Abstract

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) now have expedited review procedures for new drugs. We compared the review times of medicines licensed by the 2 agencies and explored differences in the evidence submitted. In 2015–2017 the FDA licensed 113 drugs, 66 of which reached Europe. The median review time was longer at the EMA than FDA and was shorter for drugs undergoing FDA‐expedited programmes compared to the same drugs approved by the EMA through the standard procedure. We identified differences regarding the evidence submitted to the 2 regulators for 7 drugs. The greater use of expedited programmes by the FDA and administrative time at the European Commission mainly explain the later access of new drugs to the European market. The additional evidence submitted to the EMA is generally scant and limited to a few drugs.

Keywords: drug regulation, health policy, therapeutics

BOX 1 Expedited regulatory procedures and development support schemes at Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA).

FDA

Accelerated Approval (1992): to allow drugs for serious conditions that fill an unmet medical need to be approved on the basis of surrogate endpoints.

Priority Review (1992): to ensure decision on an application within 6 months.

Fast Track (1988, codified in 1997): to facilitate the development, and expedite the review of drugs to treat serious conditions and fill an unmet medical need (early and frequent communication between FDA and company during drug development and eligibility for accelerated approval and priority review).

Breakthrough Therapy (2012): to expedite the development and review of drugs when preliminary evidence indicates substantial improvement over available therapies.

EMA

Exceptional circumstances (1995): Authorisation granted for objective, verifiable reasons and subject to a requirement for the applicant to introduce specific procedures, in particular concerning the safety of the medicinal product. Continuation of the authorisation is linked to annual reassessment.

Conditional approval (2006): Authorisation granted to meet unmet medical needs of patients and in the interests of public health based on less complete data than is normally the case. Continuation of the authorisation is linked to the fulfilment of specific obligations.

PRIME (2016): To accelerate the development of drugs that target diseases where there is an unmet medical need and may offer a major therapeutic advantage over existing treatments, or benefit patients without treatment options.

What is already known about this subject

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) now have expedited programmes to accelerate review procedures for new drugs.

Most new drugs are first approved in the USA and the FDA reviews applications more quickly than EMA.

What this study adds

The median review time for the drugs approved by both agencies was longer at the EMA than FDA, especially for drugs undergoing FDA expedited programmes compared to the same drugs approved by the EMA through the standard procedure.

The time taken by the European Commission to finalise drug authorisations accounts for half the difference between the review times at the 2 agencies.

The applicants submit additional, though generally scant, evidence to the European regulator for a limited number of new drugs.

1. BACKGROUND

Regulatory agencies face constant pressure to speed up the development, review and approval of drugs for serious diseases. Both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) support clinical drug development and accelerated review and authorisation procedures (Box 1).1 These programmes are intended to meet the expectations of drug manufacturers and patients, the former eager to launch new drugs promptly to maximise the return on investment and the latter to have access to potentially innovative therapies as soon as possible. Expedited programmes implemented by the FDA provide shorter overall review times than standard ones,2 and account for the reportedly faster process than at the EMA.3, 4, 5, 6

The earlier application and shorter review times at the FDA compared to the EMA may offer the European agency the possibility to assess the same drugs on the basis of more comprehensive information. To test this, we first assessed the delays in the application dates of the novel drugs—namely, new molecular entities and original biologic agents—licensed by both FDA and EMA, and compared their review times. Then we explored the differences in the evidence available at the time of EMA approval of medicines already licensed by the FDA through expedited programmes.

2. METHODS

We identified the drugs approved by the FDA from January 2015 through December 2017 using 3 reports published by the agency.7, 8, 9 We extracted the date of approval, information on the type of authorisation procedure, and information on the evidence submitted in the marketing authorisation (MA) application from the Drugs@Fda database.1, 10 Review times in USA were calculated as the number of days elapsed from the Investigational New Drug application to the first FDA approval. Investigational New Drug application dates were obtained from FDA documents and administrative correspondence. We classified applications as either expedited or non‐expedited procedures (Box 1).

For all novel therapeutics approved by the FDA we searched the EMA website11 from January 2015 to the first quarter of 2018 and extracted the date, type of approval (standard, conditional or under exceptional circumstances), and the authorisation details. Information on the evidence submitted by the applicant was collected from the European Public Assessment Report and the summary of the opinion of the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) available on the EMA website.11 Review times in the EU were calculated as the number of days elapsed from the MA application to the date of the final authorisation by the European Commission (EC) to market the drug.

