Abstract

Objective. To examine and compare the prevalence of mental health problems, help-seeking attitudes, and perceptions about mental health problems among US pharmacy and medical students.

Methods. A cross-sectional analysis was conducted using existing, anonymous survey data collected in the Healthy Minds Study during the 2015-2016 academic year. The analysis included 482 students (159 pharmacy students and 323 medical students) from 23 institutions in the United States. Analyzed topics included demographic characteristics, mental health status and symptoms, substance abuse, stigma related to mental health, help-seeking behaviors and attitudes, and mental health treatment perceptions.

Results. Pharmacy and medical students experienced similar rates of depression (18% met clinical cut-offs), but pharmacy students were more likely to meet clinical cutoffs for anxiety (21% vs 11%). Pharmacy students were less likely to seek help from student counseling services (only 11% vs 49%) and also less likely to know where to seek help on campus if needed. Pharmacy students also reported having higher levels of stigma regarding mental health treatment.

Conclusion. There are differences between pharmacy and medical students with regards to their experience of mental health symptoms, willingness to seek help, and perception of stigma. Despite the small sample, this analysis of national data indicates that opportunities exist to improve campus-based mental health education and offerings for pharmacy and medical students.

Keywords: student mental health, pharmacy students, medical students, mental health stigma, help-seeking

INTRODUCTION

Heightened attention is being paid to the growing “campus mental health crisis,” with campus-based counseling and mental health providers noting an increase in the prevalence and severity of problems among students at colleges and universities.1-3 Consequently, researchers and campus stakeholders are examining prevalence rates of mental health problems, as well as risk factors across groups of students, including by academic fields. For instance, studies show that students in the health professions fields, including students in pharmacy and medical degree programs, face multiple stressors, including academic overload, pressure to succeed, and competition, as well as an academic culture that may be at odds with student mental health and well-being.4,5 Studies have examined mental health problems and attitudes about help-seeking among medical students, but less is known about these concerns among pharmacy students.2,6-10 Research in this area is needed to inform the development of specific, tailored solutions to address the needs of these groups of students.2 This study contributes to a small but growing body of literature that examines symptoms, experiences with, and attitudes about mental health and help-seeking among pharmacy and medical students by exploring the differences across these student groups.

Pharmacy and medical students have significant mental health needs. Studies suggest that medical students overall, as compared with members of the general population of similar age, experience significantly more stress and lower mental health quality of life, with burnout affecting up to 50% of US medical students.10,11 The prevalence of mental health and substance-related problems among medical students is quite high, ranging at varying times during their clinical training from 17% to 58%.6,7,12-14 Studies have shown that between 19% and 44% of medical students experience symptoms of anxiety and about 27% experience symptoms of depression, although estimates vary widely across studies (18% to 58%).6-8

Stress, anxiety, and depression are also prevalent among pharmacy students, especially female pharmacy students.15 Ibrahim and Abdelreheem found high levels of depression (51%) and anxiety (29%) among pharmacy students, yet these levels were significantly less than levels of depression (58%) and anxiety (48%) found among medical students.6 In a study of pharmacy students and recent pharmacy graduates, Bell and colleagues found that about 6% of pharmacy students had ever suffered from any mental illness.16 Further, a recent study of pharmacy residents found that 40% self-reported depression during their residency, a rate comparable to that found among medical students and the general college student population.4,17 This psychological distress, including anxiety and depression, negatively impacts students’ happiness and well-being.15

Suicidality among medical students and pharmacy is also of concern. Over 25% of medical students have ever considered suicide, with 11% having seriously contemplated suicide within the last year.8,18 Less is known about rates of suicide and suicide ideation among pharmacy students. One study found that 12% of pharmacy students had experienced suicidal ideation, compared to 13% among medical students, and noted a trend of hopelessness increasing in pharmacy students’ second year compared to in the first year of the program.19 A more recent study revealed that about 22% of pharmacy residents reported experiencing suicidal ideation.17

Substance use is prevalent among medical students, with 17%-34% of medical students reporting excessive alcohol use or binge drinking,12,20,21 and about one third of medical students using illicit substances.21 Studies on problematic substance use among pharmacy students show similar patterns, with 25% of students exhibiting excessive drinking, 21% of pharmacy students indicating marijuana use in the preceding year, and 41% reporting past-year use of controlled substances without a prescription.22 These trends appear to be worsening across all healthcare students.5

Many health professions students may feel that their stress is associated with academic pressure and may not view that as a reason to reach out for help, especially if there are concerns that seeking help will affect or jeopardize their academic standing.9,23 Medical students may be less likely to seek help from campus-based services due to concerns around confidentiality, especially when seeking help for stigmatized conditions, including mental health problems.7,23 Among pharmacy residents, a perceived need for mental health services exists, with 26% indicating they believe they would benefit from mental health resources.17 However, less is known about the help-seeking attitudes and behaviors of pharmacy students.24 Additional research is needed regarding the prevalence of mental health problems, attitudes towards help-seeking, and attitudes about mental health problems in general among pharmacy students.

