Abstract

Prion-like transcellular spreading of tau in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is mediated by tau binding to cell surface heparan sulfate (HS). However, the structural determinants for tau-HS interaction are not well understood. Microarray and SPR assays of structurally-defined HS oligosaccharides show that a rare 3-O-sulfation(3-O-S) of HS significantly enhances tau binding. In Hs3st1−/− (HS 3-O-sulfotransferase-1 knockout) cells, reduced 3-O-S levels of HS diminished both cell surface binding and internalization of tau. In cell culture, the addition of 3-O-S HS 12-mer reduced both tau cell surface binding and cellular uptake. NMR titration mapped 3-O-S binding sites to microtubule binding repeat 2 (R2) and proline-rich region 2 (PRR2) of tau. Tau is only the 7th protein currently known to recognize HS 3-O-sulfation. Our work demonstrates that this rare 3-O-sulfation enhances tau-HS binding and likely the transcellular spread of tau, providing a novel target for disease modifying treatment of AD and other tauopathy.

Keywords: 3-O-sulfation, heparan sulfate, tau, interaction, cellular uptake

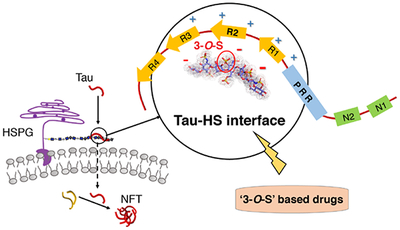

Graphical Abstract

The rare 3-O-sulfation (3-O-S) of heparan sulfate (HS) enhances tau-HS interaction and cellular uptake of tau, suggesting an important role for 3-O-S in the transcellular spread of tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Our work suggests a novel strategy for disease-modifying treatment of AD by targeting the tau-HS interface.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology is characterized by amyloid plaque and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). NFTs are composed of microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT), whose normal functions include bundling and stabilizing microtubules (MTs) in neurons. Continued failure of anti-amyloid compounds in clinical trials has shifted the focus of AD research towards tau. In AD, tau becomes hyperphosphorylated, and dissociates from microtubule and aggregates to form NFTs. In contrast with amyloid plaques, tau pathology correlates well with cognitive decline in AD [1]. Recently, mounting evidence from cell culture [2,3], animal models [4–6] and human pathology [7] has established that tau spread through neural networks in an orderly and ‘prion-like’ manner, mediated by transcellular movement of tau[8–10] (Fig. 1A). Because NFTs directly correlate to cognitive deficits, inhibiting the prion-like spread of tau is likely a viable strategy to slow down cognitive decline and the progression of AD in patients. Thus, there is a pressing need to understand the molecular mechanisms of NFT spread.

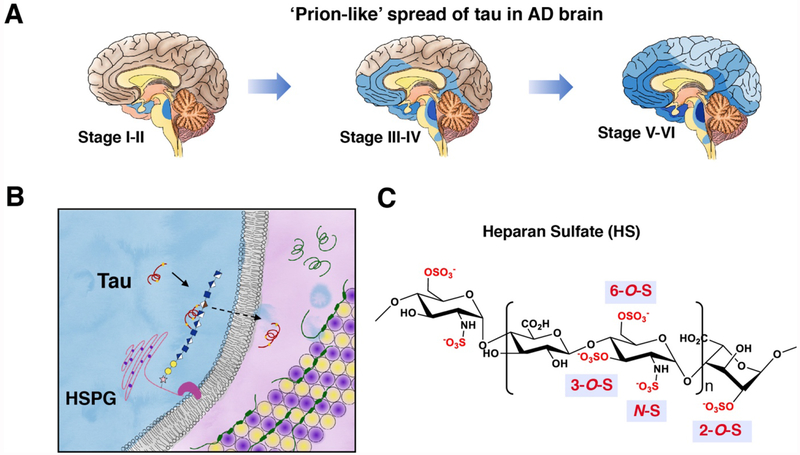

Figure 1. Cellular uptake of tau is mediated by HSPGs on cell surface.

(A) Prion-like spread of tau pathology (represented by blue color) in AD brain. (B) Uptake of tau mediated by the binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). Microtubules are represented by a tube composed of α- and β- tubulins (yellow and purple). (C) Primary structure and sulfation pattern of heparan sulfate.

A key step in tau transcellular movement is tau binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) [11–14] on cell surface (Fig. 1B), followed by the endocytosis of tau. HSPGs are HS glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains covalently linked to a protein core. HS is a linear, polyanionic GAG composed of disaccharide repeats of uronic acid (glucuronic acid or iduronic) and glucosamine with sulfation substitution on the 3-OH, 6-OH and -NH of the glucosamine residue, and the 2-OH of the uronic acid residue (Fig.1C). While electrostatic interaction is the major driving force, in many cases specific sulfation patterns are required for the recognition of HS by its binding partners [15,16]. Sulfation at the 3-O position is relatively rare compared to other modifications, with only six proteins reported to rely on the 3-O-sulfation for binding [17–19]. In human, 3-O-sulfation of HS is catalyzed by seven isoforms of 3-O-sulfotransferase (HS3ST): HS3ST1, 2, 3A, 3B, 4, 5 and 6. Among these isoforms, HS3ST1, 2, and 5 are only expressed in the brain [20], with increased Hs3st2 and Hs3st4 level in AD hippocampus [21]. Importantly, genome-wide genetic association (GWAS) studies have implicated HS3ST1 in AD [22,23]. Moreover, a recent study showed that HS containing GAGs isolated from AD brain exhibit enhanced tau binding, further suggesting the involvement of 3-O-sulfation in AD. However, how 3-O-sulfation contributes to AD remains unclear.

