Abstract

Search for a definitive cure for neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s disease (PD) has met with little success. Mitochondrial dysfunction and elevated oxidative stress precede characteristic loss of dopamine-producing neurons from the midbrain in PD. The majority of PD cases are classified as sporadic (sPD) with an unknown etiology, whereas mutations in a handful of genes cause monogenic form called familial (fPD). Both sPD and fPD is characterized by proteinopathy and mitochondrial dysfunction leading to increased oxidative stress. These pathophysiological mechanisms create a vicious cycle feeding into each other, ultimately tipping the neurons to its demise. Effect of iron accumulation and dopamine oxidation adds an additional dimension to mitochondrial oxidative stress and apoptotic pathways affected. Nrf2 is a redox-sensitive transcription factor which regulates basal as well as inducible expression of antioxidant enzymes and proteins involved in xenobiotic detoxicfication. Recent advances, however, shows a multifacted role for Nrf2 in the regulation of genes connected with inflammatory response, metabolic pathways, protein homeostasis, iron management, and mitochondrial bioenergetics. Here we review the role of mitochondria and oxidative stress in the PD etiology and the potential crosstalk between Nrf2 signaling and mitochondrial function in PD. We also make a case for the development of therapeutics that safely activates Nrf2 pathway in halting the progression of neurodegeneration in PD patients.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Nrf2, mitochondria, ferroptosis, metabolomics, neurodegeneration

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the most prevalent neurodegenerative disease affecting the motor system. The worldwide incident of PD varies from 5 to > 35 people per 100,000 people, reflecting differences in demographics and study methods. Age is the most crucial risk factor for PD, with an estimated global prevalence of 0.3%, which sharply increases to 3% in people who are 80 years and older. PD is more prevalent in men, shows racial differences, and is affected by environmental factors, such as exposure to pesticides and traumatic brain injury (Poewe et al., 2017).

The neuropathology of PD is characterized by the loss of dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra (SN) region of the brain and the presence of intraneuronal fibrillar deposits of α-synuclein, called Lewy bodies or Lewy neurites. The clinical presentation includes resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability often accompanied by non-motor symptoms, such as cognitive impairment, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Patients may varyingly exhibit abnormal sleep, olfaction, and bowel movements. Studies that conflated incidents of encephalitis with PD, investigations into 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced Parkinsonism, and the lack of concordance in monozygotic twin studies led to the hypothesis that attributed PD to environmental origins, which is known as sporadic PD (sPD). About 15% of the disease cases are inherited through mutations and classified as familial or genetic (fPD) [Suggested review (Poewe et al., 2017)].

The investigations of fPD gene products have shed considerable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the etiology of the disease. To date, mutations in > 20 genes have been identified as causing PD (Del Rey et al., 2018; Trinh and Farrer, 2013). Genome-wide association studies have confirmed that some of these genes and pathways involved (proteinopathy, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and abnormal calcium handling) in fPD are also compromised in sPD (Poewe et al., 2017). Hence, notwithstanding heterogeneity of the clinical presentation or underpinning genetics of the disease, the different forms of PD share common pathological and molecular processes, especially concerning mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress.

Recent decades have seen tremendous advances in our understanding of the disease mechanisms and the available care for PD patients. Although PD-related care can improve the quality of life of a patient for a few years with symptomatic treatments, unfortunately, none of the existing therapies can halt progressive neurodegeneration and promote an eventual cure. Several studies have described a key role for mitochondria in facilitating the well-being of DA neurons in healthy individuals, and when the mitochondria are compromised becomes an underlying factor in driving the PD-related neurodegeneration. In this review, we will discuss the role of mitochondria in sPD or fPD and the way in which the nuclear erythroid-2 related factor 2 - antioxidant response element (Nrf2-ARE) signaling impacts mitochondrial function in PD. We will also summarize the recent advances in translational approaches exploiting the inducible expression of Nrf2 to mitigate neurodegeneration in PD.

2. Oxidative stress and PD

Oxidative stress refers to increased generation and accumulation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS, respectively), both of which possess the capabilities to oxidize cellular macromolecules, which eventually disrupts cellular function. In general, oxidative stress is the result of an imbalance in the rates of oxidative species production and rates of removal of these species by cellular antioxidant factors. The fact that oxidative-free radicals are the inevitable byproduct of cellular metabolism indicates that a certain amount of ROS is necessary for cell survival via regulation of various physiological processes ranging from cell propagation to apoptosis. Typically, the ROS arsenal consists of hydroxyl radicals (•OH), superoxide anions (O2•−), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in addition to the RNS species, which includes nitric oxide free radical (NO•) and its derivative, the peroxynitrite (ONOO−) anion. On the other hand, cellular antioxidant defense mechanisms include antioxidant proteins, such as glutathione (GSH), α-tocopherol, ascorbic acid, and oxygen radical scavenging enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, peroxidase, and thioredoxins. Usually, cellular ROS levels are tightly controlled; however, under pathological conditions, ROS levels overwhelm cellular antioxidant levels and impart oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA that could ultimately lead to cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, and carcinogenesis. There are several cellular sources of ROS. Among the notable ones are the mitochondria, cytosol, peroxisomes, endoplasmic reticulum, plasma membrane, and lysosomes (For more information on cellular sources of ROS please consult the review article, (Di Meo et al., 2016)).

Multiple lines of evidence have implicated oxidative stress in the pathology of various cardiovascular disease (Kattoor et al., 2017), diabetes (Sifuentes-Franco et al., 2017), rheumatoid arthritis (Lugrin et al., 2014), cancer (Lee et al., 2017) and neurodegenerative disorders (Lin and Beal, 2006; Tonnies and Trushina, 2017). Mechanisms of aging are associated with oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction (Kong et al., 2014). Interestingly, aging is one of the significant risk factors for PD and correlate with oxidative stress indicating later’s role in PD pathology (Collier et al., 2017). Early direct evidence for ROS in PD etiology came from immunohistochemical detection of 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) protein adducts in the nigral neurons of the postmortem brain of seven PD patients (Yoritaka et al., 1996), which was confirmed in various follow-up studies showing an increase in iron levels and a decrease in glutathione levels in the SN regions of PD brains (Riederer et al., 1989). Recent advances in diagnostic technology combined with omic studies have provided a new approach for analyzing oxidative stress markers in the blood serum and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) of PD patients (Gokce Cokal et al., 2017). A metanalysis of such studies revealed significant increases in oxidative stress markers, including 8-oxo-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OhdG), malondialdehyde (MDA), nitrite and ferritin, whereas a substantial downregulation of antioxidants such as catalase, uric acid, GSH, and total cholesterol in the blood of PD patients compared to healthy controls (Wei et al., 2018) was observed. Thereupon, the pathological role of oxidative stress has been well-established based on clinical and experimental evidence that has been accrued to date, which is the reason that oxidative stress markers are now under investigation as diagnostic markers for detecting PD during its early stages.

3. Mitochondrial dysfunction and PD

3a. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in PD

Initial evidence ascribing the etiological role of mitochondrial stress in PD originated from the findings in which accidental human exposure to MPTP, a byproduct in the synthesis of the illicit drug, heroin, was shown to cause Parkinsonian-like symptoms (Langston et al., 1983). This was further confirmed by various experimental demonstrations of MPTP-induced DA neuronal cell death in the SN pars compacta region of the brain of laboratory rodents and non-human primates (Burns et al., 1983; Heikkila et al., 1985). More extensive investigations into the mechanism of MPTP-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity revealed that 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), the bioactive metabolite of MPTP, inhibits the complex I (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) cytochrome c reductase) of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, which gives rise to mitochondrial ROS that culminates to oxidative stress-mediated cell death (Poirier and Barbeau, 1985). Epidemiological evidence has established the association between the use of pesticides, such as rotenone, maneb, and paraquat, with the incidence of PD. As these pesticides have been shown to affect complex I and block the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC), it further infers the underpinning role of mitochondrial perturbations and oxidative stress in PD etiology. Two recent meta-analytical studies found a 11–50% augmentation in the risk of PD development with the exposure to pesticides (Gunnarsson and Bodin, 2019; Yan et al., 2018).

Mitochondrial respiration is the primary source of ROS in mammalian cells (Murphy, 2009). This proximity renders mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA, which is maintained in multiple copies in each of these organelles) sensitive to ROS exposure and mutations. The typical response to mtDNA damage is to increase the mtDNA copy number as observed generally in the healthy aging population. Increased mtDNA mutations and mtDNA loss in PD patient postmortem tissues and blood cells are indicative of mitochondrial dysfunction associated with PD (Coxhead et al., 2016; Pyle et al., 2016). Single neuron analysis from sPD postmortem brain demonstrated an increase in somatic mtDNA deletions, but the mutation rate in the SN neurons remained the same as healthy controls (Dolle et al., 2016). However, the sPD neurons failed to maintain compensatory replication for the lost mtDNA to mutations leading to the depletion of wild type mtDNA population. Mitochondria are known to regulate intracellular calcium (Ca2+) levels along with endoplasmic reticulum (which serves as the primary site for Ca2+ accumulation) when there are excessive levels of intracellular Ca2+ ions. DA neurons have a signal-independent autonomous pace-making type neuronal activity that handles sustained fluctuations in cytosolic Ca2+ levels (Surmeier et al., 2010). Evidence from experiments with the Ca2+ channel blocker, Isradipine, demonstrated chronic stress appears to be managed by Ca2+ buffering in DA neurons. Furthermore, extensive arborization of neuronal processes and relatively long-distance communication over non-myelinated axons place a high premium on energy production in SNpc neurons compared to ventral tegmental area (VTA) neurons. As a result, SNpc neurons maintain higher basal respiration, lower reserve capacity, and increased ROS, making them more vulnerable to cell death than VTA neurons (Pacelli et al., 2015).

