EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYThe Committee was charged with the responsibility for examining the need for change in pharmacy education and the models of leadership that would enable that change to occur across the academy. They also examined the question of faculty wellbeing in a time of change and made several recommendations and suggestions regarding both charges. Building upon the work of the previous Academic Affairs Committee, the 2018-19 AAC encourages the academy to implement new curricular models supporting personalized learning that creates engaged and lifelong learners. This will require transformational leadership and substantial investments in faculty development and new assessment strategies and resources. Recognizing that the magnitude of the recommended change will produce new stress on faculty, the committee identified the need for much additional work on student, faculty and leaders’ wellbeing, noting the limited amount of empirical evidence on pharmacy related to stress and resilience. That said, if faculty and administrators are not able to address personal and community wellbeing, their ability to support their students’ wellbeing will be compromised.

Keywords: Leadership, change, personalized learning, well-being, faculty development

INTRODUCTION

President Allen charged the 2018-19 Academic Affairs Committee to critically examine the leadership characteristics associated with effective change as well as those that create an environment that promotes wellness for leaders, faculty, staff and learners. The specific charges are as follows

Create a vision of large-scale changes that need to happen in pharmacy and healthcare education and how AACP can foster a culture of change leadership across the academy that moves the profession toward these changes.

Identify and articulate the leadership and other competencies that are essential for the faculty member of 2020 to be aware and promote wellness for themselves, their colleagues and students in health professions education.

Building on the lifelong learning work of the 2017-2018 Academic Affairs committee, create awareness and educational programs that AACP can implement as CPD certificate programs across the academy.

The Committee conducted their work using conference calls and convened for an in-person meeting on October 9 and 10, 2018 in Washington, DC.

This year’s Academic Affairs Committee reaffirms multiple policies and recommends several new policies/recommendations related to educational modifications and the need to monitor faculty/student wellbeing throughout these transformations. To effectively implement change, one needs to have an amenable culture and the leadership that is ready to guide it.1,2 This leadership needs to occur both among those with a leadership title (“Big L”) and among faculty who can help drive the process (“Little l”).

Studies have shown that change initiatives oftentimes fail or make the situation worse. A 2002 study found that out of 40 major change initiatives, 58% failed and 20% did not achieve the value expected.3 Many times these failures occur due to a lack of effective leadership.1

This report will present different types of change with an emphasis on the type needed to implement the committee’s recommendations. The leadership characteristics are discussed, and a potential change model is provided.

TYPES OF CHANGE

Change can be classified as transitional, transformational, or developmental, and the classification determines the form of leadership needed to implement it. Transitional changes are small, gradual, and incremental things that occur in people, politics, procedures, technology, culture, and organizational structures over time. Lower level administrators and faculty usually drive this. Transformational change typically originates from the top leadership, and occurs with radical shifts in assumptions, culture, and strategy of a group or organization. Developmental change is usually continuous and is the result of the organization’s desire for continual growth and development. This type of change rewards individual innovation, growth, and development to prevent the need for transformational change.1

Another way to classify change is as tuning, adaptive, re-orientating, or re-creating. Tuning is incremental and anticipatory and does not require redefinition of the system but does require modifications to set the organization up for future events. Adaptive change is incremental and typically in reaction to something. Re-orientation occurs when a change is strategic but anticipated versus one that is strategic and reactionary (re-creation). Re-creations usually involve a transformational change as a modification in core values. Typically, the leadership already in place in an organization can handle the two types of incremental change, but re-orientation and re-creation usually require new leadership with different characteristics.2

Change Model

Any organization traverses several steps as it goes through change. The first step requires unfreezing, which creates the motivation to change. To unfreeze, an organization must have enough disconfirming data to cause disequilibrium, anxiety and/or guilt that results from the disconnection of this data with important organizational goals and ideals. There needs to be a culture of psychological safety in the organization so that people feel that solutions can be developed without leading to a loss of identity. Once unfreezing has occurred, the next step is cognitive restructuring wherein new learning takes place, and refreezing can ensue. Refreezing is where the new behavior/process becomes set and new data can be collected.4

