Abstract

This ex-post facto study reanalyzed data from Romski et al. (2010) to examine whether intervention focus moderated the relationship between pre-intervention standardized measures of receptive language and post-intervention standardized measures of receptive and expressive language age and observations of expressive target vocabulary size. In all, 62 toddlers with developmental delay were randomly assigned to augmented communication-input (AC-I), augmented communication-output (AC-O), or spoken communication (SC) interventions. AC-I provided augmented language input via spoken language and a speech-generating device (SGD); AC-O encouraged the production of augmented output via an SGD; and SC provided spoken input and encouraged spoken output without using an SGD. Intervention focus moderated the impact of initial receptive language on expressive language age and expressive target vocabulary size. Participants in AC-I, when compared to those in the other two interventions, had a significantly stronger relationship between initial receptive language and post-intervention expressive language age. For expressive target vocabulary size, participants in AC-O showed a strong relationship and those in AC-I a slightly weaker relationship between initial receptive language and expressive target vocabulary size; no significant relationship was found in the SC group. Results emphasize that different interventions may have distinct outcomes for children with higher or lower initial receptive language.

Keywords: Augmentative and alternative communication intervention, Augmented input, Comprehension, Expressive language, Receptive language

Toddlers’ growth in receptive language is largely supported by communication partners, including parents and other caregivers, who model the use of spoken language in everyday contexts. Via repeated exposures to spoken symbols in predictable, familiar settings, children learn relationships that they ultimately begin to express with speech. Consequently, receptive language serves as an important foundation for the development of expressive language (Bates, 1979; Benedict, 1979; Goldin-Meadow, Seligman, & Gelman, 1976; Sevcik, 2006; Trudeau, Sutton, & Morford, 2014). Although the development of comprehension and production of symbols is complex, it is generally the case that through the comprehension of symbols, regardless of modality, that children begin to participate in meaningful communication exchanges during which they fully assume the roles of listener and speaker. Decades of research demonstrate this developmental sequence (Benedict, 1979; Fenson et al., 1994; Goldin-Meadow et al., 1976). By the time they are 16-months old, parents report that their children with typical development often understand about 170 words but produce only about 40 words (Fenson et al., 1994). Other studies report more conservative numbers, with slightly younger children understanding approximately 50 but producing only 10 words (Benedict, 1979). At about 20 months of age children can usually produce the same number of words that they understood at 12 to 16 months of age (Benedict, 1979; Fenson et al., 1994; Goldin-Meadow et al., 1976). This gap between comprehension and production persists into the preschool years (Trudeau et al., 2014).

Children with developmental delays demonstrate the same important relationships between receptive language (i.e., the understanding of others’ symbol use, regardless of modality) and expressive language (i.e., producing symbols to share with others). Chapman, Seung, Schwartz, and Kay-Raining Bird (2000), in a sample of children with Down syndrome, found that language comprehension scores accounted for large proportions of variance in number of different words produced (60%) and mean length of utterance (71%) in a structured language sample. In a sample of 45 preschool children with significant language delay, Brady, Steeples, and Fleming (2005) reported strong positive correlations between receptive language, expressive language, and cognitive ability. In addition, they reported that receptive language accounted for 7.6% of variance in comment initiations and 6.9% of variance in request initiations above and beyond the role of cognitive ability, both representing small to medium effect sizes.

Evidence suggests that receptive language also is important for children who learn language via augmented means. Romski and Sevcik (1996) reported that comprehension was important in determining success with the System for Augmenting Language (SAL), an augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) language intervention strategy. SAL users were 13 males (approximately 6- to 20-years-old) with significant developmental disabilities and limited functional speech who used SAL over a two-year period. Participants demonstrated two distinct patterns of symbol learning. The advanced achievement profile was characterized by the acquisition of a large expressive symbol vocabulary of 100 symbols or more in comprehension and production. The beginning achievement profile was characterized by the acquisition of a small symbol vocabulary of 20 to 35 symbols. Initial receptive vocabulary knowledge differentiated the groups; participants who exhibited the advanced achievement profile exhibited speech comprehension skills of 24 months or higher while participants who exhibited the beginning achievement profile were unable to achieve a basal score on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (PPVT-R; Dunn & Dunn, 1981). More recently, in a study of 10 children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder who were 6- to 10-years-old and had very limited expressive vocabularies, Brady et al. (2015) documented that those who exhibited the highest expressive gains in a multi-modal intervention also had higher initial receptive vocabulary scores relative to children who showed little to no gains. Taken together, these studies provide strong evidence that, even when expressive language skills are very low, children with relatively better language comprehension can use that understanding to bootstrap into expression. They do not, however, provide insight into how the focus of the intervention may impact that relationship.

Just like children with typical development, who learn to comprehend language through caregiver modeling of speech, children learning language via AAC—both receptive and, later, expressive—do so via models of augmented language (Romski & Sevcik, 2003). This modeling of augmented language, or augmented input, consists of all of the communication and/or language that an individual experiences from his or her communicative partners, including natural speech, speech that is supplemented by AAC symbols, the synthetic or digitized speech that is generated by the speech generating device (SGD) when the symbol is activated, and the environmental context itself (Romski & Sevcik, 2003; Sevcik & Romski, 2002). Like spoken language for typically developing children, augmented input supports the development of receptive language skills for children with delay who are beginning to learn language, often referred to as beginning communicators, by providing models of AAC usage, illustrating the SGD’s usefulness, and demonstrating that the SGD is an acceptable vehicle for communication (Romski, Sevcik, Cheslock, & Barton-Hulsey, 2017). Furthermore, augmented input illustrates the real-world meaning of symbols, the many functions they can serve, and demonstrates that the AAC system is both accepted and encouraged as a modality for communication (Romski & Sevcik, 2003; Romski et al., 2017; Sevcik & Romski, 2002).

