Abstract

Background/Aim: Although the trends of surgical treatment in vulvar cancer patients are towards less extended resections, a significant number of cases are still diagnosed with locally advanced diseases imposing performing extended resections. The aim of this paper is to identify the prognostic factors for the development of early postoperative complications following vulvar surgery. Patients and Methods: Between 2017 and 2019, 145 patients with vulvar cancer were submitted to surgery with a curative intent. Results: Among these cases there were 93 cases diagnosed with early stages of the disease and 52 cases diagnosed with advanced stages. The risk of postoperative complications was significantly influenced by: i) the stage of the disease, ii) the preoperative levels of serum albumin, iii) the status of the resection margins, iv) previous history of irradiation, v) length of hospital stay and vi) association of comorbidities. Conclusion: Vulvar cancer surgery for locally advanced disease is still associated with high rates of postoperative complications, and an attentive selection of cases submitted to surgery is mandatory.

Keywords: Postoperative complications, vulvar cancer, extended resections

Vulvar cancer represents nowadays the fourth most commonly encountered gynecological cancer after uterine corpus, uterine cervix and ovarian cancer (1). This pathology has been encountered for a long period of time with a peak incidence between 65 and 75 years of age; however, due to the high number of cases presenting with human papilloma virus (HPV) infection, a significant number of cases will develop this malignant disease at a younger age. Fortunately, these cases usually present less aggressive tumors and a more conservative treatment might be proposed (2,3). Under such conditions, cases presenting early stages of the disease may allow for local limited resections; however, following such kind of surgery, a significant number of cases will develop local recurrences, necessitating more extended surgical procedures (2). Moreover, patients diagnosed during advanced stages of the disease might need extended perineal resections in association with inguinal lymph node dissection in order to achieve a good local control of the disease (2). Interestingly, a certain proportion between the extent of the resection and the risk of postoperative complications has been established (3). The aim of this paper is to study the influence of the type of surgery on the early postoperative outcomes, as well as to identify other prognostic factors, which might influence the short-term evolution of surgically-treated vulvar cancer patients.

Patients and Methods

Upon approval from the Ethical Committee of Cantacuzino Hospital (reference no 23/2019), we retrospectively reviewed data from patients submitted to surgery for vulvar cancer between 2017 and 2019. Among the 145 identified patients, there were 93 cases diagnosed during early stages of the disease, while 52 cases were diagnosed at advanced stages. Postoperative complications were classified according to the Dindo – Clavien scale (4).

