Abstract

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a global leading cause of morbidity and mortality, characterised by acute deterioration in symptoms. During these exacerbations, people are prone to developing alveolar hypoventilation, which may be partly caused by the administration of high inspired oxygen concentrations.

Objectives

To determine the effect of different inspired oxygen concentrations ("high flow" compared to "controlled") in the pre‐hospital setting (prior to casualty/emergency department) on outcomes for people with acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD).

Search methods

The Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register, reference lists of articles and online clinical trial databases were searched. Authors of identified randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were also contacted for details of other relevant published and unpublished studies. The most recent search was conducted on 16 September 2019.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs comparing oxygen therapy at different concentrations or oxygen therapy versus placebo in the pre‐hospital setting for treatment of AECOPD.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. The primary outcome was all‐cause and respiratory‐related mortality.

Main results

The search identified a total of 824 citations; one study was identified for inclusion and two studies are awaiting classification. The 214 participants involved in the included study were adults with AECOPD, receiving treatment by paramedics en route to hospital. The mean age of participants was 68 years.

A reduction in pre/in‐hospital mortality was observed in favour of the titrated oxygen group (two deaths in the titrated oxygen group compared to 11 deaths in the high‐flow control arm; risk ratio (RR) 0.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.05 to 0.97; 214 participants). This translates to an absolute effect of 94 per 1000 (high‐flow oxygen) compared to 21 per 1000 (titrated oxygen), and a number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) of 14 (95% CI 12 to 355) with titrated oxygen therapy. Other than mortality, no other adverse events were reported in the included study.

Wide confidence intervals were observed between groups for arterial blood gas (though this may be confounded by protocol infidelity in the included study for this outcome measure), treatment failure requiring invasive or non‐invasive ventilation or hospital utilisation. No data were reported for quality of life, lung function or dyspnoea. Risk of bias within the included study was largely unclear, though there was high risk of bias in domains relating to performance and attrition bias. We judged the evidence to be of low certainty, according to GRADE criteria.

Authors' conclusions

The one included study found a reduction in pre/in‐hospital mortality for the titrated oxygen arm compared to the high‐flow control arm. However, the paucity of evidence somewhat limits the reliability of these findings and generalisability to other settings. There is a need for robust, well‐designed RCTs to further investigate the effect of oxygen therapies in the pre‐hospital setting for people with AECOPD.

Plain language summary

Oxygen therapy in the pre‐hospital setting for sudden worsening of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic condition characterised by progressively worsening reduction of airflow through the lungs. People with COPD are prone to sudden episodes where their symptoms become worse (e.g. persistent increase in shortness of breath and changes in mucous volume and consistency) and oxygen levels may fall. Initial treatment during these episodes, when patients are being transported to hospital, usually includes oxygen. However, delivering too much oxygen to these patients may cause a rise in the level of carbon dioxide that can eventually lead to a reduced breathing rate and possibly stop their ability to breathe at all.

Review question

This review aimed to investigate if oxygen therapy delivered at different concentrations based on patient needs would be less harmful, more harmful, or make no difference when compared to a control group using high‐flow oxygen.

Study characteristics

To investigate this question we looked for randomised controlled trials (RCTs), these are studies in which people involved have an equal chance of receiving the treatment or comparator. We were interested in trials that compared different flow rates (concentrations) of oxygen delivered in an ambulance to people being transferred to hospital because of sudden worsening of COPD symptoms.

Key results

Only one study was found that addressed the review question. The study randomised participants to either have titrated oxygen (oxygen therapy delivered at different concentrations tailored to patient needs in order to keep the levels of oxygen in the blood between 88% and 92%) or high‐flow oxygen (oxygen therapy delivered at a consistently high concentration).

There were fewer deaths (two people) in the group that received titrated oxygen, compared to the control group using high‐flow oxygen delivered at eight to ten litres per minute using a mask (11 people).

Certainty of evidence

Due to inclusion of only one study, and the small number of deaths that occurred, our confidence in the size of the difference between the two treatments is limited. We judged the evidence to be of low certainty.

Bottom line

The one included study found that delivering individually tailored oxygen concentrations to people when they are being transported to hospital with sudden worsening of COPD, reduces the risk of death compared to using a consistently high concentration of oxygen. However, the body of evidence is too small to confidently claim that titrated oxygen is less harmful and more effective than high‐flow oxygen in this group of people across the board.

This plain language summary is current to September 2019.

Summary of findings

Background

This is an update of a Cochrane Review previously published in 2006 (Austin 2006).

Description of the condition

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide (Lozano 2013) and contributes to global morbidity and mortality, particularly in those over 45 years of age. This burden is expected to continue to rise for the foreseeable future. By 2020, COPD is expected to be the third leading cause of death in the world (GOLD 2018; Lozano 2013; Mendis 2014; Vos 2012). COPD is not one single condition, but instead is an umbrella term used to describe a combination of chronic lung diseases that cause inflammation, including chronic bronchitis and emphysema (WHO 2018). Tobacco smoking is known to be the most common cause of COPD; lifelong smokers having a 50% probability of developing COPD (Laniado‐Laborin 2009). Other modifiable risk factors include: exposure to environmental smoke (such as fumes from carbon‐based cooking, including early childhood exposure, and heating fuels used for cooking like charcoal and gas), occupational hazards (such as exposure to chemicals and pollutants), poor nutrition, intrauterine exposures and pneumonia or other respiratory infections during childhood (AIHW 2016). Non‐modifiable risk factors include age (COPD is more common as people age), low socioeconomic status index and genetic predisposition (primarily alpha‐1 antitrypsin deficiency) (AIHW 2016; Grigsby 2016).

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is characterised by irreversible and progressive destruction of lung parenchyma and structural change to small airways owing to a chronic inflammatory process (GOLD 2018). This results in breathlessness (initially with exertion), chronic cough and sputum production that gradually worsen as the condition progresses over time (WHO 2018). An acute, abnormal deterioration of respiratory symptoms is termed an acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) (GOLD 2018). These are serious episodes of increasing breathlessness, cough and sputum production that can last from several days to weeks; they can require hospitalisation and result in death (WHO 2018). COPD patients may develop alveolar hypoventilation, which results in an elevation of the partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO₂), known as hypercarbia, and a reduction in partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO₂), known as hypoxaemia (Abdo 2012). The combination of a PaO₂ below 60 and PaCO₂ above 45 is referred to as hypoventilatory (hypercapnic) respiratory failure. It is associated with poor outcomes in AECOPD (Groenewegen 2003). As COPD is a heterogenous condition, different pathological processes predominate in different areas of the lung, resulting in wasted perfusion and differentially oxygenated blood on return to systemic circulation (Brill 2014; Cooper 2008).

