Abstract

Background

Endometriosis is a common gynaecological condition affecting approximately 10% of women of reproductive age (Ozkan 2008). Common symptoms are dysmenorrhoea, pelvic pain, infertility or a pelvic mass. Diagnosis by laparoscopy or laparotomy enables identification of the location, extent and severity of the disease. Surgery may include removal (excision) or destruction (ablation) of endometriotic tissue, division of adhesions and removal of endometriotic cysts. Laparoscopic excision or ablation of endometriosis has been shown to be effective in the management of pain in mild to moderate endometriosis. Adjunctive medical treatment pre or post‐operatively may prolong the symptom‐free interval.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of medical therapies for hormonal suppression before or after surgery for endometriosis for improving painful symptoms, reducing disease recurrence and increasing pregnancy rates.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Trials Register (searched Sept 2010), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (Sept 2010), MEDLINE (January 1966 to September 2010), EMBASE (January 1985 to September 2010) and reference lists of articles.

Selection criteria

Trials were included if they were randomised controlled trials comparing medical therapies for hormonal suppression before or after or before and after, surgery for endometriosis.

Data collection and analysis

Data extraction and assessment of risk of bias were performed independently by two authors. Where possible, data were combined using relative risk (RR), standardised mean difference or mean difference and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

Sixteen trials were included. Two trials of pre‐surgical medical therapy showed no evidence of benefit compared to surgery alone. There was no evidence of benefit for post‐surgical hormonal suppression of endometriosis compared to surgery alone for the outcomes of pain, disease recurrence or pregnancy rates (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.18). There were no trials identified in the search that compared hormonal suppression of endometriosis before and after surgery with surgery alone. One trial found no evidence that pre‐surgical hormonal suppression was different from post‐surgical hormonal suppression for the outcome of pain. Another single trial comparing post‐surgical medical therapy with both pre and post‐surgery found no difference in the outcomes of American Fertility Society (AFS) scores and pregnancy rate.

Authors' conclusions

There is no evidence of benefit associated with post surgical medical therapy and insufficient evidence to determine whether there is a benefit from pre‐surgical medical therapy with regard to the outcomes evaluated.

Plain language summary

There is no evidence that hormonal suppression either before or after surgery for endometriosis is associated with a benefit

Endometriosis is caused by the lining of the uterus (endometrium) spreading outside the uterus. It can cause pelvic pain, painful periods and infertility. Common treatments are hormonal suppression with medical therapy to reduce the size of endometrial implants or laparoscopic surgery (where small incisions are made in the abdomen) to remove visible areas of endometriosis. There is no evidence that hormonal suppression either before or after surgery is associated with a benefit compared with surgery alone.

(Synopsis prepared by Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group)

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Endometriosis is a common gynaecological condition which affects women during their reproductive years. Endometriosis occurs when endometrial tissue, which usually grows in the uterus (normal), is found in other parts of the body, for example the ovaries, fallopian tubes and pelvis. A range of symptoms are evident and women most commonly present with dysmenorrhoea (painful periods), pelvic pain, infertility or a pelvic mass. Endometriosis also responds to hormonal changes associated with the menstrual cycle and cyclical growth of endometriotic implants or cysts is thought to be associated with pelvic pain and the development of adhesions (scar tissue). Estimates of the prevalence of endometriosis amongst women vary but a recent article (Ozkan 2008) reported a prevalence of 0.5% to 5% in fertile women and 25% to 40% in a subfertile population, with the peak incidence between 30 and 45 years of age (Guzick 1989). Endometriosis may be asymptomatic (no symptoms) or associated with chronic pelvic pain and subfertility (Cook 1991).

The 'gold standard' for the diagnosis of endometriosis is visualisation of endometriosis lesions or cysts during a surgical procedure, either laparoscopy or laparotomy. The extent of the disease can be graded according to a scale developed by the American Fertility Society (AFS 1985), although there is no direct correlation between the severity of the disease and the severity of the symptoms experienced (Vercellini 1996). Concern over the reproducibility of the scoring system resulted in the publication of a new scoring system in 1997 by the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM 1997).

Description of the intervention

Current treatments that are available for endometriosis include both surgery and medical therapy. Surgical therapy can be performed concurrently with diagnostic surgery and may involve the destruction of endometriotic tissue (ablation), division of adhesions (scar tissue) or removal of endometriotic cysts. In advanced endometriosis (AFS stage III or IV), laparoscopic surgery to remove (excise) visible endometrial implants, divide adhesions (scar tissue) or surgically interrupt neural pathways is the treatment of choice (Muzii 1996; Proctor 1999; Rana 1996). This is because large (> 3 cm) lesions respond poorly to medical therapy and hormonal suppression does not influence the extent of the adhesions which are often associated with large lesions (Shaw 1992).

Medical therapies for systemic hormonal suppression of endometriosis include danazol (a synthetic testosterone hormone derivative), gonadotrophin releasing hormone analogues (GnRHas), progestogens, gestrinone and the oral contraceptive pill. These therapies may be effective for relief of pain associated with endometriosis but they also decrease fertility. Both danazol and GnRHas are associated with side effects related to hyperandrogenism (increased hair growth and a deepening of the voice) and hypoestrogenism (such as hot flushes and vaginitis), respectively, and should only be used for periods of up to six months. Recurrence of endometriosis symptoms and disease is common after the cessation of medical therapy (Barbieri 1990).

How the intervention might work

Over recent years there has been interest in combining medical and surgical therapy in an attempt to reduce recurrence of endometriosis. The pre‐operative use of GnRHas may decrease the extent of endometriosis and the size of endometriomas (ovarian endometriosis) making complete removal of endometriosis easier during laparoscopic surgery and increasing subsequent pregnancy rates (Hemmings 1998; Donnez 1987). However possible disadvantages of pre‐operative medical therapy, especially with danazol or GnRHas, are the adverse effects associated with these medications (for example hot flushes or vaginal dryness), which may influence women's willingness to use the therapy and result only in a delay of surgery. Post‐operative medical therapy appears be an effective treatment of microscopic endometriosis which may not have been evident to the surgeon. It induces suppression of lesions that can not be surgically removed and reduces the risk of recurrence of endometriosis as a result of surgery (Kettel 1989; Thomas 1992).

Why it is important to do this review

Although the combination of surgery and medical therapy would appear to be beneficial, it is necessary to evaluate the benefits and consider the harms prior to this strategy being recommended. This review aims to evaluate the use of medical therapy before or after, or before and after, surgery for endometriosis.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of medical therapies for hormonal suppression before or after or before and after surgery for endometriosis for improving painful symptoms, reducing disease recurrence and increasing pregnancy rates.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials of the use of medical hormonal suppression therapies used:

pre‐surgery for endometriosis compared with surgery alone or placebo prior to surgery for the treatment of endometriosis;

post‐surgery for endometriosis compared with surgery alone or surgery and placebo;

pre and post‐surgery for endometriosis compared with surgery alone or surgery and placebo;

pre‐surgery for endometriosis compared with medical therapies used post‐surgery for endometriosis.

Types of participants

The study population included women of reproductive age who were undergoing surgery for endometriosis. The diagnosis of endometriosis could have been made provisionally by clinical examination and confirmed during the surgery, or could have been confirmed endometriosis where women were undergoing second or subsequent surgery. They would have further medical treatment either before or after surgery. Studies in the hospital care setting were considered.

Types of interventions

All systemic medical treatments for the hormonal suppression of endometriosis including GnRHas, danazol, progestogens, gestrinone or the oral contraceptive pill (or combinations of these) administered before surgery, after surgery or before and after surgery for endometriosis compared to medical treatment after surgery, before surgery, no medical treatment, or placebo were studied. The use of medical therapy was considered at any dosage and for a period of at least three months duration before or after surgery. Only agents used with the aim of hormonal suppression were included. Medical treatment with analgesics, anti‐inflammatory drugs or antibiotics were excluded. Alternative, dietary or complementary therapeutic strategies were also excluded. Modulation of the immune system via pentoxifylline treatment is considered in a separate systematic review (Lv 2009). All surgical procedures for the treatment of endometriosis that conserve the pelvic organs (such as ovarian cystectomy, drainage of endometriosis, excision or ablation of endometriosis) were included.

