A 40-year-old woman developed erythematous, raised and pruritic, migratory lesions on a daily basis affecting her whole body for the past 3 months; the appearance of the rash was consistent with urticaria. There was associated angioedema affecting her lips and face. Her medical history was significant for MS, diagnosed 9 years before, manifesting clinically with mobility, speech, and cognitive impairment. Initial treatment was with β-interferon and glatiramer acetate; however, disease relapse prompted switching to alemtuzumab, with 2 standard courses given 12 months apart (60 and 36 mg, respectively, the last dose given 12 months before the onset of rash), and achieved remission with a new baseline Expanded Disability Status Scale of 2.

Ancillary history includes short-lived, asymptomatic, subclinical hypothyroidism before 13 years for which she was given thyroxine during pregnancy. Months after her first dose of alemtuzumab, she developed mild symptomatic hyperthyroidism with persistent thyroglobulin antibodies. Carbimazole was given for a year but ceased after her thyroid function tests normalized. She remained persistently thyroglobulin antibody seropositive. No other subsequent secondary autoimmune diseases manifested with otherwise normal laboratory results.

At the time of development of urticaria, she was on long-term venlafaxine and dexamphetamine for a mood disorder. There was no history to suggest an allergic reaction to current medications. Differential blood count, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate did not suggest any chronic or recurrent infections triggering urticaria. Specific IgE to dust mite, grass pollen mix, and staple food was negative.

A clinical diagnosis of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) was made, and she was treated with a maximal dose of histamine (H1/H2) receptor blockade (cetirizine 20 mg bis die and ranitidine 150 mg bis die). Despite this treatment, she continued to have breakthrough urticaria and required intermittent high dose prednisolone (1 mg/kg/d) while still scoring 42 on the Urticaria Activity Score over 7 Days scale. Therapy was intensified with omalizumab (300 mg monthly), because of its demonstrated efficacy in CSU1 and low side-effect profile as compared to other agents used in treatment of alemtuzumab-related secondary autoimmunity. This resulted in a dramatic (but incomplete) reduction in urticaria, with burdensome breakthrough lesions typically in the week before her next omalizumab dose.

No clinical relapses or new signs of radiologic MS activity occurred over this period; her MS continued to improve throughout omalizumab therapy with the Expanded Disability Status Scale score improving from 2 to 0, over 18 months of monitoring.

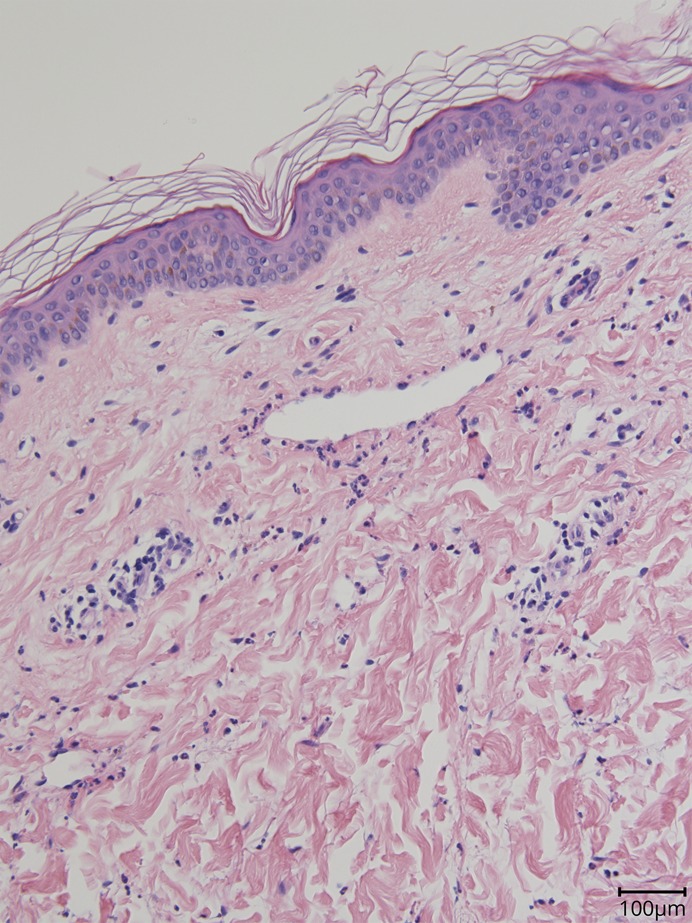

A skin biopsy was performed that excluded other causes of immune-mediated urticaria, securing the diagnosis of CSU2 (see figure 1 and figure e-1, links.lww.com/NXI/A186). Montelukast was initiated at 10 mg/d and advised to adhere to a strict 28-day dosing of omalizumab to minimize the breakthrough period.