Different AAC intervention strategies use systematic variations of augmented input that include natural, synthetic, or digitized speech and visual-graphic symbols to support language development. In aided language stimulation (Goossens’, 1989; Harris & Reichle, 2004), which uses a highly structured protocol, and aided language modeling (Drager et al., 2006), which is less structured, the partner (e.g., parent or clinician) points to AAC symbols while simultaneously using natural speech; an SGD with digitized or synthetized speech is not used. Aided AAC modeling is similar but includes symbol combinations (Binger & Light, 2007; Binger, Maguire-Marshall, & Kent-Walsh, 2011). The augmented input described by Romski and Sevcik (Romski & Sevcik, 1996; Romski et al., 2010; Sevcik, 2006) incorporates the use of an SGD with digitized or synthetic output, in conjunction with natural speech input.

These augmented input approaches to intervention have successfully improved both comprehension and production across spoken and augmented modalities for individuals who use AAC and do not speak. A small number of studies with very small samples have shown vocabulary gains for preschool children (Harris & Reichle, 2004) and older children (8 to 12 years; Dada & Alant, 2009) with intellectual disability, and preschool (Drager et al., 2006) and kindergarten children with autism spectrum disorder (Brady, 2000). Others have shown improvements in multi-symbol messages in preschoolers with developmental delay (Binger & Light, 2007). One large correlational study with 71 preschool children with significant developmental delay reported significant gains in expressive and receptive language scores for children who received augmented input from their peers (Barker et al., 2013).

More recently, researchers have evaluated the impact of augmented input in a series of systematic reviews (Allen, Schlosser, Brock, & Shane, 2017; Biggs, Carter, & Gilson, 2018; Sennott, Light, & McNaughton, 2016). Sennott et al. (2016) concluded that AAC modeling intervention approaches result in improvement, both expressively and receptively, across several linguistic domains, including pragmatics, semantics, syntax, and morphology. Allen et al. (2017) further concluded that augmented input supports learning of vocabulary skills at the single-word level (both expressive and receptive), and expression of multi-symbol utterances. Finally, Biggs et al. (2018) evaluated the impact of different intervention packages, including those with components that were not focused exclusively on augmented input. They concluded that these intervention packages improved expressive pragmatics, semantics, and morphosyntax.

In one of the largest intervention studies to date, and the study from which the data in this report originated, Romski et al. (2010) compared the effects of three different parent-implemented early language interventions on the communication development of 62 toddlers who had significant developmental disabilities. Each parent–child dyad took part in a 24-session language intervention and was randomly assigned to one of three conditions that varied the focus of the communication partners’ instructional strategies: spoken communication (SC) (n = 21), which focused on either spoken interaction or one of two augmented language interventions: augmented communication-input (AC-I) (n = 21) or augmented communication-output (AC-O) (n = 20). Each intervention had four components: target vocabulary, parent coaching, mode, and strategies.

In the SC intervention, which served as the contrast condition, the parent/interventionist provided only spoken models of target vocabulary and prompted the participant, both visually and verbally, to speak those words (e.g., Tell me with your mouth, while pointing to his or her mouth). Children were not provided an SGD in the SC intervention. In the AC-I intervention, the parent/interventionist provided both spoken and augmented input of the target vocabulary via an SGD. The participant was not required to produce the target vocabulary with speech or the SGD. The participants were provided with natural reinforcers (e.g., verbal praise) when they produced target vocabulary in any mode. In the AC-O intervention, the parent/interventionist provided only spoken input of the target vocabulary and no augmented input via the SGD. Instead, if the child did not produce the target vocabulary via the SGD, he or she was visually, verbally, and/or physically encouraged to produce the target vocabulary item (e.g., Tell me what you want, while pointing to the device). A summary of the similarities and differences between the interventions is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Components of the Three Interventions (adapted from Romski et al., 2010)

| Component | AC-I: Augmented communication input | AC-O: Augmented communication output | SC: Spoken communication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target vocabulary | Individualized target vocabulary of visual-graphic symbols+spoken words with use of all target vocabulary during each session; interventionist/parent (I/P) has a card with all target vocabulary listed. | Individualized target vocabulary of visual-graphic symbols+spoken words with use of all target vocabulary during each session; I/P had card with all target vocabulary listed | Individualized target vocabulary of spoken words with use of all target vocabulary during each session; I/P had card with all target vocabulary listed |

| Mode | I/P uses speech-generation device (SGD) to provide communication input to child | Child uses SGD to communicate | I/P and child use speech to communicate |

| Strategies | I/P provides vocabulary models to child using the device; symbols are positioned in the environment to mark referents; I/P reinforces the child’s productive communications | I/P provides verbal and/or hand over hand prompts so that the child produces communication using the SGD | I/P provides verbal prompts so that the child produces spoken words |

| Parent coaching | I provides coaching for P | I provides coaching for P | I provides coaching for P |

| Sample interaction | Adult (A) and child (C; Emily) are having snack | Adult (A) and child (C; Johnny) are playing with blocks | Adult (A) and child (C; Lem) are playing |

| A: Mmm | A: Look Johnny | A: Let’s play with the truck | |

| A: Now what do you want? | A: Here are the blocks | A: Look (A points to mouth) | |

| A: “Cookie” or “Cracker” | A: Tell mama build | A: Look | |

| C: vocalizes unintelligibly and holds out hand | C: “Play” | A: /t/ /t/ | |

| A: Cookie or cracker? | A: Yep, we’re playin’ | C: unintelligible vocalization | |

| C: Cracker” | A: Tell mama build (A taps on SGD) | A: Truck | |

| A: Good. You want a cracker | A: Tell me build | C: unintelligible vocalization | |

| A: Ok. (A gives the cracker to Emily) | C: “Build” (A provides hand over hand assistance) | A: Right? | |

| A: That tastes good | A: Alright | A: Look at my face |

Note. Adapted from “Randomized Comparison of Augmented and Non-Augmented Language Interventions for Toddlers with Developmental Delays and their Parents, ” by M. A. Romski, R. A. Sevcik, L. B. Adamson, M. Cheslock, A. Smith, R. M. Barker, and R. Bakeman, 2010, Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53, p. 355. Copyright 2010 by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Reprinted with permission.

