) | 32.85 (11.30) |

| Race | |||

| Black | 14.56% | 22.83% | 18.67% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4.04% | 0.54% | 2.30% |

| Native American/Alaskan | - | 1.36% | 0.68% |

| Multi-ethnic | - | 1.90% | 0.95% |

| White | 77.09% | 69.84% | 73.48% |

| Other | 4.31% | 3.53% | 3.92% |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 7.59% | 9.04% | 8.50% |

| Substance use | |||

| Alcohol use frequency | |||

| 1-11 annually | 4.23% | 20.86% | 12.76% |

| 1-3 monthly | 21.13% | 23.80% | 22.50% |

| 1-2 weekly | 26.76% | 26.20% | 26.47% |

| 3-4 weekly | 14.08% | 16.31% | 15.23% |

| 5-6 weekly | 22.54% | 6.42% | 14.27% |

| Daily | 11.27% | 6.42% | 8.78% |

| Drinks per day | |||

| 1 | 12.11% | 15.03% | 13.59% |

| 2 | 23.94% | 32.51% | 28.29% |

| 3-4 | 26.48% | 23.22% | 24.83% |

| 5-6 | 19.15% | 15.03% | 17.06% |

| 7+ | 18.31% | 14.21% | 16.23% |

| SIP alcohol consequences | |||

| Physical | 1.35 (1.86) | 0.56 (1.28) | 0.94 (1.64) |

| Interpersonal | 0.75 (1.52) | 0.42 (1.42) | 0.58 (1.48) |

| Intrapersonal | 1.46 (1.87) | 0.69 (1.56) | 1.06 (1.76) |

| Impulse control | 1.51 (1.46) | 0.72 (1.28) | 1.10 (1.43) |

| Social responsibility | 1.42 (1.99) | 0.60 (1.63) | 1.00 (1.86) |

| SIP total | 6.48 (7.67) | 2.98 (6.49) | 4.67 (67.29) |

| Current smoker | 22.10% | 82.90% | 53.10% |

| Family history of AUD | 50.67% | 43.01% | 46.76% |

| Impulsivity | |||

| BSCS: Impulse control | 13.87 (3.42) | 9.42 (3.43) | 11.58 (4.08) |

| BIS | |||

| Poor self-regulation | 8.49 (2.24) | 8.40 (2.29) | 8.44 (2.26) |

| Impulsive behavior | 7.58 (2.07) | 7.28 (2.17) | 7.42 (2.13) |

| BIS-BAS | |||

| Inhibition | 11.38(2.28) | 11.07 (2.51) | 11.21 (2.41) |

| Drive | 8.92 (1.76) | 8.82 (2.01) | 8.86 (1.90) |

Note. BSCS = Brief Self-Control Scale. BIS = Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. BISBAS = Behavioral Inhibition System/Behavioral Activation System. SIP = Short Inventory of Problems. AUD = alcohol use disorder. CTNA = The Center for the Translational Neuroscience of Alcohol sample. TTURC = The Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center sample.

Measures

In terms of demographic information, age, sex, race, and education level were collected on all participants. Alcohol consumption was assessed using the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Council Task Force on Recommended Alcohol Questions (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2003). In the current study, we examined frequency of drinking and number of drinks per day. Frequency of drinking was a six-level ordinal variable categorized as: 1 = 1-11 times a year, 2 = 1-3 times monthly, 3 = 1-2 times weekly, 4 = 3-4 times weekly, 5 = 5-6 times weekly, and 6 = every day. Number of drinks per day was a five-level ordinal variable categorized as: 1 = 1 drink, 2 = 2 drinks, 3 = 3-4 drinks, 4 = 5-6 drinks, 5 = 7 or more drinks.

Alcohol-related problems were assessed using the Short Inventory of Problems (SIP; Miller, Tonigan, & Longabaugh, 1995). The SIP is a 15-item measure assessing adverse drinking-related consequences in five domains: physical (TTURC: α = .77; CTNA: α = .84), interpersonal (TTURC: α = .88; CTNA: α = .83), intrapersonal (TTURC: α = .87; CTNA: α = .83), impulse control (TTURC and CTNA: α = .73), and social responsibility (TTURC: α = .87; CTNA: α = .86). The SIP also yields a total score (TTURC and CTNA: α = .95). Notably, the impulse control items specifically assess impulse control-related problems in the context of alcohol use: “I have taken foolish risks when I have been drinking;” “When drinking, I have done impulsive things that I regretted later;” and “I have had an accident while drinking or intoxicated.”

