Abstract

NOTCH1, NOTCH2, NOTCH3 and NOTCH4 are transmembrane receptors that transduce juxtacrine signals of the delta-like canonical Notch ligand (DLL)1, DLL3, DLL4, jagged canonical Notch ligand (JAG)1 and JAG2. Canonical Notch signaling activates the transcription of BMI1 proto-oncogene polycomb ring finger, cyclin D1, CD44, cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1A, hes family bHLH transcription factor 1, hes related family bHLH transcription factor with YRPW motif 1, MYC, NOTCH3, RE1 silencing transcription factor and transcription factor 7 in a cellular context-dependent manner, while non-canonical Notch signaling activates NF-κB and Rac family small GTPase 1. Notch signaling is aberrantly activated in breast cancer, non-small-cell lung cancer and hematological malignancies, such as T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. However, Notch signaling is inactivated in small-cell lung cancer and squamous cell carcinomas. Loss-of-function NOTCH1 mutations are early events during esophageal tumorigenesis, whereas gain-of-function NOTCH1 mutations are late events during T-cell leukemogenesis and B-cell lymphomagenesis. Notch signaling cascades crosstalk with fibroblast growth factor and WNT signaling cascades in the tumor microenvironment to maintain cancer stem cells and remodel the tumor microenvironment. The Notch signaling network exerts oncogenic and tumor-suppressive effects in a cancer stage- or (sub)type-dependent manner. Small-molecule γ-secretase inhibitors (AL101, MRK-560, nirogacestat and others) and antibody-based biologics targeting Notch ligands or receptors [ABT-165, AMG 119, rovalpituzumab tesirine (Rova-T) and others] have been developed as investigational drugs. The DLL3-targeting antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) Rova-T, and DLL3-targeting chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells (CAR-Ts), AMG 119, are promising anti-cancer therapeutics, as are other ADCs or CAR-Ts targeting tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 17, CD19, CD22, CD30, CD79B, CD205, Claudin 18.2, fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)2, FGFR3, receptor-type tyrosine-protein kinase FLT3, HER2, hepatocyte growth factor receptor, NECTIN4, inactive tyrosine-protein kinase 7, inactive tyrosine-protein kinase transmembrane receptor ROR1 and tumor-associated calcium signal transducer 2. ADCs and CAR-Ts could alter the therapeutic framework for refractory cancers, especially diffuse-type gastric cancer, ovarian cancer and pancreatic cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Phase III clinical trials of Rova-T for patients with small-cell lung cancer and a phase III clinical trial of nirogacestat for patients with desmoid tumors are ongoing. Integration of human intelligence, cognitive computing and explainable artificial intelligence is necessary to construct a Notch-related knowledge-base and optimize Notch-targeted therapy for patients with cancer.

Keywords: angiogenesis, cancer-associated fibroblasts, computer-aided diagnostics, deep learning, immune evasion, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, natural language processing, neural network, regulatory T cells, text mining, HES1, HEY1, REST, TCF7

1. Introduction

NOTCH1, NOTCH2, NOTCH3 and NOTCH4 are cell surface receptors that transduce juxtacrine signals of delta-like canonical Notch ligand (DLL)1, DLL3, DLL4, jagged canonical Notch ligand (JAG)1 and JAG2 from adjacent cells (1-3). Germline mutations in the NOTCH1, NOTCH2 and NOTCH3 genes cause Adams-Oliver syndrome, Alagille syndrome and cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy, respectively (4), and DLL4-NOTCH3 signaling in human vascular organoids induces basement membrane thickening and drives vasculopathy in the diabetic microenvironment (5). By contrast, somatic alterations in the genes encoding Notch signaling components drive various types of human cancer, such as breast cancer, small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) (6-9). Notch signaling dysregulation is involved in a variety of pathologies, including cancer and non-cancerous diseases.

Small-molecule inhibitors, antagonistic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), bispecific antibodies or biologics (bsAbs) and chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells (CAR-Ts) targeting Notch signaling components have been developed as investigational anti-cancer drugs (10-12). The safety, tolerability and anti-tumor effects of these compounds have been studied in clinical trials; however, Notch-targeted therapeutics are not yet approved for the treatment of patients with cancer. Here, Notch signaling in the tumor microenvironment and Notch-targeted therapeutics are reviewed, and perspectives on Notch-related precision oncology are discussed with emphases on biologics, clinical sequencing and explainable artificial intelligence.

2. Notch signaling overview

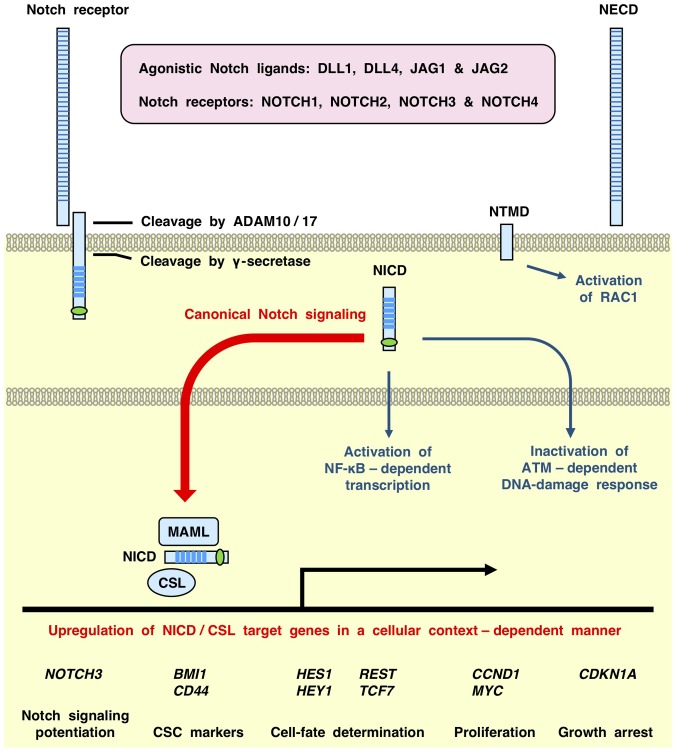

DLL1, DLL3, DLL4, JAG1 and JAG2 are transmembrane ligands of Notch receptors (2,6,13). DLL1, DLL4, JAG1 and JAG2 are agonistic Notch ligands (Fig. 1), whereas DLL3 without the conserved N-terminal module of agonistic Notch ligands is an aberrant Notch ligand that can antagonize DLL1-Notch signaling. EGF-like repeats 1-13 in the extracellular region of NOTCH1 are involved in DLL1/4 signaling and the EGF-like repeats 10-24 of NOTCH1 are involved in JAG1/2 signaling (14). β-1,3-N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase lunatic fringe and β-1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase manic fringe transfer N-acetylglucosamine to O-fucose on the EGF repeats in the extracellular region of Notch receptors, which enhances DLL1-NOTCH1 signaling and inhibits JAG1-NOTCH1 signaling (15). DLL1 promotes myogenesis through transient NOTCH1 activation, whereas DLL4 inhibits myogenesis through sustained NOTCH1 activation (16). The expression profile of DLL/JAG ligands and extracellular modification of Notch receptors affect receptor-ligand interactions and modulate the outputs and strength of the Notch signaling cascades (17); however, the landscape of interactions between Notch ligands and receptors, especially those of NOTCH2, NOTCH3 and NOTCH4, remain elusive.

Figure 1.

Overview of canonical and non-canonical Notch signaling cascades. DLL/JAG agonistic ligands trigger proteolytic cleavage of Notch receptors to generate the NECD, NTMD and NICD. Canonical Notch signaling cascades: NICD/CSL-dependent transcriptional activation of target genes, such as BMI1, CCND1, CD44, HES1, HEY1, MYC, NOTCH3, REST and TCF7, in a cellular context-dependent manner. Non-canonical Notch signaling cascades: CSL-independent cellular responses, such as NTMD-dependent activation of RAC1, NICD-dependent activation of NF-κB and NICD-dependent inhibition of ATM. DLL4-NOTCH1 signaling in endothelial cells induces NTMD-mediated assembly of cadherin-5, receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase F and TRIO and F-actin-binding protein, which activates RAC1 to maintain vascular barrier function through cytoskeletal reorganization. By contrast, NOTCH1 activation in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia leads to the interaction of NICD with the IκB kinase complex and ATM to activate NF-κB-dependent transcription and inhibit ATM-dependent DNA-damage response, respectively. DLL, delta-like canonical Notch ligand; JAG, jagged canonical Notch ligand; NECD, Notch extracellular domain; NTMD, Notch transmembrane domain; NICD, Notch intracellular domain; ADAM10, disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10; ATM, serine-protein kinase ATM; MAML, mastermind like protein; CSL, CBF1-suppressor of hairless-LAG1; BMI1, BMI1 proto-oncogene polycomb ring finger; CCND1, cyclin D1; HES1, hes family bHLH transcription factor 1; HEY1, hes related family bHLH transcription factor with YRPW motif 1; REST, RE1 silencing transcription factor; TCF7, transcription factor 7; RAC1, Ras-related protein Rac1.

Interactions with DLL/JAG agonistic ligands trigger sequential proteolytic cleavage of Notch receptors by disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein (ADAM)10/17 and γ-secretase (2,6,18,19), which generates the following: i) Notch extracellular domain; ii) Notch transmembrane domain (NTMD); and iii) Notch intracellular domain (NICD) (Fig. 1). The NICD is then translocated to the nucleus and associates with CBF1-suppressor of hairless-LAG1 (CSL) and mastermind like proteins (MAML1, MAML2 or MAML3) to activate the transcription of target genes. NICD/CSL-dependent transcription of Notch target genes is defined as the canonical Notch signaling cascade (20), whereas CSL-independent cellular responses, such as NICD-dependent activation of NF-κB (21), NICD-dependent inhibition of serine-protein kinase ATM (22) and NTMD-dependent activation of Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (RAC1) (23), are defined as non-canonical Notch signaling cascades (Fig. 1).

