Abstract

The biodegradation of acetochlor in solution and soil and improvements in the growth of maize seedlings by a phosphate-solubilizing bacterial strain were investigated in this research. The strain Bacillus sp. ACD-9 optimally degraded acetochlor at pH 6.0 and 42 °C in solution. And acetochlor with an initial concentration of 30 mg/L was efficiently (> 60%) degraded by the strain after 2 days in solution. Acetochlor biodegradation and the resulting beneficial products were also identified by LC–MS, and the probable degradation products of acetochlor and two kinds of plant growth hormones, namely, 2-chloro-N-(2-methyl-6-ethylphenyl) acetamide (CMEPA), indoleacetic acid (IAA), and zeatin, were detected from the fermentation broth of strain ACD-9. The effects of the strain on the growth and acetochlor accumulation of maize seedlings were also analyzed in laboratory-scale pot experiments. Inoculation of the strain in soil could significantly improve growth (> 9.4%) and phosphorus uptake (> 14.8%) and decrease the accumulation (> 70%) and toxic effects of acetochlor on seedlings. Taking the results together, strain ACD-9 may be useful in the degradation of acetochlor in soil and promotion of the growth and phosphorus uptake of maize.

Keywords: Acetochlor, Biological degradation, Phosphate-solublizing bacteria, Beneficial effects

Introduction

Acetochlor [2-chloro-N-(ethoxymethyl)-N-(2-ethyl-6-methylphenyl) acetamide] is a chloroacetanilide herbicide often used to control a large number of annual grasses and some broad-leaf weeds. It is applied during the pre-emergence and pre-planting stages of various crops, including cabbage, cotton, maize, potato, and sunflower, and vineyards (Erguven 2018); moreover, it is widely used in China and many other parts of the world.

The biodegradation half-life of acetochlor is fairly low, ranging from 8 to 100 days in the natural environment; indeed, only approximately 33% of acetochlor could be degraded after 1 month when applied at a concentration of 10 mg acetochlor/kg soil (Luo et al. 2015). Biochars aged in the soil may increase the bioaccumulation of acetochlor in plants such as maize (Li et al. 2018). Because the use of a number of toxic pesticides, such as paraquat, has been prohibited, acetochlor has been increasingly applied to prevent infestation of unwanted plants. Such application has resulted in the frequent detection of acetochlor in soil and water, and the herbicide has been reported to be associated with increased risk of lung cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, melanoma, and acute genital edema (Lerro et al. 2015; Tian et al. 2019). Acetochlor may also cause brain abnormalities in zebrafish embryos, influence the locomotor behavior of zebrafish larvae, and induce neurotoxicity in the early development stages of zebrafish (Wang et al. 2019).

Acetochlor at concentrations of 0.03–709.37 mg/kg has been detected in riparian soil samples collected from northeastern China, and residual concentrations in soils could reach 54.76 mg/kg in maize land (Sun et al. 2011, 2013; Li et al. 2018). Biochars obtained from weed, wood, and rice hulls have been found to extend the persistence of acetochlor in soil; in particular, biochars aged in soil for long periods of time can increase the bioaccumulation of acetochlor in plants (Li et al. 2018). Therefore, acetochlor could pose serious environmental risks. The herbicide has been listed as a human B2 carcinogen by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (Xie et al. 2018).

Several methods, such as chemical precipitation, electrocoagulation, adsorption, and photocatalytic degradation technology, have been used to remove or degrade acetochlor (Fu et al. 2019). Given its desirable results, economic viability, complete degradation, and mineralization, microbial degradation technology has become an important, efficient, and environment-friendly method of treating acetochlor (Xu et al. 2008; Carboneras et al. 2017; Wu et al. 2019). The characteristics of some microbial communities and bacterial strains that could degrade acetochlor have been previously evaluated (Xu et al. 2008; Luo et al. 2015; Wu et al. 2019). However, to date, little knowledge on acetochlor-degrading bacterial strains that can also promote plant growth by solubilizing phosphates and secreting plant growth hormones has been published. Therefore, the objectives of this study are to (1) isolate and identify the acetochlor-degrading bacterial strain, (2) qualify the biodegradation products of acetochlor by bacteria, and (3) investigate the effects of acetochlor-degrading bacteria on the growth of maize seedlings.

Materials and methods

Acetochlor degradation strain and chemicals

The bacterial strain ACD-9 isolated from the soil of long term applied herbicide acetochlor using mineral salt medium (MSM) agar plates could use acetochlor as the sole carbon source for growth. Based on the sequence of its 16S rRNA genes, ACD-9 was identified as a strain of the genus Bacillus (Wang et al. 2018b).