With this project, we examined the prevalence of and attitudes about mental health problems, as well as students’ attitudes towards help-seeking and the efficacy of mental health services (for oneself or others) among a sample of pharmacy students and medical students within the United States. This is an exploratory analysis about a topic that has received little attention in the literature. Among these two student groups, more is known about medical students than pharmacy students, so we structured our analyses to also compare differences across these groups. We seek to simply describe the differences found without hypothesizing about the nature of these differences. Our specific study objectives were as follows: to examine and compare, among a sample of pharmacy students and medical students within the United States, the prevalence of positive mental health and mental health problems including anxiety, depression and other diagnoses; prevalence of mental illness diagnosis; prevalence of non-suicidal self-harm, suicidal ideation and number of suicide attempts; prevalence of illegal substance use; prevalence of receiving treatment for mental health issues; prevalence of help-seeking behaviors; perceptions of the helpfulness of counseling/therapy and medication for treatment of depression, and attitudes towards people with mental illness.

METHODS

This study was a cross-sectional analysis, completed by the authors in 2018 using existing, anonymous data collected through the 2015-2016 Healthy Minds Study.25 The annual, internet-based study conducted by the University of Michigan Healthy Minds Network25 was administered at multiple colleges and universities across the United States. Among institutions with less than 4000 students, all were invited to participate, while at larger universities a random sample of 4000 students was invited. Participating institutions provided the email addresses of enrolled students who were at least 18 years of age to the Healthy Minds researchers. Students received an email invitation from the researchers with a link to the online survey instrument. To address response bias, sampling weights were created to develop a representative sample for each school based on gender, race, grade level, and grade point average (additional information about weighting for response bias can be found in the Healthy Minds Study 2015-2016 Report).26 While the survey was weighted to be representative of the participating schools, it was not nationally representative of all schools in the United States.

For the current research project, participants’ data from the Healthy Minds Study were included if the participants had indicated their degree program was a doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) program. Participants’ data were also included if they had indicated their field was pharmacy and they were enrolled in a PhD program. The data of participants who chose medical doctor (MD) in response to the question, “In what degree program are you currently enrolled?” were included as medical students. The data of participants were also included if the participant had indicated they were pursuing an MD/PhD degree program instead of an MD program. Participants’ data were excluded if they had indicated BA/MD as their degree program as it was unclear at which point these students were in terms of the MD portion of their programs (n=1). Data for participants whose current enrollment information was missing (n=2) were also excluded. For the 2015-2016 academic year cohort, 23 schools had participated in the Healthy Minds Study, for a full sample of 34,299 students. The final sample for the current study, based on the inclusion criteria listed above, consisted of data for 482 students from 17 of the 23 participating institutions, with 159 pharmacy students and 323 medical students. The Healthy Minds Study had been approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of each participating institution. The current study was approved by the Northeast Ohio Medical University IRB as exempt human subjects research.

The analyses presented here were conducted using sample weights which were developed by the Healthy Minds researchers to address response bias. We conducted descriptive analyses including calculation of sample-weighted means and percentages. Bivariate tests were conducted that accommodate the nature of weighted data. Adjusted Wald tests were conducted to test for differences between weighted means in place of independent samples t tests. Pearson design-based F tests, which provide corrected weighted chi square test statistics, were performed to compare weighted percentages. All analyses were conducted using Stata 15.