Description of the intervention

In healthy non‐smoking adults, oxygen saturations of 94% to 98% are considered normal, with levels diminishing as people age (Brill 2014; Kane 2013). For example, a 70 year old may have an oxygen saturation of less than 94%, which may still be considered normal, particularly in the presence of comorbidities such as heart failure (Kane 2013). People having an AECOPD typically present to hospital with lower levels of oxygen saturation in the blood due to the destruction of lung parenchyma and structural changes resulting in poor gas exchange (GOLD 2018). Thus, administration of oxygen at concentrations greater than that found in the surrounding air will help to increase oxygen saturation or carbon dioxide excretion, or both (Brill 2014). Oxygen is one of the most commonly administered drugs in the pre‐hospital and emergency setting; 34% of people being transported by ambulance are estimated to receive it (Hale 2008). Thus administration in the pre‐hospital setting typically occurs via medical or paramedical assistance, such as during ambulance transport. According to current guidelines its administration should be delivered with a targeted oxygen saturation rate and regular monitoring of patient response, though this is based largely on single studies and expert opinion (Beasley 2015). In the context of COPD, controlled supplemental oxygen (rather than high‐flow oxygen) is typically adequate to overcome hypoxia related to an AECOPD and avoid respiratory acidosis and hypercapnic respiratory failure (Brill 2014; O'Driscoll 2017). The amount of oxygen delivered to an individual can be described in a number of ways. Most commonly it is described as a flow rate, which refers to the number on the dial the health professional selects on the oxygen flow metre; or fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), which denotes the concentration of oxygen inhaled by the individual and is expressed as a percentage. A recent subgroup analysis has indicated that administration of six litres of oxygen per minute to people with COPD, who had a normal concentration of oxygen in their blood and suspected acute myocardial infarction, was of no benefit (Andell 2019). Non‐experimental studies indicate increased mortality with high‐flow oxygen therapy in the hospital and pre‐hospital setting (Denniston 2002; Wijesinghe 2011). Hence, a target SpO₂ (arterial oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximeter) range of 88% to 92% for the treatment of AECOPD is recommended in guidelines from Australia (Beasley 2015), Europe (Kane 2013), the UK (O'Driscoll 2017) and America (Rochwerg 2017). Oxygen can be administered via nasal cannulae or face masks, with nasal cannulae reported to be the simplest mode of administration as they are less likely to fall off and allow patients to speak while undergoing treatment (Brill 2014). Disadvantages to nasal cannulae, however, include patient reports of nasal dryness/epistaxis and discomfort as well as ineffectiveness due to mouth breathing, degree of nasal congestion and respiratory rate and/or minute volume (Brill 2014).

How the intervention might work

Administration of oxygen to people with COPD is intended to relieve hypoxaemia and as a mainstay of treatment for exacerbations is often delivered in conjunction with other treatments, including inhaled bronchodilators (Beasley 2015; Kane 2013; O'Driscoll 2017). Impairment of gas exchange and the development of respiratory failure may be precipitated by a variety of factors, one of which is the administration of oxygen at high concentrations. In this group of patients, the administration of high inspired concentrations of oxygen may cause a worsening of respiratory function, leading to further elevation of arterial carbon dioxide concentration (Donald 1949; McNicol 1965; Plant 2001). In addition, high‐flow oxygen may cause injury to other organs, such as the heart, and lead to morbidity and mortality through other mechanisms. Therefore, it is important for oxygen therapy to be controlled with monitoring to overcome hypoxia and prevent oxygen‐induced hypercapnia, according to patient needs (Brill 2014). Oxygen titration can be achieved through altering the oxygen flow rate or administering a mixture of air and oxygen in set proportions, with certain delivery devices, to allow the patient to breathe a known fraction of inspired oxygen (Brill 2014). When the appropriate level of oxygen is administered to reach the target SpO₂ of 88% to 92% in the pre‐hospital setting, this will relieve hypoxaemia and reduce the risk of mortality (Brill 2014).

Why it is important to do this review

Supplemental oxygen therapy in the emergency situation has traditionally been administered using "high‐flow" oxygen. This approach has been adopted on the basis that the population as a whole are at greater risk from failure to correct oxygenation than from its excessive administration. Indeed, for people with AECOPD, nebulised bronchodilators are often administered through a mask using oxygen at flows of 6 L/min to 8 L/min. A retrospective study found that the administration of an inspired oxygen concentration above 28% was associated with a 14% in‐hospital mortality rate, compared to 2% in‐hospital mortality for those administered a concentration of oxygen less than 28% (Denniston 2002). This has raised questions about the optimal delivery of oxygen to people with AECOPD in the pre‐hospital setting. One prospective prevalence study in the UK identified that one in five patients out of 983 admitted to hospital with AECOPD had respiratory acidosis (Plant 2000). A more recent cohort study of 415 patients with AECOPD conducted across Asia, Australia and New Zealand identified low compliance with blood gas testing, particularly in South East Asia, suggesting the potential for under‐diagnosis of clinically important hypercapnia, which may have implications for oxygen therapy (Kelly 2018). Therefore, the potential for high‐flow oxygen administration in the pre‐hospital setting, coupled with lack of blood gas testing to identify acidosis in the emergency department, presents a need for evidence consolidation around the application of oxygen therapy in the pre‐hospital setting. The results of this review will provide updated evidence for clinical practice guidelines and raise awareness of this important clinical issue.

Objectives

To determine the effect of different inspired oxygen concentrations ("high flow" compared to "controlled") in the pre‐hospital setting (prior to casualty/emergency department) on outcomes for people with acute exacerbations of COPD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for inclusion within this review, with full text and abstracts both accepted. There were no restrictions on language or publication date.

Types of participants

Studies were included that evaluated adults with AECOPD requiring medical or paramedical assistance in the pre‐hospital setting. AECOPD was defined as any combination of: an increase in breathlessness, sputum volume, sputum purulence, cough or wheeze. COPD itself was defined as spirometric evidence of airflow obstruction (forced expired volume in one second (FEV₁)/forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 0.7) plus a smoking history of greater than 10 pack history years; or disease matching an accepted standard definition (e.g. Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) or American Thoracic Society (ATS)). Studies were excluded if they investigated patients with acute asthma.

Types of interventions

Studies were included that evaluated high fractional inspired concentration (FiO₂) (greater than 28%) oxygen therapy compared to either: 1) placebo; 2) low FiO₂ (less than 28%) oxygen therapy; 3) titrated oxygen therapy; or 4) standard care.

In acknowledgement that oxygen therapy is rarely seen in isolation when treating AECOPD, additional medical treatment interventions (e.g. bronchodilators and corticosteroids) were accepted but were required to be standardised to both groups as far as possible.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Mortality (respiratory‐related and all‐cause)

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life

Arterial blood gas

Lung function (FEV₁/FVC)

Dyspnoea score (as measured by accepted clinical scales: Medical Research Council scale, Borg, Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire, Baseline Dyspnoea Index, St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire)

Treatment failure requiring intensive care unit (ICU), invasive or non‐invasive ventilation

Hospital utilisation (length of stay, readmission rate, emergency department presentations)

Reporting in the publications of one or more of the outcomes listed above was not an inclusion criterion for the review.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The previously published version of this review included searches up to August 2008 and did not find any studies for inclusion. The search period for this update is August 2008 to September 2019. For this update we searched the Cochrane Airways Specialised Register of trials up to 16 September 2019 through contact with the Information Specialist for the Group, using search terms relevant to this review. The Cochrane Airways Specialised Register contains studies identified from several sources:

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS Web);

Weekly searches of MEDLINE Ovid SP;

Weekly searches of Embase Ovid SP;

Monthly searches of PsycINFO Ovid SP;

Monthly searches of CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature);

Monthly searches of AMED EBSCO (Allied and Complementary Medicine);

Handsearches of the proceedings of major respiratory conferences.

Studies contained in the Specialised Register are identified through search strategies based on the scope of Cochrane Airways. Please see Appendix 1 for details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched conference proceedings. See Appendix 2 for search terms used to identify studies for this review.

A search of ClinicalTrials.gov (www.ClinicalTrials.gov) and the World Health Organization (WHO) trials portal (www.who.int/ictrp/en/) were also conducted. All sources were searched from inception, with no restriction on language of publication.

