Abstract

Optogenetics and chemogenetics provide the ability to modulate neurons in a type-and region-specific manner. These powerful techniques are useful to test hypotheses regarding the neural circuit mechanisms of general anesthetic end points such as hypnosis and analgesia. With both techniques, a genetic strategy is used to target expression of light-sensitive ion channels (opsins) or designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs in specific neurons. Optogenetics provides precise temporal control of neuronal firing with light pulses, whereas chemogenetics provides the ability to modulate neuronal firing for several hours with the single administration of a designer drug. This chapter provides an overview of neuronal targeting and experimental strategies and highlights the important advantages and disadvantages of each technique.

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the 1980s, there has been great progress in identifying the molecular targets of general anesthetics, and it is now evident that multiple molecular mechanisms are involved in general anesthesia (Covarrubias, Barber, Carnevale, Treptow, & Eckenhoff, 2015; Eckenhoff, 2001; Eger et al., 1997; Grasshoff, Rudolph, & Antkowiak, 2005). Although the receptor targets likely to be responsible for the behavioral actions of general anesthetics have been identified, it is still unclear how the molecular actions of these drugs lead to specific behavioral end points such as unconsciousness, analgesia, and amnesia. Recently, there has been growing interest in understanding the mechanisms of anesthetic actions at the level of neural circuits and systems, and emerging evidence suggests that anesthetic drugs produce their profound behavioral effects by acting at discrete neural circuits (Brown, Purdon, & Van Dort, 2011; Devor & Zalkind, 2001) such as endogenous pathways that modulate sleep and arousal (Franks, 2008; Mashour & Pal, 2012; Moore et al., 2012). The recent development of optogenetics and chemogenetics has revolutionized systems neuroscience by allowing for targeted excitation and inhibition of specific neuronal subpopulations in discrete brain regions. For both techniques, a genetic strategy is employed to insert photoactivatable ion channels (opsins, for optogenetics) or designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDs, for chemogenetics) in specific neurons.

For optogenetics, a light-sensitive ion channel is expressed in targeted cells, allowing for neuronal depolarization or hyperpolarization with pulses of light (Deisseroth, 2011). Although a permanent intracranial implant is required to deliver the light pulses, one key advantage of optogenetics is the ability to have precise temporal control of neuronal activity. For chemogenetics, the expression of DREADDs is targeted to specific neurons. DREADDs are modified G protein-coupled “designer” receptors that are engineered to have low affinity for their native ligand, but high affinity for a synthetic, otherwise inert “designer” ligand that can be administered locally or systemically to induce neuronal activation or inhibition. Unlike optogenetics, chemogenetics does not offer the temporal resolution to rapidly activate or silence neurons, and the administration of a drug (i.e., designer ligand) is necessary. However, chemogenetics provides the advantages of not requiring chronic intracranial implants, and allowing for sustained neural excitation or inhibition for several hours with a single drug administration.

Studies that utilize optogenetics or chemogenetics to study sleep and arousal are emerging rapidly. For example, optogenetic activation of cholinergic neurons in the pedunculopontine tegmentum or laterodorsal tegmentum has been shown to induce rapid eye movement sleep (Van Dort et al., 2015). Although the use of optogenetics and chemogenetics has grown briskly in the neuroscience literature, relatively few studies have employed these techniques to study anesthetic mechanisms. It has been reported that chemogenetic activation of noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus accelerates emergence from isoflurane anesthesia in mice (Vazey & Aston-Jones, 2014), and more recently, it was shown that optogenetic activation of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) restores the righting reflex in anesthetized mice (Taylor et al., 2016). These studies suggest that arousal-promoting noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurons are important for emergence from general anesthesia. However, there are many other arousal-promoting pathways and neurotransmitters in the brain (Brown et al., 2011; Franks, 2008; Van Dort, Baghdoyan, & Lydic, 2008), and it is important to understand their respective roles in anesthetic induction and emergence.

