Abstract

Background

Individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD) exhibit high levels of economic demand for opioids, with high levels of consumption and relative insensitivity to changes in price. Because the medications used to treat OUD in medication-assisted therapy (MAT) act as antagonists or agonists at μ opioid receptors, they may alter the relationship between price and opioid intake.

Methods

This study examined demand for a commonly abused synthetic prescription opioid, fentanyl, in male rats following s.c. pre-treatment with naltrexone (0.1 – 1.0 mg/kg), morphine (0.3 – 3.0 mg/kg) or buprenorphine (0.3 – 3.0 mg/kg). We normalized demand curves to intake at the lowest price and estimated effects on elasticity (sensitivity to changes in price). Rats were first trained to earn fentanyl (5 μg/kg/infusion) on a fixed ratio schedule, then they underwent daily training under a threshold procedure designed to produce within-session demand curve estimates. Rats received 14 threshold sessions before undergoing a series of tests encompassing each drug, at each dose.

Results

Elasticity was increased by pretreatment with naltrexone, morphine or buprenorphine. Morphine also decreased initial intake, when the price for fentanyl was lowest. In contrast, initial intake was increased by naltrexone (according to an inverted-U shaped curve). The effects of naltrexone did not persist after the test session, but morphine and buprenorphine continued affecting demand elasticity 24 h or 48 h after the test, respectively.

Conclusions

These results indicate that fentanyl demand is sensitive to blockade or activation of opioid receptors by the drug classes used for MAT in humans.

Keywords: fentanyl, demand, behavioral economics, buprenorphine, naltrexone, morphine, MAT

1. Introduction

The recent rise in deaths related to opioid misuse has increased focus on the need for effective treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD). The most effective approach for treating OUD is medication-assisted therapy (MAT) using drugs that target primarily μ opioid receptors (Kraus et al., 2011; McCarty et al., 2018). The two classes of medication used in MAT, opioid antagonists and agonists, are used separately or together. Antagonists such as naltrexone and naloxone decrease the reinforcing effect of opioids by blocking opioid receptors (Nunes et al., 2018). However, antagonists alone are not ideal for MAT because of patient noncompliance (Ling et al., 2012) and because they can exacerbate the symptoms of withdrawal. In contrast, full agonists such as methadone and partial agonists such as buprenorphine reduce illicit opioid use by providing steady, moderate activation of opioid receptors (Clark et al., 2015). Although these medications are more effective than psychotherapy alone, at least 20–40% of patients continue misusing illicit opioids while undergoing MAT (Nunes et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2011). While there are numerous factors that lead to failure to sustain abstinence, one factor is the magnitude of an individual’s economic demand for illicit opioids, with higher demand predicting greater failures to abstain with MAT (Worley et al., 2015).

Economic demand curve analyses can be used to generate estimates of elasticity (price sensitivity) and demand intensity (consumption at low prices) for drugs of abuse (Hursh and Silberberg, 2008; Hursh and Winger, 1995). Individuals with OUD characteristically exhibit exaggerated demand, with relative insensitivity to changes in price (Hursh and Roma, 2013). This may be associated with addiction severity in humans (Murphy et al., 2011, 2009) and has been identified as a potential target for evaluating therapeutic efficacy (Hursh and Roma, 2013). While individuals that spend a greater percentage of their income on obtaining opioids prior to entering MAT are less likely to achieve abstinence during treatment (Worley et al., 2015), it is unclear if individuals using illicit opioids during MAT continue to exhibit the same degree of economic demand. Because medications act on the same receptors as abused opioids, they may alter demand by serving as substitutes or by changing the effective price of a drug (Hursh and Roma, 2013). Although MAT reduces the frequency of drug use in humans (Kakko et al., 2003), it is not known from human or non-human animal studies if MAT directly alters the metrics of demand, such as elasticity.

In the current study, we used male rats to determine if economic demand for fentanyl is altered following treatment with drugs that target primarily μ opioid receptors. Rats were trained to self-administer fentanyl (5 μg/kg/infusion), then they transitioned to a threshold procedure in which unit doses were decreased across 10-min components in order to derive a within-session demand curve estimation (Oleson et al., 2011). After responding stabilized, we obtained normalized demand curves following pretreatment with varying doses of naltrexone (opioid antagonist), morphine (classic full μ-opioid agonist), and buprenorphine (mixed/partial μ-opioid agonist).

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Subjects

A total of 12 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (225–275g) were ordered from Envigo (Indianapolis, IN). Rats were housed individually in a temperature-controlled colony room on a 12:12-h light schedule (lights on at 0800 h). Experiments occurred daily between 0800 and 1100 h. Upon arrival, rats were handled daily for 7 days before undergoing surgery for catheter implantation using previously published procedures (Weiss et al., 2018). Rats had ad libitum access to food and water and all procedures were in accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (National Research Council, 2011) and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky. Four rats were unable to complete the study due to catheter failure.

2.2. Apparatus

Fentanyl self-administration sessions occurred in standard operant chambers (28 × 24 × 21 cm; ENV-008CT; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA) housed in sound-attenuated chambers equipped with a fan. Each operant chamber was equipped with two levers, a cue light above each lever, a house light, and a syringe pump. Rats were randomly assigned to have one lever (left or right) designated as the active lever.