Results

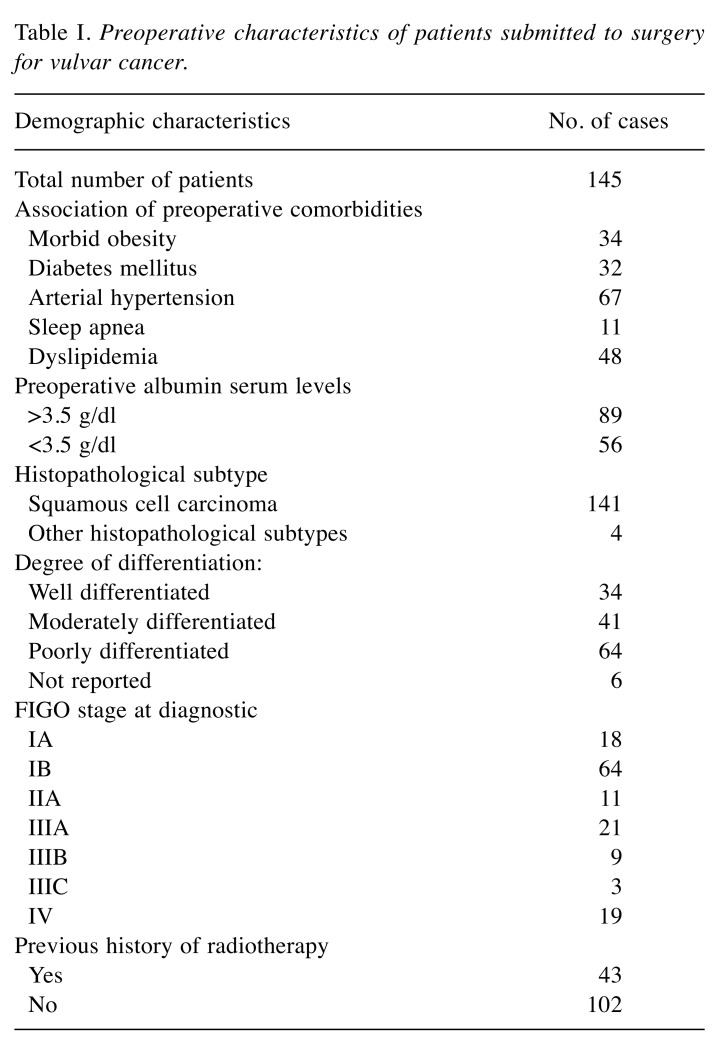

The median age of the patients introduced in the current study was 67 years (range:49-78 years). Patients presenting with advanced stages of the disease were of an older age when compared to cases diagnosed at early stages of the disease (71 years versus 64 years, p=0.657). As for the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology (FIGO) stages (5), there were: i) 18 cases diagnosed at FIGO stage IA, ii) 64 cases diagnosed at FIGO stage IB, iii) 11 cases diagnosed at FIGO stage II, iv) 21 cases diagnosed at FIGO stage IIIA, v) 9 cases at FIGO stage IIIB, vi) 3 cases at FIGO stage IIIC and vii) 19 cases at FIGO stage IV. As for the histopathological type, most cases were diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma (141 of 145 cases). In all cases the histopathological diagnostic was established by a preoperative biopsy. Preoperative characteristics are shown into Table I.

Table I. Preoperative characteristics of patients submitted to surgery for vulvar cancer.

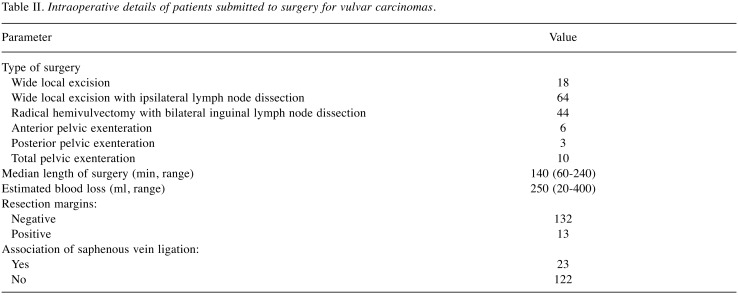

Concerning the type of surgery, there were: i) 18 cases submitted to wide local excision, ii) 64 submitted to wide local excision with ipsilateral lymph node dissection, iii) 44 submitted to radical hemivulvectomy with bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection by using separate incisions, iv) 6 submitted to anterior infralevator pelvic exenteration, v) 3 submitted to posterior infralevator pelvic exenteration and vi) 10 submitted to total infralevator pelvic exenteration. Intraoperative details are shown in Table II.

Table II. Intraoperative details of patients submitted to surgery for vulvar carcinomas.

Among the 145 cases, the histopathological studies confirmed the presence of negative resection margin in 132 cases, while in the remaining 13 cases microscopic positive margins were encountered. In order to maximize the radicality of surgery, 19 cases were submitted to pelvic exenteration, among which 15 appeared negative for resection margins using histopathological analyses, and only four patients presented microscopic tumoral involvement of the margins. The median length of hospital stay was six days (range=2-23 days) and it was significantly associated with the complexity of resection. More specifically, patients diagnosed at early stages and treated by local limited excision reported a median hospital stay of 3 days (range=2-5 days), while patients treated by extended resections reported a median hospital stay of 8 days (range=4-23 days, p=0.0001).