There is also an etiological role for DA metabolism in triggering neuronal cell death. Many studies have determined that DA autoxidation to DA quinones (cellular DA metabolites) increases in ROS generation, ascribing to their swift redox cycling potential, which augments mitochondrial ROS formation eventually driving DA neurodegeneration (Zhang et al., 2019). A recent study by Burbulla et al., (Burbulla et al., 2017) described a time-dependent pathological cascade initiated by mitochondrial stress leading to oxidized DA accumulation that resulted in lysosomal dysfunction, oxidative stress, and α-synuclein accumulation in human DA neurons derived from the sporadic and familial PD forms. These authors also revealed species-specific differences in neuronal DA metabolism, which rendered human DA neurons more vulnerable to DA autoxidation-associated oxidative stress. Decreased amounts of complex I subunit and its activity were reported in postmortem PD patient midbrain samples and patient-derived platelets (Mann et al., 1992; Mizuno et al., 1989; Parker et al., 1989; Schapira et al., 1990). In cytoplasmic hybrid (cybrid) studies with host cells depleted of mitochondria derived from control or PD patient platelets, a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential, Adenosine tri phosphate (ATP) synthesis, and complex I activity and an increase in sensitivity to MPP+ (inhibitor of Complex I) were reported (Swerdlow et al., 1996). These supporting evidence, in combination with the fact that genetic mutations involved in fPD are also associated with mitochondrial perturbations demonstrates a fundamental pathophysiological role of mitochondrial dysfunction in causing PD.

3b. Assocation between fPD-linked genes and mitochondrial dysfunction

PD has a complex etiology. In the majority of cases, the disease is not inherited and is of unknown etiology. However, during the last three decades, numerous genes associated with rare monogenic forms of fPD and genetic risk factors have been identified. These mutations, although rare, yield insight into the molecular mechanisms of the origin and progression of PD. A unifying theme that has emerged after studying these mutations is the underlying role of mitochondrial dysfunction and associated oxidative stress in PD pathogenesis (Ammal Kaidery and Thomas, 2018; Bose and Beal, 2016). In this section, we briefly discuss the physiological and pathological roles of the fPD genes in mitochondrial function.

SNCA:

α-Synuclein is a small protein with 140 amino acids encoded by the SNCA gene. This protein is known to be involved in vesicle cycling and docking. Insoluble α-synuclein oligomers and fibrillar inclusions are hallmarks of PD, and these pathogenic aggregates are known to propagate in a fashion similar to that seen in prions. Mutations and overexpression due to gene duplication are known to cause fPD. Pathogenic forms of this protein are known to enter the mitochondria, cause the mitochondrial membrane to leak, affect calcium processing, and promote mitochondrial fragmentation. α-Synuclein is known to affect mitochondrial complex I function and mitochondrial protein import through the mitochondrial import receptor subunit, TOM20, resulting in mitochondrial depolarization. Pathological mutations also weaken the interaction of α-synuclein with mitochondrial-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAM) to reduce MAM function and increase mitochondrial fragmentation (Suggested reviews (Grunewald et al., 2019; Melo et al., 2018)).

LRRK2:

A member of leucine-rich repeat kinases, LRRK2 mutations cause late-onset autosomal dominant PD. LRRK2 mutations are known to increase mitochondrial oxidative stress and mitochondrial fragmentation, promote excessive mitophagy, and cause impaired mitochondrial trafficking. Mutant LRRK2 affects the normal removal function of the outer mitochondrial membrane protein, Miro, from dysfunctional mitochondria, delaying its arrest and onset of mitophagy. In induced-pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived sensory neurons, the LRRK2 mutation (G2019S) caused accumulation of autophagy markers and abnormal Ca2+ dynamics (Suggested reviews (Grunewald et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2019)).

Parkin and PINK1:

Phosphatase and tensin homolog-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) acts as a sentinel for mitochondrial depolarization, impaired proteostasis, and ROS leading to mitochondrial damage. PINK1 stabilizes on the outer membrane of depolarized mitochondria and facilitate recruitment of parkin, the E3 ubiquitin ligase responsible for mitophagy initiation of mitophagy. Parkin-ubiquitinated mitochondrial membrane proteins, voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC1) and mitofusin 1 and 2, are all phosphorylated by PINK1. Finally, P62 [sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1)] and optineurin are recruited for the assembly of LC3-positive phagophore with subsequent removal of the damaged mitochondria. PINK1 and PARK2 mutations have been shown to cause autosomal recessive PD (Suggested reviews (Pickrell and Youle, 2015; Truban et al., 2017)).

DJ-1:

Mutations in DJ-1 are associated with early onset autosomal recessive PD. DJ-1 protein regulates oxidative stress, associates with mitochondria, and aids in the removal of damaged mitochondria through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) pathway (Grunewald et al., 2019). Depending on the site, DJ-1 mutations may affect abnormal mitophagy or change Ca2+ dynamics (Strobbe et al., 2018).

HTRA2:

Mutations in mitochondrial HtrA serine peptidase 2 (HTRA2) cause autosomal dominant PD and are also implicated in the sporadic form of the disease (Ross et al., 2008). HTRA2 is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial stress signaling by removal of unfolded proteins within mitochondria. Mitochondrial ROS activates p38 the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, which acts through PINK1 and cyclindependent kinase 5 (CDK5), which phosphorylates HTRA2. Phosphorylation at the S400 of HTRA2 activates its protease function resulting in the recovery of mitochondrial activity. PD-specific mutations close to the phosphorylation site on HTRA2 may affect protease activation via phosphorylation. (Reviewed by (Desideri and Martins, 2012)).

VPS35:

Recycling of a vast number of endocytic membrane proteins is carried out by retromer, a protein complex comprised of VPS26, VPS29, and VPS35. Mutations in VPS35 have been shown to cause autosomal dominant PD. In part, VPS35 mutations act by perturbing mitochondrial dynamics via an increase in the turnover of the mitochondrial fission protein, dynamin-like protein 1 (DLP1) and/or by regulating availability of the mitochondrial ubiquitin ligase (MUL1) whose substrate is the mitochondrial fusion protein mitofusin 2 (MFN2), all of which lead to mitochondrial fragmentation (Tang et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016b). The small GTPase, Rab7, localizes to endosomes in addition to the ER, Golgi apparatus and mitochondria via the retromer complex-associated GTPase-activating (GAP) protein, TBC1D5, which is essential for mitophagy (Jimenez-Orgaz et al., 2018; Yamano et al., 2018). Loss of the retromer or defective activation of LRRK2 kinase leads to the formation of faulty mitophagosomes without ras-related protein (RAB7) thus providing a unifying theme for LRRK2, VPS35, PARK2, PINK1 and RAB7 in PD pathogenesis.

GBA:

The glucosylceramidase beta (GBA) gene expresses the lysosomal hydrolase glucocerebrosidase (GCase). Homozygous mutations in this gene are known to cause Gaucher’s disease in addition to being the most significant risk factor for PD development. Loss of GCase function leads to abnormal accumulation of macromolecules and damaged organelles and proteins, such as α-synuclein. Impaired mitophagy presents a significant contribution to GBA mutation-linked PD pathology. In the absence of GCase activity, mitochondria eventually lose cristae organization in addition to membrane potential (Reviewed by (Gegg and Schapira, 2016).

ATP13A2:

ATP13A2 mutations cause Kufor-Rakeb syndrome (KRS), a form of autosomal recessive juvenile onset PD. ATP13A2 is P5 type lysosomal transport ATPase with unknown substrates. Patient and mouse fibroblasts carrying mutant ATP13A2 have abnormal lysosomes and accumulate α-synuclein. Loss of ATP13A2 function leads to elevated mitochondrial Zn2+, eventually affecting mitochondrial function. Several studies have established mitochondrial function loss post-ATP13A2 mutation (Reviewed in (Park et al., 2015)).

CHCHD2:

The mitochondrial proteins, CHCHD2 and CHCHD10, are associated with autosomal dominant PD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Heterodimerization of CHCHD2/10 is essential for mitochondrial cristae organization (Zhou et al., 2019). Under normal physiological conditions, CHCHD proteins interact with mitochondrial complex IV to cause an increase in oxygen consumption and a reduction in ROS generation. Furthermore, CHCHD2 association with the mitochondrial inner membrane protein MICS1 stabilizes cytochrome C in the mitochondrial membrane, thus improving electron transport (Zhou et al., 2019). However, in response to mitochondrial distress, CHCHD2 accumulates, and heterodimerizes with its paralogue CHCHD10 resulting in pathogenic oligomers (Huang et al., 2018). PD-related CHCHD2 mutations affect heterodimerization, resulting in impaired mitochondrial function. CHCHD2 also regulates transcription of cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4–2 gene by binding to its oxygen-responsive element (ORE) (Suggested reviews (Imai et al., 2019)).