2.3. Fentanyl self-administration

2.3.1. Pre-training

Rats learned to self-administer fentanyl during 7 days of twice-daily acquisition sessions, followed by 7 days of once-daily maintenance sessions. During the twice-daily acquisition sessions, the first session was always an autoshaping session and the second session was either another autoshaping session (day 1) or a post-autoshaping operant session (days 2–7), where infusions were delivered on a FR schedule of reinforcement, with one infusion for each lever press (FR1). Rats returned to their home cages for 2 h between the first and second sessions of the day. All once-daily maintenance sessions were FR1.

For autoshaping sessions, the inactive lever was always available while the active lever extended every 3–9 min, on a random interval. After either 15 s or an active lever press, that lever retracted and the rat received an infusion of fentanyl (0.1 ml, 5 μg/kg/infusion, 5.9 s). Rats received a total of 5 infusions during the first 45 min of each autoshaping session, the active lever was unavailable for the final 15 min.

For FR1 sessions, the active lever was extended for the duration of the 60-min session and rats could earn infusions of fentanyl (0.1 ml, 5 μg/kg/infusion, 5.9 s) according to an FR1 schedule. The cue lights above both levers were illuminated for 20 s following the start of each infusion. Rats could not earn additional infusions while the cue lights were illuminated.

2.3.2. Threshold procedure

After pre-training, rats began daily sessions with a threshold procedure (Oleson and Roberts, 2012; Zittel-Lazarini et al., 2007). During each 110-min session, rats could earn progressively smaller doses of fentanyl on an FR3 schedule. The duration of infusion decreased across 11 blocks, lasting 10 min each, by 0.25 log per block (infusion duration of 5.9, 3.32, 1.87, 1.05, 0.59, 0.33, 0.19, 0.11, 0.06, 0.03 and 0.02 s), so that the dose of drug earned per infusion decreased from 5 μg/kg to 0.017 μg/kg. As a result, the price per unit (1 μg/kg) of fentanyl increased from 0.6 responses to 177 responses by the final block of each session. The cue lights above both levers illuminated during infusions and responses during this period had no consequence. Rats completed 14 threshold sessions before the start of testing.

2.3.3. Test sessions

In the next phase, rats were tested with the threshold procedure following acute pretreatment [subcutaneous (s.c.), 5 min prior to session] with varying doses of either naltrexone, morphine or buprenorphine; there were 2 threshold maintenance sessions between each test (no pretreatment). Rats completed a total of 12 tests as follows: 0, 0.1, 0.3 and 1 mg/kg naltrexone; 0, 0.3, 1, and 3 mg/kg morphine; and 0, 0.3, 1 and 3 mg/kg buprenorphine. For each pretreatment drug, all doses were tested during consecutive tests; Latin square designs were used to determine the orders of drug pretreatment and dose. Because we found evidence that there were carryover effects of 3 mg/kg buprenorphine that persisted for at least 2 days, we omitted the data from all tests occurring 3 days after this dose.

2.4. Data analysis

Responses during both pre-training and FR1 training were analyzed with mixed multiple linear regression, where lever was a within-subjects factor and day was a continuous within-subjects factor. During threshold sessions, mixed effect models were used to analyze initial (first block) intake, with day and dose as continuous within-subjects factors. For drug effects on initial intake, likelihood ratio testing was used to choose between linear or quadratic dose effects; dose was log transformed (with 0.01 added as a constant) because this transformation improved model fit. These analyses were conducted with SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) using PROC GLIMMIX. Although previous studies have recommended using only the final 10 blocks to generate demand curves (Bentzley et al., 2013; Oleson et al., 2011; Yates et al., 2017), the effects of pretreatment on responding during the first block caused us to include initial intake (5 μg/kg * infusions in the first block) into the model as a separate term and then to normalize the data to the initial intake. The exponentiated form of the Hursh and Silberburg (2008) demand model (Koffarnus et al., 2015) was used to fit demand curves:

where Q is normalized consumption [(100*infusions*dose)/(initial intake)], C is unit price [log10(FR/dose), expressed as the difference from the price in the initial block], Q0 is demand intensity (consumption at the lowest price considered; set as a constant equaling 100 because of the normalization procedure), α is demand elasticity (sensitivity to unit price), and k is a scaling constant which was set equal to 2.1 for all analyses, following an initial examination of each dataset.