MSM (pH 7.2) was composed of 1 g/L NaCl, 1 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 0.5 g/L KH2PO4, 1.5 g/L K2HPO4, 0.2 g/L MgSO4 7H2O, 1 mL of trace element solution (containing 0.13 g/L MnSO4·H2O, 0.23 g/L ZnC12, 0.03 g/L CuSO4·H2O, 0.42 g/L CoC12·6H2O, 0.15 g/L NaMoO4·2H2O, and 0.05 g/L A1C13·6H2O), and 0.02% yeast extract.

Menkina medium (10 g/L glucose, 10 g/L Ca3(PO4)2, 0.3 g/L KCl, 0.5 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 0.05 g/L MnSO4·4H2O, 0.3 g/L NaCl; pH 7.0; Niewolak 1980) was used for the phosphate-solubilizing assay of strain ACD-9.

Luria–Bertani (LB) medium was used to activate cells of strain ACD-9. HPLC-grade acetochlor (chemical purity > 99%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, China). The acetochlor used in the pot experiments was obtained from Qiaochang Modern Agriculture Company (Shandong Province, China). Other HPLC-grade solvents were obtained from Beihua Fine Chemicals Co. (Beijing, China). Maize seeds (Zea mays L.) were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Beijing, China).

Kinetics of acetochlor degradation by strain ACD-9 in MSM solution

The kinetics of acetochlor degradation by strain ACD-9 was evaluated in liquid MSM. First, strain ACD-9 was pre-cultivated and shaken in liquid LB medium for 12 h. The cells were then harvested from 2 mL of the pre-culture (OD600 = 0.6) by centrifugation at 10,000 r/min for 10 min and rinsed twice with sterile distilled water. The cells were added to 100 mL of liquid MSM solution with an initial acetochlor concentration of 30 mg/L and inoculation amount of 0.5% in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask. The culture was grown at 37 °C with shaking (180 r/min). The OD600 of one of the 3 mL samples was examined periodically (8 h intervals) by a US–Vis spectrophotometer (Unico, Shanghai) to measure bacterial growth, and another sample was centrifuged to measure its acetochlor content. After filtering through a 0.22 µm membrane filter, the acetochlor concentration in the supernatant was analyzedusing a 2.1 mm × 50 mm Acquity UPLC Ben C18 1.7 µm HPLC column fitted to an Agilent Series 1260 HPLC system.

Characteristics of acetochlor degradation by Bacillus sp. ACD-9

Single-factor experiments were performed to examine the characteristics of acetochlor degradation by Bacillus sp. ACD-9. Solutions of acetochlor with initial concentrations of 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100 mg/L were prepared in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL of liquid MSM. The effects of pH on the characteristics of acetochlor degradation were determined at initial pH of 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, and 9.0; Bacillus sp. ACD-9 inoculation quantities of 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 5%, 8%, and 10%; and culture temperatures of 4, 15, 30, 37, 42, and 46 °C. In all single-factor experiments, strain ACD-9 was pre-cultivated and cultured according to the procedures and conditions described above. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate, and the necessary control samples were included. Exactly 5 mL of growth medium was analyzed at suitable times to determine OD600 and the concentration of acetochlor via the HPLC method.

Beneficial effects of Bacillus sp. ACD-9 on the maize growth

Pot experiments were conducted in a greenhouse to evaluate the beneficial effects of strain ACD-9 on the growth of maize. A stock solution (10 µg/mL) of acetochlor was prepared in sterile water. Moist soil (200 g natural dry weight equivalent) was treated with acetochlor stock solution to achieve a final concentration of 1.0 mg acetochlor/kg soil and placed in plastic flowerpots measuring 6.5 cm in diameter and 7.5 cm in depth. Cells of Bacillus sp. ACD-9 were cleaned twice, diluted with sterile water, grown to the exponential phase, and then collected and centrifuged to prepare microbial agents. The cell count of the microbial agent was 107 CFU/mL. Thirty-six maize seeds were placed in moist filter paper for germination. Then, the maize seedlings were transferred to the flowerpots and grown under an illuminated incubator with 16 h of light at 23 °C and 8 h of darkness at 15 °C. Each treatment had three replicates. The experiment included the following treatments: (i) un-inoculated (blank control), (ii) 10 mL of microbial agents, (iii) 1 mg acetochlor/kg soil, and (iv) 10 mL of microbial agents and 1 mg acetochlor/kg soil.

