Abstract

STING is an important innate immune protein, but its homeostatic regulation at the resting-state is unknown. Here, we identified TOLLIP as a stabilizer of STING through direct interaction to prevent its degradation. Tollip-deficiency results in reduced resting-state STING protein level in nonhematopoietic cells and tissues and renders STING protein unstable in immune cells, leading to severely dampened STING signaling capacity. The competing degradation mechanism of resting-state STING requires IRE1α and lysosomes. TOLLIP mediates clearance of Huntington’s disease (HD)-linked polyQ protein aggregates. Ectopic expression of polyQ protein in vitro or naturally occurring polyQ proteins in HD mouse striatum sequester TOLLIP away from STING, leading to reduced STING protein and dampened immune signaling. Tollip−/− also ameliorates STING-mediated autoimmune disease in Trex1−/− mice. Together, our findings reveal that resting-state STING protein level is strictly regulated by a constant tug-of-war between ‘stabilizer’ TOLLIP and ‘degrader’ IRE1α-lysosome that together maintains tissue immune homeostasis.

INTRODUCTION

The cGAS-STING pathway is an important innate immune signaling pathway responsible for detecting a variety of microbial pathogens 1. cGAS senses cytosolic DNA and produces a cyclic-dinucleotide, 2’3’-cGAMP, which activates the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized protein STING (encoded by the gene Tmem173). STING activation requires translocation from the ER to ER-Golgi-intermediate compartments (ERGIC), and then to the Golgi 2. During translocation, STING activates IRF3 and NF-κB transcription factors that induce expression of type I interferon (IFN), IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) and inflammatory cytokines.

Constitutive activation of the cGAS-STING pathway leads to autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases 3, of which the best-studied example is Trex1-associated Aicardi-Goutières syndrome (AGS). TREX1, also known as DNase III, is a DNase in the cytoplasm; and Trex1-deficiency causes accumulation of self-DNA that activates cGAS-STING-mediated inflammation and systemic disease in mice 4,5. Autoimmunity in Trex1−/− mice originates from nonhematopoietic cells in the heart and these mice succumb to inflammatory myocarditis around 3 months of age 6,7. Either Tmem173+/− or Tmem173−/− can fully rescue Trex1−/− mouse survival, demonstrating a strong dependence of Trex1−/− disease on STING 6.

Given the essential function of STING, the STING signaling cascade is regulated by multiple checks and balances, most of which act after STING activation, to enhance or limit downstream IFN signaling. For example, post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination play important roles in regulating ligand-mediated STING activation 8–12. However, homeostatic regulation of STING protein at the resting-state is much less understood. Here, we identify TOLLIP as a STING stabilizer at the resting-state that is important for establishing tissue immune homeostasis.

RESULTS

Identification of TOLLIP as a positive regulator of STING-mediated immune response

A CRISPR/Cas9 screen was performed to look for regulators of the STING signaling pathway (data not shown). The original screen was performed using pooled mouse CRISPR/Cas9 gRNA library (GeckoCRISPRv2, Addgene) and wild type mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) expressing a fluorescent reporter as a readout for STING activation. During this pilot screen, we identified several candidates, which we further validated in a secondary screen using individual siRNA knockdown and endogenous Ifnb expression as a readout (Figure 1A). We further selected candidates that specifically regulate the STING pathway. TOLLIP was identified as the top candidate, as pooled siRNA knockdown of Tollip in wild type MEFs potently inhibited the intracellular cGAMP- but not the dsRNA-induced Ifnb expression (Figure 1A, 1B). Other candidates are also of interest and will be pursued in the future.

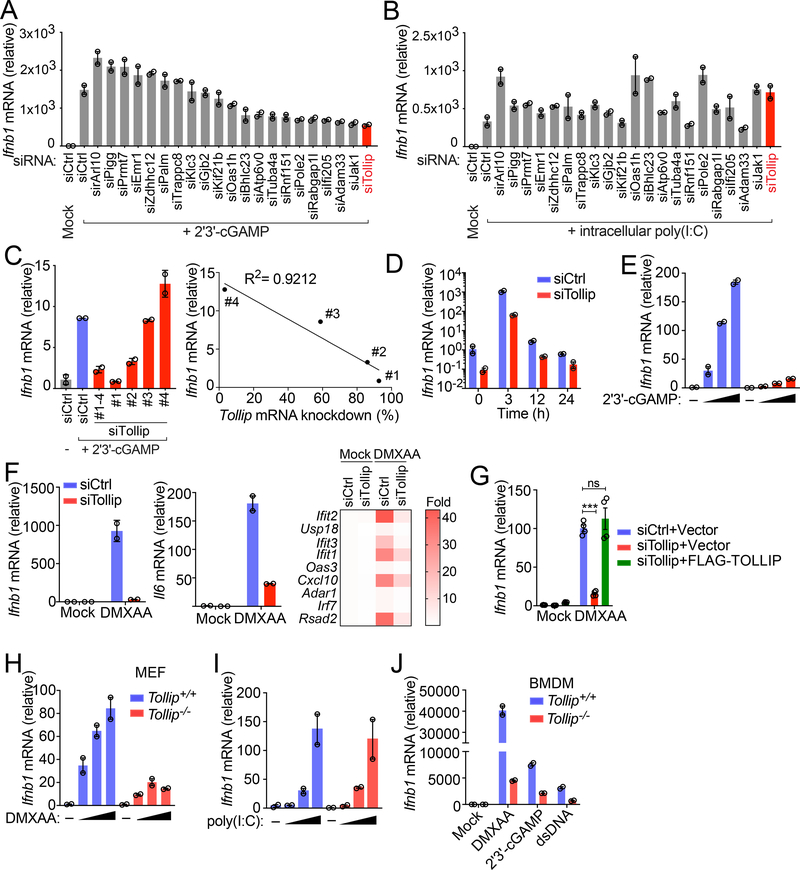

Figure 1: Tollip-deficiency impairs STING-mediated IFN signaling.

(A and B) Arrayed siRNA screen of 21 different gene targets in MEFs. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) expression of Ifnb mRNA following cGAMP stimulation (2 μg/ml, transfected by Lipofectamine, same below) for 5 h (A) or intracellular polyI:C (1 μg/ml, transfected by Lipofectamine, same below) for 5 h (B). A representative experiment with 2 biological replicates is showing (same below). Experiments were repeated for at least three times (same below).

(C) qRT-PCR analysis of Ifnb mRNA following cGAMP stimulation for 5 h. Wild type MEFs were treated with control siRNA (siCtrl) with 4 distinct siRNA sequences targeting Tollip for 48 h before cGAMP stimulation. Right panel shows that cells with greater Tollip KD had less Ifnb mRNA expression.

(D) qRT-PCR analysis of Ifnb mRNA in Tollip KD MEFs stimulated with cGAMP over a 24 h time course.

(E) qRT-PCR analysis of Ifnb mRNA in Tollip KD MEFs stimulated with increasing amount of cGAMP (0, 2, 3, 5 μg/ml) for 5 h.

(F) qRT-PCR analysis of Ifnb, Il6 mRNA and several ISGs in Tollip KD MEFs stimulated with STING agonist DMXAA (50 μg/ml) for 2 h. Heat map summarizes qRT-PCR data on ISG expression.

(G) qRT-PCR analysis of Ifnb in Tollip KD cells stably expressing an empty vector or siRNA-resistant Flag-TOLLIP. Cells were stimulated with DMXAA (50 μg/ml) for 2 h.