Here, utilizing structurally defined HS oligosaccharide microarray, surface plasmon resonance (SPR), nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR), and cellular binding and uptake assays, we report for the first time that the rare 3-O-S is a crucial determinant in tau-HS interaction and cellular uptake of tau. Our results provide molecular details of the link between 3-O-sulfation of HS and AD, pointing towards novel strategies for tau-targeted AD therapy.

Results

3-O-S enhances tau binding to HS in glycan array analysis.

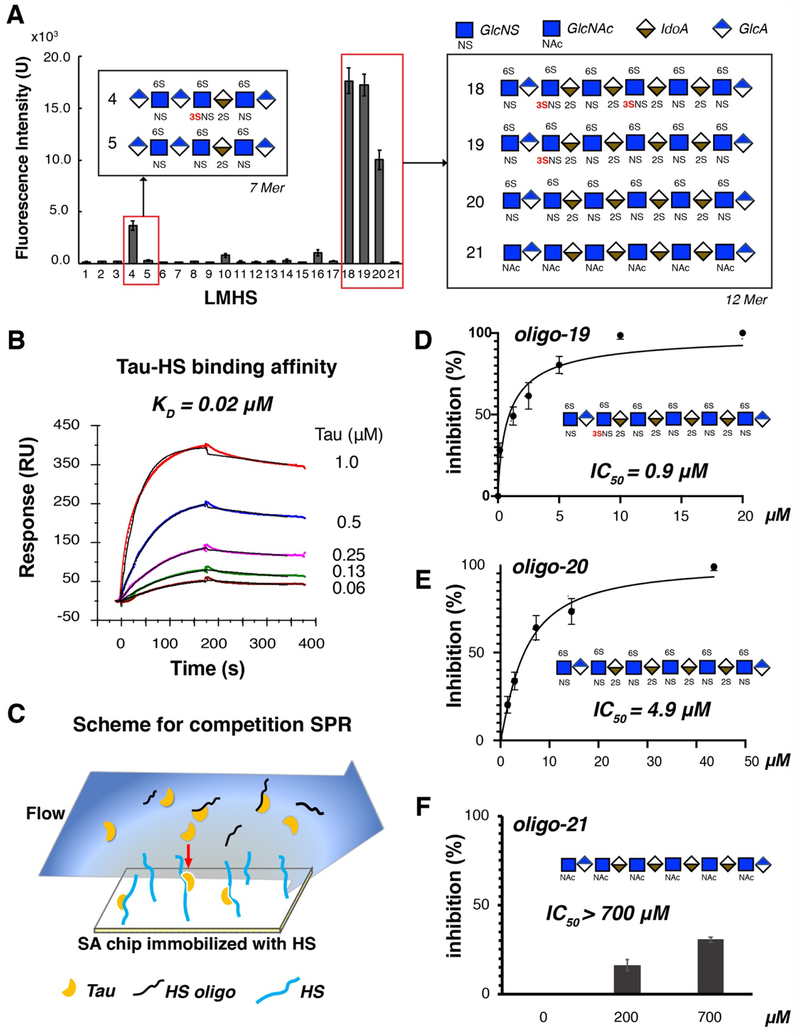

Previous interaction studies of tau/glycan have relied on heparin as a substitute for HS but important structural and functional differences exist between heparin and HS. In this studies, tau/glycan interaction has been examined using HS. Structurally defined HS oligosaccharides were synthesized by a chemoenzymatic method as previously described [18,24] and were then immobilized on a microarray chip, creating the low molecular weight HS (LMHS) array. Full-length tau binding (or lack thereof) to the HS array was visualized by fluorescently-labeled tau remaining on the chip after incubation and washing. As shown in Fig. 2A, high fluorescence intensity was observed for a HS heptasaccharide (7-mer) on spot 4 (oligo-4), and three HS dodecasaccharides (12-mers) in spot 18,19 and 20 (oligo-18, -19 and -20). Remarkably, oligo-4 which only differs from oligo-5 by a single additional 3-O-sulfo group, exhibits ~ 10-fold higher fluorescence intensity than oligo-5, indicating that the presence of 3-O-S increases the binding of tau protein. The significance of 3-O-S is also underscored from the binding of tau to longer oligosaccharides as demonstrated by the microarray analysis. HS 12-mer oligo-18 and oligo-19, containing two and one 3-O-S, respectively, displayed higher binding to tau compared to oligo-20, a HS 12-mer lack of 3-O-S. Oligo-21, which is not sulfated, exhibited negligible fluorescence.

Figure 2. Low molecular weight heparan sulfate (LMHS) array and SPR assays show the crucial role of 3-O-sulfation (3-O-S) in tau binding.

(A) 3-O-S enhances tau binding to HS in LMHS analysis. Fluorescence intensity on each spot of array was shown in a bar graph, with the monosaccharide composition/sulfation pattern drawn for the HS oligosaccharides with high fluorescence intensity (tau binding). Complete results of the LMHS array can be found in Fig. S1 and S2. (B) Binding affinity of full-length tau-HS interaction was measured to be 0.02 μM by SPR binding kinetic assay for the first time. The association and dissociation curve of different tau concentrations were fitted (black line) by a 1:1 Langmuir kinetics model in Bio-evaluation. HS from three sources (porcine brain, porcine spine and porcine intestine) were tested (Fig. S3) and only porcine intestinal HS binding is shown here. (C) Scheme for Competition SPR. (D) Oligo-19 inhibits tau-HS binding with an IC50 of 0.9 μM. (E) Oligo-20 inhibits tau-HS binding with an IC50 of 4.9 μM. (F) Oligo-21 does not inhibits tau-HS binding, with an IC50 higher than 700 μM.

