Abstract

Objectives.

US states have begun to legalize marijuana for recreational use. In the absence of clear scientific evidence regarding the likely public health consequences of legalization, it is important to understand how the risks and benefits of this policy are being discussed in the national dialogue. To assess the public discourse on recreational marijuana policy, we assessed the volume and content of US news media coverage of the topic.

Method.

We analyzed the content of a 20% random sample of news stories published/aired in high circulation/viewership print, television, and Internet news sources from 2010 to 2014 (N = 610).

Results.

News media coverage of recreational marijuana policy was heavily concentrated in news outlets from the four states (AK, CO, OR, WA) and DC that legalized marijuana for recreational use during the study period. Overall, 53% of news stories mentioned pro-legalization arguments and 47% mentioned anti-legalization arguments. The most frequent pro-legalization arguments posited that legalization would reduce criminal justice involvement/costs (20% of news stories) and increase tax revenue (19%). Anti-legalization arguments centered on adverse public health consequences, such as detriments to youth health and well-being (22%) and marijuana-impaired driving (6%). Some evidence-informed public health regulatory options, like marketing and packaging restrictions, were mentioned in 5% of news stories or fewer.

Conclusion.

As additional states continue to debate legalization of marijuana for recreational use, it is critical for the public health community to develop communication strategies that accurately convey the rapidly evolving research evidence regarding recreational marijuana policy.

1. Introduction

The marijuana policy landscape in the United States (US) is rapidly evolving. Marijuana is the most frequently used controlled substance in the US, with over half of Americans reporting lifetime use (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). While still illegal under federal law, as of 2016 20 states have passed laws ending or reducing criminal penalties for possession of small amounts of marijuana (NORML, 2016), 23 states and the District of Columbia (DC) have legalized marijuana for medical use (Wilkinson et al., 2016), and four states (AK, CO, OR, WA) and DC have legalized marijuana for recreational use by adults aged 21 or older. With the exception of the DC policy, which only allows home cultivation and private consumption of small amounts of marijuana, recreational marijuana legalization at the state level involves the development of regulated retail markets (Saloner et al., 2015). The US Department of Justice has stated that it is unlikely to enforce federal marijuana laws in states with legal markets, so long as states implement regulations that achieve several goals, including preventing marijuana distribution to youth, avoiding marijuana-impaired driving, and preventing violence related to marijuana cultivation and sales (Cole, 2013).

These shifts in marijuana laws signal a major change in US drug control policy. Marijuana has been illegal under federal law since the late 1930s and, like other controlled substances in the US, has long been portrayed negatively through purported ties to violence and racial/ethnic stereotypes (Kleinman, 1992; Kilmer et al., 2012). Changes in the marijuana policy landscape correspond with shifts in public attitudes: in 1969, only 12% of American adults thought marijuana should be made legal; by 2015, that percentage had risen to 53% overall and 68% among millennials (ages 18–34 at time of poll) (Pew Research Center, 2015). While support for legalization has increased across the political spectrum, more Democrats (59%) and Independents (58%) than Republicans (39%) favored legalizing marijuana in 2015 (Pew Research Center, 2015).

The advent of recreational marijuana legalization in the US presents multiple challenges for the public health field. The best available research, which is limited, suggests that key public health concerns of legal recreational marijuana relate to its effects on youth health and educational attainment, cannabis use disorder, and marijuana-impaired driving (Wilkinson et al., 2016). Regulation and enforcement could prevent or mitigate these adverse public health outcomes (Saloner et al., 2015; Pacula et al., 2014; Ammerman et al., 2015), but states are faced with uncertainty regarding whether and how regulatory options can be used to achieve public health goals.

Some key interest groups – such as the American Academy of Pediatrics – have come out in opposition to legalization due to concerns about potential adverse effects on the public’s health (Ammerman et al., 2015). Other actors, such as the American Public Health Association (APHA), have recommended strict regulatory action in states that legalize marijuana for recreational use (American Public Health Association, 2014). Stakeholders from outside the public health realm, such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), support legalization due to the policy’s potential to reduce arrest and incarceration rates, especially among minorities, for non-violent drug offenses (American Civil Liberties Union, 2016). In the face of state budget shortfalls, the potential for new tax revenue generated by commercial recreational marijuana markets is appealing to many policymakers (Fairchild, 2013).

One important source of information about the potential risks and benefits of recreational marijuana legalization is the news media, where the majority of Americans get their information about public health issues (Brodie et al., 2003). News media coverage both reflects and influences the national dialogue about policy issues. The news media reflects public dialogue by reporting on current policy debates and using the actors involved in those debates as sources for news stories (Graber & Dunaway, 2014). Broadly speaking, the news media can influence public knowledge and attitudes in two main ways: agenda-setting (which issues the news media covers) and message framing (which aspects of issues the news media emphasizes) (Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007). One common framing mechanism is to emphasize different potential consequences of public policy. For example, in the case of recreational marijuana, increased tax revenue versus detrimental effects on youth health (Graber & Dunaway, 2014; Gollust et al., 2013; Niederdeppe et al., 2013). News media agenda-setting can influence which issues audiences deem important and require a policy response, and message framing can influence readers/viewers’ attributions of responsibility for causing and solving problems, as well as their support for specific policy options (Graber & Dunaway, 2014; Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007; Chong & Druckman, 2007a).