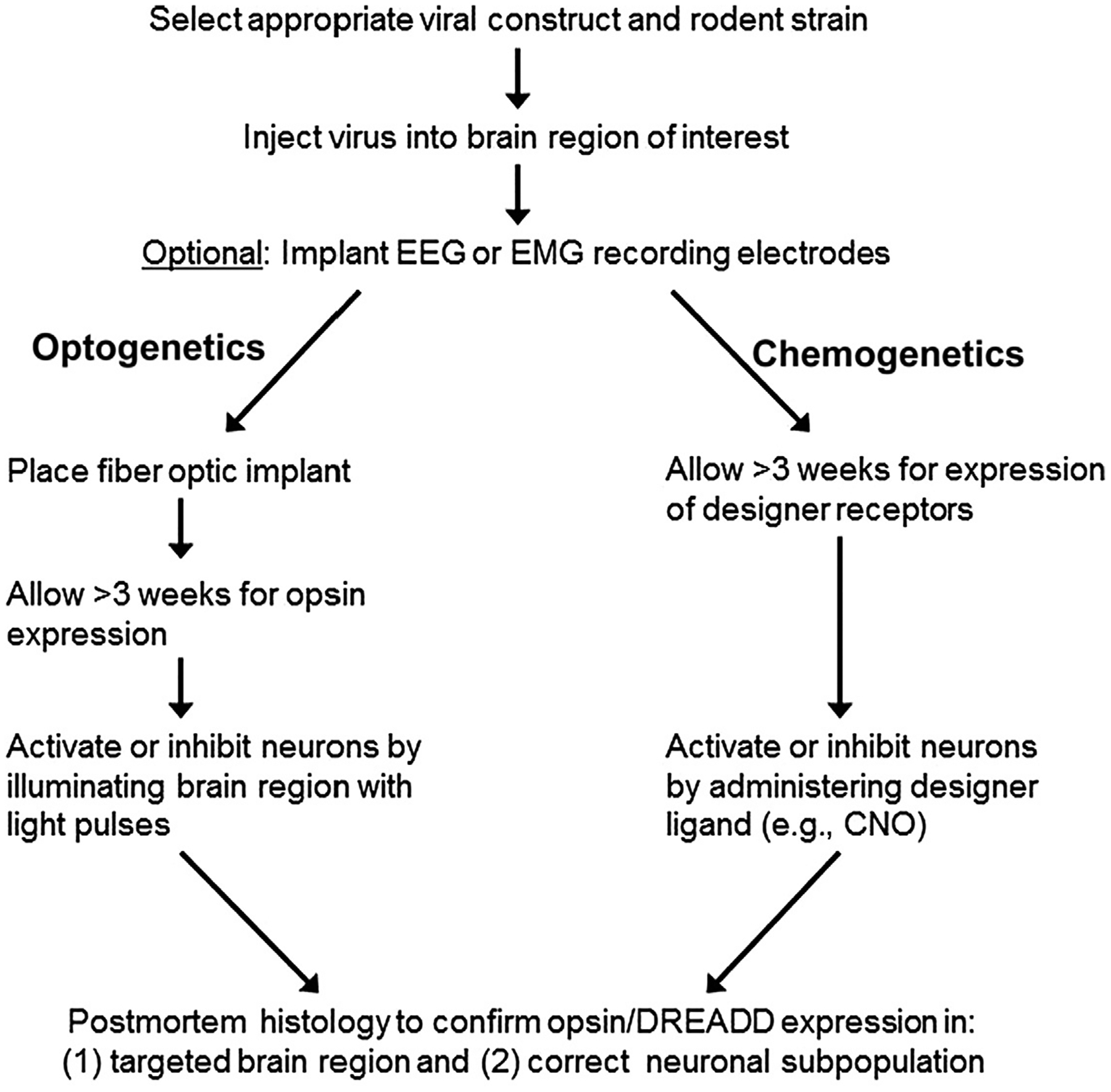

Another key component of general anesthesia is analgesia (Brown, Lydic, & Schiff, 2010), and recently, it was demonstrated that nociception is suppressed by chemogenetic activation of glutamatergic neurons, or inhibition of GABAergic neurons, in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray area (Samineni et al., 2017). With neural circuit manipulations, a variety of behavioral end points may be selected to test for effects relevant to anesthesia (e.g., hypnosis, antinociception, and immobility). However, this chapter will focus primarily on optogenetic and chemogenetic methods to target specific neural circuits, rather than behavioral assays. A flowchart showing the typical sequence of procedures and experiments is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart showing the typical sequence of events for performing optogenetics or chemogenetics experiments.

2. USING GENETIC TOOLS TO TARGET SPECIFIC NEURONS

In order to achieve specific neural circuit manipulations with optogenetics or chemogenetics, one of the most important aspects to consider is the targeting strategy. There are many ways to target subpopulations of neurons, their cell bodies, or projections, and Kim et al. provide an excellent overview of current methods (Kim, Adhikari, & Deisseroth, 2017). For both optogenetics and chemogenetics, genetically modified rodents that express the enzyme Cre recombinase (Cre) under the transcriptional control of a specific gene are typically used to target neuronal subpopulations. For example, vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT)-Cre mice express Cre only in GABAergic neurons that express VGAT. Many different mouse lines with stable and heritable expression of Cre are commercially available through Jackson Labs and other breeding facilities, allowing investigators to target and manipulate a variety of different neuronal subpopulations.

In order to gain anatomic specificity of opsin or DREADD expression, it is necessary to perform stereotaxic injections of viral vectors encoding these proteins in the brain regions of interest. Cre is an enzyme that catalyzes site-specific recombination between two LoxP sites, and modern Cre-driven viral vectors are constructed with “double-floxed” genes encoding the opsin or DREADD, causing gene expression only in transfected cells that contain Cre. A fluorescent tag is also encoded in the viral construct, allowing for postmortem histological confirmation of gene expression in the targeted cell type and brain region. Cre-inducible adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are commercially available from Addgene and other sources. These viruses are replication deficient and not known to cause disease in humans. Different AAV strains (e.g., AAV5 or AAV8) have specific transfection patterns in brain tissue, so it is important to test the viral construct for proper expression in the region of interest. After virus injection, a minimum of 3 weeks is recommended prior to performing experiments, to allow sufficient time for opsin or DREADD expression in transfected cells.

