Abstract

In this study, the influence of age on effectiveness of regenerative repair for the treatment of volumetric muscle loss (VML) injury was explored. Tibialis anterior (TA) VML injuries were repaired in both 3- and 18-month-old animal models (Fischer 344 rat) using allogeneic decellularized skeletal muscle (DSM) scaffolds supplemented with autologous minced muscle (MM) paste. Within the 3-month animal group, TA peak contractile force was significantly improved (79% of normal) in response to DSM+MM repair. However, within the 18-month animal group, muscle force following repair (57% of normal) was not significantly different from unrepaired VML controls (59% of normal). Within the 3-month animal group, repair with DSM+MM generally reduced scarring at the site of VML repair, whereas scarring and a loss of contractile tissue was notable at the site of repair within the 18-month group. Within 3-month animals, expression of myogenic genes (MyoD, MyoG), extracellular matrix genes (Col I, Col III, TGF-β), and key wound healing genes (TNF-α and IL-1β) were increased. Alternatively, expression was unchanged across all genes examined within the 18-month animal group. The findings suggest that a decline in regenerative capacity and increased fibrosis with age may present an obstacle to regenerative medicine strategies targeting VML injury.

Impact Statement

This study compared the recovery following volumetric muscle loss (VML) injury repair using a combination of minced muscle paste and decellularized muscle extracellular matrix carrier in both a younger (3 months) and older (18 months) rat population. Currently, VML repair research is being conducted with the young patient population in mind, but our group is the first to look at the effects of age on the efficacy of VML repair. Our findings highlight the importance of considering age-related changes in response to VML when developing repair strategies targeting an elderly patient population.

Keywords: orthopedics, musculoskeletal, animal model, tibialis anterior, VML

Introduction

Volumetric muscle loss (VML) injury is commonly characterized as the bulk loss (>20%) of muscle tissue resulting in incomplete or aberrant muscle regeneration. Current soft tissue repair techniques and traditional rehabilitation have not been able to reverse the pathological changes that occur following VML injury. To reverse the pathobiology of VML injury, the use of regenerative medicine strategies to recapitulate the cellular and structural cues during regeneration have shown efficacy in animal models.1–8 Among these strategies, our group has demonstrated that the implantation of a decellularized skeletal muscle scaffold (DSM) codelivered with a minced muscle (MM) autograft paste is capable of recovering half of the contractile force lost to VML injury.9 Other groups have shown similar improvements in muscle recovery using various combinations of scaffolds with and without myogenic cell sources.10–14 When taken as a whole, our findings and others suggest that the use of regenerative medicine may have therapeutic potential as a treatment for VML injury.

Traditionally, battlefield injuries to the extremities have been the key clinical target driving the development of VML repair strategies.15–17 Potentially motivated by this intended patient population, the preclinical examination of regenerative medicine strategies for VML repair has been limited thus far to young animal models.3,8,18,19 Less recognized are traumatic muscle injuries within the civilian population,20 which are more likely to occur across a broad age group. It is reasonable to speculate that the age of the VML injured patient could influence the effectiveness of any VML treatment. Specifically, the decrease in myogenic capacity that occurs with age could present a significant hurdle to muscle regeneration in an older patient population.21,22 Yet it remains unclear whether the VML findings observed using younger animal models will be predictive of clinical performance in older patients. We suggest that an improved understanding of the relationship between age and VML treatment performance would provide valuable insights that could help elucidate the appropriateness of current VML repair strategies for a broader patient population.

As a first step toward reaching this level of understanding, our group has developed an aged rat VML model and demonstrated that age impacts muscle healing following VML injury.23 Specifically, our findings suggested that extracellular matrix (ECM) gene expression and protein deposition is significantly altered following VML injury in an aged model (18 months), resulting in a more fibrotic environment when compared with nonaged controls (3 months). While changes in muscle wound healing with age were identified and appeared consistent with findings in humans,24 the study did not examine whether these age-related differences in VML healing would in turn influence the response to regenerative repair. The purpose of this study was to examine whether the improved functional outcomes that have been observed following VML repair in nonaged models are sensitive to aging. Specifically, this study was designed to test the hypothesis that age will dampen the beneficial effects of regenerative treatment. This study presents those performance results along with comparisons to nonaged animal model findings.

Materials and Methods

DSM scaffold preparation

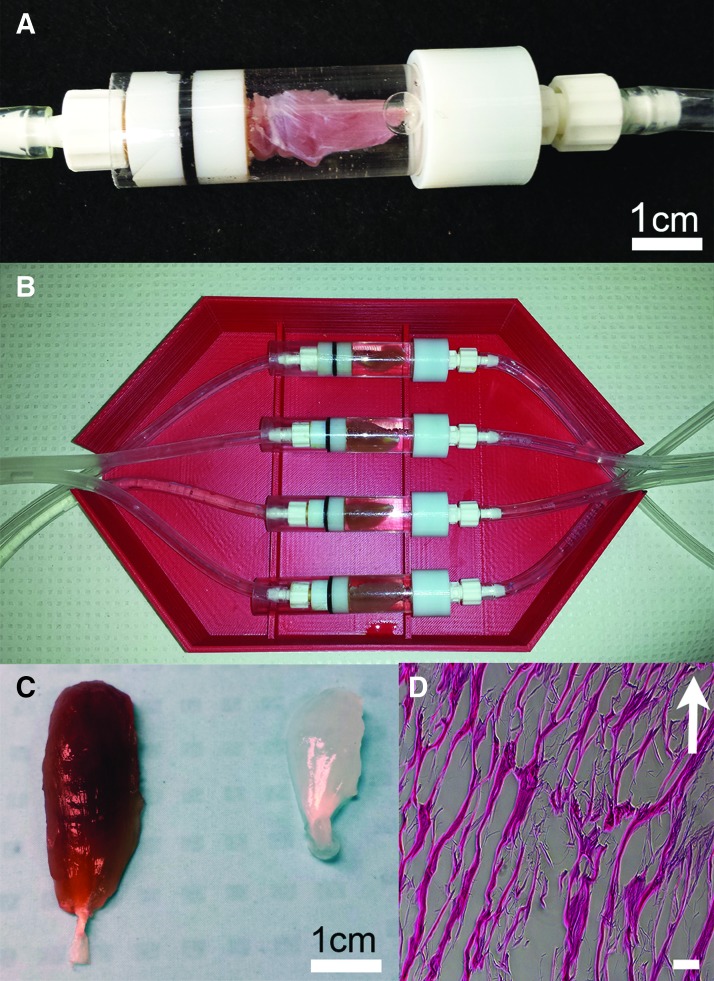

To prepare DSM samples for implantation, whole tibialis anterior (TA) muscle was decellularized using a previously reported25 infusion system (Fig. 1). TA muscles were harvested from rats (Sprague Dawley) that had been euthanized at the completion of an unrelated study. The TA samples were infused overnight (∼12 h) with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at a flow rate of 5 mL/h. Following infusion, samples were incubated overnight in a DNAse solution (1 kU/mL DNAse in 10 mM Tris-HCL buffer; 2.5 mM MgCl2+0.5 mM CaCl2) and then incubated (8 h) in a 1 × penicillin/streptomycin solution to reduce the risk of infection. Samples were rinsed thoroughly (a total of six 24-h wash steps) in phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) between each preparation step. Following completion of decellularization, the DNA concentration of representative DSM implants (n = 4) was measured with the aid of a commercial quantification kit (Qubit; Fisher Scientific). DSM implants were lyophilized and stored at −20°C until utilized for implantation.

