Abstract

Background

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is characterised by partial or complete upper airway obstruction during sleep. Approximately 1% to 4% of children are affected by OSA, with adenotonsillar hypertrophy being the most common underlying risk factor. Surgical removal of enlarged adenoids or tonsils is the currently recommended first‐line treatment for OSA due to adenotonsillar hypertrophy. Given the perioperative risk and an estimated recurrence rate of up to 20% following surgery, there has recently been an increased interest in less invasive alternatives to adenotonsillectomy. As the enlarged adenoids and tonsils consist of hypertrophied lymphoid tissue, anti‐inflammatory drugs have been proposed as a potential non‐surgical treatment option in children with OSA.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of anti‐inflammatory drugs for the treatment of OSA in children.

Search methods

We identified trials from searches of the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register, CENTRAL and MEDLINE (1950 to 2019). For identification of ongoing clinical trials, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization (WHO) trials portal.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing anti‐inflammatory drugs against placebo in children between one and 16 years with objectively diagnosed OSA (apnoea/hypopnoea index (AHI) ≥ 1 per hour).

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently performed screening, data extraction, and quality assessment. We separately pooled results for the comparisons 'intranasal steroids' and 'montelukast' against placebo using random‐effects models. The primary outcomes for this review were AHI and serious adverse events. Secondary outcomes included the respiratory disturbance index, desaturation index, respiratory arousal index, nadir arterial oxygen saturation, mean arterial oxygen saturation, avoidance of surgical treatment for OSA, clinical symptom score, tonsillar size, and adverse events.

Main results

We included five trials with a total of 240 children aged one to 18 years with mild to moderate OSA (AHI 1 to 30 per hour). All trials were performed in specialised sleep medicine clinics at tertiary care centres. Follow‐up time ranged from six weeks to four months.

Three RCTs (n = 137) compared intranasal steroids against placebo; two RCTs compared oral montelukast against placebo (n = 103). We excluded one trial from the meta‐analysis since the patients were not analysed as randomised. We also had concerns about selective reporting in another trial.

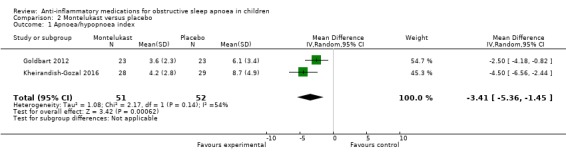

We are uncertain about the difference in AHI (MD −3.18, 95% CI −8.70 to 2.35) between children receiving intranasal corticosteroids compared to placebo (2 studies, 75 participants; low‐certainty evidence). In contrast, children receiving oral montelukast had a lower AHI (MD −3.41, 95% CI −5.36 to −1.45) compared to those in the placebo group (2 studies, 103 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence).

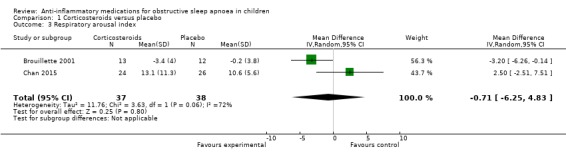

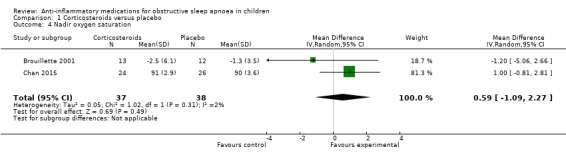

We are uncertain whether the secondary outcomes are different between children receiving intranasal corticosteroids compared to placebo: desaturation index (MD −2.12, 95% CI −4.27 to 0.04; 2 studies, 75 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence), respiratory arousal index (MD −0.71, 95% CI −6.25 to 4.83; 2 studies, 75 participants; low‐certainty evidence), and nadir oxygen saturation (MD 0.59%, 95% CI −1.09 to 2.27; 2 studies, 75 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence).

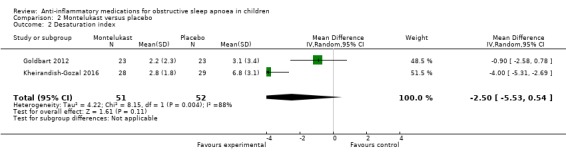

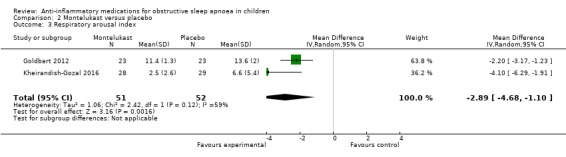

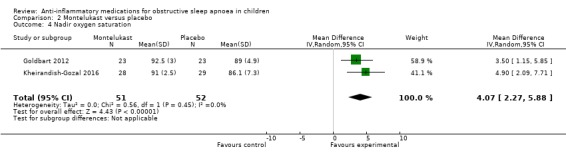

Children receiving oral montelukast had a lower respiratory arousal index (MD −2.89, 95% CI −4.68 to −1.10; 2 studies, 103 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence) and nadir of oxygen saturation (MD 4.07, 95% CI 2.27 to 5.88; 2 studies, 103 participants; high‐certainty evidence) compared to those in the placebo group. We are uncertain, however, about the difference in desaturation index (MD −2.50, 95% CI −5.53 to 0.54; 2 studies, 103 participants; low‐certainty evidence) between the montelukast and placebo group.

Adverse events were assessed and reported in all trials and were rare, of minor nature (e.g. nasal bleeding), and evenly distributed between study groups.

No study examined the avoidance of surgical treatment for OSA as an outcome.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence for the efficacy of intranasal corticosteroids for the treatment of OSA in children; they may have short‐term beneficial effects on the desaturation index and oxygen saturation in children with mild to moderate OSA but the certainty of the benefit on the primary outcome AHI, as well as the respiratory arousal index, was low due to imprecision of the estimates and heterogeneity between studies.

Montelukast has short‐term beneficial treatment effects for OSA in otherwise healthy, non‐obese, surgically untreated children (moderate certainty for primary outcome and moderate and high certainty, respectively, for two secondary outcomes) by significantly reducing the number of apnoeas, hypopnoeas, and respiratory arousals during sleep. In addition, montelukast was well tolerated in the children studied. The clinical relevance of the observed treatment effects remains unclear, however, because minimal clinically important differences are not yet established for polysomnography‐based outcomes in children.

Long‐term efficacy and safety data on the use of anti‐inflammatory medications for the treatment of OSA in childhood are still not available. In addition, patient‐centred outcomes like concentration ability, vigilance, or school performance have not been investigated yet.

There are currently no RCTs on the use of other kinds of anti‐inflammatory medications for the treatment of OSA in children.

Future RCTs should investigate sustainability of treatment effects, avoidance of surgical treatment for OSA, and long‐term safety of anti‐inflammatory medications for the treatment of OSA in children and include patient‐centred outcomes.

Plain language summary

Anti‐inflammatory medications for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea in children

Background

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is the partial or complete blockage of the upper airways during sleep. It affects about 1% to 4% of children. The most common underlying reason for OSA in childhood are enlarged adenoids or tonsils. The currently recommended treatment is surgical removal of the adenoids and tonsils. Treatment with anti‐inflammatory medications is an alternative, non‐surgical treatment in milder cases of OSA.

Review question

The aim of this review was to evaluate the evidence on the benefits and safety of anti‐inflammatory medications for the treatment of OSA in children between one and 16 years of age. The primary outcomes of the review were the number of breathing pauses and episodes of shallow breathing per hour of sleep (apnoea/hypopnoea index, AHI) and serious unintended effects of the medication.

Study characteristics

We included five studies in the review. These studies each included 25 to 62 children between one and 11 years of age with mild to moderate OSA treated at specialised sleep outpatient clinics. The included studies used two different types of anti‐inflammatory medications. Seventy‐five children were randomised to receive either intranasal corticosteroid nasal spray or placebo. One hundred and three children were randomised to either montelukast tablet or placebo.

Study funding sources

Three studies were supported by drug manufacturers.

Key results

We are uncertain about the difference in the number of breathing pauses, episodes of shallow breathing, episodes with a lack of blood oxygen, or sleep disruption between children receiving corticosteroid nasal spray compared to placebo (2 studies involving 75 children).