The measures analyzed in the current study included demographic items (gender, sexual orientation, age, ethnicity, race). Positive mental health was assessed in the Healthy Minds Study using the eight-item Flourishing Scale which measures participants’ positive perceptions about their relationships, self-esteem, and optimism.27 Participants were asked to indicate their agreement on a seven-point Likert scale with statements such as “I am optimistic about my future” and “People respect me.” Higher scores indicate greater positive mental health. Depression symptoms were assessed using the nine-item Patient-Health-Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9),28 which was created to quickly screen patients for depression in primary care and other clinical settings. The PHQ9 is a reliable and valid screening tool with high levels of sensitivity and specificity for detecting major depression.29 Respondents were asked to rate the frequency in the prior two weeks that they have had problems, such as “little interest or pleasure in doing things,” on a four-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “nearly every day.” Higher scores indicate increased depression symptoms. An additional variable was created to indicate whether the clinical threshold score for major depression (greater than or equal to 10) had been met. Anxiety was assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item (GAD-7). The GAD-7 was developed using a large, primary care clinical sample to screen for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), the most prevalent anxiety disorder in the general population.30 The GAD-7 is a validated tool which asks participants to indicate on a four-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “nearly every day” the frequency they have experienced problems such as “feeling nervous, anxious or on edge” over the past two weeks. Higher scores represent increased anxiety, and the GAD-7 also uses a clinical threshold score of greater than or equal to 10 to screen for GAD. A variable was created to indicate whether participants had met the clinical threshold for anxiety. Respondents were asked if they had ever been diagnosed by a health professional with depression, anxiety, attention disorder or learning disability, eating disorder, psychosis, or substance abuse disorders. Additional questions measured suicidal ideation in the past year, suicide plans, and suicide attempts in the past year.

Participants in the Healthy Minds Study were asked to indicate alcohol use and frequency of binge drinking, defined as having four or more drinks on one occasion in the past two weeks, in addition to quantities of cigarettes smoked in the past 30 days. An additional item measured past 30-day use of other substances including: marijuana, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines, other stimulants without a prescription, ecstasy, or any other drugs or controlled substances without a prescription.

One item in the Healthy Minds Study assessed prior 12-month use of any of the following prescription medications: psychostimulants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antianxiety medications, mood stabilizers, or sleep medications. Participants who indicated prior 12-month use of prescription mental health medication were then asked to indicate reasons for use, including mental or emotional health, other health reasons, academic performance, recreation/fun or other reasons. These respondents were also asked to indicate what type of health professional had prescribed the medication.

Participants’ knowledge of where to seek mental health treatment was measured in the Healthy Minds Study via agreement with the following statement, “If I needed to seek professional help for my mental or emotional health, I would know where to go on my campus,” with lower scores indicating greater agreement. Additional questions assessed formal help-seeking, or counseling/therapy, within the past 12 months, including: use of services in past 12 months, current use, and location of services. To assess informal help-seeking, participants were asked whether they had received emotional counseling or support from sources such as friend, roommates, and family, and if yes, the perceived helpfulness of the support. Respondents were also asked, “If you had a mental health problem that you believed was affecting your academic performance, which people at school would you talk to” with options such as professor, academic advisor, and dean. Finally, we included a measure asking, “During this school year have you talked with any academic personnel (such as instructors, advisors, or other academic staff) about any mental health problems that were affecting your academic performance?” and if so, participants indicated the perceived supportiveness of the school’s response.

Perceptions regarding treatment efficacy were assessed in the Healthy Minds Study with helpfulness ratings of medication and counseling/therapy for clinically depressed individuals of the same age as the respondent. Lower scores indicated increased perceptions of helpfulness.

Stigma regarding mental health treatment was measured by the Healthy Minds Study via agreement with the following statements, “Most people think less of a person who has received mental health treatment,” and “I would think less of a person who has received mental health treatment” with lower scores representing more agreement.

RESULTS

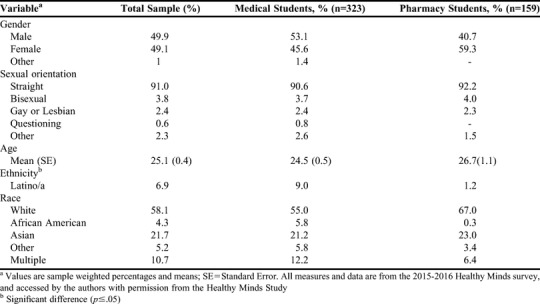

Data from the Healthy Minds Study on 159 pharmacy students and 323 medical students representing 17 institutions were included in our study for analysis. Pharmacy and medical students were similar demographically (Table 1), however, significantly more medical students than pharmacy students were of Latino/a ethnicity (9.0% vs 1.2%, respectively). Male and female students were equally represented in the total sample (49.9% male). Participants were predominantly straight (91.0%) and white (58%), with an average age of 25 years.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Medical and Pharmacy Students (N=482)

