Abstract

Air pollution exposure is known to contribute to the progression of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and there is increasing evidence that dysbiosis of the gut microbiome may also play a role in the pathogenesis of CVD, including atherosclerosis. To date, the effects of inhaled air pollution mixtures on the intestinal epithelial barrier (IEB), and microbiota profiles are not well characterized, especially in susceptible individuals with comorbidity. Thus, we investigated the effects of inhaled ubiquitous air-pollutants, wood-smoke (WS) and mixed diesel and gasoline vehicle exhaust (MVE) on alterations in the expression of markers of integrity, inflammation, and microbiota profiles in the intestine of atherosclerotic Apolipoprotein E knockout (ApoE−/−) mice. To do this, male 8 wk-old ApoE−/− mice, on a high-fat diet, were exposed to either MVE (300 μg/m3 PM), WS; (~450 μg/m3 PM), or filtered air (FA) for 6 hr/d, 7d/wk, for 50 d. Immunofluorescence and RT-PCR were used to quantify the expression of IEB components and inflammatory factors, including mucin (Muc)-2, tight junction (TJ) proteins, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interleukin (IL)-1β, as well as Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4. Microbial profiling of the intestine was done using Illumina 16S sequencing of V4 16S rRNA PCR amplicons. We observed a decrease in intestinal Muc2 and TJ proteins in both MVE and WS exposures, compared to FA controls, associated with a significant increase in MMP-9, TLR-4, and inflammatory marker expression. Both WS and MVE-exposure resulted in decreased intestinal bacterial diversity, as well as alterations in microbiota profiles, including the Firmicutes: Bacteroidetes ratio at the phylum level. Our findings suggest inhalation exposure to either MVE or WS result in alterations in components involved in mucosal integrity, and also microbiota profiles and diversity, which are associated with increased markers of an inflammatory response.

Keywords: Air Pollution, Microbiome, Intestine Epithelial Barrier, Inflammation Funding

1. Introduction.

The human microbiome is a dynamic system of microbial species that are involved in a vast array of homeostatic functions in the human body. Several recent studies have linked altered gut microbiota and/or translocation to the local and systemic inflammation, which is known to contribute the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) such as atherosclerosis (Ahmad et al., 2019; Ojeda et al., 2016; Turnbaugh et al., 2006). As cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death, and the prevalence of gastrointestinal autoimmune diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), are increasing worldwide, it is important to characterize the role of environmental xenobiotics in contributing to these disease states (Benjamin et al., 2018; Lerner et al., 2015). Furthermore, it is important to understand how environmental exposure may contribute to comorbidity in susceptible individuals. While the etiology of these diseases is complicated, involving a combination of genetics, diet, and socioeconomic factors, few studies have researched the role of environmental air pollutants in digestive health in populations with underlying CVD.

The human microbiome consists of more than 1014 bacterial organisms belonging to an estimated 2000 species, with the majority of these being present in the gut (Neish, 2009). These commensal bacteria that colonize the gut are involved in homeostatic functions including digestion, nutrient absorption, immune system activation, and development (Backhed et al., 2005; Li et al., 2008; Palm et al., 2015). Importantly, an individual’s microbiome is influenced by both diet and environmental exposures early in life (Palmer et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2011). The epithelium of the intestines serves as a barrier between the gut microbiota and the systemic environment, which consists of an apical barrier of epithelial cells and an apical junction complex forming a connection between epithelial cells. This complex consists of tight junction (TJ) proteins, which include occludin, claudins, zona-occludin, and junction adhesion molecules (JAMs), as well as others, which contribute to the bond between neighboring epithelial cells (Nursat et al. 2000). Secreted mucins (e.g. Muc2), produce a protective mucous barrier that limits gut epithelial cells interface with the environment, thereby reducing the likelihood of an inflammatory response. Degradation of mucin by microbiota promotes inflammation and disruption of the intestinal epithelial barrier (IEB) (Darrien et al. 2010). Alteration in the integrity of the IEB can lead to induction of local and systemic inflammatory signaling pathways, such as interleukin (IL)-1β and/or tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, induction of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity, each of which are associated with increased intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation due to altered expression of TJ proteins (Festi et al., 2014; Nighot et al., 2015). The toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 is a receptor of the innate immune system that is activated by lipopolysaccharides (LPS) derived from Gram-negative bacteria (Takeuchi et al., 1999). Increased bacterial translocation can lead to activation of the TLR4 systemically, which has been reported to mediate inflammatory and metabolic disease states, including CVD (Carnevale et al., 2018; Velloso et al., 2015). Importantly, disruption of the structural components of the IEB can also lead to alterations in microbiota profiles that inhabit that region. Specifically, alterations in the ratio of the two primary phyla of bacteria, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, has been associated with gut inflammation and systemic inflammatory disease states such as obesity, insulin resistance, and atherosclerosis (Alderete et al., 2018; Caesare et al., 2010; Dumas et al., 2006; Million et al., 2013).

We have previously reported that inhalation exposure to traffic-generated air pollutants or wood smoke mediates plaque growth and signaling in the vasculature that is associated with progression of atherosclerosis, including inflammation and MMP activity in Apolipoprotein E-knockout (Apo E)−/− mice (Campen et al., 2010; Campen, 2012; Lund et al., 2009; Lund et al., 2011; Mauderly et al., 2014; Sielkop et al., 2012). We have also reported that inhalation exposure to mixed vehicle emissions (MVE) promotes expression of inflammatory markers and alters TJ protein expression in the cerebral microvasculature of Apo E−/− and C57Bl/6 wild-type mice (Lucero et al., 2017; Suwannasual et al., 2018; Oppenheim et al., 2013). More recently, studies have revealed a role for environmental air pollution exposure on dysbiosis and inflammatory disorders of the intestines (Kish et al., 2013; Mutlu et al., 2011; Mutlu et al., 2018). While little research has been done on the effects of air pollution on the gut, findings from a few recent studies suggest that inhaled or ingested particulate matter (PM) is associated with increased intestinal permeability, due to rearrangement of TJ proteins, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS), and inflammation (Li et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019a; Li et al., 2019b; Vignal et al., 2017). Furthermore, inhalation exposure to ambient PM (~135 μg/m3, 8 h/d, 5 d/wk, for 3 wks) has been reported to alter gut microbiota composition and diversity along the GI tract (Mutlu et al., 2018). However, to date, the effects of inhaled mixtures of environmental pollutants (e.g. gaseous and PM) on gut integrity, inflammation, and resulting microbiota dysbiosis are not yet fully characterized. Considering this current gap in knowledge, we investigated the hypothesis that inhaled air pollutants, from both anthropogenic (vehicle exhaust) and natural (wood-burning) sources, result in gut inflammation, associated with decreased expression of factors that contribute to intestinal barrier integrity, and alterations in microbial communities within the intestine in the Apo E−/− mouse model. The Apo E−/− mouse develops atherosclerosis similar in etiology to humans when fed a high fat “Western” diet. The rationale for using this model was to correlate findings from the current study with those previously observed in our laboratory related to inhaled pollutant-exposure mediating exacerbation of CVD (Lund et al., 2009; Lund et al., 2011; Mauderly et al., 2014).

2. Methods.

2.1. Animals and Inhalational Exposure.

Eight-week-old male ApoE−/− mice (Taconic, Hudson, NY) were placed on a high-fat diet (21.2% fat, 1.5 g/kg cholesterol; Research Diets #D1001) for 2 weeks prior to the onset of exposure. ApoE−/− mice were exposed by whole-body inhalation to either: 300μg/m3 PM mixed diesel and gasoline engine emissions (MVE was composed of 50μg/m3 PM gasoline engine emissions + 250 PM μg/m3 diesel engine emissions), wood smoke (WS: ~440μg/m3 PM), or filtered air (FA, controls) for 6 hr/day, 7 days/week, for 50 days (n=20 per group); pollutant mixtures were generated as previously described (Reed et al., 2006; Lund et al., 2011; Oppenheim et al., 2013). Briefly, MVE was created by combining exhaust from a 1996 GM gasoline engine and a Yanmar diesel generator system, which operated on repeating California Unified Driving Cycles, in a pre-exposure chamber upstream of the animal exposure chambers. The exhaust then passed through original engine mufflers and catalytic converters into a constant-flow dilution tunnel and was then diluted further in parallel to the final concentrations, as previously described (Mauderly et al., 2014, Lund et al, 2011; Oppenheim et al., 2013). Wood smoke was generated from split oak burned on a single daily 3-phase cycle (kindling, high burn, low burn) in a heating stove, as previously described (Mauderly et al., 2014; McDonald et al., 2006). A portion of the effluent was drawn from near the top of the 6 m tall flue into the dilution system to generate the targeted concentration to the animal exposure chambers. Samples average nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon monoxide (CO), and PM levels delivered to the chambers, for the duration of the exposure, are provided in Table S1. Mice were housed in standard shoebox cages within an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International-approved rodent housing facility (2m3 exposure chambers) for the entirety of the study, which maintained temperature (20–24°C) and humidity (30–60% relative humidity). Mice had access to chow and water ad libitum throughout the study period, except during daily exposures when chow was removed. All animal protocols were approved by the Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute’s Animal Care and Use Committee and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996).

Within 24 hours after the final exposure, animals were anesthetized with Euthasol (390 mg pentobarbital sodium, 50 mg phenytoin sodium/ml; diluted 1:10 and administered at a dose 0.1 ml per 30 g mouse) and euthanized by exsanguination. The animals were weighed at necropsy (Fig. S1) and the GI tract from the stomach to the rectum was removed, dissected into regions, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80° C for future histological, molecular, and microbiota analysis.

2.2. Immunofluorescence Analysis of the Intestines.

A portion of the duodenum was dissected and fixed in Zinc Formalin fixative (Sigma Aldrich, catalog #Z2902) for 2 hrs at 4°C on a rocker, dehydrated, cleared 3 times in HistoChoice Clearing Agent (VWR, 97060–932) 40 min each at RT, embedded in paraffin, cut on a microtome (8μm thickness), and floated on slides in a 37°C water bath. Immunofluorescent staining was used to quantify MMP-9, and TJ proteins occludin and claudin-3, using techniques previously described by our laboratory (Lund et al., 2011), with the following modifications. Briefly, tissues were cleared with HistoChoice Clearing Agent for 20 min at RT, rehydrated, and stained using the following primary antibodies: MMP-9 (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA; Cat. #38898), occludin (1:500; Abcam #168986), claudin-3 (1:1000; Abcam #15102), TNF-α (1:1000, Abcam #6671), and anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 (1:500) secondary antibody. Slides were imaged under fluorescent microscopy at 20× and 40× with the appropriate excitation/emission filter, digitally recorded, RGB overlay signals were split and analyzed for specific fluorescence using image densitometry with Image J software (NIH). Slides with no primary antibody were used as negative controls (data not shown). A minimum of 2–3 locations on each section (5 sections per slide), 2 slides and n=4–5 per group were used for analysis; 40× images were used for quantification of TJ proteins occludin and claudin-3 and TNF-α; 20× images were used for quantification of MMP-9.