Family history of alcohol use disorder was a dichotomous variable (1 = present, 0 = absent). Family history was assessed in TTURC using the following question: “Has any of your blood relatives ever had what you would call a significant drinking problem? For example, have they had at least one of the following problems due to their drinking behavior: Legal problems (e.g. traffic violations, disorderly conduct, public intoxication), health problems (e.g., blackouts, DTs, cirrhosis of the liver), marital or family problems, work problems, received treatment for alcoholism (e.g., AA, Antabuse, detox), or social problems (e.g., fights, loss of friends)?” Participants in TTURC were determined as family history positive if they reported that at least one first degree relative and one second degree relative had a problem with drinking. Participants were family history negative if none of their blood relatives including parents, siblings, children, grandparents, grandchildren, uncles, aunts, nieces, nephews, or half-siblings had a problem with drinking.

The Psychiatric Family History by Interview (i.e., FHAM; Rice et al., 1995) was used in the CTNA to assess family history of AUD. Specifically, participants in CTNA were asked, “Has drinking ever caused any of your relatives to have problems with health, family, job or police?” Those who endorsed this question were asked to identify the relationship of the relative to the participant and about criteria needed to determine whether their relative met DSM-IV criteria for AUD. Participants in CTNA were determined as family history positive if they met the following 3 criteria: 1) their biological father met criteria for AUD, 2) at least one other first or second-degree biological relative met criteria for AUD, and 3) their biological mother did not meet criteria AUD. Participants in CTNA were family history negative if they had no family history of AUD in any first- or second-degree biological relatives and they were able to reliably report on at least 3 first-degree biological relatives.

Impulsivity was assessed using 3 measures: the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11; Patton, Stanford, & Barratt, 1995), the Behavioral Inhibition and Activation Scales (BIS/BAS; Carver & White, 1994), and the Brief Self-Control Scale (BSCS; Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004). A prior study (Morean et al., 2014) found psychometric evidence for brief versions of each of these measures using subsamples of data from the current study. Therefore, the brief versions of the BIS, BIS/BAS, and BSCS were used. The brief-BIS consists of 8-items and two-factors assessing poor self-regulation (e.g., “I am self-controlled” [reverse scored]; TTURC: α = .75; CTNA: α = .73) and impulsive behavior (e.g., “I do things without thinking”; TTURC: α = .73; CTNA: α = .70) on a 4-point scale (1 = rarely/never, 4 = almost always/always). The brief version of the BIS/BAS consists of 13 items and four factors: behavioral inhibition (“I worry about making mistakes.”; TTURC: α = .73; CTNA: α = .71), drive (“When I want something, I usually go all out to get it.”; TTURC α = .75; CTNA: α = .77), fun seeking (“I often act on the spur of the moment.”; TTURC: α = .70; CTNA: α = .67), and reward responsiveness (“When I’m doing well at something I love to keep at it.”; TTURC: α = .59; CTNA: α = .56) assessed on a 4-point scale (1 = not true at all for me, 4 = very true for me). The brief, 7-item BSCS consists of two factors: impulse control (“I can’t stop myself from doing something, even if I know it’s wrong.”; TTURC: α = .73; CTNA: α = .77) and self-discipline (“People would say I have iron self-discipline.”; TTURC: α = .58; CTNA: α = .64) assessed on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much).

Data Analysis

Given that we combined 2 large data sets, it was important to ensure measurement invariance of the latent constructs across data source in the combined sample. Measurement invariance for each of the impulsivity measures and alcohol problems was assessed across data source (i.e., CTNA and TTURC) in MPlus 8.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2018) using multigroup confirmatory factor analyses. First, we constrained the factor structure to equality across data source to test for configural invariance, which was established if the model fit indices were within range: CFI and TLI > .90; RMSEA < .07; and SRMR < .08 (Chen, 2007). Second, we constrained the factor loadings to equality across data source to evaluate metric invariance, which was determined if the change in model fit from the configural model did not exceed the cutoffs: RMSEA ≥ .015, CFI ≥ −.01 or SRMR ≥ .030 (Chen, 2007). Finally, we constrained the item intercepts to equality across data source to evaluate scalar invariance, which was established if change in model fit did not exceed the cutoffs: CFI ≥ −.010 in addition to change in SRMR ≥ .010 or RMSEA ≥ .015 (Chen, 2007).