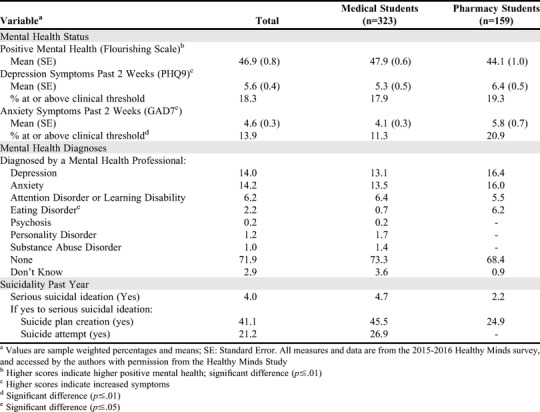

Our first study objective was to explore the prevalence of positive mental health as well as mental health concerns, including anxiety, depression, and other mental health problems, among US medical students and pharmacy students (Table 2). On average, medical students reported better positive mental health, as indicated by significantly higher scores on the Flourishing Scale, than pharmacy students (47.9 vs 44.1, p<.01). We found that pharmacy students and medical students were similar in terms of the prevalence of depression symptoms in the past two weeks, with 18.3% of the total sample at or above the clinical cut-off for depression (Table 2). A significantly larger percentage of pharmacy students than medical students met the clinical threshold for anxiety (20.9% vs 11.3%, p=.01). Similar percentages of pharmacy students and medical students reported mental health diagnoses made by a mental health professional. Nearly 14% (13.9%) of the total sample reported a depression diagnosis and 14.2% also indicated having been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, with 71.9% reporting no diagnoses (study objective 2). Just over 4% of the total sample reported serious suicidal ideation in the past year. Of the group reporting serious suicidal ideation, 41.1% had created a plan and 21.17% attempted suicide (study objective 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of Mental Health Status, Diagnoses and Suicidality Among Medical and Pharmacy Students (N=482)

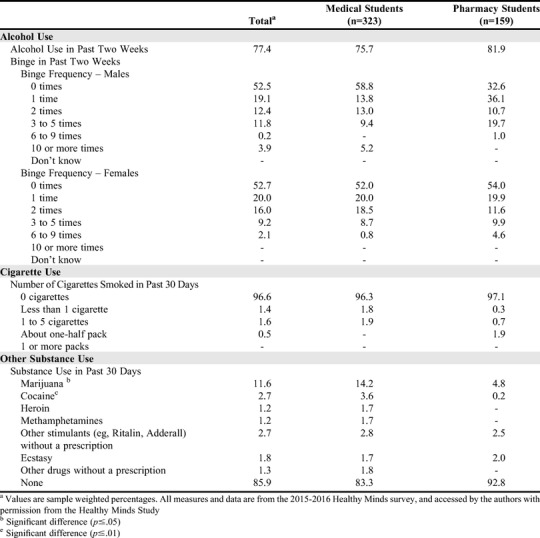

Most students had used alcohol in the past two weeks (77.4% of total sample) and 47.5% of male and 47.3% of female students reported binge drinking at least once in the past two weeks. Only 3.5% of the total sample reported smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days. There were significant differences between medicine and pharmacy students in terms of marijuana and cocaine use in the previous 30 days. Over 14% (14.2%) of medicine students compared to 4.8% of pharmacy students used marijuana (p=.03), and 3.6% of medicine students used cocaine compared to fewer than 0.2% of pharmacy students (p=.01) (study objective 4; Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of Substance Use Among Medical and Pharmacy Students (N=482)

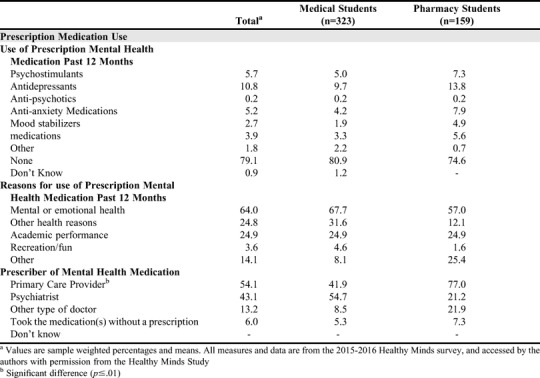

The most commonly reported prescription mental health medication used in the past 12 months were antidepressants (10.8% of total sample). Of those who reported prescription mental health medication use in the past 12 months, most indicated using the medication for mental or emotional health purposes (64% of total sample). While 22.8% of those who used prescription mental health medication in the past 12 months reported using medication for other health reasons, 24.9% also revealed using the medication for academic reasons. Of those who used prescription mental health medication in the past 12 months, pharmacy students were more likely than medical students to obtain the prescription from a primary health care physician (77% vs 42%, p<.01, study objective 5; Table 4).