Types of outcome measures

The effectiveness of the use and timing of medical therapy as an adjunct to surgery for endometriosis was compared to surgery alone (no medical treatment or placebo) and was assessed by the following outcome measures where the data were available.

Primary outcomes

Painful symptoms of endometriosis as measured by a visual analogue scale (VAS) of pain, other validated scales or dichotomous outcomes

Recurrence of disease as evidenced by rAFS (revised American Fertility Society) or rASRM scores at second look laparoscopy

Pregnancy rate per woman (measured by either urinary human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) levels or foetal heart detected by ultrasound)

Secondary outcomes

Ease of surgery, duration of surgery, post‐operative complications

Levels of satisfaction of women participants

Adverse effects (proportion of women with one or more reported adverse effects associated with medical treatment)

Search methods for identification of studies

Reports that described or might have described randomised controlled trials of hormonal suppression in the treatment of endometriosis before or after surgery were obtained using the following search strategy.

Electronic searches

(1) We searched the Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Specialised Register of controlled trials (10 September 2003) for any trials of hormonal suppression in the treatment of endometriosis before or after surgery. The Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Specialised Register is based on regular searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycINFO, the handsearching of 20 relevant journals and conference proceedings, and searches of several key grey literature sources. A full description is given in the Group's module on The Cochrane Library.

(2) The following electronic databases were searched using Ovid software: MEDLINE (1966 to September 2010) (Appendix 1); EMBASE (1980 to September 2010) (Appendix 3); CINAHL (1982 to September 2010); Biological Abstracts (1980 to September 2010); PsycINFO (1872 to September 2010).

The search strategy was developed for MEDLINE Ovid and adapted for use on the other Ovid databases listed above.

(3) We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) on The Cochrane Library (20 September 2010) in all fields using the search terms listed in Appendix 2.

(4) We searched controlled trials.com for ongoing and recently completed trials.

Searching other resources

(5) We searched the reference lists and bibliographies of all relevant articles to identify additional trials for inclusion in this review.

(6) We sent letters to experts within the field, pharmaceutical companies producing the products being reviewed and authors of unpublished abstracts to identify unpublished trials of medical therapy before or after surgery for endometriosis.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The selection of trials for inclusion in the latest update of the review was performed by the two review authors (YC and SF) after employing the search strategy previously described. The titles and abstracts were screened and studies that were clearly ineligible were discarded but we aimed to be overly inclusive rather than risk losing relevant studies. Copies of the full articles were obtained. Both review authors then independently assessed whether the studies met the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Further information was sought from the authors where papers contained insufficient information to make a decision about eligibility.

Data extraction and management

Included trials were analysed for the following methodological details.

(1) Duration, timing and location of the study. (2) Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the trial. (3) Number of patients randomised, excluded or lost to follow up.

(4) Whether a power calculation was done.

(5) Source of funding for the trial.

This information is presented in the Characteristics of included studies table, which describes the included studies and provides a context for discussing the reliability of results.

Characteristics of the study participants

(1) Method of diagnosis of endometriosis (2) Severity of endometriosis (rAFS scores) (3) Severity of painful symptoms associated with endometriosis (pain scales) (4) Age and parity of study participants (5) General demographic characteristics of study participants

Interventions used

(1) Type of medical treatment used, dosage, duration of treatment, mode of administration (2) Type of control or placebo used (3) Timing of medical treatment (before or after surgery, or before and after surgery)

Outcomes

(1) Methods used to measure recurrence of disease (rAFS or rASRM scores at second look laparoscopy) (2) Methods used to measure pain relief achieved by treatment (e.g. VAS pain scores, other validated pain scores, dichotomous outcomes) (3) Pregnancy rate per woman during follow up (4) Methods used to measure adverse effects (including post‐operative complications) and types of adverse effects reported (5) Methods used to measure ease of surgery, duration of surgery (6) Length of follow up and timing of outcome measurement relative to timing of treatment (7) Methods used to measure levels of satisfaction of the women participants

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For the studies included in this review, assessment of risk of bias was conducted by two review authors using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2009). We assessed six domains for each included study: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessor, completeness of outcome data, risk of selective outcome reporting and risk of other potential sources of bias .

For this systematic review we assessed risk of bias according to the following criteria.

Adequate sequence generation: use of a random number table, use of a computerised system, central randomisation by statistical coordinating centre, randomisation by an independent service using minimisation technique, permuted block allocation or Zelan technique were considered adequate. If the paper merely stated 'randomised' or 'randomly allocated' with no further information this was assessed as being unclear.

Allocation concealment: centralised allocation including access by telephone call or fax, or pharmacy controlled randomisation, using sequentially numbered, sealed opaque envelopes were considered adequate. Where there was no mention of allocation concealment methods, this domain was assessed as unclear.

Blinding: for these treatments, even when blinding of patients and clinicians to treatment allocation was part of the trial protocol, the adverse effects of medical therapies make it difficult for blinding to be maintained. Therefore we have focused on whether the outcome assessment was blinded. Unless the trial was specifically described as double blind, or there was a statement about blinding in the methods section of the paper, it was assumed that blinding of patients, clinical staff and outcome assessors did not occur.

Outcome data: outcome data were considered complete if all patients randomised were included in the analysis of the outcome(s).

Selective outcome reporting: a trial was assessed as being at low risk of bias due to selective outcome reporting if the outcomes of interest described in the methods section were systematically reported in the results section. Where reported outcomes did not include those outcomes specified or expected in trials of treatments for endometriosis, this domain was assessed as unclear.

Other bias: imbalance in potentially important prognostic factors between the treatment groups at baseline, or the use of a co‐intervention in only one group (for example analgesics) were examples of potential sources of bias that were noted.

Additional information on trial methodology or original trial data was sought from the principal authors of trials which appeared to meet the eligibility criteria but were unclear in aspects of methodology or outcomes, or where the data were in a form unsuitable for meta‐analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

This review used both positive and negative outcome measures. This was taken into account when the meta‐analysis was interpreted. For example with regard to the outcome of pain, a positive treatment effect was associated with a reduction in pain scores indicated by a WMD less than zero. However with regard to pregnancy rates, which was a desirable outcome in the treatment of subfertility, a positive treatment effect was associated with an increase in pregnancy rate indicated by a relative risk (RR) greater than one. The data were entered so that in positive outcomes (for example pregnancy) points to the left of the 'line of no effect' favoured the control, and in the negative outcomes (for example pain) points to the left of the 'line of no effect' favoured treatment.

When neither continuous nor dichotomous data suitable for the calculation of mean difference, standardised mean difference or relative risk could be extracted from a trial, any available data were reported descriptively in additional data Table 11. It is expected that the data for outcomes of pain are skewed rather than normally distributed. Any skew ness was described in the results section.

