Abstract

Background

Approximately 20% of people with cirrhosis develop ascites. Several different treatments are available; including, among others, paracentesis plus fluid replacement, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts, aldosterone antagonists, and loop diuretics. However, there is uncertainty surrounding their relative efficacy.

Objectives

To compare the benefits and harms of different treatments for ascites in people with decompensated liver cirrhosis through a network meta‐analysis and to generate rankings of the different treatments for ascites according to their safety and efficacy.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, Science Citation Index Expanded, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and trials registers until May 2019 to identify randomised clinical trials in people with cirrhosis and ascites.

Selection criteria

We included only randomised clinical trials (irrespective of language, blinding, or status) in adults with cirrhosis and ascites. We excluded randomised clinical trials in which participants had previously undergone liver transplantation.

Data collection and analysis

We performed a network meta‐analysis with OpenBUGS using Bayesian methods and calculated the odds ratio, rate ratio, and hazard ratio (HR) with 95% credible intervals (CrI) based on an available‐case analysis, according to National Institute of Health and Care Excellence Decision Support Unit guidance.

Main results

We included a total of 49 randomised clinical trials (3521 participants) in the review. Forty‐two trials (2870 participants) were included in one or more outcomes in the review. The trials that provided the information included people with cirrhosis due to varied aetiologies, without other features of decompensation, having mainly grade 3 (severe), recurrent, or refractory ascites. The follow‐up in the trials ranged from 0.1 to 84 months. All the trials were at high risk of bias, and the overall certainty of evidence was low or very low.

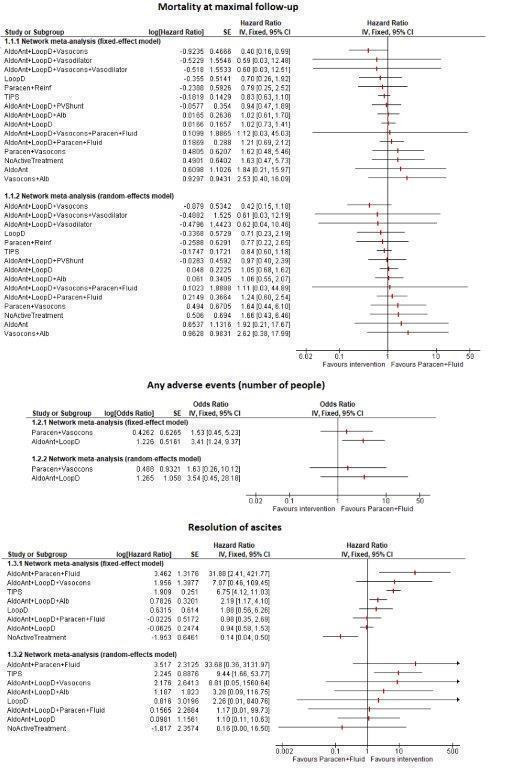

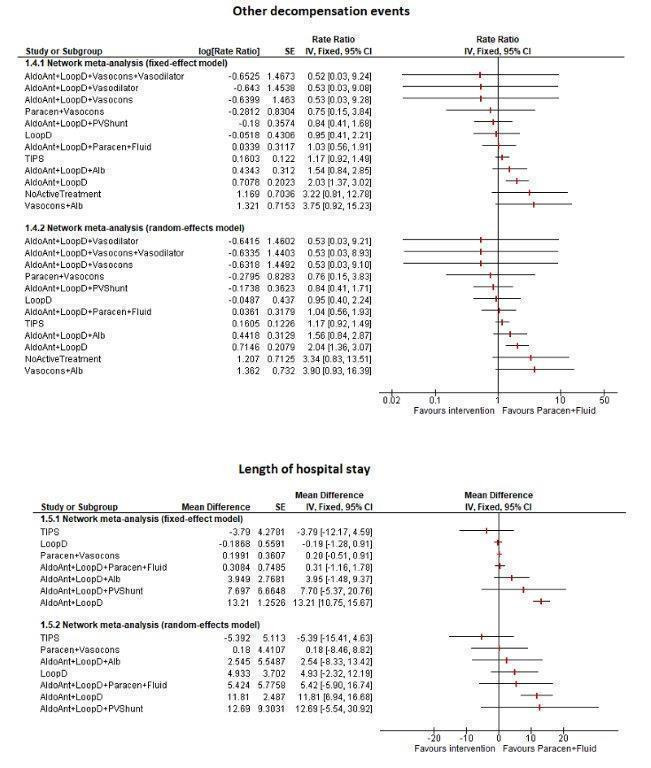

Approximately 36.8% of participants who received paracentesis plus fluid replacement (reference group, the current standard treatment) died within 11 months. There was no evidence of differences in mortality, adverse events, or liver transplantation in people receiving different interventions compared to paracentesis plus fluid replacement (very low‐certainty evidence). Resolution of ascites at maximal follow‐up was higher with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (HR 9.44; 95% CrI 1.93 to 62.68) and adding aldosterone antagonists to paracentesis plus fluid replacement (HR 30.63; 95% CrI 5.06 to 692.98) compared to paracentesis plus fluid replacement (very low‐certainty evidence). Aldosterone antagonists plus loop diuretics had a higher rate of other decompensation events such as hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, and variceal bleeding compared to paracentesis plus fluid replacement (rate ratio 2.04; 95% CrI 1.37 to 3.10) (very low‐certainty evidence).

None of the trials using paracentesis plus fluid replacement reported health‐related quality of life or symptomatic recovery from ascites.

Funding: the source of funding for four trials were industries which would benefit from the results of the study; 24 trials received no additional funding or were funded by neutral organisations; and the source of funding for the remaining 21 trials was unclear.

Authors' conclusions

Based on very low‐certainty evidence, there is considerable uncertainty about whether interventions for ascites in people with decompensated liver cirrhosis decrease mortality, adverse events, or liver transplantation compared to paracentesis plus fluid replacement in people with decompensated liver cirrhosis and ascites. Based on very low‐certainty evidence, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt and adding aldosterone antagonists to paracentesis plus fluid replacement may increase the resolution of ascites compared to paracentesis plus fluid replacement. Based on very low‐certainty evidence, aldosterone antagonists plus loop diuretics may increase the decompensation rate compared to paracentesis plus fluid replacement.

Plain language summary

Treatments for ascites in people with advanced liver disease

What is the aim of this Cochrane review? To find out the best available treatment for ascites (abnormal build‐up of fluid in the tummy) in people with advanced liver disease (liver cirrhosis, or late‐stage scarring of the liver with complications). People with cirrhosis and ascites are at significant risk of death. Therefore, it is important to treat such people, but the benefits and harms of different treatments available are currently unclear. The authors of this review collected and analysed all relevant research studies with the aim of finding what the best treatment is. They found 49 randomised controlled trials (studies where participants are randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups). During analysis of data, authors used standard Cochrane methods, which allow comparison of only two treatments at a time. Authors also used advanced techniques that allow comparison of multiple treatments simultaneously (usually referred as 'network (or indirect) meta‐analysis').

Date of literature search May 2019

Key messages None of the studies were conducted without flaws, and because of this, there is very high uncertainty in the findings. Approximately one in three trial participants with cirrhosis and ascites who received the standard treatment of drainage of fluid (paracentesis) plus fluid replacement died within 11 months of treatment. The funding source for the research was unclear in 21 studies; commercial organisations funded four studies. There were no concerns regarding the source of funding for the remaining 24 trials.

What was studied in the review? This review looked at adults of any sex, age, and ethnic origin, with advanced liver disease due to various causes and ascites. Participants were given different treatments for ascites. The authors excluded studies in people who had previously had liver transplantation. The average age of participants, when reported, ranged from 43 to 64 years. The treatments used in the trials included paracentesis plus fluid replacement (currently considered the standard treatment), different classes of diuretics (drugs which increase the passing of urine), and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (an artificial channel that connects the different blood vessels that carry oxygen‐depleted blood (venous system)) within the liver to reduce the pressure built‐up in the portal venous system, one of the two venous systems draining the liver. The review authors wanted to gather and analyse data on death (percentage dead at maximal follow‐up), quality of life, serious and non‐serious adverse events, time to liver transplantation, resolution of ascites, and development of other complications of advanced liver disease. What were the main results of the review? The 49 studies included a small number of participants (3521 participants). Study data were sparse. Forty‐two studies with 2870 participants provided data for analyses. The follow‐up of the trial participants ranged from less than a week to seven years. The review shows that there is low‐ or very low‐certainty evidence for the following:

‐ Approximately one in three people with cirrhosis and ascites who received the standard treatment of drainage of fluid (paracentesis) plus fluid replacement died within 11 months. ‐ None of the interventions decrease percentage of deaths, number of complications, and liver transplantation compared to paracentesis plus fluid replacement. ‐ Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt may be nine times more effective in resolution of ascites compared to paracentesis plus fluid replacement. ‐ Adding aldosterone antagonists (a class of diuretics) may be 30 times more effective in resolution of ascites compared to paracentesis plus fluid replacement. ‐ Using aldosterone antagonists plus loop diuretics (another class of diuretics) as a substitute for paracentesis plus fluid replacement may double the development of other liver complications of cirrhosis. ‐ None of the trials that compared other treatments to paracentesis plus fluid replacement reported health‐related quality of life or symptomatic recovery from ascites. ‐ Future well designed trials are needed to find out the best treatment for people with cirrhosis and ascites.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Liver cirrhosis