3-O-S promotes inhibition of tau-HS interaction by oligosaccharides as demonstrated by SPR analysis.

Binding kinetics and affinity between HS and tau have not been measured before. Here, HS from three different sources, porcine brain, porcine spine and porcine intestine, were prepared, biotinylated, and immobilized on a SA sensor chip for binding studies using full-length tau. Brain, spinal and intestinal HS exhibited similar binding pattern to tau, with a binding affinity (KD) of 0.02 μM (Fig. 2B and Fig. S3), showing similar behavior in tau interaction of HS from these three different sources. The more accessible porcine intestinal HS was then used to further characterize the role of 3-O-sulfation in tau-HS binding, which likely resembles endogenous HS from brain tissues. Three synthesized HS 12-mers, oligo-19, oligo-20 and oligo-21 (the oligosaccharides in spots 19, 20, and 21 of the LMHS array, for chemical structure see Fig. S1B) were tested by a solution/surface competition SPR assay (Fig. 2C) to examine their ability to inhibit tau-HS interaction. Full-length tau protein was individually pre-mixed with each of three HS 12-mer and then flowed over a chip with surface-immobilized HS. The tau protein binding to 12-mer in solution diminishes its interaction with the HS immobilized on the chip surface (Fig. 2C). With increasing 12-mer solution concentrations, less and less binding to the surface was detected. An IC50 of 0.9 μM and 4.9 μM for the inhibition of tau-HS interaction were obtained for oligo-19 and oligo-20, respectively (Fig. 2D and 2E). Observed lower IC50 value for oligo-19 is consistent with the stronger binding of tau to oligo-19 in HS microarray analysis. This ~ 5-fold lower IC50 indicates oligo-19 is much more effective in the inhibition of the tau-HS interaction. In contrast, oligo-21 showed very little inhibition of tau-HS interaction, with an IC50 higher than 700 μM (Fig. 2F), also consistent with the negligible fluorescence signal for oligo-21 in LMHS array. The significantly lower IC50 of oligo-19 compared with that of oligo-20 and the lack of inhibition by oligo-21 demonstrates that sulfation is required for the ability of HS 12-mer to inhibit the tau-HS binding, and that 3-O-S greatly enhances this inhibition.

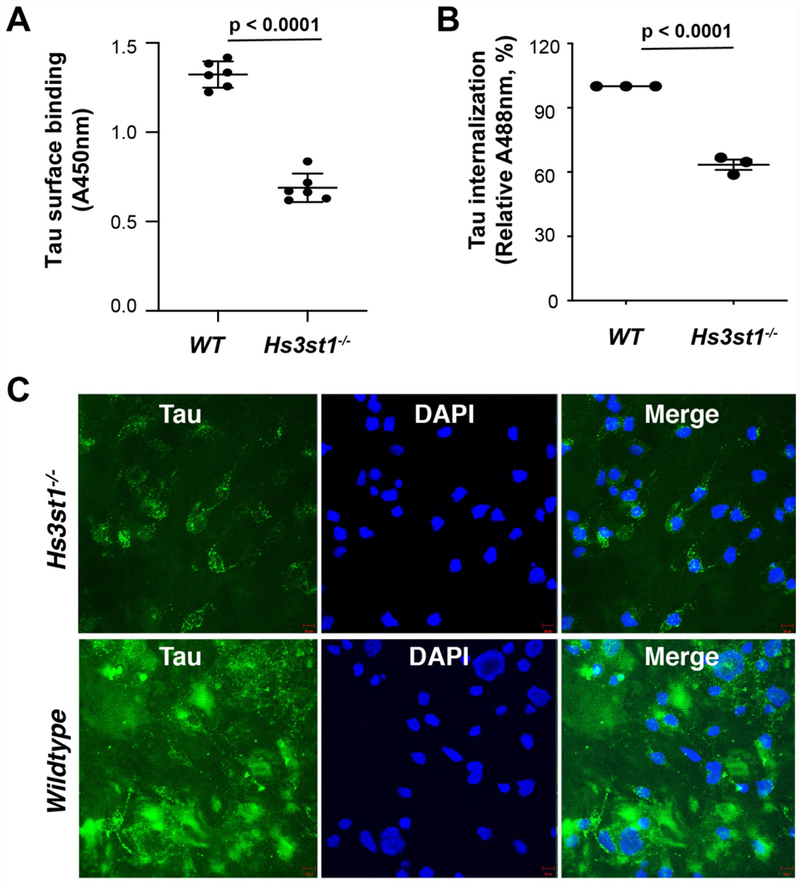

Hs3st knockout reduces tau cell surface binding and cellular uptake.