FIG. 1.

Whole TA muscles were decellularized using an infusion bioreactor. During decellularization, sodium dodecyl sulfate solution was delivered to the mid-belly region of the TA muscle through a hypodermic needle and syringe pump (A). The bioreactor was designed to accommodate four side-by-side decellularization units each capable of accommodating a single muscle tissue sample (B). Representative whole TA muscle appearance before and following infusion decellularization treatment (C left and right), illustrates the appearance of the DSM scaffolds following removal of intracellular myoglobin. Infusion prepared DSM scaffolds, when viewed in thin section (scale bar = 100 μm) with H&E staining, retained the aligned network structure of native muscle ECM (D). Arrow indicates approximate direction of muscle contraction. DSM, decellularized skeletal muscle; ECM, extracellular matrix; TA, tibialis anterior; VML, volumetric muscle loss. Color images are available online.

VML injury and MM

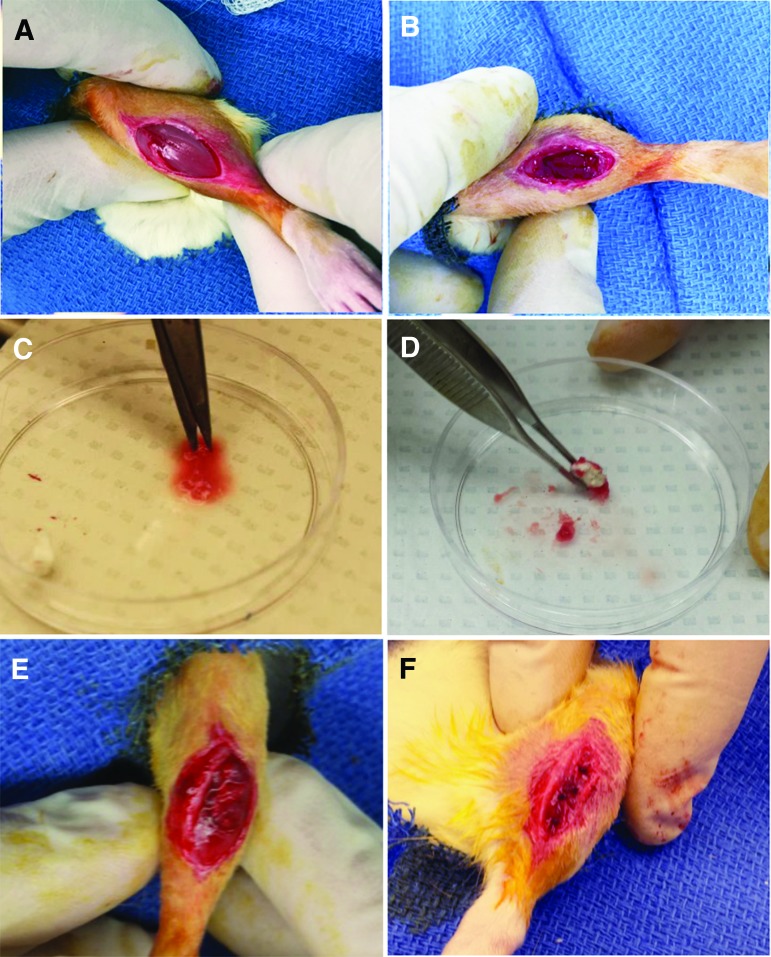

In vivo VML studies were performed using male Fischer 344 rats with ages of either 3 months (20% of the median lifespan) or 18 months (75% of their median lifespan). The 3-month rats were purchased commercially from Envigo (Indianapolis, IN) and the 18-month rats were obtained through the National Institute on Aging (Bethesda, MD). Surgical procedures and implant preparation methods were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the University of Arkansas IACUC (protocol no. 14044) and as described previously.9 Three- and 18-month animals were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups (n = 7–8/age/treatment group): unrepaired VML defect (VML), or VML defect repaired using a DSM scaffold supplemented with autogenic MM. VML defects (8 × 3 mm) were created in the TA using a biopsy punch (Fig. 2A, B). Twenty-five percent of the biopsied muscle was retained for use as MM (Fig. 2C). DSM scaffolds were fully coated in the MM paste and then implanted into the VML defect site (Fig. 2D–F). All contralateral limbs were left untreated to serve as comparative normal controls. All animals were housed for a 12-week recovery period.

FIG. 2.

Surgical VML and repair procedure. The surgical site was cleaned and disinfected and a 1–2-cm incision was made to expose the underlying TA muscle (A). A 8 mm biopsy punch was used to create a VML injury to a depth of 3 mm. Approximately 20% of the TA muscle was excised (B). MM autografts were prepared using 25% (by mass) of the removed muscle plug. The muscle tissue was minced using a scalpel and scissors (C). The resulting MM paste was used to coat a DSM scaffold before implantation into the defect site (D). The MM-coated DSM scaffold was packed into the defect with scaffold alignment oriented to direction of muscle contraction (E). The surgical site was closed using both deep and surface sutures (F). The uninjured contralateral limb served as a comparative control. MM, minced muscle. Color images are available online.

In vivo contractile torque measurement

Isometric peak tetanic contractions produced by the treated and contralateral normal TA muscles were measured in-vivo using the procedure described by Corona and familiar to our group.9,23,26 Briefly, the lower limb of each animal was stabilized at 90° of knee flexion through a custom alignment jig. The foot was secured to the lever arm of a muscle force measurement and recording system (Aurora Scientific). Before nerve stimulation, distal tenotomies of the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) and extensor hallucis longus were performed to isolate the force contribution of the TA muscle. Percutaneous needle electrodes were inserted into the anterior compartment of the TA muscle and the peroneal nerve was stimulated through a physiological stimulator (Grass; S88). Optimal voltage (2–5 V) was determined using a series of tetanic contractions (150 Hz, 0.1 ms pulse width, 400 ms train [3-month animals] and 200 ms train [18-month animals]). The isometric peak torque value (Ncm) for each animal was calculated as the mean from five consecutive contractions with 1-min rest periods in between each contraction. Treated and contralateral normal TA muscles were harvested and trimmed to remove fascia, rinsed in sterile PBS, dabbed dry, and then weighed. Peak torque and TA wet mass values for each animal were normalized to contralateral limb values and are presented as %normal in the results.

Tissue histology

Harvested TA muscles were flash frozen in isopentane (2-methylbutane), chilled in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Tissue cross-sections (8 μm) of the repair site were obtained through cryostat (Leica BioSystems) maintained at a temperature between −25°C and −20°C. Before immunostaining, sections were permeabilized in 0.1% 100 × Triton and then rinsed in PBS (pH 7.4). Sections were blocked in PBS containing 4% goat serum and 0.05% sodium azide for 1 h at room temperature before incubation in primary antibodies, including mouse-anti-collagen I IgG (1:500; Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit polyclonal anti-collagen III (1:1000; Abcam), and mouse-anti-myosin IgG2B (MF-20, 1:10, University of Iowa Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) for 2 h at room temperature. Following PBS washes, sections were incubated in the appropriate fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies (AlexaFluor, 1:500; Life Technologies) for 30 min at room temperature. Additional tissue sections were stained using the Masson's Trichrome Kit following the manufacturer's guidelines (Sigma-Aldrich).