Table 4.

Prevalence of Prescription Medication Use Among Medical and Pharmacy Students (N=482)

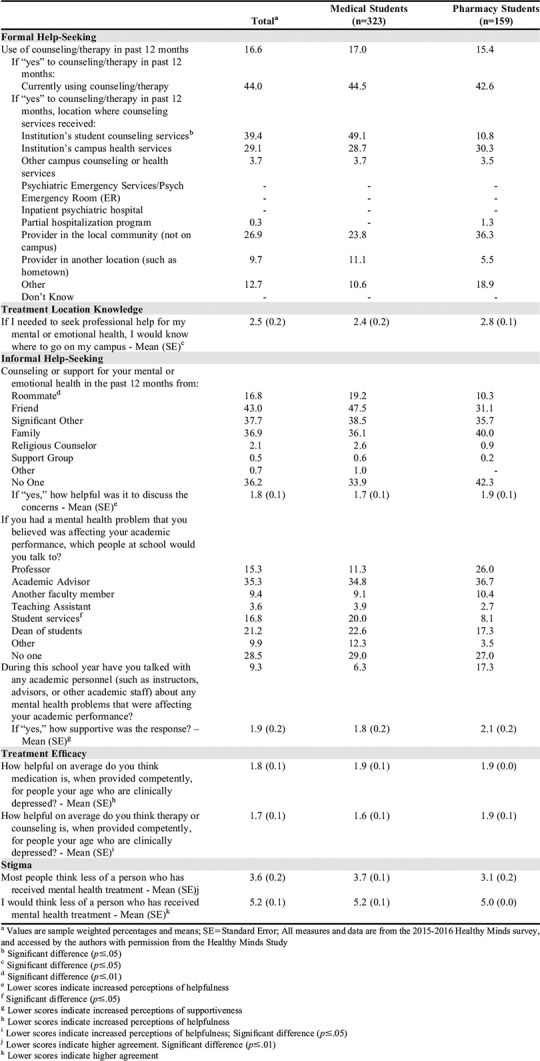

Approximately 16.6% of the total sample reported using counseling/therapy in the past 12 months. Of those who used counseling, 44% were currently receiving services. Compared to medical students, pharmacy students were significantly less likely to receive treatment from their institution’s student counseling services (10.8% vs 49%, p=.02, study objective 5; Table 5). With regards to study objective 6 (Table 5), pharmacy students were also less likely than medical students to know where to seek on-campus professional help if they were to need it (p=.05). Collectively, pharmacy students and medical students were most likely to speak with friends (43%), significant others (37.7%), family members (36.9%), and/or roommates (16.8%) in the past 12 months for mental or emotional health support. However, 36.18% of the total sample reported speaking with no one for informal support. When asked who they would speak to at their school if they had a mental health problem affecting their academics, most students indicated they would speak with their academic advisor (35.3% of total sample). However, over a quarter of the total sample (28.4%) indicated they would not speak with any academic staff member. Finally, only 6.3% of medical students and 17.3% of pharmacy students indicated they have spoken with academic personnel regarding mental health concerns affecting their performance (p=.07).

Table 5.

Prevalence of Mental Health Help-Seeking Experiences, Knowledge, and Attitudes Among Medical and Pharmacy Students (N=482)

Pharmacy students were significantly less likely to agree that counseling/therapy is helpful for treating clinically depressed individuals their own age (p=.02; study objective 7; Table 5). Finally, pharmacy students were significantly more likely than medical students to agree with the statement, “Most people think less of a person who has received mental health treatment” (p<.01; study objective 8; Table 5).