According to the above definitions, review times correspond to the time from submission to marketing authorisation and encompass the time devoted to the assessment of drug application documents and the time left for administrative processes. Additional time may be needed until actual market access, depending on national regulatory contexts. For drugs approved by both agencies we also calculated the number of days elapsed from the MA application at the 2 agencies.

The review times were reported as medians with their interquartile ranges (IQRs). Analyses were done with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

For the novel therapeutics licensed by FDA through at least 1 of the expedited programmes and marketed in the EU by March 2018, 2 reviewers independently extracted data about the pivotal trials from the documents described above. The information about trial phase, primary endpoints, comparator, trial results (including the cut‐off date and whether final or interim results were available), basis for approval and possible concerns on the drugs was summarised. Differences were solved by consensus.

3. RESULTS

In the period 2015–2017 the FDA licensed 113 novel drugs, 55 through the non‐expedited procedure and 58 through 1 or more expedited programmes. Of these, 66 were licensed in the EU by the first quarter of 2018. Only 6 were authorised before 2015 (trabectedin in 2007; sugammadex in 2008; insulin degludec, lixisenatide and defibrotide in 2013; and daclatasvir in 2014). Of the 58 drugs authorised by the FDA in 1 or more accelerated programmes, 32 reached the EU market by March 2018. Of the 47 drugs (113–66) approved by the FDA but not yet by the EMA by March 2018 all but 3—benznidazole (Chagas disease), seconidazole (bacterial vaginosis) and plecanatide (chronic idiopathic constipation)—fall into the scope of the EMA and therefore will be (or have already been) assessed by the European agency.

3.1. Review times for drugs approved by both FDA and EMA

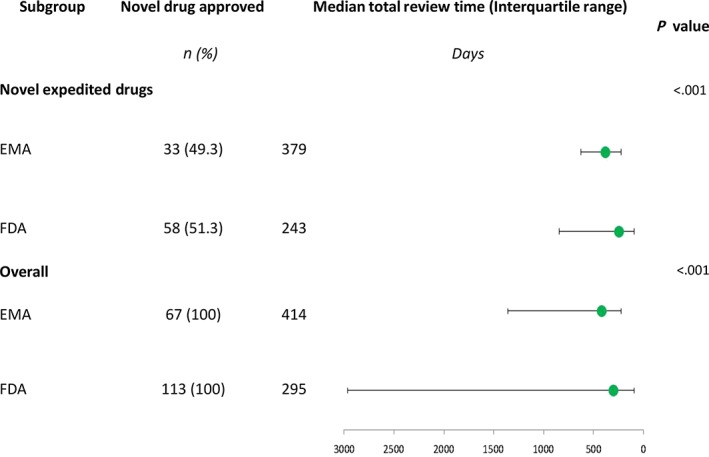

The median review time for the 66 drugs approved by both agencies was longer at the EMA than at the FDA (median difference 121.5 days, IQR 29 to 189, Figure 1). This lag includes the 60 days that is the median period taken by the EC to grant the marketing authorisation on the basis of the CHMP's positive opinion. The median review time was also shorter for drugs undergoing FDA expedited programmes than for the same drugs approved by the EMA, all of which underwent the standard procedure, i.e. with no accelerated assessment (median difference 138 days, IQR 50 to 176.5, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Median total review time in days for novel drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the period 2015–2017 and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) by March 2018

The median delay of submitting the applications to the EMA compared to the FDA was 7 days (IQR −21 to 57) for all 66 drugs approved by both agencies and 7.5 days (IQR −9 to 64) for those licensed by the FDA through expedited programmes.

3.2. Differences in evidence submitted to FDA and EMA

For the 32 drugs authorised by the FDA through expedited programmes and also licensed by the EMA we examined the pivotal trials in the dossiers submitted to both agencies. We only identified differences in the evidence supporting the applications for 7 drugs: the combination avibactam + ceftazidime; ribociclib; tipiracil + trifluridine; nusinersen; atezolizumab; venetoclax; and the combination sofosbuvir + velpatasvir + voxilaprevir.

For avibactam + ceftazidime larger studies were submitted to the EMA, which also authorised more indications than the FDA: intra‐abdominal infection, urinary tract infection, nosocomial pneumonia, aerobic Gram‐negative infections, instead of only intra‐abdominal infection and urinary tract infection. For ribociclib more definitive and precise progression‐free survival data were presented to the EMA which, however, led to no regulatory action. For tipiracil + trifluridine longer follow‐up data were submitted to the EMA, indicating a higher risk of adverse events in patients with moderate renal impairment, but no substantial change in the median overall survival (1.8 months at the end of the first follow‐up [FDA] vs 2 months at the end of the second follow‐up [EMA]).

