Abstract

Background: Lack of quality preventive care has been associated with poorer outcomes for pregnant women with low incomes. Health policy changes implemented with the Affordable Care Act (ACA) were designed to improve access to care. However, insurance coverage remains lower among women in Medicaid nonexpansion states. We compared health care use and adverse birth outcomes by insurance status among women giving birth in a large health system in a Medicaid nonexpansion state.

Materials and Methods: We conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study using data for 9,613 women with deliveries during 2014–2015 at six hospitals associated with a large vertically integrated health care system in North Carolina. Adjusted logistic regression and zero-inflated negative binomial models examined associations between insurance status at delivery (commercial, Medicaid, or uninsured) and health care utilization (well-woman visits, late prenatal care, adequacy of prenatal care, postpartum follow-up, and emergency department [ED] visits) and outcomes (preterm birth, low birth weight, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes).

Results: Having Medicaid at delivery was associated with lower rates of well-woman visits (rate ratio [RR] 0.25, 95% CI 0.23–0.28), higher rates of ED visits (RR 2.93, 95% CI 2.64–3.25), and higher odds of late prenatal care (odds ratio [OR] 1.18, 95% CI 1.03–1.34) compared to having commercial insurance, with similar results for uninsured women. Differences in adverse pregnancy outcomes were not statistically significant after adjusting for patient characteristics.

Conclusions: Findings suggest that large gaps exist in use of preventive care between Medicaid/uninsured and commercially insured women. Policymakers should consider ways to improve potential and realized access to care.

Keywords: affordable care act, prenatal care, emergency visits, health disparities, pregnancy outcomes

Introduction

The United States has the highest maternal mortality rate in the developed world with an estimated 26.4 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2015 and is one of the few countries where maternal mortality is increasing.1 Similarly, rates of severe maternal morbidity, life threatening complications associated with delivery, are increasing.2 These increases and stark disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality have heightened focus on understanding and addressing the causes of poor pregnancy outcomes among women, especially those from marginalized groups.3,4 Current evidence suggests that variations in obstetric care, high rates of chronic disease before pregnancy, and limitations in data sources for measuring maternal mortality are major contributing factors to this upward trend.5 Improving the quality of care received before, during, and after pregnancy is an important modifiable target for intervention.3,6 Among low-income women, availability and access to care are additional concerns.

Low-income women have lower rates of preventive care. Barriers include lack of insurance, inability to afford care, no usual source of care, problems obtaining transportation, and poor experiences with the health care system.7 When low-income women do seek care, it may occur only after they realize that they are pregnant,8,9 and care may be of low quality. With limited access to prenatal and primary care, maternal complications amenable to prevention can result in hospitalizations and higher costs.10 Prior research also suggests that women with lower incomes may experience insurance-based discrimination during prenatal care, labor, and delivery.11,12

The 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) sought to address gaps in access to care by expanding insurance coverage for individuals with low incomes. The ACA also mandated coverage for preventive care, including prenatal care. Among states that expanded Medicaid, some researchers have found higher use of preventive care13,14 and increases in timely prenatal care15 among insured women, while others found no early impact.16 Evidence exists that women who have insurance in the preconception period are more likely to initiate prenatal care in the first trimester and have lower risk of adverse birth outcomes such as preterm births.9,17 However, few studies have examined the role of insurance in pregnancy-related health care use and outcomes in a Medicaid nonexpansion state.

The goal of this study was to compare health care use and adverse pregnancy outcomes by insurance status among women giving birth following the implementation of the ACA in 2014. We hypothesized that use of prenatal and postpartum care would be lower, while use of emergency care would be higher for women with Medicaid or no insurance compared to women with commercial insurance. We also hypothesized that adverse pregnancy outcomes would be higher for uninsured and Medicaid-insured women in comparison to commercially insured women. While prior research has examined variations in prenatal care use by income and insurance, the current study provides new evidence regarding differences in health care use between women with commercial insurance and those with Medicaid or no insurance during the prenatal and postpartum periods for pregnant women in a Medicaid nonexpansion state.

Materials and Methods

Setting and data sources

This study was conducted in North Carolina, one of 26 U.S. states that opted out of an expansion of Medicaid when the ACA was first approved and one of 14 states that still have not adopted the Medicaid expansion.18 In North Carolina, pregnant women are eligible for Medicaid coverage if their monthly family income is less than 196% of the federal poverty level ($3,961 a month for a family of four in 2015), and coverage is limited to conditions that affect the pregnancy.19 Nondisabled adults are eligible for coverage outside of pregnancy if they are parents or a caretaker of a dependent child and have a family income of less than $744 a month for a family of four. While only 11.4% of North Carolina's population was uninsured in 2014–2015, 18.5% of women aged 18–44 were uninsured and 18.2% of those with coverage had Medicaid (authors' analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Survey's 2014–2015 Annual Social and Economic Supplement, available at www.census.gov/cps/data/cpstablecreator.html).

We conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study using data from the Atrium Health electronic data warehouse, a centralized data repository that includes clinical and billing data from all hospitals and physician offices affiliated with the large vertically integrated health care system based in North Carolina. The electronic data warehouse contains a wide range of data on: (i) patient demographics such as age, race/ethnicity, gender, and health insurance status; (ii) health care encounters, including admission and discharge dates and diagnosis and procedure codes; and (iii) laboratory results. Data for this study came from six Atrium Health hospitals serving Mecklenburg County, a large metropolitan county with a population of over one million. These facilities include a Level I trauma center, which also serves as an academic medical center, a Level III trauma center, two community hospitals, and two specialty care hospitals with a combined total of 2,067 beds. Patient addresses were geocoded and linked by census tract to neighborhood poverty rates and high school graduation rates from the 2011 to 2015 American Community Survey (www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs). The Atrium Health Institutional Review Board approved this study and granted a waiver of informed consent.

Study sample

The study cohort consisted of 14,130 women aged 18 and older, who had a live birth during 2014–2015 and resided in Mecklenburg County. Women were excluded from the analysis for the following reasons: (i) gestational age at delivery missing or >42 weeks (n = 2,056); (ii) invalid address (n = 987); (iii) no documented prenatal care visits (n = 1,403 women who may have received care in other settings that our data did not capture); (iv) insurance status not classified as commercial, Medicaid, or uninsured (n = 55); (v) missing neighborhood-level data (n = 7); or (vi) missing body mass index (n = 9). The final analytic sample included 9,613 women. For women with more than one delivery during the study period, we included only the first delivery in our analysis.

Measures

We examined five measures of health care use: number of well-woman visits (in the two-year period before pregnancy), timing of prenatal care (care initiated in first, second, or third trimester), adequacy of prenatal care, six-week postpartum follow-up visit, and number of emergency department (ED) visits during pregnancy. International Classification of Disease (ICD) ninth and tenth revision codes were used to identify well-woman (V70.0, V72.31, V72.32, Z00.00, Z00.01, Z01.411, Z01.419, Z01.42), prenatal care (V22.1, V22.0, V23.9, Z34.xx), and postpartum (V24.2, Z39.2) visits. Adequacy of prenatal care was defined using the Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization (APNCU) index, which determines adequacy of prenatal care based on timely initiation of care and percentage of expected visits completed.20 The four categories of care range from inadequate to adequate plus. We counted all ED visits (for any reason) that occurred between the time of conception and delivery as determined by gestational age at delivery. We examined the following adverse pregnancy outcomes that are potential targets for prevention and quality improvement21–26: low birth weight (based on birth weight <2,500 g), preterm birth (based on gestational age <37 weeks), preeclampsia (ICD-9: 642.4x, 642.5x, 642.6x, 642.7x; ICD-10: O14.xx), and gestational diabetes (ICD-9: 648.8; ICD-10: O24.xx).

The primary independent variable was insurance status, which we classified as Medicaid, uninsured, or commercial, based on the primary payor source at delivery.

Statistical analysis

Differences in health care use and adverse outcomes by insurance status were initially assessed using chi-square statistics. We then used multivariate regression models to estimate the adjusted odds or adjusted rate of each outcome by insurance status. Logistic regression models were used for binary outcomes, while zero-inflated negative binomial models were used for count outcomes. These models were adjusted for the following covariates previously shown to be associated with health care use and adverse pregnancy outcomes: age at delivery, race/ethnicity, location of residence, preexisting hypertension, preexisting diabetes, overweight or obesity prepregnancy, neighborhood poverty rate, and neighborhood high school education rate. Timeliness of prenatal care was included in initial models for adverse birth outcomes and later excluded because of collinearity with insurance status. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 6.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All tests were two sided, and p-value <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Table 1 presents overall demographics of the sample and bivariate associations with insurance status at delivery. Of the 9,613 women, 4,441 (46.2%) had commercial insurance, 4,990 (51.9%) had Medicaid, and 182 (1.9%) were uninsured. There were more uninsured women among those with births in 2014 than among those with births in 2015. Most women were aged 25–34 and lived within the Charlotte city limits. Compared to commercially insured women, women with Medicaid or no insurance were younger, less likely to be non-Hispanic White, more likely to have comorbid diabetes, and lived in neighborhoods with higher average rates of poverty and less than high school education.

Table 1.