For threshold acquisition, an estimate of α was attained through non-linear mixed effects modeling (NLME; Beckmann and Young, 2009; Pinheiro et al., 2017; Yates et al., 2017) of the demand model with block (7 sessions) as a continuous factor and subject as a random factor. To determine if stability had been achieved prior to the start of testing, separate models were also fit for the first and second half of threshold acquisition sessions. For drug effects, an estimate of α was attained through demand model fits implemented via NLME, with subject as a random factor and dose as either a linear fixed factor or as both a linear and quadratic fixed factor. For each drug, model fit was assessed using a likelihood ratio and the best fitting dose effect model was used for all subsequent tests with a given drug. Separate model fits were carried out for each drug on pretreatment day and 24 h later; an additional 48 h later assessment was carried out for buprenorphine. Curves were generated in GraphPad Prism 8.2.1 (Graph-Pad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) using the parameter estimates. GraphPad Prism was used to obtain estimates of dose effects on latency. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Pre-training

Responding on the active lever increased over the course of pre-training. In the FR1 sessions occurring after each autoshaping session (Fig. 1a, left), there was a significant interaction between lever and day (F1,92 = 20.5, p < 0.001), with the number of lever presses changing across days for the active lever (F1,42 = 46.2, p < 0.001), but not for the inactive lever. After the autoshaping phase, analysis of the remaining FR1 acquisition sessions (Fig. 1a, right) revealed a significant main effect of lever (F1,8 = 111, p < 0.001), but there was no longer any effect of day or any interaction.

Figure 1.

(A) Responding for fentanyl during pre-training and acquisition of the threshold procedure (n = 9). Rats responded more on the active lever during daily FR1 training sessions. Sessions occurring during the autoshaping phase (A, left) were analyzed separately from the remaining FR1 training sessions (A, right). (B) During the threshold task, initial intake was similar during sessions 1–7 and 8–14. (C) Fentanyl demand (normalized to initial intake) and (D) estimates of elasticity were also similar during the first and second half of threshold training sessions. * p < 0.05 positive slope for relationship between day and lever presses; #p < 0.05 slope of line differs in active vs inactive; +p < 0.05 effect of lever.

3.2. Threshold procedure

Acquisition using the threshold procedure occurred over the course of 14 sessions. There was no effect of block on initial intake (Fig. 1b), occurring during the first (lowest-priced) block of each session (p = 0.9). NLME analysis for the first and second half of training (Fig. 1c) revealed no difference between the first and second half of training sessions on normalized demand for fentanyl or on the parameter estimate of α (Fig. 1d; p = 0.11). However, when the effect of session on normalized demand was analyzed within each block, session affected the estimate of α for the first block (data not shown; F1,661= 16.8, p < 0.001), but not the second block (p = 0.27), indicating that demand stabilized by the second half of training.

3.3. Test Sessions

3.3.1. Naltrexone

Pretreatment with naltrexone affected initial intake (Fig. 2A), with significant linear (F1,21 = 9.58, p = 0.006) and quadratic (F1,21 = 11.0, p = 0.003) dose effects in the quadratic equation (likelihood of quadratic vs linear: 15.9, p < 0.001). This appeared to be caused by high intake following the lowest dose. Intake during subsequent blocks was normalized to initial intake and analysis with NLME revealed a dose-dependent decrease in demand for fentanyl (Fig. 2B), with a linear dose effect on the estimate of α (Fig. 2C; F1,342 = 4.42, p = 0.036). The effect was linear, as the addition of a quadratic term did not improve fit (likelihood = 0.086, p = 0.77). Thus, there was a dose-dependent increase in elasticity of fentanyl demand following naltrexone. This change in elasticity was not associated with a change in latency to earn the first infusion (data not shown; p = 0.57). Naltrexone had no effect on initial intake (Fig. 2D; linear p = 0.78, quadratic p = 0.91) during the subsequent training session that occurred 24 h later (Fig. 2E). Analysis of normalized fentanyl intake revealed that the linear dose-dependent effect of previous-session naltrexone on α did not reach significance (Fig. 2F; p = 0.08).

Figure 2.

Effects of naltrexone pretreatment on (A) initial fentanyl intake, (B) normalized fentanyl demand, and (C) the estimate of elasticity during the test session (n = 9). Naltrexone had dose-dependent effects on initial intake (quadratic) and the elasticity of normalized demand (linear). Note that the scale for elasticity (C) is 20-fold higher than elasticity at baseline (Fig 1D) or elasticity 24 h later (F), while the scale for initial intake (A) is 2-fold higher than in any other graph presented here. During the subsequent maintenance session, 24 h later, there was no effect of previous naltrexone on (D) initial intake, (E) normalized demand or (F) the estimate of elasticity, although there may have been a trend for an effect on elasticity (p = 0.08). Initial intake was used to normalize demand. *p < 0.05 linear dose-dependent effect; ^p < 0.05 quadratic dose-dependent effect.