The liver is a complex organ with multiple functions including carbohydrate metabolism, fat metabolism, protein metabolism, drug metabolism, synthetic functions, storage functions, digestive functions, excretory functions, and immunological functions (Read 1972). Liver cirrhosis is a liver disease in which the normal microcirculation, the gross vascular anatomy, and the hepatic architecture have been variably destroyed and altered with fibrous septa surrounding regenerated or regenerating parenchymal nodules (Tsochatzis 2014; NCBI 2018a). The major causes of liver cirrhosis include excessive alcohol consumption, viral hepatitis, non‐alcohol‐related fatty liver disease, autoimmune liver disease, and metabolic liver disease (Williams 2014; Ratib 2015; Setiawan 2016). The global prevalence of liver cirrhosis is difficult to estimate as most estimates correspond to chronic liver disease (which includes liver fibrosis and liver cirrhosis). In studies from the USA, the prevalence of chronic liver disease varies between 0.3% to 2.1% (Scaglione 2015; Setiawan 2016); in the UK, the prevalence was 0.1% in one study (Fleming 2008). In 2010, liver cirrhosis was responsible for an estimated 2% of all global deaths, equivalent to one million deaths (Mokdad 2014). There is an increasing trend of cirrhosis‐related deaths in some countries, such as the UK, while there is a decreasing trend in other countries, such as France (Mokdad 2014; Williams 2014). The major cause of complications and deaths in people with liver cirrhosis is due to the development of clinically significant portal hypertension (hepatic venous pressure gradient at least 10 mmHg) (De Franchis 2015). Some of the clinical features of decompensation include jaundice, coagulopathy, ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, and renal failure (De Franchis 2015; McPherson 2016; EASL 2018). Decompensated cirrhosis is the most common indication for liver transplantation (Merion 2010; Adam 2012).

Ascites

Ascites is accumulation of free fluid in the abdomen (peritoneal cavity) (NCBI 2018b), and is a feature of liver decompensation (Tsochatzis 2017). Approximately 20% of people with cirrhosis have ascites (D'Amico 2014). Approximately 1% to 4% of people with cirrhosis develop ascites each year (D'Amico 2006; D'Amico 2014). Ascites is the first sign of liver decompensation in about a third of people with compensated liver cirrhosis (D'Amico 2014). Ascites can be graded as grade 1 ascites, which is mild ascites only detectable by ultrasound examination; grade 2 or moderate ascites which is manifested by moderate symmetrical distension of the abdomen; and grade 3 ascites which is large or gross ascites with marked abdominal distension (Arroyo 1996; Moore 2003). Grade 3 ascites is also called 'tense' ascites (Arroyo 1996). Ascites that is refractory to medical treatment is called 'refractory' ascites (Arroyo 1996; Moore 2003). Table 3 provides detailed criteria for the definition of refractory ascites (Moore 2003).

1. Revised 'International Ascites Club' criteria for refractory ascites.

| 1. Treatment duration: patients must be on intensive diuretic therapy (spironolactone 400 mg/day and furosemide 160 mg/day) for at least 1 week and on a salt‐restricted diet of less than 90 mmol or 5.2 g of salt/day |

| 2. Lack of response: mean weight loss of less than 0.8 kg over 4 days and urinary sodium output less than the sodium intake |

| 3. Early ascites recurrence: reappearance of grade 2 or 3 ascites within 4 weeks of initial mobilisation |

4. Diuretic‐induced complications:

|

From: Moore 2003.

In people with cirrhosis, the onset of ascites and treatment of ascites result in a decrease in health‐related quality of life (Kim 2006; Les 2010; Orr 2014). Resolution of ascites may result in improvement in health‐related quality of life in people with ascites (Orr 2014). The one‐year mortality in people with liver cirrhosis and ascites is 20%, which increases to 57% in those with ascites and variceal bleeding (D'Amico 2006). Management of ascites and its complications involve significant resources. One study reported that people with liver cirrhosis and ascites required on average one hospital admission per month and a 10‐day stay in hospital per month (Fagan 2014).

Pathophysiology of ascites

The exact mechanism by which ascites develops in people with liver cirrhosis is unknown. Portal hypertension causes arterial vasodilatation of the splanchnic circulation (dilation of the blood vessels supplying the digestive organs in the abdomen such as liver, pancreas, and intestines) (Ginès 2009; Moore 2013). This activates the renin–angiotensin system (Ginès 2009; Moore 2013), leading to fluid retention (Moore 2013). In addition, the vessel wall permeability is increased due to the pathological increase in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Colle 2008), and the oncotic pressure is decreased due to decreased albumin synthesis by the diseased liver leading to leaky splanchnic blood vessels in people with portal hypertension (Moore 2013). This results in fluid accumulation in the peritoneal cavity, that is, ascites (Moore 2013).

Description of the intervention

Although people with cirrhosis and grade 2 ascites, grade 3 ascites, and refractory ascites should be considered for liver transplantation (EASL 2010; Runyon 2013; EASL 2016; EASL 2018), cirrhotic ascites alone without other features of end‐stage liver disease, such as jaundice, variceal bleeding, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, or hepatorenal syndrome, are usually treated using less invasive methods than liver transplantation (EASL 2010). According to the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines, grade 1 ascites does not require any specific treatment; grade 2 requires salt‐restricted diet and diuretics; and grade 3 requires large volume paracentesis (removal of several litres of ascitic fluid) along with salt‐restricted diet and diuretics (EASL 2010; Runyon 2013; EASL 2018).

In people with diuretic‐refractory ascites, paracentesis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) are the main treatments according to EASL and AASLD guidelines (EASL 2010; Runyon 2013; EASL 2018). In addition, AASLD guidelines suggests that midodrine (a vasoconstrictor) should be considered in people with refractory ascites (Runyon 2013), while midodrine is not recommended by EASL guidelines (EASL 2018).

The role of vasoconstrictors, spontaneous ultrafiltration and reinfusion (filter the removed ascitic fluid and reinfuse the proteins), and low‐flow ascites fluid pump (automatically diverts ascitic fluid to the urinary bladder, from where it is excreted in urine) in the treatment of people with ascites is unclear and neither EASL nor AASLD guidelines recommend their routine use (EASL 2010; Runyon 2013). Surgical portosystemic shunts are currently recommended only in people with refractory ascites unsuitable for TIPS, repeated paracentesis, or liver transplantation (Runyon 2013).

How the intervention might work

Diuretics increase fluid excretion, thereby decreasing the fluid accumulation: fluid accumulation is one of the mechanisms of developing ascites, and decreasing fluid accumulation can lead to resolution of ascites. Systemic vasoconstrictor drugs decrease the splanchnic vasodilation which is another mechanism of developing ascites.

Paracentesis involves removing the ascitic fluid. Removal of up to 5 litres of fluid in one session of paracentesis is unlikely to cause circulatory shock (EASL 2010; Runyon 2013), but removal of more than this volume can lead to circulatory shock. Various methods to try to overcome this are to administer albumin, colloids such as hydroxyethyl starch, vasoconstrictors such as midodrine, or reinfusing the proteins from the ascitic fluid into systemic circulation (Bruno 1992; Altman 1998; Appenrodt 2008). However, the benefits of plasma expanders for people with cirrhosis and large ascites treated with abdominal paracentesis is questionable (Simonetti 2019).

TIPS procedures and other surgical forms of portosystemic shunt are aimed at decreasing portal venous pressure, the major cause of ascites in people with liver cirrhosis.

Why it is important to do this review

It is important to provide optimal treatment to people with ascites to improve their survival and health‐related quality of life. Several different treatments are available, but their relative efficacy and optimal combinations are not known. One Cochrane Review on TIPS versus paracentesis for people with cirrhosis with refractory ascites was available at the start of this project (Saab 2006); however, to date, there have not been any network meta‐analyses on the topic. Network meta‐analysis allows for a combination of direct and indirect evidence and the ranking of different interventions for different outcomes (Salanti 2011; Salanti 2012). With this systematic review and network meta‐analysis, we provide the best level of evidence for the benefits and harms of different treatments for ascites in people with decompensated liver cirrhosis. We have also presented results from direct comparisons whenever possible, as well as performing the network meta‐analysis.

Objectives

To compare the benefits and harms of different treatments for ascites in people with decompensated liver cirrhosis through a network meta‐analysis and to generate rankings of the different treatments for ascites according to their safety and efficacy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered only randomised clinical trials (including cross‐over, cluster‐randomised clinical trials) for this network meta‐analysis irrespective of language, publication status, or date of publication. We excluded studies of other designs because of the risk of bias in such studies. Inclusion of indirect observational evidence could weaken our network meta‐analysis, but this could also be viewed as a strength for assessing rare adverse events. It is well‐established that exclusion of non‐randomised studies increases the focus on potential benefits and reduces the focus on the risks of serious adverse events and those of any adverse events. However, we did not include these studies because of the findings of this review, i.e. there is considerable uncertainty about the benefits of the different treatments for ascites.