Distribution of Characteristics of Women Living in Mecklenburg County Who Gave Birth Within Atrium Health, by Insurance Status (2014–2015)

| All women | Commercial | Medicaid | Uninsured | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 9,613 | 4,441 | 4,990 | 182 | |

| Delivery Year, n (%) | 0.010 | ||||

| 2014 | 4,740 (49.3) | 2,185 (49.2) | 2,445 (49.0) | 110 (60.4) | |

| 2015 | 4,873 (50.7) | 2,256 (50.8) | 2,545 (51.0) | 72 (39.6) | |

| Age at delivery, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| 18–24 | 2,088 (21.7) | 409 (9.2) | 1,640 (32.9) | 39 (21.4) | |

| 25–34 | 5,698 (59.3) | 2,966 (66.8) | 2,621 (52.5) | 111 (61.0) | |

| 35+ | 1,827 (19.0) | 1,066 (24.0) | 729 (14.6) | 32 (17.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Hispanic | 2,881 (30.0) | 327 (7.4) | 2,465 (49.4) | 89 (48.9) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2,593 (27.0) | 966 (21.8) | 1,599 (32.0) | 28 (15.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2,709 (28.2) | 2,315 (52.1) | 371 (7.4) | 23 (12.6) | |

| Other | 1,430 (14.9) | 833 (18.8) | 555 (11.1) | 42 (23.1) | |

| Location of residence, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Charlotte | 8,849 (92.1) | 3,911 (88.1) | 4,764 (95.5) | 174 (95.6) | |

| Other Mecklenburg County | 864 (9.0) | 630 (14.2) | 226 (4.5) | 8 (4.4) | |

| Medical comorbidity, n (%) | |||||

| Hypertension | 269 (2.8) | 98 (2.2) | 168 (3.4) | 3 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 120 (1.2) | 42 (0.9) | 75 (1.5) | 3 (1.6) | 0.046 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | <0.001 | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 94 (1.0) | 60 (1.4) | 34 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 3,586 (37.3) | 2,088 (47.0) | 1,450 (29.1) | 48 (26.4) | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 2,897 (30.1) | 1,207 (27.2) | 1,629 (32.6) | 61 (33.5) | |

| Obese (30–39.9) | 2,400 (25.0) | 830 (18.7) | 1,508 (30.2) | 62 (34.1) | |

| Severe obesity (≥40) | 636 (6.6) | 256 (5.8) | 369 (7.4) | 11 (6.0) | |

| Neighborhood poverty rate, mean (SD) | 16.6 (13.2) | 9.4 (9.5) | 22.9 (12.8) | 18.4 (14.2) | <0.001 |

| Neighborhood rate of education less than high school, mean (SD) | 14.8 (11.8) | 8.3 (8.1) | 20.6 (11.4) | 15.8 (12.5) | <0.001 |

Chi-square test or t-test of differences between characteristics by insurance status.

SD, standard deviation.

Health care use outcomes are presented in Table 2. Compared to women with commercial insurance, women classified as Medicaid-insured or uninsured at delivery had a lower mean number of well-woman visits in the two years before giving birth and a higher mean number of ED visits during pregnancy. Compared to women with Medicaid or no insurance, women with commercial insurance were more likely to initiate prenatal care in the first trimester (commercial: 57.9%; Medicaid: 28.6%; uninsured: 20.9%, p < 0.01), to have prenatal care that was classified as adequate plus (commercial: 38.7%; Medicaid: 23.5%; uninsured: 12.1%, p < 0.01), and to have a postpartum checkup within six weeks of delivery (commercial: 90.0%; Medicaid: 49.2%; uninsured: 41.2%, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Distribution of Health Care Use by Insurance Status, Women Living in Mecklenburg County Who Gave Birth Within Atrium Health (2014–2015)

| All women | Commercial | Medicaid | Uninsured | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 9,613 | 4,441 | 4,990 | 182 | |

| Well-woman visit prior pregnancy (up to 2 years prior), mean (SD) | 0.4 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0.1 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| ED visits during pregnancy, mean (SD) | 1.6 (3.7) | 0.6 (1.9) | 2.5 (4.6) | 1.3 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| Timing of first prenatal care visit, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| 1st trimester (≤12 weeks) | 4,038 (42.0) | 2,573 (57.9) | 1,427 (28.6) | 38 (20.9) | |

| 2nd trimester (13–24 weeks) | 3,645 (37.9) | 1,191 (26.8) | 2,379 (47.7) | 75 (41.2) | |

| 3rd trimester (>24 weeks) | 1,930 (20.1) | 677 (15.2) | 1,184 (23.7) | 69 (37.9) | |

| Number of prenatal care visits, mean (SD) | 8.3 (3.9) | 9.3 (4.3) | 7.5 (3.3) | 6.1 (3.2) | <0.001 |

| APNCU index, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Inadequate | 2,018 (21.0) | 865 (19.5) | 1,073 (21.5) | 80 (44.0) | |

| Intermediate | 1,373 (14.3) | 432 (9.7) | 904 (18.1) | 37 (20.3) | |

| Adequate | 3,307 (34.4) | 1,426 (32.1) | 1,838 (36.8) | 43 (23.6) | |

| Adequate plus | 2,915 (30.3) | 1,718 (38.7) | 1,175 (23.5) | 22 (12.1) | |

| Postpartum checkup, n (%) | 6,530 (67.9) | 3,998 (90.0) | 2,457 (49.2) | 75 (41.2) | <0.001 |

Chi-square test or t-test of differences in health care use by insurance status.