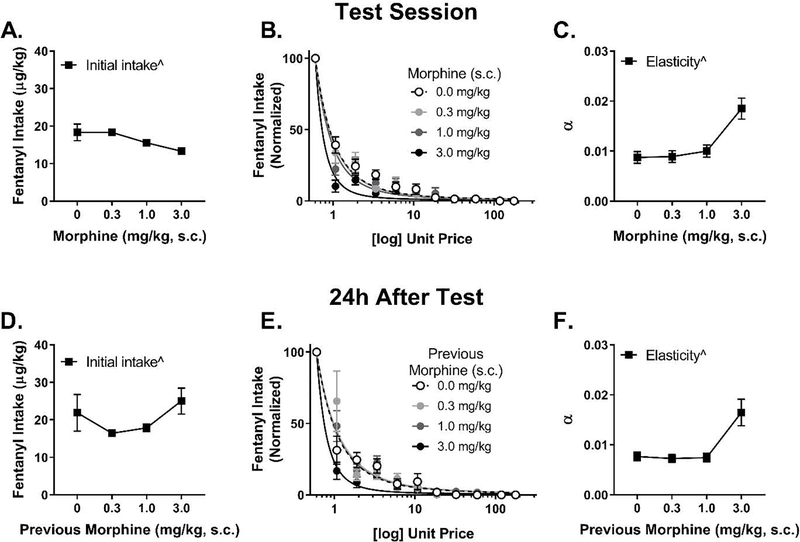

3.3.2. Morphine

Although morphine pretreatment 5 min prior to the session affected initial fentanyl intake (Fig. 3A), only the quadratic dose effect term was significant (F1,25 = 4.57, p = 0.042) in the quadratic equation (likelihood of quadratic vs linear: 7.35, p = 0.007). During subsequent blocks, analysis of normalized demand (Fig. 3B) revealed a significant quadratic dose effect of morphine on elasticity of demand for fentanyl (Fig. 3C; F1,385 = 6.69, p = 0.010), although the linear term in the quadratic model was not significant (p = 0.75). This effect was quadratic, as adding the quadratic term improved model fit (likelihood = 5.57, p = 0.018). Thus, increasing doses of morphine reduced initial intake and increased elasticity. The effect of morphine on intake and elasticity was not associated with any change in latency to earn the first infusion (data not shown; p = 0.47). During the training session that occurred 24 h later, morphine continued to have a quadratic dose effect on initial fentanyl intake (Fig. 3D; F1,18 = 4.43, p = 0.050) and to affect normalized demand for fentanyl (Fig. 3E and 3F; quadratic term: F1,308 = 9.37, p = 0.002; linear term: p = 0.09). However, 48 h after the morphine test session, there were no significant effects (results not shown).

Figure 3.

Effects of morphine pretreatment on (A) initial fentanyl intake, (B) normalized fentanyl demand, and (C) the estimate of elasticity during the test session (n = 9). Morphine had dose-dependent effects on initial intake (quadratic) and the elasticity of normalized demand (quadratic); although these curves were fit with a quadratic model, the dose response appears to be monophasic. Morphine continued to affect (D) initial intake, (E) normalized fentanyl demand, and (F) the estimate of elasticity 24 h after the test session. There was increased elasticity at the highest dose and an inverted U-shaped effect on initial intake 24 h after. Initial intake was used to normalize demand. ^p < 0.05 quadratic dose-dependent effect.

3.3.3. Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine pretreatment 5 min prior to the session had no effect on initial intake (Fig. 4A), though the quadratic model was better fitting than a linear one (likelihood: 6.58, p = 0.010). However, buprenorphine did alter normalized demand for fentanyl (Fig. 4B and 4C) during subsequent blocks (F1,310 = 10.8, p = 0.001). This effect of dose was linear, as model fit was not significantly improved by inclusion of the quadratic term (likelihood: 1.14, p = 0.29). Thus, buprenorphine increased elasticity as a function of dose but had no effect on initial intake. Despite the lack of effect on initial intake, buprenorphine did increase latency to earn the first infusion during the first block of the test session (data not shown; slope estimate = 35.5±15.1, F1,30 = 5.50, p = 0.026), with average latency increasing from 9.03±2.96 s to 114±72.1 s at the highest dose. Buprenorphine continued to affect the elasticity of normalized fentanyl intake 24 h later (Fig. 4E and 4F; F1,255 = 10.7, p = 0.001) and 48 h later (Fig. 4H and 4I; F1,277 = 22.4, p < 0.001). For initial intake, however, there was only a trend toward an effect 24 h after the test (Fig. 4D, linear term p = 0.094, quadratic term p = 0.059), and no effect 48 h after (Fig. 4G). Buprenorphine continued to affect latency to earn the first infusion after 24 h (data not shown; slope = 89.6±28.3, F1,28 = 10.0, p = 0.004), but not after 48 h (p = 0.15).

Figure 4.

Effects of buprenorphine pretreatment on (A) initial intake, (B) normalized fentanyl demand and (C) the estimate of elasticity during the test session (n = 8). Although buprenorphine did not affect initial intake, the mixed agonist increased elasticity in a linear dose-dependent fashion, leading to lower fentanyl demand. Buprenorphine continued to exert these effects 24 h after the test session (D-F) and 48 h after the test session (G-I). Note that the scale for elasticity during the maintenance session 24 h after buprenorphine treatment (F) is 5-fold higher than at baseline (Fig 1D). Initial intake was used to normalize demand. *p < 0.05 linear dose-dependent effect.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of MAT on fentanyl demand

Although recent preclinical studies have characterized economic demand for opioids (Fragale et al., 2019; Lacy et al., 2019; Porter-Stransky et al., 2017; Stafford et al., 2019), previous research examining the effect of various drug pretreatments on opioid self-administration has been conducted with simple FR schedules. With FR schedules, selective antagonists such as naloxone or naltrexone produce a biphasic dose effect, with low doses increasing and high doses decreasing heroin self-administration (Hemby et al., 1996; Koob et al., 1984). In contrast, full agonists such as methadone and partial agonists such as buprenorphine produce a monophasic dose-dependent decrease in heroin self-administration (Chen et al., 2006; Mello and Negus, 1998). The current study sought to extend these findings by utilizing a behavioral economics approach to assess drug pretreatment effects on economic demand for the high-potency opioid agonist fentanyl. The current results showed that each of the drugs tested, naltrexone, morphine and buprenorphine, similarly increased elasticity (price sensitivity). Buprenorphine and morphine had monophasic effects on elasticity. Naltrexone also had a monophasic effect on elasticity, but there was also a classical, inverted U–shaped antagonist dose effect on initial intake, with greatest intake following the lowest dose of naltrexone.