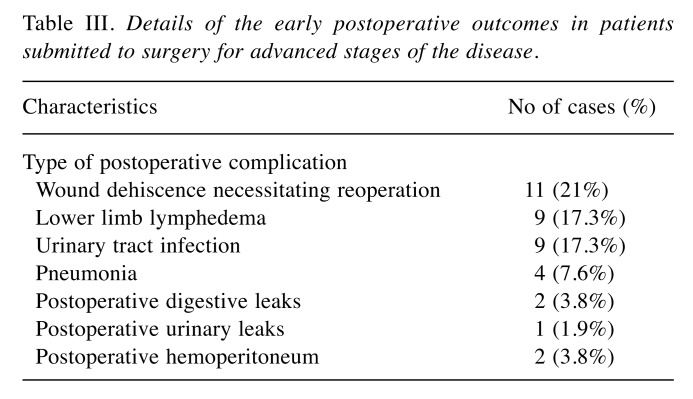

Early postoperative complications were encountered in 11 of 93 cases (11%) diagnosed at early stages of the disease and in 20 cases submitted to surgery for advanced stage disease (38%) (p=0.02). In the meantime, the complexity of the type of postoperative complication was significantly higher among patients submitted to surgery for advanced stages of this malignancy. In patients diagnosed at early stages, the principal complication was wound dehiscence associated with a prolonged healing process (considered as Dindo – Clavien grade 2 complications and reported in 8 cases). In more advanced stages postoperative predominant complications involved the need for re-operation (classified as Dindo – Clavien 3 grade).These were reported in 13 cases. Moreover, the rates of postoperative lower limb lymphedema were significantly higher among patients submitted to surgery for advanced stages of the disease compared to those at early stages (4.3% versus 17.3%, p=0.01). None of these patients died within the first 30 postoperative days.

Details of the early postoperative outcomes in patients submitted to surgery for advanced stages of the disease are presented in Table III.

Table III. Details of the early postoperative outcomes in patients submitted to surgery for advanced stages of the disease.

When it comes to patients submitted to surgery for advanced stages of the disease, we also investigated the influence of other presumptive prognostic factors on the risk of postoperative complications, such as i) preoperative albumin levels, ii) status of resection margins, iii) previous history of irradiation, iv) length of hospital stay, v) association of saphenous vein ligation, vi) degree of tumoral differentiation and vii) association of comorbidities. Univariate analysis showed that postoperative complications were significantly associated with i) lower levels of albumin levels (p=0.002), ii) positive resection margins (p=0.003), iii) previous history of irradiation (p=0.01), iv) association of comorbidities (p=0.01) and v) length of hospital stay (p=0.001). The rates of postoperative complications were not significantly influenced by the association of saphenous vein ligation or by the degree of differentiation of the tumors.

Discussion

The most commonly performed therapeutic strategies in vulvar cancer patients include chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery; however, due to the low incidence of the disease large randomized trials are still missing, while the most appropriate therapeutic strategy represents a real challenge (6). Although the actual trend is to perform minimal surgical procedures in association with chemo-radiation, in certain cases radical surgery might be the best option of therapeutic intervention (3).

In cases treated by surgery with curative intent it has been widely demonstrated that the most important prognostic factors for the long-term outcomes are represented by the stage at diagnosis, the status of the resectional margins and of the retrieved lymph nodes, the five year survival rates decreasing from 78% in the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology (FIGO) stage I to 13% in FIGO stage IV disease (7). However, it seems that the stage at diagnosis also influences the risk of postoperative complications. This aspect can be explained by the fact that larger tumors necessitate more extended local or regional resections.

As for the type of incision that should be performed in such cases, “the butterfly incision” providing an en bloc vulvectomy and inguinal lymph node dissection seemed to be associated with significant postoperative complications and has now been mainly replaced by the “triple incision technique”, which allows for the vulvar resection and inguinal lymph node dissection through separate incisions (8,9). However, the type of incision should be tailored to each patient in order to achieve negative resection margins and, at the same time, the excision should not be too wide so as to protect from exposing the wound dehiscence which can lead to prolonged, impaired healing. When it comes to the extent of the tumor free resection margins, this subject is strongly debated; certain authors support the notion that a width of 8 mm is enough, while other studies consider that the safety value of this parameter is at 10 mm (6). An interesting study by de Hullu et al., have focused on the influence of the resection margins on the long term outcomes of vulvar cancer patients, where it was demonstrated that no patient with microscopical resectional margins of at least 8 mm developed local recurrence; however, half the patients with macroscopic negative margins of at least 1 cm presented in fact positive microscopic margins at 8 mm (10). In this study the authors advised on macroscopic resection margins of 2 cm in order to minimize the risk of positive microscopic margins (10).

When it comes to the cases in which radical excision is not enough to provide radical resection, these cases are considered as locally advanced and might necessitate performing more extensive procedures, such as exenterative procedures (11). In such cases, neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy might be considered in order to diminish the extent of visceral sacrifice, which represents another important problem for vulvar cancer patients and improve their quality of life (12). Therefore, multiple studies have been conducted on this theme and demonstrated that the higher the number of aggressive and extensive surgical procedures are proportionally associated with lower levels of quality of life. In the study conducted by Gunther et al., the authors included 199 patients submitted to surgery for vulvar cancer, who demonstrated that local excision was more frequently associated with a better quality of life, including a better social, emotional and cognitive functioning when compared to patients treated with radical vulvectomy (13). Moreover, the extent of lymph node dissection was also correlated with other postoperative complications, such as insomnia and lymphedema. However, it should be emphasized that the status of the resection margins and of the number of retrieved lymph nodes remain the most important prognostic factors with regard to the local and distant recurrence rates. Therefore, a tailored treatment for each patient, especially at younger ages, remains crucial.