There are multiple different types of change models that can help with these three steps of the change process. The change model being proposed to help implement the recommendations in this paper are a hybrid of the Advancing Research and Clinical Practice Through Close Collaboration (ARCC) and Iowa models. Both emphasize organizational use and development of evidence-based practices that are important to the initiatives recommended in this year’s report.5

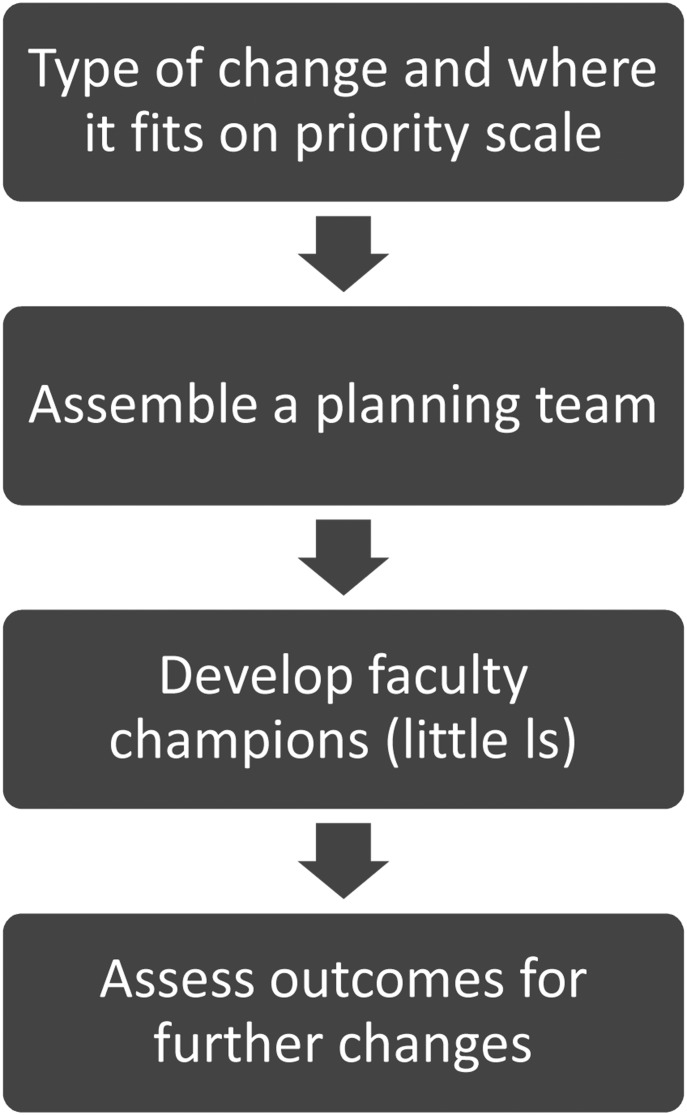

The ARCC model was developed to implement evidence-based practice in nursing. It has five steps developed from cognitive behavioral theory, and it contains an organizational and readiness scale for evidence-based practice to assess organizational culture, as well as an evidence-based implementation scale to determine if the implementation was successful. The Iowa model was developed as a research utilization model for the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. It too has been revised over the years to focus on the implementation of evidence-based practice. This model has a flow-chart guide for decision-making and is designed around problem-solving steps. Engaging an interdisciplinary approach, it uses feedback loops and trials of the practice change prior to full implementation. The Academic Affairs Committee supports a combination of these models to initiate the changes recommended in this report (Figure 1).5

Figure 1.