(H and I) Tollip+/+ or Tollip−/− MEFs were stimulated with increasing amount of DMXAA (0, 1, 10, 100 μg/ml) for 2 h (H) or intracellular polyI:C (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 5.0, 10.0 ng/ml) for 5 h (I). Ifnb mRNA was analyzed by qRT-PCR

(J) Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) from Tollip+/+ or Tollip−/− mice were stimulated with dsDNA (1 μg/ml), cGAMP (2 μg/ml) or DMXAA (50 μg/ml) and Ifnb mRNA was measured by qRT-PCR. For panel G, ***, p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. Error bars represent the SEM. Unpaired Student’s t test (2-sided).

Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

We next knocked down Tollip with 4 individual siRNA oligos, and we observed a strong correlation between Tollip knockdown efficiency and cGAMP-induced IFN response (Figure 1C). The reduced response to cGAMP was evident throughout a 24 h time-course and under a broad-range of cGAMP concentrations (Figure 1D, 1E). Tollip-knockdown also significantly inhibited type I IFN, inflammatory gene and ISG activation by another cell-permeable STING agonist DMXAA (Figure 1F). This reduced immune gene expression was restored when Tollip-knockdown cells were reconstituted with wild type TOLLIP (siRNA-resistant, Figure 1G), suggesting that TOLLIP is required for STING-mediated signaling. Tollip−/− MEFs also showed reduced response to DMXAA but not to intracellular dsRNA (Figure 1H, 1I). Tollip−/− bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) also showed reduced IFN response to cGAS or STING ligands (Figure 1J). These results collectively suggest that TOLLIP positively regulates the STING-mediated immune response.

TOLLIP maintains resting-state STING protein levels

Activated STING recruits the kinase TBK1 to phosphorylate IRF3, a transcription factor for type I IFN and ISG induction. To pinpoint which step of the STING signaling cascade is affected by TOLLIP, we next analyzed IRF3 phosphorylation and STING signaling kinetics. Tollip-knockdown MEFs showed reduced IRF3 phosphorylation after DMXAA stimulation (Figure 2A), consistent with reduced IFN signaling activation. STING protein is substantially reduced in unstimulated Tollip-knockdown cells compared to control cells (at time 0, Figure 2A), suggesting that TOLLIP is required for stabilizing resting-state STING protein. Tmem173 mRNA levels were the same in control and Tollip-knockdown cells (Figure 2B), suggesting that TOLLIP regulates STING at the post-transcriptional level. As controls, we also analyzed MAVS (involved in RNA sensing) and IRAK1 (involved TLR signaling and interacts with TOLLIP 13) protein levels. Neither protein was altered in Tollip-knockdown cells compared to control cells (Figure 2A). Ligand-mediated STING activation causes STING to translocate from the ER to vesicles where STING is rapidly degraded by lysosomes 14. We observed a similar rate of STING degradation after DMXAA stimulation in Tollip-knockdown compared to control cells (Figure 2A), suggesting that TOLLIP does not alter the kinetics of trafficking-mediated STING degradation.

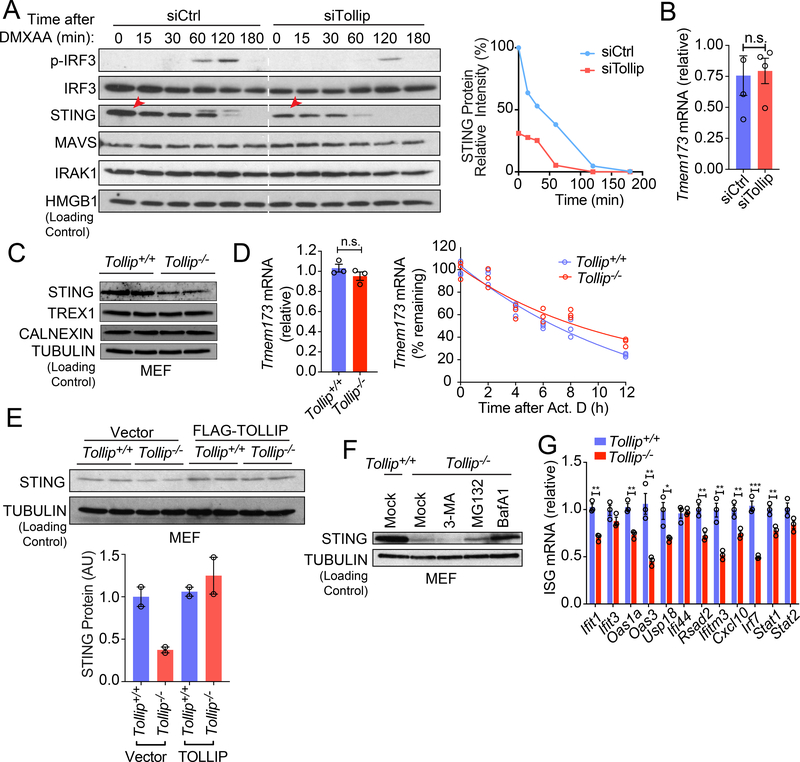

Figure 2: TOLLIP prevents lysosomal-mediated degradation of STING at the resting state.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of control or Tollip-knockdown MEFs stimulated with DMXAA (50 μg/ml) for indicated amount of time (top). Relative intensity of STING protein bands was quantified and presented on the right. Red arrows denote reduced STING protein in Tollip-knockdown cells at time 0.

(B) qRT-PCR analysis of basal Tmem173 mRNA in control or Tollip KD MEfs. n=4 biological replicates.

(C) Immunoblot analysis of STING and other ER proteins in Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− MEFs.

(D) qRT-PCR analysis of Tmem173 mRNA in Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− MEFs. Bar graph shows basal expression level. Line graph shows mRNA turnover after Actinomycin D treatment. n=3 biological replicates.

(E) Immunoblot analysis Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− MEFs stably expressing an empty vector or Flag-TOLLIP. Relative protein band intensity from at least two independent experiments were quantified and presented on the bottom. A representative experiment with 2 biological replicates is showing. Experiments were repeated twice.

(F) Immunoblot analysis of Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− MEFs treated overnight with 3-MA (5 mM), MG-132(5 μM) and BafA1(0.5 μM).

(G) qRT-PCR analysis of basal ISG mRNA in Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− MEFs. n=2 biological replicates.

For panel B, D, G, *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005; n.s., not significant. Error bars represent the SEM. Unpaired Student’s t test (2-sided).

Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

We also analyzed Tollip−/− cells to substantiate the siRNA knockdown findings. Tollip−/− MEFs contain reduced STING protein compared to Tollip+/+ MEFs without affecting Tmem173 mRNA expression or stability (Figure 2C, 2D). Other ER-associated proteins such as TREX1 and CALNEXIN were not affected in Tollip−/− cells, excluding the possibility of a general loss of ER mass in Tollip−/− MEFs (Figure 2C). Stable expression of wild type TOLLIP (using a retroviral vector) in Tollip−/− MEFs restored STING protein amount to that of Tollip+/+ cells (Figure 2E).

We next investigated which protein degradation pathway is responsible for the reduced STING levels in Tollip−/− cells. We treated Tollip−/− cells with inhibitors for autophagosome formation (3-MA), proteasome degradation (MG-132), and lysosome acidification (BafA1). Tollip−/− cells treated with BafA1 completely restored STING protein levels to that of the wild type cells, and MG132 treatment led to a slight increase, suggesting that STING protein is degraded mostly by lysosomes (Figure 2F). We also found that baseline expression of several ISGs are reduced in Tollip−/− MEFs, similar to what has been previously observed with Tmem173−/− MEFs 15,16 (Figure 2G). Together, these data suggest that TOLLIP prevents resting-state STING protein degradation by a lysosome pathway.