Analyses of covariance for continuous variables and cumulative logistic regression analyses for ordinal variables were used to test the associations of family history of AUD and impulsivity on alcohol outcomes. The proportional odds assumption was met for both ordinal variables. These analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina) using a model building procedure. The continuous outcomes were log-transformed to normalize the distributions. We first evaluated the data using descriptive statistics (i.e., correlations, means, SDs) among the impulsivity measures (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). We then evaluated the association between each impulsivity variable independently and their interaction with family history of AUD to identify which impulsivity variables to include in the final models. Impulsivity variables that individually predicted the alcohol outcome without other impulsivity variables in the model were included in the final models. The final models also included interaction terms between each impulsivity variable and family history of AUD. Non-significant interaction terms were trimmed from the final models. These procedures were followed and modeled separately for each alcohol outcome. All models were adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnic group, years of education, and data source. The Bonferroni-Holm method (Holm, 1979) was used to control for family-wise error. Notably, multiple participants (n = 407) were excluded because they could not be categorized as family history positive or negative. Logistic regression was conducted in SAS to identify whether those excluded from the final analyses differed from those included on impulsivity variables, alcohol outcomes, and demographics. Participants excluded from the analyses were more likely to be lower on BSCS impulse control (OR: .93, 95% CI: .89, .98) and were less likely to drink 1-2 times weekly compared to daily (OR: .40, 95% CI: .20, .79). No other differences were found.

Results

Measurement Invariance

Measurement invariance was evaluated for the BIS/BAS, BIS-11, BSCS, the SIP total score, and across each of the 5-factors of the SIP by data source (TTURC vs. CTNA) to ensure the factor structure of each measure did not vary in the combined sample. Evidence of configural, metric, and scalar invariance was found for each measure (Supplemental Table 3). These findings suggest the factor structure of each measure, the magnitude of the factor loadings, and the mean responses across items on each factor were invariant by data source in the combined sample. The alphas for each factor in the combined sample were: BIS poor self-regulation α = .74, BIS impulsive behavior α = .72, BIS/BAS behavioral inhibition α = .73, BIS/BAS drive α = .76, BIS/BAS fun seeking α = .69, BIS/BAS reward responsiveness α = .58, BSCS impulse control α = .81, BSCS self-discipline α = .60, SIP physical α = .82, SIP interpersonal α = .86, SIP intrapersonal α = .86, SIP impulse control α = .74, SIP social responsibility α = .87, and SIP total α = .95. Notably, BIS/BAS fun seeking, BIS/BAS reward responsiveness, and BSCS self-discipline were dropped from subsequent analyses due to coefficient alphas under .70.

Family History of AUD and Impulsivity

The final models for the association of family history of AUD and impulsivity and their interaction terms on alcohol outcomes are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Main effects results indicated that family history of AUD was associated with physical, intrapersonal, social, and overall alcohol-related consequences. Notably, the association between family history of AUD and physical and social alcohol-related consequence did not remain significant after adjusting for multiple testing. Family history of AUD was not associated with either of the alcohol quantity and frequency measures even after the impulsivity variables were removed from the models. BIS poor-self-regulation was positively associated with alcohol quantity and frequency and nearly all alcohol-related consequences. BIS impulsive behavior was positively associated with impulse control and overall alcohol-related consequences. BSCS impulse control was associated with alcohol quantity and frequency. The analyses were also conducted for the SIP total with the impulse control subscale removed, and the findings remained the same with the exception that there was no longer a main effect of BIS impulsive behavior.

Table 2.

The association of family history of alcohol use disorder and impulsivity on alcohol outcomes

| Alcohol Frequency OR (95% CI) |

Drinks per Day OR (95% CI) |

SIP Total β (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effects | |||

| Family History Positive for AUD | 1.03 (.74-1.43) | 1.32 (.95-1.82) | .14 (.09)* |

| BIS | |||

| Poor Self-Regulation | 1.11 (1.03-1.20)* | 1.09 (1.01-1.17)* | .19 (.02)* |

| Impulsive Behavior | 1.05 (.96-1.14) | - | .14 (.02)* |

| BSCS | |||

| Impulse Control | .94 (.89-.98)* | .89 (.85-.94)* | - |

Note. Bold = p < .05.

= effect remains after adjusting for multiple tests. Each alcohol outcome was modeled separately. The table displays the results for the final models.

- indicates the effect was not included in the final model. Betas are regression coefficients from the final model for each outcome. SE = standard error of regression coefficient. BSCS = Brief Self-Control Scale. BIS = Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. SIP = Short Inventory of Problems assessing alcohol-related problems. AUD = alcohol use disorder. All models adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, and data source.

Table 3.