Before the intervention, none of the children were able to comprehend or produce the target vocabulary, according to parent report and probes conducted by a speech-language pathologist (SLP); and neither of the three groups differed on mean levels of receptive and expressive language, as evaluated by standardized assessments. After intervention, the participants in the two augmented interventions used significantly more expressive target vocabulary words in the combined spoken and augmented modalities compared to those in the SC intervention. In addition, those in the AC-O intervention used significantly more expressive target vocabulary words than those in the AC-I intervention.

Given that Romski et al. (2010) found that intervention focus affected the size of a child’s expressive target vocabulary at the end of intervention, it is important to investigate further whether individual differences in initial receptive language might be related to differential success. In particular, investigating whether initial receptive language and intervention focus may interact to influence intervention outcomes will illuminate whether certain interventions are more appropriate for children with different levels of initial receptive language.

It is clear that initial receptive language is predictive of language outcomes and that augmented input approaches can help to support the development of both comprehension and production in multiple modalities. To date, however, no studies have investigated the extent to which a child’s initial receptive language may interact with the focus of an intervention to influence language outcomes.

Therefore, using data from the Romski et al. (2010) longitudinal study, the current study looks specifically at the relationship between initial receptive language, as measured by standardized assessment, and target language outcomes and investigates whether intervention focus moderates this relationship. In other words, does the relationship between initial receptive language and language outcomes differ depending upon the type of language intervention to which children were randomly assigned? To this end, does intervention focus moderate the relationship between initial receptive language and language outcomes? It was hypothesized that there would be strong positive associations between initial receptive language and language outcomes, prior to taking intervention focus into account (i.e., a main effect). More importantly, it was also hypothesized that these associations would be moderated by the focus of the intervention. Specifically, it was predicted that there would be stronger associations between initial receptive language and measures of language production for children who received the AC-I intervention, compared to the other two language interventions. For children with higher initial receptive language, the input-focused AC-I intervention would support the transition to production because they will learn to comprehend the targets of intervention more easily and then begin to produce the targets. Children with lower initial receptive language will also learn to comprehend but will not show evidence of production of targets. Thus, children with lower initial receptive language will evidence little learning of the target words. I t was expected that the association between initial receptive language and language outcomes would not be as strong for the other intervention conditions, as AC-O and SC did not provide augmented language input.

Method

Participants

Data from the 62 toddlers who completed the intervention study by Romski et al. (2010) were analyzed in this paper. Original participant selection criteria were (a) children between 24 and 36 months of age with a significant developmental delay, a significant risk for speech and language impairment, which was operationally defined as not having begun to talk, as indicated by a vocabulary of at most 10 intelligible spoken words and a score of less than 12 months on the expressive language scale of the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL; Mullen, 1995); (b) at least primitive intentional communication abilities (i.e., they could physically manipulate the environment to get what they want; per observation during the MSEL); (c) upper extremity gross motor skills that permitted the child to touch the symbols on the SGD (per observation during the MSEL); (d) a primary disability other than delayed speech and language impairment, deafness/hearing impairment, or autism spectrum disorder (per parent report); and (e) English as the primary language spoken at home (per parent report). Receptive language prior to intervention was not a selection criterion. Parents received information about the study from a recruitment source and individually contacted the project to participate. Parents provided informed consent for their child to participate after meeting with the project SLP and principal investigator, who explained the study. All aspects of this study were approved by the IRB at Georgia State University.

Medical etiology of participants included genetic syndromes (e.g., Down syndrome), seizure disorder, cerebral palsy, or unknown medical etiology. As reported by Romski et al. (2010), of the 62 participants (43 boys; 19 girls; Mca 29.6 months, range: 21–40 months) who began the intervention, 91% completed the intervention. The sample included 18 African American, seven Asian, and 37 Caucasian children. All had hearing and vision within normal limits as described by intake reports. Because this was a supplemental intervention, many participants received other early intervention services. At the onset of the study, 74% were enrolled in state-funded early intervention services, and 87% were receiving individual speech therapy services.

Overall, as reported by Romski et al. (2010), the parents of the participants (58 mothers, four fathers) had high levels of education: six had completed Grade 12 or received a general equivalency diploma, eight had some college, 25 had graduated from college, 21 had a least some postgraduate education, and two did not report their education. Importantly, the parents who agreed to take part in the study committed to participate in all of the assessment and intervention sessions, and were required to travel to the laboratory or have study staff in their home approximately twice per week for at least 12 weeks. As such, the families were assumed to be of at least middle socioeconomic status.

Procedure

Pre- and post-intervention standard assessments.

Each child and his or her parent participated in pre-intervention assessments and were then randomly assigned to one of the three parent-implemented interventions. During the pre-intervention phase of the study, the project’s SLP, who was certified by the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association (ASHA), conducted an assessment battery that included descriptive, cognitive, and language/communication measures. The SLP was blinded to the child’s intervention assignment until after the assessments were completed.

Parents received a written report of the child’s performance on the research measures after the assessment. Pre- and post-intervention receptive language age, as well as post-intervention expressive language age, were measured using the Sequenced Inventory of Communication Development (SICD; Hedrick, Prather, & Tobin, 1984). Because the SICD produces estimates of a child’s expressive and receptive language ages in months, as opposed to raw scores, we used language age to indicate participants’ initial receptive language and post-intervention receptive and expressive language ages as dependent variables. One participant was missing data for post-intervention receptive and expressive language ages and was excluded from the analyses that use these outcomes. Thus, the numbers reported in Romski et al. (2010) differ slightly from the figures reported here.

Interventions.

