Summary

Studies have shown an overlap of Aβ plaques, tau tangles, and α-synuclein (α-syn) pathologies in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) with dementia (PDD) patients, with increased pathological burden correlating with severity of cognitive and motor symptoms. Despite the observed co-pathology and concomitance of motor and cognitive phenotypes, the consequences of the primary amyloidogenic protein on the secondary pathologies remain poorly understood. To better define the relationship between α-syn and Aβ plaques, we injected α-syn preformed fibrils (α-syn mpffs) into mice with abundant Aβ plaques. Aβ deposits dramatically accelerated α-syn pathogenesis and spread throughout the brain. Remarkably, hyper-phosphorylated tau (p-tau) was induced in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice. Finally, α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice showed neuron loss which correlated with the progressive decline of cognitive and motor performance. Our findings suggest a “feed-forward” mechanism whereby Aβ plaques enhance endogenous α-syn seeding and spreading over time post-injection with mpffs.

Keywords: alpha-synuclein, amyloid-beta plaques, dementia, parkinsonism, dementia, Lewy Bodies, Parkinson’s disease, Comorbidity

eTOC Blurb

Bassil et al. describe a new model that shows how Aβ plaques in the brain can potentiate α-synuclein pathogenesis. The authors provide evidence pointing to the interaction of both proteins in the brain leading to neurodegeneration.

Introduction

Neurodegenerative disorders (NDDs) are associated with a unique set of accumulating pathological proteins including hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) in neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), or α-synuclein (α-syn) as Lewy bodies (LB) in Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Galasko et al., 1994; Jankovic, 2008; Spillantini and Goedert, 2016). Many studies have shown that a large percentage of AD patients (>50%) exhibit significant LB pathology alongside Aβ plaques and NFTs, while other studies have revealed the presence of Aβ plaques and NFTs in LB disorders (LBD) leading to the neuropathological diagnoses of PD with dementia (PDD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) (Bergeron and Pollanen, 1989; Colom-Cadena et al., 2013; Hamilton, 2000; Irwin et al., 2017; Irwin et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2018). The presence of co-pathology in NDD brains is accompanied by overlapping clinical symptoms in patients, a more rapid decline in cognition and motor performance, and shortened lifespan (Hansen et al., 1990; Irwin et al., 2017; Irwin et al., 2013). This pathological and clinical correlation prompted our interest in understanding the mechanism(s) whereby different comorbid pathological protein aggregates contribute to different NDD phenotypes.

In PDD and DLB, the presence of Aβ plaques is associated with cortical α-syn aggregation and spreading (Hamilton, 2000; Lashley et al., 2008; Pletnikova et al., 2005). Studies using transgenic (Tg) models have suggested a possible synergistic relationship between α-syn and Aβ (Chia et al., 2017; Clinton et al., 2010; Mandal et al., 2006; Masliah et al., 2001; Ono et al., 2012; Spencer et al., 2016; Tsigelny et al., 2008). For example, bigenic mice with Aβ plaques, tau tangles, and α-syn pathology exhibit exacerbated behavioral impairment associated with increases in CNS pathological α-syn, tau, and Aβ burdens (Clinton et al., 2010; Masliah et al., 2001). Further, reducing α-syn expression in a Tg mouse model of AD rescued and reversed the AΟ pathology-induced neurodegenerative phenotype (Spencer et al., 2016). In-vitro studies have shown that α-syn and Aβ form hetero-oligomers and promote the aggregation of one another (Chia et al., 2017; Masliah et al., 2001; Ono et al., 2012; Tsigelny et al., 2008). While the results from these published studies are compelling, the effects of Aβ plaques on α-syn seeding and cell-to-cell transmission have yet to be assessed thoroughly.

Prior injection studies have shown that Aβ extracted from AD-confirmed cases was able to self-template and induce pathology in a prion-like manner in-vivo (Kane et al., 2000; Meyer-Luehmann et al., 2006). Similarly, human α-syn preformed fibrils (hpffs) generated from recombinant α-syn have been shown to initiate seeding and spreading of α-syn pathology in the mouse brain (Luk et al., 2016; Masuda-Suzukake et al., 2013; Rey et al., 2016). Of note, mouse α-syn preformed fibrils (mpffs) were shown to be more efficient than hpffs in pathological seeding and spreading when injected into the mouse brain (Luk et al., 2016; Rey et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2016). Additionally, one strain of α-syn mpffs has been reproducibly shown to promote tau aggregation in a process termed cross-seeding (Giasson et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2013). Cross-seeding may be a possible mechanism through which Aβ could potentiate an increase in α-syn pathology in the AD brain.

To determine if the α-syn pathology in LBD cases that exhibit AD pathology can be recapitulated in animal model systems, we injected α-syn mpffs into Tg mice with abundant Aβ plaques (5xFAD mice). We hypothesized that hippocampal injection of α-syn mpffs into 5xFAD mice would significantly potentiate the seeding and spreading of α-syn pathology in an AD-like Aβ plaque environment.

Results

Aβ plaque abundance positively correlated with cortical α-syn scores in LBD patients.

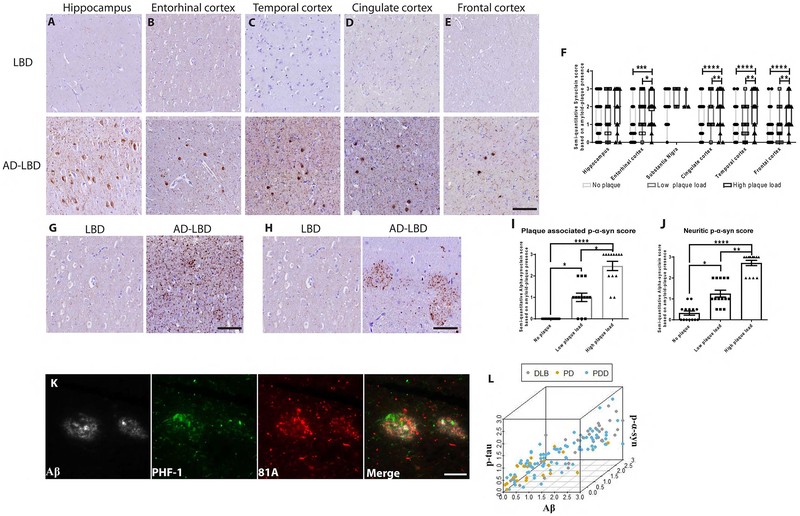

Brain samples from PD, PDD and DLB patients showed abundant plaque-associated phosphorylated α-syn (p-α-syn) in the hippocampus and cortical regions of PPD and DLB brains. For comparison, there was little to no plaque-associated p-α-syn in PD brains with few plaques (Figure 1A–E). Analysis showed that the α-syn pathology in cortical regions was positively associated with the Aβ plaque load (Figure 1F). Interestingly, p-α-syn scores did not differ in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc), likely attributable to the absence of Aβ plaques in this structure (Figure 1F). Further analysis showed that the increased abundance of Aβ plaques in LBD was positively associated with increased neuritic p-α-syn and plaque-associated dystrophic neurite p-α-syn staining (Figure 1G–J). Triple IF labeling showed that p-α-syn-positive neurites, p-tau were within the plaques (Figure 1K). While previous studies have mainly focused on the relationship between tau-positive neurites and Aβ plaques, our data point to a three-way positive correlation between α-syn, Aβ, and tau (Figure 1L).

Figure 1: Aβ plaque burden is positively correlated with plaque associated p-α-syn pathology in human LBD cases with concomitant AD pathology.

Representative images using MAb 81A p-α-syn pathology on tissue sections from the (A) hippocampus, (B) entorhinal cortex, (C) temporal cortex, (D) cingulate cortex and (E) frontal cortex in PD patients (LBD) with only α-syn pathology and LBD patients with concomitant AD pathology (AD-LBD) Scale bar: 20 μm. F) A grouped bar graph shows a positive association between Aβ plaque load and semi-quantitative α-syn score. G, H) IHC conducted on frontal cortex sections using p-α-syn using 81A showing neuritic staining in AD-LBD brains. Scale bar: 20 μm. I, J) A bar graph shows a positive correlation between Aβ plaque burden and the induction of (G) dystrophic neurite and (H) neuritic p-α-syn in LBD and AD-LBD patients. A Kruskal-Wallis test was used for the analysis in (G) and (H) (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001). K) IF triple-labeling was conducted for Aβ (grey), p-tau (green), and p-α-syn (red) using NAB228, PHF-1, and 81A, respectively. Scale bar: 20 μm. The spatial organization and close association of each protein are seen when all three channels are merged. L) Three-way correlation between Aβ, p-α-syn, and p-tau semi-quantitative scores ascribed to all PD, PDD, and DLB cases (Spearman correlation; Aβ/α-syn: r=0.82, accounting for tau r=0.62; tau/α-syn: r=0.74, accounting for Aβ r=0.44).

Aβ plaques increase α-syn pathology and spreading in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice compared to α-syn mpff-injected WT littermates

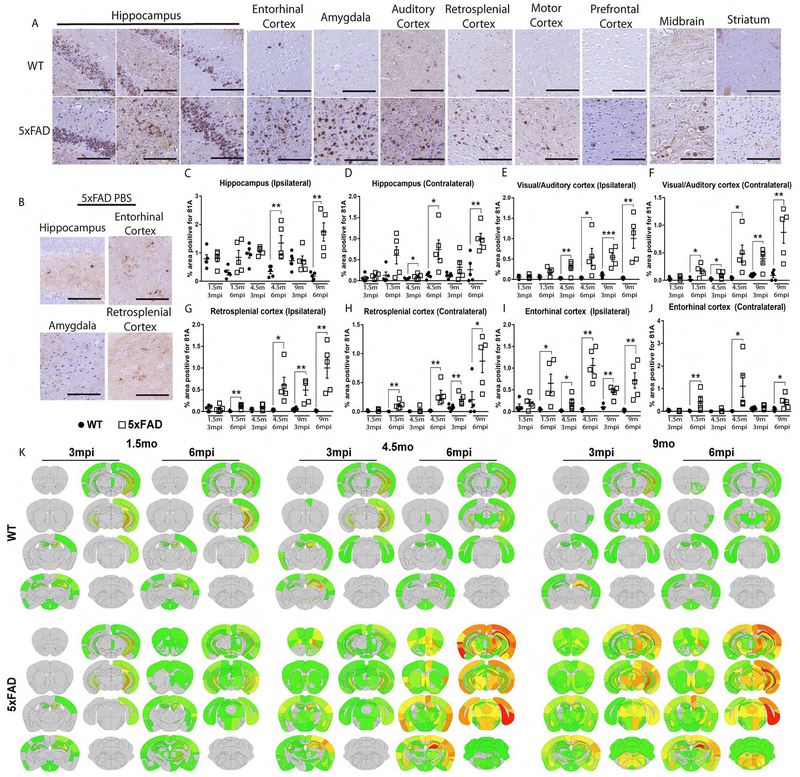

As describe in methods, we injected α-syn mpffs into 5xFAD Tg mice and WT littermates. Although both 5xFAD and WT mice express only endogenous mouse α-syn, increased widespread 81A-positive α-syn pathology was observed in the 5xFAD-α-syn mpff-injected mouse brains compared to α-syn mpff-injected WT littermate brains (Figure 2A). Quantification of 81A staining showed similar levels of p-α-syn pathology in the ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampus of WT and 5xFAD mice at 3mpi. However, a significant increase was observed in the contralateral hippocampus of 4.5 mo3mpi α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice as compared to WT mice (Figure 2C, D). At 6mpi, a significant increase in p-α-syn was observed in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice compared to WT mice (Figure 2C, D). Age-matched PBS-injected-5xFAD mice showed low levels of p-α-syn in the hippocampus, retrosplenial cortex, and entorhinal cortex (Figure 2B).