Assessing the policy messages and regulatory information included in news stories about recreational marijuana policy could provide important insight into which6 types of messages have had the most traction in the national dialogue on the issue to date, as well as how public health-oriented arguments have competed with other types of arguments, e.g. criminal justice and economic, for audiences’ attention. Prior research has examined news coverage on a variety of marijuana-related issues, including news media framing of the consequences of marijuana use (Hughes et al., 2011), news media framing of marijuana as an illicit drug vs. a medicine (Sznitman & Lewis, 2015), and the relationship between news media coverage of marijuana and adolescent use of the drug (Stryker, 2003).

No extant studies have assessed news media coverage of recreational marijuana policy in the US. In the present study, we fill this gap in the literature by analyzing a large sample of US news stories about recreational marijuana policy published/aired between 2010 and 2014 in high circulation/viewership print, television, and internet news sources. The objectives of this study are to assess the volume of US news media coverage in high circulation/viewership national, regional, and local news sources, including news sources from states that have legalized marijuana for recreational use by adults, and to measure the frequency with which different pro and anti-recreational marijuana legalization arguments and options for regulating marijuana for recreational use are mentioned in news coverage. Given the concentration of legalization efforts in a small number of states, we explored whether the volume and content of news stories differed between local news sources from those states versus national/regional news sources. Prior research suggests that different arguments, by activating values tied to political ideology, can appeal differently to Democrats and Republicans (Gollust et al., 2013; Nordhaus & Schellenberger, 2007; Nisbet, 2009; Haidt, 2012). In the context of differential levels of support for legalizing marijuana for recreational use among Democrats and Republicans, we also explored whether pro- and anti-legalization arguments and discussion of regulatory options differed across Democrat and Republican-affiliated newspapers.

2. Methods

2.1. Study sample

We analyzed news stories about recreational marijuana policy published/aired by 42 high circulation/viewership national, regional, and local news outlets during 2010–2014. Print news sources included: four national newspapers, eight regional newspapers (two from each of the four US census regions – Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), and ten local newspapers (two from each of the four states (AK, CO, OR, WA) and DC where recreational marijuana use was legalized during the study period). Television news sources included: national television news programs aired on ABC, NBC, CBS, PBS, and Fox News and local television news programs aired on the ABC, NBC, and CBS affiliates in four of the five states/districts that legalized recreational marijuana (CO, DC, OR & WA – due to small market size, transcripts for AK were not available). Internet news sources included: the Huffington Post and the Seattle Times and Denver Post blogs. We selected the highest circulation/viewership news sources available in each of these categories. Circulation and viewership statistics were obtained from the Audit Bureau of Circulation and Neilsen (Alliance for Audited Media, 2013; Nielsen, 2015). Print news sources were purposefully selected in order to achieve balance across political affiliation, defined by 2012 Presidential endorsement (Democratic, Republican, no endorsement) (Niederdeppe et al., 2013; McGinty et al., 2014). See Table 1 for a complete list of news sources and their 2012 political endorsements.

Table 1.

News sources included in sampling frame: 2010–2014 (N = 610).

| News outlet (R, D,N) indicates Republican, Democratic, or no endorsement in 2012 presidential election |

News stories focused on marijuana legalization (N) | Recreational marijuana legalization arguments (N, (%)a) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Only pro-arguments | Only anti-arguments | Both pro- and anti-arguments | No argumentsb | ||

| Total | 610 | 146 (24) | 108 (18) | 178 (29) | 178 (29) |

| Print News Outlets | 380 | 92 (24) | 65 (17) | 112 (29) | 111 (29) |

| National Print News Outlets | 62 | 14 (23) | 9 (15) | 21 (34) | 18 (29) |

| New York Post (R) | 3 | 2 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) |

| New York Times (D) | 32 | 5 (16) | 4 (13) | 11 (34) | 12 (38) |

| USA Today (N) | 12 | 6 (50) | 1 (8) | 2 (17) | 3 (25) |

| Wall Street Journal (N) | 15 | 1 (7) | 4 (27) | 8 (53) | 2 (13) |

| Regional Print News Outlets | 45 | 15 (33) | 3 (7) | 20 (44) | 7 (16) |

| New York Daily News (R) | 3 | 2 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) |

| Philadelphia Inquirer (D) | 4 | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Cincinnati Enquirer (R) | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Chicago Tribune (D) | 6 | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) | 2 (33) |

| Dallas Morning News (R) | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Tampa Bay Times (D) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Arizona Republic (R) | 0 | - | - | - | - |

| Los Angeles Times (D) | 29 | 7 (24) | 3 (10) | 15 (52) | 4 (14) |

| Print News Outlets in Legalization Statesc | 273 | 63 (23) | 53 (19) | 71 (26) | 86 (32) |

