Abstract

Background

Many women would like to avoid pharmacological or invasive methods of pain management in labour and this may contribute towards the popularity of complementary methods of pain management. This review examined currently available evidence supporting the use of alternative and complementary therapies for pain management in labour.

Objectives

To examine the effects of complementary and alternative therapies for pain management in labour on maternal and perinatal morbidity.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (February 2006), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2006, Issue 1), MEDLINE (1966 to February 2006), EMBASE (1980 to February 2006) and CINAHL (1980 to February 2006).

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria included published and unpublished randomised controlled trials comparing complementary and alternative therapies (but not biofeedback) with placebo, no treatment or pharmacological forms of pain management in labour. All women whether primiparous or multiparous, and in spontaneous or induced labour, in the first and second stage of labour were included.

Data collection and analysis

Meta‐analysis was performed using relative risks for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences for continuous outcomes. The outcome measures were maternal satisfaction, use of pharmacological pain relief and maternal and neonatal adverse outcomes.

Main results

Fourteen trials were included in the review with data reporting on 1537 women using different modalities of pain management; 1448 women were included in the meta‐analysis. Three trials involved acupuncture (n = 496), one audio‐analgesia (n = 24), two trials acupressure (n = 172), one aromatherapy (n = 22), five trials hypnosis (n = 729), one trial of massage (n = 60), and relaxation (n = 34). The trials of acupuncture showed a decreased need for pain relief (relative risk (RR) 0.70, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.49 to 1.00, two trials 288 women). Women taught self‐hypnosis had decreased requirements for pharmacological analgesia (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.79, five trials 749 women) including epidural analgesia (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.40) and were more satisfied with their pain management in labour compared with controls (RR 2.33, 95% CI 1.15 to 4.71, one trial). No differences were seen for women receiving aromatherapy, or audio analgesia.

Authors' conclusions

Acupuncture and hypnosis may be beneficial for the management of pain during labour; however, the number of women studied has been small. Few other complementary therapies have been subjected to proper scientific study.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Acupuncture Analgesia; Analgesia, Obstetrical; Analgesia, Obstetrical/methods; Aromatherapy; Complementary Therapies; Complementary Therapies/methods; Hypnosis; Labor Pain; Labor Pain/therapy; Music Therapy

Plain language summary

Complementary and alternative therapies for pain management in labour

Acupuncture and hypnosis may help relieve pain during labour, but more research is needed on these and other complementary therapies.

The pain of labour can be intense, with tension, anxiety and fear making it worse. Many women would like to labour without using drugs, and turn to alternatives to manage pain. Many alternative methods are tried in order to help manage pain and include acupuncture, mind‐body techniques, massage, reflexology, herbal medicines or homoeopathy, hypnosis and music. We found evidence that acupuncture and hypnosis may help relieve labour pain. There is insufficient evidence about the benefits of music, massage, relaxation, white noise, acupressure, aromatherapy, and no evidence about the effectiveness of massage or other complementary therapies.

Background

Labour presents a physiological and psychological challenge for women. As labour becomes more imminent this can be a time of conflicting emotions; fear and apprehension can be coupled with excitement and happiness. Tension, anxiety and fear are factors contributing towards women's perception of pain and may also affect their labour and birth experience. Pain associated with labour has been described as one of the most intense forms of pain that can be experienced (Melzack 1984). Pain experienced by women in labour is caused by uterine contractions, the dilatation of the cervix and, in the late first stage and second stage, by stretching of the vagina and pelvic floor to accommodate the baby. However, the complete removal of pain does not necessarily mean a more satisfying birth experience for women (Morgan 1982). Effective and satisfactory pain management need to be individualised for each woman. The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has become popular with consumers worldwide. Studies suggest that between 30% and 50% of adults in industrialised nations use some form of CAM to prevent or treat health‐related problems (Astin 1998). Complementary therapies are more commonly used by women of reproductive age, with almost half (49%) reporting use (Eisenberg 1998). It is possible that a significant proportion of women are using these therapies during pregnancy. A recent survey of 242 pregnant women in the United States reported that complementary therapies were used by 9% of women. Herbs were the most frequently used therapy (Gibson 2001). Many women would like to avoid pharmacological or invasive methods of pain relief in labour and this may contribute towards the popularity of complementary methods of pain management (Bennett 1999).

The Complementary Medicine Field of the Cochrane Collaboration defines complementary medicine as 'practices and ideas which are outside the domain of conventional medicine in several countries', which are defined by its users as 'preventing or treating illness, or promoting health and wellbeing' (Cochrane 2006). This definition is deliberately broad as therapies considered complementary practices in one country or culture may be conventional in another. Many therapies and practices are included within the scope of the Complementary Medicine Field. These include treatments people can administer themselves (e.g. botanicals, nutritional supplements, health food, meditation, magnetic therapy), treatments providers administer (e.g. acupuncture, massage, reflexology, chiropractic and osteopathic manipulations), and treatments people can administer under the periodic supervision of a provider (e.g. yoga, biofeedback, Tai Chi, homoeopathy, Alexander therapy, Ayurveda).

The most commonly cited complementary medicine and practices associated with providing pain management in labour can be categorised into mind‐body interventions (e.g. yoga, hypnosis, relaxation therapies), alternative medical practice (e.g. homoeopathy, traditional Chinese medicine), manual healing methods (e.g. massage, reflexology), pharmacologic and biological treatments, bioelectromagnetic applications (e.g. magnets) and herbal medicines. The use of immersion in water to reduce labour pain is not included in this review and is the subject of a separate Cochrane review (Cluett 2002).

Mind‐body interventions such as relaxation, meditation, visualisation and breathing are commonly used for labour, and can be widely accessible to women through teaching of these techniques during antenatal classes. Yoga, meditation and hypnosis may not be so accessible to women but together these techniques may have a calming effect and provide a distraction from pain and tension (Vickers 1999a).

Hypnosis appears to be a state of narrow focused attention, reduced awareness of external stimuli, and an increased response to suggestions (Gamsa 2003). Suggestions are verbal or non‐verbal communications that result in apparent spontaneous changes in perception, mood or behaviour. These therapeutic communications are directed to the patient's subconscious and the responses are independent of any conscious effort or reasoning. Women can learn self‐hypnosis which can be used in labour to reduce pain from contractions. Recent advances in neuro‐imaging have led to increased understanding of the neuro‐physiological changes occurring during hypnosis induced analgesia (Maquet 1999). The anterior cingulate gyrus has been demonstrated, by positron emission tomography, to be one of the sites in the brain affected by hypnotic modulation of pain (Faymonville 2000). The suppression of neural activity, between the sensory cortex and the amygdala‐limbic system, appears to inhibit the emotional interpretation of sensations being experienced as pain.

Acupuncture involves the insertion of fine needles into different parts of the body. Other acupuncture related techniques include laser acupuncture and acupressure (applying pressure on the acupuncture point). These techniques all aim to treat illnesses and soothe pain by stimulating acupuncture points. Acupuncture points used to reduce labour pain are located on the hands, feet and ears. Several theories have been presented as to exactly how acupuncture works. One theory proposes that pain impulses are blocked from reaching the spinal cord or brain at various 'gates' to these areas (Wall 1967). Since the majority of acupuncture points are either connected to, or located near, neural structures, this suggests that acupuncture stimulates the nervous system. Another theory suggests that acupuncture stimulates the body to produce endorphins, which reduce pain (Pomeranz 1989). Other pain‐relieving substances called opioids may be released into the body during acupuncture treatment (Ng 1992).