Change Model

As a first step in this change model, the school/college should determine the type of change being initiated and where on the priority chain it fits. This requires assessing the organizational culture and readiness for change as well as identifying the strengths and barriers to the change. In preparing for the change, a planning team should be assembled to search, critique, and synthesize literature to develop a fully thought out, evidence-based plan. Once the data has been reviewed, the planning team should decide if there is enough evidence to implement the change or if a small pilot project would be best. With either method chosen, the team should develop faculty champions (little “l” leaders) to help lead the transformation by educating others on the need for the change and the steps in the process. After the change has been implemented, outcomes should be assessed to determine if the change was successful or if adaptations are needed.5

Overall the change process can be complicated and stressful. This stress can be felt by not only those leading the change, but also by those who are part of the change. Good leaders with a well thought out change process can be very helpful in ensuring its success. The remainder of this paper discusses the changes for which the academy can employ this model as well as recommendations for well-being initiatives that schools/colleges can consider while going through these changes.

CHARGE 1: CREATE A VISION OF LARGE-SCALE CHANGES

The Committee addressed the first charge of creating a vision of large-scale changes that need to happen in pharmacy and healthcare education and how AACP can foster a culture of change leadership across the academy that moves the profession toward these changes. They recognize that healthcare changes are inevitable. The United States is spending an increasing share (nearly one-fifth) of its national income on healthcare.6 However, American citizens are not receiving the commensurate benefit of longer, healthier lives. There is great misallocation of resources and widespread inefficiency in the healthcare system.7 The need for change in the healthcare marketplace is imperative. When the state of health and well-being is improved, then greater quality of life ensues. When significant resources are spent on healthcare, they are no longer available for other important individual and national priorities.8

The Committee has identified several changes that may impact pharmacy and healthcare education. These changes include greater adoption of artificial intelligence across global business that is moving into the life-sciences industry.9 Information technology will bring timely treatment to patients at the community-based neighborhood level, where greater expansion of healthcare practitioners will need to be able to respond. Pharmacists will need to be able to stratify care into preventative, self-care, acute and chronic illness practices and work in team-based, collaborative care environments to ascertain and address social determinants of health from birth to death.10 Social determinants of health include the patient’s socioeconomic status, education, their physical environment, employment, and social support networks, as well as their access to healthcare resources.11 Pharmacists will need to learn and work in coordinated care programs and more complex systems of healthcare delivery. They are uniquely situated to respond to this need in number as well as in location as many brick-and-mortar pharmacies exist in these rural and underserved communities. Educational initiatives to further develop requisite knowledge and skills will constantly need to be developed, implemented, and assessed to support the pharmacist’s role in the changing healthcare system, and functioning at the top of their training.12

Transformational Change Emphasizing Personalized Learning

Due to the changes currently occurring in healthcare there needs to be a paradigm shift from thinking of education as a traditional classroom and related activities to a model incorporating a more personalized learning (PL) experience. To do this, a clear, thorough understanding of PL is required. PL incorporates the learner’s past experiences to help engage them in designing a learning environment that stimulates their desire for competence, autonomy, and lifelong learning. The curriculum moves at a pace tailored to the learning preferences and specific interests of each individual learner.15 Implementation of a PL curriculum revolves around a 5-point framework: implementation strategy, instructional design, curricular development, faculty and student support, and physical operations.16 This framework can provide pharmacy schools with the guidance needed to implement a personalized curriculum.

Personalized learning has both its benefits and challenges. Benefits to implementing PL include increasing students’ intrinsic motivation, enriching the learning experience by building upon core course objectives while connecting those to a broader concept, actively engaging the student in their own learning, and offering a high level of choice and flexibility for both students and faculty.14,15,17 These benefits help students to achieve their academic goals and promote lifelong learning. Conversely, challenges to implementing PL include a disconnect between the PL curriculum and available technology, lack of faculty development, and misalignment of measurement of student success between the schools and the outside stakeholders.17