As described in Romski et al. (2010), parent–child dyads were randomly assigned to one of three interventions: Augmented Communication Input (AC-I), Augmented Communication Output (AC-O), or Spoken Communication (SC). The primary distinction between the three interventions was a focus on providing augmented input (AC-I), a focus on producing vocabulary with an SGD (AC-O), or providing speech only input (SC). Table 1 compares target vocabulary, parent coaching, mode, and strategies across the three interventions. All three interventions were naturalistic and parent coaching included instructions to use language modeling, expansions, and opportunities for resolving communication breakdowns to encourage interaction and communication, as well as reminders to parents to use short utterances, to give the participant a choice between two items, and to pause to ensure the participant had a chance to communicate. Moreover, across the three interventions, the interventionist or parent reinforced any target vocabulary use by responding naturally. For example, if a participant used the target vocabulary word “more” (in any modality), then the interventionist or parent could respond by saying, Oh, you want more! and providing more of whatever the participant requested. A unifying aspect of the three interventions is that the interventionist provided coaching and feedback to parents and answered any questions they may have had about the sessions. The study SLP, who had 13 years of early intervention clinical experience, supervised six female interventionists (M = 25.6 years). They had at least a bachelor’s degree in psychology or communication and were taught to deliver all three interventions. Due to the nature of the study, they could not be blinded to the intervention assignment of the participants; however, they were blinded to the research questions. No less than 30% of the intervention sessions were supervised as per guidelines for supervision of SLP assistants (ASHA, 2004). Instruction was provided to all parents using the same manual (within each intervention) and for the same number of sessions. All intervention sessions were videotaped for later transcription, coding, and evaluation of treatment fidelity.

Romski et al. (2010) evaluated treatment fidelity using the Treatment Implementation Rating Scale (TIRS; Romski, Sevcik, Adamson, Cheslock, & Smith, 2007) using procedures that align with the suggestions of Schlosser (2002) and Kent-Walsh and Binger (2018). The TIRS consists of 13 items that evaluates components common to the interventions, components specific to the interventions, and an intervention-specific scoring key. Seven trained independent observers rated 21% of each participant’s sessions (310 total sessions), distributed across all 24 sessions. Results indicated high treatment fidelity for intervention implementation across both session types (with mean scores for interventionist only = .94, parent-supported = .94, and parent-led = .91) and intervention (Ms = .93 for AC-I, AC-O, and SC). Moreover, reliability of the implementation of the TIRS was evaluated by having an additional trained rater score 20% (62) of the 310 sessions (Cohen’s kappa = .83).

In all three interventions, the goal was to teach parents effective ways to communicate with their child and to give the child a way to communicate. Each dyad completed 24 30-min intervention sessions. The first 18 sessions took place at the Toddler Language Intervention Lab at Georgia State University. The final six sessions took place at the child’s home. This transition was done to determine generalization outside of the clinical setting. The median number of weeks required for each dyad to complete the intervention was 16 for AC-I, 16 for AC-O, and 15 for SC. Each 30-min intervention session consisted of three 10-min segments focused on play, book reading, and snack, in that order. An individualized set of target vocabulary appropriate to the three activities was chosen for each child through collaboration between the parent and the project’s SLP. Per intervention protocol, parents provided input, either speech or augmented, depending on the intervention, on these target vocabulary items. As reported in Romski et al. (2010) by design, parents in the AC-I intervention provided significantly more augmented input than the parents in the other interventions; these same parents also provided significantly less speech-only input. The total amount of input did not differ between groups, F(2,59) = 2.56, p = .09.

Expressive target vocabulary size.

Expressive target vocabulary size at the end of the intervention also was used as an outcome measure for the current study. As mentioned previously, each child had an individually chosen set of target vocabulary items that the child’s parent and the project’s SLP chose to be motivating for the child during the three 10-min intervention routines (i.e., play, book reading, snack) and that were appropriate for use at home during similar routines. At the pre-intervention assessment session, the child did not comprehend or produce these vocabulary items in speech or sign, per parent report and confirmed by probes from the project’s SLP. For example, target vocabulary items may have included the following words: blocks, play, car, book, open, truck, spoon, yogurt, cookie, juice, my turn, more, all done, and what’s this? Target words were represented as spoken words in the SC condition or augmented words in the augmented conditions. For the AC-I and AC-O interventions, target vocabulary augmented words were represented on the SGD using Picture Communication Symbols (PCS; Mayer-Johnson Co., 1981). To ensure that participants in all interventions were given experience with each of the targeted vocabulary items, interventionists and parents were encouraged to use all target vocabulary words in every session. To do so, they used a list of the child’s targeted vocabulary on an index card during each session to keep track of the vocabulary items and which had been used. All participants began the study with 15 target vocabulary words. Over the course of the intervention, additions were made when a participant began to use a majority of his or her available target vocabulary, as determined by the study SLP, interventionist, and parent. Romski et al. (2010) reported that by the end of the study, participants had, on average, 22 target vocabulary words in AC-I, 23 in AC-O, and 16 in SC that were available and targeted for instruction in the intervention (this was not the number of words the child learned but rather the number that was targeted).

The measure of expressive target vocabulary size used in this study was derived from a reliable set of transcripts of the final intervention session (i.e., session 24), which was led by the parent. One participant completed 23 of the 24 intervention sessions; this participant’s expressive target vocabulary size was used at the 23rd session in our data analyses. In the original study, nine transcribers, naive to the goals of the study, were trained to produce transcripts with a study-specific transcription and coding manual (Romski & Cheslock, 2004) and Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT; Miller & Chapman, 1985) conventions. Before transcribing actual intervention sessions, transcribers were trained on a set of training videos until they reached 90% agreement with a predetermined standard. Reliability of transcripts was ensured using a three-step process. A second trained transcriber reviewed every transcript while watching corresponding videotaped interactions and made corrections or changes per SALT conventions and the transcription and coding manual. A third trained transcriber then checked for accuracy all of codes related to target vocabulary use while watching the videotaped interaction and made corrections as necessary. Finally, a fourth trained transcriber conducted a final review of the transcript to ensure maximum accuracy.