3. OPTOGENETICS

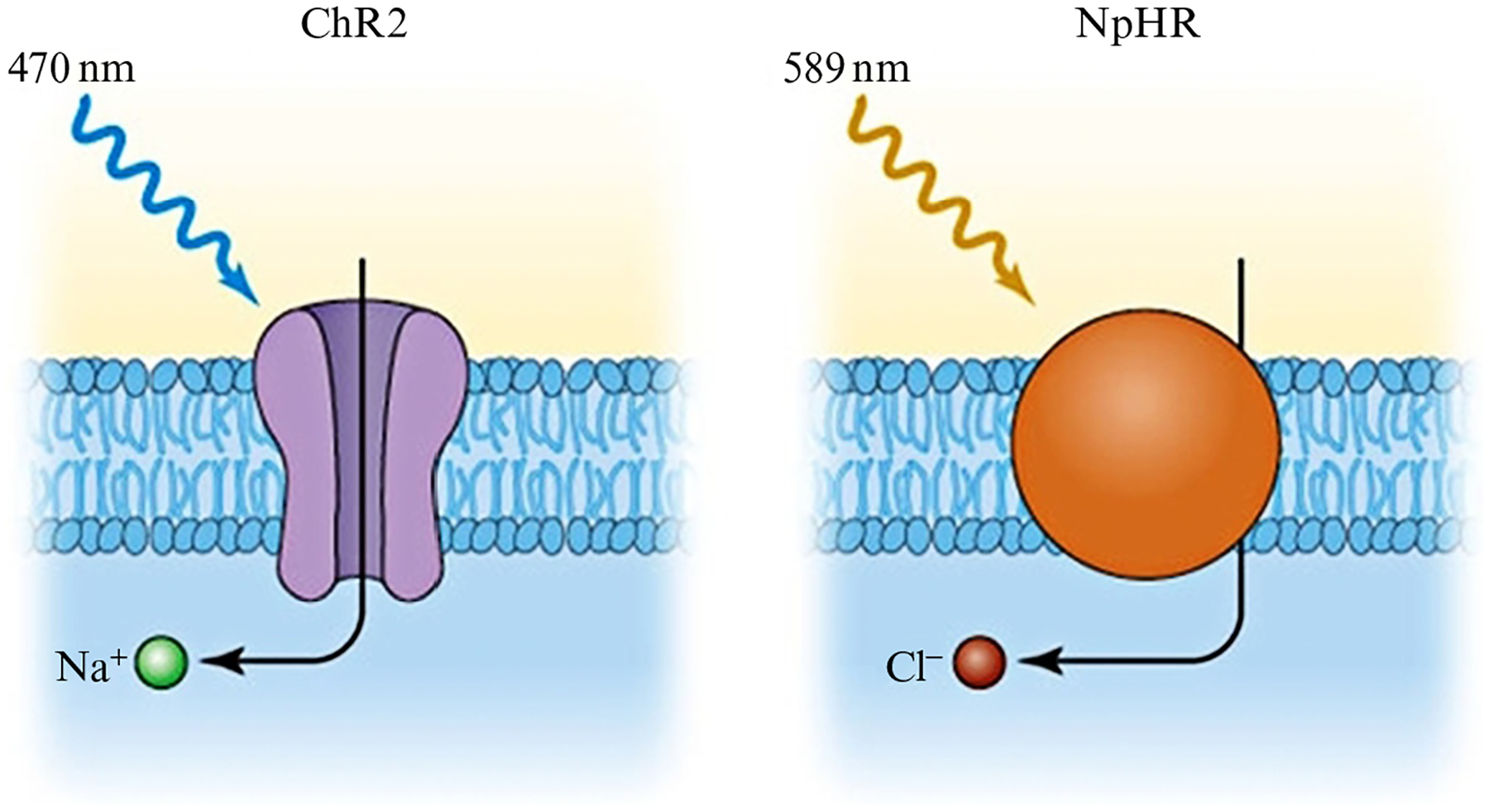

As shown in Fig. 2, with optogenetics, stimulatory opsins such as Channelrhodopsin2 (ChR2) are commonly used to depolarize neurons (Boyden, Zhang, Bamberg, Nagel, & Deisseroth, 2005), whereas inhibitory opsins such as halorhodopsin or Jaws may be used to silence neurons (Chuong et al., 2014). In order to illuminate the opsin-containing neurons, it is necessary to place a fiber optic implant above the brain region of interest. The implantation is typically performed immediately after the virus injection during a single surgical operation, although it may also take place during a separate surgery several weeks after the virus injection, when transfection and protein expression have already taken place. Details of the stereotaxic surgery are described later. After neurosurgery, a minimum of 1 week is recommended to allow for sufficient recovery and healing prior to experimentation.

Fig. 2.

Illumination of neurons that express channelrhodopsin2 (ChR2) with blue light (470 nm) allows Na+ ions to enter the cell, causing depolarization. Illumination of neurons that express halorhodopsin (NpHR) with yellow-orange light (589 nm) causes Cl− ions to be pumped into the cell, inducing hyperpolarization.

