Abstract

Platelets play well-recognized roles in inflammation, but their cell of origin – the megakaryocyte – is not typically considered an immune lineage. Megakaryocytes are large polyploid cells most commonly identified in bone marrow. Egress via sinusoids enables migration to the pulmonary capillary bed, where elaboration of platelets can continue. Beyond receptors involved in hemostasis and thrombosis, megakaryocytes express receptors that confer immune sensing capacity, including Toll like receptors and Fc γ receptors. They control the proliferation of hematopoietic cells, facilitate neutrophil egress from marrow, possess the capacity to cross-present antigen, and can promote systemic inflammation through microparticles rich in interleukin 1. Megakaryocytes internalize other hematopoietic lineages, especially neutrophils, in an intriguing cell-in-cell interaction termed emperipolesis. Together, these observations implicate megakaryocytes as direct participants in inflammation and immunity.

Keywords: platelets, interleukin 1, microparticle, inflammation, lung

Summary sentence:

Drs. Cunin and Nigrovic review evidence showing that megakaryocytes can serve as immune actors independent of their daughter platelets.

Introduction

Megakaryocytes (MKs) are easily identified in bone marrow as large cells, 30 to 100 μm in diameter. They contain multiple nuclei, undergoing sequential rounds of endomitosis to acquire a genomic content averaging 16N (range 4–128N). Polyploidy permits amplification of gene expression, consistent with the high synthetic demands of platelet production.1,2 MKs are essential to survival. Neonates with severely impaired MK function exhibit high mortality in childbirth, and acquired or inherited thrombocytopenia has well-recognized consequences for hemostasis.3,4 However, accumulating evidence suggests that the physiologic portfolio of MKs extends beyond platelet “mother cell.” The goal of this Review is to present evidence in support of the hypothesis that MKs participate directly in immunity, delineating a new field of investigation at the intersection of hematology and immunology.

Basic megakaryocyte biology

MKs arise from hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) via the common myeloid progenitor and the megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor. MK progenitors then undergo multiple rounds of endomitosis, leading ultimately to the generation of mature MKs (Figure 1). Transcription factors including RUNX1, FLI1, and GATA1 govern MK development from HSC, while others including NF-E2 regulate platelet formation and release.5,6 Consequently, mutations in these transcription factors translate into defects in platelet production, structure or function.6 The principal growth factor regulating megakaryopoiesis is thrombopoietin (TPO), discussed further below. Megakaryopoiesis typically occurs in bone marrow but can also proceed as part of extramedullary hematopoiesis in spleen, in particular under conditions of systemic inflammation and in the context of genetic defects affecting hematopoiesis.7 More recently, MKs have been shown to develop in the interstitium of murine lung.8

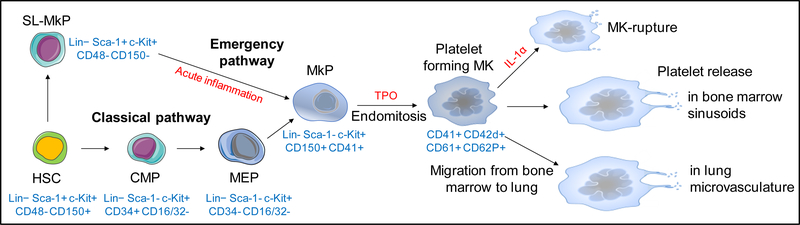

Figure 1: Megakaryocyte development from HSC to platelet.

HSC give rise to the common myeloid progenitor (CMP), MK-erythrocyte progenitor (MEP), and the lineage-committed megakaryocyte precursor (MkP). The HSC compartment also contains stem-like MK-committed progenitors (SL-MkP), remaining quiescent at steady state but rapidly giving rise to MkP during inflammation. After multiple round of endomitosis, MkP become mature MKs and release platelets into bone marrow sinusoids or migrate to the lung vasculature, where platelet production continues through the development of proplatelets. Under acute inflammatory or cytopenic conditions, elevation of IL-1α level promotes platelet release through rapid subdivision of the MK cytoplasm into platelets (“MK rupture”). In blue: characteristic surface markers during megakaryocyte ontogeny in mouse.

Despite their size, MKs can migrate toward chemotactic stimuli, although within the crowded marrow their mobility is constrained.9,10 Positioned close to marrow sinusoids, MKs can also egress directly into the circulation. In human venous blood, MKs appear at a concentration of 110 cells/ml, appearing morphologically typical including polyploid nucleus and generous cytoplasm.11–14 Most of these blood-borne MKs become trapped within the pulmonary circulation, reflected in a ~90% decrease in the concentration of blood MKs across this capillary bed as well as the lower size and cytoplasmic volume of MKs found in the arterial circulation.12,14 While scant in abundance compared to other leukocytes, MK migration to lung is nevertheless considerable, ranging from a few hundred thousand to over 1 million MKs per hour in humans.13–15 Indeed, an abundance of MKs has long been employed clinically as confirmation that a vascular aspirate reflects the pulmonary capillary bed.16

Trapped pulmonary MKs remain functional. Human studies repeatedly confirm that the concentration of platelets is higher in pulmonary vein than pulmonary artery, consistent with intra-pulmonary thrombocytogenesis.15 This process has been visualized using in vivo two-photon microscopy, yielding a rough estimate that half of murine platelets are generated in lung.8 Although both intravascular and interstitial MKs were identified, platelet production was predominantly mediated by MKs of extrapulmonary origin deposited within the lung capillary bed.8 Of note, the proportion of platelets produced in the lung remains under debate in the scientific community, and the proportion of human platelets generated in lung has yet to be established.

Heterogeneity within the MK population remains incompletely characterized. MKs differ in size, ploidy, and location. MKs cultured from murine bone marrow generate platelets less efficiently than those cultured from murine fetal liver, even under identical derivation conditions.17 MKs isolated from murine lung exhibit distinct gene expression signatures from those in marrow, and some surface markers also differ, for example higher CD42b (glycoprotein 1b) in marrow MKs.8 Immunofluorescence microscopy identified surface expression of the high-affinity IgG receptor FcγRI in some but not all murine marrow MKs.18 These observations reveal MK heterogeneity, likely with functional significance. The extent to which this variation reflects varying maturational stage, environmental control of MK phenotype, or ontogenically distinct MK subsets remain unknown.