In order to maximize the effect of surgery and minimize the risk of postoperative complications, a careful selection of the candidates for surgery is important. Similar to other solid tumors, it seems that in vulvar cancer the preoperative levels of serum albumin significantly influence the short-term outcomes (12,13). More specifically, a lower level of preoperative albumin caused by malnutrition and albumin synthesis suppression as a consequence of a systemic inflammatory response is responsible for a higher rate of postoperative morbidity (14-17). In a recent study conducted by Bekos et al. in 2019, the authors included 103 patients submitted to vulvar cancer surgery, nine of whom presented with preoperative hypoalbuminemia (18). Among these patients, the rates of postoperative complications were higher when compared to patients with a normal nutritional status. Moreover, the authors underlined the fact that lower preoperative serum albumin levels were associated with significantly poorer rates of overall survival in both univariate and multivariate analyses, and thus, demonstrating the importance of this parameter (18). In another study that also investigated the influence of the preoperative serum levels of albumin on the postoperative outcomes, the authors demonstrated that hypoalbuminemia is significantly associated with the risk of wound complication even after adjusting for age, body mass index, preoperative hematocrit or association of diabetes (19).

Another factor that appears to influence the risk of systemic complications after surgery for vulvar cancer is represented by the length of hospital stay. Prolonged hospitalization might predispose these patients to the development of systemic complications and advocate for early discharge with suction drains in situ. Early removal of drainage tubes (within the first 3 postoperative days) seem to predispose to the apparition of local complications, such as wound dehiscence, wound infection and lymphocyst formation; on the other hand, a prolonged hospital stay (until the drainage can be removed) seems to increase the risk of postoperative complications, such as pulmonary complications; therefore, certain authors recommend early postoperative discharge with in situ drainage tubes in order to prevent the development of further complications (20).

An interesting study on postoperative complications and readmission rates following vulvar surgery was conducted by Dorney et al. The study included 363 patients submitted to surgery for vulvar cancer and demonstrated that the risk of readmission as well as the postoperative outcomes were significantly influenced by the presence of comorbidities, the type of surgical procedure, the nodal assessment, the initial hospital stay and discharge to a post-acute care facility (21). Interestingly, contrary to our results, in this study the previous history of radiation therapy did not significantly influence the risk of postoperative complications.

Vulvar surgery is still associated with important risks of postoperative complications, the rates of morbidity being significantly influenced by the stage at diagnosis, the extent of surgery, the associated preoperative comorbidities and the poor nutritional status. We suggest that an attentive selection of patients for this invasive procedure is mandatory so to lower the rates of postoperative complications.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Authors’ Contributions