To perform optogenetics experiments, a light source such as a laser or LED and a method of controlling the timing of light pulses (e.g., a stimulus generator) are needed for precisely timed activation or inhibition of neurons. Each opsin is activated by specific wavelengths of light, so it is necessary to ensure that the correct wavelength is used to modulate the selected opsin. A patch cord is also necessary to connect the implanted fiber optic to the light source. Alternatively, an LED-mounted fiber optic may be used.

There are three main parameters to consider for the light pulses: duration (5–15 ms), frequency (1–50 Hz), and intensity (1–10 mW). For neuronal activation, it is often desirable to mimic “normal” neurophysiology, so for initial settings it may be helpful to consider the natural firing rates and patterns of the targeted neurons. ChR2 is the most commonly used opsin and can reliably cause neurons to fire at 20–40 Hz (Boyden et al., 2005). For faster firing rates, new ChR2 mutants such as ChETAH have been introduced, which allow neurons to fire at up to 200 Hz (Gunaydin et al., 2010). A typical set of parameters for ChR2 is to use a blue light 473 mm laser, with 5 ms light pulses at a frequency of 5 Hz, and a light intensity of 5 mW.

For neuronal inhibition, there are several inhibitory opsins available such as halorhodopsin (eNpHR3.0) which is a chloride pump that induces cellular hyperpolarization with yellow or green light (Gradinaru et al., 2010). A red-shifted cruxhalorhodopsin (Jaws) was recently introduced that has greater photocurrrents than halorhodopsin, and allows for the possibility of noninvasive photoinhibition as red light penetrates brain tissue more efficiently than blue light (Chuong et al., 2014).

Cell bodies may be illuminated to activate or inhibit all of the targeted neurons in a given brain region (e.g., VTA dopamine neurons), but terminal field illumination may also be used to test the effect of modulating a neural circuit that projects to a specific brain region. For example, by injecting a viral construct encoding ChR2 in the VTA of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-Cre mice, VTA dopamine neurons that contain TH will express ChR2 not only in the cell bodies contained in the VTA but also in the axons that project to various brain regions. By illuminating the terminals in the target region rather than the cell bodies in the VTA, selective activation of dopamine neurons projecting from the VTA to specific brain regions can be achieved. This approach was recently utilized to demonstrate that photostimulation of dopamine neurons projecting from the VTA to the nucleus accumbens promotes wakefulness (Eban-Rothschild, Rothschild, Giardino, Jones, & de Lecea, 2016).