TOLLIP interacts with STING

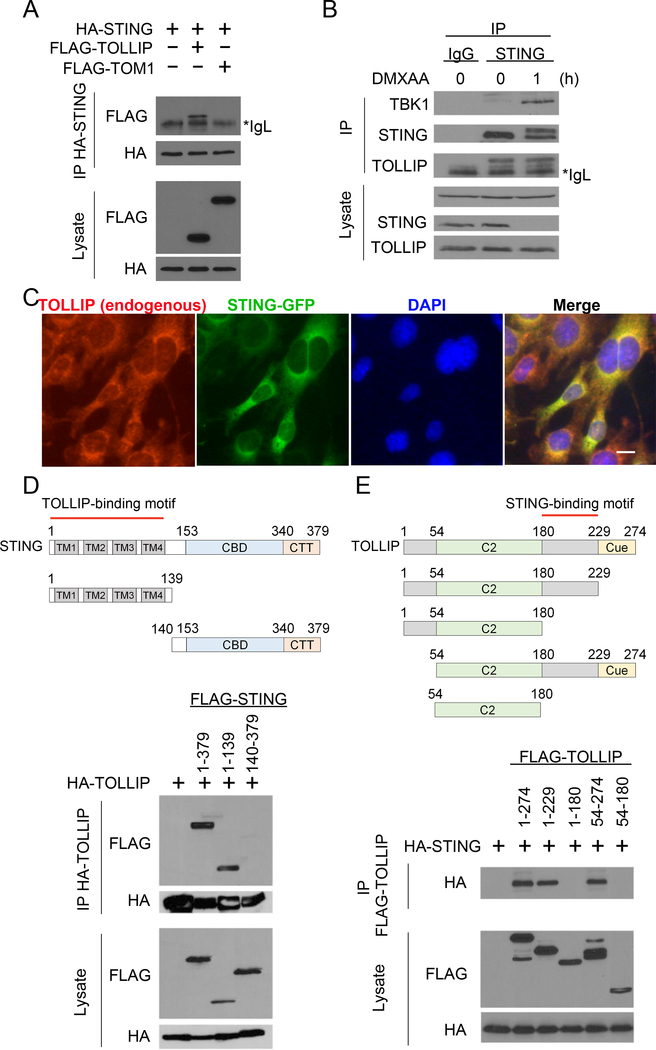

We next explored whether TOLLIP directly interacts with STING and potentially acts as a stabilizer at the resting-state. HA-tagged STING co-immunoprecipitated (co-IP’ed) with FLAG-tagged TOLLIP in HEK293T cells, but not with FLAG-tagged TOM1, a known binding partner of TOLLIP used as a negative control (Figure 3A). Endogenous STING and TOLLIP also co-IP’ed together (Figure 3B). TOLLIP:STING interaction is not dependent on STING activation because we detected a similar amount of TOLLIP co-IP with endogenous STING pull-down before or shortly after DMXAA stimulation (Figure 3B). As a control, TBK1 only interacted with STING after DMXAA stimulation. Fluorescent microscopy also confirmed endogenous TOLLIP and STING-GFP colocalization (Figure 3C). We next performed truncation mapping to determine which domains of TOLLIP and STING are crucial for this interaction. We found that the N-terminal transmembrane domain of STING (1–139), but not the C-terminus, was required for interaction with full-length TOLLIP (Figure 3D). Since TOLLIP does not have any transmembrane domain, it is likely that TOLLIP associates with short loops between the 4 TMs in STING N-terminus that are exposed to the cytosol. We also created TOLLIP truncations and identified a C-terminal motif between the C2 domain and the CUE domain that is required for interaction with STING (Figure 3E). These data suggest that TOLLIP interacts with STING N-terminus and potentially stabilizes STING protein on the ER.

Figure 3: TOLLIP interacts with STING.

(A) Co-immunoprecipitation of STING and TOLLIP in HEK293T cells. HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated plasmids (top), and 24 h later anti-HA antibody was used to pull down HA-STING. FLAG-TOLLIP or FLAG-TOM1 (a negative control) co-IP was analyzed by immunoblot. *IgL indicates IgG light chain.

(B) Co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous STING and TOLLIP in MEFs. Wild type MEFs were untreated or stimulated with DMXAA for 1 h. Anti-STING antibody was used to pull down endogenous STING. Both IP and lysate were blotted for endogenous TBK1, STING and TOLLIP.

(C) Fluorescent microscopy analysis of TOLLIP and STING localization. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(D, E) Domain mapping studies. HEK293T cells were transfected with full-length TOLLIP plus various truncations of STING (D) or full-length STING plus various truncations of TOLLIP (E). co-IP analysis was performed as in A. Diagrams of each constructs used are showing on the top.

Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

PolyQ-rich protein sequesters TOLLIP and promotes STING degradation

TOLLIP functions as a selective autophagy receptor for proteins harboring polyQ-rich domains. Such proteins are associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington’s disease (HD) 17. We wondered what would happen to STING if proteins with polyQ tracts sequester TOLLIP away from STING. We utilized the HUNTINGTIN-polyQ74 (HTTq74) as a model substrate for TOLLIP-mediated degradation as reported before 17. Increasing amounts of TOLLIP led to decreased HTTq74 protein in HEK293T cells, confirming TOLLIP’s known function in clearing polyQ-rich proteins (Figure 4A). We next expressed increasing amounts of HTTq74 in HEK293T cells, and we observed a dose-dependent decrease of STING protein (Figure 4B). We also treated HTTq74-expressing cells with BafA1 or MG132, and we found that STING protein was restored after lysosome inhibitor BafA1 but not proteasome inhibitor MG132 treatment (Figure 4C). These data suggest that HTTq74 accumulation results in STING protein degradation by lysosomes. Moreover, HTTq74 expression also inhibited STING-mediated IFN signaling in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4D).

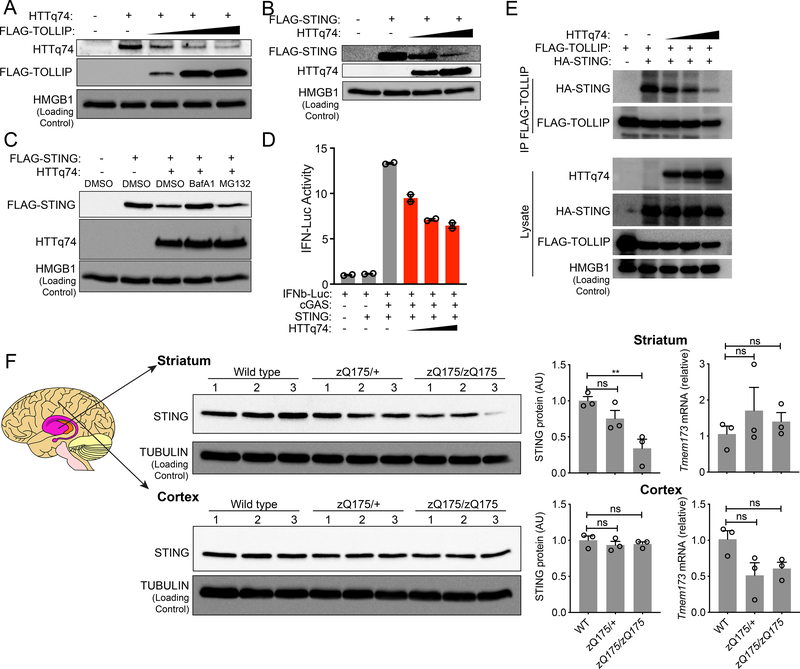

Figure 4: PolyQ protein disrupts TOLLIP:STING interaction and results in STING protein turnover in vitro and in vivo.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of HEK293T cells transfected with the same amount HTTq74 plasmid and increasing amount of FLAG-TOLLIP plasmids (as indicated on top).

(B) Immunoblot analysis of HEK293T cells transfected with the same amount Flag-STING plasmid and increasing amount of HTTq74 plasmids (as indicated on top).

(C) Immunoblot analysis of STING and HTTq74 co-expression treated overnight with MG-132 (5 μM) and BafA1 (0.5 μM).

