Abstract

Cardiac development arises from two sources of mesoderm progenitors, the first (FHF) and the second heart field (SHF). Mesp1 has been proposed to mark the most primitive multipotent cardiac progenitors common for both heart fields. Here, using clonal analysis of the earliest prospective cardiovascular progenitors in a temporally controlled manner during the early gastrulation, we found that Mesp1 progenitors consist of two temporally distinct pools of progenitors restricted to either the FHF or the SHF. FHF progenitors were unipotent, while SHF progenitors, were either uni- or bipotent. Microarray and single cell RT-PCR analysis of Mesp1 progenitors revealed the existence of molecularly distinct populations of Mesp1 progenitors, consistent with their lineage and regional contribution. Altogether, these results provide evidence that heart development arises from distinct populations of unipotent and bipotent cardiac progenitors that independently express Mesp1 at different time points during their specification, revealing that the regional segregation and lineage restriction of cardiac progenitors occurs very early during gastrulation.

Introduction

The mammalian heart is the first functional organ that forms during embryonic development and is composed of cardiomyocytes (CMs), endothelial cells (ECs), epicardial cells (EPDCs), and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) 1. Cardiac development arises from two sources of mesoderm progenitors, namely the first heart field (FHF) and the second heart field (SHF) 2, 3. Retrospective clonal analysis suggests the existence of a common progenitor for both heart fields, although the timing of the lineage segregation between these two progenitors remains unclear 3. Mesp1 is the earliest known marker of cardiac progenitors 4, 5. Overexpression of Mesp1 in ESCs 6–9 suggest that Mesp1 promotes the specification of the most primitive multipotent cardiac progenitors common for both heart fields 7. Lineage tracing using Mesp1-Cre, in which the recombinase Cre has been knocked-in under the regulatory region of Mesp1, showed also that almost all myocardial cells, including derivatives of the FHF and SHF, derive from Mesp1 expressing progenitors 4. However, lineage tracing using Mesp1-Cre and a single fluorescent reporter protein at the population level does not allow the assessment of whether FHF and SHF progenitors arise from a common progenitor or whether Mesp1 is expressed independently in distinct cardiac progenitors. To identify the developmental origin of organ regionalization and the timing of lineage segregation, it is essential to perform temporal clonal labelling in prospective progenitors 10.

One of the key questions in mammalian development is the timing with which the progenitor becomes specified to differentiate into their different lineages. During heart development, it has been initially proposed using DiI labelling or retroviral transduction of the primitive streak of chick embryos that cardiac and vascular lineage could be already prespecified at this early stage of gastrulation 11, 12. In contrast, subsequent genetic lineage tracing in vivo and clonal differentiation of cardiovascular progenitors in vitro supports the notion that, during mouse embryonic development, cardiovascular progenitors remain multipotent until the latter stages of cardiogenesis at the time where they begin to express transcription factors such as Nkx2-5 and Isl1 6, 7, 13–15. No study has assessed so far, at the early stage of gastrulation, the fate of prospective mouse cardiovascular progenitors into the different cardiovascular lineages using single cell marking in vivo.

Results

Dox inducible Mesp1 reporter and CRE mediated recombination

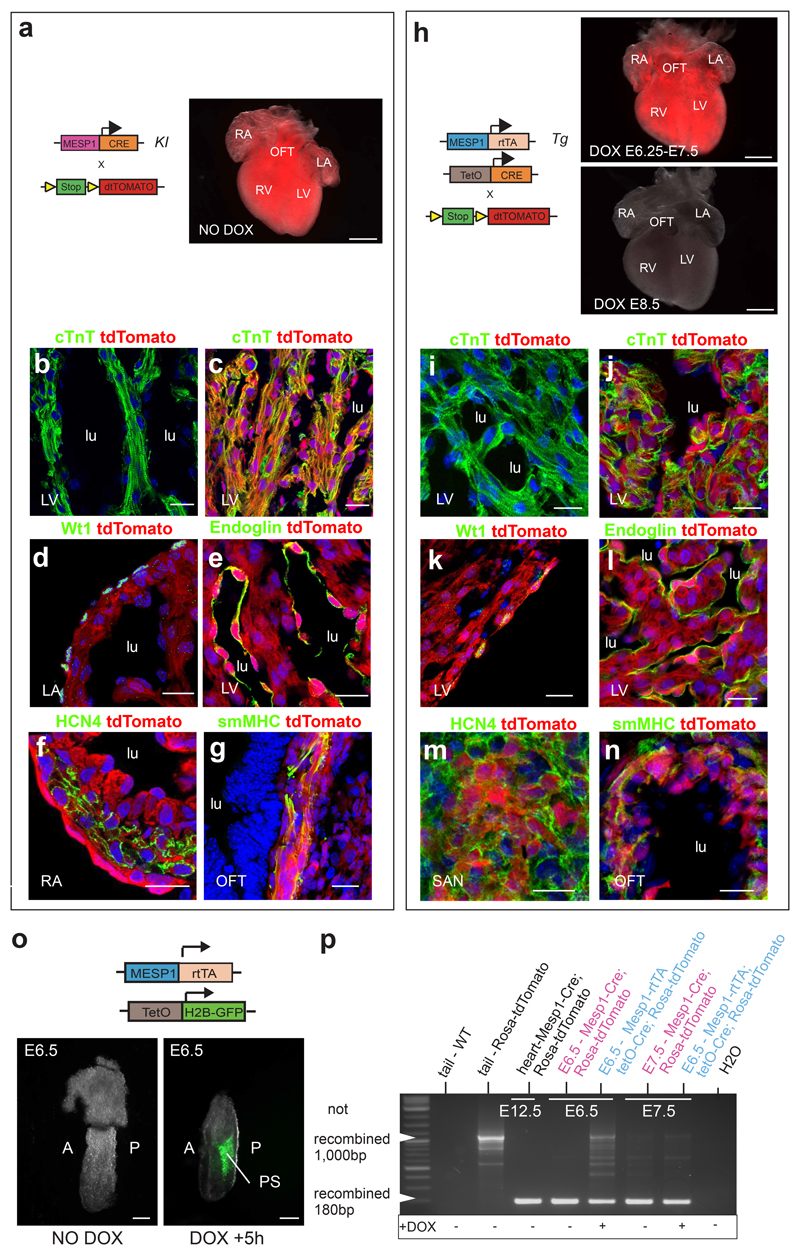

To assess the contribution of single Mesp1 expressing progenitors at different time points during embryonic development, we generated a tetracycline Mesp1-Tet-on inducible transgenic mice, in which the doxycycline dependent transactivator (Mesp1-rtTA) is expressed under the control of a fragment of the Mesp1 promoter expressed in cardiac progenitors during mouse embryonic development and ESC differentiation 6, 16 (Fig. 1). We identified 6 Mesp1-rtTA founders that produce embryos with faithful expression of the tdTomato in the heart when Dox was administrated to Mesp1-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Rosa-dtTomato embryos between E6.25 and E7.5, corresponding to the timing of endogenous Mesp1 expression 4, 17. The expression of the tdTomato was similar to that found in the Mesp1-Cre/Rosa-tdTomato embryos (Fig. 1a and h), indicating that the Mesp1-rtTA transgene targets the same cells as in Mesp1-Cre knock-in. Dox administration during the latter stage of cardiac development in Mesp1-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Rosa-dtTomato embryos after E8.0 did not induce dtTomato expression, consistent with the transient expression of Mesp1 during the early step of cardiovascular progenitor specification 4 (Fig. 1h). Finally, Dox administration to Mesp1-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Rosa-dtTomato embryos leads to the same labelling of all cardiovascular cell types of the FHF and SHF such as CMs, conduction cells, endocardial cells, EPDCs (Fig. 1a-n), with the exception of some unlabelled SMC in the SHF deriving from the neural crest 18 (Supplementary Fig. S1a-b).