The association of family history of alcohol use disorder and impulsivity and their interaction on alcohol consequences

| Short Inventory of Problems (SIP) Subscales | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical β (SE) |

Interpersonal β (SE) |

Intrapersonal β (SE) |

Impulse Control β (SE) |

Social β (SE) |

|

| Main Effects | |||||

| Family History Positive for AUD | .09 (.05) | −.30 (.17) | .16 (.05)* | −.27 (.18) | .09 (.05) |

| BIS | |||||

| Poor Self-Regulation | .16 (.01)* | .05 (.01) | .19 (.01)* | .06 (.01) | .19 (.01)* |

| Impulsive Behavior | .04 (.01) | .08 (.01) | .09 (.01) | .20 (.01)* | .06 (.01) |

| Interaction Effects | |||||

| FHP*BIS Poor Self-Regulation | - | .44 (.02) | - | .40 (.02)* | - |

Note. Bold = p < .05.

= effect remains after adjusting for multiple tests. Each alcohol outcome was modeled separately. The table displays the results for the final models.

- indicates the effect was not included in the final model. Betas are regression coefficients from the final model for each outcome. SE = standard error of regression coefficient. BIS = Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. BIS/BAS = Behavioral Inhibition System/Behavioral Activation System. AUD = alcohol use disorder. All models adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, and data source.

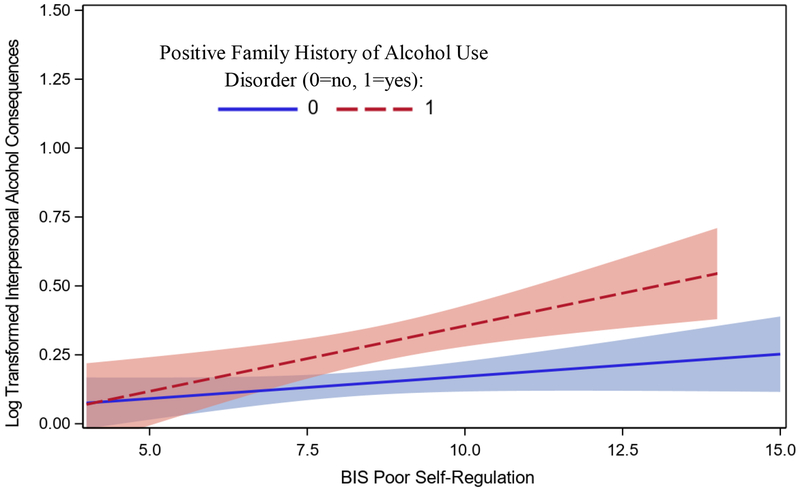

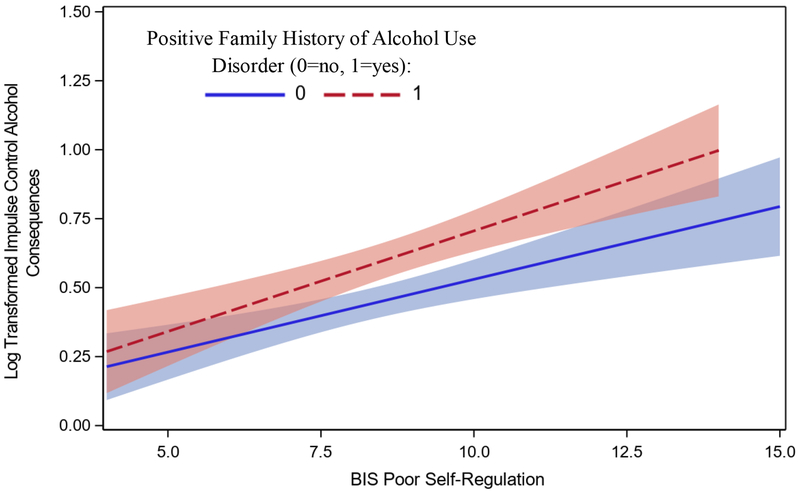

Significant interaction effects between family history of AUD and impulsivity were found for 2 SIP subscales. Specifically, a positive association was found between BIS poor self-regulation and interpersonal alcohol-related consequences among FHP individuals only (slope for FHP β = .05, SE = .01, t(300) = 3.25, p =.001; slope for FHN β = .02, SE = .01, t(343) = 1.65, p = .10) (Figure 1). However, the adjusted p = .05 for this interaction effect after taking into account multiple testing. Further, a stronger positive association was found between BIS poor self-regulation and impulse control alcohol-related consequences for FHP than FHN individuals (slope for FHP β = .08, SE = .01, t(300) = 4.96, p <.0001; slope for FHN β = .05, SE = .01, t(343) = 4.14, p <.0001) (Figure 2). Notably, in all cases but one, the interaction effect between the impulsivity variable and family history in the model building stage remained in the final model. The one exception was with drinks per day. A significant interaction was found between BIS poor self-regulation and family history when no other impulsivity variables were included in the model (χ2(1) = 4.57, p = .03). These findings indicated that BIS poor self-regulation was positively associated with drinks per day among family history positive (OR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.31) but not family history negative individuals (OR: 1.01, 95% CI: .92, 1.11). However, this interaction effect did not remain in the final model suggesting overlapping variance with BIS poor self-regulation and BSCS impulse control. No significant interaction effects were found between family history and impulsivity with the alcohol frequency outcome.