Figure. A perilesional skin biopsy showed mild, superficial, dermal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and mild dermal oedema with dilated lymphatics.

Neutrophils were seen within the lumen of the vessels and scattered in small numbers through interstitium together with occasional mast cells. The findings were consistent with chronic urticaria. No evidence of vasculitis was seen.

Discussion

Alemtuzumab is a monoclonal antibody directed against the CD52 antigen. It is used therapeutically in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and increasingly in MS. The CD52 antigen is expressed on >95% of peripheral B and T lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages, and thymocytes. Binding of alemtuzumab to the CD52 antigen causes lysis of the target cell, and its clinical efficacy is because of B and T lymphocyte, monocyte, and natural killer cell depletion.3

Immune dysregulation after alemtuzumab has been reported at rates up to 30%, with common manifestations being thyroid diseases and autoimmune hematologic conditions.3 Autoimmune side effects manifested at 6 months with a peak incidence in year 3 after the first course.4 It is postulated the autoimmune sequelae arise from reconstitution of cells after T-cell lymphopenia along with additional insults including the depletion of Tregs and overproduction of interleukin-21.5 T cells undergo homeostatic proliferation to reconstitute the immune system relying on stimulation through the T-cell receptor-self peptide-major histocompatibility complex and leads to generation of self-reactive T cells.5

CSU is the appearance of wheals and/or angioedema for longer than 6 weeks.1 It can be because of autoantibodies or idiopathy.2 The treatment paradigm is high-dose H1-antagonists (up to 4 times the usual recommended dose), H-2 antagonists, and adjuvants such as leukotriene antagonists. If symptoms remain refractory, the most effective next-line agent is omalizumab. Omalizumab is a humanized immunoglobulin G directed against immunoglobulin E and is thought to not only bind serum IgE but also downregulate its cognate receptor (Fc ƐR-1) on mast cells; it has demonstrated efficacy in severe, autoimmune CSU.6

We believe that this is the first reported case of CSU in the context of immune dysregulation within the typical time period after alemtuzumab and thus adds to the expanding repertoire of alemtuzumab-related immune-mediated side effects. Previous reports of urticaria were solely acute infusion-related side effects.7 It is important to consider CSU as a cause of recurrent rashes and angioedema after alemtuzumab because disease specific therapy is effective and available.

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

Disclosures available: Neurology.org/NN.

References

- 1.Maurer M, Rosen K, Hsieh HJ, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of chronic idiopathic or spontaneous urticaria. N Engl J Med 2013;368:924–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saini SS. Chronic spontaneous urticaria. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2014;34:33–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guarnera C, Bramanti P, Mazzon E. Alemtuzumab: a review of efficacy and risks in the treatment of relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2017;13:871–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decallonne B, Bartholomé E, Delvaux V, et al. Thyroid disorders in alemtuzumab-treated multiple sclerosis patients: a Belgian consensus on diagnosis and management. Acta Neurol Belg 2018;118:153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones JL, Phuah CL, Cox AL, et al. IL-21 drives secondary autoimmunity in patients with multiple sclerosis, following therapeutic lymphocyte depletion with alemtuzumab (Campath-1H). J Clin Invest 2009;119:2052–2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplan AP. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: pathogenesis and treatment considerations. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2017;9:477–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uppenkamp M, Engert A, Diehl V, Bunjes D, Huhn D, Brittinger G. Monoclonal antibody therapy with CAMPATH-1H in patients with relapsed high- and low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: a multicenter phase I/II study. Ann Hematol 2002;81:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]