Types of participants

We included randomised clinical trials with adult trial participants (18 years old and above) undergoing treatment for ascites with decompensated liver cirrhosis. We excluded randomised clinical trials in which participants had previously undergone liver transplantation.

Types of interventions

We included any of the following treatments for comparison with one another, either alone or in combination.

Diuretics (different classes of diuretics based on their mechanism of action will be treated as separate interventions, for example, loop diuretics such as furosemide, torsemide; aldosterone antagonists such as spironolactone or potassium canrenoate);

Large volume paracentesis (removal of ascitic fluid) with different fluids to prevent circulatory dysfunction (for example, albumin, hydroxyethyl starch, etc.) ('paracentesis plus fluid replacement');

Spontaneous ultrafiltration and reinfusion (filtering the removed ascitic fluid and reinfusing the proteins);

Low‐flow ascites fluid pump (automatic diversion of ascitic fluid to the urinary bladder, from where it is excreted in urine);

Systemic vasoconstrictor (for example, terlipressin, midodrine);

TIPS procedure (decrease in portal hypertension);

Other forms of portosystemic shunt (decrease in portal hypertension);

No active intervention (no ascites‐related intervention or placebo).

We considered 'paracentesis plus fluid replacement' as the reference group. Each of the above categories was considered as a 'treatment node'; the only exception was the diuretics, where we considered different classes of diuretics as different treatment nodes. We considered variations in drugs within the same class of diuretics, doses of drugs, frequency and duration of interventions as the same treatment node. We treated each different combination of the categories as different treatment nodes.

We excluded trials that evaluated co‐interventions such as fluid restriction, restricted‐salt diet, or drugs such as vasopressin‐antagonists which are used as supplements to diuretics to overcome their adverse effects such as hyponatraemia. However, we included trials in which such co‐interventions were administered equally in both trial arms.

We evaluated the plausibility of the network meta‐analysis transitivity assumption by looking at the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the studies. The transitivity assumption means that participants included in the different trials with different treatments (in this case, ascites) can be considered to be a part of a multi‐arm randomised clinical trial and could potentially have been randomised to any of the interventions (Salanti 2012). In other words, any participant that meets the inclusion criteria is, in principle, equally likely to be randomised to any of the above eligible interventions. This necessitates that information on potential effect‐modifiers such as grade of ascites (grade 2 ascites, grade 3 ascites, or refractory ascites) are the same across trials. We performed separate meta‐analysis for each of these different types of ascites, when possible, to ensure that the concerns about the transitivity assumption were minimised.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality at maximal follow‐up, i.e. the outcome measured at the last time when the participant was followed up (time‐to‐death).

Health‐related quality of life using a validated scale such as the EQ‐5D or 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36) at maximal follow‐up (EuroQol 2018; Optum 2018).

-

Serious adverse events (during or within six months after cessation of the intervention). We defined a serious adverse event as any event that would increase mortality; is life‐threatening; requires hospitalisation; results in persistent or significant disability; is a congenital anomaly/birth defect; or any important medical event that might jeopardise the person or require intervention to prevent it (ICH‐GCP 1997). However, none of the trial authors defined serious adverse events. Therefore, we used the list provided by trial authors for serious adverse events (as indicated in the protocol).

proportion of people with one or more serious adverse events;

number of serious adverse events per participant.

Secondary outcomes

-

Any adverse events (during or within six months after cessation of the intervention): We defined an adverse event as any untoward medical occurrence not necessarily having a causal relationship with the intervention but resulting in a dose reduction or discontinuation of the intervention (any time after commencement of the intervention) (ICH‐GCP 1997). However, none of the trial authors defined 'adverse event'. Therefore, we used the list provided by trial authors for adverse events (as indicated in the protocol).

proportion of people with one or more adverse events;

number of any adverse events per participant.

Time‐to‐liver transplantation (maximal follow‐up).

-

Time‐to‐resolution of ascites (however defined by authors at maximal follow‐up):

symptomatic recovery;

resolution as per ultrasound.

Number of decompensation episodes (maximal follow‐up).

Exploratory outcomes

Length of hospital stay (all hospital admissions until maximal follow‐up).

Number of days of lost work (in people who work) (maximal follow‐up).

Treatment costs (including the cost of the treatment and any resulting complications).

We chose the outcomes of this review based on their importance to patients in a survey related to research priorities for people with liver diseases (Gurusamy 2019), based on feedback of the patient and public representative of this project, and based on an online survey about the outcomes promoted through the Cochrane Consumer Network.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE Ovid, Embase Ovid, and Science Citation Index Expanded (Web of Science) from inception to date of search for randomised clinical trials comparing two or more of the above interventions without applying any language restrictions (Royle 2003). We searched for all possible comparisons formed by the interventions of interest. To identify further ongoing or completed trials, we also searched clinicaltrials.gov, and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) which searches various trial registers, including ISRCTN and ClinicalTrials.gov. We also searched the European Medical Agency (EMA) (www.ema.europa.eu/ema/) and USA Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (www.fda.gov) registries for randomised clinical trials. We provided the search strategies along with the date of search in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched the references of the identified trials and the existing Cochrane Reviews on ascites in liver cirrhosis to identify additional trials for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (KG and AB, DR, LP, or MP) independently identified trials for inclusion by screening the titles and abstracts of articles identified by the literature search, and sought full‐text articles of any references identified by at least one review author for potential inclusion. We selected trials for inclusion based on the full‐text articles. We listed the references that we excluded and the reasons for their exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We also listed any ongoing trials identified primarily through the search of the clinical trial registers for further follow‐up. We resolved any discrepancies through discussion. We illustrated the study selection process in a PRISMA diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (KG and AB, DR, LP, or MP) independently extracted the following data onto a pre‐piloted Microsoft Excel‐based data extraction form (after translation of non‐English articles).

-

Outcome data (for each outcome and for each intervention group, whenever applicable):

number of participants randomised;

number of participants included for the analysis;

number of participants with events for binary outcomes, mean and standard deviation for continuous outcomes, number of events and the mean follow‐up period for count outcomes, and number of participants with events and the mean follow‐up period for time‐to‐event outcomes;

natural logarithm of the hazard ratio and its standard error if this was reported rather than the number of participants with events and the mean follow‐up period for time‐to‐event outcomes;

definition of outcomes or scale used, if appropriate.

-

Data on potential effect modifiers:

participant characteristics such as age, sex, grade of ascites, whether refractory or recurrent ascites, the aetiology for cirrhosis, and the interval between diagnosis of ascites and treatment;

details of the intervention and control (including dose, frequency, and duration);

length of follow‐up;

information related to 'Risk of bias' assessment (please see below).

-

Other data:

year and language of publication;

country in which the participants were recruited;

year(s) in which the trial was conducted;

inclusion and exclusion criteria.

We collected outcomes at maximum follow‐up, but also at short‐term (up to three months) and medium‐term (from three months to five years) if this was available.

We attempted to contact the trial authors in the case of unclear or missing information. We resolved any differences in opinion through discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We followed the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) to assess the risk of bias in the included trials. Specifically, we assessed sources of bias as defined below (Schulz 1995; Moher 1998; Kjaergard 2001; Wood 2008; Savović 2012a; Savović 2012b; Savović 2018).

Allocation sequence generation

Low risk of bias: sequence generation was achieved using computer random number generation or a random number table. Drawing lots, tossing a coin, shuffling cards, and throwing dice were adequate if performed by an independent person not otherwise involved in the trial.

Unclear risk of bias: the method of sequence generation was not specified.

High risk of bias: the sequence generation method was not random or only quasi‐randomised. We excluded such quasi‐randomised studies.

Allocation concealment

Low risk of bias: the allocation sequence was described as unknown to the investigators. Hence, the participants' allocations could not have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment. Allocation was controlled by a central and independent randomisation unit, an onsite locked computer, identical‐looking numbered sealed opaque envelopes, drug bottles or containers prepared by an independent pharmacist, or an independent investigator.

Unclear risk of bias: it was unclear if the allocation was hidden or if the block size was relatively small and fixed so that intervention allocations may have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment.

High risk of bias: the allocation sequence was likely to be known to the investigators who assigned the participants. We excluded such quasi‐randomised studies.

Blinding of participants and personnel

Low risk of bias: blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and it was unlikely that the blinding could have been broken; or rarely no blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judged that the outcome was not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Unclear risk of bias: any of the following: insufficient information to permit judgement of 'low risk' or 'high risk'; or the trial did not address this outcome.

High risk of bias: any of the following: no blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome was likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; or blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome was likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinded outcome assessment

Low risk of bias: blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken; or rarely no blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judged that the outcome measurement was not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Unclear risk of bias: any of the following: insufficient information to permit judgement of 'low risk' or 'high risk'; or the trial did not address this outcome.