NICDs undergo posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination and PARylation. Cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)8-dependent phosphorylation of the NOTCH1 intracellular domain (NICD1) within the intracellular proline-, glutamate-, serine- and threonine-rich region leads to F-box/WD repeat-containing protein 7 (FBXW7)-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (24,25), whereas ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 7-mediated deubiquitination stabilizes NOTCH1 receptors (26). SRC-dependent phosphorylation of NICD1 within the intracellular ankyrin repeat region represses Notch signaling through blockade of the NICD1-MAML interaction and degradation of NICD1 (27). AKT-dependent phosphorylation of NICD4 at S1495, S1847, S1865 and S1917 tethers NICD4 in the cytoplasm and represses NICD4-dependent transcription (28). MDM2-dependent NICD4 ubiquitination and E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase LNX (NUMB)-dependent NICD1 ubiquitination degrade NICDs and attenuate Notch signaling (29,30), whereas MDM2-dependent NICD1 ubiquitination does not degrade NICD1 and activates Notch signaling (31). Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase tankyrase-1 (TNKS) PARylates NOTCH1, NOTCH2 and NOTCH3, and TNKS-dependent PARylation of NOTCH2 is required for nuclear translocation of the NICD (32). Posttranslational modifications of NICDs modulate their stability and intracellular localization to fine-tune intracellular Notch signaling.

Canonical Notch signals induce the upregulation of NICD/CSL-target genes (Fig. 1), such as BMI1 proto-oncogene polycomb ring finger (BMI1) (33,34), cyclin D1 (CCND1) (35,36), CD44 (37), CDKN1A (p21) (38,39), hes family bHLH transcription factor 1 (HES1) (40,41), hes family bHLH transcription factor 4 (HES4) (36,42), hes related family bHLH transcription factor with YRPW motif 1 (HEY1) (36,42,43), MYC (42,44,45), NOTCH3 (42,46), Notch regulated ankyrin repeat protein (NRARP) (36,41,42,47), nuclear factor erythroid 2 like 2 (48), olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4) (49), RE1 silencing transcription factor (REST) (41) and transcription factor 7 (TCF7) (50,51). Canonical Notch target genes are upregulated in a cellular context-dependent manner through dynamic patterns of Notch signaling activation, the epigenetic status of target genes and the availability of other transcription factors (16,52).

3. Notch signaling in tumor cells

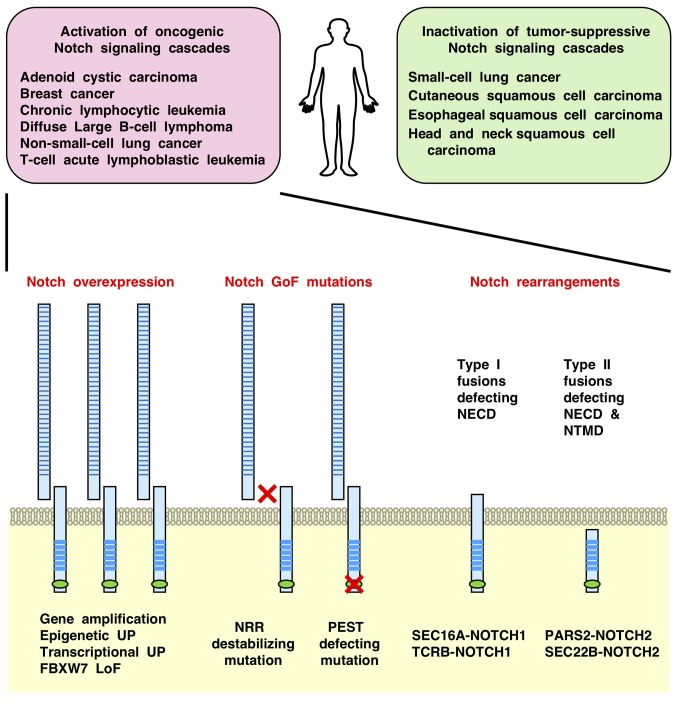

Notch signaling molecules are frequently altered in T-ALL (80%) (53) and microsatellite-instable (MSI) or DNA polymerase-ε catalytic subunit A (POLE)-mutant subtypes of gastric and esophageal cancer (79%), colorectal cancer (70%) and uterine corpus endometrial cancer (64%) (54). Notch signaling is activated owing to gain-of-function (GoF) NOTCH alterations in T-ALL (55-57), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (58,59), diffuse large B cell lymphoma (60,61), mantle cell lymphoma (62), breast cancer (63-65) and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (66) as well as loss-of-function (LoF) FBXW7 mutations in MSI or POLE-mutant cancers and hematological malignancies (53,54) (Fig. 2). By contrast, Notch signaling is inactivated as a result of LoF NOTCH alterations in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (67), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) (68,69), esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (70,71) and SCLC (72) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Genetic alterations in the Notch signaling components in human cancers. Notch signaling cascades are aberrantly activated in solid tumors and hema-tological malignancies owing to overexpression of Notch receptors and GoF mutations or fusions in the NOTCH family genes. By contrast, Notch signaling cascades are inactivated in small-cell lung cancer and squamous cell carcinomas owing to LoF mutations in the NOTCH family genes, especially NOTCH1. NECD, Notch extracellular domain; NRR, Notch negative regulatory region; NTMD, Notch transmembrane domain; PEST, proline-, glutamate-, serine- and threonine-rich domain that undergoes FBXW7-mediated ubiquitylation; UP, upregulation; GoF, gain-of-function; LoF, loss-of-function; SEC16A, protein transport protein Sec16A; TCRB, T cell receptor β locus; PARS2, prolyl-tRNA synthetase 2, mitochondrial; SEC22B, vesicle-trafficking protein SEC22b.

Transcriptional or epigenetic alterations also dysregulate Notch signaling in the absence of genetic alterations in the Notch signaling components (Fig. 2). Oncogenic Notch signaling is reinforced due to NOTCH3 upregulation through ETS-related transcription factor ELF3-dependent transcription in KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma (73); JAG1 upregulation through CpG hypomethylation in renal cell carcinoma (74); and upregulation of JAG1, MAML2, NOTCH1, NOTCH2 and NOTCH3, partially through increased histone H3K27 acetylation, in neuroblastoma (75). Tumor-suppressive Notch signaling is inactivated in Ewing's sarcoma due to repression of JAG1 by RNA binding protein EWS-friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor fusion protein (76) and repression of NOTCH1 and REST through decreased H3K27 acetylation in SCLC (77).

Notch signaling activation promotes tumor cell proliferation or survival and in vivo tumorigenesis through: i) Direct upregulation of CCND1 (35) and MYC (44); ii) HES1-mediated CDKN1B (p27) repression and subsequent cellular proliferation (78); iii) HES1-mediated dual specificity phosphatase 1 repression and subsequent ERK activation (79); iv) HES1-mediated phosphatase and tensin homolog repression and subsequent AKT signaling activation (80); and v) HES1-mediated STAT3 activation (81,82) and CSL-independent, NF-κB-dependent interleukin 6 (IL6) upregulation, and subsequent JAK-STAT signaling activation (83). By contrast, Notch signaling activation blocks tumor cell proliferation or survival and in vivo tumorigenesis through: i) Direct upregulation of CDKN1A (38,39); ii) HES1-mediated GLI family zinc finger 1 repression (84); iii) HEY1-mediated snail family transcriptional repressor 2 and twist family bHLH transcription factor 1 repression, and subsequent mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (85); and iv) HEY1-mediated IL6 downregulation and subsequent depletion of cancer stem cells (86). Because Notch signals drive lateral induction as well as lateral inhibition to fine-tune organ development and homeostasis (17,87,88), bifunctional cellular responses are a common feature of Notch signaling during embryogenesis, adult tissue homeostasis and tumorigenesis.

Oncogenic Notch signaling is activated in NSCLC owing to GoF NOTCH1 mutations or ELF3-dependent NOTCH3 upregulation (66,73), whereas tumor-suppressive Notch signaling is inactivated in SCLC owing to LoF NOTCH1 mutations or epigenetic NOTCH1 repression (72,77). In HNSCC, tumor-suppressive Notch signaling is inactivated owing to LoF NOTCH1 mutations, but oncogenic Notch signaling is activated by JAG1, JAG2 or NOTCH3 upregulation (69,89). Tumor-suppressive Notch signaling is advantageous for maintaining a non-cancerous esophagus in middle-aged or elderly individuals (71), whereas oncogenic Notch signaling promotes the later stages of T-cell leukemogenesis (57) and B-cell lymphomagenesis (61). Because Notch signals intrinsically exert both oncogenic and tumor-suppressive effects (Fig. 1), epigenetic silencing or genetic inactivation of anti-tumorigenic Notch target genes may transfer the growth advantage from LoF Notch mutants to GoF Notch mutants.

4. Notch signaling in the tumor microenvironment

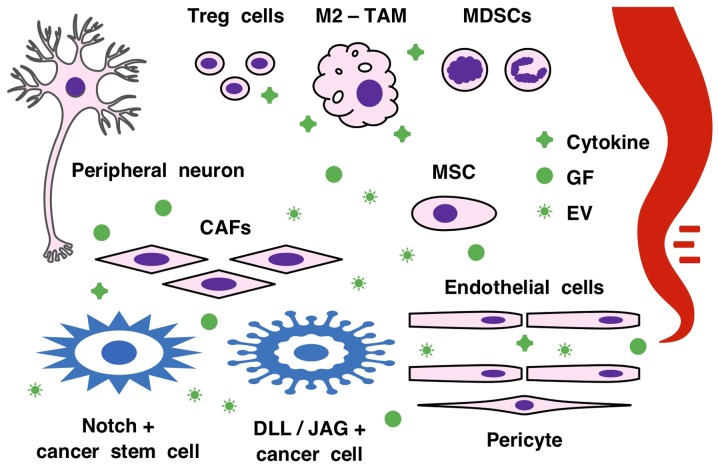

The tumor microenvironment comprises a heterogeneous population of cancer cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), endothelial cells, mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs), pericytes, peripheral neurons and immune cells (90-92) (Fig. 3). Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) revealed seven subgroups of fibroblasts, six subgroups of endothelial cells and 30 subgroups of immune cells in NSCLC (93), and four subtypes of cancer-associated fibroblasts in mouse mammary tumors (94). Cancerous and non-cancerous cells communicate via growth factors, cytokines and extracellular vesicles for paracrine signaling, and via membrane-type ligand/receptor pairs for juxtacrine signaling (3,95-97). These intercellular communications turn the anti-tumor microenvironment into a pro-tumor microenvironment through 'omics reprogramming' (98), which includes epigenetic changes (99), epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (100), immunoediting (101) and vascular remodeling (102).