Figure 2: α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice display abundant p-α-syn pathology compared to their WT counterparts.

(A) IHC was conducted as described in methods using 81A on sections form α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice and α-syn mpff-injected WT littermates, as well as (B) PBS-injected 5xFAD mice. Grouped bar graphs of 81A-positive p-α-syn pathology as described in the results (C-J) of 5xFAD mice (grey bars) and WT littermates (black bars). A two-tailed t-test was used when the data was normally distributed. If the data was not normally distributed, a Mann-Whitney test was used. (K) Heat maps of p-α-syn (based on 81A staining) as shown in the figure and described in the text of α-syn mpff-injected WT and 5xFAD mice. The increase in α-syn pathology in 5xFAD relative to WT mice is reflected by the color change from grey (no pathology) to red (saturation of pathology). (n=5-6 mice per group). *p<0.05,**p<0.01,***p<0.001. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Next, we quantified p-α-syn in cortical regions with known hippocampal connections (Figure 2). Increased p-α-syn spreading was observed in 5xFAD mice compared to WT littermates in cortical regions connected to the injection site as shown in Figures 2E–J with significant increases of α-syn pathology in the visual and auditory cortices of the α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD (Figure 2E, F). p-α-syn levels were also significantly increased in the retrosplenial cortex of 5xFAD (Figure 2G, H). Finally, comparison of α-syn in the entorhinal cortex, which is directly connected to the hippocampus and a severely affected structure in LBD (Goldman et al., 2012; Oh et al., 2014), showed a significant increase in α-syn pathology (Figure 2I and J). Moreover, 5xFAD mice injected with α-syn mpffs exhibited a different transmission pattern of α-syn pathology compared to α-syn mpff-injected WT littermates. Our analysis of this spreading is summarized in a semi-quantitative heatmap shown in Figure 2K.

Similarly, α-syn mpff injections into APPKI, another Aβ plaque-bearing mouse model (Saito et al., 2014), showed enhanced spreading of α-syn pathology compared to WT mice (Supplementary Figure 1). Increased 81A-positive α-syn pathology was observed in the APPKI-α-syn mpff-injected mouse brains compared to α-syn mpff-injected WT littermate brains (Supplementary Figure 1A, B). Quantification of 81A staining in the hippocampus of APPKI and WT mice showed similar levels of p-α-syn pathology at 3 and 6 mpi in the ipsilateral hippocampus (Supplementary Figure 1A–C). However, p-α-syn was significantly increased in the contralateral hippocampus of α-syn mpff-injected APPKI compared to WT mice (Supplementary Figure 1A, B, D). An increase in p-α-syn spreading was also observed in APPKI mice compared to WT mice in cortical regions connected to the injection site (Supplementary Figure 1).

To further confirm p-α-syn pathological spread, α-syn pathology was measured using Syn506, a mature beta-pleated sheet α-syn pathology marker (Luk et al., 2012) (Supplementary Figure 2). A significant increase in mature α-syn pathology was also found similar to p-α-syn analysis. Moreover, the p-α-syn pathology observed in 5xFAD PBS-injected mice was Syn506 negative, suggesting the presence of immature α-syn aggregates in PBS-injected-5xFAD mice (Supplementary Figure 2B).

Increased insoluble and phosphorylated α-syn in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice compared to α-syn mpff-injected WT littermates

Next, we measured α-syn levels biochemically as shown in Supplementary Figure 3, which showed a significant increase in pelleted insoluble α-syn from the hippocampus of α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD compared to WT mice (Supplementary Figure 3A, E, G, K). Consistent with our IHC results, insoluble α-syn pathological aggregates were also found in the auditory and visual cortices (Supplementary Figure 3B, E, H, K) and entorhinal cortex (Supplementary Figure 3C, E, I, K) of α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD compared to α-syn mpff-injected WT littermates. Moreover, 5xFAD mice displayed significantly greater insoluble p-α-syn than their WT littermates in the hippocampus (Supplementary Figure 3A, F, G, L) auditory and visual cortex (Supplementary Figure B, F, H, L), and the entorhinal cortex (Supplementary Figure 3C, F, I, L). ELISA analysis also showed a significant increase in insoluble α-syn in young and old α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice compared to WT (Supplementary Figure 3M). These data strengthen our hypothesis that the presence of Aβ plaques augments pathological α-syn aggregation and transmission throughout the brain.

Soluble α-syn levels were not affected by α-syn mpff injection in WT or 5xFAD (Supplementary Figure 3A–C, D, G–I, J). α-syn mRNA expression in PBS- and α-syn mpff-injected WT and 5xFAD mice were similar showing that α-syn mpff injection did not induce an increase in endogenous α-syn production (Supplementary Figure 3N, O). PBS-injected 5xFAD and WT mice exhibited similar α-syn mRNA levels in the hippocampus (Supplementary Figure 3N) and cortex (Supplementary Figure 3O), indicating that the presence of Aβ plaques did not significantly affect endogenous α-syn gene expression throughout the different structures of the brain.

LBD-brain-derived α-syn actively seeds α-syn pathology in Aβ plaque-bearing Tg mice

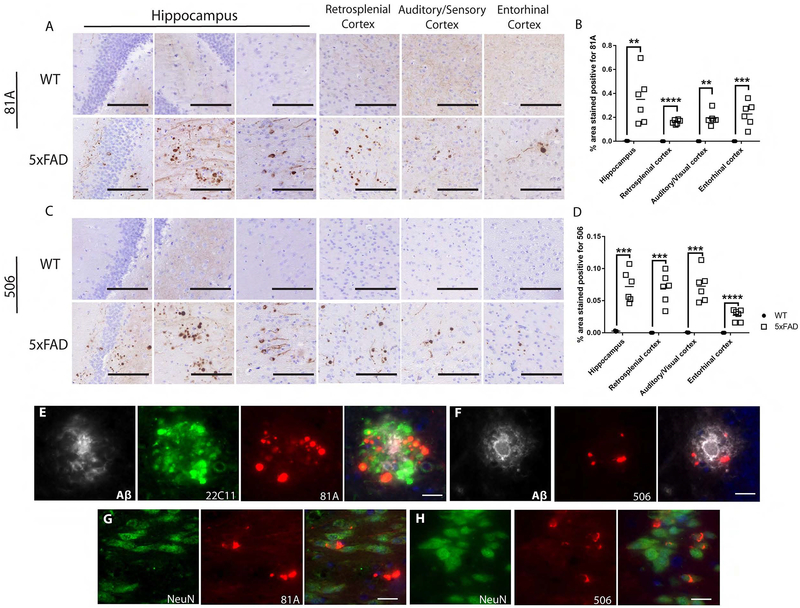

Previous studies have reported the inability of human-LBD-derived (hu-LBD) pathological α-syn to seed endogenous mouse α-syn to form LBD-like pathology in WT mice (Luk et al., 2016; Masuda-Suzukake et al., 2013; Rey et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2016). Since Aβ plaques enhance the formation of α-syn pathology in α-syn mpff-injected mice, we injected 5xFAD and WT littermates with hu-LBD-derived α-syn and followed them for 3 mpi. A significant amount of mature p-α-syn pathology (as detected by 81A and Syn506 respectively) was present as early as 3 mpi in 5xFAD mice (Figure 3A–D). Interestingly, such mature p-α-syn pathology was not found in WT mice at 3 mpi (Figure 3). Statistical analysis of the area occupied by p-α-syn pathology showed a significant increase in hu-LBD-derived α-syn-injected 5xFAD mice compared to WT littermates injected with the same material. Mature p-α-syn pathologies in 5xFAD mice were mainly in dystrophic neurites (Figure 3E, F) with some neuronal LB-like pathology at 3 mpi (Figure 3G, H). Statistical analysis of syn-506 surface area stain revealed a significant increase in 5xFAD compared to WT injected mice (Figure 3C, D). Thus, although injections of LBD-brain derived pathological α-syn does not induce α-syn pathology in WT mice, 5xFAD mouse brains show rapid induction of α-syn pathology with distinct LBD-like molecular features.

Figure 3: Human brain-derived pathological α-syn seeds p-α-syn and α-syn pathology in 5xFAD mice.

(A, C, E-H) are representative images from 4.5 mo 3 mpi with LBD brain-derived pathological α-syn in WT and 5xFAD mice. IHC used 81A (A) and Syn-506 (C) sections from LB-α-syn-injected 4.5 mo 3 mpi 5xFAD mice and age- and sex-matched WT littermates 3 mpi. Scatterplots display quantification of 81A-positive (B) and 506-positive (D) α-syn pathology as a percentage of the area occupied in the ipsilateral hippocampus, visual/auditory cortices, retrosplenial cortex and entorhinal cortex of 5xFAD mice (open squares) and WT littermates (black circles). A two-tailed t-test was performed to calculate the difference in 81A and 506 surface area between groups for each structure. If the data was not normally distributed, a Mann-Whitney test was used *p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. E) IF triple-labelling was conducted for p-α-syn (red) in dystrophic neurites (green) around Aβ plaques (grey), using 81A, 22C11, and NAB228, respectively. F) IF double-labelling was conducted for conformationally altered-α-syn pathology (red) around Aβ plaques (grey), using 506 and NAB228, respectively. G) IF double-labelling was conducted for p-α-syn (red) in neurons (green), using 81A and NeuN, respectively. H) IF triple-labelling for conformationally altered-α-syn pathology (red) in neurons (green), using 506 and NeuN. Black scale bar: 100 μm. White scale bar: 20 μm. (n=5-6 mice per group).

