Abstract

This study evaluated a shared decision-making (SDM) Toolkit (decision aid, counseling guide, and provider scripts) designed to prepare and engage racially diverse women in shared decision-making discussions about the mode of birth after cesarean. The pilot study, involving 27 pregnant women and 63 prenatal providers, assessed women's knowledge, preferences, and satisfaction with decision making, as well as provider perspectives on the Toolkit's acceptability. Most women experienced knowledge improvement, felt more in control and that providers listened to their concerns and supported them. Providers reported that the Toolkit helped women understand their options and supported their counseling. The SDM Toolkit could be used to help women and providers improve their SDM regarding mode of birth after cesarean.

Keywords: cesarean, VBAC, scripted counseling, shared decision making, decision aid

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare providers have significant influence on women's decision making regarding mode of birth after cesarean (Bernstein, Matalon-Grazi, & Rosenn, 2012; Eden, Hashima, Osterweil, Nygren, & Guise, 2004; Emmett, Shaw, Montgomery, Murphy, & DiAMOND Study Group, 2006; Metz et al., 2013). However, due to the limited time available during prenatal visits, ensuring a consistent yet personalized approach to discussions about planned mode of birth can be challenging.

Decision support tools are needed to assist both women and providers in shared decisionmaking (SDM) to achieve birth plans that reflect individual needs, values, and preferences. Decision aids have been evaluated and found to be effective in preparing women for decisionmaking by increasing their knowledge about birth options, helping them weigh risks and benefits, and clarifying their personal values and preferences (Dugas et al., 2012; Shorten, Shorten, Keogh, West, & Morris, 2005). Despite their effectiveness, decision aids provide only part of the support needed for SDM to occur. Providers also need the right tools to guide and tailor their counseling during time-limited appointments (Joseph-Williams et al., 2017). Furthermore, strategies are necessary to implement the right combination of patient and provider tools in busy, “real life” practice settings with the goal of supporting both sides of the SDM conversation.

The aim of this pilot study was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of using a combination of tools—a SDM Toolkit— designed to assist women and providers during the continuum of prenatal care, as they share decisions about mode of birth after cesarean. We hypothesized that the SDM Toolkit (comprised of decision aid, counseling guide, and provider scripts) would provide women and their providers with the right combination of support necessary for enabling them to make the best individualized decisions about their birth options within a SDM framework.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In 2017, the United States cesarean rate was 32%, more than double the rate recommended by the World Health Organization to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality (Betran et al., 2016; Hamilton, Osterman, Driscoll, & Rossen, 2018). Since the release of the National Institute of Health's 2010 Consensus Development Conference on Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC) statement which emphasized the importance of VBAC as an option for women, rates of successful labor after cesarean (LAC) increased from 8.4% in 2009 to 11.9% in 2015 (Cunningham et al., 2011; National Partnership for Women and Families, 2017). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that most women with one or two previous low transverse cesareans are considered candidates for LAC and should be supported through SDM about their birth options. Additionally, they call for more robust SDM counseling by health care providers (ACOG, 2017).

Strategies to support SDM are particularly important in the context of the racial and ethnic birth disparities present in the United States. Improving patient and provider discussions has the potential to improve mode of birth after cesarean decision-making experiences and outcomes, particularly in women from marginalized groups, including those from ethnic minorities (Durand et al., 2014; Shorten et al., 2019). Evidence from a recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that SDM interventions can improve outcomes for patients from disadvantaged groups in particular. Furthermore, it stated that if adapted to meet the needs of specific patient groups, it could have the potential to reduce inequalities in outcomes (Durand et al., 2014).

Women from ethnic minorities giving birth in the United States have some of the highest rates of cesarean birth and lowest rates of VBAC (Cunningham et al., 2011; Hamilton et al., 2018). According to the Center for Disease Control, the cesarean rate for non-Hispanic Black women in 2017 was 36.0%, the highest rate of any ethnic group assessed (Hamilton et al., 2018). In 2016, specifically within Massachusetts, non-Hispanic Black women had a 34.6% cesarean rate compared to the overall rate of 31.3% (Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2018). Additionally, non-Hispanic Black women had the lowest VBAC rates at 17.1% (compared to 17.5 for non-Hispanic White women, 18.1% for Hispanic women, 19.6% for Asian/Pacific Islanders; Edmonds, Hawkins, & Cohen, 2016). Decision support tools designed to reach women across diverse backgrounds and better support their mode of birth discussions with providers are therefore much needed as we work to not only address disparities in decision-making experiences but also birth outcomes (Durand et al., 2014; Shorten et al., 2019).

The process of SDM between women and providers is important for mode of birth after cesarean discussions because the risks and benefits are complex and weighed differently for mothers and their babies (Shorten, Shorten, & Kennedy, 2014). Additionally, birth outcomes are uncertain, and choices are personal and value-laden (Munro et al., 2017; Shorten et al., 2019; Shorten et al., 2014). The SDM framework provides an opportunity for women to examine personal information, preferences, values, and beliefs about their birth choice with providers and make plans based on bi-directional discussions (Charles, Gafni, & Whelan, 1999; Elwyn, Edwards, & Kinnersley, 1999; Légaré & Thompson-Leduc, 2014; Shorten et al., 2019). Ideally, SDM is an informed, interactive, supportive, and individualized method of decision counseling that draws on each woman's experience of birth, as she works with her provider to establish her preferred mode of birth (Charles et al., 1999; Cox, 2014; Shorten et al., 2005).