1. Descriptive data for trials not included in the meta‐analysis.

| Study ID | Comparison | Outcome | n | Conclusion |

| Donnez 1994 | pre‐surgical GNRHa (goserelin) versus no medical therapy | mean endometrioma size | 40/40 | favouring goserelin mean difference ‐1.81cm (95% CI ‐2.05 to 1.57) |

| Shaw 2001 | pre‐surgical GNRHa (goserelin) versus no medical treatment | change in endometrioma size | 21/27 | favouring goserelin adj mean difference ‐1.25 cm (95% CI ‐2.42 to ‐0.08) |

| Shaw 2001 | complete excision of cyst | 21/27 | no difference 13/21 (72%) and 16/27 (73%) had cysts completely excised at surgery |

|

| Shaw 2001 | recurrence of residual cysts at 6 months | 21/27 | favours goserelin 2/21 (10%) and 4/27 (15%) had recurrence of residual cysts |

|

| Shaw 2001 | mean rAFS scores | 21/27 | no difference 41.7, 42.5 (no SD given) |

|

| Telimaa 1987 | MPA versus placebo | pain | 17/8 | pain scores after 12 months assessed with 4 point scales; MPA 1.8; Placebo 4.4 "significant difference" |

| Telimaa 1987 | danazol versus placebo | pain | 18/8 | pain scores after 12 months assessed with 4 point scales; danazol 2.5; placebo 4.4, "significant difference" |

| Telimaa 1987 | MPA versus placebo | patient satisfaction | 17/8 | patient satisfaction achieved in MPA 84% vs placebo 24% |

| Telimaa 1987 | danazol versus placebo | patient satisfaction | 18/8 | patient satisfaction achieved in danazol 84% vs placebo 24% |

| Tsai 2004 | post‐surgical leuprolide/danazol versus no treatment | cumulative pregnancy rate at 12 months after clomiphene stimulation in both groups | 15/30 | no difference 56.7% and 54.5% |

| Yang 2006 | post‐surgical gestrinone versus no medical treatment | disease recurrence at 6‐30 months | 19/13 | favours medical treatment 1/19 and 4/13 (p<0.05) |

| Audebert 1998 | pre‐surgical versus post‐surgical GnRHa (nafarelin) | AFS scores | 25/28 | total AFS score after 6 months was 0 and 6 in pre and post groups respectively (p= 0.007); no SD or SE given and not calculable. |

| Audebert 1998 | AFS scores | 25/28 | adhesion AFS score after 6 months was 0 and 2 in pre and post groups respectively (p= 0.007), no SD or SE given and not calculable. | |

| Audebert 1998 | AFS scores | 25/28 | implant AFS score after 6 months was 0 and 4 in pre and post groups respectively (p= 0.05), no SD or SE given and not calculable. | |

| Audebert 1998 | ease of surgery | 25/28 | surgery was easy in 56% of patients with GnRHa treatment pre‐surgery (Grp II) compared to 35.7% in the post‐surgery group (Grp I) |

Unit of analysis issues

The primary analysis was per woman randomised to treatment. Reported data that was based on a different unit of analysis (for example per endometrioma cyst) were not included in the meta‐analysis but were to be summarised in an additional table.

Dealing with missing data

Data were analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis, where possible, and attempts were made to contact authors to obtain missing data. Where studies reported data by type of medical therapy, these treatment groups were combined and compared to placebo or no treatment using mean difference and the standard deviation for continuous outcomes. Where the mean and standard deviation for the combined groups was not reported this was estimated using the formulae described in Table 7.7a in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009).

Assessment of heterogeneity

A fixed‐effect analysis was used unless the number of trials in a meta‐analysis was greater than three. It was planned that heterogeneity among the results of different studies would examined by inspecting the scatter in the data points and the overlap in their confidence intervals and, more formally, by checking the results of the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic.

Data synthesis

Statistical analysis was performed in accordance with the guidelines for statistical analysis developed by the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group.

Where possible, the outcomes were pooled statistically. For dichotomous data (for example proportion of patients with pain recurrence at 12 months), results for each study was expressed as a relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and combined for meta‐analysis with RevMan software using the Peto‐modified Mantel‐Haenszel method.

For continuous outcomes (for example multidimensional pain scores) means and standard deviations for each group were combined in the meta‐analysis and shown as a mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

A priori, it was planned to look at the possible contribution of differences in trial design, medical treatment used, timing of treatment, dosage, mode of administration and duration of treatment to any heterogeneity identified. Sensitivity analysis based on these criteria was planned to investigate the robustness of the data.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted where there were sufficient trials included, in order to determine whether the conclusions were robust that is whether conclusions would have differed if the inclusion of trials was restricted to those with low risk of bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The original search identified 11 trials that met the inclusion criteria (Audebert 1998; Batioglu 1997; Bianchi 1999; Busacca 2001; Donnez 1994; Hornstein 1997; Loverro 2001; Muzii 2000; Parazzini 1994; Telimaa 1987; Vercellini 1999). The updated search (in September 2010) identified a further six trials which met the inclusion criteria (Loverro 2008; Sesti 2007; Shaw 2001; Shawki 2002; Tsai 2004; Yang 2006). One trial (Shawki 2002) was published only as an abstract, with insufficient information available to include it in this review. Attempts to contact the author to obtain additional information have been unsuccessful. This study is listed under studies awaiting classification. Five new trials have been included in the updated review.

Of the 16 trials now included in this review, eight were conducted in Italy (Bianchi 1999; Busacca 2001; Loverro 2001; Loverro 2008; Muzii 2000; Parazzini 1994; Sesti 2007; Vercellini 1999 ) and one study was conducted in each of Belgium (Donnez 1994), China (Yang 2006), Finland (Telimaa 1987), France (Audebert 1998), Taiwan (Tsai 2004), Turkey (Batioglu 1997), UK/Republic of Ireland (Shaw 2001) and USA (Hornstein 1997). A total of 1410 women with endometriosis were randomly allocated to medical treatments which included gonadotrophin releasing hormone analogues (goserelin, leuprorelin, nafarelin, triptorelin), danazol, progestogen (gestrinone), and the combined oral contraceptive pill.

Included studies

Pre‐surgical medical therapy

Two trials compared pre‐surgical medical therapy for endometriosis to surgery alone (no medical therapy) (Donnez 1994; Shaw 2001). Donnez 1994 included 80 women with infertility who were < 35 years of age with laparoscopically confirmed ovarian endometriotic cysts which were drained and flushed out laparoscopically. The patients were then randomised to receive a subcutaneous goserelin implant four‐weekly for 12 weeks or no treatment. Twelve weeks after the first‐look laparoscopy, another laparoscopy was performed during which a biopsy was done, endometriosis and the cyst wall vaporised. AFS scoring was done by the same two observers.

Shaw 2001 randomised 48 women aged 18 to 50 years who had been referred for management of symptoms or infertility due to endometrioma. After the cysts were aspirated women received either goserelin four‐weekly for three months or no medical treatment. Following an ultrasound measurement of the residual cysts women underwent definitive excision and were then followed for a further six months. Outcomes included size of endometrioma pre‐surgery, proportion who had complete excision of cysts, AFS scores and recurrence of cysts at six months.

Post‐surgical medical therapy versus placebo or no treatment

Twelve studies assessed post‐surgical medical therapy for endometriosis. Five of these compared post‐operative medical therapy to placebo (Hornstein 1997; Loverro 2008; Parazzini 1994; Sesti 2007; Telimaa 1987) and in the remaining seven trials the control group received surgery alone with no medical therapy (Bianchi 1999; Busacca 2001; Loverro 2001; Muzii 2000; Tsai 2004; Vercellini 1999; Yang 2006).

Three different medical therapies were compared with placebo, in five trials (Hornstein 1997; Loverro 2008; Parazzini 1994; Sesti 2007; Telimaa 1987) and seven trials in this group compared post‐operative medical therapy with either GNRHa, danazol, progestogen or oral contraceptive pills to no post‐operative medical treatment (Bianchi 1999; Busacca 2001; Loverro 2001; Muzii 2000; Tsai 2004; Vercellini 1999; Yang 2006).

Hornstein 1997 and Parazzini 1994 both compared intranasal nafarelin (400 uG/day) with placebo over a period of six months and three months, respectively. Loverro 2008 randomised 60 women with a mean age of 28.6 years to three months of a post‐operative triptorelin depot or placebo and followed them for five years to evaluate persistence of pain, recurrence of endometrioma and pregnancy. In a large trial in Rome, Sesti 2007 randomly allocated 234 women with endometriosis to post‐operative medical treatment with GNRHa (either triptorelin or leuprorelin), continuous estroprogestin (OCP), dietary therapy (vitamins, minerals, lactic ferments and fish oil) or placebo and evaluated pain (dysmenorrhoea, non‐menstrual pelvic pain and dyspareunia) and quality of life. Data from the two hormonal suppression arms were combined and compared to placebo in the meta‐analysis. The other placebo controlled trial of post‐surgical medical therapy (Telimaa 1987) had two treatment arms, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) 100 mg/day taken orally for six months (n = 17) and danazol 600 mg/day (200 mg tds) for six months (n = 18), and a placebo arm (n = 16). Data have been reported separately for each group compared to placebo in Table 11. In the meta‐analysis of the subgroup of 22 patients in this trial desiring pregnancy, data from the medical therapy groups have been combined.