Aromatherapy, the use of the essential oils, draws on the healing powers of plants. The mechanism of action for aromatherapy is unclear. Studies investigating psychological and physiological effects of essential oils showed no change on physiological parameters such as blood pressure or heart rate but did produce psychological improvement in mood and anxiety levels (Stevensen 1995). Essential oils are thought to increase the output of the body's own sedative, stimulant and relaxing substances. The oils may be massaged into the skin, or inhaled by using a steam infusion or burner. Aromatherapy is increasing in popularity among midwives and nurses (Allaire 2000).

Homoeopathy works on the principle that 'like cures like'. Homoeopathic remedies are prescribed as potencies as a result of tiny and highly diluted amounts of the substances from which they are derived. The more times the substance is diluted and succussion (vigorous shaking) is performed, the greater the potency of the homoeopathic remedy. The principle of treatment is that the homoeopathic substance will stimulate the body and healing functions so achieving a state of balance with relief of symptoms. Homoeopathic remedies are all natural medicines. Remedies are derived from herbs, minerals or other natural substances. Remedies used in labour are given according to the type or types of pain being experienced and the emotions the woman is feeling. It is proposed that homoeopathy stimulates a woman's physiological processes so they function well, enabling her to cope with labour and to soothe and relax the woman emotionally which may reduce her pain (Charlish 1995).

Manual healing methods include massage and reflexology. Massage involves manipulation of the body's soft tissues. It is commonly used to help relax tense muscles and to soothe and calm the individual. A woman who is experiencing backache during labour may find massage over the lumbosacral area soothing. Some women find abdominal massage comforting. Different massage techniques may suit different women. Massage may help to relieve pain by assisting with relaxation, inhibiting pain signals or by improving blood flow and oxygenation of tissues (Vickers 1999b).

Reflexologists propose that there are reflex points on the feet corresponding to organs and structures of the body and that pain may be reduced by gentle manipulation or pressing certain parts of the foot. Pressure applied to the feet has been shown to result in an anaesthetizing effect on other parts of the body (Ernst 1997).

This review examines currently available evidence regarding the effectiveness of the above therapies and other alternative and complementary therapies for pain management in labour but not biofeedback, which will be the focus of another Cochrane review (Barragán Loayza 2006).

Readers may wish to refer to the following Cochrane systematic reviews for further information; 'Continuous support for women during childbirth' (Hodnett 2003), and for information on pharmaceutical methods of pain relief to 'Epidural versus non epidural analgesia or no analgesia in labour' (Anim‐Somuah 2005) and 'Types of intra‐muscular opioids for maternal pain relief in labour' (Elbourne 1998).

Objectives

To examine the effects of complementary and alternative therapies for pain management in labour on maternal and perinatal morbidity.

This review examines the hypotheses that the use of a complementary therapy is

an effective means of pain management in labour as measured by decreases in women's rating of labour pain: a reduced need for pharmacological intervention;

improved maternal satisfaction or maternal emotional experience; and

complementary and alternative medicine has no adverse effects on the mother (duration of labour, mode of deliver) or baby.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published and unpublished randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

All women whether primiparous or multiparous, and in spontaneous or induced labour, in the first and second stage of labour.

Types of interventions

Complementary and alternative therapies used in labour (but not biofeedback) with or without concurrent use of pharmacological or non‐pharmacological interventions compared with placebo, no treatment or pharmacological forms of pain management.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Maternal satisfaction or maternal emotional experience with pain management in labour.

Use of pharmacological pain relief in labour.

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

Length of labour; mode of delivery; instrumental vaginal delivery; need for augmentation with oxytocin; perineal trauma (defined as episiotomy and incidence of second or third degree tear); maternal blood loss (postpartum haemorrhage defined as greater than 600 ml); perception of pain experienced; satisfaction with general birth experience; assessment of mother‐baby interaction; and breastfeeding at hospital discharge.

Neonatal

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes; admission to neonatal intensive care unit; need for mechanical ventilation; neonatal encephalopathy.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (February 2006).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

monthly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness search of a further 37 journals.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the 'Search strategies for identification of studies' section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are given a code (or codes) depending on the topic. The codes are linked to review topics. The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using these codes rather than keywords.

In addition, we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2006, Issue 1), MEDLINE (1966 to February 2006), CINAHL (1980 to February 2006) and EMBASE (1980 to February 2006) using a combination of subject headings and text words. The subject headings included obstetrics, labor, birth, pain, complementary medicine, alternative medicine. The text words included the different complementary therapies: "acupuncture, reflexology, aromatherapy, massage, homoeopathy, yoga, meditation, imagery or visualisation, relaxation, hypnosis, breathing exercises".

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

We evaluated trials for their appropriateness for inclusion. Where there was uncertainty about inclusion of the study, the full text was retrieved. The original author was contacted for further information where possible. If there was disagreement between review authors about the studies to be included that could not be resolved by discussion, assistance from the third review author was sought. Reasons for excluding trials have been stated. Excluded studies are detailed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Following an assessment for inclusion, we assessed the methodology of the trial. The data were extracted onto hard copy data sheets. Caroline Smith, Carmel Collins and Allan Cyna extracted the data and assessed the quality. Two review authors assessed and extracted data for each trial.

Included trials were assessed according to the following five main criteria: (1) adequate concealment of treatment allocation (for example, opaque, sealed, numbered envelopes); (2) method of allocation to treatment (for example, by computer randomisation, random‐number tables); (3) adequate documentation of how exclusions were handled after treatment allocation ‐ to facilitate intention‐to‐treat analysis; and (4) adequate blinding of outcome assessment.

Letters were used to indicate the quality of the included trials (Higgins 2005), for example: (1) A was used to indicate a trial that had a high level of quality in which all the criteria were met; (2) B was used to indicate that one or more criteria were partially met or it was unclear if all the criteria were met; and (3) C was used if one or more criteria were not met.

We entered data directly from the published reports into the Review Manager software (RevMan 2003) with double data entry performed by a co‐author (Carmel Collins). Where data were not presented in a suitable format for data entry, or if data were missing, we sought additional information from the trialists by personal communication in the form of a letter or email.

Due to the nature of the interventions, double blinding of assessments may not be possible. Therefore, studies without double blinding of assessments were considered for inclusion. Data extracted from the trials were analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis (when this was not done in the original report, re‐analysis was performed if possible). Where data were missing, we sought clarification from the original authors. Statistical analysis was performed using the Review Manager (RevMan 2003) software. For dichotomous data, we calculated relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We calculated weighted mean difference and 95% CIs for continuous data.

In the protocol we stated that losses to follow up greater than 25% would be excluded from the analysis. Postpublication, we have changed this to include a sensitivity analysis. This was undertaken on trials excluding those with a loss to follow up of 25% or greater. We tested for heterogeneity between trials using the I2 statistic. Where significant heterogeneity was present (greater than 50%), we used a random‐effects model. No trials reported outcomes by parity and therefore no subgroup analyses by parity were undertaken.

Results

Description of studies

We identified 25 randomised controlled trials that involved complementary and alternative therapies for pain management in labour. Fourteen of these trials (involving 1641 women) met the inclusion criteria for this review and were included, and 11 trials were excluded. No trials on the effects of yoga on pain during childbirth were found.

Included trials

Acupressure

Two trials of acupressure were included in the review (Chung 2003; Lee 2004).