Practical solutions for achieving SDM in pregnancy care are long overdue, particularly in busy clinical settings serving diverse groups of women. Numerous studies have demonstrated the benefits of decision aids in the context of SDM, yet integration within routine prenatal care remains challenging (Barry & Edgman-Levitan, 2012; Joseph-Williams et al., 2017; Stacey et al., 2017). A systematic review of studies implementing a variety of decision support tools into routine clinical practice concluded that despite well-established benefits of decision support interventions, the recipe for implementation remains unclear (Elwyn et al., 2013). Rather than using stand-alone decision support tools, a combination of interventions designed to support patients and providers, embedded within the service context of care, may be more likely to succeed in practice (Joseph-Williams et al., 2017). Research focused on the acceptability of implementing a combination of decision support tools for women and providers is an important next step for practice improvement.

METHODS

Design

This pilot study was designed to engage women and their providers and examine the experiences of both sides of the SDM process for mode of birth after cesarean. The SDM Toolkit was evaluated for acceptability in clinical practice by ethnically and racially diverse pregnant women and their providers. Women's knowledge about the risks and benefits of different birth options were assessed before and after the use of the SDM Toolkit, using a pre- and post-knowledge test. Areas of interest included identifying women's sources of information about giving birth after cesarean, and who helped women with their decision making. Additionally, differences between intended or planned mode of birth, actual mode of birth attempted (LAC or elective repeat cesarean birth [ERCB]) and birth outcomes (vaginal or cesarean) were compared and analyzed. Provider perspectives on acceptability and satisfaction with the SDM Toolkit were also evaluated. Details of the development of the decision aid and provider tools contained in the SDM Toolkit are fully described elsewhere (Chinkam, Ewan, Koeniger-Donohue, Hawkins, & Shorten, 2016).

Sample and Setting

Women receiving care at the study site over a seven-month period (June–December 2016; individually or in the CenteringPregnancy model) were eligible to participate if they had experienced no more than two previous low-transverse cesarean sections, were currently pregnant with a singleton pregnancy and able to speak and read English. Women were excluded if they had contraindications for vaginal birth based on the ACOG guidelines (2017). Approval for this research was granted by the Institutional Review Board from Boston University Medical Campus and Boston Medical Center. To ensure the protection of study participants, all patients and providers received and signed informed consent forms that included a description of the study, requirements for participation, and potential benefits and risks of participation. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured through a process of coding.

Boston Medical Center is an academic, tertiary-care medical center and the safety net hospital for the city of Boston. The patient population served is racially and ethnically diverse with 40% identifying as non-Hispanic Black, 35% Hispanic, 10% non-Hispanic White, 5% Asian, and 10% mixed/other. Eighty-five percent of the 2,800 annual births are publicly insured. Pregnant women receive either group (CenteringPregnancy) or individual prenatal care. At least one-half of women are seen by certified nurse-midwives (CNMs) and nurse practitioners. On the labor and delivery unit, CNMs practice in a collaborative model with obstetrician-gynecologists and family medicine physicians. Based on 2016 Boston Medical Center birth data, 82% of women with a previous cesarean birth were candidates for LAC. Of those women, 40% chose LAC and 23% had VBACs (a success rate of 57%).

TOOLS, PROCEDURES, AND MEASURES

The SDM Toolkit

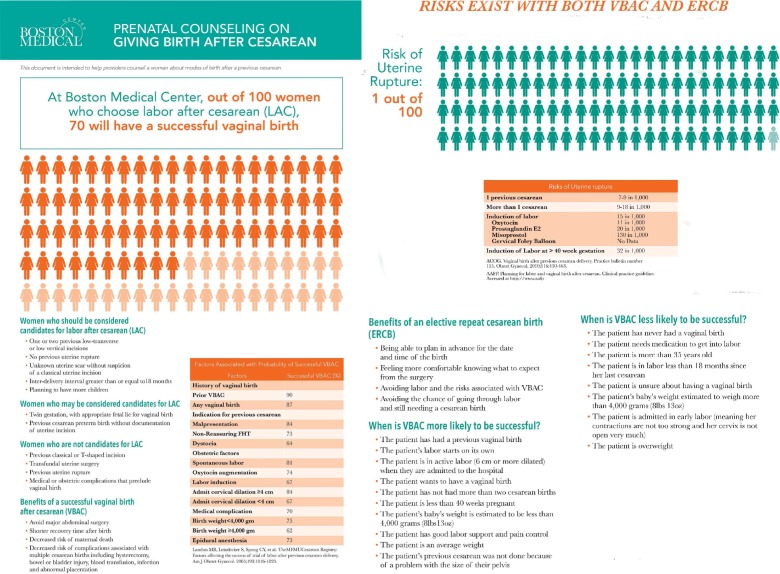

The “Giving Birth after Cesarean” decision aid introduced women to their different mode of birth options and encouraged them to think about their birth priorities and preferences. The eight-page color decision aid was written at a sixth and seventh grade reading level. It was designed to be used as a reference for women and their families to review at home after discussions with their providers. Key content included LAC candidacy, risks and benefits of LAC and ERCB, preparation for birth choices, tips to increase chances of successful vaginal birth, and tips for having a safe cesarean birth. Two pictograms were included to illustrate an overall chance of having a successful VBAC among women who are candidates and to show the absolute risk of uterine rupture for women undergoing a LAC. Pictographs were chosen to complement the text and provide visual representation of key points from the decision aid.

The provider counseling sheet was a double-sided, laminated counseling tool to guide and enrich face-to-face clinic discussions and offer women and providers a mechanism to facilitate SDM discussions (Figure 1). The counseling sheet contained large print, color text, and pictographs presented in an easy to understand form. Content was consistent with the “Giving Birth after Cesarean” decision aid, in order to reinforce that information.

Figure 1.

Double-sided laminated provider counseling tool.