ED, emergency department.

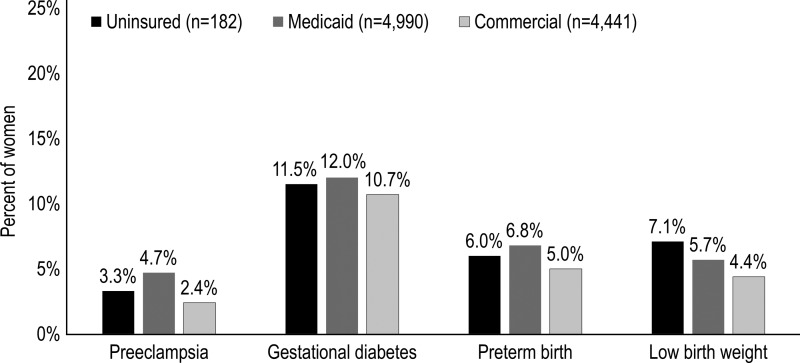

As shown in Figure 1, the prevalence of adverse birth outcomes also varied significantly by insurance status. Women with Medicaid or no insurance had higher unadjusted rates of preterm birth, preeclampsia, and low birth weight compared to women with commercial insurance.

FIG. 1.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes by insurance status, women living in Mecklenburg County who gave birth within Atrium Health (2014–2015). Unadjusted p-value <0.05 for all outcomes from chi-square tests.

After adjustment for patient characteristics, many of the relationships between health care use and insurance status remained (Table 3). Medicaid-insured women had a rate of well-woman visits that was one-fourth that of women classified as commercially insured (rate ratio [RR] 0.25, 95% CI 0.23–0.28) and a nearly three times greater rate of ED visits during pregnancy (RR 2.93, 95% CI 2.64–3.25). Results for uninsured women were similar. Women with Medicaid insurance at delivery also had 18% greater odds of not receiving prenatal care in the first trimester, while uninsured women had 84% greater odds compared to women with commercial insurance (Medicaid odds ratio [OR] 1.18, 95% CI 1.03–1.34; uninsured OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.45–2.35). Uninsured women also had 52% lower odds of adequate prenatal care (OR = 0.48, 95% CI 0.39–0.60). Among the adverse pregnancy outcomes examined, no differences by insurance status remained statistically significant after adjustment for patient characteristics (Table 4). Factors associated with higher odds of adverse pregnancy outcomes included older maternal age (age 35+), preexisting hypertension, preexisting diabetes, and race/ethnicity.

Table 3.

Association Between Insurance Status and Health Care Use, Women Living in Mecklenburg County Who Gave Birth Within Atrium Health (2014–2015)*

| Well-woman visits |

ED visits |

No first trimester prenatal care |

Adequate prenatal care |

6-week postpartum follow-up |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Insurance | |||||

| Commercial | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medicaid | 0.25 (0.23–0.28) | 2.93 (2.64–3.25) | 1.18 (1.03–1.34) | 1.35 (1.20–1.51) | 0.65 (0.58–0.74) |

| Uninsured | 0.23 (0.15–0.35) | 2.31 (1.68–3.17) | 1.84 (1.45–2.35) | 0.48 (0.39–0.60) | 0.42 (0.34–0.51) |

| Age at delivery | |||||

| 18–24 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 25–34 | 1.61 (1.42–1.81) | 0.67 (0.60–0.74) | 0.89 (0.84–0.95) | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) | 1.10 (1.03–1.18) |

| 35+ | 1.88 (1.65–2.13) | 0.51 (0.45–0.59) | 0.94 (0.87–1.01) | 0.95 (0.88–1.03) | 1.04 (0.95–1.13) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.54 (0.47–0.61) | 0.79 (0.70–0.90) | 1.03 (0.94–1.12) | 0.77 (0.71–0.83) | 0.70 (0.64–0.76) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.99 (0.91–1.08) | 2.08 (1.83–2.36) | 1.03 (0.96–1.12) | 1.07 (0.99–1.16) | 0.95 (0.87–1.04) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Other | 0.64 (0.58–0.71) | 0.72 (0.62–0.84) | 1.42 (1.30–1.56) | 0.89 (0.82–0.98) | 1.05 (0.95–1.17) |