High risk of bias: any of the following: no blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement was likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; or blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement was likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Low risk of bias: missing data were unlikely to make treatment effects depart from plausible values. The study used sufficient methods, such as multiple imputation, to handle missing data.

Unclear risk of bias: there was insufficient information to assess whether missing data in combination with the method used to handle missing data were likely to induce bias on the results.

High risk of bias: the results were likely to be biased due to missing data.

Selective outcome reporting

Low risk of bias: the trial reported the following predefined outcomes: all‐cause mortality, adverse events, and time to resolution of ascites. If the original trial protocol was available, the outcomes should have been those called for in that protocol. If we obtained the trial protocol from a trial registry (e.g. ClinicalTrials.gov), the outcomes sought should have been those enumerated in the original protocol if the trial protocol was registered before or at the time that the trial was begun. If the trial protocol was registered after the trial was begun, we did not consider those outcomes to be reliable.

Unclear risk of bias: not all predefined, or clinically relevant and reasonably expected, outcomes were reported fully, or it was unclear whether data on these outcomes were recorded or not.

High risk of bias: one or more predefined or clinically relevant and reasonably expected outcomes were not reported, despite the fact that data on these outcomes should have been available and even recorded.

Other bias

Low risk of bias: the trial appeared to be free of other components that could put it at risk of bias (e.g. inappropriate control or dose or administration of control, baseline differences, early stopping).

Uncertain risk of bias: the trial may or may not have been free of other components that could put it at risk of bias.

High risk of bias: there were other factors in the trial that could put it at risk of bias (e.g. baseline differences, early stopping).

We considered a trial to be at low risk of bias if we assessed the trial to be at low risk of bias across all listed bias risk domains. Otherwise, we considered trials to be at high risk of bias. At the outcome level, we classified an outcome to be at low risk of bias if the allocation sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, healthcare professionals, and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting (at the outcome level) were at low risk of bias for objective and subjective outcomes (Savović 2018).

Measures of treatment effect

Relative treatment effects

For dichotomous variables (e.g. proportion of participants with serious adverse events or any adverse events), we calculated the odds ratio (OR) with 95% credible interval (CrI) (or Bayesian confidence interval) (Severini 1993). For continuous variables (e.g. health‐related quality of life reported on the same scale), we calculated the mean difference (MD) with 95% Crl. We planned to use standardised mean difference (SMD) values with 95% Crl for health‐related quality of life if included trials used different scales. If we calculated the SMD, we planned to convert it to a common scale, for example, EQ‐5D or SF‐36 (using the standard deviation of the common scale) for the purpose of interpretation. For count outcomes (e.g. number of serious adverse events or number of any adverse events), we calculated the rate ratio (RaR) with 95% Crl. This assumes that the events are independent of each other, i.e. if a person has had an event, they are not at an increased risk of further outcomes, which is the assumption in Poisson likelihood. For time‐to‐event data (e.g. all‐cause mortality at maximal follow‐up), we calculated hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% Crl.

Relative ranking

We estimated the ranking probabilities for all interventions of being at each possible rank for each intervention for each outcome when NMA (network meta‐analysis) was performed. We obtained the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) (cumulative probability), rankogram, and relative ranking table with CrI for the ranking probabilities for each outcome when NMA was performed (Salanti 2011; Chaimani 2013).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participant undergoing treatment for ascites according to the intervention group to which the participant was randomly assigned.

Cluster‐randomised clinical trials

If we identified any cluster‐randomised clinical trials, we planned to include cluster‐randomised clinical trials, provided that the effect estimate adjusted for cluster correlation was available or if there was sufficient information available to calculate the design effect (which would allow us to take clustering into account). We also planned to assess additional domains of risk of bias for cluster‐randomised trials according to guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Cross‐over randomised clinical trials

If we identified any cross‐over randomised clinical trials, we planned to include only the outcomes after the period of the first intervention because the included treatments could have residual effects.

Trials with multiple intervention groups

We collected data for all trial intervention groups that met the inclusion criteria. The codes that we used for analysis accounted for the correlation between the effect sizes from studies with more than two groups.

Dealing with missing data

We performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis, whenever possible (Newell 1992); otherwise, we used the data available to us. When intention‐to‐treat analysis was not used and the data were not missing at random (for example, treatment was withdrawn due to adverse events or duration of treatment was shortened because of lack of response and such participants were excluded from analysis), this could lead to biased results; therefore, we conducted best‐worst case scenario analysis (assuming a good outcome in the intervention group and bad outcome in the control group) and worst‐best case scenario analysis (assuming a bad outcome in the intervention group and good outcome in the control group) as sensitivity analyses, whenever possible, for binary and time‐to‐event outcomes, where binomial likelihood was used.

For continuous outcomes, we imputed the standard deviation from P values, according to guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If the data were likely to be normally distributed, we used the median for meta‐analysis when the mean was not available; otherwise, we planned to simply provide a median and interquartile range of the difference in medians. If it was not possible to calculate the standard deviation from the P value or the confidence intervals, we planned to impute the standard deviation using the largest standard deviation in other trials for that outcome. This form of imputation can decrease the weight of the study for calculation of mean differences and may bias the effect estimate to no effect for calculation of standardised mean differences (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical and methodological heterogeneity by carefully examining the characteristics and design of included trials. We also planned to assess the presence of clinical heterogeneity by comparing effect estimates (please see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity) in trial reports of different drug dosages, different grades of ascites (grade 2 or grade 3), refractory or recurrent ascites, different aetiologies for cirrhosis (for example, alcohol‐related liver disease, viral liver diseases, autoimmune liver disease), and based on the co‐interventions (for example, both groups receive prophylactic antibiotics to decrease the risk of subacute bacterial peritonitis). Different study designs and risk of bias can contribute to methodological heterogeneity.

We assessed statistical heterogeneity by comparing the results of the fixed‐effect model meta‐analysis and the random‐effects model meta‐analysis, between‐study standard deviation (tau2 and comparing this with values reported in a study of the distribution of between‐study heterogeneity estimates) (Turner 2012), and by calculating the NMA‐specific I2 statistic (Jackson 2014) using Stata/SE 15.1. When possible, we explored substantial clinical, methodological, or statistical heterogeneity and addressed the heterogeneity in subgroup analysis (see 'Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity').

Assessment of transitivity across treatment comparisons

We assessed the transitivity assumption by comparing the distribution of the potential effect modifiers (clinical: grade of ascites (grade 2 versus grade 3) and whether refractory or recurrent ascites; and methodological: risk of bias, year of randomisation, duration of follow‐up) across the different pairwise comparisons.

Assessment of reporting biases

For the network meta‐analysis, we planned to perform a comparison‐adjusted funnel plot. However, to interpret a comparison‐adjusted funnel plot, it is necessary to rank the studies in a meaningful way as asymmetry may be due to small sample sizes in newer studies (comparing newer treatments with older treatments) or higher risk of bias in older studies (Chaimani 2012). As there was no meaningful way in which to rank these studies (i.e. there was no specific change in the risk of bias in the studies, sample size, or the control group used over time), we judged the reporting bias by the completeness of the search (Chaimani 2012). We also considered lack of reporting of outcomes as a form of reporting bias.

Data synthesis

Methods for indirect and mixed comparisons

We conducted network meta‐analyses to compare multiple interventions simultaneously for each of the primary and secondary outcomes. When two or more interventions were combined, we considered this as a separate intervention ('node'). Network meta‐analysis combines direct evidence within trials and indirect evidence across trials (Mills 2012). We obtained a network plot to ensure that the trials were connected by interventions using Stata/SE 15.1 (Chaimani 2013). We excluded any trials that were not connected to the network from the network meta‐analysis, and we reported only the direct pairwise meta‐analysis for such comparisons. We summarised the population and methodological characteristics of the trials included in the network meta‐analysis in a table based on pairwise comparisons. We conducted a Bayesian network meta‐analysis using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method in OpenBUGS 3.2.3, according to guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Decision Support Unit (DSU) documents (Dias 2016). We modelled the treatment contrast (i.e. log odds ratio for binary outcomes, mean difference or standardised mean difference for continuous outcomes, log rate ratio for count outcomes, and log hazard ratio for time‐to‐event outcomes) for any two interventions ('functional parameters') as a function of comparisons between each individual intervention and the reference group ('basic parameters') using appropriate likelihood functions and links (Lu 2006). We used binomial likelihood and logit link for binary outcomes, Poisson likelihood and log link for count outcomes, binomial likelihood and complementary log‐log link (a semiparametric model which excludes censored individuals from the denominator of ‘at risk’ individuals at the point when they are censored) for time‐to‐event outcomes, and normal likelihood and identity link for continuous outcomes. We used 'paracentesis plus fluid replacement' as the reference group across the networks, as this was the commonest intervention compared in the trials. We performed a fixed‐effect model and random‐effects model for the network meta‐analysis. We reported both models for comparison with the reference group in a forest plot when the results were different between the models. For each pairwise comparison in a table, we reported the fixed‐effect model if the two models reported similar results; otherwise, we reported the more conservative model, i.e. usually using the random‐effects model in the absence of ‘small‐study’ bias.