Searching other resources

We handsearched reference lists of all available included studies and review articles to identify potentially relevant citations and we made enquiries to authors of included studies regarding other published or unpublished trials known to them.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (ZK and KVC) independently screened the titles and abstracts returned from the literature search and separated them into the following groups: 'potential inclusion' or 'exclude not relevant'. Full text was obtained where possible for the studies in the 'potential inclusion group' and the same two review authors independently assessed them for inclusion. Excluded studies were either tagged as 'exclude not relevant' or 'exclude but relevant', with reasons for exclusion recorded. The authors encountered no disagreement during the study selection process, however, had there been disagreements these would have been resolved in consultation with a third review author. A PRISMA flow diagram was used to demonstrate the study selection process.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (ZK and KVC) independently extracted data for the included trial into a standardised, pilot tested data extraction form. Data extracted in duplicate included: study characteristics, outcome data and information on risk of bias. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. One review author (KVC) entered the data into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014) and these were double‐checked by ZK to ensure they were transferred correctly.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

In line with recommendations provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), two review authors (ZK and KVC) assessed the included study for risk of bias relating to random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and outcome assessors, handling of missing data, selective outcome reporting and other threats to study validity. An assessment of either high, unclear or low risk of bias was assigned to each domain with supporting justification recorded in the 'Risk of Bias' table. Disagreements during the 'Risk of bias' assessment process were resolved through discussion.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

This review has been revised to reflect current Cochrane reporting standards. All steps taken are described in the methods section of this publication. The original authors of this review (MA and RWB) are also the authors of the included study (Austin 2010); neither of them were involved in the extraction or interpretation of data from this study, this was solely completed by ZK and KVC.

Measures of treatment effect

Meta‐analysis was to be conducted where it would provide a meaningful outcome, e.g. where studies had sufficiently homogeneous methodology. Had there been enough studies for meta‐analysis, we would have extracted continuous and dichotomous data and analysed them in accordance with standard statistical techniques, with a random‐effects model for all studies deemed clinically and methodologically similar enough to be pooled. Had meta‐analysis been possible, mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence interval (CIs), and pooled MDs for standardised mean differences (SMDs), would have been calculated for continuous outcomes. Risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs would have been calculated for dichotomous outcomes.

Given there was only a single study for inclusion, a qualitative synthesis was conducted and all data were entered and synthesised using Review Manager 5 software, according to the pre‐specified protocol. Despite no meta‐analysis being conducted the data for all reported, relevant outcomes were used to create individual forest plots for visualisation of the data.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was considered to be the participant. Had there been sufficient studies for meta‐analysis, unit of analysis issues would have been addressed through the use of generic inverse variance and entering effect estimates and their standard errors, according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2019).

Dealing with missing data

Should there have been a need, missing information regarding participants on an available case analysis basis would have been conducted, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2019). If statistics essential for analysis were missing (e.g. when group means and standard deviations for both groups were not reported) and could not be calculated from other data, attempts would have been made to contact study authors to obtain missing data. In the event of loss of participants that occurred before baseline measurements were obtained, an assumption would have been made that this would have no effect on the final outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to assess statistical heterogeneity using a combination of methods, including visual inspection of data and use of the I² statistic. We would have judged an I² value of 50% or more to indicate the presence of substantial heterogeneity. Statistical significance would have been determined by the Der‐Simonian and Laird method of analysis presented with a P value less than 0.05 (Der Simonian 1986). We planned to investigate heterogeneity using pre‐specified subgroup analysis. Given no meta‐analyses were conducted in this review, heterogeneity was not assessed.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to explore potential reporting biases using a funnel plot had there been ten or more studies available for meta‐analysis. Instead, this was extrapolated as a possible risk of bias within the "other bias" section in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

Data synthesis

Data were combined from included trials using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014) software. Studies were reported by using intention‐to‐treat analysis when all participants who were randomly assigned during the study were assessed, regardless of whether they received the intervention/study treatment to which they were allocated.

Summary of findings table

A 'Summary of findings table' was constructed from the available data, using the following outcomes.

Mortality

Quality of life

Arterial blood gas

Lung function (FEV₁/FVC)

Dyspnoea score

Treatment failure requiring intensive care unit (ICU), invasive or non‐invasive ventilation

Hospital utilisation (length of stay, readmission rate, emergency department presentations)

Quality of the body of evidence was assessed according to the following five GRADE considerations.

Study limitations

Indirectness

Inconsistency of results

Imprecision of results

Publication bias

This assessment was undertaken in accordance with guidelines from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2019), using GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT). Justification for decisions regarding the upgrading or downgrading of evidence quality for each outcome was provided through footnotes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Had there been sufficient studies for meta‐analysis, we planned to conduct the following subgroup analyses.

High fractional inspired concentration oxygen therapy versus placebo

High fractional inspired concentration oxygen therapy versus low fractional inspired concentration oxygen

High fractional inspired concentration oxygen therapy versus titrated oxygen therapy

High fractional inspired concentration oxygen therapy versus standard care

Sensitivity analysis

Had there been sufficient studies for meta‐analysis, we planned to conduct the following sensitivity analyses.

Excluding studies at high risk of bias in one or more domain

Comparing a random‐effects with a fixed‐effect model

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Results

Description of studies

For additional information, see: Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of ongoing studies.

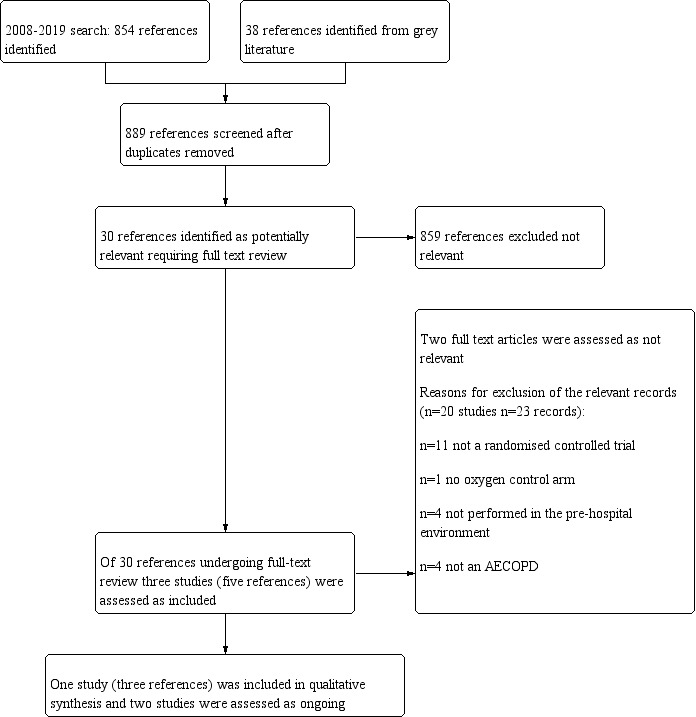

Results of the search

The previous version of this review did not identify any included studies. Through database searches conducted for this updated version, which covered the period from 2008 to 16 Septmber 2019, we identified a total of 854 records for screening. Thirty‐eight additional records were identified through screening of grey literature such as online clinical trial registries, producing a total of 889 records for review. On the basis of title and abstract, we excluded 794 records as they were not relevant. Full text was obtained for the remaining 30 records. Five records, representing one complete study and two ongoing studies, were found to be relevant and were included in the review. The remaining 23 records were assessed as excluded but relevant. For further details of screening processes, see the study flow diagram (Figure 2).

2.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

One study (three records) was identified for inclusion (Austin 2010). While this study enrolled 405 participants, only 214 of these had a diagnosis of AECOPD and it is this subset that has been included in analyses for this review. This study was a cluster‐randomised controlled, parallel‐group trial undertaken with the ambulance service in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. The study population was comprised of people aged 35 years or older with breathlessness and a history or risk of COPD. They were treated by paramedics, transported and admitted to the Royal Hobart Hospital.

Intervention

Participants received titrated oxygen treatment delivered by nasal prongs to achieve arterial oxygen saturations between 88% and 92%, with concurrent bronchodilator treatment delivered by a nebuliser driven by compressed air and delivered via a facemask over the nasal prongs. Pulse oximeters were used to measure oxygen saturations and titrate oxygen to target saturations. All participants received other standard treatment according to Tasmanian Ambulance Service guidelines, including basic support, nebulised bronchodilators (salbutamol 5 mg made up in 2.5 mL normal saline, ipratropium bromide 500 μg made up with 2.5 mL normal saline), dexamethasone 8 mg intravenously and, where necessary, salbutamol 200 mg to 300 mg intravenously or 500 mg intramuscularly.