Platelet production by megakaryocytes

In vivo microscopy has identified distinct pathways of thrombocytogenesis (Figure 1). Under steady-state conditions, MKs protrude microtubule-dependent membrane extensions termed “proplatelets” into bone marrow sinusoids, where shear stress releases fragments (“preplatelets”) that are then processed in the circulation to mature platelets.19–21 Platelet processing in lung capillaries could potentially contribute to the increased concentration of platelets observed in blood exiting the pulmonary circulation.15,22 Platelet generation via the proplatelet pathway also occurs in lung and spleen.8 Alternately, MKs may engage in so-called “explosive fragmentation” or “MK rupture” thrombocytogenesis, likely reflecting rapid subdivision of the MK cytoplasm rather than actual cell breakdown.23–25

TPO accelerates MK growth and thereby platelet production via the proplatelet route.23 This hematopoietic cytokine is elaborated by liver, kidney, and marrow stromal cells, and promotes differentiation and maturation of MKs.26 The level of TPO in blood is regulated in part by the concentration of circulating platelets, which express its receptor (c-mpl) and therefore compete with MKs for free cytokine. TPO generation is also directly stimulated by the binding of aging platelets to the hepatic Ashwell-Morell asialoglycoprotein receptor, since platelets lose surface sialic acid with time.27 Hepatic TPO synthesis is also regulated by GPIbα on the platelet surface 28, and as part of the IL-6-driven acute phase response, helping to drive thrombocytosis in systemic inflammation.29,30 In mouse, IL-1α can trigger “MK rupture” (cytoplasmic subdivision), contributing to emergency thrombopoiesis.23

Platelets as agents of immunity and inflammation

Beyond their essential hemostatic function, platelets aid immune defense by mechanisms that are the focus of recent reviews.31–34 From an evolutionary perspective, this overlap in function is not surprising, since the roles of platelet and phagocyte are shared by the amoebocyte in the phylogenetically-ancient horseshoe crab.35 Platelets express many immune receptors (TLR, receptors for immunoglobulins, costimulatory molecules) and cytokines in common with their parent MKs (Tables 1–2).34,36,37 Immune functions of platelets include promotion of leukocyte and endothelial activation and adhesion, amplification of neutrophil extracellular trap formation, and sensing and clearing of pathogens.31,32,36 Platelets also participate in pathogenic inflammation. For example, in inflammatory arthritis, platelets release microparticles that activate fibroblasts in the synovial lining and nucleate pro-inflammatory immune complexes.38–41 In systemic lupus erythematosus, platelets activated via immune complexes and complement release pro-inflammatory mediators, microparticles, and autoantigens.33

Table 1.

Selected surface molecules of immune relevance expressed by megakaryocytes

| Surface molecule | Ligand | Murine | Human |

|---|---|---|---|

| c-mpl | TPO | ||

| CD40L | CD40 | C58 | CL58 |

| CD80 | CD28, CTLA4 | C60 | |

| CD86 | CD28, CTLA4 | C60 | |

| FcγRI | IgG, CRP, SAP | IS18 | (no) |

| FcγRIIA | IgG (immune complexes) | (no) | IS55, CL56 |

| GPVI | collagen, laminin | ||

| IFNγR | IFNγ | CL47 | |

| IL-1R | IL-1α, IL-1β | IS123 CL 86 | |

| IL-6R | IL-6 | IS, CL 124 | |

| IFN-I R | IFNα, IFNβ | C125 | C,CL125 |

| MHC I | CD8 | C60 | |

| MHC II | CD4 | (C, weak)60 | (C, MK precursors)59 |

| TLR1 | peptidoglycan (+ TLR2) | CL47 | |

| TLR2 | (with TLR1/TLR6) | C51 | CL51, IS(?)50 |

| TLR3 | dsRNA | C52 | |

| TLR4 | LPS | C48 | CL49, IS(?)50 |

| TLR5 | flagellin | (IS, mRNA)8 | |

| TLR6 | lipoteichoic acid (+ TLR2) | CL47 |

IS = in situ (immunofluorescence, immunohistochemistry or primary cell flow cytometry/qPCR)

C = cultured primary MKs

CL = MK-like cell line

(?) = uncertainty related to methodology or reporting of results.

Listed receptors, ligands and references are not intended to be complete.

Table 2.

Mediators of immune relevance produced by megakaryocytes (partial list)

| Mediator | Murine | Human |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1α | C18 | |

| IL-1β | C18 | CL 87, IS 88 |

| IL-6 | IS42 | |

| IL-8 | (see CXCL1 + CXCL2) | CL81 |

| IL-33 | CL 126 | CL 126 |

| IFN-β (+/− α) | CL, C125 | |

| APRIL | IS42 | |

| CXCL1 | IS81 | (see IL-8) |

| CXCL2 | IS81 | (see IL-8) |

| CXCL4 | IS44 | |

| TGF-β | IS45 | |

| FGF1 | IS45 | |

| PDGF-BB | C43 |

IS = in situ (immunofluorescence, immunohistochemistry or primary cell flow cytometry/qPCR)

C = cultured primary MKs

CL = MK-like cell line

Listed mediators and references are not intended to be complete.

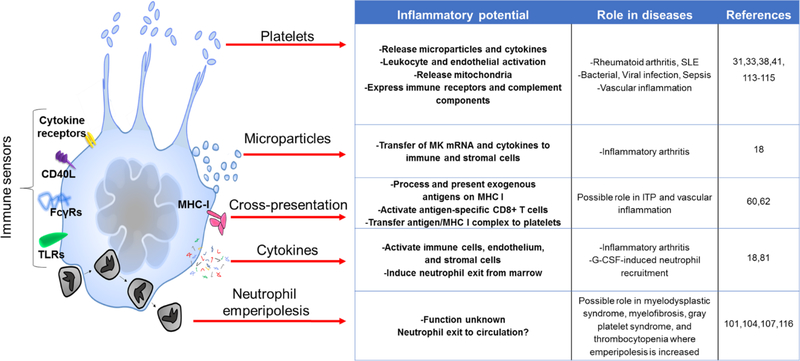

Overview of platelet-independent megakaryocyte functions in immunity

Not all aspects of MK behavior are straightforwardly connected to thrombocytogenesis. For example, platelet production does not require migration to lung. MKs engage in close contact with other hematopoietic lineages in the bone marrow. They express surface receptors that confer an ability to sense inflammation and present antigen. They release IL-1 and other cytokines, sometimes packaged within microparticles. Finally, MKs engulf other hematopoietic cells – particularly neutrophils – in an intriguing interaction termed emperipolesis. We will consider these observations as evidence that the MK portfolio is much broader, and more “immunologic,” than typically appreciated.

Megakaryocytes as modulators of the hematopoietic niche

MKs represent a small fraction of bone marrow hematopoietic cells (estimated at ~0.3% in mice)42, but given their size and crowded environment MKs are in direct contact with many cells. Accumulating evidence indicates that this contact has important functional consequences. Plasma cells in the marrow reside near MKs at a frequency greater than expected by chance and can form direct cell-cell adhesions with MKs.42 This contact promotes plasma cell survival, potentially via MK-supplied IL-6 and APRIL (a member of the TNF superfamily), although the impact on antibody responses appears to be modest.42 MKs in an endosteal location promote osteoblast expansion, likely via platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB), as observed in MK-osteoblast co-culture.43

MKs also control the proliferation of HSC. In murine marrow, ~20% of HSC reside in direct contact with MKs, that serve to keep HSC quiescent through expression of PF4 and TGF-β. Correspondingly, selective deletion of PF4 or TGF-β in MKs increases HSC activation and proliferation.44,45 However, in response to myeloablative stress such as chemotherapy, MKs reverse this role to promote HSC proliferation via FGF1, such that MK depletion impairs HSC regeneration after chemotherapy.45 The capacity of HSCs to promote long-term multilineage reconstitution is increased after co-culture with MKs, an effect mediated by MK-derived IGF-1 and IGFBP-3.46 Transplanted HSC localize preferentially to MKs 46, and blockade of MK functions by genetic deletion of c-MPL or treatment with blocking anti-CD41 antibody decreases HSC engraftment in irradiated mice.43 Thus, MKs regulate the HSC pool size and curate the hematopoietic niche.