Children receiving montelukast tablets had fewer breathing pauses, fewer episodes of shallow breathing, and less sleep disruption compared to those treated with placebo (2 studies involving 103 children). However, we are uncertain about the difference in the number of episodes with a lack of blood oxygen between the montelukast and placebo group.

Unintended effects were assessed in all trials, but were rare and of minor nature (e.g. nosebleeds). Serious unintended effects were not reported.

Certainty of the evidence

The certainty of the evidence for corticosteroid nasal spray for the treatment of OSA was low for the primary outcome due to the wide range of the beneficial effect with some inconsistency of the effect between the two included studies. We excluded one study from the analysis due to serious concerns about the quality of the study results.

The evidence for the use of montelukast tablets in the treatment of OSA was of moderate certainty for the primary outcome. There were concerns about the design and conduct of one study and some inconsistency of the effect between the two included studies.

The evidence is current to October 2019.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Sleep‐disordered breathing is one of the most common sleep disorders in childhood. Affected children may exhibit habitual snoring, laboured breathing, sleep disruption, and/or gas exchange abnormalities. The most severe form of sleep‐disordered breathing, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), is defined as a “disorder of breathing during sleep characterised by prolonged partial upper airway obstruction and/or intermittent complete obstruction (obstructive apnoea) that disrupts normal ventilation during sleep and normal sleep patterns, accompanied by symptoms or signs” (AAP 2012).

Approximately 1% to 6% of children are affected by OSA (Lumeng 2008; AAP 2012). Symptoms include habitual snoring, laboured breathing, witnessed apnoea, disturbed sleep, daytime neurobehavioral problems, and sleepiness (AASM 2006; AAP 2012). The most common underlying risk factor for the development of OSA is adenotonsillar hyperplasia (Marcus 2001; AAP 2012). The relative enlargement of the tonsils during the pre‐school years reduces pharyngeal space and promotes airway collapse during sleep, resulting in OSA (Marcus 2001). Other risk factors include male sex, overweight and obesity, prematurity, African American ethnicity, craniofacial anomalies, and neuromuscular disorders (Rosen 2003; Lumeng 2008; AAP 2012).

A child with suspected OSA should either undergo polysomnography or be referred to a sleep medicine specialist or otolaryngologist for a more extensive evaluation (AAP 2012). A definitive diagnosis of OSA is made by attended overnight polysomnography in a sleep laboratory (AAP 2012). Other methods, such as nocturnal video recordings, pulse oximetry, ambulatory polysomnography, or daytime nap polysomnography may be performed if standard polysomnography is not available (AAP 2012). The most commonly used polysomnographic parameter to identify children with OSA is the apnoea/hypopnoea index (AHI), which corresponds to the number of breathing pauses (apnoeas) or episodes of shallow breathing (hypopnoeas) per hour of sleep (AASM 2006). An AHI of one per hour or more is usually considered an abnormal finding in children (AASM 2006). As the sensitivity of polysomnographic equipment for the detection of apnoeas and hypopnoeas differs, the AHI may vary across sleep laboratories. Despite this shortcoming, the AHI is considered the mainstay for the diagnosis of OSA in children (AASM 2006).

Description of the intervention

If a child with OSA exhibits adenotonsillar hyperplasia and does not have a contraindication to surgery, surgical removal of enlarged adenoids and tonsils (adenotonsillectomy) is recommended as the first‐line treatment for OSA (AAP 2012), despite there being only one randomised controlled trial (RCT) that examined and demonstrated the benefits of adenotonsillectomy compared to watchful waiting (Marcus 2013). However, adenotonsillectomy is painful, requires hospitalisation and may result in anaesthetic complications, acute upper airway obstruction, haemorrhage, postoperative respiratory compromise, or velopharyngeal incompetence (Crysdale 1986; McColley 1992; Lee 1996; Ruboyianes 1996; AAP 2012). The frequency of complications from adenotonsillectomy range between 5% and 34% (AAP 2002). There is also evidence that OSA may persist after surgery. In a large follow‐up study, only 27% of children showed complete resolution of OSA after adenotonsillectomy (Bhattacharjee 2010). By contrast, the RCT by Marcus and colleagues reported normalisation of OSA in 79% of patients in the 'early adenotonsillectomy' group after seven months (Marcus 2013).

Given these findings, there is an increased interest in painless, safe, and effective non‐surgical treatment modalities for children with surgically untreated mild to moderate OSA or as a second‐line treatment of persisting or recurrent OSA after surgery. One promising alternative is the intranasal application of anti‐inflammatory medications such as corticosteroids (Kheirandish‐Gozal 2013).

How the intervention might work

As the enlarged adenoids and tonsils consist of hypertrophied lymphoid tissue, anti‐inflammatory medications may be effective in reducing the size of adenoids and tonsils and have therefore been proposed in the past as a useful non‐invasive treatment option in children with residual OSA or contraindications to surgery (Alexopoulos 2004; Goldbart 2005; Kheirandish 2006). This approach was further supported by the observation that a substantial proportion of children with OSA exhibit symptoms of allergic rhinitis (McColley 1997) or asthma (Brockmann 2014). Therefore, anti‐inflammatory drugs such as corticosteroids, leukotriene receptor antagonists (e.g. montelukast), and cromoglicic acid may be effective treatment options for childhood OSA.

Why it is important to do this review

Adenotonsillectomy as first‐line treatment for OSA has several disadvantages with regard to acceptance, safety, efficacy, sustainability of treatment effects, and costs and may not be readily available in regions with limited healthcare resources. Given the emerging evidence on non‐surgical alternatives to adenotonsillectomy, the role of anti‐inflammatory medications as first‐line treatment for OSA in childhood should be investigated in a systematic review.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of anti‐inflammatory drugs for the treatment of OSA in children.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all types of individual RCTs, including cross‐over trials, for inclusion in the review. We did not consider cluster randomised trials.

Types of participants

We included studies of children between one and 16 years of age with objectively diagnosed OSA (according to polysomnography; AHI ≥ 1/h, where AHI is the sum of obstructive and mixed apnoeas and obstructive hypopnoeas). We accepted studies with up to 20% of 17‐ to 18‐year‐old participants.

We excluded trials that only included participants with the following co‐morbidities: malformation syndromes, neuromuscular disorders, and morbid obesity (corresponding to a body mass index of 40 kg/m² or higher). OSA in children with these conditions is mainly driven by excess fatty tissue and anatomical and neurological factors and is therefore unlikely to be affected by anti‐inflammatory medications. Adenotonsillectomy, weight loss, and treatment with continuous positive airway pressure may be more appropriate treatments for OSA in these patient groups, particularly in children with obesity (Verhulst 2008).

Types of interventions

We included studies randomising participants to receive any anti‐inflammatory drugs used for the treatment of OSA in children. Eligible drugs with anti‐inflammatory properties included steroids, leukotriene receptor antagonists, ketotifen and chromones, administered either systemically or locally for any duration. Eligible comparison was against placebo.

Types of outcome measures

The diagnosis of OSA and indication for treatment are mainly based on clinical symptoms and the AHI as the primary objective indicator of OSA. In addition to the AHI, there are several polysomnography‐based indices such as arousal and desaturation indices that reflect the severity of OSA in children. As treatment is only indicated if complaints or subjective symptoms (or both) are reported, secondary outcomes include symptom scores and abnormalities in the physical examination.

Primary outcomes

AHI as measured by polysomnography

Serious adverse events

Secondary outcomes

Respiratory disturbance index as measured by polysomnography

Desaturation index as measured by polysomnography

Respiratory arousal index as measured by polysomnography

Nadir arterial oxygen saturation (SpO₂) as measured by polysomnography

Mean SpO₂ as measured by polysomnography

Avoidance of surgical treatment for OSA (in adenotonsillectomy‐naive children)

Clinical symptom score (based on parent report of, for example, snoring, witnessed apnoea, daytime sleepiness etc.)

Tonsillar size (on an ordinal scale from 0 (not visible) to +4 (tonsils touch))

Adverse events

We considered outcomes at all measured time points.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The first published version of this review was based on searches up to March 2010. For the current update, the last search was performed on 10 October 2019.

We identified trials from searches of the following databases.

The Cochrane Airways Trials Register (Cochrane Airways 2019), searched through the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS), all years to 17 October 2019

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), searched through the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS), all years to 17 October 2019

MEDLINE (Ovid SP) 1946 to 17 October 2019

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (www.ClinicalTrials.gov)

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.apps.who.int/trialsearch)

The search strategies are shown in Appendix 1. We did not restrict our search by language or type of publication.