Control

Participants in the control group received high‐flow oxygen treatment (8 L/min to10 L/min) administered by a non‐rebreather face mask and bronchodilators delivered by nebulization with oxygen at flows of 6 L/min to 8 L/min. Oximeters were used to measure oxygen saturation in those receiving high‐flow oxygen. All participants received other standard treatment according to Tasmanian Ambulance Service guidelines, including basic support, nebulised bronchodilators (salbutamol 5 mg made up in 2.5 mL normal saline, ipratropium bromide 500 μg made up with 2.5 mL normal saline), dexamethasone 8 mg intravenously and, where necessary, salbutamol 200 mg to 300 mg intravenously or 500 mg intramuscularly.

For more information about study characteristics, see Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

Twenty studies were identified as excluded but relevant to the review (23 records). The primary reason for exclusion was the lack of randomisation of participants, found in 11 studies (Characteristics of excluded studies). Three of these studies were reviews, one a clinical audit and the remaining studies were not randomised. Four studies were not conducted in the pre‐hospital setting, but instead were undertaken once patients were admitted to hospital; one study did not have an oxygen comparator arm; and the remaining four studies were not conducted in patient cohorts with a majority diagnosis of AECOPD (60% or more).

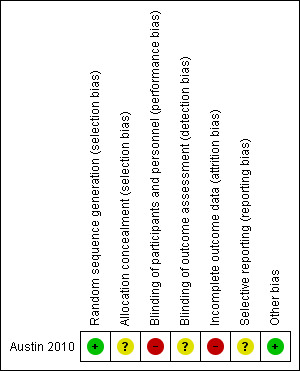

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias is reported for Austin 2010 and is displayed visually in Figure 3.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The method of sequence generation (computer random number generation after stratification by rurality) was assessed as being at low risk of bias. Allocation concealment was assessed as representing unclear risk of bias since the method of allocation was not reported; however, the study authors state that stratification by rurality was performed to reduce differences associated with transportation time between urban and rural areas, ensuring that treatment allocation was concealed before randomisation.

Blinding

The study authors report that paramedics, the research team and hospital staff were not blinded to treatment after randomisation. Therefore, we assessed the study as being at high risk of bias concerning blinding of participants. A respiratory physician blinded to treatment allocation reviewed lung function data and smoking history, from private and public medical records; however, no mention was made regarding the blinding for other outcome assessors so we assessed the study as being at unclear risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Data were reported to be missing from both the ambulance and hospital patient records, resulting in denominators varying among analyses. Intention‐to‐treat analysis occurred, however, we assessed this domain as high risk of bias.

Selective reporting

No study protocol was available to determine whether selective reporting occurred, therefore we assessed the study as being at unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Other potential sources of bias

No other biases were identified.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Titrated oxygen therapy compared to high‐flow oxygen therapy for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| Titrated oxygen therapy compared to high‐flow oxygen therapy for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: adults with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Setting: pre‐hospital setting Intervention: titrated oxygen therapy Comparison: high‐flow oxygen therapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with high‐flow oxygen therapy | Risk with titrated oxygen therapy | |||||

| Mortality (respiratory‐ related and all‐cause | 94 per 1,000 | 21 per 1,000 (5 to 91) | RR 0.22 (0.05 to 0.97) | 214 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 | A difference in mortality was observed, with 11 deaths in the high‐flow oxygen arm compared to two deaths in the titrated oxygen arm (P = 0.05). This translates to a number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) of 14 (95% CI 12 to 355) with administration of titrated oxygen therapy, and is shown as a Cates plot in Figure 1. All deaths occurred after arrival at the hospital; two were in intensive care. Respiratory failure was the cause of mortality in all cases, with approximately 70% of deaths occurring within the first five days following admission for both treatment arms. |

| Arterial blood gas (pH) | The mean arterial blood gas (pH) was 7.29 | MD 0.06 pH higher (0.04 lower to 0.16 higher) | ‐ | 214 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 | Based on the intention‐to‐treat analysis for the COPD subgroup, no significant difference between treatment arms for blood gas measurements was observed between groups (P = 0.23). Only 11% of participants had this measurement performed according to protocol. |

| Ventilation of any type | 143 per 1,000 | 96 per 1000 (41 to 221) | RR 0.67 (0.29 to 1.55) | 189 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | No significant difference observed between treatment arms for ventilation requirement for per protocol or intention‐to‐treat analyses. |

| Length of hospital stay | The mean length of hospital stay was 6.3 days | MD 0.88 days lower (2.25 lower to 0.49 higher) | ‐ | 214 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 | No significant difference was observed between treatment arms in length of hospital stay for the intention‐to‐treat analysis (P = 0.21). |

| Quality of life ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | This was not reported as an outcome in the single included study. |

| Lung function ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | This was not reported as an outcome in the single included study. |

| Dyspnoea score ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | This was not reported as an outcome in the single included study. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded once for indirectness because there was a single included study with moderate sample size (n = 214). The study was conducted in one state within Australia only. 2 Downgraded once for imprecision because a low number of events led to a wide CIs, with upper limit of the 95% CI approaching or including no difference.

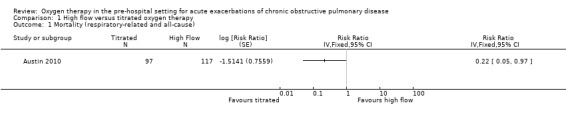

High flow versus titrated oxygen therapy

All data below are reported for the one included study (Austin 2010).

Primary outcome

Mortality (respiratory‐related and all‐cause)

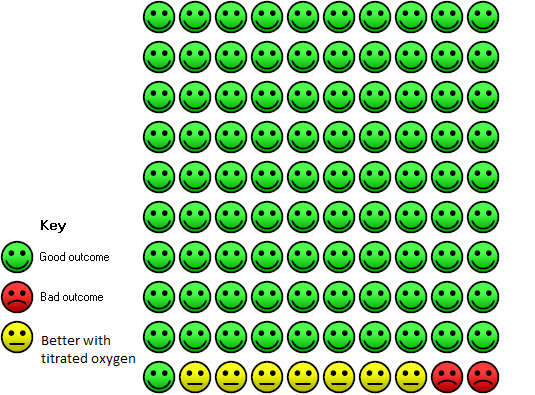

Among the cohort with confirmed AECOPD, a significant difference in pre/in‐hospital mortality was observed; there were 11 deaths out of 117 participants receiving high‐flow oxygen, compared to two deaths out of 97 participants receiving titrated oxygen (RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.97; 214 participants, 1 study; Analysis 1.1). This translates to a number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) of 14 (95% CI 12 to 355) with administration of titrated oxygen therapy, and is shown as a Cates plot in Figure 1. All deaths occurred after arrival at the hospital, including two in the emergency department and two in intensive care. As reported in the paper, the cause of mortality was respiratory failure in all cases, with approximately 70% of deaths occurring within the first five days following admission for both treatment arms.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 High flow versus titrated oxygen therapy, Outcome 1 Mortality (respiratory‐related and all‐cause).

1.

In the high‐dose oxygen group 9 people out of 100 died, compared to 2 (95% confidence interval 0 to 9) out of 100 for the titrated oxygen group.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life

Quality of life was not reported as an outcome in this study.

Arterial blood gas

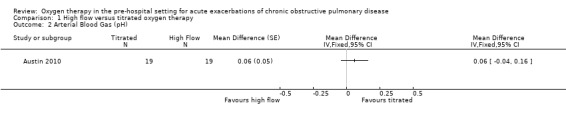

Based on the intention‐to‐treat analysis for the AECOPD subgroup, the difference between treatment arms for blood gas (pH) measurements observed between groups was uncertain (MD 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.16; 38 participants, 1 study; Analysis 1.2). Given that arterial blood gas was performed within 30 minutes of hospital arrival for only 11% of participants, it is important to note outcomes of the per‐protocol analysis. The per‐protocol analysis reported in the paper indicates significantly less respiratory acidosis (P = 0.01) and acute hypercapnia (P = 0.02) among participants receiving titrated oxygen (intervention) compared to those receiving high‐flow oxygen (control).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 High flow versus titrated oxygen therapy, Outcome 2 Arterial Blood Gas (pH).