PLA2G6:

The PLA2G6 gene encodes a Ca2+-independent phospholipase, which is a protein distributed in cytosol and membrane-bound organelles, including mitochondria. A mutation in this gene causes a rare adult-onset dystonia with Parkinsonism. Fly, and mouse models show dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP production along with the accumulation of degenerated mitochondria in phospho-Ser129 α-synuclein immunoreactive inclusion bodies. Elevated lipid peroxidation and loss of retromer function also contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction (reviewed in (Ammal Kaidery and Thomas, 2018; Guo et al., 2018)).

FBXO7:

A mutation in the F-box only protein 7 (FBXO7) causes early onset autosomal recessive PD with the pyramidal syndrome. The protein forms one of the four subunits of the S-phase kinase-associated protein (SKP1)-cullin-F-box (SCF-box) ubiquitin ligase complex. Of the 29 potential FBXO7 substrates in the mitochondria, including CHCHD2, glycogen synthase kinase 3b (GSK3b) and TOM20, only the latter two are confirmed experimentally. FBXO7 is known to assist in facilitating mitochondrial homeostasis by directly interacting with parkin. In the absence of FBXO7 activity, pathological activation of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) causes a decrease in nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) content and complex I activity (Delgado-Camprubi et al., 2017) (Reviewed in (Ammal Kaidery and Thomas, 2018; Zhou et al., 2018c)).

Overall, genetic mutations linked to fPD strongly underscore the central role of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in PD pathogenesis. Accumulated knowledge from the genes involved in fPD implicates three significant pathways that can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction. These pathways include impaired proteostasis (α-Synuclein, HTRA2, GBA), abnormal mitochondrial maintenance (PINK1, PARK2, LRRK2, VPS35) and mitochondrial ROS generation (α-Synuclein, DJ1, PARK2, PINK1), all of which intimately interact with each other. This interaction serves as a self-perpetuating cycle that amplifies mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress culminating in PD pathogenesis and progression. To restore these pathways, Nrf2/ARE signaling seems to be a promising target since it regulates most of the cellular mechanisms involved in the above-mentioned pathological pathways.

4. The interaction between oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction: Role of the Nrf2 signaling

4a. Effect of Nrf2/ARE signaling on oxidative stress associated with PD

The transcription factor NF-E2 related protein factor 2 (Nfe2L2, commonly referred as Nrf2) controls the expression of over 250 genes marked by its binding site ARE (antioxidant response element) (Hayes and Dinkova-Kostova, 2017). Its cytosolic repressor, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) senses oxidative stress in the cell, resulting in the escape of Nrf2 from Keap1 mediated proteasomal degradation. Once in the nucleus, Nrf2 binds to a cis-acting transcriptional element in promoters called AREs (5’-A/GTGAC/GNNNGCA/G-3’) and heterodimerizes with small-Maf proteins (transcription factors) to activate transcription of downstream genes. This activity is also further modulated by the repression of the BTB domain and CNC Homolog 1 (BACH1). Thus, the Nrf2-Keap1 protein complex act as a cellular redox sensor and maintains redox homeostasis by regulating the transcription of antioxidant genes (Yamamoto et al., 2018).

The Nrf2/ARE system is affected by aging and neurodegenerative diseases. A meta-analysis of PD and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in multiple tissues revealed 54 affected genes, of which 31 down-regulated genes contain ARE (Wang et al., 2017). Surprisingly Nrf2 and its nuclear binding partner, the small Maf binding protein Maf-F, are upregulated despite the downregulation of target genes. A review by Zhang et al. (2015) discusses age-dependent decreases in Nrf2-responsive gene products, such as SOD2, catalase, glutathione peroxidases (GPX), glutathione S-transferase (GST), GCL, HMOX-1 and NQO1 (Zhang et al., 2015). The same study found P62 increased in aging tissues, perhaps due to accumulation in inclusion bodies. Notable exceptions for age-dependent decreases were Nrf2 and its repressor BACH1. A study in rare fatal progeria (Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HPGS)) provides one plausible mechanism for this increase. During HGPS, alternatively spliced nuclear membrane protein lamin produces a protein called progerin that accumulates in the nuclear membrane, sequesters Nrf2, and thereby, suppresses signaling despite high stabilization of Nrf2 (Kubben et al., 2016). Therefore, these findings establish that aging decreases the cellular protective capabilities by diminishing the role of the Nrf2/ARE pathway.

The reducing power of the eukaryotic cell primarily originates from the stored pool of GSH. Glutamate cysteine ligase catalytic (GCLC) and modifier (GCLM) subunits direct the biosynthesis while GSR1 mediates the reduction of glutathione after utilizing the reducing power of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide diphosphate (NADPH). The Nrf2/ARE pathway regulates all of these enzymes (Harvey et al., 2009; Sasaki et al., 2002). In fact, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Nrf2 activator for multiple sclerosis, dimethylfumarate (DMF), has been shown to upregulate GSH levels and induce Gclc, Gclm and Gsr genes in various cell lines as well as in mouse brain (Ahuja et al., 2016; Hsieh et al., 2014; Jing et al., 2015). Moreover, cellular NADPH availability is controlled by Nrf2, since Nrf2 regulates the expression of critical enzymes that participate in NADPH synthesis during glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) and pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) (Lee et al., 2003; Mitsuishi et al., 2012; Thimmulappa et al., 2002; Wu et al., 2011). Biotransformation related enzymes such as aldehyde dehydrogeneses, which are involved in alcohol detoxification and in doing so reduce NADP+ to NADPH, are also under transcriptional regulation by Nrf2 (Ushida and Talalay, 2013). Besides, thioredoxin, thioredoxin reductase 1, and sulfiredoxin genes also carry ARE elements in their promoters (Abbas et al., 2011; Sakurai et al., 2005; Tanito et al., 2007). These proteins reduce oxidized protein-thiols to maintain thiol homeostasis. Concomitantly, Nrf2 activating agents such as sulforaphane, triterpenoids, soy isoflavone, and small molecule DMF, all show an increase in the typical set of genes such as Gclc, Gclm, Nqo1, Hmox1, and Txnrd1, thus demonstrating Nrf2 activation induced augmentation in cellular glutathione and NADPH levels. Besides, Nrf2 activation by DMF and monomethylfumarate (MMF), the bioactive metabolite of DMF, had been reported to increase mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and biogenesis (Ahuja et al., 2016; Kaidery et al., 2013). Therefore, by modulating both mitochondrial and non-mitochondrial metabolic pathways, Nrf2/ARE system modulates cellular levels of oxidative stress, and hence, emerges as a promising target in PD pathogenesis.

4b. Nrf2 and Mitochondria

A mitochondrion is an organelle that is separated from the rest of the cell by two membranes. With partial genetic autonomy, mitochondria were considered as only responsible for energy production. Recent advances, however, indicate that mitochondria are more robustly integrated organelle that is sensitive to perturbations in nuclear response via a chain of cytosolic signaling to maintain cellular homeostasis (Yun and Finkel, 2014). Directly and indirectly, Nrf2 regulates multiple aspects of mitochondrial well-being including mitochondrial biogenesis, dynamics, and autophagy.

Nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1) is a transcription factor that regulates mitochondrial biogenesis. NRF1 carries four AREs in its promoter thus allowing transcriptional regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis by Nrf2 in response to stress, such as carbon monoxide exposure, or by Nrf2 activators- such as fumarate (Hayashi et al., 2017; Piantadosi et al., 2008). A recent study showed that NRF1 is affected by BACH1 (the nuclear repressor of Nrf2) through secondary mechanisms since NRF1 did not show BACH1 binding (Warnatz et al., 2011). Additionally, NRF1 in combination with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1α) modulates the expression of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), which regulates mitochondrial proliferation. Our data is in agreement with other studies and indicates that DMF treatment results in increased TFAM expression and high mtDNA content, suggesting an increase in mitochondrial replication (Ahuja et al., 2016; Hayashi et al., 2017).