Megakaryocytes immunoreceptors and effector molecules

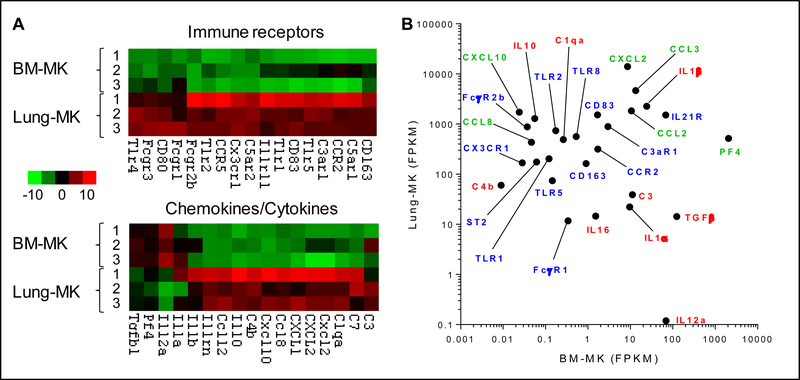

MKs express receptors that enable them to sense inflammation (Table 1, Figure 2). These include members of the Toll-like receptor family, including TLRs 1,2,3,4 and 6.47–52 TLR5 has been identified at the mRNA level in lung MKs.8 In most cases the evidence for these is limited to in vitro studies, rendering the expression and role of TLRs on MKs in situ still uncertain. It is possible that activation via TLR2 and TLR4 accelerates MK maturation and platelet production, though indirect effects via other lineages remain difficult to exclude.51,53,54 TLR expression likely varies with location, with higher levels of mRNA for TLRs in lung than in bone marrow (Figure 2).8

Figure 2: Immunoreceptors and effector molecules in lung vs. bone marrow megakaryocytes.

A. Heat maps display examples of immune protein expression by RNAseq in MKs from lung or bone marrow. B. Values show average fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) across conditions. Green: chemokines; Red: cytokines and other immune effectors; Blue: immune receptors. BM, bone marrow. Figures generated from data published in Lefrancais, Ortiz-Muños, et al. (ref 8).

Studies with cell lines and primary cells have identified MK expression of IgG Fc receptors (FcγR). Human and murine FcγR systems are overlapping but distinct, and this difference extends to MKs. Human studies find the low-affinity activating receptor FcγRIIA as the only member of this family on MKs, a receptor also expressed on human platelets.55,56 The function of this receptor on MKs is undefined. By contrast, murine platelets do not express Fc γ receptors, while MKs express only the high-affinity receptor FcγRI on a subpopulation of MKs.18 Stimulation with the non-canonical FcγRI ligands C-reactive protein and serum amyloid protein potentiates MK microparticle production, the only activation pathway shown to date to increase release above constitutive levels.18 The IgE receptor FcεRI has been found in human MKs at the protein level, but since it appears to be exclusively intracellular this expression may simply serve to “load” platelets, that do express functional surface FcεRI.57

Finally, MKs exhibit surface molecules related to adaptive immunity. MKs express CD40L, the ligand of the stimulatory molecule CD40 on B cells, T cells, and macrophages.58 MK precursors (MKp) express MHC II, although this molecule is absent or present at very low levels on mature MKs.59,60 In mice, a lineagenegKitposCD41pos population with MK precursor features has been shown express MHC II and to promote Th17 cell development in vitro in a manner that is at least partially MHC II-dependent.61 The ability of human MKp to present antigen via MHC II in a cognate manner has not been established, although these cells express mRNA encoding Th17inducing cytokines (including IL-1β, IL-23, IL-6, TGFβ) and can expand Th17 and Th1 cells in vitro, albeit in a contact-independent manner.59 Mature MKs express MHC I as well as the cellular machinery to take up and process antigen for cross-presentation, sufficient to enable immune thrombocytopenia in a murine system.60 Intriguingly, loaded MHC I-antigen complexes can be transferred to platelets, potentially enabling and amplifying the antigen cross-presentation previously identified in platelets.60,62

Megakaryocyte cytokines, chemokines, and other mediators

MKs elaborate multiple cytokines and soluble mediators that impact immune cells (Table 2, Figure 2). Many of these mediators are stored in alpha granules, including PF4/CXCL4, TGFβ, IL-8, and CXCL1.63 Alpha granules are released by platelets upon activation. MKs are also capable of releasing their granule contents into the bone marrow environment, although the mechanisms regulating this release remain undefined. As a result, the medullary environment is characterized by high concentrations of PF4 and TGFβ of MKs origin.45,64 These mediators control HSC proliferation, as noted above, and also constrain MK maturation.64–67 PF4 and TGFβ could potentially affect other immune cells through their receptors CXCR3B and TGFβR. 68,69 For example, PF4 and TGFβ are potent neutrophil activators and promote neutrophil survival and migration, suggesting that MKs could modulate neutrophils before they are released into blood.70–75 TGFβ is required for Th17 and inducible Treg differentiation.76–78 Interestingly, immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is characterized by a defect in Treg cell development in favor of Th17 cells.79,80 The role of MK-derived TGFβ in this skewed CD4+ T cell differentiation and thereby in the maintenance of the Treg/Th17 balance remains to be defined.

As further evidence for a relationship between MKs and neutrophils, MKs have been found to mediate the efflux of neutrophils from bone marrow in response to G-CSF. MKs do not sense this growth factor directly. Rather, G-CSF elicits TPO production within the marrow, presumably from stromal cells, triggering MKs to release the chemoattractants CXCL1 (KC) and CXCL2 (MIP-2) that facilitate neutrophil egress. Accordingly, absence of receptors for either TPO or CXCL1/2 attenuates G-CSF-mediated neutrophil egress, while administration of TPO elicits neutrophilia.81 Whether MK-derived TGFβ and PF4 participate in egress remains to be investigated.