Searching other resources

We searched the CENTRAL database and Cochrane Airways Trials Register for conference abstracts and grey literature. We reviewed the reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We contacted investigators of ongoing and unpublished completed trials that were identified in the trial register searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SK, MSU) independently screened titles and abstracts of the records retrieved by the electronic and handsearches. We based inclusion/exclusion of articles on the eligibility criteria outlined above. For potentially relevant articles, both review authors obtained and reviewed the full text for possible inclusion in the study. We resolved disagreement by discussion; no third party adjudication was necessary.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (SK, DH) independently performed data extraction using an electronic form. We checked accuracy of entered data manually. We assigned each study a unique study identifier and re‐checked for eligibility before data extraction.

The following data were extracted from the studies.

General: bibliographic details; funding source.

Methods: design; blinding; randomisation; dropouts/withdrawals; study quality assessment ('Risk of bias' tool).

Participants: country; target population; setting; number enrolled; diagnostic criteria used; inclusion/exclusion criteria; baseline demographic and clinical data (age, sex, AHI, respiratory disturbance index, desaturation index, respiratory arousal index, clinical symptom score, tonsillar size).

Interventions: intervention (type/dose/frequency/duration); comparison (type/dose/frequency/duration); compliance.

Outcome: timing of outcome assessment(s); reported outcomes (continuous: mean, and standard deviation or whichever measure of variability is reported; dichotomous: number of events) by group. For continuous outcomes, we recorded the number of participants, mean and standard deviation (or whichever measure of variability was reported) for each group and assessment. For dichotomous outcomes, we recorded the number of participants and the count of outcomes for each group and assessment.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two investigators (SK, MSU) independently assessed the quality of the trials. We evaluated each trial's quality using the 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011). The 'Risk of bias' tool appraises the study's adequacy in relation to the following six domains.

Sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors

Incomplete outcome data

Selective outcome reporting

Other sources of bias

We assigned a judgement of high, low or unclear risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous outcomes (AHI, desaturation index, and respiratory arousal index), we calculated the mean difference and 95% confidence interval (CI). For dichotomous outcomes (avoidance of surgical treatment for OSA), we had planned to calculate the relative risk and 95% CI. We had planned to treat ordinal outcomes (tonsillar size) as continuous.

Where only the median and interquartile range were reported for continuous outcomes, we planned to use the median instead of the mean and to calculate the standard deviation as interquartile range divided by 1.35, provided the sample size was large (Higgins 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the patient.

Dealing with missing data

We had planned to conduct a sensitivity analysis to explore the influence of studies where missing outcome data may have introduced a serious bias.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity using the Q‐test and the I² statistic. We considered values of more than 25% for the I² statistic to represent levels of statistical heterogeneity which would merit further investigation.

Assessment of reporting biases

We had planned to assess publication bias statistically using a linear regression approach and graphically using a funnel plot (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

We estimated treatment effects, separately pooled for corticosteroids and montelukast, using a random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Allergies/asthma/atopy are risk factors for OSA and can be effectively treated with anti‐inflammatory drugs. We had therefore planned to perform a subgroup analysis for children with and without allergies/asthma/atopy in order to assess if an observed treatment effect on OSA is only due to the anti‐allergic effect of the drug on the allergy/asthma/atopy. We had further planned a subgroup analysis for the type and route of administration of steroid used, and for trials with more than one drug in a treatment arm.

Sensitivity analysis

If heterogeneity had been detected, we would have performed sensitivity analyses to assess the effect of the following items on pooled estimates.

Low‐quality studies as assessed by the 'Risk of bias' tool

Random versus fixed‐effect modelling

Publication status

Funding source (drug manufacturer versus independent)

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created a 'Summary of findings' table using the outcomes AHI, desaturation index, respiratory arousal index, nadir SpO₂, and serious adverse events as these outcomes are considered to be clinically relevant according to current guidelines (Iber 2007). We used the five GRADE considerations (risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of a body of evidence as it relates to the studies that contribute data for the prespecified outcomes. We used the methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT). We justified all decisions to downgrade the certainty of the evidence for each outcome using footnotes and made comments to aid the reader's understanding of the review where necessary. The inclusion of a 'Summary of findings' table was a post hoc addition in the current review update.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

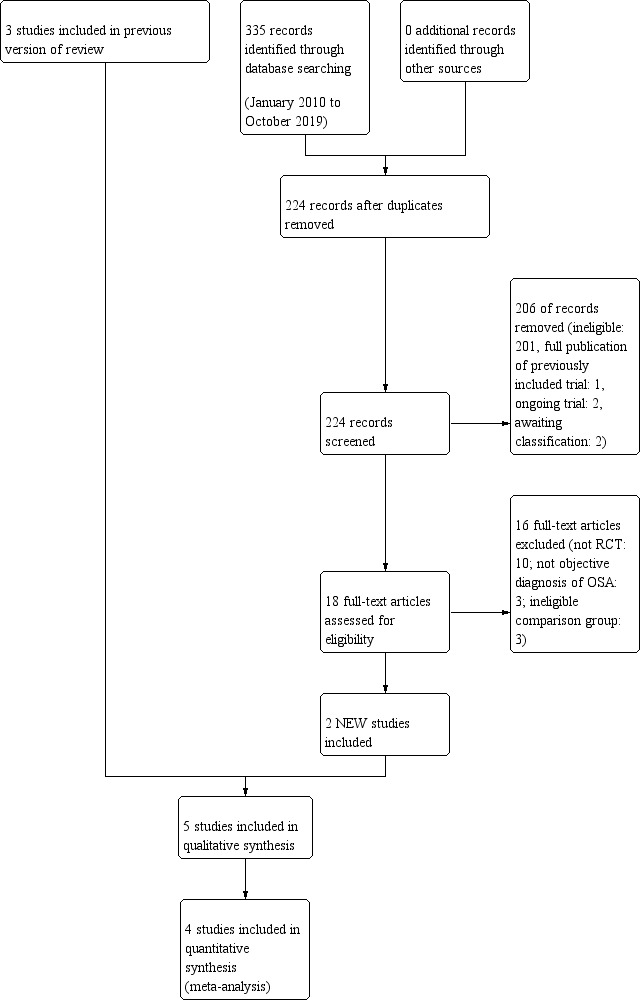

See Figure 1 for the study flow diagram. The original review identified three eligible studies (Kuhle 2011). The electronic database search run on 17 October 2019 retrieved 224 studies; a handsearch of conference proceedings did not identify any further studies. Screening of the titles and abstracts yielded 19 potentially relevant studies, two of which were eligible for inclusion in this review in addition to the three previously identified studies.

1.

Study flow diagram: review update

Abbreviations: RCT: randomised controlled trial; OSA: obstructive sleep apnoea

We found two ongoing studies (Aihuan 2012; Marcus 2014). Aihuan 2012 compares intranasal budesonide to oral montelukast; the trial registry record was last updated May 2015, but the lead investigator did not respond to our email requests. The Steroids for Pediatric Apnea Research in Kids (SPARK) trial compares a 3‐month course of nasal fluticasone against placebo in children with mild to moderate OSA (Marcus 2014). The trial is still recruiting and scheduled to be completed in June 2020.

We found two unpublished studies (Li 2007; Bernardi 2013). Li 2007 performed a randomised controlled trial of four months of intranasal mometasone furoate versus placebo in 52 children aged six to 18 years in Hong Kong. The registry entry was last updated in April 2017. Bernardi 2013 compared oral montelukast to intranasal budesonide. The study was completed in June 2010 but remains unpublished. We classified both studies as 'awaiting classification' because results were not available and the respective lead investigators have not responded to our email requests.

Included studies

We included five studies in this review (Brouillette 2001; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008; Goldbart 2012; Chan 2015; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016). Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008 included some children with an AHI of less than one per hour, while our inclusion criteria specified an AHI of one or more per hour. However, as only four out of the enrolled 62 children (6%) actually had an AHI less than one per hour at baseline, we decided to include the study and to perform a sensitivity analysis if necessary. All studies were single‐centre studies. Three trials were conducted in North America, one in Israel, one in Sweden, and one in China. Three studies were funded in part or fully by the drug manufacturer (Brouillette 2001; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016). For two studies, only the active drug and placebo were provided by the drug manufacturer (Goldbart 2012; Chan 2015).