In Bianchi 1999, post‐surgical danazol, 600 mg/day for three months, was compared with surgery alone in 53 women. Busacca 2001, Loverro 2001 and Vercellini 1999 compared post‐surgical GnRHa (leuprolide, triptorelin and goserelin respectively), administered subcutaneously every four weeks for a period of 12 weeks, with surgery alone in groups of 89, 62 and 210 women with endometriosis respectively. Tsai 2004 randomly allocated 15 women to post‐operative treatment with either GNRHa (leuprolide, n = 8) or danazol (n = 7) and the remaining 30 to no post‐operative medical treatment prior to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation with clomiphene followed by intrauterine insemination or in vitro fertilisation. In China, Yang 2006 compared post‐operative treatment with traditional Chinese medicine, gestrinone or no treatment in 52 women and reported the pregnancy rate and recurrence of endometriosis with a nine and 30 months follow up. Muzii 2000 compared surgery plus six months of therapy with low‐dose cyclical oral contraceptives to surgery alone.

Pre‐surgical medical therapy compared with post‐surgical medical therapy

One study compared pre‐surgical medical therapy with post‐surgical medical therapy. Audebert 1998 compared medical therapy with intranasal nafarelin administered for six months before surgery with intranasal nafarelin administered for six months after surgery. Outcomes of pain, AFS scores and ease of surgery were assessed.

Post‐surgical medical therapy compared with pre and post‐surgical medical therapy

One study compared medical therapy pre and post‐surgery with medical therapy post‐surgery. Batioglu 1997 compared medical therapy with triptorelin commenced post‐surgery to medical therapy with triptorelin started in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle pre‐surgery and continued after surgery. The duration and dose of medical therapy was the same in both groups; the difference between the groups was the time that medical therapy started relative to surgery.

Risk of bias in included studies

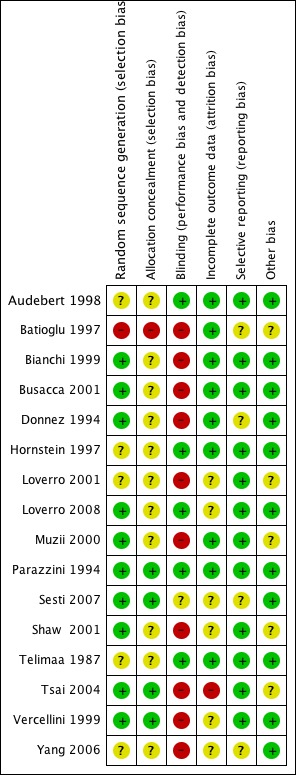

Only one of the 16 trials included in this review could be considered as at low risk of bias (Parazzini 1994) (see Figure 1). Details of the risk of bias assessments are summarised under the headings below.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Out of the 16 included studies, nine used computer generated randomisation (Bianchi 1999; Busacca 2001; Loverro 2008; Muzii 2000; Parazzini 1994; Sesti 2007; Shaw 2001; Tsai 2004; Vercellini 1999), one used randomisation tables (Donnez 1994) and one used odd and even numbers (Batioglu 1997). These studies were assessed as at low risk of bias for this domain. The remainder of studies did not state their method of randomisation (Audebert 1998; Hornstein 1997; Loverro 2001; Telimaa 1987; Yang 2006) and were therefore assessed as unclear for this domain.

Two studies reported adequate allocation concealment using telephone allocation (Parazzini 1994; Vercellini 1999). Sesti 2007 allocated patients by using serially numbered opaque, sealed envelopes whilst Tsai 2004 allocated patients according to list "unknown to physicians". These four studies were therefore assessed as being at low risk of bias. The remainder of the included studies did not describe their allocation methods and were therefore assessed as unclear.

Blinding

Four studies were double blinded (Audebert 1998; Hornstein 1997; Parazzini 1994; Telimaa 1987). In Loverro 2008 patients were blinded to treatment allocation and placebo injections were used. The trial by Sesti 2007 stated that "neither the patients nor the surgeons were aware of the regimen prescribed during the evaluation of improvement of endometriosis‐related pelvic pain and health related quality of life during the study period". However in this study patients received either placebo, GNRHa, oral contraceptive pills or dietary therapy so it is considered likely that maintaining blinding to treatment would have been difficult.

One study was open label (Vercellini 1999). Blinding was not described in the remaining studies. In all the studies included in this review the adverse effects of the medication may have alerted the investigators and the participants to the type of medical intervention.

Incomplete outcome data

Outcome data were incomplete in one study (Tsai 2004) with four women (27%) withdrawing from one group, which may have introduced a bias. A further six studies were assessed as being at unclear risk of bias for this domain (Loverro 2001; Loverro 2008; Sesti 2007; Shaw 2001; Vercellini 1999; Yang 2006). The remaining studies were assessed as being at low risk of bias for this domain, five had no post‐randomisation losses (Batioglu 1997; Bianchi 1999; Busacca 2001; Donnez 1994; Parazzini 1994) and three trials had few post‐randomisation losses (Audebert 1998: 3%; Muzii 2000: 4%; Telimaa 1987: 2%). One trial (Hornstein 1997) had a 15% post‐randomisation loss, approximately equal in the medical therapy and placebo groups.

Pregnancy is a desired outcome for some of the women included in these trials. Seven studies looked at pregnancy rates as an outcome measure. In Batioglu 1997, Parazzini 1994 and Telimaa 1987 pregnancy rates 12 months after treatment commenced were reported as an outcome for all participants in the trials; losses to follow up were small (0%, 9% and 2% respectively). Busacca 2001 and Loverro 2001 reported pregnancy rates after 18 months follow up in a subgroup of participants (30% and 40 % of participants respectively). Busacca 2001 reported no losses to follow up in the group desiring pregnancy and Loverro 2001 did not state whether there were any losses to follow up. In Vercellini 1999 pregnancy outcomes were reported in a subgroup of 152 women desiring fertility (56% of participants) after two years of follow up; losses to follow up in these groups were very small.

Other potential sources of bias

Five reports declared pharmaceutical support for their studies (Audebert 1998; Hornstein 1997; Parazzini 1994; Shaw 2001; Vercellini 1999) while Donnez 1994 had independent funding from Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique and Yang 2006 received funding from the Natural Science Foundation. The remainder did not describe any form of funding or support.

One trial (Tsai 2004), which was described as a randomised controlled trial, reported that patients were "randomly selected to receive" post‐operative medical treatment prior to ovarian stimulation over a period of 13 years (1988 to 2001). During this time period there have been significant advancements in endoscopic technology. It is unclear whether this resulted in any bias in the results of the study.

Two studies (Batioglu 1997; Shaw 2001) reported differences between the groups at baseline with regard to disease severity, which may have introduced a bias into the results from these studies. Loverro 2001 and Muzii 2000 did not report the characteristics of each group at baseline.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Post surgical medical therapies compared to No treatment or placebo for infertility associated with endometriosis.

| Post surgical medical therapies compared to No treatment or placebo for infertility associated with endometriosis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with infertility associated with endometriosis Intervention: Post surgical medical therapies Comparison: No treatment or placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No treatment or placebo | Post surgical medical therapies | |||||

| Pregnancy | 246 per 1000 | 207 per 1000 (145 to 290) | RR 0.84 (0.59 to 1.18) | 420 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Allocation concealment was not adequately explained in six of eight trials, there was no evidence of blinding in five trials and four trials did not explain incomplete outcome data 2 Only some of the trial participants were seeking treatment for fertility‐ numbers unclear

Summary of findings 2. Pre and post operative medical therapies versus placebo for endometriosis.

| Pre and post operative medical therapies versus placebo for endometriosis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with infertility associated with endometriosis Intervention: Post surgical medical therapies Comparison: Pre and post‐surgical medical therapy with GnRHa | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Pre and post‐surgical medical therapy with GnRHa | Post surgical medical therapies | |||||

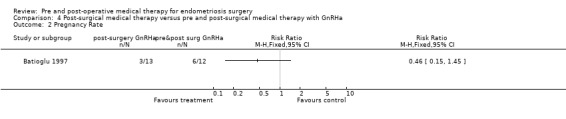

| Pregnancy Rate | 500 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 0 (0 to 0) | 25 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Description of randomisation , allocation concealment and blinding not adequate.