Figure 3.

Notch signaling network in the tumor microenvironment. CSCs, differentiated cancer cells, CAFs, endothelial cells, MSCs, pericytes, peripheral neurons and immune cells, such as TAMs, MDSCs and regulatory T (Treg) cells, constitute the tumor microenvironment. Cancerous and non-cancerous cells communicate via Notch ligand/receptor pairs for juxtacrine signaling, as well as via cytokines, GFs and EVs for paracrine signaling. Notch signaling cascades crosstalk with FGF and WNT signaling cascades in the tumor microenvironment to support the self-renewal of CSCs and regulate angiogenesis and immunity. The Notch signaling network exerts oncogenic and tumor-suppressive functions in a cancer stage- or (sub)type-dependent manner. CAFs, cancer-associated fibroblasts; MSCs, mesenchymal stem/stromal cells; TAMs, tumor-associated macrophages; EV, extracellular vesicle; GF, growth factor, MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; CSC, cancer stem cell; DLL, delta-like canonical Notch ligand; JAG, jagged canonical Notch ligand.

Notch4 (Int3), fibroblast growth factor (Fgf) 3 (Int2), Fgf4, R-spondin (Rspo) 2 (Int7), Rspo3, Wnt1 (Int1) and Wnt3 (Int4) are proto-oncogenes that are activated by mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) (103-108). Notch signaling is required for the CSL-dependent expression of FGF7, FGF9, FGF10, FGF18, WNT1, WNT2 and WNT3 in dermal fibroblasts (39), while RSPO2 and RSPO3 interact with LGR4/5/6 to potentiate WNT signaling through Frizzled receptors (109,110). WNT signals enhance Notch signaling through JAG1 and NOTCH2 upregulation (111,112) but repress Notch signaling through NUMB and prospero homeobox 1 upregulation (113,114). Notch signals enhance β-catenin/LEF1 signaling via NRARP upregulation (47,115), but repress WNT/β-catenin signaling through OLFM4 upregulation (49,116). Notch and WNT signals converge on BMI1 and TCF7 to maintain slow-cycling cancer stem cells, partially through BMI1-induced telomerase reverse transcriptase upregulation and TCF7-induced CDKN2 upregulation, and on CCND1 and MYC to promote tumor proliferation (34,50,51,117-121). Colorectal cancer stem cells diverge into Notch- and WNT-dependent populations, and Notch signals may not be essential for bulk tumorigenesis (122,123). Notch signaling cascades crosstalk with FGF and WNT signaling cascades to orchestrate the tumor microenvironment for the maintenance of cancer stem cells.

Tumor angiogenesis is characterized by excessive endothelial sprouting from preexisting blood vessels, which leads to overgrowth of randomly organized and leaky tumor vessels (124-126). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFA) signaling through VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) (KDR) and neuropilin-1 (NRP1) receptors on endothelial tip cells drives vascular sprouting and DLL4 upregulation, and DLL4 signaling through Notch receptors on endothelial stalk cells restricts angiogenic sprouting and proliferation through downregulation of VEGFR2 and NRP1 (127,128). By contrast, Notch signaling induces JAG1 upregulation to antagonize the DLL4-dependent 'stalk' phenotype, and promote endothelial sprouting and proliferation (129,130). NICD1-dependent Notch signaling activation in endothelial cells promotes lung metastasis (131), but that in hepatic endothelial cells represses liver metastasis (132). Thus, Notch signaling regulates tumor angiogenesis and metastasis in a context-dependent manner.

Notch signals are involved in the development and homeostasis of immune cells: JAG1-Notch, DLL4-Notch1 and DLL1-Notch2 signals promote the self-renewal of long-term hematopoietic stem cells, differentiation of early T-lymphocyte progenitors and differentiation of marginal zone B lymphocytes, respectively (133,134); DLL1/4 and JAG1/2 signals induce the differentiation of naïve T lymphocytes into Th1 and Th2 cells, respectively (135,136); DLL1 and JAG1 signals promote the differentiation of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) into M1- and M2-like phenotypes, respectively (137,138); DLL1 or JAG1 on MSCs and JAG2 on hematopoietic progenitor cells induce the expansion of regulatory T (Treg) cells (139-141); and DLL4 on dendritic cells promotes Treg differentiation (142). By contrast, Notch-related immunological reprogramming in the tumor microenvironment may be more complex; scRNAseq revealed 20 subsets of T lymphocytes, including circulating Treg cells, non-cancerous tissue-infiltrating Treg cells and cancerous tissue-infiltrating Treg cells (143). For example, Notch-mediated immune regulation in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment is potentiated by the interaction between NICD and hypoxia-induced hypoxia inducible factor-1α, and is modulated by the crosstalk with the FGF, Hedgehog, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, VEGF and WNT signaling cascades (102,124,125,144-147). Notch1 signaling elicited immune evasion through TGF-β upregulation and accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and Treg cells in a mouse xenograft model with B16 melanoma cells (148), and through upregulation of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte protein 4, lymphocyte activation gene 3 protein, programmed cell death protein 1 and hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2, and accumulation of MDSCs, TAMs and Treg cells, in an engineered mouse model of HNSCC (149).

5. Therapeutics targeting Notch signaling cascades

Investigational drugs that target Notch signaling cascades are classified as follows: i) Small-molecule γ-secretase inhibitors that block the final step of ligand-induced processing of Notch receptors; ii) biologics, including mAbs, ADCs, bsAbs and CAR-Ts, that bind to the extracellular region of Notch ligands or receptors; iii) ADAM17 inhibitors that block the initial step of ligand-induced processing of Notch receptors; and iv) NICD protein-protein-interaction inhibitors that block the NICD-dependent transcription of Notch target genes (Table I).

Table I.

Notch-targeted therapeutics.

| Class | Drug | Alias | Mechanism of action | Stage of drug development | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSI | AL101 | BMS-906024 | Inhibition of S3 cleavage | Phase II (registration no. NCT03691207; GoF-Notch ACC; Recruiting) | (150) |

| Crenigacestat | LY3039478 | Inhibition of S3 cleavage | Phase I (registration no. NCT01695005; advanced cancer; completed) | (151) | |

| MRK-560 | Inhibition of S3 cleavage | Preclinical study (PSEN1-sublass GSI inhibitor for T-ALL) | (152) | ||

| Nirogacestat | PF-03084014 | Inhibition of S3 cleavage | Phase III (registration no. NCT03785964; desmoid tumors; recruiting) | (153,154) | |

| RO4929097 | Inhibition of S3 cleavage | Phase II (Multiple trials failed, insufficient or terminated) | (155,156) | ||

| mAb | Demcizumab | OMP-21M18 | Anti-DLL4 mAb | Phase II (registration no. NCT02259582; w/Chemo; NSCLC; completed) | (160) |

| Enoticumab | REGN421 | Anti-DLL4 mAb | Phase I (registration no. NCT00871559; solid tumors; completed) | (161) | |

| MEDI0639 | Anti-DLL4 mAb | Phase I (registration no. NCT01577745; solid tumors; completed) | (162) | ||

| Brontictuzumab | OMP-52M51 | Anti-NOTCH1 mAb | Phase I (registration no. NCT01778439; solid tumors; completed) | (163) | |

| Tarextumab | OMP-59R5 | Anti-NOTCH2/3 mAb | Phase II (registration no. NCT01647828; w/Chemo; Panc; completed) | (164,165) | |

| 15D11 | Anti-JAG1 mAb | Preclinical study | (220) | ||

| ADC | Rovalpituzumab tesirine | Rova-T, SC16LD6.5 | Anti-DLL3 ADC | Phase III (registration no. NCT03033511; SCLC; recruiting); Phase III (registration no. NCT03061812; DLL3-high SCLC; active NR) | (170-172) |

| PF-06650808 | Anti-NOTCH3 ADC | Phase I (registration no. NCT02129205; solid tumors; terminated) | (173) | ||

| bsAb | AMG 757 | Anti-DLL3/CD3 bsAb | Phase I (registration no. NCT03319940; SCLC; recruiting) | (174) | |

| ABT-165 | Anti-DLL4/VEGF bsAb | Phase II (registration no. NCT03368859; w/Chemo; CRC; recruiting) | (175) | ||

| Navicixizumab | OMP-305B83 | Anti-DLL4/VEGF bsAb | Phase I (registration no. NCT02298387; solid tumors; completed) | (176) | |

| CT16 | Anti-NOTCH2/3/EGFR bsAb | Preclinical study | (177) | ||

| PTG12 | Anti-NOTCH2/3/EGFR bsAb | Preclinical study | (178) | ||

| CAR-Ts | AMG 119 | DLL3-binding CAR-Ts | Phase I (registration no. NCT03392064; SCLC; active NR) | (179) | |

| Others | ZLDI-8 | ADAM17 inhibitor | Preclinical study | (221) | |

| CB-103 | NICD PPI inhibitor | Phase I/II (registration no. NCT03422679; cancer; recruiting) | (222) | ||

| SAHM1 | NICD PPI inhibitor | Preclinical study | (223) |

ACC, adenoid cystic carcinoma; Active NR, active, not recruiting; ADC, antibody-drug conjugate; bsAb, bispecific antibody or biologic; CAR-Ts, chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells; CRC, colorectal cancer; GSI, γ-secretase inhibitor; mAb, monoclonal antibody; NICD, Notch intracellular domain; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; Panc, pancreatic cancer; PPI, protein-protein interaction; PSEN1, presenilin-1; SCLC, small-cell lung cancer; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; w/, with; GoF, gain-of-function; DLL, delta-like canonical Notch ligand; JAG, jagged canonical Notch ligand; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ADAM17, disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein.

