Abstract

Background

Risperidone, an atypical antipsychotic, is used to treat mania both alone and in combination with other medicines.

Objectives

To review the efficacy and tolerability of risperidone as treatment for mania.

Search methods

The Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Controlled Trials Register (CCDANCTR‐Studies December 2004), The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), EMBASE, MEDLINE, CINAHL and PsycINFO were searched in December 2004. Reference lists and English language textbooks were searched; researchers in the field and Janssen‐Cilag were contacted.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing risperidone with placebo or other drugs in acute manic or mixed episodes.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently extracted data from trial reports. Janssen‐Cilag was asked to provide missing information.

Quality assessment As in other trials of treatment for mania, the high proportion of imputed efficacy data resulting from rates of failure to complete treatment of between 12% and 62% may have biased the results.

Main results

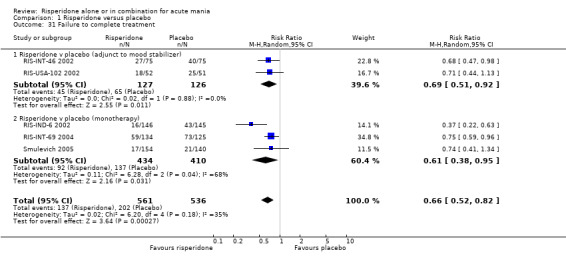

Six trials (1343 participants) of risperidone as monotherapy or as adjunctive treatment to lithium, or an anticonvulsant, were identified. Permitted doses were consistent with those recommended by the manufacturers of Haldol (haloperidol) and Risperdal (risperidone) for treatment of mania and trials involving haloperidol allowed antiparkinsonian treatment. Risperidone monotherapy was more effective than placebo in reducing manic symptoms, using the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (weighted mean difference (WMD) ‐5.75, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐7.46 to ‐4.04, P<0.00001; 2 trials) and in leading to response, remission and sustained remission. Effect sizes for monotherapy and adjunctive treatment comparisons were similar. Low levels of baseline depression precluded reliable assessment of efficacy for treatment of depressive symptoms. Risperidone as monotherapy and as adjunctive treatment was more acceptable than placebo, with lower incidence of failure to complete treatment (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.82, P = 0.0003; 5 trials). Overall risperidone caused more weight gain, extrapyramidal disorder, sedation and increase in prolactin level than placebo.

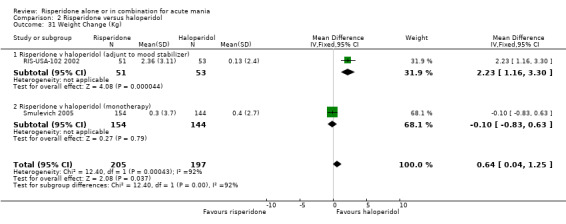

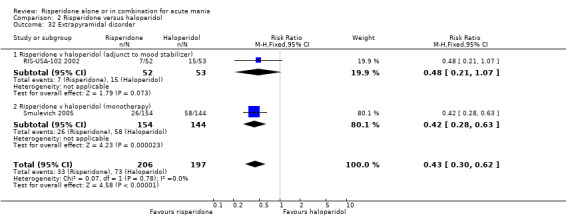

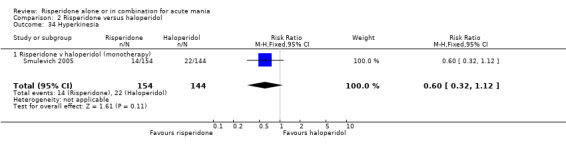

There was no evidence of a difference in efficacy between risperidone and haloperidol either as monotherapy or as adjunctive treatment. The acceptability of risperidone and haloperidol in incidence of failure to complete treatment was comparable. Overall risperidone caused more weight gain than haloperidol but less extrapyramidal disorder and comparable sedation.

Authors' conclusions

Risperidone, as monotherapy and adjunctive treatment, is effective in reducing manic symptoms. The main adverse effects are weight gain, extrapyramidal effects and sedation. Risperidone is comparable in efficacy to haloperidol.

Higher quality trials are required to provide more reliable and precise estimates of its costs and benefits.

Plain language summary

Risperidone alone or in combination for acute mania

This review included six trials and investigated the efficacy and tolerability of risperidone, an atypical antipsychotic, as treatment for mania compared to placebo or other medicines. High withdrawal rates from the trials limit the confidence that can be placed on the results. Risperidone, both as monotherapy and combined with lithium, or an anticonvulsant, was more effective at reducing manic symptoms than placebo but caused more weight gain, sedation and elevation of prolactin levels. The efficacy of risperidone was comparable to that of haloperidol both as monotherapy and as adjunctive treatments to lithium, or an anticonvulsant. Risperidone caused less movement disorders than haloperidol but there was some evidence for greater weight gain.

Background

Bipolar disorder is a mental disorder characterised by episodes of elevated or irritable mood (manic or hypomanic episodes) and episodes of low mood, loss of energy and sadness (depressive episodes). Some people also experience mixed episodes in which manic and depressive symptoms are present at the same time. Psychotic symptoms may occur in mania and are called mood‐congruent when they occur during a manic episode and are consistent with the mood disturbance. Manic episodes may also occur in patients who have symptoms of both schizophrenia and mood disorder (schizoaffective disorder).

The costs of manic episodes are high both for patients and for health services. For patients, in addition to the period of acute illness, manic episodes often leave an aftermath of psychological, social and financial problems. Direct medical costs are high because admission to a psychiatric intensive care unit is often necessary. Drugs are the first line treatment for acute mania. The main objectives in treating mania are to control dangerous behaviour, produce appropriate acute sedation and shorten the episode of mood disturbance. A number of different drugs are used in the treatment of mania ‐ either as monotherapy or in combination. Lithium has been used to treat mania for many years and has been shown to be effective (Goodwin 1990). Antipsychotics (also called neuroleptics, major tranquilisers) have been used for many years, particularly when mania is accompanied by psychosis. In North America antipsychotics are usually considered as adjunctive to primary therapy with a "mood stabiliser" such as lithium or valproate. By contrast, in Europe antipsychotics are usually themselves considered to be a primary therapy for mania, either alone or in combination with mood stabilisers. All drug treatments for mania are potentially associated with serious adverse effects and a risk of precipitating depression. The recognised adverse effects of conventional antipsychotics include movement disorders (Extra Pyramidal Symptoms (EPS), parkinsonian symptoms, dystonia, akathisia, tardive dyskinesia); neuroleptic malignant syndrome; EEG changes; cardiovascular problems (hypotension, tachycardia, arrhythmias) and alterations in liver function. Nevertheless, compared to lithium, antipsychotics are sometimes considered to possess a wider ratio between doses that possess efficacy and those that induce side‐effects and this is important in the treatment of patients with mania. The rapid control of agitation and overactivity may be offset by the risks of serious adverse effects and poor tolerability. Newer "atypical antipsychotics" (olanzapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, quetiapine, clozapine, amisulpiride, sertindole and zotepine) may be an important advance if they share the advantages of the older antipsychotics in mania, but have fewer adverse effects.

Risperidone is an atypical antipsychotic. In the treatment of schizophrenia there is evidence that risperidone may be more acceptable and slightly more efficacious than typical antipsychotics but there are concerns that it causes weight gain (Kennedy 2002). From the limited evidence available, no clear difference was seen between risperidone and other atypical antipsychotics (Gilbody 2002).

This systematic review will assess the evidence for the efficacy and tolerability of risperidone compared to placebo and other treatments.

Objectives

1. To determine the efficacy of risperidone compared with placebo or other active treatment in alleviating the acute symptoms of manic or mixed episodes.

2. To review the effect of risperidone on general health and social functioning.

3. To review acceptability of treatment with risperidone.

4. To investigate the adverse effects of treatment with risperidone.

5. To determine overall mortality rates on treatment with risperidone.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials which compared risperidone with placebo or other active treatments. For trials with a crossover design only results from the first randomisation period were considered.

Types of participants

Patients of both sexes and all ages with a diagnosis of bipolar or schizoaffective disorder: manic or mixed episode, however diagnosed, with or without psychotic symptoms. Most recent studies were likely to have used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual fourth edition (DSM‐IV) or the International Classification of Diseases tenth edition (ICD‐10) criteria. Older studies may have used ICD‐9, DSM‐III / DSM‐IIIR or other diagnostic systems. Studies of acute treatment with risperidone, which recruited patients with diagnoses other than bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder and did not stratify randomisation according to diagnosis were not included in this review.

Types of interventions

Risperidone in comparison with placebo or other antimanic treatment either as monotherapy or adjunctive treatment in the treatment of an acute manic or mixed episode.

Types of outcome measures

1. Efficacy in the treatment of manic or mixed episode.

The primary measure of efficacy for this review was change in manic symptom rating scale scores.

Secondary measures of efficacy included were:‐ (a) achievement of response or remission of manic symptoms. It is anticipated that the response and remission will be defined as a minimum percentage reduction and minimum absolute score respectively on a mania rating scale, but any other measures reported will be considered; (b) change in depression rating scales and achievement of response or remission of depressive symptoms for patients experiencing a mixed episode; (c) change in psychotic symptom rating scales; (d) change in rating scales of severity of psychiatric symptoms; (e) use of rescue medication; (f) time to onset of symptom reduction or response; (g) requirement for inpatient care e.g. length of stay. 2. General health and social functioning, measured by quality of life scales. 3. Acceptability of treatment. Completion of trial treatment, which includes elements of tolerability and efficacy, was used as an indicator of the overall acceptability of treatments.

4. Specific adverse effects, measured by patients experiencing or requiring medication for the treatment of these adverse effects and by requirement for medication for treatment emergent adverse effects:‐ (a) movement disorders ‐ parkinsonian symptoms, dystonia, akathisia, tardive dyskinesia; (b) cardiovascular effects ‐ hypotension, tachycardia, arrhythmias and ECG changes; (c) switch to depression for patients experiencing a manic episode; (d) weight gain; (e) sedation; (f) gastrointestinal disturbance ‐ nausea, vomiting, constipation; (g) haematological changes; (h) diabetes; (i) alopecia; (j) worsening of mania; (k) other adverse effects.

5. Mortality rates during treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches:

The CCDANCTR‐Studies register was searched with the following search strategy in December 2004:

Diagnosis = ("Bipolar III Disorder" or "Unipolar Mania" or "Rapid Cycling Disorder" or "Affective Disorders" or "Affective Psychosis, Bipolar" or "Bipolar Disorder " or "Bipolar I Disorder" or "Bipolar II Disorder" or "Cyclothymic Disorder " or "Depression " or "Depressive Psychosis" or "Excited Psychosis" or "Hypomania" or "Mania" or "Manic‐Depressive" or "Manic Disorder" or "Manic Episode" or "Melancholia" or "Mixed Depression" or "Mood Disorders" or "Bipolar Affective Disorder " or "Bipolar Not Otherwise Specified " or "Dysphoric Mania" or "Manic Episode" or "Manic Symptoms" or "Schizoaffective Disorder" or "Psychoses" or "Psychotic Disorders" or "Puerpal Psychosis " or "Reactive Depressive Psychosis") and Intervention = Risperidone

To supplement the above search, the following specified electronic databases were searched with the subject headings "risperidone", "affective disorders, psychotic", "bipolar disorder", and "mania"; and the text words "risperidone", "mania*", and "manic". The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) EMBASE (1980‐2004) MEDLINE (1966‐2004) CINAHL (1982‐2004) PsycINFO (1872‐2004)

Reference Checking. The reference lists of all identified randomised controlled trials, other relevant papers and major textbooks of affective disorder written in English were checked.

Personal Communication: The authors of significant papers were identified from authorship lists over the last five years. They, and other experts in the field, were contacted and asked of their knowledge of other studies, published or unpublished, relevant to the review article.

Janssen Cilag Ltd. were asked to supply missing data.

Data collection and analysis

1. Selection of trials and data extraction Studies relating to risperidone generated by the search strategies were checked to ensure they met the previously defined inclusion criteria. Two reviewers independently extracted data concerning participant characteristics, intervention details and outcome measures from the included studies. Subgroup analyses were recorded where the subgroups were defined a priori; if appropriate, the results were included in the meta‐analysis. All disagreements were resolved by discussion.

2. Quality assessment Quality was assessed according to the Cochrane criteria for quality assessment (Sackett 1997). This pays particular attention to the adequacy of the randomisation procedure. On this basis, studies were given a quality rating of A (adequate), B (unclear), and C (inadequate). When the raters disagreed the final rating was made by consensus with the involvement (when necessary) of another member of the review group. In addition, a general appraisal of study quality was made by assessing key methodological issues such as blinding, completeness of follow‐up and reporting of study withdrawals. Where inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials were provided, the authors were contacted in order to obtain further information. There was no non‐concurrence over selection of papers or quality assessment.

3. Data Analysis Data were entered into Revman 4.2 software by one reviewer. Intention to treat (ITT) data were used when available. Where ITT data were not available, end‐point data for trial completers were used.