Although previous studies conducted with FR schedules have found biphasic effects of naltrexone pretreatment, we observed a biphasic effect only during the initial 10-min block. On subsequent 10-min blocks in the demand curve analysis, naltrexone had a linear dose effect on elasticity. Because we were interested in the effects of the pretreatments on both initial intake and the maintenance of intake across increasing prices, we chose to normalize consumption to intake during the first block, when the price was lowest (Hursh and Winger, 1995). It is thought that the period of initial intake during the lowest-priced block is when rats rapidly increase blood concentrations, whereas subsequent blocks reflect willingness to pay increasing prices to maintain blood concentrations (Bentzley et al., 2013; Oleson et al., 2011; Yates et al., 2017). Thus, rats may have initially attempted to surmount the effects of naltrexone, resulting in a biphasic effect on initial intake, but then failed to maintain that level of responding as price increased due to a linear reduction in the reinforcing efficacy of fentanyl.

Although naltrexone, morphine and buprenorphine each have different mechanisms of action, each pretreatment increased the elasticity of demand for fentanyl. Naltrexone may increase effective unit price by reducing the functional potency of a given dose of fentanyl (Hursh and Roma, 2013). In contrast, agonists may serve as economic substitutes for fentanyl by activating the same receptor target. In support of this, both morphine (Mierzejewski et al., 2007) and buprenorphine (Wade et al., 2015) are self-administered in rodent studies, suggesting that they could serve as substitute commodities. However, based on previous research, it is unlikely that either agonist tested would fully substitute for the effects of fentanyl. For example, although methadone is a full agonist at μ opioid receptors and substitutes for heroin by preventing withdrawal symptoms, it does not substitute for the euphorigenic effects of heroin (Hursh and Roma, 2013); the same incomplete substitution may be evident for the full agonist tested here (morphine). Buprenorphine is a mixed opioid agonist/antagonist, serving as an agonist at the nociception receptor, a partial agonist at the μ receptor, and an antagonist at the δ and κ receptors (Brown et al., 2011; Elkader and Sproule, 2005). Thus, buprenorphine may reduce demand by partially substituting for fentanyl at the μ receptor, but also via actions at other receptor subtypes.

4.2. Extended effects of agonist pretreatment

Although we observed extended (24–48 h) effects of both morphine and buprenorphine, it is not clear if these extended effects were due to the continued presence of the drugs in brain because we did not conduct a pharmacokinetic analysis. In the case of morphine, the plasma half-life is relatively short in rat (0.9 h; Barjavel et al., 1995), suggesting minimal levels would be available 24 h after pretreatment at the doses tested. For buprenorphine, however, the plasma half-life is considerably longer (4–5 h; Gopal et al., 2002) and there is a higher affinity for, and slower dissociation from, the μ opioid receptor (Pontani et al., 1985; Villiger and Taylor, 1981; Volpe et al., 2011). Within the dose range tested in the current study (0.3–1 mg/kg), buprenorphine has prolonged (48+ h) effects on operant responding for food under a multiple schedule (Dykstra, 1983). Moreover, low doses of buprenorphine (0.05–0.5 mg/kg) produce analgesia and hyperactivity for at least 8-h in rats (Gades et al., 2000; Liles and Flecknell, 1992).

It is interesting to note that the effects of buprenorphine treatment were greatest 24-h after treatment. This may be related to buprenorphine’s active metabolites, which can serve as agonists at the μ, δ, κ and/or nociceptive/orphanin FQ receptors (Azzam et al., 2019; Brown et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2001; Ohtani et al., 1994), whereas buprenorphine is an antagonist at δ and κ. Norbuprenorphine’s ability to serve as an agonist at the δ receptor may explain the persistent effects of buprenorphine treatment on latency to respond for fentanyl, as norbuprenorphine and δ agonists reduce locomotor activity (Brown et al., 2011; Sudakov et al., 2011). Another explanation for buprenorphine’s relatively weak effects on the test day, relative to subsequent days, is that the time between injection and the start of the session (5 min) may have been too brief.