Based on the microarray and SPR data, we hypothesized that 3-O-S in HSPGs may play an important role in tau binding to the cell surface and its subsequent internalization. To test this hypothesis, we next carried out tau cell surface binding and cellular uptake assays using a pair of wild type (WT) and Hs3st1 knockout (Hs3st1−/−) mouse lung endothelial cell (MLEC) lines. The selection of Hs3st1 was based on the expression profiles of HS 3-O-sulfotransferases in primary mouse cerebral cortex neurons determined by RNA-seq, with the highest expression level observed for Hs3st1 among all Hs3sts (Fig. S4). The Hs3st1−/− MLEC line was derived from the WT parent line using CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing and expressed normal levels of NS, 6-O-S and 2-O-S (Fig. S5A), but reduced level of 3-O-S (confirmed by significantly reduced cell surface binding to antithrombin III requiring a 3-O-S for binding, Fig. S5B)[25]. Biotinylated-tau was generated and incubated with cells, followed by washing and detection of surface-bound tau with streptavidin-HRP. Tau bound strongly to the surface of WT MLECs, while the binding was greatly diminished on Hs3st1−/− MLECs surface, showing that 3-O-S strongly enhances HS binding of tau on the cell surface (Fig. 3A). We next incubated both WT and Hs3st1−/− cells with Alexa488 labeled full-length tau (tau-Alexa) for 12 hrs., followed by detection with both flow cytometry (Fig. 3B) and confocal imagining (Fig. 3C) to further investigate the effects of 3-O-S deletion on the cellular uptake of tau. Large amounts of tau were internalized into the WT MLECs, but internalization was greatly reduced in the Hs3st1−/− MLECs, indicating that 3-O-S indeed enhances HSPG-mediated tau internalization. Here, we demonstrate another role for cell surface 3-O-S in tau pathology, in which it specifically recognizes extracellular tau and mediates efficient cellular uptake.

Figure 3. Deletion of Hs3st1 diminishes tau cell surface binding and internalization.

(A) The Hs3st1−/− cells showed less (46.3% reduction) tau cell surface binding, compared with WT. After fixing and incubating with biotinylated full-length tau (500 ng/ml, 100 μL/well) for 90 min at RT, the cell surface bound tau was measured after incubating with Streptavidin-HRP and color development. (B) The Hs3st1−/− cells showed significantly less internalization of tau-Alexa (500 ng/ml) assessed by flow cytometry. (C) The Hs3st1−/− cells showed significantly less internalization of tau-Alexa by confocal images. The cells in 12-well plate were incubating with tau-Alexa (2 μg/ml, 500 μL/well) at 37°C for 3 h. The data shown are representative of 2-4 independent experiments.

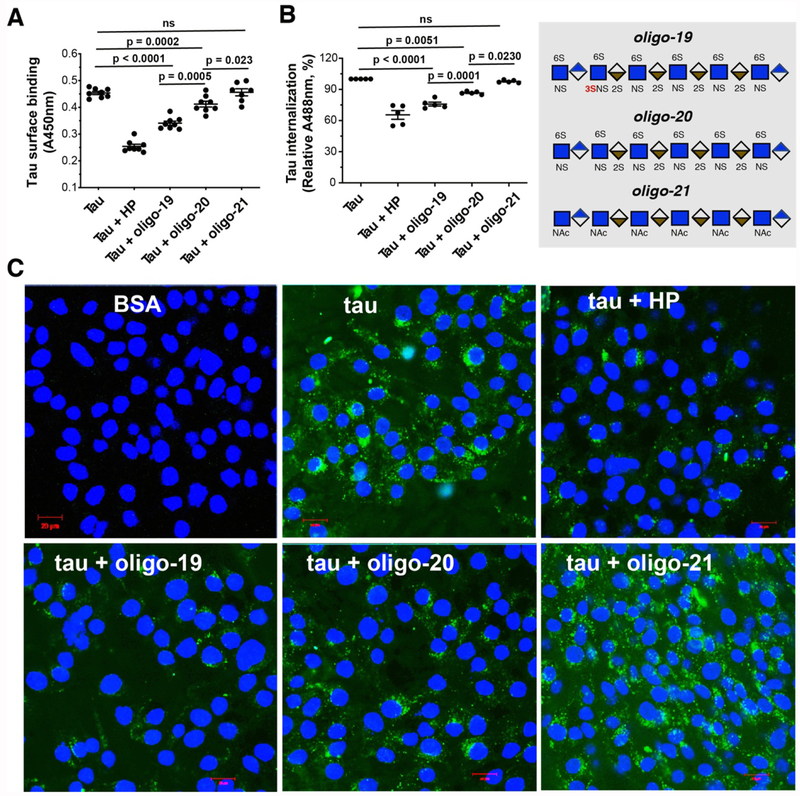

Oligosaccharides with 3-O-S blocks tau cell surface binding and internalization.

Interfering with tau-HS interaction using heparin (HP, a highly sulfated analog of HS) or its mimetics can block tau transcellular spreading in cell culture and animal models [11]. Designing glycan-based compound to disrupt the tau-HS interface represents a novel strategy to develop effective therapeutics for tauopathy in AD. We asked whether 3-O-sulfated oligosaccharides could be more effective at blocking tau cell surface binding and internalization than counterparts without 3-O-S. As expected, HP potently inhibits tau cell surface binding and internalization (Fig. 4). Oligo-19 and oligo-20, but not oligo-21, inhibit tau cell surface binding and internalization with similar pattern as to HP. Compared with oligo-20, oligo-19 exhibits significantly greater inhibition of the cell surface binding and internalization of tau, underscoring the crucial role of 3-O-sulfation for effectively blocking tau-HS interaction on cell surface and tau internalization. The addition of 3-O-S modification may lead to more potent HS-based therapeutics for tauopathy.

Figure 4. 3-O-S modification enhances the inhibitory potency of HS oligo on tau-cell interaction and tau cellular uptake.