Summary of findings 3. Pre‐surgical medical therapy compared to no medical therapy for endometriosis surgery.

| Pre‐surgical medical therapy compared to no medical therapy for endometriosis surgery | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with endometriosis surgery Intervention: Pre‐surgical medical therapy Comparison: no medical therapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| no medical therapy | Pre‐surgical medical therapy | |||||

| Recurrence ‐ AFS Score ‐ Total AFS | The mean Recurrence ‐ AFS Score ‐ Total AFS in the intervention groups was 9.6 lower (11.42 to 7.78 lower) | 80 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 No blinding and trial lacked details on allocation concealment 2 Evidence based on a single trial

Summary of findings 4. Post‐surgical medical therapy compared to placebo or no treatment for endometriosis.

| Post‐surgical medical therapy compared to placebo or no treatment for endometriosis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with endometriosis Intervention: Post‐surgical medical therapy Comparison: placebo or no treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| placebo or no treatment | Post‐surgical medical therapy | |||||

| Pain (VAS) ‐ Dysmenorrhoea at 12 months | The mean Pain (VAS) ‐ Dysmenorrhoea at 12 months in the intervention groups was 0.58 standard deviations lower (0.87 to 0.28 lower) | 187 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | SMD ‐0.58 (‐0.87 to ‐0.28) | ||

| Pain (dichotomous) ‐ Pain recurrence </= 12 months | 273 per 1000 | 207 per 1000 (142 to 300) | RR 0.76 (0.52 to 1.1) | 332 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | |

| Pain (dichotomous) ‐ pain persistence/recurrence 5 years | 480 per 1000 | 446 per 1000 (254 to 797) | RR 0.93 (0.53 to 1.66) | 54 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4 | |

| Recurrence ‐ AFS Score ‐ Total AFS score (12 months) | The mean Recurrence ‐ AFS Score ‐ Total AFS score (12 months) in the intervention groups was 2.29 lower (4.69 lower to 0.11 higher) | 43 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,5 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 There are inadequate details on blinding and attrition 2 Evidence is based on a single study 3 Two of the trials did not provide adequate details for allocation concealment or attrition and there was no blinding 4 The trial lacked details on all methodological aspects and there was no blinding 5 The trial lacked details on allocation concealment and randomisation

Summary of findings 5. Pre‐surgical compared to Post‐surgical medical therapy for endometriosis surgery.

| Pre‐surgical compared to Post‐surgical medical therapy for endometriosis surgery | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with endometriosis surgery Intervention: Pre‐surgical Comparison: Post‐surgical medical therapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Post‐surgical medical therapy | Pre‐surgical | |||||

| Pain (Dichotomous) ‐ Dysmenorrhoea | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 53 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | There were no events reported in either the intervention or the control group |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The trial did not provide adequate details on allocation concealment or randomisation 2 Evidence based on a single trial

Summary of findings 6. Post‐surgical medical therapy compared to Pre and post‐surgical medical therapy with GnRHa for endometriosis surgery.

| Post‐surgical medical therapy compared to Pre and post‐surgical medical therapy with GnRHa for endometriosis surgery | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with endometriosis surgery Intervention: Post‐surgical medical therapy Comparison: Pre and post‐surgical medical therapy with GnRHa | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Pre and post‐surgical medical therapy with GnRHa | Post‐surgical medical therapy | |||||

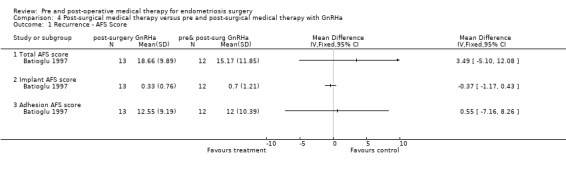

| Recurrence ‐ AFS Score ‐ Total AFS score | The mean Recurrence ‐ AFS Score ‐ Total AFS score in the intervention groups was 3.49 higher (5.1 lower to 12.08 higher) | 25 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 No adequate explanation of randomisation and allocation concealment 2 CI crossed line of no effect and substantive harm and benefit. 3 Evidence based on a single trial

Pre‐surgical medical therapy

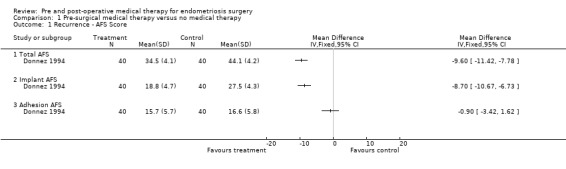

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pre‐surgical medical therapy versus no medical therapy, Outcome 1 Recurrence ‐ AFS Score.

Disease recurrence

Both trials used AFS scores as the outcome measure in comparing medical treatment pre‐surgery with surgery alone. Donnez 1994 showed a statistically significant reduction in endometrioma cyst size (Table 11), total AFS scores and implant AFS scores favouring the goserelin treated group but there was no statistically significant difference between the groups with regard to adhesion AFS scores (Analysis 1.1).

Shaw 2001 found a decrease in endometrioma size and a decreased recurrence rate in the goserelin group with no difference in mean total AFS scores post‐treatment (but no estimate of precision was stated so these data were not included in the meta‐analysis: the raw data only are presented in Table 11).

These two trials showed that pre‐operative GnRH agonist treatment decreased the size of endometrial cysts, although the clinical significance of this is unknown; however these trials were assessed as being at significant risk of bias and showed conflicting AFS results.

Based on these two trials there is insufficient evidence to conclude that pre‐surgical medical therapy was better than surgery alone.

Post‐surgical medical therapy versus placebo or no treatment

Pain

(Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2; Table 11)

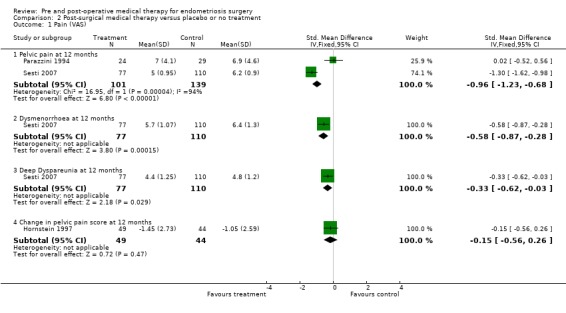

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Post‐surgical medical therapy versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 Pain (VAS).

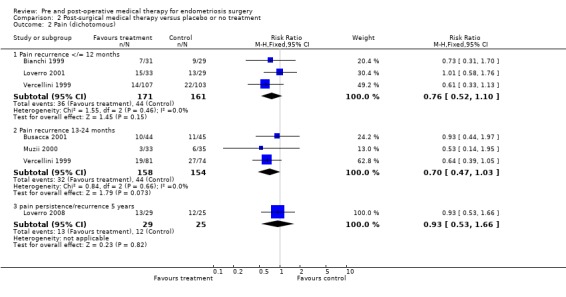

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Post‐surgical medical therapy versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2 Pain (dichotomous).

The outcome of pain was reported in 10 trials (Bianchi 1999; Busacca 2001; Hornstein 1997; Loverro 2001; Loverro 2008; Parazzini 1994; Muzii 2000; Sesti 2007; Telimaa 1987; Vercellini 1999).