| Fairbanks Daily News Miner (N) | 11 | 2 (18) | 1 (9) | 5 (45) | 3 (27) |

| Anchorage Daily News (D) | 7 | 1 (14) | 2 (29) | 4 (57) | 0 (0) |

| Colorado Springs Gazette (R) | 39 | 10 (26) | 4 (10) | 6 (15) | 19 (49) |

| Denver Post (D) | 72 | 12 (17) | 13 (18) | 16 (22) | 31 (43) |

| Eugene Register-Guard (D) | 14 | 5 (36) | 4 (29) | 4 (29) | 1 (7) |

| Portland Oregonian (D) | 18 | 6 (33) | 1 (6) | 7 (39) | 4 (22) |

| Spokesman Review (R) | 46 | 10 (22) | 10 (22) | 12 (26) | 14 (30) |

| Seattle Times (D) | 37 | 5 (14) | 11 (30) | 9 (24) | 12 (32) |

| Washington Times (R) | 9 | 4 (44) | 2 (22) | 2 (22) | 1 (11) |

| Washington Post (D) | 20 | 8 (40) | 5 (25) | 6 (30) | 1 (5) |

| Television News Outlets | 142 | 20 (14) | 30 (21) | 51 (36) | 41 (29) |

| National Television News Outletsd | 25 | 4 (16) | 4 (16) | 15 (60) | 2 (8) |

| ABC News (N) | 2 | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) |

| NBC News (N) | 5 | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 6 (86) | 0 (0) |

| CBS News (N) | 3 | 2 (29) | 1 (14) | 3 (43) | 1 (14) |

| PBS News (N) | 6 | 1 (17) | 1 (17) | 3 (50) | 1 (17) |

| Fox News (N) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Television News Outlets in Legalization Statese | 117 | 16 (14) | 26 (22) | 36 (31) | 36 (31) |

| Denver Local Television News Outlets (N) | 44 | 4 (9) | 15 (34) | 9 (20) | 9 (20) |

| Portland Local Television News Outlets (N) | 22 | 4 (18) | 0 (0) | 12 (55) | 12 (55) |

| Seattle Local Television News Outlets (N) | 36 | 8 (22) | 9 (25) | 8 (22) | 8 (22) |

| Washington DC Local Television News Outlets (N) | 33 | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | 7 (47) | 7 (47) |

| Internet News Outlets | 88 | 34 (39) | 13 (15) | 15 (17) | 15 (17) |

| Huffington Post (N) | 56 | 22 (39) | 9 (16) | 12 (21) | 12 (21) |

| Denver Post Blog (D) | 11 | 2 (18) | 3 (27) | 1 (9) | 1 (9) |

| Seattle Times Blog (D) | 21 | 10 (48) | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | 2 (10) |

Percent of news stories within a given news outlet category (row percent).

News stories provided information about marijuana legalization but did not include any arguments for or against legalization.

Local print news outlets in the states (AK, CO, OR, WA) and DC that passed recreational marijuana laws during the study period.

Includes morning and evening news programs on ABC, NBC, and CBS. PBS and Fox do not have morning news programs, therefore only evening programs (PBS News Hour and Fox Special Report) were sampled.

Includes local news affiliates for ABC, NBC, and CBS.

2.2. News coverage selection

News articles and national television transcripts were collected using the LexisNexis and ProQuest databases, and local television news transcripts were collected using ShadowTV online archives. To identify news stories focused on recreational marijuana policy within the 42 selected news sources described above, we used the following search terms: (“marijuana” or “cannabis” or “weed” or “pot”) and (“legal” or “recreation” or “recreational”). We included news stories if the majority of the story described issues related to legalization or regulation of recreational marijuana and excluded news stories not focused on recreational marijuana policy. News stories primarily focused on medical marijuana policy were excluded, though it is possible that included stories mentioned medical marijuana in the context of legalizing marijuana for recreational use. News stories and editorials with 100 or fewer words, letters to the editor, book reviews, and obituaries were excluded. The search returned a total of 14,006 news stories, the complete text of which were then reviewed by the study team, with 3050 stories ultimately meeting inclusion criteria. For the analytic sample, we selected a 20% simple random sample of eligible news stories (N = 610).

2.3. Measures

To assess the content of news stories about recreational marijuana policy, we developed a 56-item structured coding instrument (Appendix A) that measured items in three domains: 1) arguments in favor of recreational marijuana legalization (16 items); 2) arguments against recreational marijuana legalization (14 items); and 3) options for regulating recreational use of marijuana (23 items). We also measured four items that did not fit into these three domains: news media mentions of medical marijuana laws in the context of recreational marijuana laws (e.g. medical marijuana laws as predecessors to recreational marijuana laws), conflicts between state and federal marijuana policy, public opinion regarding recreational marijuana policy, and mention of public health research evidence related to recreational marijuana policy. All measures were dichotomous yes/no items. Two authors (SNB and HS) pilot-tested the instrument on a random sample of 50 news stories, drawn from the same universe of 3050 news stories as the final study sample, and refined it based on pilot study results. A random sample of 100 of the 610 news stories included in the final study sample were double-coded by SNB and HS to assess inter-rater reliability for each item included in the coding instrument. All items met conventional standards for adequate reliability with kappa values of 0.69 or higher (Appendix A) (Landis & Koch, 1977).