Aβ plaques lead to the rapid recruitment of pathological α-syn to dystrophic plaque-associated neurites

To elucidate potential mechanisms underlying the accelerated induction of α-syn pathology in 5xFAD mice, we injected α-syn mpffs into WT, 5xFAD and APPKI mice and followed them for 7 days-post-injection (dpi) (Supplementary Figure 4A–C, Supplementary Figure 1K). At this short dpi interval, α-syn mpff-injected WT mice did not show any p-α-syn pathology (Supplementary Figure 4A, 1K), while α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD and APPKI mice displayed p-α-syn pathology localized to the Aβ plaque perimeter as dystrophic neurites (Supplementary Figure 1K, L, 4C, H). Interestingly, PBS-injected 5xFAD mice showed a low level of p-α-syn in the peri-plaque regions (Supplementary Figure 4B).

These results indicate that, in the presence of Aβ plaques, α-syn readily misfolds and aggregates as early as 7 dpi and potentiates the appearance of cell body α-syn pathology as early as 45 dpi (Supplementary Figure 4D). We show that the proportion of dystrophic neurite α-syn decreases with time as neuronal α-syn aggregates appear. Importantly, this pool of α-syn in dystrophic neurites is still found in 5xFAD at 180 dpi (Supplementary Figure 4C–G). Our data also implicate dystrophic neurites as the initiation site of α-syn pathology, as well as a prime factor in the induction and transmission of α-syn pathology. This might be due to Aβ plaque-induced synaptic degeneration and the formation of dystrophic neurites (He et al., 2018; Sadleir et al., 2016) which then harbored, pooled, or sequestered endogenous α-syn that is “seeding ready”.

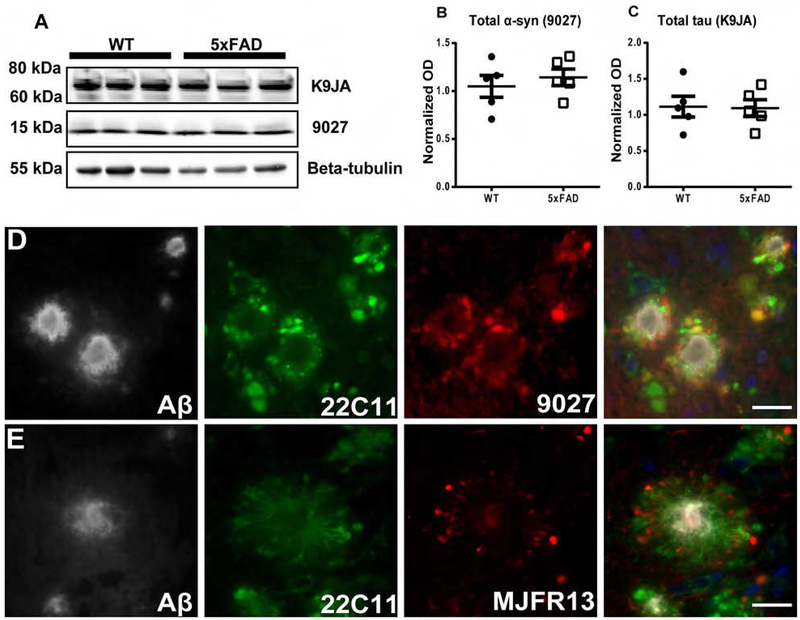

Aβ plaques redistribute endogenous α-syn and tau to dystrophic neurites

We then assessed endogenous α-syn in PBS-injected 8 mo-old injected WT and 5xFAD mice by WB and IHC (Figure 4). Quantitative immunoblot analysis showed similar amounts of endogenous α-syn between these groups (Figure 4A, B). Endogenous tau levels were also similar between WT and 5xFAD mice as previously described (He et al., 2018) (Figure 4A, C). Thus, the presence of Aβ plaques induces a redistribution of α-syn to dystrophic neurites which might serve as a central reservoir for α-syn seeding and spreading in 5xFAD mice. Also, we detected endogenous α-syn by IF around Aβ plaques in the brains of PBS-injected 5xFAD, and APPKI mice (Figure 4D, Supplementary Figure 1M) and p-α-syn was found in PBS-injected 5xFAD mice localized to dystrophic neurites where α-syn has been shown to pool (Figure 4E).

Figure 4: α-syn is pooled and phosphorylated in dystrophic neurites surrounding Aβ plaques.

A) Immunoblots were conducted on whole brain lysates from 10 mo old non-injected WT and 5xFAD mice as shown in the figure and described in results. Quantification showed similar levels of endogenous mouse α-syn (B) and tau (C) proteins. Scale bar, 40 μm. D) As shown here and described in results, IF triple-labelling showed the re-localization and pooling of endogenous α-syn (red) APP positive neurites (green) around Aβ plaques (grey), using 9027, 22C11, and NAB228, respectively. (E) IF triple-labelling of p-α-syn (red) in dystrophic neurites (green) around Aβ plaques (grey) was conducted using MJFR13, 22C11, and NAB228, respectively. White scale bar: 20 μm. A two-tailed t-test was performed. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. (n=5 mice per group).

WT and 5xFAD mice were injected with monomeric α-syn since previous work has shown that monomeric α-syn does not seed α-syn in WT mouse brains(Luk et al., 2012). Interestingly, monomeric α-syn was also capable of inducing some neuronal and plaque-associated 506-positive pathology in 5xFAD mice at 3 mpi (Supplementary Figure 5). For comparison, no 506-positive pathology was found in monomer-injected WT mice or age-matched PBS-injected 5xFAD mice. These results support the role of Aβ plaques in readily promoting α-syn seeding and spreading in dystrophic neurites by altering the native distribution of endogenous α-syn.

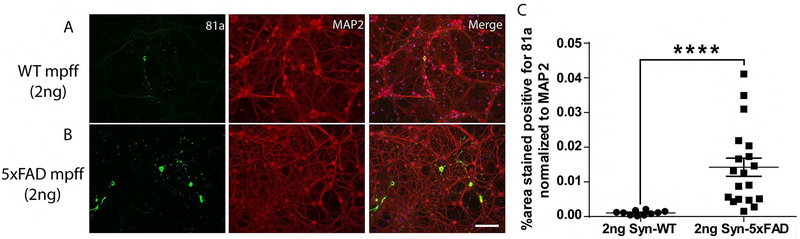

Aβ plaques and their cellular environment induce a more aggressive α-syn strain

Next, we extracted α-syn from the brains of WT and 5xFAD mice injected with α-syn mpffs or PBS. Equal amounts of pelleted/insoluble α-syn (2 ng) from these extracts were added to primary cultures of hippocampal neurons (Figure 5). Interestingly, insoluble α-syn lysate from α-syn mpffs-injected 5xFAD mice was more potent at inducing α-syn pathology when compared with 2 ng of insoluble α-syn from α-syn mpffs-injected WT mice (Figure 5 A–C). Further, α-syn pathology observed in neurons transduced with α-syn extracted from α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mouse brain lysates induced more cytoplasmic IF α-syn staining (Figure 5 B) than observed in neurons transduced with α-syn extracted from α-syn mpff-injected WT mouse brain (Figure 5 A).

Figure 5: α-syn (2ng) extracted from α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice induces more α-syn pathology than α-syn (2ng) purified from α-syn mpff-injected WT mice.

IF double-labelling showed increased 81A-positive p-α-syn pathology (green) in neurons transduced with α-syn extracted from α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice (B) compared to neurons transduced with α-syn extracted from α-syn mpff-injected WT mice (A). Scale bar: 100 μm. C) A Mann-Whitney test confirmed the significant increase in 81A positive staining (p<0.0001) ****p<0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

Control transduction experiments enabled us to rule out likely confounds that could account for enhanced α-syn pathology in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice. For example, immuno-depletion of 85% of pathological α-syn from α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mouse brain lysate failed to seed α-syn pathology in neurons compared to non-depleted conditions (Supplementary Figure 6 A, B, E, F, G). α-syn enriched from PBS-injected 5xFAD brain lysates and co-transduction of a total of 2 ng of α-syn from a mixture of α-syn mpffs and α-syn enriched from PBS-injected 5xFAD brain lysates failed to seed a comparable amount of α-syn pathology in neuron cultures (Supplementary Figure 6 C–E). Thus, our results point to a synergistic mechanism whereby Aβ facilitates the seeding and spreading of α-syn pathology. More importantly, these data support the idea that α-syn pathology generated in the presence of Aβ plaques leads to a more potent strain than α-syn pathology generated in their absence.

Aβ/α-syn co-pathology leads to autophagy impairments

The presence of Aβ plaques increased α-syn pathology in the brain but did not influence α-syn expression levels following α-syn mpff brain injections (Supplementary Figure 2N, O). We thus assessed the functionality of autophagic processing, the unfolded protein response (UPR), and the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) in 5xFAD and WT mice as a possible explanation for the increase in α-syn pathology (Supplementary Figure 7). Although the autophagy-lysosome pathway mediates intraneuronal clearance of accumulated α-syn (Cuervo et al., 2004), studies suggest that α-syn aggregates can impair autophagy and lead to neuron loss (Luna et al., 2018; Tanik et al., 2013). Compared to PBS-injected WT mice, α-syn mpff-injected WT mice showed a significant increase in p62, a marker of proteostasis impairment (Cohen-Kaplan et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016) (Supplementary Figure 7A, D, E).