Figure 1.

Interaction between family history of alcohol use disorder and BIS poor self-regulation (range for family history positive: 4-16, range for family history negative: 4-15) on the interpersonal subscale of the SIP (positive family history for alcohol use disorder present: [slope β = .05, SE = .01, p = .001]; absent: [slope β= .02, SE = .01, p = .10])

Figure 2.

Interaction between family history of alcohol use disorder and BIS poor self-regulation (range for positive family history for alcohol use disorder = present: 4-16, absent: 4-15) on the impulse control subscale of the SIP (positive family history for alcohol use disorder present: [slope β = .07, SE = .01, p <.0001]; absent: [slope β= .05, SE = .01, p < .0001])

Discussion

The current study provides additional insight into the synergistic effects of impulsivity and family history of AUD on alcohol-related problems and quantity and frequency of alcohol use. We hypothesized 1) a positive association between impulsivity and alcohol outcomes that would be stronger in FHP individuals, and 2) that impulsivity-related traits reflecting deficits in self-control would interact with family history to increase risk for problems but impulsivity-related traits reflecting sensitivity to punishment and reward would not. Our findings provide evidence to support our first hypothesis such that there was a stronger association between impulsivity and interpersonal and impulse control alcohol-related problems among FHP compared to FHN individuals. Our second hypothesis was partially supported such that poor self-regulation was associated with more interpersonal and impulse control alcohol-related problems among FHP compared to FHN individuals. These findings suggest the compounding effects of family history and BIS impulsive behavior should be considered in developing alcohol prevention efforts. When interaction effects were not found, our findings replicated prior research indicating that impulsivity and family history of AUD were independently associated with adverse alcohol outcomes.

Given that impulsivity is a heterogenous construct (e.g., Dick et al., 2010; Sharma, Markon, & Clark, 2014), multiple measures of impulsivity were included in the current study. Based on a recent quantitative synthesis, our second hypothesis was that impulsivity-related traits reflecting deficits in self-control (BIS poor self-regulation, BIS impulsive behavior, BSCS self-control) would interact with family history to increase risk for alcohol-related problems, but this would not be the case for impulsivity-related traits reflecting sensitivity to punishment and reward (BIS/BAS drive and BIS/BAS inhibition). There were significant main effects of nearly all impulsivity measures with quantity and frequency of alcohol use and alcohol problems. One exception includes BIS/BAS inhibition and drive, which were not associated with alcohol-related problems or with quantity or frequency of alcohol use. BSCS impulse control, was associated with quantity and frequency of alcohol use but not with any of the alcohol-related consequences. In addition, BIS poor self-regulation was robustly associated with nearly all alcohol-related outcomes and was the only impulsivity measure that significantly interacted with family history to predict alcohol-related consequences, specifically, interpersonal and impulse control alcohol-related consequences. Regarding interpersonal alcohol-related consequences, those with a family history of AUD who are higher on BIS poor self-regulation are more likely to experience interpersonal alcohol-related consequences, but that for family history negative individuals, the likelihood of experiencing interpersonal alcohol-related consequences is low regardless of BIS poor self-regulation. Notably, this interaction was only marginal after accounting for multiple testing. Regarding impulse control alcohol-related consequences, individuals high on BIS poor self-regulation were more likely to experience impulse control alcohol-related problems irrespective of their family history status though the effect was stronger among those with a family history of AUD. The distinction between these two interaction effects may be due to the overlap in content between the BIS poor self-regulation and impulse control relative to interpersonal alcohol-related problems (see correlations in Supplemental Table 1). These findings only partially supported our second hypothesis. One potential explanation for why BIS poor self-regulation was a robust predictor and BIS impulsive behavior and BSCS impulse control were not is that BIS poor self-regulation seems to reflect deficits at the cognitive level related to planning (e.g., “I concentrate easily” or “I plan carefully” – both reverse scored) whereas BIS impulsive behavior (e.g., “I act on the spur of the moment”) and BSCS impulse control (“I can’t stop myself from doing something, even if I know it is wrong”) seem to reflect deficits in responding in the moment at the behavioral level. Further, the BIS poor self-regulation subscale assesses self-perception on a range of adaptive behaviors related to planning (as opposed to deficit behaviors assessed by the BIS impulsive behavior and BSCS impulse control), and these findings suggest that low levels of these adaptive behaviors have a more pervasive impact on alcohol-related outcomes. It is also possible these differences are due to a method effect given that all the BIS poor self-regulation items were positively worded and were reverse scored whereas the BIS impulsive behavior and BSCS impulse control items were negatively worded. Notably, the brief version of the BIS and the BSCS measures were not included in the recent meta-analytic review of the association of family history of AUD and impulsivity-related traits (Haeny et al., Under Review). Interventionists seeking to identify those at risk for alcohol-related problems could use the poor self-regulation subscale of the brief BIS. Further, these findings highlight the importance of research aiming to identify which specific facets of impulsivity are associated with alcohol outcomes to further narrow phenotypic risk for problem drinking.