Figure 1. Mesp1-rtTA transgenic mice faithfully recapitulates Mesp1 endogenous expression.

a. Macroscopic analysis of a Mesp1-Cre/Rosa-tdTomato embryo at E14.5. Scale bars: 500μm. b-c. Confocal analysis of Rosa-tdTomato (b) and Mesp1-Cre/Rosa-tdTomato heart sections (c) at E14.5 co-stained with anti-cardiac troponin T (cTnT) antibody. d-g. Confocal analysis of Mesp1-Cre/Rosa-tdTomato heart sections at E14.5 co-stained with epicardial (Wt1) (d), EC (endoglin) (e), pace-maker (Hcn4) (f) and SMC (smMHC) (g) markers. Scale bars: 20 μm. lu: lumen, V: ventricle, A: atria, OFT, outflow tract, IFT, inflow tract. h. Scheme of the genetic strategy used for the characterization of the Mesp1-rtTA transgenic mice. DOX administration leads to the activation of the Cre recombinase between E6.25 and E7.5 in Mesp1-rtTA/TetO-Cre/Rosa-tdTomato but no activation of the Cre recombinase was detected when DOX was administrated later (E8.5). i-j. Confocal analysis of Rosa-tdTomato (i) and Mesp1-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Rosa-tdTomato heart sections (j) at E14.5 co-stained with anti-cardiac troponin T (cTnT). k-n. Confocal analysis of Mesp1-rtTA/TetO-Cre/Rosa-tdTomato heart sections at E14.5 co-stained with epicardial (Wt1) (k), EC (endoglin) (l), pace-maker (Hcn4) (m) and SMC (smMHC) (n) markers. Scale bars: 20 μm. lu: lumen, V: ventricle, OFT, outflow tract, SAN, sino-atrial node. o. Temporal analysis of the activation of the Mesp1-rtTA transgene. While absence of Dox administration did not induce GFP expression in the embryos, GFP positive cells could be detected only 5h after Dox injection in the primitive streak (PS) and nascent mesoderm. A, anterior; P, posterior. p. Temporal analysis of the recombination of the Rosa-tdTomato locus investigated by PCR following Dox administration. The Rosa-tdTomato locus was recombined as soon as 6h following Dox administration in Mesp1-rtTA/TetO-Cre/Rosa-tdTomato embryos at E6.25 and E7.25, similarly as found with Mesp1-Cre/Rosa-tdTomato embryos at the same time points. Negative controls including WT tail and Rosa-tdTomato tail show PCR amplification corresponding to the unrecombined Rosa-tdTomato locus (around 1,000bp) and Mesp1-Cre/Rosa-tdTomato heart at E12.5 (positive control) show recombined Rosa-tdTomato locus (about 180bp).

To assess the temporal activation of the Mesp1-rtTA transgene upon Dox administration, we administrated Dox to Mesp1-rtTA/tet-O-H2B-GFP mice at E6.25, at the beginning of gastrulation, when Mesp1 begins to be expressed 4, 17. Already at 5 hours following Dox administration, H2B-GFP was detectable in the primitive streak (PS) and the nascent cardiac mesoderm (Fig. 1o), in a similar pattern to that previously reported for Mesp1-LacZ knockin mice 4, 17. Dox administration did not change the level or the localisation of Mesp1 (Supplementary Fig S1c-e). Cre and Mesp1 ISH 6h after Dox treatment at E6.25 revealed that at E6.25 Mesp1 and Cre were expressed at the same localisation in Mesp1-Cre knockin and Mesp1-rtTA/tetO-Cre embryos treated with Dox (Supplementary Fig S1f-h). PCR analysis showed that the Rosa-dtTomato locus was recombined, as early as 6h following Dox administration at E6.25 and E7.25, similar to Mesp1-Cre knockin embryos (Fig. 1p). All of these experiments indicate that Dox administration to Mesp1-rtTA/tetO-Cre embryos targets cardiovascular progenitors of both heart fields and faithfully recapitulates Mesp1-Cre knockin mice.

Two temporally distinct populations of Mesp1 progenitors contribute to the FHF and SHF development

To investigate the contribution of single Mesp1 expressing cells, we titrated the dose of Dox required to label Mesp1-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Rosa-Confetti hearts at clonal density, as defined by the dose of Dox allowing the recombination of a single fluorescent protein per heart. No leakiness in Mesp1-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Rosa-Confetti mice was observed. Administration of 0.575 μg/g of Dox was the lowest dose that could be used to induce the labelling of very few cardiac progenitors from E6.25 to E7.25, and no embryo showed fluorescently marked heart cells after 0.575 μg/g of Dox was administrated before E6.25 or after E8.5 (Supplementary Fig. S2a).

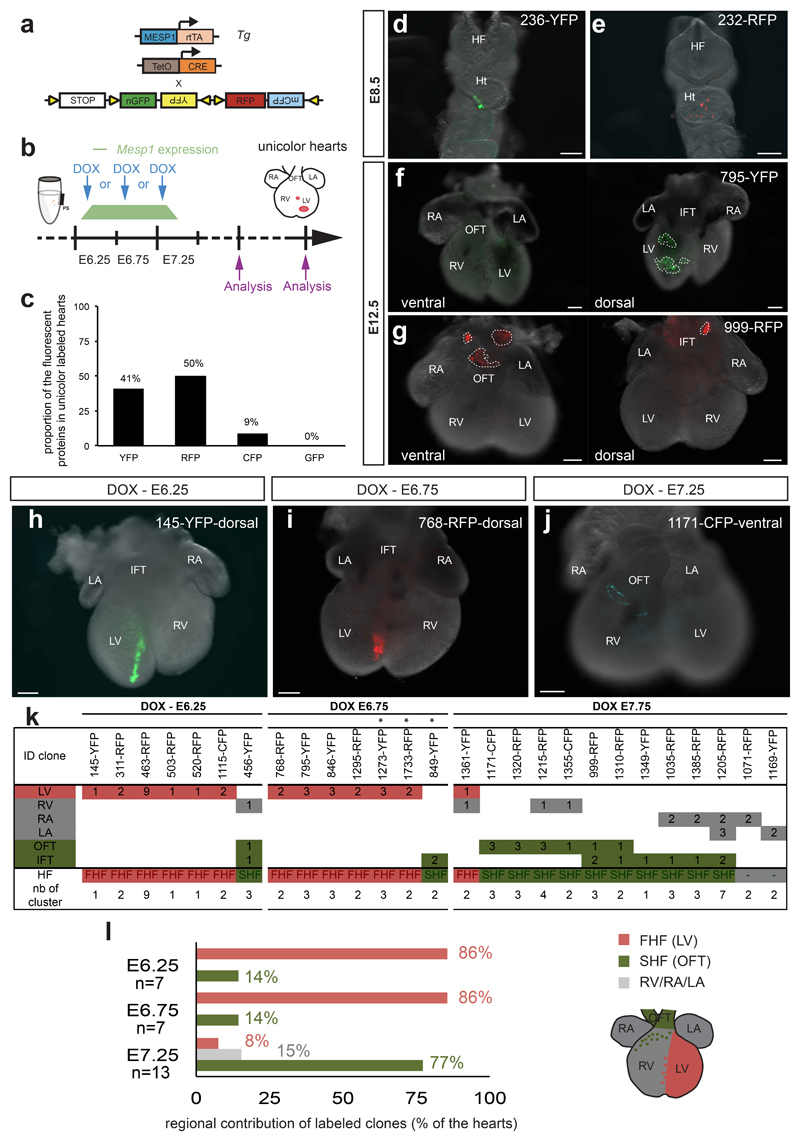

To assess whether a single Mesp1 derived cell could contribute to both the FHF and SHF and thereby mark a common progenitor of both heart fields, we used this lowest dose of Dox administrated between E6.25 and E7.25, and analysed the contribution of labelled clones to heart morphogenesis at E12.5 (Fig. 2a and b), when the segregation between the FHF and SHF derivatives is clearly established 3, 19. From the ensemble of labelled hearts, 22% (37 out of 161) were unicolour, expressing only one of the four fluorescent proteins, possibly arising from a single recombination event. However, in these unicolour hearts resulting from very low Cre activity, the frequency of different colours were not equal: YFP and RFP were over-represented as compared to the CFP and nuclear GFP (Fig. 2c), with the latter almost not expressed at all, as previously reported 20. Such unicolour-labelled hearts may arise from a single or multiple recombination events.

Figure 2. Two temporally distinct populations of Mesp1 progenitors contribute to the FHF and SHF development.

a. Scheme of the genetic strategy used for the clonal tracing of Mesp1 expressing progenitors with different fluorescent proteins to assess their regional contribution. b. Low dose of doxycycline (DOX) was injected between E6.25 and E7.25. Induced Mesp1-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Rosa-Confetti unicolour embryos were analyzed at E8.5 and E12.5. c. Proportion of the fluorescent proteins in unicolour-labelled hearts. (n=7 unicolour hearts at E8.5 and n=37 unicolour hearts at E12.5). d-e. Examples of Mesp1-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Rosa-Confetti unicolour labelled hearts at E8.5. f-g. Examples of Mesp1-rtTA/TetO-Cre/Rosa-Confetti unicolour labelled hearts at E12.5. Note that each patch is localized within either the FHF or the SHF but no unicolour patches that encompassed derivatives of the FHF and the SHF were observed. OFT, outflow tract; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; IFT, inflow tract. Scale bars: 200 μm. h-j. Examples of E12.5 unicolour hearts induced at E6.25 (H) and E6.75 (I) showing the labelling of FHF derived progenitors, while Dox administration at E7.25 shows preferential labelling of SHF progenitors (J). Scale bars: 200 μm. k. Graph depicting in all unicolour hearts the regional contribution of the labelled cells and the number of clusters of labelled cells per chamber according to the developmental time of Dox administration. * asterisks indicates that labelling was also detected in the epicardial layer. l. Quantification of the regional (FHF and SHF) contribution of patches of Mesp1 labelled cells in unicolour hearts shows the preferential labelling of the FHF (red) during Dox administration at the early time points (E6.25 and E6.75), while Dox administration in the late stage of cardiac progenitor specification (E7.25) shows the preferential labelling of Mesp1 progenitors that contribute to the SHF (green) derivatives. The number on the upper right in each panel refers to the ID of the labelled heart.