Image analysis

Three nonadjacent tissue sections, separated by ∼500–700 μm, collected from four animals per age and treatment group were used for all image analyses. A total of 12 sections (4 animals × 3 sections/animal) were imaged (100 × ) at the site of injury or repair. Normal contralateral TA muscles were also imaged. All images were converted to 8-bit grayscale and a uniform threshold was applied to isolate collagen type I immuno-positive tissue regions within each section. Collagen type I+ tissue area as a percentage of total tissue area (collagen I+ area fraction) was calculated using image analysis software (ImageJ; NIH) following established techniques familiar to our group.23 Similar image analysis methods were used to compute the collagen III+ area fraction. To measure myofiber cross-sectional areas within magnified images (typically 300+ myofibers/image), collagen III immunostained images were converted to grayscale and thresholded to isolate the borders of individual muscle fibers.

Gene expression

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed using the protocol reported by Washington et al.27 In preparation for RT-PCR, TA muscle tissue (∼30 mg) was collected from the site of injury/treatment (n = 4 animals/group) and homogenized with TRIzol (Ambion)/chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich). Homogenized samples were treated with DNase (Invitrogen) and then RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Kit (Invitrogen). After quantification of RNA with UV spectrophotometry (BioTek), cDNA was reverse transcribed from 1 μg of total RNA (Invitrogen). TaqMan primers (Invitrogen) for Col I, Col III, TGF-β, IGF-1, Pax7, MyoD, MyoG, IL-1β, TNF-α, and 18S rRNA housekeeping were used to quantify the expression of desired genes. The 18S rRNA expression was consistent between all groups. Experimental sample group expressions were normalized to 18S rRNA and then referenced to the contralateral normal limb. Gene expression levels are reported as fold change using the 2−(ΔΔCt) method.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation and was tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilks Test. All dependent variables (animal growth; TA and EDL muscle mass; peak tetanic force, collagen I+ area fraction, and collagen III+ area fraction, fiber cross-sectional area) were analyzed using a two-way (age and treatment) ANOVA. Post hoc comparisons were performed using Tukey's test and if present, interaction effects were reported. Comparison between 3- and 18-month rtPCR results were conducted by Student's t-test. Chi-square analysis was performed to compare fiber area distributions. All analyses were performed using commercial statistical analysis software (JMP 13). A standard p < 0.05 level of significance was used for all statistical tests.

Results

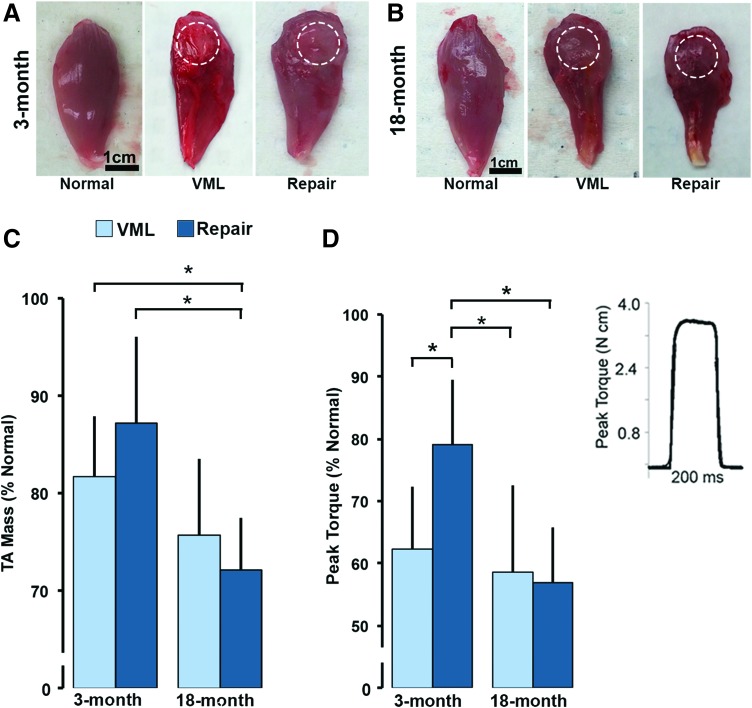

TA appearance and mass

Compared with contralateral normal TA muscle, VML injured and DSM+MM-repaired muscles collected from both 3- and 18-month age groups appeared atrophied; and were characterized by a distinct defect visible at the site of injury or repair (Fig. 3A, B). A significant main effect of age (p = 0.0002), but not treatment (p = 0.63), to reduce the % normal TA mass was detected. The mean %normal mass for both the 18-month VML and 18-month DSM+MM groups were on average 23% and 34% smaller than their 3-month counterparts, respectively (Fig. 3C). A significant interaction effect between age and treatment (p = 0.03) on TA mass was also detected. When examined in age 3-month animals, DSM+MM repair increased the %normal TA mass by 7% when compared with the unrepaired VML group (87.2 ± 8.8 vs. 81.7% ± 6.3%). Alternatively, DSM+MM repair led to a 5% decrease in %normal TA mass compared with VML when examined in 18-month animals (72.1% ± 5.4% vs. 75.1% ± 7.8%). The increase in %normal TA mass between 3- and 18-month DSM+MM repair groups was significant (p = 0.0021).

FIG. 3.

Gross morphology of 3-month (A) and 18-month (B) normal, VML, and DSM+MM-repaired TA muscles. Dashed circle indicates the approximate location and boundary of the defect site. TA muscle wet weight (C) and peak torque (D) was normalized to animal weight (N mm/kg) and calculated relative to normal contralateral TA muscle values (%normal) for each animal tested. Representative in vivo TA torque recording (D inset). Relative muscle wet weight and peak torque data are presented. Data are presented as group mean + SD; n = 7–8/group; *statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences between groups. Color images are available online.

Peak contractile torque

In vivo muscle torque recordings were characterized by a rapid rise in torque, followed by a stable plateau at the peak value, and ending with a sharp descent to a no-torque resting state (Fig. 3D: inset). Similar to the response observed in the mass data, a significant effect of age (p = 0.004) to decrease the %normal TA torque was detected. Mean 18-month VML (58.6% ± 14.0%) and 18-month DSM+MM (57.1% ± 8.7%) %normal peak torque values were 3% and 47% lower than their 3-month VML (62.3 ± 10.1) and DSM+MM (79.0% ± 12.2%) counterparts, respectively (Fig. 3D). A significant interaction between age and treatment was also detected within the torque data (p = 0.03). Mean 3-month torque values recovered to 79.9% ± 12.2% of normal in response to DSM+MM repair, a 45% increase when compared with the 3-month VML group (62.3% ± 10.1%). The difference between the 3-month VML and 3-month DSM+MM peak torque mean was significant (p = 0.036). Alternatively, within the 18-month group, DSM+MM repair had a nonsignificant effect (p = 0.85) on %normal peak torque (57.1% ± 8.7%) when compared with the VML injured group (58.6% ± 14%).