Given that prior research suggests family history of AUD and impulsivity are independent risk factors for problem drinking (e.g., Mellentin et al., 2016; Nigg, 2017), this study sought to investigate whether having both risk factors would be more strongly associated with alcohol quantity and frequency and alcohol-related consequences, and if so, which facets of impulsivity interact with family history to increase risk for problems. Our findings suggest that having both risk factors is associated with increased alcohol-related consequences, but not increased alcohol quantity or frequency. It is also important to note that only impulsivity variables – not family history – were positively associated with the alcohol quantity and frequency in this adult sample, which is inconsistent with prior research indicating family history prospectively predicted alcohol use among adolescents (Stice et al., 1998). Other studies found family history was not associated with alcohol use when prenatal alcohol exposure was taken into account (Baer et al., 1998). The findings from the current study indicate that both family history and impulsivity may predict alcohol problems, whereas only impulsivity predicts alcohol quantity and frequency of use among adults.

The findings from this study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. Impulsivity is a heterogenous construct with many facets and measures used to assess it (e.g., Dick et al., 2010; Sharma et al., 2014). Although we included multiple facets of impulsivity, these findings may not generalize to the facets not included in this study (e.g., urgency, sensation seeking, lack of planning). In addition, all the impulsivity measures were assessed with self-report; therefore, these findings may not generalize to behavioral tasks that purport to assess impulsivity. Further, this was a cross-sectional study, so the directionality between impulsivity and alcohol use and problems cannot be determined, an important consideration given the reciprocal relation between impulsivity and alcohol consumption (Stautz and Cooper, 2013). Given that most prior work investigates the association of impulsivity and family history of AUD based on a parental family history of AUD (e.g., Haeny et al., 2018), another important limitation is that family history of maternal AUD was excluded in the CTNA and any first degree relative (parents, children, siblings) as opposed to parents only could have contributed to the family history designation in TTURC. This may explain the inconsistencies between our findings and others regarding family history and alcohol quantity and frequency of use. Further, although we found differences in the associations between family history, impulsivity-related traits, and alcohol outcomes, these findings do not inform why family history or certain impulsivity-related traits are associated with specific alcohol outcomes. The many definitions of impulsivity and measures used to assess the construct have impeded efforts to fully understand the association of impulsivity with alcohol outcomes (Dick et al., 2010; Potenza and de Wit, 2010). Findings from a recent genome-wide association study indicate differences in heritability between heavy drinking and AUD (Kranzler et al., 2019), highlighting the importance of assessing each outcome separately when seeking to understand risk for each outcome. Additionally, our findings indicate that the association of BIS impulsive behavior with overall alcohol-related problems may have been driven by the impulse control subscale; however, this was not the case for BIS poor self-regulation. Finally, these findings are based on a sample of either current drinkers or smokers, so these findings may not generalize to alcohol or tobacco naïve samples.

An important strength of this study was the large sample size which provided power to investigate the interaction between family history and impulsivity on alcohol use and problems. In addition, multiple measures of impulsivity were used which allowed to us to distinguish specifically which impulsivity measures predicted alcohol outcomes. Our inclusion of alcohol quantity and frequency measures as well as alcohol consequences also provided greater specificity in the relation between family history, impulsivity, and these outcome measures.