The trial undertaken by Chung 2003 was carried out in Taiwan between May and September 2001. One hundred and twenty‐seven women were randomised to three groups: acupressure, effleurage and a control group. Women had gone into spontaneous labour and were in the first stage of labour. The acupressure intervention was administered by five midwives trained in the technique. The acupressure intervention lasted 20 minutes, consisting of five minute pressure to points LI4 and BL67. Five cycles of acupressure were completed in five minutes, with each cycle comprising 10 seconds of sustained pressure and two seconds of rest without pressure. Outcomes reported included the frequency and intensity of contractions and intensity of labour pain.

Lee 2004 reported on the trial undertaken in Soul, Korea. Eighty‐nine women were randomised to acupressure or touch applied to point Spleen 6 (SP6). The control group received touch without pressure at point SP6. Pressure was applied in the treatment group. For both groups the intervention was administered over 30 minutes during each uterine contraction. Deep breathing and relaxation were also utilised. The trial reported on use of pain relief, anxiety levels, and duration of labour.

Acupuncture

Three randomised controlled trials of acupuncture were included in the review (Nesheim 2003; Ramnero 2002; Skilnand 2002).

Skilnand 2002 randomised 210 women giving birth at a maternity ward in Norway. Women were randomised to receive acupuncture or sham/minimal acupuncture. All women had access to conventional analgesics if insufficient pain relief was provided by the study interventions. A selection of acupuncture points were chosen from 17 points; needles were removed after 20 minutes or taped and retained until birth, or if conventional medication was required. The control group involved minimal acupuncture involving the insertion of needles away from the meridians. The trial reported on pain relief, use of analgesics and use of oxytocin.

A trial of 198 women randomised to receive acupuncture or standard care was undertaken in Norway (Nesheim 2003). The selection of acupuncture points and mode of stimulation was individualised. Outcome measures reported use of analgesics, mode of birth, length of labour and Apgar score.

In the Swedish trial (Ramnero 2002), 100 women were randomised to receive acupuncture or no acupuncture. All women in the trial received routine midwifery care and had access to all conventional analgesia. The acupuncture treatment was individualised. Needles were left in situ between one and three hours. Ninety women were included in the analysis after ten women were excluded due to the inclusion criteria not being met. Outcomes were reported describing pain, relaxation, use of analgesics, augmentation of labour with oxytocin, duration of labour, outcome of birth, antepartum haemorrhage, Apgar scores and infant birthweight.

Aromatherapy

One trial of aromatherapy was included in the review (Calvert 2000). In this New Zealand study, 22 multiparous women with a singleton pregnancy were randomised in a double‐blind trial to receive essential oil of ginger or essential oil of lemongrass in the bath. Women were required to bathe for at least one hour. All women received routine care and had access to pain relief. The trial reported on frequency of contractions, cervical dilatation, length of first and second stage of labour, need for pain relief, side‐effects from essential oils, Apgar scores and direct rooming‐in.

Audio‐analgesia

One trial of audio‐analgesia was included in the review (Moore 1965). The trial undertaken in England, recruited 25 women; 24 women completed the trial. Women were randomised to receive audio‐analgesia which consisted of 'sea noise' white sound set at 120 decibels, or to the control group who received 'sea noise' at a maximum 90 decibels. The intervention began when women were in the first stage of labour. All women received routine care and the midwife offered the woman pain relief if she considered pain relief was inadequate. The trial reported on the midwife's perception of pain relief and the woman's satisfaction with pain relief from 'sea noise'.

Hypnosis

Five randomised controlled trials evaluating the role of hypnosis were included in the review (Freeman 1986; Harmon 1990; Martin 2001; Mehl‐Madrona 2004; Rock 1969).

Freeman 1986 Eighty‐two primigravida women were randomised to self‐hypnosis or a control group at an antenatal clinic in England. The trial examined the effect of hypnosis on the duration of pregnancy and labour, analgesic requirements and mode of birth. Women attended weekly hypnosis sessions from 32 weeks; the control was standard care. Seventeen women (20.7%) were excluded from subsequent analysis by the authors due to pre‐eclampsia (one); breech presentation (three); delivery by caesarean section (nine) and failure to attend hypnosis sessions (four).

Harmon 1990 After determining hypnotic susceptibility, 60 nulliparous women at the end of the second trimester of pregnancy were recruited from an obstetric private practice in the United States. Women were randomised to self‐hypnosis or a control group involving standard relaxation, distraction, and breathing techniques. Treatment was conducted over six one‐hour, weekly sessions. Women participated in groups of 15. The control group listened to their tape at the beginning of each treatment session. These women were asked to concentrate on their breathing exercises, general relaxation, and focal point visualisation. Women in the hypnosis group heard the live hypnotic induction during session one and heard the taped hypnotic induction at the start of sessions two to six. Women rated the type and degree of pain experienced during childbirth, and obstetric outcomes were collected on length of first and second stage of labour, Apgar scores, and use of medication. Psychological assessment involved use of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory Form R antenatally and postnatally within 72 hours of delivery.

Martin 2001 Forty‐seven teenagers with a singleton pregnancy were randomised to self‐hypnosis or the control group involving supportive counseling. The trial took place at the public health department of a teaching hospital in the United States. The four‐session study intervention took place over eight weeks. The trial examined medication use, complications and surgical intervention during delivery, length of hospital stay for mothers, and neonatal intensive care admission for infants.

Mehl‐Madrona 2004 Five hundred and twenty women in the first or second trimester of pregnancy were randomised to hypnosis or supportive psychotherapy. Women were recruited from three states in the USA via referrals from health professionals. Women attended for an average of five hypnosis sessions and one session of supportive psychotherapy. The trial aimed to examine the effect of hypnosis on the emotional state of the woman and birth outcomes including mode of birth, induction and augmentation, neonatal resuscitation, use of pain relief including use of epidural; a measure of depression using the Beck depression Inventory and anxiety using the Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale.

Rock 1969 Forty women were randomised, following admission to the labour ward, to hypnosis or to standard care. Women with no prior training or experience with hypnosis were recruited from the maternity ward at a University Hospital in the USA. The trial examined the use of pain relief during labour, women's views of their experience and postnatal depression.

Massage

Eighty‐three women were recruited from a regional hospital in Taiwan between 1999 and 2000 (Chang 2002). Women were between 37 and 42 weeks' pregnant, with a normal pregnancy, the partner was expected to be present during labour and cervical dilatation was no more than 4 cm. The primary researcher gave the massage during uterine contractions and taught the method to the woman's partner. Women received directional firm rhythmic massage lasting 30 minutes and comprised of effleurage, sacral pressure and shoulder and back kneading. Participants were encouraged to select their preferred technique. The 30‐minute massage was repeated in phase two and in the transitional phase three. The control group received standard nursing care and 30 minutes of the researchers attendance and casual conversation. The outcomes measured pain, anxiety, and an assessment of satisfaction with the childbirth experience.

Relaxation

One trial of relaxation was included (Dolcetta 1979). Fifty‐three women were allocated to respiratory autogenic training or traditional psychoprophylaxis. The trial was undertaken at a University clinic in Italy. The study assessed the effect of relaxation on emotional state during labour, and after childbirth, emotional experience of pain, Apgar score and length of labour.

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation concealment

The trials of acupuncture, aromatherapy and one trial of hypnosis were coded A (Calvert 2000; Nesheim 2003; Ramnero 2002; Skilnand 2002). All the other trials were coded B due to unclear concealment. Rock 1969 was coded C as it uses the last digit of the hospital number and was not concealed.