Although the EMA dossier for nusinersen included more mature data from the pivotal trial presented to the FDA and data from an ongoing phase III trial on later‐onset patients, no additional indications were approved, and no additional information was reported except for adverse events in patients undergoing lumbar puncture.

Atezolizumab was authorised by the EMA for urothelial carcinoma and non‐small‐cell lung cancer. For the first indication the EMA dossier included the interim results of a phase III trial which was not submitted to the FDA. The indication for non‐small‐cell lung cancer was only licensed by the FDA after the authorisation for urothelial carcinoma.

The European agency reported a risk of tumour lysis syndrome but extended the indication of venetoclax to patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion or TP53 mutations on the basis of a supporting study that the FDA had not considered.

For sofosbuvir + velpatasvir + voxilaprevir the EMA also considered as pivotal trials 2 studies in the naïve population. Although the POLARIS 2 pivotal trial failed to meet its objective (non‐inferiority vs double therapy), the indication was not restricted to the treatment of non‐naïve patients as in the USA. The EMA also noted the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in spite of the use of this combination.

4. DISCUSSION

Our analysis confirms that although the companies apply almost simultaneously to FDA and EMA, most often new drugs are allowed onto the European market only after they have been authorised in the USA.4, 5, 6 Only 66 of the 113 novel therapeutics authorised by the FDA from 2015 up to 2017 were licensed in the EU by the first quarter of 2018, and only 6 of these had been authorised by EMA before 2015. Possibly, the earlier availability of new drugs in the USA means that higher prices can be set in a free market simply to generate extra profit12 and present them as a benchmark to European health technology assessors and payers.

We also confirmed that the FDA provided faster reviews of applications involving new medicines than EMA.4, 5, 6 Our findings on the overall sample are comparable to those previously reported by the most recent studies,5, 6 which showed a median difference of 66 and 67 days. Considering the median of 60 more days required for the EC decision after the CHMP's positive opinion, these figures are consistent with the median difference of 121 days found in our sample.

The greater use of expedited programmes by the FDA2, 6, 13, 14, 15 contributed to this difference, as review times were even shorter for the 32 drugs approved by the FDA through expedited programmes and then approved by the EMA following the standard process (Figure 1). The time elapsed between the positive opinion from the CHMP and the authorisation granted by the EC accounts for half the difference between the review times at the 2 agencies.

Later availability of new therapeutics may disappoint needy patients and their physicians. Sometimes European patients cannot benefit from effective treatments that have already been available in USA for months. However, according to our findings the small difference in the EU review times compared to USA can only partly account for such delays, which are more likely to be due mainly to the lengthy process of adoption of new medicines and price negotiation at national level. It may even happen that the delay allows fuller information to be available about the efficacy and safety profile of new drugs. At variance with other studies,4, 5, 6, 15 our analysis focused on differences in information submitted to the 2 agencies and undergoing FDA expedited procedures. However, our analysis indicates that compared to the evidence submitted to the FDA, by the time of the EMA approval there were few and relatively scant additional items of information regarding a minority of medicines. New information included data leading to additional indications (avibactam+ceftazidime and venetoclax), interim data from 1 confirmatory trial (atezolizumab), better efficacy data (ribociclib and nusinersen), longer follow‐up data though with no evidence of better efficacy (tipiracil+trifluridine). The EMA also granted a wider indication than the FDA to an anti‐HCV triple combination despite the fact that it could not be proved noninferior to a double therapy in naïve patients.

As regards the safety, the EMA noted a higher incidence of adverse events in patients with moderate renal impairment treated with tipiracil+trifluridine, and in patients treated with nusinersen undergoing lumbar puncture; a risk of tumour lysis syndrome in patients given venetoclax; and the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in spite of the use of sofosbuvir+velpatasvir+voxilaprevir in patients with HCV infection.

Our findings that the EMA approval process benefits from additional items of information only for a minority of medicines are in line with the results of a comparison of the marketing applications assessed by both the EMA and the FDA between 2014 and 2016. This study showed high concordance in the final decisions on marketing approvals (91% when only the initial decisions were considered, up to 98% including resubmission and re‐examination).16 Although this study did not focus on comparisons of times to submission and approval of an application, the authors reported that the main reason for (rare) discordant decisions was differences in conclusions about efficacy, followed by differences in the clinical data submitted.