These findings also inform directions for future research. Research in this area could benefit from examining whether having a family history of AUD and high impulsivity in combination predict DSM-5 AUD diagnoses. Notably, multiple studies provide evidence that impulsivity mediates the relation between family history of AUD and alcohol and other drug use in offspring (Capone and Wood, 2008; Chassin et al., 2004; Ohannessian and Hesselbrock, 2007; Sher et al., 1991); however, these studies focus on broad measures of behavioral undercontrol. Researchers could investigate specifically which facets of impulsivity mediate this association using prospective data. In addition, studies should investigate whether family history of AUD and high impulsivity predict alcohol outcomes differently among those with one versus two parents with AUD. Research suggests that risk for problem drinking among those with a family history of AUD may be conferred through heritable impulsivity-related traits (e.g., Dick et al., 2010). It is possible that some impulsivity-related traits may be more heritable than others, which might explain differences in the associations between impulsivity-related traits and alcohol outcomes; however, this should be formally investigated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Supported by P50AA15632, P50DA13334, P50AA012870, and T32DA019426 from the National Institutes of Health

References

- Baer JS, Barr HM, Bookstein FL, Sampson PD, Streissguth AP, 1998. Prenatal alcohol exposure and family history of alcoholism in the etiology of adolescent alcohol problems. J. Stud. Alcohol 59, 533–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg JM, Latzman RD, Bliwise NG, Lilienfeld SO, 2015. Parsing the Heterogeneity of Impulsivity: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Behavioral Implications of the UPPS for Psychopathology. Psychol. Assess 27, 1129–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone C, Wood MD, 2008. Density of Familial Alcoholism and Its Effects on Alcohol Use and Problems in College Students. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 32, 1451–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver Charles S., White TL, 1994. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 67, 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Flora DB, King KM, 2004. Trajectories of Alcohol and Drug Use and Dependence From Adolescence to Adulthood: The Effects of Familial Alcoholism and Personality. J. Abnorm. Psychol 113, 483–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen FF, 2007. Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indexes to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar]

- Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Cyders MA, 2013. Multidimensionality in Impulsivity and Alcohol Use: A Meta-Analysis Using the UPPS Model of Impulsivity. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 37, 1441–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton NS, 1979. The Familial Incidence of Alcoholism A Review. J. ol Stud. Alcohol 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio AL, George AM, 2011. Selected impulsivity facets with alcohol use/problems: The mediating role of drinking motives. Addict. Behav 36, 959–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Smith G, Olausson P, Mitchell SH, Leeman RF, O’Malley SS, Sher K, 2010. Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addict. Biol 15, 217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigsby TJ, Forster M, Unger JB, Sussman S, 2016. Predictors of alcohol-related negative consequences in adolescents: A systematic review of the literature and implications for future research. J. Adolesc 48, 18–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeny AM, Littlefield AK, Wood PK, Sher KJ, 2018. Method effects of the relation between family history of alcoholism and parent reports of offspring impulsive behavior. Addict. Behav 87, 251–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman AM, Duka T, 2018. Facets of impulsivity and alcohol use: What role do emotions play? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Schalet BD, Malone SM, Iacono WG, McGue M, 2011. Psychometric and genetic architecture of substance use disorder and behavioral disinhibition measures for gene association studies. Behav. Genet 41, 459–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm S, 1979. A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scand. J. Stat 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Khemiri L, Kuja-Halkola R, Larsson H, Jayaram-Lindström N, 2019. Genetic overlap between impulsivity and alcohol dependence: a large-scale national twin study. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Knop J, Teasdale TW, Schulsinger F, Goodwin DW, 1985. A prospective study of young men at high risk for alcoholism: school behavior and achievement. J. Stud. Alcohol 46, 273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles EE, Schroeder DA, 1989. Familial and personality correlates of alcohol-related problems. Addict. Behav 14, 537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Zhou H, Kember RL, Vickers Smith R, Justice AC, Damrauer S, Tsao PS, Klarin D, Baras A, Reid J, Overton J, Rader DJ, Cheng Z, Tate JP, Becker WC, Concato J, Xu K, Polimanti R, Zhao H, Gelernter J, 2019. Genome-wide association study of alcohol consumption and use disorder in 274,424 individuals from multiple populations. Nat. Commun 10, 1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M, 2002. Etiologic Connections among Substance Dependence, Antisocial Behavior, and Personality: Modeling and Externalizing Spectrum. J. Abnorm. Psychol 11, 411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ksinan AJ, Su J, Aliev F, Dick DM, Pedersen K, Neale Z, Thomas N, Adkins AE, Bannard T, Cho SB, Barr P, Berenz EC, Caraway E, Clifford JS, Cooke M, Do E, Edwards AC, Goyal N, Hack LM, Halberstadt LJ, Hawn S, Kuo S, Lasko E, Lend J, Lind M, Long E, Martelli A, Meyers JL, Mitchell K, Moore A, Moscati A, Nasim A, Opalesky J, Overstreet C, Christian Pais A, Raldiris T, Salvatore J, Savage J, Smith R, Sosnowski D, Walker C, Walsh M, Willoughby T, Woodroof M, Yan J, Sun C, Wormley B, Riley B, Peterson R, Webb BT, 2019. Unpacking Genetic Risk Pathways for College Student Alcohol Consumption: The Mediating Role of Impulsivity. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 43, 2100–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson L, Magidson JF, Reynolds EK, Kahler CW, Lejuez CW, 2010. Changes in Sensation Seeking and Risk-Taking Propensity Predict Increases in Alcohol Use Among Early Adolescents. Alcohol. Clin. Res 34, 1400–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann LM, Chassin L, Sher KJ, 1987. Alcohol expectancies and the risk for alcoholism. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 55, 411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellentin AI, Brink M, Andersen L, Erlangsen A, Stenager E, Bjerregaard LB, Christiansen E, 2016. The risk of offspring developing substance use disorders when exposed to one versus two parent(s) with alcohol use disorder: A nationwide, register-based cohort study. J. Psychiatr. Res 80, 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, & Longabaugh R, 1995. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse (Vol. 4). National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, DeMartini KS, Leeman RF, Pearlson GD, Anticevic A, Krishnan-Sarin S, Krystal JH, O’Malley SS, 2014. Psychometrically improved, abbreviated versions of three classic measures of impulsivity and self-control. Psychol. Assess 26, 1003–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2003. Recommended alcohol questions.

