Abstract

Objective:

Characterize the vaginal metabolome of cervical HPV infected and uninfected women.

Design:

Cross-sectional

Setting:

The Center for Health Behavior Research at the University of Maryland School of Public Health.

Sample:

Thirty-nine participants; 13 categorized as HPV-negative and 26 as HPV-positive (any genotype; HPV+), 14 of which were positive with at least one high-risk HPV strain (hrHPV).

Method:

Self-collected mid-vaginal swabs were profiled for bacterial composition by 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing, metabolites by both gas- and liquid-chromatography mass spectrometry, and 37 types of HPV DNA.

Main Outcome Measures:

Metabolite abundances

Results:

Vaginal microbiota clustered into Community State Type (CST) I (L. crispatus-dominated), CST III (L. iners-dominated), and CST IV (low-Lactobacillus, “molecular-BV”). HPV+ women had higher biogenic amine and phospholipid concentrations than HPV-negative women after adjustment for CST and cigarette smoking. Metabolomic profiles of HPV+ and HPV− women differed in stratums of CST. Among women in CST III, HPV+ there were higher concentrations of biogenic amines and glycogen-related metabolites compared to CST III HPV-. In CST IV, HPV+ participants there were lower concentrations of glutathione, glycogen, and phospholipid-related metabolites than CST IV, HPV-. Across all CSTs, women with hrHPV strains had lower concentrations of amino acids, lipids and peptides compared to women who had only low-risk HPV (lrHPV).

Conclusions:

The vaginal metabolome of HPV+ women differed from HPV− women in terms of several metabolites, including biogenic amines, glutathione, and lipid-related metabolites. If the temporal relationship between increased levels of reduced glutathione and oxidized glutathione and HPV incidence/persistence is confirmed in future studies, anti-oxidant therapies may be considered as a non-surgical HPV control intervention.

Keywords: vaginal metabolome, vaginal microbiota, 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing, human papillomavirus

Tweetable abstract:

Metabolomics study: Vaginal microenvironment of HPV+ women may be informative for non-surgical interventions

Introduction:

Cervical cancer is the third most prevalent cancer and the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide.1 Human papillomavirus (HPV) is causatively linked to over 90% of cervical cancer cases.2, 3 Persistent detection of cervical HPV is associated with increased risk for dysplasia4, 5 and cervical malignancy6 but the factors affecting HPV-persistence are not fully understood.

Emerging data suggests an association between cervical HPV infections and the vaginal microenvironment7–19. The vaginal microbiota can be categorized into one of five major community state types (CSTs), four of which are dominated by Lactobacillus spp. (CST I, II, III and V)20. Vaginal Lactobacillus spp. provide broad-spectrum protection by producing lactic acid21, bacteriocins22, 23, and biosurfactants24, and by adherence to the mucosa which forms barriers against pathogenic infection25, 26. CST IV is characterized by a paucity in Lactobacillus, high vaginal pH (>4.5), and high relative abundances of various anaerobic bacteria, including Gardnerella, Prevotella and Atopobium spp.20 These microbial features are also characteristic of bacterial vaginosis (BV), which can be associated with a myriad of symptoms and adverse health outcomes27 leading to the proposal of CST IV being termed “molecular-BV” 28.

Molecular studies have found HPV-positive participants are more likely to present with L. iners-dominated (CST III) or low-Lactobacillus molecular-BV states than HPV-negative women14,17, 29–32. Brotman et al. reported in a small cohort study that L. gasseri-dominated CST II was associated with increased clearance of detectable HPV30. With national surveys estimating that 29% of U.S. women have Nugent BV33, the vaginal microbiota may be a population-level risk factor for HPV that has largely been overlooked.

The vaginal microenvironment also comprises both microbially- and host-produced metabolites that may influence clinical endpoints. While the vaginal metabolome is largely influenced by resident microbiota17, 34–38, prior research has identified metabolites associated with important clinical conditions including BV39, 40, pre-eclampsia41, preterm labor42 and more recently, Ilhan et al. observed an association in the vaginal metabolome between lipids and cervical cancer17. However, the impact of HPV infection remains relatively unexplored. We sought to compare the vaginal metabolome by HPV detection status and vaginal CSTs. These data may provide insight into HPV susceptibility, mechanisms for HPV persistence and lead to the discovery of new targets for intervention.

Methods:

Study population and sample collection:

This is a secondary analysis and the primary study has previously been described29, 34. Forty women were enrolled in a cross-sectional study at the Center for Health Behavior Research at the University of Maryland School of Public Health (UMSPH). Briefly, participants were excluded if they were pregnant, lactating, had the presence of an acute or chronic illness, if they reported use of an antibiotic or antimycotic in the prior 30 days and/or alcohol or drug dependency within the prior 12 months. The final sample size was 39 women. All samples were self-collected, mid-vaginal swabs.