DISCUSSION

In our analysis of data from the Healthy Minds Study, we found that among pharmacy and medical students there was a high prevalence of psychological distress, including depression and anxiety, at levels comparable to other research.6,7,12,14 About 28% of the entire sample reported having some sort of psychiatric diagnosis by a professional. The two student groups reported comparable levels of depressive symptomatology (about 18%) and did not differ in the prevalence of suicide ideation (4% for total sample). These prevalence rates of depression or depressive symptoms are lower than what has been reported for medical students (27% for depression and 11% prevalence for suicidal ideation8), but within reported ranges across other undergraduate and graduate college students as reported in previous Healthy Minds Study cohorts (8%-46%).2 When comparing pharmacy students and medical students, others found no difference in rates of depression or suicide ideation.19 Though low, the prevalence of suicidal ideation reported by students who participated in the Healthy Minds Study was comparable to the ranges reported across all undergraduate and graduate academic fields (4%-11%),2 and underscores the importance of early identification of suicidal ideation, symptoms of hopelessness and depressive symptoms in these students.

Overall, 13.89% of the total sample met the clinical cutoff for anxiety, a rate comparable to the estimated prevalence of anxiety among undergraduate (16%) and graduate students (13%).1 Of interest, the current study found significantly more pharmacy students than medical students met the clinical cutoff for anxiety (20.89% vs 11.27%, respectively), while medical students scored significantly higher on the mental health flourishing scale. This finding is in contrast with other comparisons between medical and pharmacy students, which suggest higher rates of depression and anxiety among medical students than pharmacy students,6 but aligns with others that have found that pharmacy students are at greater risk for psychological distress compared to medical students and other health professions students.13,31

Substance use, comparable to what has been found in other studies, was prevalent within this sample.20,21 Alcohol use was common among both groups (about 77%), and about 47% of the sample had engaged in binge drinking at least once in the prior two weeks. Very few pharmacy or medical students reported smoking (3.5%). Only about 14% of the sample used any illicit substances, but we found a significant difference between pharmacy students and medical students, with medical students being significantly more likely to use marijuana (14.2% vs 4.8%) and cocaine (3.6% vs 0.2%) compared to pharmacy students. Among medical students, the prevalence rate reported here for cocaine use is higher than what has been reported in other studies (less than 1%).20

Finally, of note was the prevalence of both pharmacy and medical students in the Healthy Minds Study who were at risk of abusing mental health prescription medications. Most students (79.1%) did not use any mental health prescription medications. However, among those who did report using prescription medications, 24.9% of students reported using them for academic performance, and an additional 3.6% reported recreational use. Given the high demands placed on pharmacy and medical students to perform academically, and the volume of work associated with both degree programs, administrators should be cognizant of the risk of inappropriate stimulant use and foster healthier coping strategies and support systems for students.22,32

Despite the heightened prevalence of anxiety among pharmacy students, this student group was less likely to receive counseling services on campus and less likely to know where to seek on-campus help. Approximately 19% of pharmacy students score at or above the clinical threshold for depression, and nearly 21% scored at or above the clinical threshold for anxiety. About 15% of pharmacy students reported receiving any formal mental health treatment within the past year. Furthermore, 28.5% of the total sample of pharmacy and medical students reported that they would not seek help on campus from anyone for mental health problems that were affecting academic performance. This is a higher prevalence rate compared to a general sample of university students (16%).33

Research is needed to understand specific barriers to help-seeking among pharmacy students and medical students. However, these findings suggest a need for schools to engage in efforts that normalize help-seeking and demystify the process. Educational and promotional campaigns to describe the location and availability of services, as well as the potential benefit to the student of receiving mental health services, may increase help-seeking behaviors and reduce stigmatizing attitudes. The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Student Affairs Standing Committee recently charged institutions to focus on student wellness by promoting self-awareness, resiliency, and well-being.4 To address concerns of confidentiality, which may be problematic for students who are concerned with licensure requirements, colleges and universities may want to forge collaborative partnerships with the community mental health and addictions treatment system to connect students to practitioners who are not affiliated with their school.9

Finally, compared to medical students, pharmacy students who participated in the Healthy Minds Study seemed to perceive therapy/counseling as less helpful for clinically depressed people their own age, and had more stigmatized perceptions that most people would think less of a person who sought help for mental health reasons. The more negative views of pharmacy students towards therapy/counseling and people who receive treatment for mental health reasons suggest a potential opportunity for stigma reduction and educational campaigns on campus. Studies on effective stigma reduction efforts have shown that programming that emphasizes personal contact with people who have stigmatized conditions (eg, mental illness) are most effective at changing attitudes.34 Several resource centers exist to raise awareness of mental health issues, suicide prevention and stigma reduction efforts on college campuses. Such programs, including Active Minds and U Bring Change 2 Mind, as well as resources available through the JedFoundation, ULifeline, and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, among others, may be useful for framing such programing. However, while many of these campus resources are targeted towards the general college campus population, medical and pharmacy schools may need to tailor the content, structure, and emphases of these programs to meet the specific needs of medical students and pharmacy students. This is an area for future research and program development.