2.4. Data analysis

We calculated the proportion of news stories mentioning each measure. We assessed whether the proportion of news stories mentioning each measure differed in local media markets that have enacted recreational marijuana legalization versus national/regional coverage. We also compared whether the content of coverage differed in Democrat-affiliated versus Republican-affiliated news sources. In an additional sensitivity analysis (Appendix B), we assessed whether the proportion of news stories mentioning each measure differed in ‘hard news’ newspaper stories vs. opinion editorials and in newspaper vs. television vs. internet news sources. Statistical comparisons were made using unadjusted logistic regression. Standard errors were clustered by news source in order to account for lack of independence within news sources.

3. Results

3.1. Volume of news media coverage

From 2010 to 2014, the majority of news coverage of recreational marijuana policy appeared in local news outlets located in states that legalized recreational marijuana during the study period. Of the total 380 print news stories included in the sample, 273 were published in local newspapers, compared to 62 national and 45 regional newspaper stories. Similarly, 117 television news stories about recreational marijuana policy were aired on local television news outlets during 2010–2014, compared to 25 stories on national television news (Table 1). Twenty-four percent of news stories (N = 146) mentioned only pro-legalization arguments, 18% (N = 108) mentioned only anti-legalization arguments, 29% (N = 178) mentioned both pro- and anti-legalization arguments in the same story, and 29% (N = 178) did not mention any arguments.

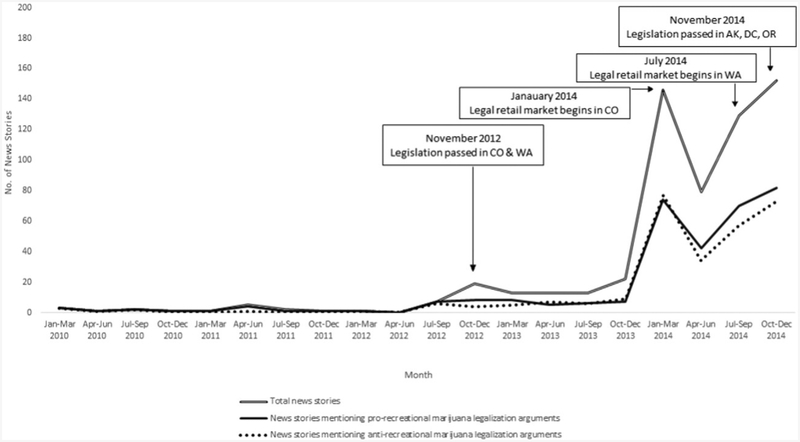

The volume of news media coverage about recreational marijuana policy was heavily concentrated around state legalization efforts (Fig. 1), with the highest spikes in coverage occurring in the first quarter of 2014, when the first recreational marijuana retail market in the US opened for business in Colorado, and in October–December of 2014, when three jurisdictions (AK, DC, and OR) passed laws legalizing recreational marijuana. Compared to the level of news coverage surrounding passage of these three 2014 laws, volume of news coverage about recreational marijuana policy was much lower in October–December of 2012, when the first two states (CO & WA) legalized recreational marijuana.

Fig. 1.

Volume of US news media coverage focused on recreational marijuana legalization overall and by mention of pro- and anti-legalization arguments (N = 610 news stories).

3.2. Pro- and anti-legalization arguments

The five most frequently occurring pro-legalization arguments posited that legalizing marijuana for recreational use by adults would reduce criminal justice system involvement and costs (mentioned in 20% of all news stories); increase tax revenue (19%); reduce the power of criminal drug syndicates (15%); help reverse the failure of current drug policy in the United States (13%); and increase business revenue (11%) (Table 2). The five most common anti-legalization arguments asserted that legalizing recreational marijuana would harm youth (22%); create legal marijuana businesses that attract crime (7%); lead to marijuana impaired driving (6%); lead to a powerful new industry (5%); and fail to eliminate the illegal market (5%).

Table 2.

Number and proportion of news stories including pro- and anti-recreational marijuana legalization arguments, 2010–2014.

| Argument | Total (N=610) N (%) | News source location1 | News source party affiliation2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National & regional news sources (N=188) | Local news sources (N = 422) | Democrat-affiliated news sources (N = 235) | Conservative news sources (N = 102) | ||

| % | % | % | % | % | |

| Any regulatory option | 75 | 68 | 78 | 75 | 87* |

| Any licensing requirement for growers, processors, or retailors | 29 | 23 | 32 | 26 | 40 |

| Limit on the amount of marijuana that can be purchased/possessed at one time | 24 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 37* |

| Limit the amount of marijuana that can be purchased/possessed by out of state residents | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Limit on quantity of home production (e.g. three plants per household) | 10 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 11 |

| Limit on public consumption (e.g. no consumption in public parks) | 10 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 13 |

| Development of a quantitative standard for marijuana-impaired driving | 8 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 11* |

| Change federal rules and regulations so that banks can serve recreational marijuana businesses | 8 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 8 |

| Require labeling of marijuana products | 6 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 11* |