After 20 days of incubation, the maize seedlings were carefully removed from the flowerpots. Under-ground (roots) and above-ground (stems and leaves) parts were separated after washing with sterile water, naturally dried, weighed, and stored at − 20 °C for chemical analysis. The acetochlor residues were extracted from the plant samples and analyzed as described by the National Corresponding Standard of China (GB 23200.57-2016). The effect of strain ACD-9 on phosphate solubilization was also analyzed. Dried plant tissues were powdered, and total phosphorus (TP) was determined by digesting the samples with HNO3–HClO4 (APHA 2005). Samples where then assayed by the ascorbic acid/molybdenum blue colorimetric method (Murphy and Riley 1962; APHA 2005).

Analysis of the products formed after acetochlor degradation by Bacillus sp. ACD-9

Strain ACD-9 was cultured according to the procedures described above to determine their acetochlor-degrading kinetics. At a suitable time when the degrading rate nears the maximum at 48 h, 5 mL of growth medium was obtained and centrifuged for metabolite detection. The supernatant (20 µL) was filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane filter and quantitatively analyzed for 2-chloro-N-(2-methyl-6-ethylphenyl) acetamide (CMEPA), the main metabolite of acetochlor during biodegradation (Ye et al. 2002), by LC–MS.

Metabolites were eluted from the column using a gradient mobile phase composed of water and acetonitrile at 1.0 mL/min. Elution began with 50% water. Thereafter, the linear gradient was ramped to 90% acetonitrile over 3.5 min, maintained for 6.5 min, and then returned to the initial gradient. The wavelength of the absorbance detector and injection volume were set to 215 nm and 20 µL, respectively. The metabolites were detected with a Shimadzu PR-LCMS-2020 spectrometer (Japan) operating in ESI mode with a HESI probe for positive and negative data acquisition.

Data analysis

One-way analysis of variance and t test were performed to determine differences among treatments, and significance was set to p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 22.0.

Results and discussion

Kinetics of acetochlor degradation by strain ACD-9 in MSM solution

Comparisons of the growth (OD600) and degradation kinetics of Bacillus sp. ACD-9 in solution containing 30 mg/L acetochlor and the control (Fig. 1) revealed that significant acetochlor degradation occurs within 16 h after incubation, which corresponds to the lag phase of cell growth. Thereafter, although the degradation rate decreased from 16 to 48 h, which is related to the logarithmic phase of growth, the peak acetochlor degradation rate appeared in the late logarithmic phase to the stationary phase after 48 h. When growth ceased (after 56 h), the acetochlor concentration in the medium slightly changed, which indicates that the herbicide may transform into other metabolites through the cells of Bacillus sp. ACD-9. This kinetic pattern is similar to that of a previously reported acetochlor-degrading strain (Luo et al. 2015).

Fig. 1.

Kinetics of acetochlor degradation by strain ACD-9

Characteristics of acetochlor degradation by Bacillus sp. ACD-9

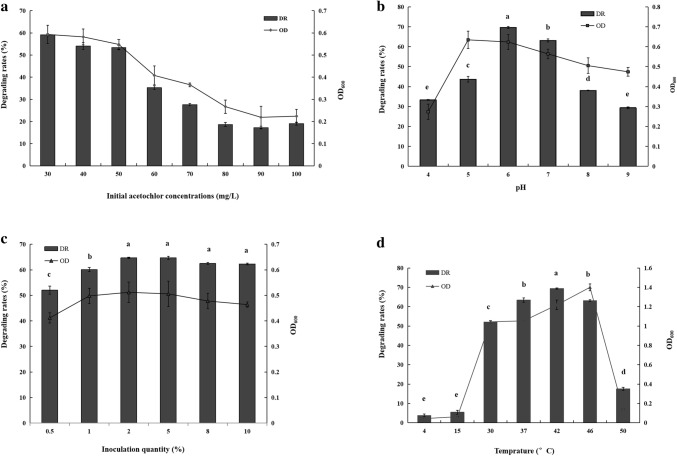

As shown in Fig. 2a, when the initial concentration of acetochlor was 30 mg/L, approximately 59.2% of the herbicide could be degraded by strain ACD-9 after 48 h. At initial acetochlor concentrations of 40–100 mg/L, the degradation rates ranged from 19.1 to 54.7%. When the acetochlor concentration was higher than 80 mg/L, the degradation rate and OD600 decreased significantly. Hence, the strain may be unable to tolerate the toxicity of acetochlor at higher concentrations. The presence of acetochlor in the soil also exerts a negative effect on some bacterial species, such as ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (Li et al. 2008); it may inhibit the population of soil bacteria and respiration of soil microbes to varying degrees and affect nutrient cycling processes (Cai et al. 2007).

Fig. 2.