We used a hierarchical Bayesian model using three different sets of initial values to start the simulation‐based parameter estimation to assist with the assessment of convergence, employing codes provided by NICE DSU (Dias 2016). We used a normal distribution with large variance (10,000) for treatment effect priors (vague or flat priors) centred at no effect. For the random‐effects model, we used a prior distributed uniformly (limits: 0 to 5) for the between‐trial standard deviation parameter and assumed this variability would be the same across treatment comparisons (Dias 2016). We used a 'burn‐in' of 30,000 simulations, checked for convergence (of effect estimates and between‐study heterogeneity) visually (i.e. whether the values in different chains mixed very well by visualisation), and ran the models for another 10,000 simulations to obtain effect estimates. If we did not obtain convergence, we increased the number of simulations for the 'burn‐in' and used the 'thin' and 'over relax' functions to decrease the autocorrelation. If we still did not obtain convergence, we used alternate initial values and priors employing methods suggested by Van Valkenhoef 2012. We estimated the probability that each intervention ranked at each of the possible positions using the NICE DSU codes (Dias 2016).

Assessment of inconsistency

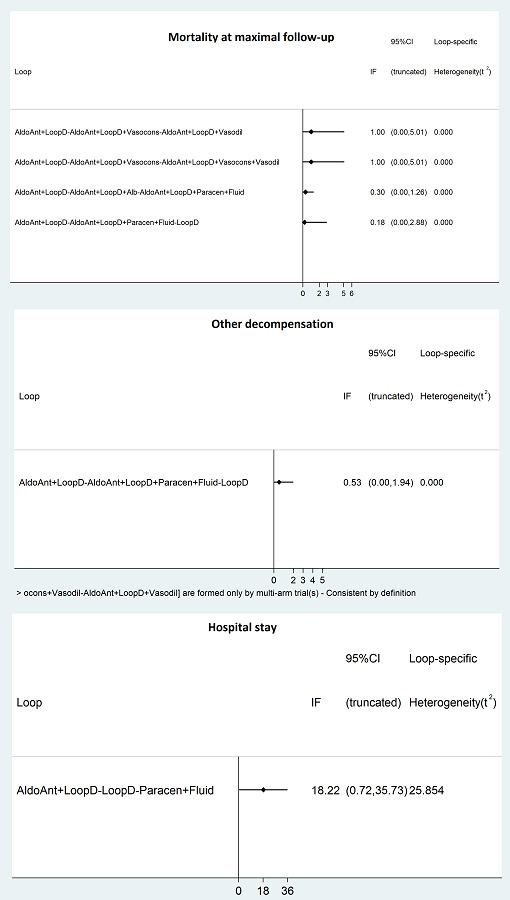

We assessed inconsistency (statistical evidence of the violation of the transitivity assumption) by fitting both an inconsistency model and a consistency model. We used inconsistency models employed in the NICE DSU manual, as we used a common between‐study standard deviation (Dias 2014). In addition, we used design‐by‐treatment full interaction model and inconsistency factor (IF) plots to assess inconsistency (Higgins 2012; Chaimani 2013), when applicable. We used Stata/SE 15.1 to create IF plots. In the presence of inconsistency, we assessed whether the inconsistency was due to clinical or methodological heterogeneity by performing separate analyses for each of the different subgroups mentioned in the Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity or limited network meta‐analysis to a more compatible subset of trials, when possible.

Direct comparison

We performed the direct comparisons using the same codes and the same technical details.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to assess the differences in the effect estimates between the following subgroups and investigated heterogeneity and inconsistency using meta‐regression with the help of the codes provided in NICE DSU guidance (Dias 2012a), if we included a sufficient number of trials (when there were at least two trials in at least two of the subgroups). We planned to use the following trial‐level covariates for meta‐regression.

Trials at low risk of bias (risk of bias in all domains were low) compared to trials at high risk of bias (risk of bias was unclear or high in at least one of the domains).

The grade of ascites (grade 2 or grade 3 or refractory/recurrent ascites).

The aetiology for cirrhosis (for example, alcohol‐related liver disease, viral liver diseases, autoimmune liver disease).

The interval between the diagnosis of ascites and the start of treatment.

The co‐interventions (for example, both groups received prophylactic antibiotics to decrease the risk of subacute bacterial peritonitis).

The period of follow‐up (short‐term: up to three months, medium‐term: more than three months to five years, long‐term: more than five years).

The definition used by authors for serious adverse events and any adverse event (ICH‐GCP 1997 compared to other definitions).

We calculated a single common interaction term which assumes that each relative treatment effect compared to a common comparator treatment (i.e. paracentesis plus fluid replacement) is impacted in the same way by the covariate in question, when applicable (Dias 2012a). If the 95% Crl of the interaction term did not overlap zero, we considered this statistically significant heterogeneity or inconsistency (depending upon the factor being used as covariate).

Sensitivity analysis

If there were post‐randomisation dropouts, we reanalysed the results using the best‐worst case scenario and worst‐best case scenario analyses as sensitivity analyses whenever possible. We also performed a sensitivity analysis excluding the trials in which mean or standard deviation, or both, were imputed, and we used the median standard deviation in the trials to impute missing standard deviations.

Presentation of results

We followed the PRISMA‐NMA statement while reporting (Hutton 2015). We presented the effect estimates with 95% CrI for each pairwise comparison calculated from the direct comparisons and network meta‐analysis. We originally planned to present the cumulative probability of the treatment ranks (i.e. the probability that the intervention was within the top two, the probability that the intervention was within the top three, etc) but we did not present these because of the sparse data which can lead to misinterpretation of results due to large uncertainty in the rankings (the CrI was 0 to 1 for all the ranks) in graphs (SUCRA) (Salanti 2011). We plotted the probability that each intervention was best, second best, third best, etc. for each of the different outcomes (rankograms), which are generally considered more informative (Salanti 2011; Dias 2012b), but we did not present these because of the sparse data which can lead to misinterpretation of results due to large uncertainty in the rankings (the CrI was 0 to 1 for all the ranks). We uploaded all the raw data and the codes used for analysis in the European Organization for Nuclear Research open source database (Zenodo): the link is: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3531818.

Grading of evidence

We presented 'Summary of findings' tables for all the primary and secondary outcomes (see Primary outcomes; Secondary outcomes). We followed the approach suggested by Yepes‐Nunez and colleagues (Yepes‐Nunez 2019). First, we calculated the direct and indirect effect estimates (when possible) and 95% Crl using the node‐splitting approach (Dias 2010), that is, calculating the direct estimate for each comparison by including only trials in which there was direct comparison of interventions and the indirect estimate for each comparison by excluding the trials in which there was direct comparison of interventions (and ensuring a connected network). Next, we rated the quality of direct and indirect effect estimates using GRADE methodology which takes into account the risk of bias, inconsistency (heterogeneity), directness of evidence (including incoherence, the term used in GRADE methodology for inconsistency in network meta‐analysis), imprecision, and publication bias (Guyatt 2011). We then presented the relative and absolute estimates of the meta‐analysis with the best certainty of evidence (Yepes‐Nunez 2019). We also presented the 'Summary of findings' tables in a second format presenting all the outcomes for selected interventions (Yepes‐Nunez 2019): we selected the four interventions (aldosterone antagonists plus loop diuretics, paracentesis plus systemic vasoconstrictors, aldosterone antagonists plus loop diuretics plus paracentesis plus fluid replacement, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt) which were compared in the most trials (Table 3).

Recommendations for future research

We provided recommendations for future research in the population, intervention, control, outcomes, period of follow‐up, and study design, based on the uncertainties that we identified from the existing research.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

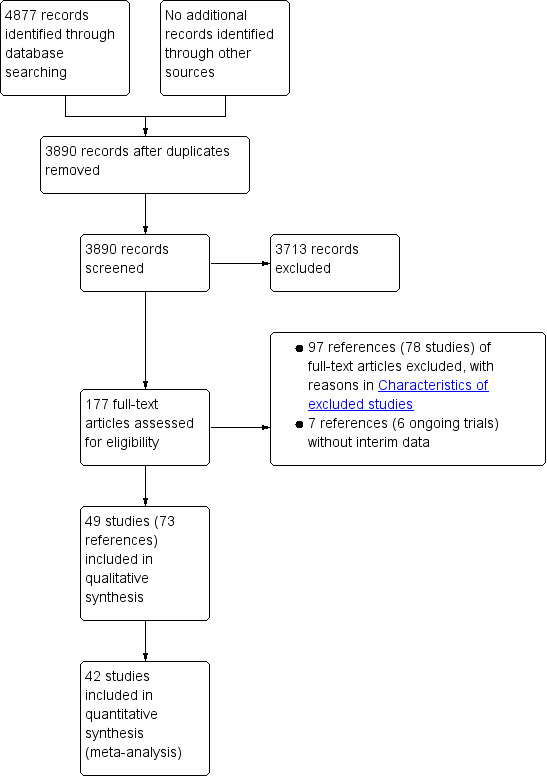

We identified 4877 references through electronic searches of CENTRAL (n = 1095), MEDLINE Ovid (n = 2093), Embase Ovid (n = 875), Science Citation Index expanded (n = 779), ClinicalTrials.gov (n = 35), and WHO Trials register (n = 0). After removing duplicate references, there were 3890 references. We excluded 3713 clearly irrelevant references through reading titles and abstracts. We identified no additional references by reference searching and by searching the EMA and FDA. We retrieved a total of 177‐full text references for further assessment in detail. We excluded 97 references (78 studies) for the reasons stated in the Characteristics of excluded studies. There were six ongoing trials (seven references) without interim data (Characteristics of ongoing studies). Thus, we included a total of 49 trials described in 73 references (Characteristics of included studies). The reference flow is shown in Figure 2.