Based upon this information, there are a few considerations for implementing a PL curriculum. First, use of data is essential for PL to succeed. Faculty will need to measure the students’ needs, strengths, and interests to guide assessment of mastery and competency.17 Additionally, the students will need to track their own progress in order to truly own their education and self-reflect to develop their metacognition skills. This constant measurement will help to tailor the instruction to meet each student’s needs over the course of the year. Second, technology becomes a main player within a PL curriculum. A large variety of available technology is needed to not only integrate within the traditional classroom activities, but also to adapt the content as students’ progress through the curriculum.17 Third, significant faculty development must occur on the use of new technology systems and instructional strategies.17 Additionally, it would be helpful for faculty to create their own professional growth plan centered on a specific pedagogy area aligning with the school’s strategic plans and needs.13 Finally, a new strategy for assessing student competency and mastery needs to be developed that includes many different activities, tasks, and options for students.17

Overall, PL will help to fine-tune the skills and knowledge pharmacy students need to be successful and adaptable in our changing healthcare environment. While the concept of a PL-based curriculum is daunting, focusing on the four core elements19 (flexible content and tools, targeted instruction, student reflection and ownership, and data-driven decisions) (Core Four, Ed Elements) will help guide schools through the transformational change needed to bring pharmacy education light years ahead.

Leadership Characteristics for Transformational Change

The type of change occurring in health care and the changes that are needed in education to adjust will require transformational change in many colleges/schools of pharmacy. For most, it will require at least re-organizing change if not re-creating change. Due to the amount of change needed, a cultural transformation within the institution is likely to occur. Organizational culture is the shared set of assumptions that develop over time in a group and help to provide the group with a sense of stability and identity. Change that requires a group to rethink their assumptions or their identity typically leads to a culture change unless the group already has a culture that is flexible and may be more common in newer organizations.13

The leadership characteristics needed for transformational change such as the implementation of PL are different from those needed to lead other types of change. Executive leadership (“Big L”) is important for effective transformational change. A combination of charismatic and instrumental leadership has been shown to be effective in leading transformational change. Charismatic leadership generates energy and commitment and helps to direct individuals to accept new objectives, values, and aspirations. Instrumental leadership helps ensure people act in a manner consistent with the new goals. These two approaches are sometimes hard to find in one person as typically leaders are good at one side but not the other. This is where an executive leader needs to develop both a strong leadership team as well as faculty champions (“little l”) to help.20

Studies illustrate that leaders who are more effective at task-oriented behaviors are better at activities that mobilize and motivate during times of organizational change. This is particularly true when the mobilization requires motivation of both their own team members and other stakeholders. Person-oriented leaders tend to be better at communication types of activities. This would suggest that when putting together teams to help lead change, an executive leader should include a mix of leaders who are task and person-oriented.21 Other leadership skills found to be helpful during times of change include ability to coach, communicate, involve others, motivate, reward, and build teams.22 A study by Gilley and colleagues (2009) found that a leader’s ability to motivate others, communicate effectively, and build teams were the most significant in leading change effectively.22 Another part of leading effective change is the ability to promote the wellness of not only themselves but also those in the organization while undergoing the transformation. The next charge addresses this area.

CHARGE 2: PROMOTING WELLNESS FOR ALL

The Committee was charged with identifying and articulating the leadership and other competencies essential for faculty to be aware of and promote wellness for themselves, colleagues and students in health professions education. In addition to the literature specific to the Academy, the Committee considered empirical literature, publications put forth by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience and thought pieces from those on the front lines of clinician wellbeing efforts. Hereafter, the Committee briefly describes the constructs of wellness and wellbeing and the case for fostering wellbeing in the Academy. The Committee also describes the levels at which wellbeing should be fostered in the Academy. Integrated into the levels for consideration are wellbeing competencies.