In addition to the transcription mediated modulation of mitochondrial biogenesis, Nrf2 has been shown to interact with mitochondria directly. A recent report demonstrated that Keap1 bridges Nrf2 to associate with mitochondrial serine/threonine phosphatase, phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5 (PGAM5) (Lo and Hannink, 2008). This association results in a ternary complex that regulates stress-induced retrograde trafficking of mitochondria and Keap1-mediated Miro2c degradation, which implies that the age-dependent reduction in Nrf2 activity correlates with mitochondrial motility (O’Mealey et al., 2017). Furthermore, ablation of Keap1 activity led to hyperfused mitochondrial morphology, thus affecting mitochondrial dynamics (Sabouny et al., 2017). Sabouny et al. (2017) demonstrated that the increase in proteasome activity in response to constitutively active Nrf2 led to selective degradation of the mitochondrial fission protein, dynamin-like protein 1 (Drp1), which finally resulted in mitochondrial hyperfusion and dysfunction (Sabouny et al., 2017). Nrf2 also aids mitochondrial-nuclear retrograde communication by ferrying mitochondria-derived peptide, mitochondrial open reading frame of the 12S rRNA-c (MOTS-c) to the nucleus in response to a stress-related event (Kim et al., 2018). MOTS-c enhances the transcriptional activity of Nrf2 at ARE in addition to other related sites. In doing so, MOTS-c facilitates mitochondrial influence over Nrf2 activity in conditions of cellular stress and thus, maintains cellular homeostasis.

Continuous surveillance and regulated autophagic removal of damaged mitochondria are essential for maintaining mitochondrial quality and for proper mitochondrial functioning. Nrf2 under oxidative stress conditions modulates mitochondrial quality by regulating PINK1 expression (Murata et al., 2015). The mechanism of mitochondrial autophagy involves stabilization of PINK1 on the outer membrane of dysfunctional mitochondria, which in turn employs parkin to recruit P62 for initiation of mitochondrial clustering and eventual removal (Geisler et al., 2010; Narendra et al., 2010). Moreover, a previous report showed that P62 itself has an ARE element in its promoter (Jain et al., 2010). On the other hand, P62, in addition to other Keap1 substrates (the tumor suppressor gene (WTX), partner and localizer of BRCA2 (PALB2), dipeptidyl-peptidase 3 (DPP3), and CDK20), was shown to bind to the ETGE motif in Keap1 resulting in Nrf2 stabilization and activation (Fu et al., 2019; Komatsu et al., 2010). Indeed, a recent report showed DMF treatment attenuates α-synucleintoxicity by increasing P62 mediated autophagy (Lastres-Becker et al., 2016). During cancer treatment, exposure to the high linear energy transfer carbon radiation used to treat tumors results in TCA cycle disruption and loss of mitochondrial integrity. Under such stress conditions, supplementation of melatonin restored PINK1 and Nrf2 activity in addition to mitochondrial function in radiation-exposed hippocampal neurons (Liu et al., 2018). Moreover, increasing mitophagy alone has been shown to have beneficial effects on mitochondrial function and attenuating misfolded protein accumulation induced neurodegeneration. For example, in yeast models for prion disease, the increase of autophagic flux post-rapamycin treatment was shown to cause an improvement in the clearance of pathogenic scrapie proteins, PrPsc (Scrapie form of prion protein) (Speldewinde et al., 2015). In experimental PD, Sulforaphane protected against rotenone-induced DA neurodegeneration by augmenting Nrf2 mediated mitophagy through inhibition of mTOR pathway (Zhou et al., 2016).

There is a wealth of experimental evidence supporting the beneficial effects of Nrf2 activation in improving mitochondrial function in neurodegenerative disorders. For example, mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant MitoQ improved neurological deficits in a traumatic brain injury mouse model via Nrf2 (Zhou et al., 2018a). In Neuro2A (N2A) cells induction of Nrf2 using TBHQ attenuated human mutant α-synuclein (A53T) transgene induced suppression of mitochondrial respiration (Fu et al., 2018). Even exercise-induced increases in mitochondrial biogenesis and expression of antioxidant genes, such as SOD1 and 2 and catalase in skeletal muscle is mediated by ROS- and RNS-induced Nrf2 activation (Merry and Ristow, 2016). Concordantly, acute exercise-associated manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) and GSH levels correlated linearly with Nrf2 activation in skeletal muscles of experimental animals (Wang et al., 2016a). Nrf2/ARE pathway also regulates the GSH system, which is crucial for controlling mitochondria-generated ROS and is impaired in PD pathology. For instance, cell lines derived from PD patients showed reduced GSH levels, and by activating Nrf2, levels of GSH can be restored (Cook et al., 2011). Overall, there is ample evidence to support that targeting the Nrf2/ARE pathway in neurodegenerative disorders such as PD to improve mitochondrial function and attenuate excessive accumulation of mitochondrial ROS.

4c. Nrf2 as a manipulator of metabolomics

Recent studies have demonstrated the profound influence of Nrf2 in controlling how cells produce energy (ATP) (Dinkova-Kostova and Abramov, 2015). Most of the ATP produced by mammalian cells originates from oxidative phosphorylation and mitochondrial respiration. However, in the absence of Nrf2, anaerobic respiration (glycolysis) assumes a dominant role in energy production leading to diminished mitochondrial function and mitochondrial membrane potential (Ψm) (Hayashi et al., 2017). As a result, the silencing of Nrf2 activity leads to a decrease in oxygen consumption and an increase in glycolysis (Ahuja et al., 2016; Navneet et al., 2019). Recent reports demonstrated loss of Nrf2, causing a decrease in mitochondrial respiration concomitant with an increase in ROS production and protein nitrosylation (Coleman et al., 2018; Holmstrom et al., 2013). In cancer-initiating cells (cells responsible for the initiation and maintenance of cancer), glucose-regulating protein/phospho-protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (GPR78/PERK) signaling leads to activation of Nrf2 (Chang et al., 2018a). This signaling appears to be responsible for the activation of glycolysis and PPP by inducing the key enzyme (as presented in fig. 1), transketolase (TKT), in a process separate from TCA inhibition via induction of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1) that depletes TCA from its substrate, acetyl-CoA (Chang et al., 2018a; Xu et al., 2016). Nrf2 represents a critical event in the development of cancer by contributing to Warburg hypothesized metabolic reprogramming (Mitsuishi et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2018; Warburg et al., 1927). The mitochondrial Ψm is maintained in Nrf2 KO mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) by reversing complex V activity at the expense of ATP since glucose withdrawal diminishes Ψm. Also, exposure to oligomycin was shown to increase ATP synthesis in Nrf2 KO neurons (Holmstrom et al., 2013). As expected, Nrf2 ablation also led to increased oxidative stress. Our results showed that short-term exposure to fumarate caused an increase in oxygen consumption rates [OCR] measure of mitochondrial respiration) in wild type MEF in addition to extracellular acidification rates [ECAR] measure of glycolysis) (Ahuja et al., 2016). In contrast, we observed that in the case of Nrf2 KO MEF, basal OCR was significantly low and remained unresponsive to fumarate treatment while maintaining significantly increased glycolytic capacity. These results establish the presence of higher glycolytic capacity in the KO cells, while fumarate could increase substrates for mitochondrial respiration in WT that are not utilized in KO MEFs (Ahuja et al., 2016).

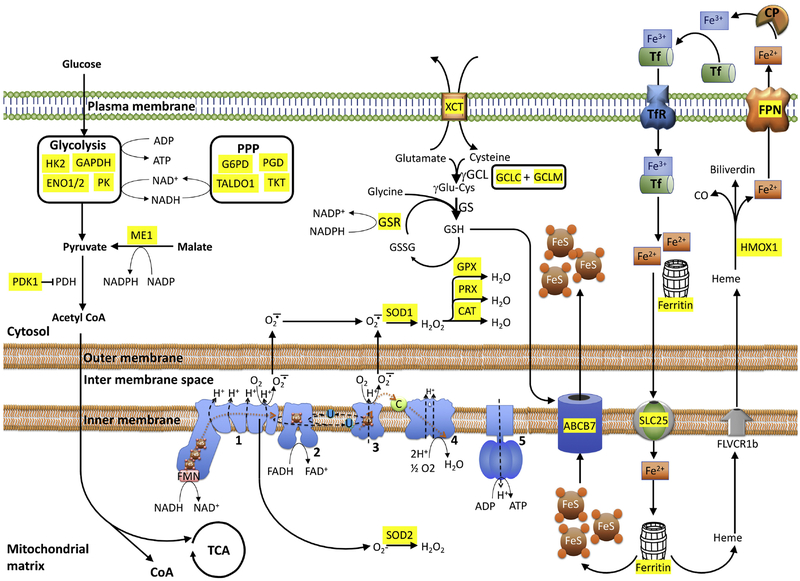

Figure 1: Nrf2 is the master regulator of cellular redox, energy metabolism, and iron homeostasis.

The main energy source of the cell, glucose enters catabolic processes in glycolysis followed by TCA or the anabolic chain of PPP. Nrf2 regulates rate-limiting enzymes to control the flow of substrates to these pathways. Oxidative phosphorylation is the main contributor to ROS. Cellular redox status is managed by enzymes such as SOD1 and SOD2 that converts superoxides to peroxides which eventually neutralized by catalases and peroxidases. Nrf2 also regulates the transcription of enzymes involved in glutathione synthesis, the main cellular reducing currency. Iron is another source of cellular ROS, managed by Nrf2 transcribed transporters. Enzymes whose transcription is directly regulated by Nrf2 is highlighted in yellow. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5: mitochondrial complexes 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5; Cat: Catalase; C: cytochrome C; FeS: Iron-sulfur clusters (ISCs); γGCL: γglutamate-cysteine ligase; GS; GSR: glutathione reductase; GPX: glutathione peroxidase; HMOX1: hemeoxygenase 1 ; Me1: Malic enzyme 1; PDH: pyruvate dehydrogenase; PDK1: pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1; PPP: Pentose Phosphate Pathway; PK: pyruvate kinase; PRX: peroxidase; SLC25: Mitoferrin; SOD1/2: superoxide dismutase-1 or 2; TCA: tricarboxylic cycle; U: ubiquinone; XCT: SLC7A11.