2.3. Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the duodenum and ileum (n=8 per group) using an RNAEasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) per kit instructions, and cDNA was synthesized using an iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Biorad, Hercules, CA; Cat. #170–8891). Real time PCR analysis of barrier integrity proteins MMP-9, Muc2, claudin-2, and claudin-3, as well as markers of inflammation (IL1-β, TNF-α, TLR-4), was conducted using specific primers (Table S2) and SYBR green detection (SSo Advanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix, Biorad; Cat #172–5271), following manufacturer’s protocol, on a Biorad CFX96, and ΔΔCT values calculated and normalized (to GAPDH), as previously described by our laboratory (Lund et al., 2009; Lund et al., 2011).

2.4. Illumina MiSeq Sequencing.

Genomic DNA was extracted from ileal tissue via homogenization (Beadbeater) and purified using the QIAGEN AllPrep mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), samples were then measured for purity using a NanoSpec. The V4 variable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified from ileal tissue DNA (n=10 MVE and FA, n=9 WS) using the 16S metagenomic sequencing library protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA). The primer pairs which also incorporates the Illumina overhang adaptor used in this study were Illumina 4 forward primer (FP): TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA, and Illumina 4 reverse primer (RP): GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT. Duplicate PCR reactions were completed on the template DNA for each sample. The PCR reaction contained: DNA template (1 μl), 0.5 μl FP (10 μM), 0.5 μl RP (10 μM), 2.5 μl 10× AccuPrime PCR Buffer II, 1.5 μl Mg (50mM), 0.1 μl AccuPrime Taq High Fidelity (5U/μl), and PCR grade water to a final volume of 25 μl. PCR amplification was carried out as follows: heated lid 94°C × 2mins, 30 cycles of 94°C × 15s, 52°C × 15s, 68°C × 40s, 68°C × 5mins and held at 4°C. PCR products were viewed using gel electrophoresis (1× TAE buffer, 1.5% agarose, Phenix GelRed). Successful PCR products were cleaned using AMPure XP magnetic bead-based purification (Illumina protocol).

An index PCR reaction was then completed to add an index to each sample, allowing all samples to be pooled for sequencing on the one flow cell and subsequently demultiplexed for analysis. Each 50 μl PCR reaction contained: 5 μl 10× AccuPrime PCR Buffer II, 5 μl Nextera XT indexing primers 1 (N7xx), 5 μl Nextera XT indexing primers 2 (S5xx), 0.2 μl AccuPrime Taq High Fidelity (5U/μl), 5 μl purified DNA, and PCR grade water. The PCR recipe was as follows: heated lid 94°C × 3mins, 8 cycles of 94°C × 30s, 55°C × 30s, 68°C × 30s, 68°C × 5 mins and held at 4°C. PCR products were cleaned (as described above), quantified using a Qubit, and then pooled with an equal amount. The pooled sample was then denatured, diluted, loaded, and sequenced following the Illumina protocol (Illumina Part #15044223, Rev B.).

2.5. Statistical Analysis.

Intestinal immunofluorescence and RT-qPCR data are be expressed as mean ± SEM. A student’s t-test was use to analyze differences between an exposure group compared to the FA control group, whereas a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post hoc Tukey’s test was used for analysis of significance between multiple groups using Sigma Plot 12.0 (Systat, San Jose, CA). A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.6. Bioinformatics Microbiota 16S and Statistical Analysis.

Sequences generated from the MiSeq were processed through the Mothur v.1.36.1 pipeline following the MiSeq SOP (Schloss et al., 2009). Briefly, pair-end sequences were assembled, primers were trimmed, short (< 100bp) and low-quality (homopolymers > 8) sequences were excluded from the dataset. Multiple sequence alignments were built using the SILVA reference database. The sequences that could not be aligned were removed and gaps were further removed from the aligned sequences. Redundant sequences were reduced through the unique.seqs and precluster (diffs=2) command. Chimeras were identified using UCHIME and removed from the datasets (Edgar et al., 2011). Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were assigned with the average neighbor clustering algorithm based on 97% sequence similarity. Taxonomic classification was conducted using the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) classifier with a minimum of 80% confidence (Wang et al., 2007). The mitochondria, chloroplast, archaea, and eukaryote, as well as unknown sequences, were removed from the dataset. Diversity indices [Shannon diversity, Chao1, abundance coverage-based estimator (ACE) richness, and evenness] estimators were generated based on operational taxonomic units (OTUs) grouped at 97% sequences similarity for species-level classification (Chao, 1984; Chazdon et al., 1998; Shannon and Weaver, 1949). UniFrac and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was also performed to compare the microbial communities among different samples (Lozupone and Knight, 2005). One sample (FA6) was excluded from the dataset due to low number of reads (1460 vs. >11109 in all other samples). Both alpha and beta diversity were calculated after rarefying to the sequencing depth to 11109 reads per sample. Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA) and Analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) was performed to assess the variations and similarities among different groups as described previously. To further investigate the microbial community differences among different exposures, the Kruskal-Wallis test and post hoc Dunn’s test were performed at phylum and genus levels. P values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method to control the false positive discovery rate (FDR). Diversity estimators, UniFrac, PCoA, AMOVA, and ANOSIM analyses were performed using Mothur. Kruskal-Wallis test and post hoc Dunn’s test were conducted using the FSA package in R.

3. Results:

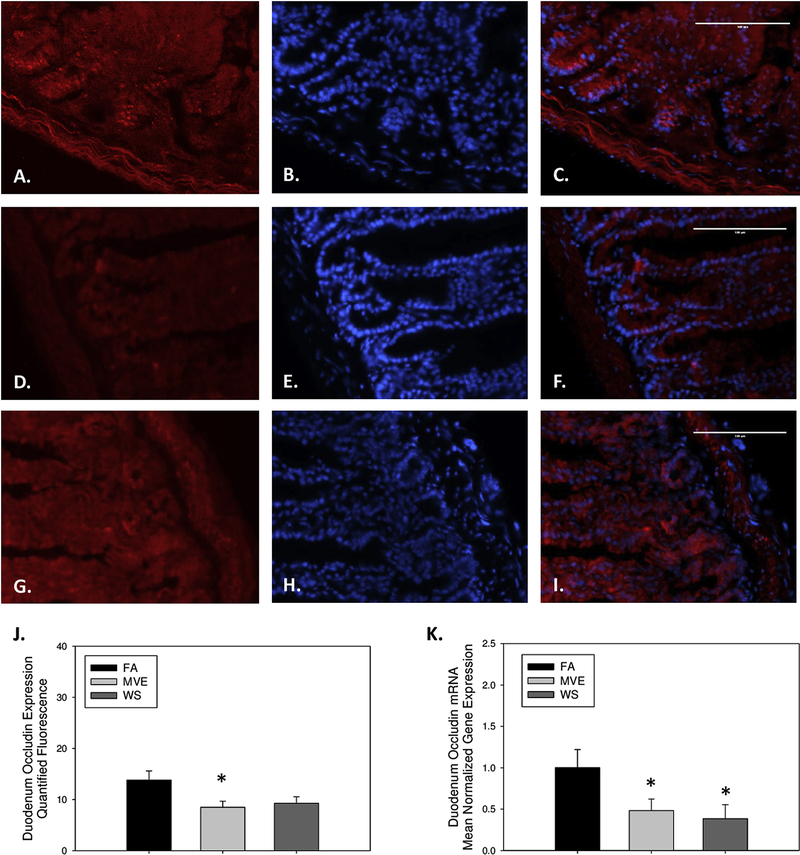

3.1. Exposure to inhaled air pollutants MVE and WS result in alterations of tight junction protein expression in the duodenum of ApoE−/− mice.

To investigate whether exposure to inhaled ubiquitous-source environmental air pollutant exposures resulted in alteration of the IEB integrity in ApoE−/− mice, we analyzed the duodenum expression of common components of IEB integrity, TJ proteins: occludin, claudin-2, and claudin-3 at the protein and mRNA transcript level. Compared to our FA controls (Figs. 1A–C), we observed decreased expression of occludin in the duodenum of our MVE (Figs. 1D–F) and WS-exposed animals (Figs. 1G–I), as quantified in Fig. 1J. Although levels were only significantly decreased in the MVE-exposed animals (Fig. 1J; p=0.034). Interestingly, we observed a statistical decrease in duodenal occludin expression in both WS and MVE-exposed animals at the mRNA transcript level, compared to FA controls (Fig. 1K; p<0.050).

Figure 1.

Representative images of occludin expression in the duodenum of Apo E−/− mice, on a Western diet, exposed to either (A-C) filtered air, (D-F) PM mixed vehicle exhaust (MVE; 300μg/m3 PM), or (G-I) wood smoke (WS: ~440μg/m3 PM). Red fluorescence indicates occludin expression, blue fluorescence is nuclear staining (Hoescht). (J) Graph of histology analysis of duodenal occludin fluorescence. (K) RT-qPCR analysis of occludin mRNA transcript expression in the duodenum. *p<0.050 compared to FA using a one way ANOVA. Scale bar = 100 μm.

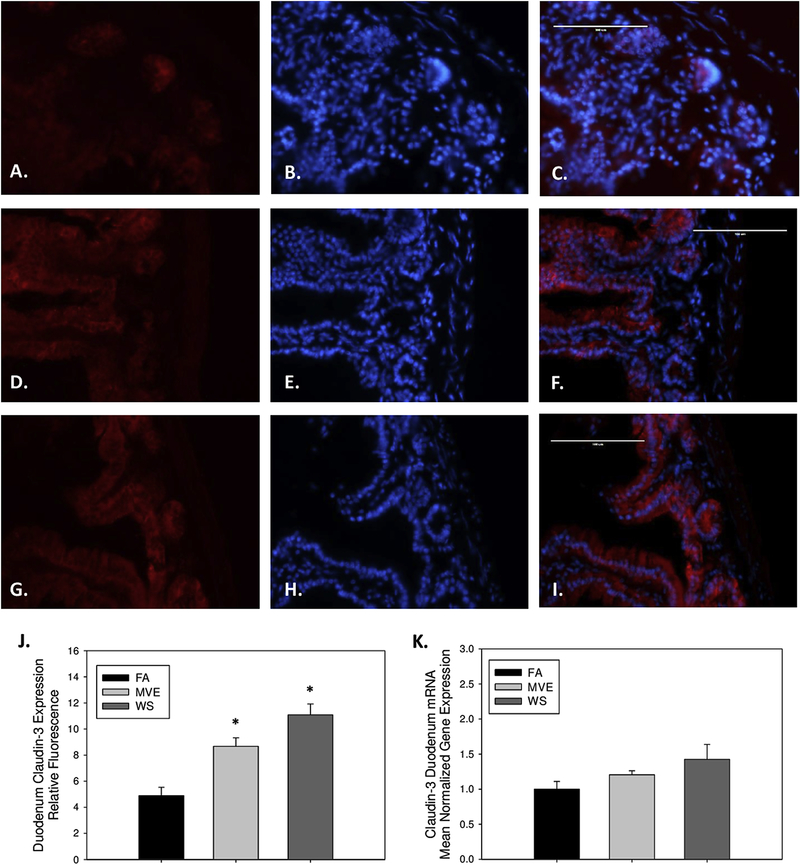

Contrary to the results observed with occludin, compared to our FA controls (Figs. 2A–C), we found claudin-3 to be increased in the duodenum of the MVE (Figs. 2D–F, p=0.003) and WS-exposure groups (Figs. 2G–I, p<0.001), as quantified by total fluorescence (Fig. 2J). And while we also observed increases in expression of claudin-3 at the mRNA level (Fig. 2K), they were not statistically significant. We saw a similar trend in the expression of duodenal claudin-2 mRNA transcript with MVE and WS-exposure (1.2-fold and 1.4-fold induction, respectively; data not shown) compared to FA controls; however, based on the lack of response at the transcript level we did not analyze the expression of claudin-2 at the protein level.