Effects of initial concentration (a), pH (b), inoculation quantity (c) and temperature (d) on acetochlor degradation by strain ACD-9. aAbbreviations: DR degrading rates, OD OD600.. bSignificant p values (α = 0.05) are indicated by different letters (a–e) above the columns

The data show that the highest degradation rates (> 60%) of strain ACD-9 could be obtained in solution with an initial acetochlor concentration of 30 mg/L. The relative low degradation rate of this strain may be attributed to several factors. According to the results of a previous study, addition of glucose (5 g/L) and yeast extract (1 g/L) to the solution greatly improves the degradation rate of 50 mg/L acetochlor from 50% (in the treatment without glucose and yeast extract) to 90%, and the OD600 could peak at 2.0 (Luo et al. 2015). So the nutrient conditions, especially the different types of carbon and nitrogen sources, could affect the acetochlor degradation rate of the same bacterial strain. In addition, the species of the bacteria is also an important factor. Some bacteria, such as Rhodopseudomonas capsulate, could degrade nearly 100% acetochlor at initial concentrations of 500–2000 mg/L. This ability may be due to the unique features of this kind of photosynthetic bacteria with good tolerance to herbicides and toxic substances (Wu et al. 2019). Members of the genus of Sphingomonas usually played important roles in the biodegradation of organic pollutants like chloroacetamide herbicides. Chen et al (2015) isolated a strain of Sphingomonas chloroacetimidivorans could degrade 72.2% of acetochlor when the inoculum was 5% (v/v) and the initial concentration was 100 mg/L after incubation for 7 days at 30 °C. Hence, these bacteria may be suitable for the treatment of wastewater with high acetochlor concentrations. Acetochlor is commonly applied to maize farmland at the recommended rate of 2.2 kg/ha (Oliveira et al. 2013), 1.05–1.47 kg ai/ha (Norsworthy et al. 2019) or 0.52–0.98 mg/kg (Su et al. 2019). Hence, the acetochlor concentration in the natural environment is relatively low. The capacity of strain ACD-9 to degrade acetochlor (with degradation rate of > 60% in the acetochlor concentration of 30 mg/L) can meet the needs of common practical applications.

As shown in Fig. 2b, the cells of strain ACD-9 could degrade over 69% acetochlor in the solution after 48 h at pH 6.0; the degradation rates were less than 40% at pH of 4.0, 8.0, and 9.0. Maximum OD600 values were observed in solutions with pH of 5.0 and 6.0. Hence, the degradation of acetochlor by strain ACD-9 is better in neutral and partially acidic environments than in highly acidic or basic media. These results may be related to the properties of the strain’s degrading enzymes, which appear to be more active at pH 6.0 than at other pH. The effects of inoculation quantity and temperature on the degradation of acetochlor are shown in Fig. 2c, d. The degradation rates of acetochlor at inoculation quantities ranging from 2 to 10% exceeded 62%, and differences among treatments were not significant. Thus, the low degradation rate in the previous experiment could be related to the low inoculation quantity of 0.5%. The degradation rate of acetochlor was highest at 42 °C and exceeded 60% at 37–46 °C. Several reported strains exhibit optimum acetochlor degradation effects at pH 7.0 and temperatures of approximately 30 and 37 °C (Xu et al. 2013; Luo et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2018a). Hence, in the present study, good tolerance to a high temperature range (40–46 °C) and neutral to partially acid conditions (pH 5.0–7.0) is a major advantage of strain ACD-9.

Colonies of strain ACD-9 could grow rapidly in Menkina agar plates with Ca3(PO4)2 as the sole phosphorus source. When cultured in liquid Menkina medium, the dissolved phosphorus concentration in the supernatant could reach 215 µg/mL after 7 days. Compared with the phosphate-solubilizing activities of the isolated strains, which ranged from 8 to 610.33 µg/mL (Prakash and Arora 2019), strain ACD-9 showed obvious capacity for phosphate solubilization. Hence, it could also be considered a strain of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria. To evaluate whether the phosphate-solubilizing characteristics of the strain and its promotory effects on seedling growth are affected by acetochlor, pot experiments were also conducted.