4. CHEMOGENETICS

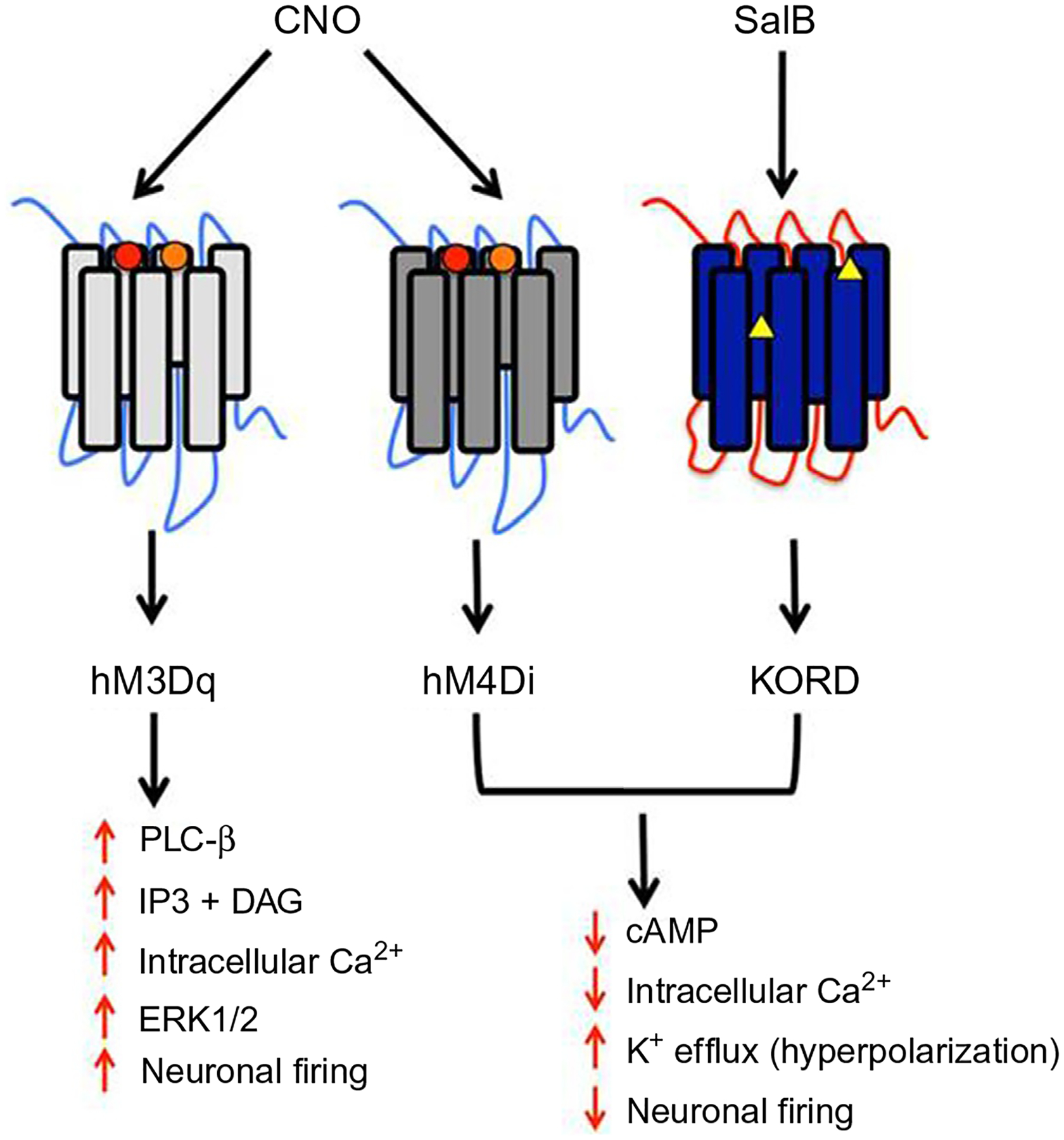

With chemogenetics, DREADDs are used to activate or inhibit targeted neurons, rather than opsins. As shown in Fig. 3, the stimulatory DREADD hM3Dq is a modified human M3 muscarinic receptor that has low affinity for the native ligand acetylcholine, but high affinity for the synthetic ligand clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) (Armbruster, Li, Pausch, Herlitze, & Roth, 2007). When this Gq-coupled receptor is activated with local or systemic administration of CNO, targeted neurons undergo burst firing (Alexander et al., 2009). For neuronal inhibition, the Gi-coupled hM4Di DREADD (a modified human M4 muscarinic receptor) is often used to silence targeted neurons with CNO (Urban & Roth, 2015). CNO causes a downstream signaling cascade leading to either burst firing (for hM3Dq) or silencing (for hM4Di) of the targeted neurons, allowing for prolonged neuronal excitation or inhibition. In mice, the effects of intraperitoneally injected CNO are observed in 10–15 min, peak at 45–50 min, and slowly return to baseline over approximately 9 h (Alexander et al., 2009). CNO is soluble in aqueous solutions such as normal saline, and for mice investigators typically use 0.1–3 mg/kg CNO injected intraperitoneally (Roth, 2016), although intracranial microinjections have also been used (Vazey & Aston-Jones, 2014).

Fig. 3.

Human muscarinic (hM)-based DREADDs are activated by clozapine-N-oxide (CNO), whereas kappa opioid receptor (KOR)-based DREADDs are activated by Salvinorin B (SalB). CNO causes burst firing of neurons that express hM3Dq, and inhibition of neurons that express hM4Di. SalB inhibits neurons that express KORD, allowing for bidirectional chemogenetics in neurons that express both hM3Dq and KORD.

Recently, it was reported that hM3Dq and hM4Di DREADDs are activated by clozapine (a metabolite of CNO that crosses the blood–brain barrier) rather than CNO (Gomez et al., 2017). Because clozapine is an antipsychotic drug that may cause sedation at high doses, this finding stressed the importance of using low doses of CNO for chemogenetics experiments, and performing proper control experiments by administering CNO to animals that do not express hM3Dq and hM4Di DREADDs (Roth, 2016).

In 2015, a new kappa opioid receptor-based DREADD (KORD) was reported that allows for neuronal silencing with salvinorin B (SalB) (Vardy et al., 2015). This new DREADD has made it possible to conduct bidirectional chemogenetics by activating or inhibiting the same neurons with different ligands. However, SalB (available through Sigma-Aldrich, Cayman Chemicals, etc.) is relatively insoluble in aqueous solution, and therefore chemical solvents such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) may be required for parenteral administration. Depending on the experimental design, additional controls may need to be performed to test if the vehicle (e.g., DMSO) produces any significant effects. The kinetics of SalB are also quite different from CNO, with behavioral effects appearing shortly after injection and lasting about 1 h (Vardy et al., 2015). Although the KORD/SalB system provides the unique advantage of bidirectional chemogenetic control of the same neurons (when used in conjunction with hM3Dq/CNO), the hM4Di/CNO system is more useful when longer term neuronal inhibition is desired. Other DREADD constructs include β-arrestin-preferring DREADD and Gs DREADD, though these are less commonly used (Roth, 2016).