(a) Continuous data were analysed using weighted mean differences (with 95% confidence intervals (CI)) or standardised mean differences (where different measurement scales were used). Where standard deviations were not recorded, authors were asked to supply the data. In the absence of data from the authors the mean standard deviation from other studies was used. When there were missing data and the method of "last observation carried forward " (LOCF) was used to do an ITT analysis, then the LOCF data were used, with due consideration of the potential bias and uncertainty introduced. When withdrawal from the trial is random and not associated with the trial intervention, the LOCF approach is usually assumed to give a conservative estimate of the effectiveness of a treatment in an acute illness. When withdrawal is non‐random (i.e. associated with one of the treatments) it can give a biased estimate of that treatment effect. (b) For dichotomous, or event‐like, data, relative risks (RR) were calculated with 95% CI. Where data was not reported for participants who withdrew from a trial before the endpoint, it was assumed they would have experienced the negative outcome by the end of the trial (e.g. failure to respond to treatment). Where data was imputed by the reviewers for a substantial proportion of participants (more than 20%), sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate the effect of the possible different outcomes of those participants who withdrew in each group (for example, all the patients in the experimental group experience the negative outcome and all those allocated to the comparison group experience the positive outcome).

(c) Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the chi‐squared test with a P‐value of less than or equal to 0.1 being taken to indicate heterogeneity. The I‐squared (I2) statistic was also noted and a value for I2 of greater that 50% was taken to indicate substantial heterogeneity. Where heterogeneity was identified, potential sources were considered in terms of the clinical characteristics (participants, interventions and outcomes) and methodological characteristics of the studies. Fixed and random effects analyses were done routinely to investigate the effect of the choice of method on the estimates and material differences between the models. Where heterogeneity was identified, random effects analyses has been reported in the text. (d) Skewed data and non‐quantitative data were presented descriptively .

(e) Monotherapy and adjunctive treatment trials were analysed separately and, where appropriate, combined results were also reported.

Where data were reported, subgroup analyses were performed to assess the possibility of differences in the efficacy of risperidone in the treatment of psychotic and non‐psychotic mania. If data were available, analysis by length of treatment was performed to ascertain whether any treatment differences detected varied with time.

(f) Estimation of standard deviation Where dispersion for continuous measures was reported as standard error of the mean, it was decided to include this data by converting standard errors to approximate standard deviations. These were calculated by multiplying the standard error by the square root of the number of participants whose data were included in the calculation of the means.

Results

Description of studies

The search for randomised controlled trials of risperidone identified 610 papers from which five randomised controlled trials of risperidone in mania were identified (RIS‐USA‐102 2002; RIS‐INT‐46 2002; RIS‐INT‐69 2004; Segal 1998, Smulevich 2005). A conference poster was obtained for a further trial both comparing risperidone with placebo (RIS‐IND‐6 2002). The six trials reported nine comparisons with risperidone (1343 randomised participants):

risperidone monotherapy versus placebo (RIS‐IND‐6 2002; RIS‐INT‐69 2004, Smulevich 2005)

risperidone in combination with lithium, valproate or carbamazepine versus placebo in combination with lithium, valproate or carbamazepine (RIS‐USA‐102 2002; RIS‐INT‐46 2002)

risperidone monotherapy versus haloperidol monotherapy (Segal 1998, Smulevich 2005)

risperidone in combination with lithium or valproate versus haloperidol in combination with lithium or valproate (RIS‐USA‐102 2002)

risperidone monotherapy versus lithium monotherapy (Segal 1998)

(Several of the trials were presented at a number of conferences and subgroup analyses have been published. In this review only publications from which data have been included have been referenced).

Permitted doses were appropriate for mania (SmPC Haldol, SmPC Risperdal) and trials involving haloperidol allowed antiparkinsonian treatment.

Numbers of participants The number of randomised participants was 45 (Segal 1998), 151 ( RIS‐INT‐46 2002), 156 (RIS‐USA‐102 2002), 262 (RIS‐INT‐69 2004), 291 (RIS‐IND‐6 2002) and 438 (Smulevich 2005). Selection of participants Four trials were multi‐centre trials recruiting patients from the USA (RIS‐INT‐69 2004; RIS‐USA‐102 2002), from Canada, Israel, Norway, South Africa, Spain and the UK (RIS‐INT‐46 2002), and from Europe and Asia (Smulevich 2005). The number of recruitment centres was not reported for the other two trials, Segal 1998, which was conducted in South Africa, and RIS‐IND‐6 2002, which was conducted in India. No data were reported on the degree of variation between centres and therefore only the aggregate data could be included.

Washout Period Four trials (RIS‐INT‐46 2002; RIS‐USA‐102 2002; RIS‐INT‐69 2004; Smulevich 2005) reported that the screening procedures included a three day washout period during which use of psychotropic medicines was restricted. Three of these trials reported the number of patients entering the screening phase and the number entering the randomised phase. For RIS‐INT‐69 2004 337 patients were screened of whom 262 were randomised, for RIS‐USA‐102 2002 180 were screened and 158 randomised and for RIS‐INT‐46 2002 the numbers were 157 and 151 respectively.

Diagnosis of Mania For all trials, diagnosis was according to DSM‐IV criteria for bipolar disorder with manic episode (RIS‐INT‐69 2004; Segal 1998; Smulevich 2005) or with manic or mixed episode (RIS‐USA‐102 2002; RIS‐INT‐46 2002; RIS‐IND‐6 2002). In all but one trial, (Segal 1998), the inclusion criteria included a minimum score of 20 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS).

Duration of Trial. One trial (Segal 1998) reported efficacy and safety data for four weeks acute treatment, the remaining trials reported results for three weeks acute treatment. In one trial (Smulevich 2005), after three weeks participants could discontinue trial treatment or could continue double blind treatment or change to open‐label risperidone for a further nine weeks. Data from this phase has not been reported.

Risk of bias in included studies

1. Randomisation / concealment of allocation All trials were described as randomised. Two trials (RIS‐INT‐46 2002; RIS‐INT‐69 2004) used a telephone randomisation system and allocation concealment for these trials has been rated as "A" (adequate), according to Cochrane criteria (Sackett 1997). No details of the methods used to achieve random allocation or allocation concealment were given for the other trials. They have therefore been rated as "B" (unclear) for allocation concealment. Additional information has been requested from Janssen Cilag Ltd. Two trials (RIS‐INT‐69 2004; Smulevich 2005) reported stratification by treatment site and the presence or absence of psychotic symptoms at baseline.

2. Intention to treat analysis Four trials reported the exclusion from efficacy analyses of data from randomised patients who did not receive randomised treatment and/or for whom no post‐baseline data were available. The numbers excluded from analyses were three (RIS‐INT‐69 2004), two (RIS‐USA‐102 2002), one (RIS‐INT‐46 2002) and one (RIS‐IND‐6 2002).

In RIS‐INT‐69 2004 a further nine patients (five on risperidone and four on placebo) were excluded from the efficacy analyses because of non‐compliance with the study protocol at one site.

Some trials reported both observed case and LOCF data. For these trials, endpoint data when available has been reported in the text with observed case data included only in Forest plots. Four trials (RIS‐INT‐46 2002; RIS‐USA‐102 2002; Segal 1998; Smulevich 2005) reported a modified ITT analysis using the LOCF to deal with missing continuous data. One trial (RIS‐IND‐6 2002) gave no details of the way missing data were handled.

For many analyses missing data have been imputed by the authors of the papers using LOCF but the number of imputed values has not been given. It was not possible therefore to perform sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the results by making different assumptions about the missing data (see "methods of the review" section). The extent to which LOCF can be assumed to give a reliable result will depend in part on the proportion of imputed values.

3. Blinding All trials were reported to have been double‐blind, in which the treatment allocation was masked from both the clinicians and participants.

4. Withdrawal from treatment The rates of withdrawal from treatment were 12% (Smulevich 2005), 13% (Segal 1998), 20% (RIS‐IND‐6 2002), 44% (RIS‐INT‐46 2002), 45% (RIS‐USA‐102 2002) and 62% (RIS‐INT‐69 2004). In two trials, (RIS‐USA‐102 2002; RIS‐INT‐46 2002) some participants were transferred to a 10‐week, open label extension study after completing at least seven days of double blind treatment. In one of these (RIS‐INT‐46 2002) 26% of participants transferred before completion of the three week double‐blind phase so endpoint data for over a quarter of the randomised participants was LOCF.

5. Reporting of treatment emergent adverse effects Dichotomous data for treatment emergent adverse effects that occurred in at least 10% of participants in any of the treatment groups were reported for three trials (RIS‐USA‐102 2002; RIS‐INT‐69 2004; Smulevich 2005) and those that occurred in at least 5% of participants for one trial (RIS‐IND‐6 2002). It was unclear how the reported adverse events were selected in the fourth trial (RIS‐INT‐46 2002). No adverse effects were reported for the fifth trial (Segal 1998). For all trials it was unclear how these adverse effects were measured both in terms of severity and duration and further information on these is being sought from the authors.

Effects of interventions

The rates of withdrawal from treatment were high for most interventions (see section on "methodological quality of included studies") and this affects the level of confidence that can be placed in the results.

Fixed effects analyses are reported in the text unless heterogeneity was observed, in which case random effects models have been used.

Two trials (RIS‐INT‐46 2002; RIS‐INT‐69 2004) reported standard errors for continuous measures. These have been converted to approximate standard deviations.

RISPERIDONE VERSUS PLACEBO

1. Efficacy

(a) Response or remission of manic symptoms For all trials the a priori primary measure of efficacy was change from baseline to endpoint score on the YMRS.

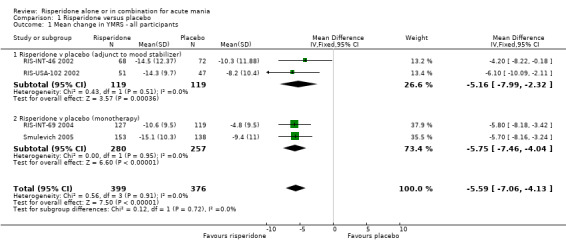

(i) Risperidone monotherapy Two trials (RIS‐INT‐69 2004; Smulevich 2005) reported data for mean change in YMRS. On this measure risperidone was more effective than placebo (WMD ‐5.75, 95% CI ‐7.46 to ‐4.04, P < 0.00001; chi‐squared = 0.00, df = 1, P < 0.00001; 2 trials, 537 participants). The third trial (RIS‐IND‐6 2002) did not provide data but included a graph showing a significant difference (p < 0.001) of approximately 11 points.

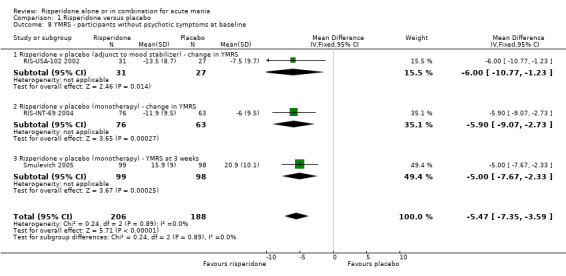

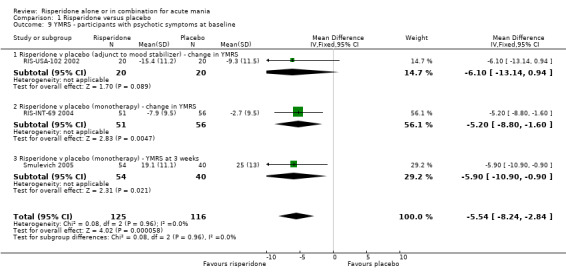

From a subgroup analysis (RIS‐INT‐69 2004) there was no evidence that the effect size varied according to the presence or absence of psychotic symptoms at baseline (see figures 01.08 and 01.09).

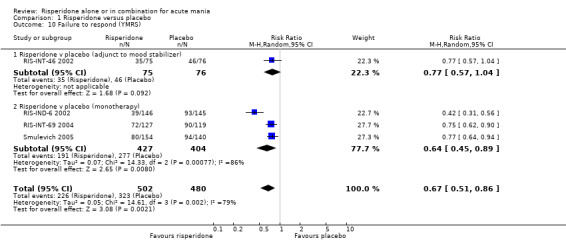

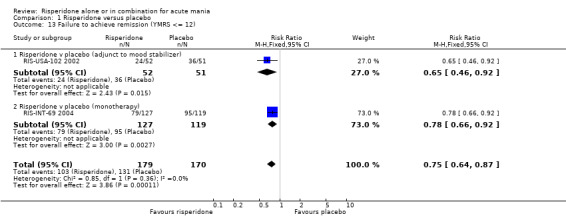

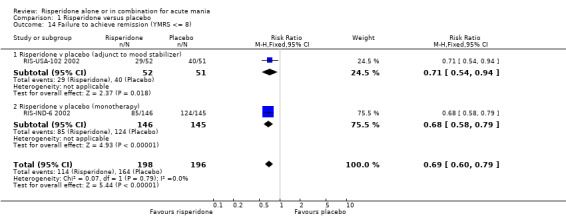

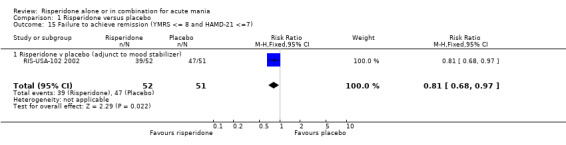

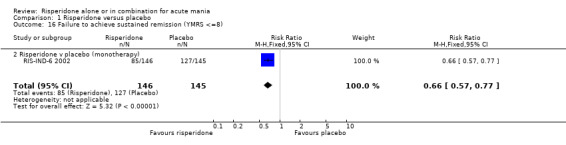

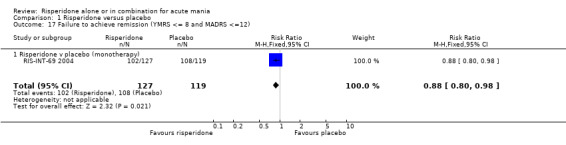

When response was defined as a 50% or greater reduction in YMRS between baseline and endpoint, the proportion of participants treated with risperidone monotherapy that failed to respond was less than in the placebo group (random effects RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.89, P = 0.008; chi‐squared = 14.33, df = 1, P = 0.0008, 3 trials, 831 participants). There was substantial heterogeneity between trials I2 = 86% with the superiority of risperidone over placebo being much greater in RIS‐IND‐6 2002 than in the other two trials (RIS‐INT‐69 2004; Smulevich 2005) (see figure 01.10). A smaller proportion of participants on risperidone monotherapy than placebo failed to meet criteria for remission, both defined as YMRS ≤ 12 (RIS‐INT‐69 2004) (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.92, P = 0.003; 1 trial, 246 participants) and as YMRS ≤ 8 (RIS‐IND‐6 2002) (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.79, P < 0.00001; 1 trial, 291 participants). Risperidone was also superior to placebo when the criteria for remission involved a measure of depressive symptoms: YMRS ≤ 8 and Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) ≤ 12 (RIS‐INT‐69 2004) (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.98, P = 0.02; 1 trial, 246 participants) and participants were more likely to sustain remission to the end of the trial (YMRS ≤ 8) (RIS‐IND‐6 2002) (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.77, P < 0.00001; 1 trial, 291 participants).