Unicolour hearts collected at E8.5 contained no more than 12 labelled cells, identifiable as a cluster of unicolour labelled cells in the heart tube (Fig. 2d, e), which were not always cohesive (Fig. 2e). These data support the idea that Mesp1 derived progenitors minimally expand from their specification in the primitive streak to the initial stage of heart tube development and may undergo a certain degree of cellular dispersion or fragmentation. Interestingly, by E12.5, most of the single colour hearts contained more than one cluster of labelled cells with a mean of about 3 clusters per heart (2.5 clusters +/- 0.37) suggesting that, during heart expansion, clones derived from Mesp1 derived progenitors may become separated into more than one fragment (Fig. 2f, g), so that the total number of labelled patches represents the combined result of multiple cell induction and clonal fragmentation (see Supplementary Theory).

To functionally categorize with high fidelity the relative contribution of Mesp1 expressing cells to the FHF and SHF lineages, we defined as FHF derivatives embryos in which left ventricle (LV) was labelled, and SHF derivatives hearts in which the outflow tract (OFT) and inflow tract (IFT) were labelled 3, 21. Out of 27 unicolour hearts analyzed at E12.5, all labelled cells were restricted to either the FHF or SHF derivatives, but no unicolour clones were found to be present in both heart fields (Fig. 2f-k). Only 2 out of 27 unicolour hearts could not be classified into FHF or SHF, as they presented clones located only in the atria or the right ventricle, which are believed to derive from both heart fields 3, 19 (Fig. 2k).

Since clonal dose of Dox did not induce heart labelling when administrated at E5.75 (Supplementary Fig. S2), we administrated a dose of Dox 40X higher to investigate whether Dox administration before E6.25 can target early multipotent Mesp1 expressing cells that would escape our clonal analysis. This early induction marked cells that were exclusively distributed in the FHF and never in both FHF and SHF (Supplementary Fig. S2), consistent with the results obtained by clonal analysis at E6.25, and ruling out the possibility that early Mesp1 expressing cells common for both heart fields were missed in our clonal tracing.

As all unicolour Mesp1 labelled progenitors appear to be already restricted to the FHF and SHF, we then investigated whether these two distinct pools of cardiac progenitors are specified at different time points during heart development. To address this question, we categorized the regional contribution of Mesp1 labelled cells (FHF and SHF) according to the time of Dox administration to induce the labelling of Mesp1 cardiac progenitors (Fig. 2h-k). Dox administration at the earliest time point of cardiac progenitor specification resulted in the preferential labelling of the LV (6 out of 7 hearts at E6.25 and 6 out of 7 hearts at E6.75) (Fig. 2h, i, k, l), consistent with the initial emergence of Mesp1 derived FHF progenitors. In contrast, Dox administration at a later time point (E7.25) induced a preferential labelling of SHF derivatives (10 out of 13 hearts) (Fig. 2j-l).

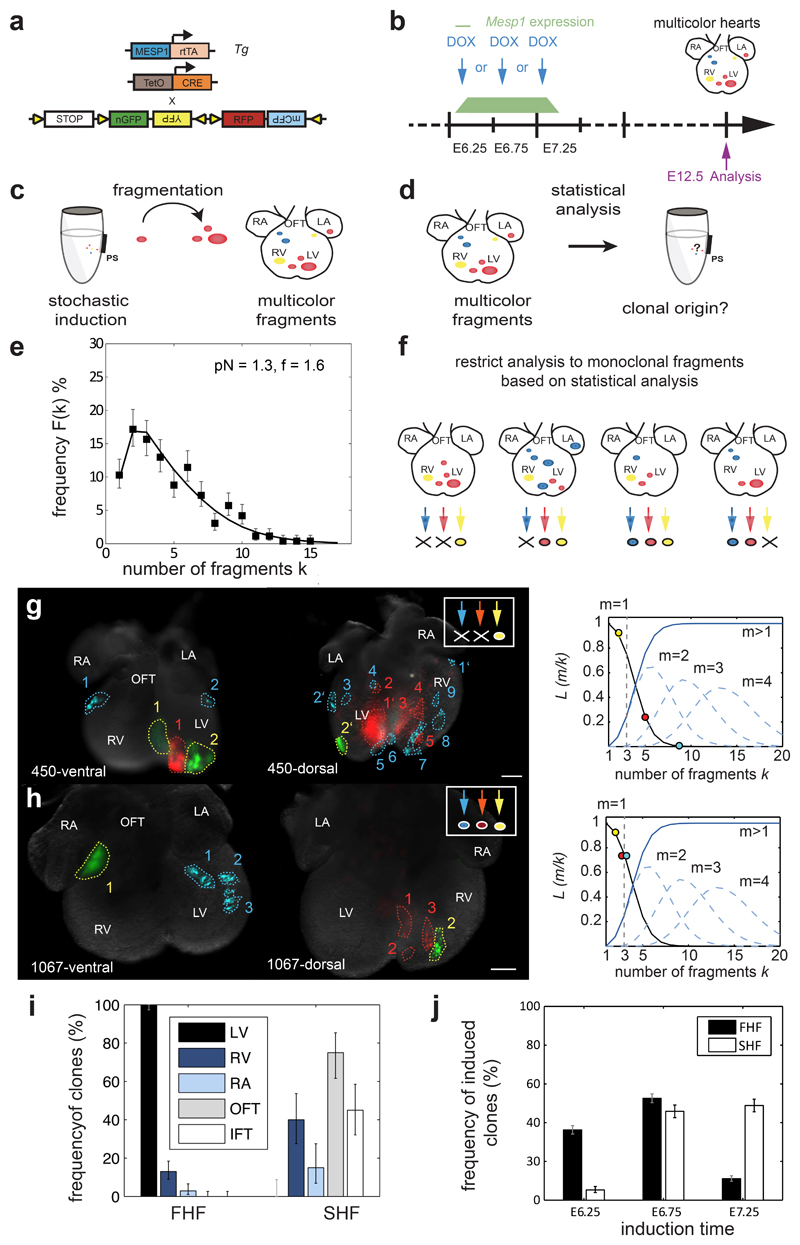

Bio-statistical modeling of the multicolour labelled hearts to infer clonal fragmentation and multiregional contribution of single Mesp1 expressing cells

Although this observation strongly suggests that Mesp1 progenitors are already restricted to the FHF or SHF, to define the degree of clonal fragmentation, the regional contribution of the distinct progenitor pools, and the timing of their specification, we turned to a more rigorous statistical analysis based on the full range of clonal data including multicolour hearts expressing more than one fluorescent protein (Fig. 3a-b). Although cell labelling and clonal fragmentation occur in a stochastic manner (Fig. 3c), the relative induction frequency, pN (defined as the probability of induction of an individual Mesp1 expressing cell times the total number of cardiac precursors), and the clonal fragmentation rate, f, could be inferred from the total ensemble of labelled hearts (161 labelled hearts translating to n=263 independent hearts by colour) using statistical inference (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Theory). By comparing the relative frequency of bicolour and tricolour hearts, we could infer the induction frequency, pN = 1.3 1±0.05, independent of the clone fragmentation rate. Then, by fitting the distribution of fragment numbers to a model based on stochastic fragmentation (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. S3a, b), we found a fragmentation rate of f = 1.6 ± 0.2.

Figure 3. Bio-statistical modeling of the the multicolour labelled hearts.

a. Scheme of the genetic strategy used for the clonal tracing of Mesp1 expressing progenitors with different fluorescent proteins b. Low dose of doxycycline (DOX) was injected at E6.25, E6.75 or E7.25. Multicolour induced hearts were analyzed at E12.5 and classified according to their regional contribution. c. Upon Dox administration, Mesp1 expressing cells are stochastically labelled in different colours. During early development, cells migrate and are rearranged such that growing clones may fragment into disconnected clusters. d. Statistical analysis of uni- and multicolour hearts was performed to infer induction frequency (pN) and the fragmentation rate (f). e. The stochastic nature of the lineage labelling and fragmentation results in a broad distribution of fragment numbers (squares). With an induction frequency, pN=1.3, and the fragmentation rate, f=1.6, the statistical model (solid line) is in excellent agreement with the experimental data. n=263 hearts by colour. f. Statistical analysis, allows to restrict the analysis to fragments that are likely to be monoclonal with a known error rate of 12% (Supplementary Fig. S5c and Theory). g-h. Examples of E12.5 multicolour hearts induced at E6.25 (g), or E7.25 (h). Scale bars: 200 μm. In the right corner is indicated which colour is considered as clonal, based on the statistical analysis. We compare the probability L(m = 1|k) that k fragments stem from a single clone (black line) with the probability L(m > 1|k) that these fragments stem from more than one cell (solid blue line). The latter is given by the sum contributions of clones with multiple cell origin (dashed blue lines). We consider k fragments as monoclonal, if L(m = 1|k) > L(m > 1|k), which leaves us with a threshold value of k = 3 (dashed grey line). The circles denote fragment numbers of the three fluorescent markers in examples shown. i. Regional contribution of FHF and SHF progenitors in monoclonal datasets (n=89), showing the contribution of the FHF and SHF progenitors to other cardiac regions. j. Temporal appearance of FHF and SHF progenitors inferred from all datasets at each induction time (n=263 hearts by colour). The number on the bottom right in each panel refers to the ID of the labelled heart. Error bars indicate one sigma Poisson confidence intervals.

