Abstract

Aim: The aim of this study was to detect clinical factors predictive of loss of visual acuity after treatment in order to develop a predictive model to help identify patients at risk of visual loss. Patients and Methods: This was a retrospective review of patients who underwent interventional radiotherapy (brachytherapy) with 106Ru plaque for primary uveal melanoma. A predictive nomogram for visual acuity loss at 3 years from treatment was developed. Results: A total of 152 patients were selected for the study. The actuarial probability of conservation of 20/40 vision or better was 0.74 at 1 year, 0.59 at 3 years, and 0.54 at 5 years after treatment. Factors positively correlated with loss of visual acuity included: age at start of treatment (p=0.004) and longitudinal basal diameter (p=0.057), while distance of the posterior margin of the tumor from the foveola was inversely correlated (p=0.0007). Conclusion: We identified risk factors affecting visual function and developed a predictive model and decision support tool (AVATAR nomogram).

Keywords: Plaque brachytherapy, interventional radiotherapy, nomogram, prediction model, 106Ru, uveal melanoma, visual acuity

Local disease control and the preservation of visual acuity are the main objectives in conservative treatment of uveal melanomas. Radiotherapy is one of the treatments that at many sites allows organ and function preservation (1-5).

Interventional radiotherapy (brachytherapy) is the standard treatment for uveal melanoma, although local tumor control rates in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) (6) and other reports are excellent for small to medium size choroidal melanoma, long-term visual acuity outcomes are poor for many patients. Radiation retinopathy, radiation optic neuropathy, and radiation-induced macular edema remain devastating sources of vision loss following radiation therapy for uveal melanoma. Early treatments with laser therapy, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapies and steroid-based therapies for radiation-induced macular edema did not show remarkable effects on retinal thickness and visual acuity. In contrast, preventive management with scatter laser and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy for radiation-induced macular edema has been shown to reduce retinal swelling and improve visual acuity in the long-term following radiation therapy (7,8). For this reason, more recently, studies have directed therapies towards the prevention of radiation retinopathy rather than treatment after signs that damage has already occurred (9). With this aim, the identification of patients at risk of developing loss of visual acuity who might be candidates for preventive treatment is essential. Since there is a complex interplay of different factors that influence toxicity from interventional radiotherapy, determining the overall risk of vision loss based on individual tumor characteristics and the presence of ocular and systemic disease may help in patient selection. In addition, more and more decision support tools based on predictive models are being developed in order to personalize the proposed therapeutic approach. Many authors speak of a virtual patient, defined as AVATAR, in fact, through tools therapies can be virtually tested and the virtual outcomes be determined before treatment (10,11).

The first two aims of this study were to document visual outcome in patients with small-medium size choroidal melanoma treated with 106Ru interventional radiotherapy at the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS and to evaluate changes in visual acuity over time in response to treatment. The third aim was to identify clinical predictive factors for visual acuity loss after treatment in order to develop a predictive model to help identify patients at risk of visual loss (12,13).

Patients and Methods

This was a retrospective review of all consecutive patients who underwent interventional brachytherapy with 106Ru plaque, for primary uveal melanoma at our Interventional Oncology Center between 2006-2014; all the anonymized data were retrieved from the intranet hospital multidivisional electronic database Spider's Net in the framework of our institutional Consortium for Brachytherapy Data Analysis (COBRA) system (14).

Inclusion criteria. Patients eligible for the study were those diagnosed with dome-shaped small to medium size choroidal melanoma. Patients with posterior tumor margin within 1.5 mm from the foveola were excluded because of the high probability of developing radiation sequelae and visual loss. Patients previously treated with other modalities and those with minimal plaque displacement during the follow-up visit were excluded from our analysis. Patients with poor baseline visual acuity (<20/200) were excluded due to the impossibility of assessing a worsening of visual acuity caused by treatment toxicity. Patients with iris or ciliary body melanoma were excluded due to the risk of developing a secondary cataract which, subsequently resolved with therapeutic formation, might be considered a significant visual decline.