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant Risperidone was more effective than placebo as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant measured as mean change on the YMRS (WMD ‐5.16, 95% CI ‐7.99 to ‐2.32, P = 0.0004; chi‐squared = 0.43, df = 1, P = 0.51; 2 trials, 238 participants).

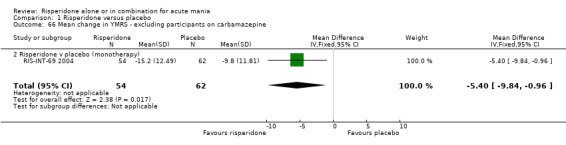

In RIS‐INT‐46 2002 it was noted that the plasma concentrations for the active moiety of risperidone were approximately 40% lower in participants on concomitant carbamazepine than for those on lithium or divalproex. A post‐hoc analysis which excluded participants on carbamazepine found the superiority of risperidone over placebo to be greater when used as adjunctive treatment to lithium or divalproex rather than carbamazepine. (See figure 01.01 for main analysis and 01.66 for pot‐hoc analysis).

When response was defined as 50% or greater reduction in YMRS between baseline and endpoint (RIS‐INT‐46 2002), there was some evidence that risperidone was associated with a lower rate of failure to respond than placebo but the difference was not significant (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.04, P = 0.09; 1 trial, 151 participants).

One trial (RIS‐USA‐102 2002) used three different definitions of remission. For all three definitions risperidone was superior to placebo as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant in the proportion of patients who failed to achieve remission, YMRS ≤ 12 (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.92, P = 0.02; 1 trial, 103 participants), YMRS ≤ 8 (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.94, P = 0.02; 1 trial, 103 participants) and, when depressive symptoms were included, YMRS ≤ 8 and 21‐item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD‐21) ≤ 7 (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.97, P = 0.02; 1 trial, 103 participants).

From a subgroup analysis there was no evidence that the greater reduction in manic symptoms for risperidone compared to placebo varied according to the presence or absence of psychotic symptoms at baseline (see figures 01.08 and 01.09).

(iii) Combined results for monotherapy and adjunctive therapy Risperidone (alone or in combination with lithium or an anticonvulsant) was shown to be more effective than placebo in reducing manic symptoms measured on the YMRS (WMD ‐5.59, 95% CI ‐7.06 to ‐4.13, P < 0.00001; chi‐squared = 0.56, df = 2, P = 0.91; 4 trials, 775 participants).

Risperidone (alone or in combination with lithium or an anticonvulsant) was found to be associated with a lower rate of failure to respond measured as 50% or greater reduction in YMRS (random effects RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.86, P = 0.002; chi‐squared 14.61, df = 3, P = 0.002; 4 trials, 982 participants) and failure to achieve remission according to the definition YMRS ≤ 8 (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.79, P < 0.00001; chi‐squared 0.07, df = 2, P = 0.79; 2 trials 394 participants) and YMRS ≤ 12 (P = 0.0001; see figure 1.10, 1.13 and 1.14).

(b) Change in depressive symptoms

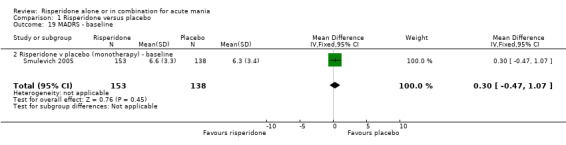

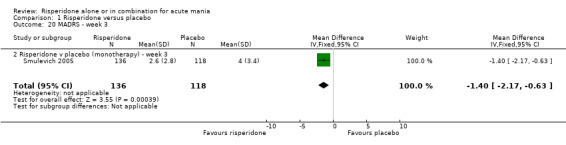

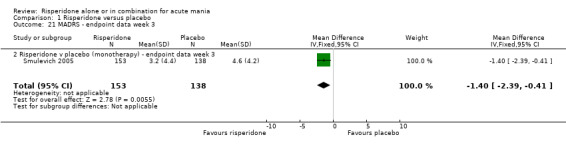

(i) Risperidone monotherapy There was no difference between the groups on baseline MADRS (see figure 01.19) and the mean scores were below the threshold for mild depression. Participants in the risperidone group had lower MADRS scores at endpoint than those in the placebo group (Smulevich 2005) (WMD ‐1.40, 95% CI ‐2.39 to ‐0.41, P = 0.006; 1 trial, 291 participants).

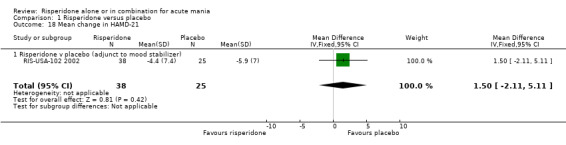

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant Data reported for participants who completed the three week treatment period (63/103) did not show any evidence of a significant difference between risperidone and placebo as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anti‐convulsants in reduction of HAMD‐21 score (RIS‐USA‐102 2002) (WMD 1.50, 95% CI ‐2.11 to 5.11, P = 0.42; 1 trial, 63 participants). At baseline the mean score for the total sample was 15.33 which corresponds to mild depression but baseline data for the participants for whom change data was available was not reported.

(c) Change in psychotic symptom rating scales No data were reported

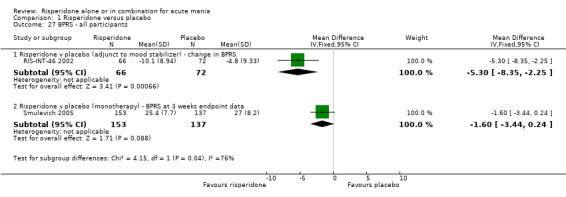

(d) Change in severity of psychiatric symptoms rating scales (i) Risperidone monotherapy No significant difference was found between risperidone and placebo in the Brief Psychiatric Symptom Scale (BPRS) score endpoint (Smulevich 2005) (WMD ‐1.60, 95% CI ‐3.44 to 0.24, P = 0.09; 1 trial, 190 participants).

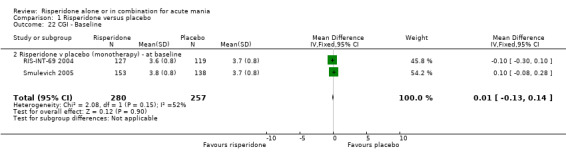

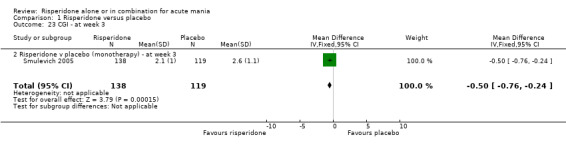

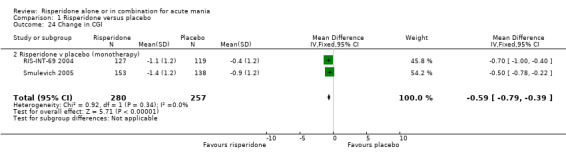

The reduction in Clinical Global Impression (CGI) ‐ severity score at endpoint was greater for participants in the risperidone group than for those in the placebo group (RIS‐INT‐69 2004; Smulevich 2005) (RR ‐0.59, 95% CI ‐0.79 to ‐0.39, P < 0.00001; chi‐squared 0.92, df = 1, P = 0.34, 2 trials, 537 participants).

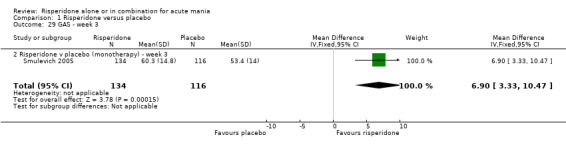

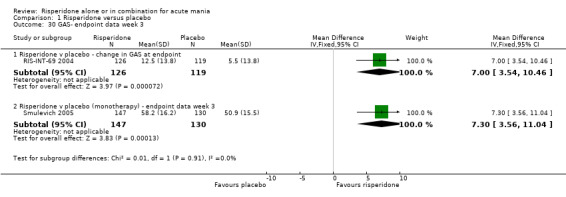

Risperidone was associated with greater improvement than placebo on the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) both when reported as change at endpoint (RIS‐INT‐69 2004) (WMD 7.00, 95% CI 3.54 to 10.46, P < 0.0001; 1 trial, 254 participants) and as endpoint score (WMD 7.30, 95% CI 3.56 to 11.04, P < 0.0001; 1 trial, 277 participants) (Smulevich 2005). (ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant was superior to placebo in reduction of psychiatric symptoms measured on the BPRS (WMD ‐5.30, 95% CI ‐8.35 to ‐2.25, P = 0.0007; 1 trial, 138 participants).

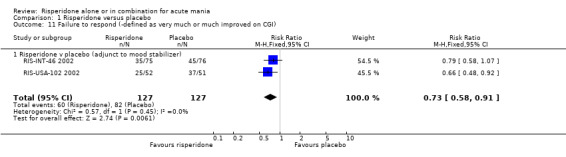

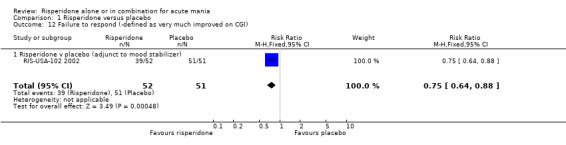

For both trials risperidone was found to be superior to placebo when response was defined as "very much improved" or "much improved" on the CGI scale (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.91, P = 0.006; chi‐squared 0.57, df = 1, P = 0.45; 2 trials, 254 participants) and also for (RIS‐USA‐102 2002) when response was defined as "very much improved" (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.88, P = 0.0003; 1 trial, 103 participants).

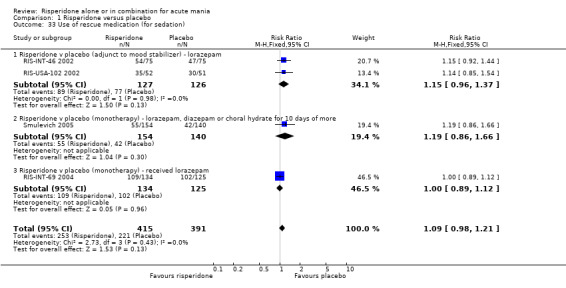

(e) Use of rescue medication

(i) Risperidone monotherapy No difference was found between the proportion of participants on risperidone and on placebo that received any lorazepam (RIS‐INT‐69 2004) (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.12, P = 0.96; 1 trial, 159 participants) or required lorazepam, diazepam or chloral hydrate for more than 10 or more days (Smulevich 2005) (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.66, P = 0.30; 1 trial, 294 participants).

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was no difference between risperidone and placebo as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant in the number of participants who were given lorazepam (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.37, P = 0.13; chi‐squared = 0.00, df = 1, P = 0.98; 2 trials, 253 participants).

(f) Time to onset of symptom reduction or response

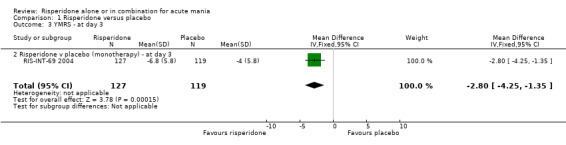

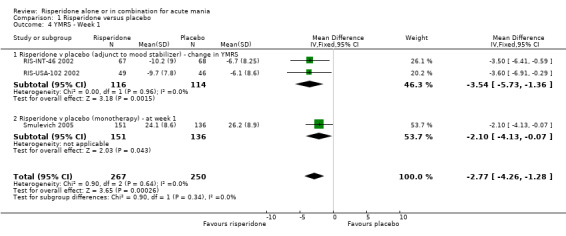

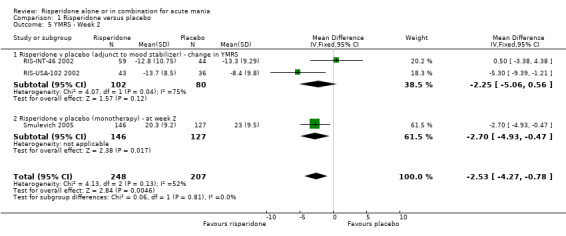

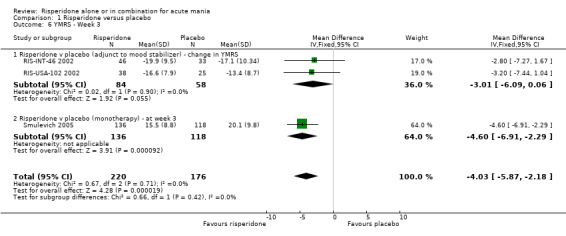

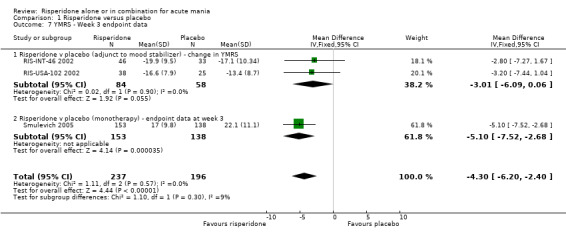

(i) Risperidone as monotherapy and as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was some evidence from all five trials that the superiority of risperidone over placebo in reducing manic symptoms measured on the YMRS emerged as early as day three of treatment and was maintained over the three week period (See figures 1.03 to 1.07). (g) Requirement for inpatient care e.g. length of stay No data were reported.