It is now well recognized that platelets produce the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1.38,82 IL-1α is expressed constitutively at a protein level and can be detected on resting platelets.38,83 By contrast, IL-1β is present only at the mRNA level, enabling rapid synthesis after platelet activation.38,84 IL-1α/β released by platelets activates immune cells, endothelial cells, and synovial fibroblasts and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of RA and SLE.10,41,82 The presence of IL-1α and IL-1β at a protein and mRNA level has been documented in murine MKs, with some supportive data from human MK cell lines and primary MKs.8,18,85–88 MK-conditioned media activates synovial fibroblasts in an IL-1R-dependent manner, while engraftment of WT but not IL-1α/β-deficient MKs restores arthritis susceptibility in a mice resistant to arthritis. This effect is independent of platelets, confirming a capacity for MKs to directly mediate IL-1-driven systemic inflammatory disease.18

MKs can release IL-1α/β directly or packaged in microparticles (see below). IL-1α is also observed in MK nuclei in a small percentage of bone marrow MKs.18 Interestingly, denuded MK nuclei are often found in murine, dog or human lungs, and were the first evidence that platelets could be produced from the lung.89,90 MK nuclei in lung are more numerous in patients with sepsis, cardiovascular diseases and underlying malignancies, but whether these nuclei contain IL-1α or other alarmins remain to be determined.91

Megakaryocyte microparticles

Microparticles are small vesicles (0.1–1μm) released through surface blebbing by many lineages, including endothelial cells, leukocytes, erythrocytes and platelets. They contain proteins, metabolites and RNA from their cell of origin and can transfer this cargo to distant cells and tissues. Microparticles expressing the platelet/MK surface marker CD41 represent 70–90% of circulating microparticles and have been of interest because of their roles in hemostasis and inflammation.92–94 It had been assumed that CD41+ microparticles were of platelet origin because they are elevated in thrombotic conditions and in systemic inflammatory diseases associated with platelet activation.33,38,92,94 However, in 2009 Flaumenhaft and colleagues showed that CD41+ microparticles can arise directly from MKs.93 While platelets require activation to produce microparticles, human and murine MKs produce microparticles constitutively. Like platelet microparticles, MK microparticles express CD41, CD42b and phosphatidylserine, but lack surface CD62P and LAMP-1. MKs and MK-derived microparticles contain full-length filamin A, whereas platelet microparticles contain predominantly cleaved filamin A, likely reflecting the platelet activation required for microparticle release.93 MK microparticles are also reported to express both GPVI and CLEC2, whereas platelet microparticles express exclusively CLEC2.95 Since most circulating CD41+ microparticles in healthy individuals express neither CD62P nor LAMP-1 but both GPVI and CLEC2, and contain predominantly full-length filamin A, it appears likely that they originate directly from MKs, rendering MK microparticles the most common type of microparticle in blood.92,93,95

CD41+ microparticles have important roles in inflammatory diseases such as SLE and RA. 33,38,41,94 For example, they contain pro-inflammatory mediators that can activate distant cells 38, and can nucleate synovial immune complexes in RA.40 The high concentration of CD41+ microparticles in inflamed synovial fluid compared with plasma suggests that platelets activated on site represent the main source in this context.38 However, like platelet microparticles, MK microparticles contain IL-1α/β and can stimulate synovial fibroblasts in vitro in an IL-1R-dependent manner.18 MKs engrafted i.v. into mice deposit in the lung, where they release IL-1-rich CD41+ microparticles negative for LAMP-1 and CD62P into the circulation. As noted above, engraftment of WT but not IL-1-deficient MKs restores arthritis susceptibility; whether this IL-1 is provided through microparticles, release of free cytokine, or indirectly via the relatively few platelets generated by these engrafted MKs is difficult to establish definitively.18 In any case, the abundance and inflammatory potency of MK microparticles renders defining their immune armamentarium and release mechanisms an important priority for understanding MKs as inflammatory cells (see “in-line sensor” hypothesis below).

Megakaryocyte emperipolesis

The term “emperipolesis” is derived from the Greek, em “inside” peri “around” polesis “wandering.” It was originally employed to describe the observation, in fresh living cell preparations, of human lymphocytes moving about within other cells, including tumor cells and MKs.96 The term is sometimes used to refer to any phenomenon of one cell within another.97 However, cell-in-cell interactions are mechanistically and functionally diverse – e.g. phagocytosis, entosis, efferocytosis, transcellular migration – such that we will here restrict the term to cell-in-cell interactions wherein the internalized cells remain morphologically intact, as occurs during internalization of neutrophils by MKs.

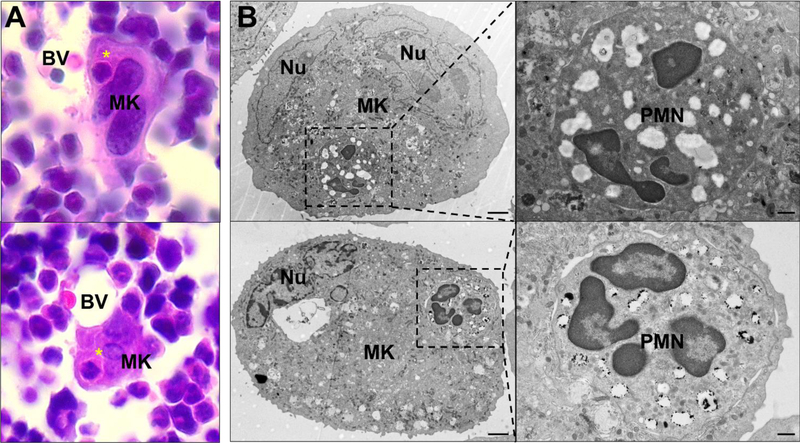

Emperipolesis is routinely observed in bone marrow, both human and murine, though generally involving less than 5% of MKs on conventional histological sectioning (Figure 3).98 Most internalized cells are neutrophils, though erythrocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils and monocytes can also be involved.98,99 MKs containing 10 or more cells have been reported.98,100 Emperipolesis increases markedly under pathologic conditions, including hematologic malignancy and myelofibrosis.98,101–103 In animal models, emperipolesis increases with experimental blood loss and with administration of LPS and potentially IL-6.104–106 Emperipolesis is a hallmark of certain genetic disorders of megakaryocyte development, including mutations affecting the vesicular trafficking gene NBEAL2 (gray platelet syndrome), the myosin chain gene MYH9, and the hematopoietic transcription factor GATA1.107–109 Mechanistic insight into the cell biology of emperipolesis is scant, although it has been noted that β2 integrin blockade retards emperipolesis in rat.110

Figure 3: Emperipolesis in murine bone marrow and in vitro-generated megakaryocytes.

A. Asterisks show bone marrow cells internalized within MKs. H&E staining. BV: blood vessels. B. Murine MKs differentiated in vitro were co-cultured with bone marrow cells and observed by electron microscopy. Scale bars: 2μm (left images) and 500nm (right images). Nu: MK nucleus. PMN: polymorphonuclear neutrophil.