| Location of residence | |||||

| Charlotte | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Other Mecklenburg County | 1.05 (0.96–1.15) | 0.82 (0.69–0.97) | 1.00 (0.92–1.08) | 1.03 (0.95–1.12) | 1.05 (0.95–1.17) |

| Medical comorbidity | |||||

| Hypertension | 1.14 (0.94–1.38) | 1.85 (1.48–2.32) | 0.83 (0.73–0.94) | 1.21 (1.06–1.39) | 1.10 (0.95–1.27) |

| Diabetes | 1.19 (0.89–1.57) | 2.16 (1.54–3.02) | 0.90 (0.74–1.09) | 0.69 (0.57–0.83) | 0.90 (0.73–1.11) |

| Body mass index (BMI) | |||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 0.96 (0.74–1.26) | 1.05 (0.68–1.62) | 1.04 (0.74–1.47) | 1.14 (0.79–1.64) | 1.32 (0.84–2.08) |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 0.85 (0.78–0.92) | 1.14 (1.02–1.26) | 1.05 (0.94–1.18) | 0.93 (0.83–1.05) | 0.97 (0.84–1.11) |

| Obese (30–39.9) | 0.89 (0.81–0.97) | 1.23 (1.11–1.38) | 1.16 (1.03–1.31) | 0.82 (0.72–0.92) | 0.95 (0.83–1.10) |

| Severe obesity (≥40) | 0.92 (0.80–1.05) | 1.18 (0.99–1.40) | 0.86 (0.73–1.01) | 1.07 (0.91–1.26) | 0.81 (0.67–0.97) |

| Neighborhood poverty rate | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) |

| Neighborhood percent with less than high school education | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) |

Results from negative binomial or logistic regression models.

CI, confidence interval; RR, rate ratio; OR, odds ratio.

Table 4.

Association Between Insurance Status and Birth Outcomes, Women Living in Mecklenburg County Who Gave Birth Within Atrium Health (2014–2015)*

| Preterm birth |

Preeclampsia |

Gestational diabetes |

Low birth weight |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Insurance | ||||

| Commercial | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medicaid | 1.06 (0.84–1.33) | 1.25 (0.92–1.71) | 1.07 (0.90–1.28) | 0.92 (0.74–1.15) |

| Uninsured | 1.04 (0.69–1.58) | 0.93 (0.53–1.65) | 0.89 (0.64–1.22) | 1.35 (0.91–1.98) |

| Age at delivery | ||||

| 18–24 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 25–34 | 0.85 (0.76–0.95) | 0.78 (0.68–0.91) | 1.03 (0.93–1.13) | 0.86 (0.76–0.97) |

| 35+ | 1.22 (1.06–1.41) | 1.26 (1.05–1.51) | 2.10 (1.88–2.34) | 1.24 (1.07–1.45) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.97 (0.83–1.15) | 1.21 (0.99–1.49) | 1.22 (1.08–1.38) | 0.75 (0.62–0.90) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.20 (1.03–1.39) | 1.07 (0.88–1.30) | 0.77 (0.68–0.87) | 1.44 (1.23–1.67) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Other | 0.94 (0.77–1.14) | 1.00 (0.77–1.30) | 1.32 (1.16–1.50) | 1.27 (1.05–1.53) |

| Location of residence | ||||

| Charlotte | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Other Mecklenburg County | 1.04 (0.88–1.22) | 0.84 (0.65–1.09) | 1.05 (0.94–1.19) | 0.96 (0.79–1.16) |

| Medical comorbidity | ||||

| Hypertension | 1.66 (1.39–1.97) | 3.22 (2.75–3.77) | 1.41 (1.21–1.64) | 1.60 (1.33–1.93) |

| Diabetes | 1.18 (0.88–1.57) | 1.35 (1.01–1.80) | 1.67 (1.37–2.04) | 1.05 (0.76–1.47) |

| Obesity | ||||

| Underweight (BMI <18.5) | 1.24 (0.66–2.31) | 0.73 (0.24–2.29) | 1.04 (0.61–1.77) | 1.32 (0.70–2.47) |

| Normal (BMI 18.5–24.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9) | 0.89 (0.72–1.10) | 0.93 (0.66–1.32) | 0.92 (0.77–1.09) | 0.78 (0.63–0.98) |

| Obese (BMI 30–39.9) | 0.91 (0.73–1.13) | 1.31 (0.94–1.83) | 1.30 (1.10–1.55) | 0.77 (0.62–0.97) |

| Severe obesity (BMI ≥40) | 1.21 (0.92–1.60) | 1.46 (0.98–2.19) | 1.16 (0.92–1.47) | 1.59 (1.22–2.08) |

| Neighborhood poverty rate | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) |

| Neighborhood percent with less than high school education | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) |

Results from logistic regression models.

BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

We found that women with Medicaid or no insurance at delivery were less likely to use preventive care and more likely to use emergency care than women with commercial insurance. While we also found that preterm birth, low birth weight, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes were higher among Medicaid-insured and uninsured women compared to women with commercial insurance, these differences did not remain statistically significant after adjusting for demographic, clinical, and neighborhood factors. Our results add to limited research regarding insurance status and health care utilization before and during and immediately after pregnancy in nonexpansion states.27 Our findings of low rates of preventive care and high rates of ED use among pregnant women highlight important opportunities for improving care for women with low incomes.

Our finding that women with Medicaid at delivery were more likely to enter prenatal care late is consistent with prior research.9,28 We also found that these women were less likely to have well-woman visits before pregnancy and postpartum visits following delivery. Preconception care and postpartum care are thought to be important time points to optimize women's health and have been suggested as important foci for reducing the rising rates of maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States.29,30 Mothers insured by Medicaid in our study had 1.5 times higher odds of nonattendance at the six-week postpartum visit than women who were commercially insured, which is consistent with findings from New York31 and California.32 Women insured by Medicaid in our study were largely Hispanic (49.4%) or non-Hispanic Black (32.0%).

Previous reports suggest that women of color are at higher risk of postpartum care nonattendance than White women although reasons why are not entirely clear.31,33,34 While insurance provides potential access to care, low-income women have shared that they desire flexible timing and convenient location options for postpartum care, which are not always available.35

Our results regarding higher use of ED visits among women who did not have commercial insurance confirm those of a smaller study in a sample of 233 postpartum women in 2012.36 Kilfoyle et al.36 found that women with public insurance were five times more likely to use the ED for nonurgent reasons than women with private insurance. Pregnant women may visit the ED for nonurgent reasons because of uncertainty regarding symptoms, a lack of consistent medical care, or psychosocial issues such as substance abuse.36,37 The nearly threefold higher rate of ED visits during pregnancy among the low income women in our study highlights a need for innovative strategies to promote access to lower care cost options, provide education on symptom management, and address psychosocial issues that may contribute to greater ED use. Centering Pregnancy and Nurse Family Partnerships are two promising approaches for improving health care use and perinatal outcomes among low-income and minority women, which involve peer support and home visitation.38

None of the four adverse pregnancy outcomes that we examined remained significantly associated with insurance status in adjusted analyses. However, previous research has found an association between Medicaid coverage and adverse birth outcomes. A prior study of women with pregnancy-related hypertension found that those with Medicaid at delivery were more likely to experience preterm birth and eclampsia than those with private insurance.39 Another study using a large sample of women from 32 states found that women who were uninsured before conception had 20% higher risk of preterm birth than women who were insured.17 Differences between these findings and those in our study may reflect differences in the populations studied, differences in how insurance status was determined, or the size of our sample. Our finding that older maternal age (age 35+) and preexisting hypertension were associated with higher odds of all outcomes examined (preterm birth, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and low birth weight) aligns with prior research40,41 and suggests these subgroups as potential targets for interventions.

Our findings provide support for increasing insurance coverage as one strategy for improving access to preventive care for low-income women. In the absence of universal health care or an expansion of Medicaid, some states have used Medicaid Family Planning Waivers, which provide coverage for contraception and education and testing for sexually transmitted diseases, to increase access to care for reproductive-aged women.42 While useful for preventing pregnancy, these programs are limited in that they do not provide coverage for the treatment or management of chronic diseases or related risk factors. Texas has used a combination of waivers and state funds for their Healthy Texas Women program, which provides comprehensive health care, including pregnancy tests, contraception, and screening and treatment for cholesterol, diabetes, and hypertension for women aged 15–44.43 However, the program is not well known, and attempts to exclude providers like Planned Parenthood have yielded adverse results.43 Opportunity exists to build on these approaches by leveraging existing provider networks to offer more comprehensive care for women.

In addition to expanding coverage, women need education and outreach regarding the services available to them. A 2016 survey of U.S. women aged 18–44 found that women were more likely to use preventive care when they had greater knowledge of covered services.14 Addressing potential language and cultural barriers is important for engaging Hispanic/Latina women and other groups.31,44 While examining the interplay between race/ethnicity and health care use was not the focus of the current study, we found that Hispanic ethnicity was associated with lower rates of well-woman visits before pregnancy, lower odds of adequate prenatal care, and lower odds of six-week postpartum follow-up compared to Whites (Table 3). We also found that Black race was associated with higher rates of ED visits during pregnancy. Policies designed to improve access to care should consider the needs of women of color and address institutional and community-level factors (e.g., discrimination and biases) that may impede care.