The Case for Fostering Wellness and Wellbeing

Wellness and wellbeing are frequently used terms for which there are neither universally accepted definitions nor consensus on how many dimensions they encompass. Whereas wellness tends to be defined more in terms of health, wellbeing has been defined in a more holistic sense as “the presence of positive emotions and moods (eg, contentment, happiness), the absence of negative emotions (eg, depression, anxiety), satisfaction with life, fulfillment and positive functioning.23

The Committee approached the charge from the more holistic wellbeing perspective. Like wellness, wellbeing is routinely conceptualized across multiple domains. While admittedly not nuanced enough to capture every aspect of what people consider important, Gallup defines wellbeing (and categorizes it as such) as our love for what we do each day (Purpose Wellbeing), the quality of our relationships (Social Wellbeing), the security of our finances (Financial Wellbeing), the vibrancy of our physical health (Physical Wellbeing), and the pride we take in what we have contributed to our communities (Community Wellbeing). Alternatively, Ohio State University – a leader in fostering wellbeing in academic institutions – categorizes wellbeing across nine domains.24 Regardless of the number of pieces into which the “wellbeing pie” is sliced, a thriving wellbeing is desirable among pharmacy faculty, staff, and students.

Increasingly, both anecdotal and empirical evidence suggest that health professions students struggle with fatigue and burnout in one or more domains that could be considered counter to wellbeing.25-28 Stoffel and Cain’s recent review of the grit and resilience literature in the health professions reveals the dearth of information specific to pharmacy education.29 Overall, as compared to physicians and nurses, we know relatively little about wellbeing within the pharmacy profession.

The consequences of health care practitioner distress are far reaching and include decreases in provider fulfillment and self-care, increases in suicide and suicidal ideation, increases in medical errors, and decreases in health care quality.30,31 In 2017, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) established the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience in an effort to bring visibility to clinician burnout, improve the understanding of barriers to clinician wellbeing, and subsequently develop solutions to foster wellbeing among clinicians. Importantly, while previously mentioned clinician level consequences have been associated with burnout and distress, downstream negative patient outcomes have also been reported in the literature.32-34 Succinctly, there are important downstream consequences to poor provider wellbeing.

While empirical data are warranted to substantiate the relationship, there is likely an interdependence between pharmacy student and pharmacy faculty wellbeing. Evidence indicates burnout is common among pharmacy faculty.35 Anecdotally, conversations at AACP’s 2018 Fall Institute on Wellbeing pointed to the relationship between student and faculty wellbeing: when students struggle, faculty struggle and vice versa.

A Systems Approach to Fostering Wellbeing

Two documents guided this portion the Committee’s report: 1) the NAM Discussion Paper titled A multifaceted systems approach to addressing stress within health professions education and beyond; and 2) the Mayo Clinic Special Article titled Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout.36,37 Members of the Academy are encouraged to read both papers. While neither manuscript explicitly frames their recommendations/strategies as competencies, the Committee interpreted them from this perspective.

Depending on the characteristics of the college or school, the academic institution of which the college or school is a part could influence – either positively or negatively – the extent to which the competencies can be addressed. The Committee encourages colleges and schools of pharmacy to champion a culture of wellbeing. For purposes of this report, competencies that could have both an institutional and college/school level component are described at the College or School Administrator level. Recognizing the extent to which department chairs engage in both administrative and faculty roles, chair-specific competencies were developed by the committee. Applying the Charter on Physician Wellbeing which states, “approaches to address physician wellbeing are most effective when contextualized within efforts to enhance the wellbeing of all health care team members,” conversations about and efforts to foster wellbeing within the Academy should include staff.38 Staff are therefore also integrated into faculty, staff and student competencies. All competencies are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

College and School, Department Chair, and Faculty, Staff, and Student Wellbeing Competencies

College and School Administrators. Evidence suggests organizational factors are the primary drivers of burnout, including workload, efficiency, autonomy in work, alignment of individual and organizational values, social support/community at work, and meaning derived from work.36,39 Importantly, organizational promotion and allocation of resources to faculty, staff, and student self-care, without establishing a college or school organizational culture of wellbeing, can send the message that the faculty, staff, and students are the problem.36 Shanafelt and Noseworthy describe the unintended organizational consequences of framing wellbeing, or lack thereof, simply as a personal problem, including decreased work effort, decreased engagement, and increased turnover.40