Taxonomic assignment, community state type profiling and HPV detection:

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and Roche 454 pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA gene amplicons (V1–V3) using primers 27F-YM+3 and 543R from the vaginal swabs has been previously described29. Taxonomic assignments were performed using the Ribosomal Database Project Naïve Bayesian Classifier. Lactobacillus species assignments were performed using higher order Markov Chain models and the software speciateIT (speciateIT.sourceforge.net). For each sample, CST classifications were assigned as previously described, using Jensen-Shannon divergence and Ward linkage hierarchical clustering29, 34. The CSTs reflected several Lactobacillus-dominated states I (L. crispatus), CST III (L. iners), and CST IV (low-Lactobacillus, molecular BV) as described by Ravel et al in 201120. DNA extracted from the swabs were tested for 37 types of HPV DNA using the Roche Linear Array HPV Genotyping Test according to manufacturer’s instructions. Samples with any HPV genotype detected were defined as HPV+. Samples with a high-risk HPV genotype (HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 or 68) were defined as hrHPV+, and samples that were negative for all 37 types of HPV were defined as HPV-. HPV+ samples that were not listed as hrHPV were categorized as low-risk HPV (lrHPV) types.

Sample preparation for metabolomics:

Vaginal samples were eluted from swabs using phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and subjected to non-targeted Gas Chromatography (GC) and Liquid Chromatography (LC) mass spectrometry (MS)-based metabolomics conducted by Metabolon Inc. (Durham, NC, USA), as previously described34. Briefly, LC-MS was performed using a Waters ACQUITY ultra-performance liquid ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) and a Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) Orbitrap Elite high resolution/accurate mass spectrometer and samples were run in positive- and negative-ion sense. GC-MS was performed on a Thermo-Finnigan Trace DSQ fast-scanning single-quadrupole mass spectrometer using electron impact ionization, after samples had been dried under vacuum desiccation, and derivatized under dried nitrogen using bistrimethyl-silyl-triflouroacetamide (BSTFA). Raw data was extracted, peaks identified, QC processed, and compounds identified using Metabolon’s proprietary database of reference spectrum. Results were manually curated to ensure that data were accurate and to remove any system artifacts, miss-assignments, and background noise. The provided dataset reflected the relative concentration of 619 metabolites.

Metabolite pre-processing:

Metabolites were excluded from the analysis if they were undetected in ≥ 90% of each biological group (HPV+ vs. HPV-). Remaining “missing” values were assumed to be below the level of detection and were imputed using one-half the minimum value obtained for a given metabolite43–46. The final dataset consisted of the relative concentration of 599 metabolites that were subsequently log-transformed to meet assumptions of linearity, normality, and heterogeneity for linear regression.

Statistical analysis:

CST, demographic and behavioral factors associated with HPV detection status were assessed using Fisher’s exact test (Table S1).

An exploratory non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) was applied to a Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix comprised of the 599 metabolites and 39 individuals. Analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) was used to evaluate the separation of groups and a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was performed to assess the proportion of variation that CST, HPV, hrHPV, and smoking status contributed to the entire vaginal metabolome. The Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix, nMDS, ANOSIM, and PERMANOVA were conducted using the vegan package in R Statistical Software with 10,000 permutations.

Next, we performed linear regression of log-transformed metabolites on HPV and CST after adjustment for a binary variable on current smoking status (Model 1). Smoking was the only covariate as previous work linked it to both HPV and the vaginal metabolome34 and to avoid overfitting the small sample size. We fit another model that included HPV-by-CST interaction terms to determine whether the associations of HPV with metabolites differed by CST (Model 2). Lastly, we fit a simple linear regression model of log-transformed metabolites to assess differences in women with hrHPV and lrHPV (Model 3). Additional covariates were excluded due to the small sample size. Analyses were performed using the lm() function in R Statistical Software and p-values were adjusted using the Storey false discovery rate in the package qvalue.47 Metabolic super- and sub-pathways were identified using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database.

Partial-least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was performed to identify discriminatory metabolites between HPV+ and HPV− status within each stratum of CST. In contrast to a linear model which examines the effect of HPV upon each singular metabolite, this method explores the vaginal metabolome as a whole system. Data were subset by CST and score plots were generated wherein each point represented an individual, and similar groups exhibited clustering, while different groups separated farther apart. PLS-DA models were validated based upon accuracy, variance (R2), and cross-validated using the quality assessment Q2 where values close to 1 indicate reliable models and negative Q2 values indicate possible model over-fitting. Variable importance in projection (VIP) score plots were used to evaluate the discriminatory metabolites. PLS-DA, score plots, and VIP score plots were conducted in the open source software MetaboAnalyst 4.0 (www.metaboanalyst.ca).