Population

Brouillette 2001 included 25 children at a tertiary care centre between one and 10 years of age with mild to moderate OSA who had been referred from otolaryngologists for assessment before adenotomy/tonsillectomy. Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008 included 62 children between the ages of six and 11 years who were evaluated for mild to moderate OSA at a tertiary care centre. Goldbart 2012 enrolled 46 children between two and 10 years with non‐severe OSA (patients with AHI between 1 to < 10 per hour), who had been referred to a tertiary care centre for evaluation of their snoring. Chan 2015 included 62 children between six and 18 years of age with habitual snoring (≥ 3 nights per week) and mild OSA (obstructive AHI ≥ 1 to 5). Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016 included 57 children aged 2 to 10 years with symptomatic snoring with an of AHI of two or more but less than 30.

Brouillette 2001, Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008, Goldbart 2012, and Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016 excluded severe cases of OSA and children with recent or current steroid treatment. All studies excluded children with neuromuscular disorders. Brouillette 2001, Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008, Chan 2015 and Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016 excluded children with craniofacial anomalies. Goldbart 2012 also excluded children with obesity (BMI z‐score > 1.645), syndromic or defined genetic abnormalities, current or previous use of montelukast, acute upper respiratory tract infection, or use of corticosteroids or antibiotics. Chan 2015 also excluded children with genetic syndromes, congenital or acquired neurological diseases, previous upper airway surgery, or known fixed nasal obstruction such as previous nasal fracture. Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016 also excluded children under current treatment with corticosteroids or oral montelukast.

Study design

Four trials were parallel group designs with treatment for six weeks (Brouillette 2001), 12 weeks (Goldbart 2012), 16 weeks (Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016), and four months (Chan 2015), respectively. Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008 used a cross‐over design with a 2‐week washout period between the two 6‐week cycles.

Interventions

Three studies used nasal steroids: Brouillette 2001 used fluticasone 50 μg per nostril twice daily for the first week, followed by 50 μg per nostril once daily for the remaining five weeks. Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008 used budesonide 32 μg per nostril once daily for six weeks. Chan 2015 used mometasone furoate 100 µg per nostril once daily for four months. Goldbart 2012 and Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016 used montelukast 4 mg or 5 mg (depending on the child's age) orally once daily. The comparison group received placebo in all studies.

Outcomes assessed

Three of the included studies used the AHI as their primary outcome (Brouillette 2001; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008; Chan 2015). One study did not specify a primary endpoint (Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016). The trial registration record for the latter study had been withdrawn prior to enrolment, but listed the AHI as the primary endpoint (Kheirandish 2017). One study listed multiple primary endpoints (obstructive apnoea index, AHI, desaturation index, respiratory arousal index) (Goldbart 2012).

Other outcomes included the desaturation index (Brouillette 2001; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008; Goldbart 2012; Chan 2015; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016), respiratory or total arousal index (Brouillette 2001; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008; Goldbart 2012; Chan 2015; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016), nadir SpO₂ (Brouillette 2001; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008; Goldbart 2012; Chan 2015; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016), mean SpO₂ (Brouillette 2001), tonsillar size (Brouillette 2001; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008; Chan 2015; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016), and clinical symptom scores (Brouillette 2001, Chan 2015).

No study reported the avoidance of surgical treatment for OSA as an outcome, although it was listed as a primary outcome in Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016.

Excluded studies

We excluded 35 studies that were not RCTs, eight studies that did not use polysomnography to diagnose OSA or assess the outcome, and two studies that used adenotonsillectomy as the comparison group.

Risk of bias in included studies

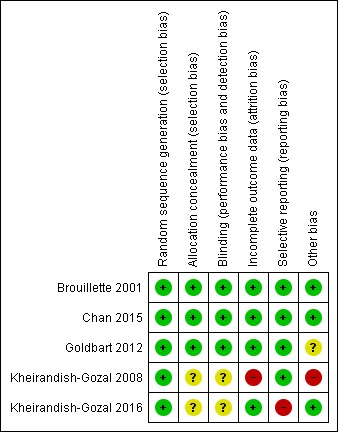

An overview of our risk of bias judgements can be found in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Adequacy of allocation concealment was unclear for two studies, because the research co‐ordinator was involved in allocation and patient management (Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016). All other studies were at low risk of selection bias.

Blinding

For two studies it was unclear whether the placebo was indistinguishable from the intervention, which may have compromised blinding of patients and personnel (Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016).

Incomplete outcome data

Brouillette 2001 and Goldbart 2012 reported complete data for all participants. The dropout rates in the trials by Chan 2015 (12/62) and Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016 (7/64) were similar for the intervention and control groups. Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008 had a significantly higher dropout rate in the group of children who were initially treated with placebo compared to those who initially received the intervention (14/32 vs. 5/30; relative risk 2.63, 95% CI 1.08 to 6.40), and we therefore judged it to be at high risk of bias. In addition, the reasons for withdrawal were not equally distributed between treatment arms.

Selective reporting

One trial did not report on the primary outcome (need for adenotonsillectomy) specified in the trial registration (Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016; Kheirandish 2017). The remaining four studies appeared to be free of selective outcome reporting, but trial registration information was not available for three of these studies (Brouillette 2001; Goldbart 2012; Chan 2015).

Other potential sources of bias

The cross‐over study, Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008, suffered from a number of potential biases. Firstly, study groups were imbalanced at baseline with the placebo‐first group having a mean AHI that was two standard errors lower than in the intervention group. Four out of 32 (13%) and none out of 30 participants (0%) had an AHI less than one per hour in the placebo and treatment groups, respectively. This baseline imbalance was also not accounted for in the analysis. Secondly, the authors presented and compared outcomes from children receiving intranasal budesonide in either arm with those who received placebo in the first arm, thereby omitting data from 25 children that received placebo in the second arm. Thirdly, the authors reported that those children who received budesonide in the first arm and placebo in the second arm had comparable sleep outcomes after the treatment phase compared with the placebo phase. This observation indicates that there might have been a carry‐over effect and that the cross‐over design or washout period was inadequate.

Goldbart 2012 performed an interim analysis after 30 patients had been enrolled. The impact of this analysis on blinding, trial continuation, and outcome selection is unclear.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Corticosteroids compared to placebo for obstructive sleep apnoea in children.

| Corticosteroids compared to placebo for obstructive sleep apnoea in children | ||||||

| Patient or population: obstructive sleep apnoea in children Setting: outpatients Intervention: corticosteroids Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with corticosteroids | |||||

| AHI (number of breathing pauses and episodes of shallow breathing per hour of sleep time) assessed with: polysomnography follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | The mean AHI was 5.18 per hour | MD 3.18 per hour lower (8.70 lower to 2.35 higher) | ‐ | 75 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| Desaturation index (number of times per hour of sleep time that the blood's O₂ level drops by a certain proportion from baseline) assessed with: polysomnography follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | The mean desaturation index was 3.0 per hour | MD 2.12 per hour lower (4.27 lower to 0.04 higher) | ‐ | 75 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | |

| Respiratory arousal index (number of times per hour of sleep time that an increased respiratory effort without a decrease in oxygen saturation is recorded) assessed with: polysomnography follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | The mean respiratory arousal index was 7.38 per hour | MD 0.71 per hour lower (6.25 lower to 4.83 higher) | ‐ | 75 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 3 4 | |

| Nadir SpO₂ (lowest SpO₂ during sleep) assessed with: polysomnography follow up: mean 12 weeks | The mean nadir SpO₂ was 88.24% | MD 0.59% higher (1.09 lower to 2.27 higher) | ‐ | 75 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | |

| Serious adverse events (N experiencing events) | No serious adverse events reported. The following unintended effects were reported: nasal bleeding (4), nasal discomfort (1), diarrhoea (1) | No serious adverse events reported. The following unintended effects were reported: nasal bleeding (3), nasal discomfort (1), throat discomfort (1), vomiting (1) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AHI: Apnoea/hypopnoea index; CI: Confidence interval; SpO₂: oxygen saturation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Point estimates vary considerably across studies, very little overlap between confidence intervals, P = 0.10 for heterogeneity, I² = 63%. Downgraded once for inconsistency of results.

2 Upper boundary of 95% confidence interval suggests potential for negative effect of the treatment on the outcome. Downgraded once for imprecision.