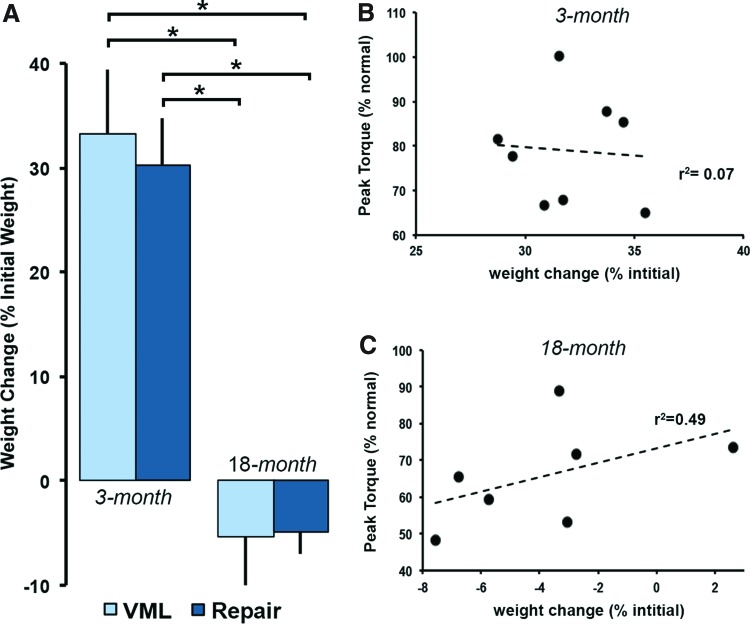

Animal weight change and peak torque correlation

There was a significant effect with age to decrease animal growth (p < 0.0001). On average, the 3-month animals gained 101 ± 17 g by the completion of the 12-week study period. Alternatively, the 18-month animals lost an average of 28 ± 29 g by the end of the study period. Although age significantly affected animal growth, we did not detect a significant effect on growth with treatment (Fig. 4A). Both the 3-month VML (8.8 ± 1.7 g/week) and DSM+MM (8.1 ± 1.2 g/week) groups gained weight at a similar rate. Similarly the 18-month VML and DSM+MM groups lost weight at comparable rates of −2.6 ± 2.9 g/week and −1.7 ± 0.80 g/week, respectively. Examination of the relationship between peak TA torque and animal weight change did not reveal a significant correlation (Fig. 4B, r2 = 0.07) within the 3-month DSM+MM repair data. However, within the 18-month DSM+MM group, there was a modest positive correlation (Fig. 4C, r2 = 0.49) between peak TA torque and animal weight change.

FIG. 4.

Animal weight was recorded at the time of surgery (initial) and sacrifice (final) for each age and treatment group. Animal weight change (% initial) was quantified using initial and final animal weight values (A). Data are presented as group mean + SD; n = 7–8/group; *statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences between groups. Scatter plots, least square method linear correlation fits, and sample coefficients of determination (r2) for animal weight change versus peak torque data are shown for both the 3-month (B) and 18-month DSM+MM repair groups (C). Color images are available online.

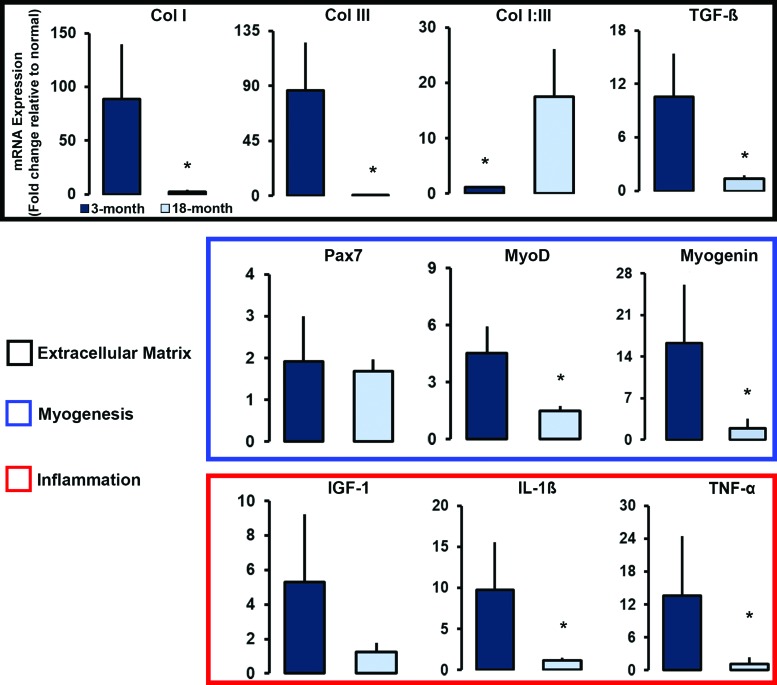

Gene expression

Within the transcription factors related to myogenesis, both MyoD (p = 0.006) and MyoG (p = 0.03) expression was significantly elevated in the 3-month DSM+MM repair group when compared with the 18-month repair group (Fig. 5). No significant difference was detected for Pax7 expression; both 3- and 18-month DSM+MM repair groups exhibited comparably elevated levels (1.9 ± 1.1-fold change vs. 1.7 ± 0.3-fold change). Age had a significant effect on several ECM and ECM-related genes of interest. Significantly elevated expression levels for both Col I (p = 0.044) and Col III (p = 0.047) were detected in the 3-month DSM+MM repair group when compared with the 18-month DSM+MM group. Col I and III expression was 35-fold (88.6 ± 51.2 vs. 2.5 ± 1.9) and 800-fold (86.0 ± 39.19-fold change vs. 0.1 ± 0.01) higher in the 3-month repair group. While the expression of Col I and III were both elevated in the 3-month DSM+MM repair group, the ratio of Col I to Col III gene expression was significantly (p = 0.009) lower (1.1 ± 0.2 vs. 17.5 ± 8.6). TGF-β expression was also significantly elevated (p = 0.01) in the 3-month DSM+MM group compared with the 18-month group (10.5 ± 4.9 vs. 1.4 ± 0.4).

FIG. 5.

Comparison of relative gene expression for 3- and 18-month DSM+MM repair groups using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. The expression of myogenic (Pax7, MyoD, MyoG), ECM (Col I and Col III), ECM regulatory (TGF-β), and inflammation genes (IGF-1, IL-1β, and TNF-α) were measured using muscle tissue harvested from the DSM+MM repair site. Expression is presented as fold change normalized to contralateral normal muscle expression. Group mean + SD are presented, n = 4/group. *Statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences between groups. Color images are available online.

Similar age-related differences were detected for the expression of IL-1β (p = 0.02) and TNF-α (p = 0.04) between the DSM+MM repair groups. The 3-month repair group expressed IL-1β at levels 8.5-fold higher than its 18-month counterpart (9.7 ± 5.9 vs. 1.1 ± 0.4). TNF-α was expressed ∼13-fold higher in the 3-month group compared with the 18-month group (13.7 ± 10.8 vs. 1.2 ± 1.2). Expression of the growth factor IGF-1, although not significantly different between the two age groups (p = 0.08), was expressed at elevated levels in both age groups (5.3 ± 3.9 and. 1.3 ± 0.5).