2.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Forty‐nine trials were included (Gregory 1977; Fogel 1981; Descos 1983; Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Mchutchison 1989; Stanley 1989b; Chesta 1990; Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Bruno 1992; Hagege 1992; Ljubici 1994; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Schaub 1995; Lebrec 1996; Chang 1997; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Graziotto 1997; Mehta 1998; Gentilini 1999a; Rossle 2000; Ginès 2002; Moreau 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Romanelli 2006; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Lata 2007; Appenrodt 2008; Singh 2008; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Raza 2011; Al Sebaey 2012; Amin 2012; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Ali 2014; Hamdy 2014; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c; Rai 2017; Caraceni 2018; Sola 2018). A total of 3521 participants were randomised to different interventions. The number of participants within each trial ranged from 20 to 440. A total of 2870 participants from 42 trials were included in one or more outcomes (Gregory 1977; Fogel 1981; Descos 1983; Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Chesta 1990; Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Hagege 1992; Ljubici 1994; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Schaub 1995; Lebrec 1996; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Graziotto 1997; Mehta 1998; Gentilini 1999a; Rossle 2000; Ginès 2002; Moreau 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Romanelli 2006; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Lata 2007; Singh 2008; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Raza 2011; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Ali 2014; Hamdy 2014; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c; Rai 2017; Caraceni 2018; Sola 2018). The mean or median age in the trials ranged from 43 to 64 years in the trials that reported this information (Gregory 1977; Fogel 1981; Descos 1983; Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Chesta 1990; Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Bruno 1992; Hagege 1992; Ljubici 1994; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Lebrec 1996; Chang 1997; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Graziotto 1997; Mehta 1998; Gentilini 1999a; Rossle 2000; Ginès 2002; Moreau 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Romanelli 2006; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Lata 2007; Appenrodt 2008; Singh 2008; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Raza 2011; Al Sebaey 2012; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Ali 2014; Hamdy 2014; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c; Rai 2017; Caraceni 2018; Sola 2018). The proportion of females ranged from 0.0% to 47.6% in the trials that reported this information (Gregory 1977; Fogel 1981; Descos 1983; Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Bruno 1992; Hagege 1992; Ljubici 1994; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Lebrec 1996; Chang 1997; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Graziotto 1997; Mehta 1998; Gentilini 1999a; Rossle 2000; Ginès 2002; Moreau 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Romanelli 2006; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Lata 2007; Appenrodt 2008; Singh 2008; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Raza 2011; Al Sebaey 2012; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Hamdy 2014; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c; Rai 2017; Caraceni 2018; Sola 2018). The follow‐up period in the trials ranged from 0.1 to 84 months in the trials that reported this information. Twenty‐eight trials had short‐term follow‐up (Gregory 1977; Fogel 1981; Descos 1983; Mchutchison 1989; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Bruno 1992; Hagege 1992; Ljubici 1994; Schaub 1995; Chang 1997; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Mehta 1998; Moreau 2002; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Lata 2007; Appenrodt 2008; Singh 2008; Licata 2009; Raza 2011; Al Sebaey 2012; Amin 2012; Singh 2013; Ali 2014; Hamdy 2014; Tuttolomondo 2016; Rai 2017); 19 trials had medium‐term follow‐up (Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Chesta 1990; Ginès 1991; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Lebrec 1996; Graziotto 1997; Gentilini 1999a; Rossle 2000; Ginès 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Narahara 2011; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a; Bureau 2017c; Caraceni 2018; Sola 2018); only two trials had long‐term follow‐up (Stanley 1989b; Romanelli 2006).

Twenty‐five trials reported the proportion of participants who had ascites grade 2: in 23 trials, none of the participants had ascites grade 2; these trials included only participants with grade 3 (Descos 1983; Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Chesta 1990; Acharya 1992; Bruno 1992; Ljubici 1994; Sola 1994; Chang 1997; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Graziotto 1997; Rossle 2000; Moreau 2002; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Lata 2007; Appenrodt 2008; Singh 2008; Al Sebaey 2012; Amin 2012; Ali 2014; Hamdy 2014; Bureau 2017c); in the remaining two trials, the proportion of participants who had ascites grade 2 ranged from 65.0% to 83.1% (Romanelli 2006; Caraceni 2018). Twenty trials reported the proportion of participants who had refractory or recurrent ascites: in 19 trials, all the participants had refractory or recurrent ascites (Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Bruno 1992; Ginès 1995; Lebrec 1996; Rossle 2000; Ginès 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Raza 2011; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Hamdy 2014; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c; Rai 2017); in the remaining trial, the proportion of participants who had refractory or recurrent ascites was 85.0% (Acharya 1992). Forty‐one trials reported the proportion of participants who had alcohol‐related cirrhosis: in two trials, none of the participants had alcohol‐related cirrhosis (Chang 1997; Raza 2011); in four trials, all the participants had alcohol‐related cirrhosis (Gregory 1977; Stanley 1989b; Ljubici 1994; Schaub 1995); in the remaining 35 trials, the proportion of participants who had alcohol‐related cirrhosis ranged from 2.0% to 90.6% (Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Chesta 1990; Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Bruno 1992; Hagege 1992; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Lebrec 1996; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Mehta 1998; Gentilini 1999a; Rossle 2000; Ginès 2002; Moreau 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Romanelli 2006; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Lata 2007; Appenrodt 2008; Singh 2008; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c; Rai 2017; Caraceni 2018; Sola 2018). Thirty‐three trials reported the proportion of participants who had viral‐related cirrhosis: in four trials, none of the participants had viral‐related cirrhosis (Gregory 1977; Stanley 1989b; Chesta 1990; Ljubici 1994); in one trial, all the participants had viral‐related cirrhosis (Chang 1997); in the remaining 28 trials, the proportion of participants who had viral‐related cirrhosis ranged from 5.6% to 95.0% (Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Bruno 1992; Ginès 1995; Schaub 1995; Lebrec 1996; Gentilini 1999a; Moreau 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Romanelli 2006; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Appenrodt 2008; Singh 2008; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Raza 2011; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c; Rai 2017; Caraceni 2018; Sola 2018). Twenty‐two trials reported the proportion of participants who had autoimmune disease‐related cirrhosis: in 17 trials, none of the participants had autoimmune disease‐related cirrhosis (Gregory 1977; Salerno 1987; Ginès 1991; Ljubici 1994; Ginès 1995; Lebrec 1996; Chang 1997; Gentilini 1999a; Moreau 2002; Romanelli 2006; Singh 2006b; Appenrodt 2008; Licata 2009; Raza 2011; Singh 2013; Tuttolomondo 2016; Rai 2017); in the remaining five trials, the proportion of participants who had autoimmune disease‐related cirrhosis ranged from 2.5% to 12.0% (Chesta 1990; Singh 2006a; Singh 2008; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a). Only two trials reported whether the participants received antibiotic prophylaxis for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (Ginès 2002; Caraceni 2018). In one trial, all participants received antibiotic prophylaxis (Ginès 2002); in the other trial, 19.3% of participants received antibiotic prophylaxis, but the reason for only a proportion of participants receiving antibiotic prophylaxis was not stated (Caraceni 2018). In 38 trials, patients with active other decompensation events such as active gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatorenal syndrome, or grade III or grade IV hepatic encephalopathy were excluded (Descos 1983; Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Chesta 1990; Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Bruno 1992; Hagege 1992; Ljubici 1994; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Lebrec 1996; Chang 1997; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Graziotto 1997; Mehta 1998; Gentilini 1999a; Ginès 2002; Moreau 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Romanelli 2006; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Singh 2008; Narahara 2011; Raza 2011; Al Sebaey 2012; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Ali 2014; Hamdy 2014; Bureau 2017c; Rai 2017; Caraceni 2018; Sola 2018). In the remaining 11 trials, it was not clear whether patients with active other decompensation events were included (Gregory 1977; Fogel 1981; Mchutchison 1989; Stanley 1989b; Schaub 1995; Rossle 2000; Lata 2007; Appenrodt 2008; Licata 2009; Amin 2012; Tuttolomondo 2016). The interval between diagnosis and treatment was not reported in any of the trials.