Each spontaneous and different participant usage of target vocabulary was coded for modality (i.e., SGD, spoken, or both). Hand-over-hand activations of the SGD by the parent were not considered spontaneous and so were not included in the expressive target vocabulary variable. Thus, the expressive target vocabulary dependent variable consisted of the participant’s independent use of target vocabulary during the final intervention session, in speech, symbol, or speech + symbol.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the variables used in this report are given in Table 2. There were no differences between the intervention groups for initial SICD receptive language age or post-intervention SICD receptive or expressive language age. As reported in Romski et al. (2010), only post-intervention target vocabulary size differed by intervention focus. The mean number of target vocabulary used, by modality, in AC-I was 10.0 (8.8, 0.6, and 0.6 for augmented only, spoken only, and combined modalities, respectively), in AC-O it was 15.4 (12.5, 0.5, and 2.4 for augmented only, spoken only, and combined modalities, respectively), and in SC it was 0.76 (spoken only).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics by Intervention Focus

| M | SD | Statistics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC-I | AC-O | SC | AC-I | AC-O | SC | η2 | p | |

| Initial SICD receptive language | 18.1 | 20.0 | 18.6 | 7.00 | 6.22 | 7.72 | .014 | .678 |

| Post-intervention SICD receptive language | 21.7 | 22.0 | 22.0 | 7.96 | 7.28 | 10.43 | .000 | .99 |

| Post-intervention SICD expressive language | 15.4 | 16.2 | 16.8 | 7.51 | 6.12 | 6.72 | .007 | .81 |

| Post-intervention target vocabulary size | 10.0 | 15.4 | 0.76 | 7.52 | 10.42 | 1.64 | .410 | <.001 |

Note. SICD = Sequenced Inventory of Communication Development; AC-I = augmented communication-input (n = 21); AC-O = augmented communication-output (n = 20); SC = spoken communication (n = 21) except 20 for posttest receptive and expressive language age).

Analyses of variance to test whether intervention focus moderated the association between initial receptive language, as measured by the SICD, and the three other variables (the outcomes) are presented in Table 2. Pretest receptive language age was entered first, then intervention focus, and then their interaction (i.e., Type I sums of squares was specified). Results are given in Table 3. The conventional p-values given in Table 3 are estimates based on assumptions about the data, an approach that arose in the pre-computer age that has become conventional. Arguably, a better estimate is obtained by bootstrapping methods based on the actual data and that do not require these assumptions. Bootstrapping is a statistical technique where k samples of n size are drawn randomly, with replacement, from the collected data (DiCiccio & Efron, 1996). These bootstrapped samples are used to create a confidence interval around the estimates derived from the sample data. For the present analysis, k = 1000 bootstrapped samples of n = 62 were estimated. The significance tests we report indicate a significant difference in 950 of the 1000 bootstrapped samples we created. This approach compensates for the reduced power associated with small sample sizes and non-normal distributions (DiCiccio & Efron, 1996). For the current study, this method indicated a conventional level of significance (p < .05) for the moderation effect for expressive language age, whereas the conventional analysis showed statistical significance that approached but did not reach the conventional .05.

Table 3.

Analyses of Variance Statistics Testing Moderation

| Outcome variable and analysis of variable effect | df | F | pη2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptive language age | ||||

| Pretest receptive language age | 1,55 | 166.1 | .75 | <.001 |

| Intervention focus | 2,55 | 0.85 | .030 | .43 |

| Interaction | 2,55 | 0.59 | .021 | .56 |

| Expressive language age | ||||

| Pretest receptive language age | 1,55 | 13.82 | .20 | <.001 |

| Intervention focus | 2,55 | 0.24 | .008 | .79 |

| Interaction* | 2,55 | 2.68 | .089 | .078 |

| Expressive target vocabulary size | ||||

| Pretest receptive language age | 1,56 | 18.6 | .25 | <.001 |

| Intervention focus | 2,56 | 26.0 | .48 | <.001 |

| Interaction* | 2,56 | 5.01 | .15 | .010 |

Effects were significant according to bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals.

Cohen (1988) suggested that a pη2 of .02, .13, and .26 indicates a small, medium, and large effect, respectively. Thus, for all three outcome variables, the effect of pretest receptive language age was strong (see Table 3). The effect of intervention focus was small and statistically insignificant for the receptive language age outcome, essentially nonexistent for the expressive language age outcome, and strong for the expressive target vocabulary size outcome. But the effect of the interaction was central to our hypotheses: For receptive language age following intervention, it was small and statistically insignificant. For expressive language age following intervention, it was small to medium and statistically significant with bootstrapped methods and thus warranted interpretation. And for expressive target vocabulary size following intervention, it was medium and statistically significant by both conventional and bootstrapped methods.

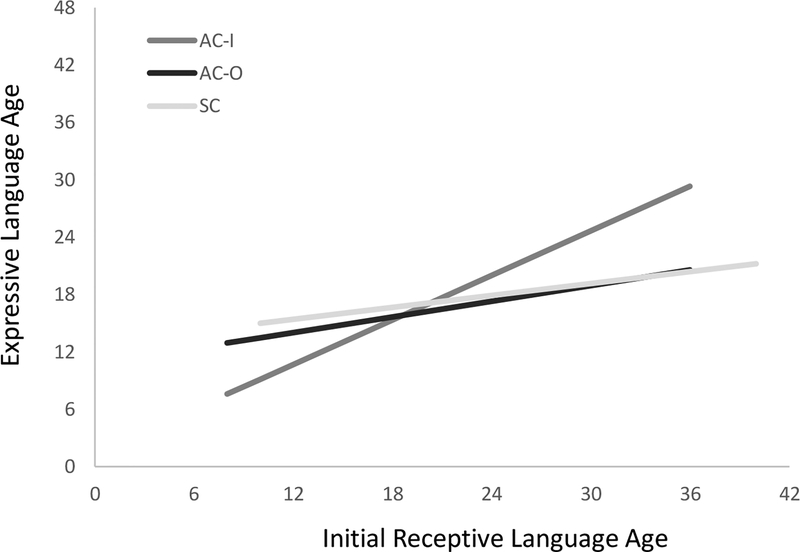

Explication of these effects is portrayed graphically in Figures 1–3, which show the regression models separately for each outcome and intervention focus. For receptive language age following intervention, the regression lines are essentially parallel indicating little interaction, at similar levels indicating little effect of focus, but with an upward slope indicating the strong effect of pretest receptive language. For expressive language age following intervention, the non-parallel lines indicate interaction—in AC-I, the association between initial receptive language and expressive language was stronger than in either AC-O or SC, where the relationships were essentially similar. Their similar levels indicate little effect of focus, but with their upward slopes indicating again the strong effect of pretest receptive language albeit it stronger for AC-I. For target vocabulary size following intervention, the non-parallel lines again indicate interaction—in this case both AC-I and AC-O had stronger associations between initial receptive language and expressive target vocabulary size than SC, with the effect for AC-O being stronger than for AC-I. The low and essentially flat line for SC indicates effects of intervention focus were largely confined to the AC-I and AC-O groups.