2. General Health and Social Functioning No data were reported.

3. Acceptability of Treatments

(a) Completion of trial treatment was used as an indicator of overall treatment acceptability

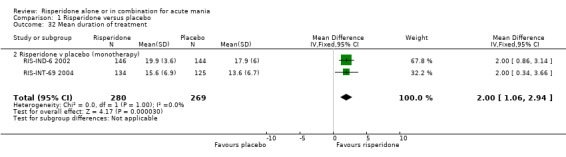

(i) Risperidone monotherapy There was significant quantitative heterogeneity between the difference in the proportion of patients who failed to complete treatment (I2 = 68.1%). There was also difference between trials in the absolute proportions with only 11% of participants on risperidone failing to complete treatment for RIS‐IND‐6 2002 and Smulevich 2005 compared to 44% for RIS‐INT‐69 2004. Overall a smaller proportion of participants treated with risperidone than placebo failed to complete treatment (random effects RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.95, P = 0.03; chi‐squared 6.28, df = 2, P = 0.04; 3 trials, 844 participants). The mean duration of adherence to trial treatment was two days longer for participants on risperidone monotherapy than for patients on placebo (RIS‐IND‐6 2002; RIS‐INT‐69 2004) (WMD 2.00, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.94, P < 0.0001; chi squared 0.00, df = 1, P = 1.0; 2 trials, 549 participants) (see figure 01.32).

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant A smaller proportion of participants treated with risperidone than placebo as adjunctive treatment failed to complete treatment (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.92, P = 0.01; chi‐squared 0.02, df = 1, P = 0.88; 2 trials, 253 participants).

(iii) Combined results for monotherapy and adjunctive therapy Risperidone was superior to placebo in failure to complete trial treatment when the results of the five placebo controlled trials were combined (random effects RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.82, P = 0.0003; chi‐squared 6.20, df = 4 P = 0.18; 5 trials, 1097 participants).

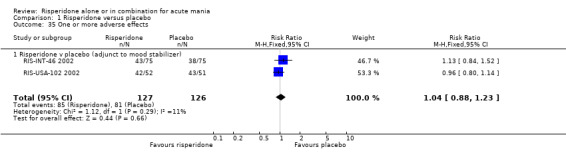

4. Adverse Effects

Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant: There was no difference between risperidone and placebo as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant in terms of the proportion of participants who experienced one or more adverse effect (fixed effects RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.23, P = 0.66; chi‐squared 1.12, df = 1, P = 0.29; 2 trials, 253 participants).

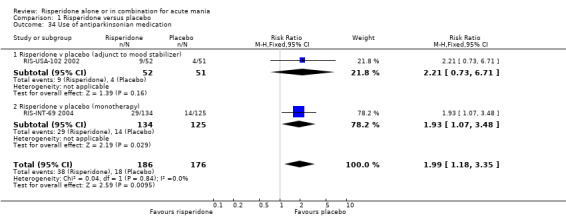

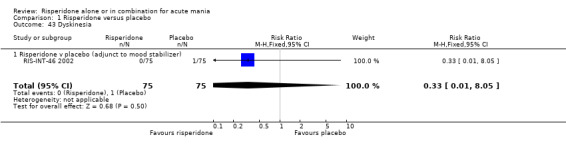

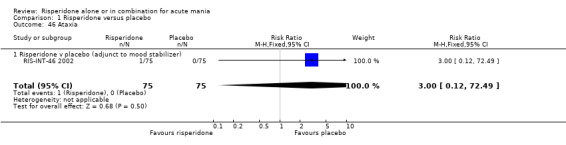

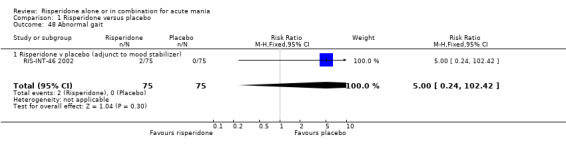

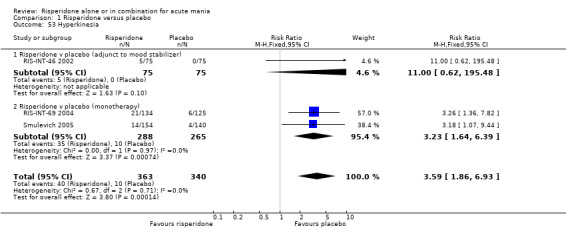

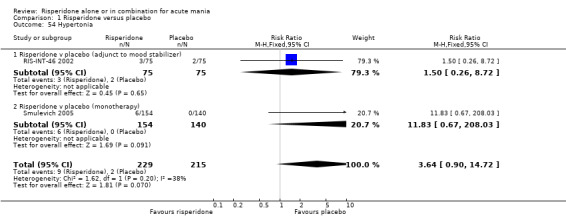

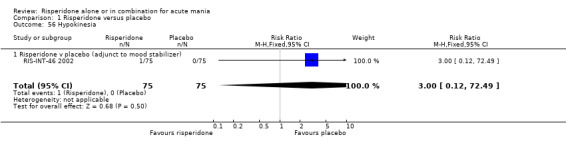

(a) Movement disorders

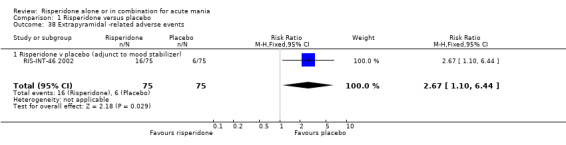

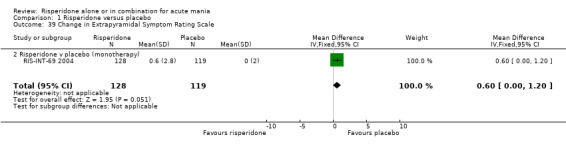

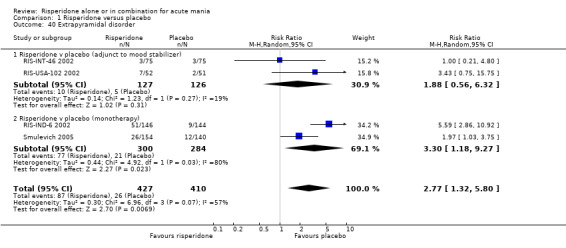

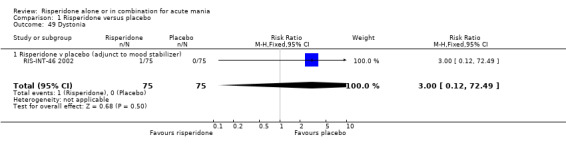

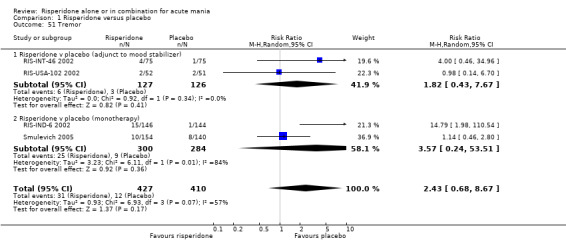

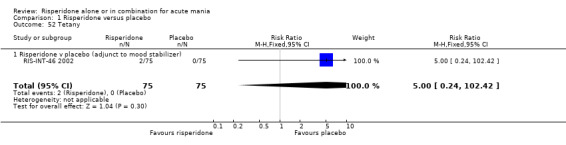

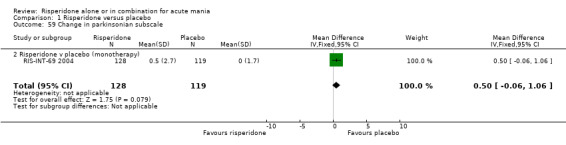

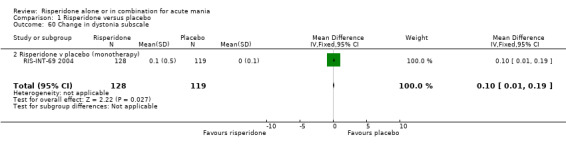

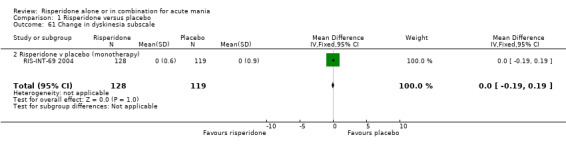

(i) Risperidone as monotherapy Risperidone caused greater increase in extrapyramidal symptoms measured on the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS) than placebo (WMD 0.60, 95% CI 0.00 to 1.20, P = 0.05; 1 trial, 247 participants). This difference was only significant for the dystonia subscale (see figures 01.59 ‐ 01.61). There was significant heterogeneity between trials in the incidence of extrapyramidal disorder (I2 = 79.7%) but both random and fixed effects analyses found a higher incidence for risperidone than for placebo (random effects RR 3.30, 95% CI 1.18 to 9.27, P = 0.02; chi‐squared 4.92, df = 1, P = 0.03; 2 trials, 584 participants) (see figure 01.40). Risperidone was associated with a higher incidence of hyperkinesia (RR 3.23, 95% CI 1.64 to 6.39, P = 0.0007; 2 trials, 553 participants) (figure 01.53). No difference was found between risperidone and placebo in the incidence of tremor using a random effects model to take into account the observed heterogeneity (I2 = 83.6%) (random effects RR 3.57, 95% CI 0.24 to 53.51, P = 0.36; 2 trials, 584 participants) (see figure 01.51), but using a fixed effects model, risperidone was associated with a higher incidence of tremor (P = 0.01). No difference was found between risperidone and placebo in incidence of hypertonia (RR 11.83, 95% CI 0.67 to 208.03, P = 0.09; 1 trials, 294 participants). A higher proportion of participants on risperidone than placebo were given anticholinergic medication (RR 1.93, 95% CI 1.07 to 3.48; P = 0.03, 1 trial, 159 participants) (see figure 01.34). (ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant Adjunctive risperidone caused more extrapyramidal related adverse events than placebo (RR 2.67, 95% CI 1.10 to 6.44, P = 0.03; 1 trial, 150 participants). This difference was not significant in the incidence of a range of specific movement disorders although for all but dyskinesia the point estimate favoured placebo ‐ extrapyramidal disorder (fixed effects RR 1.98, 95% CI 0.69 to 5.64, P = 0.20; 2 trials, 253 participants), tremor (fixed effects RR 1.98, 95% CI 0.51 to 7.74, P = 0.33, 2 trials, 253 participants), hyperkinesia (RR 11.00, 95% CI 0.62 to 195.48, P 0.10; 1 trial, 150 participants), hypertonia (RR 1.50, 95% CI 0.26 to 8.72, P = 0.65; 1 trial, 150 participants), abnormal gait (RR 5.00, 95% CI 0.24 to 102.42, P = 0.30; 1 trial, 150 participants), dystonia (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.12 to 72.49, P = 0.50; 1 trial, 150 participants), hypokinesia (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.12 to 72.49, P = 0.50; 1 trial, 150 participants), ataxia (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.12 to 72.49, P = 0.50; 1 trial, 150 participants), tetany (RR 5.00, 95% CI 0.24 to 102.42, P = 0.30; 1 trial, 150 participants) and dyskinesia (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.05, P = 0.50; 1 trial, 105 participants). There was no evidence of a difference between risperidone and placebo as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant in the proportion of participants who were given anticholinergic medication (RR 2.21, 95% CI 0.73 to 6.71, P = 0.16; 1 trial, 103 participants).

(b) Cardiovascular adverse effects

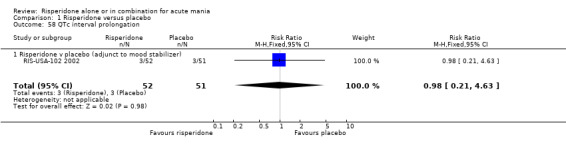

(i) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was no evidence that risperidone was associated with a higher rate of QTc interval prolongation than placebo (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.21 to 4.63; P = 0.98, 1 trial, 103 participants)

(c) Depression No data were reported.