We then evaluated the association between microbial phylotypes and HPV detection using linear discriminant analyses effect size (LEfSe) (http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/lefse/)48. LEfSe used the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test to detect significantly differentially abundant phylotypes associated with HPV detection, then performed pairwise Wilcoxon rank-sum tests between each level of CST. Finally, linear discriminant analyses (LDA) were used to estimate the effect size where a larger LDA score indicates a larger effect. The alpha-level for both the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum and the Wilcoxon rank-sum tests was set to 0.01.

Finally, we examined how HPV-associated metabolites related to HPV-associated bacterial species using Spearman’s correlation. P-values were adjusted using the qvalue package. Only correlations with q-values <0.05 were used for cluster analyses. Correlation and cluster analyses was performed and visualized using the functions rcorr, corplot() and Ward’s D2 method function in R Statistical Software.

Results:

Participant characteristics:

Participant characteristics are detailed in Table S1. The average age of participants was 29 years (SD: 9.1; range:19–45). Thirteen participants were HPV-, 12 had lrHPV detected, and 14 were hrHPV+. There was a range of hygiene, lifestyle and sexual practices reported. Compared to HPV− women, HPV+ women were more likely to self-report having had vaginal discharge in the past 24 hours, smoking between 11–20 cigarettes a day, and >7 lifetime sexual partners. HPV− women were primarily classified (77%) into Lactobacillus-spp.-dominated CSTs (CST I and III), with just 23% categorized into the low-Lactobacillus CST IV. By comparison, 50% of lrHPV+ women and 29% of hrHPV+ women were categorized into CST IV.

The vaginal metabolome clusters broadly by CST:

We did not observe clear separation of the vaginal metabolome between HPV+ or HPV− women (ANOSIM R= −0.07, p-value =0.92). Instead, the vaginal metabolomes of women with CST IV microbiota clustered distinctly from those with Lactobacillus-dominated microbiota (CST I and CST III) (ANOSIM R = 0.54, p-value = 0.001; Figure S1A, B). Approximately 31% of the conditional variation and 23% of the marginal variation within the vaginal metabolome was explained by CST (p-value <0.0001; Table S2).

HPV detection is associated with specific metabolites (higher biogenic amines and lower glutathione and lipid concentrations):

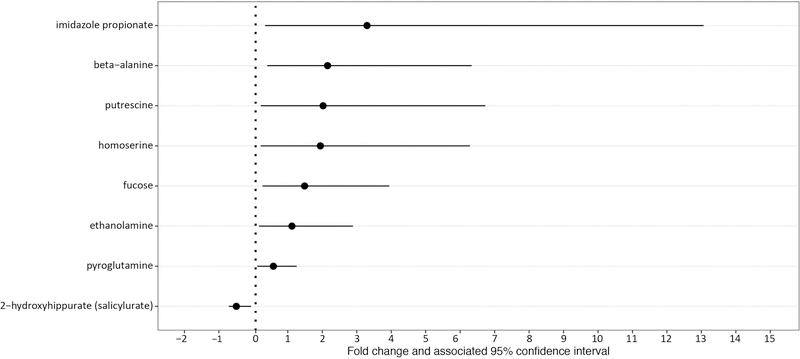

Regression analysis identified eight metabolites that were significantly different between HPV+ and HPV− women (q-value <0.05; Figure 1; Table S3; raw data, Figure S2) after adjustment for CST and smoking status (Model 1). Notably, with the exception of 2-hydroxyhippurate, a xenobiotic, the relative concentration of the remaining metabolites, including putrescine (197%) and ethanolamine (107%) were higher in HPV+ women when compared to HPV− women.

Figure 1|. Fold changes and associated 95% confidence intervals of significantly different metabolites between HPV+ and HPV− women after adjustment for CST and smoking status.

For each metabolite, the dot represents the fold change calculated from exponentiated model coefficients and the line represents the associated 95% confidence interval,

To evaluate whether the relationship between HPV detection status and a given metabolite differed by CSTs, we additionally included an interaction term between CST and HPV detection (Model 2). Within CST I women, no metabolites were significantly associated with HPV detection after adjustment for multiple comparisons. Within CST III women, seven metabolites including n-acetyl-cadaverine (9438%), n-acetyl-putrescine (641%) and putrescine (1210%), all biogenic amines or their derivatives, were found to be significantly higher in HPV+ women than in HPV− women (Table S3). Within CST IV women, HPV+ women had lower concentrations of glutathione, glycogen, and phospholipid-related metabolites than HPV− women (Table S3). The metabolites, reduced-glutathione (GSH) and oxidized-glutathione (GSSG) were 6535% and 2321% lower, respectively, in HPV+ women than in HPV− women. Additionally, the lipids glycerophosphorylcholine (336%), 3-hydroxydecanoate (339%) and choline phosphate (737%) were lower in HPV+ women.