Meta‐analysis was possible for the continuous outcome, mean VAS score of pelvic pain at 12 months, for two studies (Parazzini 1994; Sesti 2007) and the pooled estimate showed a statistically significant reduction in pelvic pain at 12 months (SMD ‐0.96, 95% CI ‐1.23 to ‐0.68) favouring medical therapy compared to placebo. However these studies show inconsistent effects and considerable statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 94%, P<0.0001). A third study (Telimaa 1987) reported pain after 12 months using a four‐point scale and presented mean scores without estimates of precision. The paper stated that there was a "significant difference between both danazol and placebo and MPA and placebo favouring medical therapy". It was not possible to include these data in the meta‐analysis but the estimates are recorded in Table 11.

Sesti 2007 also reported the outcomes of dysmenorrhoea and deep dyspareunia. When the groups receiving medical therapy were combined there was a statistically significant difference favouring medical therapy over placebo for both dysmenorrhoea and dyspareunia (Analysis 2.1.2; Analysis 2.1.3). In the trial by Hornstein 1997 the change in pain score from baseline to 12 months after surgery was presented and showed no statistically significant difference between medical therapy and placebo (Analysis 2.1.4).

Pain recurrence was measured during the first year after surgical treatment and reported in Bianchi 1999; Loverro 2001 and Vercellini 1999. The pooled estimate from these three trials showed no statistically significant difference between medical therapy and surgery alone (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.10) (Analysis 2.2.1).

Pain recurrence during the second year after surgery was reported in three trials (Busacca 2001; Muzii 2000; Vercellini 2003) and the pooled estimate also showed no statistically significant difference between medical therapy after surgery and surgery alone (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.03) (Analysis 2.2.2).

Five years after treatment, a single study (Loverro 2008) found no statistically significant difference in pain persistence or recurrence between medical therapy and placebo (Analysis 2.2.3).

Disease recurrence

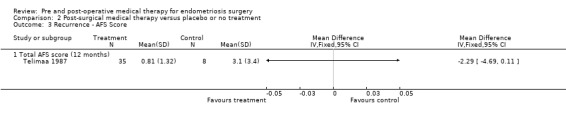

The only study in this group to report AFS scores for disease recurrence was Telimaa 1987. After 12 months, a second‐look laparoscopy showed a statistically significant reduction in AFS scores from baseline in all three groups: MPA, danazol and placebo. When each active treatment group was compared to placebo, there was a statistically significant mean difference favouring MPA, but the difference between danazol and placebo was not statistically significant (Table 11) and the combined mean AFS score for both medical therapies was not statistically significantly different from placebo (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Post‐surgical medical therapy versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 3 Recurrence ‐ AFS Score.

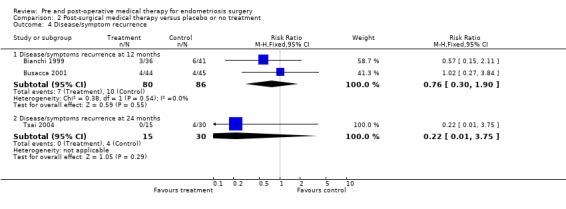

Disease or symptom recurrence, evaluated by gynaecological examination or ultrasonography, was measured at two time points: one year and two years after surgery . There was no statistically significant difference in disease recurrence at one year (Bianchi 1999; Busacca 2001) between surgery plus medical therapy and surgery alone (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.90) (Analysis 2.4.1) and no difference at two years in the one study (Tsai 2004) that reported this outcome (Analysis 2.4.2).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Post‐surgical medical therapy versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 4 Disease/symptom recurrence.

Pregnancy

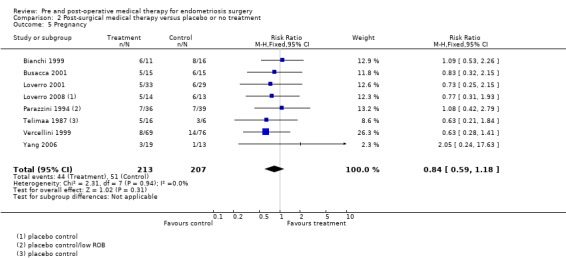

Pregnancy was a desired outcome in some of the patients in eight studies (Bianchi 1999; Busacca 2001; Loverro 2001; Loverro 2008; Parazzini 1994; Telimaa 1987; Vercellini 1999; Yang 2006). There was no difference between surgery plus medical therapy and either surgery plus placebo or no treatment with regard to pregnancy rate following treatment (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.18) (Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Post‐surgical medical therapy versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 5 Pregnancy.

Patient satisfaction

Only one study reported the outcome of patients satisfaction. Telimaa 1987 reported an increase in patient satisfaction in both active treatment groups, which was statistically significantly greater compared to the placebo group but there was no difference between the danazol and MPA groups for either of these outcomes (Table 11).

Pre‐surgical medical therapy compared with post‐surgical medical therapy

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Pre‐surgical versus post‐surgical medical therapy, Outcome 1 Pain (Dichotomous).

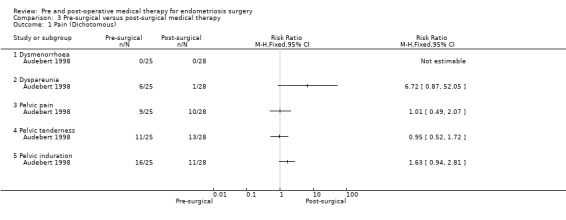

In the single study in this comparison (Audebert 1998) there was no statistically significant difference between the groups for the outcome of pain (Analysis 3.1).

The trial reported that the pre‐operative nafarelin group had statistically significantly lower global AFS scores, adhesion scores and 'endometriosis scores' compared to the post‐operative nafarelin group, but data were presented in a form that was not suitable for inclusion in a forest plot so these data are recorded in Table 11.

Surgery was described as 'easy' in a higher proportion of the pre‐operative nafarelin group compared to the post‐operative nafarelin group, but no indication of any statistical significance was given.

Post‐surgical medical therapy compared with pre and post‐surgical medical therapy

In this small study (Batioglu 1997) (n = 25) no statistically significant differences were found between the groups with respect to the outcomes of recurrence (total AFS scores, implant AFS scores, adhesion AFS scores) (Analysis 4.1) and pregnancy rate (Analysis 4.2).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Post‐surgical medical therapy versus pre and post‐surgical medical therapy with GnRHa, Outcome 1 Recurrence ‐ AFS Score.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Post‐surgical medical therapy versus pre and post‐surgical medical therapy with GnRHa, Outcome 2 Pregnancy Rate.

Adverse effects

The adverse effects data were summarised in a 'Table of adverse drug effects' in the additional tables section (Table 12). Adverse effects were described in some trials but data were not presented in a way that allowed any quantitative analysis.

2. Table of adverse drug effects.

| Trial ID | Adverse Drug Effects | Withdrawals‐ADE |

| Audebert 1998 | Side effects were reported with equal frequency in both groups and were consistent with those published by other investigators | 2 withdrawals after randomisation from hot flushes and headaches |

| Batioglu 1997 | Not described | None |

| Bianchi 1999 | Hyperandrogenism 16.7%, weight gain ≥3kg 8.3% | None |

| Busacca 2001 | Most experienced menopausal symptoms, all became amenorrhoeic | 1 withdrawal from unacceptable side effects |

| Donnez 1994 | Not described | None |

| Hornstein 1997 | Not described | Not due to ADE |

| Loverro 2001 | Not described | None |

| Loverro 2008 | Not described | None |

| Muzii 2000 | Not described | Not due to ADE |

| Parazzini 1994 | Amenorrhoea in all actively treated, none in placebo group | None |

| Sesti 2007 | Menopausal symptoms, spotting, bloating, weight gain and headache reported but "well tolerated" | 4 withdrew from hormonal suppression group due to AE |

| Shaw 2001 | Hot flushes (62%), headaches (29%), dysmenorrhoea (14%) in goserelin group and 33% had dysmenorrhoea in no treatment group | 4 withdrew from goserelin gp due to serious AE (1 treated to treatment) |

| Telimaa 1987‐Danazol and Telimaa 1987‐MPA |

Weight increase MPA 1.9±1.3kg, danazol 3.4±2.3kg, placebo 0.4±2.6kg; breakthrough bleeding at 6/12: MPA 65%, danazol 56%, placebo 6%; acne at 6/12: danazol 56%, placebo 6% | Not due to ADE |

| Tsai 2004 | Not described | Reasons for withdrawals not given |

| Vercellini 1999 | Not described | None |

| Yang 2006 | Not described | None |

Sensitivity analysis

Planned sensitivity analysis was not undertaken because only one of the 16 trials was assessed as being at low risk of bias.