(A) HP, oligo-19 and oligo-20 inhibit tau cell surface binding by 46.3%, 28.0% and 13.0%, respectively. After fixing and incubating with biotinylated tau (500 ng/ml, 100 μL/well) without or with HP (50 ng), HS oligos (25 ng) for 90 mins at RT, the cell surface bound tau was measured after incubating with Streptavidin-HRP and color development. Oligo19 has a stronger inhibitory potency than oligo-20. Oligo-21 has no inhibition. (B) HP, oligo-19 and oligo-20 inhibit tau-Alexa (500 ng/ml) internalization assessed by flow cytometry. (C) HP, oligo-19 and oligo-20 inhibit tau internalization assessed by confocal images. The cells were incubated with tau-Alexa (2 μg/ml, 500 μL/well) without or with HP (10 μg/ml), HS oligo (2.5 μg/ml) at 37°C for 3 h. Oligo-19 has a stronger inhibitory potency than olig-20. Olig-21 has no inhibition. The data shown are representative of 2-4 independent experiments.

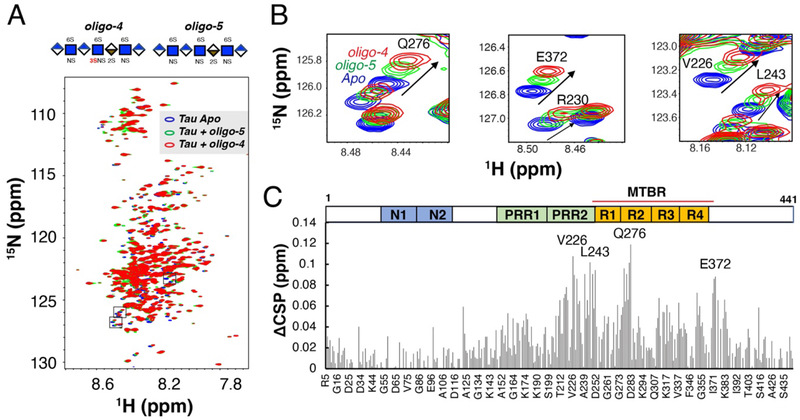

3-O-S is recognized by tau PRR2 and R2 regions in NMR titration.

We next determined which regions of tau are responsible for the recognition of 3-O-S in HS. The primary sequence of the longest tau isoform (441 residues) features the N-terminal projection region (N1 and N2), the proline rich region (PRR1 and PRR2), and the microtubule binding region (MTBR) and the C-terminal region (Fig. 5C). The MTBR includes four internal repeat motifs (R1-R4), which mediates tau interactions with MTs [26,27] and other proteins [28], as well as tau aggregation[3]. We use full-length tau to map the binding sites of 3-O-S. Shorter and more accessible HS oligosaccharides, i.e. oligo-4 (HS 7-mer with 3-O-S) and oligo- 5 (HS 7-mer without 3-O-S), were used in the experiment. Oligo-4 and oligo-5 were individually added to 15N labeled tau and the refocused two-dimensional (2D) 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) NMR spectra of tau were recorded before (blue peaks in Fig. 5A) and after the addition of the HS oligosaccharides (green and red peaks in Fig. 5A). Significant chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) in tau were observed upon addition of both oligo-4 (resonance in red) and oligo-5 (resonance in green) titration (Fig. 5). As expected, oligo-4 caused much larger CSPs than oligo-5, due to the stronger binding conferred by the 3-O-S modification. Several isolated peaks with large CSP are magnified in Fig. 5B. The CSP differences (ΔCSP) between CSP due to oligo-4 and CSP due to oligo-5 were plotted against the residue number (Fig. 5C) to map the binding site of 3-O-S in tau (Fig. 5C). Significant ΔCSPs were located at the PRR2 and R2 domains, in which residues V226, L243, and Q276 exhibit the largest ΔCSPs, indicating the interaction between 3-O-S and the PRR2 and R2 of tau. The hexapeptide 275VQIINK280 in R2, which contributes to tau aggregation and MTs association, was previously identified as the main site of contact with HP [29,30]. PRR regions of tau are not only important for MTs binding [31], but also hot spots for tau phosphorylation [32,33] and protein interactions [34,35]. The recognition of 3-O-S in HS by both PRR2 and R2 suggests HS interaction may modulate both tau aggregation and phosphorylation. The observed CSP are small, partially due to lower binding affinity of the HS 7-mer, and low ratio of HS oligos to tau (0.6) used in NMR mapping experiment. Most ΔCSP comes from a simple increase, not a change in nature of CSP, suggesting 3-O-S enhances existing electrostatic interactions, e.g., between numerous 6-O-sulfo groups of HS and lysine and arginine side chains of tau. The ΔCSP is smaller compared to the magnitude of florescence change in LMHS microarray between oligo-4 and oligo-5. This is most likely due to an intrinsic difference between chip-based binding and pure solution-phase binding, because the local oligo concentration immobilized on the chip may be abnormally high at the chip-solution interface. The association between 7mer and tau is likely in fast exchange on the NMR time scale, based on the lack of line-broadening and small value of CSP observed in NMR titration. A full titration of 3-O-S sulfated oligosaccharides were not carried out due to the limited supply of pure oligo-19 and oligo-20, and the inability of 7-mers to saturate tau binding sites with its lower affinity. Because of the complicated nature of binding between two highly dynamic molecules, more structural studies are needed for the interaction between tau and a high affinity 3-O-sulfated oligosaccharides in the future.

Figure 5. Chemical shift perturbation difference (ΔCSP) reveals specific interactions between 3-O-S and PRR2 and R2 domain of full-length tau.