The function of emperipolesis is unknown. Typically considered a histological curiosity, its presence in human, mouse, rat, cat, dog, and monkey implies evolutionary conservation.105,106,111 Live cell imaging suggests egress of viable cells from MKs.98 The localization of MKs to bone marrow sinusoids and the increase in emperipolesis with blood loss has prompted speculation that it may facilitate cell egress, though direct experimental evidence is lacking.99,104,105 Alternately, it has been proposed that emperipolesis may provide a ‘sanctuary’ within the bone marrow.100 Recent development of an in vitro model of emperipolesis, together with ultrastructural imaging and in vivo murine chimera experiments, implicate emperipolesis in a novel pathway for the exchange of membrane and other material between MKs and neutrophils, likely with important functional consequences for both cell types.112

Megakaryocyte localization and the “in-line sensor” hypothesis

Spatial localization provides a further clue to platelet-independent MK effector functions. Marrow is ideally suited for the husbandry of HSC, osteoblasts, and other hematopoietic lineages. Marrow MKs typically reside in perisinusoidal areas to extend proplatelets into the circulation. This location could also enable MKs to regulate transit of cells from (and potentially back to) the marrow, as well as to communicate signals between blood and marrow. Spleen is a distinct but related environment, perhaps even better positioned than marrow to sense systemic perturbations. Lung may be the optimal location for MKs as immune effector cells, since the pulmonary vasculature is exposed both to blood-borne pathogens and to the highest concentration of acute phase proteins released by the liver into the hepatic veins. Lung MKs are also ideally positioned to release mediators directly into the arterial circulation, maximizing the systemic impact of soluble mediators and of microparticles whose surface phosphatidylserine renders them vulnerable to first-pass clearance in liver and spleen. Since plugging pulmonary capillaries with MKs does not otherwise confer obvious benefit, the fact that millions of MKs are deposited daily in lung – across species separated by tens of millions of years of evolution – suggests an important survival benefit. We consider it probable that lung MKs represent “in-line sensors” that participate in immunity and inflammation, although other MKs could serve in this capacity as well. The hypothesis that lung MKs are particularly important as immune sensors is supported by the observation that lung MKs exhibit a signature of immune receptors and mediators that is distinct and potentially pro-inflammatory compared with marrow MKs (Figure 2).8

Opportunities and challenges in research: effector megakaryocytes

As this review has made clear, MKs are not only platelets producers but also immune cells in their own right. We are just at the beginning of defining the contribution of what one might term effector megakaryocytes. Understanding of MK activation and effector pathways remains at a basic level, including the content and function of MK microparticles. The migration of MKs to lung capillaries suggests a sentinel role. Emperipolesis promises to be particularly interesting, both in its cell-biological mechanisms and its functional consequences (Figure 4).

Figure 4:

Megakaryocyte effector mechanisms.

Some tools are available, including in vitro culture of murine and human MKs 117–119, strategies for adoptive transfer of MKs into living hosts 18,120, animals bearing fluorescent MKs for in vivo imaging (CD41-YFP 121 and PF4-Cre × mT/mG 8), and PF4-cre animals for cre/lox-mediated gene deletion with some degree of MK/platelet selectivity.44,45,122 There are also major methodologic challenges. Since platelets are required for hemostasis, animals bearing major defects in the MKs population have limited viability.5 Distinguishing the activity of MKs from that of their platelets will be difficult, since platelets exhibit overlapping biology with MKs and will be affected by any manipulation of their parent cells. Inhibitors specific for microparticle production or emperipolesis suitable for in vivo use are unavailable. Nevertheless, it remains clear that study of MKs as direct immune actors remains a rich field for exploration and discovery.

Concluding Remarks

MKs are intriguing cells. Their ability to generate platelets is critical for survival and has therefore been the focus of most MK research to date. However, the functional portfolio of MKs extends beyond platelet production. Clues to this “effector MK” portfolio include migration to lung, expression of immunoreceptors, production of soluble mediators and microparticles, and close interaction with other lineages in bone marrow, including via emperipolesis. Collectively, these activities point convincingly to a role for MKs as immune cells. We anticipate that coming years will bring striking new insights into this novel area of overlap between hematology and immunology.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following for comments on the manuscript: Eric Boilard, Roxane Darbousset, Joseph E. Italiano, and Kellie R. Machlus. P.C. is supported by a grant from the Arthritis National Research Foundation and a JBC Microgrant from the Joint Biology Consortium (P30 AR070253). P.A.N. is funded by NIH awards R01 AR065538 and P30 AR070253 and by the Fundación Bechara.

Abbreviations:

- IL

interleukin

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MK(s)

megakaryocyte(s)