In conclusion, we confirm that: (i) the majority of the new drugs approved by both FDA and EMA were first approved in the USA; (ii) the administrative process of authorisation by the European Commission is a not‐negligible component of the delayed access of new medicines to the European market; (iii) considering that the speed of the standard EMA review process causes no substantial delay in the access to new drugs in the EU, there appears to be no need for any further expedited programmes; and, finally, (iv) only in a few cases do the applicants submit additional—generally scant—evidence to the European regulator.

COMPETING INTERESTS

Being aware of the policy of the BJCP in this respect, the authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

CONTRIBUTORS

R.J. and V.B. proposed the analysis; R.J., R.B. and V.B. planned the study, retrieved and assessed the data, and interpreted the findings. T.V. did the statistical analysis. R.J., R.B. and V.B. drafted the initial manuscript; SG provided input in the data interpretation and critically revised the draft. All the authors approved the final manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Judith Baggott for editing. This study was supported by institutional funds of the Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCSS.

Joppi R, Bertele V, Vannini T, Garattini S, Banzi R. Food and Drug Administration vs European Medicines Agency: Review times and clinical evidence on novel drugs at the time of approval. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86:170–174. 10.1111/bcp.14130

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data utilised in the analysis derived from public domain resources available in the following:

Drugs@Fda database Approved Drug Products at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/ reference number 10;

European Medicines Agency—Find medicine at http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/landing/epar_search.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124, reference number 11

REFERENCES

- 1. US Food and Drug Administration . Guidance for industry: expedited programs for serious conditions—drugs and biologics. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm358301.pdf) Accessed March 14, 2019.

- 2. Hwang TJ, Darrow JJ, Kesselheim AS. The FDA's expedited programs and clinical development times for novel therapeutics, 2012‐2016. JAMA. 2017;318(21):2137‐2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marciniak TA, Serebruany V. Are drug regulators really too slow? BMJ. 2017;357 10.1136/bmj.j2867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Downing NS, Aminawung JA, Shah ND, Braunstein JB, Krumholz HM, Ross JS. Regulatory review of novel therapeutics‐‐comparison of three regulatory agencies. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):2284‐2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Downing NS, Zhang AD, Ross JS. Regulatory review of new therapeutic agents‐FDA versus EMA, 2011–2015. New Engl J Med. 2017;376(14):1386‐1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rawson NSB. Canadian, European and United States new drug approval times now relatively similar. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2018;96:121‐126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. US Food and Drug Administration . 2015 Novel drugs summary https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/druginnovation/ucm481709.pdf. Accessed 16 November, 2018.

- 8. US Food and Drug Administration . 2016 Novel drugs summary. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DrugInnovation/UCM536693.pdf. Accessed 16 November, 2018.

- 9. Food and Drug Administration . Center for drug evaluation and research advancing health through innovation 2017 new drug therapy approvals. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/ReportsBudgets/UCM591976.pdf. Accessed 16 November, 2018.

- 10. Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/ Accessed 16 November, 2018.

- 11. European Medicines Agency ‐ Find medicine. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/landing/epar_search.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124. Accessed date: 16 November, 2018.

- 12. Light DW, Caplan AL. Trump blames free riding foreign states for high US drug prices. BMJ. 2018;360:k1088 10.1136/bmj.k1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boucaud‐Maitre D, Altman JJ. Do the EMA accelerated assessment procedure and the FDA priority review ensure a therapeutic added value? 2006‐2015: a cohort study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72(10):1275‐1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kesselheim AS, Wang B, Franklin JM, Darrow JJ. Trends in utilization of FDA expedited drug development and approval programs, 1987‐2014: cohort study. BMJ. 2015;351:h4633 10.1136/bmj.h4633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centre for Innovation in Regulatory Science . https://www.cirsci.org/global-development-track/regulatory-metrics-snapshots/. Accessed 10 July 2019.

- 16. Kashoki M, Hanaizi Z, Yordanova S, et al. A comparison of EMA and FDA decisions for new drug marketing applications 2014–2016: concordance, discordance, and why. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019. 10.1002/cpt.1565 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data utilised in the analysis derived from public domain resources available in the following:

Drugs@Fda database Approved Drug Products at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/ reference number 10;

European Medicines Agency—Find medicine at http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/landing/epar_search.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124, reference number 11