Interventional radiotherapy protocol. The diagnosis of choroidal melanoma was made on the basis of the ophthalmoscopic evaluation, A-B scan ultrasonography and fundus photography. A metastatic workup, including liver function test and liver ultrasound was performed before treatment for each patient and was negative in all cases. All patients gave their signed informed consent. The baseline patient data of demographic features such as age and gender, systemic illness (diabetes mellitus, hypertension), prior history of malignancy, and prior ophthalmological conditions were recorded. Pretreatment tumor data included TNM classification according to the eighth edition (15), tumor thickness, basal diameter and tumor distance to the posterior margin of the fovea measured by ultrasound using A-B scan standardized technique. Each case was evaluated in a weekly multidisciplinary meeting comprising an ocular oncologist, radiation oncologist and clinical physicist. The radioisotope used was 106Ru and the prescription dose was 100 Gy to the tumor apex. The dose calculation was performed using the software Plaque Simulator (plaque margin in all directions simulator; BEBIG Isotopenund Medizintechnik GmbH, Berlin Germany) calculating the estimated dose to organs at risk according to the activity of the plaque used. The size of the episcleral plaque was selected to provide 1 mm around the tumor edge. The plaque was applied to the patient under local anesthesia, and the lesion localization was performed by the use of transillumination or indirect ophthalmoscopy, depending on tumor location. Confirmation of intraoperative plaque placement were performed by experienced diagnostic ophthalmic echographers to ensure that the plaque was centered on the tumor base and all tumor margins were covered by the plaque. The procedure was performed following the INTERACTS protocol for quality assurance (16).

Evaluation of visual acuity. The best corrected visual acuity in the affected eye was measured using the Snellen chart by an ophthalmologist before treatment and at follow-up examinations scheduled at 4-months interval up to 2 years and at 6-month intervals thereafter. Changes in visual acuity compared with the initial visit were registered at follow-up visits. Loss of visual acuity was considered as any decrease in visual acuity of at least two lines on a standard Snellen eye chart.

Statistical analysis and endpoints. The covariates of interest were statistically tested against the outcome of visual acuity loss at 3 years with Mann-Whitney U-test or chi-squared test depending on the type of covariate: the former for numerical ones, and the latter for categorical ones. Covariates which had a statistically significant (p<0.05) univariate correlation with the outcome were included in a logistic regression model, and through stepwise selection, the best model was chosen according to minimum Akaike Information Criteria (17). Finally, an estimate of the model performance was computed via area under the receiver operating characteristic curve on 1,000 bootstrap samples.