Provider counseling scripts were developed to be used at the second prenatal appointment and 32- to 36-week visit (see Appendices A and B, respectively). The two scripts were based on the Informed Medical Decision Foundation's “Six Steps for Shared Decision Making” which include: inviting women to participate in their decision-making, presenting options, providing information on benefits and risk, assisting in evaluating options based on the woman's goals and concerns, facilitating the decision, and assisting with its implementation (Wexler, 2012). The scripts included examples of questions, with pauses for reflection and response, in order to help enhance providers' SDM during counseling. When using the scripts, providers marked each question/statement that they completed during the visit with an “X.” Incomplete scripts were completed at subsequent prenatal visits.

A provider education video about SDM was made by the researchers and distributed to all providers before the start of the study. The video was designed as an orientation to the SDM Toolkit and to help establish a consistent level of knowledge about SDM among all providers before the SDM Toolkit was implemented. The video reviewed current, evidence-based literature describing and supporting the use of SDM.

Study Procedure

Prenatal schedules were checked weekly to identify eligible women with an upcoming first prenatal visit. Those women were mailed a letter about the study and then called and invited to participate. Women who voiced interest on the phone about participating in the study were approached in person while in the waiting room ahead of their first prenatal visit. The study was explained again to them, and if they agreed to participate, they were given the consent form to read and sign. After giving informed consent, each woman completed a pre-test questionnaire (written at a sixth to seventh grade reading level) and received a “Giving Birth after Cesarean” decision aid. The post-test was completed at the appointment after the 32- to 36-week visit. Each participant was given a gift card after finishing the post-test questionnaire to thank her for her time.

Every provider whose patient agreed to participate in the study received a folder containing a copy of the appropriate script and the counseling sheet prior to the intervention visits (second visit and 32–36 week visit) to ensure usage of the tools. Researchers e-mailed providers before each intervention visit to remind them that their patient was involved in the study and to complete the script. They also received an e-mail after the visit which served to thank the provider for using the script and to follow up on whether there were incomplete elements of the script that needed to be finished at a subsequent visit. By virtue of the study sites' focus on prenatal continuity of care, the majority of providers who counseled their patients at the second visit also counseled them at their 32- to 36-week visits.

After completion of the patient side of the intervention (i.e., when all enrolled women had received the 32–36 week counseling) all prenatal providers at the study site (CNMs, nurse practitioners, obstetrician-gynecologists, and family medicine physicians) were surveyed using a three-part questionnaire. Providers were asked to participate in the survey regardless of whether they had been involved in the study or used the SDM Toolkit. Participation was sought from all prenatal providers to ensure that the widest possible range of perspectives on SDM and the use, or possible use, of a toolkit were obtained.

Part One of the provider questionnaire requested demographic data (age, type of provider, years in practice) and counseling data from providers who had used the tools (frequency and duration of use). Part Two was for providers who had used the study tools and consisted of 10 questions on a five-point Likert scale on topics concerning SDM, their opinions on the SDM Toolkit, and counseling documentation. Part Three was for providers who had never used the SDM Toolkit and asked similar questions as in Part Two but focused on provider's thoughts about the benefit of using a Toolkit in the future. The surveys were e-mailed to all prenatal providers and were administered using the secure web-based application, Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; Harris et al., 2009). All questions were tested for face validity after review by researchers and found to be acceptable.

Pre- and post-survey responses were analyzed using 2013 NCSS9 statistical software. The Fishers exact test statistic was used for assessment of statistical significance, which was set at p < .05.

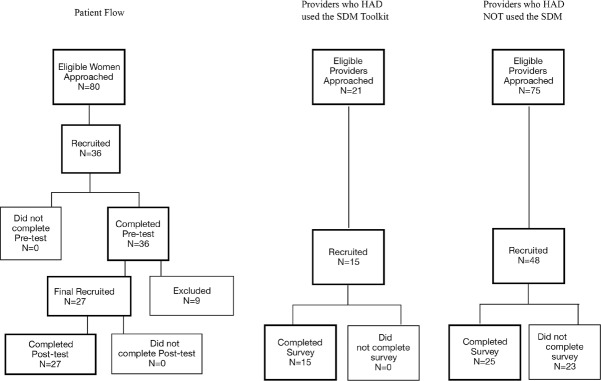

RESULTS

Eighty women were approached for study participation, 36 women enrolled and 27 (75%) completed both the pre- and post-test surveys. Sixty-three providers responded to the REDCap survey, though only 40 completed the survey (100% SDM Toolkit users and 52% of non-SDM Toolkit users). Figure 2 presents the flow of participants, both women and providers, through the study (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow participants.

Reasons for women completing the pre-test and not the post-test included: miscarriage (n = 2), discontinued care at Boston Medical Center (n = 3), ineligibility identified after enrollment (n = 3), and preterm cesarean birth (n = 1). Results are presented for the 27 women who completed both pre-and post-test results. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of those women. Noteworthy in the table is the fact that 88.9% of the women were non-White and 66.7% were born outside of the United States.

TABLE 1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants (n = 27).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <25 | 2 (7.4) |

| 26-35 | 19 (70.4) |

| >35 | 6 (22.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 10 (37.0) |

| Single | 17 (63.0) |

| Employment | |

| Employed | 11 (40.7) |

| Not employed | 16 (59.3) |

| Health insurance | |

| Medicaid | 18 (66.7) |

| Private insurance | 8 (29.6) |

| Self-pay | 1 (3.7) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Asian | 1 (3.7) |

| Blacka | 21 (77.8) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2 (7.4) |

| White | 3 (11.1) |

| Place of birth | |

| United States | 9 (33.3) |

| Outside United States | 18 (66.7) |

3 Nigerians, 2 Ethiopians, 5 Haitians, 3 Domicans, and 8 African-Americans.

Women's Knowledge About LAC and ERCB

Women demonstrated improvements in knowledge on topics related to LAC and ERCB for nine out of 12 knowledge test questions (Table 2). Due to small sample size, these improvements were not statistically significant, except for the question asking if “Vaginal birth after cesarean is safer for most women,” which recorded a significant increase in correct responses post-test (p < .05).