Figure 2.

Representative images of claudin-3 expression in the duodenum of Apo E−/− mice, on a Western diet exposed to either (A-C) filtered air, (D-F) mixed exhaust (MVE; 300μg/m3 PM), or (G-I) 440 μg/m3 PM wood smoke (WS: ~440μg/m3 PM). Red fluorescence indicates claudin-3 expression, blue fluorescence is nuclear staining (Hoescht). (J) Graph of histology analysis of duodenal claudin-3 fluorescence. (K) RT-qPCR analysis of claudin-3 mRNA transcript expression in the duodenum. *p<0.050 compared to FA using a one way ANOVA. Scale bar = 100 μm.

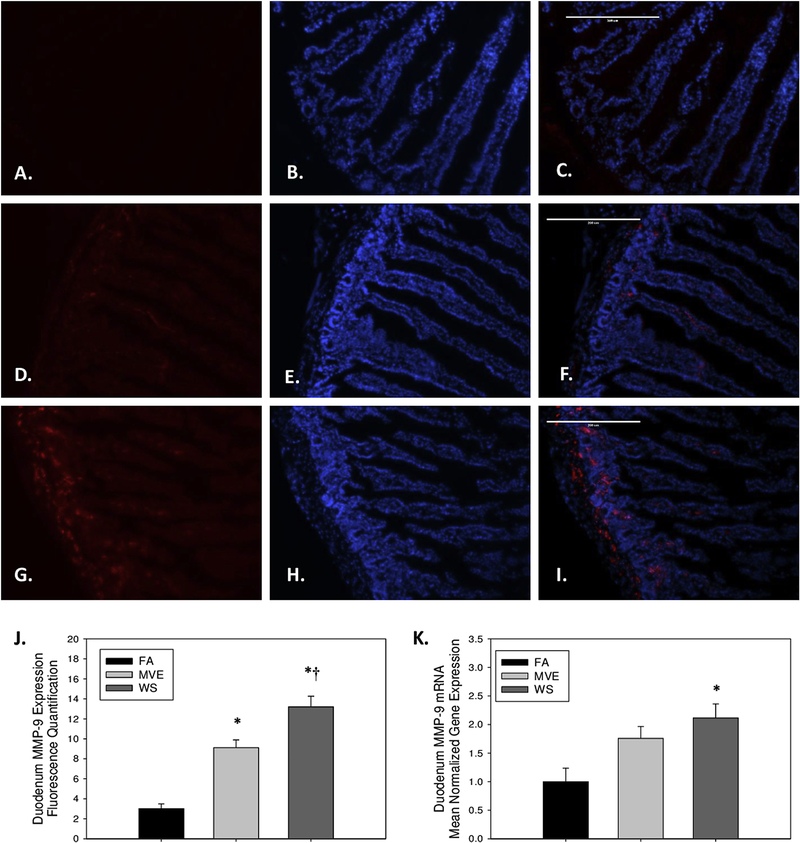

3.2. Exposure to inhaled MVE and WS increase MMP-9 expression in the duodenum of ApoE−/− mice.

As increased MMP-9 expression and activity are associated with increased degradation of TJ proteins and resulting alterations in IEB integrity, we analyzed the expression of MMP-9 in the duodenum of our study animals. We observed duodenal MMP-9 levels to be significantly elevated, compared to FA control animals (Figs. 3A–C), in both our MVE- (Figs. 3D–F, p<0.001), and WS-exposed (Figs. 3G–I, p<0.001) groups, as quantified in Fig. 3J. Additionally, there was a statistical increase in duodenum MMP-9 expression in the WS-exposed, compared to MVE-exposed (p=0.005). We saw similar trends in the induction of MMP-9 mRNA expression; however, only the WS-exposed groups showed a statistical increase when compared to FA controls (Fig. 3K, p=0.012).

Figure 3.

Representative images of MMP-9 expression in the duodenum of Apo E−/− mice, on a Western diet exposed to either (A-C) filtered air, (D-F) mixed exhaust (MVE; 300μg/m3 PM), or (G-I) wood smoke (WS: ~440μg/m3 PM). Red fluorescence indicates MMP-9 expression, blue fluorescence is nuclear staining (Hoescht). (J) Graph of histology analysis of duodenal MMP-9 fluorescence. (K) RT-qPCR analysis of MMP-9 mRNA transcript expression in the duodenum. *p<0.050 compared to FA, †p<0.050 compared to MVE, using a one way ANOVA. Scale bar = 200 μm.

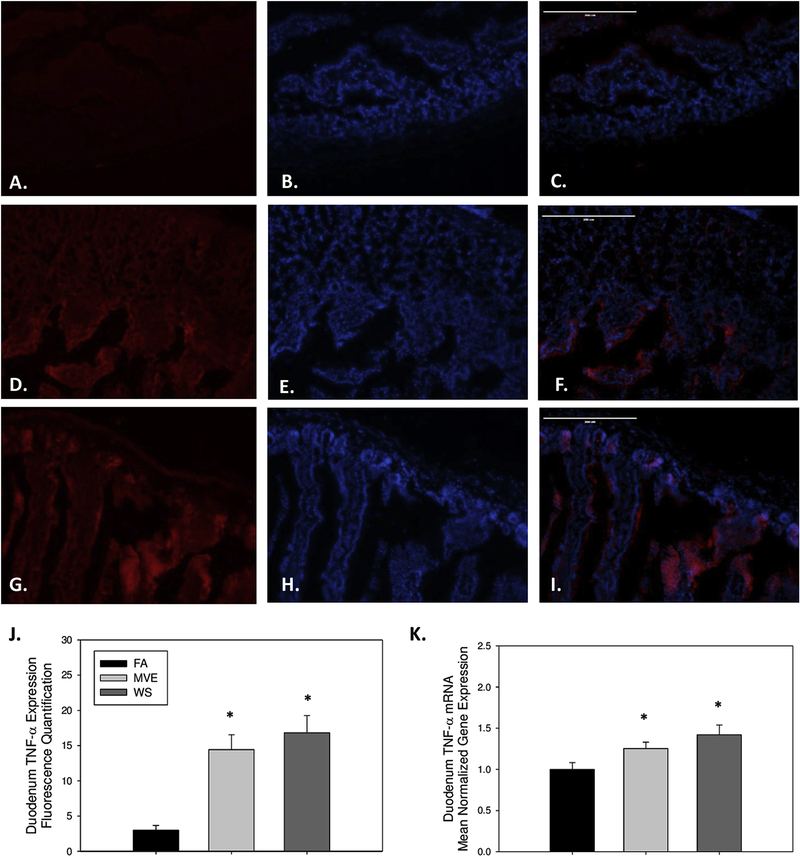

3.3. Alteration in expression of markers of inflammation, Muc-2, and TLR-4 in the duodenum of ApoE−/− mice exposed to either MVE or WS.

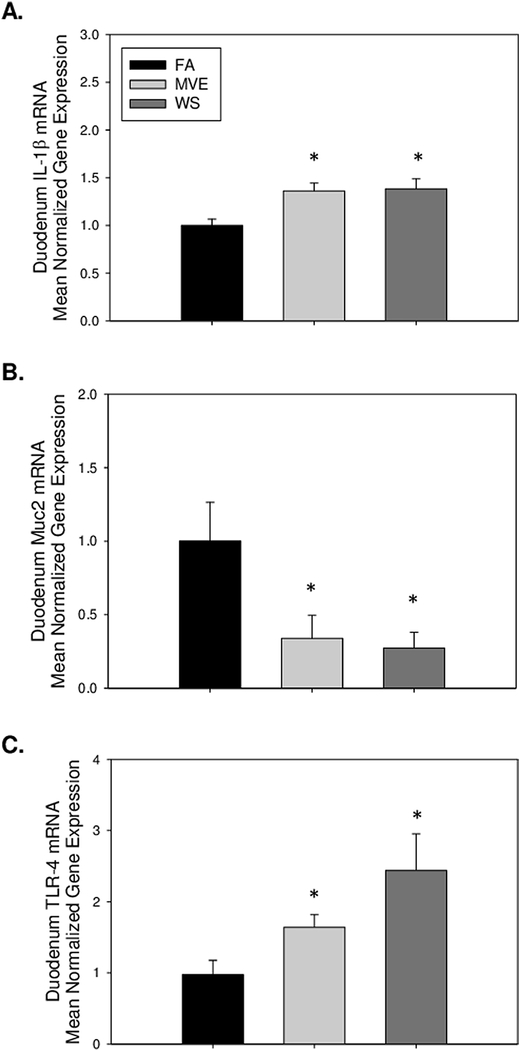

To determine whether there was an inflammatory response at the duodenum of the ApoE−/− mice, on a Western diet, related to inhaled MVE or WS, we examined the expression of inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-1β. Compared to FA controls (Figs. 4A–C), we observed a significant increase in the inflammatory signaling mediator TNF-α in the duodenum of both MVE- (Figs. 4D–E, p<0.001) and WS-exposed (Figs. 4G–I, p<0.001) mice, as quantified in Fig. 4J. These findings were in agreement with duodenum TNF-α mRNA transcript expression (Fig. 4K). IL-1β mRNA expression was also significantly increased in the duodenum of both WS- and MVE-exposed animals, compared to FA controls (Fig. 5A), indicating these inhalation exposures induced local inflammation in the gut of exposed animals.

Figure 4.

Representative images of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α expression in the duodenum of Apo E−/− mice, on a Western diet exposed to either (A-C) filtered air, (D-F) mixed exhaust (MVE; 300μg/m3 PM), or (G-I) 440 μg/m3 PM wood smoke (WS: ~440μg/m3 PM). Red fluorescence indicates TNF-α expression, blue fluorescence is nuclear staining (Hoescht). (J) Graph of histology analysis of duodenal TNF-α fluorescence. (K) RT-qPCR analysis of TNF-α mRNA transcript expression in the duodenum. *p<0.050 compared to FA using a one way ANOVA. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure 5.