Results

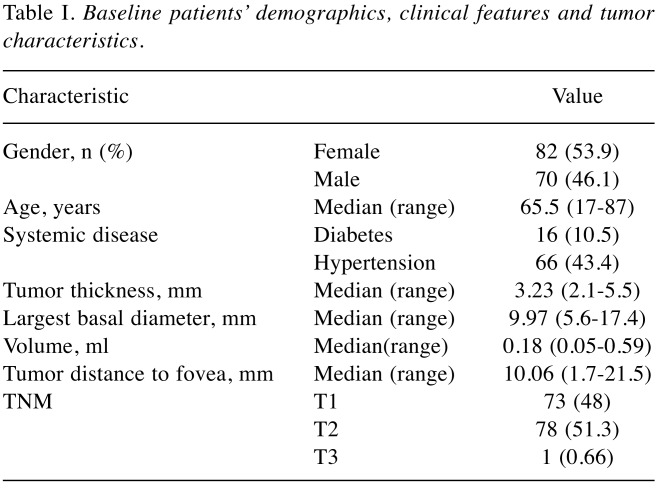

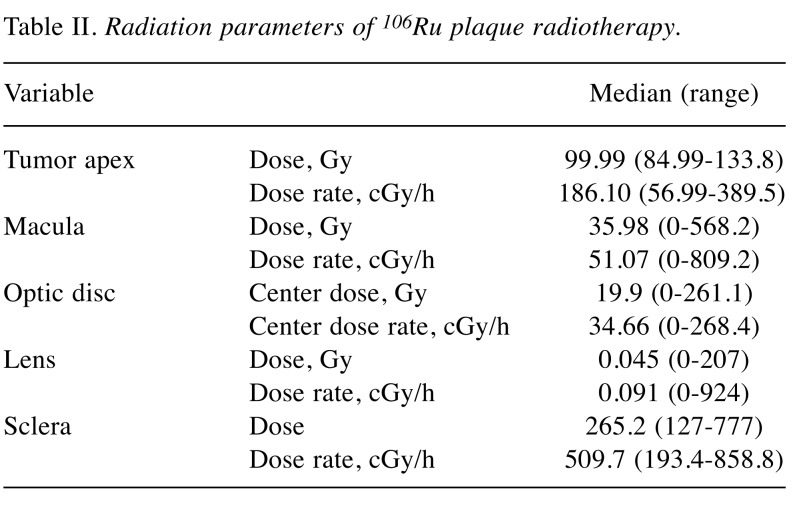

Between December 2006 and December 2014, 239 cases of uveal melanoma (239 eyes) were treated with 106Ru plaque. Based on these inclusion criteria, 152 patients were selected for the study. The baseline patient demographics, clinical features and tumor characteristics are summarized in Table I. According to the eighth edition (15) of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system 73 (48%) patients were T1, 78 (51.3%) T2 and 1 (0.66%) T3 at diagnosis. Depending on tumor basal diameter, the following plaques (Bebig, Berlin, Germany) were used: CCA (PD: 15.3 mm) in 56 (36.8%) patients; CCD (PD: 17.9 mm) in 28 (18.4%); CCB (PD: 20.2 mm) in 39 (25.6%); COB (PD: 19.8 mm) in 27 (17.8%) and CCC (PD: 24.8 mm) in two (1.3%) patients. The radiation characteristics are detailed in Table II. Follow-up ranged from 30.0 to 104.0 months (median=67.0 months); all patients included in the study had regular follow-up.

Table I. Baseline patients’ demographics, clinical features and tumor characteristics.

Table II. Radiation parameters of 106Ru plaque radiotherapy.

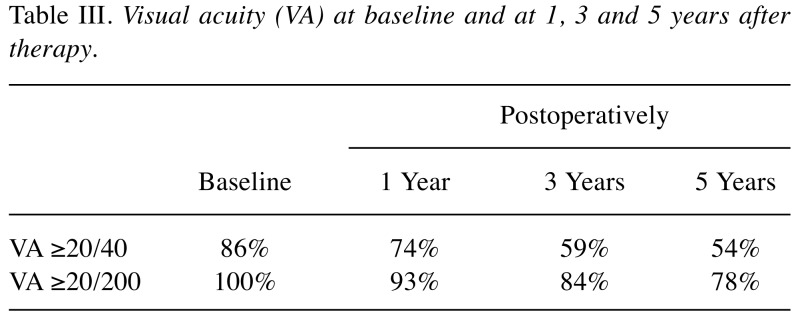

Visual acuity outcome. Primary objective included the study of visual acuity changes after Interventional Radiotherapy. At the time of the treatment, 130 patients (86%) had good vision of 20/40 or better in the tumor-affected eye, while there were 152 (100%) patients with initial visual acuity of 20/200 or better (Table III).

Table III. Visual acuity (VA) at baseline and at 1, 3 and 5 years after therapy.

The actuarial probability of conservation of 20/40 or better was 0.74 at 1 year, 0.59 at 3 years, 0.54 at 5 years after treatment. The actuarial probability of conservation of 20/200 or better was 0.93 at 1 year, 0.84 at 3 years, 0.78 at 5 years after treatment. Best corrected vision after refraction, 3 years postoperatively, showed that 69 (45.4%) patients out of 152 had vision loss, while 83 (54.6%) experienced no change in visual acuity.