TABLE 2. Change in Knowledge After Intervention (n = 27).

| Risks and Benefits of LAC | Pre-Test Correct Answer n (%) | Post-Test Correct Answer n (%) | Fisher's Exact Test p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal birth after cesarean is safer for most women. | 12 (44.4) | 20 (74.1) | .051 |

| Recovering after a vaginal birth is quicker and easier. | 23 (85.2) | 26 (96.3) | .351 |

| Vaginal birth is the best option if you plan to have more children. | 21 (77.8) | 25 (92.6) | .250 |

| Having a VBAC increases the risk of uterine rupture (that your scar might tear open). | 10 (37.0) | 14 (51.9) | .412 |

| It is dangerous for you and your baby if the scar opens. | 19 (70.4) | 23 (85.2) | .327 |

| One in four women who try vaginal birth end up having a repeat cesarean. | 16 (59.3) | 11 (40.7) | .276 |

| Risks and Benefits of ERCB | Pre-Test Correct Answer % (n) | Post-Test Correct Answer % (n) | Change in Correct Answer (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A cesarean can prevent the baby from having a brain injury. | 10 (37.0) | 8 (29.6) | 0.773 |

| Recovery after a repeat cesarean takes the same amount as that after a vaginal birth. | 15 (55.6) | 20 (74.1) | 0.254 |

| You can avoid having urine leaking problem postpartum by choosing a repeat cesarean. | 11 (40.7) | 10 (37.0) | 1.000 |

| You are more likely after a repeat cesarean to go back to the hospital for problems compared to after a vaginal birth. | 14 (51.9) | 19 (70.4) | 0.264 |

| It is difficult to breastfeed after a cesarean. | 9 (33.3) | 13 (48.1) | 0.406 |

| Having many cesareans could prevent you from having more children. | 15 (55.6) | 19 (70.4) | 0.398 |

Notes. ERCB = elective repeat cesarean birth; LAC = labor after cesarean; VBAC = vaginal birth after cesarean.

Decisions About Mode of Birth After Cesarean

Before the interventions, 16 out of 27 (59%) women reported they had already thought about their intended mode of birth (44.4% VBAC; 14.8% ERCB) and 44.4% were sure/very sure about that decision (Table 3). After the intervention, 24 out of 27 (88.9%) women had decided on their mode of birth (59.3% VBAC; 29.6% ERCB; p < .05) and most (77.8%) were sure/very sure about their decision (p < .05). The proportion of women who reported they had enough information to make a decision more than doubled from 40.7% before the intervention to 92.6% afterward (p < .05).

TABLE 3. Decisions About Mode of Birth After Cesarean (n = 27).

| Questions | Pre-Test n (%) | Post-Test n (%) | Fisher's Exact Test p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| How do you plan to give birth to this baby? | .047 | ||

| Cesarean | 4 (14.8) | 8 (29.6) | |

| Vaginal | 12 (44.4) | 16 (59.3) | |

| Not sure | 11 (40.7) | 3 (11.1) | |

| How would you rate how sure you are about your birth decision? | .024 | ||

| Sure/Very sure | 12 (44.4) | 21 (77.8) | |

| Neutral, Unsure/Very unsure | 15 (55.6) | 6 (22.2) | |

| Do you have enough information to make a decision about the type of birth you have chosen? | .000 | ||

| Yes | 11(40.7) | 25 (92.6) | |

| Othera | 16 (59.3) | 2 (7.4) | |

| What sources have you used to help you decide how you want to give birth? | |||

| Talking with my health-care providers (doctor, midwife, nurse practitioner) | 12 (44.4) | 21 (77.8) | .024 |

| Information handout from health clinic | 2 (7.4) | 15 (55.6) | .000 |

| Family or friends | 8 (29.6) | 7 (25.9) | 1.000 |

| Internet | 5 (18.5) | 6 (22.2) | 1.000 |

| Books, journals, or magazines | 4 (14.8) | 6 (22.2) | .728 |

| Others | 2 (7.4) | 4 (14.8) | .669 |

| Who has helped you, or who will help you, make a decision? | |||

| Health-care providers | 22 (81.5) | 13 (48.1) | .021 |

| I have made or will make the decision myself | 8 (29.6) | 18 (66.7) | .014 |

| Husband, wife, or partner | 11 (40.7) | 12 (44.4) | 1.000 |

| Family and friends | 9 (33.3) | 6 (22.2) | .544 |

No or Not sure.

Sources of help in decision-making also changed. Seventy-seven percent of women indicated that talking with their provider had helped them decide how to give birth, an increase from only 44.4% before the intervention (p < .05). Women's perception of their own role in decision-making shifted after the intervention, with two-thirds (66.7%) reporting that they had made or would make the decision themselves, compared to 29.6% beforehand. Conversely, there was a decline in women's perception of health-care providers helping or making their birth decision, from 81.5% to 48.1%. Additionally, the “Giving Birth after Cesarean” decision aid helped 55.6% of women make their birth choices (p < .05).

Women's Perceptions of the SDM Toolkit

After the interventions, 96.1% of women believed that the decision aid information was important, easy to understand, and should be provided during prenatal care for all women (Table 4). Three quarters (76.9%) found the material to be new to them and 73.1% felt that it helped them make a decision on the type of birth. All women (100%) were satisfied with their provider's counseling, felt providers listened to their concerns, and gave them enough information about each mode of birth options. All women also felt they participated fully in their care, understood when given an explanation, and had enough time to make a decision on the mode of birth.