Similar to terminal field illumination with optogenetics, axonal projections may also be targeted selectively with chemogenetics. There are generally two approaches to achieve this aim. The first is to administer the designer ligand (e.g., CNO) locally (rather than systemically) via microinjection in the target site. The second approach is to use a genetic strategy to restrict DREADD expression to a specific circuit, which allows for selective activation or inhibition with systemic administration of CNO. The latter method provides the distinct advantage of not requiring an invasive intracranial implant, which is useful when a freely behaving animal is desired for behavioral analysis. To achieve selective DREADD expression in a specific circuit, a canine adenovirus (CAV2-Cre) may be injected in the projection site, causing retrograde transport to cell bodies, leading to the expression of Cre. When a Cre-driven AAV encoding the DREADD is injected in the location containing cell bodies, only cells that project to the target site of interest will express Cre, leading to selective DREADD expression in neurons that project to that site (Urban & Roth, 2015). Because the CAV2-Cre viral construct is used to induce expression of Cre, another advantage of this approach is that genetically modified animals are not needed.

5. STEREOTAXIC SURGERY

Below is a sample protocol for stereotaxic neurosurgery, including steps for virus injection as well as optional implantation of fiber optics and electroencephalogram (EEG) electrodes.

5.1. Major Equipment

Stereotaxic frame for rodents with anesthesia mask

Microinjector

Micro bead sterilizer or autoclave

Anesthetic induction chamber, vaporizer, and scavenging system

Micropipette puller

Electric microdrill for making craniotomies

Light source (laser or LED, for optogenetics only)

Stimulus generator (for optogenetics only)

Recording system for EEG (optional)

5.2. Preoperative Preparation

Sterilize surgical tools in a micro bead sterilizer or autoclave

- Gather materials:

- Sterile gauze

- Sterile cotton tip applicators

- Eye lubricant

- Extra fine tip pen or pencil

- Electric drill and drill bits

- Bone anchor screws and compatible screw driver

- Silicone cup to mix dental acrylic

- Dental acrylic (powder+liquid)

- Suture

- Fiber optic implant and EEG electrodes (optional)

- Fill four small (25 mL) beakers with

- 70% ethanol (place bone anchor screws and drill bit in the alcohol to sterilize)

- 3% hydrogen peroxide

- Povidone-iodine solution

- Saline

If using isoflurane as the anesthetic, ensure that the isoflurane vaporizer and oxygen tank are full

Turn on fiber optic illuminator and heating pad to preheat (this will be used to maintain the core body temperature at approximately 37°C)

5.3. Preparation of Virus

Choose an area adjacent to the surgical area that will be dedicated to loading the micropipettes with virus, and cover it with absorbent lab bench paper.

Place an aliquot of virus in a container of ice in this area, and allow the virus to thaw on ice as the surgery is being performed.

Set up a waste container of 10% bleach in the dedicated virus handling area for disposing of pipette tips, etc., that come in contact with the virus.

Pull a glass Wiretrol micropipette to a tip diameter of approximately 20 μm. Fill a Hamilton syringe (Model 701 LT), a microelectrode adaptor (WPI catalog #MPH6S10), and the glass micropipette with mineral oil and secure the apparatus in a microinjector.

5.4. Animal Preparation

Weigh animal and place in an anesthetic induction chamber

Administer 2.5%–3% isoflurane in oxygen

Wait for the animal to lose the righting reflex, and then wait another 60 s before handling

Remove the animal from the induction chamber and clip the scalp hair with an electric shaver, from between the eyes (anteriorly) to the neck (posteriorly)

- Place the animal in the stereotaxic frame with the nose on the bite bar and the ear bars in the ear canal, ensuring that the animal remains adequately anesthetized

- Ear bar readings should be the same on both sides to ensure that the head is correctly positioned in the center

Apply eye lubricant and insert a rectal temperature probe to ensure that the animal’s core body temperature is maintained at 37°C

Once the animal is positioned, sterilize the shaved scalp area where the incision will be made with 70% ethanol and povidone-iodine solution. Start in the center and work your way out in circles. Alternate cleaning with alcohol and povidone-iodine solution 3 × each

Assess anesthetic depth regularly by observing the respiratory rate and testing for movement in response to paw pinch

5.5. Surgery

Put on sterile gloves prior to making the incision

Make a vertical incision in the center of the scalp

Clean the skull surface with a cotton-tipped applicator soaked in saline or hydrogen peroxide

Level the head by measuring the vertical height of bregma and lambda (aim for a difference in height between bregma and lambda of less than 0.05 mm)

Calculate the stereotaxic targets and mark the locations with a fine tip pen for viral injection sites as well as bone anchor screws, fiber optics, and EEG electrodes (as needed)

- Drill craniotomies for viral injection sites and bone anchor screws, fiber optics and EEG electrodes (as needed)

- In rats, the dura is thicker than mice, so it is important to make sure that the dura is cleared using fine-tipped tweezers or a small hooked 27G needle before placing the delicate glass pipette for viral injection or bendable electrodes.

- If bleeding occurs use sterile cotton tip applications and saline to stop the bleeding

- If implanting fiber optics or EEG electrodes, aim for six bone anchor screw holes distributed around the skull bones

5.6. Virus Injection

Pipette 1.0 μL of virus for a 0.5 μL injection onto a small piece of para-film (typical viral injection volumes are 0.2–0.5 μL). The optimal viral titer depends on the AAV serotype, promoter, and size of the target brain region. Therefore, the optimal viral titer must be determined empirically for each set of experiments.