Beneficial effects of Bacillus sp. ACD-9 on maize growth

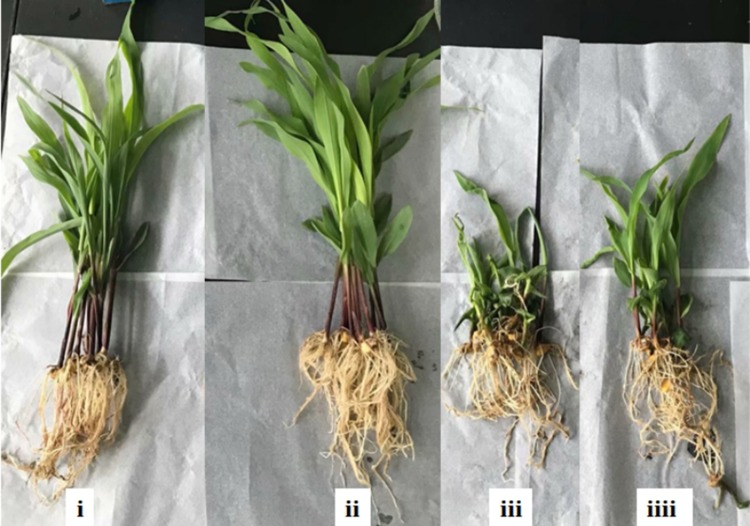

The degradation of acetochlor by strain ACD-9 in farmland soil was verified by pot experiments. As shown in Fig. 3 and Table 1, when strain ACD-9 was inoculated alone (treatment ii), the growth of maize seedlings was obviously better than that of the blank control (treatment i), and dry and wet plant weights and root and shoot lengths increased by 29.21%, 49.34%, 9.44%, and 16.68%, respectively, relative to the blank control. This finding may be attributed to the phosphate-solubilizing and other beneficial effects of the inoculated strain. When acetochlor was applied alone, the leaves and roots of the maize seedlings curled and shrank (as shown in Fig. 3), which may be due to the close contact of maize seeds with the herbicide in the soil (treatment iii). Or as reported by Norsworthy et al (2019) and Chauhan and Johnson (2011), the severe phytotoxicity may be caused by high soil moisture that could increase the absorption and translocation of acetochlor. After addition of the degrading strain, however, the toxic effect was clearly attenuated (treatment iv). And the accumulations of acetochlor in the maize seedlings in treatment iii and iv were also detected by standard method. As shown in Table 1, the acetochlor content in the maize seedling samples were 0.72 and 0.2 mg/kg, respectively, after 20 days of growth. Indicating that the inoculation of strain ACD-9 was able to detoxify acetochlor in the plant.

Fig. 3.

Photos of maize plant in the pot experiments of different treatments after 14 days (i, blank control; ii, added with cells of strain ACD-9 only; iii, added with acetochlor of 1 mg/kg soil; iv, added with acetochlor of 1 mg/kg soil and cells of strain ACD-9)

Table 1.

Growth features, acetochlor content and total phosphorus content of maize seedling under different treatments

| Treatments | Different treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (i) | ACD-9 (ii) | Acetochlor (iii) | Acetochlor and ACD-9 (iiii) | |

| Root length (cm) | 13.13 ± 0.12b | 14.37 ± 0.11a | 10.7 ± 0.26d | 11.8 ± 0.23c |

| Stem length (cm) | 11.62 ± 0.17b | 13.57 ± 0.34a | 3.75 ± 0.13d | 6.06 ± 0.16c |

| Wet weight (g) | 13.74 ± 0.21b | 20.52 ± 0.46a | 7.32 ± 0.25d | 9.48 ± 0.16c |

| Dry weight (g) | 2.91 ± 0.11b | 3.76 ± 0.09a | 1.47 ± 0.06d | 2.07 ± 0.18c |

| Acetochlor content (mg/kg) | – | – | 0.72 ± 0.17a | 0.2 ± 0.06b |

| TP content (mg/g) | 3.79 ± 0.23c | 5.25 ± 0.31a | 3.48 ± 0.34d | 4.45 ± 0.16b |

Data are the mean of three replicates ± standard error of means

Means, followed by the different letters (a–d) in a line are significantly different (p < 0.05) by Duncan’s multivariate test (DMRT)

– Not detected

Dry and wet plant weights and root and shoot lengths in treatment iv increased by 40.82%, 29.51%, 16.78%, and 61.56%, respectively, compared with those in treatment iii. These findings may be attributed to the acetochlor degradation, phosphate solubilization, and other beneficial effects of strain ACD-9. According to the previous reports, increases in plant biomass (wet weight) between 15 and 43% compared with the control after inoculation of other plants with phosphate-solubilizing bacteria (Hameeda et al. 2008; Anzuaya et al. 2017). In addtion, as phosphate-solubilizing bacterial strains, the abilities of some were nearly completely suppressed when they are exposed to the pool of pesticides used for maize (Anzuaya et al. 2017). While in the present study, strain ACD-9 still promoted phosphorus uptake by approximately 14.83% in the presence of 1 mg/kg soil acetochlor compared with the blank control. Other acetochlor-degrading strains, such as Sphingomonas sp. DC-6 (Li 2016; Wang et al. 2018a), can also significantly reduce the harmful effects of acetochlor on maize. The degradation rate of acetochlor (1 mg/kg soil) by it could reach 89.29% within 15 days, but no significant growth-promoting effect on maize growth was observed.