(d) Weight gain

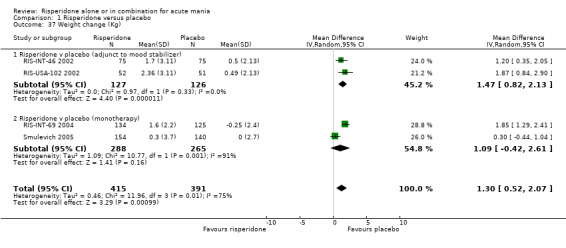

(i) Risperidone monotherapy There was substantial heterogeneity between trials (I2 = 90.7%) with the Smulevich 2005 reporting a mean weight gain of 0.30 kg on risperidone and RIS‐INT‐69 2004 reporting 1.60 kg. For placebo the figures are 0.00 (standard deviation (SD) 2.70) kg and ‐0.25 (SD 2.40) kg respectively. No difference was found between risperidone and placebo using a random effects model (random effects WMD 1.09, 95% CI ‐0.42 to 2.61, P = 0.16; chi squared 10.77, df = 1, P = 0.001; 2 trials, 553 participants) (see figure 01.37). A fixed effects analysis found risperidone to cause more weight gain than placebo (P < 0.0001).

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant (One trial (RIS‐INT‐46 2002) did not report the SDs so the value from (RIS‐USA‐102 2002) has been used for both trials)

Risperidone caused more weight gain than placebo as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant (fixed effects WMD 1.47, 95% CI 0.82 to 2.13, P < 0.0001; chi‐squared 0.97, df = 1, P = 0.33; 2 trials, 253 participants). The mean weight gains on risperidone were 1.70 kg (RIS‐INT‐46 2002) and 2.39 kg (RIS‐USA‐102 2002). For placebo the figures were 0.50 kg and 0.49 kg respectively.

(iii) Combined results for monotherapy and adjunctive therapy The combined results showed a mean weight gain for patients on risperidone of 1.2 kg which was significantly different to the 0.2 kg gain on placebo (see figure 01.37).

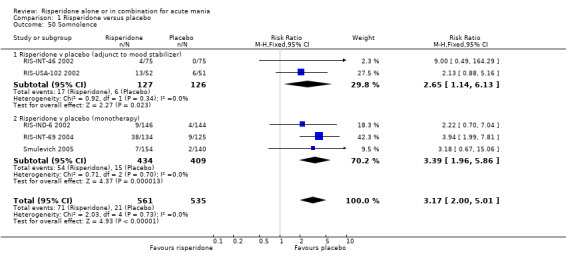

(e) Sedation (i) Risperidone monotherapy Risperidone monotherapy was associated with a higher incidence of sedation than placebo (fixed effects RR 3.39, 95% CI 1.96 to 5.86, P < 0.0001; chi‐squared 0.71, df = 2, P = 0.71; 3 trials, 843 participants). There was no heterogeneity between trials in terms the relative risk but the incidence of sedation was much greater in (RIS‐INT‐69 2004) (28% for risperidone and 7.2% for placebo) than in (RIS‐IND‐6 2002) (6.2% and 2.8% respectively) and (Smulevich 2005) (4.5% and 1.4% respectively).

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant Risperidone and placebo as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant caused more sedation than placebo (fixed effects RR 2.65, 95% CI 1.14 to 6.13, P = 0.02; chi‐squared 0.92, df = 1, P = 0.34; 2 trials, 253 participants).

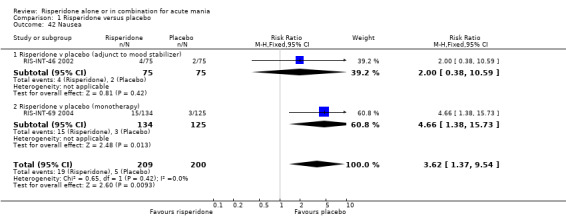

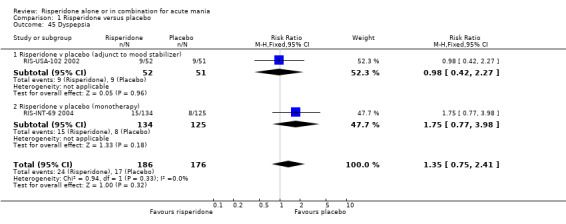

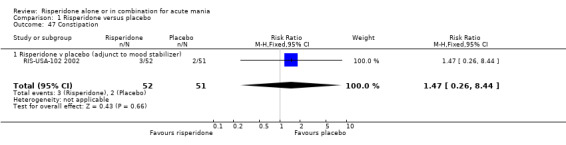

(f) Gastrointestinal disturbance

(i) Risperidone monotherapy Risperidone monotherapy was associated with a higher incidence of nausea than placebo (RR 4.66, 95% CI 1.38 to 15.73, P = 0.01; 1 trial, 259 participants) but there was no difference in the incidence of dyspepsia (RR 1.75, 95% CI 0.77 to 3.98, P =0.18; 1 trial, 259 participants).

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anti‐convulsant There was no difference between risperidone and placebo as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant in nausea (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.38 to 10.59, P = 0.42; 1 trial, 150 participants), constipation (RR 1.47, 95% CI 0.26 to 8.44; P = 0.66, 1 trial, 103 participants) or dyspepsia (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.42 to 2.27; P = 0.96, 1 trial, 103 participants).

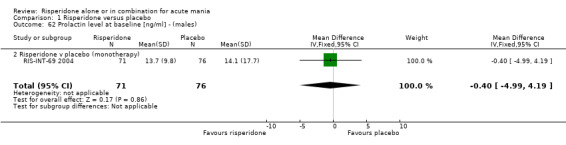

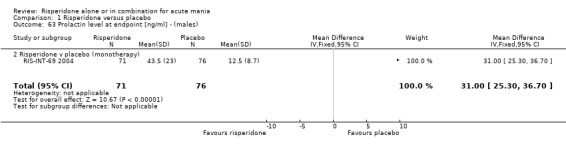

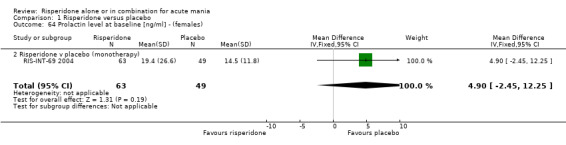

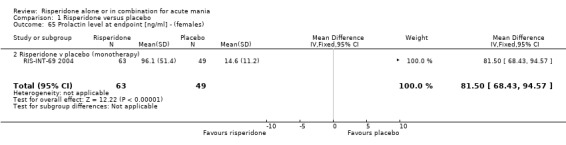

(g) Haematological changes Risperidone was associated with significantly higher endpoint prolactin levels than placebo at endpoint (RIS‐INT‐69 2004) than placebo both for males (WMD 31.00, 95% CI 25.30 to 36.70) and females (WMD 81.50, 95% CI 68.43 to 94.57). The mean endpoint levels for patients allocated risperidone were 43.50 (SD 23.00) ng/ml for males and 96.10 (SD 51.40) ng/ml for females.

(h) Diabetes No data were reported.

(i) Alopecia No data were reported.

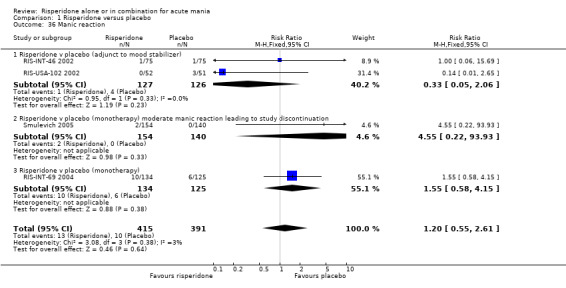

(j) Worsening of mania

(i) Risperidone monotherapy No difference was found between risperidone and placebo in terms of the incidence of a manic reaction (RIS‐INT‐69 2004) (RR 1.55, 95% CI 0.58 to 4.15, P = 0.38, 1 trial, 259 participants) or in terms of the number of participants withdrawing from treatment due to a manic reaction (Smulevich 2005) (RR 4.55, 95% CI 0.22 to 93.93, P = 0.33, 1 trial, 294 participants).

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was no difference between risperidone and placebo as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant in the proportion of participants for whom worsening of mania or manic reaction was reported (fixed effects RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.05 to 2.06, P = 0.23; chi‐squared 0.95, df = 1 P = 0.33; 2 trials, 253 participants).

(iii) Combined results for monotherapy and adjunctive therapy The overall incidence of manic reactions reported was 13/415 for risperidone and 10/391 for placebo. (k) Other adverse effects

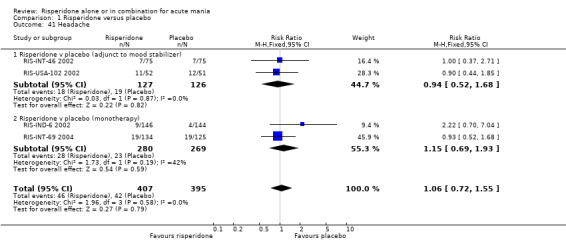

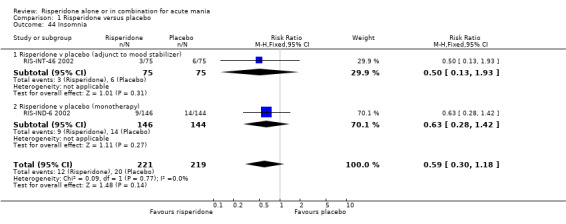

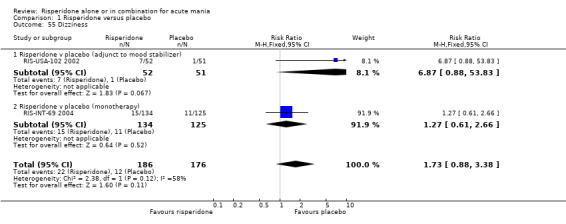

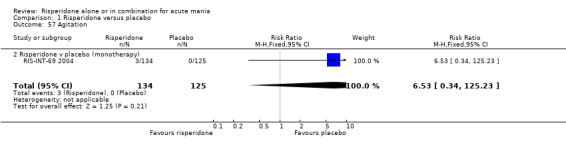

(i) Risperidone monotherapy There was no evidence of a difference between risperidone monotherapy and placebo for four adverse effects: agitation (RR 6.53, 95% CI 0.34 to 125.23, P = 0.21; 1 trial 259 participants); headache (fixed effects RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.93, P = 0.59; chi‐squared 1.73, df = 1, P = 0.19; 2 trials, 549 participants); dizziness (RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.66, P = 0.52; 1 trial, 259 participants) and insomnia (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.42, P = 0.27; 1 trial, 290 participants). (ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was no difference between risperidone and placebo as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anti‐convulsant in three adverse effects: headache (fixed effects RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.68, P = 0.82; chi‐squared 0.03, df = 1, P = 0.87; 2 trials, 253 participants); dizziness (RR 6.87, 95% CI 0.88 to 53.83, P = 0.07; 1 trial, 103 participants) and insomnia (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.13 to 1.93; P = 0.31, 1 trial, 150 participants).

5. Mortality None of the trials reported any deaths during the treatment periods.

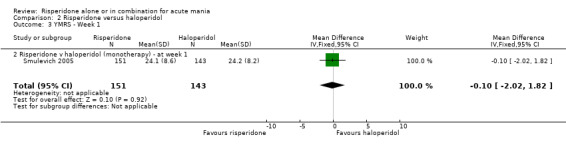

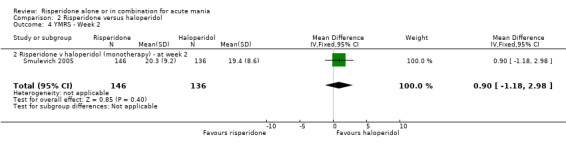

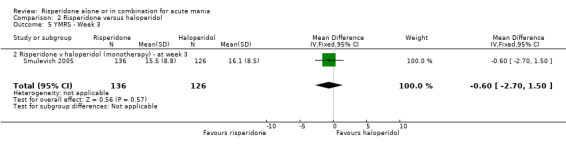

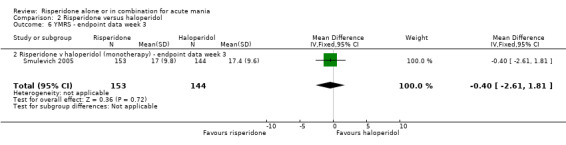

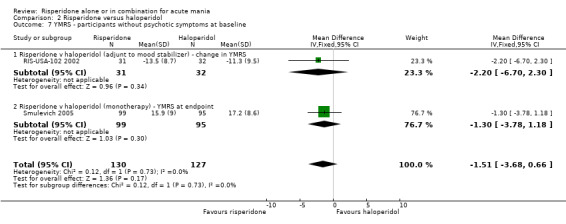

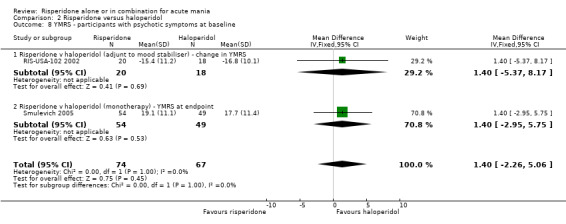

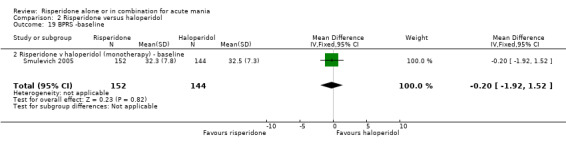

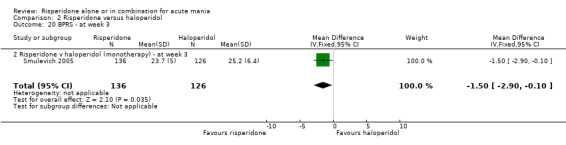

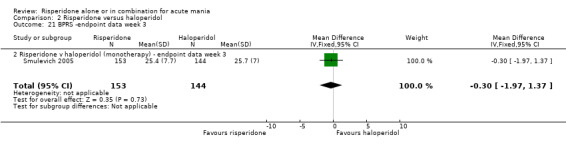

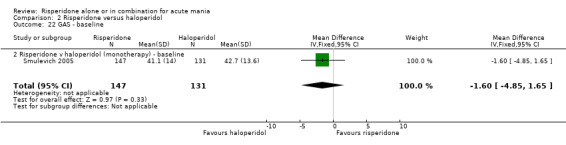

RISPERIDONE VERSUS HALOPERIDOL 1. Efficacy

(a) Response or remission of manic symptoms

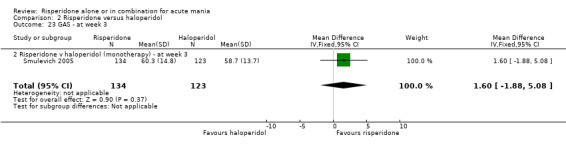

(i) Risperidone monotherapy Endpoint data Mania Rating Scale (MRS) for Segal 1998 could not be used because SDs were not reported.