Method of allocation

The method of allocation was adequately reported in eight trials. Nesheim 2003 used a computer‐generated sequence, the Harmon 1990 trials used random‐number tables. In the Ramnero 2002 trial, card shuffling was reported; the Chung 2003 trial used coin tossing; Skilnand 2002 used lot drawing; and in the Calvert 2000 trial, coded bottles were used. Mehl‐Madrona 2004 used an unspecified random‐number generator. The method of alternation reported by Rock 1969 was inadequate. Chang 2002, Dolcetta 1979, Moore 1965, Freeman 1986, and Martin 2001 state that allocation was random but failed to report the method of allocation.

Blinding

The aromatherapy trial was double blind, including the outcome assessors and analyst (Calvert 2000). Participants were not blind in the Chung 2003, Dolcetta 1979, Mehl‐Madrona 2004, Rock 1969 and Skilnand 2002 trials, but the outcome assessors were blind. For the remaining trials it was impossible for the therapist to be blind. In the Moore 1965 and Freeman 1986 trials, it was unclear whether the woman, outcome assessor or analyst were blind. In the Harmon 1990, Lee 2004 and Martin 2001 trials, the participant, care providers and outcome assessors were blind to their group allocation; the analyst was not blind to the group allocation. In the Ramnero 2002, the outcome assessors and analyst were not blind. There was no blinding in the Chang 2002 and Nesheim 2003 and trials.

Intention‐to‐treat analysis

Five trials reported an intention‐to‐treat analysis (Calvert 2000; Mehl‐Madrona 2004; Nesheim 2003; Ramnero 2002; Rock 1969). It was unclear in one trial whether an intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed (Martin 2001). The remaining trials did not report whether they performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis but an intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed. An intention‐to‐treat analysis was not undertaken in Chung 2003.

Losses to follow up

There were no losses to follow up in the Harmon 1990, Calvert 2000 and Rock 1969 trials.

In the acupressure trial, 23 women withdrew (Chung 2003). In the acupuncture trials one woman dropped out of the acupuncture group and six records were missing in the control group of the Nesheim 2003 trial. Two women were excluded after being randomised due to birth prior to administration of the intervention (Skilnand 2002). In the Ramnero 2002 trial, 10 women (10%) were lost to follow up because they were not eligible after randomisation. Fifteen per cent loss to follow up was reported in Lee 2004.

In the Freeman 1986 hypnosis trial, 13 women withdrew for medical reasons, and four women did not attend for hypnosis (20.7% of the total women). In the Martin 2001 hypnosis trial, five adolescents (11%) were lost to follow up, three moved out of the area and two women, one in each group, did not complete the study protocol. In the audio‐analgesia trial (Moore 1965), one woman (4%) withdrew. Loss to follow up was not reported in the Mehl‐Madrona 2004 trial.

The massage trial (Chung 2003) reported a 27% loss to follow up. The trial of relaxation (Dolcetta 1979) reported a loss to follow up of 27%.

Effects of interventions

Fourteen trials were included in the review with data reporting on 1537 women using different modalities of pain management; 1448 women were included in the meta‐analysis.

Acupressure

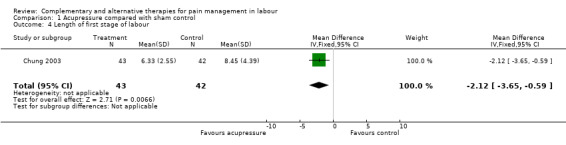

In the Chung 2003 trial, no data were presented on the primary outcomes. Data were presented on one secondary outcome relating to women's perception of pain experienced (97 women). The trial reported on pain during the first stage of labour, latent, active and transitional. No difference between groups in labour pain was found during the transitional and latent phases between groups (no overall measure reported). A difference in the active labour phase was found between the acupressure and control group (weighted mean difference (WMD) ‐2.12, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐3.65 to ‐0.59). Other outcomes included uterine contractions (raw data not provided) and no differences were found between groups.

In Lee 2004 acupressure was compared with a sham control. The trial reported on two primary outcomes (75 women). Women receiving acupressure reported less anxiety compared with women in the control group (75 women) (WMD ‐1.40, 95% CI ‐2.51 to 0.29). There was no difference seen between groups in use of pain relief (relative risk (RR) 0.54, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.43, 75 women). Length of active labour to birth was significantly shorter in the acupressure groups (WMD ‐52.60 minutes, 95% CI 85.77 to ‐19.43).

Acupuncture

Acupuncture versus no treatment

Two trials with 288 women were included for the comparison between acupuncture and no treatment (Nesheim 2003; Ramnero 2002).

Primary outcomes

Maternal satisfaction and maternal experience of labour

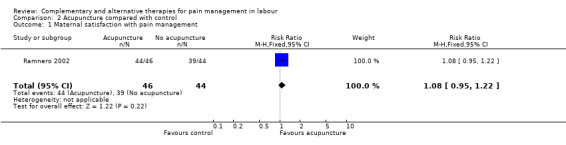

Ramnero 2002 found no difference in maternal satisfaction of pain management between the acupuncture and control group (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.22, 90 women).

Use of pharmacological pain relief in labour

In a meta‐analysis of 288 women, significant heterogeneity was indicated by the I2 statistic and a random‐effects model was applied; use of pharmacological pain relief was greater in the control group (RR 0.70, 95%CI 0.49 to 1.00). Nesheim 2003 reported women in the acupuncture group used less pharmacological pain relief compared to women in the control group (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.96). Ramnero 2002 reported 20 women (43%) who received acupuncture required no additional analgesic compared with 34 women (72%) in the control group (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.81).

Secondary outcomes

Data on instrumental delivery were available from the Nesheim 2003 and Ramnero 2002 trials (288 women). There was no difference in the occurrence of an instrumental delivery between groups (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.45 to 2.00).

Data from Ramnero 2002 reported on 90 women and found no difference in spontaneous vaginal delivery (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.08), caesarean section (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.06 to 14.83), the length of labour (WMD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐1.79 to 1.19) and women's assessment of pain intensity (WMD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.80 to 0.40) between groups. The acupuncture group reported significantly more relaxation than the control group (WMD ‐0.90, 95% CI ‐1.62 to ‐0.18).

Both trials reported on one neonatal outcome, Ramnero found no infants in either group had an Apgar score of less than seven at five minutes, and in the Nesheim 2003 study one infant in the acupuncture group had an Apgar score less than eight at five minutes (RR 2.61, 95% CI 0.11 to 63.24).

Other outcomes (not prespecified) Nesheim 2003 reported on two other outcomes. Women in the treatment group were asked to complete a visual analogue scale (scale not reported); the median pain relief indicated was 5, and 89 women also indicated they would use acupuncture again in another labour.

Acupuncture versus minimal acupuncture

One trial including 208 women evaluated the effect of acupuncture versus minimal acupuncture (Skilnand 2002).

Primary outcome (208 women)

Use of pharmacological pain relief in labour

The need for pharmacological pain relief in labour was reduced for women in the acupuncture group compared with the control (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.88).

Secondary outcomes (208 women) There was a benefit from acupuncture with a reduced need for augmentation (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.69). No difference was found between groups in spontaneous vaginal delivery (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.18), instrumental delivery (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.50), caesarean section (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.17 to 3.15) and Apgar score less than seven at five minutes (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.01 to 7.79). Length of labour is significantly in favour of acupuncture (WMD 71 fewer minutes, 95% CI ‐123.70 to ‐18.30).