Figure 1.

Regression models for effect of pretest receptive age on receptive language age, separately by intervention focus. For magnitude of the effects see Table 3.

Figure 3.

Regression models for effect of pretest receptive age on posttest target vocabulary size, separately by intervention focus. For magnitude of the effects see Table 3.

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to determine whether the relation between initial receptive language, defined here as receptive language age, and language skills following intervention, defined as receptive language age, expressive language age, and expressive target vocabulary size, was moderated by intervention focus for toddlers with significant language delay. It was hypothesized that there would be stronger associations between initial receptive language age and expressive outcomes for participants who received the input-focused AC-I intervention compared to children who received the other two interventions. Partial support was found for these predictions.

Moderating Effects of Intervention Focus

Unsurprisingly, the data showed strong positive relationships between initial receptive language age and each of the outcome variables, such that the participants who had lower initial receptive language had relatively lower language scores following intervention, and those who had higher initial receptive language had better outcomes, across the three outcome measures. Importantly, it was successfully demonstrated that the focus of the language intervention can moderate this relationship, at least for the two expressive outcomes that were evaluated.

Expressive language.

As presented in Figure 2, for expressive language age (measured by the SICD), the results showed that the participants who received the AC-I intervention demonstrated a much stronger impact of initial receptive language age compared to children who received the other two interventions. Stated another way, initial receptive language age was much more important in the AC-I intervention. The participants with the lowest initial receptive language ages demonstrated low expressive language age following intervention, even relative to those who received AC-O and SC. Participants with the highest receptive language ages in AC-I, however, demonstrated much higher expressive language ages following intervention, compared to those in the other interventions. Initial receptive language had essentially no impact on expressive language age for those in AC-O and SC. This finding was consistent with the initial hypothesis.

Figure 2.

Regression models for effect of pretest receptive age on posttest expressive language age, separately by intervention focus. For magnitude of the effects see Table 3.

One potential explanation for this is that the participants in the AC-I intervention who had low initial receptive language ages learned to comprehend vocabulary during the course of the intervention, similar to those with the beginning achievement profile described in earlier studies (e.g., Romski & Sevcik, 1996; Romski, Sevcik, Robinson, Mervis, & Bertrand, 1996). If present, this gain in comprehension would not have been reflected in a measure of expressive language, but target vocabulary comprehension in this study was not measured as a means to evaluate this explanation (discussed more in the next section). Conversely, participants in the AC-I intervention with high levels of initial receptive language may have been poised to use their receptive knowledge to understand the intervention targets, and then use them expressively, which ultimately impacted their post-intervention expressive language scores, consistent with children who exhibited the advanced achievement profile in Romski and Sevcik (1996). Consequently, it seems the AC-I intervention, with its focus on providing augmented input, may have been more sensitive to the receptive language ability of the participants who did not speak compared to the SC-I and AC-O conditions, which focused on encouraging production in speech or speech and symbols, respectively.

Expressive target vocabulary.

The moderating impact of intervention focus was different for the expressive target vocabulary outcome. As presented in Figure 3, initial receptive language age had strong positive associations with expressive target vocabulary use following intervention for participants in the two augmented language interventions. This means that, in both augmented interventions, those who had low initial receptive language ages used very few target vocabulary words following intervention, and those with high initial receptive language used many more. Furthermore, this association was slightly stronger for those in the AC-O intervention compared to those who received the AC-I intervention. Initial receptive language age was not related to expressive target vocabulary use for children in the SC intervention. The participants learned very few expressive target vocabulary words overall in the SC condition and this fact likely explains why initial receptive language was not associated with expressive vocabulary learning outcomes for this group.

The pattern of moderation for expressive target vocabulary outcomes was not consistent with the hypothesis that AC-I would show the strongest relationship. The explanation of why the relationship was stronger for the AC-O condition than for the AC-I condition is complex but also consistent with the findings of Romski et al. (2010). The AC-I intervention was designed to provide participants with augmented input, which supports symbol and spoken comprehension. Alternatively, the AC-O intervention was designed to encourage augmented output, and thus was focused on expression. For participants in the AC-O intervention, those with the highest receptive language ages prior to the intervention may have comprehended the target words despite the fact there was no modeling of use by the communication partner, and then may have begun to use those target vocabulary items expressively. Meanwhile, those with lower initial receptive language ages were likely unable to comprehend and, thus, did not produce many words by the end of the intervention. Consequently, these participants with lower receptive language ages in AC-O had to learn to comprehend target vocabulary in an environment with little support for comprehension. In contrast, those in the AC-I intervention, regardless of initial receptive language ages, may have learned to comprehend the target vocabulary, but simply did not use them expressively to the same extent as the participants in AC-O because the intervention did not require the words to be used expressively.

Different patterns for expressive language and expressive target vocabulary.