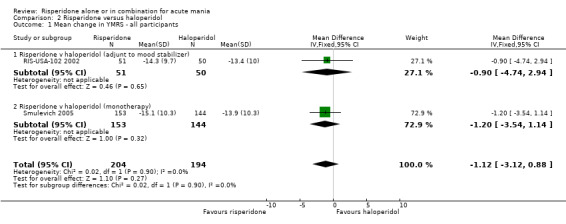

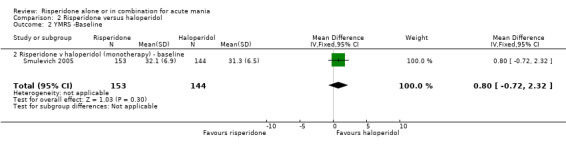

There was no evidence for a significant difference between risperidone and haloperidol in mean change on YMRS (WMD ‐1.20, 95% CI ‐3.54 to 1.14, P = 0.32; 1 trial, 297 participants) or in mean endpoint YMRS (see figure 02.06). There was no evidence from subgroup analyses for a significant difference in efficacy between risperidone and haloperidol for participants with psychotic symptoms at baseline or for participants without psychotic symptoms at baseline (see figures 02.07 and 02.08).

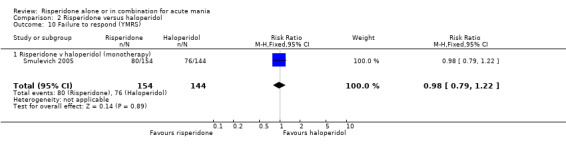

No difference was found between risperidone and haloperidol in the proportion of participants who failed to respond (Smulevich 2005) (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.22, P = 0.89; 1 trial, 298 participants).

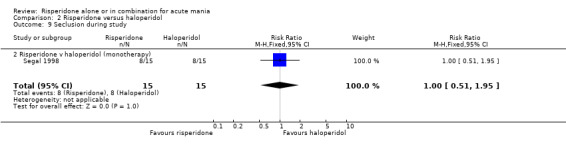

There was no evidence for a significant difference between risperidone monotherapy and haloperidol in terms of the proportion of participants who were secluded for a period of time during the treatment period (Segal 1998) (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.95 trial, P = 1.00; 1 trial, 30 participants).

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was no evidence for a significant difference between risperidone and haloperidol in change on YMRS (RIS‐USA‐102 2002) for all participants (WMD ‐0.90, 95% CI ‐4.74 to 2.94, P = 0.65; 1 trial, 101 participants), for the subgroup of participants who had psychotic symptoms at baseline or for those without psychotic symptoms at baseline (see figures 02.07 and 02.08).

(iii) Risperidone as monotherapy and as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant No difference was found between risperidone and haloperidol as monotherapy or adjunctive treatment when the results of the trials (Smulevich 2005; and RIS‐USA‐102 2002) were combined (WMD ‐1.12, 95% CI ‐3.12 to 0.88, P = 0.27; chi‐squared 0.02, df = 1, P = 0.90; 2 trials, 398 participants).

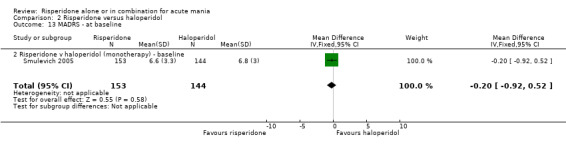

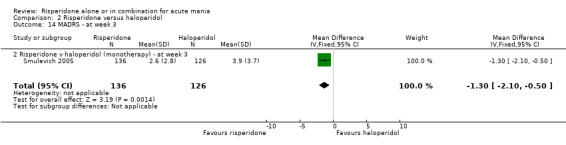

(b) Change in depressive symptoms

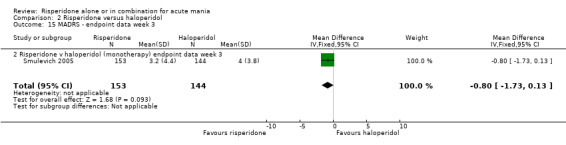

(i) Risperidone monotherapy There was no difference between the groups on baseline MADRS (see figure 02.13) and the mean scores were below the threshold for mild depression. There was no difference between risperidone and haloperidol in MADRS scores at endpoint (Smulevich 2005) (WMD ‐0.80, 95% CI ‐1.73 to 0.13, P = 0.09; 1 trial, 297 participants).

(c) Change in psychotic symptom rating scales No data were reported

(d) Change in severity of psychiatric symptoms rating scales

(i) Risperidone monotherapy

No difference was found between risperidone and haloperidol in BPRS endpoint score (Smulevich 2005) (WMD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐1.97 to 1.37, P = 0.73; 1 trial, 297 participants). (See figures 02.19 and 02.20 for baseline and week three data).

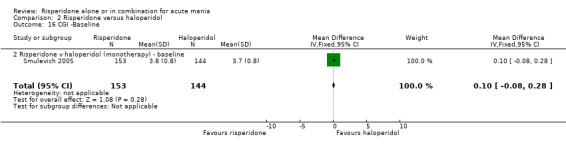

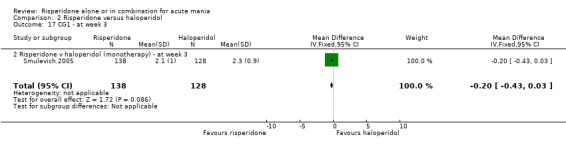

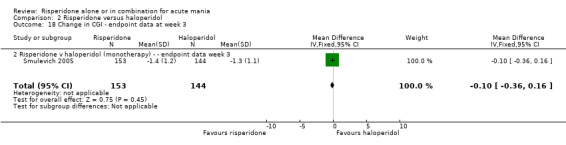

No difference was found between risperidone and haloperidol in change in the CGI severity of illness scale (Smulevich 2005) (WMD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.36 to 0.16, P = 0.45; 1 trial, 297 participants). (See figures 02.16 and 02.17 for baseline and week three data).

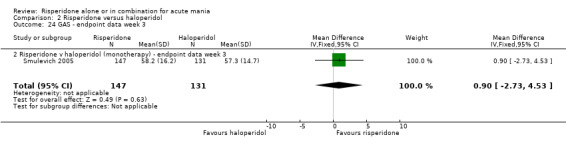

No difference was found between risperidone and haloperidol in GAS endpoint score (Smulevich 2005) (WMD 0.90, 95% CI ‐2.73 to 4.53, P = 0.63; 1 trial, 278 participants). (See figures 02.22 and 02.23 for baseline and week three data).

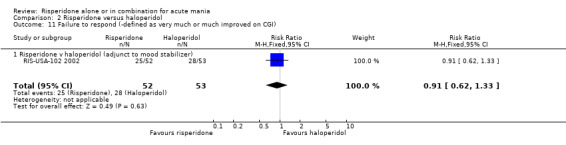

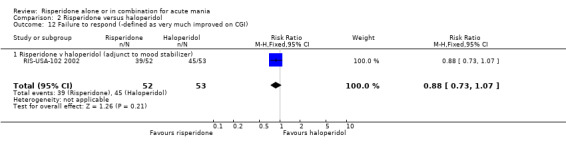

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was no evidence of a significant difference between risperidone and haloperidol when response was defined as "very much improved" on the CGI change scale (RIS‐USA‐102 2002) (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.07, P = 0.21; 1 trial, 105 participants) or when response was taken to include both "very much improved" and "much improved" (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.33, P = 0.63; 1 trial, 105 participants).

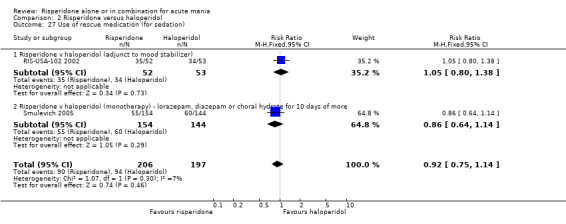

(e) Use of rescue medication (i) Risperidone monotherapy There was no evidence of a difference between risperidone and haloperidol as monotherapy in the number of participants who required lorazepam, diazepam or chloral hydrate for 10 or more days (Smulevich 2005) (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.14, P = 0.29; 1 trial, 298 participants).

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was no evidence of a difference between risperidone and haloperidol as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant in the number of participants who were given lorazepam (RIS‐USA‐102 2002) (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.38, P = 0.73; 1 trial, 105 participants).

(f) Time to onset of symptom reduction or response

(i) Risperidone monotherapy No difference was found between risperidone and haloperidol in time to response (see figures 02.02 to 02.06).

(g) Requirement for inpatient care e.g. length of stay No data were reported.

2. General Health and Social Functioning No data were reported.

3. Acceptability of Treatments

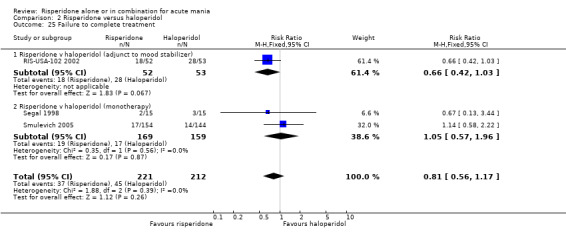

(a) Completion of trial treatment was used as an indicator of overall treatment acceptability (i) Risperidone monotherapy There was no evidence of a difference between risperidone monotherapy and haloperidol in the proportion of participants who failed to complete treatment (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.96, P = 0.87; chi‐squared 0.35, df = 1, P = 0.56; 2 trials, 328 participants).

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant A smaller proportion of patients on risperidone than on haloperidol as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant failed to complete treatment but the difference was not significant (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.03; 1 trial, 105 participants).

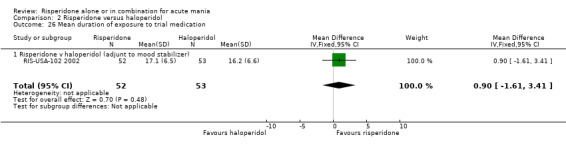

There was no significant difference between risperidone and haloperidol as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant in terms of the mean duration of adherence to trial medication (WMD 0.90, 95% CI ‐1.61 to 3.41, P = 0.48; 1 trial, 105 participants).

(iii) Combined results for monotherapy and adjunctive therapy Analysis of the combined results for monotherapy and adjunctive treatments showed no difference between risperidone and haloperidol in the proportion of participants who completed treatment (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.17 trial, P = 0.26; chi‐squared 1.88, df = 2, P = 0.39; 3 trials, 433 participants).

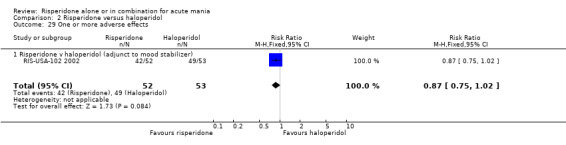

4. Adverse Effects

Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant: There was no difference between risperidone and haloperidol as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant in terms of the number of participants who experienced one or more adverse effects (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.02, P = 0.08; 1 trial, 105 participants). (a) Movement Disorders

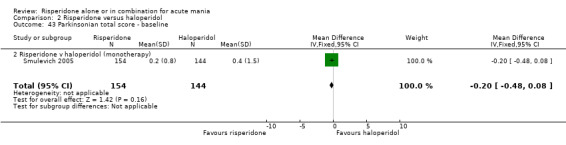

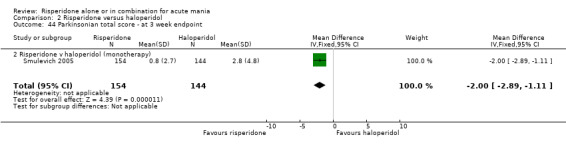

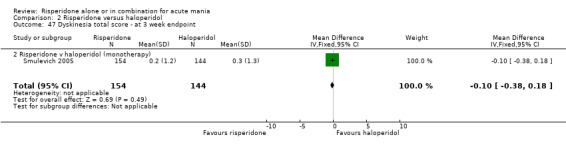

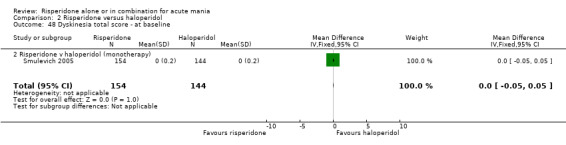

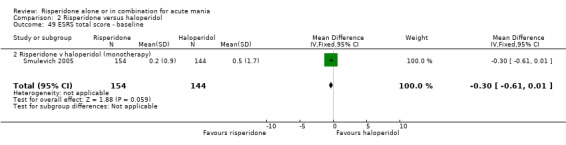

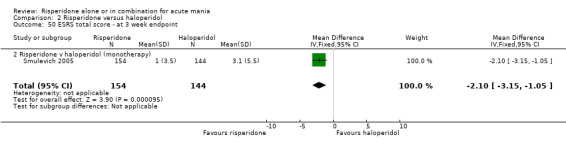

Unless otherwise stated, all adverse effect data for monotherapy comparisons was reported in Smulevich 2005.