Aromatherapy

One trial of 22 women evaluated the role of aromatherapy using ginger compared with lemon grass (Calvert 2000).

Primary outcomes (22 women)

Use of pharmacological pain relief in labour

There was no difference seen between women receiving ginger or lemongrass in their use of pharmacological pain relief (RR 2.50, 95% CI 0.31 to 20.45).

Secondary outcomes (22 women)

There was no benefit from the treatment intervention in relation to the occurrence of spontaneous vaginal delivery (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.28), instrumental vaginal delivery (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.06 to 11.70), or a caesarean section (RR 2.54, 95% CI 0.11 to 56.25). No women in either group had a postpartum haemorrhage. There were no differences between groups on the McGill pain visual analogue scale during the bath (4.9 versus 5.2) or after the bath (6.5 versus 8.5).

No cases of meconium‐stained liquor were reported, no infants had an Apgar score less than seven at five minutes or were admitted to neonatal intensive care.

Audio‐analgesia

Primary outcome

Only one outcome on maternal satisfaction relevant for inclusion in the meta‐analysis was reported from this trial of 25 women (Moore 1965). No difference was found between groups (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.82 to 4.89 (24 women)).

Hypnosis

Five studies comparing the use of hypnosis with a control group in 749 women were included in the review (Freeman 1986; Harmon 1990; Martin 2001; Mehl‐Madrona 2004; Rock 1969).

Primary outcomes

Maternal satisfaction and maternal experience of labour

One trial reported on maternal satisfaction with pain relief (65 women) (Freeman 1986). Women in the hypnosis group reported greater satisfaction than those in the control group (RR 2.33, 95% CI 1.15 to 4.71 (125 women)). In the Rock 1969 trial, women reported their experience as less painful (P < 0.01) although no data were presented. In addition, no women reported postnatal depression during their follow‐up visit. In the Mehl‐Madrona 2004 trial, anxiety and depression scale data were presented according to whether the birth was complicated or uncomplicated as defined by the author. The Harmon 1990 trial found no overall difference in measures of depression using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory between women in the hypnosis and control groups (WMD‐2.7, 95% CI ‐7.82 to 2.42).

Need for pain relief

The I2 statistic indicated significant heterogeneity; using a random‐effects model, the meta‐analysis for the five trials reporting on this outcome showed a decreased need for pharmacological pain relief in women allocated to the hypnosis groups compared to the control groups (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.79 (727 women)).

All five trials reported on the use of pharmacological pain relief in labour. In the Freeman 1986, there was no difference in the use of pain relief between women receiving hypnosis and the control group (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.40 to 2.82, (65 women)), although women rated to have a good or moderate response to hypnosis had relatively fewer epidurals than those rated to have a poor responsive (4/24 versus 4/5, P < 0.05). In the Martin 2001 trial, women receiving hypnosis used less anaesthesia than women in the control group (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.11 (42 women)). Harmon 1990 reported on the use of narcotics; fewer women in the hypnosis group used narcotics than in the control group (RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.55, (60 women)). Mehl‐Madrona 2004 reported women receiving hypnosis required less pharmacological pain relief (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.52) and less use of epidural analgesia (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.40 (520 women). In the Rock 1969 trial, there was a reduced incidence in the use of pain relief in those women allocated to the hypnosis intervention when compared with the control (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.94).

Secondary outcomes

The three trials reporting on mode of delivery (Freeman 1986; Harmon 1990; Mehl‐Madrona 2004) found more women had a spontaneous vaginal birth in the hypnosis group than in the control group (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.46 (645 women)). Mehl‐Madrona 2004 reported on women requiring caesarean section and found a significant lower rate in the hypnosis group (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.72 (520 women)).

Two trials reported on the use of augmentation with oxytocin (Harmon 1990; Martin 2001) and one trial combined augmentation with induction in the trial report. On contacting the author, additional information regarding these outcomes has been provided (Mehl‐Madrona 2004). Women in the hypnosis groups used less oxytocin than women in the control groups (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.45 (622 women)) and women are reported by Mehl‐Madrona 2004 as less likely to require an induction of labour with hypnosis preparation for childbirth versus control (RR 0.34 95% CI 0.18 to 0.65 (520 women)).

Freeman 1986 reported a longer mean duration of labour in the hypnosis group than in the control group (12.4 versus 9.7 hours, P < 0.05) while Harmon 1990 found the duration of the first stage of labour in the hypnosis group to be significantly shorter (P < 0.001) than the control group by over two hours. This was the only study that defined the duration of labour (as time from 5 cm to full dilatation).

Limited neonatal outcomes were reported in three trials. There was no difference between groups in admission to neonatal intensive care (RR 0.18, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.43 (42 babies)) (Martin 2001). Apgar scores at five minutes were reported by Harmon 1990; mean score for the hypnosis group was 9.30 (standard deviation (SD) 0.65) and the control group was 8.7 (SD 0.50). There was no difference seen in neonatal resuscitation between groups in the Mehl‐Madrona 2004 trial (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.11 to 3.96).

Massage

Secondary outcomes

There was a significant reduction in women's perception of pain for the massage group compared to the control group during all three phases of labour (phase one ‐0.57, 95% CI ‐0.84 to ‐0.29, P < 0.001; phase two ‐0.43, 95% CI ‐0.71 to 0.16, P < 0.01; phase three ‐0.7, 95% CI ‐1.04 to 0.36, P < 0.01) (Chang 2002). There was a difference in women's anxiety in the first phase of labour, with women in the massage group reporting less anxiety (‐16.27, 95% CI ‐27.25 to ‐5.28, P < 0.05). No difference in the duration of labour was found (WMD 1.35, 95% CI ‐0.98 to 3.68) and satisfaction with general birth experience (WMD ‐0.47, 95% CI ‐1.07 to 0.13).

Relaxation

There was no difference between groups in women's experience of pain (WMD ‐1.90, 95% CI ‐3.88 to 0.08), instrumental delivery (RR 0.16, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.68), augmentation with oxytocin (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.59) and Apgar scores (RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.02 to 10.69) (Dolcetta 1979).

A sensitivity analysis of trials with losses to follow up of greater than or equal to 25% was planned but not undertaken as meta‐analyses were not undertaken on these trials.

Discussion

Despite the increasing use of complementary therapies there is a lack of well‐designed randomised controlled trials to evaluate the effectiveness of many of these therapies for pain management in labour. Few complementary therapies have been subjected to rigorous scientific study and, with the exception of acupuncture and hypnosis, the number of women studied in this setting is small. Most trials were small and of poor methodological quality or inadequately reported. The insufficient reporting made the assessment of methodological quality and data extraction difficult. The heterogeneity reported for the hypnosis and acupuncture trials may be explained by variation in the design of the treatment interventions including techniques and the duration of the intervention. Overall, the clinical implications of the studies are limited by the inclusion of few clinical outcomes.

Acupressure

There is insufficient evidence about the effectiveness of acupressure on pain management and further research is required.

Acupuncture

Evidence from the three trials included in the review (Nesheim 2003; Ramnero 2002; Skilnand 2002) suggest women receiving acupuncture required less analgesia, including the need for epidural analgesic. The results also suggest a reduced need for augmentation with oxytocin. Further research is required. Appropriately powered randomised trials are required to examine the effectiveness of acupuncture on the clinical outcomes described in this review.