| Require labels that identify product as containing marijuana | 1 | 1 | <1 | 1 | 0 |

| Require labels that describe the health risks of marijuana | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Require labels that do not appeal to children (e.g. no cartoons) | <1 | 0 | 1 | <1 | 1 |

| Limit marijuana marketing (e.g. restrict marketing toward youth) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Any restriction on the location of marijuana retailers | 5 | 1 | 7* | 5 | 10 |

| Regulate location to avoid concentration of marijuana retailers in low-income minority neighborhoods | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Require testing of contents of marijuana products | 4 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| Any limitation on marijuana grow operations | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Any packaging restrictions for marijuana products | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Any recreational marijuana supply chain limitation (e.g. producers cannot also be retailors) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Limit on the potency of marijuana products | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Limit the types of marijuana products sold | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prohibit all edible products | <1 | 1 | <1 | 0 | 0 |

| Prohibit marijuana candy | <1 | 0 | <1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ban home production/cultivation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Logistic regression, with standard errors clustered by news source, was used to make statistical comparisonsbetween news source locations (national/regional vs. local) and by party affiliation (Democrat vs. Republican).

Local news sources were defined as news sources located in states (AK, CO, OR, WA) and DC that legalized recreational marijuana during the study period, 2010–2014.

This analysis was conducted using the subset of print news stories & blogs (N = 337) published by news sources that endorsed a presidential candidate in the 2012 election. Liberal news sources include: New York Times, Philadelphia Inquirer, Chicago Tribune, Tampa Bay Times, Los Angeles Times, Anchorage Daily News, Denver Post, Portland Oregonian, Seattle Times, and Washington Post. Conservative news sources include: New York Post, New York Daily News, Cincinnati Enquirer, Dallas Morning News, Arizona Republic, Colorado Springs Gazette, Spokesman Review, and Washington Times.

News stories appearing in national and regional news sources were more likely than those from local news sources in media markets where these laws were enacted to mention any pro-legalization argument (65% vs. 48%, p < 0.01). The difference in the proportion of Democrat-affiliated (56%) and Republican-affiliated (49%) newspapers mentioning pro-legalization arguments was not statistically significant.

3.3. Regulatory options

Seventy-five percent (N = 456) of news stories mentioned any option for regulating legal recreational marijuana (Table 3). The most frequently mentioned regulatory options were licensing requirements (29%); limits on the amount of marijuana that can be purchased or possessed at one time (24%); limits on the quantity of home-produced marijuana (10%); prohibitions on public consumption (10%); development of standards for marijuana-impaired driving (8%); changes to federal policy to allow banks to serve recreational marijuana businesses (8%); and labeling requirements for marijuana products (6%). All other regulatory options, including limiting marijuana marketing, restricting the location of marijuana retailers, and rules around packaging, potency, and types (e.g. edibles) of marijuana products sold were mentioned in 5% of news stories or fewer. Local and national/regional news sources were equally likely to mention any regulatory option, and Republican-affiliated news sources were more likely than Democrat-affiliated news sources to do so (87% vs. 75%, p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Number and proportion of news stories mentioning recreational marijuana regulatory options, 2010–2014.

| Argument | Total (N=610) N (%) | News source location1 | News source party affiliation2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National & regional news sources (N=188) | Local news sources (N = 422) | Democrat-affiliated news sources (N = 235) | Conservative news sources (N = 102) | ||

| % | % | % | % | % | |

| Any regulatory option | 75 | 68 | 78 | 75 | 87* |

| Any licensing requirement for growers, processors, or retailors | 29 | 23 | 32 | 26 | 40 |

| Limit on the amount of marijuana that can be purchased/possessed at one time | 24 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 37* |

| Limit the amount of marijuana that can be purchased/possessed by out of state residents | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Limit on quantity of home production (e.g. three plants per household) | 10 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 11 |

| Limit on public consumption (e.g. no consumption in public parks) | 10 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 13 |

| Development of a quantitative standard for marijuana-impaired driving | 8 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 11* |

| Change federal rules and regulations so that banks can serve recreational marijuana businesses | 8 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 8 |

| Require labeling of marijuana products | 6 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 11* |

| Require labels that identify product as containing marijuana | 1 | 1 | <1 | 1 | 0 |

| Require labels that describe the health risks of marijuana | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Require labels that do not appeal to children (e.g. no cartoons) | <1 | 0 | 1 | <1 | 1 |

| Limit marijuana marketing (e.g. restrict marketing toward youth) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Any restriction on the location of marijuana retailers | 5 | 1 | 7* | 5 | 10 |

| Regulate location to avoid concentration of marijuana retailers in low-income minority neighborhoods | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Require testing of contents of marijuana products | 4 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| Any limitation on marijuana grow operations | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Any packaging restrictions for marijuana products | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Any recreational marijuana supply chain limitation (e.g. producers cannot also be retailors) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Limit on the potency of marijuana products | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Limit the types of marijuana products sold | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Prohibit all edible products | <1 | 1 | <1 | 0 | 0 |

| Prohibit marijuana candy | <1 | 0 | <1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ban home production/cultivation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

Logistic regression, with standard errors clustered by news source, was used to make statistical comparisonsbetween news source locations (national/regional vs. local) and by party affiliation (Democrat vs. Republican).