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- TPO

thrombopoietin

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors declare no relevant conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Raslova H, Roy L, Vourc’h C, et al. Megakaryocyte polyploidization is associated with a functional gene amplification. Blood. 2003;101(2):541–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock V, Martin JF, Lelchuk R. The relationship between human megakaryocyte nuclear DNA content and gene expression. Br J Haematol. 1993;85(4):692–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geddis AE. Congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia and thrombocytopenia with absent radii. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2009;23(2):321–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox NE, Chen R, Hitchcock I, Keates-Baleeiro J, Frangoul H, Geddis AE. Compound heterozygous c-Mpl mutations in a child with congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia: functional characterization and a review of the literature. Experimental hematology. 2009;37(4):495–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shivdasani RA, Rosenblatt MF, Zucker-Franklin D, et al. Transcription factor NF-E2 is required for platelet formation independent of the actions of thrombopoietin/MGDF in megakaryocyte development. Cell. 1995;81(5):695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Songdej N, Rao AK. Hematopoietic transcription factor mutations: important players in inherited platelet defects. Blood. 2017;129(21):2873–2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nigrovic PA, Gray DH, Jones T, et al. Genetic inversion in mast cell-deficient (Wsh) mice interrupts corin and manifests as hematopoietic and cardiac aberrancy. The American journal of pathology. 2008;173(6):1693–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lefrancais E, Ortiz-Munoz G, Caudrillier A, et al. The lung is a site of platelet biogenesis and a reservoir for haematopoietic progenitors. Nature. 2017;544(7648):105–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamada T, Mohle R, Hesselgesser J, et al. Transendothelial migration of megakaryocytes in response to stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) enhances platelet formation. J Exp Med. 1998;188(3):539–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stegner D, vanEeuwijk JMM, Angay O, et al. Thrombopoiesis is spatially regulated by the bone marrow vasculature. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minot GR. Megacaryocytes in the Peripheral Circulation. J Exp Med. 1922;36(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melamed MR, Cliffton EE, Mercer C, Koss LG. The megakaryocyte blood count. Am J Med Sci. 1966;252(3):301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheinin TM, Koivuniemi AP. Megakaryocytes in the pulmonary circulation. Blood. 1963;22:82–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine RF, Eldor A, Shoff PK, Kirwin S, Tenza D, Cramer EM. Circulating megakaryocytes: delivery of large numbers of intact, mature megakaryocytes to the lungs. European journal of haematology. 1993;51(4):233–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA. Platelets in lung biology. Annual review of physiology. 2013;75:569–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masson RG, Krikorian J, Lukl P, Evans GL, McGrath J. Pulmonary microvascular cytology in the diagnosis of lymphangitic carcinomatosis. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(2):71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazharian A, Watson SP, Severin S. Critical role for ERK1/2 in bone marrow and fetal liverderived primary megakaryocyte differentiation, motility, and proplatelet formation. Experimental hematology. 2009;37(10):1238–1249 e1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunin P, Penke LR, Thon JN, et al. Megakaryocytes compensate for Kit insufficiency in murine arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(5):1714–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Junt T, Schulze H, Chen Z, et al. Dynamic visualization of thrombopoiesis within bone marrow. Science. 2007;317(5845):1767–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thon JN, Macleod H, Begonja AJ, et al. Microtubule and cortical forces determine platelet size during vascular platelet production. Nat Commun. 2012;3:852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bender M, Thon JN, Ehrlicher AJ, et al. Microtubule sliding drives proplatelet elongation and is dependent on cytoplasmic dynein. Blood. 2015;125(5):860–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Handagama PJ, Feldman BF, Jain NC, Farver TB, Kono CS. Circulating proplatelets: isolation and quantitation in healthy rats and in rats with induced acute blood loss. Am J Vet Res. 1987;48(6):962–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishimura S, Nagasaki M, Kunishima S, et al. IL-1alpha induces thrombopoiesis through megakaryocyte rupture in response to acute platelet needs. J Cell Biol. 2015;209(3):453–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosaki G In vivo platelet production from mature megakaryocytes: does platelet release occur via proplatelets? Int J Hematol. 2005;81(3):208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Italiano JE Jr., Lecine P, Shivdasani RA, Hartwig JH. Blood platelets are assembled principally at the ends of proplatelet processes produced by differentiated megakaryocytes. J Cell Biol. 1999;147(6):1299–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaushansky K Thrombopoietin and its receptor in normal and neoplastic hematopoiesis. Thromb J. 2016;14(Suppl 1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grozovsky R, Begonja AJ, Liu K, et al. The Ashwell-Morell receptor regulates hepatic thrombopoietin production via JAK2-STAT3 signaling. Nat Med. 2015;21(1):47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu M, Li J, Neves MAD, et al. GPIbalpha is required for platelet-mediated hepatic thrombopoietin generation. Blood. 2018;132(6):622–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.s A, Brandacher G, Steurer W, et al. Interleukin-6 stimulates thrombopoiesis through thrombopoietin: role in inflammatory thrombocytosis. Blood. 2001;98(9):2720–2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burmester H, Wolber EM, Freitag P, Fandrey J, Jelkmann W. Thrombopoietin production in wild-type and interleukin-6 knockout mice with acute inflammation. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25(7):407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koupenova M, Clancy L, Corkrey HA, Freedman JE. Circulating Platelets as Mediators of Immunity, Inflammation, and Thrombosis. Circ Res. 2018;122(2):337–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SJ, Davis RP, Jenne CN. Platelets as Modulators of Inflammation. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2018;44(2):91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linge P, Fortin PR, Lood C, Bengtsson AA, Boilard E. The non-haemostatic role of platelets in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2018;14(4):195–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Semple JW, Italiano JE Jr., Freedman J. Platelets and the immune continuum. Nature reviews Immunology. 2011;11(4):264–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levin J, Bang FB. A Description of Cellular Coagulation in the Limulus. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1964;115:337–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, et al. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med. 2007;13(4):463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aslam R, Speck ER, Kim M, et al. Platelet Toll-like receptor expression modulates lipopolysaccharide-induced thrombocytopenia and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in vivo. Blood. 2006;107(2):637–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boilard E, Nigrovic PA, Larabee K, et al. Platelets amplify inflammation in arthritis via collagen-dependent microparticle production. Science. 2010;327(5965):580–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boilard E, Larabee K, Shnayder R, et al. Platelets participate in synovitis via Cox-1-dependent synthesis of prostacyclin independently of microparticle generation. J Immunol. 2011;186(7):4361–4366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cloutier N, Tan S, Boudreau LH, et al. The exposure of autoantigens by microparticles underlies the formation of potent inflammatory components: the microparticle-associated immune complexes. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5(2):235–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boilard E, Blanco P, Nigrovic PA. Platelets: active players in the pathogenesis of arthritis and SLE. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2012;8(9):534–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winter O, Moser K, Mohr E, et al. Megakaryocytes constitute a functional component of a plasma cell niche in the bone marrow. Blood. 2010;116(11):1867–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olson TS, Caselli A, Otsuru S, et al. Megakaryocytes promote murine osteoblastic HSC niche expansion and stem cell engraftment after radioablative conditioning. Blood. 