TABLE 4. Women Who Agreed or Strongly Agreed With Statements About Decision Aids and Provider Counseling Interventions (n = 26)a.

| Decision Aids | n (%) |

|---|---|

| It should be provided to all women during their prenatal visits | 25 (96.1) |

| It was important for me to get this information | 25 (96.1) |

| It was easy to understand | 25 (96.1) |

| This information was useful to me | 23 (88.5) |

| The information was not biased toward one particular type of birth | 23 (88.5) |

| I believe the information is accurate | 21 (80.8) |

| I learned new information | 20 (76.9) |

| The information helped me choose my type of birth | 19 (73.1) |

| Counseling by Prenatal Provider | n (%) |

|---|---|

| I participated fully in my care | 26 (100.0) |

| My provider listened to my concerns | 26 (100.0) |

| I understood when my provider explained things | 26 (100.0) |

| I had time to make birth choices | 26 (100.0) |

| I was given enough information about types of birth | 26 (100.0) |

| I was shown courtesy and respect | 25 (96.1) |

| I felt able to decide about type of birth | 25 (96.1) |

| I was not pressured to make a decision about my birth mode | 25 (96.1) |

| I felt in control | 25 (96.1) |

| I felt I could ask questions | 24 (92.3) |

One participant did not complete this section on the post-test

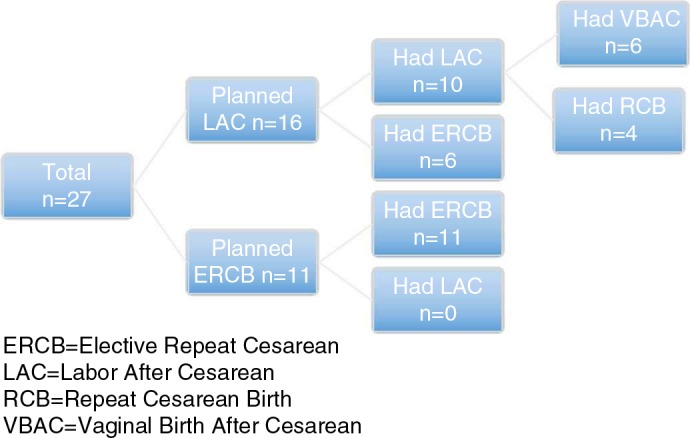

Planned and Actual Mode of Birth After Cesarean

Originally, 16 women planned to LAC, although only 10 attempted to do so. Of the 16 women who planned LAC, two women gave birth at outside hospitals by ERCBs, two women changed their minds after being induced with unfavorable cervixes and went forward with unscheduled repeat cesareans, and two women were counseled against LAC upon admission to the labor and delivery unit (one for Category Two fetal heart tracing and the other for gestational hypertension). Of the 10 women who attempted LAC, six experienced vaginal birth (successful VBAC rate was 60%; Figure 3). The overall LAC rate for all eligible study participants was 37.0% and the overall VBAC rate was 22.2%.

Figure 3.

Planned and actual mode of birth after cesarean.

Provider Perceptions of SDM Toolkit

All 15 SDM Toolkit users (100%), and only 25 of the 48 providers (52%) who did not use the SDM Toolkit completed the survey. Responses from a total of 40 completed surveys are presented in Table 5. Both groups of providers agreed that: SDM is important, counseling tools helped/would help them discuss mode of birth choices with their patients, they will continue to/would use the tools, and the decision aid is/or would be helpful. All of the providers (100%) who used the decision tools believed that they helped women understand the risks and benefits of each mode of birth, whereas 64% of providers who had not used the tools believed that women needed additional information to help them understand the risks and the benefits of each mode of birth. A higher percentage of providers who used the tools believed that women were more comfortable asking questions during counseling (p = .05).

TABLE 5. Providers Who Agreed or Strongly Agreed About Counseling Women by Toolkit Use (n = 15 Providers Used and 25 Providers Did Not Use the SDM Toolkit).

| Counseling Topic | Statement Rated by Providers (If one statement is listed it was rated by providers who did and did not use the Toolkit. If two statements are listed the first was rated by providers who used the tool and the second italicized statement was rated by providers who did not use the Toolkit) |

Providers Who Used SDM Toolkit n (%) |

Providers Who Did Not Use SDM Toolkit n (%) |

Fisher's Exact Test p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDM | SDM about the different modes of birth after cesarean is important to me | 15 (100.0) | 24 (96.0) | 1.000 |

| Provider counseling tool | The Provider Counseling Tool is helpful to me in counseling patients about mode of birth decisions Having a Provider Counseling Tool (a document to show patients when counseling them about mode of birth after cesarean options) would be helpful to me |

15 (100.0) | 23 (92.0) | .519 |

| Provider counseling scripts | The Provider Counseling Scripts are helpful to me in counseling patients about mode of birth decisions Having Provider Counseling Scripts (scripts to follow when counseling women about mode of birth after cesarean options) would be helpful to me |

12 (80.0) | 16 (64.0) | .477 |

| Time to use tool | I have enough time to use the tools for counseling during a prenatal visit I have enough time to counsel women about mode of birth after cesarean options during a prenatal visit |

9 (60.0) | 12 (48.0) | .527 |

| Interest in using SDM Toolkit | I will continue to use these tools when counseling patients I would be interested in using the Toolkit when counseling patients |