Real-time RT-qPCR analysis of duodenal mRNA expression of (A) interleukin (IL)-1β, (B) Mucin (Muc)-2, and (C) Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 in the duodenum of ApoE−/− mice on a Western diet exposed to either filtered air (FA), mixed exhaust (MVE; 300μg/m3 PM), or wood smoke (WS: ~440μg/m3 PM). Data are mean normalized gene expression using ΔΔCT values, with GAPDH used as the house-keeping gene. * p<0.050 compared to FA using a one way ANOVA.

We analyzed the levels of Muc2, which is involved in mucus production in the IEB since the production of mucus in the small intestine serves as both protection at the IEB and lubrication between the luminal contents and the epithelial barrier. With our inhalation exposures, compared to FA controls, we observe duodenal Muc2 mRNA expression to be significantly downregulated in the MVE- and WS-exposed Apo E−/− mice (Fig. 5B).

TLR-4 is known to be expressed on immune and epithelial cells that line the intestine and is believed to play a role in the intestinal mucosal host defense against the microbiota that inhabits the intestine. We observed a statistical increase in TLR-4 mRNA expression in the duodenum of both WS- and MVE-exposed animals, compared to FA control animals (Fig. 5C), the induction of which is even further pronounced in the duodenum of WS-exposed animals.

3.4. Alterations in small intestine microbial profiles resulting from exposure to MVE or WS in ApoE−/− mice.

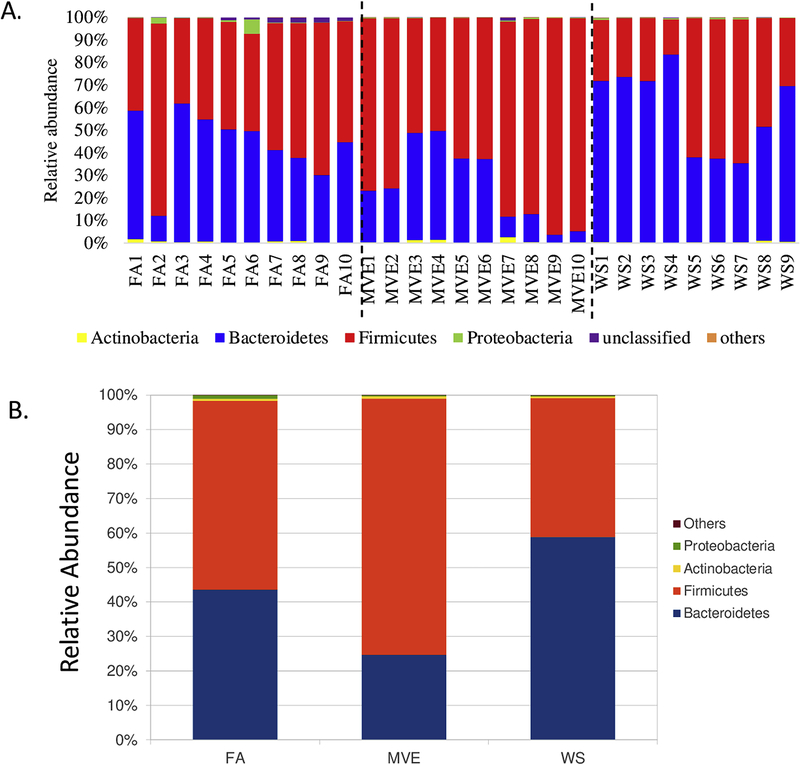

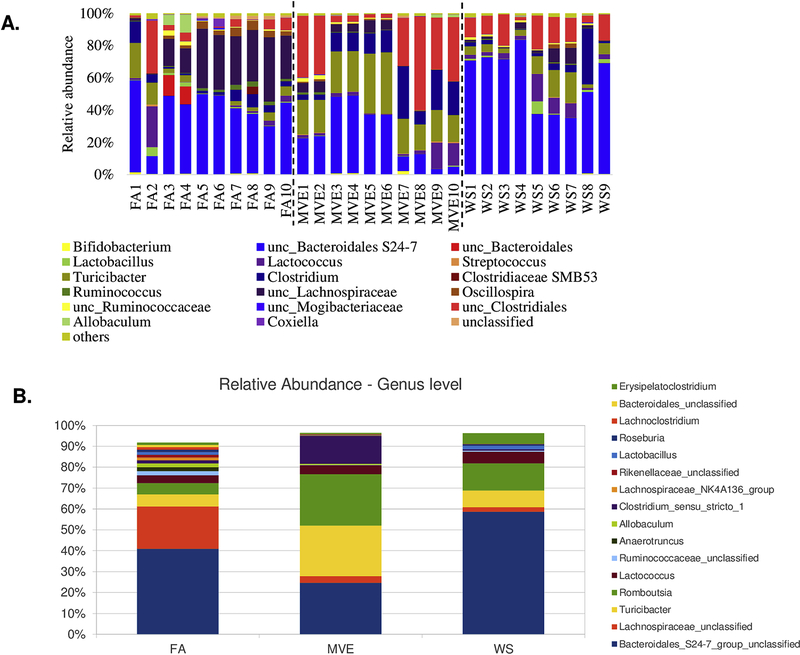

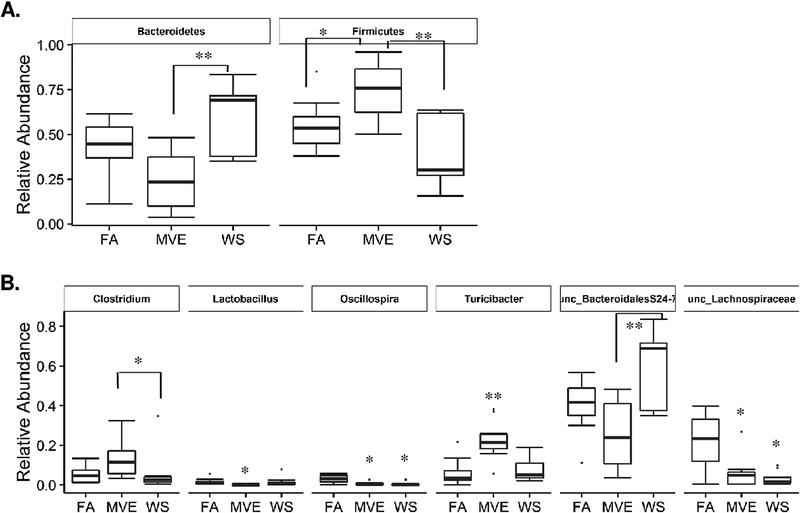

To determine whether a microbiome shift within the intestines could be associated with IEB integrity and localized inflammation within the gut of the MVE and WS-exposed ApoE−/− mice, we analyzed the bacterial microbiome profiles in the ileum of our study animals using 16S Illumina sequencing. The graphs in Figure 6 show the phyla-level individual (Fig. 6A) and group average (Fig. 6B) microbiota profiles present in the ileum for the FA control, MVE- and WS-exposed groups. The major phyla represented across all animals were the phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes; however, these were observed to have different ratios across the FA, MVE, and WS-exposed groups (Figs. 6A and B). And while there is some intra-sample variability amongst the animals in each group, there is a notable increase in Firmicutes over Bacteroidetes (F/B ratio) in the ileum of MVE-exposed ApoE−/− mice, with the inverse result observed in the WS-exposed ApoE−/− mice, where there is a decreased F/B ratio; compared to the almost 50:50 F/B ratio observed in the ileum of the ApoE−/− FA control group (Fig. 6B). The graphs in Figure 7 show the individual (Fig. 7A) and average group genus-level (Fig. 7B) microbiota profiles present in the ileum for the FA control, MVE-, and WS-exposed groups. At the genus-level, visibly abundant across all individuals was unclassified Bacteroidales S24–7 group (Figs. 7A and B). The common thread of unclassified Bacteroidales S24–7 averages around ~40% in the control, while MVE decreases to ~24%, and WS has the inverse result of increasing BS24–7U to ~59%. Noteworthy is the increased levels of various Clostridia, Turcibacter, and Romboutsia genera, and decreased levels of unclassified Lachnospiraceae genera in the MVE and WS exposed animals, compared to the FA controls (Fig. 7B).

Figure 6.

Study group phylum level individual (A) and group average (B) microbial profiles, as determined from MiSeq sequencing from DNA extracted from the ileum of ApoE−/− mice on a Western diet exposed to either filtered air (FA) control; mixed vehicle exhaust (MVE; 300μg/m3 PM); or wood smoke (WS; ~440μg/m3 PM) for 6 hr/day, 7 day/wk, for 50 days.

Figure 7.

Study group genus level individual (A) and group average (B) microbial profiles, as determined from MiSeq sequencing from DNA extracted from the ileum of ApoE−/− mice on a Western diet exposed to either filtered air (FA) control; mixed vehicle exhaust (MVE; 300μg/m3 PM); or wood smoke (WS; ~440μg/m3 PM) for 6 hr/day, 7 day/wk, for 50 days.

3.5. MVE- and WS-Exposure Mediates Significant Reductions in Microbial Diversity in the Small Intestine of ApoE−/− Mice.

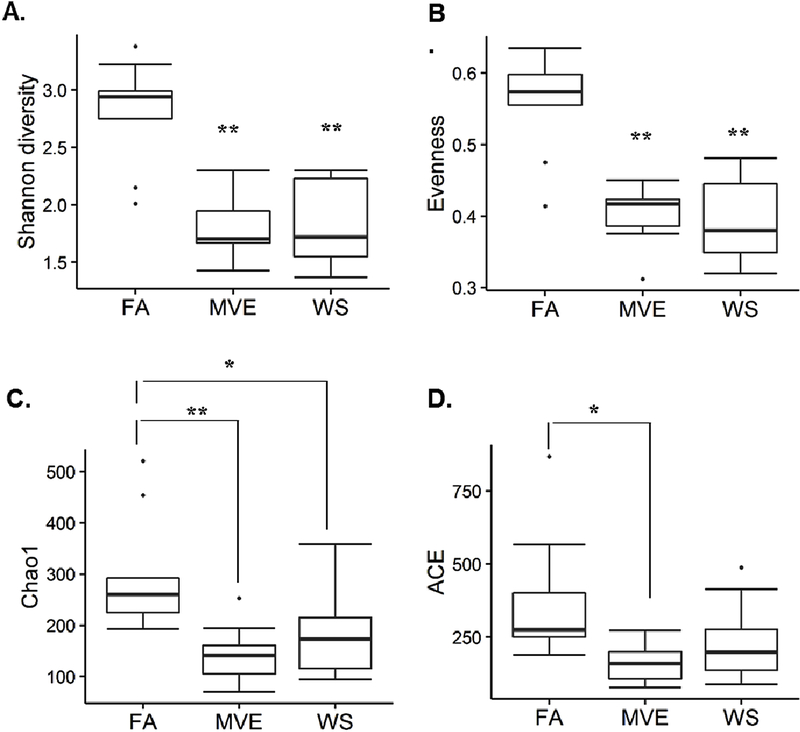

To determine exposure-mediated shifts in microbial diversity in the ileum of our MVE- and WS-exposed animals, compared to the FA controls, we conducted both α-diversity (the diversity within communities) and β-diversity calculations. The resulting alpha diversity analyses of microbial diversity between the control and exposures groups were calculated using the Shannon (diversity) Index (Fig. 8A), Evenness (Fig. 8B), Chao1 (richness) Index (Fig. 8C), and ACE (richness) (Fig. 8D), each of which showed a decreased diversity in the MVE and WS-exposure groups when compared to FA controls. Notably, we observed a statistical decrease in ileum bacterial diversity and richness in ApoE−/− mice exposed to MVE using the Shannon, Evenness, Chao1 Index, and ACE metrics (Figs. 8A, B, C, and D respectively; p<0.050), compared to FA control animals. Similar results were observed in the WS-exposed animals, showing statistical decreases in Shannon, Evenness, and Chao1 indices (Figs. 8A, B, C, respectively; p<0.050), compared to FA controls. Interestingly, while there was some intra-group variability, there were very little observable differences in these alpha diversity measurements noted between the MVE and WS exposure groups.