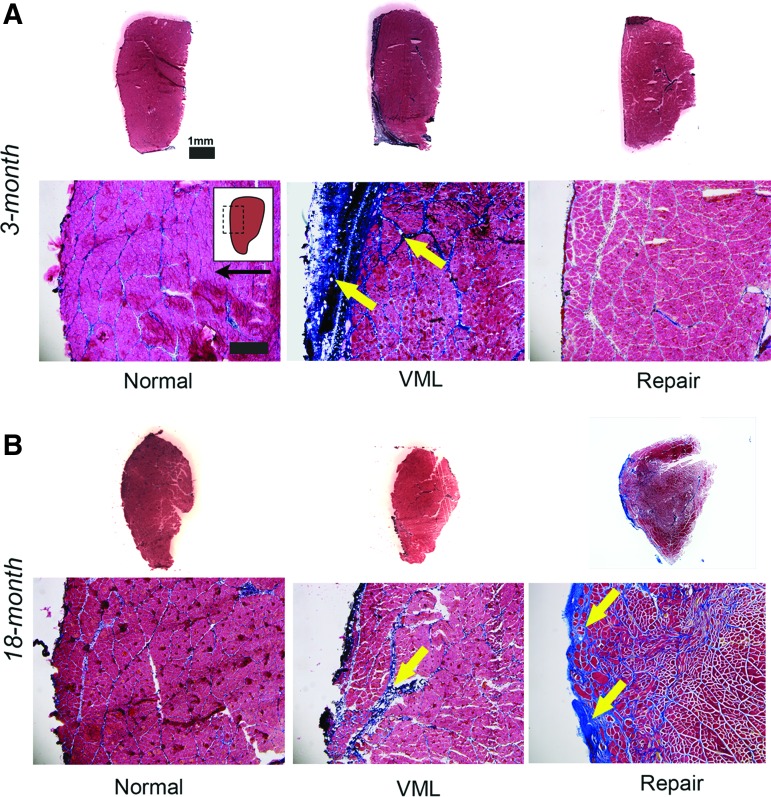

VML site histology

Both 3-month (Figs. 6A and 7A) and 18-month (Figs. 6B and 7B) normal TA muscle cross-sections were characterized by bundles of tightly apposed myofibers surrounded by thin bands of collagen. When compared with normal muscle, both 3- and 18-month VML tissue sections were characterized by a collagen-enriched zone, containing thickened collagen bands. The collagen-enriched zone was notably shallower than the initial VML defect (depth = 3 mm) for both 3- and 18-month groups, typically extending only a few hundred microns into the TA muscle, suggesting atrophy at the muscle surface in response to VML injury. Following DSM+MM repair, 18-month TA cross-sections were similarly characterized by a collagen-enriched zone containing myofiber bundles surrounded by thickened collagen bands. Alternatively, 3-month DSM+MM repair-site tissue was notably devoid of abnormal collagen repair tissue and while the muscle as a whole was atrophied, the collagen and myofiber staining appeared qualitatively similar to normal TA sections. There was no evidence of immature fibers with centrally located nuclei for either the 3- and 18-month DSM+MM repair groups, suggesting either negligible new fiber formation or resolution and maturation of any new fibers by the 12-week time point.

FIG. 6.

TA muscle cross-sections were stained with Masson's Trichrome. Representative 3-month (A) and 18-month (B) normal, VML, and DSM+MM repair groups are presented. Representative whole TA cross-sections and magnified (100 × ) images are shown. Arrows highlight regions and bands of fibrotic collagen accumulation. Inset indicates approximate location of magnified image within the TA cross-section. Arrow indicates anterior direction. Scale bar = 100 μm unless noted. Color images are available online.

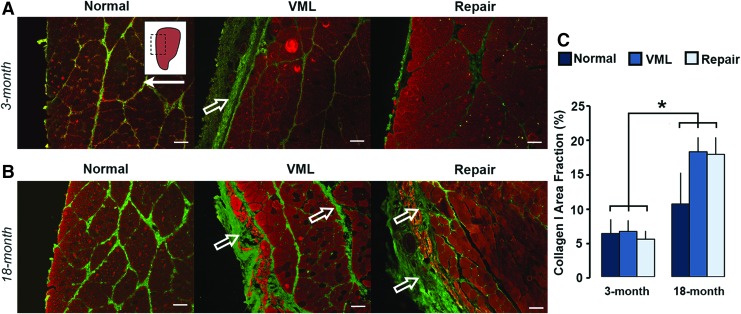

FIG. 7.

TA tissue cross-sections were immunostained for collagen I (green) and counterstained against MHC (red). Representative 3-month (A) and 18-month (B) normal, VML, and DSM+MM-repaired tissue images are shown. Inset indicates approximate location of magnified (100 × ) image within TA tissue section. Arrow indicates anterior direction. Open arrows highlight regions and bands of fibrotic collagen I accumulation. Scale bar = 100 μm. Cross-sections were quantified for area fraction of collagen type I (C). Group mean + SD are presented; n = 4/group. *Statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences between groups. Color images are available online.

Collagen I and III area fraction

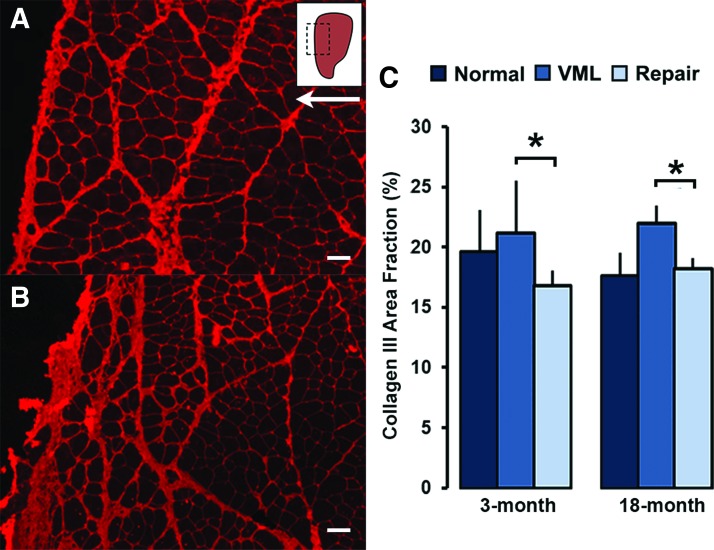

A main effect of age (p = 0.0009), but not treatment (p = 0.44) to increase the collagen I+ area fraction was detected (Fig. 7C). Mean 18-month collagen I+ area fractions for normal (10.4% ± 4.5%), VML (17.9% ± 4.5%), and DSM+MM (17.6% ± 9.3%) groups were on average two- to threefold higher than their 3-month normal (6.2% ± 2.0%), VML (6.5% ± 1.6%), and DSM+MM (5.4% ± 1.2%,) counterparts. The differences between 3- and 18-month collagen I+ area fractions were significant across all groups. Alternatively, a significant main effect of treatment (p = 0.045), but not age, to decrease area fraction was detected within the collagen III sections (Fig. 8A, B). On average, DSM+MM implantation decreased the collagen III+ area fraction by 21% and 17% when compared with VML for the 3- and 18-month age groups, respectively (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

TA tissue cross-sections were immunostained for collagen III (red). Representative 3-month (A) and 18-month (B) DSM+MM repair site images are shown. Inset indicates approximate location of magnified (100 × ) image within TA tissue section. Arrow indicates anterior direction. Scale bar = 100 μm. Cross-sections were quantified for area fraction (%) collagen type III (C). Group mean + SD are presented; n = 4/group. *Statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences between groups. Color images are available online.