(D) IFNβ-Luciferase assay of cGAS-STING activation after dose titration of HTTq74 protein. A representative experiment with 2 biological replicates is showing. Experiments were repeated twice.

(E) Co-immunoprecipitation of STING and TOLLIP in HEK293T cells. HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated plasmids (top) in the presence of BafA1 (0.5 μM), and 24 h later anti-FLAG antibody was used to pull down FLAG-TOLLIP. HA-STING co-IP was analyzed by immunoblot. Note, BafA1 was used to prevent STING degradation caused by polyQ protein.

(F) STING protein and mRNA analysis in zQ175 knock-in mouse brain tissues. Wild type, zQ175/+ and zQ175/zQ175 mouse brain striatum and cortex were freshly dissected and processed for immunoblot and qRT-PCR analysis. n=3 mice per group. STING protein blots are showing on the left, densitometry quantitation of STING/TUBULIN band ratio is showing in the middle, and STING mRNA level (normalized to GAPDH) is showing on the right. For panel F, **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant. Error bars represent the SEM. Unpaired Student’s t test (2-sided).

Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

To assess whether HTTq74 protein disrupts the TOLLIP:STING interaction, we expressed increasing amount of HTTq74 in HEK293T cells that are also expressing FLAG-TOLLIP and HA-STING. We also treated cells with BafA1 to avoid STING degradation caused by HTTq74 which would otherwise complicate our interpretation of co-IP data. HTTq74 indeed very potently inhibited STING co-IP with TOLLIP (Figure 4E). Together, these data suggest that polyQ protein sequesters TOLLIP away from STING, which mimics Tollip-deficiency and results in STING degradation by lysosomes.

We next wondered whether naturally-occurring polyQ proteins associated with HD in vivo would also impact STING protein. We chose the zQ175 knock-in mouse that expresses human HTT exon 1 sequence with a ~190 CAG repeat track, and these mice accumulate extensive protein aggregates in the striatum and display neuropathological abnormalities around 4–6 months of age 18. We isolated cortex and striatum tissues from 10-month old wild type, zQ175 heterozygous, and zQ175 homozygous mouse brain and analyzed tissue lysates by immunoblots. We found significantly reduced STING protein in the striatum of zQ175 homozygous mice and a decreasing trend in the heterozygous mice (Figure 4F). STING mRNA level was not affected. Of note, the brain striatum is the main component of the basal ganglia, which is the most affected region of the brain by HD. Taken together, these results suggest that naturally-occurring polyQ protein can lead to reduced STING protein in the striatum in vivo.

TOLLIP specifically stabilizes STING protein in cells

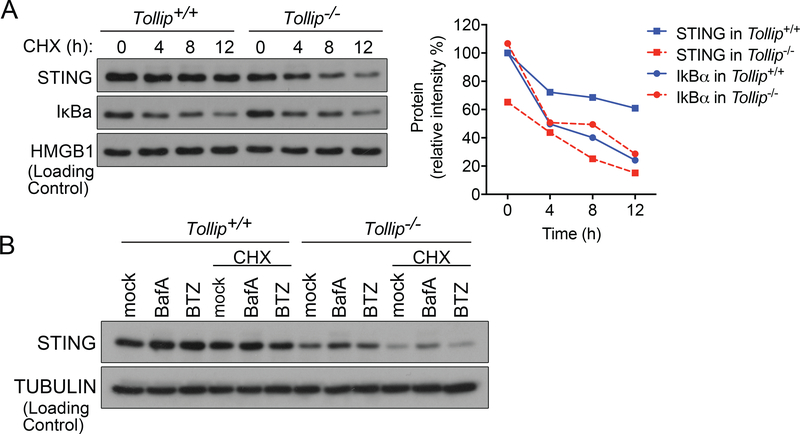

We next determined whether TOLLIP regulates STING protein stability. We treated cells with cycloheximide (CHX), and STING protein became rapidly degraded in Tollip−/− cells with a half-life of approximately 6 h (Figure 5A). In contrast, STING protein is stable in Tollip+/+ cells with a half-life greater than 12 h. As a control, IκBα protein half-life was not altered by Tollip−/−. The rapid degradation of STING after CHX treatment in Tollip−/− cells was prevented by BafA1 treatment (Figure 5B). These data suggest that TOLLIP stabilizes STING protein to prevent lysosome-mediated degradation.

Figure 5: TOLLIP stabilizes STING protein in cells.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of STING protein in Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− MEFs treated with cycloheximide (CHX). IkBa is a control protein with short half-life that is unaffected by TOLLIP. Densitometry quantitation of protein bands are showing on the right.

(B) Immunoblot analysis of STING protein in Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− MEFs treated with cycloheximide (CHX) alone or in combination of proteasome inhibitor BTZ or lysosome inhibitor BafA.

Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

To more rigorously assess whether Tollip−/− causes global protein instability. We performed a chemical pulse-and-chase experiment followed by proteomic analysis comparing Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− MEFs. We first treated cells with Click-iT® AHA (L-azidohomoalaine) for 4 h to label nascently translated proteins. Then, we immunoprecipated AHA-labelled proteins at various times after labeling and analyzed them by quantitative Tandem Mass Tag mass spectrometry (TMT-MS, Supplementary Figure 1A). TMT-MS identified over 1000 proteins with high-confidence in each sample (STING was not detected, likely due to relatively low expression in MEFs). Of the top proteins that show substantial turnover at 20 h, we observed a gradual decrease of protein amounts in both Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− cells that are indistinguishable to each other (Supplementary Figure 1B), validating that our method can indeed detect protein turnover. When we compared the amounts of each protein individually in Tollip+/+ vs Tollip−/− cells, very few proteins either increased or decreased more than 2-fold, and this pattern remains the same throughout the 20 h chase period (Supplementary Figure 1C). Collectively, these data suggest that TOLLIP specifically stabilizes STING protein in cells.