γ-Secretase inhibitors, such as AL101 (150), crenigacestat (151), MRK-560 (152), nirogacestat (153,154) and RO4929097 (155,156), are investigational Notch pathway inhibitors. AL101, crenigacestat, nirogacestat and RO4929097 were tolerated in phase I clinical trials with common adverse effects, such as diarrhea, fatigue, nausea and vomiting (150,151,153,155), whereas MRK-560, which selectively targets presenilin-1-containing γ-secretase complexes, is a next-generation γ-secretase inhibitor with decreased gastrointestinal toxicities (152). Multiple phase II clinical trials of RO4929097 (registration nos. NCT01116687, NCT01120275, NCT01175343 and NCT01232829) failed, had insufficient results or were terminated because of limited anti-tumor activity, partially driven by cytochrome P450 3A4-mediated drug metabolism (155,156). Combination therapy is a rational strategy to enhance the clinical benefits of γ-secretase inhibitors, because bypassing the activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) (157,158) and the RAS-MEK-ERK (159), PI3K-AKT (80) and Hedgehog-GLI (84) signaling cascades elicits resistance to γ-secretase inhibitors. Prescription to strong responders is another rational strategy to enhance the clinical benefits of γ-secretase inhibitors. A phase III clinical trial of nirogacestat for desmoid tumor patients (registration no. NCT03785964) is in progress based on objective response rates (ORRs) of ~70 and ~30% in phase I (registration no. NCT00878189) and phase II (registration no. NCT01981551) clinical trials, respectively (153,154).

Antibody drugs that can selectively block Notch ligands or receptors have been predicted to be an optimal choice for cancer therapy compared with γ-secretase inhibitors for pan-Notch signaling blockade. Anti-DLL4 mAbs (demcizumab, enoticumab and MEDI0639) (160-162), an anti-NOTCH1 mAb (brontictuzumab) (163) and an anti-NOTCH2/3 mAb (tarextumab) (164,165) have been investigated in phase I clinical trials for the treatment of patients with cancer (Table I), and were relatively well tolerated with common adverse effects, including diarrhea, fatigue and nausea. However, because DLL4-NOTCH signaling in endothelial cells (127,128) and DLL4-NOTCH3 signaling in pericytes (5) mediate cardiovascular homeostasis, anti-DLL4 and anti-NOTCH2/3 mAbs elicit cardiovascular toxicities, such as hypertension, acute myocardial infarction, left ventricular dysfunction and peripheral edema. The ORRs of monotherapy with anti-DLL4, anti-NOTCH1 and anti-NOTCH2/3 mAbs were <5% (160-165).

ADC, bsAb and CAR-T technologies (166-169) have been applied to enhance the benefits of therapeutic mAbs in patients with cancer. Notch-related investigational biologics include ADCs targeting DLL3 [rovalpituzumab tesirine (Rova-T)] (170-172) and NOTCH3 (PF-06650808) (173); bsAbs targeting DLL3/CD3 (AMG 757) (174), DLL4/VEGF (ABT-165 and navicixizumab) (175,176) and NOTCH2/3/EGFR (CT16 and PTG12) (177,178); and CAR-Ts targeting DLL3 (AMG 119) (179) (Table I). A phase I clinical trial of the anti-DLL4/VEGF bsAb navicixizumab in 66 patients with solid tumors (registration no. NCT02298387) showed four partial responses (PRs) in the entire cohort and three PRs among 11 patients with ovarian cancer, accompanied by adverse events such as systemic hypertension (58%) and pulmonary hypertension (18%) (176); in addition, a phase I clinical trial of the anti-NOTCH3 ADC PF-06650808 in patients with breast cancer and other solid tumors (registration no. NCT02129205) revealed a manageable safety profile and three PRs among 40 participants (173). By contrast, a phase I clinical trial of the anti-DLL3 ADC Rova-T in 74 patients with SCLC and eight patients with large-cell neuroendocrine tumors (registration no. NCT01901653) demonstrated ORRs of 17% (11/65) in the entire cohort and 38% (10/26) among DLL3-high patients, with adverse events such as thrombocytopenia and pleural effusion (171). Preliminary analysis of a phase II clinical trial of Rova-T in patients with SCLC (registration no. NCT02674568) showed an ORR of 21.6% (58/266), with manageable toxicities (172). Currently, phase III clinical trials of Rova-T for the treatment of SCLC patients (registration nos. NCT03033511 and NCT03061812) are ongoing. Regarding DLL3, phase I clinical trials of the anti-DLL3/CD3 bsAb AMG 757 (registration no. NCT03319940) and DLL3-targeting CAR-Ts AMG 119 (registration no. NCT03392064) are also in progress. Compared with DLL4 and NOTCH3, DLL3 is an ideal target for ADCs, bsAbs and CAR-Ts, because DLL3 is upregulated in SCLC and other neuroendocrine tumors, repressing Notch signaling and reciprocally upregulating REST to maintain the neuroendocrine phenotype (41,170,180).

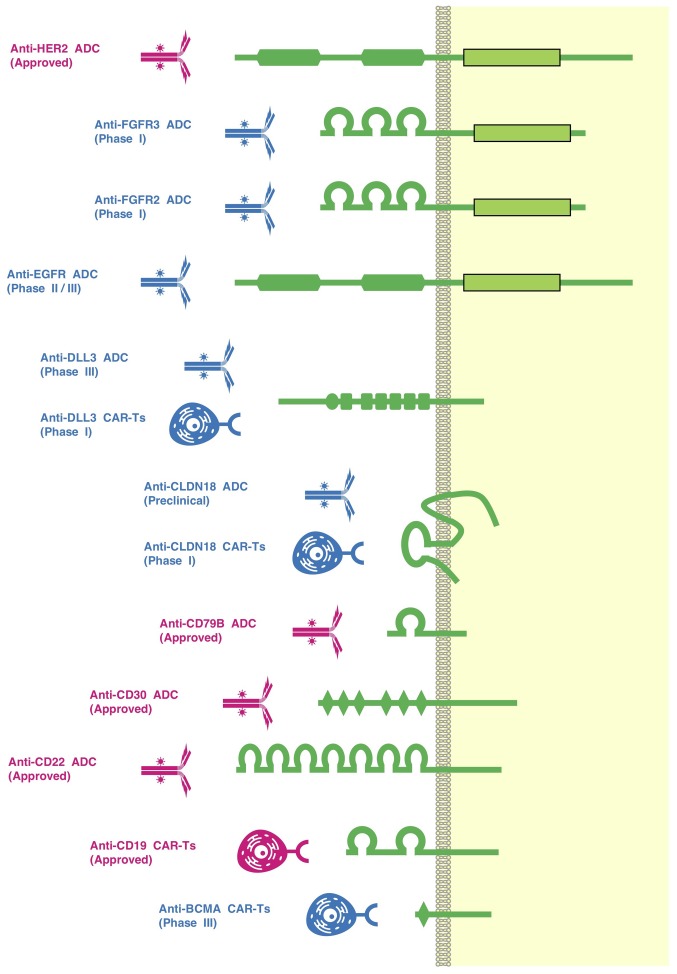

6. Perspectives on Notch-targeted precision oncology

ADCs or CAR-Ts targeting RTKs (Table II) and other trans-membrane or GPI-anchored proteins (Table III) are popular topics in clinical oncology. Anti-CD19 CAR-Ts (axicabtagene ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel) (181,182), an anti-CD22 ADC (inotuzumab ozogamicin) (183), an anti-CD30 ADC (brentuximab vedotin) (184) and an anti-CD79B ADC (polatuzumab vedotin) (185) have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of patients with hematological malignancies, and an anti-HER2 ADC (trastuzumab emtansine) (186) has been approved for the treatment of patients with breast cancer (Fig. 4). Trastuzumab-based ADCs with distinct linkers and payloads (trastuzumab deruxtecan and trastuzumab duocarmazine) (187,188); other ADCs targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (189), folate receptor-α (190), NECTIN4 (191) and tumor-associated calcium signal transducer 2 (192); and CAR-Ts targeting tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 17 (193) are also in phase III clinical trials. An anti-CD205 ADC that targets mesenchymal tumor cells and CAFs (194) and anti-Claudin-18.2 CAR-Ts that showed an ORR of 36% (4/11) in patients with gastric or pancreatic cancer (195) are cutting-edge biologics in early-stage clinical trials. ADCs and CAR-Ts (Tables II and III) could alter the therapeutic scheme for refractory solid tumors, especially peritoneal dissemination from diffuse-type gastric cancer, ovarian cancer and pancreatic cancer.

Table II.