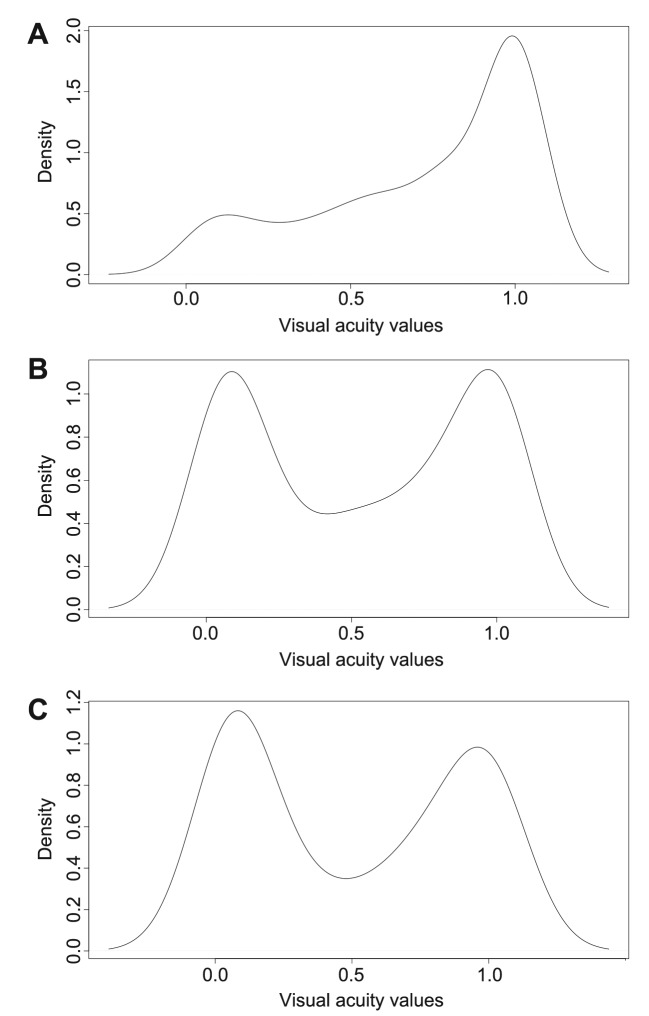

Visual acuity changes over time. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the best corrected visual acuity in the study subjects starting from baseline until 5 years postoperatively. Figure 1A shows the baseline distribution of visual acuity. Most of the patients affected by small to medium size choroidal melanoma had good visual acuity before treatment. Figure 1B shows that the greatest loss of vision occurred in the interval of time between years 1 and 3, indicating that this is the time interval in which most of the toxic effects occur. In the interval of time between years 3 and 5 (Figure 1C), only a few patients experienced a reduction in visual acuity, thus allowing us to determine that the visual acuity achieved in the third year after treatment was maintained in most cases.

Figure 1. Graphical representation of the visual acuity data distribution in the population included in the nomogram. Values towards 1 on the horizontal axis represent good values whereas values towards 0 represent worse visual acuity. It is possible to see how the single humped curve present at baseline tends to shift towards a double humped curve at 3 years, while remaining substantially stable at 5 years. A: Representation of the baseline visual acuity distribution of patients included in our model. B: By analyzing the shift of the visual acuity on the curve it is possible to determine that the greatest vision loss occurred between years 1 and 3, indicating that this is the time interval in which most of the toxic effects occur. C: Between years 3 and 5, only a few patients experienced a reduction in visual acuity, as is apparent from comparing this curve with that in B; most kept the visual acuity achieved in the third year after treatment.