With the known fragmentation rate f and induction frequency pN, we could then assess with a defined level of confidence which of the labelled hearts of any given colour are likely to derive from a single induced cell. In particular, we found that hearts with 3 fragments or less of a given colour were likely to be monoclonal (Fig. 3f, examples in Fig. 3g-h, Supplementary Table S1 and Theory). Following this classification, we identified 89 clones in our collection of multicolour hearts that were likely to be of monoclonal origin. Remarkably, we found that all of the clones that contained fragments in the FHF or SHF were restricted to one or the other heart field. None of these clones contributed to both heart fields, confirming that the FHF and SHF progenitors arise from distinct Mesp1 progenitors. By contrast, of the 69 clones that had fragments in the FHF, 15% also have fragments in the other heart compartments. Similarly, of the 20 clones that have fragments in the SHF, 55% have fragments in other heart compartments (Fig. 3i and Supplementary Table S1), demonstrating that once heart progenitors have been specified, they are likely to undergo clonal fragmentation that will contribute to the morphogenesis of distinct heart regions, consistent with the regions associated with the FHF and the SHF obtained by retrospective clonal analysis 3.

By assessing the proportion of FHF and SHF precursors that are labelled at each induction time, we found that most FHF derivatives were induced from E6.25 to E6.75 while most SHF derivatives were labelled between E6.75 and E7.25 (Fig. 3j). Finally, by computing pN and f for each heart field separately, we found that f = 1.4 ± 0.2 for the FHF while f = 1.9 ± 0.3 for the SHF showing that the latter undergoes a slightly higher rate of fragmentation (Supplementary Fig. S3c). Altogether, these results indicate that Mesp1 expressing cardiac progenitors consist of two temporally distinct populations that sequentially contribute to FHF and SHF development.

Mesp1 lineage is not exclusive to the heart but also marks other mesodermal lineages such as head muscles 22, 23. Retrospective clonal analysis has suggested a common origin for the head muscles and myocardium derived from the SHF 24. Interestingly, 11% of the embryos anlayzed showed co-labelling of the head muscles and the heart with the same colour (Supplementary Fig S4a-b). The labelling of the head muscles was preferentially observed at the late induction time (Supplementary Fig. S4c) and was associated with the labelling of SHF derivatives including the RV (Supplementary Fig. S4d). These results indicate that common progenitors for head muscles and heart myocardium encompass the pool of Mesp1 progenitors contributing to the SHF, consistent with previous retrospective clonal analysis 24.

Mesp1 progenitors consist of unipotent and bipotent progenitors

Until now, most studies assessing the differentiation potential of cardiac progenitor cells at the clonal level have been performed in vitro, and therefore may lack some important extrinsic cues that cardiac progenitors encounter during their in vivo specification. In vitro differentiation of single FACS isolated early cardiac progenitors (Mesp1-GFP or Brachyury-GFP/Flk1) from mouse embryo and during ESC differentiation, shows that these early cardiac progenitors differentiate into CMs, ECs, and SMCs, a fraction of which are multipotent at the clonal level 15. Likewise, later born Nkx2-5/cKit positive cardiac progenitors cells, which are preferentially enriched for FHF progenitors differentiate into CMs, SMCs or both 13, while Isl1/Flk1+ cells, which are preferentially enriched for SHF progenitors, give rise to colonies that differentiate into CMs, SMCs and ECs at the clonal level in vitro 14. Conflicting results have been obtained concerning the fate of cardiac progenitors in vivo during vertebrate development 25. Dye and retroviral based tracing during chick heart morphogenesis suggest that CMs and ECs arise from distinct pools of progenitors 11, 12, while lineage tracing in mouse embryos using Nkx2-5 and Isl1-Cre showed that these progenitors can differentiate into myocardium, smooth muscle, and endothelial cells at the population level 14, 26, 27, supporting the notion that during mouse development, cardiac progenitors are multipotent 25. However, the constitutive activity of the Cre expressed in the cardiac cells precludes assessment at the clonal level as to whether the different cell types (CMs, SMCs, and ECs) arise from multipotent or distinct unipotent progenitors.

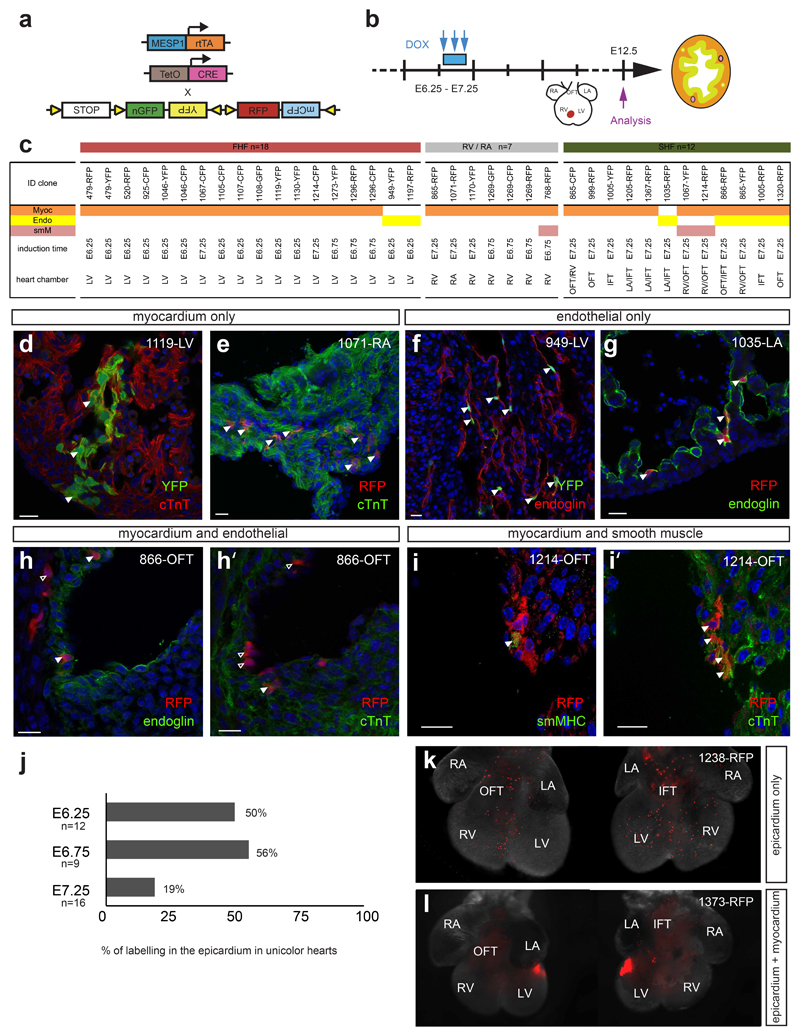

To assess the fate of single Mesp1 expressing progenitors during cardiovascular development in vivo, we assessed the co-expression of fluorescent proteins with specific markers of the different cardiovascular cell types in clonally induced Mesp1-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Rosa-Confetti embryos. We analyzed hearts from low Dox induced Mesp1-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Rosa-Confetti mice expressing fluorescently labelled patches at E12.5 and assessed the fate of the Mesp1 labelled cells on serial sections in a given unicolour patch (Fig. 4a-i). Surprisingly, all Mesp1 derived clones found in the LV and in the atria were unipotent, and differentiated into either CMs or ECs (Fig. 4c-g). The unipotent Mesp1 derived CM progenitors are likely to give rise to the recently identified HCN4+-unipotent FHF CM progenitors that are identified later during cardiac development 28, 29. While the clones of CMs in the ventricles remain relatively cohesive, the clones of ECs composing the endocardium were not cohesive and were intermingled with many unlabelled ECs (Supplementary Fig. S5). In contrast, while some of the Mesp1 progenitors of the SHF were also unipotent, differentiating into either CM or ECs, as previously reported during avian heart development 30, Mesp1 progenitors of the SHF can also be bipotent, especially in the outflow or inflow tract regions (85% of the bipotent clones), differentiating into CMs and ECs (Fig. 4c, h-h’), or CMs and SMCs (Fig. 4c, i-i’) at the clonal level.