ADCs and CAR-Ts targeting RTKs.

| Target | Type | Drug name | Alias | Stage of drug development | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALK | ADC | CDX-0125-TEI | Preclinical study (Rodent) | (224) | |

| AXL | ADC | Enapotamab vedotin | AXL-107-MMAE | Phase I/II (registration no. NCT02988817; solid tumors; Recruiting) | (225) |

| DDR1 | ADC | T4H11-DM4 | Preclinical study (Rodent) | (226) | |

| EGFR | ADC | Depatuxizumab mafodotin | ABT-414 | Phase II/III (registration no. NCT02573324; EGFR+ Glio; active NR) | (189) |

| FGFR2 | ADC | BAY 1179470 | Phase I (registration no. NCT02368951; solid tumors; completed in 2016) | (227) | |

| FGFR3 | ADC | LY3076226 | Phase I (registration no. NCT02529553; cancer; completed in 2018) | (228) | |

| FLT3 | ADC | ASP1235 | AGS62P1 | Phase I (registration no. NCT02864290; AML; recruiting) | (229) |

| HER2 | ADC | Trastuzumab emtansine | T-DM1 | FDA approval (HER2+ Breast) | (186) |

| HER2 | ADC | Trastuzumab deruxtecan | DS-8201a | Phase III (registration no. NCT03529110; HER2+ Breast; recruiting) | (187) |

| HER2 | ADC | Trastuzumab duocarmazine | SYD985 | Phase III (registration no. NCT03262935; HER2+ Breast; recruiting) | (188) |

| HER2 | ADC | MI130004 | Preclinical study (rodent; long-lasting anti-tumor effects) | (230) | |

| HER3 | ADC | U3-1402 | Phase I/II (registration no. NCT02980341; HER3+ Breast; recruiting) | (231) | |

| KIT | ADC | LOP628 | Phase I (registration no. NCT02221505; KIT+ Cancers; terminated in 2015) | (232) | |

| MET | ADC | Telisotuzumab vedotin | Teliso-V or ABBV-399 | Phase II (registration no. NCT03539536; MET+ NSCLC; recruiting) | (233) |

| PTK7 | ADC | Cofetuzumab pelidotin | PF-06647020 | Phase I (registration no. NCT02222922; solid tumors; active NR) | (234) |

| RET | ADC | Y078-DM1 | Preclinical study (rodent & primate; on-target neuropathy) | (235) | |

| RON | ADC | H-Zt/g4-MMAE | Preclinical study (rodent & primate) | (236) | |

| ROR1 | CAR-Ts | ROR1 CAR-Ts | Preclinical study (rodent & primate) | (237) |

Active NR, active, not recruiting; ADC, antibody-drug conjugate; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; Breast, breast cancer; CAR-Ts, chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells; EGFR+, epidermal growth factor receptor-amplified; Glio, glioblastoma or gliosarcoma; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; ALK, ALK tyrosine kinase receptor; AXL, tyrosine-protein kinase receptor UFO; DDR1, epithelial discoidin domain-containing receptor 1; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; FLT3, receptor-type tyrosine-protein kinase FLT3; KIT, mast/stem cell growth factor receptor Kit; PTK7, inactive tyrosine-protein kinase 7; RET, proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase receptor Ret; RON, macrophage-stimulating protein receptor; ROR1, inactive tyrosine-protein kinase transmembrane receptor ROR1.

Table III.

ADCs and CAR-Ts targeting transmembrane or GPI-anchored proteins other than DLL3, NOTCH3 and RTKs.

| Target | Type | Drug name | Alias | Stage of drug development | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCMA | ADC | GSK2857916 | Phase II (registration no. NCT03525678; multiple myeloma; active NR) | (238) | |

| BCMA | CAR-Ts | Bb2121 | Phase III (registration no. NCT03651128; multiple myeloma; recruiting) | (193) | |

| CD19 | CAR-Ts | Axicabtagene ciloleucel | KTE-C19 | FDA approval (B-cell NHL) | (181) |

| CD19 | CAR-Ts | Tisagenlecleucel | CTL019 | FDA approval (B-cell ALL & NHL) | (182) |

| CD22 | ADC | Inotuzumab ozogamicin | CMC-544 | FDA approval (B-cell ALL) | (183) |

| CD30 | ADC | Brentuximab vedotin | SGN-35 | FDA approval (ALCL, HL, mycosis fungoides & PTCL) | (184) |

| CD33 | ADC | Gemtuzumab ozogamicin | CMA-676 | FDA approval (AML) and subsequent withdrawal | (239) |

| CD56 | ADC | Lorvotuzumab mertansine | IMGN901 | Phase II (registration no. NCT02452554; pediatric tumors; active NR) | (240) |

| CD79B | ADC | Polatuzumab vedotin | DCDS4501A | FDA approval (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma) | (185) |

| CD142 | ADC | Tisotumab vedotin | TF-ADC | Phase I/II (registration no. NCT02001623; solid tumors; completed in 2018) | (241) |

| CD205 | ADC | MEN1309 | OBT076 | Phase I (registration no. NCT03403725; solid tumors; recruiting) | (194) |

| CEACAM5 | ADC | Labetuzumab govitecan | IMMU-130 | Phase I/II (registration no. NCT01605318; colorectal cancer; completed in 2017) | (242) |

| CLDN18 | ADC | Anti-CLDN18.2 ADC | Preclinical study (rodent) | (243) | |

| CLDN18 | CAR-Ts | CAR-CLDN18.2 | Phase I (registration no. NCT03159819; Gas & Panc; recruiting) | (195) | |

| FOLR1 | ADC | Mirvetuximab soravtansine | IMGN853 | Phase III (registration no. NCT02631876; ovary; active NR) | (190) |

| GFRA1 | ADC | hu-6D3.v5-vcMMAE | Preclinical study (rodent & primate) | (244) | |

| GPNMB | ADC | Glembatumumab vedotin | CDX-011 | Phase II (registration no. NCT02302339; melanoma; terminated in 2018) | (245) |

| LGR5 | ADC | Anti-LGR5-mc-vc-PAB-MMAE | Preclinical study (rodent) | (246) | |

| LRRC15 | ADC | Samrotamab vedotin | ABBV-085 | Phase I (registration no. NCT02565758; solid tumors; completed in 2019) | (247) |

| LYPD3 | ADC | Lupartumab amadotin | BAY 1129980 | Phase I (registration no. NCT02134197; solid tumors; completed in 2018) | (248) |

| MSLN | ADC | Anetumab ravtansine | BAY 94-9343 | Phase II (registration no. NCT03023722; Panc; active NR) | (249) |

| NECTIN4 | ADC | Enfortumab vedotin | ASG-22ME | Phase III (registration no. NCT03474107; urothelial cancer; recruiting) | (191) |

| SLC34A2 | ADC | Lifastuzumab vedotin | DNIB0600A | Phase II (registration no. NCT01991210; ovarian cancer; completed in 2016) | (250) |

| SLC39A6 | ADC | Ladiratuzumab vedotin | SGN-LIV1A | Phase I/II (registration no. NCT03310957; TNBC; recruiting) | (251) |

| TROP2 | ADC | Sacituzumab govitecan | IMMU-132 | Phase III (registration no. NCT02574455; TNBC; recruiting) | (192) |

Active NR, active, not recruiting; ADC, antibody-drug conjugate; ALCL, anaplastic large cell lymphoma; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; Breast, breast cancer; CAR-Ts, chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells; CD142, Tissue factor; Gas, gastric cancer; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; MSLN, Mesothelin; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; Ovary, ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer; Panc, pancreatic cancer; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase, SCLC, small-cell lung cancer; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; BCMA, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 17; CEACAM5, carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5; CLDN18, Claudin 18.2; FOLR1, folate receptor-α; GFRA1, GDNF family receptor α1; GPNMB, transmembrane glycoprotein NMB; LGR5, leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor 5; LRRC15, leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 15; LYPD3, Ly6/PLAUR domain-containing protein 3; MSLN, mesothelin; SLC34A2, sodium-dependent phosphate transport protein 2B; SLC39A6, zinc transporter SIP6; TROP2, tumor-associated calcium signal transducer 2.

Figure 4.

ADCs and CAR-Ts. ADCs or CAR-Ts targeting BCMA, CD19, CD22, CD30, CD79B, CLDN18, DLL3, EGFR, FGFR2, FGFR3, HER2 and other transmembrane or GPI-anchored proteins have been developed as investigational drugs. Anti-CD19 CAR-Ts (axicabtagene ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel), an anti-CD22 ADC (inotuzumab ozogamicin), an anti-CD30 ADC (brentuximab vedotin), an anti-CD79B ADC (polatuzumab vedotin) and an anti-HER2 ADC (trastuzumab emtansine) have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of patients with cancer. A DLL3-targeting ADC, rovalpituzumab tesirine (Rova-T), is in phase III clinical trials for the treatment of patients with small-cell lung cancer (registration nos. NCT03033511 and NCT03061812). CLDN18, Claudin 18.2; ADC, antibody-drug conjugate; CAR-Ts, chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells; BCMA, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 17; DLL3, delta-like canonical Notch ligand 3; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor.

Repression of targeted antigens owing to the intratu-moral heterogeneity and omics reprogramming of tumor cells is a common mechanism of resistance to ADCs and CAR-Ts (98,196,197). Clinical trials of ADCs in patients with solid tumors have produced disappointing results, owing to a narrow therapeutic window and unavoidable therapeutic resistance or recurrence (Tables II and III). Recruitment of new patients for the randomized phase III clinical trial of Rova-T in patients with SCLC (registration no. NCT03061812) was halted owing to shorter overall survival times in the Rova-T treatment group than in the topotecan treatment group (12). LoF NOTCH1 mutations that decrease DLL3 dependence to suppress Notch signaling might lead to intrinsic resistance to Rova-T, whereas trans-differentiation from DLL3-high SCLC to DLL3-low SCLC or NSCLC might elicit acquired resistance to Rova-T. To enhance the clinical benefits of Rova-T in patients with SCLC, the mechanisms of resistance and biomarkers of responders should be elucidated by monitoring DLL3 expression, NOTCH mutations and tumor phenotypes before, during and after Rova-T therapy.