14 (93.3) | 23 (92.0) | 1.000 |

| Educational pamphlets for patients | I think that the “Giving Birth After Cesarean” pamphlet is helpful to patients I think that having educational information in the form of a pamphlet to teach patients more about their mode of birth after cesarean options would be helpful to patients |

14 (93.3) | 23 (92.0) | 1.000 |

| Patients' comforts asking questions | I think the patients are comfortable asking question(s) about the tools I think the patients are comfortable asking question(s) about their mode of birth choices after cesarean options and their mode of birth after cesarean options |

10 (66.7) | 8 (32.0) | .050 |

| Patient satisfied | I think my patients are satisfied with my counseling about their birth options | 8 (53.3) | 15 (60.0) | .749 |

| Patients understand risks | In my opinion, the tools help the patients understand the risks and benefits of each mode of birth types In my opinion, women need additional information from other sources to help them making an informed choice about their mode of birth options |

15 (100.0) | 16 (64.0) | .015 |

| Smart phrases in EPIC | Smart phrases should be created in EPIC (electronic medical records) to document SDM regarding mode of birth after cesarean | 15 (100.0) | 20 (80.0) | .137 |

Note. SDM = shared decision-making.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the acceptability and potential value of implementing a multi-faceted SDM Toolkit. Expanding upon previous research, we broadened the reach of the SDM Toolkit in order to inform, give voice, and gain perspectives of women from ethnically and racially diverse groups, the majority of whom were born outside the United States.

The study design allowed for examination of the perspectives of both women and their providers regarding the SDM Toolkit. Even though the decision aid counseling sheet helped women understand the risks and benefits of each mode of birth, feel comfortable asking questions, and participate fully in their care (Table 4), only half of providers who had used the SDM Toolkit with this same group of women believed that women were satisfied with their counseling (Table 5). Consistent with other studies that have assessed provider performance, women gave higher ratings of consultations during prenatal visits than providers (Campbell, Lockyer, Laidlaw, & MacLeod, 2007). Despite time constraints during prenatal visits, and the fact that only 60% of providers felt that they had enough time during visits to use the tools, from the women's perspective the decision aid, counseling sheet, and scripted counseling enhanced the quality of education delivered by their provider. Giving feedback to providers regarding how women view their birth counseling experience might be one strategy to encourage providers to use, or continue to use, the SDM Toolkit in practice.

Previous studies show that even though women seek information from a variety of sources, providers have a significant amount of influence over women's decision-making, and determine whether SDM is supported in reality (Declercq, Cheng, & Sakala, 2018; Eden et al., 2004; Emmett et al., 2006; Shorten et al., 2005). It was interesting that in this study, after the intervention, women seemed to perceive themselves as more active partners with providers in deciding their plan for birth after cesarean. This suggests that the SDM Toolkit augmented the principles of SDM, whereby women and their providers exchanged evidence-based information, and women felt more engaged in making the decision that was best for them. This is a particularly important finding given that most women were from minority groups who are vulnerable to disparities in opportunities for SDM (Durand et al., 2014). The SDM Toolkit appeared to play a role in their feeling of being empowered in their mode of birth after cesarean decisions.

Once women make the choice for mode of birth during pregnancy, ensuring high levels of adherence to their choice remains challenging, particularly if the choice is VBAC. In this study, even though there were 16 of 27 (59.2%) participants planning LAC, only six were successful in achieving VBAC (22.2%; Figure 3). This contrasts somewhat with earlier research at the same study site where the planned LAC rates were similar (64%), and the VBAC rate was higher (41%; Chinkam et al., 2016). One possible reason for this difference could be that the racial composition of the patient population in this study was quite different. In the current study, women were predominantly Black, and born outside the United States. Other studies involving Black women born within the United States found that even though they were more likely to plan LAC when compared with White women, White women were more likely to experience successful VBAC (Cunningham et al., 2011). In an Australian study, women who had experienced previous cesarean births, and were born outside Australia were more likely to choose ERCB when compared with Australian-born women (Shorten et al., 2005). International studies examining determinants of birth choices and outcomes after previous cesarean suggest that the socio-cultural context of pregnancy and associated models of prenatal care are influential and should be taken into account when designing, adapting, and integrating decision support strategies for women from diverse backgrounds (Chen, McKellar, & Pincombe, 2017; Torigoe & Shorten, 2018).

The implementation of the SDM Toolkit included all obstetric provider types, which may have also contributed to the lower overall VBAC rate in the study. The hypothesis that provider type could have influenced LAC and VBAC rates is supported by a retrospective chart review of women with a previous cesarean which reported that women cared for by CNMs were more likely to choose LAC, as well as achieve VBACs (Metz et al., 2013). Future research on decision support tools should explore levels of comfort in counseling women about mode of birth options across different provider types.

There were several limitations in addition to the small convenience sample for this pilot study. Both providers and women were self-selected volunteers, limited to English speaking women who were cared for by prenatal providers at only one of Boston Medical Center's many clinical sites. As a result, participants were not representative of the entire population of Boston Medical Center. There was also a theoretical potential for socially desirable responding which refers to the presentation of oneself in an overly favorable light on self-report questionnaires (Tracey, 2016). Since providing supportive counseling about the modes of birth after cesarean was promoted as a desirable behavior for providers who care for women with a previous cesarean within the study site, providers who used the tools may have responded in positive ways to align with known organizational expectations (see Table 5). Additionally, addressing individual and unexpected needs during the prenatal visit sometimes made it difficult for each woman and provider to fully use the SDM Toolkit to promote robust discussions and counseling. Despite the video sent to inform providers at the start of the study, variation in counseling delivery by the variety of providers could reduce the potential for generalizability of findings. Gender, race, proficiency, and compatibility of the provider-woman goals may have affected the degree of SDM. For future research using this dual perspective approach, adding a feasible tool to assess patient and provider perspectives about the quality of the communication at the end of a visit, could help clarify the results.