Discussion

Summary of main results

(1) There is insufficient evidence to support the view that medical therapy for hormonal suppression of endometriosis prior to surgery is more effective than surgery alone. Two studies compared pre‐surgical medical therapy with surgery alone. AFS scores were significantly improved in the medical treatment group in one study and not in the other. Meta‐analysis of the data from these studies was not possible. Medical therapy may or may not be associated with better outcomes for the patients.

(2) Post‐surgical hormonal suppression of endometriosis compared to surgery alone (either no medical therapy or placebo) showed some reduction in pain after 12 months but results were inconsistent and pain recurrence in both groups indicated that there was no evidence of a benefit for pain beyond 12 months. There was no evidence of benefit for the outcomes of disease recurrence (AFS scores) or pregnancy (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.18).

(3) There were no trials identified from the search that compared hormonal suppression of endometriosis before and after surgery with surgery alone.

(4) There was no significant difference between pre‐surgery hormonal suppression and post‐surgery hormonal suppression for the outcome of pain in the one trial identified. This trial reported a statistically significant reduction in recurrence at six months as measured by AFS scores but ease of surgery was reported only as a descriptive summary so any difference between the groups can not be quantified from the information given in the report of this trial.

(5) There was insufficient evidence to support the view that medical therapy for hormonal suppression of endometriosis pre and post‐surgery was more effective than medical therapy post‐surgery only.

In summary, the use of medical treatment after surgery was not associated with a long‐term statistically significant difference in pain from endometriosis. When used prior to surgery, medical therapy was shown to decrease cyst size but the effect on AFS scores was conflicting. There is no evidence that medical therapy pre or post‐surgery improves pregnancy rates. No conclusions can be drawn with respect to the outcomes of facilitating surgery, duration of surgery, post‐operative complications or levels of satisfaction of women participants from the trials included in this review. Adverse effects were described but not quantified, so no direct comparisons between the included trials were possible.

Quality of the evidence

A strength of this review is that all of the included studies involved women with laparoscopically diagnosed endometriosis and laparoscopic assessment of the extent of the endometriosis. Weaknesses of this review are that the included studies were small and many were at risk of bias. There was a spread of different times at which a range of different outcomes were measured, which does not allow for studies to be combined in a meta‐analysis. Only one study used a quality of life measure as an outcome (Sesti 2007) although this may well be the outcome of most interest to women with endometriosis.

There were some methodological issues in the trials included in this review. Of the 16 reports of randomised controlled trials, 11 described the randomisation process used but only four reported adequate allocation concealment. Four of the 16 studies were double blinded and in two studies the outcome assessors were blinded to the intervention status. The side effects associated with medical therapies for endometriosis are such that maintaining blinding of participants and investigators is likely to have been difficult in these trials.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is no evidence from the studies identified to conclude that hormonal suppression in association with surgery for endometriosis is associated with a significant benefit with regard to any of the outcomes identified. From two studies of pre‐surgical medical therapy there is no evidence that pre‐surgical medical therapy is better than surgery alone. There was no evidence that post‐surgical medical therapy was associated with a benefit compared to surgery alone.

Implications for research.

Research done to assess the effects of medical treatment pre or post‐surgery for endometriosis is associated with many difficulties. Not many women will consent to undergo second‐look laparoscopy to assess the results of previous treatment modalities. Hence, recruiting large numbers of participants for randomised trials is difficult. Maintaining blinding is also difficult due to the adverse effects associated with hormonal suppression, which would be obvious to both the patient and investigator. Blinded outcome assessment is possible and desirable. Women with subfertility due to endometriosis may also not accept treatment that may improve pain and other symptoms but reduces or delays their chance of conceiving.

Despite these difficulties, it would be valuable to have well designed, adequately powered and well conducted trials to determine if there is a significant benefit in adjunctive medical therapy before or after surgery for endometriosis. Consistency in the methods of assessing outcomes, with respect to pain and the extent of endometriosis from AFS scores, would also facilitate meta‐analysis of data across trials. Data to quantify the number and degree of adverse events experienced as a result of medical therapy would enable better assessment of the comparative benefits and harms of medical treatment.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 May 2011 | Amended | Summary of findings tables added |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2002 Review first published: Issue 3, 2004

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 20 September 2010 | New search has been performed | Substantive update September 2010 ‐ 5 new trials included. Risk of bias assessment on all included studies. Minor changes to the objectives ‐ hypotheses deleted |

| 7 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 26 May 2004 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) in Auckland, New Zealand, for their help, advice and support during the preparation of the original review. For the current update of the review we would like to thank Marian Showell (Trials Search Coordinator) who updated the searches.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

1 Endometriosis/ (14076) 2 endometrio$.ti,ab,sh. (19246) 3 adenomyosis.tw. (1325) 4 or/1‐3 (19555) 5 exp Contraceptives, Oral/ (38769) 6 (oral contraceptive$ or contraceptive$ pill$).tw. (20171) 7 OCP.tw. (1048) 8 exp Gonadotropin‐Releasing Hormone/ (26314) 9 (GnRH or lhrh or gn‐rh or lfrh or lh‐rh or lhfshrh).tw. (24157) 10 Gonadotropin‐Releasing Hormone.ti,ab,sh. (26055) 11 (gonadorelin or luliberin or luteinizing hormone‐releasing hormone or cystorelin).tw. (5201) 12 (dirigestran or factrel or gonadoliberin).tw. (135) 13 danazol/ or danazol.tw. (2626) 14 progestins/ or gestrinone/ or progesterone/ (55370) 15 (progestogen$ or gestrinone).tw. (4456) 16 or/5‐15 (129407) 17 specialties, surgical/ or gynecology/ or surgery/ (42306) 18 surg$.tw. (1064203) 19 Laparoscopy/ (45637) 20 Laparoscop$.ti,ab,sh. (68764) 21 celioscop$.tw. (534) 22 peritoneoscop$.tw. (617) 23 Surgical Procedures, Minimally Invasive/ (12402) 24 exp Surgical Procedures, Operative/ (1965124) 25 or/17‐24 (2517350) 26 4 and 16 and 25 (1367) 27 randomized controlled trial.pt. (299824) 28 controlled clinical trial.pt. (82501) 29 randomized.ab. (213949) 30 placebo.tw. (129005) 31 clinical trials as topic.sh. (151072) 32 randomly.ab. (158040) 33 trial.ti. (91956) 34 (crossover or cross‐over or cross over).tw. (49316) 35 or/27‐34 (728695) 36 (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. (3453357) 37 35 not 36 (674119) 38 26 and 37 (219) 39 2010$.ed. (775885) 40 38 and 39 (8)

Appendix 2. CENTRAL search strategy

1 Endometriosis/ (392) 2 endometrio$.ti,ab,sh. (746) 3 adenomyosis.tw. (23) 4 or/1‐3 (761) 5 exp Contraceptives, Oral/ (2713) 6 (oral contraceptive$ or contraceptive$ pill$).tw. (1478) 7 OCP.tw. (43) 8 exp Gonadotropin‐Releasing Hormone/ (1664) 9 (GnRH or lhrh or gn‐rh or lfrh or lh‐rh or lhfshrh).tw. (1803) 10 Gonadotropin‐Releasing Hormone.ti,ab,sh. (1247) 11 (gonadorelin or luliberin or luteinizing hormone‐releasing hormone or cystorelin).tw. (239) 12 (dirigestran or factrel or gonadoliberin).tw. (5) 13 danazol/ or danazol.tw. (294) 14 progestins/ or gestrinone/ or progesterone/ (1257) 15 (progestogen$ or gestrinone).tw. (617) 16 or/5‐15 (6967) 17 specialties, surgical/ or gynecology/ or surgery/ (257) 18 surg$.tw. (56109) 19 Laparoscopy/ (2020) 20 Laparoscop$.ti,ab,sh. (4319) 21 celioscop$.tw. (9) 22 peritoneoscop$.tw. (13) 23 Surgical Procedures, Minimally Invasive/ (392) 24 exp Surgical Procedures, Operative/ (65773) 25 or/17‐24 (94838) 26 4 and 16 and 25 (170) 27 limit 26 to yr="2010 ‐Current" (3)