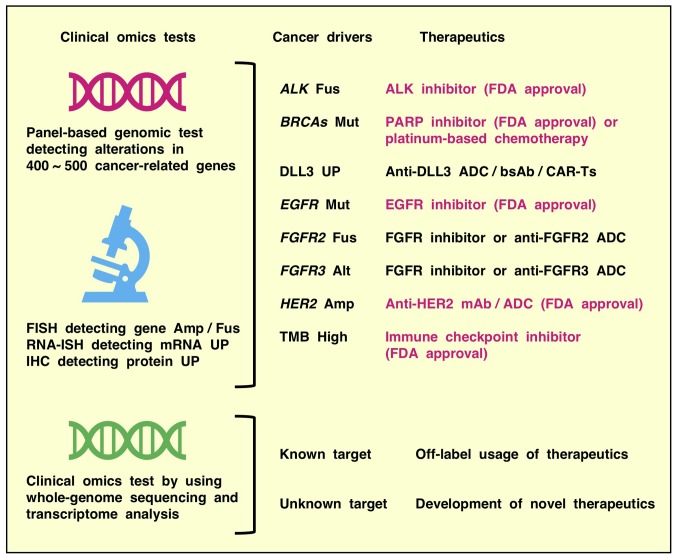

Clinical genomic tests using panel-based next-generation sequencing are utilized to match approved marketed drugs or investigational drugs to cancer patients in clinical trials in the era of precision oncology (198-200) (Fig. 5). These up-to-date genomic tests, which detect alterations in 400-500 cancer-related genes, but not out-of-date genomic tests, which detect many fewer cancer-related genes, can be reliably applied to diagnose tumor mutational burden-high cancers that predict responders to immune checkpoint inhibitors and non-responders to EGFR inhibitors (201-204). By contrast, because of their optimization for the major genetic alterations in various human cancer types, panel-based genomic tests cannot detect rare genetic alterations, promoter/enhancer mutations and epigenetic alterations that elicit aberrant activation of Notch and other oncogenic signaling pathways. Genomic tests that detect GoF mutations in the NOTCH1, NOTCH2, NOTCH3 and NOTCH4 genes, as well as mRNA in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical analyses that detect overexpression of Notch family receptors, would enhance the benefits of Notch pathway inhibitors, such as blocking mAbs and γ-secretase inhibitors, through successful positive selection of putative responders.

Figure 5.

Clinical omics tests for precision medicine. Panel-based genomic tests detecting mutations and other alterations in 400~500 cancer-related genes, FISH detecting gene Amp or Fus, RNA-ISH detecting mRNA upregulation and IHC detecting protein UP are utilized to match drugs to cancer patients in clinical oncology. Up-to-date panel-based genomic tests are reliably applied to detect biomarkers, such as cancer drivers and the TMB. By contrast, whole-genome sequencing and transcriptome analyses is applied to explore novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers predicting therapeutic optimization in translational oncology. ADC, antibody-drug conjugate; bsAb, bispecific antibody or biologic; CAR-Ts, chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells; mAb, monoclonal antibody; Mut, mutation; Alt, alteration; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; ALK, ALK tyrosine kinase receptor; BRCAs, BRCA DNA repair associated genes; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; Amp, amplification; Fus, fusion; RNA-ISH, RNA in situ hybridization; UP, upregulation; IHC, immunohistochemistry; PARP, poly [ADP ribose] polymerase; DLL3, delta-like canonical Notch ligand 3; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; TMB, tumor mutational burden.

Whole-genome sequencing, as well as wholeexome sequencing plus transcriptome analysis, is applied for the exploration of unknown cancer drivers, and the development of novel therapeutics for known but intractable targets with the aid of human intelligence, cognitive computing and artificial intelligence in basic and translational oncology (205-208). Moreover, artificial intelligence is also applied for computer-aided diagnostic approaches (209,210), such as chest computed tomography (211), dermoscopy (212), gastrointestinal endoscopy (213), mammography (214) and histopathological diagnosis (215-218). To avoid the lack of transparency associated with black box artificial intelligence based on deep learning technologies, the development of explainable artificial intelligence is necessary (219). Construction of a Notch-related knowledge base via human intelligence, explainable artificial intelligence, and cognitive computing based on natural language processing and text mining (Fig. 6) would promote the clinical application of Notch-targeted therapeutics in the era of omics-based precision medicine.

Figure 6.

Human intelligence, cognitive computing and explainable artificial intelligence for omics-based precision medicine. Artificial intelligence is applied for precision medicine with chest CT, GI endoscopy and other omics-based tests, including panel-based genomic tests, FISH, RNA-ISH, IHC and liquid biopsy. Human intelligence, explainable artificial intelligence and cognitive computing should be integrated to construct a Notch-related knowledge base for the optimization of Notch-targeted therapy, such as an anti-DLL3 ADC, small-molecule γ-secretase inhibitors and anti-DLL3 CAR-Ts. CT, computed tomography; GI, gastrointestinal; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; RNA-ISH, RNA in situ hybridization; IHC, immunohistochemistry; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; CAR-Ts, chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells; ADC, antibody-drug conjugate; DLL3, delta-like canonical Notch ligand 3.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported in part by a grant-in-aid from Masaru Katoh's Fund for the Knowledge-Base Project.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