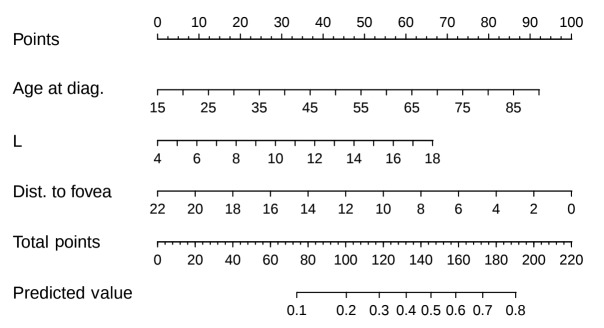

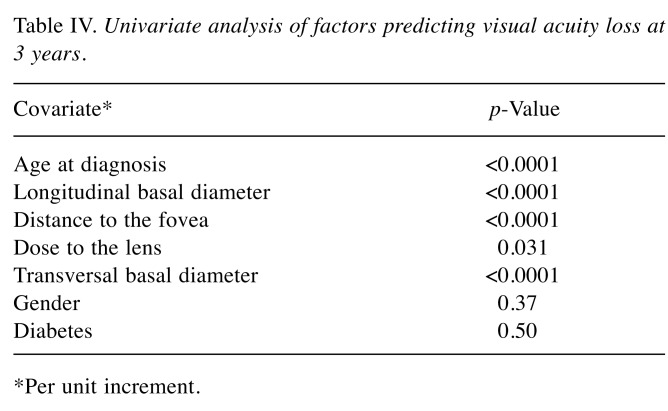

Visual acuity predictive model. As stated in the Statistical analysis and endpoints section, a logistic regression model was built from the significant variables at the univariate plus stepwise selection. We then represented this logistic regression model as a nomogram (Figure 2), a decision support system in which a clinician can input the values of these covariates, and in which summing up the scores gives a probability for visual acuity loss at 3 years. The change of visual acuity over time in response to treatment allowed us to identify 3 years postoperatively as the best time point for calculation of predicted risk. In Table IV, a summary of univariate testing is reported, showing clinical and dosimetric parameters most predictive of significant risk of vision loss. A higher age at diagnosis (p<0.001) and a higher basal diameter (p<0.001) were associated with increased risk of vision loss; a greater distance of the posterior tumor margin from the foveola or the optic disk was associated with reduced risk of vision loss (p<0.001).

Figure 2. Nomogram to predict risk of visual acuity loss after 3 years. diag: Diagnosis; Dist: distance; L: longitudinal basal diameter.

Table IV. Univariate analysis of factors predicting visual acuity loss at 3 years.

*Per unit increment.

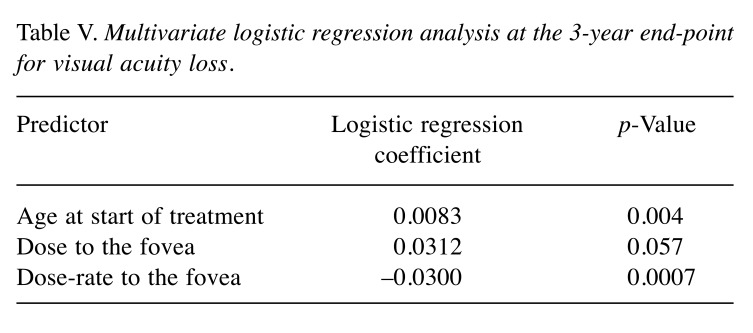

On multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table V), these factors remained significant contributors to loss of visual acuity at 3 years (age: p=0.004; longitudinal basal diameter: p=0.057; and distance to the fovea: p=0.0007, respectively). No association with sex, systemic hypertension, nor tumor thickness was found. An association with diabetes had been found in a preliminary analysis including patients with baseline best corrected visual acuity ≤0.1, who were excluded in the final analysis.

Table V. Multivariate logistic regression analysis at the 3-year end-point for visual acuity loss.

Discussion

In this study, we report on visual acuity after interventional radiotherapy with ruthenium plaque for choroidal melanoma. The study focused on three different analyses: visual acuity outcome, decline in visual acuity over time after brachytherapy treatment, and the development of a visual acuity predictive model. At the time of treatment, our study population presented good baseline visual acuity in the affected eye: ≥20/200 in 100% of patients and ≥20/40 in 86% of patients; after 3 years of follow-up, 59% of patients retained a visual acuity of ≥20/40 and 84% acuity of ≥20/200.

Other studies reporting on visual outcomes after ruthenium plaque for choroidal melanoma comparable in terms of the tumor size, at 3 years post-treatment, were those from Damato et al. (18), with 78% ≥20/40 and 90% ≥20/200, and from Summanem et al. (19), with a final visual acuity of 20/200 preserved in 55% of patients.

In the COMS report examining visual outcomes at 3 years after 125I brachytherapy, 43% of patients had a visual acuity of 20/200 or worse and 49% had a loss of six or more lines from the pretreatment level (20). Patient selection and the use of ruthenium plaque are probably important factors for our success in visual acuity outcome.

From the fact that our population was composed of patients with a relatively early diagnosis of uveal melanoma, affected by tumors with a maximum thickness not greater than 5.5 mm, it follows that the baseline visual acuity was good. Visual acuity before treatment has been considered an important prognostic factor for visual outcome, in fact Cruess et al. had noted that patients with pretreatment visual acuity of 20/40 or better were most likely to have the best visual prognosis (21).