Genetic silencing of Keap1 in cells in which Nrf2 is constitutively active resulted in postnatal death in mice. However, microarray data from esophageal tissue showed significant upregulation of genes involved in glycolysis, PPP, fatty acid oxidation (FAO) in addition to GSH metabolism in Keap1 KO mice (Fu et al., 2019). Maintenance of homeostasis requires mechanisms for integration and crosstalk between all partners. In reverse, Keap1 was also shown to intervene in communication between the glycolytic and Nrf2/ARE systems. Inhibition of phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (PGK1), a key enzyme in glycolysis, led to the accumulation of the metabolite, methylglyoxal, which covalently transformed Keap1 to stabilize and activate Nrf2 (Bollong et al., 2018). In another example of reverse metabolomic regulation, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and toll-like receptor (TLR) stimulation were shown to cause an increase in the expression of aconitate decarboxylase 1 (also called immune responsive gene 1 or IRG1) and diverted aconitate from the TCA cycle to produce itaconate. Itaconate traverses the mitochondrial membrane via the dicarboxylate, citrate, or oxoglutarate carriers and covalently modifies Keap1 cysteines by Michael addition to stabilize and activate Nrf2 (Mills et al., 2018; O’Neill and Artyomov, 2019). Besides Nrf2, its nuclear inhibitor, BACH1, negatively regulates several ETC-related gene expressions with a concomitant increase in mitochondrial acidification and an increase in glycolysis (Lee et al., 2019). Combining this finding with the fact that BACH1 levels increases in aging (Zhou et al., 2018b), and dysregulation of this gene is observed in neurodegenerative diseases [such as Huntington’s Diseasse (HD) and PD], suggests a direct pathogenic role for Nrf2/Bach1/ARE pathway in these disorders (Labadorf et al., 2017). Henceforth, by regulating substrate availability and controlling the transcription of key enzymes involved in cellular glucose metabolism, Nrf2 exhibits a central role in regulating mitochondrial metabolomics and functional well-being.

4d. Nrf2 and Iron homeostasis

Iron homeostasis is central for cell survivability as it is one of the necessary elements required for normal cellular functioning while at higher concentrations, it is toxic. Numerous studies have implicated the role of iron accumulation in PD pathology. The earliest reports indicate that iron accumulation occurred in the ventrolateral nucleus of the thalamus in PD patients, which is strengthened by recent reports indicating that a significant increase in iron levels correlated with PD pathology (Lee and Lee, 2019; Munoz et al., 2016). Intriguingly, PD brain iron accumulation in the nigral area is in the form of neuromelanin adducts, which are detected by combined nigrosome-1 and neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging (NM-MRI), has emerged as a method for differential PD diagnosis (Jin et al., 2019; Medeiros et al., 2016). A reported increase in iron deposition is observed both in the nigral microglia and nigral DA neurons; however, given the fact that these results were obtained from the postmortem end-stage PD brains, it is plausible that phagocytized damaged dopaminergic neurons may be the source of iron deposits in microglia (Hirsch, 2009). Previous studies with MPTP-based experimental PD models elucidated the role of iron in exacerbating MPTP toxicity and the putative efficacy of iron chelators, such as lactoferrin, in neuroprotection against MPTP-induced DA neurodegeneration (Xu et al., 2019). Recent investigations have delineated dysregulation of different iron homeostasis-related proteins in PD patients that may contribute to iron accumulation. For instance, augmented divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1/SLC11A2) expression in the SN of PD patients (Hirsch, 2009) and mutations in transferrin (TF, the neuronal iron uptake protein) and ceruloplasmin (CP, an iron export protein) are associated with an increase in PD susceptibility (Ayton et al., 2013; Rhodes et al., 2014).

Iron is necessary for the proper mitochondrial function, which is especially critical in cases of energetically demanding DA cells. Mitochondria play a central role in the biosynthesis of heme (ferriprotoporphyrin IX) and iron-sulfur clusters (ISCs), two primary functional forms of cellular iron. Mitochondria also require iron-containing factors for the respiratory complexes of ETC (DeGregorio-Rocasolano et al., 2019). Interestingly, chronic iron deficiency in developing embryonic hippocampal neuronal cultures was shown to result in a decrease in mitochondrial density and diminutive oxidative capacity due to impaired anterograde mitochondrial transport in the growing dendrites. These findings confirm the significance of iron metabolism in maintaining mitochondrial and neuronal function (Bastian et al., 2019). A great deal of literature has described that extracellular iron is preferentially transported into the mitochondria as compared to cytosol (see figure 1). This transport is likely be attributed to mitoferrin (also known as solute carrier family 25, SLC25)-mediated iron transport from the plasma membrane to mitochondria, and the direct interaction of transferrin-containing endosomes to mitochondria, a process explained in the “kiss-and-run” hypothesis (DeGregorio-Rocasolano et al., 2019; Hamdi et al., 2016). Recent studies have demonstrated that an increase in expression of mitoferrin 2 leads to mitochondrial iron accumulation in human HD patients and a mouse model of HD (Agrawal et al., 2018). The mitochondrial-generated ISCs are exported into the cytoplasm via the inner mitochondrial membrane transporter, ABCB7; this transport is a glutathione-dependent process (shown in fig.1). Mitochondrial iron overload depletes mitochondrial GSH levels and may contribute to a decrease in ISC synthesis by affecting glutathione reductase enzyme (Grx5) and ISC export by affecting ABCB7-mediated transport (Rouault, 2016).

Mitochondria produces more than 90% of the total cellular ROS, which leads to oxidative stress along with aging and other genetic and environmental risk factors. Oxidative stress results in mitochondrial dysfunction and synucleinopathy that further debilitates oxidative stress management in an interdependent feedback loop. Findings from other studies have indicated that iron and DA treatments can cause mitochondrial membrane potential disruption, oxidative stress, intracellular α-synuclein accumulation, increased parkin expression, and DA cell death in SK-N-SH cells (Li et al., 2010). Similarly, a study by Xia et al. (Xiao et al., 2018) indicated that nuclear transcription factor EB (TFEB), a master transcriptional regulator of autophagosome-lysosome fusion, mediated iron-induced α-synuclein aggregation and neuron-to-neuron transmission in a midbrain DA neuronal cell line. Conversely, Ortega et al. proved α-synuclein overexpression results in an increase in intracellular iron levels and its redistribution from the cytoplasm to perinuclear regions (Ortega et al., 2016). This finding was supported by an in vivo investigation in mutant Drosophila expressing A53T and A30P mutations which exhibited that iron overload induces distinctive neuropathology compared to WT α-synuclein-expressing flies (Zhu et al., 2016). These pieces of evidence show a convergence of iron accumulation and other PD-associated signaling factors on to mitochondrial dysfunction that eventually leads to DA neuronal cell death in PD.

Intriguingly, not even a decade ago, a new form of cell death called ferroptosis, which is biochemically and morphometrically distinct from apoptosis, necrosis, and necroptosis, was discovered. Ferroptosis is a regulated form of cell death that is characterized by iron-dependent and glutathione-modulated accumulation of lipid hydroperoxides triggering a specific type of cell death (Dixon et al., 2012). Ferroptosis causes distinct and discernable changes in mitochondrial morphology, including an increase in mitochondrial swelling, reduction in cristae, and outer membrane rupture (Dixon et al., 2012). Although the lack of specific ferroptosis cellular markers has deterred further investigation, recent studies have revealed direct and indirect evidence of ferroptosis mediated neuronal degeneration in PD and other neurodegenerative disorders (Do Van et al., 2016; Guiney et al., 2017). The role of iron in PD pathophysiology along with the fact that GSH depletion, lipid peroxidation and elevated ROS are also present in the PD patients favors contribution of ferroptosis in PD (Cassarino et al., 1997; Dexter et al., 1986; Sian et al., 1994). Also, deferiprone, an iron chelator, showed promising results in attenuating oxidative stress-mediated damage in DA cells and improving motor functions in an MPTP-based toxin and α-synuclein overexpressing genetic model of PD (Carboni et al., 2017; Devos et al., 2014). The data from a phase 2 randomized double-blinded placebo controlled clinical trial of deferiprone in PDA patients depicts a trend toward improvement in motor functions and quality of life although the results are not statistically significant. These results warrant more extensive clinical trials for iron chelation strategies for PD (Carboni et al., 2017). Recently, researchers have found characteristic ferroptosis in differentiated LUHMES cells (human dopaminergic cell line), ex vivo organotypic slice cultures and an in vivo MPTP mouse model of PD (Do Van et al., 2016). Mainly, ferroptosis appears to be mediated by GSH depletion, GSH peroxidase 4 (GPX4) dysregulation, impairment of the cystine-glutamate antiporter system xCT (SLC7A11), and an increase in lipid peroxidation (Weiland et al., 2018). The mitochondrial role in ferroptosis appears to be dependent on the cellular context and remains controversial as cells deprived of mitochondria also exhibit ferroptosis (Gaschler et al., 2018). A recent report by Gao et al., indicates a specific mitochondrial role in cysteine-deprivation-induced ferroptosis but not in GPX4 inhibition-induced ferroptosis (Gao et al., 2019). The authors found that the mitochondrial TCA cycle and the ETC serve as the primary site of cellular lipid peroxide production. Nrf2 regulates iron homeostasis by modulating various factors involved in iron storage, iron transport, mitochondrial heme and ISCs synthesis, heme catabolism, and ferroptosis. Ferritin heavy and light chains (FTH1 and FTL, respectively) and ferroportin (FPN1) contain an ARE sequence and are modulated by both Nrf2 and BACH1 during erythropoiesis (Hintze et al., 2007; Kerins and Ooi, 2018). Nrf2/BACH1 axis also appears to modulate hemeoxygenase1 (HO-1), an inducible heme catabolizing enzyme, which has been shown to protect DA neurons against MPTP-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in mouse models of PD (Hung et al., 2008).