Protein clearance is impaired to a greater extent in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice due to the accumulation of α-syn around Aβ plaques. Specifically, we noted that in the soluble fraction, the levels of p62 in mpff-injected 5xFAD mice are increased compared to PBS-injected WT mice and PBS-injected 5xFAD (Supplementary Figure 7A, D). In the insoluble fraction, p62 levels were increased in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD compared to PBS-injected 5xFAD mice, PBS-injected and α-syn mpff-injected WT mice (Supplementary Figure 7A, E). p62 plays a dual role in cellular proteolysis as it has been linked to both autophagy and the UPS (Cohen-Kaplan et al., 2016). We thus measured ubiquitin, K48- and K63-linked polyubiquitin chains in order to assess proteasomal degradation under co-pathology conditions (Supplementary Figure 7B, C, F–H). Ubiquitin levels were increased in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice compared to the other groups (Supplementary Figure 7B, F). K48-linked polyubiquitin chains levels were significantly decreased in all 3 groups compared to PBS-injected WT mice albeit α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD showed the most significant decrease of all groups (Supplementary Figure 7C, G). Analysis of K63-linked polyubiquitin chains levels showed a significant increase in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice compared to PBS-injected WT and 5xFAD mice in addition to α-syn mpff-injected WT mice (Supplementary Figure 7C, H). Interestingly, α-syn pathology was both p62- and ubiquitin-positive under co-pathology conditions while Aβ plaques were only ubiquitin positive (Supplementary Figure 7I). Impaired autophagy was also confirmed by measuring protein clearance using LC3 since α-syn/Aβ co-pathology led to a significant increase in LC3-2 in α-syn mpff 5xFAD mice compared to all groups (Supplementary Figure 7J, L). α-syn mpff-injection in WT mice also showed a significant increase in LC3-2 levels compared to PBS injected-WT mice (Supplementary Figure 7J, L). We then assessed ER stress by measuring BIP and p-eIF2α, two markers of the UPR. No significant difference was found between PBS-injected WT mice and α-syn mpff-injected WT mice. BIP levels in PBS-injected 5xFAD mice were significantly decreased compared to α-syn mpff-injected WT mice. Under co-pathology conditions, BIP was found to be significantly decreased in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD compared to PBS-injected WT mice and α-syn mpff-injected WT mice (Supplementary Figure 7J, M). Importantly, p-eIF2α a downstream effector of BIP, was significantly increased in PBS- and α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD compared to PBS-injected WT mice and α-syn mpff-injected WT mice (Supplementary Figure 7J, N). Thus, these results point to a potential role of Aβ plaques in altering protein clearance in the 5xFAD mice that could possibly drive the observed increase in α-syn pathology leading to a feed-forward loop of increased protein load resulting in further protein clearance impairment.

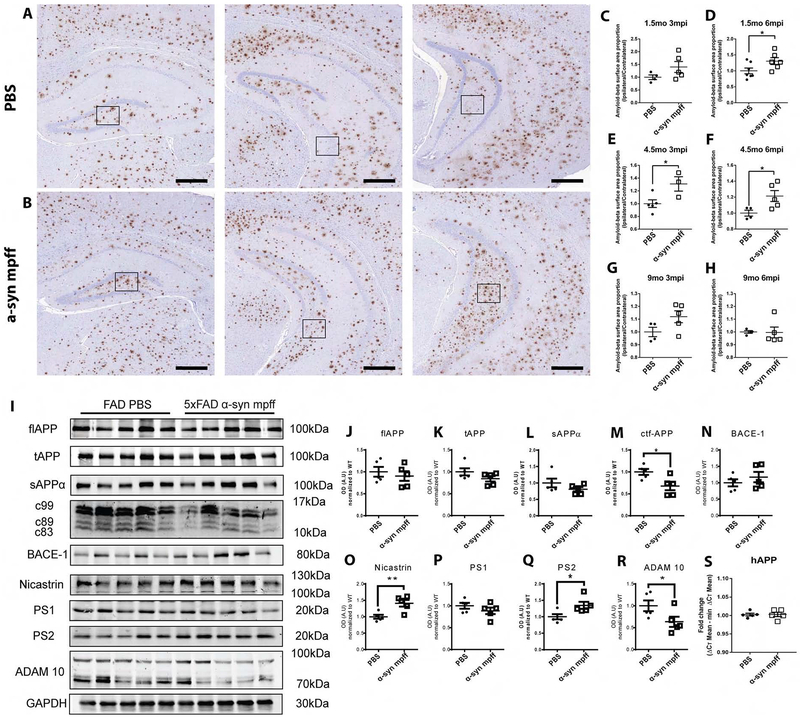

α-syn mpff injections exacerbate Aβ plaque pathology in 5xFAD mice.

To determine the effect of α-syn mpff injection on Aβ plaque burden, we immuno-stained sections for Aβ in 5xFAD mice (Figure 6). 5xFAD mice injected with α-syn mpffs showed a significant increase in Aβ plaque burden compared to aged matched PBS-injected 5xFAD mice (Figure 6A, B, D, E, F). No significant differences Aβ plaque burden were found between groups at 1.5mo3mpi and 9mo3mpi and 6 mpi (Figure 6C, G, H). The lack of an increase at these time points might be explained by the relatively low level of hippocampal plaques in young 5xFAD mice and the complete saturation of Aβ plaques in old 5xFAD mice (Oakley et al., 2006). These results are consistent with a bidirectional synergistic mechanism where Aβ plaques alter synaptic homeostasis and induce synaptic dystrophy, leading to the accumulation of α-syn. With α-syn sequestration, more APP is available as substrate for β/γ secretase processing, resulting in an increase of Aβ1-42 (Bate et al., 2010; Roberts et al., 2017; Sadleir et al., 2016). We thus assessed APP processing in PBS- and α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD (Figure 6I–R). No significant difference was noted in full length APP, total APP (tAPP) or cleaved sAPPα between groups (Figure 6I–L). Moreover, we detected a significant decrease in C-terminal fragments of APP in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD compared to PBS-injected 5xFAD mice (Figure 6I, M). No significant difference in β-secretase marker BACE-1 was noted between groups (Figure 6I, N). However, we observed a significant increase in nicastrin (Figure 6I, O) and PS2 (Figure 6I, Q), two central components of the γ-secretase complex. No significant difference was seen in the third member of the γ-secretase complex PS1 (Figure 6I, P). Interestingly, ADAM10, an α-secretase marker, was significantly decreased in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD compared to PBS-injected 5xFAD mice (Figure 6I, R). Our results are thus in accordance with the literature as α-syn induces an increase in APP processing thus inducing an increase in Aβ plaque formation. Notably, no differences were noted in APP mRNA between PBS- and α-syn mpffs-injected 5xFAD mice (Figure 6S), ruling out the possibility that the increase in Aβ in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD relative to PBS mice was caused by alterations in APP mRNA transcription.

Figure 6: α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice showed an increased hippocampal Aβ plaque burden relative to PBS-injected 5xFAD mice.

IHC was conducted as described in methods on hippocampal sections from 10 mo PBS-injected 5xFAD mice (A) and α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice (B). Black scale bar: 400 μm. C-H) A significant increase in Aβ plaques in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice. For each mouse, an ipsilateral to contralateral ratio was calculated, thereby minimizing inter-mouse variability. I) Immunoblot probing for APP processing mechanism was conducted on the soluble fractions from the hippocampus of 4.5mo6mpi PBS and α-syn mpffs-injected 5xFAD. Comparison was done between PBS and α-syn mpffs injected-5xFAD mice for each structure (J-R). S) hAPP qPCR was done to measure APP mRNA levels. See figure and results for details. A two-tailed t-test was used when the data was normally distributed. If the data was not normally distributed, a Mann-Whitney test was used. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.*p < 0.05, **p<0.01. (n=5 mice per group).

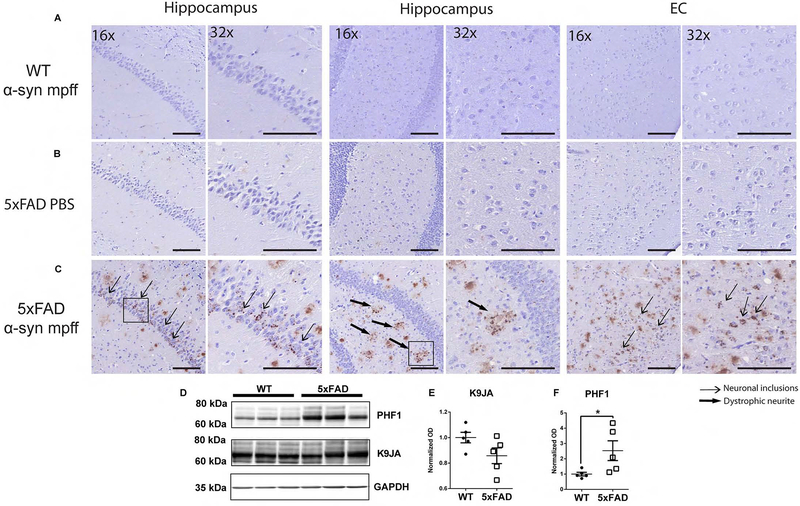

Aβ/α-syn co-pathology in 5xFAD mice enhances tau hyperphosphorylation

Aβ plaques and NFTs are hallmarks of AD (Bennett et al., 2017; He et al., 2018), while we, and others, have shown that endogenous mouse tau is mislocalized around Aβ plaques in dystrophic neurites where it may facilitate the templated recruitment of mouse tau to aggregate by pathological AD NFT tau seeds (He et al., 2018; Sadleir et al., 2016). Other studies have shown similar findings (Giasson et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2013). PBS injection in 5xFAD mice and α-syn mpff injection in WT mice did not induce an increase in tau hyperphosphorylation (Figure 7A, B). Interestingly, α-syn mpff injections into the hippocampus of 5xFAD mice cross-seeded tau and induced an increase in p-tau in the hippocampus and cortical regions as dystrophic neurites around Aβ plaques and AD-like NFTs (Figure 7C–F). The p-tau IHC staining pattern progressively changed from neuritic and dystrophic neurite staining at 3 mpi (data not shown) to both neuritic, dystrophic neurite and cytoplasmic neuronal staining at 6 mpi (Figure 7C). The failure of α-syn mpff-injection to cross-seed tau in WT mice and the absence of p-tau in PBS-injected 5xFAD mice suggest a multi-step process whereby Aβ plaques cause the mislocalization of endogenous mouse α-syn and tau (He et al., 2018; Sadleir et al., 2016) and the injection of α-syn mpffs triggers the accumulation of α-syn pathology, which in turn facilitates cross-seeding of tau.