Myofiber cross-sectional area

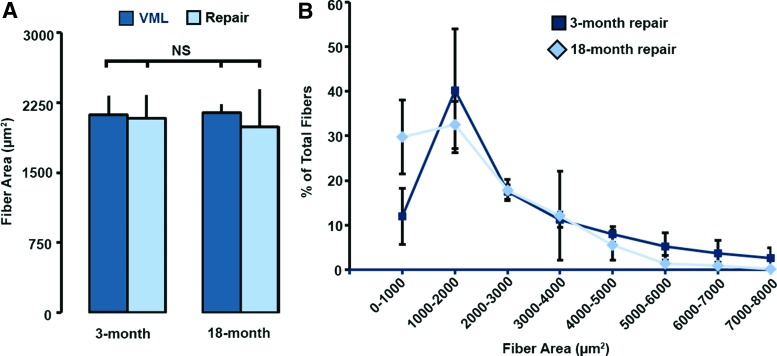

Mean muscle myofiber cross-sectional area at the site of TA injury (VML) or repair (DSM+MM) was not significantly affected by age (Fig. 9A). Mean myofiber diameter values for both 3-month (2085 ± 245 μm2) and 18-month (1993 ± 400 μm2) DSM+MM repair groups were within 10% of both normal and VML injured values. Myofiber size distribution histograms (Fig. 9B) for both the 3- and 18-month DSM+MM repair groups were characterized by a frequency peak at myofiber sizes in the range of 1000–2000 μm2. The 18-month DSM+MM group exhibited an elevated (twofold) population of small myofibers (0–1000 μm2) when compared with the 3-month group; however, no significant difference in myofiber size distribution were detected between the 3- and 18-month DSM+MM repair groups. A summary of the key outcome measures (mean ± standard deviation) is provided in Table 1.

FIG. 9.

Individual myofiber areas were measured from collagen III-stained tissue cross-sections. Group data for myofiber cross-sectional area (A) and area frequency distribution are shown (B). Group mean + SD are presented; n = 4/group; NS = no significance (p > 0.05). Color images are available online.

Table 1.

Summary of the Key Outcome Measures

| Animal Group | Growth (g/week) | TA mass (g/kg) | EDL mass (g/kg) | Peak torque (N.cm/kg) | Collagen I (% area) | Collagen III (% area) | Fiber cross-sectional area (μm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months | |||||||

| VML | 8.8 ± 1.7 | 1.27 ± 0.09 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 5.64 ± 0.29 | 6.5 ± 0.8 | 21.4 ± 4.4 | 2123 ± 200 |

| DSM+MM | 8.1 ± 1.2 | 1.35 ± 0.15 | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 6.85 ± 0.76 | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 16.9 ± 1.2 | 2085 ± 245 |

| 18 months | |||||||

| VML | −2.6 ± 2.9 | 1.01 ± 0.11 | 0.35 ± 0.07 | 4.58 ± 1.15 | 17.9 ± 4.5 | 22.2 ± 1.5 | 2146 ± 89 |

| DSM+MM | −1.7 ± 0.8 | 0.96 ± 0.09 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 4.31 ± 0.64 | 17.8 ± 9.3 | 18.4 ± 0.9 | 1993 ± 400 |

Values are mean ± SD.

DSM, decellularized skeletal muscle; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; MM, minced muscle; VML, volumetric muscle loss.

Discussion

In this in vivo study, we observed significant effects with age on the response to regenerative repair of VML injury as well as significant interactions between age and repair. Specifically, the repair of VML defects using a combination of DSM scaffolds and MM paste recovered approximately half (45%) of the force lost to VML injury when examined in the 3-month-old rat model (3 months = 12.5% of median lifespan), but was ineffective (recovery = −1%) when tested in the 18-month-old model (18 months = 75% of median lifespan). The age-related decrease in regenerative therapy effectiveness is meaningful when one considers the broad age range of patients that could benefit from VML treatment strategies. Overall, the results of this study suggest that the successful translation of VML injury treatment strategies to the clinic may be compromised by patient age.

Generally, a sustained inflammatory response has been associated with chronic inflammatory myopathies and disorders such as muscular dystrophy and myositis, which have been shown to lead to excessive fibrosis and stagnation of the normal regenerative program.28,29 However, recent studies have also demonstrated important roles for inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, in the regulation of the regenerative process. TNF-α attracts satellite cells to the injury site as well as promotes satellite cell proliferation and myoblast differentiation through activation of NF-κβ and p38 MAPK signaling, respectively.30,31 These findings are consistent with our observations in functional recovery and gene expression data, where there was significant upregulation of TNF-α and MyoD in the 3-month repair group as well as a significant increase in peak torque values compared with the older 18-month repair group. The low expression of TNF-α in the 18-month repair group could be suggestive of low or inactivation of p38 MAPK activity, which has been demonstrated to downregulate the expression of muscle differentiation markers, such as MyoD and MyoG.31,32 Similar to TNF-α, IL-1β is able to stimulate migration, proliferation, and differentiation of myoblasts, although indirectly, by stimulating the secretion of IL-6 from skeletal muscle cells.29,33,34 Gene expression in the 3-month repair group compared with the 18-month group mirrors the observations of TNF-α expression and may speak to the aberrant inflammatory response and muscle homeostatic maintenance of the older 18-month rat group.35–37

In addition to an overall reduction in the pool of available satellite cells within aged muscle there is also a phenotypic shift of satellite cells from a myogenic to fibrogenic lineage.38,39 This shift in lineage is attributed to dysfunction in satellite cell proliferative capacity40 and divergence toward fibrogenicity,41 which is largely influenced by soluble factors in the aging tissue microenvironment. The age-related shift in satellite cell behavior toward a profibrotic phenotype is consistent with our observed results. Histological and quantitative collagen I+ area fraction measurements revealed regions of increased collagen deposition within and around the area of injury and repair when compared with the nonaged model repair site. Additionally, the heightened profibrotic response is capable of further impairing muscle fiber regeneration and force recovery through deregulation of satellite cells driven by interactions with fibrotic ECM.42–44 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that increased collagen deposition can decrease growth factor diffusion within the repair site and hinder satellite cell migration, leading to incomplete regeneration at the site of injury.45 The composition of the ECM at the site of repair can also have a negative effect on muscle regeneration.46 Within tissue collected at the site of repair from the 18-month rats, the ratio of Col I to Col III gene expression (Col I:III) was markedly elevated (17:1), whereas tissue from the 3-month rats exhibited a ratio closer to 1:1. Unusually high ratios of collagen I to collagen III have been associated with hypertrophic scar formation in wound healing as well as decreased sensitivity to growth factors.47