In addition to modulating iron levels, the Nrf2/BACH1 pathway was also shown to regulate ferroptosis by modulating other cellular factors. By modulating GPX4, the SLC7A11, γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (GCS), GCLM, and the GCLC genes, the Nrf2/Bach1 pathway appears to maintain cellular GSH levels and hence, regulates ferroptosis (reviewed in (Kerins and Ooi, 2018)). Indeed, the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway is shown to block ferroptosis and promote cell proliferation in glioblastoma cells (Fan et al., 2017). A recent report also indicates that HMOX-1 induction mediated attenuation of ferroptosis in renal proximal tubule cells (Adedoyin et al., 2018). However, there are also reports of HMOX-1-mediated ferroptosis (Chang et al., 2018b; Kwon et al., 2015), which indicates that a cellular context-based mechanism of HMOX-1 role in ferroptosis exists. Hence, further investigations are required to delineate a role for HMOX-1 in ferroptosis-related cell death. Based on these facts, Nrf2 plays a vital role in controlling iron levels, augmenting GSH levels, and causing a decrease in ROS generation. Thus, Nrf2 can be an essential target in treating ferroptosis-related DA cell death in PD patients.

5. Nrf2 as a potential target for the mitochondrial abnormalities in PD

Modern medicine has made tremendous progress in treating PD. Initial treatments were focused on DA substitution and preservation of the available DA. Recently, with the advent of deep brain stimulation, the quality of the life of a PD patient has improved substantially. Although effective management of disease symptoms and progress made in disability-adjusted life years due to PD, in the absence of programs that halt the neurodegeneration, the disease remains progressive with no definitive cure (Poewe et al., 2017). Considering the mitochondrial defects in PD, therapeutics that target mitochondrial health show great potential, which can be attained alternatively by targeting the Nrf2-ARE system.

In the last decade, there has been great enthusiasm for developing potential neurodegenerative disease treatments via exploitation of the Nrf2/ARE system. For instance, overexpression of Nrf2 or its DNA binding partner Maf-S protected locomotor phenotype in an α-synuclein-expressing Drosophila model for PD (Barone et al., 2011). In an experimental model of PD, ablation of Keap1 by siRNA rendered partial protection from MPTP toxicity (Williamson et al., 2012). We demonstrated the effectiveness of the Nrf2 activators, triterpenoid, and fumarate, in PD by targeting Keap1 to stabilize Nrf2 (Ahuja et al., 2016; Kaidery et al., 2013). Both DMF and MMF used in the short-term caused an increase in mitochondrial activity in addition to glycolysis in an Nrf2 dependent manner. Activation of the Nrf2 pathway by DMF, upregulated NRF1 levels and increased mitochondrial biogenesis in cells, mice, and clinically treated Multiple Sclerosis (MS) patients (Hayashi et al., 2017). DMF was found to alter the expression of the autophagy markers, P62 and LC3, in glial cell lines, which led to the generation of wound healing and less inflammatory phenotype that could have a role in drug-related actions for protecting cells against virus-mediated α-synuclein toxicity in mice brain (Lastres-Becker et al., 2016).

Furthermore, Nrf2 may exert diverse tactics for defending cells against different toxicities. In rat neurons co-transfected with Nrf2 and α-synuclein, Nrf2 protected the neurons by lowering the neuronal load of α-synuclein via an increase in proteasomal removal (Skibinski et al., 2017). However, in the case of LRRK2 toxicity, Nrf2 overexpression caused sequestration of mutant LRRK2 into inclusion bodies and thus protected the neurons by restraining the soluble mutant LRRK2 levels in the neurons (Skibinski et al., 2017). Fumarate, which activates Nrf2, was shown to cause a reduction in oxidative stress, mitochondrial impairment and neuroinflammation in experimental PD models (Ahuja et al., 2016). The observation of low incidence of PD in subjects with high serum urate led to the clinical trial of inosine to increase urate levels in patients with early PD (Parkinson Study Group et al., 2014). In cell and animal models, high urate levels induced activation of the Nrf2/ARE system (Zhang et al., 2014). Along the same line, coenzyme Q10 and MitoQ were tested in clinical trials in order to directly address mitochondrial impairment in PD, but these compounds failed to generate a positive outcomes. Other failures include creatine and pioglitazone (PPARg agonist) [reviewed in (Ammal Kaidery and Thomas, 2018)]. Many of these single-target PD intervention strategies have failed to prove efficacy in clinical trials, and the field is in need of targets that exert pleiotropic effects through multiple mechanisms such as the Nrf2 pathway. Although activation of Nrf2 represents a promising approach for neurodegenerative diseases, unfortunately, Nrf2-based drugs have relied on electrophilic pharmacophores, which are not well tolerated in patients (Gazaryan and Thomas, 2016). Therefore, research is being pursued to identify novel non-electrophilic Nrf2-activators as therapeutic agents and to identify alternate targets to safely activate the the Nrf2/ARE signaling system, that may be effective in treating PD patients. Small peptide-based molecules are envisioned as non-electrophilic Nrf2 activators, and certainly, the early investigations have reported promising results [for peptide-based Nrf2-activators please consult the review (Bresciani et al., 2017)]. BACH1 (the Nrf2 repressor) inhibition is being investigated as a novel approach to activate the Nrf2 pathway that can be utilized in PD and other neurodegenerative disorders. New and compelling evidence from other oxidative stress disease models has strengthened and prompted investigations for examining the role of BACH1 in PD (Harusato et al., 2013; Kondo et al., 2013) and other neurodegenerative disorders.

5. Conclusion

Numerous studies indicate an active role for mitochondrial dysfunction in PD progression and perhaps its initiation. Oxidative stress also has an equally important role in the etiology of this disease. The Nrf2/ARE system offers a rare candidate for a holistic approach to address mitochondrial wellness while managing ROS levels, proteostasis, and inflammation. So far, many pharmacological candidates were tested in preclinical models of PD and other neurodegenerative diseases. Many of them were electrophilic and caused unacceptable side effects. Development of non-electrophilic pharmacological activators that allow compounds to cross the blood-brain barrier remains challenging. Also, specific biomarkers for early detection of PD remain elusive. At present, the diagnosis of PD depends on the development of neurological symptoms. Any intervention at this stage of the disease may not be enough to undo the pathology at this point in the disease. Hence, targeting Nrf2 in the early phases of PD may present a strong potential for preserving the neurological well-being of many patients with neurodegenerative disease, especially those with PD.

Highlights:

The loss of midbrain dopamine-producing neurons is the salient feature of the neurodegenerative disorder, Parkinson’s disease.

PD experimental animal and cell models and PD patient-derived cells and tissue show proteinopathy, elevated oxidant stress, and impaired mitochondrial function.

The oxidative stress sensitive transcription factor Nrf2 regulates expression of over 250 genes responsible for anti-oxidant homeostasis.

Recent advances show the importance of Nrf2 activity in shaping cellular metabolome and mitochondrial function.

The overlapping functions posit Nrf2 as a potential target for translational research in PD.

Acknowledgements:

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health grant NS101967.