Figure 4. Clonal analysis of lineage differentiation of Mesp1 derived progenitors in vivo.

a. Scheme of the genetic strategy used for the clonal tracing of Mesp1 expressing progenitors with different fluorescent proteins to assess their fate. b. Low dose of doxycycline (DOX) was injected to the pregnant female between E6.25 and E7.25 and induced Mesp1-rtTA/tetO-Cre/Rosa-Confetti embryos were analyzed at E12.5 for the expression of markers specific of the different cardiovascular lineages of the heart: CMs (cTnT), ECs (Endoglin) and SMCs (smMHC). c. Fate of the labelled cells in the different sectioned hearts is assessed by confocal analysis of co-immunostaining of the three markers in a given cluster. The localization of the patches within the different heart chambers and their FHF and SHF origin are indicated below. OFT, outflow tract; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium. d-i. Confocal analysis of serial sections of fluorescently labelled hearts co-stained for CM and EC markers show that clones in the LV differentiated only into either CM (d) or EC fate (f), and no FHF progenitors show clones positive for CM and EC markers. h-i. In contrast, bipotent clones presenting the ability to differentiate at the clonal level into either CMs (h) and ECs (h’) or CMs (i) and SMCs (i’) can be observed in the SHF. Arrowheads point to double marked cells. Scale bars: 20 μm. j. Percentage of labelling in the epicardium in unicolour hearts depending on the time of induction. k-l. Examples of E12.5 unicolour hearts showing labelling in the epicardial layer only (k) or in the epicardium and myocardium (l). Scale bars: 200 μm. The number on the upper right in each panel refers to the ID of the labelled heart.

Finally, we assessed the developmental origin and fate of the progenitors of the epicardium, the envelope that surrounds the heart, and that give rise to the cardiac fibroblasts and smooth muscle cell of the coronary arteries 31 The developmental origin of the epicardium in respect to the other cardiovascular progenitors remains unclear 32–34. Our Mesp1 clonal analysis revealed that 13 out of 37 unicolour induced hearts showed labelling in the epicardium (Fig. 4j-l), mostly arising following Dox administration at the earliest time of Mesp1 progenitor specification (Fig. 4j). Ten of the thirteen epicardium unicolour-labelled hearts (77%) showed only contribution to the epicardium (Fig. 4k), while 3 out of 13 hearts (23%) were also associated with labelled cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4l), suggesting that the majority of epicardial cells arise from an independent population of unipotent Mesp1 progenitors that will give rise to the epicardium lineage, while a small fraction of Mesp1 progenitors may be bipotent, giving rise to CMs and EPDCs.

The molecular heterogeneity of Mesp1 progenitors reflects their regional and lineage restricted contribution

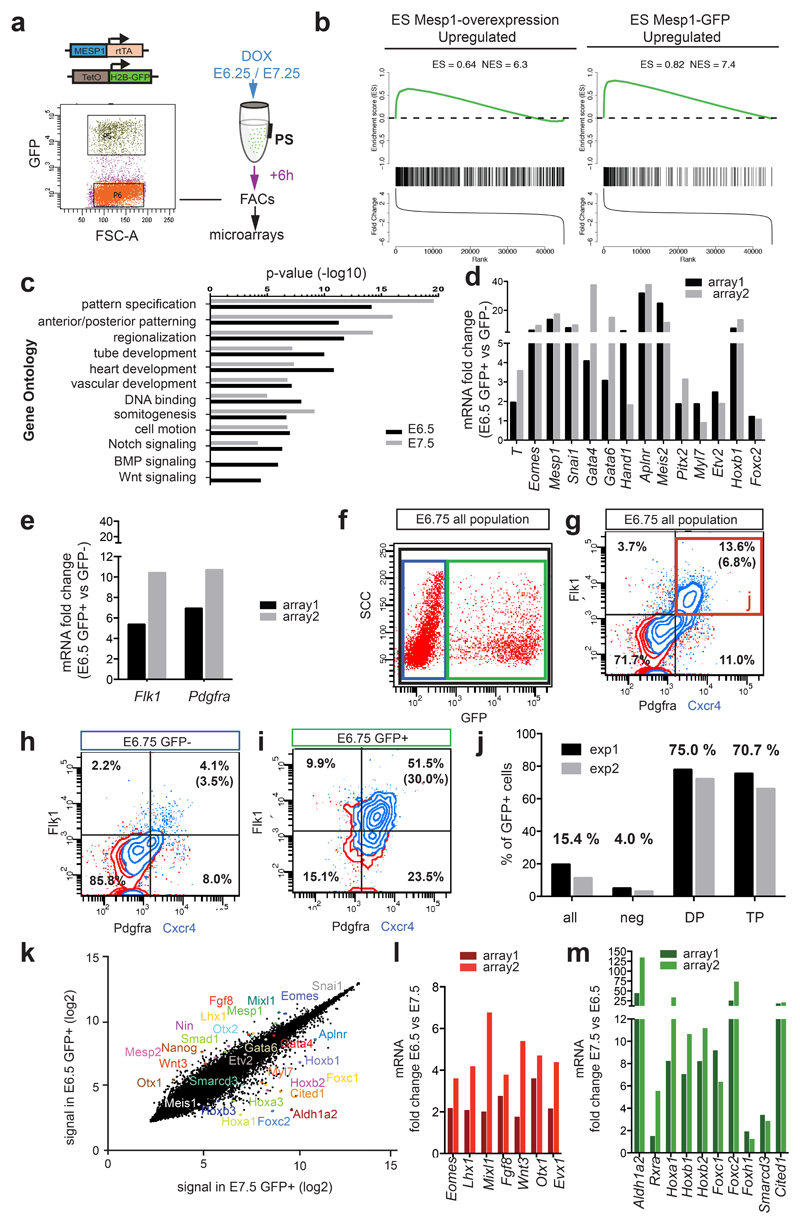

To gain further insights into the molecular mechanisms that control Mesp1 progenitor specification and lineage segregation during the early stage of cardiac mesoderm formation, we performed transcriptional profiling of Mesp1 expressing cells during the early and late stage of Mesp1 progenitors. To this end, we administrated Dox to Mesp1-rtTA/tet-O-H2B-GFP embryos at E6.25, or E7.25, isolated Mesp1 H2B-GFP positive and negative cells by FACS 6 hours later, and performed microarray analysis in two independent biological experiments (Fig. 5a). At E6.5, Mesp1 was the 6th most upregulated probe out of 46 000 probes, further demonstrating that our transgenic approach faithfully marked Mesp1 expressing cells. Interestingly, the comparison of these Mesp1 in vivo arrays with previous published arrays performed following Mesp1 overexpression or Mesp1-GFP positive cells during ESC differentiation 6, 7 (Fig. 5b) showed an important overlap between the genes differentially regulated in the Mesp1 GFP+ cells at E6.5 and the genes regulated by Mesp1 gain of function in ESC or associated with Mesp1-GFP at D3 of ESC differentiation (Table S2). Gene Ontology analysis revealed that Mesp1 progenitors at E6.5 are statistically highly enriched in genes regulating embryonic patterning and regionalization, heart and blood vessel morphogenesis, and transcriptional regulation (Fig. 5c). These genes comprised many key transcriptional factors known to act upstream of Mesp1 (eg: Eomes, T) 35, 36, downstream of Mesp1 or co-regulated with Mesp1 and regulating EMT (eg: Snail1) or controlling cardiovascular development (e.g: Gata4, Gata6, Hand1, Meis2) 6, 8, 9 (Fig. 5d and Table1). Many genes controlling key developmental signaling pathways, controlling cardiovascular development and lineage segregation, such as Wnt, Notch, BMP, TGF-b, FGF pathways that are regulated by Mesp1 in vitro 6–8, were also preferentially expressed in Mesp1 expressing cells in vivo (Table 1). Also Mesp1 expressing cells preferentially expressed genes associated with cell polarity and migration (e.g: Fn, Cdh11, N-cadh, Wnt5a, Vangl1, Ninein) (Table 1), consistent with the role of Mesp1 in regulating cardiac progenitor migration 4, 37. Flk1 and Pdgfra, two genes encoding cell surface markers previously shown to mark Mesp1 expressing cardiovascular progenitors during mouse and human ESC and iPSC differentiation 6, 15, were also upregulated in Mesp1-GFP in vivo (Fig. 5e-i), and the same combination of cell surface markers (Flk1, Pdgfra and CXCR4) could be used to greatly enrich early Mesp1 progenitors during embryonic development in vivo (Fig. 5j).

Figure 5. Molecular signature of early and late Mesp1 expressing cells in vivo.

a. Genetic and cell-sorting strategy used to assess the molecular signature of early and late Mesp1 expressing cells in vivo. Induced Mesp1-rtTA/TetO-H2B-GFP embryos at E6.25 or E7.25 were dissected 6h after Dox administration. GFP positive (GFP+) and negative (GFP-) cells were isolated by FACS and microarrays analyses were performed in two independent biological experiments. b. GSEA of Mesp1-GFP signature at E6.5 showing the distribution of genes upregulated by Mesp1 overexpression in ESC 6 (left) or the genes upregulated in ES Mesp1-GFP 7 (right). Genes are shown within the rank order list of all the microarray probe sets of E6.5 GFP+ cells. The highly significant enrichment score (ES) and normalized enrichment score (NES) are shown for each analysis. c. Gene ontology enrichment in Mesp1-GFP expressing cells at E6.5 (black) or E7.5 (grey). d. Expression of early mesodermal markers, Mesp1, EMT markers such as Snai1 and cardiac progenitor markers in E6.5 Mesp1 GFP+ cells as measured by microarrays. The fold change is presented over the GFP-population in duplicate samples. e. Surface marker expression in E6.5 Mesp1 GFP+ cells as measured by microarrays. f-i. FACs analysis showing GFP expression in E6.75 Mesp1-rtTA/TetO-H2B-GFP embryos 6 hours following Dox administration (f). FACs analysis of the combined expression of Cxcr4 (blue), Pdgfra and Flk1 expression in the all living cells (g), in GFP- (h) and Mesp1 GFP+ (i) populations, shows that the GFP+ population is enriched in triple positive (TP) cells. The percentage of cells in each quadrant is shown and the percentage of Pdgfra+/Flk1+/ Cxcr4+ cells is shown in brackets. j. FACs analysis of E6.75 Mesp1-rtTA/TetO-H2B-GFP embryonic cells showing that the Flk1+/Pdgfra+ double positive (DP) cells (red) and Flk1+/Pdgfra+/Cxcr4+ (TP) triple positive cells (blue) are highly enriched in Mesp1-GFP expressing cells. k. Comparison od Mesp1 expressing cells at E6.5 and E7.5. Dot plot representing the signal of each probe (merge of the two duplicates) showing that some key developmental genes are differentially expressed between E6.5 and E7.5. l-m. mRNAs expression at E6.5 and E7.5, as defined by microarray analysis. Genes upregulated at E6.5 (l) and at E7.5 (m).