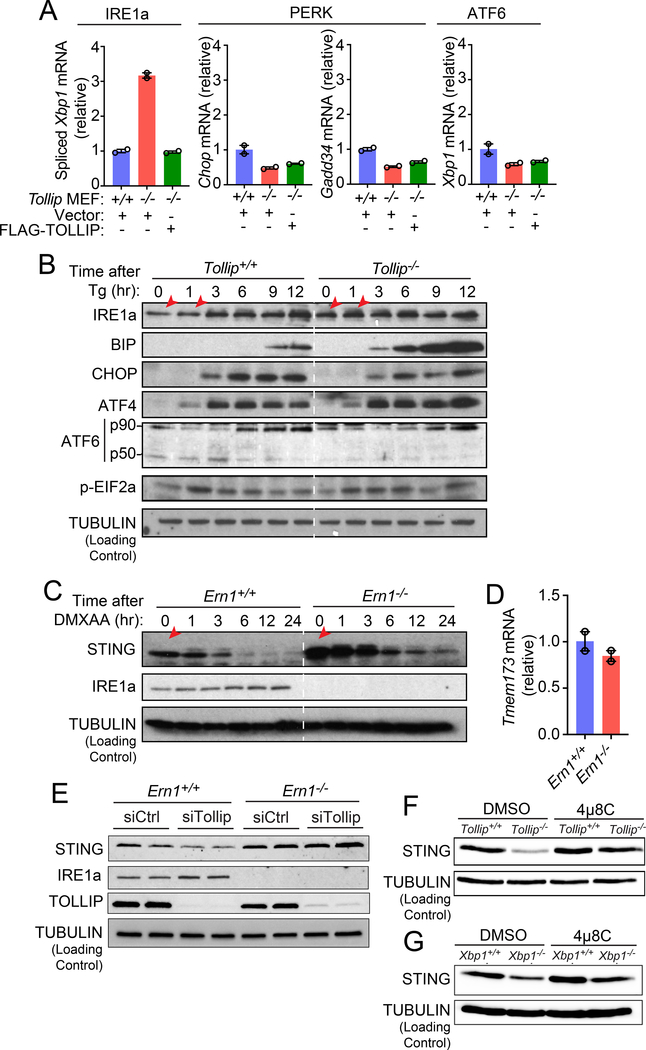

Tollip−/− hyperactivates the ER stress sensor IRE1α

We next investigated how STING protein is degraded in Tollip−/− cells. It was previously shown that STING gain-of-function mutant induces ER stress and the unfolded protein response (UPR) 19. Although STING signaling is not activated in Tollip−/− cells (Figure 2G), we wondered whether ER stress and the UPR could in turn regulate homeostasis of STING at the resting-state. Mammalian cells contain three major UPR effectors, IRE1α, PERK and ATF6. To assess whether the UPR is activated in Tollip−/− cells, we measured several UPR-dependent genes that are known to be activated through either one of the three major UPR pathways. ATF6- or PERK-dependent genes such as Chop, Gadd34 and Xbp1 mRNA were not induced in Tollip−/− cells compared to Tollip+/+ cells (Figure 6A). In contrast, spliced Xbp1 mRNA, a marker for IRE1α activation, was significantly upregulated in Tollip−/− cells compared to Tollip+/+ cells (Figure 6A). Stable expression of wild type TOLLIP suppressed Xbp1 mRNA splicing in Tollip−/− cells back to wild type levels (Figure 6A).

Figure 6: Tollip-deficiency selectively activates IRE1α, which facilitate resting-state STING protein turnover.

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of basal expression of UPR genes in Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− MEFs stably expressing an empty vector or Flag-TOLLIP. A representative experiment with 2 biological replicates is showing. Experiments were repeated three times.

(B) Immunoblot analysis of UPR proteins in Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− MEFs treated with thapsigargin (Tg, 500 nM) for indicated amount of time (top). Red arrows denote increased IRE1α in Tollip−/− MEFs.

(C) Immunoblot analysis of Ern1+/+ and Ern1−/− MEFs stimulated with DMXAA (10 μg/ml) for indicated amount of time (top).

(D) qRT-PCR analysis of basal Tmem173 mRNA in Ern1+/+ and Ern1α−/− MEFs. A representative experiment with 2 biological replicates is showing. Experiments were repeated three times.

(E) Immunoblot analysis of Ern1+/+ and Ern1−/− MEFs after treatment with control siRNA or siTollip.

(F) Immunoblot analysis of Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− MEFs treated with DMSO or IRE1α inhibitor 4μ8C (100 μM) overnight.

(G) Immunoblot analysis of Xbp1+/+ and Xbp1−/− MEFs treated with DMSO or 4μ8C (100 μM) overnight. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

To substantiate these findings, we next assessed UPR proteins after treating cells with thapsigargin (Tg) to induce ER stress. Tollip−/− cells showed increased total IRE1α at the resting-state as well as after Tg treatment (time 0 and 1 h, Figure 6B). Consistent with increased IRE1α, we also observed a remarkable increase in downstream BIP protein, an IRE1α-regulated chaperone, in Tollip−/− compared to Tollip+/+ cells (Figure 6B). In contrast, other UPR effectors such as CHOP, phospho-eIF2α and ATF4 (downstream of PERK), and ATF6, were induced equally by Tg in Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− cells. We also did not observe any difference in UPR proteins comparing Tg-treated Tmem173+/+ and Tmem173−/− MEFs (Supplementary Figure 2). These data suggest that Tollip-deficiency leads to hyperactivation of IRE1α, which may then facilitate STING turnover.

IRE1α promotes resting-state STING turnover independently of the ER stress pathway transcription factor XBP1

We next assessed whether IRE1α promotes resting-state STING turnover. We found a substantially higher amount of STING protein in in Ern1−/− (the Ern1 gene encodes IRE1α) compared to Ern1+/+ cells (Figure 6C). Tmem173 mRNA levels were similar in both cells (Figure 6D). Tollip-knockdown led to reduced STING protein in Ern1+/+ but not Ern1−/− cells, suggesting that IRE1α is required for STING protein turnover in cells lacking TOLLIP (Figure 6E). In a complimentary experiment, we inhibited IRE1α activity with a small molecule compound 4μ8C in Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− cells. Treatment of Tollip−/− cells with 4μ8C restored STING protein to amounts observed in Tollip+/+ cells, further supporting that STING turnover in Tollip−/− cells is mediated through IRE1α (Figure 6F).

When IRE1α is activated, it cleaves Xbp1 mRNA to its spliced form to produce mature XBP1 protein that activates a variety of UPR genes. However, Xbp1−/− cells displayed reduced amounts of STING protein similar to that of the Tollip−/− cells (Figure 6G). Several studies have shown that IRE1α is chronically activated in Xbp1−/− cells due to the loss of a regulatory feedback loop 20–22. We thus treated Xbp1−/− cells with 4μ8C to inhibit IRE1α, which restored STING protein to the wild type amounts. These data suggest that Tollip−/− hyperactivates IRE1α, then IRE1α promotes resting-state STING protein turnover independently of XBP1.

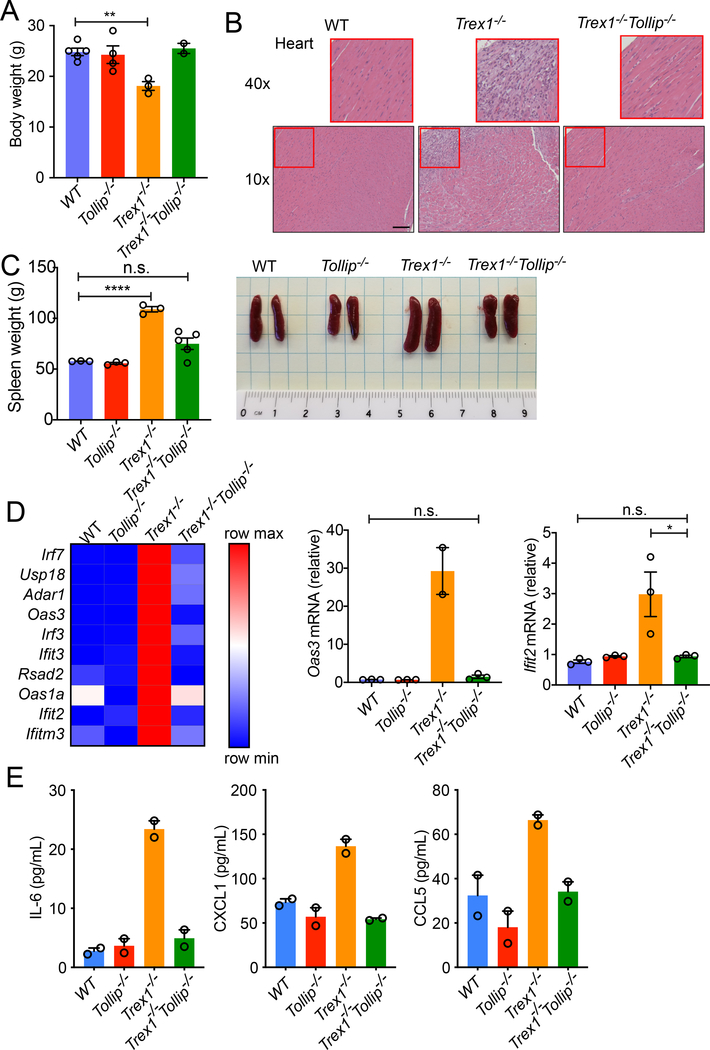

Tollip−/− ameliorates STING-mediated autoimmune disease in Trex1−/− mice

To assess whether TOLLIP regulates STING function in vivo, we crossed Tollip−/− mice to Trex1−/− mice, which develop autoimmune and autoinflammatory disease in a STING-dependent manner 3. Genetic ablation of one or both copies of Tmem173 rescues Trex1−/− mouse survival 6.