Implementation in Practice

Boston Medical Center has developed its first LAC/VBAC Guidelines that include the use of the counseling sheet and the “Giving Birth after Cesarean” decision aid that were developed and used in this study. We suggest that this type of approach could be adapted and applied in a wide variety of practices to aid in counseling women about their mode of birth decision-making. As this was a pilot study, results suggest that our SDM Toolkit could provide a potentially valuable foundation for developing resources to support SDM and should be further tested in other clinical sites.

CONCLUSION

The use of the SDM Toolkit was favorably accepted in an ethnically and racially diverse patient population and across different provider types. It helped women and providers work in partnership and empowered women from underserved groups to express their views regarding mode of birth options after cesarean. Future research is needed to further refine tools and strategies for effective implementation into a wider variety of clinical practice settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology at the Boston University School of Medicine's seed grant 2016.

The authors would like to thank all the OB providers and patients at Boston Medical Center for their support and active participation in this study. Additionally, the authors would like to thank Olivera Vragivic, Stephanie Threadwell, Bayla Ostrach, Kelsey Johnson, and Ashlee Espensen for their research application and recruitment support.

Biographies

SOMPHIT CHINKAM is a staff nurse-midwife at Boston Medical Center and a Clinical Assistant Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

COURTNEY STEER-MASSARO is a staff nurse-midwife at Boston Medical Center and an Assistant Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts.

KARLA DAMUS is a perinatal epidemiologist, the administrator of Clinical Trials.gov and clinical research education at the BU School of Medicine, and teaches in the BUSPH, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

BRETT SHORTEN is a freelance statistical consultant specializing in study design and statistical analysis, Vestavia, AL, USA.

ALLISON SHORTEN is a Professor in the Department of Family, Community and Health Systems, University of Alabama at Birmingham, School of Nursing and the Director of the Office of Interprofessional Curriculum, Center for Interprofessional Education and Simulation at UAB, Birmingham, AL, USA.

APPENDIX A

TABLE A.1.

| Provider Counseling Script 1* | |

|---|---|

| Congratulations thank you for choosing BMC You have a decision to make and I would like to make it with you. For most women (including you) VBAC is a safe option because… For very few women (including you), VBAC is not recommended because… What was your experience with your previous labor and birth? Knowing what is important to you will help us make a better decision. As you think about your option, what is important to you in planning the type of birth you want to have? Have you thought about how you want to give birth to this baby? | |

| yes | no |

| If C-section ask: Is there a particular reason why you don't want to try to have a vaginal birth? | It is OK if you are unsure. Please take your time to get more information, ask questions, discuss with loved ones, and make a decision that is good for you and the baby. I will support you as you decide on what kind of birth you plan to have. |

| If LAC ask: Is there a particular reason why you don't want to try to have a repeat C-section? | |

| Let's take a few minutes review the risks and benefits of both LAC and ERCB (use provider tool) | |

| Do you have any questions about any of this information? | |

| Is there any more information you need? | |

| Do you have a preference about which type of birth you want? | |

| We will keep working together to come up with the type of birth you prefer. | |

| Please take time to review the brochure, talk to someone who might help you make the decision, and we will talk more next time. | |

Adapted from “Six Steps for Shared Decision Making” published by the Informed Medical Decision Foundation.

APPENDIX B

TABLE B.1.

| Provider Counseling Script 2* | |

|---|---|

| Have you already decided about how you are going to give birth to this baby? | |

| yes | no |

| Let's talk about the things that concern you. | What is your plan? |

| What is the hardest part about deciding? | From what I heard you saying, this is what I understand… |

| Is there anything that I can do to help you make a decision? | Let's take a moment to talk about how you can prepare for each of type of birth. |

| We will continue to work together on your birth plan. | |

| If you choose to have C-section… | If you choose to have labor after C-section… |

| Will be scheduled at 39 weeks or higher | Have a good support person/plan for labor pain |

| Do not eat anything after midnight | Wait for spontaneous labor |

| Antibiotics at the time of C-section | Go to hospital in active labor |

| Your loved one will be with you | Really believe that you can have a vaginal birth |

| You will have a chance to have skin to skin | Have plan to deal with frustration with pushing |

| You will have 3–4 days hospital stay | If a C-section is suggested to you and it is not an emergency, ask questions |

| It is important that you get up and walk | |

| Is there anything else you want to discuss? | |

Adapted from “Six Steps for Shared Decision Making” published by the Informed Medical Decision Foundation.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no relevant financial interest or affiliations with any commercial interests related to the subjects discussed within this article.

FUNDING

The authors received the Obstetrics & Gynecology at Boston University School of Medicine's seed grant funding to support the research.