A total of 21 interventions were compared in these trials. Forty‐two trials (2870 participants) reported one or more outcomes for this review (Gregory 1977; Fogel 1981; Descos 1983; Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Chesta 1990; Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Hagege 1992; Ljubici 1994; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Schaub 1995; Lebrec 1996; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Graziotto 1997; Mehta 1998; Gentilini 1999a; Rossle 2000; Ginès 2002; Moreau 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Romanelli 2006; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Lata 2007; Singh 2008; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Raza 2011; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Ali 2014; Hamdy 2014; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c; Rai 2017; Caraceni 2018; Sola 2018). The important characteristics, potential effect modifiers, and follow‐up in each trial is reported in Table 4. Overall, there does not seem to be any systematic differences between the comparisons.

2. Characteristics of included studies and potential effect modifiers.

| This table is too wide to be displayed in RevMan. This table can be found at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3604600. |

Funding: the source of funding for four trials was industries who would benefit from the results of the study (Stanley 1989b; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Caraceni 2018; Sola 2018); 24 trials received no additional funding or were funded by neutral organisations with no vested interests in the results of the study (Descos 1983; Gines 1987; Ginès 1991; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Chang 1997; Gentilini 1999a; Ginès 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Romanelli 2006; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Appenrodt 2008; Singh 2008; Licata 2009; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Ali 2014; Hamdy 2014; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c; Rai 2017); the source of funding for the remaining 21 trials was unclear (Gregory 1977; Fogel 1981; Salerno 1987; Mchutchison 1989; Chesta 1990; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Bruno 1992; Hagege 1992; Ljubici 1994; Schaub 1995; Lebrec 1996; Graziotto 1997; Mehta 1998; Rossle 2000; Moreau 2002; Lata 2007; Narahara 2011; Raza 2011; Al Sebaey 2012; Amin 2012).

Excluded studies

The reasons for exclusion is provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

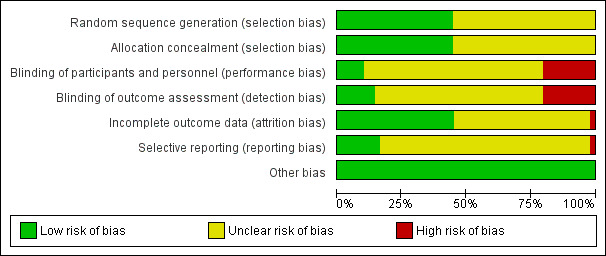

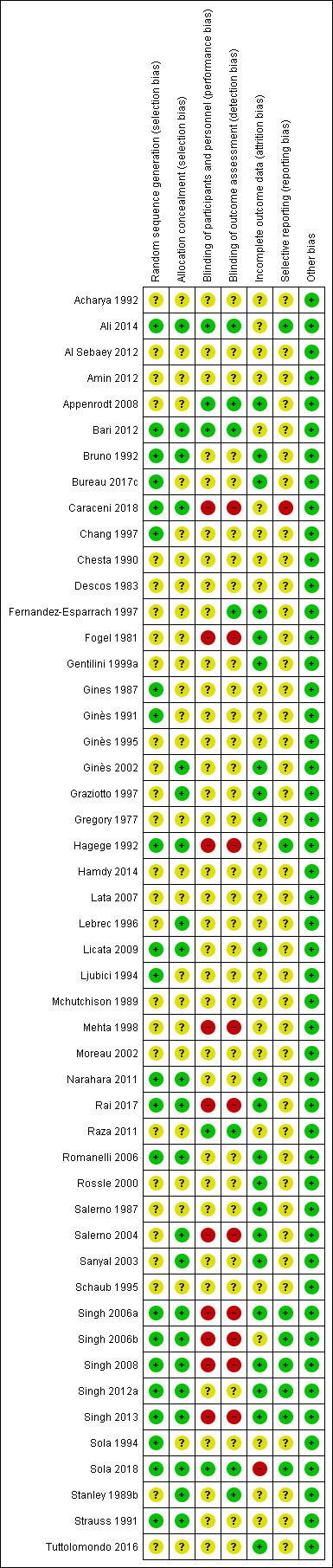

The risk of bias is summarised in Figure 3, Figure 4, and in Table 5. All the trials were at unclear or high risk of bias in at least one of the domains and were considered to be at high risk of bias overall.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3. Risk of bias.

| Study name | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of patients and healthcare providers | Blinding of outcome assessors | Missing outcome bias | Selective outcome reporting | Overall risk of bias |

| Chang 1997 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Chesta 1990 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Gines 1987 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Hagege 1992 | Low | Low | High | High | Unclear | Low | High |

| Salerno 1987 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Schaub 1995 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Al Sebaey 2012 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Appenrodt 2008 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | High |

| Bari 2012 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Hamdy 2014 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Lata 2007 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Moreau 2002 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Singh 2006a | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| Singh 2006b | Low | Low | High | High | Unclear | Low | High |

| Singh 2008 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| Ljubici 1994 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Sola 1994 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Strauss 1991 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Bureau 2017c | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Ginès 2002 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Lebrec 1996 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Narahara 2011 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Rossle 2000 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Salerno 2004 | Unclear | Low | High | High | Low | Unclear | High |

| Sanyal 2003 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Gregory 1977 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Tuttolomondo 2016 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Fogel 1981 | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Low | Unclear | High |

| Licata 2009 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Bruno 1992 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Graziotto 1997 | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Mehta 1998 | Unclear | Unclear | High | High | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Gentilini 1999a | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Romanelli 2006 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Caraceni 2018 | Low | Low | High | High | Unclear | High | High |

| Ginès 1991 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Ginès 1995 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Singh 2012a | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | High |

| Singh 2013 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | High |

| Acharya 1992 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Ali 2014 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

| Amin 2012 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Descos 1983 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Rai 2017 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Unclear | High |

| Singh 2013 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| Singh 2013 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| Singh 2013 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| Singh 2013 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| Singh 2013 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| Raza 2011 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High |

| Stanley 1989b | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | High |

| Sola 2018 | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | High |

| Mchutchison 1989 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High |

Allocation

With regards to sequence generation, twenty‐two trials were at low risk of bias (Gines 1987; Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Bruno 1992; Hagege 1992; Ljubici 1994; Sola 1994; Chang 1997; Romanelli 2006; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Singh 2008; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Ali 2014; Bureau 2017c; Rai 2017; Caraceni 2018; Sola 2018); the remaining 27 trials, which did not provide sufficient information, were at unclear risk of bias (Gregory 1977; Fogel 1981; Descos 1983; Salerno 1987; Mchutchison 1989; Stanley 1989b; Chesta 1990; Acharya 1992; Ginès 1995; Schaub 1995; Lebrec 1996; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Graziotto 1997; Mehta 1998; Gentilini 1999a; Rossle 2000; Ginès 2002; Moreau 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Lata 2007; Appenrodt 2008; Raza 2011; Al Sebaey 2012; Amin 2012; Hamdy 2014; Tuttolomondo 2016).

With regards to allocation concealment, twenty‐two trials were at low risk of bias (Stanley 1989b; Strauss 1991; Bruno 1992; Hagege 1992; Lebrec 1996; Graziotto 1997; Ginès 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Romanelli 2006; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Singh 2008; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Bari 2012; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Ali 2014; Rai 2017; Caraceni 2018; Sola 2018); the remaining 27 trials, which did not provide sufficient information, were at unclear risk of bias (Gregory 1977; Fogel 1981; Descos 1983; Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Mchutchison 1989; Chesta 1990; Ginès 1991; Acharya 1992; Ljubici 1994; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Schaub 1995; Chang 1997; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Mehta 1998; Gentilini 1999a; Rossle 2000; Moreau 2002; Lata 2007; Appenrodt 2008; Raza 2011; Al Sebaey 2012; Amin 2012; Hamdy 2014; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c).

Blinding

With regards to the blinding of patients and healthcare providers, five trials were at low risk of bias (Appenrodt 2008; Raza 2011; Bari 2012; Ali 2014; Sola 2018); 34 trials, which did not provide sufficient information, were at unclear risk of bias (Gregory 1977; Descos 1983; Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Mchutchison 1989; Stanley 1989b; Chesta 1990; Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Bruno 1992; Ljubici 1994; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Schaub 1995; Lebrec 1996; Chang 1997; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Graziotto 1997; Gentilini 1999a; Rossle 2000; Ginès 2002; Moreau 2002; Sanyal 2003; Romanelli 2006; Lata 2007; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Al Sebaey 2012; Amin 2012; Singh 2012a; Hamdy 2014; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c); the remaining 10 trials were at high risk of bias (Fogel 1981; Hagege 1992; Mehta 1998; Salerno 2004; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Singh 2008; Singh 2013; Rai 2017; Caraceni 2018).

With regards to blinding of outcome assessors, six trials were at low risk of bias (Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Appenrodt 2008; Raza 2011; Bari 2012; Ali 2014; Sola 2018); 33 trials, which did not provide sufficient information, were at unclear risk of bias (Gregory 1977; Descos 1983; Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Mchutchison 1989; Stanley 1989b; Chesta 1990; Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Bruno 1992; Ljubici 1994; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Schaub 1995; Lebrec 1996; Chang 1997; Graziotto 1997; Gentilini 1999a; Rossle 2000; Ginès 2002; Moreau 2002; Sanyal 2003; Romanelli 2006; Lata 2007; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Al Sebaey 2012; Amin 2012; Singh 2012a; Hamdy 2014; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c); the remaining 10 trials were at high risk of bias (Fogel 1981; Hagege 1992; Mehta 1998; Salerno 2004; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Singh 2008; Singh 2013; Rai 2017; Caraceni 2018).