Place the tip of the micropipette into the viral stock and manually withdraw the plunger

If drawing viral stock into the micropipette is difficult, the micropipette tip can be enlarged slightly by cutting it

Move plunger down until a small amount of virus is dispelled from the tip of the micropipette, and remove this small drop with a cotton tip applicator and discard in a virus waste container

Apply a drop of mineral oil to the tip of the micropipette to prevent clogging as the micropipette is lowered into the brain

Using X- and Y-axis stereotaxic coordinates from bregma, position the micropipette over the area to be injected. Very slowly lower the micropipette (at an approximate rate of 1 mm/min) to the proper Z-axis position

Enter the desired injection parameters into the microinjector controller box (SYS Micro4) and initiate the injection (e.g., 0.5 μL over 10 min)

When the injection is complete, leave the pipette for 5–15 min to prevent efflux of virus during removal

Very slowly remove the micropipette from the brain (approximately 1 mm/min).

If no further fiber optic or EEG implant is planned, suture the skin closed

Administer a postsurgical analgesic such as the nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) ketoprofen or equivalent at the end of surgery, and for at least 2 days postoperatively. If a more potent analgesic is necessary, buprenorphine may be used.

5.7. Optional Steps for Implantation of Fiber Optics or EEG Electrodes

Place all bone anchor screws using a small screwdriver. Turn screws 1.5–2.5 turns, so they are stable but not protruding into the brain. Ensure there is enough space for acrylic between the screw head and skull surface: we use 0.7 mm diameter anchor screws from Antrim for mice and Stoelting bone anchor screws for rats.

For EEG recordings, check ground screw impedance (should be less than 20 kΩ when measured between the ground screw and the other anchor screws) and place EEG electrodes just under the skull.

For fiber optic implants, stereotaxically place the fiber optic over the brain area of interest.

Cover bone anchor screws and fiber optic or EEG electrodes with dental acrylic, making sure to leave smooth edges in order to avoid skin irritation.

If the skin is loose around the implant, add a suture just behind the implant to close the skin.

Administer a postsurgical analgesic such as the NSAID ketoprofen or equivalent at the end of surgery, and for at least 2 days postoperatively. If a more potent analgesic is necessary, buprenorphine may be used.

5.8. Cleanup

Rinse the glass micropipette with 10% bleach and discard it in a sharps container

Discard waste container

Discard lab bench paper into biohazard bin and wipe down all surfaces and instruments that may have come in contact with the virus with 10% bleach

Unused virus may be refrozen, but keep in mind that repeated freeze/thaw cycles will cause virus degradation

Allow at least 1 week for full recovery from surgery, at which time baseline behavioral and EEG data may be collected

Allow approximately 2–3 weeks for viral transfection and gene expression to occur before attempting neural circuit manipulations

6. CONTROL EXPERIMENTS

For both optogenetics and chemogenetics experiments, controls are needed to ensure the effect is specific to the opsin or DREADD. Ideally, the control animals have the same genetic background and receive an injection of a control AAV encoding only a fluorescent tag without opsins or DREADDs. For chemogenetics experiments in particular, these controls are essential to assess potential nonspecific effects of the designer ligand. In addition, for chemogenetics a vehicle control for the ligand (e.g., normal saline) is also useful. For optogenetic experiments, a similar control strategy is also necessary (i.e., illumination of the same brain region in animals that received an injection of a control AAV that does not encode the opsin) to ensure that any observed behaviors are not due to nonspecific effects such as heating of the brain tissue, or the viral injection.

7. HISTOLOGY AND VERIFICATION OF RECEPTOR FUNCTION

After completing all behavioral experiments, it is necessary to show that the opsin or DREADD was expressed in the targeted cell type and the correct brain region using histological analysis. The exact histological method depends on the cell type targeted and scientific question. For most applications, immunohistochemistry (IHC) is used to label specific cell types. In cases where IHC does not work well (e.g., targeting GABAergic or glutamatergic neurons in the brainstem), other methods like fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) can be used to target RNA. In order to perform IHC, animals are euthanized and transcardially perfused with formalin to fix the brain. The fixed brain is then sliced into thin sections (40–60 μm) using a vibratome. For FISH, the animal is deeply anesthetized and the brain is removed and frozen fresh, then sectioned at 10–15 μm on a cryostat. Brain sections are imaged using a fluorescent or confocal microscope. Once the brain sections are stained with IHC or FISH and imaged, colocalization of the opsin or DREADD and the stained marker is confirmed. For optogenetic experiments and chemogenetic experiments involving electro-physiological recordings, histology is used to identify the anatomic location of electrodes and fiber optic implants. Finally, to confirm that illumination (for optogenetics) or designer ligand application (for chemogenetics) induces the expected changes in neuronal firing, fresh brain slices from experimental animals can be used to perform whole-cell patch clamp recordings.

8. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Optogenetics and chemogenetics provide powerful new tools to probe the neural circuits and systems in the brain where anesthetics act to produce their profound behavioral effects. These techniques also provide the ability to test hypotheses regarding whether the neural circuits that induce sleep are also involved in anesthetic hypnosis. Using different behavioral assays, investigators may also employ neural circuit manipulations to test for other anesthetic end points such as analgesia and amnesia. Future studies using neural circuit manipulations will likely provide many new mechanistic insights into how the behavioral end points that define general anesthesia are produced.