Local news sources were defined as news sources located in states (AK, CO, OR, WA) and DC that legalized recreational marijuana during the study period, 2010–2014.

This analysis was conducted using the subset of print news stories & blogs (N = 337) published by news sources that endorsed a presidential candidate in the 2012 election. Liberal news sources include: New York Times, Philadelphia Inquirer, Chicago Tribune, Tampa Bay Times, Los Angeles Times, Anchorage Daily News, Denver Post, Portland Oregonian, Seattle Times, and Washington Post. Conservative news sources include: New York Post, New York Daily News, Cincinnati Enquirer, Dallas Morning News, Arizona Republic, Colorado Springs Gazette, Spokesman Review, and Washington Times.

Overall, 54% of news stories mentioned medical marijuana in the context of recreational marijuana, 35% mentioned conflicts between state and federal marijuana policy, 21% mentioned public opinion on legalization of marijuana for recreational use, and 20% mentioned public health research evidence related to recreational marijuana policy. With the exception of opinion editorials, which were more likely to mention both pro and anti-legalization arguments than ‘hard news’ newspaper stories, there were few differences in news media mentions of pro- and anti-legalization arguments or regulatory options across the categories of news stories and sources compared (Appendix B).

4. Discussion

The public dialogue surrounding recreational marijuana legalization, as measured by news media coverage of the issue, has emerged very recently and been concentrated in states considering and enacting the policy. Pro- and anti-legalization arguments were fairly well balanced across news stories, with a slightly higher proportion mentioning any pro-legalization argument (53%) than any anti-legalization argument (47%). The most frequent anti-legalization arguments focused on the potential negative public health consequences of the policy, namely detrimental effects to youth health, development, and educational attainment. The most frequent pro-legalization arguments centered on potential reductions in criminal justice involvement/costs and increases in tax revenue. The high volume of criminal justice-related arguments suggests that discussion of recreational marijuana legalization is often tied to the broader public dialogue on reforming the US criminal justice system and reducing mass incarceration (Beckett et al., 2016; Takei, 2016; Adelman, 2015). Findings suggest that over the period studied, news audiences were exposed to relatively consistent messaging about recreational marijuana policy, regardless of news source. While the volume of coverage was concentrated in local news sources, the content of local versus national/regional news coverage was largely similar. There were few differences in the content of news stories published in Democrat-affiliated and Republican-affiliated newspapers, which is somewhat surprising given the differential in public opinion on recreational marijuana legalization among these two groups (Pew Research Center, 2015).

Study results suggest that from 2010 to 2014, in the sample of news sources studied the ‘national’ dialogue on recreational marijuana policy was not national at all, but rather centered in a small number of states. The highest volume of coverage came from AK, CO, DC, OR, and WA news outlets. Within the limited national and regional news coverage of the issue, news stories were concentrated in a small number of sources. Of the four national newspapers studied, news stories in the New York Times – which published a high-profile editorial series advocating for recreational marijuana legalization in 2014 (New York Times Editorial Board, 2014) – accounted for over 50% of stories. Among regional newspapers, >80% of coverage came from the Los Angeles Times, likely due to California’s vote against recreational marijuana legalization in 2010 and attempts to put legalization back on the ballot in 2014 (Barbassa, 2010; Sankin, 2013). Two regional newspapers, the Cincinnati Enquirer and the Arizona Republic, had no news stories about recreational marijuana policy during the study period. This finding suggests that large segments of the American public may have relatively little exposure to messages related to marijuana legalization. The lack of widespread diffusion of recreational marijuana policy arguments and information through the news media suggests that the composition of the policy dialogue may shift in coming years, with emergence of new messages or shifts in emphasis on existing arguments as advocacy groups push the consideration of legalization in new states and media markets. Prior communication research has shown that issue framing is dynamic and can evolve considerably over time, particularly for newly emerging policy issues that have not yet been well-defined by prior discourse (Fowler et al., 2011; Nisbet et al., 2003; Chong & Druckman, 2007b). In the case of recreational marijuana legalization, such shifts may occur as early lessons from states that have legalized recreational marijuana are incorporated into the national discussion.

Results suggest that there is an opportunity for the public health community to increase policy communication efforts around evidence-informed regulatory options. Only 20% of news stories mentioned any public health research evidence related to recreational marijuana policy. Prior research has shown that the most frequently mentioned regulation in the news media content studied–licensing of growers, processors, and retailors–is an important option for limiting youth marijuana access, largely because license revocation provides a mechanism for enforcement of prohibition of sales to youth (Saloner et al., 2015; Pacula et al., 2014). However, other evidence-informed regulations designed to restrict youth access (Saloner et al., 2015; Pacula et al., 2014) were rarely mentioned: marketing restrictions, limits on allowable locations of recreational marijuana retailors (e.g. restrictions on locating retailers near schools), product labeling requirements, packaging restrictions (e.g. requirements for childproof packaging), and limitations on the sale of edible products like cookies and candies were mentioned in 6% of news stories or fewer. Despite the fact that it is a major concern and research priority in the public health community (Wilkinson et al., 2016), only eight percent of news stories mentioned the need to develop standards for marijuana-impaired driving.