3 Point estimates vary considerably across studies, very little overlap between confidence intervals, P = 0.06 for heterogeneity, I² = 72%. Downgraded once for imprecision.

4 Point estimate indicates no clinically significant effect with wide confidence intervals. Downgraded once for imprecision.

Summary of findings 2. Montelukast compared to placebo for obstructive sleep apnoea in children.

| Montelukast compared to placebo for obstructive sleep apnoea in children | ||||||

| Patient or population: obstructive sleep apnoea in children Setting: outpatients Intervention: montelukast Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with montelukast | |||||

| AHI (number of breathing pauses and episodes of shallow breathing per hour of sleep time) assessed with: polysomnography follow‐up: mean 14 weeks | The mean AHI was 7.55 per hour | MD 3.41 per hour lower (5.36 lower to 1.45 lower) | ‐ | 103 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Desaturation index (number of times per hour of sleep time that the blood's O₂ level drops by a certain proportion from baseline) assessed with: polysomnography follow‐up: mean 14 weeks | The mean desaturation index was 5.16 per hour | MD 2.5 per hour lower (5.53 lower to 0.54 higher) | ‐ | 103 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | |

| Respiratory arousal index (number of times per hour of sleep time that an increased respiratory effort without a decrease in oxygen saturation is recorded) assessed with: polysomnography follow‐up: mean 14 weeks | The mean respiratory arousal index was 9.70 per hour | MD 2.89 per hour lower (4.68 lower to 1.10 lower) | ‐ | 103 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 4 | |

| Nadir SpO₂ (lowest SpO₂ during sleep) assessed with: polysomnography follow‐up: mean 14 weeks | The mean nadir SpO₂ was 87.38% | MD 4.07% higher (2.27 higher to 5.88 higher) | ‐ | 103 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | |

| Serious adverse events (N experiencing event) | No serious adverse events reported. The following unintended effects were reported: headache (1), nausea (2) | No serious adverse events reported. The following unintended effects were reported: headache (1), nausea (1) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). AHI: Apnoea/hypopnoea index; CI: Confidence interval; SpO₂: oxygen saturation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Point estimates vary across studies, P = 0.10 for heterogeneity, I² = 54%. Downgraded once for inconsistency of results.

2 Point estimates vary greatly across studies, P = 0.004 for heterogeneity, I² = 88%. Downgraded once for inconsistency of results.

3 Upper boundary of 95% confidence interval suggests potential for negative effect of the treatment on the outcome. Downgraded once for imprecision.

4 Point estimates vary across studies, P = 0.12 for heterogeneity, I² = 59%. Downgraded once for imprecision.

Given that the authors of the intranasal budesonide trial did not analyse the data according to the randomisation and were unable to provide us with their results for the first phase of the study, we did not consider this trial in the analysis (Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008). We pooled in separate meta‐analyses results from two trials on corticosteroids (n = 75; Brouillette 2001; Chan 2015), and two trials on montelukast (n = 103; Goldbart 2012; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016).

Corticosteroids versus placebo

Primary outcomes

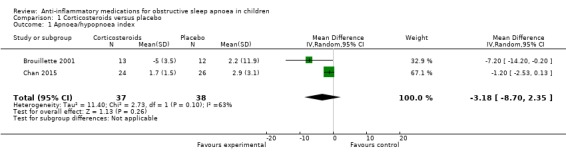

The mean change in the AHI was −3.18 per hour (95% CI −8.70 to 2.35; 2 studies, 75 participants; Analysis 1.1) in children receiving intranasal corticosteroids compared to placebo. There was heterogeneity in the estimates between the studies (P = 0.10 for heterogeneity, I² = 63%). Due to imprecision of the estimate and considerable heterogeneity between studies, we rated the overall certainty of the evidence as low. No serious adverse events were reported.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Corticosteroids versus placebo, Outcome 1 Apnoea/hypopnoea index.

Secondary outcomes

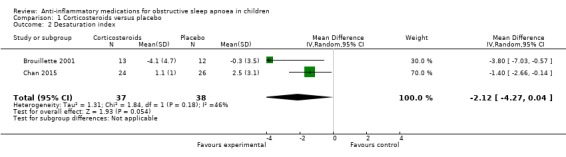

The desaturation index changed by −2.12 per hour (95% CI −4.27 to 0.04; 2 studies, 75 participants; Analysis 1.2) in the intervention group compared to the control group. We rated the overall certainty of the evidence as moderate due to imprecision.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Corticosteroids versus placebo, Outcome 2 Desaturation index.

The respiratory arousal index changed by −0.71 (95% CI −6.25 to 4.83; 2 studies, 75 participants; Analysis 1.3) in the intervention group compared to the control group. Due to the small effect and considerable heterogeneity between studies (P = 0.06 for heterogeneity, I² = 72%), we rated the overall certainty of the evidence as low.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Corticosteroids versus placebo, Outcome 3 Respiratory arousal index.

The nadir SpO₂ increased by 0.59% (95% CI −1.09 to 2.27; 2 studies, 75 participants; Analysis 1.4) in the intervention group compared to the control group. Due to imprecision, we rated the overall certainty of the evidence as moderate.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Corticosteroids versus placebo, Outcome 4 Nadir oxygen saturation.

The difference in change in mean SpO₂, tonsillar size, and symptom score was uncertain between the fluticasone group and the control group in Brouillette 2001 (n = 25). We are uncertain about any difference in nasal symptoms between the mometasone and placebo groups (Chan 2015, n = 50). Adverse events reported were minor and infrequent and appeared similar between the intervention and placebo groups (Table 3).

1. Adverse events.

| Study | Intervention (N experiencing event) | Control (N) | Comments |

| Brouillette 2001 | 0 | nose bleed (1) | |

| Goldbart 2012 | 0 | 0 | |

| Chan 2015 | nasal bleeding (3), nasal discomfort (1), throat discomfort (1), vomiting (1) | nasal bleeding (3), nasal discomfort (1), diarrhoea (1) | Total number of adverse events reported (10) does not match sum of individual adverse events (11) |

| Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016 | headache (1), nausea (1) | headache (1), nausea (2) |

Since Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008 did not analyse and report their data as randomised, we did not consider this trial in the analysis.

Montelukast versus placebo

Primary outcomes

The mean change in the AHI was −3.41 per hour (95% CI −5.36 to −1.45; 2 studies, 103 participants; Analysis 2.1) in children receiving montelukast compared to placebo. There was considerable heterogeneity between the studies (P = 0.14 for heterogeneity, I² = 54%), and we therefore rated the certainty of the evidence as moderate. No serious adverse events were reported.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Montelukast versus placebo, Outcome 1 Apnoea/hypopnoea index.

Secondary outcomes

The desaturation index changed by −2.50 per hour (95% CI −5.53 to 0.54; 2 studies, 103 participants; Analysis 2.2) in the intervention group compared to the control group. Point estimates also varied greatly across studies (P = 0.004 for heterogeneity, I² = 88%). Due to imprecision of the estimate and considerable heterogeneity between studies, we rated the overall certainty of the evidence as low.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Montelukast versus placebo, Outcome 2 Desaturation index.

The respiratory arousal index changed by −2.89 (95% CI −4.68 to −1.10; 2 studies, 103 participants; Analysis 2.3) in the intervention group compared to the control group. Due to considerable heterogeneity between studies (P = 0.12 for heterogeneity, I² = 59%), we rated the overall certainty of the evidence as moderate.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Montelukast versus placebo, Outcome 3 Respiratory arousal index.

The nadir SpO₂ increased by 4.07% (95% CI 2.27% to 5.88%; 2 studies, 103 participants; Analysis 2.4) in the intervention group compared to the control group. We rated the overall certainty of the evidence as high.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Montelukast versus placebo, Outcome 4 Nadir oxygen saturation.

The difference in change in mean SpO₂ was uncertain between the intervention group and the control group (Goldbart 2012, n = 46). There was also uncertainty over the difference in tonsillar size between the intervention and control group (Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016, n = 57). One study did report no adverse events (Goldbart 2012); while the other reported minor adverse events in two and three children in the intervention and control group, respectively (Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016) (Table 3).