(A) Overlay of 1H-15N HSQC spectra of full-length tau before (blue) and after 1:0.6 molar ratio addition of HS 7-mer oligo-5 (green) and HS 7-mer oligo-4 (red). (B) Zoomed-in NMR spectra of residues with biggest CSPs. (C) CSP differences (ΔCSP) reveals specific interaction between 3-O-S and tau PRR2 and R2 domain. Construct of tau is shown above the figure, PRR = proline-rich region, MTBR = microtubule binding region.

Discussion

Growing evidence has established that tau propagates in a “prion-like” manner [36,37]. While the mechanisms underlying the trans-cellular spread of tau are not completely understood, a required step in this process is that tau binding to HSPGs on the recipient cell surface[38]. HS interactions with proteins are mainly driven by electrostatic forces, between positively charged side chains on proteins and negatively charged sulfo groups on HS [39]. Although charge-based association is relatively non-specific, many HS-binding proteins require specific sulfation patterns in the glycan, e.g., heparin/antithrombin III (ATIII) interaction requiring a pentasaccharride sequence with a 3-O-sulfo group in its central residue. In contrast to the less stringent requirements for sulfation pattern reported for α-synuclein and Aβ binding to HS [40], tau requires more specific sulfate moieties[13,29,40]. In previous work, we were the first to report that 6-O-S, but not 2-O-S, is required for tau binding, using structurally heterogeneous polysaccharides[29].

Here, we demonstrate that the 3-O-sulfation strongly enhances the tau-HS interaction and cellular uptake of tau, using LMHS microarray, SPR, cellular binding and uptake assays, and NMR. Structurally defined HS 7-mer and 12-mer with additional 3-O-S exhibited significantly stronger binding to tau in LMHS array (Fig. 2). This was then confirmed in SPR competition assays showing that an HS 12-mer with one additional 3-O-S (oligo-19) inhibits tau-HS interaction with ~5-fold lower IC50 value than the same HS 12-mer without 3-O-S (oligo-20) (Fig. 2). The reduced cell surface binding and internalization of tau in Hs3st1−/− cells indicates that 3-O-sulfation significantly enhances the cellular uptake of tau (Fig. 3). These data conclusively demonstrate that 3-O-S modification plays a crucial role in tau-HS interaction and tau cellular uptake. Our data provide a mechanistic rationale for the recent observation that the expression of Hs3st2 and Hs3st4 is elevated in AD brain and that HS containing GAGs isolated from AD brain exhibit enhanced tau binding [21] .

To date, tau is only the seventh protein shown to specifically recognize 3-O-S in HS [41]. Heparin/ATIII interaction has been the prime example of the specific interaction mediated by 3-O-S. Interestingly, 3-O-S also facilitates cellular entry of Herpes simplex virus (HSV-1), which has been linked to AD [42–44]. 3-O-S enhances HS interaction with viral envelope glycoprotein D (gD) [45,46]. Thus, both Herpes virus and tau entry into a cell are enhanced by the 3-O-S functional group, raising the possibility of mechanistic cross-talks between the spread of tau pathology and Herpes infection in the AD brain.

By establishing the critical role of the rare 3-O-S HS modification in tau-HS interaction, we provide one of the most important insights for developing HS-based therapies against the spread of tauopathy: to efficiently inhibit cellular uptake of tau, a 3-O-sulfo group is required. In this work, efficient inhibition of tau-HS interaction has been achieved with a HS 12-mer containing 3-O-S (oligo-19) with an IC50 of 0.9 μM, in a SPR competition assay (Fig. 2D). Significant inhibition of cellular binding and uptake of tau was also observed (Fig. 4) by the same oligo-19. Based on these data, we propose that the 3-O-S and tau interface represents a novel target for AD disease-modifying therapy to block tau trans-cellular propagation in AD. HS-based therapeutics targeting tau-HS interface face the additional challenge of crossing the brain blood barrier (BBB), due to their high hydrophilicity. Very recently, highly sulfated HS oligosaccharides were reported to penetrate the hippocampal BBB in a murine sepsis model [47]. This suggests that HS oligosaccharides or analogs may be able to target hippocampus in AD, which also has increased BBB permeability. Prodrugs may be another viable approach to enhance BBB permeability penetrance where a more hydrophobic precursor molecule is processed to an active compound after crossing BBB.

As 3-O-sulfotransferases are overexpressed in AD brain [21], inhibiting the expression or activity of 3-O-sulfotransferases may represent another avenue for inhibiting the propagation of NFT pathology. Indiscriminate inhibition of Hs3st may result in significant side effects because 3-O-sulfation is crucial for multiple physiological interactions, such as heparin interaction with antithrombin III (ATIII) in coagulation, and HS interaction with fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) [48] in cell growth and propagation. However, there are seven isoforms of human Hs3st, among which Hs3st2 and Hs3st4 [49,50] are specifically expressed in the brain. In addition, Hs3st2 and Hs3st4 are overexpressed in AD brain [21,51], raising the possibility that they may be specifically targeted to avoid some nonspecific effects. Although reducing 3-O-sulfation level will not completely inhibit tau uptake, a significant delay of the spread of tau pathology and dementia can still have strong impact in patients’ quality of life and have important social and economic benefits. For example, it is estimated that delaying the onset of dementia by only five years can decrease AD prevalence and associated medical costs by a whopping ~40% [52]. ”

NMR mapping shows 3-O-S (Fig. 5C) preferably binds to the PRR2 and R2 domain of full-length tau, which are the crucial regions for aggregation [53], MTs association [31,54], and interaction with heparin [29,55] and other proteins [34,35]. 6-O-S also binds to the R2 domain as previously studied. Taken together, we suspect there may be a synergistic effect between 3-O-S and 6-O-S that enhances the binding of HS to tau. Similarly, in ATIII-heparin interaction both 3-O-S and 6-O-S modification are critical for inducing the conformational change in ATIII [56] needed for anticoagulant activity of heparin. Unlike ATIII, tau is an IDP without a fixed 3D structure, rendering it a more challenging system for conventional structural characterization. More work is needed to delineate the specific HS motifs (the combination of chain length, monosaccharide composition and precise sulfation pattern) required for tight binding to tau in human brain and in Alzheimer’s disease, and to understand the structural basis of the specific interactions between 3-O-S and tau residues at atomic resolution.