Figure 7: Brain injections of mpffs in 5xFAD mice leads to accumulations of hyperphosphorylated tau.

IHC was conducted as described in methods on sections from α-syn mpff-injected WT mice (A), PBS-injected 5xFAD (B) and α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice (C). The latter group displays AT8-positive staining in the cytoplasm of neurons (thin arrows) and dystrophic neurites (thick arrows). Scale bar, 100 μm. D) Immunoblots on hippocampus of α-syn mpff-injected WT and 5xFAD mice revealed no change in endogenous mouse tau (K9JA) (E), but a significant increase in p-tau (PHF-1) (F) in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice relative to α-syn mpff-injected WT. A two-tailed t-test was performed to calculate the difference between groups *p<0.05. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m (n=5 mice per group).

AD/PD co-pathology accelerates the development of cognitive and motor deficits and neuron loss

Previous studies have reported a decrease in motor performance and an associated loss of dopaminergic neurons in the SN of WT mice injected in the dorsal striatum with α-syn mpffs (Luk et al., 2012), while other studies have reported mild alterations to cognitive acuity and motor performance in 5xFAD mice relative to WT littermates (Oakley et al., 2006), but the contribution of α-syn pathology to cognitive and motor phenotypes in plaque-bearing 5xFAD mice has yet to be explored.

To address this, we first compared the body weights of WT and 5xFAD mice injected with α-syn mpffs or PBS at 3, 4, 5, and 6 mpi. At the 6 mpi time point, α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice weighed significantly less than the control α-syn mpff-injected WT, PBS-injected WT, or PBS-injected 5xFAD mice (Supplementary Figure 8A). All groups showed similar activity in the open filed regardless of weight differences (Supplementary Figure 8B). α-syn mpff injections into the brains of 5xFAD mice accelerated cognitive decline in the Y-maze as early as 3 mpi and cognitive performance progressively worsened with time (Supplementary figure 8C).

After cognitive performance testing, WT and 5xFAD mice underwent motor behavioral testing using the rotarod. α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice showed gradual worsening of motor performance compared to PBS- and α-syn mpff-injected WT littermates as early as 3 mpi. α-syn. Similar to the Y-maze results, α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD performance in the rotarod test progressively deteriorated with time (Supplementary figure 8D). Consistent with a previous study (O’Leary et al., 2018), PBS-injected 5xFAD mice showed a deficit in motor performance with at 5 mpi and 6 mpi compared to PBS-injected WT mice (Supplementary figure 8D). As a result of Aβ deposition, α-syn accumulation in dystrophic neurites could modify associated synapse dysfunction, including the disruption of circuits implicated in normal motor functions (Tian et al., 2017).

Next, we performed detailed whole-hippocampus quantification of NeuN-stained PBS- and α-syn mpff-injected WT and 5xFAD mice (Figure 8 A–D). Analysis of NeuN staining in hippocampus showed a significant loss of dentate gyrus neurons in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice compared to all other groups (Figure 8 E). CA3 neuron loss was also detected in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice compared to PBS-injected WT and 5xFAD mice (Figure 8 F). Furthermore, hippocampal mossy cell count was significantly decreased in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice compared to PBS-injected WT mice (Figure 8G).

Figure 8: α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice showed significant neuron loss in the hippocampus, VTA and SNpc.

A-D) IHC for NeuN in the mice shown here as described in results. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc analysis were used to analyze the data (E-G). Black scale bar (Large images): 200 μm, black scale bar (small images): 20 μm. H-O) IHC for TH was conducting on SNpc sections from 4.5 mo 6 mpi PBS-injected WT (H, I), α-syn mpff-injected WT (J, K), PBS-injected 5xFAD mice (L, M) and α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD (N, O) mice. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc analysis were used to analyze the data (P, Q). Black scale bar: 1000 μm. *p < 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. (n=4-5 mice per group). R) IF double-labeling was conducted for p-α-syn (red) in surviving dopaminergic neurons (green) using 81A and TH, respectively. White scale bar: 20 μm.

Finally, we assessed the loss of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-positive dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc of these mice We stained sections that captured the whole SN and VTA of mice from all groups (Figure 8H–O). Post-hoc analysis of stereological counts of dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc revealed a significant loss of TH-positive neurons in the SNpc of α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD compared to all groups (Figure 8P). α-syn mpff hippocampal injection in WT mice did not induce SNpc neuronal loss like that seen in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice. Similarly, statistical analysis revealed a significant decrease in TH-positive neurons in the VTA of α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD compared to all groups (Figure 8Q). As aforementioned, the brains of α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice displayed widespread α-syn pathology in regions with known primary connections to the hippocampus, as well as to regions that have secondary and tertiary tethers, including the midbrain and structures contained within, like the SNpc (Figure 2K, 8R).

Discussion

Historically, individual NDDs were considered distinct from one another, but it is now recognized that most NDDs have frequent co-pathologies and are therefore multi-proteinopathies (Bennett et al., 2018; Robinson et al., 2018). Data collected from the CNDR brain bank shows a strong association between cortical α-syn pathology and Aβ plaque burden and positively associates dystrophic neurite α-syn staining with Aβ plaque load in LBD patients with AD co-pathology (Toledo et al., 2016). However, it has been challenging to model the interactions of these pathologies in mice for mechanistic and preclinical therapeutic studies.

Thus, one of the goals of our study was to establish a new transmission model of comorbid AD/PD pathology allowing the dissection of mechanisms by which amyloidogenic proteins could synergistically interact. To accomplish this, we injected α-syn mpffs into the hippocampus and cortex of WT and 5xFAD mice at 1.5 mo, 4 mo, and 9 mo, ages that correspond with stages of Aβ plaque development (He et al., 2018; Oakley et al., 2006). We then extended these studies with similar injections of LB-brain derived pathological α-syn.

First, we examined the effect of Aβ plaques on the seeding and spreading of α-syn following brain injections of α-syn mpffs by quantifying the differences in α-syn pathological burden between 5xFAD and WT in different brain regions. At 3 mpi, no difference in hippocampal α-syn pathology was observed between α-syn mpff-injected WT and 5xFAD mice. However, p-α-syn hippocampal levels persisted at 6 mpi in 5xFAD mice compared to the decrease in p-α-syn pathology seen in WT mice at 6 mpi relative to 3 mpi. We then examined the pattern of p-α-syn transmission throughout 5xFAD and WT brains. As expected, we observed α-syn pathology in brain areas known to directly connect with the hippocampus in both 5xFAD and WT mice (Oh et al., 2014). These regions included the entorhinal and ectorhinal cortices and the contralateral hippocampus. However, the spreading of α-syn pathology in 5xFAD occurred at a faster rate and was more widespread, reaching the prefrontal cortex, motor cortex, striatum, midbrain, and the hindbrain, regions where abundant Aβ plaques are found. Further, p-α-syn burden in these connected regions increased at 6 mpi compared to 3 mpi in 5xFAD mice. Importantly, we observed a similar trend in the APPKI mice which showed a significant acceleration of p-α-syn spreading and an increase in p-α-syn burden in the brain compared to WT mice.

The findings of increased pathological α-syn in 5xFAD mice following intracerebral injection of α-syn mpffs were bolstered by results from 5xFAD mice injected with human LBD brain extracts enriched with pathological α-syn. Previous studies showed that injection of α-syn pffs generated from hpffs and LBD containing brain lysates recruit and template mouse α-syn poorly in mice (Luk et al., 2016; Masuda-Suzukake et al., 2013; Peng et al., 2018b; Sharma et al., 2016). Thus, it is remarkable that we show here a dramatic induction of α-syn pathology in 5xFAD mice following human LB-brain derived pathological α-syn brain injections. No a-syn pathology was observed in WT mice following the same treatment. These results support the view that the Aβ plaque environment facilitates or promotes α-syn aggregation and spread (He et al., 2018). Notably, no differences were noted in α-syn mRNA and protein levels between PBS- and α-syn mpffs-injected WT and 5xFAD mice, ruling out the possibility that the increase in pathological α-syn in 5xFAD relative to WT mice was caused by alterations in α-syn mRNA transcription or protein translation.

Since prior studies showed that the autophagy-lysosome pathway mediates intraneuronal clearance of accumulated α-syn (Cuervo et al., 2004), we explored defective protein clearance as a possible explanation for increased pathological α-syn in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD compared with α-syn mpff-injected WT mice. Indeed, the amount of α-syn pathology in WT mice decreased at 6 mpi relative to 3 mpi levels, but increased in the 5xFAD mice over the same time period since α-syn aggregates have been shown to be resistant to degradation and to impair autophagy, leading to neuron loss (Luk et al., 2009; Luna et al., 2018; Tanik et al., 2013). Our data also point to an alteration of the ubiquitin-proteasome complex marked by the increase in ubiquitinated proteins that are K63 poly-ubiquitinated under co-pathology conditions. K63 poly-ubiquitination has been shown to promote protein degredation through autophagy pathway which was impaired in co-pathology conditions marked by the increase in LC3-2 and p62 levels (Cohen-Kaplan et al., 2016; Shaid et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2008). Importantly, we show that the UPR is compromised in α-syn mpffs-injected 5xFAD mice implicating Aβ-plaques and α-syn in the clearance of misfolded proteins, rendering neurons more vulnerable to protein accumulation, aggregation and death. Other studies have shown that alterations in the activity and capacity of the proteostasis network are a main feature of AD (Viana et al., 2012). Indeed, Aβ plaques are involved in the activation of the UPR which plays a role in the progression of AD (Alberdi et al., 2013; Gerakis and Hetz, 2018; Viana et al., 2012). ER stress elevation has been previously reported in APP overexpressing mice pointing to transgene overexpression or Aβ plaque accumulation as inducers of such stress (Hashimoto et al., 2018). We beleive that our results in 5xFAD coupled with previsouly published work by Sadleir et al. (2018), point to Aβ plaque burden as inducer of ER stress and not transgene overexpression. The observation that injection of α-syn mpffs induced greater proteostasis impairment in 5xFAD than in WT mice might suggest that the Aβ plaque environment compromise protein clearance, resulting in the enhancement of α-syn seeding and spreading.