High-risk HPV detection vs Low-risk HPV detection: differences in lyso- and monacylglycero- lipids:

We contrasted the metabolites between lrHPV (n=12) vs. hrHPV (n=14) women (Model 3, Table S3). Thirty-two metabolites, primarily lyso- and monacylglycero- lipids, were significantly different between hrHPV+ vs lrHPV+ women after adjustment for multiple comparisons (q-value < 0.05).

HPV detection is associated with CST-specific metabolite differences in a Partial Least-Squares Discriminant Analysis:

To interrogate potential biomarkers that might discriminate the vaginal metabolomes of HPV+ and HPV− women within each stratum of CST, data were subset into their respective CSTs and the multivariate technique, PLS-DA was applied. While Q2 suggested that the model was overfit, R2 values ranged from 0.6 to 0.98 and PLS-DA appropriately discriminated between HPV+ and HPV− women within each stratum of CST with no overlap at the 95% confidence level (Figure 2). Within CST I, higher concentrations of histamine, 3-n-acetyl-L-cysteine-S-yl acetaminophen, and gamma-aminobutyrate (GABA), a byproduct of bacterial acid stress resistance, were associated with HPV detection. Within CST III, high concentrations of 3-n-acetyl-L-cysteine-S-yl acetaminophen were important in discriminating HPV+ and HPV− women along with higher concentrations of the biogenic amines, n-acetyl-cadaverine, cadaverine, and tyramine. Within CST IV, low concentrations of heme, glycerophosphorylcholine and oxidized-glutathione were indicative of HPV detection (Figure 2).

Figure 2|. Discriminatory metabolites associated with HPV status stratified by CST.

HPV− and HPV+ women within CST-I are compared in the first row (A,B). HPV− and HPV+ women within CST-III are compared in second row (C,D) and HPV− and HPV+ within CST-IV are compared in the third row (E,F). A,C,E show discrimination of groups using partial least squares discriminant analysis. B,D,F show the metabolites most strongly influencing discrimination by the PLS-DA. The variable importance in projection (VIP) score is the weighted sum of squares for the PLS-DA loading with the amount of variation explained by each component taken into account. Asterisks indicate metabolites which are also significant via regression analyses.

HPV detection is associated with over-representation of several non-Lactobacillus spp.:

LEfSe analysis identified differences in the composition of the vaginal microbiota that may relate to HPV detection status even after stratifying participants into CSTs. Notably, in CST IV, HPV+ women significant over-representation of Gardnerella vaginalis, Eggerthella, Atopobium (other than A. vaginae) and Dialister spp., among others, were observed (Figure S3). In contrast, CST IV, HPV− individuals were found to have significant over-representation of Bifidobacteriaceae and Atopobium vaginae Figure S3).

Vaginal microbiota correlate with biogenic amines, lysine, and histidine metabolome differences:

Using Spearman’s correlation analysis, two clusters of metabolites were observed, suggesting similarities in their metabolic capacities and/or requirements with regard to this subset of detectable metabolites (Figure 3). The first cluster consisted of L. crispatus, L. jensenii and L. vaginalis. These species were strongly negatively correlated with biogenic amine-, lysine- and histidine- metabolism and moderately to strongly- positively correlated with lysolipid-, phospholipid-, glutathione-, and glycogen- metabolism. The second cluster consisted of anaerobic species such as Eggerthella, Gardnerella, and Gemella. This cluster was strongly positively correlated with biogenic amine, lysine, and histidine metabolism and moderately to strongly negatively correlated with lipid-, glutathione- and glycogen- metabolism.

Figure 3|.

Correlation analysis of the microbiome and metabolome. Spearman’s correlation analysis was conducted using potential microbiome biomarkers of HPV as identified by linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) and potential metabolite biomarkers identified through multiple linear regression.

Discussion:

Main findings:

Overall, the vaginal metabolome did not cluster by HPV detection status and instead grouped broadly by bacterial composition. Women with CST IV (molecular-BV) microbiota presented a vaginal metabolome that clustered distinctly from those with other CSTs. However, in statistical models that controlled for the driving effects of smoking and CST, higher biogenic amine and phospholipid concentrations were observed in HPV+ women compared with HPV− women, and significant differences in metabolomic profiles of HPV+ and HPV− women were evident within each stratum of CST. Within CST III, HPV+ women had higher concentrations of biogenic amines compared to HPV− women. Within CST IV, HPV+ women had lower concentrations of glutathione, glycogen, and phospholipid-related metabolites than HPV− women. In a secondary analysis, hrHPV women had higher concentrations of multiple lysolipids and monoacylglycerol-lipids compared to lrHPV women. From the microbial perspective, HPV+ women with CST-IV microbiota had an over-representation of Atopobium spp. (other than A. vaginae), Dialister, Eggerthella, Gemella, and Gardnerella spp. These taxa were strongly positively correlated with the biogenic amines putrescine, n-acetyl-cadaverine and n-acetylputrescine.