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this review, we aimed to evaluate the available evidence on anti‐inflammatory medications as treatment for OSA in children. We included five RCTs evaluating four different drugs in the review; and we included four studies evaluating three drugs in the meta‐analysis. Sample sizes of the included studies were small, with the largest one enrolling 62 children. Three trials investigated intranasal corticosteroids (fluticasone, budesonide, and mometasone) and two assessed the oral leukotriene receptor antagonist montelukast. We did not find any studies that examined other anti‐inflammatory medications for the treatment of OSA.

In both trials that examined intranasal corticosteroids, the AHI in the intervention group decreased compared to placebo. However, based on the pooled effect estimate from the meta‐analysis, we are uncertain about the reduction of the AHI. We are also uncertain about the effects of corticosteroids on the desaturation index, the respiratory arousal index, the nadir SpO₂, the mean SpO₂, tonsillar size, or the symptom score. We rated the overall certainty of the evidence as low for the AHI and respiratory arousal index and moderate for the desaturation index and the nadir SpO₂.

Meta‐analysis of the results from the two montelukast trials demonstrated a beneficial effect of montelukast on the AHI, the respiratory arousal index, and the nadir SpO₂. The overall certainty of the evidence was low for the desaturation index, moderate for the AHI and respiratory arousal index, and high for the nadir SpO₂. We are uncertain about the difference in the mean SpO₂ and the tonsillar size. The clinical relevance of the observed intervention effects on AHI, respiratory arousal index, and nadir SpO₂ remains unclear, however, because minimal clinically important differences for these outcomes have not been established yet in paediatric sleep medicine. The effect sizes (Cohen's d) for the AHI in the two studies were 0.86 and 1.12 (Goldbart 2012 and Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016 respectively), which would be considered a large effect based on the cut‐off (> 0.8) proposed by Cohen 1988. Hence, the overall treatment effect of montelukast may be deemed clinically relevant.

Adverse events were rare and of minor nature for both medications, and their frequency did not differ between the intervention and control groups. Hence, the short‐term use of intranasal steroids and montelukast appears to be well tolerated.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The five included studies were limited to less severe forms of OSA because adenotonsillectomy is considered the treatment of choice for children with moderate to severe OSA. All studies excluded children with neuromuscular disorders and most studies excluded children with genetic and craniofacial anomalies. Only one study included adolescents and all studies excluded newborns and infants below two years of age. All studies measured the AHI and SpO₂ parameters, which are accurate markers of the presence and severity of OSA in children. Hence, the evidence from the studies primarily applies to otherwise healthy preschool and school‐aged children with mild to moderate forms of OSA and without other concomitant severe chronic diseases. The evidence cannot be applied to newborns, infants, and adolescents or to children with more severe or complex forms of OSA. The latter limitation largely reflects current practice, however, as infants and children with OSA related to an underlying genetic disorder should undergo a thorough diagnostic evaluation and receive individualised treatment combinations such as surgery, respiratory support, and/or intraoral appliances. Efficacy and safety data for anti‐inflammatory medications for the treatment of OSA in childhood are currently only available for up to four months; no study has examined long‐term efficacy and safety. Similarly, studies have almost exclusively used clinical outcomes instead of more patient‐centred outcomes such as concentration ability, executive functioning, vigilance, behavior, school performance, or health‐related quality of life.

Certainty of the evidence

The certainty of the evidence for the effect of intranasal corticosteroids on the AHI was low. We could not include one of the three studies in the meta‐analysis due to high risk of bias, leaving only two studies with 75 patients. There was heterogeneity in the estimates between the studies (P = 0.10 for heterogeneity, I² = 63%). As a result, even though both studies individually showed statistically significant reductions in the AHI in the intervention group compared to the control group, the confidence interval of the pooled estimate of the treatment effect included the null when we analysed study results using a random‐effects model. The certainty of the evidence for the secondary outcomes ranged from low (respiratory arousal index) to moderate (desaturation index and nadir SpO₂). We downgraded the rating for the outcome 'respiratory arousal index' because of the small treatment effect and considerable heterogeneity between studies.

The certainty of the evidence for a beneficial effect of montelukast on the AHI was moderate. The effect estimate was fairly precise, but the two included studies were of unclear and high risk of bias, respectively, and there was considerable heterogeneity between the studies (P = 0.14 for heterogeneity, I² = 54%). The certainty of the evidence for the secondary outcomes ranged from low (desaturation index) and moderate (respiratory arousal index) to high (nadir SpO₂). We downgraded the certainty of the evidence for desaturation index and respiratory arousal index for the considerable heterogeneity between the two studies. We further reduced the rating for the desaturation index for imprecision.

The specific methodological issues of the included studies are as follows. The trial comparing budesonide to placebo had a number of methodological issues that precluded its results from being used in the meta‐analysis (Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008). There was a higher number of withdrawals in the group of children who started on placebo compared with those who started on budesonide. In addition, there appeared to be a carry‐over effect and this effect was not appropriately dealt with in the analysis. Finally, the authors did not include the data of those children who received placebo in the second phase of the study, thereby effectively breaking the randomisation. We contacted the investigators to obtain the data for the first phase of the study, but they were unable to provide us with the data. Goldbart 2012 performed an unplanned interim analysis, and it is unclear what influence this analysis had on the further conduct of the trial with regard to blinding and outcome selection. We deemed the other trial that compared montelukast with placebo to be at high risk of bias (Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016). The primary outcome stated in the trial registration (need for adenotonsillectomy) was not examined in the published paper; instead, a sample size calculation based on the outcome AHI is presented (Kheirandish 2017). It is unclear whether the AHI was in fact the primary outcome of the study.

The small number of participants in the trials limited our ability to detect serious or rare adverse events. All trials included were of short‐term nature with follow‐up time between six and 16 weeks post treatment. Hence the sustainability of the treatment effects and the occurrence of late or long‐term adverse events remain unclear.

Out of the five included studies, three trials had not been registered a priori (Brouillette 2001; Goldbart 2012; Chan 2015); and for one trial the registration was withdrawn before enrolment (Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016). Given this high proportion of unregistered trials, we cannot exclude reporting bias due to unregistered trials with negative findings.

Potential biases in the review process

We conducted the review in accordance with the Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews guidelines (MECIR 2018). Except for some minor deviations (see Differences between protocol and review), we followed our protocol. We used a broad literature search developed by a Cochrane information specialist. All steps in the review process were performed independently by two reviewers. The review underwent editorial review with the Cochrane Airways Group as well as peer review. Taken together, we are confident that the conclusions from this review represent an objective, fair, and accurate assessment of the current state of the evidence.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There are no other systematic reviews that have specifically examined the association between anti‐inflammatory medications and OSA in children. A network meta‐analysis in 2017 compared the effects of fluticasone, budesonide, montelukast, mometasone, and caffeine on the AHI in children with OSA (Zhang 2017). The RCTs on anti‐inflammatory medications that were included in that review were also identified in the present review (Brouillette 2001; Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008; Goldbart 2012; Chan 2015). The authors concluded that fluticasone and budesonide have "good effects" in the treatment of OSA. This conclusion should, however, be interpreted with great caution as the authors included the study by Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008 in their analysis, which we excluded due to serious risk of bias.

A Cochrane Review examined the effect of intranasal corticosteroids for nasal airway obstruction in children with moderate to severe adenoidal hyperplasia (Zhang 2008). More recently, a systematic review examined the effect of mometasone on adenoid hyperplasia among children with OSA (Chohan 2015). Both reviews found evidence for a beneficial effect of corticosteroids and mometasone, respectively. Since adenoidal hyperplasia can be considered a risk factor for OSA, the findings lend further support for the use of intranasal corticosteroids in children with OSA.

Lastly, a Cochrane Review of drug therapies for OSA in adults included only one trial (out of 30 in total) that used an anti‐inflammatory drug (Mason 2013), reflecting the different pathophysiology and treatment of OSA in children and adults (Alsubie 2017). The investigators found that fluticasone in patients with allergic rhinitis reduced the severity of OSA compared to placebo and improved subjective daytime alertness (Kiely 2004).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is insufficient evidence for the efficacy of intranasal corticosteroids for the treatment of OSA in children; they may have short‐term beneficial effects on the desaturation index and SpO₂ in children with mild to moderate OSA, but the certainty of the benefit on the primary outcome AHI as well as the respiratory arousal index was low due to imprecision of the estimates and heterogeneity between studies.