In the brain, tau uptake is complicated and its mechanism depends on cell type. For example, a therapeutic tau-antibodies promoted tau uptake in microglial cells while blocking uptake in neurons [57]. In addition to HSPG mediated micropinocytosis, the propagation of tau pathology likely involves other mechanisms such as exosome fusion [58], receptor-mediated endocytosis [59], phagocytosis [60] and nanotubes [61]. More studies in CNS cell types such as neurons and glial cells are needed to further establish the role of 3-O-S in tau uptake in AD.

Conclusion

In summary, our results demonstrate the key role of 3-O-S in the tau-HS interaction and cellular uptake of tau, uncovering a unique structural requirement of HS recognition by tau. This work represents a major step forward in our understanding of the mechanism of tau-HS interaction, with important implications for 3-O-S as a pharmacophore targeting the spread of tau pathology in the development of effective AD therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by NIH (5R01HL093339, R56AG062344 and U01CA225784 to L.W.).

References

- [1].Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT, Neurology 1992, 42, 631–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wu JW, Herman M, Liu L, Simoes S, Acker CM, Figueroa H, Steinberg JI, Margittai M, Kayed R, Zurzolo C, et al. , J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288, 1856–1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Frost B, Jacks RL, Diamond MI, J. Biol. Chem 2009, 284, 12845–12852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Liu L, Drouet V, Wu JW, Witter MP, Small SA, Clelland C, Duff K, PLoS One 2012, 7, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].De Calignon A, Polydoro M, Suárez-Calvet M, William C, Adamowicz DH, Kopeikina KJ, Pitstick R, Sahara N, Ashe KH, Carlson GA, et al. , Neuron 2012, 73, 685–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Clavaguera F, Bolmont T, Crowther RA, Abramowski D, Frank S, Probst A, Fraser G, Stalder AK, Beibel M, Staufenbiel M, et al. , Nat. Cell Biol 2009, 11, 909–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cope TE, Rittman T, Borchert RJ, Jones PS, Vatansever D, Allinson K, Passamonti L, Vazquez Rodriguez P, Bevan-Jones WR, O’Brien JT, et al. , Brain 2018, 141, 550–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brettschneider J, Del Tredici K, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ, C 2015, 16, 109–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Goedert M, Masuda-Suzukake M, Falcon B, Brain 2017, 140, 266–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Guo JL, Lee VMY, Nat. Med 2014, 20, 130–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Holmes BB, DeVos SL, Kfoury N, Li M, Jacks R, Yanamandra K, Ouidja MO, Brodsky FM, Marasa J, Bagchi DP, et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2013, 110, E3138–E3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Holmes BB, Furman JL, Mahan TE, Yamasaki TR, Mirbaha H, Eades WC, Belaygorod L, Cairns NJ, Holtzman DM, Diamond MI, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2014, 111, E4376–E4385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rauch JN, Chen JJ, Sorum AW, Miller GM, Sharf T, See SK, Hsieh-Wilson LC, Kampmann M, Kosik KS, Sci. Rep 2018, 8, DOI 10.1038/s41598-018-24904-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stopschinski BE, Holmes BB, Miller GM, Manon VA, Vaquer-Alicea J, Prueitt WL, Hsieh-Wilson LC, Diamond MI, J. Biol. Chem 2018, 293, 10826–10840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gama CI, Tully SE, Sotogaku N, Clark PM, Rawat M, Vaidehi N, Goddard WA, Nishi A, Hsieh-Wilson LC, Nat. Chem. Biol 2006, 2, 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Soares da Costa D, Reis RL, Pashkuleva I, Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 2017, 19, 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Thacker BE, Seamen E, Lawrence R, Parker MW, Xu Y, Liu J, Vander Kooi CW, Esko JD, ACS Chem. Biol 2016, 11, 971–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wang Z, Hsieh PH, Xu Y, Thieker D, Chai EJE, Xie S, Cooley B, Woods RJ, Chi L, Liu J, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 5249–5256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Alavi Naini SM, Soussi-Yanicostas N, Front. Cell Dev. Biol 2018, 6, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, et al. , Science (80-. ). 2015, 347, DOI 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Huynh MB, Ouidja MO, Chantepie S, Carpentier G, Maïza A, Zhang G, Vilares J, Raisman-Vozari R, Papy-Garcia D, PLoS One 2019, 14, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Desikan RS, Schork AJ, Wang Y, Thompson WK, Dehghan A, Ridker PM, Chasman DI, Mcevoy LK, Holland D, Chen CH, et al. , Circulation 2015, 131, 2061–2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Witoelar A, Rongve A, Almdahl IS, Ulstein ID, Engvig A, White LR, Selbæk G, Stordal E, Andersen F, Brækhus A, et al. , Sci. Rep 2018, 8, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Xu Y, Chandarajoti K, Zhang X, Pagadala V, Dou W, Hoppensteadt DM, Sparkenbaugh EM, Cooley B, Daily S, Key NS, et al. , 2017, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [25].Qiu H, Shi S, Yue J, Xin M, Nairn AV, Lin L, Liu X, Li G, Archer-Hartmann SA, Dela Rosa M, et al. , Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 889–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gustke N, Trinczek B, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E, Biochemistry 1994, 33, 9511–9522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Butner KA, Kirschner MW, J. Cell Biol 1991, 115, 717–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mandelkow