Lung function

Lung function was not reported as an outcome in this study.

Dyspnoea score

Dyspnoea was not reported as an outcome in this study.

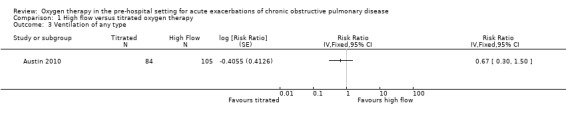

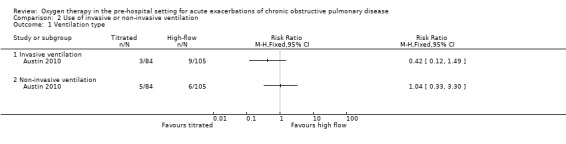

Treatment failure requiring intensive care unit (ICU), invasive or non‐invasive ventilation

The difference observed between treatment arms for ventilation of any type in the intention‐to‐treat analysis was uncertain (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.50; 189 participants, 1 study; Analysis 1.3); the within‐study subgroup analysis between invasive and non‐invasive ventilation is available in Analysis 2.1, however, this is not adjusted for clustering.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 High flow versus titrated oxygen therapy, Outcome 3 Ventilation of any type.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Use of invasive or non‐invasive ventilation, Outcome 1 Ventilation type.

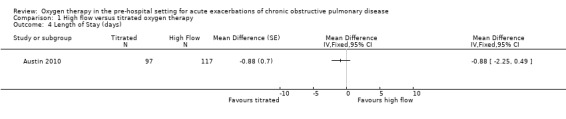

Hospital utilisation (length of stay, readmission rate, emergency department presentations)

The difference observed between treatment arms in length of hospital stay for the intention‐to‐treat analysis was also uncertain (MD ‐0.88 days, 95% CI ‐2.25 to 0.49; 214 participants, 1 study; Analysis 1.4). Other types of hospital utilisation were not reported as outcomes in this study.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 High flow versus titrated oxygen therapy, Outcome 4 Length of Stay (days).

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review update identified one new study that satisfied the pre‐defined inclusion criteria (Austin 2010). The study compared high‐flow oxygen therapy to a titrated approach in people with AECOPD in the pre‐hospital setting. Data from a subset of participants from Austin 2010 with a confirmed diagnosis of AECOPD were included for review. Two studies identified as ongoing in the original review were marked as awaiting classification (Eiser 2004; Elliott 2004) as there were no data available for analysis and attempts to contact the authors were unsuccessful. The included study was a well‐reported, well‐conducted Australian cluster‐RCT (Austin 2010).

For the primary outcome of mortality (respiratory‐related and all‐cause) there was a higher risk of death (9%; 11 individuals) with a high‐flow treatment approach compared to a titrated oxygen approach (2%; 2 individuals). All deaths were reportedly caused by respiratory failure and occurred once the patient arrived at hospital; 15% of reported deaths occurred in the emergency department and 15% occurred in the intensive care unit. With regard to arterial blood gas, Austin 2010 reported no evidence of an effect with high‐flow compared to titrated oxygen therapy in the intention‐to‐treat analysis; however, participants who were treated per protocol with a titrated oxygen therapy approach were less likely to have respiratory acidosis due to acute hypercapnia. There was no evidence of a difference between high‐flow and titrated oxygen therapy for the outcomes treatment failure requiring invasive or non‐invasive ventilation, or hospital utilisation.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The overall completeness and applicability of evidence was low given that only one study was identified for inclusion in this review, covering only one potential comparison (high‐flow versus titrated oxygen therapy) with a total of 214 participants with AECOPD. Furthermore, this study was conducted in a single metropolitan, high‐income setting with older participants (with a mean age of approximately 68 years) who had access to an ambulance service and as such generalisability of the results to other contexts may be limited.

The included study reported the primary outcome pre‐specified in our review (mortality (respiratory‐related and all‐cause)) and some of our secondary outcomes (arterial blood gas, hospital utilisation and treatment failure); however, several important secondary outcomes were not measured (e.g. quality of life, lung function and dyspnoea). While perhaps difficult to measure in a pre‐hospital/emergency setting, these outcomes are nevertheless clinically relevant and important when considering the impact of this intervention on the patient's burden of disease. Further, protocol violation is a concern in the included study; only 11% of participants had their arterial blood gas collected per protocol and over half of the titrated oxygen group received inappropriate high‐flow oxygen therapy during the study event. High levels of protocol violation are undesirable with the potential to confound the interpretation of results. Arguably in this instance erroneous administration of high‐flow oxygen to the titrated oxygen group would have lessened the treatment effect, however, a significant reduction in pre/in‐hospital mortality was still detected in favour of the titrated oxygen group.

No studies were identified that compared high‐flow oxygen to placebo or standard care, though this is not surprising considering the ethical considerations of withholding first‐line treatment from a participant suffering with AECOPD. No studies were found evaluating the effect of low‐flow oxygen therapy. The findings of this review are therefore limited by a paucity of available data and an inability to assess all pre‐defined outcomes.

Certainty of the evidence

The certainty of the evidence was low. Certainty was downgraded in the domain of indirectness, because of the inclusion of only one study that included participants from only one location and health service. We further downgraded the certainty of the evidence for imprecision, because the low number of events resulted in wide confidence intervals with the upper limits approaching or including no difference. Other domains assessed, including risk of bias, inconsistency and publication bias, presented no cause for us to downgrade our assessment of certainty. Furthermore, the moderate sample size (214 participants) and methodologically rigorous study design does facilitate the ability to draw some conclusions for clinical practice in the absence of other available data.

Potential biases in the review process

Every effort was made to reduce the impact of bias on this review. A pre‐specified methodology was adhered to based on Cochrane standards (Higgins 2011). The systematic search for this review was conducted through diverse means (i.e. electronic databases, conference proceedings, author contact and online clinical trial registries) by an experienced Information Specialist and experienced review team in order to identify all available and potentially relevant studies. However, considering the lack of available evidence returned by this search, it is likely that some publication bias was introduced leading to over‐ or under‐estimation of the intervention effects, or indeed the inability to report on some outcomes altogether. From the original publication of this review, two studies have been moved from ongoing to awaiting classification (Eiser 2004; Elliott 2004). This is likely illustrative of the difficulty authors face in having their results published and the ultimate lack of evidence available for inclusion in this review. Attempts were made to overcome this by contacting the authors or listed contact persons (or both) for these studies; however, no responses were received.

While there may have been potential for false exclusion of relevant studies and data entry error, steps were taken to mitigate this by having two independent authors screen, extract and check data entry performed. The only included study was written by the two original authors of this review (MA and RW). The publication of Austin 2010 occurred subsequent to this review. As a result, this may have been a source of bias, however, to mitigate this issue MA and RW were not involved in any capacity for protocol revision, study screening and selection, data extraction and analysis of the included and excluded studies.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The traditional approach to treatment of patients with shortness of breath is high‐flow oxygen adopted on the basis that the population as a whole are at greater risk from failure to correct oxygenation than from its excessive administration (Kane 2013). The results of this review somewhat support a retrospective study (Denniston 2002) that found that the administration of an inspired oxygen concentration above 28% was associated with a higher in‐hospital mortality (of 14%) than administration of a concentration of oxygen less that 28% (mortality of 2%). Though Denniston 2002 did not directly assess titrated oxygen therapy, it suggested that the continued use of a high‐flow approach was no longer appropriate. However, the non‐randomised design meant that the results could have been confounded by the severity of illness influencing the choice of oxygen concentration used. The studies identified in this review as awaiting classification have, as with many pre‐hospital studies, experienced difficulties with design, implementation and compliance of staff. This is likely a result of entrenched habits of treating paramedics. Future studies attempting a similar undertaking may consider engaging organisational executives in endorsing the study and its methods, to encourage adoption of the protocol and overcome reservations about change of practice to an experimental treatment option. Further, measurements may be best performed by a researcher rather than left to clinical staff to ensure quality data and results. This observation, however, should not prevent researchers, health professionals and policy makers from striving to obtain evidence to identify the optimal oxygen treatment for AECOPD.