While previous studies have shown that Aβ enhances tau accumulation by destabilizing microtubules leading to tau mislocalization in dystrophic neurites (He et al., 2018; Sadleir et al., 2016), aggregated α-syn in dystrophic neurites has also been reported in Aβ plaque-bearing AD brains (Hamilton, 2000). Thus, it is notable that α-syn also spontaneously pools and concentrates in dystrophic neurites around Aβ plaques. Moreover, old PBS-injected 5xFAD and APPKI mice exhibited some p-α-syn 81A-positive pathology in dystrophic neurites, suggesting that the Aβ plaque environment facilitates the initiation and transformation of α-syn from its native form to a misfolded form in dystrophic neurites. Importantly, pathological α-syn was not detected by Syn 506, a MAb to misfolded α-syn, in PBS-injected 5xFAD mice suggesting that α-syn is not misfolded in PBS-injected 5xFAD mice (Luk et al., 2012). On the other hand, α-syn mpffs and human pathological α-syn-containing brain lysates injected into 5xFAD mice showed Syn 506-positive α-syn pathology. Finally, although monomeric α-syn injection did not induce α-syn pathology in WT mice, an increase in p-α-syn pathology and the appearance of Syn 506-positive α-syn pathology was detected in α-syn monomer-injected 5xFAD mice. These findings provide further evidence that Aβ plaques create a favorable environment that promotes and enhances seeding and spreading of α-syn through the establishment of a dynamic pre-misfolded pool of α-syn in dystrophic neurites. Importantly, we show through control experiments that the interaction of Aβ plaques with α-syn is synergistic and specific.

It is well known that NDD proteins adopt β-pleated sheet conformations that can crossseed, template, and promote the fibrilization of one another (Giasson et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2013; Mandal et al., 2006; Ono et al., 2012; Tsigelny et al., 2008). Since the effects of the surrounding environment on amyloidogenesis is yet to be elucidated (Peng et al., 2018a; Peng et al., 2018b), we assessed the potential differences in the activity of α-syn pathology generated in WT and 5xFAD mice following α-syn mpff injections. We found that neurons transduced with misfolded α-syn obtained from α-syn mpff-injected plaque-bearing 5xFAD mouse brain exhibit more robust α-syn pathology than neurons transduced with pathological α-syn generated from α-syn mpff-injected WT mouse brain. Through control experiments, we showed that this increased α-syn activity is not due to the presence of pathological Aβ in the 5xFAD brain lysates, but instead it is likely a result of the pathological α-syn present in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD brain lysates. Thus, these in-vitro data point to a possible mechanism in which the Aβ plaque environment induces a new α-syn strain that is more potent and capable of seeding and templating pathology than the pathological α-syn that matures in the Aβ plaque-free cellular environment of a WT mouse brain. These observations together with previous published work illustrate the need for studies to dissect the mechanism behind cross-seeding.

Our work, alongside other studies, suggests that α-syn and Aβ are capable of interacting directly and indirectly in the brain (Chia et al., 2017; Mandal et al., 2006; Masliah et al., 2001; Ono et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2017; Tsigelny et al., 2008). In-vitro studies have shown that α-syn interacts directly with Aβ, inducing α-syn oligomerization (Masliah et al., 2001; Ono et al., 2012; Tsigelny et al., 2008). Indirect α-syn/Aβ interaction has been reported as well (Marsh and Blurton-Jones, 2012). We observed increased Aβ plaque burden in the brains of α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice compared to PBS-injected mice. Biochemical analysis showed that this was associated with a significant increase in gamma-secretase proteins, nicastrin and PS2, which are known to potentiate cleavage of APP to Aβ. Increased synaptic α-syn has been shown to augment APP cleavage by secretases, contributing to Aβ plaque formation (Roberts et al., 2017). Importantly, we found a significant decrease in ADAM 10 levels, characterized by its α-secretase activity, in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice compared to PBS-injected mice. Our results show that upon α-syn mpffs injection, the APP processing machinery favors the amyloidogenic pathway via a decrease in α-secretase levels coupled to an increase in gamma-secretases leading to Aβ plaque formation. As a control experiment, we show that α-syn mpff injection did not induce an increase in human APP mRNA expression levels in the brain. This finding was not observed in two other recent studies (Bachhuber et al., 2015; Khan et al., 2018), which may in part be a consequence of the different mouse models used in the studies that were shown to have a different phenotype compared to 5xFAD mice (Mucke et al., 2000; Radde et al., 2006). These previous findings were derived from bigenic mice which might reflect the interaction of the transgenes rather than the effect of a single protein on the other (Clinton et al., 2010; Masliah et al., 2001). Moreover, Bacchuber et al., 2015 also show no significant differences in insoluble Aβ levels which implies that the differences observed were on soluble Aβ levels. Similarly, α-syn mpff injection in 5xFAD did not affect insoluble Aβ levels (data not shown). Finally, we showed impaired protein clearance under α-syn/Aβ pathology in 5xFAD. Increased co-pathology burden might also contribute to increased Aβ plaque burden by further blocking the clearance mechanism.

Another striking observation in our study was the accumulation of p-tau positive pathology in α-syn mpff-injected 5xFAD mice. This finding strongly corroborates the previously reported synergistic relationship between tau and α-syn (Badiola et al., 2011; Clinton et al., 2010; Gerson et al., 2018; Giasson et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2013; Sengupta et al., 2015). Importantly, p-tau was not seen in brain sections of PBS-injected 5xFAD mice or α-syn mpff-injected WT mice. We suggest a potential two-step process that accounts for this α-syn cross-seeding of tau. First, Aβ plaques induce pooling of α-syn within the synaptic terminals which is “primed” to cross-seed other aggregation prone proteins like tau (Giasson et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2013). Second, since Aβ plaques were shown to cause the disassembly of microtubules in dystrophic processes, thereby releasing tau proteins that are bound to microtubules (Sadleir et al., 2016), these pools of mislocalized endogenous α-syn and tau readily facilitate tau/α-syn interactions. However, since injections of AD brain-derived pathological material into the hippocampus of 5xFAD mice did not induce α-syn pathology (He et al., 2018), pathological α-syn may be the major driver of tau cross-seeding in the 5xFAD plaque-rich brain environment.

Co-pathology in the brains of AD and PD patients is a likely reason for overlapping symptoms seen in patients (Bennett et al., 2018; Robinson et al., 2018). Importantly, studies have shown that co-pathology patients exhibit a more rapid decline in cognitive and motor performance and have shortened lifespans (Hansen et al., 1990; Irwin et al., 2017). Here, we provide experimental evidence of the effect of AD/PD co-pathology on cognitive and motor performance in mice. While PBS-injected 5xFAD mice showed mild cognitive and motor performance decline, infusion of α-syn mpffs in the brain of 5xFAD mice exacerbated behavioral impairments, leading to faster rates of cognitive and motor decline.

A recent study has shown hippocampal neuronal loss in WT mice injected with α-syn mpffs (Luna et al., 2018). While we did not observe significant neuron loss in the hippocampus of α-syn mpff-injected WT mice, our results depict this trend. In accordance with previous work, we show that α-syn and Aβ have synergistic toxicity (Clinton et al., 2010; Masliah et al., 2001; Spencer et al., 2016), as AD/PD co-pathology exacerbated neuronal loss in 5xFAD mice injected with α-syn mpffs, an observation not seen in PBS-injected 5xFAD mice. Finally, we found that hippocampal α-syn mpff injections into 5xFAD mice led to the spread of α-syn pathology to the midbrain through secondary and tertiary connected structures, a phenomenon that did not occur in the absence of Aβ plaques.

Thus, the model system described here will enable the investigation of mechanisms linking Aβ plaques and α-syn pathology or other co-pathologies such as tau in NDDs. This co-pathology model system will be extremely useful in testing the effect of combined therapies such as immunotherapy that target more than one disease protein, an emerging concept for new AD therapies (Perry et al., 2015).

STAR METHODS

Lead Contact and Materials Availability

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Dr. Virginia M.Y. Lee (vmylee@upenn.edu). This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Mice

5xFAD Tg mice (Tg6799 line) (Oakley et al., 2006) overexpress known familial AD (FAD) mutations in APP (K670N/M671L [isoform 770] + I716V + V717I) and PS1 (M146L + L286V) genes, under the control of the Thy1 promoter. 5xFAD mice were generated in our Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research (CNDR) by crossing male Tg mice with female B6/SJL F1 mice. Original 5xFAD and all B6/SJL breeders were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (5xFAD : Stock No: 034840-JAX; B6/SJL: Stock No:100012). Wild-type control mice used in this study were 5xFAD littermates. Knock-in mice that harbor the Swedish (KM670/671NL) and Beyreuther/Iberian (I716F) mutations in the APP gene [APPNL-F/NL-F KI mice] (Saito et al., 2014) were obtained from T. Saido (RIKEN Brain Science Institute, Japan) and bred with C57BL/6 F1 female mice purchased from Charles River (Stock No: 27). Tg2576 mice, overexpressing the human APP double mutation K670N/M671L (isoform 695), under the control of the hamster prion protein promoter (Hsiao et al., 1996), were bred with B6/SJL F1 female mice. For all studies, both male and female mice were used and they were allocated randomly between injection groups, while correcting for sex and body weight. Experimenters were blinded to the genotype/treatment of each mouse during data collection and identities were decoded later after analysis, using identification numbering based on toe tattooing. Mice were housed in a temperature-controlled room under a 12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. All procedures were performed in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals. Studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania.

Human patient sample studies

Detailed clinical characteristics (disease duration, age at death, site of onset, etc.) were ascertained from an integrated neurodegenerative disease database (INDD) in CNDR at the University of Pennsylvania. Frozen postmortem brain samples were patient brain donors who underwent autopsy at CNDR between 1992 and 2016. More details on these patients are in Supplementary Table 1. Mean age was similar among the different groups (PD: 76 ±0.9 years, PDD: 77 ±0.5 years; DLB: 74 ±1.5 years) (Supplementary Table 1). Patients samples used in this study were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) Cases with primary clinicopathological diagnosis PD, PDD and DLB and 2) Cases with semiquantitative scores by immunohistochemistry for pathological tau, thioflavin S and α-syn. For human brain analysis, α-syn scores from PD, PDD, DLB patients were pooled and sorted according to Aβ plaque load (Montine et al., 2012). Each region was assigned a semiquantitative score i.e. 0 (none), 0.5 (rare), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate) or 3 (severe) for individual lesions (tau, Aβ and α-synuclein). We then group patients according to Aβ plaque load according to the semiquantitative scoring as “No plaques” (0 score), “Low plaque load” (0.5-1 score) and “High plaque load” (2-3 score). Written informed consent for autopsy and analysis of tissue sample data was obtained for all patients as described (Toledo et al., 2016). Samples were obtained with ethics committee approval and prior as well as current neuropathology assessments were conducted as described (Robinson et al., 2018; Toledo et al., 2016).