The Department Chair. Many of the aforementioned competencies for colleges and schools are applicable at the department level. In the same manner that college and school administrators influence the culture of wellbeing at the college/school level, department chairs are uniquely positioned to positively (or negatively) impact the wellbeing of their faculty members and staff. The 2008-2009 AACP Joint Task Force on Faculty Workforce highlights the impact of department chairs on individual faculty wellbeing-related perceptions and outcomes.41

Students, Staff, and Faculty. Health professions education, including pharmacy school, is inevitably at times difficult and stressful. Whereas colleges, schools, and department chairs should promote a culture of wellbeing, students, staff, and faculty have a responsibility to care for themselves so that they may best care for others. This may include, but is not limited to, regular exercise, healthy eating, mindfulness, participation in university and college/school-sponsored wellbeing programming, and keeping communication lines with faculty, department chairs and college/school administrators open relative to identifying points of (increased) stress and the creation of events and activities to nourish wellbeing.

CHARGE 3: BUILDING TOOLS FOR LIFELONG LEARNING

The 2018-19 Committee was asked to further develop the work of the 2017-2018 Academic Affairs Committee and create educational programs that AACP can implement as CPD certificate programs across the academy. In their report the 2017-18 Academic Affairs Committee recommended that the academy work to foster lifelong learning in faculty, specifically by developing programs and tools for them to use in their continuing professional development. President Allen charged this year’s committee to identify specific areas and programs by which AACP can address this recommendation. In the Committee’s recommendations and suggestions to address Charges 1 and 2 above, there are specific topics identified that not only address those charges but also provide guidance for the academy on directions for faculty lifelong learning and continuing professional development.

This year’s committee also identified other topic areas important to consider for faculty development. These are listed in the Recommendations below. When examining these and the topics for Charges 1 and 2, AACP and the colleges/schools should consider a variety of delivery modalities to best meet the needs of the academy. Education and training on some of these topics may be best provided through traditional presentations at Association meetings; others may be broad enough to be the focus of an annual institute; still others may be efficiently delivered in webinar format or standard asynchronous on-line delivery.

CONCLUSION

The U.S. healthcare system needs to change substantially to achieve the aims of better health outcomes for individuals and populations at an affordable level of resource consumption. This requires leadership in practice and education as well as attention to the well-being of clinicians, faculty and learners. The Committee sets forth models for change management and a series of policy statements, recommendations and suggestions for how AACP and its members can work together as agents of change to assure the profession’s rightful place in a reformed care delivery system.

POLICY STATEMENTS, RECOMMENDATIONS AND SUGGESTIONS

Policies

The 2018-19 Academic Affairs Committee reaffirms the continued relevance of the following AACP policies:

AACP supports and encourages the implementation of on-going program assessment processes at member institutions for the purpose of enhancing the quality of educational programs and student services. (Academic Affairs Committee, 2004)

AACP supports interdisciplinary and interprofessional education for health professions education. (Professional Affairs Committee, 2002)

AACP encourages schools and colleges of pharmacy to proactively promote overall wellness and stress management techniques to students, faculty, and staff. (Student Affairs Committee, 2017)

The 2018-19 Academic Affairs Committee recommends amending the following policy statement:

AACP encourages a culture of intellectual curiosity, entrepreneurship, and nurturing agents of change in schools and colleges of pharmacy. (Original source: Professional Affairs Committee, 2013)

The 2018-19 Academic Affairs Committee recommends the following new policy statements:

AACP supports educational reform to adopt the framework of personalized learning in curricula to meet the advances in healthcare delivery.

AACP encourages timely transformation of educational models and creates a culture of change enabling responsiveness, flexibility, and effective assessment of the impact of leaders, faculty, staff, and students on healthcare delivery.

AACP supports the promotion of pharmacists as healthcare professionals that have the ability to evaluate, analyze, and synthesize patient- and population-based data.