Recently, guideline recommendations have moved away from high‐flow oxygen therapy in AECOPD in general, towards a more titrated approach (Beasley 2015; Kane 2013; O'Driscoll 2017). It appears that there is a current tendency toward risk‐adverse practice culture as this recommendation is presently supported by only single, predominantly non‐randomised, studies; our review (which identified only one RCT) only serves to support this. Given the included RCT was published in 2010, and recent literature searches uncover no new studies, it is perhaps reasonable to presume that given the stakes the existing evidence for a titrated approach to oxygen delivery is considered widely to be 'good enough' in the absence of a clear demonstrable benefit to administration of high‐flow oxygen in this population.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Only one relevant randomised controlled trial has been published on this topic to date; thus there is a paucity of evidence to conclude that different oxygen therapies in the pre‐hospital setting (prior to casualty/emergency department) alters outcomes in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD). However, the results seen suggest that a titrated oxygen therapy approach (via nasal prongs to achieve arterial saturation of 88% to 92%) may have some benefits over high‐flow oxygen (mask delivered, 8 L/min to 10 L/min) with respect to reduced risk of death and respiratory acidosis. Practitioners and policy makers may wish to consider the addition of a titrated approach as a treatment option to the standard of care, moving away from the 'more is better' approach to prescribing oxygen for AECOPD. However, more studies would be beneficial in strengthening the certainty of the evidence presented in this review before completely moving away from existing treatment recommendations.

Implications for research.

More evidence is required to optimise the management of people with AECOPD and provide increased generalisability to the findings of this review. Given that it may be considered unethical to conduct placebo controlled trials within this context, however, it is unlikely that future studies will take this approach. Furthermore, the study included in this review was well‐conducted and the results of this single trial have impacted practice and current guidelines such that further evaluation of high‐flow oxygen therapy may also be deemed unethical. Despite this, the study included in this review lacks wide generalisability and should be replicated if possible to include a greater spectrum of COPD severities in a multicentre study. The potential for a three‐armed study including high‐flow, titrated and low‐flow oxygen therapy (or even non‐invasive ventilation) for AECOPD in the pre‐hospital setting is also interesting. More broadly, the findings of this review provide an interesting comment on the lack of evidence underpinning elements of routine practice for AECOPD and given that oxygen therapy is a cornerstone of treatment, it may be beneficial to expand the area of enquiry beyond the pre‐hospital setting and into the acute hospital setting.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 September 2019 | New search has been performed | A new literature search was conducted. |

| 16 September 2019 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | We included one study in this update. The inclusion criteria were changed to include standard care and titrated oxygen therapy. We also updated the methods to meet current Cochrane standards. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2005 Review first published: Issue 3, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 September 2008 | New search has been performed | Literature search re‐run; no new studies found |

| 15 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 4 April 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the Cochrane Airways Group editorial base for support: Elizabeth Stovold for conducting the electronic searches, Emma Dennett, Emma Jackson, Rebecca Normansell and Chris Cates for editorial support. We would also like to thank Dr Julia Walters for advice and support.

The Background and Methods sections of this review are based on a standard template used by Cochrane Airways.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Airways Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS, or the Department of Health.

The authors acknowledge Brian J Smith (Bendigo Hospital, Australia) for his review of an early version of the discussion section of this update.

The authors and Cochrane Airways editorial team are grateful to the following peer reviewers for their time and comments.

Begum Ergan (Dokuz Eylul University Medical School, Turkey)

Josefin Sundh (Örebro University, Sweden)

Magnus Ekström (Lund University, Sweden)

Nausherwan K Burki (UConn Health, USA)

Appendices

Appendix 1. Sources and search methods for the Cochrane Airways Specialised Register of Trials

Electronic searches: core databases

| Database | Dates searched | Frequency of search |

| CENTRAL (via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS)) | From inception | Monthly |

| MEDLINE (Ovid) | 1946 onwards | Weekly |

| EMBASE (Ovid) | 1974 onwards | Weekly |

| PsycINFO (Ovid) | 1967 onwards | Monthly |

| CINAHL (EBSCO) | 1937 onwards | Monthly |

| AMED (EBSCO) | From inception | Monthly |

Handsearches: core respiratory conference abstracts

| Conference | Years searched |

| American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) | 2001 onwards |

| American Thoracic Society (ATS) | 2001 onwards |

| Asia Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR) | 2004 onwards |

| British Thoracic Society (BTS) | 2000 onwards |

| Chest Meeting | 2003 onwards |

| European Respiratory Society (ERS) | 1992, 1994, 2000 onwards |

| International Primary Care Respiratory Group Congress (IPCRG) | 2002 onwards |

| Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) | 1999 onwards |

MEDLINE search strategy used to identify trials for the CAGR

COPD search

1. Lung Diseases, Obstructive/

2. exp Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive/

3. emphysema$.mp.

4. (chronic$ adj3 bronchiti$).mp.

5. (obstruct$ adj3 (pulmonary or lung$ or airway$ or airflow$ or bronch$ or respirat$)).mp.

6. COPD.mp.

7. COAD.mp.

8. COBD.mp.

9. AECB.mp.

10. or/1‐9

Filter to identify RCTs

1. exp "clinical trial [publication type]"/

2. (randomized or randomised).ab,ti.

3. placebo.ab,ti.

4. dt.fs.

5. randomly.ab,ti.

6. trial.ab,ti.

7. groups.ab,ti.

8. or/1‐7

9. Animals/

10. Humans/

11. 9 not (9 and 10)

12. 8 not 11

The MEDLINE strategy and RCT filter are adapted to identify trials in other electronic databases

Appendix 2. Search strategy for the Cochrane Airways Group Register

Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS)

#1. MeSH DESCRIPTOR Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive Explode All #2. MeSH DESCRIPTOR Bronchitis, Chronic #3. (obstruct*) near3 (pulmonary or lung* or airway* or airflow* or bronch* or respirat*) #4. COPD:MISC1 #5. (COPD OR COAD OR COBD):TI,AB,KW #6. #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 #7. MeSH DESCRIPTOR Emergency Medicine #8. MeSH DESCRIPTOR Emergency Medical Services Explode All #9. emergenc* or emergicent* or emergi‐cent* or prehospital* or pre‐hospital* #10. ambulance* or (patient* NEAR transport*) #11. first‐aid* or first NEXT aid* #12. #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 #13. (inhal* or respiratory*) NEAR therap* #14. oxygen* #15. "nasal cannula*" or "nasal prong*" or NRM or venture* or Hudson* or mask* #16. MeSH DESCRIPTOR Oxygen Inhalation Therapy Explode All #17. MeSH DESCRIPTOR Respiratory Therapy ambulance* #18. MeSH DESCRIPTOR Oxygen #19. #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 #20. #6 and #12 and #19

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. High flow versus titrated oxygen therapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mortality (respiratory‐related and all‐cause) | 1 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Arterial Blood Gas (pH) | 1 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Ventilation of any type | 1 | Risk Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Length of Stay (days) | 1 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 2. Use of invasive or non‐invasive ventilation.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ventilation type | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Invasive ventilation | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Non‐invasive ventilation | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Austin 2010.