REFERENCES

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2017). ACOG practice bulletin no. 184: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 130(5), 1167–1169. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry, M. J., & Edgman-Levitan, S. (2012). Shared decision making—the pinnacle of patient-centered care. New England Journal of Medicine, 366(9), 780–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, S. N., Matalon-Grazi, S., & Rosenn, B. M. (2012). Trial of labor versus repeat cesarean: Are patients making an informed decision? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 207(3), e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.06.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betran, A. P., Torloni, M. R., Zhang, J. J., Gülmezoglu, A. M., WHO Working Group on Caesarean Section., Aleem, H. A., … Deneux-Tharaux, C. (2016). WHO statement on caesarean section rates. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 123(5), 667–670. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C., Lockyer, J., Laidlaw, T., & MacLeod, H. (2007). Assessment of a matched-pair instrument to examine doctor−patient communication skills in practicing doctors. Medical Education, 41(2), 123–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02657.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles, C., Gafni, A., & Whelan, T. (1999). Decision-making in the physician–patient encounter: Revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Social Science and Medicine, 49(5), 651–661. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00145-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. M., McKellar, L., & Pincombe, J. (2017). Influences on vaginal birth after caesarean section: A qualitative study of Taiwanese women. Women and Birth, 30(2), e132–e139. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinkam, S., Ewan, J., Koeniger-Donohue, R., Hawkins, J. W., & Shorten, A. (2016). The effect of evidence-based scripted midwifery counseling on women's choices about mode of birth after a previous cesarean. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health, 61(5), 613–620. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, K. J. (2014). Counseling women with a previous cesarean birth: Toward a shared decision-making partnership. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health, 59(3), 237–245. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, F. G., Bangdiwala, S. I., Brown, S. S., Dean, T. M., Frederiksen, M., Hogue, C. R., … Probstfield, J. L. (2011). National Institutes of Health consensus development conference statement: Vaginal birth after cesarean section new insights march 8–10, 2010. Obstetric Anesthesia Digest, 31(3), 140–142. doi: 10.1097/01.aoa.0000400279.71758.21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq, E. R., Cheng, E. R., & Sakala, C. (2018). Does maternity care decision-making conform to shared decision-making standards for repeat cesarean and labor induction after suspected macrosomia? Birth, 45(3), 236–244. doi: 10.1111/birt.12365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas, M., Shorten, A., Dube, E., Wassef, M., Bujold, E., & Chaillet, N. (2012). Decision aid tools for obstetric care: A meta-analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 74(12), 1968–1978. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand, M. A., Carpenter, L., Dolan, H., Bravo, P., Mann, M., Bunn, F., & Elwyn, G. (2014). Do interventions designed to support shared decision-making reduce health inequalities? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 9(4), e94670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden, K. B., Hashima, J. N., Osterweil, P., Nygren, P., & Guise, J. M. (2004). Childbirth preferences after cesarean birth: A review of the evidence. Birth, 31(1), 49–60. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.0274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds, J. K., Hawkins, S. S., & Cohen, B. B. (2016). Variation in vaginal birth after cesarean by maternal race and detailed ethnicity. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(6), 1114–1123. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1897-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn, G., Edwards, A., & Kinnersley, P. (1999). Shared decision-making in primary care: The neglected second half of the consultation. British Journal of General Practice, 49(443), 477–482. 20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn, G., Scholl, I., Tietbohl, C., Mann, M., Edwards, A. G., Clay, C., … Frosch, D. L. (2013). “Many miles to go…”: A systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 13(2), S14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmett, C. L., Shaw, A. R. G., Montgomery, A. A., Murphy, D. J., & DiAMOND Study Group. (2006). Women's experience of decision making about mode of delivery after a previous caesarean section: The role of health professionals and information about health risks. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 113(12), 1438–1445. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, B. E., Osterman, M. J., Driscoll, A. K., & Rossen, L. M. (2018). Births: Provisional data for 2017. Vital Statistics Rapid Release, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph-Williams, N., Lloyd, A., Edwards, A., Stobbart, L., Tomson, D., Macphail, S., … Thomson, R. (2017). Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: Lessons from the MAGIC programme. British Medical Journal, 357, j1744. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Légaré, F., & Thompson-Leduc, P. (2014). Twelve myths about shared decision making. Patient Education and Counseling, 96(3), 281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Registry of Vital Records and Statistics. (2018). Massachusetts births 2016. Retrieved from https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2018/06/01/birth-report-2016.pdf

- Metz, T. D., Stoddard, G. J., Henry, E., Jackson, M., Holmgren, C., & Esplin, S. (2013). How do good candidates for trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) who undergo elective repeat cesarean differ from those who choose TOLAC? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 208(6), 458.e1–458.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro, S., Janssen, P., Corbett, K., Wilcox, E., Bansback, N., & Kornelsen, J. (2017). Seeking control in the midst of uncertainty: Women's experiences of choosing mode of birth after caesarean. Women and Birth, 30(2), 129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Partnership for Women and Families. (2017). Cesarean birth trends in the United States 1989-2015. Retrieved from http://www.nationalpartnership.org/research-library/maternal-health/cesarean-section-trends-1989-2014.pdf

- Shorten, A., Shorten, B., Fagerlin, A., Illuzzi, J., Kennedy, H. P., Pettker, C., … Whittemore, R. (2019). A study to assess the feasibility of implementing a web-based decision aid for birth after cesarean to increase opportunities for shared decision making in ethnically diverse settings. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health, 64(1), 78–87. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorten, A., Shorten, B., & Kennedy, H. P. (2014). Complexities of choice after prior cesarean: A narrative analysis. Birth, 41(2), 178–184. doi: 10.1111/birt.12082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorten, A., Shorten, B., Keogh, J., West, S., & Morris, J. (2005). Making choices for childbirth: A randomized controlled trial of a decision-aid for informed birth after cesarean. Birth, 32(4), 252–261. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00383.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, D., Légaré, F., Lewis, K., Barry, M. J., Bennett, C. L., Eden, K. B., … Trevena, L. (2017). Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4(4), CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torigoe, I., & Shorten, A. (2018). Using a pregnancy decision support program for women choosing birth after a previous caesarean in Japan: A mixed methods study. Women and Birth, 31(1), e9–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey, T. J. G. (2016). A note on socially desirable responding. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(2), 224–232. doi: 10.1037/cou0000135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler, R. (2012). Six steps of shared decision making. Informed medical decisions foundation. Retrieved from https://www.mainequalitycounts.org/image_upload/SixStepsSDM2.pdf.