There are several limitations to this exploratory study. First, we report data from approximately three times as many medical students as pharmacy students, despite during the academic year 2015-2016, there being only a quarter fewer US pharmacy students than medical students.35,36 Additionally, the numbers of medical students (n=323) and pharmacy (n=159) students included in the current research are very small compared the total number of US pharmacy student and medical student enrollees during the academic year 2015-2016 (63,464 and 86,599, respectively).35,36 Likewise, the current research includes data from only 23 schools, while there are 143 accredited US pharmacy schools and 154 accredited US medical schools.37,38 Further, while the data was weighted to be representative of the full populations at the 23 schools, it was not weighted to be representative of US medical students and pharmacy students, in general. However, gender and racial/ethnic distributions for US medical school enrollees reveal very similar percentages to the weighted data reported in the current study.39 Gender breakdowns for US pharmacy school enrollees are also similar to the percentages reported in the current study.35 However, compared to US pharmacy school enrollees, Whites were overrepresented and Blacks underrepresented in the weighted percentages.

Future research should continue to examine these topics, especially among pharmacy students, using larger, more representative samples. Additionally, multivariate analyses should be conducted to understand the complex relationships among these issues to undercover areas for possible intervention. For example, the multivariate association should be modeled between stressful conditions of health professions education for pharmacy students and medical students with psychological distress, including depression and anxiety. A stress process framework may illuminate factors that influence mental health of pharmacy students and medical students, as well as identify specific coping resources (eg, social support, personal mastery) or coping mechanisms (eg, exercise31) that can be used to mitigate the harmful effects of stress. Using a more representative sample, future research should also examine attitudes regarding and barriers to help-seeking among women and minority students, as these group have expressed heightened concern about academic vulnerability, stress and disclosing personal health conditions within academic settings.6,7 It was beyond the scope of this study to explore the extent to which the attitudes held by pharmacy students influenced help-seeking behavior. Future research should examine the associations between attitudes about treatment efficacy, stigmatizing attitudes and help-seeking behavior among pharmacy students and medical students.