| Methods |

Country: Australia Design: cluster‐randomised controlled parallel‐group trial Objective: to compare standard high‐flow oxygen treatment with titrated oxygen treatment for patients with an AECOPD in the pre‐hospital setting Methods of analysis: log binomial regression to compare the risk of death for patients in two treatment arms (primary outcome). Secondary outcomes were analysed using Student’s t‐tests after transformation to remove skewness. Ventilation categories were combined with log binomial regression used to compare them due to a small number of observations. Both intention‐to‐treat and per protocol analyses were used (initial analyses were intention to treat) Clustering adjustments made: cluster randomisation used to assign paramedics to one of the treatment groups. Standard errors were adjusted to account for correlation between observations for the same paramedic (clustering) Was the significance of any affect altered due to clustering: not reported |

|

| Participants |

Eligible for study: n = 63 full‐time paramedic staff eligible; n = 405 eligible patients Randomised: intervention: n = 32 paramedics; n = 179 patients with breathlessness; n = 97 with AECOPD. Control: n = 30 paramedics; n = 226 patients with breathlessness; n = 117 with AECOPD Completed: intervention: n = 117 for intention‐to‐treat; n = 92 for per protocol analysis. Control: n = 97 for intention to treat; n = 43 for per protocol analysis Age: intervention: mean 67.9 + 10.3; control: mean 68.0 + 10.2 Gender: intervention: n = 45 male; n = 52 female. Control: n = 57 male n = 60 female COPD diagnosis definition: paramedics determined diagnosis based on appropriate acute symptoms, history of COPD (or emphysema) from the patient or a greater than 10 pack year history of smoking. The COPD cohort had a definite diagnosis of COPD defined by national guidelines. Patients without lung function data or who did not fulfil spirometric criteria for COPD were excluded from the COPD subgroup analysis. Diseases/comorbidities included: not reported Reasons for subject exclusion: aged less than 35 years |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention description: patients received titrated oxygen treatment delivered by nasal prongs to achieve arterial oxygen saturations between 88% and 92%, with concurrent bronchodilator treatment delivered by a nebuliser driven by compressed air and delivered via a facemask over the nasal prongs. Pulse oximeters were used to measures oxygen saturations and titrate oxygen to target saturations. All patients received other standard treatment according to Tasmanian Ambulance Service guidelines, including basic support, nebulised bronchodilators (salbutamol 5 mg made up in 2.5 mL normal saline, ipratropium bromide 500 μg made up with 2.5 mL normal saline), dexamethasone 8 mg intravenously and where necessary salbutamol 200 mg to 300 mg intravenously or 500 mg intramuscularly Control description: high‐flow oxygen treatment (8 L/min to 10 L/min) administered by a non‐rebreather face mask and bronchodilators delivered by nebulisation with oxygen at flows of 6 L/min to 8 L/min. Oximeters were used to measure oxygen saturation in the high‐flow oxygen arm. All patients received other standard treatment according to Tasmanian Ambulance Service guidelines, including basic support, nebulised bronchodilators (salbutamol 5 mg made up in 2.5 mL normal saline, ipratropium bromide 500 μg made up with 2.5 mL normal saline), dexamethasone 8 mg intravenously and where necessary salbutamol 200 mg to 300 mg intravenously or 500 mg intramuscularly Duration of intervention: during ambulance delivery from patients location to hospital Setting: pre‐hospital setting (ambulance) |

|

| Outcomes |

List of pre‐specified outcomes: pre‐hospital and in‐hospital mortality, length of hospital stay, blood gas measurements (pH, arterial carbon dioxide, bicarbonate and arterial oxygen) Follow‐up period: pre‐hospital duration |

|

| Notes | Funding: provided by the Australian College of Ambulance Professionals (ACAP), nebulisation air compressors donated by FlaemNova. Authors note that neither sponsor had a role in the study conduct or publication of results. This study was retrospectively registered online, the record can be viewed here. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer random number generation after stratification by rurality |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of allocation concealment not reported, however, authors state that stratification by rurality was performed to reduce differences associated with transportation time between urban and rural areas, ensuring that treatment allocation was concealed before randomisation |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Paramedics, the research team and hospital staff were not blinded to treatment after randomisation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | A respiratory physician blind to treatment allocation reviewed lung function data and smoking history, from private and public medical records. No mention of blinding for other outcome assessors |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Data were reported to be missing from both the ambulance and hospital patient records, resulting in denominators varying among analyses. Intention‐to‐treat analysis occurred |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No pre‐specified protocol available to determine selective reporting |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other biases identified |

AECOPD: acute exacerbations of COPD COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bell 2015 | Not a pre‐hospital study |

| Costello 1997 | Clinical audit of outcomes |

| Curtis 1994 | Narrative review |

| Denniston 2002 | Participants not randomised |

| Emerman 1989 | Not compared with oxygen |

| Esteban 1993 | Not a pre‐hospital study |

| Gomersall 2002 | Not a pre‐hospital study |

| L'Her 2017 | Not AECOPD |

| McNally 1993 | Not an RCT of oxygen levels |

| Moloney 2001 | Participants not randomised |

| Murphy 2001 | Participants not randomised |

| Murphy 2001a | Participants not randomised |

| O'Driscoll 2003 | Participants not randomised |

| O'Reilly 2003 | Narrative review |

| Rittayamai 2015 | Not AECOPD |

| Schumaker 2004 | Review of evidence |

| Small 2000 | Participants not randomised |

| Van der Elst 1982 | Not AECOPD |

| van der Elst 1985 | Not AECOPD |

| Wu 2014 | Not a pre‐hospital study |

AECOPD: acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease RCT: randomised controlled trial

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Eiser 2004.

| Methods | Consenting patients will be randomised to receive either standard oxygen therapy or an adjusted oxygen flow rate to achieve a saturation between 88% and 92%. Half of ambulance crews will be trained to administer controlled oxygen and randomisation will be based on which ambulance crew is called to the patient. |

| Participants | All patients presenting with symptoms of exacerbation of COPD conveyed to Lewisham Hospital by London Ambulance Service Emergency Medical Technicians meeting the following criteria: age; 45 years, have inhaler/nebuliser for regular home use, breathless on exertion of Medical Research Council (MRC) scale grade 2 or above when well, have a current or past smoking history. |

| Interventions | Oxygen therapy to maintain oxygen saturation between 88% and 92% |

| Outcomes | Primary: blood pH Secondary: need for intubation and mechanical ventilation, need for non invasive ventilation, hospital length of stay and survival |

| Notes | Previously listed as ongoing in Austin 2006. No publication was found despite searching; the study authors were contacted with no response. |

Elliott 2004.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Random allocation to A) usual oxygen therapy or B) oxygen flow rate adjusted to achieve a saturation between 88% and 92%. |

| Participants | Patients who may have an exacerbation of COPD. Patients who can answer "yes" to the following questions: 1) age > 45; 2) having an inhaler or nebuliser for regular home use; 3) breathlessness on exertion of MRC grade 2 or above when well; 4) a current or past of smoking |

| Interventions | Oxygen therapy to maintain oxygen saturation between 88% and 92% |

| Outcomes | To establish whether oxygen delivery given to achieve a specific oxygen saturation and nebulised drugs given via a compressor (standard practice on respiratory wards at St James's) results in fewer patients presenting to hospital acidotic or needing ventilation |

| Notes | Previously listed as ongoing in Austin 2006. No publication was found despite searching; the study authors were contacted with no response. |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Differences between protocol and review

This review has undergone significant revisions to style and methodology from the original review (Austin 2006). This was undertaken to ensure the review reflects current Cochrane methodological standards.