Strengths and limitations:

We applied an untargeted metabolomics approach to examine HPV+ and HPV− vaginal samples. Furthermore, we were able to assess this association while addressing the vaginal microbiome and smoking behaviors as sources of participant heterogeneity. A previous study has assessed the metabolome of urinary samples based on HPV infection status49. Our study dually applied both GC- and LC-MS metabolomics to characterize the vaginal metabolome, enabling the separation of both soluble, non-volatile and volatile compounds. While the number of participants examined herein is comparable to the Godoy-Vitorino study49, the sample size remains small relative to the number of metabolites measured, and this reduced our ability to identify and adjust for other potentially confounding variables beyond smoking; a variable previously established as being associated with differences in the vaginal metabolome29. It may also have limited our power to detect significant differences in metabolites and microbiota with greater natural variation.

Interpretation:

The association between molecular BV with increased risk for gynecological and reproductive outcomes, including acquisition of HPV and other STIs, is well documented50, 51. Our group and others have previously documented microbial community to be a major driver of the vaginal metabolome34, 35, 38, 52, it is therefore not surprising that in this study, vaginal metabolomes clustered largely according to CST and not by HPV-detection status. However, when controlling for CST and in analyses within each stratum of CST, statistically significant metabolite differences by HPV detection status were observed.

Consistent with the recent study of the urinary metabolome of women varying in HPV status published by Godoy-Vitorino et al. 49, we also observed higher levels of the central nervous system neuromodulator 4-hydoxybutric acid (aka gamma-hydroxybutryic acid or GHB), a precursor to GABA, in HPV+ women. Consistent with the recent study by Ilhan et al.17, we also observed higher levels of several lyso- and monoacylglycerol-lipids in HPV+ women, including choline phosphate, and glycerophosphorylcholine. Within CST IV, HPV+ women had lower levels of glutathione-related metabolites including, oxidized-glutathione and reduced-glutathione. These metabolites may represent oxidative stress and total glutathione depletion. Byproducts of oxidative stress may cause irreversible damage to membrane lipids, proteins and DNA, and have been implicated as potential co-factors in HPV carcinogenesis and persistence53, 54. Future longitudinal studies designed to establish the association of these compounds with disease progression, in combination with specific hrHPV strains, are merited.

Another primary result was that the biogenic amines putrescine and ethanolamine, were significantly higher in HPV+ women after adjustment for CST and smoking status. Cadaverine, tyramine, and two biogenic amine derivatives, n-acetyl-cadaverine and n-acetyl-putrescine, had higher concentrations in HPV+ versus HPV− women in the L. iners-dominated CST. Biogenic amines have been shown to vary by CST, having the greatest relative concentration within the Lactobacillus spp.-depauperate CST IV55 and are elevated among BV-sufferers37, 39, 40, 56–60, with cadaverine, putrescine, and trimethylamine specifically associated with the malodor reported in BV39, 40, 57, 59. Their role in STIs may be multifaceted, with those identified in this study all being formed by the decarboxylation of specific amino acids, a metabolic process utilized by various bacteria to overcome acidic environmental barriers55, such as those documented in the vagina. Biogenic amines have also been reported to alter pathogen virulence, including protecting pathogens such as Neisseria gonorrhea from both the anti-microbial effects of lactic acid and host innate immune defenses61, 62. The relationship between biogenic amines and HPV deserves further exploration.

Additionally, HPV+ L. iners and L. crispatus-dominated women exhibited higher concentrations of the acetaminophen derivative, 3-n-acetyl-L-cysteine-S-yl acetaminophen, suggesting HPV-detection was associated with higher use of the common pain reliever. We also observed over-representation of Gardnerella, Gemella, and Atopobium spp. in HPV+ women with CST IV microbiota which is consistent with a study conducted by Di Paola et al.63. Eggerthella and Gemella possess genes for the production of the biogenic amines agmatine and putrescine, which have been associated with BV39, 40, 55 and, together, should be studied further to evaluate if they reflect a microbial microenvironment with increased risk of HPV acquisition, persistence, or reactivation63. Lastly, our analyses between lrHPV and hrHPV women also pointed to behavioral differences within our population that segregated with detection status. While we observed higher concentrations of the tobacco constituent, cotinine, in hrHPV+ women, this may reflect greater levels of tobacco use among hrHPV+ women or be an artifact of our inability to control for smoking status due to the small sample size.