Figure 8.

Alpha diversity analysis compared between filtered air (FA) control and exposure [mixed vehicle exhaust (MVE; 300μg/m3 PM); wood smoke (WS; ~440μg/m3 PM) for 6 hr/day, 7 day/wk, 50 days.] ApoE−/− mice, on a Western diet, using (A) Shannon Index (diversity), (B) Evenness (diversity), (C) Chao1 Index (richness), and (D) Abundance Coverage-based Estimator (ACE; richness) metrics, based on OTU grouped at 97% sequences similarity for species-level classification. *p<0.050 compared to FA; **P<0.01, via Tukey HSD analysis. Note: sample FA6 was removed from analyses due to low total sequence count.

We also observed differences in β-diversity in ileum microbiota profiles between our control and exposure groups. Figure 9A is an unweighted PCoA plot, based on unweighted UniFrac distance, which shows the fraction of the total variance in bacteria represented by each of the axes. Each dot represents one animal in each of three control/exposure groups (FA, MVE, or WS), as indicated by the legend. The PCoA chart in Figure 9A shows some clustering and mixing between the exposures MVE and WS, with the FA control samples dispersed away from the exposures. Once data are weighted in Figure 9B, clustering becomes clearer between the individuals of each control or exposure group, with minimal overlap. The Analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) provide both a p value and an R value, where an R value closer to 0 indicate no separation and values closer to 1 indicate high separation (or dissimilarities) across exposure groups. When considering the presence or absence of bacterial species, the ANOSIM comparison for bacterial communities among different groups showed limited separation between exposure groups (Fig. 9A: R = 0.264, p <0.001); however, separation between exposure groups was improved when using the weighted abundance of bacterial species (Fig. 9B: R = 0.373, p<0.001). When analyzed by Analysis of Molecular Variance (AMOVA), based on both unweighted (Table 1) and weighted (Table 2) UniFrac distance shows a p-value of <0.001 – 0.006 between groups, with the strongest differentiation between the FA and either MVE or WS exposed.

Figure 9.

Beta diversity was calculated using UniFrac distances and Principle Coordinates Analysis plots that show the degree by which membership or structure is shared between microbial communities in both (A) unweighted and (B) weighted analyses. Each circle represents one animal in each of the filtered air (FA) control or exposure [mixed vehicle exhaust (MVE; 300μg/m3 PM); wood smoke (WS; ~440μg/m3 PM); exposed for 6 hr/day, 7 days/wk, 50 days total] ApoE−/− mice groups. Note: sample FA6 was removed from analyses due to low total sequence count.

Table 1.

Unweighted AMOVA analysis of Microbiota Profiles from Ileum of ApoE−/− Mice Exposed via Inhalation to Air Pollution.

| Exposure Groups | Df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | Fs | P- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA vs. MVE: | 1.85 | 0.001 | |||

| - Among groups | 1 | 0.455 | 0.455 | ||

| - Within groups | 17 | 4.18 | 0.246 | ||

| - Total | 18 | 4.64 | |||

| FA vs. WS: | 1.86 | 0.001 | |||

| - Among groups | 1 | 0.460 | 0.460 | ||

| - Within groups | 16 | 3.96 | 0.248 | ||

| - Total | 17 | 4.42 | |||

| MVE vs. WS: | 1.4482 | 0.002 | |||

| - Among groups | 1 | 0.328 | 0.328 | ||

| - Within groups | 17 | 3.85 | 0.227 | ||

| - Total | 18 | 4.18 |

FA, filtered air (controls); MVE, mixed vehicle exhaust; WS, wood-smoke; Df, degrees of freedom; Sum Sq, sum of squares; Mean Sq, mean of squares.

Table 2.

Weighted AMOVA analysis of Microbiota Profiles from Ileum of ApoE−/− Mice Exposed via Inhalation to Air Pollution.

| Exposure Groups | Df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | Fs | P- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA vs. MVE: | 7.82 | 0.003 | |||

| - Among groups | 1 | 0.290 | 0.290 | ||

| - Within groups | 17 | 0.630 | 0.037 | ||

| - Total | 18 | 0.920 | |||

| FA vs. WS: | 4.43 | 0.006 | |||

| - Among groups | 1 | 0.264 | 0.264 | ||

| - Within groups | 16 | 0.952 | 0.0595 | ||

| - Total | 17 | 1.22 | |||

| MVE vs. WS: | 11.18 | 0.001 | |||

| - Among groups | 1 | 0.471 | 0.471 | ||

| - Within groups | 17 | 0.717 | 0.0422 | ||

| - Total | 18 | 1.19 |

FA, filtered air (controls); MVE, mixed vehicle exhaust; WS, wood-smoke; Df, degrees of freedom; Sum Sq, sum of squares; Mean Sq, mean of squares.

We found two bacterial phyla and six bacterial genera had significant differences between different treatments using the Kruskal-Wallis test (Fig. 10). The post hoc Dunn’s test suggested that Bacteroidetes abundance in MVE-exposed mice was significantly lower than in WS-exposed mice (p = 0.004). The relative abundance of Firmicutes in MVE-exposed mice was significantly higher than in FA control (p = 0.05) and WS-exposed mice (p = 0.003) (Fig. 10A). FA control mice had the highest amount of unc_Lachnospiraceae and Oscillospira among the three different exposure groups (p <0.05) (Fig. 10B). MVE-exposed mice had the highest amount of Turicibacter (p <0.01) and the lowest amount of Lactobacillus (p <0.05) (Fig. 10). The MVE-exposed mice had a significantly higher abundance of Clostridium (p = 0.02) and lower abundance of Bacteroidales S24–7 (p = 0.007) compared to the WS-exposed mice (Fig. 10B).

Figure 10.

Effects of inhaled filtered air (FA), wood-smoke (WS), and mixed diesel and gasoline vehicle exhaust (MVE) on the relative abundance of gastrointestinal bacteria at the (A) phylum level, and (B) genus level in ApoE−/− mice. Dots are outliers; * p < 0.05; * * p < 0.01 compared to FA controls, as determined by a Kruskal-Wallis post-hoc Dunn’s test.

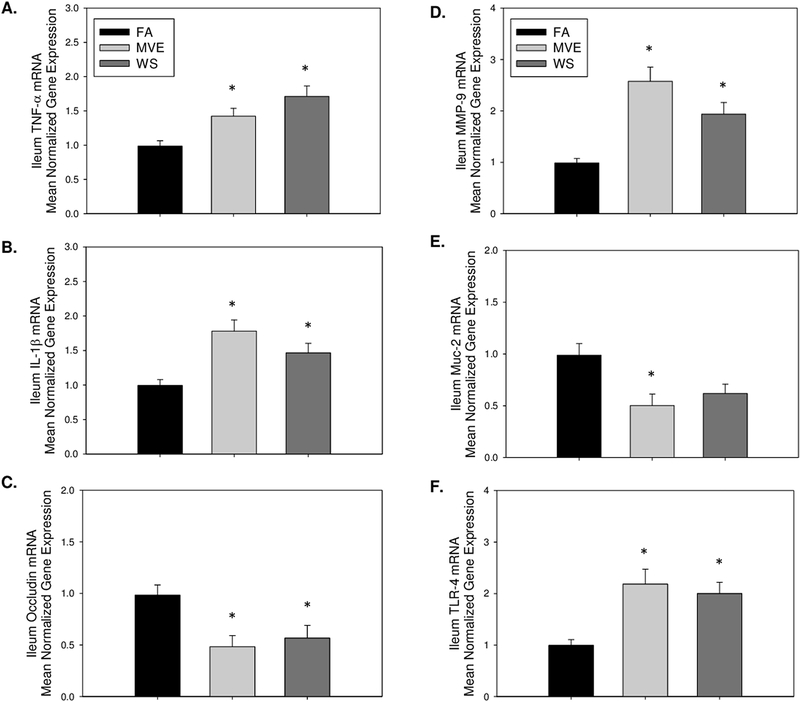

3.6. MVE- and WS-exposure alters transcript expression of factors associated with IEB integrity, inflammatory markers, and MMP-9, in the ileum of ApoE−/− mice.

Since the ileum was used for the microbiome diversity analyses, due to the increased relative abundance of microbiota in that region, we also wanted to analyze the expression of those endpoints we found significantly altered in the duodenum related to IEB integrity and inflammation. In agreement with results reported in the duodenum, compared to FA controls, we observe an increase in transcript level expression of inflammatory factor TNF-α in the ileum of both MVE- (p=0.004) and WS-exposed (p =0.020) Apo E−/− mice (Fig. 11A); however, IL-1β mRNA is only statistically increased in ileum of MVE-exposed mice (Fig. 11B, p<0.001), when compared to FA controls. This increase in inflammation in the ileum was also associated with a decrease in expression of occludin (Fig. 11C) in both MVE (p=.0.014) and WS (p=0.043) exposure, compared to FA controls, and also significantly elevated MMP-9 (Fig. 11D) in the ileal tissue of exposed ApoE−/− mice (MVE, p =<0.001; WS, p=0.012), suggesting these environmental exposures may alter the IEB integrity in the ileum. Notably, compared to FA controls, Muc2 mRNA expression was only significantly altered in the ileum of MVE-exposed mice (Fig. 11E, p=0.010), whereas the decrease in ileal Muc2 mRNA in the WS-exposed animal was not statistically different from FA control (Fig. 11E, p=0.054). Finally, we observe TLR-4 mRNA to be significantly elevated in the ileum of ApoE−/− mice (Fig. 11F) exposed to either MVE (p=0.003) or WS (p=0.010) compared to FA controls.