We found that Tollip−/− substantially rescued Trex1−/− mouse disease phenotypes. Trex1−/−Tollip−/− mice are equal in size and weight as Tollip+/+ or Tollip−/− mice, whereas Trex1−/− mice show significantly reduced body weight (Figure 7A). Trex1−/− mice develop splenomegaly, inflammation in the heart, and eventually succumb to inflammatory myocarditis 7. We found that Trex1−/−Tollip−/− heart lacked signs of inflammatory cell infiltrates and is much improved compared to the Trex1−/− mouse heart (Figure 7B). Trex1−/−Tollip−/− spleen was also significantly smaller compared to Trex1−/− mice (Figure 7C). Trex1−/−Tollip−/− BMDMs show significantly reduced expression of ISGs compared to Trex1−/− BMDMs (Figure 7D). Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, CXCL1 (also known as KC) and CCL5 (also known as RANTES) were also significantly reduced in Trex1−/−Tollip−/− serum compared to Trex1−/− (Figure 7E). These data demonstrate that Tollip-deficiency impairs STING signaling and ameliorates STING-mediated autoimmune and autoinflammatory disease in vivo.

Figure 7: Tollip−/− ameliorates autoinflammatory disease of Trex1−/− mice.

(A-C) Body weight (A), heart H&E staining (B) and spleen (C) from 16-week-old mice of indicated genotypes. n=8 mice. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(D) A heat map of ISGs expression in BMDMs of indicated genotypes. Each ISG mRNA expression level was measured by qRT-PCR. Two representative ISGs, Oas3 and Ifit2, are showing on the right. A representative experiment with 2 biological replicates is showing. Experiments were repeated three times.

(E) Serum cytokine measurement. n=2 mice. For panel A, C, D, *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. Error bars represent the SEM. Unpaired Student’s t test (2-sided).

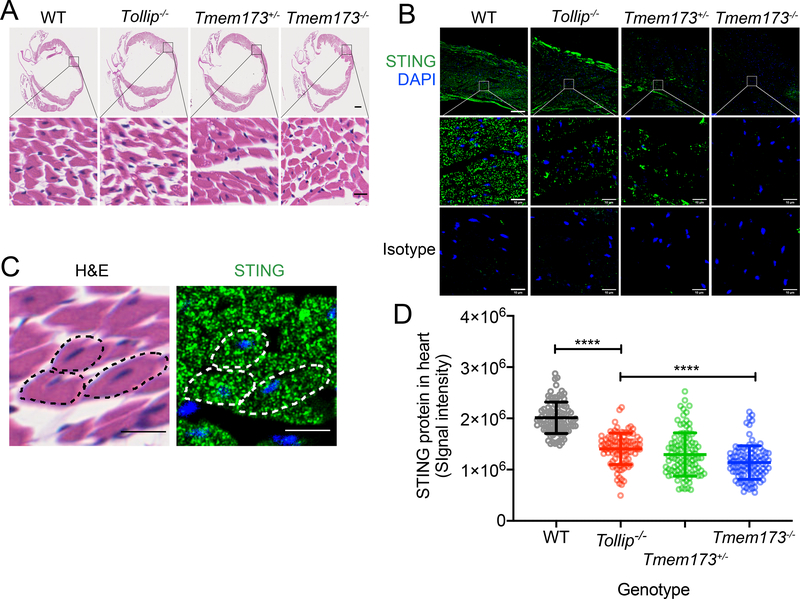

TOLLIP stabilizes STING protein in tissues

Detecting endogenous STING protein in tissues by fluorescent immunohistochemistry (IHC) has been technically challenging in the past. We developed an IHC procedure with a recently available anti-STING antibody that allowed us to reliably detect STING protein (see Method). To ensure reliability and reproducibility, we included isotype antibody and Tmem173−/− mice as negative controls. We also included Tmem173+/− as a control for reduced STING protein amounts.

We first analyzed wild type, Tollip−/− and Tmem173+/− and Tmem173−/− mouse heart (a key tissue that is relevant to Trex1−/− disease). H&E staining revealed no abnormality in hearts from either genotype (Figure 8A). IHC staining of STING protein revealed abundant STING protein signal in cardiomyocytes in wild type mouse heart while both Tollip−/− and Tmem173+/− mice showed significantly reduced STING protein in cardiomyocytes (Figure 8B–8D, Supplementary Figure 3). Very little signal was detected in Tmem173−/− mice or with the isotype control antibody. STING protein staining pattern in cardiomyocytes resembles that of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) that surrounds muscle fibers, which is equivalent to the ER in non-muscle cells (Figure 8C).

Figure 8. STING protein level is reduced in Tollip−/− mouse heart tissue.

(A) H&E staining of fixed mouse heart from indicated genotypes (top). Top images showing the whole heart and bottom images showing enlarged view of cardiomyocytes. Scale bars, 500 μm (upper panels) and 10 μm (lower panels).

(B) Fluorescent immunohistochemistry staining with anti-STING (top, and enlarged view at the middle) or Isotype antibody (bottom). STING in green and DAPI in blue. Scale bars, 60 μm (upper panels) and 10 μm (middle and lower panels).

(C) A representative enlarged view of cardiomyocytes in wild type heart stained for H&E (left) anti-STING (right) using adjacent tissue slides cut from the same paraffin-embedded block. Dotted lines indicate the same three cardiomyocytes from both images. Scale bars, 10 μm (both panels).

(D) Quantification of STING protein fluorescent intensity from B. Four separate areas were chosen from each heart and 25 region-of-interests (ROIs) were randomly chosen from each area (see Supplementary Figure 3). STING fluorescent signal intensity from 100 ROIs are showing for each genotype. ****, P < 0.001. Error bars represent the SEM. Unpaired Student’s t test (2-sided).

Experiments were repeated three times using different mouse of each genotype.

We also analyzed STING expression in T cells, B cells, dendritic cells (DCs), bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs), bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) from wild type, Tollip−/−, Tmem173+/− and Tmem173−/− mice by immunoblot and flow cytometry (Supplementary Figure 4A–C). We observed ~50% reduction of STING protein in Tmem173+/− compared to wild type. Tollip−/− immune cells did not show substantially reduced STING protein at the resting-state; however, low-dose DMXAA stimulation (2.5 μg/mL, mimics chronic activation) led to rapid STING degradation in Tollip−/− BMDMs and BMDCs but not in wild type cells, while high-dose DMXAA degrades STING quickly in all conditions (Supplementary Figure 4C). Together, these data suggest that Tollip−/− leads to substantially reduced resting-state STING protein level in nonhematopoietic cells and tissues and renders STING protein unstable in immune cells (see a model in Supplementary Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Homeostatic regulation is an area of STING biology that was incompletely understood. Much of the regulatory mechanisms described to date were focused on STING activation and downstream signaling. Here, we identified TOLLIP as a critical cofactor that directly interacts with STING and stabilizes it on the ER at the resting-state. We also determined the competing degradation mechanism for STING at the resting-state that involves IRE1α activation and lysosome function. Therefore, our study reveals that resting-state STING protein is strictly regulated by a constant tug-of-war between ‘stabilizer’ TOLLIP and ‘degrader’ IRE1α-lysosome. Cells lacking either activities result in drastic swings of STING protein levels to either low (Tollip−/−) or high (Ern1−/−) levels. This type of homeostatic regulation is fundamentally important for STING biology in disease settings, since Tollip−/− rescued STING-mediated autoinflammatory disease in Trex1−/− mice. Chronic IFN signaling originates from nonhemopoietic cells in Trex1−/− mouse heart (by genetic linage tracing experiments 6) and Trex1−/− mice succumb to inflammatory myocarditis 7. Consistent with this, we confirmed by fluorescent IHC that STING protein is substantially reduced in cardiomyocytes in Tollip−/− mouse hearts.