MasukoK and MasaruK contributed to the conception of the study, performed the literature search and wrote the manuscript. MasukoK prepared the tables. MasaruK prepared the figures. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Guruharsha KG, Kankel MW, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. The Notch signalling system: Recent insights into the complexity of a conserved pathway. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:654–666. doi: 10.1038/nrg3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray SJ. Notch signalling in context. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:722–735. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meurette O, Mehlen P. Notch signaling in the tumor micro-environment. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:536–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siebel C, Lendahl U. Notch signaling in development, tissue homeostasis, and disease. Physiol Rev. 2017;97:1235–1294. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wimmer RA, Leopoldi A, Aichinger M, Wick N, Hantusch B, Novatchkova M, Taubenschmid J, Hämmerle M, Esk C, Bagley JA, et al. Human blood vessel organoids as a model of diabetic vasculopathy. Nature. 2019;565:505–510. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0858-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranganathan P, Weaver KL, Capobianco AJ. Notch signalling in solid tumours: A little bit of everything but not all the time. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:338–351. doi: 10.1038/nrc3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ntziachristos P, Lim JS, Sage J, Aifantis I. From fly wings to targeted cancer therapies: A centennial for notch signaling. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:318–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aster JC, Pear WS, Blacklow SC. The varied roles of Notch in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2017;12:245–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-052016-100127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowell CS, Radtke F. Notch as a tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:145–159. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espinoza I, Miele L. Notch inhibitors for cancer treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;139:95–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takebe N, Miele L, Harris PJ, Jeong W, Bando H, Kahn M, Yang SX, Ivy SP. Targeting Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt pathways in cancer stem cells: Clinical update. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12:445–464. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Owen DH, Giffin MJ, Bailis JM, Smit MD, Carbone DP, He K. DLL3: An emerging target in small cell lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:61. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0745-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Souza B, Miyamoto A, Weinmaster G. The many facets of Notch ligands. Oncogene. 2008;27:5148–5167. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kangsamaksin T, Murtomaki A, Kofler NM, Cuervo H, Chaudhri RA, Tattersall IW, Rosenstiel PE, Shawber C, Kitajewski J. NOTCH decoys that selectively block DLL/NOTCH or JAG/NOTCH disrupt angiogenesis by unique mechanisms to inhibit tumor growth. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:182–197. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakuda S, Haltiwanger RS. Deciphering the Fringe-mediated Notch code: Identification of activating and inhibiting sites allowing discrimination between ligands. Dev Cell. 2017;40:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nandagopal N, Santat LA, LeBon L, Sprinzak D, Bronner ME, Elowitz MB. Dynamic ligand discrimination in the Notch signaling pathway. Cell. 2018;172:869–880.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sjöqvist M, Andersson ER. Do as I say, Not(ch) as I do: Lateral control of cell fate. Dev Biol. 2019;447:58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lambrecht BN, Vanderkerken M, Hammad H. The emerging role of ADAM metalloproteinases in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:745–758. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang G, Zhou R, Zhou Q, Guo X, Yan C, Ke M, Lei J, Shi Y. Structural basis of Notch recognition by human γ-secretase. Nature. 2019;565:192–197. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0813-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kopan R, Ilagan MX. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: Unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell. 2009;137:216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vilimas T, Mascarenhas J, Palomero T, Mandal M, Buonamici S, Meng F, Thompson B, Spaulding C, Macaroun S, Alegre ML, et al. Targeting the NF-kappaB signaling pathway in Notch1-induced T-cell leukemia. Nat Med. 2007;13:70–77. doi: 10.1038/nm1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vermezovic J, Adamowicz M, Santarpia L, Rustighi A, Forcato M, Lucano C, Massimiliano L, Costanzo V, Bicciato S, Del Sal G, d'Adda di Fagagna F. Notch is a direct negative regulator of the DNA-damage response. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:417–424. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polacheck WJ, Kutys ML, Yang J, Eyckmans J, Wu Y, Vasavada H, Hirschi KK, Chen CS. A non-canonical Notch complex regulates adherens junctions and vascular barrier function. Nature. 2017;552:258–262. doi: 10.1038/nature24998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Neil J, Grim J, Strack P, Rao S, Tibbitts D, Winter C, Hardwick J, Welcker M, Meijerink JP, Pieters R, et al. FBW7 mutations in leukemic cells mediate NOTCH pathway activation and resistance to γ-secretase inhibitors. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1813–1824. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, Liu P, Inuzuka H, Wei W. Roles of F-box proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:233–247. doi: 10.1038/nrc3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shan H, Li X, Xiao X, Dai Y, Huang J, Song J, Liu M, Yang L, Lei H, Tong Y, et al. USP7 deubiquitinates and stabilizes NOTCH1 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2018;3:29. doi: 10.1038/s41392-018-0028-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.LaFoya B, Munroe JA, Pu X, Albig AR. Src kinase phosphorylates Notch1 to inhibit MAML binding. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15515. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33920-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramakrishnan G, Davaakhuu G, Chung WC, Zhu H, Rana A, Filipovic A, Green AR, Atfi A, Pannuti A, Miele L, Tzivion G. AKT and 143-3 regulate Notch4 nuclear localization. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8782. doi: 10.1038/srep08782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Y, Klauzinska M, Lake RJ, Lee JM, Santopietro S, Raafat A, Salomon D, Callahan R, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Trp53 regulates Notch 4 signaling through Mdm2. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1067–1076. doi: 10.1242/jcs.068965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGill MA, McGlade CJ. Mammalian Numb proteins promote Notch1 receptor ubiquitination and degradation of the Notch1 intracellular domain. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23196–23203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302827200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pettersson S, Sczaniecka M, McLaren L, Russell F, Gladstone K, Hupp T, Wallace M. Non-degradative ubiquitination of the Notch1 receptor by the E3 ligase MDM2 activates the Notch signalling pathway. Biochem J. 2013;450:523–536. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhardwaj A, Yang Y, Ueberheide B, Smith S. Whole proteome analysis of human tankyrase knockout cells reveals targets of tankyrase-mediated degradation. Nat Commun. 2017;8:2214. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02363-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaller MA, Logue H, Mukherjee S, Lindell DM, Coelho AL, Lincoln P, Carson WF, IV, Ito T, Cavassani KA, Chensue SW, et al. Delta-like 4 differentially regulates murine CD4 T cell expansion via BMI1. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.López-Arribillaga E, Rodilla V, Pellegrinet L, Guiu J, Iglesias M, Roman AC, Gutarra S, González S, Muñoz-Cánoves P, Fernández- Salguero P, et al. Bmi1 regulates murine intestinal stem cell proliferation and self-renewal downstream of Notch. Development. 2015;142:41–50. doi: 10.1242/dev.107714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ronchini C, Capobianco AJ. Induction of cyclin D1 transcription and CDK2 activity by Notch(ic): Implication for cell cycle disruption in transformation by Notch(ic) Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5925–5934. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.5925-5934.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanis KQ, Podtelezhnikov AA, Blackman SC, Hing J, Railkar RA, Lunceford J, Klappenbach JA, Wei B, Harman A, Camargo LM, et al. An accessible pharmacodynamic transcriptional biomarker for Notch target engagement. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99:370–380. doi: 10.1002/cpt.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.García-Peydró M, Fuentes P, Mosquera M, García-León MJ, Alcain J, Rodríguez A, García de Miguel P, Menéndez P, Weijer K, Spits H, et al. The NOTCH1/CD44 axis drives pathogenesis in a T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia model. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:2802–2818. doi: 10.1172/JCI92981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rangarajan A, Talora C, Okuyama R, Nicolas M, Mammucari C, Oh H, Aster JC, Krishna S, Metzger D, Chambon P, et al. Notch signaling is a direct determinant of keratinocyte growth arrest and entry into differentiation. EMBO J. 2001;20:3427–3436. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.13.3427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Procopio MG, Laszlo C, Al Labban D, Kim DE, Bordignon P, Jo SH, Goruppi S, Menietti E, Ostano P, Ala U, et al. Combined CSL and p53 downregulation promotes cancer-associated fibroblast activation. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:1193–1204. doi: 10.1038/ncb3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jarriault S, Le Bail O, Hirsinger E, Pourquié O, Logeat F, Strong CF, Brou C, Seidah NG, Isra l A. Delta-1 activation of Notch-1 signaling results in HES-1 transactivation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7423–7431. doi: 10.1128/MCB.18.12.7423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lim JS, Ibaseta A, Fischer MM, Cancilla B, O'Young G, Cristea S, Luca VC, Yang D, Jahchan NS, Hamard C, et al. Intratumoural heterogeneity generated by Notch signalling promotes small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2017;545:360–364. doi: 10.1038/nature22323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stoeck A, Lejnine S, Truong A, Pan L, Wang H, Zang C, Yuan J, Ware C, MacLean J, Garrett-Engele PW, et al. Discovery of biomarkers predictive of GSI response in triple-negative breast cancer and adenoid cystic carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1154–1167. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maier MM, Gessler M. Comparative analysis of the human and mouse Hey1 promoter: Hey genes are new Notch target genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;275:652–660. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weng AP, Millholland JM, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Arcangeli ML, Lau A, Wai C, Del Bianco C, Rodriguez CG, Sai H, Tobias J, et al. c-Myc is an important direct target of Notch1 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2096–2109. doi: 10.1101/gad.1450406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gekas C, D'Altri T, Aligué R, González J, Espinosa L, Bigas A. β-Catenin is required for T-cell leukemia initiation and MYC transcription downstream of Notch1. Leukemia. 2016;30:2002–2010. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tottone L, Zhdanovskaya N, Carmona Pestaña Á, Zampieri M, Simeoni F, Lazzari S, Ruocco V, Pelullo M, Caiafa P, Felli MP, et al. Histone modifications drive aberrant Notch3 expression/activity and growth in T-ALL. Front Oncol. 2019;9:198. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pirot P, van Grunsven LA, Marine JC, Huylebroeck D, Bellefroid EJ. Direct regulation of the Nrarp gene promoter by the Notch signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;322:526–534. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wakabayashi N, Skoko JJ, Chartoumpekis DV, Kimura S, Slocum SL, Noda K, Palliyaguru DL, Fujimuro M, Boley PA, Tanaka Y, et al. Notch-Nrf2 axis: Regulation of Nrf2 gene expression and cytoprotection by Notch signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:653–663. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01408-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.VanDussen KL, Carulli AJ, Keeley TM, Patel SR, Puthoff BJ, Magness ST, Tran IT, Maillard I, Siebel C, Kolterud Å, et al. Notch signaling modulates proliferation and differentiation of intestinal crypt base columnar stem cells. Development. 2012;139:488–497. doi: 10.1242/dev.070763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weber BN, Chi AW, Chavez A, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Yang Q, Shestova O, Bhandoola A. A critical role for TCF-1 in T-lineage specification and differentiation. Nature. 2011;476:63–68. doi: 10.1038/nature10279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Germar K, Dose M, Konstantinou T, Zhang J, Wang H, Lobry C, Arnett KL, Blacklow SC, Aifantis I, Aster JC, Gounari F. T-cell factor 1 is a gatekeeper for T-cell specification in response to Notch signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20060–20065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110230108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bray SJ, Gomez-Lamarca M. Notch after cleavage. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2018;51:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen B, Jiang L, Zhong ML, Li JF, Li BS, Peng LJ, Dai YT, Cui BW, Yan TQ, Zhang WN, et al. Identification of fusion genes and characterization of transcriptome features in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:373–378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717125115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanchez-Vega F, Mina M, Armenia J, Chatila WK, Luna A, La KC, Dimitriadoy S, Liu DL, Kantheti HS, Saghafinia S, et al. Oncogenic signaling pathways in The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell. 2018;173:321–337.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, Morris JP, IV, Silverman LB, Sanchez-Irizarry C, Blacklow SC, Look AT, Aster JC. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lympho-blastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306:269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palomero T, Barnes KC, Real PJ, Glade Bender JL, Sulis ML, Murty VV, Colovai AI, Balbin M, Ferrando AA. CUTLL1, a novel human T-cell lymphoma cell line with t(7;9) rearrangement, aberrant NOTCH1 activation and high sensitivity to gamma-secretase inhibitors. Leukemia. 2006;20:1279–1287. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bie De J, Demeyer S, Alberti-Servera L, Geerdens E, Segers H, Broux M, De Keersmaecker K, Michaux L, Vandenberghe P, Voet T, et al. Single-cell sequencing reveals the origin and the order of mutation acquisition in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2018;32:1358–1369. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0127-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Puente XS, Pinyol M, Quesada V, Conde L, Ordóñez GR, Villamor N, Escaramis G, Jares P, Beà S, González-Díaz M, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2011;475:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature10113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fabbri G, Dalla-Favera R. The molecular pathogenesis of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:145–162. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karube K, Enjuanes A, Dlouhy I, Jares P, Martin-Garcia D, Nadeu F, Ordóñez GR, Rovira J, Clot G, Royo C, et al. Integrating genomic alterations in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identifies new relevant pathways and potential therapeutic targets. Leukemia. 2018;32:675–684. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.González-Rincón J, Méndez M, Gómez S, García JF, Martín P, Bellas C, Pedrosa L, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Camacho FI, Quero C, et al. Unraveling transformation of follicular lymphoma to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0212813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kridel R, Meissner B, Rogic S, Boyle M, Telenius A, Woolcock B, Gunawardana J, Jenkins C, Cochrane C, Ben-Neriah S, et al. Whole transcriptome sequencing reveals recurrent NOTCH1 mutations in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2012;119:1963–1971. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-391474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robinson DR, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Wu YM, Shankar S, Cao X, Ateeq B, Asangani IA, Iyer M, Maher CA, Grasso CS, et al. Functionally recurrent rearrangements of the MAST kinase and Notch gene families in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2011;17:1646–1651. doi: 10.1038/nm.2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang K, Zhang Q, Li D, Ching K, Zhang C, Zheng X, Ozeck M, Shi S, Li X, Wang H, et al. PEST domain mutations in Notch receptors comprise an oncogenic driver segment in triple-negative breast cancer sensitive to a γ-secretase inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1487–1496. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robinson DR, Wu YM, Lonigro RJ, Vats P, Cobain E, Everett J, Cao X, Rabban E, Kumar-Sinha C, Raymond V, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of metastatic cancer. Nature. 2017;548:297–303. doi: 10.1038/nature23306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Westhoff B, Colaluca IN, D'Ario G, Donzelli M, Tosoni D, Volorio S, Pelosi G, Spaggiari L, Mazzarol G, Viale G, et al. Alterations of the Notch pathway in lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:22293–22298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907781106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang NJ, Sanborn Z, Arnett KL, Bayston LJ, Liao W, Proby CM, Leigh IM, Collisson EA, Gordon PB, Jakkula L, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in Notch receptors in cutaneous and lung squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17761–17766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114669108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Agrawal N, Frederick MJ, Pickering CR, Bettegowda C, Chang K, Li RJ, Fakhry C, Xie TX, Zhang J, Wang J, et al. Exome sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma reveals inactivating mutations in NOTCH1. Science. 2011;333:1154–1157. doi: 10.1126/science.1206923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stransky N, Egloff AM, Tward AD, Kostic AD, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Kryukov GV, Lawrence MS, Sougnez C, McKenna A, et al. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science. 2011;333:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1208130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Song Y, Li L, Ou Y, Gao Z, Li E, Li X, Zhang W, Wang J, Xu L, Zhou Y, et al. Identification of genomic alterations in oesophageal squamous cell cancer. Nature. 2014;509:91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature13176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martincorena I, Fowler JC, Wabik A, Lawson ARJ, Abascal F, Hall MWJ, Cagan A, Murai K, Mahbubani K, Stratton MR, et al. Somatic mutant clones colonize the human esophagus with age. Science. 2018;362:911–917. doi: 10.1126/science.aau3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.George J, Lim JS, Jang SJ, Cun Y, Ozretić L, Kong G, Leenders F, Lu X, Fernández-Cuesta L, Bosco G, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiles of small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2015;524:47–53. doi: 10.1038/nature14664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ali SA, Justilien V, Jamieson L, Murray NR, Fields AP. Protein kinase Cι drives a NOTCH3-dependent stem-like phenotype in mutant KRAS lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bhagat TD, Zou Y, Huang S, Park J, Palmer MB, Hu C, Li W, Shenoy N, Giricz O, Choudhary G, et al. Notch pathway is activated via genetic and epigenetic alterations and is a therapeutic target in clear cell renal cancer. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:837–846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.745208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van Groningen T, Akogul N, Westerhout EM, Chan A, Hasselt NE, Zwijnenburg DA, Broekmans M, Stroeken P, Haneveld F, Hooijer GKJ, et al. A NOTCH feed-forward loop drives reprogramming from adrenergic to mesenchymal state in neuroblastoma. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1530. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09470-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ban J, Bennani-Baiti IM, Kauer M, Schaefer KL, Poremba C, Jug G, Schwentner R, Smrzka O, Muehlbacher K, Aryee DN, Kovar H. EWS-FLI1 suppresses NOTCH-activated p53 in Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7100–7109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Augert A, Eastwood E, Ibrahim AH, Wu N, Grunblatt E, Basom R, Liggitt D, Eaton KD, Martins R, Poirier JT, et al. Targeting NOTCH activation in small cell lung cancer through LSD1 inhibition. Sci Signal. 2019;12 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aau2922. pii: eaau2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Song Y, Zhang Y, Jiang H, Zhu Y, Liu L, Feng W, Yang L, Wang Y, Li M. Activation of Notch3 promotes pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells proliferation via Hes1/p27Kip1 signaling pathway. FEBS Open Bio. 2015;5:656–660. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maraver A, Fernández-Marcos PJ, Herranz D, Muñoz-Martin M, Gomez-Lopez G, Cañamero M, Mulero F, Megías D, Sanchez-Carbayo M, Shen J, et al. Therapeutic effect of γ-secretase inhibition in KrasG12V-driven non-small cell lung carcinoma by derepression of DUSP1 and inhibition of ERK. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:222–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Palomero T, Sulis ML, Cortina M, Real PJ, Barnes K, Ciofani M, Caparros E, Buteau J, Brown K, Perkins SL, et al. Mutational loss of PTEN induces resistance to NOTCH1 inhibition in T-cell leukemia. Nat Med. 2007;13:1203–1210. doi: 10.1038/nm1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhou X, Smith AJ, Waterhouse A, Blin G, Malaguti M, Lin CY, Osorno R, Chambers I, Lowell S. Hes1 desynchronizes differentiation of pluripotent cells by modulating STAT3 activity. Stem Cells. 2013;31:1511–1122. doi: 10.1002/stem.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weng MT, Tsao PN, Lin HL, Tung CC, Change MC, Chang YT, Wong JM, Wei SC. Hes1 increases the invasion ability of colorectal cancer cells via the STAT3-MMP14 pathway. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jin S, Mutvei AP, Chivukula IV, Andersson ER, Ramsköld D, Sandberg R, Lee KL, Kronqvist P, Mamaeva V, Ostling P, et al. Non-canonical Notch signaling activates IL-6/JAK/STAT signaling in breast tumor cells and is controlled by p53 and IKKα/IKKβ. Oncogene. 2013;32:4892–4902. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schreck KC, Taylor P, Marchionni L, Gopalakrishnan V, Bar EE, Gaiano N, Eberhart CG. The Notch target Hes1 directly modulates Gli1 expression and Hedgehog signaling: A potential mechanism of therapeutic resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6060–6070. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bonyadi Rad E, Hammerlindl H, Wels C, Popper U, Ravindran Menon D, Breiteneder H, Kitzwoegerer M, Hafner C, Herlyn M, Bergler H, Schaider H. Notch4 signaling induces a mesenchymal-epithelial-like transition in melanoma cells to suppress malignant behaviors. Cancer Res. 2016;76:1690–1697. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang D, Xu J, Liu B, He X, Zhou L, Hu X, Qiao F, Zhang A, Xu X, Zhang H, et al. IL6 blockade potentiates the anti-tumor effects of γ-secretase inhibitors in Notch3-expressing breast cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:330–339. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hartman BH, Reh TA, Bermingham-McDonogh O. Notch signaling specifies prosensory domains via lateral induction in the developing mammalian inner ear. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15792–15797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002827107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Petrovic J, Formosa-Jordan P, Luna-Escalante JC, Abelló G, Ibañes M, Neves J, Giraldez F. Ligand-dependent Notch signaling strength orchestrates lateral induction and lateral inhibition in the developing inner ear. Development. 2014;141:2313–2324. doi: 10.1242/dev.108100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sun W, Gaykalova DA, Ochs MF, Mambo E, Arnaoutakis D, Liu Y, Loyo M, Agrawal N, Howard J, Li R, et al. Activation of the NOTCH pathway in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1091–1104. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Turley SJ, Cremasco V, Astarita JL. Immunological hallmarks of stromal cells in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:669–682. doi: 10.1038/nri3902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Valkenburg KC, de Groot AE, Pienta KJ. Targeting the tumour stroma to improve cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:366–381. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0007-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Östman A, Corvigno S. Microvascular mural cells in cancer. Trends Cancer. 2018;4:838–848. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lambrechts D, Wauters E, Boeckx B, Aibar S, Nittner D, Burton O, Bassez A, Decaluwé H, Pircher A, Van den Eynde K, et al. Phenotype molding of stromal cells in the lung tumor microenvironment. Nat Med. 2018;24:1277–1289. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bartoschek M, Oskolkov N, Bocci M, Lövrot J, Larsson C, Sommarin M, Madsen CD, Lindgren D, Pekar G, Karlsson G, et al. Spatially and functionally distinct subclasses of breast cancer-associated fibroblasts revealed by single cell RNA sequencing. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5150. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07582-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kalluri R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:582–598. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Altorki NK, Markowitz GJ, Gao D, Port JL, Saxena A, Stiles B, McGraw T, Mittal V. The lung microenvironment: An important regulator of tumour growth and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19:9–31. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0081-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang Z, Zöller M. Exosomes, metastases, and the miracle of cancer stem cell markers. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2019;38:259–295. doi: 10.1007/s10555-019-09793-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Katoh M. Canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling in cancer stem cells and their niches: Cellular heterogeneity, omics reprogramming, targeted therapy and tumor plasticity (Review) Int J Oncol. 2017;51:1357–1369. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2017.4129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dotto GP. Multifocal epithelial tumors and field cancerization: Stroma as a primary determinant. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1446–1453. doi: 10.1172/JCI72589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shibue T, Weinberg RA. EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: The mechanistic link and clinical implications. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:611–629. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: Integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331:1565–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, Duda DG, Jain RK. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: Opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:325–340. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Robbins J, Blondel BJ, Gallahan D, Callahan R. Mouse mammary tumor gene int-3: A member of the Notch gene family transforms mammary epithelial cells. J Virol. 1992;66:2594–2599. doi: 10.1128/JVI.66.4.2594-2599.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Peters G, Lee AE, Dickson C. Concerted activation of two potential proto-oncogenes in carcinomas induced by mouse mammary tumour virus. Nature. 1986;320:628–631. doi: 10.1038/320628a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shackleford GM, MacArthur CA, Kwan HC, Varmus HE. Mouse mammary tumor virus infection accelerates mammary carcinogenesis in Wnt-1 transgenic mice by insertional activation of int-2/Fgf-3 and hst/Fgf-4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:740–744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Katoh M. WNT and FGF gene clusters (review) Int J Oncol. 2002;21:1269–1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lowther W, Wiley K, Smith GH, Callahan R. A new common integration site, Int7, for the mouse mammary tumor virus in mouse mammary tumors identifies a gene whose product has furin-like and thrombospondin-like sequences. J Virol. 2005;79:10093–10096. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.10093-10096.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Theodorou V, Kimm MA, Boer M, Wessels L, Theelen W, Jonkers J, Hilkens J. MMTV insertional mutagenesis identifies genes, gene families and pathways involved in mammary cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:759–769. doi: 10.1038/ng2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhan T, Rindtorff N, Boutros M. Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36:1461–1473. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Morgan RG, Mortensson E, Williams AC. Targeting LGR5 in colorectal cancer: Therapeutic gold or too plastic. Br J Cancer. 2018;118:1410–1418. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0118-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Estrach S, Ambler CA, Lo Celso C, Hozumi K, Watt FM. Jagged 1 is a beta-catenin target gene required for ectopic hair follicle formation in adult epidermis. Development. 2006;133:4427–4438. doi: 10.1242/dev.02644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ma L, Wang Y, Hui Y, Du Y, Chen Z, Feng H, Zhang S, Li N, Song J, Fang Y, et al. WNT/NOTCH pathway is essential for the maintenance and expansion of human MGE progenitors. Stem Cell Reports. 2019;12:934–949. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Boulter L, Govaere O, Bird TG, Radulescu S, Ramachandran P, Pellicoro A, Ridgway RA, Seo SS, Spee B, Van Rooijen N, et al. Macrophage-derived Wnt opposes Notch signaling to specify hepatic progenitor cell fate in chronic liver disease. Nat Med. 2012;18:572–579. doi: 10.1038/nm.2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]