So inoculation of strain ACD-9 in the soil could take several beneficial effects like promoting growth, phosphate uptaking and decreasing toxicity of acetochlor to the maize plant.

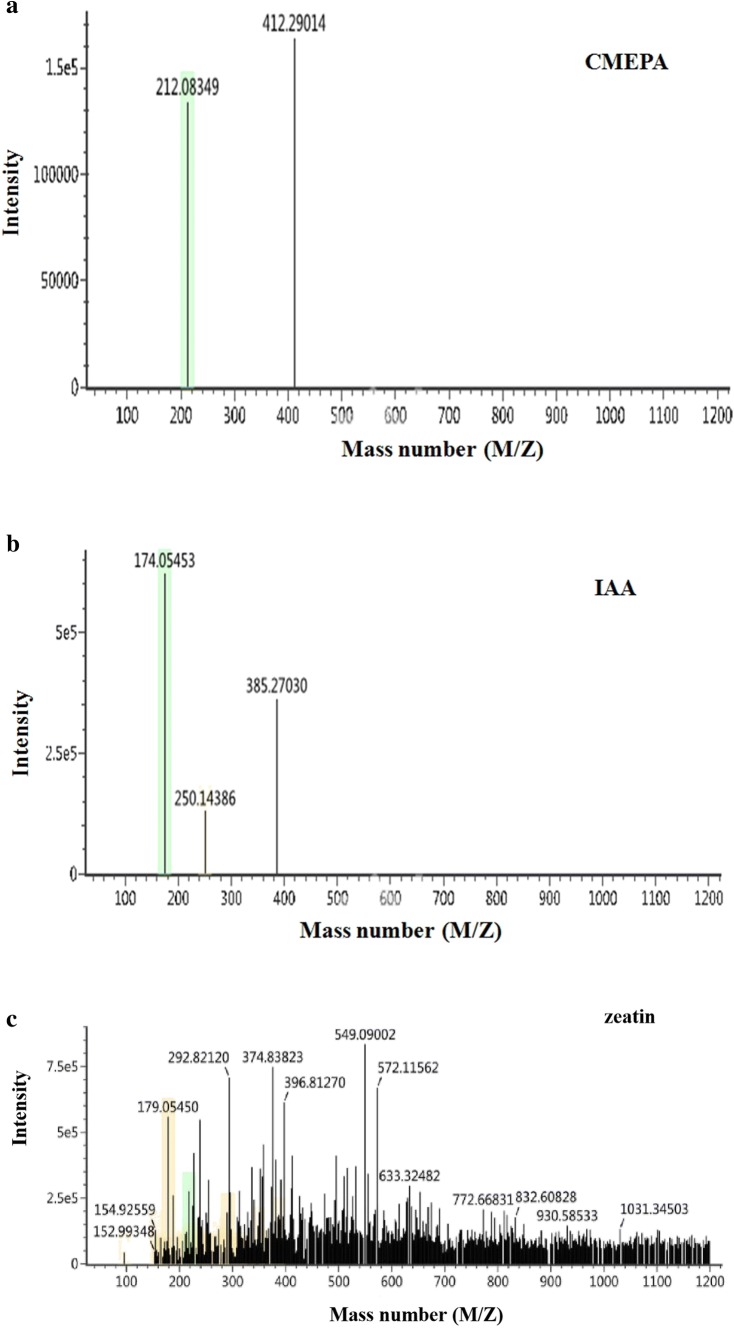

Analysis of the products of acetochlor degradation by Bacillus sp. ACD-9

The transformation of acetochlor is always accompanied by the formation of metabolites, and CMEPA has been reported to be the main metabolite of acetochlor degraded by microbes (Xu et al. 2008; Hou et al. 2014). The biodegradation products of acetochlor by strain ACD-9 were detected at 48 h by LC–MS. As shown in Fig. 4a, CMEPA (m/z = 212.08) is one of the probable acetochlor metabolites of strain ACD-9. However, another reported major metabolite, 2-methyl-6-ethylaniline (Hou et al. 2014), was not detected in our study; this finding may be related to the properties of different microbial strains. The results in Fig. 3b, c indicate that the probable metabolites in the fermentation broth are IAA and zeatin, respectively. Thus, besides its phosphate-solubilizing and acetochlor-degrading properties, strain ACD-9 may also promote the growth of maize by secreting plant hormones, such as IAA and zeatin. IAA is a plant hormone that can promote the development of the root system of host plants (Abedinzadeh et al. 2019). IAA production by several phosphate-solubilizing bacterial strains has been previously reported (Prakash and Arora 2019; Srivastava et al. 2019). Zeatin, a cytokinin of the adenine family, plays an important role in cell division and plant growth (Liu et al. 2013). Reports on the secretion of zeatin by phosphate-solubilizing bacteria are rare.