Additionally, the use of ruthenium plaque, offering less toxicity compared to other radionuclides, was decisive for the final functional outcome and for the result that 54.5% of the population had experienced no change in visual acuity 3 years after treatment. There are several possible mechanisms for loss of visual acuity, each acting in a certain period of time in brachytherapy treatment. Baseline low visual acuity can be caused by subfoveal tumor extension or tumor-induced exudative retinal detachment involving the fovea. Post-treatment loss can be immediate due to direct radiation damage to macula and the optic disc due to the isodoses of treatment, or late due to the release of vasoproliferative factors and induced radiation optic neuropathy and radiation maculopathy (18). Radiation optic neuropathy has been reported to occur after a mean of 16.1 months (range=6.8-37 months) postplaque. The time to developing maculopathy following irradiation has been described to range from 8 to 74.9 months, with a mean of 25.6 months (22). In our population, the median time to developing radiation optic neuropathy was 41 months postplaque, the median time to developing radiation maculopathy was found to be 31 months after plaque treatment and the range was 0-104 months. In order to evaluate the decline of visual acuity over time after brachytherapy treatment, visual acuity distribution curves were analyzed before the start of treatment and 1, 3 and 5 years after therapy. The population analyzed had good visual acuity before treatment, in detail 100% of patients ≥20/200 and 86% of patients ≥20/40. Our results were due to the selection of patients with small to medium size melanoma and to the exclusion of patients with subfoveal tumors. At 1 year from treatment, only a few patients with posterior tumor localization and direct effect of radiation on macula and the optic disc had experienced visual acuity loss. Most patients experienced a visual acuity loss within the third year after treatment, when the peak of maculopathy was reported.

Damato et al. proposed that loss of visual acuity is a delicate relationship of a broad variety of factors, such as age, pre-treatment visual acuity, basal diameter and tumor location (18).

While the exact mechanisms causing an impairment of visual acuity are not fully understood, the assumption here is that there are multiple reasons. From our multivariate analysis, factors correlating with a worse post-treatment visual acuity were age at start of treatment, longitudinal basal diameter and distance of the posterior margin of the tumor from the foveola. Systemic factors (e.g. hypertension and diabetes) have been inconsistently reported as risk factors in predicting final visual acuity (13). Our data also revealed that the distance of the posterior margin of the tumor from the foveola was the clinical factor most strongly associated with visual acuity loss. Determining the overall risk of vision loss may help in patient selection, in choosing the treatment modality and management counseling. The evidence that preventing radiation maculopathy may offer better final visual acuity results makes works like this very useful. After ruthenium treatment, about 50% of patients did not need to undergo any procedure to preserve visual acuity; the goal is to identify the other 50% of patients for whom such preventive therapies can be highly successful for visual acuity outcome.

The strength of this study’s data was that we reviewed the patients ourselves at each follow-up. This allowed continued and uniform follow-up patterns on all of the patients and a rigorous standardization of visual acuity measured from the same ophthalmologists at every follow-up control. The main limitation of this study is represented by the fact that our nomogram has not been externally validated using an independent dataset originating from other institutions. Therefore, an external validation of the proposed model using a large database would be of great interest in order to confirm our observations on a more heterogeneous population through a reliable generalization process (23-25).

Conclusion

We identified the risk factors affecting visual outcome and developed a predictive model and decision support tool (AVATAR nomogram). This study is an extension of our preliminary work.

Conflicts of Ιnterest

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

Monica Maria Pagliara: Conception of the work; Luca Tagliaferri: Conception of the work; Jacopo Lenkowicz: Analysis of data for the work; Luigi Azario: Interpretation of data for the work; Dario Giattini: Acquisition of data for the work; Bruno Fionda: Acquisition of data for the work; Maria Grazia Sammarco: Drafting the work; Valentina Lancellotta: Drafting the work; Maria Antonietta Gambacorta: Final approval of the version to be published; Maria Antonietta Blasi: Final approval of the version to be published.