We also found that STING protein level is more substantially reduced in nonhemopoietic tissues compared to hemopoietic cells in Tollip−/− mice. As a comparison, Tmem173+/− mice show ~50% STING protein in both. This suggests that the balance between stabilization and turnover of STING may vary in different cell types; immune cells may shift the balance towards stabilization to ascertain STING-mediated anti-microbial capacity. We showed that a low-dose DMXAA stimulation (that mimics chronic low-level STING activation) can shift this balance back in immune cells, likely by boosting lysosomal degradation. This balance may also depend on expression levels of TOLLIP and IRE1α as well as other unknown components on either side. Another potentially interesting aspect of this mechanism is that TOLLIP may communicate with IRE1α to ‘set’ the homeostatic balance of STING protein level. For example, in yeast, TOLLIP is required for clearance of certain protein aggregates, and Tollip loss-of-function results in depletion of ER protein chaperone and activation of ER stress 23. This could explain how IRE1α is activated in Tollip−/− cells. Whether this exact mechanism in yeast also applies in mammals requires further study.

Another intriguing observation is diminished STING protein and its signaling capacity when polyQ protein accumulates in the cell. TOLLIP has been shown to promote clearance of Hungtington’s disease (HD)-linked polyQ proteins 17. We showed here that polyQ protein disrupts TOLLIP:STING interaction and results in STING degradation by lysosomes. Using a knock-in mouse model of HD that expresses polyQ protein zQ175, we found that STING protein but not mRNA is significantly reduced in the striatum, which is the area of brain most affected by HD. It remains unclear which cell type STING is most affected in and whether reduced STING protein contributes to neurodegeneration. STING-mediates multiple IFN-dependent and IFN-independent signaling pathways such as inflammation, cell proliferation, cell survival, calcium flux and autophagy 19,24–27. STING-mediated inflammation has been implicated in promoting microglia activation and neuronal death in a Parkinson’s disease mouse model 25. Whether STING also plays a role in HD or other neurodegenerative disease will be an exciting area of future investigation. Together, our study uncovers a homeostatic regulatory mechanism of STING protein at the resting-state by competing activities between TOLLIP and IRE1α-lysosome that together maintains tissue immune homeostasis.

METHODS

Mice, cells, and viruses

Tollip−/− mice were obtained from Dr. Michel Maillard (CHUV). Primary MEFs were isolated from embryos of either E10 or E13.5 embryonic dates. HEK293T cells were obtained from ATCC. These cells were maintained in DMEM with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM Hepes, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (complete DMEM) with the addition of 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin and were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2. All tissue culture cells were tested for Mycoplasma on monthly basis and were confirmed negative. Experiments performed in BSL-2 conditions were approved by the Environmental Health and Safety Committee at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Experiments involving mouse materials were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Reagents and antibodies

Herring testis DNA was used as dsDNA for immune stimulations (Sigma). 2’3’-cGAMP and DMXAA were used for STING agonists (Invivogen). PolyI:C was transfected as a MAVS-pathway agonist (Invivogen). Lipofectamine 2000 was used as transfection reagent for intracellular stimulations (Thermo Fisher).

Antibodies: ATF4 (CST D4B8), ATF6 (CST D4Z8V), BIP (CST C50B12), CHOP (CST L63F7), phospho-EIF2α (CST D968), HMGB1 (Abcam 18256), IRAK1 (CST D5167), IRE1α (CST 14C10), phospho-IRE1α (Thermo Fisher PA1-16927), IRF3 (CST D83B9), phospho-IRF3 (CST 4D4G), MAVS (CST 4983), STING (CST D2P2F), TOLLIP (Abcam ab187198), goat anti-rabbit IgG (Biorad 1706515), goat anti-mouse IgG (Biorad 1706516).

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (150mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, 50mM Tris, 1.0% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors then centrifuged at 4°C to obtain cellular lysate. Equal amounts of protein (10–50μg) were loaded into a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. Semi-dry transfer onto nitrocellulose membrane was performed. Membrane was blocked in 5% milk in TBS-T buffer for one hour at room temperature, followed by overnight incubation in 3% milk in TBS-T with primary antibodies. Membrane was washed with TBS-T buffer, incubated at room temperature with HRP-conjugated IgG secondary antibody, washed with TBS-T, and then developed with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher) or SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Wild type MEFs or HEK293T transfected with indicated plasmids were collected, washed once with PBS, lysed in IP lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40 and 1X protease inhibitor mixture) and centrifuged at 20,000g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were mixed with primary antibody and Dynabeads Protein G (Life Technology) and incubated overnight at 4°C. A small portion of supernatant was saved as input. The following day, the beads were washed once with IP buffer, then, twice with high salt IP buffer (500mM NaCl) and finally once with low salt IP buffer (50mM). Immunoprecipitated complex was eluted in immunoblot sample buffer and boiled at 95°C for 5min. Samples were analyzed by immunoblot as above.

Compound inhibition

Protein degradation pathway inhibition: Cells were seeded overnight, then treated with 5mM 3-MA (Invivogen tlrl-3ma), 0.5μM Bafilomycin A1 (Invivogen tlrl-baf1), and 5μM MG-132 (Sigma 133407-82-6) for 16 hours. Cells were then collected and lysed in RIPA buffer for immunoblot analysis. IRE1α inhibition: Cells were seeded overnight, and then treated with 100μM 4μ8C (Sigma SML0949) for 24 hours. Cells were then collected and lysed in RIPA buffer for immunoblot analysis.

siRNA knockdown

Pre-designed siRNA oligomers were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and re-suspended in water at 20μM. 105 MEFs were plated and transfected with siRNA in Optimem media (Thermo Fisher) for 48 hours with lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher) then validated for knockdown efficiency with RT-PCR or immunoblotting. Oligos with efficient knockdowns (>50% mRNA reduction) were used in subsequent experiments. siTollip#1, sense sequence (5’−3’), CCAUCAAUCCUUGCUGCA; antisense sequence, UGCAGCAAGGAAUUGAUGG. siTollip#2, sense, GCACUUACUUACAGGUUAU; antisense, AUAACCUGUAAGUAAGUGC. siTollip#3, sense, GAGUUCAUGUGCACUUACU; antisense, AGUAAGUGCACAUGAACUC. siTollip#4, sense, CCAAGAACCCUCGCUGGAA; antisense, UUCCAGCGAGGGUUCUUGG.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated with TRI reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Sigma-Aldrich), and cDNA was synthesized with iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and an ABI-7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) were used for quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

Cycloheximide chase assay

Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− MEFs were seeded into 6-well plates and incubated overnight. Cells were treated with cycloheximide (50 μg/ml) and chased for 4 h, 8 h and 12 h. Cell lysates were collected at indicated time points and analyzed for STING and IκBα proteins using immunoblot.

Quantification of protein degradation by AHA labeling/tandem mass tag (TMT) mass spectrometry

Tollip+/+ and Tollip−/− MEFs were seeded into 10-cm plates and incubated overnight. Cells were washed once with warm PBS and refed with methionine-free medium (Gibco, cat. no. 21013) for 1 h to deplete methionine reserve. Then cell culture medium was replaced with methionine-free one containing 50 μM AHA (L-azidohomoalanine) (Invitrogen, cat. no. C10102) for 4 h to label nascent proteins. After labeling, cells were refed with normal medium and chased for indicated time. At each time point, cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in 1% SDS in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 250 U/ml Benzonase endonuclease. Cell lysate was centrifuged at 16,000 g for 5 min to remove debris. AHA-labeled nascent proteins in cell lysates were biotinylated using Click-iT Protein Reaction Buffer Kit (Invitrogen, cat. no. C10276) with biotin-alkyne (Invitrogen, cat. no. B10185) per manufacturers’ instructions. Biotinylated nascent proteins were further pulled down using Streptavidin magnetic beads (Pierce, cat. no. 88817). Precipitated biotinylated nascent proteins were quantified using tandem mass tag (TMT) mass spectrometry in UT Southwestern Proteomics Core. Data were analyzed using Proteome Discoverer 2.2 and was searched using the mouse database from Uniprot.