Table 1. Up-regulated genes in Mesp1 GFP+ cells in vivo.

| Category | Up-regulated genes |

|---|---|

| 1. Transcription Factors/Chromatin Remodelling | Mixl1 (23 ;3), Meis2 (17 ;2), Mesp1 (15 ;2), Gata6 (12 ;2), Sp5 (11 ;2), Lhx1 (10 ;2), Hoxb1 (10 ;1.3), Snai1 (9 ;1.5), Peg3 (9 ;1.1), Klhl6 (9;3), T (8 ;1.4), Mesp2 (7 ;3), Gata4 (7 ;2), Tbx3 (7 ;0.8), Tbx6 (6 ;2), Nfatc1 (6 ;0.6), Pdlim5 (6 ;2), Irx5 (5 ;1.2), Evx1 (5 ;1.1), Sall3 (5 ;1.4), Otx1 (5 ;1.0), Zfx (5 ;0.3), Odz4 (5 ;2), Whsc1l1 (4 ;0.9), Six2 (4 ;2), Cdx1 (4 ;0.7), Id1 (3 ;0.4), Hand1 (3 ;0.6), Gabpa (3 ;1.4), Zfp423 (3 ;0.7), Msgn1 (3 ;0.8), Rreb1 (3 ;1.0), Pbx1 (3 ;1.5), Nfat5 (3 ;1.3), Psmd9 (3 ;1.1), Foxc1 (3 ;2), Rxrg (3 ;2), Eomes (3 ;2), Lef1 (3 ;1.4), Zeb2 (3 ;1.3), Phc2 (3 ;1.4), Glis1 (3 ;1.3), Irx3 (2 ;0.5), Hey1 (2 ;0.8), Etv2 (2 ;0.7), Hmga2 (2 ;0.9), Hdac2 (2 ;1.1), Sfpq (2 ;1.1), Ring1 (2 ;0.8), Zfp516 (2 ;1.5), Zbtb44 (2 ;0.6), Tcf4 (2 ;1.0), Nfil3 (2 ;1.3), Setdb1 (2 ;0.9), Chd7 (2 ;1.5), Terf2 (2 ;1.1), Eny2 (2 ;1.0), Pdlim4 (2 ;1.4), Cux1 (2 ;1.2), Klf9 (2 ;0.7), Arid3b (2 ;1.3), Cited2 (2 ;1.0), Wwtr1 (2 ;1.3), Kdm6b (2 ;2), Srf (2 ;2), Med13l (2 ;2), Pitx2 (2 ;2), Msx1 (2 ;2), Maml2 (2 ;2), Msx2 (2 ;2), Rbbp8 (2 ;2), Zic3 (2 ;2), Runx1t1 (1.0 ;2), Trps1 (1.3 ;2), Smarca2 (1.1 ;2), Plag1 (1.3 ;2), Tmpo (1.1 ;2), Tcf15 (1.1 ;2), Zfhx3 (0.5;2), Mll3 (1.3;2), Prrx2 (1.1;2), Trp53 (1.1;2), Xab2 (1.1 ;2), Csrnp2 (1.0 ;2), Plagl2 (0.9;2), Hoxb3 (0.9;2), Med1 (1.1 ;2), Men1 (0.6;2), Usf1 (1.0 ;2), Aff1 (0.7;2), Gfra2 (1.1 ;3), Rxra (1.0;3), Klf12 (0.6;3), Nasp (1.4;3), Runx2 (1.2 ;3), Meox1 (1.0 ;4) |

| 2. Signaling | |

| Notch |

Dll3 (14 ;2), Aph1b//Aph1c (6 ;2), Dlk1 (3 ;0.6), Jag1 (3 ;2), Hey1 (2 ;0.8), Notch1 (2 ;2), Maml2 (2 ;2), Dll1 (2 ;3), Lfng (2 ;3), Sel1l (1.0 ;2), Numb (0.8;2), |

| Wnt | Frzb (22 ;3), Wnt5a (9 ;2), Wnt3 (5 ;2), Wnt2b (4 ;2), Dact1 (4 ;2), Wls (3 ;1.1), Lef1 (3 ;1.4), Fzd1 (3;1.1), Wnt2 (3;2), Axin2 (3 ;1.1), Lrrfip2 (2;2), Ctnnbip1 (2 ;1.2), Wnt5b (2 ;0.9), Rspo3 (2;1.0), Tcf4 (2 ;1.0), Apcdd1 (1.7 ;0.9) |

| TGF-β |

Lefty2 (5 ;2), Tgfb1 (5 ;1.2), Dcp1a (2;1.2), Fstl1 (3 ;1.0), |

| FGF |

Fgf3 (11 ;1.2), Fgf10 (5 ;0.7), Fgf4 (3 ;2), Fgfrl1 (2 ;1.0), Spred1 (6 ;1.3) |

| BMP | Bmp7 (7 ;1.0), Smad1 (6 ;2), Bmper (3 ;1.2), Fst (3 ;2), Tdgf1 (3 ;5), Smad5 (2 ;1.0), Usp9x (2;0.9), Egr1 (2;1.1), Cer1 (0.3;2), Twsg1 (1.2;2) |

| Retinoic acid | Cyp26a1 (7; 1), Rarb (1;2), Rarg (2. 2), Rxra (2.2), Rxrg (3; 2), |

| Others | Aplnr (34;2), Dlc1 (12 ;2), Gas1 (10 ;1.4), Gna14 (9 ;1.3), Klhl6 (9 ;3), Prkd1 (7 ;2), Rasgrp3 (4 ;2), Rftn1 (4 ;1.4) ; Apln (3 ;0.9), Gpr50 (3 ;1.0), Braf (3 ;1.0), Igfbp4 (3 ;2), Ptch1 (3 ;2), Neo1 (3 ;4), Gna13 (2 ;1.0), Peli1 (2 ;1.3), Flt1 (2 ;1.3), Ppp2ca (2 ;2), Dusp9 (2 ;2), Srgap3 (1.7 ;1.1), Pcsk5 (1.3;2), Igsf10 (0.6;2), Arfrp1 (1.3;2), Rnf111 (1.2;2), Ptpra (1.3;3), Dab2 (0.4 ;3), Egfr (1.0 ;3), Litaf (2;1.0), Gnai1 (2;1.0), S1pr5 (3;1.2), Adcyap1r1 (4;2), Adra2b (2;2), Adora2b (2;1.3), Ptpn1 (2;2), Col4a3bp (2;1.1), Gjc1 (2;1.4), Tiparp (3;1.0), Nck1 (2;1.3), Arl4d (3;1.2), Hrasls (2;0.9), Rabl3 (2;1.2), Rab8b (7;2), Ralgps2 (2;1.2), Wsb1 (2;2), Asb4 (4;0.6), Lrrk1 (2;1.0), Map3k3 (2;1.2), Pth1r (2;2), Arf1 (4;0.6), Rhot1 (2;1.0), Tlk1 (2;0.9), Rala (2;0.6), Dab1 (2;0.9), Yaf2 (2;1.0), Rbm14 (2;0.9), Atl1 (3;1.1), Lpar6 (1.8 ;1.2) |