2013;121(26):5238–5249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bruns I, Lucas D, Pinho S, et al. Megakaryocytes regulate hematopoietic stem cell quiescence through CXCL4 secretion. Nat Med. 2014;20(11):1315–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao M, Perry JM, Marshall H, et al. Megakaryocytes maintain homeostatic quiescence and promote post-injury regeneration of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2014;20(11):1321–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heazlewood SY, Neaves RJ, Williams B, Haylock DN, Adams TE, Nilsson SK. Megakaryocytes colocalise with hemopoietic stem cells and release cytokines that up-regulate stem cell proliferation. Stem cell research. 2013;11(2):782–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shiraki R, Inoue N, Kawasaki S, et al. Expression of Toll-like receptors on human platelets. Thromb Res. 2004;113(6):379–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andonegui G, Kerfoot SM, McNagny K, Ebbert KV, Patel KD, Kubes P. Platelets express functional Toll-like receptor-4. Blood. 2005;106(7):2417–2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ward JR, Bingle L, Judge HM, et al. Agonists of toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 are unable to modulate platelet activation by adenosine diphosphate and platelet activating factor. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2005;94(4):831–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maratheftis CI, Andreakos E, Moutsopoulos HM, Voulgarelis M. Toll-like receptor-4 is upregulated in hematopoietic progenitor cells and contributes to increased apoptosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2007;13(4):1154–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beaulieu LM, Lin E, Morin KM, Tanriverdi K, Freedman JE. Regulatory effects of TLR2 on megakaryocytic cell function. Blood. 2011;117(22):5963–5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D’Atri LP, Etulain J, Rivadeneyra L, et al. Expression and functionality of Toll-like receptor 3 in the megakaryocytic lineage. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2015;13(5):839–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu D, Xie J, Wang X, et al. Micro-concentration Lipopolysaccharide as a Novel Stimulator of Megakaryocytopoiesis that Synergizes with IL-6 for Platelet Production. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jayachandran M, Brunn GJ, Karnicki K, Miller RS, Owen WG, Miller VM. In vivo effects of lipopolysaccharide and TLR4 on platelet production and activity: implications for thrombotic risk. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2007;102(1):429–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rabellino EM, Levene RB, Nachman RL, Leung LL. Human megakaryocytes. III. Characterization in myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 1984;63(3):615–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Markovic B, Wu Z, Chesterman CN, Chong BH. Quantitation of soluble and membrane-bound Fc gamma RIIA (CD32A) mRNA in platelets and megakaryoblastic cell line (Meg-01). Br J Haematol. 1995;91(1):37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hasegawa S, Pawankar R, Suzuki K, et al. Functional expression of the high affinity receptor for IgE (FcepsilonRI) in human platelets and its’ intracellular expression in human megakaryocytes. Blood. 1999;93(8):2543–2551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crist SA, Elzey BD, Ahmann MT, Ratliff TL. Early growth response-1 (EGR-1) and nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) cooperate to mediate CD40L expression in megakaryocytes and platelets. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(47):33985–33996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Finkielsztein A, Schlinker AC, Zhang L, Miller WM, Datta SK. Human megakaryocyte progenitors derived from hematopoietic stem cells of normal individuals are MHC class II-expressing professional APC that enhance Th17 and Th1/Th17 responses. Immunol Lett. 2015;163(1):84–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zufferey A, Speck ER, Machlus KR, et al. Mature murine megakaryocytes present antigen-MHC class I molecules to T cells and transfer them to platelets. Blood Adv. 2017;1(20):1773–1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kang HK, Chiang MY, Ecklund D, Zhang L, Ramsey-Goldman R, Datta SK. Megakaryocyte progenitors are the main APCs inducing Th17 response to lupus autoantigens and foreign antigens. J Immunol. 2012;188(12):5970–5980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chapman LM, Aggrey AA, Field DJ, et al. Platelets present antigen in the context of MHC class I. J Immunol. 2012;189(2):916–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blair P, Flaumenhaft R. Platelet alpha-granules: basic biology and clinical correlates. Blood reviews. 2009;23(4):177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lambert MP, Meng R, Xiao L, et al. Intramedullary megakaryocytes internalize released platelet factor 4 and store it in alpha granules. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2015;13(10):1888–1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuter DJ, Gminski DM, Rosenberg RD. Transforming growth factor beta inhibits megakaryocyte growth and endomitosis. Blood. 1992;79(3):619–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sakamaki S, Hirayama Y, Matsunaga T, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1) induces thrombopoietin from bone marrow stromal cells, which stimulates the expression of TGF-beta receptor on megakaryocytes and, in turn, renders them susceptible to suppression by TGF-beta itself with high specificity. Blood. 1999;94(6):1961–1970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lambert MP, Rauova L, Bailey M, Sola-Visner MC, Kowalska MA, Poncz M. Platelet factor 4 is a negative autocrine in vivo regulator of megakaryopoiesis: clinical and therapeutic implications. Blood. 2007;110(4):1153–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lasagni L, Francalanci M, Annunziato F, et al. An alternatively spliced variant of CXCR3 mediates the inhibition of endothelial cell growth induced by IP-10, Mig, and I-TAC, and acts as functional receptor for platelet factor 4. J Exp Med. 2003;197(11):1537–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen W, Ten Dijke P. Immunoregulation by members of the TGFbeta superfamily. Nature reviews Immunology. 2016;16(12):723–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lapchak PH, Ioannou A, Rani P, et al. The role of platelet factor 4 in local and remote tissue damage in a mouse model of mesenteric ischemia/reperfusion injury. PloS one. 2012;7(7):e39934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Deuel TF, Senior RM, Chang D, Griffin GL, Heinrikson RL, Kaiser ET. Platelet factor 4 is chemotactic for neutrophils and monocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1981;78(7):4584–4587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zaldivar MM, Pauels K, von Hundelshausen P, et al. CXC chemokine ligand 4 (Cxcl4) is a platelet-derived mediator of experimental liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2010;51(4):1345–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lagraoui M, Gagnon L. Enhancement of human neutrophil survival and activation by TGF-beta 1. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 1997;43(3):313–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brandes ME, Mai UE, Ohura K, Wahl SM. Type I transforming growth factor-beta receptors on neutrophils mediate chemotaxis to transforming growth factor-beta. J Immunol. 1991;147(5):1600–1606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fava RA, Olsen NJ, Postlethwaite AE, et al. Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-beta 1) induced neutrophil recruitment to synovial tissues: implications for TGF-beta-driven synovial inflammation and hyperplasia. J Exp Med. 1991;173(5):1121–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Volpe E, Touzot M, Servant N, et al. Multiparametric analysis of cytokine-driven human Th17 differentiation reveals a differential regulation of IL-17 and IL-22 production. Blood. 2009;114(17):3610–3614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wan YY, Flavell RA. ‘Yin-Yang’ functions of transforming growth factor-beta and T regulatory cells in immune regulation. Immunol Rev. 2007;220:199–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McKenzie CG, Guo L, Freedman J, Semple JW. Cellular immune dysfunction in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). Br J Haematol. 2013;163(1):10–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ji L, Zhan Y, Hua F, et al. The ratio of Treg/Th17 cells correlates with the disease activity of primary immune thrombocytopenia. PloS one. 2012;7(12):e50909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kohler A, De Filippo K, Hasenberg M, et al. G-CSF-mediated thrombopoietin release triggers neutrophil motility and mobilization from bone marrow via induction of Cxcr2 ligands. Blood. 2011;117(16):4349–4357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Boilard E Platelet-Derived Interleukin-1beta Fuels the Fire in Blood Vessels in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2017;37(4):607–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thornton P, McColl BW, Greenhalgh A, Denes A, Allan SM, Rothwell NJ. Platelet interleukin1alpha drives cerebrovascular inflammation. Blood. 2010;115(17):3632–3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lindemann S, Tolley ND, Dixon DA, et al. Activated platelets mediate inflammatory signaling by regulated interleukin 1beta synthesis. J Cell Biol. 2001;154(3):485–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sandrock B, Hudson KM, Williams DE, Lieberman MA. Cytokine production by a megakaryocytic cell line. In vitro cellular & developmental biology Animal. 