Conclusion:

Significant differences in the vaginal metabolome were identified by HPV detection status, independent of bacterial community state or smoking status, both known influencers of the vaginal metabolome. This cross-sectional study cannot inform a causal relationship between HPV, the vaginal metabolome, the CST or other host/behavioral characteristics. However, the identified metabolite differences may provide important insights into the biochemical changes in the vaginal microenvironment that increase the risk of HPV infection and how the infection persists. Reduced-glutathione and oxidized-glutathione have known associations with HPV and may represent increased oxidative stress and total glutathione depletion. Chronic oxidative stress environments may compromise normal host responses to infection or increase risk of disease progression. The increased levels of reduced-glutathione and oxidized-glutathione observed in women with HPV detection supports further investigation. These data provide information on possible physiological pathways that may either induce HPV reactivation or clearance that could be targets for therapeutic non-surgical interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was funded by two University of Maryland pilot study grants ((1) a University of Maryland Cancer Epidemiology Alliance Joint Research Pilot Grant sponsored by the University of Maryland Greenebaum Cancer Center (Brotman), and (2) a University of Maryland College Park/ University of Maryland Baltimore Seed Grant (Brotman and Glover)). The analyses were also funded in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants R01-AI116799 (Brotman). This manuscript is a secondary analysis of archived data and was not assessed by an external peer review for scientific quality. The Parent study was funded by two separate University of Maryland internal seed grant funds and both grants were reviewed by University of Maryland reviewers. To our knowledge, external reviewers did not sit on either of the University of Maryland seed grant committees and there was not a patient or public involvement panel that participated in grant review. The funder did not play a role in the conduct of the study or in manuscript preparation. NIAID funding supported personnel efforts in the development of statistical methods.

Funding: University of Maryland, NIH

Footnotes

Disclosures of interest:

JR is the co-founder of LUCA Biologics, a biotechnology company focusing on translating microbiome research into live biotherapeutics drugs for women health. All remaining authors have no disclosures to declare. Completed disclosure of interest forms are available to view online as supporting information.

Details of ethics approval:

All participants provided written informed consent, and ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Maryland Baltimore (UMB) [HP-00045732; 09/12/2011], Montana State University [CY010818-EX; 1/8/18], and the University of Maryland School of Public Health [10–0301; 07/28/2010]. This secondary analysis was not assessed by an external peer review for scientific quality, and there was not a patient or public panel that participated in review. A core outcome set for reporting data was not available on the topic of sexually transmitted infection research, however we did follow STROBE guidelines in the report of this case control study64–66. All samples were collected and analyzed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data Availability:

The questionnaire and metabolome data are available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) under Accession number phs001386.v1.p1. Metagenomic sequence data were submitted to the public NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the accession number PRJNA391039.

Code Availability:

The code used to analyze these data has been provided as supplemental material (see Appendix S1).

REFERENCES:

- 1.Schoell WM, Janicek MF, Mirhashemi R. Epidemiology and biology of cervical cancer. SeminSurgOncol. 1999;16(3):203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfister H. Human papillomaviruses and genital cancer. AdvCancer Res. 1987;48:113–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salzman NP, Howley PM. The Papovaviridae. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plummer M, Herrero R, Franceschi S, Meijer CJ, Snijders P, Bosch FX, et al. Smoking and cervical cancer: pooled analysis of the IARC multi-centric case--control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14(9):805–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical C, Appleby P, Beral V, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Colin D, Franceschi S, et al. Carcinoma of the cervix and tobacco smoking: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 13,541 women with carcinoma of the cervix and 23,017 women without carcinoma of the cervix from 23 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(6):1481–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlecht NF, Kulaga S, Robitaille J, Ferreira S, Santos M, Miyamura RA, et al. Persistent human papillomavirus infection as a predictor of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286(24):3106–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Cerdeira C, Sanchez-Blanco E, Alba A. Evaluation of Association between Vaginal Infections and High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Types in Female Sex Workers in Spain. ISRN obstetrics and gynecology. 2012;2012:240190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNicol P, Paraskevas M, Guijon F. Variability of polymerase chain reaction-based detection of human papillomavirus DNA is associated with the composition of vaginal microbial flora. Journal of medical virology. 1994;43(2):194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mao C, Hughes JP, Kiviat N, Kuypers J, Lee SK, Adam DE, et al. Clinical findings among young women with genital human papillomavirus infection. Am J Obs Gyn. 2003;188(3):677–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klomp JM, Boon ME, Van Haaften M, Heintz APM. Cytologically diagnosed Gardnerella vaginalis infection and cervical (pre)neoplasia as established in population-based cervical screening. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;199(5):480.e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dols JA, Reid G, Kort R, Schuren FH, Tempelman H, Bontekoe TR, et al. PCR-based identification of eight Lactobacillus species and 18 hr-HPV genotypes in fixed cervical samples of South African women at risk of HIV and BV. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2012;40(6):472–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiley DJ, Masongsong EV, Lu S, Heather LS, Salem B, Giuliano AR, et al. Behavioral and sociodemographic risk factors for serological and DNA evidence of HPV6, 11, 16, 18 infections. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(3):e183–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nam KH, Kim YT, Kim SR, Kim SW, Kim JW, Lee MK, et al. Association between bacterial vaginosis and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Journal of gynecologic oncology. 2009;20(1):39–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JE, Lee S, Lee H, Song Y-M, Lee K, Han MJ, et al. Association of the Vaginal Microbiota with Human Papillomavirus Infection in a Korean Twin Cohort. PloS one. 2013;8(5):e63514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillet E, Meys JF, Verstraelen H, Bosire C, De Sutter P, Temmerman M, et al. Bacterial vaginosis is associated with uterine cervical human papillomavirus infection: a meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitra A, MacIntyre DA, Marchesi JR, Lee YS, Bennett PR, Kyrgiou M. The vaginal microbiota, human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: what do we know and where are we going next? Microbiome. 2016;4(1):58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilhan ZE, Laniewski P, Thomas N, Roe DJ, Chase DM, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Deciphering the complex interplay between microbiota, HPV, inflammation and cancer through cervicovaginal metabolic profiling. EBioMedicine. 2019. June;44:675–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dareng EO, Ma B, Famooto AO, Adebamowo SN, Offiong RA, Olaniyan O, et al. Prevalent high-risk HPV infection and vaginal microbiota in Nigerian women. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(1):123–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shannon B, Yi TJ, Perusini S, Gajer P, Ma B, Humphrys MS, et al. Association of HPV infection and clearance with cervicovaginal immunology and the vaginal microbiota. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10(5):1310–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SS, McCulle SL, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108 Suppl 1:4680–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boskey ER, Cone RA, Whaley KJ, Moench TR. Origins of vaginal acidity: high D/L lactate ratio is consistent with bacteria being the primary source. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2001;16(9):1809–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aroutcheva A, Gariti D, Simon M, Shott S, Faro J, Simoes JA, et al. Defense factors of vaginal lactobacilli. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2001;185(2):375–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ocana VS, Pesce De Ruiz Holgado AA, Nader-Macias ME. Characterization of a bacteriocin-like substance produced by a vaginal Lactobacillus salivarius strain. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1999;65(12):5631–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reid G, Heinemann C, Velraeds M, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Biosurfactants produced by Lactobacillus. Methods in enzymology. 1999;310:426–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaewsrichan J, Peeyananjarassri K, Kongprasertkit J. Selection and identification of anaerobic lactobacilli producing inhibitory compounds against vaginal pathogens. FEMS ImmunolMedMicrobiol. 2006;48(1):75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boris S, Barbés C. Role played by lactobacilli in controlling the population of vaginal pathogens. Microbes Infect. 2000;2(5):543–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borgogna J-LC, Yeoman CJ. The Application of Molecular Methods Towards an Understanding of the Role of the Vaginal Microbiome in Health and Disease. The Human Microbiome. Methods in Microbiology 2017. p. 37–91.