4.3. Limitations

One caveat in interpreting the current results is that the pharmacokinetic time-course of each pretreatment may affect how the drug impacted the threshold task. This caveat is not unique to this study, however, as blood levels of any pretreatment drug would be expected to vary dynamically across the extended session (110 min) required to derive the demand curve. In the case of buprenorphine, for example, the Tmax is at least 1 h following s.c. injection (Clark et al., 2014). Thus, even though the 5-min pretreatment time is sufficient for buprenorphine to exhibit antinociceptive effects (Bulka et al., 2004; Dum and Herz, 1981; Gades et al., 2000; Kouya et al., 2002), blood levels would be expected to be initially low, and then rise to a peak midway through the 110 min session. Because normalized demand depends on the estimate of lowest-priced intake, the magnitude of the findings may have been different had the lowest price occurred at a different point on the pharmacokinetic curve for each of the treatments examined here. In any case, the fact that the buprenorphine-induced increase in elasticity observed on the first test session was observed again 24 and 48 h later, well past the Tmax, suggests that the effects on parameter estimates observed on the first test were not an artifact of the Tmax occurring during the session.

Another caveat is that each pretreatment may have produced alterations in locomotor activity (either hypo or hyperactivity) that interacted with responding for fentanyl. In general, high doses of opioid agonists decrease activity (Bartoletti et al., 1999; Browne and Segal, 1980), while low doses increase activity, and this latter effect can sensitize across repeated injections (Moerke and Negus, 2019; Shippenberg et al., 1996; Trujillo et al., 2004), Here, buprenorphine increased latency to the first infusion, which could reflect sedation or a change in motivation for fentanyl. Future work could use a choice procedure to separate changes in response rate from behavioral allocation (Banks and Negus, 2017), as has been used recently with fentanyl (Townsend et al., 2019).

4.4. Implications for clinical treatment

We have found that both agonists and antagonists increase the elasticity of opioid demand, an effect that exists despite the antagonist initially increasing fentanyl intake. From a clinical perspective, this finding suggests that attempts to surmount the effects of antagonist therapy or opioid-blocking immunotherapies would not necessarily diminish their effectiveness against economic demand. The persistent effects we observed suggest that individuals continuing to misuse opioids during MAT may still experience a beneficial decrease in economic demand for illicit opioids, which may persist beyond the half-life of the treatment medication. Notably, the therapeutic formulations of MAT compounds used in humans have half-lives of 20 to 177 h (Dunbar et al., 2006; Elkader and Sproule, 2005; Glue et al., 2016) and therefore may have large windows of effectiveness, even after discontinuation of treatment. The FDA is currently interested in validating preclinical endpoints that reflect clinical outcomes like “harm-reduction” as alternatives to the standard metric of “sustained total abstinence”. Using a back-translational approach, we have shown that behavioral economic analysis may be one such alternative.

Highlights.

Behavioral economic analysis can be used with fentanyl self-administration

Elasticity of fentanyl demand is sensitive to activation or blockade of opioid receptors

Demand for fentanyl decreases following naltrexone, morphine or buprenorphine

Buprenorphine continued affecting fentanyl demand at least 48 h after treatment

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Justin Strickland for his expert advice and assistance with generating demand curves in R.

Role of funding source Funding for LRH provided by NIDA T32 training grant DA16176; study funding provided by NIDA P50 DA05312.

Supported by NIH grants P50 DA05312 and T32 DA016176.

Footnotes

5. Author disclosures

Conflict of Interest: No conflict declared.