Our study identified pro- and anti-legalization arguments mentioned most frequently in news coverage of the issue: that recreational marijuana legalization will reduce criminal justice involvement/costs and increase tax revenue, on the one hand, and harm youth health and well-being, on the other. While the most frequent, these arguments are not necessarily the most persuasive. Communication research suggests that argument strength, in addition to volume, plays an important role in influencing public attitudes (Chong & Druckman, 2007a; Chong & Druckman, 2010; Lecheler & de Vreese, 2013). News media use of one-sided versus two-sided arguments about recreational marijuana policy, and the length of those arguments, may also influence public support for such policy (Niederdeppe et al., 2014; Niederdeppe et al., 2012). While outside the scope of the present study, argument strength and composition in news stories about recreational marijuana policy, and their implications for public attitudes, warrant further study.

Study results are subject to several limitations. Our sample included local television news from jurisdictions that legalized recreational marijuana during the study period but not from other, non-legalizing states, and two of the three online news sources were blogs associated with newspapers in states that legalized recreational marijuana. While examination of these sources allowed us to assess television and internet news coverage of the policy in key states, our sample did not include other local television, online, or college/university publications through which Americans access at least some of their news (Pew Research Center, 2014). Further, public attitudes about recreational marijuana use may also be informed by entertainment media, which was outside the scope of this study. It is not clear that excluded news sources would follow the same coverage patterns as we observed in our sample. Comparisons by news source location and party affiliation were exploratory in nature, and multiple comparisons increased the risk that the few differences in news content observed were spurious associations. Study methodology did not allow for assessment of whether or how news media coverage of recreational marijuana legalization was associated with public attitudes about the policy, and our analysis did not permit us to explain trends in news coverage of recreational marijuana policy, which may be driven by competing issues in the news cycle or the changing landscape of news media coverage over time.

5. Conclusion

In the public discourse on legalization of marijuana for recreational use, possible public health risks are weighed against compelling potential benefits of the policy, such as reductions in racial inequalities in criminal justice system involvement (an outcome that is it itself associated, long-term, with multiple public health benefits (Freudenberg & Heller, 2016)). At least 12 additional states are planning ballot measures to legalize recreational marijuana in 2016 (Focus, 2015). As states move forward with considering and enacting laws that legalize recreational marijuana use by adults and create commercial markets, it is critical for the public health community to develop communication strategies that accurately convey the best-available research evidence regarding the public health effects of the policy and associated regulatory strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Ahmad Adi for his help with news story selection.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Supplementary data

Appendix A. Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.06.040.

References

- Adelman L, 2015. Criminal justice reform: the present moment. Wis. L. Rev 181 [Google Scholar]

- Alliance for Audited Media, 2013. Top 25 U.S. Newspapers http://wwwauditedmediacom/news/blog/top-25-us-newspapers-for-march-2013aspx.

- American Civil Liberties Union, 2016. Marijuana Law Reform https://wwwacluorg/issues/criminal-law-reform/drug-law-reform/marijuana-law-reform, accessed February 25, 2016.

- American Public Health Association, 2014. Regulating Commercially Legalized Marijuana as a Public Health Priority http://wwwaphaorg/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2015/01/23/10/17/regulating-commercially-legalized-marijuana-as-a-public-health-priority, accessed February 25, 2016.

- Ammerman S, Ryan S, Adelman WP, 2015. The impact of marijuana policies on youth: clinical, research, and legal update. Pediatrics 135, e769–e785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbassa J, 2010. Proposition 19, Ballot Measure in California that would Legalize Pot, Endorsed by Largest Union in the State http://wwwhuffingtonpostcom/2010/09/21/proposition-19-legalize-pot_n_733826html, accessed February 25, 2016.

- Beckett K, Reosti A, Knaphus E, 2016. The end of an era? Understanding the contradictions of criminal justice reform. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci 664, 238–259. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie M, Hamel EC, Altman DE, Blendon RJ, Benson JM, 2003. Health news and theAmerican public, 1996–2002. J. Health Polit. Policy Law 28, 927–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong D, Druckman JN, 2007a. A theory of framing and opinion formation in competitive elite environments. J. Commun 57, 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Chong D, Druckman JN, 2007b. Framing theory. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci 10, 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Chong D, Druckman JN, 2010. Dynamic public opinion: communication effects over time. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev 104, 663–680. [Google Scholar]

- Cole J, 2013. Memorandum for All United States Attorneys: Guidance Regarding Marijuana Enforcement http://wwwjusticegov/iso/opa/resources/3052013829132756857467pdf?utm_source5publish2&utm_medium5referral&utm_campaign5wwwkpbsorg Accessed February 25, 2016.

- Fairchild C, 2013. Legalizing Marijuana Would Generate Billions in Additional Tax Revenue Annually http://wwwhuffingtonpostcom/2013/04/20/legalizing-marijuana-tax-revenue_n_3102003html, accessed February 25, 2016.