- Nigg JT, 2016. Annual Research Review: On the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58, 361–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Hesselbrock VM, 2007. Do personality characteristics and risk taking mediate the relationship between paternal substance dependence and adolescent substance use? Addict. Behav 32, 1852–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES, 1995. Factor Structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J. Clin. Psychol 51, 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrakis IL, 2017. The Importance of Identifying Characteristics Underlying the Vulnerability to Develop Alcohol Use Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 174, 1034–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza MN, de Wit H, 2010. Control Yourself: Alcohol and Impulsivity. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 34, 1303–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders GR, Schuckit MA, 1981. MMPI scores in young men with alcoholic relatives and controls. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 169, 456–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma L, Markon KE, Clark LA, 2014. Toward a theory of distinct types of “impulsive” behaviors: A meta-analysis of self-report and behavioral measures. Psychol. Bull 140, 374–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher K, 1991. Children of alcoholics: A critical appraisal of theory and research. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Wood PK, Edward B, 1991. Characteristics of Children of Alcoholics: Putative Risk Factors, Substance Use and Abuse, and Psychopathology Academic Integrity and Boundary-Stretching-Behaviors in Writing and Revising with Feedback View project Elevated rate of alcohol consumption in. Artic. J. Abnorm. Psychol 100, 427–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS, Heath AC, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Statham DJ, Martin NG, 2002. Personality and the genetic risk for alcohol dependence. J. Abnorm. Psychol 111, 124–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen HJ, Manzardo AM, Knop J, Penick EC, Madarasz W, Nickel EJ, Becker U, Mortensen EL, 2011. The Contribution of Parental Alcohol Use Disorders and Other Psychiatric Illness to the Risk of Alcohol Use Disorders in the Offspring. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 35, 1315–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stautz K, Cooper A, 2013. Impulsivity-related personality traits and adolescent alcohol use: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev 33, 574–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Barrera M, Chassin L, 1998. Prospective differential prediction of adolescent alcohol use and problem use: Examining the mechanisms of effect. J. Abnorm. Psychol 107, 616–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AL, Becker LG, Huber AM, Catalano RF, 2012. Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addict. Behav 37, 747–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL, 2004. High Self-Control Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology, Better Grades, and Interpersonal Success. J. Pers 72, 271–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Hegedus AM, Gavaler JS, 1985. Hyperactivity in sons of alcoholics. J. Stud. Alcohol 46, 259–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Windle RC, Scheidt DM, & Miller GB, 1995. Physical and sexual abuse and associated mental disorders among alcoholic inpatients. Am. J. Psychiatry 152, 1322–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon G, Westermeyer J, Kuskowski MA, Nesheim L, 2013. Impact of the number of parents with alcohol use disorder on alcohol use disorder in offspring: a population-based study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 74, 795–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.