No conflicts to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Azzam AAH, McDonald J, Lambert DG, 2019. Hot topics in opioid pharmacology: mixed and biased opioids. Br. J. Anaesth 122, e136–e145. 10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks ML, Negus SS, 2017. Insights from Preclinical Choice Models on Treating Drug Addiction. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 38, 181–194. 10.1016/j.tips.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barjavel MJ, Scherrmann JM, Bhargava HN, 1995. Relationship between morphine analgesia and cortical extracellular fluid levels of morphine and its metabolites in the rat: a microdialysis study. Br. J. Pharmacol. 116, 3205–3210. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15125.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoletti M, Gaiardi M, Gubellini C, 1999. Effects of buprenorphine on motility in morphine post-dependent rats. Pharmacol. Res 40, 327–332. 10.1006/phrs.1999.0517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann JS, Young ME, 2009. Stimulus Dynamics and Temporal Discrimination: Implications for Pacemakers. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process 35, 525–537. 10.1037/a0015891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentzley BS, Fender KM, Aston-Jones GS, 2013. The behavioral economics of drug self-administration: A review and new analytical approach for within-session procedures. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 226, 113–125. 10.1007/s00213-012-2899-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Holtzman M, Kim T, Kharasch ED, 2011. Buprenorphine metabolites, buprenorphine-3-glucuronide and norbuprenorphine-3-glucuronide, are biologically active. Anesthesiology 115, 1251–1260. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318238fea0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne RG, Segal DS, 1980. Behavioral activating effects of opiates and opioid peptides. Biol. psychiatry 15, 77–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulka A, Kouya PF, Böttiger Y, Svensson JO, Xu XJ, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, 2004. Comparison of the antinociceptive effect of morphine, methadone, buprenorphine and codeine in two substrains of Sprague-Dawley rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol 492, 27–34. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SA, O’Dell LE, Hoefer ME, Greenwell TN, Zorrilla EP, Koob GF, 2006. Unlimited access to heroin self-administration: Independent motivational markers of opiate dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology 31, 2692–2707. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RE, Baxter JD, Aweh G, O’Connell E, Fisher WH, Barton BA, 2015. Risk Factors for Relapse and Higher Costs Among Medicaid Members with Opioid Dependence or Abuse: Opioid Agonists, Comorbidities, and Treatment History. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 57, 75–80. 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TS, Clark DD, Hoyt RF, 2014. Pharmacokinetic comparison of sustained-release and standard buprenorphine in mice. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci 53, 387–391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dum JE, Herz A, 1981. In vivo receptor binding of the opiate partial agonist, buprenorphine, correlated with its agonistic and antagonistic actions. Br. J. Pharmacol 74, 627–633. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb10473.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar JL, Turncliff RZ, Dong Q, Silverman BL, Ehrich EW, Lasseter KC, 2006. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of long-acting injectable naltrexone. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 30, 480–490. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00052.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra LA, 1983. Behavioral effects of buprenorphine and diprenorphine under a multiple schedule of food presentation in squirrel monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 226, 317–323. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkader A, Sproule B, 2005. Buprenorphine: Clinical pharmacokinetics in the treatment of opioid dependence. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 44, 661–680. https://doi.org/4471 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragale JE, Pantazis CB, James MH, Aston-Jones G, 2019. The role of orexin-1 receptor signaling in demand for the opioid fentanyl. Neuropsychopharmacology. 10.1038/s41386-019-0420-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gades NM, Danneman PJ, Wixson SK, Tolley EA, 2000. The magnitude and duration of the analgesic effect of morphine, butorphanol, and buprenorphine in rats and mice. Contemp. Top. Lab. Anim. Sci. 39, 8–13. 10.1258/la.2008.008999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glue P, Cape G, Tunnicliff D, Lockhart M, Lam F, Gray A, Hung N, Hung CT, Harland S, Devane J, Howes J, Weis H, Friedhoff L, 2016. Switching Opioid-Dependent Patients From Methadone to Morphine: Safety, Tolerability, and Methadone Pharmacokinetics. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 960–965. 10.1002/jcph.704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal S, Tzeng Bin T, Cowan A, 2002. Characterization of the pharmacokinetics of buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine in rats after intravenous bolus administration of buprenorphine. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 15, 287–293. 10.1016/S0928-0987(02)00009-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemby SE, Smith JE, Dworkin SI, 1996. The effects of eticlopride and naltrexone on responding maintained by food, cocaine, heroin and cocaine/heroin combinations in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 277, 1247–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Kehner GB, Cowan A, Liu-Chen LY, 2001. Comparison of pharmacological activities of buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine: norbuprenorphine is a potent opioid agonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 297, 688–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Roma PG, 2013. Behavioral economics and empirical public policy. J. Exp. Anal. Behav 99, 98–124. 10.1002/jeab.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Silberberg A, 2008. Economic Demand and Essential Value. Psychol. Rev 115, 186–198. 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Winger G, 1995. Normalized demand for drugs and other reinforcers. J. Exp. Anal. Behav 64, 373–84. 10.1901/jeab.1995.64-373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakko J, Dybrandt Svanborg K, Jeanne Kreek M, Heilig M, 2003. 1-year retention and social function after buprenophrine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for herion dependence in Sweden: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 361, 662–668. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12600-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Franck CT, Stein JS, Bickel WK, 2015. A modified exponential behavioral economic demand model to better describe consumption data. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 23, 504–512. 10.1037/pha0000045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Pettit HO, Ettenberg A, Bloom FE, 1984. Effects of opiate antagonists and their quaternary derivatives on heroin self-administration in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 229, 481–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouya PF, Hao JX, Xu XJ, 2002. Buprenorphine alleviates neuropathic pain-like behaviors in rats after spinal cord and peripheral nerve injury. Eur. J. Pharmacol 450, 49–53. 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)02052-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus ML, Alford DP, Kotz MM, Levounis P, Mandell TW, Meyer M, Salsitz EA, Wetterau N, Wyatt SA, 2011. Statement of the American society of addiction medicine consensus panel on the use of buprenorphine in office-based treatment of opioid addiction. J. Addict. Med 5, 254–263. 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182312983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy RT, Austin BP, Strickland JC, 2019. The influence of sex and estrous cyclicity on cocaine and remifentanil demand in rats. Addict. Biol 1–10. 10.1111/adb.12716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liles JH, Flecknell PA, 1992. The effects of buprenorphine, nalbuphine and butorphanol alone or following halothane anaesthesia on food and water consumption and locomotor movement in rats. Lab. Anim 26, 180–189. 10.1258/002367792780740558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling W, Mooney L, Wu LT, 2012. Advances in Opioid Antagonist Treatment for Opioid Addiction. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am 35, 297–308. 10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D, Priest KC, Korthuis PT, 2018. Treatment and Prevention of Opioid Use Disorder: Challenges and Opportunities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 39, 525–41. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Negus SS, 1998. The effects of buprenorphine on self-administration of cocaine and heroin “speedball” combinations and heroin alone by rhesus monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 285, 444–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierzejewski P, Stefanski R, Bienkowski P, Kostowski W, 2007. History of cocaine self-administration alters morphine reinforcement in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 562, 77–81. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.01.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moerke MJ, Negus SS, 2019. Role of agonist efficacy in exposure-induced enhancement of mu opioid reward in rats. Neuropharmacology 151, 180–188. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Skidmore JR, Pederson AA, 2009. Reliability and Validity of a Demand Curve Measure of Alcohol Reinforcement. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 17, 396–404. 10.1037/a0017684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Tidey JW, Brazil LA, Colby SM, 2011. Validity of a demand curve measure of nicotine reinforcement with adolescent smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 113, 207–214. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council, 2011. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academies Press, Washington, D.C: 10.17226/12910 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes EV, Gordon M, Friedmann PD, Fishman MJ, Lee JD, Chen DT, Hu MC, Boney TY, Wilson D, O’Brien CP, 2018. Relapse to opioid use disorder after inpatient treatment: Protective effect of injection naltrexone. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 85, 49–55. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani M, Kotaki H, Uchino K, Sawada Y, Iga T, 1994. Pharmacokinetic analysis of enterohepatic circulation of buprenorphine and its active metabolite, norbuprenorphine, in rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 22, 2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleson EB, Richardson JM, Roberts DCS, 2011. A novel IV cocaine self-administration procedure in rats: Differential effects of dopamine, serotonin, and GABA drug pre-treatments on cocaine consumption and maximal price paid. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 214, 567–577. 10.1007/s00213-010-2058-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleson EB, Roberts DCS, 2012. Cocaine Self-Administration in Rats: Threshold Procedures, in: Psychiatric Disorders. Methods in Molecular Biology. pp. 303–319. 10.1007/978-1-61779-458-2_20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, Team R-C, 2017. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models . R Packag. version 3.1–131. [Google Scholar]