1996;32(4):225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Beaulieu LM, Lin E, Mick E, et al. Interleukin 1 receptor 1 and interleukin 1beta regulate megakaryocyte maturation, platelet activation, and transcript profile during inflammation in mice and humans. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2014;34(3):552–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nhek S, Clancy R, Lee KA, et al. Activated Platelets Induce Endothelial Cell Activation via an Interleukin-1beta Pathway in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2017;37(4):707–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jiang S, Levine JD, Fu Y, et al. Cytokine production by primary bone marrow megakaryocytes. Blood. 1994;84(12):4151–4156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zucker-Franklin D, Philipp CS. Platelet production in the pulmonary capillary bed: new ultrastructural evidence for an old concept. The American journal of pathology. 2000;157(1):6974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kaufman RM, Airo R, Pollack S, Crosby WH, Doberneck R. Origin of Pulmonary Megakaryocytes. Blood. 1965;25:767–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Khan Z Diagnostic atlas of non-neoplastic lung disease: a practical guide for surgical pathologists. Journal of clinical pathology. 2017;70(10):908. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Italiano JE Jr., Mairuhu AT, Flaumenhaft R. Clinical relevance of microparticles from platelets and megakaryocytes. Current opinion in hematology. 2010;17(6):578–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Flaumenhaft R, Dilks JR, Richardson J, et al. Megakaryocyte-derived microparticles: direct visualization and distinction from platelet-derived microparticles. Blood. 2009;113(5):1112–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Melki I, Tessandier N, Zufferey A, Boilard E. Platelet microvesicles in health and disease. Platelets. 2017;28(3):214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gitz E, Pollitt AY, Gitz-Francois JJ, et al. CLEC-2 expression is maintained on activated platelets and on platelet microparticles. Blood. 2014;124(14):2262–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Humble JG, Jayne WH, Pulvertaft RJ. Biological interaction between lymphocytes and other cells. Br J Haematol. 1956;2(3):283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Overholtzer M, Mailleux AA, Mouneimne G, et al. A nonapoptotic cell death process, entosis, that occurs by cell-in-cell invasion. Cell. 2007;131(5):966–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Larsen TE. Emperipolesis of granular leukocytes within megakaryocytes in human hemopoietic bone marrow. American journal of clinical pathology. 1970;53(4):485–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sahebekhitiari HA, Tavassoli M. Marrow cell uptake by megakaryocytes in routine bone marrow smears during blood loss. Scand J Haematol. 1976;16(1):13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.de Pasquale A, Paterlini P, Quaglino D, Quaglino D. Emperipolesis of granulocytes within megakaryocytes. Br J Haematol. 1985;60(2):384–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cashell AW, Buss DH. The frequency and significance of megakaryocytic emperipolesis in myeloproliferative and reactive states. Annals of hematology. 1992;64(6):273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Thiele J, Schneider G, Hoeppner B, Wienhold S, Zankovich R, Fischer R. Histomorphometry of bone marrow biopsies in chronic myeloproliferative disorders with associated thrombocytosis-features of significance for the diagnosis of primary (essential) thrombocythaemia. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1988;413(5):407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Thiele J, Kuemmel T, Sander C, Fischer R. Ultrastructure of bone marrow tissue in so-called primary (idiopathic) myelofibrosis-osteomyelosclerosis (agnogenic myeloid metaplasia). I. Abnormalities of megakaryopoiesis and thrombocytes. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1991;23(1):93–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tavassoli M Modulation of megakaryocyte emperipolesis by phlebotomy: megakaryocytes as a component of marrow-blood barrier. Blood cells. 1986;12(1):205–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tanaka M, Aze Y, Shinomiya K, Fujita T. Morphological observations of megakaryocytic emperipolesis in the bone marrow of rats treated with lipopolysaccharide. J Vet Med Sci. 1996;58(7):663–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stahl CP, Zucker-Franklin D, Evatt BL, Winton EF. Effects of human interleukin-6 on megakaryocyte development and thrombocytopoiesis in primates. Blood. 1991;78(6):1467–1475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Larocca LM, Heller PG, Podda G, et al. Megakaryocytic emperipolesis and platelet function abnormalities in five patients with gray platelet syndrome. Platelets. 2015;26(8):751–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kahr WH, Savoia A, Pluthero FG, et al. Megakaryocyte and platelet abnormalities in a patient with a W33C mutation in the conserved SH3-like domain of myosin heavy chain IIA. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2009;102(6):1241–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Centurione L, Di Baldassarre A, Zingariello M, et al. Increased and pathologic emperipolesis of neutrophils within megakaryocytes associated with marrow fibrosis in GATA-1(low) mice. Blood. 2004;104(12):3573–3580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tanaka M, Aze Y, Fujita T. Adhesion molecule LFA-1/ICAM-1 influences on LPS-induced megakaryocytic emperipolesis in the rat bone marrow. Vet Pathol. 1997;34(5):463–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Scott MA, Friedrichs KR. Megakaryocyte podography. Vet Clin Pathol. 2009;38(2):135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cunin P, Machlus KR, Boilard E, Morris A, Italiano JE, Nigrovic PA. Emperipolesis is a novel cell-in-cell phenomenon that mediates transfer of neutrophil membrane to megakaryocytes and platelets [abstract]. Gordoin Conference in Platelet and Megakaryoctre Biology; 2017; Verona, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fitzgerald JR, Foster TJ, Cox D. The interaction of bacterial pathogens with platelets. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2006;4(6):445–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hamzeh-Cognasse H, Damien P, Chabert A, Pozzetto B, Cognasse F, Garraud O. Platelets and infections - complex interactions with bacteria. Frontiers in immunology. 2015;6:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Boudreau LH, Duchez AC, Cloutier N, et al. Platelets release mitochondria serving as substrate for bactericidal group IIA-secreted phospholipase A2 to promote inflammation. Blood. 2014;124(14):2173–2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mangi MH, Mufti GJ. Primary myelodysplastic syndromes: diagnostic and prognostic significance of immunohistochemical assessment of bone marrow biopsies. Blood. 1992;79(1):198–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Culture Schulze H., Expansion, and Differentiation of Murine Megakaryocytes from Fetal Liver, Bone Marrow, and Spleen. Current protocols in immunology. 2016;112:22F 26 21–22F 26 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ivetic N, Nazi I, Karim N, et al. Producing megakaryocytes from a human peripheral blood source. Transfusion. 2016;56(5):1066–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Reems JA, Pineault N, Sun S. In vitro megakaryocyte production and platelet biogenesis: state of the art. Transfusion medicine reviews. 2010;24(1):33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Fuentes R, Wang Y, Hirsch J, et al. Infusion of mature megakaryocytes into mice yields functional platelets. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(11):3917–3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhang J, Varas F, Stadtfeld M, Heck S, Faust N, Graf T. CD41-YFP mice allow in vivo labeling of megakaryocytic cells and reveal a subset of platelets hyperreactive to thrombin stimulation. Experimental hematology. 2007;35(3):490–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tiedt R, Schomber T, Hao-Shen H, Skoda RC. Pf4-Cre transgenic mice allow the generation of lineage-restricted gene knockouts for studying megakaryocyte and platelet function in vivo. Blood. 2007;109(4):1503–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yang M, Li K, Chui CM, et al. Expression of interleukin (IL) 1 type I and type II receptors in megakaryocytic cells and enhancing effects of IL-1beta on megakaryocytopoiesis and NF-E2 expression. Br J Haematol. 2000;111(1):371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Navarro S, Debili N, Le Couedic JP, et al. Interleukin-6 and its receptor are expressed by human megakaryocytes: in vitro effects on proliferation and endoreplication. Blood. 1991;77(3):461–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Negrotto S C JDG, Lapponi MJ, et al. Expression and functionality of type I interferon receptor in the megakaryocytic lineage. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2011;9(12):2477–2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Takeda T, Unno H, Morita H, et al. Platelets constitutively express IL-33 protein and modulate eosinophilic airway inflammation. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2016;138(5):1395–1403 e1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]