| 3. Migration/ Polarity / Guidance | Fn1 (18 ;3), Cdh11 (12 ;1.3), Pcdh7 (11 ;2), Adam19 (12 ;3), Pdgfra (9 ;1.4), Epha4 (8 ;1.2), Nin (8 ;2), Cxcr4 (8 ;2), Flk1 (7 ;1.2), Cdh2/Ncad (6 ;1.2), L1cam (6 ;2), Mmp14 (5 ;1.1), Cdh4 (5 ;1.3), Vangl1 (5 ;0.9), Prtg (5 ;1.4), Pcdh8 (5 ;4), Cdc42ep4 (4 ;0.8), Efna3 (4 ;1.2), Sema5a (4 ;0.8), Slit3 (4 ;1.3),Vcan (4 ;0.9), Dock11 (4 ;2), Itga5 (4 ;2), Mfap4 (3 ;1.8), Fat3 (3 ;1.5), Agtrap (3;1.0), Pcdh18 (3 ;1.2), Nrp2 (3 ;1.0), Pafah1b1 (3;0.6), Efnb3 (3;0.9), Enah (3 ;3), Plxna2 (3 ;3), Lin7c (3;3), Timp3 (2;2), Robo1 (2 ;1.2), Anks1 (2 ;0.9), Adam10 (2 ;0.6), Adamts9 (2 ;0.8), Hipk2 (2 ;1.0), Gpc3 (2 ;1.8), Efna1 (2 ;0.8), Has2 (2 ;0.6), Ngfr (2;1.0), Dpysl5 (2;1.0), Afg3l2 (2;1.3), Epha1 (2;1.4), Adra2b (2 ;2), Pdgfrb (2 ;2), Fbn2 (2;2), Col27a1 (3;2), Gad1 (2;1.1), Gls (2;1.3), Itgb1 (2;1.4), Ilk (2;1.1), Evl (2;1.0), Cyfip1 (2;1.2), Pcdh19 (2 ;3), Efnb1 (1.3 ;2), Prickle1 (1.4;2), Itga8 (1.4 ;2), Ryk (0.8;2), Rgnef (0.3 ;2), Itgav (3;1.1), |

| 4. Others | Ifitm1 (8 ;1.4), Ptprj (6 ;1.2), Rnd3 (6 ;1.0), Chst2 (6 ;2), Man1c1 (6 ;2), Cbln1 (6 ;3),. Anpep (6 ;3), Ccnd2 (5 ;0.8), Usp3 (5 ;1.4), Rimbp2 (5 ;2), Dclk1 (5 ;3), Cachd1 (4 ;1.4), Vldlr (4 ;1.2), Birc6 (4;0.8), Wwp1 (4;0.6), Atp11c (3 ;0.4), Phlda2 (3 ;1.0), Chst7 (3 ;1.1), Atg5 (3;1.5), Ppic (3 ;1.0), Hs3st3b1 (3 ;0.9), Cask (3;1.4), Wars2 (3;1.3), Man1a2 (3;1.1), Chek1 (2 ;0.4), Grsf1 (2 ;0.6), Olfm1 (2 ;1.1), Alox15 (2 ;1.1), Cdkn1c (2 ;1.3), Pmp22 (2 ;0.8), Leprel1 (2 ;0.9), Stxbp5 (2 ;1.4), Tes (2 ;1.1), Galnt7 (2 ;1.0), Slc11a2 (2;1.1), Ipmk (2;1.1), Egln3 (2 ;1.5), Phldb2 (2 ;2), Laptm4b (2 ;2), Kif3a (2 ;2), Trim72 (2 ;2), Sbsn (2 ;3), Flnb (1.3 ;2), Bace2 (1.9 ;3), Slc38a5 (1.6 ;1.1), Grrp1 (1.7 ;0.9), Vamp4 (1.7 ;1.7), Snta1 (1.3 ;2), Gys1 (0.7 ;3), Txnrd2 (1.0 ;3), Actc1 (1.1 ;3), Tnnc1 (0.8;10), |

Description of genes displaying a change in expression of >2 fold between Mesp1-GFP+ and Mesp1-GFP- cells at E6.5 and 7.5. (Fold change over GFP- cells at E6.5 ; Fold change over GFP- cells at E7.5) in 2 independent biological replicates. A gene ontology analysis was used to classify the up-regulated genes in the following categories : Transcription Factors/Chromatin Remodelling, Signaling pathways, Migration/Polarity/Guidance and Others (all biological function related to early embryo development that we can not put in any previous classes). In bold (overexpressed in Mesp1 GOF ESC) Underlined (overexpressed in Mesp1-GFP ESC).

Comparison between Mesp1-GFP positive cells at E6.5 and E7.5 revealed that Mesp1 progenitors share very similar expression profiles with several Mesp1 direct target genes, such that Gata4, Gata6, Aplnr were upregulated in Mesp1 positive cells at the early and late time points (Fig. 5k). Despite these similarities, early and late Mesp1 expressing present also important molecular differences including the differential expression of transcription factors and Hox related genes, previously identified in controlling pattern and regionalization in other tissues 38–40, suggesting that these genes may regulate the patterning of the PS (Table 1). Mixl1 41, Otx1 42, Evx1 43, Lhx1 44 were preferentially expressed in the early Mesp1 cells (Fig. 5k-l), while many genes known to be associated or controlling the morphogenesis of the SHF such as the Aldh1a2 45, RXRa 46, Foxh1 47, Hoxa1, Hoxb1, and Hoxb2 48, Smarcd3 49, FoxC1/C2 50, Cited1 51 were more highly expressed in Mesp1 progenitors at E7.5 (Fig. 5k and m). In addition, late Mesp1 progenitors also preferentially express genes controlling somitogenesis (eg: Notch1, Dll1, Lnfg, EphA4) (Table 1), consistent with the well known expression of Mesp1 and its target genes in the first somites 52. Altogether, the transcriptional profiling of Mesp1 progenitors during the early and late stage of Mesp1 expression identify known as well as novel putative markers distinguishing FHF and SHF progenitors.

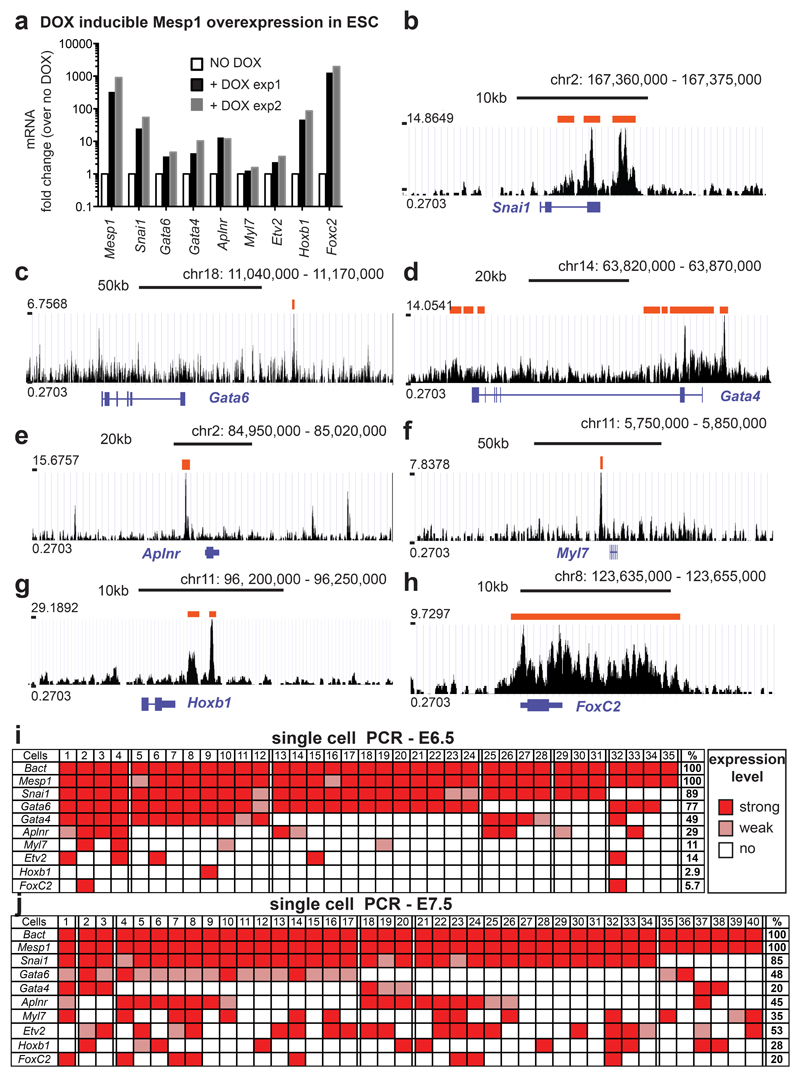

To further explore the molecular heterogeneity of Mesp1 progenitors during embryonic development, we performed single cell RT-PCR analysis to analyse the expression of several direct Mesp1 target genes, such as Snail1, Gata4, Gata6, Aplnr, Hoxb1, Myl7 and Foxc2 (Fig. 6a-h) on single FACS isolated Mesp1 H2B-GFP positive cells at E6.5 and E7.25 (Fig. 6i and j and Supplementary Fig. S6). Interestingly, not all direct Mesp1 target genes are expressed in every Mesp1 positive cells at the same time. Snail1 is the most commonly Mesp1 co-expressed gene irrespective of the embryonic stages (n=75), followed by Gata6, Gata4 and Aplnr (Fig. 6i and j). Interestingly, at E6.5, less than 10% of Mesp1 cells expressed Mesp1 target genes associated with SHF (Hoxb1 and Foxc2) 48, 53 (Fig. 6i). However at E7.5, the number of Mesp1 cells expressing SHF markers increased by 10 fold, with 20 to 30% of cells expressing either Hoxb1 or FoxC2 (Fig. 6j). The analysis of the expression of Myl7, a marker of cardiomyocytes 54, and Etv2, a transcription factor associated with endothelial and endocardial cell fate 55–58, revealed that at E6.5, Mesp1 cells usually expressed either Myl7 or Etv2, while at latter stages more Mesp1 expressing cells co-expressed these 2 markers (Fig. 6j), consistent with the early unipotent FHF and the late bipotent SHF progenitors found in our clonal analysis. These single cell transcriptional profiling of Mesp1 progenitors support the existence of molecularly distinct populations of Mesp1 progenitors, reflecting their different regional and lineage contribution.