Fig. 4.

Probable metabolites (a, CMEPA; b, IAA; c, zeatin) of acetochlor degradation by strain ACD-9 detected by LC–MS method

Conclusions

The optimal conditions for acetochlor degradation by strain ACD-9 include pH 6.0, 42 °C, initial acetochlor concentration of 30 mg/L, inoculation quantity of 2%, and shaking rate of 180 r/min. The probable degradation products of acetochlor and plant growth hormones are CMEPA, IAA, and zeatin. Inoculation of the strain in soil could significantly improve dry and wet plant weights and root and shoot lengths, increase total phosphorus contents, and decrease the accumulation and toxicity of acetochlor in maize seedlings. Therefore, strain ACD-9 demonstrates potential in soil remediation by degrading acetochlor and promoting maize growth and phosphorus uptake.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the projects of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31400103 and No. 31370147) and Young Key Teachers Training Program of Henan University of Technology.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors hereby declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abedinzadeh M, Etesami H, Alikhani HA. Characterization of rhizosphere and endophytic bacteria from roots of maize (Zea mays L.) plant irrigated with wastewater with biotechnological potential in agriculture. Biotechnol Rep. 2019;21:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2019.e00305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association . Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 21. Washington: American Public Health Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Anzuaya MS, Ciancio MGR, Ludue˜na LM, Angelini JG, Barros JG, Pastor N, Taurian T. Growth promotion of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) and maize (Zea mays L.) plants by single and mixed cultures of efficient phosphate solubilizing bacteria that are tolerant to abiotic stress and pesticides. Microbiol Res. 2017;199:98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Sheng G, Liu W. Degradation and detoxification of acetochlor in soils treated by organic and thiosulfate amendments. Chemosphere. 2007;66:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carboneras B, Villaseñor J, Fernandez-Morales FJ. Equationling aerobic biodegradation of atrazine and 2,4-dichlorophenoxy acetic acid by mixed-cultures. Bioresour Technol. 2017;243:1044–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan BS, Johnson DE. Growth response of direct-seeded rice to oxadiazon and bispyribac-sodium in aerobic and saturated soil. Weed Sci. 2011;59:119–122. doi: 10.1614/WS-D-10-00075.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Chen Q, Wang GX, Ni HY, He J, Yan X, Gu JG, Li SP. Sphingomonas chloroacetimidivorans sp. nov., a chloroacetamide herbicide-degrading bacterium isolated from activated sludge. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek Van Leeuwenhoek. 2015;108:703–710. doi: 10.1007/s10482-015-0526-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erguven GO. Comparison of some soil fungi in bioremediation of herbicide acetochlor under agitated culture media. B Environ Contam Tox. 2018;100:570–575. doi: 10.1007/s00128-018-2280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Li Y, Hu JS, Li S, Qin GW. Photocatalytic degradation of acetochlor by α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles with different morphologies in aqueous solution system. Optik. 2019;178:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijleo.2018.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hameeda B, Harini G, Rupela OP, Wani SP, Reddy G. Growth promotion of maize by phosphate solubilizing bacteria isolated from composts and macrofauna. Microbio Res. 2008;163:234–242. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, Dong WL, Wang F, Li JQ, Shen WJ, Li YY, Cui ZL. Degradation of acetochlor by a bacterial consortium of Rhodococcus sp. T3–1, Delftia sp.T3-6 and Sphingobium sp. MEA3-1. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2014;59:35–42. doi: 10.1111/lam.12242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerro CC, Koutros S, Andreotti G, Hines CJ, Blair A, Lubin J, Ma XM, Zhang YW, Beane Freeman LE. Use of acetochlor and cancer incidence in the agricultural health study. Int J Canc. 2015;137:1167–1175. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q (2016) Study on the mechanism of acetochlor’s biodegradation by Sphingomonas sp. DC-6 in maize rhizosphere. Dissertation, Nanjing Agriculture University