Limitations

Data used in this study were from a single public not-for-profit health care system. As such, we were unable to capture care received from unaffiliated providers. Because delivery privileges are limited to affiliated providers, we expect that deliveries to patients who received prenatal care from unaffiliated providers would be limited to emergencies. Future studies using claims data and studies that capture care received from free clinics, community health centers, and nontraditional sources of care may provide a more comprehensive look at health care use. Our analysis of ED visits did not distinguish between urgent and nonurgent visits. Additional research that examines ED visit urgency would be helpful for tailoring interventions. To account for changes in medical coding in 2015, we used both ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes to identify preeclampsia and gestational diabetes. Potential coding errors in the electronic medical record should be nondifferential between the groups of patients studied. We used insurance status at delivery to classify patients and did not account for changes in coverage before or after delivery. Approximately 65% of women using Medicaid for delivery are uninsured at some point during the nine months before delivery and 55% are uninsured at some point during the six months postdelivery.45 We were unable to determine the parity of patients in our sample. Therefore, our models did not adjust for parity. Finally, results are based on data from a single metropolitan region in a Medicaid nonexpansion state in the southeastern United States and may not be generalizable to other geographic regions.

Implications for policy and/or practice

Low rates of preventive care and high rates of ED use among pregnant women with Medicaid and those with no insurance highlight important opportunities for improving care for low-income women. Health care providers can address gaps in the use of preventive care among low income women by providing education about the need for preventive care, including postpartum care, and using home-based or virtual care delivery models that overcome structural barriers to access. There is an urgent need to improve potential and realized access to care.

Conclusions

Compared to privately insured women, women who have Medicaid or no insurance at delivery experience barriers to preventive care before, during, and after pregnancy. Policymakers in states that did not expand Medicaid should consider ways to expand insurance coverage for women in addition to other methods to improve access to care.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from AcademyHealth and the March of Dimes. Y.J.T. was funded, in part, by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (Contract No. L60 MD009805). The funders did not participate in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the article, or the decision to submit this article for publication.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Kassebaum NJ, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1775–1812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe Maternal Morbidity in the United States. Atlanta, Georgia: Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2019. Available at: www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/severematernalmorbidity.html Accessed May7, 2019

- 3. Howell EA, Zeitlin J. Improving hospital quality to reduce disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Semin Perinatol 2017;41:266–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moaddab A, Dildy GA, Brown HL, et al. Health care disparity and pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2005–2014. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Agrawal P. Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States of America. Bull World Health Organ 2015;93:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lu MC, Highsmith K, Cruz D de la, Atrash HK. Putting the “M” Back in the Maternal and Child Health Bureau: Reducing Maternal Mortality and Morbidity. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:1435–1439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Salganicoff A, Ranji U, Beamesderfer A, Kurani N. Women and Health Care in the Early Years of the Affordable Care Act: Findings from the 2013 Kaiser Women's Health Survey. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014:49 Available at: www.kff.org/report-section/women-and-health-care-in-the-early-years-of-the-aca-key-findings-from-the-2013-kaiser-womens-health-survey-methods Accessed April26, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Breathett K, Filley J, Pandey M, Rai N, Peterson PN. Trends in early prenatal care among women with pre-existing diabetes: Have income disparities changed? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27:93–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Egerter S, Braveman P, Marchi K. Timing of insurance coverage and use of prenatal care among low-income women. Am J Public Health 2002;92:423–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Laditka S, Laditka J, Mastanduno M, Lauria M, Foster T. Potentially avoidable maternity complications: An indicator of access to prenatal and primary care during pregnancy. Women Health 2005;41:1–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Salm Ward TC, Mazul M, Ngui EM, Bridgewater FD, Harley AE. “You learn to go last”: Perceptions of prenatal care experiences among African-American women with limited incomes. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:1753–1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thorburn S, De Marco M. Insurance-based discrimination during prenatal care, labor, and delivery: Perceptions of Oregon mothers. Matern Child Health J 2010;14:875–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Daw JR, Sommers BD. Association of the affordable care act dependent coverage provision with prenatal care use and birth outcomes. JAMA 2018;319:579–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sawyer AN, Kwitowski MA, Benotsch EG. Are you covered? associations between patient protection and affordable care act knowledge and preventive reproductive service use. Am J Health Promot 2018;32:906–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Adams EK, Dunlop AL, Strahan AE, Joski P, Applegate M, Sierra E. Prepregnancy insurance and timely prenatal care for medicaid births: Before and after the affordable care act in Ohio. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2019;28:654–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arora P, Desai K. Impact of Affordable Care Act coverage expansion on women's reproductive preventive services in the United States. Prev Med 2016;89:224–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clapp MA, James KE, Kaimal AJ. Preconception insurance and initiation of prenatal care. J Perinatol 2019;39:300–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision.; 2019. Available at: www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act Accessed April22, 2019