The three trials of acupuncture represent different approaches to the use of acupuncture to manage pain during labour. In addition to the style of acupuncture used, acupuncture can vary in the selection of acupuncture points and the needling techniques used (duration of needling, number of points used, depth of needling, type of stimulation and point selection). It is important that any future clinical trials of acupuncture for pain management in labour report the basis for the acupuncture treatment and needling as described in the STRICTA guideline (MacPherson 2001).

Aromatherapy

There is insufficient evidence about the effectiveness of aromatherapy on pain management in labour on any primary or secondary outcome from one small controlled trial comparing lemongrass and ginger. A methodological issue for trials of aromatherapy is the choice of an appropriate control group to ensure participants and care providers remain unaware of the group allocation and the use of a control group enabling meaningful comparisons to be made. Adequately powered studies are needed to examine the effects of aromatherapy on pain management in labour.

Audio‐analgesia

There is insufficient evidence about the effectiveness of audio analgesia on pain management in labour. Further research is required.

Hypnosis

Current available evidence shows that hypnosis reduces the need for pharmacological pain relief, including epidural analgesia in labour. Maternal satisfaction with pain management in labour may be greater among women using hypnosis. Other promising benefits from hypnosis appear to be an increased incidence of vaginal birth, and a reduced use of oxytocin augmentation. There was no evidence of any adverse effects on the mother or neonate. Potentially, medical hypnosis could be used alone for pain relief as part of a woman's care during childbirth. In practice, however, hypnosis may be best seen as an adjunct to facilitate and enhance other analgesics.

Overall, currently available data suggest that hypnosis is effective as an adjunctive analgesic during labour and is associated with a decreased use of oxytocic augmentation and an increased likelihood of spontaneous vaginal birth. Acupuncture also appears beneficial in the provision of pain management during labour.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The data available suggest hypnosis reduces the need for pharmacological pain relief in labour, reduces the requirements for drugs to augment labour; and increases the incidence of spontaneous vaginal birth. Acupuncture may be a helpful therapy for pain management in labour. The efficacy of acupressure, aromatherapy, audio‐analgesia, relaxation and massage have not been established.

Implications for research.

Further randomised controlled trials of complementary therapies for pain management in labour are needed. Further randomised trials should be adequately powered and include clinically relevant outcomes such as those described in this review. There is a need for improving the quality and reporting of future trials. In particular, consideration should be given in the analysis and reporting on the person providing the intervention, for example, their training, length of experience and relationship to the woman. In addition, further research is required which include data measuring neonatal outcomes and the effects on analgesia requirements in institutions with and without an 'on demand' epidural service. A cost‐benefit analysis should be incorporated into the design of future studies.

Investigation is required of the timing and specific aspects of hypnosis delivery such as: group versus individual training in hypnosis; use of an audio tape or compact disc on hypnosis versus live hypnosis; longer‐term follow up for postnatal depression (at least four months) and anxiety; the relative effects of hypnosis administered before and after the third trimester. The design of future acupuncture trials should consider the consensus recommendations for optimal treatment, sham controls and blinding (MacPherson 2001). In addition, combinations of the beneficial therapies (acupuncture and hypnosis) should be considered for further study.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13 July 2010 | Amended | Added Published notes about the updating of this review. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2002 Review first published: Issue 2, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 28 February 2006 | New search has been performed | Ten new trials identified: six trials were included in the review, including two trials of hypnosis, two acupressure trials and two acupuncture trials. Four trials were excluded. We have removed trials of biofeedback from this update because they will be reviewed separately in the review following the newly published protocol 'Biofeedback for pain during labour'. Trials with a loss greater than 25% were not excluded from the analysis. A sensitivity analysis was undertaken on trials with a loss to follow up of 25% or greater. |

Notes

This review is being split into three new reviews: 'Acupuncture or acupressure for relieving pain in labour'; 'Aromatherapy for relieving pain in labour'; and 'Relaxation techniques for relieving pain in labour'. When the new reviews are published, this review will be withdrawn from publication.

Acknowledgements

Philippa Middleton for her helpful comments on the draft review.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Acupressure compared with sham control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Decreased maternal anxiety | 1 | 75 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.40 [‐2.51, ‐0.29] |

| 2 Use of pharmacological analgesia | 1 | 75 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.20, 1.43] |

| 3 Length of labour | 1 | 75 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐52.60 [‐85.77, ‐19.43] |

| 4 Length of first stage of labour | 1 | 85 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.12 [‐3.65, ‐0.59] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupressure compared with sham control, Outcome 1 Decreased maternal anxiety.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupressure compared with sham control, Outcome 2 Use of pharmacological analgesia.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupressure compared with sham control, Outcome 3 Length of labour.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupressure compared with sham control, Outcome 4 Length of first stage of labour.

Comparison 2. Acupuncture compared with control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Maternal satisfaction with pain management | 1 | 90 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.95, 1.22] |

| 2 Use of pharmacological analgesia | 2 | 288 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.49, 1.00] |

| 3 Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 1 | 90 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.89, 1.08] |

| 4 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 288 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.45, 2.00] |

| 5 Caesarean section | 1 | 90 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.06, 14.83] |

| 6 Length of labour | 1 | 90 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.30 [‐1.79, 1.19] |

| 7 Augmentation with oxytocin | 1 | 90 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.58, 1.80] |

| 8 Pain intensity | 1 | 90 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.20 [‐0.80, 0.40] |

| 9 Relaxation | 1 | 90 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.90 [‐1.62, ‐0.18] |

| 10 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 288 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.61 [0.11, 63.24] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture compared with control, Outcome 1 Maternal satisfaction with pain management.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture compared with control, Outcome 2 Use of pharmacological analgesia.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture compared with control, Outcome 3 Spontaneous vaginal delivery.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture compared with control, Outcome 4 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture compared with control, Outcome 5 Caesarean section.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture compared with control, Outcome 6 Length of labour.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture compared with control, Outcome 7 Augmentation with oxytocin.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture compared with control, Outcome 8 Pain intensity.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture compared with control, Outcome 9 Relaxation.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture compared with control, Outcome 10 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

Comparison 3. Acupuncture compared with minimal acupuncture.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Use of pharmacological analgesia | 1 | 208 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.58, 0.88] |

| 2 Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 1 | 208 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.96, 1.18] |

| 3 Instrumental delivery | 1 | 208 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.27, 1.50] |

| 4 Augmentation with oxytocin | 1 | 208 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.23, 0.69] |

| 5 Length of labour | 1 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐71.0 [‐123.70, ‐18.30] |

| 6 Caesarean section | 1 | 208 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.17, 3.15] |

| 7 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 208 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.01, 7.79] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acupuncture compared with minimal acupuncture, Outcome 1 Use of pharmacological analgesia.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acupuncture compared with minimal acupuncture, Outcome 2 Spontaneous vaginal delivery.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acupuncture compared with minimal acupuncture, Outcome 3 Instrumental delivery.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acupuncture compared with minimal acupuncture, Outcome 4 Augmentation with oxytocin.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acupuncture compared with minimal acupuncture, Outcome 5 Length of labour.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acupuncture compared with minimal acupuncture, Outcome 6 Caesarean section.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acupuncture compared with minimal acupuncture, Outcome 7 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

Comparison 4. Aromatherapy compared with control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Use of pharmacological analgesia | 1 | 22 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.5 [0.31, 20.45] |

| 2 Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 1 | 22 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.67, 1.28] |

| 3 Instrumental delivery | 1 | 22 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.06, 11.70] |

| 4 Caesarean section | 1 | 22 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.54 [0.11, 56.25] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Aromatherapy compared with control, Outcome 1 Use of pharmacological analgesia.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Aromatherapy compared with control, Outcome 2 Spontaneous vaginal delivery.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Aromatherapy compared with control, Outcome 3 Instrumental delivery.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Aromatherapy compared with control, Outcome 4 Caesarean section.