- Li XY, Zhang HW, Wu MN, Su ZC, Zhang CG. Impact of acetochlor on ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in microcosm soils. J Environ Sci. 2008;20:1126–1131. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(08)62159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liu XG, Wu XH, Dong FS, Xu J, Pan XL, Zheng YQ. Effects of biochars on the fate of acetochlor in soil and on its uptake on maize seeding. Environ Pollut. 2018;241:710–719. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XP, Bereźniak T, Panek JJ, Jezierska-Mazzarello A. Theoretical study of zeatin—A plant hormone and potential drug for neural diseases-On the basis of DFT, MP2 and target docking. Chem Phys Lett. 2013;557:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2012.12.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Gu QY, Chen WT, Zhu XC, Duan ZB, Yu XB. Biodegradation of Acetochlor by a newly isolated Pseudomonas strain. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2015;176:636–644. doi: 10.1007/s12010-015-1601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J, Riley JP. A modified single-solution method for determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal Chim Acta. 1962;27:31–36. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)88444-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niewolak S. Occurrence of microorganism in fertilized lakes II. Lecithin-mineralizing microorganisms. Pol Arch Hydrobiol. 1980;27:53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Norsworthy JK, Fogleman M, Barber T, Gbur EE. Evaluation of acetochlor-containing herbicide programs in imidazolinoneand quizalofop-resistant rice. Crop Prot. 2019;122:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2019.04.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira RS, Koskinen WC, Graff CD, Anderson JL, Mulla DJ, Nater EA, Alonso DG. Acetochlor persistence in surface and subsurface soil samples. Water Air Soil Poll. 2013;224:1747. doi: 10.1007/s11270-013-1747-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash J, Arora NK. Phosphate-solubilizing Bacillus sp. enhances growth, phosphorus uptake and oil yield of Mentha arvensis L. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:126. doi: 10.1007/s13205-019-1660-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava AK, Saxena P, Sharma A, Srivastava R, Jamali H, Bharati AP, Yadav J, Srivastava AK, Kumar M, Chakdar H, Kashyap PL, Saxena AK. Draft genome sequence of a cold-adapted phosphorous-solubilizing Pseudomonas koreensis P2 isolated from Sela Lake, India. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:256. doi: 10.1007/s13205-019-1784-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su XN, Zhang JJ, Liu JT, Zhang N, Ma LY, Lu FF, Chen ZJ, Shi Z, Si WJ, Liu C, Yang H. Biodegrading two pesticide residues in paddy plants and the environment by a genetically engineered approach. J Agric Food Chem. 2019;67:4947–4957. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b07251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Zhou Q, Ren W, Li X, Ren L. Spatial and temporal distribution of acetochlor in sediments and riparian soils of the Songhua River Basin in northeastern China. J Environ Sci. 2011;23:1684–1690. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(10)60595-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Zhou Q, Ren W. Herbicide occurrence in riparian soils and its transporting risk in the Songhua River Basin, China. Agron Sustain Dev. 2013;33:777–785. doi: 10.1007/s13593-013-0154-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian RH, Liu LY, Liang ZW, Guo KM. Acetochlor poisoning presenting as acute genital edema: a case report. Urol Case Rep. 2019;22:47–48. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Jiang K, Zhu ZW, Jiang WK, Yang ZG, Zhu SJ, Qiu JG, Yan X, He J, Qin H. Optimization of fed-batch fermentation and direct spray drying in the preparation of microbial inoculant of acetochlor-degrading strain Sphingomonas sp. DC-6. 3 Biotech. 2018;8:294. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1324-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YL, Li HF, Fu JK, Zhang YY, Qu JH, Tian HL. Isolation, screening and identification of a salt-tolerant acetochlor-degradation bacterium. Tianjin Agri Sci. 2018;24(12):78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wang HL, Meng Z, Zhou LQ, Cao ZG, Liao XJ, Ye RF, Lu HQ. Effects of acetochlor on neurogenesis and behaviour in zebrafish at early developmental stages. Chemosphere. 2019;220:954–964. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.12.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Cao B, Zhang Y, Li WB, Wang YL, Wu Y, Li N. The bio-mitigation of acetochlor in soil using Rhodopseudomonas capsulata in effluent after wastewater treatment. J Soils Sediments. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s11368-018-2201-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie JQ, Zhao L, Liu K, Guo FJ, Liu WP. Enantioselective effects of chiral amide herbicides napropamide, acetochlor and propisochlor: the more efficient R-enantiomer and its environmental friendly. Sci Total Environ. 2018;626:860–866. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Yang M, Dai J, Cao H, Pan C, Qiu X, Xu M. Degradation of acetochlor by four microbial communities. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99(16):7797–7802. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Ding J, Qiu J, Ma Y. Biodegradation of acetochlor by a newly isolated Achromobacter sp. strain D-12s. J Environ Sci Health. 2013;B11:960–966. doi: 10.1080/03601234.2013.816601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye CM, Wang XJ, Zheng HH. Biodegradation of acetanilide herbicides acetochlor and butachlor in soil. J Enron Sci. 2002;4:524–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]