Montelukast has a short‐term beneficial, clinically meaningful effect for the treatment of OSA in otherwise healthy, non‐obese, surgically untreated children by reducing the number of apnoeas, hypopnoeas, and arousals during sleep as well as by improving SpO₂ during sleep. There is moderate certainty for the primary outcome AHI and moderate and high certainty, respectively, for two secondary outcomes. Montelukast appeared to be well tolerated.

There are no RCTs on the use of other kinds of anti‐inflammatory medications for the treatment of OSA in children.

Long‐term efficacy and safety data on the use of anti‐inflammatory medications for the treatment of OSA in childhood are still not available, and a sustained effect of anti‐inflammatory medications to avoid surgical treatment for OSA has not been investigated yet. Regular follow‐up visits for children with OSA, who are or have been treated with anti‐inflammatory medications, may be necessary to detect reoccurrence of OSA after successful treatment.

Implications for research.

The limited evidence on the use of anti‐inflammatory medications for the treatment of OSA in childhood suggests that further research is warranted.

We excluded a number of potentially eligible trials from this review because of the lack of polysomnographic assessment to ascertain the presence and severity of OSA. Future studies should use attended overnight polysomnography in a sleep laboratory to objectively diagnose OSA and assess treatment efficacy as recommended by current clinical guidelines (Iber 2007; Berry 2012).

The methodological quality of studies in this area could be improved. The validity of the findings may be limited due to selective outcome reporting and publication bias. Investigators should perform realistic sample size calculations based on pilot data, a priori define their primary outcome and adhere to it, and register their study prior to the start of patient recruitment. Cross‐over trials should be avoided when examining anti‐inflammatory medications for the treatment of OSA due to the long‐lasting effects of the drugs and the resulting carry‐over effect.

All trials included only had short‐term follow‐up time between six and 16 weeks post treatment, so the long‐term sustainability of the treatment effects remains unclear. Future studies should therefore use follow‐up periods of up to one year.

All outcomes in the included trials were of a clinical nature, and more patient‐centred outcomes have not been investigated. The primary reason many caregivers give to seek treatment for their children are concerns about loud snoring, poor sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, concentration deficits, impaired behavior, or poor school performance. Researchers should therefore include these outcomes as well as health‐related quality of life in future studies, in particular since there are validated instruments for these outcomes available (e.g. Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire, OSA‐18, Epworth Sleepiness Scale). Patient‐reported outcomes and health‐related quality of life should be included in future updates of the present review.

Lastly, further studies are needed to determine whether anti‐inflammatory medications are effective in obese children with OSA, in children with more severe OSA, in children with persisting or recurrent OSA after adenotonsillectomy, and in children with OSA and contraindications to surgery. These children are the ones that most often experience complications of — or do not respond to — adenotonsillectomy and would, therefore, benefit from non‐surgical treatment options for their condition.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 October 2019 | New search has been performed | New literature search run. |

| 17 October 2019 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Four new studies added. Two new authors added. Methods updated to reflect current Cochrane guidelines (e.g., summary of findings table added). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2008 Review first published: Issue 1, 2011

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

The Background and Methods sections of this review are based on a standard template used by Cochrane Airways.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help with the literature search from Liz Stovold, Cochrane Airways.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Airways Group. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, National Health Service, or the Department of Health.

The authors and Airways Editorial Team are grateful to the following peer reviewers for their time and comments.

Aviv Goldbar, Saban Pediatric Medical Center, Ben Gurion University, Israel;

Caroline Mitchell, University of Sheffield, UK; and

Cristina Baldassari, Eastern Virginia Medical School, USA

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

Database: CENTRAL and Cochrane Airways Trials Register

Platform: Cochrane Register of Studies

#1 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Sleep Apnea, Obstructive #2 (sleep near3 (apnoea* or apnoea*)):TI,AB,KY #3 ((hypopnea* or hypopnoea*)):TI,AB,KY #4 OSA OR SHS OR OSAHS:TI,AB #5 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 #6 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Anti‐Inflammatory Agents Explode All #7 (antiinflam* OR anti* NEXT inflam*):TI,AB,KY #8 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Adrenal Cortex Hormones Explode All #9 (steroid* OR corticosteroid* OR glucocorticoid* OR corticoid*):TI,AB,KY #10 (ciclesonide* OR fluticasone* OR beclomet* OR budesonide* OR flunisolide* OR triamcinolone* OR mometasone* OR predniso*):TI,AB,KY #11 (leucotrien* OR leukotrien* OR LTRA* OR montelukast OR zafirlukast OR pranlukast):TI,AB,KY #12 ketotifen*:TI,AB,KY #13 (cromolyn* OR chromolyn* OR cromogl* OR chromogl* OR nedocromil* ):TI,AB,KY #14 #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 #15 #5 AND #14 #16 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Child Explode All #17 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Pediatrics Explode All #18 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Infant Explode All #19 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Adolescent #20 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Minors #21(paediatric* or paediatric* or child* or adolescen* or infant* or young* or preschool* or pre‐school* or newborn* or new‐born* or neonat* or neo‐nat* ):TI,AB,KY #22 #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 #23 #5 AND #15 AND #22

Database: MEDLINE

Platform: Ovid SP

1. exp Sleep Apnea, Obstructive/ 2. (sleep$ adj3 (apnoea$ or apnoea$)).tw. 3. (hypopnea$ or hypopnoea$).tw. 4. or/1‐3 5. exp Anti‐Inflammatory Agents/ 6. (antiinflam$ or anti‐inflam$).tw. 7. exp Adrenal Cortex Hormones/ 8. (steroid$ or corticosteroid$ or glucocorticoid$ or corticoid$).tw. 9. (ciclesonide$ or fluticasone$ or beclomet$ or budesonide$ or flunisolide$ or triamcinolone$ or mometasone$ or predniso$).tw. 10. (leucotrien$ or leukotrien$ or LTRA or montelukast or zafirlukast or pranlukast).tw. 11. ketotifen$.tw. 12. (cromolyn$ or chromolyn$ or cromogl$ or chromogl$ or nedocromil$).tw. 13. or/5‐12 14. exp Child/ 15. exp Pediatrics/ 16. exp Infant/ 17. Adolescent/ 18. Minors/ 19. (paediatric$ or paediatric$ or child$ or adolescen$ or infant$ or young$ or preschool$ or pre‐school$ or newborn$ or new‐born$ or neonat$ or neo‐nat$).tw. 20. or/14‐19 21. 4 and 13 and 20 22. (controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial).pt. 23. (randomized or randomised).ab,ti. 24. placebo.ab,ti. 25. dt.fs. 26. randomly.ab,ti. 27. trial.ab,ti. 28. groups.ab,ti. 29. or/22‐28 30. Animals/ 31. Humans/ 32. 30 not (30 and 31) 33. 29 not 32 34. 21 and 33

Database: ClinicalTrials.gov

Study type: Interventional

Condition: sleep apnoea

Intervention: steroid OR corticosteroid OR glucocorticoid OR corticoid OR ciclesonide OR fluticasone OR beclomet OR budesonide OR flunisolide OR triamcinolone OR mometasone OR prednisone OR leukotriene OR leukotriene OR LTRA OR montelukast OR zafirlukast OR pranlukast OR ketotifen OR cromolyn OR chromolyn OR cromogl* OR chromogl* OR nedocromil OR anti‐inflammatory OR anti‐inflammatory

Age group: Child

Database: WHO ICTRP

Condition: sleep apnoea

Intervention: steroid OR corticosteroid OR glucocorticoid OR corticoid OR ciclesonide OR fluticasone OR beclomet OR budesonide OR flunisolide OR triamcinolone OR mometasone OR prednisone OR leukotriene OR leukotriene OR LTRA OR montelukast OR zafirlukast OR pranlukast OR ketotifen OR cromolyn OR chromolyn OR cromogl* OR chromogl* OR nedocromil OR anti‐inflammatory OR anti‐inflammatory

Age group: Child

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Corticosteroids versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Apnoea/hypopnoea index | 2 | 75 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.18 [‐8.70, 2.35] |

| 2 Desaturation index | 2 | 75 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.12 [‐4.27, 0.04] |

| 3 Respiratory arousal index | 2 | 75 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.71 [‐6.25, 4.83] |

| 4 Nadir oxygen saturation | 2 | 75 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.59 [‐1.09, 2.27] |