Figure 11.

Real-time RT-qPCR analysis of ileum mRNA expression of (A) tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α; (B) interleukin (IL)-1β; (C) occludin; (D) matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9; (E) mucin (Muc)-2, and (F) Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 in the ileum of ApoE−/− mice on a Western diet exposed to either filtered air (FA), mixed exhaust (MVE; 300μg/m3 PM), or wood smoke (WS: ~440μg/m3 PM). Data are mean normalized gene expression using ΔΔCT values, with GAPDH used as the house-keeping gene. * p<0.050 compared to FA using a one way ANOVA

4. Discussion.

In addition to CVD, recent reports suggest that air pollution may contribute to gastrointestinal diseases, with epidemiological studies associating high air pollution days with a 40% increase in IBD hospitalizations (Ananthakrishnan et al, 2011). Furthermore, multiple studies have shown a correlation between gut microbiota composition and progression of CVD (rev. in Ahmadmehrabi and Tang, 2017 and Peng et al., 2018). Despite this evidence, studies that examine intestinal outcomes following inhalation exposures to environmental air pollution are still minimal. However, at least one report shows a strong association between exposure to air pollution particulate matter and increased atherogenic lipid metabolites in an atherosclerotic mouse model (Li et al., 2017). Importantly, we used an atherogenic mouse model, the ApoE−/− mouse on a high fat “Western” diet, for this study because we have previously extensively analyzed cardiovascular outcomes related to either MVE or WS exposure and have reported results that show enlarged plaque growth and complexity and/or increased expression of signaling in the vasculature that is associated with the pathogenesis of CVD (Campen et al., 2010; Campen, 2012; Lund et al., 2009; Lund et al., 2011; Mauderly et al., 2014; Sielkop et al., 2012). Additionally, utilizing this model also allowed for us to: (1) reflect the baseline atherosclerosis associated with the standard Western diet (typically >30% fat) present in much of the human population; and (2) determine additive and/or synergistic effects of inhaled air pollutants, combined with underlying cardiovascular disease and a high fat diet, which is also representative of a large percentage of the population in developed countries. However, this is also a limitation of the current study since Western diets, alone, have been reported to cause shifts in microbiota profiles in the gut (Agus et al., 2016). It is important to note that these exposures did affect animal body weight (Fig. S1), as we observed less growth in the MVE- (28.1 ± 3.1g SD) and WS- (29.4 ± 2.2 g SD) exposed animals, compared to FA (32.2 ± 3.0g SD).

There are at least two plausible routes for inhaled environmental air pollutants to have effects on the gut: (1) through gases, fine, and/or ultrafine particles (≤PM2.5) being inhaled deep into the lung, crossing the respiratory membrane and/or inducing systemic inflammatory factors, which can be delivered to the highly vascularized gut; and (2) via ingestion of PM that is caught and brought up the mucociliary tract, or trapped in the oropharyngeal region, and subsequently swallowed. Interestingly, while different in concentration and chemical characteristics, we did not observe any significant differences between the MVE- and WS-exposure groups in our chosen endpoints.

Considering IEB integrity is an integral part of intestinal health, we analyzed various components of the IEB; namely TJ proteins, mucins (Muc2), and MMP-9. For TJ protein expression, we chose three that are known to be abundantly expressed in the intestines: occludin and claudin-3 are known to be important in TJ assembly and maintenance, while claudin-2 forms aqueous pores in the epithelium, regulating selective permeability (Krause et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2013). Our results show a significant decrease in occludin in the intestine with MVE-exposures at the protein and mRNA levels and WS-exposure at the mRNA level. While claudin-3 has a similar role to occludin and maintains the “tightness” between the TJ proteins, expression was found to be upregulated within both exposures at the transcript and protein levels in the MVE- and WS-exposed groups, compared to controls. This may be due to either regulatory feedback signaling or the ability of certain pollutants to cause a microflora shift that can increase the presence of a commensal bacterium involved in TJ protein regulation. For example, a recent study suggested cigarette smoke to have a beneficial role in IEB integrity, despite causing systemic inflammation and increased oxidative stress (Allais et al., 2016). Importantly, claudin-3 expression has been linked to colorectal cancer (CRC), with increased levels of claudin-3 even considered as a diagnostic marker for CRC (Krause et al., 2008). Considering TJ proteins typically function synergistically, along with other junctional proteins, an individual assessment of one TJ protein may not be representative of the whole (Edelblum and Turner, 2009; Lu et al., 2013).

We also analyzed the mRNA expression of mucus-forming Muc2, in the intestines of our exposure animals. The mucus layer of the intestine, composed of the outer layer where the commensal bacteria live, and an inner layer, which acts as a buffer zone between the lamina propria and commensal cells, are primarily made of Muc2-derived mucins that are secreted by goblet cells (Johansson et al., 2011). Our results demonstrate a marked decrease in Muc2 mRNA in the duodenum and ileum of the MVE-exposed ApoE−/− mice. Lack of Muc2 causes defective mucous layers, which can result in increased bacterial adhesion to the epithelial cell surface, intestinal permeability, and/or inflammation, although these endpoints were not assessed in the current study. Correlated with the observed decrease in intestinal Muc2 expression, we observed a significant increase in inflammatory mediators TNFα, IL-1β, and TLR-4 in the duodenum and ileum of our MVE- and WS-exposed animals, compared to FA controls. Importantly, baseline TLR4 expression is fairly low; however, if there is a disruption at the epithelium TLR4 is upregulated resulting in recruitment of inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-1β (Frosalia et al., 2015; Villena and Kitazawa, 2013). Collectively, the effects of inhaled air pollution exposure on the intestines exhibit similar inflammatory signaling outcomes as those reported in the cardiopulmonary and central nervous systems (Miyata and van Eeden, 2011; Pope et al., 2016; Woodward et al., 2017).

MMP’s mediate tissue remodeling and wound healing, and can be expressed by almost all connective tissue cells in the bowel in response to inflammatory stimuli including TNFα and IL1β. Specifically, MMP-9 is a gelatinase and collagenase implicated in inflammatory pathologies, including IBD (Edelblum and Turner, 2009; Lu et al., 2013; O’Sullivan et al., 2015). MMP-9 released from intestine epithelial cells during inflammation is implicated in the degradation of mucosal integrity and TJ proteins (Nighot et al., 2015). Importantly, exposure to traffic-generated air pollution has been shown to increase MMP-9 expression and activity systemically, as well as in the vasculature (Lund et al., 2009; Oppenheim et al., 2012; Suwannasual et al., 2018). Our results show an upregulation of MMP-9 expression in the duodenum and ileum of both the MVE and WS exposure groups, which is associated with altered TJ protein expression and mucin degradation.

Many intestinal inflammatory diseases, such as IBD, are linked to microbiota dysbiosis in the small intestine (Sun and Chang, 2014). However, most studies published to date use fecal matter and/or colon samples for microbiota profiling, which may not be indicative of the complex host/microbiome interplay within the intestines themselves. We analyzed the microbiota profile of the ileum, which is characterized as the transitional area between the aerobic conditions of the upper GI tract, and the anaerobic conditions of the large intestines; also reported to have the largest diversity of commensal bacteria (Guarner and Malagelada, 2003). At the phylum level, we observed marked differences between the exposures and controls in relative abundance of the ratio of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (F/B), with FA expressing an F/B ratio of approximately 1:1, MVE having a significant increase of Firmicutes with an F/B ratio of 3:1, and WS having the inverse effect with an F/B ratio of 1:2, as shown in Figure 10A. Recent studies on the effects of air pollution on gut microbiome profiles in wildtype mice have also shown increases in Bacteroidetes at the phylum level with ambient PM exposure (Mutlu et al., 2018) and decreased Bacteroides at the genus and Bacteriodaceae at the family level with traffic-generated pollutant exposure in humans (Alderete et al., 2018). Conflicting results in the literature on air pollution-mediated alterations in relative ratios of gut microbiota at different taxonomic levels are likely due to different sampling for analyses (fecal material vs. intestines), different species, the concentration and route of exposure, and/or the chemical composition of the pollutants being studied. Regardless, multiple studies have attributed phyla shift resulting in an increased F/B ratio to insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, obesity, and inflammatory diseases in studies on both children and adults (Jandhyala et al., 2017; Kasai et al., 2015; Ley et al., 2006; Moreno-Indias et al, 2016; Riva et al., 2017).

To gain a further understanding of the bacteria within the gut after exposure, we assessed the bacterial shift at the genus level. The top bacteria present in the controls were unclassified Bacteroidales_S24–7 and unclassified Lachnospiracae, which encompassed 66% of the total bacteria present. The FA control had the largest amount of unclassified Lachnospiracae and unclassified Ruminococcaceae, which are both recognized as beneficial bacteria for the maintenance of mammalian gut health (Johansson et al., 2011). Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae are known to be producers of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), which enterocytes use as an energy source that contributes to the maintenance of the IEB. On the other hand, depletion of Lachnospiraceae, as observed in the intestines of the WS and MVE-exposed mice, has been associated with IBD and CRC (Biddle et al., 2013). The exposures showed a marked difference with WS showing a significant increase in unclassified Bacteroidales_S24–7 (~60% of overall bacterial presence). Conversely, the MVE exposure resulted in decreased unclassified Bacteroidales, with top bacteria present being Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1, Rombautsia, and Turicibacter, as shown in Figure 10B. Many Clostridia species are beneficial commensals; however, there is evidence to suggest that Clostridium from cluster 1 can be pathogenic, and can overpopulate the mucosal lining, given the opportunity (Lopetuso et al., 2013); however, the exact role of these bacteria at the genus level is not yet fully characterized. There is also a noticeable decrease in Lactobacillus present in the ileum from MVE-exposed animals, compared to FA controls. These findings are in agreement with previous reports that show that ambient PM inhalation exposures result in a decrease of the Lactobacillus genus in the intestines of C57Bl/6 wild-type mice (Mutlu et al., 2018). A decrease of intestinal Lactobacillus has been associated with multiple human disease states, including IBS, colon cancer, obesity, and multiple sclerosis (rev. in Heeney et al., 2018). As such, it is important to gain a further understanding of how exposure to environmental air pollutants may alter the profile of beneficial vs. pathogenic microbes in the GI tract, both in those with baseline CVD and in otherwise healthy individuals.

When looking at weighted PCoA analysis, the results show distinct clustering of each study group, suggesting specific microbial shifts due to exposures. Diversity results between both Shannon Index and Evenness suggest a much lower diversity for the MVE- and WS-exposure groups. Considering these indexes may not take into account bacterial presence of <1%, and that some studies suggest that the bacteria that represent under 1% of the total microbiome may be associated with significant host/microbial functions (Nguyen et al., 2015), we analyzed microbial richness. Compared to the FA control, both MVE and WS-exposures had much lower richness. While further investigation is needed, this decreased microbial richness may be due to an exposure-mediated microbiome shift that results in overgrowth of opportunistic bacteria, replacing the commensals that normally regulate intestinal integrity and immune system regulation.