Comparison 5. Audio‐analgesia compared with control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Maternal satisfaction with pain relief from 'sea noise' | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.82, 4.89] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Audio‐analgesia compared with control, Outcome 1 Maternal satisfaction with pain relief from 'sea noise'.

Comparison 6. Hypnosis compared with control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Use of pharmacological analgesia | 5 | 727 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.36, 0.79] |

| 2 Use of epidural | 1 | 520 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.22, 0.40] |

| 3 Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 3 | 645 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [1.19, 1.46] |

| 4 Augmentation with oxytocin | 3 | 622 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.19, 0.45] |

| 5 Induction of labour | 1 | 520 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.18, 0.65] |

| 6 Caesarean section | 1 | 520 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.30, 0.72] |

| 7 Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory depression scale | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.70 [‐7.82, 2.42] |

| 8 Newborn resuscitations | 1 | 520 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.11, 3.96] |

| 9 Admission to neonatal intensive care unit | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.18 [0.02, 1.43] |

| 10 Maternal satisfaction with pain management from hypnosis | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.33 [1.15, 4.71] |

| 11 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.32, 0.88] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Hypnosis compared with control, Outcome 1 Use of pharmacological analgesia.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Hypnosis compared with control, Outcome 2 Use of epidural.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Hypnosis compared with control, Outcome 3 Spontaneous vaginal delivery.

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Hypnosis compared with control, Outcome 4 Augmentation with oxytocin.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Hypnosis compared with control, Outcome 5 Induction of labour.

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Hypnosis compared with control, Outcome 6 Caesarean section.

6.7. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Hypnosis compared with control, Outcome 7 Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory depression scale.

6.8. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Hypnosis compared with control, Outcome 8 Newborn resuscitations.

6.9. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Hypnosis compared with control, Outcome 9 Admission to neonatal intensive care unit.

6.10. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Hypnosis compared with control, Outcome 10 Maternal satisfaction with pain management from hypnosis.

6.11. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Hypnosis compared with control, Outcome 11 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

Comparison 7. Massage compared with control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Length of labour | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.35 [‐0.98, 3.68] |

| 2 Satisfaction with birth | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.47 [‐1.07, 0.13] |

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Massage compared with control, Outcome 1 Length of labour.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Massage compared with control, Outcome 2 Satisfaction with birth.

Comparison 8. Relaxation.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Maternal perception of pain | 1 | 34 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.90 [‐3.88, 0.08] |

| 2 Augmentation with oxytocin | 1 | 34 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.82, 1.59] |

| 3 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 34 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.16 [0.01, 2.68] |

| 4 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 34 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.47 [0.02, 10.69] |

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Relaxation, Outcome 1 Maternal perception of pain.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Relaxation, Outcome 2 Augmentation with oxytocin.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Relaxation, Outcome 3 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Relaxation, Outcome 4 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Calvert 2000.

| Methods | Double‐blind, randomised controlled trial of aromatherapy. Computer‐generated sequence and concealed by a coded number on the bottle. The women, care providers, outcome assessor and analyst were all blind to the woman's group allocation. | |

| Participants | 22 multiparous women with a singleton pregnancy were randomised to the trial. Women were excluded with previous caesarean section, major medical complications, skin allergies, hypotension, previous vaginal surgery (excluding dilatation and curettage), not receiving continuity of midwifery care. Women were recruited during the antenatal period, at a level II hospital in New Zealand. | |

| Interventions | Randomisation occurred on the delivery suite prior to the woman entering the bath. Once the woman was in the bath, the seal on the bottle was broken and the oil poured into the bath. The woman was required to remain in the bath for at least one hour. The experimental group received essential oil of ginger and the control group received essential oil of lemon grass. | |

| Outcomes | Frequency of contractions, cervical dilatation, length of first and second stage of labour, pain experience, need for pain relief, side‐effects from essential oils, Apgar scores, and rooming‐in. | |

| Notes | A power calculation was performed, 116 women were required. Twenty‐two women were recruited. There were no losses to follow up. An intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Chang 2002.

| Methods | Single‐blind, randomised controlled trial of massage versus no treatment. Randomisation was alternate. | |

| Participants | 83 women were recruited from a regional hospital in Taiwan between 1999‐2000. Women were between 37 and 42 weeks' pregnant, with a normal pregnancy, the partner was expected to be present during labour and cervical dilatation was no more than 4 cm. | |

| Interventions | The primary researcher gave the massage during uterine contractions and taught the method to the woman's partner. Women received directional firm rhythmic massage lasting 30 minutes and comprised of effleurage, sacral pressure and shoulder and back kneading. Women were encouraged to selected their preferred technique. The 30‐minute massage was repeated in phase 2 and in the transitional phase 3. The control group received standard nursing care and 30 minutes of the researchers attendance and casual conversation. | |

| Outcomes | Behavioural intensity scale of pain measured by the nurse. VAS for anxiety. Subjective assessment of satisfaction with the childbirth experience. | |

| Notes | A power analysis was reported. Twenty‐three women (27%) were lost to follow up. An intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Chung 2003.

| Methods | Single‐blind, randomised controlled trial of acupressure, effleurage and a control group. The randomisation allocation sequence was by coin tossing, participants were sequentially numbered but the allocation sequence was unclear. It was not feasible for the participant and therapist to be blind to their group allocation. The outcome assessors were blind to women's group allocation but unclear for analyst. | |

| Participants | 127 women participated in the trial, during their first stage of labour. Participants needed to be between 37 and 42 weeks' pregnant, a low‐risk pregnancy, singleton pregnancy and able to speak Chinese. Women who were induced with oxytocin, or received an epidural block or who planned a caesarean section were excluded from the study. The trial was undertaken in Taiwan, no other details were reported. | |

| Interventions | Trained midwives administered the acupressure to women. The intervention lasted 20 minutes, consisting of 5 minutes pressure to points LI4 and BL67. Five cycles of acupressure were completed in 5 minutes, with each cycle comprising 10 seconds of sustained pressure and 2 seconds of rest without pressure. A protocol was established to control finger pressure, accuracy of points and accuracy of technique. For the effleurage group, the left and right upper arms were massaged for 10 minutes. In the control group, the midwife stayed with the participant for 20 minutes, taking notes or talking with the participant or family members. | |

| Outcomes | A VAS scale was used to measure the intensity of labour pain. This was administered before and after the intervention. Qualitative data were also collected on women's experience of labour pain 1‐2 hours after delivery. The frequency and intensity of uterine contractions were measured from electronic fetal monitors. | |

| Notes | There was no power analysis. Twenty‐three (18%) women withdrew from the study due to a need for a caesarean section, pain medication. An intention‐to‐treat analysis was not performed. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dolcetta 1979.