Appendix 3. EMBASE

1 Endometriosis/ (17794) 2 endometrio$.ti,ab,sh. (23228) 3 adenomyosis.tw. (1571) 4 or/1‐3 (24065) 5 exp Contraceptives, Oral/ (44979) 6 (oral contraceptive$ or contraceptive$ pill$).tw. (18807) 7 OCP.tw. (1147) 8 exp Gonadotropin‐Releasing Hormone/ (24685) 9 (GnRH or lhrh or gn‐rh or lfrh or lh‐rh or lhfshrh).tw. (25582) 10 Gonadotropin‐Releasing Hormone.ti,ab,sh. (9813) 11 (gonadorelin or luliberin or luteinizing hormone‐releasing hormone or cystorelin).tw. (4930) 12 (dirigestran or factrel or gonadoliberin).tw. (270) 13 danazol/ or danazol.tw. (6487) 14 progestins/ or gestrinone/ or progesterone/ (75274) 15 (progestogen$ or gestrinone).tw. (4557) 16 or/5‐15 (153928) 17 laparoscopy/ (37548) 18 laparoscop$.mp. (88603) 19 celioscop$.mp. (964) 20 peritoneoscop$.mp. (655) 21 surgical procedures, Minimally invasive/ (16214) 22 exp surgical procedures, operative/ (2443651) 23 gynaecologic surgery/ or endoscopic surgery/ (30299) 24 or/17‐23 (2448911) 25 4 and 16 and 24 (1983) 26 Clinical Trial/ (806389) 27 Randomized Controlled Trial/ (280762) 28 exp randomization/ (52428) 29 Single Blind Procedure/ (13288) 30 Double Blind Procedure/ (99074) 31 Crossover Procedure/ (29228) 32 Placebo/ (167897) 33 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (56110) 34 Rct.tw. (5927) 35 random allocation.tw. (988) 36 randomly allocated.tw. (14617) 37 allocated randomly.tw. (1666) 38 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (676) 39 Single blind$.tw. (10363) 40 Double blind$.tw. (113147) 41 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (224) 42 placebo$.tw. (150524) 43 prospective study/ (155097) 44 or/26‐43 (1083621) 45 case study/ (10221) 46 case report.tw. (190983) 47 abstract report/ or letter/ (753390) 48 or/45‐47 (951065) 49 44 not 48 (1052070) 50 25 and 49 (494) 51 2010$.em. (849128) 52 50 and 51 (44)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Pre‐surgical medical therapy versus no medical therapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Recurrence ‐ AFS Score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Total AFS | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Implant AFS | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Adhesion AFS | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 2. Post‐surgical medical therapy versus placebo or no treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain (VAS) | 3 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Pelvic pain at 12 months | 2 | 240 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.96 [‐1.23, ‐0.68] |

| 1.2 Dysmenorrhoea at 12 months | 1 | 187 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.58 [‐0.87, ‐0.28] |

| 1.3 Deep Dyspareunia at 12 months | 1 | 187 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.33 [‐0.62, ‐0.03] |

| 1.4 Change in pelvic pain score at 12 months | 1 | 93 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.15 [‐0.56, 0.26] |

| 2 Pain (dichotomous) | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Pain recurrence </= 12 months | 3 | 332 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.52, 1.10] |

| 2.2 Pain recurrence 13‐24 months | 3 | 312 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.47, 1.03] |

| 2.3 pain persistence/recurrence 5 years | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.53, 1.66] |

| 3 Recurrence ‐ AFS Score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Total AFS score (12 months) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Disease/symptom recurrence | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Disease/symptoms recurrence at 12 months | 2 | 166 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.30, 1.90] |

| 4.2 Disease/symptoms recurrence at 24 months | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.22 [0.01, 3.75] |

| 5 Pregnancy | 8 | 420 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.59, 1.18] |

Comparison 3. Pre‐surgical versus post‐surgical medical therapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain (Dichotomous) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Dysmenorrhoea | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Dyspareunia | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Pelvic pain | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Pelvic tenderness | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.5 Pelvic induration | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 4. Post‐surgical medical therapy versus pre and post‐surgical medical therapy with GnRHa.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Recurrence ‐ AFS Score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Total AFS score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Implant AFS score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Adhesion AFS score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Pregnancy Rate | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Audebert 1998.

| Methods | Location: France

No. of centres: multi centre Recruitment period: December 1990 to March 1993 |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: < 40 years, stage III‐IV endometriosis, pelvic pain, dysmenorrhoea or dyspareunia Exclusion criteria: > 40 years, hormonal treatment for endometriosis within 3/12 (including OCP, progestins), significant medical illness e.g. liver, heart, renal disease, abnormal PAP smear, pregnancy, surgery for endometriosis within 6/12 No. randomised: 55 No. analysed: 53 | |

| Interventions | Gr A (n=28) Pre‐surgery medical treatment with nafarelin nasal 400 uG daily x 6/12 Gr B (n=25) Post‐surgery medical treatment with nafarelin nasal 400 uG daily x 6/12 | |

| Outcomes | Pain: dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, pelvic tenderness, pelvic induration AFS scores: global, adhesions, endometriosis Ease of surgery | |

| Notes | Power calculation: NS Funding: Syntex Pharmaceuticals International for supply of Nafarelin, grant for trial | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomised" no details of method of sequence generation provided |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | not mentioned |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | double blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | all randomised patients included in analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | important outcomes ‐ AFS scores, recurrence, surgical difficulty reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | groups appear comparable at baseline |

Batioglu 1997.

| Methods | Location: Ankara Turkey

No. of Centres: 1 Recruitment period: NS |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: ovarian endometriomas >3cm unilateral/bilateral No. randomised: 25 No. analysed: 25 |

|

| Interventions | Post‐surgery medical treatment with triptorelin 3.75 mg IM x 4 weekly for 6 months (n = 13) versus Pre‐surgery and post‐surgery treatment with triptorelin 3.75 mg IM x 4 weekly for 6 months (n = 12) | |

| Outcomes | AFS scores at 6 months Pregnancy rate at 1 year follow up | |

| Notes | Power calculation: NS Funding: NS | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | "randomly allocated into one of the treatment groups, odd numbers in the first group and even numbers in the second |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | no allocation concealment |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | not mentioned, no placebo |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | pregnancy rate reported for all randomised patients |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | mean AFS scores reported per endometrioma not per patient, pregnancy rate |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | there were differences between the groups at baseline with regard to mean adhesion scores |

Bianchi 1999.

| Methods | No. of centres: 1

Location: University of Milan, Italy Recruitment period: July 1994 to October 1996 |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: < 40 yrs Exclusion criteria: medical or surgical treatment for endometriosis, concurrent disease that might affect fertility or cause pelvic pain, women without pain symptoms, women not seeking pregnancy, liver or endocrine disease No. randomised: 77 No. analysed: 77 | |

| Interventions | Post‐surgical medical therapy 1. Danazol oral 600 mg daily x 3/12 (n = 36) 2. No treatment (n = 41) | |

| Outcomes | Pain recurrence AFS scores Pregnancy rates Adverse events of medication | |

| Notes | Power calculation: NS Funding: NS | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomization was done according to a computer generated list" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | not mentioned |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | not mentioned, no placebo |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | all randomised patients included in analysis |