The series of events that occurs between air pollution insult, inflammation, IEB disruption, and microbiome shift is not fully clear; however, these results suggest that the mechanism of dysbiosis may differ between MVE and WS, which is likely due to the characteristics of the components of each (e.g. gases, PM, etc.). As a foundational study, this project reports significant effects of inhaled air pollution (mixtures)-mediated inflammation, and alterations on the IEB and microbiota profiles; however, it is important to note limitations. These study findings are taken from only one time point (subchronic 50d exposure) and thus did not capture results across multiple time points. Additionally, while we have previously reported exposure to these pollution mixtures results in increased atherogenic signaling and plaque growth, we did not investigate that endpoint in the current study. While we did assess components associated with the structure of the IEB, we did not directly assess intestinal permeability in these animals. Finally, the concentrations of MVE and WS used in this study would be considered very high on the real-world air quality index (AQI) air pollution scale. However, the utilized levels of PM in the MVE are translatable to high occupational exposures, and/or near-roadway exposures during peak traffic, as well as those experienced globally in urban areas, such as New Dehli, India, that have a yearly average <300 μg/m3 of PM2.5 (WHO Ambient Air Pollution Database, 2016). It is estimated that 5–20% of WS is particulate mass. The levels of PM for the WS exposures in the current study are within the range of estimates for 24 hr PM levels in rural households and developing countries that burn biomass in open fireplaces or stoves which are not airtight (300 – 3000 μg/m3; reported to be as high as 30,000 μg/m3 during periods of cooking) (Bruce et al., 2000; Ezzati and Kammen, 2002).

5. Conclusions.

Our study findings demonstrate that inhalation exposure to ubiquitous environmental air pollutants, from either traffic generated or wood-burning sources, increases intestinal inflammatory markers, correlated with altered expression of factors that are known to contribute to the integrity of the intestinal barrier. Effects of WS on inflammatory factors and MMP-9 expression were greater than that observed in MVE exposures, suggesting that different characteristics of the components that comprise either WS or MVE (including PM type) mediate inflammation and alterations in IEB differently. Additionally, both MVE and WS-exposures resulted in significantly decreased ileal bacterial diversity, as well as bacterial profiles that were quite distinct from one another, including shifts in the F/B ratios that have been associated with metabolic and inflammatory disease states in humans. Considering that air pollution is currently attributed to 7.4 million premature deaths a year (WHO Ambient Air Quality and Health Report, 2016), and is associated with inflammatory diseases such as cardiopulmonary disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, and autoimmune disorders (Alderete et al., 2017, 2018; Campen et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2016), understanding the role of intestinal health and microbiota profiles as a possible contributor to these disease states is imperative to further characterize the mechanistic pathways involved in the detrimental effects of inhaled environmental air pollution on human health.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Inhaled air pollutant-exposure promotes inflammation in the gut of ApoE−/− mice.

Vehicle emissions (MVE) and wood-smoke (WS) exposure alter markers of gut integrity.

Inhaled MVE and WS alter intestine microbiota profiles and decrease overall diversity.

Intestine Firmicutes: Bacteroidetes ratios are changed due to MVE or WS exposures.

Acknowledgements.

We would like to thank the Chemistry and Inhalation Exposure group, in the Environmental Respiratory Health Program, at Lovelace Biomedical and Environmental Research Institute for the characterization and monitoring of the animal exposures. We would like to thank Karly Flemmons at UNT for assistance with the intestine real-time PCR experiments.

Funding.

This work was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at the National Institute of Health [ES014639 to MJC.] for the animal exposures, and the University of North Texas Research Initiation Grant (RIG) [GA93601 to A.K.L] for the DNA sequencing and tissue analysis. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

All procedures were approved by the Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute’s Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol # FY15-023A) and conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Abbreviations.

- ANOSIM

Analysis of similarities

- AMOVA

Analysis of molecular variance

- ApoE−/− mice

Apolipoprotein E null mice

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- FA

filtered air (controls)

- F/B

Firmicutes : Bacteroidetes ratio

- IEB

intestine epithelial barrier

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1 beta

- JAMs

junction adhesion molecules

- LPS

lipopolysaccharides

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- Muc2

mucin 2

- MVE

mixed gasoline and diesel vehicle exhaust

- PCoA

principle coordinates analysis

- PM

particulate matter

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TJ

tight junction proteins

- TLR-4

Toll-like receptor

- TNF- α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- WS

wood smoke

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interests.

Funding from grants received from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at National Institute of Health and University of North Texas were used to conduct some of the exposures and studies described, herein; however, the authors declare no conflict of interest or financial gains to these entities associated with this publication.

References.