The regenerative medicine strategy that was used as the test bed for this study employed a combinatorial (scaffold+cells) approach that is similar in concept to other strategies under examination.3,18,48,49 The broad similarities between our test bed and others, provide some confidence that the age-related effects we observed in this study are relevant to the cell- and tissue-based regenerative medicine strategies under investigation by other research teams. Specifically, we utilized a combination of allogeneic DSM scaffolds and autologous MM paste to restore the architectural and cellular cues lost to VML injury. The implantation of progenitor cells using autogenic MM is a long-established approach50,51 that has recently shown promising myogenic potential when used for the repair of VML injuries by research groups, including our own.9,26,52 While differences do exist, the use of MM is comparable to the delivery of pure populations of progenitor cells employed by other strategies.14,18 Likewise, the muscle-derived ECM scaffolds used in this study, although allogeneic have compositional qualities that are similar to xenogeneic tissue-derived scaffolds, which have been examined extensively by other groups.13,53–56 The similarities between VML strategies is important, and suggests that the age-related obstacles to VML repair that were observed in this study are not exclusive to the DSM+MM strategy and in fact are likely to impede other VML regenerative medicine approaches.

Lastly, a limitation to this study that deserves discussion is the lack of an early postimplantation time point that would provide the data needed to identify specific wound healing events responsible for the age-related differences in functional outcome. The 12-week endpoint examined in this study, while appropriate for the examination of functional recovery, misses the key promyogenic milestones that occur during the first few weeks of muscle healing.57,58 In particular, the examination of acute time points may reveal key age-sensitive differences in cellular and soluble factor (cytokines and growth factors) responses that occur following regenerative VML repair.59,60 The gene expression results measured in this study demonstrate that promyogenic transcription pathways and cytokines are elevated at 12 weeks in the nonaged animal model suggesting ongoing regenerative processes, but it remains unclear whether the muted myogenic response observed at 12 weeks in the aged animal was similarly muted during early healing. Early time points could reveal whether all or only specific key myogenic milestones are impaired within the VML repair site of aging muscle, and could provide valuable insights that would inform age-targeted therapeutic strategies.