Finally, the explanation for why there was a different pattern of mediation for expressive language age and expressive target vocabulary is worth consideration. Again, this difference was not hypothesized and it was expected that initial receptive language would be most important for participants who received AC-I compared to the other interventions for both of the expressive outcomes. The difference observed may have been due to the proximal nature of the expressive target vocabulary variable vis-à-vis the interventions and the relative distal nature of the SICD expressive language age variable. It is encouraging that the participants who received the intervention that targeted the expressive use of a set of vocabulary words (i.e. AC-O) used the words expressively. Moreover, it is encouraging that, of these participants, those who had the highest initial receptive language ages ultimately used more target vocabulary words expressively, relative to those with lower initial receptive language ages. Likewise, it makes sense that the participants who received models of the vocabulary words but were not required to use the words expressively in the intervention context (i.e., AC-I) used fewer words compared to those who were expected to produce the words (i.e., AC-O), regardless of initial receptive language. It is of particular note, however, that participants in the AC-I intervention had the best performance on a distal measure of overall expressive language age when they had high initial receptive language. Taken together, it seems that, while the AC-O intervention demonstrated the best outcomes for the use of targeted vocabulary -- an intervention specific measure -- when the participants had high initial receptive language ages, the AC-I intervention may have resulted in outcomes that generalized to more distal measures of expressive language.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are three limitations to this research that bear discussion. First, the current report is a secondary and ex post facto data analysis of a previously reported study by Romski et al. (2010). As such, the original study was not specifically nor prospectively designed to answer research questions regarding the associations between initial receptive language and expressive and receptive language outcomes, or how these relationships were moderated by intervention focus. Consequently, there is a need for future research efforts to replicate our findings.

The results of this study demonstrate medium to strong effects of intervention focus on the relationship between initial receptive language and expressive language outcomes. Target vocabulary comprehension outcomes were not assessed, due to the fact that comprehension outcomes were not a part of the larger Romski et al. (2010) study. This certainly has resulted in an incomplete understanding of the relationships under examination. It is noteworthy that measuring target vocabulary comprehension, particularly in the augmented modality, would likely have been difficult for the young toddlers in the current study. One possible assessment strategy for symbol comprehension that could be used in future studies would require children to attend to an experimenter who says “show me the” while pointing to a symbol. The child must then pick the appropriate item (e.g., a stuffed animal) to show the experimenter (for more examples see Drager et al., 2006; Harris & Reichle, 2004; Romski & Sevcik, 1996). Children this young with developmental disabilities, however, often encounter difficulty pointing to stimuli. Another approach may be to track eye movements to assess comprehension of object names. Brady, Anderson, Hahn, Obermeier, and Kapa (2014) examined use of eye tracking with children with autism and found that eye gaze was a reliable indicator of vocabulary comprehension, although this has not been demonstrated in very young children with developmental disabilities. Another approach to the measurement of language comprehension is optimizing the psychometric properties of individual items on existing tests. Using item responsive theory (IRT), a group of probability models that specify the relationships between individual test items and a latent trait. Fisher (2017) explored the use of IRT with several measures of language comprehension in a sample of 113 toddlers with significant developmental delays. She found clusters of items that supported different profiles of language comprehension.

Issues of assessment notwithstanding, and considering the results of this and other studies, it is likely that children with the highest levels of receptive language prior to intervention would also demonstrate high target vocabulary comprehension after intervention. In addition, it is likely that initial receptive language and intervention condition would interact in similar ways to predict comprehension of target vocabulary. As noted elsewhere (Blockberger & Sutton, 2003; Romski et al., 2010), however, the important relation between initial receptive language and language development through augmented means is not yet well understood. In spite of the difficulty in doing so, future research should include measures of target vocabulary comprehension to better tease out these relations. In addition, future research should consider whether a hybrid intervention approach that combines input and output components that match well with the receptive language skills the child brings to intervention could maximize production outcomes. Romski et al. (2019) are examining the effects of such an intervention.

A second limitation is that the matching or speech-imitation skills of the toddlers were not evaluated prior to beginning of the intervention, even though both of these skills have been shown to be predictive of intervention outcomes (Gopnik & Meltzoff, 1987; Rogers, Hepburn, Stackhouse, & Wehner, 2003; Schlosser & Wendt, 2008). As such, matching and speech-imitation skills might have served as alternative explanations of the findings but only if the randomization procedure failed to accurately distribute these skills across the three intervention groups. This concern is assuaged, however, by the fact that the three intervention groups did not differ on expressive or receptive language age at the beginning of the study.

Finally, the original research was conducted with a sample of volunteers who expressed interest in participating. As also noted by Romski et al (2010), parents had relatively high levels of education (77% had completed college), were in their 30s, and were able to commit approximately 2 hr per week for at least 12 weeks to the study. Consequently, it is unclear whether the results of the current study would generalize to the population of children with parents who are younger and/or less well educated than the parents in the original study.

Conclusion

A strong relationship exists between initial receptive language skills and receptive and expressive augmented language intervention outcomes for toddlers with significant developmental delay. This relationship is moderated, however, by the focus of the intervention for expressive language outcomes. Specifically, the data showed that initial receptive language was a stronger predictor of expressive language age when the participants received an intervention that focused on providing models of augmented vocabulary; but for expressive vocabulary targeted in the intervention, initial receptive language was more important for those who received an intervention that focused on teaching expression. Taken together, the data suggest the importance of initial receptive language skills of toddlers with developmental delays and that initial levels can interact with intervention focus to produce differential outcomes.

Contributor Information

R. Michael Barker, University of South Florida.

Roger Bakeman, Georgia State University.

References

- Allen AA, Schlosser RW, Brock KL, & Shane HC (2017). The effectiveness of aided augmented input techniques for persons with developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 33, 149–159. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2017.1338752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Speech Language Hearing Association. (2004). Guidelines for the training, use, and supervision of speech-language pathology assistants. [Guidelines]. Available from www.asha.org/policy.