- Agus A, Denizot J, Thévenot J, Martinez-Medina M, Massier S, Sauvanet P, Bernalier-Donadille A, Denis S, Hofman P, Bonnet R, et al. , 2016. Western diet induces a shift in microbiota composition enhancing susceptibility to Adherent-Invasive E. coli infection and intestinal inflammation. Sci. Rep 6, 19032. doi: 10.1038/srep19032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadmehrabi S, and Wilson Tang WH, 2017. Gut Microbiome and its Role in Cardiovascular Diseases. Curr. Opin. Cardiol 32, 761–766. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderete TL, Habre R, Toledo-Corral CM, Berhane K, Chen Z, Lurmann FW, 2017. Longitudinal associations between ambient air pollution with insulin sensitivity, β-Cell function, and adiposity in Los Angeles Latino Children. Diabetes 66, 1789–1796. doi: 10.2337/db16-1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderete TL, Jones RB, Chen Z, Kim JS, Habre R, Lurmann F, Gilliland FD, Goran MI, 2018. Exposure to traffic-related air pollution and the composition of the gut microbiota in overweight and obese adolescents. Environ. Res 161, 472–478. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allais L, Kerckhof FM, Verschuere S, Bracke KR, De Smet R, Laukens D, Van den Abbeele P, De Vos M, Boon N, Brusselle GG, et al. , 2016. Chronic cigarette smoke exposure induces microbial and inflammatory shifts and mucin changes in the murine gut. Environ Microbiol 18, 1352–1363. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A, Dwivedi G, O’Gara F, Caparros-Martin J, Ward N, 2019. The gut microbiome and atherosclerosis: current knowledge and clinical potentials. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (epub ahead of print) 10.1152/ajpheart.00376.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Binion DG, Saeian K, 2011. Ambient air pollution correlates with hospitalizations for inflammatory bowel disease: an ecologic analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 17:1138–1145. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI, 2005. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science 307, 1915–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin EJ, Virani S, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, et al. , 2018. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics – 2018 Update: A report for the American Heart Association. Circulation 137, e67–e492. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddle A, Steward L, Blanchard J, Leschin S, 2013. Untangling the genetic basis of fibrolytic specialization by lachnospiraceae and ruminococcaceae in diverse gut communities. Diversity 5, 627–640. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce N, Perez-Padilla R, Albalak R, 2000. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: a major environmental and public health challenge. Bull. World Health Organ 78: 1078–1092. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caesare R, Fak F, Backhed F, 2010. Effects of gut microbiota on obesity and atherosclerosis via modulation of inflammation and lipid metabolism. J. Intern. Med l268, 320–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campen MJ, Lund AK, Knuckles TL, Conklin DJ, Bishop B, Young D, Seilkop S, Seagrave J, Reed MD, McDonald JD, 2010. Inhaled diesel emissions alter atherosclerotic plaque composition in ApoE−/− mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 242, 310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campen MJ, Lund A, Rosenfeld M, 2012. Mechanisms linking traffic-related air pollution and atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med 18, 155–160. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32834f210a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale R, Nocella C, Petrozza V, Cammisotto V, Pacini L, Sorrentino V, Martinelli O, Irace L, Sciarretta S, Frati G, Pastori D, Violi F, 2018. Localization of lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia Coli into human atherosclerotic plaque. Sci. Rep 8, 3598. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22076-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao A, 1984. Nonparametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scandinavian J. Stats 11, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Chazdon RL, Colwell RK, Denslow JS, Guariguata MR, 1998. Statistical methods for estimating species richness of woody regeneration in primary and secondary rain forests of Northeastern Costa Rica. Forest biodiversity research, monitoring and modeling: conceptual background and old world case studies, (Dallmeier F & Comiskey JA, Eds.), Parthenon Publishing, Paris, France, pp. 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke KR, 1993. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Derrien M, vanPassel MW, van de Bovenkamp JH, Schipper RG, de Vos WM, Dekker J, 2010. Mucin-bacterial interactions in the human oral cavity and digestive tract. Gut Microbes 1, 254–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas ME, Barton RH, Toye A, Cloarec O, Blancher C, Rothwell A, Fearnside J, Tatoud R, Blanc V, Lindon JC, 2006. Metabolic profiling reveals a contribution of gut microbiota to fatty liver phenotype in insulin-resistant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 303, 12511–12516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelblum KL, Turner JR, 2009. The tight junction in inflammatory bowel disease: Communication breakdown. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 9, 715–720. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R, 2011. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati M, and Kammen DM, 2002. The health impacts of exposure to indoor air pollution form solid fuels in developing countries: knowledge, gaps, and data needs. Environ. Health Perspect 110: 1057–1068. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021101057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festi D, Schiumerini R, Eusebi LH, Marasco G, Taddia M, Colecchia A, 2014. Gut microbiota and metabolic syndrome. World J. Gastroenterol 20, 16079–16094. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosali S, Pagliari D, Gambassi G, Landolfi R, Pandolfi F, Cianci R, 2015. How the Intricate Interaction among Toll-Like Receptors, Microbiota, and Intestinal Immunity Can Influence Gastrointestinal Pathology. J. Immunol. Res 2015, 489821. doi: 10.1155/2015/489821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarner F, Malagelada JR, 2003. Gut Flora in Health and Disease. Lancet 361, 512–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeney DD, Gareau MG, Marco ML, 2018. Intestinal Lactobacillus in health and disease, a driver or just along for the ride? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 49, 140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation, Part #15044223, Rev. B, 2013. http://support.illumina.com/documents/documentation/chemistry_documentation/16s/16s-metagenomic-library-prep-guide-15044223-b.pdf. Accessed May 19, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jandhyala SM, Madhulika A, Deepika G, Rao GV, Reddy DN, Subramanyam C, Sasikala M, Talukdar R, 2017. Altered intestinal microbiota in patients with chronic pancreatitis: implications in diabetes and metabolic abnormalities. Sci. Rep 7, 43640. doi: 10.1038/srep43640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson MEV, Holmén Larsson JM, Hansson JC, 2011. The two mucus layers of colon are organized by the MUC2 mucin, whereas the outer layer is a legislator of host–microbial interactions. PNAS. 108, S1:4659–4665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006451107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai C, Sugimoto K, Moritani I, Tanaka J, Oya Y, Inoue H, Tameda M, Shiraki K, Ito M, Takei Y, Takase K, 2015. Comparison of the gut microbiota composition between obese and non-obese individuals in a Japanese population, as analyzed by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism and next-generation sequencing. BMC Gastroenterol. 15, 100. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0330-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish L, Hotte N, Kaplan GG, Vincent R, Tso R, Ganzle M, Rioux KP, Thiesen A, Barkema HW, Wine E, et al. , 2013. Environmental particulate matter induces murine intestinal inflammatory responses and alters the gut microbiome. PLoS One 8, e62220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause G, Winkler L, Mueller SL, Haseloff RF, Piontek J, Blasig IE, 2008. Structure and function of claudins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778, 631–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner A, Jeremias P, Matthias T, 2015. The world incidence and prevalence of autoimmune diseases is increasing. International J. Celiac. Dis 3, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ley RE, Turnbaugh P, Klein S, Gordon JI, 2006. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 444, 1022–1023. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Wang B, Zhang M, Rantalainen M, Wang S, Zhou H, Zhang Y, Shen J, Pang X, Zhang M, et al. , 2008. Symbiotic gut microbes modulate human metabolic phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 2117–2122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712038105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Yang J, Saffari A, Jacobs J, Baek KI, Hough G, Larauche MH, Ma J, Jen N, Moussaoui N, et al. , 2017. Ambient ultrafine particle ingestion altered gut microbiota in association with increased atherogenic lipid metabolites. Sci. Rep 7, 42906. doi: 10.1038/srep42906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Cui J, Yang H, Sun H, Lu R, Gao N, Meng Q, Wu S, Wu J, Aschner M, Chen R, 2019a. Colonic injuries induced by inhalational exposure to particulate-matter air pollution. Adv Sci (Weinh). 6, 1900180. doi: 10.1002/advs.201900180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Sun H, Li B, Zhang X, Cui J, Yun J, Yang Y, Zhang L, Meng Q, Wu S, Duan J, Yang H, Wu J, Sun Z, Zou Y, Chen R, 2019b. Probiotics ameliorate colon epithelial injury induced by ambient ultrafine particles exposure. Adv Sci (Weinh). 6, 1900972. doi: 10.1002/advs.201900972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozupone C, Knight R, 2005. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 71, 8228–8235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Ding L, Lu Q, Chen YH, 2013. Claudins in Intestines: Distribution and functional significance in health and disease. Tissue Barriers 1, e24978. doi: 10.4161/tisb.24978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero J, Suwannasual U, Herbert LM, McDonald JD, Lund AK, 2017. The role of the lectin-like oxLDL receptor (LOX-1) in traffic-generated air pollution exposure-mediated alteration of the brain microvasculature in Apolipoprotein (Apo) E knockout mice. Inhal Toxicol. 29, 266–281. doi: 10.1080/08958378.2017.1357774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund AK, Lucero J, Lucas S, Madden M, McDonald J, Campen MJ, 2009. Vehicular emissions induce vascular MMP-9 expression and activity associated with endothelin-1 mediated pathways. Arterioscler. Throm. Vasc. Biol 29, 511–517. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.176107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund AK, Lucero J, Harman M, Madden MC, McDonald JD, Seagrave JC, Campen MJ, 2011. The oxidized low density lipoprotein receptor mediates vascular effects of inhaled vehicle emissions. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 184, 82–89. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201012-1967OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauderly JL, Barrett EG, Day KC, Gigliotti AP, McDonald JD, Harrod KS, Lund AK, Reed MD, Seagrave JC, Campen MJ, Seilkop SK, 2014. The National Environmental Respiratory Center (NERC) experiment in multi-pollutant air quality health research: II. Comparison of responses to diesel and gasoline engine exhausts, hardwood smoke and simulated downwind coal emissions. Inhal Toxicol. 26, 651–667. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2014.925523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JD, White RK, Barr EB, Zielinska B, Chow JC, Grosjean E, 2006. Generation and characterization of hardwood smoke inhalation exposure atmospheres. Aerosol Sci. Technol 40:573–84. 10.1080/02786820600724378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Million M, Lagier JC, Yahav D, Paul M, 2013. Gut bacterial microbiota and obesity. Clin. Microbiol. Infect 19, 305–313. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata R, van Eeden SF, 2011. The innate and adaptive immune response induced by alveolar macrophages exposed to ambient particulate matter. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 257, 209–226. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Indias I, Sánchez-Alcoholado L, García-Fuentes E, Cardona F, Queipo-Ortuño MI, Tinahones FJ, 2016. Insulin resistance is associated with specific gut microbiota in appendix samples from morbidly obese patients. Am. J. Transl. Res 8, 5672–5684. doi: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu EA, Comba IY, Cho T, Engen PA, Yazıcı C, Soberanes S, Hamanaka RB, Niğdelioğlu R, Meliton AY, Ghio AJ, Budinger GRS, Mutlu GM, 2018. Inhalational exposure to particulate matter air pollution alters the composition of the gut microbiome. Environ. Pollut 240, 817–830. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.04.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu EA, Engen PA, Soberance S, Urich D, Forsyth CB, Nigdelioglu R, Chiarella SE, Radigan KA, Gonzalez A, Jakate S, et al. , 2011. Particulate matter air pollution causes oxidant-mediated increase in gut permeability in mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol 8, 19. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neish AS, 2009. Microbes in gastrointestinal health and disease. Gastroenterology 136, 65–80. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TL, Vieira-Silva S, Liston A, Raes J, 2015. How Informative Is the Mouse for Human Gut Microbiota Research? Dis. Model Mech 8, 1–16. doi: 10.1242/dmm.017400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nighot P, Al-Sadi R, Rawat M, Guo S, Watterson DM, Ma T, 2015. Matrix metalloproteinase 9-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability contributes to the severity of experimental DSS colitis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 309, G988–997. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00256.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nursat A, Turner JR, Madar JL, 2000. Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of tight junctions. IV. Regulation of tight junctions by extracellular stimuli: nutrients, cytokines, and immune cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 279, G851–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda P, Bobe A, Dolan K, Leone V, Martinez K, 2016. Nutritional modulation of gut microbiota – the impact on metabolic disease pathology. J. Nutr. Biochem 28, 191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim H, Lucero J, Herbert L, Mabondzo A, McDonald JD, Lund AK, 2013. Exposure to vehicular engine emissions results in increased blood brain barrier permeability and altered tight junction protein expression. Part. Fibre Toxicol 10, 62. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-10-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan S, Gilmer JF, Medina C, 2015. Matrix Metalloproteinases in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Update. Mediators Inflamm 2015, 964131. doi: 10.1155/2015/964131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm NW, deZoete MR, Flavell RA, 2015. Immune-microbiota interactions in health and disease. Clin. Immunol 159, 122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer C, Bik EM, DiGiulio DB, Relman DA, Brown PO, 2007. Development of the human infant intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol. 5, e177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Xiao S, Hu M, Zhang X, 2018. Interaction between gut microbiome and cardiovascular disease. Life Sciences. 214, 153–157. 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA 3rd, Bhatnagar A, McCracken JP, Abplanalp W, Conklin DJ, O’Toole T, 2016. Exposure to fine particulate air pollution is associated with endothelial injury and systemic inflammation. Circ. Res 119, 1204–1214. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MD, Campen MJ, Gigliotti AP, Harrod KS, McDonald JD, Seagrave JC, Mauderly JL, Seikop SK, 2006. Health effects of subchronic exposure to environmental levels of hardwood smoke. Inhal. Toxicol 18, 523–539. doi: 10.1080/08958370600685707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva A, Borgo F, Lassandro E, Verduci G, Morace E, Borghi E, Berry D, 2017. Pediatric obesity is associated with an altered gut microbiota and discordant shifts in Firmicutes populations. Environ. Microbiol 19, 95–105. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seilkop SK, Campen MJ, Lund AK, McDonald JD, Mauderly JL, 2012. Identification of chemical components of combustion emissions that affect pro-atherosclerotic vascular responses in mice. Inhal Toxicol 24, 270–287. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2012.667455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, et al. , 2009. Introducing mothur: Open-Source, Platform-Independent, Community-Supported Software for Describing and Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 75, 7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon CE, and Weaver W, 1949. The mathematical theory of communication. University of Illinois Press, Urbana. [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Chang B, 2014. Exploring gut microbes in human health and disease: Pushing the envelope. Genes and Diseases. 1, 132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwannasual U, Lucero J, McDonald JD, Lund AK, 2018. Exposure to traffic-generated air pollutants mediates alterations in brain microvascular integrity in wildtype mice on a high-fat diet. Environ. Res 160, 449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Takada H, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S, 1999. Differential roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in recognition of gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial cell wall components. Immunity 11, 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI, 2006. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444, 1027–1133. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velloso LA, Folli F, Saad MJ, 2015. TLR4 at the crossroads of nutrients, gut microbiota, and metabolic inflammation. Endocr. Rev 36, 245–271. doi: 10.1210/er.2014-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignal C, Pichavant M, Alleman LY, Djouina M, Dingreville F, Perdrix E, Waxin C, Ouali Alami A, Gower-Rousseau C, Desreumaux P, Body-Malapel M, 2017. Effects of urban coarse particles inhalation on oxidative and inflammatory parameters in the mouse lung and colon. Part Fibre Toxicol. 14, 46. doi: 10.1186/s12989-017-0227-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villena J, Kitazawa H, 2013. Modulation of intestinal TLR-4 inflammatory signaling pathways by probiotic microogranisms: Lessons learned from Lactobacillus jensenii TL2937. Front. Immunol 4, 512. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR, 2007. Naïve Bayesian Classifier for Rapid Assignment of rRNA Sequences into the New Bacterial Taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 73, 5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Zhang JJ, Li Z, Gow A, Chung KF, Hu M, Sun Z, Zeng L, Zhu T, Jia G, et al. , 2016. Chronic exposure to air pollution particles increases the risk of obesity and metabolic syndrome: findings from a natural experiment in Beijing. FASEB J. 30, 2115–2122. doi: 10.1096/fj.201500142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward NC, Levine MC, Haghani A, Shirmohammadi F, Saffari A, Sioutas C, Morgan TE, Finch CE, 2017. Toll-like receptor 4 in glial inflammatory responses to air pollution in vitro and in vivo. J. Neuroinflammation 14, 84. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0858-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Ambient Air Pollution Database, 2016. http://www.who.int/phe/health_topics/outdoorair/databases/cities/en/. Accessed October 7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Ambient (outdoor) air quality and health Factsheet, 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs313/en/. Accessed October 7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen YY, Kelbaugh SA, Bewtra M, Knights D, Walters WA, Knight R et al. , 2011. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbioal enterotypes. Science 334, 105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.