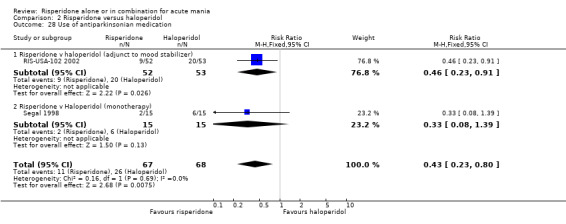

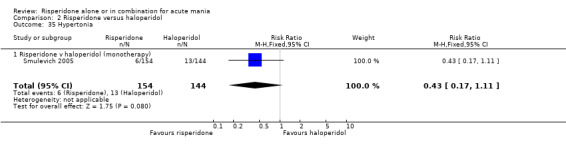

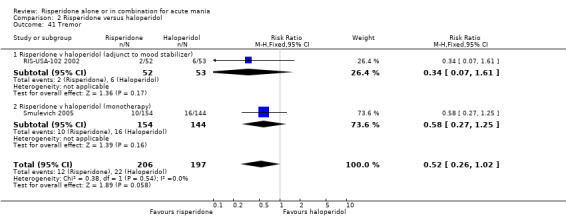

(i) Risperidone as monotherapy Risperidone was associated with lower endpoint scores on the ESRS than haloperidol (WMD ‐2.10, 95% CI ‐3.15 to ‐1.05, P < 0.0001; 1 trial 298 participants) and with a lower incidence of extrapyramidal disorder (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.63, P < 0.0001; 1 trial, 298 participants). This difference was only significant for the parkinsonian subscale (see figures 02.43 to 02.48). No difference was seen in incidence of hyperkinesia (RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.12, P = 0.11; 1 trial, 298 participants); hypertonia (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.11, P = 0.08; 1 trial, 298 participants) or tremor (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.25, P = 0.16; 1 trial, 298 participants). There was no evidence for a difference between risperidone and haloperidol monotherapies in use of anticholinergic medication (Segal 1998) (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.39, P = 0.13; 1 trial, 30 participants).

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was no evidence for a difference between risperidone and haloperidol as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant in the incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.07, P = 0.07; 1 trial, 105 participants) or tremor (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.07 to 1.61, P = 0.17; 1 trial, 105 participants). A smaller proportion of participants on risperidone than haloperidol as adjunctive treatment required anticholinergic medication (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.91, P = 0.03; 1 trial 105 participants).

(b) Cardiovascular adverse effects

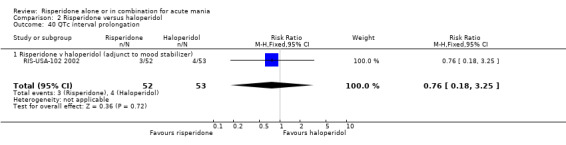

(i) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was no evidence of a difference between risperidone and haloperidol QTc interval prolongation (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.18 to 3.25, P = 0.72; 1 trial, 105 participants).

(c) Depression No data were reported.

(d) Weight gain

(i) Risperidone monotherapy Mean weight change was 0.3 (SD 3.70) kg for risperidone and 0.40 (SD 2.70) kg for haloperidol, this difference was not statistically significant (WMD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.83 to 0.63, P = 0.79; 1 trial, 298 participants).

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant Risperidone caused greater weight gain than haloperidol as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant (WMD 2.23, 95% CI 1.16 to 3.30, P < 0.0001; 1 trial, 105 participants) (see figure 02.31). For risperidone the mean weight gain was 2.36 (SD 3.11) kg whereas participants for haloperidol had a mean weight loss of 0.13 (SD 2.40) kg.

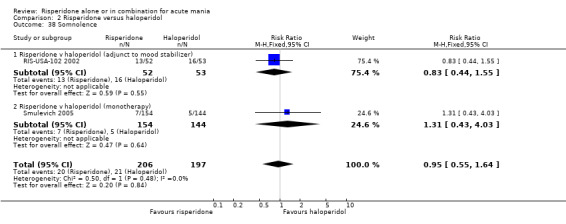

(e) Sedation

(i) Risperidone monotherapy There was no evidence of a difference between risperidone and haloperidol in the incidence of sedation (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.43 to 4.03, P = 0.64, 1 trial, 298 participants).

(ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was no evidence of a difference between risperidone and haloperidol in the incidence of sedation (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.55, P = 0.55; 1 trial, 105 participants).

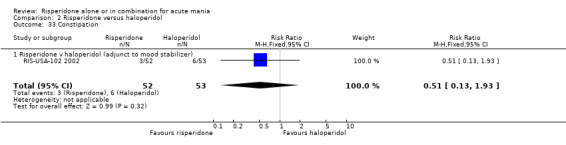

(f) Gastrointestinal disturbance

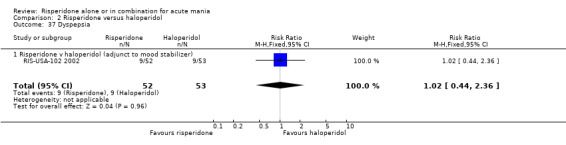

(i) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was no evidence of a difference between risperidone and haloperidol in dyspepsia (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.36, P = 0.96; 1 trial, 105 participants) and constipation (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.13 to 1.93, P = 0.32; 1 trial, 105 participants).

(g) Haematological changes

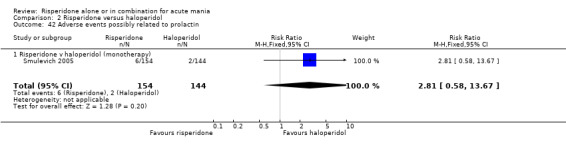

(i) Risperidone monotherapy There was no difference between risperidone and haloperidol in incidence of adverse events possibly related to prolactin elevation (RR 2.81, 95% CI 0.58 to 13.67, P = 0.20, 1 trial, 298 participants).

(h) Diabetes No data were reported.

(i) Alopecia No data were reported.

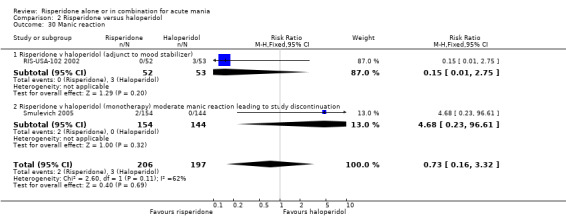

(j) Worsening of mania

(i) Risperidone monotherapy No difference was found between risperidone and haloperidol in the number of participants withdrawing from treatment due to a manic reaction (Smulevich 2005) (RR 4.68, 95% CI 0.23 to 96.61, P = 0.32, 1 trial, 403 participants). (ii) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was no evidence of a difference between risperidone and haloperidol as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant in the proportion of people for whom worsening of a manic reaction was reported (RR 0.15, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.75, P = 0.20; 1 trial, 105 participants).

(iii) Combined results for monotherapy and adjunctive therapy The overall incidence of manic reaction reported was 2/206 for risperidone and 3/197 for haloperidol.

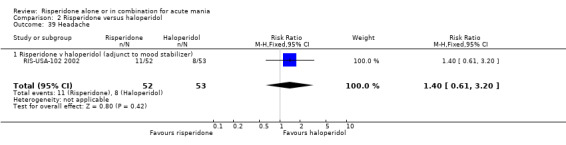

(k) Other adverse effects

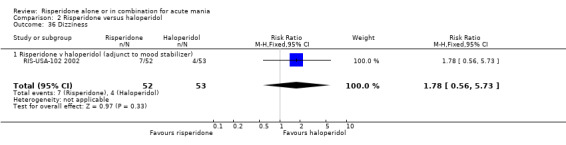

(i) Risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant There was no evidence of a difference between risperidone and haloperidol as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant in incidence of a further two adverse effects (RIS‐USA‐102 2002): headache (RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.61 to 3.20, P = 0.42; 1 trial, 105 participants) and dizziness (RR 1.78, 95% CI 0.56 to 5.73, P = 0.33, 1 trial, 105 participants).

5. Mortality Only one trial (RIS‐INT‐69 2004) reported any deaths. In this trial one participant died as a result of a road traffic accident 20 days after withdrawing from the trial and another as a result of a choking accident 13 days after withdrawal.

RISPERIDONE VERSUS LITHIUM

1. Efficacy

(a) Response or remission of manic symptoms The only available efficacy data related to seclusion during the trial.

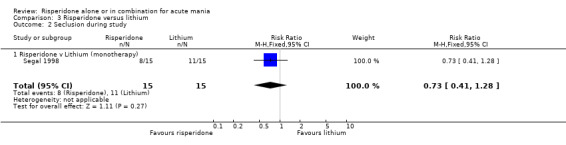

There was no evidence of a significant difference between risperidone monotherapy and lithium in the proportion of participants who were secluded for a period of time during the treatment period (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.28 trial, P = 0.27; 1 trial, 30 participants). 2. General Health and Social Functioning No data were reported.

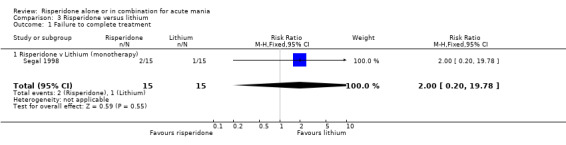

3. Acceptability of Treatments There was no difference between risperidone monotherapy and lithium in the proportion of participants who failed to complete treatment (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.20 to 19.78, P = 0.55; 1 trial, 30 participants). 4. Adverse Effects No data on adverse effects were reported in a form that could be included in the analysis.

5. Mortality None of the trials reported any deaths during the treatment periods.

Discussion

Results from six trials were included in this review. All were supported or funded by the manufacturers of risperidone, which may have introduced some bias in favour of risperidone (Yaphe 2001). The exclusion of concomitant therapies and many forms of comorbidity, in particular substance abuse, limit the external validity of the results. Only one trial (RIS‐INT‐46 2002) reported the design in sufficient detail in terms of allocation concealment and maintenance of blinding for the quality to be assessed as adequate. Although the search was thorough it is still possible that there are unpublished trials which have not been identified but the small number of trials identified hinders the detection of any publication bias.

The main feature of all the trials was the high rate of withdrawal from the trial. This is similar to the findings of a review of olanzapine for treatment of mania (Rendell 2003) and leads to considerable uncertainty introduced by the LOCF method of imputing data from the time a patient withdrew from follow‐up. This method fails to take into account whether a patient was getting worse or better at the point when the last measurement was taken (Streiner 2002). Since the natural course of a manic episode is to remit over time it is possible that, for each treatment arm, LOCF would give smaller mean changes in mania ratings and response rates than the values that would be recorded if all participants were assessed at the end of the study period. There is, however, no way to tell precisely what effect LOCF has on results. The degree of uncertainty and potential for bias introduced by LOCF depends on the proportion of participants lost to follow up and the length of time over which measurements are carried forward. There is also the possibility of bias if, on average, patients in one arm withdraw from follow up earlier that those in other arms.

The possibility that there was variation between centres in multi‐centre studies must also be considered in the interpretation of results.

Risperidone was more effective than placebo at reducing manic symptoms and achieving and sustaining remission. There was quantitative heterogeneity between the monotherapy trials with the increased efficacy of risperidone over placebo being greater for RIS‐IND‐6 2002 than for RIS‐INT‐69 2004 and Smulevich 2005. Comparison of the trials revealed two particular differences that may have contributed to the heterogeneity. At baseline, participants in RIS‐IND‐6 2002 had more severe manic symptoms than those in RIS‐INT‐69 2004 and Smulevich 2005 (mean baseline YMRS 37.2, 29.1 and 31.8 respectively). In addition to this, the mean modal dose of risperidone used in RIS‐IND‐6 2002 was 5.6mg/day compared to 4.1mg/day for RIS‐INT‐69 2004 and 4.2mg/day for Smulevich 2005. However it is also possible that differences reflect variations between sites in the measurement of YMRS scores. The observed quantitative heterogeneity between the trials means that it is not possible to give a reliable estimate of the effect size but the meta‐analysis of monotherapy and adjunctive therapy trials (excludes RIS‐USA‐102 2002 which did not report response rates on YMRS) includes the possibility of a relative risk reduction for failure to respond as high as 43% for risperidone compared to placebo. Risperidone, both as monotherapy and as adjunctive treatment, was more acceptable than placebo measured as completion of trial treatment and participants remained on risperidone for longer than placebo. There was heterogeneity between the monotherapy trials in failure to complete treatment with the difference between risperidone and placebo being greater in RIS‐IND‐6 2002 than in RIS‐INT‐69 2004 and Smulevich 2005. It is possible that participants in RIS‐IND‐6 2002 who were more severely ill than those in the other trials (see above) were more willing to persevere with treatment and to tolerate adverse effects. The proportion of patients failing to complete treatment in each group was higher for RIS‐INT‐69 2004 than for the other trials. It is possible that this is related to the study design which allows patients to transfer to an open‐label extension if trial treatment is considered ineffective. It may be that the option to terminate blinded treatment without withdrawing from the study influences participants and clinicians assessments of efficacy.