Fluorescent Microscopy

Cells were grown on glass coverslips and treated as indicated. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% TritonX-100, blocked with 5% normal donkey serum. Slides were incubated with primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature followed by fluorescent-conjugate secondary antibody incubation and mounted with VECTASHIELD Mounting Media containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories).

Histology and Fluorescent Immunohistochemistry

Mice were euthanized and perfused with 1X Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) followed by formalin. Tissues were collected and incubated for 24 hours in 10% buffered formalin, and then transferred to 70% ethanol for 24 to 48 hours. Tissues were imbedded in paraffin embedding blocks and 5 μM sections were prepared on slides. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining was performed by the UT Southwestern Molecular Pathology Core.

The pathology slides were washed sequentially in xylene three times for 3 minutes each, absolute (100 %) ethanol three time for 3 minutes each, 95% ethanol three times for 3 minutes and the final wash with water two times for 5 minutes each. Antigen retrieval was performed by autoclaving the slides in citric acid solution at 121 degrees for 20 minutes. These samples were cooled to room temperature overnight. After antigen retrieval, slides were washed twice in water for 5 minutes, PBS for 5 minutes one time and PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 once for 5 minutes. Slides were blocked for 1 to 4 hours with 10% normal goat serum in 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) and PBS at room temperature. The blocking solution was poured off, but the slides were not washed. The samples were incubated with primary Rabbit anti-STING antibody (Proteintech, catalogue #19851-1-AP, 0.33 mg/mL) diluted to 1:200 in 1% BSA in PBS or in Isotype control antibody Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (Sigma Aldrich catalogue #R5506, 1 mg/mL) diluted at 1:600 in 1% BSA in PBS incubated overnight at 4 degrees. The next day slides were warmed to room temperature and washed three times for 3 minutes each in PBS with 0.1% Tween. Slides were then incubated at room temperature for 1 hour with secondary antibody Goat anti-Rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen). Slides were washed three times for 5 minutes each with PBS with 0.1% Tween and then two times for 5 minutes each with PBS. To reduce the amount of autofluorescence in the background cardiac tissues, the Vector TrueVIEW Autofluorescence Quenching Kit (catalogue# SP-8400) was used right before mounting per manufacturer’s instructions before mounting. Tissues were stained and mounted with ProLong Glass Antifade Mountant with NucBlue stain (ThermoFisher, catalogue # P36983).

Images of the H&E staining slides were acquired using a NanoZoomer 2.0-HT digital slide scanner (Hamamatsu). Immunofluorescence images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope (Zeiss). Further deconvolution was performed using the Autoquant X software (Media Cybernetics). For intensity quantification, four different areas were selected within the specific tissue and each area were sampled by twenty-five smaller regions of interest (ROI) using Image J.

Statistical methods

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Prism 6 (GraphPad) was used for statistical analysis. Statistical tests performed are indicated in figure legends. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; and ****, P < 0.0001.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Maillard (CHUV) for Tollip−/− mice. M. Lehrman (UT Southwestern) for Ern1+/+, Ern1−/−, Xbp1+/+ and Xbp1−/− MEFs, U. Deshmukh (OMRF) for the initial IHC protocol, members of the Yan lab for helpful discussion. This work is supported by National Institutes of Health (AR067135 and AI134877 to N.Y., NS0870778 and NS052325 to R.G.K.) and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (N.Y.).

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Tan X, Sun L, Chen J & Chen ZJ Detection of Microbial Infections Through Innate Immune Sensing of Nucleic Acids. Annu Rev Microbiol 72, 447–478 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobbs N et al. STING Activation by Translocation from the ER Is Associated with Infection and Autoinflammatory Disease. Cell Host Microbe (2015). doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan N Immune Diseases Associated with TREX1 and STING Dysfunction. J Interferon Cytokine Res 37, 198–206 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao D et al. Activation of cyclic GMP-AMP synthase by self-DNA causes autoimmune diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 201516465 (2015). doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516465112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray EE, Treuting PM, Woodward JJ & Stetson DB Cutting Edge: cGAS Is Required for Lethal Autoimmune Disease in the Trex1-Deficient Mouse Model of Aicardi-Goutières Syndrome. J Immunol 195, 1939–1943 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gall A et al. Autoimmunity Initiates in Nonhematopoietic Cells and Progresses via Lymphocytes in an Interferon-Dependent Autoimmune Disease. Immunity 36, 120–131 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morita M et al. Gene-targeted mice lacking the Trex1 (DNase III) 3’-->5’ DNA exonuclease develop inflammatory myocarditis. Mol Cell Biol 24, 6719–6727 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo W-W et al. iRhom2 is essential for innate immunity to DNA viruses by mediating trafficking and stability of the adaptor STING. Nat Immunol 17, 1057–1066 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang M et al. USP18 recruits USP20 to promote innate antiviral response through deubiquitinating STING/MITA. Cell Res 26, 1302–1319 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong B et al. The ubiquitin ligase RNF5 regulates antiviral responses by mediating degradation of the adaptor protein MITA. Immunity 30, 397–407 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xing J et al. TRIM29 promotes DNA virus infections by inhibiting innate immune response. Nat Commun 8, 945 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y et al. TRIM30α Is a Negative-Feedback Regulator of the Intracellular DNA and DNA Virus-Triggered Response by Targeting STING. PLoS Pathog 11, e1005012 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burns K et al. Tollip, a new component of the IL-1RI pathway, links IRAK to the IL-1 receptor. Nat Cell Biol 2, 346–351 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonugunta VK et al. Trafficking-Mediated STING Degradation Requires Sorting to Acidified Endolysosomes and Can Be Targeted to Enhance Anti-tumor Response. Cell Rep 21, 3234–3242 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warner JD et al. STING-associated vasculopathy develops independently of IRF3 in mice. J Exp Med jem.20171351 (2017). doi: 10.1084/jem.20171351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang K, Huang R, Fujihira H, Suzuki T & Yan N N-glycanase NGLY1 regulates mitochondrial homeostasis and inflammation through NRF1. J Exp Med 546, jem.20180783 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu K, Psakhye I & Jentsch S Autophagic clearance of polyQ proteins mediated by ubiquitin-Atg8 adaptors of the conserved CUET protein family. 158, 549–563 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menalled LB, Sison JD, Dragatsis I, Zeitlin S & Chesselet M-F Time course of early motor and neuropathological anomalies in a knock-in mouse model of Huntington’s disease with 140 CAG repeats. J. Comp. Neurol. 465, 11–26 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu J et al. STING-mediated disruption of calcium homeostasis chronically activates ER stress and primes T cell death. J Exp Med jem.20182192 (2019). doi: 10.1084/jem.20182192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fink SL et al. IRE1α promotes viral infection by conferring resistance to apoptosis. Sci Signal 10, eaai7814 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hur KY et al. IRE1α activation protects mice against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. J Exp Med 209, 307–318 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aden K et al. ATG16L1 orchestrates interleukin-22 signaling in the intestinal epithelium via cGAS-STING. J Exp Med 215, jem.20171029–2886 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duennwald ML & Lindquist S Impaired ERAD and ER stress are early and specific events in polyglutamine toxicity. Genes Dev 22, 3308–3319 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gui X et al. Autophagy induction via STING trafficking is a primordial function of the cGAS pathway. Nature 339, 786 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sliter DA et al. Parkin and PINK1 mitigate STING-induced inflammation. Nature 302, 89–262 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.