REFERENCES

- Alexander GM, Rogan SC, Abbas AI, Armbruster BN, Pei Y, Allen JA, et al. (2009). Remote control of neuronal activity in transgenic mice expressing evolved G protein-coupled receptors. Neuron, 63, 27–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, & Roth BL (2007). Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104, 5163–5168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, & Deisseroth K (2005). Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nature Neuroscience, 8, 1263–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EN, Lydic R, & Schiff ND (2010). General anesthesia, sleep, and coma. The New England Journal of Medicine, 363, 2638–2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EN, Purdon PL, & Van Dort CJ (2011). General anesthesia and altered states of arousal: A systems neuroscience analysis. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 34, 601–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong AS, Miri ML, Busskamp V, Matthews GA, Acker LC, Sorensen AT, et al. (2014). Noninvasive optical inhibition with a red-shifted microbial rhodopsin. Nature Neuroscience, 17, 1123–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covarrubias M, Barber AF, Carnevale V, Treptow W, & Eckenhoff RG (2015). Mechanistic insights into the modulation of voltage-gated ion channels by inhalational anesthetics. Biophysical Journal, 109, 2003–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K (2011). Optogenetics. Nature Methods, 8, 26–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devor M, & Zalkind V (2001). Reversible analgesia, atonia, and loss of consciousness on bilateral intracerebral microinjection of pentobarbital. Pain, 94, 101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eban-Rothschild A, Rothschild G, Giardino WJ, Jones JR, & de Lecea L (2016). VTA dopaminergic neurons regulate ethologically relevant sleep-wake behaviors. Nature Neuroscience, 19, 1356–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckenhoff RG (2001). Promiscuous ligands and attractive cavities: How do the inhaled anesthetics work? Molecular Interventions, 1, 258–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eger EI 2nd, Koblin DD, Harris RA, Kendig JJ, Pohorille A, Halsey MJ, et al. (1997). Hypothesis: Inhaled anesthetics produce immobility and amnesia by different mechanisms at different sites. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 84, 915–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks NP (2008). General anaesthesia: From molecular targets to neuronal pathways of sleep and arousal. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 9, 370–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez JL, Bonaventura J, Lesniak W, Mathews WB, Sysa-Shah P, Rodriguez LA, et al. (2017). Chemogenetics revealed: DREADD occupancy and activation via converted clozapine. Science, 357, 503–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradinaru V, Zhang F, Ramakrishnan C, Mattis J, Prakash R, Diester I, et al. (2010). Molecular and cellular approaches for diversifying and extending optogenetics. Cell, 141, 154–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasshoff C, Rudolph U, & Antkowiak B (2005). Molecular and systemic mechanisms of general anaesthesia: The ‘multi-site and multiple mechanisms’ concept. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology, 18, 386–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunaydin LA, Yizhar O, Berndt A, Sohal VS, Deisseroth K, & Hegemann P (2010). Ultrafast optogenetic control. Nature Neuroscience, 13, 387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CK, Adhikari A, & Deisseroth K (2017). Integration of optogenetics with complementary methodologies in systems neuroscience. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 18, 222–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashour GA, & Pal D (2012). Interfaces of sleep and anesthesia. Anesthesiology Clinics, 30, 385–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JT, Chen J, Han B, Meng QC, Veasey SC, Beck SG, et al. (2012). Direct activation of sleep-promoting VLPO neurons by volatile anesthetics contributes to anesthetic hypnosis. Current Biology, 22, 2008–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth BL (2016). DREADDs for neuroscientists. Neuron, 89, 683–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samineni VK, Grajales-Reyes JG, Copits BA, O’Brien DE, Trigg SL, Gomez AM, et al. (2017). Divergent modulation of nociception by glutamatergic and GABAergic neuronal subpopulations in the periaqueductal gray. eNeuro, 4, 0129–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor NE, Van Dort CJ, Kenny JD, Pei J, Guidera JA, Vlasov KY, et al. (2016). Optogenetic activation of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area induces reanimation from general anesthesia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(45), 12826–12831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban DJ, & Roth BL (2015). DREADDs (designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs): Chemogenetic tools with therapeutic utility. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 55, 399–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dort CJ, Baghdoyan HA, & Lydic R (2008). Neurochemical modulators of sleep and anesthetic states. International Anesthesiology Clinics, 46, 75–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dort CJ, Zachs DP, Kenny JD, Zheng S, Goldblum RR, Gelwan NA, et al. (2015). Optogenetic activation of cholinergic neurons in the PPT or LDT induces REM sleep. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112, 584–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardy E, Robinson JE, Li C, Olsen RH, DiBerto JF, Giguere PM, et al. (2015). A new DREADD facilitates the multiplexed chemogenetic interrogation of behavior. Neuron, 86, 936–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazey EM, & Aston-Jones G (2014). Designer receptor manipulations reveal a role of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic system in isoflurane general anesthesia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111, 3859–3864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]