- 19. NC Medicaid Division of Health Benefits. Medicaid Income and Resources Requirements. Available at: https://medicaid.ncdhhs.gov/medicaid/get-started/learn-if-you-are-eligible-medicaid-or-health-choice/medicaid-income-and Accessed April22, 2019

- 20. Kotelchuck M. An evaluation of the Kessner Adequacy of Prenatal Care Index and a proposed adequacy of prenatal care utilization index. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1414–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brown HL, Chireau MV, Jallah Y, Howard D. The “Hispanic paradox”: An investigation of racial disparity in pregnancy outcomes at a tertiary care medical center. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;197:197..e1–7; discussion 197.e7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Maternal, Infant, and Child Health | Healthy People 2020. HealthyPeople.gov Available at: www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives Published August 24, 2018. Accessed August23, 2018

- 23. Phipps E, Prasanna D, Brima W, Jim B. Preeclampsia: Updates in Pathogenesis, Definitions, and Guidelines. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:1102–1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tolcher MC, Chu DM, Hollier LM, et al. Impact of USPSTF recommendations for aspirin for prevention of recurrent preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:365..e1–365.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bardenheier BH, Imperatore G, Gilboa SM, et al. Trends in Gestational Diabetes Among Hospital Deliveries in 19 U.S. States. Am J Prev Med 2015;49:12–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilson-Mitchell K. Increasing access to prenatal care: Disease prevention and sound business practice. Health Care Women Int 2014;35:120–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Atkins DN, Held ML, Lindley LC. The impact of expanded health insurance coverage for unauthorized pregnant women on prenatal care utilization. Public Health Nurs 2018;35:459–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Braveman P, Marchi K, Egerter S, et al. Poverty, near-poverty, and hardship around the time of pregnancy. Matern Child Health J 2010;14:20–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Howell EA, Brown H, Brumley J, et al. Reduction of peripartum racial and ethnic disparities: A conceptual framework and maternal safety consensus bundle. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:770–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. The Council on Patient Safety in Women's Health Care. Postpartum Care Basics for Maternal Safety From Birth to the Comprehensive Postpartum Visit. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2017. Available at: https://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/patient-safety-bundles/postpartum-care-basics-1 Accessed May7, 2019

- 31. Wilcox A, Levi EE, Garrett JM. Predictors of non-attendance to the postpartum follow-up visit. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:22–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. DiBari JN, Yu SM, Chao SM, Lu MC. Use of postpartum care: Predictors and barriers. J Pregnancy 2014;2014:530769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rankin KM, Haider S, Caskey R, Chakraborty A, Roesch P, Handler A. Healthcare utilization in the postpartum period among illinois women with medicaid paid claims for delivery, 2009–2010. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:144–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thiel de Bocanegra H, Braughton M, Bradsberry M, Howell M, Logan J, Schwarz EB. Racial and ethnic disparities in postpartum care and contraception in California's Medicaid program. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:47..e1–47.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Henderson V, Stumbras K, Caskey R, Haider S, Rankin K, Handler A. Understanding Factors Associated with Postpartum Visit Attendance and Contraception Choices: Listening to Low-Income Postpartum Women and Health Care Providers. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:132–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kilfoyle KA, Vrees R, Raker CA, Matteson KA. Nonurgent and urgent emergency department use during pregnancy: An observational study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216:181..e1–181.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Malik S, Kothari C, MacCallum C, Liepman M, Tareen S, Rhodes KV. Emergency department use in the perinatal period: An opportunity for early intervention. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:835–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Krans EE, Davis MM. Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns: Implications for prenatal care delivery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2014;26:511–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Greiner KS, Speranza RJ, Rincón M, Beeraka SS, Burwick RM. Association between insurance type and pregnancy outcomes in women diagnosed with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1519544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bramham K, Parnell B, Nelson-Piercy C, Seed PT, Poston L, Chappell LC. Chronic hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014;348:g2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Carolan M, Frankowska D. Advanced maternal age and adverse perinatal outcome: A review of the evidence. Midwifery 2011;27:793–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ranji U, Bair Y, 2016. Medicaid and Family Planning: Background and Implications of the ACA - Medicaid Family Planning Policy. The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation; April 2015. Available at: www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-and-family-planning-medicaid-family-planning-policy Accessed March27, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stevenson AJ, Flores-Vazquez IM, Allgeyer RL, Schenkkan P, Potter JE. Effect of removal of planned parenthood from the Texas Women's Health Program. N Engl J Med 2016;374:853–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Coffman MJ, de Hernandez BU, Smith HA, et al. Using CBPR to decrease health disparities in a suburban latino neighborhood. Hisp Health Care Int 2017;15:121–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Daw JR, Hatfield LA, Swartz K, Sommers BD. Women in the United States experience high rates of coverage ‘Churn’ In Months Before And After Childbirth. Health Affairs 2017;36:598–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]