EME, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 2011, 3, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhao J, Huvent I, Lippens G, Eliezer D, Zhang A, Li Q, Tessier P, Linhardt RJ, Zhang F, Wang C, Biophys. J 2017, 112, 921–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Smet C, Leroy A, Sillen A, Wieruszeski JM, Landrieu I, Lippens G, ChemBioChem 2004, 5, 1639–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Goode BL, Denis PE, Panda D, Radeke MJ, Miller HP, Wilson L, Feinstein SC, Mol. Biol. Cell 1997, 8, 353–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bielska AA, Zondlo NJ, Biochemistry 2006, 45, 5527–5537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Alavi Naini SM, Soussi-Yanicostas N, Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev 2015, 2015, DOI 10.1155/2015/151979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].He HJ, Wang XS, Pan R, Wang DL, Liu MN, He RQ, BMC Cell Biol. 2009, 10, DOI 10.1186/1471-2121-10-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lasorsa A, Malki I, Cantrelle FX, Merzougui H, Boll E, Lambert JC, Landrieu I, Front. Mol. Neurosci 2018, 11, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Goedert M, Science (80-. ). 2015, 349, 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mudher A, Colin M, Dujardin S, Medina M, Dewachter I, Alavi Naini SM, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E, Buée L, Goedert M, et al. , Acta Neuropathol. Commun 2017, 5, 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Holmes BB, DeVos SL, Kfoury N, Li M, Jacks R, Yanamandra K, Ouidja MO, Brodsky FM, Marasa J, Bagchi DP, et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110, E3138–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Capila I, Linhardt RJ, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2002, 41, 390–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Stopschinski BE, Holmes BB, Miller GM, Manon VA, Vaquer-Alicea J, Prueitt WL, Hsieh-Wilson LC, Diamond MI, J Biol Chem 2018, 293, 10826–10840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Thacker BE, Xu D, Lawrence R, Esko JD, Matrix Biol. 2014, 35, 60–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Carbone I, Lazzarotto T, Ianni M, Porcellini E, Forti P, Masliah E, Gabrielli L, Licastro F, Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, 122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Itzhaki RF, Lin WR, Shang D, Wilcock GK, Faragher B, Jamieson GA, Lancet 1997, 349, 241–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Devanand DP, Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep 2018, 18, DOI 10.1007/s11910-018-0863-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Shukla D, Liu J, Blaiklock P, Shworak NW, Bai X, Esko JD, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Rosenberg RD, Spear PG, Cell 1999, 99, 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tiwari V, Clement C, Xu D, Valyi-Nagy T, Yue BYJT, Liu J, Shukla D, Virol J. 2006, 80, 8970–8980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Zhang J, Xia K, Linhardt RJ, Liu J, PNAS 2019, 116, 9208–9213.31010931 [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ye S, Luo Y, Lu W, Jones RB, Linhardt RJ, Capila I, Toida T, Kan M, Pelletier H, Mckeehan WL, Biochemistry 2001, 40, 14429–14439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lawrence R, Yabe T, HajMohammadi S, Rhodes J, McNeely M, Liu J, Lamperti ED, Toselli PA, Lech M, Spear PG, et al. , Matrix Biol. 2007, 26, 442–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mochizuki H, Yoshida K, Shibata Y, Kimata K, J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283, 31237–31245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Sepulveda-Diaz JE, Alavi Naini SM, Huynh MB, Ouidja MO, Yanicostas C, Chantepie S, Villares J, Lamari F, Jospin E, Van Kuppevelt TH, et al. , Brain 2015, 138, 1339–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zissimopoulos J, Crimmins E, clair P St., Forum Heal. Econ. Policy 2015, 18, 25–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sibille N, Huvent I, Fauquant C, Verdegem D, Amniai L, Leroy A, Wieruszeski JM, Lippens G, Landrieu I, Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma 2012, DOI 10.1002/prot.23210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Mandelkow EM, Biernat J, Drewes G, Gustke N, Trinczek B, Mandelkow E, Neurobiol. Aging 1995, 16, 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Sibille N, Sillen A, Leroy A, Wieruszeski JM, Mulloy B, Landrieu I, Lippens G, Biochemistry 2006, 45, 12560–12572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Atha DH, Lormeau JC, Petitou M, Choay J, Rosenberg RD, Biochemistry 1987, 26, 6454–6461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Funk KE, Mirbaha H, Jiang H, Holtzman DM, Diamond MI, J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290, 21652–21662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Wang Y, Balaji V, Kaniyappan S, Krüger L, Irsen S, Tepper K, Chandupatla R, Maetzler W, Schneider A, Mandelkow E, Mol. Neurodegener 2017, 12, 1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Gómez-ramos A, Díaz-hernández M, Rubio A, Díaz-hernández JI, Miras-portugal MT, Avila J, Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol 2009, 19, 708–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Perea JR, Llorens-martín M, Ávila J, Bolós M, Sergeant N, 2018, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Chen D, Drombosky KW, Hou Z, Sari L, Kashmer OM, Ryder BD, Perez VA, Woodard DNR, Lin MM, Diamond MI, et al. , Nat. Commun 2019, 10, DOI 10.1038/s41467-019-10355-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.