| Methods | A controlled partial double‐blind trial of RAT versus traditional psychoprophylaxis method. Randomisation was used but no details provided. The outcome analyst was blind to group allocation. | |

| Participants | 53 women were randomly assigned to their study group. Women were aged 20‐35 years, participated in no less than 5 sessions, no physical abnormalities, obstetric score less than 30. The study was undertaken at a University Clinic in Verona, Italy. | |

| Interventions | RAT consists of the women learning to auto‐induce an autogenous state and to reduce her muscle tone by deep relaxation. No details provided on the control group. | |

| Outcomes | Emotional state during labour and after childbirth, pain, pain experience, Apgar score, length of labour. | |

| Notes | There was no power analysis. Data available on 34 women. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Freeman 1986.

| Methods | Single‐blind, randomised controlled trial. The allocation sequence was not stated and no details were reported on blinding or concealment. | |

| Participants | 82 primiparous women, with a normal pregnancy and who wished to avoid an epidural. Women were recruited from an antenatal clinic in England. | |

| Interventions | Women were seen individually on a weekly basis from 32 weeks. Women were encouraged to imagine warmth in one hand and shown how to transfer this to the abdomen. The control group received standard antenatal care. | |

| Outcomes | Duration of pregnancy, duration of labour, analgesic requirements and mode of delivery. | |

| Notes | Thirteen (15%) women were excluded due to obstetric complications and four women failed to attend hypnosis. No power calculation and no baseline characteristics presented. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Harmon 1990.

| Methods | Single‐blind, randomised controlled trial. The allocation sequence used random‐number tables. The allocation sequence was not concealed. The outcome assessor and analyst were not blind to the woman's group allocation. | |

| Participants | 60 nulliparous women aged 18‐35 years, at the end of the second trimester, referred from an obstetric private practice in the United States. Women with a history of psychiatric hospitalisation, depression during pregnancy, obstetric risk, or with borderline hypertension were excluded. | |

| Interventions | Women receiving hypnosis were given a cassette tape recording of the hypnotic induction. The control group were given a cassette tape recording of 'Practice for Childbirth'. All women were told to practice their tapes daily. | |

| Outcomes | Use of medication in labour, length of labour, mode of delivery, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes. | |

| Notes | Data on outcomes were complete. There was no power calculation. No baseline characteristics were reported. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lee 2004.

| Methods | Single‐blind, randomised controlled trial of acupressure or touch control. The randomisation sequence was generated from random‐number tables, the allocation concealment sequence was open. The participants and outcome assessors were blind to group allocation. | |

| Participants | 89 women were randomly allocated to the trial. Inclusion criteria for the study were: greater than 37 weeks pregnant, singleton pregnancy, planning a vaginal delivery and in good health. Women were recruited to the study from publicity materials in the outpatient department of a general hospital in Korea. | |

| Interventions | Women allocated to the intervention group received acupressure at SP6, or to the control group touch at SP6. The acupressure involved pressure at SP6 on both legs during a contraction during a 30‐minute time period during each contraction. The pressure applied was 2150 mmHg. The control group received touch with no pressure from the thumbs. | |

| Outcomes | Pain was measured along a VAS and assessed at entry, before the intervention was administered, after the intervention, and 30 and 60 minutes after the intervention. Other outcomes included duration of labour, use of pain relief, and maternal anxiety. | |

| Notes | No power analysis was reported. Fourteen (15%) women did not complete the study. An intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Martin 2001.

| Methods | Single‐blind, randomised‐controlled trial of hypnosis. The allocation sequence was not stated. No details were provided on concealment of the allocation sequence or blinding. | |

| Participants | 47 teenagers, 18 years or younger, with a normal pregnancy before their 24th week of pregnancy. Teenagers were recruited at a public hospital in Florida, USA. | |

| Interventions | Treatment group received childbirth preparation in self‐hypnosis that included information on labour and delivery. The control group received supportive counseling. The study intervention began with individual meetings during regular clinic visits between 20‐24 weeks. Continuing clinic visits were scheduled on a biweekly basis, with the intervention run over 8 weeks. | |

| Outcomes | Medication use, complications, surgical intervention during delivery, length of hospital stay for mothers and neonatal intensive care admissions for infants. | |

| Notes | Five teenagers were lost to follow up (10%). There was no power calculation. No details on the baseline characteristics were provided. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Mehl‐Madrona 2004.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial of hypnosis compared to supportive psychotherapy. The allocation sequence was not stated and random numbers were generated by a random‐number generator. Participants were not blind but the outcome assessors were blind. Loss to follow up was not stated. | |

| Participants | 520 women in the first or second trimester of pregnancy were recruited to the study in the USA. Women were excluded if they were in the third trimester of pregnancy, had an anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder and other specified psychiatric disorders. | |

| Interventions | Hypnosis (Cheek method) involving problem solving, brief psychoanalytical‐based psychotherapy. Participants attended five sessions. The control group received supportive psychotherapy. | |

| Outcomes | Need for augmentation, caesarean section, newborn resuscitation, epidural anaesthesia, use of analgesia and maternal emotional experience during birthing. | |

| Notes | An intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Moore 1965.

| Methods | Single‐blind, randomised controlled trial of audio‐analgesia. The allocation sequence and concealment of the allocation sequence was unclear. It was unclear whether the outcome assessor and analyst were blind. | |

| Participants | 25 women with a singleton pregnancy in the first stage of labour were randomised to the trial. The trial was undertaken in England. Women were excluded if they had a history of ear disease or vestibular disturbance. | |

| Interventions | Women in the experimental arm listened to white sound set at 120 decibels. Control cases listened to white sound at a maximum 90 decibels (it was presumed at this level there is no physiological effect). The intervention started when the woman was in established labour. If the women became tired the audio‐analgesia was stopped and resumed later. If the midwife considered the pain relief inadequate, the audio analgesia was stopped and inhalation analgesia started. | |

| Outcomes | Midwife's opinion of pain relief from audio‐analgesia, woman's satisfaction with 'sea noise'. | |

| Notes | One (4%) woman withdrew from the trial. There was no sample‐size calculation. No details were provided on baseline characteristics. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Nesheim 2003.

| Methods | A single‐blind, controlled trial of acupuncture versus standard care. The allocation sequence was computer‐generated and was concealed in opaque envelopes that were numbered consecutively. Participants and the therapist were not blind. | |

| Participants | 198 women were enrolled into the trial of acupuncture versus standard care. Women were recruited to the trial who were at term, experiencing regular contractions and had an ability to speak Norwegian. Women were excluded if their labour was induced, planning a caesarean section, a plan to request an epidural block, medical reasons for an epidural, or experiencing any infectious diseases. | |

| Interventions | 8 midwives were educated and trained to practice acupuncture for the trial. All women received other analgesics on demand. The acupuncture points used were selected based on the participants' needs and included points BL32, GV20, BL60, BL62, HT7, LR3, GB34, CV4, LI10, LI11, BL23, BL27, 28, 32, LI4, SP6, PC6,7, ST36. De qi was obtained. Needles were left in place for 10‐20 minutes, or removed after the needling sensation was obtained, or taped and left in place. Women in the control group received conventional care. | |

| Outcomes | Clinical outcomes included use of meperidine, use of other analgesics, duration of labour, mode of delivery and Apgar score. Participants also rated their pain relief along a VAS scale and asked to report any side‐effects from the treatment. | |

| Notes | A power analysis was undertaken. There was one drop out in the acupuncture group, and 6 missing records. An intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Ramnero 2002.

| Methods | Parallel single‐blind, randomised controlled trial of acupuncture. The trial was stratified by parity. Women received acupuncture or no acupuncture. The randomisation sequence used shuffled cards and were concealed in sealed, opaque envelopes. The outcome assessor was not blind and it was unclear if the analyst was blind to treatment allocation. | |