Primary Hippocampal Neuron Cultures

Primary hippocampal were prepared as previously described (Volpicelli-Daley et al., 2014a) from embryonic day (E) 16-18 CD1 embryos. Dissociated hippocampal were plated at 100,000 cells/well (24-well plate) in neuron media (Neurobasal medium (ThermoFisher 21103049) supplemented with B27 (ThermoFisher 17504044), 2 mM GlutaMax (ThermoFisher 35050061), and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (ThermoFisher 15140122).

Method details

Behavior

Open field: Locomotion and anxiety-related behavior were tested in an open field arena (36 χ 36 cm) (San Diego Instruments Photobeam Activity System) with clear Plexiglass walls and a white floor as described (He et al., 2018). The total number of center, peripheral, and vertical beam breaks was automatically recorded by a tracking software as a direct measure of locomotion and activity (He et al., 2018).

Y-maze: To measure short-term working memory, mice were tested for spontaneous alternation behavior (SAB) in a Y-shaped maze (San Diego Instruments) using a standard protocol as described (He et al., 2018). SAB during a 5 min test period was calculated as the proportion of alternations (an arm choice differing from the previous two choices) to the total number of alternation opportunities (total arm entries).

Rotarod: To assess motor learning, coordination, and balance, mice were tested on the Rotarod apparatus (MED-Associates) as described (He et al., 2018). Each mouse received two consecutive trials and the mean latency to fall was used in the final analysis.

Mouse α-Syn pffs

Purification of recombinant mouse α-synuclein and generation of α-synuclein PFFs was conducted as described elsewhere (Luk et al., 2012; Luk et al., 2009; Volpicelli-Daley et al., 2014a; Volpicelli-Daley et al., 2014b; Volpicelli-Daley et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2019). The pRK172 plasmid containing the gene of interest was transformed into BL21 (DE3) RIL-competent E. coli (Agilent Technologies Cat#230245). A single colony from this transformation was expanded in Terrific Broth (12 g/L of Bacto-tryptone, 24 g/L of yeast extract 4% (vol/vol) glycerol, 17 mM KH2PO4 and 72 mM K2HPO4) with ampicillin. Bacterial pellets from the growth were sonicated and sample was boiled to precipitate undesired proteins (this boiling step was skipped for GFP-tagged α-synuclein). The supernatant was dialyzed with 10 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA overnight. Protein was filtered with a 0.22 μm filter and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter units (Millipore Sigma Cat#UFC901008). Protein was then loaded onto a Superdex 200 column and 1 mL fractions were collected. Fractions were run on SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue to select fractions that were highly enriched in α-synuclein. These fractions were combined and dialyzed in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA overnight. Dialyzed fractions were applied to the MonoQ column (GE Health, HiTrap Q HP 645932) and run using a linear gradient from 25 mM NaCl to 1 M NaCl. Collected fractions were run on SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. Fractions that were highly enriched in α-synuclein were collected and dialyzed into DPBS. Protein was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter and concentrated to 5 mg/mL (α-synuclein) with Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filters. Monomer was aliquoted and frozen at −80°C. For preparation of α-synuclein PFFs, α-synuclein monomer was shaken at 1,000 rpm for 7 days. Conversion to PFFs was validated by sedimentation at 100,000 x g for 60 minutes and by thioflavin S staining.

Biochemical sequential extraction of α-syn from human brain

Samples from the frontal cortex were dissected from human patient brains and stored at −80°C before extraction. Brain slabs were thawed on ice and grey matter was separated from white matter. In order to isolate pathological insoluble α-syn from human brain samples, sequential extractions were performed as described (Peng et al., 2018a). Briefly, tissue from each patient was individually homogenized in 9 volumes per gram tissue with cold high-salt (RAB) buffer (0.75 M NaCl, 100 mM Tris, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 0.02 M NaF, 2 mM DTT, containing a protease inhibitor cocktail, phosphatase inhibitors and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) at pH 7.4), sonicated and designated as homogenate. The homogenates were centrifuged at 100,000xg-for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was saved as the high-salt fraction, while the pellet was resuspended and sonicated in high-salt RAB buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail, phosphatase inhibitors and PMSF, and centrifuged again at 100,000xg-for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and kept as the Triton-soluble fraction. This step was repeated one more time and the resulting pellet was resuspended in high-salt RAB buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 plus 30% sucrose and centrifuged at 100,000xg-for 30 min at 4 °C to eliminate myelin remnants. The resultant supernatant was discarded and the samples were cleared of any remaining myelin. The pellets were then resuspended in high-salt RAB buffer containing 1% sarkosyl with the protease inhibitor cocktail, phosphatase inhibitors and PMSF, pH 7.4. The samples were then rotated at room temperature for 1 h before being centrifuged again at 100,000xg for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was saved as the sarkosyl-soluble fraction, and the pellet was washed once with PBS and then resuspended in PBS at one-fourth of the initial volume and sonicated and termed as sarkosyl-insoluble fraction.

ELISA

A 384 well maxisorp clear plate (NUNC) was coated with 30 μL per well (100 ng) of Mab 9027 in Takeda coating buffer, then plate was spun at 1000xg for 1 min and incubated overnight at 4°C. The plate was washed 4x with PBST (PBS with 0.05% Tween) and blocked using Block Ace blocking solution (95 μL per well) (AbD Serotec) overnight at 4°C. To measure the amounts of α-syn in the insoluble fraction of human and mouse brain, samples were sonicated first and diluted in Buffer C. Serial dilutions were added to each well (30 μL per well) and incubated overnight at 4°C. Serial dilutions of human and mouse wild-type α-syn preformed fibrils and α-syn monomer were used as a loading standard to measure the amount of insoluble α-syn in the pelleted fractions. The plate was washed 4x with PBST and 30 μL of HuA (1:10,000) in Buffer C was added to each well and the plate was incubated for 4 h at 37°C. After washing with PBST (4x), 1:10,000 diluted goat-anti-rabbit IgG-HRP conjugate (Cell Signaling Technology) was added to the plate and the plate was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Following a PBST wash (4x), the plate was developed for 10-15 minutes using 30 μL per well of 1-Step Ultra TMB-ELISA Substrate Solution (Fischer) (warmed to room temperature for 1 h), the reaction was quenched using 10% phosphoric acid (30uL per well). Plates were read on 384-450nm on the Spectramax plate reader.

RNA analysis

Mouse hippocampal brain tissue was collected and frozen from PBS or α-syn mpffs injected-WT and 5xFAD mice. RNA was isolated with TRIzol (ThermoFisher) and the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer instructions. 0.5 μg of RNA per sample was converted to cDNA using the Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer instructions. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed with the ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher) using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (ThermoFisher) and 2 chosen TaqMan Gene Expression Assays: Human APP was measured using Hs0016908_m1 (ThermoFisher) and mouse MAP2 was measured using Mm00485236_m1 (ThermoFisher) as the endogenous control. Brain derived cDNA and primers targeting mouse α-Syn (see table) were used in Syber Green (Thermo Fisher) Real Time PCR reactions monitored by a 7500 Fast Real Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Each reaction was performed in triplicate. For normalization, MAP2 levels were used as an internal reference and mRNA levels relative to PBS CTRL were calculated according to the 2-DDCt method.

α-synuclein mpffs Treatments

Primary Neurons

For treatment of neurons, insoluble α-syn extracted from α-syn mpffs injected WT and 5xFAD and PBS-injected 5xFAD mice were diluted with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS, Corning Cat#21-031-CV). Samples were sonicated on high for 10 cycles of 30 seconds on, 30 seconds off (Diagenode Biorupter UCD-300 bath sonicator). Samples were then diluted in neuron media added to neuron cultures at 2ng/well.

Stereotaxic injections

Mice were deeply anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine-acepromazine and immobilized in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, USA) as described (Guo et al., 2013; Luk et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2018a). Briefly, all mice were aseptically injected unilaterally at a rate of 0.4 μl/min using a Hamilton syringe with either human α-syn brain extracts (22 ng α-syn/μl; 55 ng α-syn/site; see Supplementary Table 2), synthetic α-syn mpffs (2 μg α-syn/μl; 5 μg α-syn/site) or PBS into the right dorsal hippocampus followed by the overlying cortex as the needle was withdrawn (bregma: −2.5 mm; lateral: +2 mm; depth: −2.4 mm and −1.4 mm from the skull).

Tissue processing

After in vivo incubation at designated time points, mice were anesthetized and then transcardially perfused with cold PBS containing heparin (1000: USP per 1ml) using a (1:100) dilution. Brain and spinal cord were dissected and fixed overnight in 70% ethanol in 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, for histopathology, or were first snap frozen on dry ice and then stored at −80 °C for biochemistry as described (Peng et al., 2018a).

Histopathological analysis and immunofluorescent labelling

Brains from mice or human tissue that had been fixed in 70% ethanol in 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, were subsequently processed into paraffin embedded blocks, and sectioned at 6 μm sections. For immunohistochemistry (IHC) or immunofluorescence (IF) experiments, every 20th 6 μm section was selected to ensure the representation of the whole brain unless stated otherwise.

After antigen retrieval, slides were incubated in 5% hydrogen peroxide in methanol to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Slides were washed for 10 min in running tap water, 5 min in 0.1 M Tris, then blocked in 0.1 M Tris/2% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Slides were incubated in primary antibodies overnight.