Comparison 2. Montelukast versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Apnoea/hypopnoea index | 2 | 103 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.41 [‐5.36, ‐1.45] |

| 2 Desaturation index | 2 | 103 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.50 [‐5.53, 0.54] |

| 3 Respiratory arousal index | 2 | 103 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.89 [‐4.68, ‐1.10] |

| 4 Nadir oxygen saturation | 2 | 103 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 4.07 [2.27, 5.88] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Brouillette 2001.

| Methods | Parallel group RCT | |

| Participants | 25 children, age 1 to 10 years, with adenotonsillar hyperplasia, signs and symptoms of OSA, and AHI ≥ 1 per hour | |

| Interventions | Fluticasone 50 μg per nostril twice daily for 1 week, followed by 50 μg once daily for 5 weeks; comparison against placebo for 6 weeks | |

| Outcomes | AHI, desaturation index, respiratory arousal index, sleep time with paradoxical movement of chest and abdomen, respiratory rate, heart rate, SpO₂ (mean and minimum), sleep efficiency, adenoidal/nasopharyngeal ratio, minimal airway size, tonsillar size, symptom score; measured after 6 weeks | |

| Notes | Enrolment period: November 1997 to October 1999 Funding sources: The Hospital for Sick Children Foundation and GlaxoWellcome. Declaration of interest: not provided. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomization was performed from a table of random numbers." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The study drug was dispensed by a pharmacist to an investigator." "Only the study pharmacist was aware of the group assignment." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Fluticasone propionate (Flonase, GlaxoWellcome) and placebo were provided in identical containers by the drug manufacturer. The appearance and smell of the fluticasone and placebo were indistinguishable." "Sleep laboratory personnel, subjects, parents, and physicians were all blinded to group assignment until the entire study was completed and analyzed." "The statistician knew that there were 2 groups but was blinded to which group was placebo and which treatment was used (triple‐blind method)." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All randomised participants finished the study. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No study protocol or trial registration were available, but outcomes appeared to be complete. |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Chan 2015.

| Methods | Parallel group RCT | |

| Participants | 62 children aged 6 to 18 with mild OSA (OAHI 1 to 5 per hour) | |

| Interventions | Mometasone 100 µg per nostril for 4 months; comparison against placebo for 4 months | |

| Outcomes | AHI, tonsil and adenoid size, nasal symptoms; measured after 4 months | |

| Notes | Enrolment period: May 2006 to March 2008 Funding sources: study medication and placebo were provided by Schering‐Plough; design and conduct of the study was done by the investigator without funding. Declaration of interest: Dr. Yun Wing received a honorarium for serving as a part‐time paid consultant for Renascence Therapeutics. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "The allocation was based on a computer‐generated randomisation list with varying block sizes." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The children were allocated to receive mometasone furoate (MF) or placebo, using double‐blinded randomisation with a sealed opaque envelope method." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Corticosteroids (MF) and placebo were provided in numbered identical containers. The appearances of the active drug and placebo were indistinguishable." "The PSG data were scored and interpreted by an experienced sleep technologist who was blinded to the subjects’ group allocation." "An otorhinolaryngologist, who was blinded to the group allocation and PSG result of the participants, performed the [upper airway] examination." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 12/62 children (7 intervention, 5 placebo) dropped out; 5 children (3 intervention, 2 placebo) withdrew because of side effects; 7 children (4 intervention, 3 placebo) were lost to follow‐up. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No study protocol or trial registration were available, but outcomes appeared to be complete. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None. |

Goldbart 2012.

| Methods | Parallel group RCT | |

| Participants | 46 children, age 2 to 10 years, with snoring and mild to moderate OSA (AHI 1 to 8 per hour) | |

| Interventions | Montelukast 4 mg or 5 mg (depending on the child's age) orally for 12 weeks; comparison against placebo for 12 weeks | |

| Outcomes | AHI, adenoidal/nasopharyngeal ratio; measured after 12 weeks | |

| Notes | Enrolment period: not stated Funding sources: Dr. Asher Tal received research support and the study medication from MSD Israel. Declaration of interest: Dr. Asher Tal participated in speaking engagements for MSD, Teva, and Sanofi‐Aventis. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "We chose block randomisation (blocks of 4, by using a table of random digits) to create the allocation sequence." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "The numbers on the containers (medication and placebo) were drawn by the chief pharmacist (according to the numbers in the randomisation table)." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "During the study, the investigators were blinded to group assignment. Montelukast and placebo tablets were provided in identical, similarly colored, opaque capsules." "[Sleep] studies were initially scored by a certified technician. The scores were then blindly reviewed by 2 physicians experienced in paediatric polysomnography." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All randomised participants finished the study. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No study protocol or trial registration were available, but outcomes appeared to be complete. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | The investigators performed an interim analysis after 30 children (Goldbart 2012) were enrolled; it is unclear how the analysis and results affected blinding, trial continuation, and outcome selection. |

Kheirandish‐Gozal 2008.

| Methods | Cross‐over RCT | |

| Participants | 62 children, age 6 to 11 years, with habitual snoring and mild OSA on PSG | |

| Interventions | Budesonide 32 μg per nostril once daily for 6 weeks; comparison against placebo for 6 weeks; washout period of 2 weeks | |

| Outcomes | AHI, total arousal index, respiratory arousal index, nadir SpO₂, sleep efficiency, latency to sleep onset, latency to REM sleep, % REM sleep, end‐tidal CO₂ tension, adenoidal/nasopharyngeal ratio; measured after 6 (phase 1) and 12 weeks (phase 2). | |

| Notes | Enrolment period: April 2004 to May 2006 Funding sources: Investigator‐initiated grant from AstraZeneca Ltd to Dr. Leila Kheirandish‐Gozal Declaration of interest: Dr. Leila Kheirandish‐Gozal is the recipient of investigator‐initiated grants from AstraZeneca Ltd and Merck & Co. for studies in paediatric sleep apnoea; Dr. David Gozal is on the National Speaker Bureau of Merck & Co. and has received honoraria for lectures. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "using a double‐blind, randomisation, crossover procedure generated using random computer numeral allocation" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Research coordinator was involved in both allocation and patient management "children who fulfilled the study inclusion criteria on the basis of the PSG‐1 findings were recruited by 1 of the authors and assigned by a clinical research coordinator to 1 of 2 treatment groups [...] and managed by the same clinical research coordinator who was otherwise not involved in any aspect of the study" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear whether placebo was indistinguishable from the intervention and whether data analyst was blinded. "randomized, double‐blind, crossover design" "All of the studies were initially scored by a certified technician and were then blindly reviewed by 2 physicians who were experienced in paediatric polysomnography" "The adenoidal/nasopharyngeal ratio was then measured according to the method of Fujioka et al by 1 of the investigators (Dr Gozal), who was blinded to the treatment group and PSG findings of the children." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | "Of the 62 participants, 43 completed all phases of the protocol, and 19 children completed the first arm of the protocol and subsequently decided to withdraw. Among the latter, 14 children were in the placebo treatment group and 5 were in the budesonide treatment group. Thus, the relative risk for withdrawal from the study was 2.80 for children who started on placebo compared with those who started with intranasal budesonide (95% confidence interval: 1.15– 6.83; P=0.02 after Mantel‐Haenszel correction)." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All pre‐specified outcomes reported; no evidence of selective reporting of outcomes |

| Other bias | High risk | 1. Study groups were imbalanced at baseline with the placebo‐first group having a mean AHI 2 standard errors lower than in the intervention group 2. The authors presented and compared outcomes from children receiving budesonide in either arm with those who received placebo in the first arm, thereby omitting data from 25 children that received placebo in the second arm 3. Children who received budesonide in the first arm and placebo in the second arm had comparable sleep outcomes after the treatment phase versus the placebo phase, possibly indicating a carry‐over effect |

Kheirandish‐Gozal 2016.

| Methods | Parallel group RCT | |

| Participants | 64 children, aged 2 to 10 years, with symptomatic snoring (AHI ≥ 2 hours total sleep time) | |

| Interventions | Montelukast 4 mg or 5 mg (depending on the child's age) orally for 16 weeks; comparison against placebo for 16 weeks | |

| Outcomes | AHI, respiratory arousal index, adenoid size | |

| Notes | Enrolment period: January 2008 to December 2012 Funding sources: Investigator‐initiated grant from Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp. Declaration of interest: not provided |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "[...] using a table of random digits to generate the allocation sequence" |