Abbreviations

- SNCA

α-Synuclein

- MPP+

1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium

- MPTP

1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

- 8-OhdG

8-oxo-2’-deoxyguanosine

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- ARE

Antioxidant response element

- BACH1

BTB domain and CNC Homolog 1

- DMF

Dimethylfumarate

- DA

Dopaminergic

- ETC

Electron transport chain

- fPD

Familial Parkinson’s disease

- GSH

Glutathione

- iPSC

Induced-pluripotent stem cell

- Keap1

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- MMF

Monomethylfumarate

- Nfe2L2 (Nrf2)

NF-E2 related protein factor 2

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PPP

Pentose phosphate pathway

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- sPD

Sporadic Parkinson’s disease

- SN

Substantia nigra

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid cycle

- VTA

Ventral tegmental area

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbas K, Breton J, Planson AG, Bouton C, Bignon J, Seguin C, Riquier S, Toledano MB, Drapier JC, 2011. Nitric oxide activates an Nrf2/sulfiredoxin antioxidant pathway in macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med 51, 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adedoyin O, Boddu R, Traylor A, Lever JM, Bolisetty S, George JF, Agarwal A, 2018. Heme oxygenase-1 mitigates ferroptosis in renal proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 314, F702–F714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal S, Fox J, Thyagarajan B, Fox JH, 2018. Brain mitochondrial iron accumulates in Huntington’s disease, mediates mitochondrial dysfunction, and can be removed pharmacologically. Free Radic Biol Med 120, 317–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja M, Ammal Kaidery N, Yang L, Calingasan N, Smirnova N, Gaisin A, Gaisina IN, Gazaryan I, Hushpulian DM, Kaddour-Djebbar I, Bollag WB, Morgan JC, Ratan RR, Starkov AA, Beal MF, Thomas B, 2016. Distinct Nrf2 Signaling Mechanisms of Fumaric Acid Esters and Their Role in Neuroprotection against 1-Methyl-4-Phenyl-1,2,3,6-Tetrahydropyridine-Induced Experimental Parkinson’s-Like Disease. J Neurosci 36, 6332–6351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammal Kaidery N, Thomas B, 2018. Current perspective of mitochondrial biology in Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem Int 117, 91–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayton S, Lei P, Duce JA, Wong BX, Sedjahtera A, Adlard PA, Bush AI, Finkelstein DI, 2013. Ceruloplasmin dysfunction and therapeutic potential for Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol 73, 554–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone MC, Sykiotis GP, Bohmann D, 2011. Genetic activation of Nrf2 signaling is sufficient to ameliorate neurodegenerative phenotypes in a Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Dis Model Mech 4, 701–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian TW, von Hohenberg WC, Georgieff MK, Lanier LM, 2019. Chronic Energy Depletion due to Iron Deficiency Impairs Dendritic Mitochondrial Motility during Hippocampal Neuron Development. J Neurosci 39, 802–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollong MJ, Lee G, Coukos JS, Yun H, Zambaldo C, Chang JW, Chin EN, Ahmad I, Chatterjee AK, Lairson LL, Schultz PG, Moellering RE, 2018. A metabolite-derived protein modification integrates glycolysis with KEAP1-NRF2 signalling. Nature 562, 600–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose A, Beal MF, 2016. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem 139 Suppl 1, 216–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresciani A, Missineo A, Gallo M, Cerretani M, Fezzardi P, Tomei L, Cicero DO, Altamura S, Santoprete A, Ingenito R, Bianchi E, Pacifici R, Dominguez C, Munoz-Sanjuan I, Harper S, Toledo-Sherman L, Park LC, 2017. Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (NRF2) drug discovery: Biochemical toolbox to develop NRF2 activators by reversible binding of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1). Arch Biochem Biophys 631, 31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbulla LF, Song P, Mazzulli JR, Zampese E, Wong YC, Jeon S, Santos DP, Blanz J, Obermaier CD, Strojny C, Savas JN, Kiskinis E, Zhuang X, Kruger R, Surmeier DJ, Krainc D, 2017. Dopamine oxidation mediates mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Science 357, 1255–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns RS, Chiueh CC, Markey SP, Ebert MH, Jacobowitz DM, Kopin IJ, 1983. A primate model of parkinsonism: selective destruction of dopaminergic neurons in the pars compacta of the substantia nigra by N-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 80, 4546–4550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carboni E, Tatenhorst L, Tonges L, Barski E, Dambeck V, Bahr M, Lingor P, 2017. Deferiprone Rescues Behavioral Deficits Induced by Mild Iron Exposure in a Mouse Model of Alpha-Synuclein Aggregation. Neuromolecular Med 19, 309–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassarino DS, Fall CP, Swerdlow RH, Smith TS, Halvorsen EM, Miller SW, Parks JP, Parker WD Jr., Bennett JP Jr., 1997. Elevated reactive oxygen species and antioxidant enzyme activities in animal and cellular models of Parkinson’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1362, 77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CW, Chen YS, Tsay YG, Han CL, Chen YJ, Yang CC, Hung KF, Lin CH, Huang TY, Kao SY, Lee TC, Lo JF, 2018a. ROS-independent ER stress-mediated NRF2 activation promotes warburg effect to maintain stemness-associated properties of cancer-initiating cells. Cell Death Dis 9, 194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang LC, Chiang SK, Chen SE, Yu YL, Chou RH, Chang WC, 2018b. Heme oxygenase-1 mediates BAY 11–7085 induced ferroptosis. Cancer Lett 416, 124–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman V, Sa-Nguanmoo P, Koenig J, Schulz TJ, Grune T, Klaus S, Kipp AP, Ost M, 2018. Partial involvement of Nrf2 in skeletal muscle mitohormesis as an adaptive response to mitochondrial uncoupling. Sci Rep 8, 2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier TJ, Kanaan NM, Kordower JH, 2017. Aging and Parkinson’s disease: Different sides of the same coin? Mov Disord 32, 983–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook AL, Vitale AM, Ravishankar S, Matigian N, Sutherland GT, Shan J, Sutharsan R, Perry C, Silburn PA, Mellick GD, Whitelaw ML, Wells CA, Mackay-Sim A, Wood SA, 2011. NRF2 activation restores disease related metabolic deficiencies in olfactory neurosphere-derived cells from patients with sporadic Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 6, e21907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxhead J, Kurzawa-Akanbi M, Hussain R, Pyle A, Chinnery P, Hudson G, 2016. Somatic mtDNA variation is an important component of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 38, 217 e211–217 e216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGregorio-Rocasolano N, Marti-Sistac O, Gasull T, 2019. Deciphering the Iron Side of Stroke: Neurodegeneration at the Crossroads Between Iron Dyshomeostasis, Excitotoxicity, and Ferroptosis. Front Neurosci 13, 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rey NL, Quiroga-Varela A, Garbayo E, Carballo-Carbajal I, Fernandez-Santiago R, Monje MHG, Trigo-Damas I, Blanco-Prieto MJ, Blesa J, 2018. Advances in Parkinson’s Disease: 200 Years Later. Front Neuroanat 12, 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Camprubi M, Esteras N, Soutar MP, Plun-Favreau H, Abramov AY, 2017. Deficiency of Parkinson’s disease-related gene Fbxo7 is associated with impaired mitochondrial metabolism by PARP activation. Cell Death Differ 24, 120–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desideri E, Martins LM, 2012. Mitochondrial Stress Signalling: HTRA2 and Parkinson’s Disease. Int J Cell Biol 2012, 607929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos D, Moreau C, Devedjian JC, Kluza J, Petrault M, Laloux C, Jonneaux A, Ryckewaert G, Garcon G, Rouaix N, Duhamel A, Jissendi P, Dujardin K, Auger F, Ravasi L, Hopes L, Grolez G, Firdaus W, Sablonniere B, Strubi-Vuillaume I, Zahr N, Destee A, Corvol JC, Poltl D, Leist M, Rose C, Defebvre L, Marchetti P, Cabantchik ZI, Bordet R, 2014. Targeting chelatable iron as a therapeutic modality in Parkinson’s disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 21, 195–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter D, Carter C, Agid F, Agid Y, Lees AJ, Jenner P, Marsden CD, 1986. Lipid peroxidation as cause of nigral cell death in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2, 639–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Meo S, Reed TT, Venditti P, Victor VM, 2016. Role of ROS and RNS Sources in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 1245049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova-Kostova AT, Abramov AY, 2015. The emerging role of Nrf2 in mitochondrial function. Free Radic Biol Med 88, 179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, Morrison B 3rd, Stockwell BR, 2012. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149, 1060–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do Van B, Gouel F, Jonneaux A, Timmerman K, Gele P, Petrault M, Bastide M, Laloux C, Moreau C, Bordet R, Devos D, Devedjian JC, 2016. Ferroptosis, a newly characterized form of cell death in Parkinson’s disease that is regulated by PKC. Neurobiol Dis 94, 169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolle C, Flones I, Nido GS, Miletic H, Osuagwu N, Kristoffersen S, Lilleng PK, Larsen JP, Tysnes OB, Haugarvoll K, Bindoff LA, Tzoulis C, 2016. Defective mitochondrial DNA homeostasis in the substantia nigra in Parkinson disease. Nat Commun 7, 13548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z, Wirth AK, Chen D, Wruck CJ, Rauh M, Buchfelder M, Savaskan N, 2017. Nrf2-Keap1 pathway promotes cell proliferation and diminishes ferroptosis. Oncogenesis 6, e371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Xiong Z, Huang C, Li J, Yang W, Han Y, Paiboonrungruan C, Major MB, Chen KN, Kang X, Chen X, 2019. Hyperactivity of the transcription factor Nrf2 causes metabolic reprogramming in mouse esophagus. J Biol Chem 294, 327–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu MH, Wu CW, Lee YC, Hung CY, Chen IC, Wu KLH, 2018. Nrf2 activation attenuates the early suppression of mitochondrial respiration due to the alpha-synuclein overexpression. Biomed J 41, 169–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Yi J, Zhu J, Minikes AM, Monian P, Thompson CB, Jiang X, 2019. Role of Mitochondria in Ferroptosis. Mol Cell 73, 354–363 e353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaschler MM, Hu F, Feng H, Linkermann A, Min W, Stockwell BR, 2018. Determination of the Subcellular Localization and Mechanism of Action of Ferrostatins in Suppressing Ferroptosis. ACS Chem Biol 13, 1013–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazaryan IG, Thomas B, 2016. The status of Nrf2-based therapeutics: current perspectives and future prospects. Neural Regen Res 11, 1708–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegg ME, Schapira AH, 2016. Mitochondrial dysfunction associated with glucocerebrosidase deficiency. Neurobiol Dis 90, 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Holmstrom KM, Skujat D, Fiesel FC, Rothfuss OC, Kahle PJ, Springer W, 2010. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat Cell Biol 12, 119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokce Cokal B, Yurtdas M, Keskin Guler S, Gunes HN, Atac Ucar C, Aytac B, Durak ZE, Yoldas TK, Durak I, Cubukcu HC, 2017. Serum glutathione peroxidase, xanthine oxidase, and superoxide dismutase activities and malondialdehyde levels in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci 38, 425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald A, Kumar KR, Sue CM, 2019. New insights into the complex role of mitochondria in Parkinson’s disease. Prog Neurobiol 177, 73–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiney SJ, Adlard PA, Bush AI, Finkelstein DI, Ayton S, 2017. Ferroptosis and cell death mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem Int 104, 34–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo YP, Tang BS, Guo JF, 2018. PLA2G6-Associated Neurodegeneration (PLAN): Review of Clinical Phenotypes and Genotypes. Front Neurol 9, 1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi A, Roshan TM, Kahawita TM, Mason AB, Sheftel AD, Ponka P, 2016. Erythroid cell mitochondria receive endosomal iron by a “kiss-and-run” mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta 1863, 2859–2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harusato A, Naito Y, Takagi T, Uchiyama K, Mizushima K, Hirai Y, Higashimura Y, Katada K, Handa O, Ishikawa T, Yagi N, Kokura S, Ichikawa H, Muto A, Igarashi K, Yoshikawa T, 2013. BTB and CNC homolog 1 (Bach1) deficiency ameliorates TNBS colitis in mice: role of M2 macrophages and heme oxygenase-1. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19, 740–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey CJ, Thimmulappa RK, Singh A, Blake DJ, Ling G, Wakabayashi N, Fujii J, Myers A, Biswal S, 2009. Nrf2-regulated glutathione recycling independent of biosynthesis is critical for cell survival during oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 46, 443–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi G, Jasoliya M, Sahdeo S, Sacca F, Pane C, Filla A, Marsili A, Puorro G, Lanzillo R, Brescia Morra V, Cortopassi G, 2017. Dimethyl fumarate mediates Nrf2-dependent mitochondrial biogenesis in mice and humans. Hum Mol Genet 26, 2864–2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JD, Dinkova-Kostova AT, 2017. Epigenetic Control of NRF2-Directed Cellular Antioxidant Status in Dictating Life-Death Decisions. Mol Cell 68, 5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkila RE, Hess A, Duvoisin RC, 1985. Dopaminergic neurotoxicity of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) in the mouse: relationships between monoamine oxidase, MPTP metabolism and neurotoxicity. Life Sci 36, 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintze KJ, Katoh Y, Igarashi K, Theil EC, 2007. Bach1 repression of ferritin and thioredoxin reductase1 is heme-sensitive in cells and in vitro and coordinates expression with heme oxygenase1, beta-globin, and NADP(H) quinone (oxido) reductase1. J Biol Chem 282, 34365–34371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch EC, 2009. Iron transport in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 15 Suppl 3, S209–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmstrom KM, Baird L, Zhang Y, Hargreaves I, Chalasani A, Land JM, Stanyer L, Yamamoto M, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Abramov AY, 2013. Nrf2 impacts cellular bioenergetics by controlling substrate availability for mitochondrial respiration. Biol Open 2, 761–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh JY, Liu JH, Yang PC, Lin CL, Liu GY, Hung HC, 2014. Fumarate analogs act as allosteric inhibitors of the human mitochondrial NAD(P)+-dependent malic enzyme. PLoS One 9, e98385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Wu BP, Nguyen D, Liu YT, Marani M, Hench J, Benit P, Kozjak-Pavlovic V, Rustin P, Frank S, Narendra DP, 2018. CHCHD2 accumulates in distressed mitochondria and facilitates oligomerization of CHCHD10. Hum Mol Genet 27, 3881–3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung SY, Liou HC, Kang KH, Wu RM, Wen CC, Fu WM, 2008. Overexpression of heme oxygenase-1 protects dopaminergic neurons against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced neurotoxicity. Mol Pharmacol 74, 1564–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Meng H, Shiba-Fukushima K, Hattori N, 2019. Twin CHCH Proteins, CHCHD2, and CHCHD10: Key Molecules of Parkinson’s Disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and Frontotemporal Dementia. Int J Mol Sci 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A, Lamark T, Sjottem E, Larsen KB, Awuh JA, Overvatn A, McMahon M, Hayes JD, Johansen T, 2010. p62/SQSTM1 is a target gene for transcription factor NRF2 and creates a positive feedback loop by inducing antioxidant response element-driven gene transcription. J Biol Chem 285, 22576–22591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Orgaz A, Kvainickas A, Nagele H, Denner J, Eimer S, Dengjel J, Steinberg F, 2018. Control of RAB7 activity and localization through the retromer-TBC1D5 complex enables RAB7-dependent mitophagy. EMBO J 37, 235–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Wang J, Wang C, Lian D, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Lv M, Li Y, Huang Z, Cheng X, Fei G, Liu K, Zeng M, Zhong C, 2019. Combined Visualization of Nigrosome-1 and Neuromelanin in the Substantia Nigra Using 3T MRI for the Differential Diagnosis of Essential Tremor and de novo Parkinson’s Disease. Front Neurol 10, 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing X, Shi H, Zhang C, Ren M, Han M, Wei X, Zhang X, Lou H, 2015. Dimethyl fumarate attenuates 6-OHDA-induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells and in animal model of Parkinson’s disease by enhancing Nrf2 activity. Neuroscience 286, 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaidery NA, Banerjee R, Yang L, Smirnova NA, Hushpulian DM, Liby KT, Williams CR, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW, Ratan RR, Sporn MB, Beal MF, Gazaryan IG, Thomas B, 2013. Targeting Nrf2-mediated gene transcription by extremely potent synthetic triterpenoids attenuate dopaminergic neurotoxicity in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 18, 139–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattoor AJ, Pothineni NVK, Palagiri D, Mehta JL, 2017. Oxidative Stress in Atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep 19, 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerins MJ, Ooi A, 2018. The Roles of NRF2 in Modulating Cellular Iron Homeostasis. Antioxid Redox Signal 29, 1756–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH, Son JM, Benayoun BA, Lee C, 2018. The Mitochondrial-Encoded Peptide MOTS-c Translocates to the Nucleus to Regulate Nuclear Gene Expression in Response to Metabolic Stress. Cell Metab 28, 516–524 e517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Kurokawa H, Waguri S, Taguchi K, Kobayashi A, Ichimura Y, Sou YS, Ueno I, Sakamoto A, Tong KI, Kim M, Nishito Y, Iemura S, Natsume T, Ueno T, Kominami E, Motohashi H, Tanaka K, Yamamoto M, 2010. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat Cell Biol 12, 213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo K, Ishigaki Y, Gao J, Yamada T, Imai J, Sawada S, Muto A, Oka Y, Igarashi K, Katagiri H, 2013. Bach1 deficiency protects pancreatic beta-cells from oxidative stress injury. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 305, E641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y, Trabucco SE, Zhang H, 2014. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and the mitochondria theory of aging. Interdiscip Top Gerontol 39, 86–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubben N, Zhang W, Wang L, Voss TC, Yang J, Qu J, Liu GH, Misteli T, 2016. Repression of the Antioxidant NRF2 Pathway in Premature Aging. Cell 165, 1361–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon MY, Park E, Lee SJ, Chung SW, 2015. Heme oxygenase-1 accelerates erastin-induced ferroptotic cell death. Oncotarget 6, 24393–24403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labadorf A, Choi SH, Myers RH, 2017. Evidence for a Pan-Neurodegenerative Disease Response in Huntington’s and Parkinson’s Disease Expression Profiles. Front Mol Neurosci 10, 430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston JW, Ballard P, Tetrud JW, Irwin I, 1983. Chronic Parkinsonism in humans due to a product of meperidine-analog synthesis. Science 219, 979–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastres-Becker I, Garcia-Yague AJ, Scannevin RH, Casarejos MJ, Kugler S, Rabano A, Cuadrado A, 2016. Repurposing the NRF2 Activator Dimethyl Fumarate as Therapy Against Synucleinopathy in Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 25, 61–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]