The following primary antibodies were used. For pathologically-phosphorylated α-synuclein, pS129 α-synuclein (81A, CNDR, 1:20,000) or MJFR13 (Abcam, 1:10,000) with microwave antigen retrieval. Another primary antibody recognizing pathological α-syn (506, CNDR, 1:10,000) was also used. An antibody recognizing total α-syn (Syn9027, CNDR, 1:2,000) and total tau (K9JA, 1:200) were used to characterize α-synuclein and tau distribution. Pathological phosphorylated tau was stained using AT8 (Thermo, 1:10,000) on mouse sections or PHF-1 (1:5,000) on human section while staining of amyloid beta plaques was done using Nab228 (1:20,000) or H31L21 (Thermo, 1:10,000). Anti-APP was used to stain dystrophic neurites (Millipore, 1:5,000). To stain neurons, anti-NeuN was used at 1:500 (Millipore). Markers for protein clearance and degradation were also used p62 (Abnova, 1:1000) and ubiquitin (1:5,000). To stain midbrain dopaminergic neurons, anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (Millipore) was used at 1:5000 with formic acid antigen retrieval. Primary antibody was rinsed off with 0.1 M Tris for 5 min, then incubated with goat anti-rabbit (Vector BA-1000) or horse anti-mouse (Vector BA2000) biotinylated IgG in 0.1 M Tris/2% FBS 1:1000 for 1 h. Biotinylated antibody was rinsed off with 0.1 M Tris for 5 min, then incubated with avidin-biotin solution (Vector PK-6100) for 1 h. Slides were then rinsed for 5 min with 0.1 M Tris, then developed with ImmPACT DAB peroxidase substrate (Vector SK-4105) and counterstained briefly with hematoxylin.

IHC sections were scanned with a 3DHISTECH Laminar Scanner (Perkin Elmer) and quantification of the percentage area occupied by different IHC labeled pathologies were performed with HALO software (Indica Labs) as described (Guo et al., 2013; Irwin et al., 2017; Luk et al., 2016; Luk et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2018a). For NeuN and TH staining, every 10th section was selected for staining and quantification. The quantification of NeuN in the hippocampus was done through manual blinded counting by 2 observers. Results were then presented as number of cells per mm2. For substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and ventral tegmental area (VTA) TH counts, anti-TH IHC was conducted and stereological sampling was performed as described (Luk et al., 2012). Following delineation of the SNc at 3.2x objective using HALO, counting was performed at 40x objective. Only intact neurons with visible nuclei were included.

For IF labelling, sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000, Invitrogen, USA). After 1 h incubation with secondary antibodies, sections were washed and immersed in 0.3% Sudan Black in 70% ethanol for 1 min to reduce background lipofuscin autofluorescence in the human brain sections. After thorough washing in 0.1M Tris (pH=7.6), slides were mounted in medium containing nuclei-staining 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Thermo scientific, USA). Slides were visualized by using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 epifluorescent microscope at x40 magnification.

Immunocytochemistry

Primary neurons were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, 4% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline and washed five times in PBS. Immunostaining of cultures was carried out as described previously (Volpicelli-Daley et al., 2014a). Cells were permeabilized in 3% BSA + 0.3% TX-100 in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. After a PBS wash, cells were blocked for 50 min with 3% BSA in PBS prior to incubation with primary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies used were targeting pS129 α-synuclein (81A, CNDR, 1:15000) and MAP2 (17028, CNDR, 1:5000). Cells were washed 5x with PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. After 5x wash with PBS, cells were incubated in DAPI (ThermoFisher Cat#D21490, 1:10,000) in PBS. Cover slips were scanned with a 3DHISTECH Laminar Scanner (Perkin Elmer) and quantification of the percentage area occupied by different IHC labeled pathologies were performed with HALO software (Indica Labs) as described (Guo et al., 2013; Irwin et al., 2017; Luk et al., 2016; Luk et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2018a). All quantification was optimized and applied equally across all conditions.

Biochemical sequential extraction from mouse brain

Different regions, including the hippocampus, overlying cortex, and entorhinal and ectorhinal cortices, were dissected separately and stored at −80 °C before extraction. Tissue from each mouse was thawed, individually homogenized in 200 μl of cold high-salt RAB buffer, sonicated, and centrifuged at 100,000xg for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was designated as high-salt soluble fraction (HS). The pellet was resuspended and re-sonicated in 100 μl high-salt RAB buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 and centrifuged again at 45,000xg for 30 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatants was designated as the ‘Triton-soluble’ fraction (Tx), and the pellets were resuspended and resonicated in 100 μl of sterile distilled PBS (Pellet).

Immunoblotting

Protein concentrations for all fractions i.e. HS and Pellet were determined using the BCA assay (Fisher Cat#23223 and 23224) using bovine serum albumin as a standard (Thermo Fisher Cat#23210). Samples were normalized for total protein content and prepared for Western blot analysis. Samples (20 μg total protein) were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (4-20% gradient) and transferred onto 0.22 μm nitrocellulose membranes. For APP processing mechanism, 16.5% Tris Tricine gels were used (Biorad). Blots were blocked in 5% non-fat milk in TBS, probed with (Syn9027, CNDR, 1:20,000), pS129 α-syn (Abcam, 1:1000), K9JA (DAKO: 1:5000), PHF-1 (1:1000), LC3 (MBL , 1:500), p62 (Abnova , 1:1000), Ubiquitin (1B4; 1:1000), K48 (Cell Signaling, 1:1000), K63 (Cell Signaling, 1:1000), BIP (Cell Signaling, 1:1000), eiF2α (Cell Signaling, 1:1000), p-eiF2α (Cell Signaling, 1:1000), Nicastrin (Cell Signaling:1000), BACE-1 (Abcam, 1:1000), ADAM10 (Calbiochem, 1:1000), Psen1 (In-house, 1:500), Psen2 (In-house, 1:500) and 5685-APPCTF (In-house 1:500) incubated overnight at 4 °C. The blots were further incubated with IRDye-labeled secondary antibodies (IRDye 800 (Li-cor 925-32210) or IRDye 680 (Li-cor 925-68071)) for 1 h and scanned using Li-cor Odyssey Imaging System. After target antigens were detected, the optical densities (ODs) were measured with Image Studio software (Li-Cor Biosciences). Proteins were normalized to beta-tubulin (1:1000, Abcam)), used as a loading control.

Quantitation and Statistical Analysis

The number of samples or animals analyzed in each experiment, the statistical analysis performed, as well as the p values for all results are reported in the figure legends. For all in vivo experiments, the reported “n” represents the number of animals. The data was first tested for normality using D’agostino-pearson test. For comparison between two groups, a t-test was applied. A one-way ANOVA was applied was used when multiple groups were compared with one variable followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. If the data did not pass normality, a Kruskal-Wallis test was used followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. A two-way ANOVA was applied to compare values between the PBS and mpff-injected groups of mice followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Spearman’s correlation was used on the data presented followed by partial correlation accounting for the 3rd variable. Statistical analysis was performed with Prism V6.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., USA). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical tests were two-tailed and the level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Data and Code Availability

Primary data used to generate the figures in this study are available on Mendeley (Bassil, Fares (2019), “Raw data for Amyloid-Beta (Aβ) Plaques Promote Seeding and Spreading of Alpha-Synuclein and Tau in a Mouse Model of Lewy Body Disorders with Aβ Pathology”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/2gmf3r2874.1)

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

α-syn burden is associated with Aβ plaque load in the cortex of LBD patients.

Aβ plaques potentiate α-syn spreading in 5xFAD mice.

Aβ plaques establish a dynamic pre-misfolded pool of α-syn in dystrophic neurites.

Aβ/α-syn co-pathology induce neurodegeneration and behavioral deficits.

Acknowledgments

We thank S-J. Kim, J. McBride, M. Olufemi, R. Gathagan, S. Leight, J. Robinson, C. Casalnova and T. Schuck for technical assistance. We thank C. Peng for providing the human derived LB material used in this study. We thank Dr. S. Porta, Dr. J. Toledo, Dr. E. Lee, Dr. A. Caputo and Dr. Z. He for their expert opinion and help through the revision process. We thank S. Xie and J. Toledo for help with statistical analyses. This work was supported by NIH/NIA U19 Center grant, the Jeff and Anne Keefer Fund and the Neurodegenerative Disease Research Fund.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- Alberdi E, Wyssenbach A, Alberdi M, Sanchez-Gomez MV, Cavaliere F, Rodriguez JJ, Verkhratsky A, and Matute C (2013). Ca(2+) -dependent endoplasmic reticulum stress correlates with astrogliosis in oligomeric amyloid beta-treated astrocytes and in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging cell 12, 292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachhuber T, Katzmarski N, McCarter JF, Loreth D, Tahirovic S, Kamp F, Abou-Ajram C, Nuscher B, Serrano-Pozo A, Muller A, et al. (2015). Inhibition of amyloid-beta plaque formation by alpha-synuclein. Nature medicine 21, 802–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badiola N, de Oliveira RM, Herrera F, Guardia-Laguarta C, Goncalves SA, Pera M, Suarez-Calvet M, Clarimon J, Outeiro TF, and Lleo A (2011). Tau enhances alpha-synuclein aggregation and toxicity in cellular models of synucleinopathy. PloS one 6, e26609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bate C, Gentleman S, and Williams A (2010). alpha-synuclein induced synapse damage is enhanced by amyloid-beta1-42. Molecular neurodegeneration 5, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, and Schneider JA (2018). Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 64, S161–S189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RE, DeVos SL, Dujardin S, Corjuc B, Gor R, Gonzalez J, Roe AD, Frosch MP, Pitstick R, Carlson GA, et al. (2017). Enhanced Tau Aggregation in the Presence of Amyloid beta. The American journal of pathology 187, 1601–1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron C, and Pollanen M (1989). Lewy bodies in Alzheimer disease-one or two diseases? Alzheimer disease and associated disorders 3, 197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia S, Flagmeier P, Habchi J, Lattanzi V, Linse S, Dobson CM, Knowles TPJ, and Vendruscolo M (2017). Monomeric and fibrillar alpha-synuclein exert opposite effects on the catalytic cycle that promotes the proliferation of Abeta42 aggregates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114, 8005–8010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinton LK, Blurton-Jones M, Myczek K, Trojanowski JQ, and LaFerla FM (2010). Synergistic Interactions between Abeta, tau, and alpha-synuclein: acceleration of neuropathology and cognitive decline. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 30, 7281–7289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Kaplan V, Ciechanover A, and Livneh I (2016). p62 at the crossroad of the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. Oncotarget 7, 83833–83834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colom-Cadena M, Gelpi E, Charif S, Belbin O, Blesa R, Marti MJ, Clarimon J, and Lleo A (2013). Confluence of alpha-synuclein, tau, and beta-amyloid pathologies in dementia with Lewy bodies. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology 72, 1203–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM, Stefanis L, Fredenburg R, Lansbury PT, and Sulzer D (2004). Impaired degradation of mutant alpha-synuclein by chaperone-mediated autophagy. Science 305, 1292–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]