CONCLUSION

Despite the limitations associated with the current research, this work, based on data from the Health Minds Study, is among the first explorations into the mental health symptoms, formal and informal help-seeking, and attitudes and perceptions regarding help-seeking among pharmacy students. This study also confirms and extends general knowledge regarding these topics among medical students and includes one of the first comparisons between US pharmacy and medical students in these areas. The present analysis confirms that both US pharmacy and medical students experience significant mental health needs and that in some instances these needs are more profound among pharmacy students. While more extensive and generalizable research is needed, this work demonstrates that, particularly among pharmacy students, opportunities exist to evaluate and expand campus-based mental health education and services.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the team from the Healthy Minds Study for their assistance in accessing the data for this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eisenberg D, Gollust SE, Golberstein E, Hefner JL. Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(4):534-542. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipson SK, Zhou S, Wagner B, Beck K, Eisenberg D. Major differences: variations in undergraduate and graduate student mental health and treatment utilization across academic disciplines. J College Stud Psychother. 2016;30(1):23-41. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2016.1105657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz KJ. The crisis in college and university mental health. Psychiatr Times. 2009;(Oct):32-34. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller ML, Boyer C, Emerson MR, et al. Report of the 2017-2018 student affairs standing committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(7):Article 7159. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tavolacci MP, Delay J, Grigioni S, Déchelotte P, Ladner J. Changes and specificities in health behaviors among healthcare students over an 8-year period. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):1-18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibrahim MB, Abdelreheem MH. Prevalence of anxiety and depression among medical and pharmaceutical students in Alexandria University. Alexandria J Med. 2015;51(2):167-173. doi: 10.1016/j.ajme.2014.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts LW, Warner TD, Lyketsos C, Frank E, Ganzini L, Carter D. Perceptions of academic vulnerability associated with personal illness: a study of 1,027 students at nine medical schools. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(1):1-15. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.19747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students. JAMA. 2016;326(21):2214-2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brimstone R, Thistlethwaite JE, Quirk F. Behaviour of medical students in seeking mental and physical health care: exploration and comparison with psychology students. Med Educ. 2007;41(1):74-83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among US and Canadian medical students. Acad Med. 2006. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenberg D, Hunt J, Speer N. Help seeking for mental health on college campuses: review of evidence and next steps for research and practice. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2012;20(4):222-232. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2012.712839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahlin M, Nilsson C, Stotzer E, Runeson B. Mental distress, alcohol use and help-seeking among medical and business students: a cross-sectional comparative study. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(92). doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henning K, Ey S, Shaw D. Perfectionism, the impostor phenomenon and psychological adjustment in medical, dental, nursing and pharmacy students. Med Educ. 1998;32(5):456-464. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niemi PM, Vainiomäki PT. Medical students’ distress - quality, continuity and gender differences during a six-year medical programme. Med Teach. 2006;28(2):136-141. doi: 10.1080/01421590600607088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva RG, Figueiredo-Braga M. Evaluation of the relationships among happiness, stress, anxiety, and depression in pharmacy students. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10(7):903-910. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell JS, Johns R, Chen TF. Pharmacy students’ and graduates’ attitudes towards people with schizophrenia and severe depression. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4). doi: 10.5688/aj700477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayberry KM, Miller LN. Incidence of self-reported depression among pharmacy residents in Tennessee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(8):78-83. doi: 10.5688/ajpe5960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(5):334-341. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexandrino-Silva C, Pereira MLG, Bustamante C, et al. Suicidal ideation among students enrolled in healthcare training programs: a cross-sectional study. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2009;31(4):338-344. doi: 10.1590/S1516-44462009005000006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayala EE, Roseman D, Winseman JS, Mason HRC. Prevalence, perceptions, and consequences of substance use in medical students. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(11). doi: 10.1080/10872981.2017.1392824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah AA, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Lindstrom RW, Wolf KE. Prevalence of at-risk drinking among a national sample of medical students. Subst Abus. 2009;30(9):141-149. doi: 10.1080/08897070902802067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Shatnawi SF, Perri M, Young HN, Norton M. Substance use attitudes, behaviors, education and prevention in colleges of pharmacy in the United States. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts LW, Hardee JT, Franchini G, Stidley CA, Siegler M. Medical students as patients: a pilot study of their health care needs, practices, and concerns. Acad Med. 1996;71(11):1225-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geslani GP, Gaebelein CJ. Perceived stress, stressors, and mental distress among doctor of pharmacy students. Soc Behav Personal Int J. 2013;41(9):1457-1468. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2013.41.9.1457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healthy Minds Network. The Healthy Minds Study (HMS). http://healthymindsnetwork.org/research/hms. Published 2019. Accessed January 29, 2019.

- 26.Healthy Minds Study Team. The Healthy Minds Study 2015-2016 Report. Ann Arbor https://universitylife.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/healthy_minds_data_report_15-16.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2019.

- 27.Diener E, Wirtz D, Biswas-diener R, et al. New measures of well-being: flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 2009;39:247-266. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(16):606-613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. Cmaj. 2012;184(3):281-282. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.112004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092-1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garber MC. Exercise as a stress coping mechanism in a pharmacy student population. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(3):Article 50. doi: 10.5688/ajpe81350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tuttle JP, Scheurich NE, Ranseen J. Prevalence of adhd diagnosis and nonmedical prescription stimulant use in medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(3):220-223. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.34.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lally J, Conghaile A, Quigley S, Bainbridge E, McDonald C. Stigma of mental illness and help-seeking intention in university students. BJPsych Bull. 2013;37(8):253-260. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.112.041483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corrigan PW, Kerr A, Knudsen L. The stigma of mental illness: explanatory models and methods for change. Appl Prev Psychol. 2005;11(3):170-190. doi: 10.1016/j.appsy.2005.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Profile of Pharmacy Students Fall 2016. https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/2017-10/PPS_2016_Intro.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed February 12, 2019.

- 36.Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2016 All Schools Summary Report. Assoc Am Med Coll. 2016;(July):1-45. https://www.aamc.org/download/464412/data/2016gqallschoolssummaryreport.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. “Academic Pharmacy’s Vital Statistics.” https://www.aacp.org/article/academic-pharmacys-vital-statistics. Accessed December 19, 2019.

- 38.Association of American Medical Colleges. “Who We Are” https://www.aamc.org/who-we-are. Accessed December 19, 2019.

- 39.Association of American Medical Colleges. Table B-1.2: Total Enrollment by U.S. Medical School and Sex, 2014-2015 through 2018-2019. https://www.aamc.org/download/321526/data/factstableb1-2.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed February 12, 2019.