- Focus K, 2015. Marijuana Ballot Measures in Upcoming State Elections http://congressorg/2015/09/10/marijuana-ballot-measures-in-upcoming-state-elections/, accessed March 10, 2016.

- Fowler EF, Gollust SE, Dempsey AF, Lantz PM, Ubel PA, 2011. Issue emergence, evolution of controversy, and implications for competitive framing: the case of the HPV vaccine. Int. J. Press/Polit 1940161211425687. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N, Heller D, 2016. A review of opportunities to improve the health of people involved in the criminal justice system in the United States. Annu. Rev. Public Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollust SE, Niederdeppe J, Barry CL, 2013. Framing the consequences of childhood obesity to increase public support for obesity prevention policy. Am. J. Public Health 103, e96–e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber DA, Dunaway J, 2014. Mass Media and American Politics. CQ Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J, 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion. Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CE, Lancaster K, Spicer B, 2011. How do Australian news media depict illicit drug issues? An analysis of print media reporting across and between illicit drugs, 2003–2008. Int. J. Drug Policy 22, 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer B, Caulkins J, Kleiman M, 2012. Marijuana Legalization: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman MA, 1992. Against Excess: Drug Policy for Results: New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Landis J, Koch G, 1977. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecheler S, de Vreese CH, 2013. What a difference a day makes? The effects of repetitive and competitive news framing over time. Commun. Res 40, 147–175. [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Webster DW, Jarlenski M, Barry CL, 2014. News media framing of serious mental illness and gun violence in the United States, 1997–2012. Am. J. Public Health 104, 406–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York Times Editorial Board, 2014. Repeal Prohibition, Again http://wwwnytimescom/interactive/2014/07/27/opinion/sunday/high-time-marijuana-legalizationhtml, accessed February 25, 2016.

- Niederdeppe J, Kim HK, Lundell H, Fazili F, Frazier B, 2012. Beyond counterarguing: simple elaboration, complex integration, and counterelaboration in response to variations in narrative focus and sidedness. J. Commun 62, 758–777. [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J, Gollust SE, Jarlenski MP, Nathanson AM, Barry CL, 2013. News coverage of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes: pro- and Antitax arguments in public discourse. Am. J. Public Health 103, e92–e98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J, Gollust SE, Barry CL, 2014. Inoculation in competitive framing examining message effects on policy preferences. Public Opin. Q 78, 634–655. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, 2015. Top 10s http://wwwnielsencom/us/en/top10shtml, Accessed March 14,2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet MC, 2009. Communicating climate change: why frames matter for public engagement. Environment 51, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet MC, Brossard D, Kroepsch A, 2003. Framing science the stem cell controversy in an age of press/politics. Int. J. Press/Polit 8, 36–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nordhaus T, Schellenberger M, 2007. Break Through: From the Death of Environmentalism to the Politics of Possibility. Houghton Mifflin, New York. [Google Scholar]

- NORML, 2016. States That Have Decriminalized http://normlorg/aboutmarijuana/item/states-that-have-decriminalized, Accessed march 10, 2016.

- Pacula RL, Kilmer B, Wagenaar AC, Chaloupka FJ, Caulkins JP, 2014. Developing public health regulations for marijuana: lessons from alcohol and tobacco. Am. J. Public Health 104, 1021–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center, 2014. State of the News Media 2014 http://wwwjournalismorg/packages/state-of-the-news-media-2014/, Accessed 7/30/14.

- Pew Research Center, 2015. In Debate Over Legalizing Marijuana, Disagreement Over Drug’s Dangers http://wwwpeople-pressorg/2015/04/14/in-debate-over-legalizing-marijuana-disagreement-over-drugs-dangers/, accessed March 10, 2016.

- Saloner B, McGinty EE, Barry CL, 2015. Policy strategies to reduce youth recreational marijuana use. Pediatrics 135, 955–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankin A, 2013. California Marijuana Legalization Backers Hope to Get Measure Onto 2014 Ballot http://wwwhuffingtonpostcom/2013/02/25/california-marijuana-legalization_n_2760513html, accessed February 25, 2016.

- Scheufele DA, Tewksbury D, 2007. Framing, agenda setting, and priming: the evolution of three media effects models. J. Commun 57, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker JE, 2003. Media and marijuana: a longitudinal analysis of news media effects on adolescents’ marijuana use and related outcomes, 1977–1999. J. Health Commun 8, 305–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. NSDUH Series H-48, HHS Publication No (SMA) 14–4863. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Sznitman SR, Lewis N, 2015. Is cannabis an illicit drug or a medicine? A quantitative framing analysis of Israeli newspaper coverage. Int. J. Drug Policy 26, 446–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei C, 2016. From Mass Incarceration to Mass Control, and Back Again: How Bipartisan Criminal Justice Reform may Lead to a For-Profit Nightmare Available at SSRN. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson ST, Yarnell S, Radhakrishnan R, Ball SA, D’Souza DC, 2016. Marijuana legalization: impact on physicians and public health. Annu. Rev. Med 67, 453–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.