- Barker RM, Akaba S, Brady NC, & Thiemann-Bourque KS (2013). Support for AAC use in preschool, and growth in language skills, for young children with developmental disabilities. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 29, 334–346. doi: 10.3109/07434618.2013.848933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates E (1979). The emergence of symbols: Cognition and communication in infancy. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict H (1979). Early lexical development: Comprehension and production. Journal of Child Language, 6, 183–200. doi: 10.1017/S0305000900002245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs EE, Carter EW, & Gilson CB (2018). Systematic review of interventions involving aided AAC modeling for children with complex communication needs. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 123, 443–473. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-123.5.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binger C, & Light J (2007). The effect of aided AAC modeling on the expression of multi-symbol messages by preschoolers who use AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 23, 30–43. doi: 10.1080/07434610600807470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binger C, Maguire-Marshall M, & Kent-Walsh J (2011). Using aided AAC models, recasts, and contrastive targets to teach grammatical morphemes to children who use AAC. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54, 160–176. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0163) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blockberger S, & Sutton A (2003). Toward linguistic competence: Language experiences and knowledge of children with extremely limited speech In Light JC, Beukelman DR & Reichle J (Eds.), Communicative competence for individuals who use AAC (pp. 63–106). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Brady NC (2000). Improved comprehension of object names following voice output communication aid use: Two case studies. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 16, 197–204. doi: 10.1080/07434610012331279054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brady NC, Anderson CJ, Hahn LJ, Obermeier SM, & Kapa LL (2014). Eye tracking as a measure of receptive vocabulary in children with autism spectrum disorders. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 30, 147–159. doi: 10.3109/07434618.2014.904923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady NC, Steeples T, & Fleming K (2005). Effects of prelinguistic communication levels on initiation and repair of communication in children with disabilities. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48, 1098–1113. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/076) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady NC, Storkel HL, Bushnell P, Barker RM, Saunders K, Daniels D, & Fleming K (2015). Investigating a multimodal intervention for children with limited expressive vocabularies associated with autism. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24, 438–459. doi: 10.1044/2015_AJSLP-14-0093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RS, Seung H-K, Schwartz SE, & Kay-Raining Bird E (2000). Predicting language production in children and adolescents with Down syndrome: The role of comprehension. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 43, 340–350. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4302.340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Dada S, & Alant E (2009). The effect of aided language stimulation on vocabulary acquisition in children with little or no functional speech. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18, 50–64. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2008/07-0018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCiccio TJ, & Efron B (1996). Bootstrap confidence intervals. Statistical Science, 11, 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- Drager K, Postal VJ, Carrolus L, Castellano M, Gagliano C, & Glynn J (2006). The effect of aided language modeling on symbol comprehension and production in 2 preschoolers with autism. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 112–125. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2006/012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, & Dunn LM (1981). Peabody picture vocabulary test - revised. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E, Thal DJ, & Pethick SJ (1994). Variability in early communicative development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 1–173. doi: 10.1111/1540-5834.ep9502141733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher E (2017). Emerging language comprehension in toddlers with significant developmental delays: An item response theory approach. (Doctoral dissertation, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA: ). [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, Seligman MEP, & Gelman R (1976). Language in the two-year old. Cognition, 4, 189–202. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(76)90004-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens’ C (1989). Aided communication intervention before assessment: A case study of a child with cerebral palsy. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 5, 14–26. doi: 10.1080/07434618912331274926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gopnik A, & Meltzoff A (1987). The development of categorization in the second year and its relation to other cognitive and linguistic developments. Child Development, 58, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar]

- Harris MD, & Reichle J (2004). The impact of aided language stimulation on symbol comprehension and production in children with moderate cognitive disabilities. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13, 155–167. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2004/016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick DL, Prather EM, & Tobin AR (1984). Sequenced inventory of communication development (Revised). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Kent-Walsh J, & Binger C (2018). Methodological advances, opportunities, and challenges in AAC research. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 34, 93–103. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2018.1456560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer-Johnson Co.. (1981) Picture communication symbols. Stillwater, MN: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JF, & Chapman RS (1985). Systematic analysis of language transcripts. Madison: University of Wisconsin. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen EM (1995). Mullen scales of early learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, Hepburn SL, Stackhouse T, & Wehner E (2003). Imitation performance in toddlers with autism and those with other developmental disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 763–781. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romski MA, & Cheslock M (2004). Parent-coached language intervention transcription and coding manual. Georgia State University; Atlanta. [Google Scholar]

- Romski MA, & Sevcik RA (1996). Breaking the speech barrier: Language development through augmented means. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Romski MA, & Sevcik RA (2003). Augmented input: Enhancing communication development In Light JC, Beukelman DR, & Reichle J(Eds.), Communicative competence for individuals who use AAC: From research to effective practice (pp. 147–162). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Romski MA, Sevcik RA, Adamson LB, Barton-Hulsey A, Smith AL, Barker RM, … Bakeman R (2019). Parent-coached early augmented language interventions for toddlers with developmental delays: A randomized comparison. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Romski MA, Sevcik RA, Adamson LB, Cheslock M, & Smith A (2007). Parents can implement AAC interventions: Ratings of treatment implementation across early language interventions. Early Childhood Services, 1, 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Romski MA, Sevcik RA, Adamson LB, Cheslock M, Smith A, Barker RM, & Bakeman R (2010). Randomized comparison of augmented and non-augmented language interventions for toddlers with developmental delays and their parents. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53, 350–364. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0156) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romski MA, Sevcik RA, Cheslock MA, & Barton-Hulsey A (2017). The system for augmenting language: AAC and emerging language intervention In McCauley RJ, Fey ME, & Gillam RB (Eds.), Treatment of language disorders in children (2nd ed., pp. 155–186). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Romski MA, Sevcik RA, Robinson BF, Mervis CB, & Bertrand J (1996). Mapping the meanings of novel visual symbols by youth with moderate or severe mental retardation. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 100, 391–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser RW (2002). On the importance of being earnest about treatment integrity. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 18, 36–44. doi: 10.1080/aac.18.1.36.44 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser RW, & Wendt O (2008). Effects of augmentative and alternative communication intervention on speech production in children with autism: A systematic review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17, 212–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sennott SC, Light JC, & McNaughton D (2016). AAC modeling intervention research review. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 41, 101–115. doi: 10.1177/1540796916638822 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sevcik RA (2006). Comprehension: An overlooked component in augmented language development. Disability and Rehabilitation, 28, 159–167. doi: 10.1080/09638280500077804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevcik RA, & Romski MA (2002). The role of language comprehension in establishing early augmented conversations In Reichle J, Beukelman DR& Light JC(Eds.), Implementing an augmentative communication system: Exemplary practices for beginning communicators (pp. 453–474). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau N, Sutton A, & Morford JP (2014). An investigation of developmental changes in interpretation and construction of graphic AAC symbol sequences through systematic combination of input and output modalities. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 30, 187–199. doi: 10.3109/07434618.2014.940465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]