References

- 1.Gambacorta MA, Valentini V, Coco C, Manno A, Doglietto GB, Ratto C, Cosimelli M, Miccichè F, Maurizi F, Tagliaferri L, Mantini G, Balducci M, La Torre G, Barbaro B, Picciocchi A. Sphincter preservation in four consecutive phase II studies of preoperative chemoradiation: analysis of 247 T3 rectal cancer patients. Tumori. 2007;93(2):160–169. doi: 10.1177/030089160709300209. PMID: 17557563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bussu F, Tagliaferri L, Mattiucci G, Parrilla C, Dinapoli N, Miccichè F, Artuso A, Galli J, Almadori G, Valentini V, Paludetti G. Comparison of interstitial brachytherapy and surgery as primary treatments for nasal vestibule carcinomas. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(2):367–371. doi: 10.1002/lary.25498. PMID: 26372494. DOI: 10.1002/lary.25498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tagliaferri L, Manfrida S, Barbaro B, Colangione MM, Masiello V, Mattiucci GC, Placidi E, Autorino R, Gambacorta MA, Chiesa S, Mantini G, Kovács G, Valentini V. MITHRA - multiparametric MR/CT image adapted brachytherapy (MR/CT-IABT) in anal canal cancer: A feasibility study. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2015;7(5):336–345. doi: 10.5114/jcb.2015.55118. PMID: 26622238. DOI: 10.5114/jcb.2015.55118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frakulli R, Galuppi A, Cammelli S, Macchia G, Cima S, Gambacorta MA, Cafaro I, Tagliaferri L, Perrucci E, Buwenge M, Frezza G, Valentini V, Morganti AG. Brachytherapy in non melanoma skin cancer of eyelid: A systematic review. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2015;7(6):497–502. doi: 10.5114/jcb.2015.56465. PMID: 26816508. DOI: 10.5114/jcb.2015.56465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tagliaferri L, Pagliara MM, Fionda B, Scupola A, Azario L, Sammarco MG, Autorino R, Lancellotta V, Cammelli S, Caputo CG, Martinez-Monge R, Kovács G, Gambacorta MA, Valentini V, Blasi MA. Personalized re-treatment strategy for uveal melanoma local recurrences after interventional radiotherapy (brachytherapy): Single institution experience and systematic literature review. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2019;11(1):54–60. doi: 10.5114/jcb.2019.82888. PMID: 30911311. DOI: 10.5114/jcb.2019.82888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jampol LM, Moy CS, Murray TG, Reynolds SM, Albert DM, Schachat AP, Diddie KR, Engstrom RE Jr, Finger PT, Hovland KR, Joffe L, Olsen KR, Wells CG, Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group (COMS Group) The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma: IV. Local treatment failure and enucleation in the first 5 years after brachytherapy. COMS report no. 19. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(12):2197–2206. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01277-0. PMID: 12466159. DOI: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finger PT, Kurli M. Laser photocoagulation for radiation retinopathy after ophthalmic plaque radiation therapy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(6):730–738. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.052159. PMID: 15923510. DOI: 10.1136/bjo.2004.052159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah SU, Shields CL, Bianciotto CG, Iturralde J, Al-Dahmash SA, Say EAT, Badal J, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Intravitreal bevacizumab at 4-month intervals for prevention of macular edema after plaque radiotherapy of uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.08.039. PMID: 24139123. DOI: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reichstein D. Current treatments and preventive strategies for radiation retinopathy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(3):157–166. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000141. PMID: 25730680. DOI: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown SA. Building SuperModels: emerging patient avatars for use in precision and systems medicine. Front Physiol. 2015;6:318. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00318. PMID: 26594179. DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown SA. Principles for developing patient avatars in precision and systems medicine. Front Genet. 2016;6:365. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00365. PMID: 26779255. DOI: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pagliara MM, Tagliaferri L, Azario L, Lenkowicz J, Lanza A, Autorino R, Caputo CG, Gambacorta MA, Valentini V, Blasi MA. Ruthenium brachytherapy for uveal melanomas: Factors affecting the development of radiation complications. Brachytherapy. 2018;17(2):432–438. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2017.11.004. PMID: 29275868. DOI: 10.1016/j.brachy.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tagliaferri L, Pagliara MM, Masciocchi C, Scupola A, Azario L, Grimaldi G, Autorino R, Gambacorta MA, Laricchiuta A, Boldrini L, Valentini V, Blasi MA. Nomogram for predicting radiation maculopathy in patients treated with ruthenium-106 plaque brachytherapy for uveal melanoma. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2017;9(6):540–547. doi: 10.5114/jcb.2017.71795. PMID: 29441098. DOI: 10.5114/jcb.2017.71795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovács G, Tagliaferri L, Valentini V. Is an Interventional Oncology Center an advantage in the service of cancer patients or in the education? The Gemelli Hospital and INTERACTS experience. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2017;9(6):497–498. doi: 10.5114/jcb.2017.72603. PMID: 29441092. DOI: 10.5114/jcb.2017.72603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. DP:AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York. Springer. 2017;8th ed doi: 10.3322/caac.21388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tagliaferri L, Pagliara MM, Boldrini L, Caputo CG, Azario L, Campitelli M, Gambacorta MA, Smaniotto D, Frascino V, Deodato F, Morganti AG, Kovács G, Valentini V, Blasi MA. INTERACTS (INTErventional Radiotherapy ACtive Teaching School) guidelines for quality assurance in choroidal melanoma interventional radiotherapy (brachytherapy) procedures. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2017;9(3):287–295. doi: 10.5114/jcb.2017.68761. PMID: 28725254. DOI: 10.5114/jcb.2017.68761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Multimodel inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol Meth Res. 2004;33(2):261–304. DOI: 10.1177/0049124104268644. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Damato B, Patel I, Campbell IR, Mayles HM, Errington RD. Visual acuity after ruthenium(106) brachytherapy of choroidal melanomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(2):392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.02.059. PMID: 15990248. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Summanen P, Immonen I, Kivelä T, Tommila P, Heikkonen J, Tarkkanen A. Visual outcome of eyes with malignant melanoma of the uvea after ruthenium plaque radiotherapy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1995;26(5):449–460. PMID: 8963860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melia BM, Abramson DH, Albert DM, Boldt HC, Earle JD, Hanson WF, Montague P, Moy CS, Schachat AP, Simpson ER, Straatsma BR, Vine AK, Weingeist TA, Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Collaborative ocular melanoma study (COMS) randomized trial of I-125 brachytherapy for medium choroidal melanoma. I. Visual acuity after 3 years COMS report no. 16. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(2):348–366. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00526-1. PMID: 11158813. DOI: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00526-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cruess AF, Augsburger JJ, Shields JA, Donoso LA, Amsel J. Visual results following cobalt plaque radiotherapy for posterior uveal melanomas. Ophthalmology. 1984;91(2):131–136. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34317-2. PMID: 6709327. DOI: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34317-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quivey JM, Char DH, Phillips TL, Weaver KA, Castro JR, Kroll SM. High intensity 125-iodine (125I) plaque treatment of uveal melanoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;26(4):613–618. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90277-3. PMID: 8330990. DOI: 10.1016/0360-3016(93)90277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tagliaferri L, Gobitti C, Colloca GF, Boldrini L, Farina E, Furlan C, Paiar F, Vianello F, Basso M, Cerizza L, Monari F, Simontacchi G, Gambacorta MA, Lenkowicz J, Dinapoli N, Lanzotti V, Mazzarotto R, Russi E, Mangoni M. A new standardized data collection system for interdisciplinary thyroid cancer management: Thyroid COBRA. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;53:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.02.012. PMID: 29477755. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tagliaferri L, Budrukkar A, Lenkowicz J, Cambeiro M, Bussu F, Guinot JL, Hildebrandt G, Johansson B, Meyer JE, Niehoff P, Rovirosa A, Takácsi-Nagy Z, Boldrini L, Dinapoli N, Lanzotti V, Damiani A, Gatta R, Fionda B, Lancellotta V, Soror T, Monge RM, Valentini V, Kovács G. ENT COBRA ONTOLOGY: the covariates classification system proposed by the Head & Neck and Skin GEC-ESTRO Working Group for interdisciplinary standardized data collection in head and neck patient cohorts treated with interventional radiotherapy (brachytherapy) J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2018;10(3):260–266. doi: 10.5114/jcb.2018.76982. PMID: 30038647. DOI: 10.5114/jcb.2018.76982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meldolesi E, Van Soest J, Alitto AR, Autorino R, Dinapoli N, Dekker A, Gambacorta MA, Gatta R, Tagliaferri L, Damiani A, Valentini V. VATE: VAlidation of high TEchnology based on large database analysis by learning machine. Colorectal Cancer. 3(5):435–450. DOI: 10.2217/CRC.14.34. [Google Scholar]