Conclusion

In summary, this study is the first to demonstrate an age-dependent response to repair of a VML injury utilizing a tissue-engineered therapy. Notably, the repair of VML defects using a combination of tissue scaffolds and MM paste recovered approximately half of the force lost to VML injury when examined in a 3-month rat model, but was ineffective when tested in the 18-month model. The 18-month animal model was characterized by an increase in scarring at the site of repair and a reduction in the expression of key myogenic genes. When taken together, the findings suggest that a decline in regenerative capacity with age may present an obstacle to regenerative medicine strategies targeting VML injury.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15AR064481 as well as the Arkansas Biosciences Institute.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Dziki J., Badylak S., Yabroudi M., et al. An acellular biologic scaffold treatment for volumetric muscle loss: results of a 13-patient cohort study. NPJ Regen Med 1, 16008, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Corona B.T., Wu X., Ward C.L., McDaniel J.S., Rathbone C.R., and Walters T.J.. The promotion of a functional fibrosis in skeletal muscle with volumetric muscle loss injury following the transplantation of muscle-ECM. Biomaterials 34, 3324, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldman S.M., Henderson B.E.P., Walters T.J., and Corona B.T.. Co-delivery of a laminin-111 supplemented hyaluronic acid based hydrogel with minced muscle graft in the treatment of volumetric muscle loss injury. PLoS One 13, e0191245, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldman S.M., and Corona B.T.. Co-delivery of micronized urinary bladder matrix damps regenerative capacity of minced muscle grafts in the treatment of volumetric muscle loss injuries. PLoS One 12, e0186593, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Corona B.T., Henderson B.E., Ward C.L., and Greising S.M.. Contribution of minced muscle graft progenitor cells to muscle fiber formation after volumetric muscle loss injury in wild-type and immune deficient mice. Physiol Rep 5, pii: , 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Garg K., Ward C.L., Rathbone C.R., and Corona B.T.. Transplantation of devitalized muscle scaffolds is insufficient for appreciable de novo muscle fiber regeneration after volumetric muscle loss injury. Cell Tissue Res 358, 857, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li M.T., Willett N.J., Uhrig B.A., Guldberg R.E., and Warren G.L.. Functional analysis of limb recovery following autograft treatment of volumetric muscle loss in the quadriceps femoris. J Biomech 47, 2013, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nakayama K.H., Alcazar C., Yang G., et al. Rehabilitative exercise and spatially patterned nanofibrillar scaffolds enhance vascularization and innervation following volumetric muscle loss. NPJ Regen Med 3, 16, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kasukonis B., Kim J., Brown L., et al. Codelivery of infusion decellularized skeletal muscle with minced muscle autografts improved recovery from volumetric muscle loss injury in a rat model. Tissue Eng Part A 22, 1151, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dziki J.L., Sicari B.M., Wolf M.T., Cramer M.C., and Badylak S.F.. Immunomodulation and mobilization of progenitor cells by extracellular matrix bioscaffolds for volumetric muscle loss treatment. Tissue Eng Part A 22, 1129, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Valentin J.E., Turner N.J., Gilbert T.W., and Badylak S.F.. Functional skeletal muscle formation with a biologic scaffold. Biomaterials 31, 7475, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Corona B.T., Machingal M.A., Criswell T., et al. Further development of a tissue engineered muscle repair construct in vitro for enhanced functional recovery following implantation in vivo in a murine model of volumetric muscle loss injury. Tissue Eng Part A 18, 1213, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Corona B.T., Ward C.L., Baker H.B., Walters T.J., and Christ G.J.. Implantation of in vitro tissue engineered muscle repair constructs and bladder acellular matrices partially restore in vivo skeletal muscle function in a rat model of volumetric muscle loss injury. Tissue Eng Part A 20, 705, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Merritt E.K., Cannon M.V., Hammers D.W., et al. Repair of traumatic skeletal muscle injury with bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells seeded on extracellular matrix. Tissue Eng Part A 16, 2871, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Owens J.G., Blair J.A., Patzkowski J.C., Blanck R.V., Hsu J.R., and Skeletal Trauma Research Consortium. Return to running and sports participation after limb salvage. J Trauma 71, S120, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mase V.J. Jr., Hsu J.R., Wolf S.E., et al. Clinical application of an acellular biologic scaffold for surgical repair of a large, traumatic quadriceps femoris muscle defect. Orthopedics 33, 511, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Owens B.D., Kragh J.F. Jr., Wenke J.C., Macaitis J., Wade C.E., and Holcomb J.B.. Combat wounds in operation Iraqi freedom and operation enduring freedom. J Trauma 64, 295, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Quarta M., Cromie M., Chacon R., et al. Bioengineered constructs combined with exercise enhance stem cell-mediated treatment of volumetric muscle loss. Nat Commun 8, 15613, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gilbert-Honick J., Ginn B., Zhang Y., et al. Adipose-derived stem/stromal cells on electrospun fibrin microfiber bundles enable moderate muscle reconstruction in a volumetric muscle loss model. Cell Transplant 2018. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1177/0963689718805370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin C.H., Lin Y.T., Yeh J.T., and Chen C.T.. Free functioning muscle transfer for lower extremity posttraumatic composite structure and functional defect. Plast Reconstruct Surg 119, 2118, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Domingues-Faria C., Vasson M.P., Goncalves-Mendes N., Boirie Y., and Walrand S.. Skeletal muscle regeneration and impact of aging and nutrition. Ageing Res Rev 26, 22, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Conboy I.M., and Rando T.A.. Aging, stem cells and tissue regeneration: lessons from muscle. Cell Cycle 4, 407, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim J.T., Kasukonis B.M., Brown L.A., Washington T.A., and Wolchok J.C.. Recovery from volumetric muscle loss injury: a comparison between young and aged rats. Exp Gerontol 83, 37, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Parker L., Caldow M.K., Watts R., Levinger P., Cameron-Smith D., and Levinger I.. Age and sex differences in human skeletal muscle fibrosis markers and transforming growth factor-beta signaling. Eur J Appl Physiol 117, 1463, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kasukonis B.M., Kim J.T., Washington T.A., and Wolchok J.C.. Development of an infusion bioreactor for the accelerated preparation of decellularized skeletal muscle scaffolds. Biotechnol Prog 32, 745, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Corona B.T., Garg K., Ward C.L., McDaniel J.S., Walters T.J., and Rathbone C.R.. Autologous minced muscle grafts: a tissue engineering therapy for the volumetric loss of skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 305, C761, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Washington T.A., Brown L., Smith D.A., Davis G., Baum J., and Bottje W.. Monocarboxylate transporter expression at the onset of skeletal muscle regeneration. Physiol Rep 1, e00075, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Loell I., and Lundberg I.E.. Can muscle regeneration fail in chronic inflammation: a weakness in inflammatory myopathies? J Intern Med 269, 243, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Porter J.D., Khanna S., Kaminski H.J., et al. A chronic inflammatory response dominates the skeletal muscle molecular signature in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Hum Mol Genet 11, 263, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peterson J.M., Bakkar N., and Guttridge D.C.. NF-kappaB signaling in skeletal muscle health and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol 96, 85, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen S.E., Jin B., and Li Y.P.. TNF-alpha regulates myogenesis and muscle regeneration by activating p38 MAPK. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292, C1660, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhan M., Jin B., Chen S.E., Reecy J.M., and Li Y.P.. TACE release of TNF-alpha mediates mechanotransduction-induced activation of p38 MAPK and myogenesis. J Cell Sci 120, 692, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Luo G., Hershko D.D., Robb B.W., Wray C.J., and Hasselgren P.O.. IL-1beta stimulates IL-6 production in cultured skeletal muscle cells through activation of MAP kinase signaling pathway and NF-kappa B. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 284, R1249, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Munoz-Canoves P., Scheele C., Pedersen B.K., and Serrano A.L.. Interleukin-6 myokine signaling in skeletal muscle: a double-edged sword? FEBS J 280, 4131, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang C., Li Y., Wu Y., Wang L., Wang X., and Du J.. Interleukin-6/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway is essential for macrophage infiltration and myoblast proliferation during muscle regeneration. J Biol Chem 288, 1489, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Joe A.W., Yi L., Natarajan A., et al. Muscle injury activates resident fibro/adipogenic progenitors that facilitate myogenesis. Nat Cell Biol 12, 153, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kami K., and Senba E.. Localization of leukemia inhibitory factor and interleukin-6 messenger ribonucleic acids in regenerating rat skeletal muscle. Muscle Nerve 21, 819, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carlson B.M. Factors influencing the repair and adaptation of muscles in aged individuals: satellite cells and innervation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 50 Spec No, 96, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grounds M.D. Age-associated changes in the response of skeletal muscle cells to exercise and regeneration. Ann N Y Acad Sci 854, 78, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Conboy I.M., Conboy M.J., Wagers A.J., Girma E.R., Weissman I.L., and Rando T.A.. Rejuvenation of aged progenitor cells by exposure to a young systemic environment. Nature 433, 760, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brack A.S., Conboy M.J., Roy S., et al. Increased Wnt signaling during aging alters muscle stem cell fate and increases fibrosis. Science 317, 807, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Alnaqeeb M.A., Al Zaid N.S., and Goldspink G.. Connective tissue changes and physical properties of developing and ageing skeletal muscle. J Anat 139(Pt 4), 677, 1984 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Serrano A.L., Mann C.J., Vidal B., Ardite E., Perdiguero E., and Munoz-Canoves P.. Cellular and molecular mechanisms regulating fibrosis in skeletal muscle repair and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol 96, 167, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mann C.J., Perdiguero E., Kharraz Y., et al. Aberrant repair and fibrosis development in skeletal muscle. Skelet Muscle 1, 21, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hindi S.M., Shin J., Ogura Y., Li H., and Kumar A.. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibition improves proliferation and engraftment of myogenic cells in dystrophic muscle of mdx mice. PLoS One 8, e72121, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lehto M., Sims T.J., and Bailey A.J.. Skeletal muscle injury—molecular changes in the collagen during healing. Res Exp Med (Berl) 185, 95, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Garner W.L., Karmiol S., Rodriguez J.L., Smith D.J. Jr., and Phan S.H.. Phenotypic differences in cytokine responsiveness of hypertrophic scar versus normal dermal fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol 101, 875, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gilbert-Honick J., Iyer S.R., Somers S.M., et al. Engineering functional and histological regeneration of vascularized skeletal muscle. Biomaterials 164, 70, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Qiu X., Liu S., Zhang H., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and extracellular matrix scaffold promote muscle regeneration by synergistically regulating macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype. Stem Cell Res Ther 9, 88, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Carlson B.M. Regeneration fo the completely excised gastrocnemius muscle in the frog and rat from minced muscle fragments. J Morphol 125, 447, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Studitsky A.N. Free auto- and homografts of muscle tissue in experiments on animals. Ann N Y Acad Sci 120, 789, 1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ward C.L., Ji L., and Corona B.T.. An autologous muscle tissue expansion approach for the treatment of volumetric muscle loss. BioRes Open Access 4, 198, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Turner N.J., Badylak J.S., Weber D.J., and Badylak S.F.. Biologic scaffold remodeling in a dog model of complex musculoskeletal injury. J Surg Res 176, 490, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sicari B.M., Agrawal V., Siu B.F., et al. A murine model of volumetric muscle loss and a regenerative medicine approach for tissue replacement. Tissue Eng Part A 18, 1941, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Urciuolo A., Urbani L., Perin S., et al. Decellularised skeletal muscles allow functional muscle regeneration by promoting host cell migration. Sci Rep 8, 8398, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Allman A.J., McPherson T.B., Badylak S.F., et al. Xenogeneic extracellular matrix grafts elicit a TH2-restricted immune response. Transplantation 71, 1631, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tidball J.G. Inflammatory processes in muscle injury and repair. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288, R345, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tidball J.G. Regulation of muscle growth and regeneration by the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 17, 165, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tidball J.G. Mechanisms of muscle injury, repair, and regeneration. Compr Physiol 1, 2029, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tidball J.G. Inflammatory cell response to acute muscle injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc 27, 1022, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]