- 28.McKinnon LR, Achilles SL, Bradshaw CS, Burgener A, Crucitti T, Fredricks DN, et al. The Evolving Facets of Bacterial Vaginosis: Implications for HIV Transmission. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2019;35(3):219–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brotman RM, He X, Gajer P, Fadrosh D, Sharma E, Mongodin EF, et al. Association between cigarette smoking and the vaginal microbiota: a pilot study. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brotman RM, Shardell MD, Gajer P, Tracy JK, Zenilman JM, Ravel J, et al. Interplay between the temporal dynamics of the vaginal microbiota and human papillomavirus detection. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(11):1723–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onywera H, Williamson AL, Mbulawa ZZA, Coetzee D, Meiring TL. The cervical microbiota in reproductive-age South African women with and without human papillomavirus infection. Papillomavirus Res. 2019;7:154–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laniewski P, Cui H, Roe DJ, Barnes D, Goulder A, Monk BJ, et al. Features of the cervicovaginal microenvironment drive cancer biomarker signatures in patients across cervical carcinogenesis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koumans EH, Sternberg M, Bruce C, McQuillan G, Kendrick J, Sutton M, et al. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in the United States, 2001–2004; associations with symptoms, sexual behaviors, and reproductive health. Sex TransmDis. 2007;34(11):864–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson TM, Borgogna JC, Michalek RD, Roberts DW, Rath JM, Glover ED, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with an altered vaginal tract metabolomic profile. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hillier SL. Diagnostic microbiology of bacterial vaginosis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1993;169(2 Pt 2):455–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Koppolu S, Chappell C, Moncla BJ, Hillier SL, Mahal LK. Studying the effects of reproductive hormones and bacterial vaginosis on the glycome of lavage samples from the cervicovaginal cavity. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0127021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sobel JD, Karpas Z, Lorber A. Diagnosing vaginal infections through measurement of biogenic amines by ion mobility spectrometry. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2012. July;163(1):81–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Witkin SS, Ledger WJ. Complexities of the uniquely human vagina. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(132):132fs11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeoman CJ, Thomas SM, Miller ME, Ulanov AV, Torralba M, Lucas S, et al. A multi-omic systems-based approach reveals metabolic markers of bacterial vaginosis and insight into the disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Srinivasan S, Morgan MT, Fiedler TL, Djukovic D, Hoffman NG, Raftery D, et al. Metabolic signatures of bacterial vaginosis. mBio. 2015;6(2): 10.1128/mBio.00204-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dobierzewska A, Soman S, Illanes SE, Morris AJ. Plasma cross-gestational sphingolipidomic analyses reveal potential first trimester biomarkers of preeclampsia. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romero R, Mazaki-Tovi S, Vaisbuch E, Kusanovic JP, Chaiworapongsa T, Gomez R, et al. Metabolomics in premature labor: a novel approach to identify patients at risk for preterm delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23(12):1344–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang J, Zhao X, Lu X, Lin X, Xu G. A data preprocessing strategy for metabolomics to reduce the mask effect in data analysis. Front Mol Biosci. 2015;2:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smilde AK, van der Werf MJ, Bijlsma S, van der Werff-van der Vat BJ, Jellema RH. Fusion of mass spectrometry-based metabolomics data. Anal Chem. 2005;77(20):6729–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei R, Wang J, Su M, Jia E, Chen S, Chen T, et al. Missing Value Imputation Approach for Mass Spectrometry-based Metabolomics Data. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia J, Wishart DS. Web-based inference of biological patterns, functions and pathways from metabolomic data using MetaboAnalyst. Nat Protoc. 2011;6(6):743–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Storey JD. A Direct Approach to False Discovery Rates. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Statistical Methodology). 2002;64(3):479–98. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12(6):R60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Godoy-Vitorino F, Ortiz-Morales G, Romaguera J, Sanchez MM, Martinez-Ferrer M, Chorna N. Discriminating high-risk cervical Human Papilloma Virus infections with urinary biomarkers via non-targeted GC-MS-based metabolomics. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0209936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martin DH. The microbiota of the vagina and its influence on women’s health and disease. Am J Med Sci. 2012;343:2–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nardis C, Mosca L, Mastromarino P. Vaginal microbiota and viral sexually transmitted diseases. Ann Ig. 2013;25(5):443–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sobel JD. Bacterial vaginosis. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:349–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Marco F. Oxidative stress and HPV carcinogenesis. Viruses. 2013;5(2):708–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borges BES, Brito EB, Fuzii HT, Baltazar CS, Sa AB, Silva C, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer precursor lesions in women living by Amazon rivers: investigation of relations with markers of oxidative stress. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2018;16(3):eAO4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nelson TM, Borgogna JL, Brotman RM, Ravel J, Walk ST, Yeoman CJ. Vaginal biogenic amines: biomarkers of bacterial vaginosis or precursors to vaginal dysbiosis? Frontiers in physiology. 2015;6:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vitali B, Cruciani F, Picone G, Parolin C, Donders G, Laghi L. Vaginal microbiome and metabolome highlight specific signatures of bacterial vaginosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34(12):2367–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolrath H, Boren H, Hallen A, Forsum U. Trimethylamine content in vaginal secretion and its relation to bacterial vaginosis. APMIS. 2002;110(11):819–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Rabe LK, Klebanoff SJ, Eschenbach DA. The normal vaginal flora, H2O2-producing lactobacilli, and bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1993;16 Suppl 4:S273–S81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen KC, Forsyth PS, Buchanan TM, Holmes KK. Amine content of vaginal fluid from untreated and treated patients with nonspecific vaginitis. J Clin Invest. 1979;63(5):828–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen KC, Amsel R, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK. Biochemical diagnosis of vaginitis: determination of diamines in vaginal fluid. J Infect Dis. 1982;145(3):337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goytia M, Shafer WM. Polyamines can increase resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to mediators of the innate human host defense. Infect Immun. 2010;78(7):3187–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gong Z, Tang MM, Wu X, Phillips N, Galkowski D, Jarvis GA, et al. Arginine- and Polyamine-Induced Lactic Acid Resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Di Paola M, Sani C, Clemente AM, Iossa A, Perissi E, Castronovo G, et al. Characterization of cervico-vaginal microbiota in women developing persistent high-risk Human Papillomavirus infection. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1500–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Field N, Cohen T, Struelens MJ, Palm D, Cookson B, Glynn JR, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Molecular Epidemiology for Infectious Diseases (STROME-ID): an extension of the STROBE statement. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(4):341–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gallo V, Egger M, McCormack V, Farmer PB, Ioannidis JP, Kirsch-Volders M, et al. STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology - Molecular Epidemiology (STROBE-ME): an extension of the STROBE statement. Eur J Clin Invest. 2012;42(1):1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.