AACP affirms that fostering leader, faculty, staff, and student wellbeing is a vital responsibility of the academy and individual schools and colleges.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 1: AACP should develop and offer programs in the following areas:

‐ Incorporating personalized learning into education

‐ Becoming a facilitator

‐ Teaching faculty how to facilitate learning of analysis, synthesis, and 21st century skills

‐ Conducting work on the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

‐ Curricular transformation

Recommendation 2: AACP should facilitate the discussion and research required to define quality metrics for educational frameworks.

Recommendation 3: AACP should also consider the development of programs on:

‐ Applying wellbeing dimensions to self, leadership, learner, and patients

‐ Factors affecting student wellbeing (systems/environment emphasis)

‐ Evaluating student/faculty/staff wellbeing (how to do it and what to do with it)

Recommendation 4: AACP should develop programs for faculty that focus on leading change from a grassroots, small “l” leadership perspective.

Recommendation 5: Building on a commitment to lifelong learning for faculty, AACP should develop programs that support faculty in developing and carrying out goal-oriented career strategies.

SUGGESTIONS

Suggestion 1: Schools and colleges of pharmacy should develop innovative ways to implement personalized learning into pharmacy education, including development of faculty champions.

Suggestion 2: Schools and colleges of pharmacy should consider ways to flatten the accelerating cost of education curve to reduce student debt burden.

Suggestion 3: Schools and colleges of pharmacy should develop and evaluate wellbeing programs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilley A, McMillan HS, and Gilley JW. Organizational change and characteristics of leadershp effectives. J of Leadership and Organizational Studies. 2009;16(1):38-47. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nadler DA, Tushman ML. Beyond the charismatic leader: leadership and organizational change. California Management Review. 1990;32(2):77-97. [Google Scholar]

- 3.LaClair J, Rao R. Helping employees embrace change. The McKinsey Quarterly; 2002;4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.A conceptual model for managed culture change. In: Schein EH. Organizational Culture and Leadership 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2004: 319-336. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schafer MA, Sandau LE, Diedrick L. Evidence-based practice models for organizational change: overview of practical applications. J of Adv Nurs. 2012; 1197-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hislmaier E, Senger A. The 2017 health insurance exchanges: major decrease in competition and choice: The Heritage Foundation. Published January 30, 2017. https://www.heritage.org/health-care-reform/report/the-2017-health-insurance-exchanges-major-decrease-competition-choice. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- 7.Institute of Medicine. Best of Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America. Published 2012. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2012/Best-Care-at-Lower-Cost-The-Path-to-Continuously-Learning-Health-Care-in-America.aspx Accessed December 27, 2018.

- 8.Department of Health and Human Services. Reforming America’s Healthcare System Through Choice and Competition. Published 2017 https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Reforming-Americas-Healthcare-System-Through-Choice-and-Competition.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2018.

- 9.Almeida W. How AI is transforming healthcare and solving problems in 2017. Healthcare IT News . Published November 9, 2017. https://www.healthcareitnews.com/slideshow/how-ai-transforming-healthcare-and-solving-problems-2017. Accessed April 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Bright Future of Pharmacies. The Medical Futurist . August 17, 2016. http://medicalfuturist.com/the-bright-future-of-pharmacies/. Accessed April 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Artiga S, Hinton E. Beyond health care: the role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. May 10, 2018. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity. Accessed April 2, 2019.

- 12.Muhlestein D. Winfield L. NEJM Catalyst. Preparing a new generation of physicians for a new kind of health care. February 28, 2018. https://catalyst.nejm.org/preparing-new-generation-physicians-new-health-care. Accessed April 2, 2019.