Incomplete outcome data

With regards to incomplete data, twenty‐three trials were at low risk of bias (Gregory 1977; Fogel 1981; Salerno 1987; Stanley 1989b; Bruno 1992; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Graziotto 1997; Gentilini 1999a; Rossle 2000; Ginès 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Romanelli 2006; Singh 2006a; Appenrodt 2008; Singh 2008; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c; Rai 2017); 25 trials were at unclear risk of bias (Descos 1983; Gines 1987; Mchutchison 1989; Chesta 1990; Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Hagege 1992; Ljubici 1994; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Schaub 1995; Lebrec 1996; Chang 1997; Mehta 1998; Moreau 2002; Singh 2006b; Lata 2007; Raza 2011; Al Sebaey 2012; Amin 2012; Bari 2012; Ali 2014; Hamdy 2014; Caraceni 2018), because it was not clear whether there were post‐randomisation dropouts or whether the post‐randomisation dropouts were related to the outcomes (if there were post‐randomisation dropouts); the remaining trial was at high risk of bias (Sola 2018), as the post‐randomisation dropouts were probably related to the intervention and the outcomes.

Selective reporting

Eight trials were at low risk of selective outcome reporting bias (Hagege 1992; Singh 2006a; Singh 2006b; Singh 2008; Singh 2012a; Singh 2013; Ali 2014; Sola 2018), as the important clinical outcomes expected to be reported in such trials were reported; 40 trials were at unclear risk of selective outcome reporting bias (Gregory 1977; Fogel 1981; Descos 1983; Gines 1987; Salerno 1987; Mchutchison 1989; Stanley 1989b; Chesta 1990; Ginès 1991; Strauss 1991; Acharya 1992; Bruno 1992; Ljubici 1994; Sola 1994; Ginès 1995; Schaub 1995; Lebrec 1996; Chang 1997; Fernandez‐Esparrach 1997; Graziotto 1997; Mehta 1998; Gentilini 1999a; Rossle 2000; Ginès 2002; Moreau 2002; Sanyal 2003; Salerno 2004; Romanelli 2006; Lata 2007; Appenrodt 2008; Licata 2009; Narahara 2011; Raza 2011; Al Sebaey 2012; Amin 2012; Bari 2012; Hamdy 2014; Tuttolomondo 2016; Bureau 2017c; Rai 2017), as a protocol published prior to recruitment was not available; the remaining trial was at high risk of selective outcome reporting bias (Caraceni 2018), as adverse events were clearly collected, but not reported adequately.

Other potential sources of bias

No other bias was noted in the trials.

Effects of interventions

for the main comparison.

| Treatment for ascites in people with decompensated liver cirrhosis | ||||||||

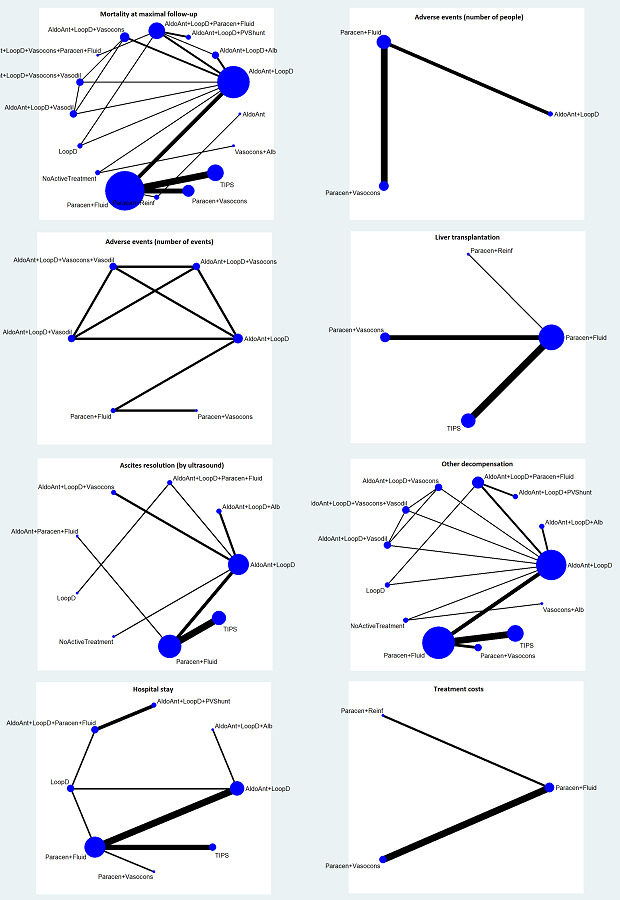

| Patient or population: people with liver cirrhosis and ascites Settings: secondary or tertiary care Intervention: various interventions Comparison: paracentesis plus fluid replacement Follow‐up period: 0.1 to 84 months Network geometry plots:Figure 1 | ||||||||

| Outcomes | Aldosterone antagonists plus loop diuretics | Paracentesis plus systemic vasoconstrictors | Aldosterone antagonists plus loop diuretics plus paracentesis plus fluid replacement | Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt | ||||

| Mortality at maximal follow‐up | ||||||||

| Paracentesis plus fluid replacement 368 per 1000 (36.8%) | HR 1.05 (0.70 to 1.69) Network estimate | 18 more per 1000 (109 fewer to 253 more) | HR 1.64 (0.46 to 6.32) Network estimate | 235 more per 1000 (200 fewer to 632 more) | HR 1.24 (0.62 to 2.59) Network estimate | 88 more per 1000 (141 fewer to 587 more) | HR 0.84 (0.60 to 1.18) Network estimate | 59 fewer per 1000 (148 fewer to 65 more) |

| Very low1,2,3 | Very low1,2,3 | Very low1,2,3 | Very low1,2,3 | |||||

| Based on 211 participants (4 RCTs) | Based on 165 participants (5 RCTs) | No direct RCT | Based on 452 participants (7 RCTs) | |||||

| Serious adverse events (number of events) | ||||||||

| Paracentesis plus fluid replacement 0 per 1000 (0 per 100 participants) | Rate ratio 1.30 (0.27 to 6.99) Direct estimate | Not estimable | ‐ | ‐ |

Not estimable (10 serious adverse events in 35 participants) |

|||

| Very low1,2,3 | Very low1,2,3 | |||||||

| Based on 41 participants (1 RCT) | Based on 70 participants (1 RCT) | |||||||

| Any adverse events (number of people) | ||||||||

| Paracentesis plus fluid replacement 100 per 1000 (10%) | OR 3.54 (0.43 to 27.41) Network estimate | 182 more per 1000 (54 fewer to 653 more) | OR 1.63 (0.30 to 11.66) Network estimate | 53 more per 1000 (68 fewer to 464 more) | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Very low1,2,3 | Very low1,2,3 | |||||||

| Based on 84 participants (2 RCTs) | Based on 145 participants (4 RCTs) | |||||||

| Any adverse events (number of events) | ||||||||

| Paracentesis plus fluid replacement 118 per 1000 (11.8 per 100 participants) | Rate ratio 4.12 (0.87 to 34.02) Network estimate | 367 more per 1000 (15 fewer to 3885 more) | Rate ratio 1.37 (0.36 to 5.82) Network estimate | 43 more per 1000 (76 fewer to 567 more) | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Very low1,2,3 | Very low1,2,3 | |||||||

| Based on 31 participants (1 RCT) | Based on 25 participants (1 RCT) | |||||||

| Liver transplantation at maximal follow‐up | ||||||||

| Paracentesis plus fluid replacement 121 per 1000 (12.1%) | ‐ | HR 1.08 (0.11 to 10.35) Network estimate | 10 more per 1000 (108 fewer to 879 more) | ‐ | HR 0.87 (0.52 to 1.44) Network estimate | 15 fewer per 1000 (58 fewer to 54 more) | ||

| Very low1,2,3 | Very low1,2,3 | |||||||

| Based on 145 participants (4 RCTs) | Based on 427 participants (6 RCT) | |||||||

| Resolution of ascites at maximal follow‐up (by ultrasound) | ||||||||

| Paracentesis plus fluid replacement 158 per 1000 (15.8%) | HR 1.10 (0.12 to 10.74) Network estimate | 16 more per 1000 (140 fewer to 842 more) | ‐ | HR 1.17 (0.01 to 98.79) Network estimate | 27 more per 1000 (156 fewer to 842 more) | HR 9.44 (1.93 to 62.68) Network estimate | 842 more per 1000 (147 more to 842 more) | |

| Very low1,2,3,4 | Very low1,2,3,4 | Very low1,2,4 | ||||||

| Based on 125 participants (3 RCTs) | No direct RCT | Based on 392 participants (6 RCTs) | ||||||

| Other features of decompensation at maximal follow‐up | ||||||||