The relative risk of experiencing movement disorders was greater for risperidone than for placebo but for individual symptoms this was only significant for a small number of monotherapy comparisons, whereas for risperidone as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant it was only significant for overall incidence of extrapyramidal related adverse events. The observed quantitative heterogeneity in which patients in RIS‐IND‐6 2002 reported more EPS and tremor may be due to the higher mean modal dose of risperidone used in that trial. Risperidone was associated with more sedation than placebo and, as monotherapy, with more nausea. Combined results for the four trials that reported weight change showed an average weight gain of 1.2 kg for participants on risperidone. There was heterogeneity between monotherapy trials in weight gain with a difference in mean weight gain of 1.3 kg for participants on risperidone monotherapy. Since the trials were of the same duration and reported similar mean modal doses of risperidone the reasons for the heterogeneity are unclear. Weight gain is of particular concern because of the possible link with hyperlipidaemia and diabetes. The clinical significance of drug‐induced prolactin elevation is unclear but the normal range for prolactin is 15‐25 ng/ml and it is likely that some patients on risperidone would have experienced gynaecomastia and galactorrhoea. For many of the analyses of adverse events there was a wide confidence interval leading to considerable uncertainty about results from a clinical perspective.

The effect sizes for both efficacy and safety comparisons for which results were reported for monotherapy and adjunctive therapy trials were similar so that there was no evidence for interaction between risperidone and lithium or an anti‐convulsant. However, there was evidence that carbamazepine reduced the concentration of risperidone so that when risperidone is used concomitantly with carbamazepine it may be necessary to use higher doses of risperidone. The efficacy of risperidone was comparable to that of haloperidol both as monotherapies and as adjunctive treatments to lithium or an anticonvulsant. Risperidone caused less extrapyramidal symptom as indicated by the smaller proportion of participants on risperidone who required antiparkinsonian medication. The monotherapy trial Smulevich 2005 found no difference in weight gain between risperidone and haloperidol whereas the adjunctive treatment trial RIS‐USA‐102 2002 reported significantly greater weight gain for participants on risperidone. As for the placebo comparisons, it is unclear why weight gain in Smulevich 2005 is less than that in other trials. For a number of other comparisons the confidence intervals did included the possibility of clinically significant differences between risperidone and haloperidol but the results did not reach significance.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Risperidone is effective in reducing manic symptoms both as monotherapy and as an adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant. The main adverse effects are weight gain, extrapyramidal effects and sedation.

Risperidone is comparable in efficacy to haloperidol both as monotherapy and as adjunctive treatment to lithium or an anticonvulsant. The main adverse effects are weight gain, extrapyramidal effects and sedation.

Implications for research.

Higher quality trials are required to provide more reliable and precise estimates of costs and benefits of risperidone. Trials are also needed comparing risperidone to other treatments for mania such as lithium and anticonvulsants. Such trials should report data on speed of return to normal functioning and should include patients with comorbidity.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2003 Review first published: Issue 1, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 October 2005 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Notes

This review was undertaken as part of a body of work that will contribute to a complete review of treatments for acute mania.

Acknowledgements

We thank Heather Wilder and Sarah Stockton, Information Scientists, Centre for Evidence Based Mental Health and the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group editorial staff for assistance in developing the search strategy for the review and for conducting several of the database searches.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Risperidone versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mean change in YMRS ‐ all participants | 4 | 775 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.59 [‐7.06, ‐4.13] |

| 1.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) | 2 | 238 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.16 [‐7.99, ‐2.32] |

| 1.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) | 2 | 537 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.75 [‐7.46, ‐4.04] |

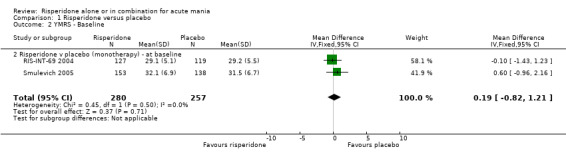

| 2 YMRS ‐ Baseline | 2 | 537 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 [‐0.82, 1.21] |

| 2.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ at baseline | 2 | 537 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 [‐0.82, 1.21] |

| 3 YMRS ‐ at day 3 | 1 | 246 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.8 [‐4.25, ‐1.35] |

| 3.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ at day 3 | 1 | 246 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.8 [‐4.25, ‐1.35] |

| 4 YMRS ‐ Week 1 | 3 | 517 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.77 [‐4.26, ‐1.28] |

| 4.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) ‐ change in YMRS | 2 | 230 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.54 [‐5.73, ‐1.36] |

| 4.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ at week 1 | 1 | 287 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.10 [‐4.13, ‐0.07] |

| 5 YMRS ‐ Week 2 | 3 | 455 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.53 [‐4.27, ‐0.78] |

| 5.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) ‐ change in YMRS | 2 | 182 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.25 [‐5.06, 0.56] |

| 5.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ at week 2 | 1 | 273 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.70 [‐4.93, ‐0.47] |

| 6 YMRS ‐ Week 3 | 3 | 396 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.03 [‐5.87, ‐2.18] |

| 6.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) ‐ change in YMRS | 2 | 142 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.01 [‐6.09, 0.06] |

| 6.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ at week 3 | 1 | 254 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.60 [‐6.91, ‐2.29] |

| 7 YMRS ‐ Week 3 endpoint data | 3 | 433 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.30 [‐6.20, ‐2.40] |

| 7.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) ‐ change in YMRS | 2 | 142 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.01 [‐6.09, 0.06] |

| 7.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ endpoint data at week 3 | 1 | 291 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.10 [‐7.52, ‐2.68] |

| 8 YMRS ‐ participants without psychotic symptoms at baseline | 3 | 394 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.47 [‐7.35, ‐3.59] |

| 8.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) ‐ change in YMRS | 1 | 58 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐6.0 [‐10.77, ‐1.23] |

| 8.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ change in YMRS | 1 | 139 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.9 [‐9.07, ‐2.73] |

| 8.3 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ YMRS at 3 weeks | 1 | 197 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.00 [‐7.67, ‐2.33] |

| 9 YMRS ‐ participants with psychotic symptoms at baseline | 3 | 241 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.54 [‐8.24, ‐2.84] |

| 9.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) ‐ change in YMRS | 1 | 40 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐6.1 [‐13.14, 0.94] |

| 9.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ change in YMRS | 1 | 107 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.2 [‐8.80, ‐1.60] |

| 9.3 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ YMRS at 3 weeks | 1 | 94 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.90 [‐10.90, ‐0.90] |

| 10 Failure to respond (YMRS) | 4 | 982 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.51, 0.86] |

| 10.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) | 1 | 151 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.57, 1.04] |

| 10.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) | 3 | 831 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.45, 0.89] |

| 11 Failure to respond (‐defined as very much or much improved on CGI) | 2 | 254 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.58, 0.91] |

| 11.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) | 2 | 254 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.58, 0.91] |

| 12 Failure to respond (‐defined as very much improved on CGI) | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.64, 0.88] |

| 12.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.64, 0.88] |

| 13 Failure to achieve remission (YMRS <= 12) | 2 | 349 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.64, 0.87] |

| 13.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.46, 0.92] |

| 13.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) | 1 | 246 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.66, 0.92] |

| 14 Failure to achieve remission (YMRS <= 8) | 2 | 394 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.60, 0.79] |

| 14.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.54, 0.94] |

| 14.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) | 1 | 291 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.58, 0.79] |

| 15 Failure to achieve remission (YMRS <= 8 and HAMD‐21 <=7) | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.68, 0.97] |

| 15.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.68, 0.97] |

| 16 Failure to achieve sustained remission (YMRS <=8) | 1 | 291 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.57, 0.77] |

| 16.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) | 1 | 291 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.57, 0.77] |

| 17 Failure to achieve remission (YMRS <= 8 and MADRS <=12) | 1 | 246 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.80, 0.98] |

| 17.1 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) | 1 | 246 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.80, 0.98] |

| 18 Mean change in HAMD‐21 | 1 | 63 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.5 [‐2.11, 5.11] |

| 18.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) | 1 | 63 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.5 [‐2.11, 5.11] |

| 19 MADRS ‐ baseline | 1 | 291 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [‐0.47, 1.07] |

| 19.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ baseline | 1 | 291 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [‐0.47, 1.07] |

| 20 MADRS ‐ week 3 | 1 | 254 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.4 [‐2.17, ‐0.63] |

| 20.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ week 3 | 1 | 254 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.4 [‐2.17, ‐0.63] |

| 21 MADRS ‐ endpoint data week 3 | 1 | 291 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.40 [‐2.39, ‐0.41] |

| 21.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ endpoint data week 3 | 1 | 291 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.40 [‐2.39, ‐0.41] |

| 22 CGI ‐ Baseline | 2 | 537 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.13, 0.14] |

| 22.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ at baseline | 2 | 537 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.13, 0.14] |

| 23 CGI ‐ at week 3 | 1 | 257 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.5 [‐0.76, ‐0.24] |

| 23.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ at week 3 | 1 | 257 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.5 [‐0.76, ‐0.24] |

| 24 Change in CGI | 2 | 537 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.59 [‐0.79, ‐0.39] |

| 24.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) | 2 | 537 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.59 [‐0.79, ‐0.39] |

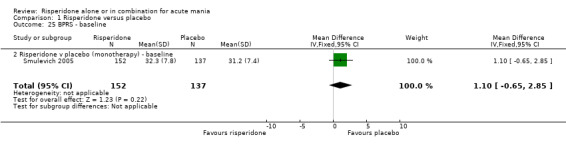

| 25 BPRS ‐ baseline | 1 | 289 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [‐0.65, 2.85] |

| 25.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ baseline | 1 | 289 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [‐0.65, 2.85] |

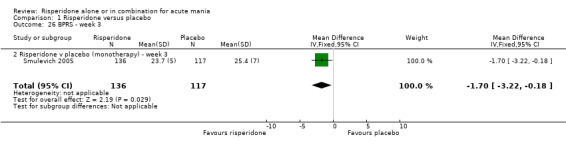

| 26 BPRS ‐ week 3 | 1 | 253 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.70 [‐3.22, ‐0.18] |

| 26.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ week 3 | 1 | 253 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.70 [‐3.22, ‐0.18] |

| 27 BPRS ‐ all participants | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 27.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) ‐ change in BPRS | 1 | 138 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.3 [‐8.35, ‐2.25] |

| 27.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ BPRS at 3 weeks endpoint data | 1 | 290 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.60 [‐3.44, 0.24] |

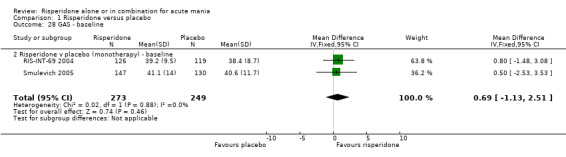

| 28 GAS ‐ baseline | 2 | 522 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [‐1.13, 2.51] |

| 28.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ baseline | 2 | 522 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [‐1.13, 2.51] |

| 29 GAS ‐ week 3 | 1 | 250 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.90 [3.33, 10.47] |

| 29.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ week 3 | 1 | 250 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.90 [3.33, 10.47] |

| 30 GAS‐ endpoint data week 3 | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 30.1 Risperidone v placebo ‐ change in GAS at endpoint | 1 | 245 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.0 [3.54, 10.46] |

| 30.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ endpoint data week 3 | 1 | 277 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.30 [3.56, 11.04] |

| 31 Failure to complete treatment | 5 | 1097 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.52, 0.82] |

| 31.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) | 2 | 253 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.51, 0.92] |

| 31.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) | 3 | 844 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.38, 0.95] |

| 32 Mean duration of treatment | 2 | 549 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [1.06, 2.94] |

| 32.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) | 2 | 549 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [1.06, 2.94] |

| 33 Use of rescue medication (for sedation) | 4 | 806 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.98, 1.21] |

| 33.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) ‐ lorazepam | 2 | 253 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.96, 1.37] |

| 33.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ lorazepam, diazepam or choral hydrate for 10 days of more | 1 | 294 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.86, 1.66] |

| 33.3 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) ‐ received lorazepam | 1 | 259 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.89, 1.12] |

| 34 Use of antiparkinsonian medication | 2 | 362 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.99 [1.18, 3.35] |

| 34.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.21 [0.73, 6.71] |

| 34.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) | 1 | 259 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.93 [1.07, 3.48] |

| 35 One or more adverse effects | 2 | 253 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.88, 1.23] |

| 35.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) | 2 | 253 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.88, 1.23] |

| 36 Manic reaction | 4 | 806 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.55, 2.61] |

| 36.1 Risperidone v placebo (adjunct to mood stabilizer) | 2 | 253 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.05, 2.06] |

| 36.2 Risperidone v placebo (monotherapy) moderate manic reaction leading to study discontinuation | 1 | 294 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.55 [0.22, 93.93] |