- 13.A conceptual model for managed culture change. In: Schein EH. Organizational Culture and Leadership 3rd ed:2004: 319-336. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rojansaraot S, Milone A, Balestrieri R, Pittenger AL. Personalized learning in an online drugs and US healthcare system controversies course. Am J Pharm Educ . 2018;82(8):Article 6391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maseleno A, Sabani N, Huda M, Ahmad R, Jasmi KA, Basiron B. Demystifying learning analytics in personalised learning. Int J Engineer Tech . 2018;7(3):1124-1129. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duggan K. Personalized learning implementation framework: 25 focus areas for schools and districts. Education Elements 2018. https://www.edelements.com/hubfs/Personalized%20Learning%20Implementation%20Framework%20WP%202017/Personalized-learning-implementation-framework-white-paper-2017.pdf?hsCtaTracking=a9511897-2b92-4547-bb44-4134f3bf9cfb%7C2f5b9425-6d4a-4304-8cd3-28f7b8c145ec. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- 17.Bingham AJ, Pane JF, Steiner ED, Hamilton LS. Ahead of the curve: implementation challenges in personalized learning school models. Ed Policy. 2016;1-36. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy B, Schauer K. Journey to personalized learning: bright future – a race to the top-district initiative in Galt Joint Union Elementary School District. San Francisco, CA: WestEd, 2017. https://www.wested.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/resource-journey-to-personalized-learning-1.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johns S, Wolking M. The core four of personalized learning: the elements you need to succeed. Education Elements, 2016. https://www.edelements.com/hubfs/Core_Four/Education_Elements_Core_Four_White_Paper.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadler DA, Tushman ML. Beyond the charismatic leader: leadership and organizational change. California Management Review. 1990;32(2):77-97. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Battilana J, Gilmartin M, Sengul M, Pache AC, Alexander JA. Leadership competencies for implementing planned organizational change. Leadership Q . 2010;21:422-438. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilley A, McMillan HS, Gilley JW. Organizational change and characteristics of leadership effectiveness. J Leadership and Organizational Studies. 2009;16(1):38-47. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL). Published 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/wellbeing.htm. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- 24.The Ohio State University. Nine Dimensions of Wellness. Published 2019. https://swc.osu.edu/about-us/nine-dimensions-of-wellness/. Accessed February 1, 2019.

- 25.Kulig CE, Persky AM. Transition and student well-being: why we need to start the conversation. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(6):Article 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ray ME, Coon JM, Al-Jumaili AA, Fullerton M. Quantitative and qualitative factors associated with social isolation among students from graduate and professional health science program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;83(7):Article 6983 https://www.ajpe.org/doi/pdf/10.5688/ajpe6983. Accessed April 2, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bullock G, Kraft L, Amsden K, et al. . The prevalence and effect of burnout on graduate healthcare students. Can Med Educ J. 2017;8(3):e90-e108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. . Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoffel JM, Cain J. Review of grit and resilience iterature within health professions education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(2):Article 6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salvagioni DAJ, Melanda FN, Mesas AE, Gonzalez AD, Gabani FL, Andrade SM. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: a systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0185781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. . Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams ES, Manwell LB, Konrad TR, Linzer M. The relationship of organizational culture, stress, satisfaction, and burnout with physician-reported error and suboptimal patient care: results from the MEMO study. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007;32(3):203-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1294-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Ibiary SY, Yam L, Lee KC. Assessment of burnout and associated risk factors among pharmacy practice faculty in the United States. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(4):Article 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Coffey DS, Eliot K, Goldblatt E, et al. A Multifaceted Systems Approach to Addressing Stress Within Health Professions Education and Beyond. [Paper] Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine;2017.

- 38.Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shanafelt TD, Mungo M, Schmitgen J, et al. . Longitudinal study evaluating the association between physician burnout and changes in professional work effort. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(4):422-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shanafelt TD, Gorringe G, Menaker R, et al. . Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):432-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Desselle S, Pierce G, Crabtree B, et al. . Pharmacy faculty workplace issues: findings from the 2009-2010 COD-COF Joint Task Force on Faculty Workforce. Am J Pharm Educ . 2011;75(4):Article 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]