NB Performed surgical procedures, MV and IB were part of the surgical team, SD and IB performed data analysis and prepared the tables, IB prepared revised the final draft of the manuscript and advised about surgical oncology procedures. IB – All Authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the project entitled „Multidisciplinary Consortium for Supporting the Research Skills in Diagnosing, Treating and Identifying Predictive Factors of Malignant Gynecologic Disorders”, project number PN-III-P1-1.2-PCCDI2017-0833.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. PMID: 23335087. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Del Pino M, Rodriguez-Carunchio L, Ordi J. Pathways of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 2013;62:161–175. doi: 10.1111/his.12034. PMID: 23190170 DOI: 10.1111/his.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rei M, Mota R, Paiva V, Duarte A, Costa J, Costa A. Recurrence of vulvar carcinoma: A multidisciplinary approach. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2019;29:38–39. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2019.06.004. PMID: 31297429. DOI: 10.1016/j.gore.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibanes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C, Graf R, Vonlanthen R, Padbury R, Cameron JL, Makuuchi M. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–196. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. PMID: 19638912. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers LJ, Cuello MA. Cancer of the vulva. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143(Suppl 2):4–13. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12609. PMID: 30306583 DOI: 10.1002/ijgo.12609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woelber L, Kock L, Gieseking F, Petersen C, Trillsch F, Choschzick M, Jaenicke F, Mahner S. Clinical management of primary vulvar cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2315–2321. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.007. PMID: 21733674. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beller U, Quinn MA, Benedet JL, Creasman WT, Ngan HY, Maisonneuve P, Pecorelli S, Odicino F, Heintz AP. Carcinoma of the vulva. FIGO 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(Suppl 1):S7–S27. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60028-3. PMID: 17161169. DOI: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magrina JF, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Weaver AL, Gaffey TA, Webb MJ, Podratz KC, Cornella JL. Primary squamous cell cancer of the vulva: radical versus modified radical vulvar surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;71:116–121. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5149. PMID: 9784331. DOI: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin JY, DuBeshter B, Angel C, Dvoretsky PM. Morbidity and recurrence with modifications of radical vulvectomy and groin dissection. Gynecol Oncol. 1992;47:80–86. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90081-s. PMID: 1427407, DOI: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90081-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Hullu JA, Hollema H, Lolkema S, Boezen M, Boonstra H, Burger MP, Aalders JG, Mourits MJ, Van Der Zee AG. Vulvar carcinoma. The price of less radical surgery. Cancer. 2002;95:2331–2338. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10969. PMID: 12436439. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.10969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman MS. Squamous-cell carcinoma of the vulva: locally advanced disease. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;17:635–647. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6934(03)00051-8. PMID: 12965136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Hullu JA, van dA I, Oonk MH, Van Der Zee AG. Management of vulvar cancers. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:825–831. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.03.035. PMID: 16690244. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunther V, Malchow B, Schubert M, Andresen L, Jochens A, Jonat W, Mundhenke C, Alkatout I. Impact of radical operative treatment on the quality of life in women with vulvar cancer--a retrospective study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:875–882. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.03.027. PMID: 24746935. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brezean I, Aldoescu S, Catrina E, Valcu M, Ionut I, Predescu G, Degeratu D, Pantea I. Pelvic and abdominal-wall actinomycotic infection by uterus gateway without genital lesions. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2010;105:123–125. PMID: 20405693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balescu I, Bacalbasa N, Tomescu D, Meruta A, Vilcu M, Brezean I. Perineal Reconstructions after Extended Resections for Locally Advanced Vulvar Cancer Conference: 4th Congress of the Romanian Society for Minimal Invasive Surgery in Gynecology. Location: Bucharest, Romania. Proceedings of the 4th Congress of the Romanian Society for Minimal Invasive Surgery in Gynecology/Annual Days of the National Institute for Mother and Child Health Alessandrescu-Rusescu. 2019:93–97. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoica C, Brezean I, Vîlcu M, Bacalbasa N, Balescu I. Total vulvectomy with bilateral groin lymph node dissection for vulvar sarcoma - a case report. Conference: 35th Balkan Medical Week on Healthy Ageing - An Endless Challenge. Location: Athens, Greece. Date: Sep 25-27. Proceedings of the 35th Balkan Medical Week. 2018:405–409. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rusu MC, Ilie AC, Brezean I. Human anatomic variations: common, external iliac, origin of the obturator, inferior epigastric and medial circumflex femoral arteries, and deep femoral artery course on the medial side of the femoral vessels. Surg Radiol Anat. 2017;39:1285–1288. doi: 10.1007/s00276-017-1863-6. PMID: 28451829. DOI: 10.1007/s00276-017-1863-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bekos C, Polterauer S, Seebacher V, Bartl T, Joura E, Reinthaller A, Sturdza A, Horvat R, Schwameis R, Grimm C. Pre-operative hypoalbuminemia is associated with complication rate and overall survival in patients with vulvar cancer undergoing surgery. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300:1015–1022. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05278-7. PMID: 31468203. DOI: 10.1007/s00404-019-05278-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan SA, Van Le L, Liberty AL, Soper JT, Barber EL. Association between hypoalbuminemia and surgical site infection in vulvar cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;142:435–439. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.06.021. PMID: 27394633. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burbos N, Abu-Freij M, Perez-Morales M, Nieto JJ. Early postoperative discharge following radical vulvectomy and bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy for vulvar carcinoma. Gynecol Surg. 2011;8:89–91. DOI : 10.1007/s10397-009-0504-4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorney KM, Growdon WB, Clemmer J, Rauh-Hain JA, Hall TR, Diver E, Boruta D, Del Carmen MG, Goodman A, Schorge JO, Horowitz N, Clark RM. Patient, treatment and discharge factors associated with hospital readmission within 30days after surgery for vulvar cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144:136–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.11.009. PMID: 27836203. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]