- Pontani RB, Vadlamani NL, Misra AL, 1985. Disposition in the rat of buprenorphine administered parenterally and as a subcutaneous implant. Xenobiotica. 15, 287–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter-Stransky KA, Bentzley BS, Aston-Jones G, 2017. Individual differences in orexin-I receptor modulation of motivation for the opioid remifentanil. Addict. Biol. 22, 303–317. 10.1111/adb.12323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, Heidbreder C, Lefevour A, 1996. Sensitization to the conditioned rewarding effects of morphine: pharmacology and temporal characteristics. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford NP, Kazan TN, Donovan CM, Hart EE, Drugan RC, Charntikov S, 2019. Individual vulnerability to stress is associated with increased demand for intravenous heroin self-administration in rats. Front. Behav. Neurosci 13, 1–15. 10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudakov SK, Nazarova GA, Kolyasnikova KN, Kolpakov AA, Bashkatova VG, 2011. Effect of peripheral administration of peptide ligands of δ-opioid receptors on anxiety level and locomotor activity of rats. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med 151, 661–663. 10.1007/s10517-011-1409-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend EA, Negus SS, Caine SB, Thomsen M, Banks ML, 2019. Sex differences in opioid reinforcement under a fentanyl vs. food choice procedure in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2–9. 10.1038/s41386-019-0356-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo KA, Kubota KS, Warmoth KP, 2004. Continuous administration of opioids produces locomotor sensitization. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 79, 661–669. 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villiger JW, Taylor KM, 1981. Buprenorphine: Characteristics of binding sites in the rat central nervous system. Life Sci. 29, 2699–2708. 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90529-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe DA, Tobin GAMM, Mellon RD, Katki AG, Parker RJ, Colatsky T, Kropp TJ, Verbois SL, 2011. Uniform assessment and ranking of opioid Mu receptor binding constants for selected opioid drugs. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 59, 385–390. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2010.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade CL, Vendruscolo LF, Schlosburg JE, Hernandez DO, Koob GF, 2015. Compulsive-like responding for opioid analgesics in rats with extended access. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 421–428. 10.1038/npp.2014.188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Potter JS, Fiellin DA, Byrne M, Connery HS, Dickinson W, Gardin J, Griffin ML, Gourevitch MN, Haller DL, Hasson AL, Huang Z, Jacobs P, Kosinski AS, Lindblad R, McCance-Katz EF, Provost SE, Selzer J, Somoza EC, Sonne SC, Ling W, 2011. Adjunctive counseling during brief and extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for prescription opioid dependence: a 2-phase randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 1238–46. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss VG, Yates JR, Beckmann JS, Hammerslag LR, Bardo MT, 2018. Social reinstatement: a rat model of peer-induced relapse. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 235, 3391–3400. 10.1007/s00213-018-5048-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worley MJ, Shoptaw SJ, Bickel WK, Ling W, 2015. Using behavioral economics to predict opioid use during prescription opioid dependence treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 148, 62–68. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates JR, Bardo MT, Beckmann JS, 2017. Environmental enrichment and drug value: A behavioral economic analysis in male rats. Addict. Biol 10.1111/adb.12581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zittel-Lazarini A, Cador M, Ahmed SH, 2007. A critical transition in cocaine self-administration: Behavioral and neurobiological implications. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 192, 337–346. 10.1007/s00213-007-0724-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]