For this review we used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool instead of the Jadad scale, and added a PRISMA diagram and 'Summary of findings' table. We also refined and consolidated the list of outcomes. The original primary outcome was mortality from respiratory causes this was updated to include all causes. The secondary outcomes of mental status score, consciousness score and illness score were replaced with quality of life; intensive care unit admission, invasive ventilation and non‐invasive ventilation were consolidated under treatment failure and duration of hospitalisation was amended to reflect broader hospital utilisation. We further defined the lung function outcome to state FEV1/FVC as the measure. Further, standard care was added to the list of accepted comparison interventions. We also specified that a random‐effects model would be used for the primary analyses and compared to the fixed‐effect model in a sensitivity analysis, and we further clarified the criteria for the planned sensitivity analysis based on risk of bias. Data extraction methods were updated to reflect current practice, with two independent reviewers performing extractions for the included study instead of one.

Contributions of authors

MA and RWB wrote and developed the initial protocol and published the first version of the review in 2008. ZK and KVC updated the protocol, screened literature, conducted data extraction, analysed the evidence and drafted the manuscript for the 2018 review update. MA and RWB provided clinical input and reviewed the draft manuscript for the 2019 update.

Contributions of editorial team

Rebecca Fortescue (Co‐ordinating Editor) edited the review and advised on methodology, interpretation and content. Chris Cates (Co‐ordinating Editor) checked the data entry prior to the full write‐up of the review and approved the final review prior to publication. Brian Rowe (Contact Editor) edited the review and advised on methodology, interpretation and content. Emma Dennett (Managing Editor) co‐ordinated the editorial process; advised on interpretation and content; and edited the review. Emma Jackson (Assistant Managing Editor) conducted peer review; obtained translations; and edited the 'Plain language summary' and 'References' sections of the protocol and the review. Elizabeth Stovold (Information Specialist) designed the search strategy; ran the searches; and edited the 'Search methods' section.

Sources of support

Internal sources

The authors declare that no such funding was received for this systematic review, Other.

External sources

The authors declare that no such funding was received for this systematic review, Other.

Declarations of interest

MA and RWB were authors on the one included study (Austin 2010). Thus, they were not involved in any capacity for protocol revision, study screening and selection, data extraction and analysis of the included and excluded studies.

ZK: none known KVC: none known MAA: none known RW‐B: none known

New search for studies and content updated (conclusions changed)

References

References to studies included in this review

Austin 2010 {published data only}

- Austin MA, Wills KE, Blizzard L, Walters EH, Wood‐Baker R. Effect of high flow oxygen on mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in prehospital setting: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;341:c5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Bell 2015 {published data only}

- Bell N, Hutchinson CL. Randomised control trial of humidified high flow nasal cannulae versus standard oxygen in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Australasia 2015;27:537‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Costello 1997 {published data only}

- Costello R, Deegan P, Fitzpatrick M, McNicholas W. Reversible hypercapnia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A distinct pattern of respiratory failure with a favorable prognosis. American Journal of Medicine 1997;102(3):239‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Curtis 1994 {published data only}

- Curtis J, Hudson L. Emergent assessment and management of acute respiratory failure in COPD. Clinics in Chest Medicine 1994;15(3):481‐500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Denniston 2002 {published data only}

- Denniston A, O'Brien C, Stableforth D. The use of oxygen in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective audit of pre‐hospital and hospital emergency management. Clinical Medicine 2002;2(5):449‐51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Emerman 1989 {published data only}

- Emerman C, Connors A, Lukens T, Effron D, May M. Relationship between arterial blood gases and spirometry in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annals of Emergency Medicine 1989;18(5):523‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Esteban 1993 {published data only}

- Esteban A, Cerda E, Cal M, Lorente J. Hemodynamic effects of oxygen therapy in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest 1993;104(2):471‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gomersall 2002 {published data only}

- Gomersall C, Joynt G, Freebairn R, Lai C, Oh T. Oxygen therapy for hypercapnic patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and acute respiratory failure: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Critical Care Medicine 2002;30(1):113‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

L'Her 2017 {published data only}

- L'Her E, Dias P, Gouillou M, Paleiron N, Archambault P, Bouchard PA, et al. Automated oxygen titration in patients with acute respiratory distress at the emergency department. An international randomized controlled study. European Respiratory Journal 2015;46(S59):OA3260. [Google Scholar]

- L'Her E, Dias P, Gouillou M, Paleiron N, Archambault P, Bouchard PA, et al. Automation of oxygen titration in patients with acute respiratory distress at the emergency department. A multicentric international randomised controlled study. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental 2015;3(1):A424. [Google Scholar]

- L'Her E, Dias P, Gouillou M, Paleiron N, Archambault P, Bourhcard PA, et al. Automatisation of oxygen titration in patients with acute respiratory distress at the emergency department. A multicentric international randomized controlled study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2015;191:A6329. [Google Scholar]

- L'Her E, Dias P, Gouillou M, Riou A, Souquierer L, Paleiron N, et al. Automatic versus manual oxygen administration in the emergency department. European Respiratory Journal 2017;50(1):1602552. [DOI: 10.1183/13993003.02552-2016] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McNally 1993 {published data only}

- McNally E, Fitzpatrick M, Bourke S, Costello R, McNicholas W. Reversible hypercapnia in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). European Respiratory Journal 1993;6(9):1353‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moloney 2001 {published data only}

- Moloney E, Kiely J, McNicholas W. Controlled oxygen therapy and carbon dioxide retention during exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2001;357(9255):526‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Murphy 2001 {published data only}

- Murphy R, Mackway‐Jones K, Sammy I, Driscoll P, Gray A, O'Driscoll R, et al. Emergency oxygen therapy for the breathless patient. Guidelines prepared by North West Oxygen Group. Emergency Medicine Journal 2001;18(6):421‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Murphy 2001a {published data only}

- Murphy R, Driscoll P, O'Driscoll R. Emergency oxygen therapy for the COPD patient. Emergency Medicine Journal 2001;18(5):333‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O'Driscoll 2003 {published data only}

- O'Driscoll R, Wolstenholme R, Pilling A, Bassett C, Singer M, Bellingan G, et al. The use of oxygen in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A prospective audit of pre‐hospital and hospital emergency management. Clinical Medicine 2003;3(2):183‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O'Reilly 2003 {published data only}

- O'Reilly J. Emergency management of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. CPD Journal Acute Medicine 2003;2(1):3‐8. [Google Scholar]

Rittayamai 2015 {published data only}

- Rittayamai N, Tscheikuna J, Praphruetkit N, Kijpinyochai S. Use of high‐flow nasal cannula for acute dyspnea and hypoxemia in the emergency department. Respiratory Care 2015;60(10):1377‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schumaker 2004 {published data only}

- Schumaker G, Epstein S. Managing acute respiratory failure during exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiratory Care 2004;49(7):766‐82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Small 2000 {published data only}

- Small G, Barsby P. How much is enough? Emergency oxygen therapy with COPD. Emergency Nurse 2000;8(8):20‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Van der Elst 1982 {published data only}

- Elst A, Kreukniet J. Some aspects of the oxygen transport in patients with chronic obstructive lung diseases and respiratory insufficiency. Respiration 1982;43(5):336‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

van der Elst 1985 {published data only}

- Elst A, Werf T. Some circulatory aspects of the oxygen transport in patients with emphysema. Respiration 1985;48(4):310‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wu 2014 {published data only}

- Wu W, Hong H, Shao X, Rui L, Jing M, Lu G. Effect of oxygen‐driven nebulization at different oxygen flows in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. American Journal of Medical Sciences 2014;347(5):343‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Eiser 2004 {unpublished data only}

- Eiser DN. Comparison of controlled oxygen with standard oxygen therapy for COPD patients during ambulance transfer to hospital. London Ambulance Service NHS Trust 2004.

Elliott 2004 {unpublished data only}

- Elliott DM. A prospective randomised controlled trial of oxygen targeted to maintain an oxygen saturation between 88 and 92% compared with standard therapy for patients with COPD during ambulance transfer to hospital. Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust 2004. [N0436146646]

Additional references

Abdo 2012