Figure 6. Different temporal expression of Mesp1 direct target genes.

a. qRT-PCR analysis of Mesp1 target genes 24h after Dox administration in Dox inducible Mesp1 expression cells at D2 of ESC differentiation. The fold change is presented over the unstimulated cells (n=2 duplicates). b-h. Mesp1-Chip-Seq for Snai1 (b), Gata6 (c), Gata4 (d), Aplnr (e), Myl7 (f), Hoxb1 (g) and Foxc2 (h), showing that these genes are direct target genes of Mesp1 in ES cells. Red bars indicate significant peaks. i-j. Single cell RT-PCR analysis of Snai1, Gata6, Gata4, Aplnr, Myl7, Hoxb1 and Foxc2 as well as Etv2 in Mesp1 GFP+ cells at E6.5 (i) and E7.25 (j). β-actin and Mesp1 were used as internal positive controls. A dark colour indicates strong expression while a light colour indicates a weak expression (Supplementary Fig. S6). Blank cells indicate that no PCR amplification of the genes was detected. Percentages of cells expressing the markers are indicated on the right.

Discussion

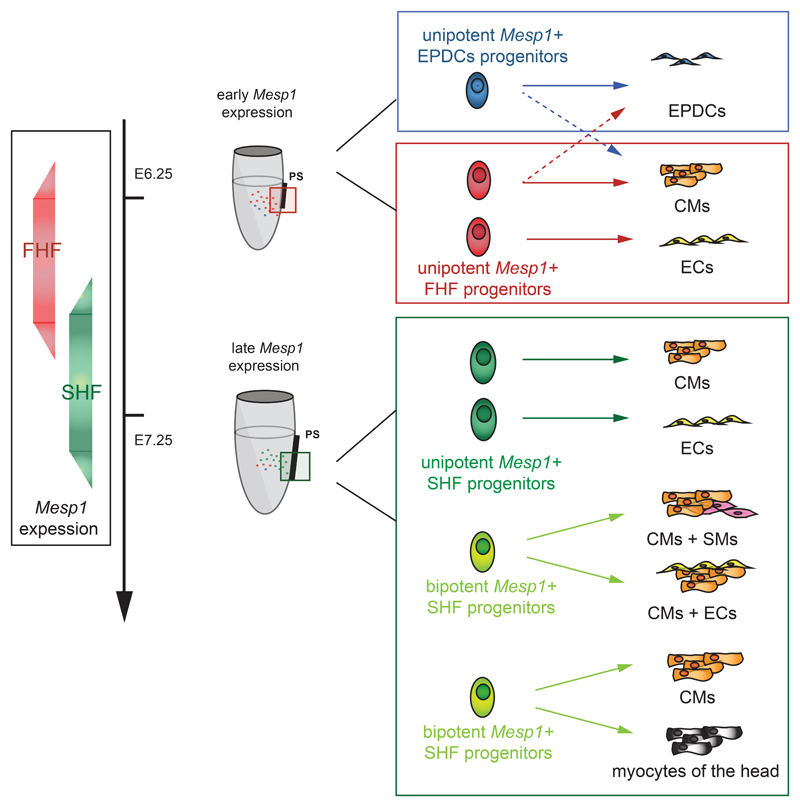

In contrast to the current model of cardiovascular development and lineage segregation, in which Mesp1 is thought to mark the most primitive multipotent cardiovascular progenitors common to the FHF and SHF, our temporal clonal analysis of Mesp1 expressing cells provides compelling evidence that Mesp1 marks distinct classes of cardiovascular progenitors with restricted lineage differentiation at different time points during gastrulation (Fig. 7). The absence of evidence for common FHF and SHF progenitors does not exclude the possibility that a minor portion of the heart may be derived from common progenitors of both heart fields that escape our inducible Mesp1 lineage tracing approach. However, since the inducible lineage tracing data recapitulate the tracing of the Mesp1-Cre knock-in mice that marks all cardiac lineages, it seems more likely that the common progenitor for FHF and SHF, identified in retrospective clonal analysis 3, exists before gastrulation and the onset of Mesp1 expression in the epiblast cells expressing Eomes, a transcription factor that directly controls Mesp1 expression 35, 36 and marks both the FHF and SHF by lineage tracing 36. The temporal clonal analysis developed here to label a single heart progenitor during the early stage of gastrulation can be used in the future to decipher the number, temporal specification, regionalization, mode of expansion, and differentiation potential of developmental progenitors from other organs or tissues.

Figure 7. Revised model of the early step of cardiovascular progenitor specification and lineage commitment during mouse development.

Clonal and molecular analysis of Mesp1 progenitors shows the existence of temporally distinct Mesp1 progenitors that contribute to the heart development. Mesp1 progenitors first gives rise to the FHF (in red) and then to the SHF (in green) progenitors with an overlapping expression of Mesp1 in the two populations at E6.75. FHF progenitors are unipotent and give rise to either CMs or ECs. SHF progenitors are either unipotent or bipotent. Epicardial and epicardial derived cells (EPDCs) arises as an independent Mesp1 derived lineage at the early time points.

Our prospective clonal analysis of heart development reveals that, unexpectedly, the vast majority of Mesp1 derived cardiovascular progenitors of the FHF are restricted to either CM or EC cell fates at the time of their specification. In contrast, Mesp1 derived SHF progenitors can be unipotent or bipotent. In addition, our study shows that epicardial progenitors arise at the early stage of cardiac mesoderm formation (Fig. 7). The major difference between the multilineage differentiation potential of cardiovascular progenitors in vitro 6, 13–15, 59 and their more restricted fate in vivo suggests that the ultimate fate of the progenitors can be regulated by the environmental cues that the different progenitors encounter during cardiac morphogenesis.

Our molecular analysis of Mesp1 progenitors at two different time points during embryonic development provides the first transcriptional profiling of the early cardiac progenitors in vivo and uncovered that the two populations of Mesp1 progenitors, although very similar molecularly, present also notable difference, consistent with their lineage and regional contribution. This analysis identified several key markers differentially expressed in the early and late Mesp1 progenitors, such as Mixl1, Otx1 and Evx1 that are preferentially expressed in the early Mesp1 cells while Aldh1a2, RXRa, Foxh1, FoxC1/C2, Hoxa1, Hoxb1, and Hoxb2, Smarcd3, all genes known to be expressed or controlling SHF morphogenesis 48, 53, are preferentially expressed in the late Mesp1 progenitors. Further studies will be required to define which of these differentially regulated genes temporally and spatially control the emergence of the distinct populations of Mesp1 progenitors during gastrulation. In addition, single cell RT-PCR of Mesp1 direct target genes revealed that Mesp1 expressing cells are molecularly heterogeneous. While previous studies proposed that Mesp1 acts as a master regulator of cardiovascular development 6, 8, 9, our analysis demonstrates that Mesp1 only induces the expression of a combination of different direct target genes in different cell types. Understanding how this specificity is achieved will be important to instruct and/or restrict the fate of multipotent cardiovascular progenitors into a particular cell lineage in vivo. The answers to these questions will be important both to design new strategies to direct the differentiation of ESC and iPS derived cardiovascular progenitors specifically into pure population of CMs, and for improving cellular therapy in cardiac diseases

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank F. Bollet-Quivogne and J.-M. Vanderwinden for their help with confocal imaging and M. Tarabichi for his help with GSEA analysis. We thank M. Buckingham and A. Joyner for kindly providing the probes for in situ hybridization. We also thank the Genomic core facility of the EMBL, Heidelberg for their help with the ChipSeq. F.L has been sequentially supported by the FNRS and the EMBO long-term fellowship. S.C. is supported by fellowship of the FRS/FRIA. X.L. is supported by the FNRS. A.B. is supported by the FRS/FNRS. S.R. and B.D.S. are supported by Wellcome Trust (grant number 098357/Z/12/Z). C.B. is an investigator of WELBIO. This work was supported by the FNRS, the ULB foundation, the Fondation contre le Cancer, the European Research Council (ERC), and the foundation Bettencourt Schueller (C.B. and F.L.).

Footnotes

Author contributions

C.B., F.L., S.C., XL designed the experiments and performed data analysis. F.L., S.C. performed most of the experiments. X.L performed the single cell PCR analysis. Y.A. generated the Mesp1-rtTA transgenic mice. A.R. and H. A. performed microarrays. C.P. provided technical assistance. C. D. helped with FACS isolation of Mesp1 expressing cells. A.B. helps in the design and initial characterization of the Mesp1-rtTA transgene. B.D.S. and S.R. performed the bio-statistical analysis of the clonal fate data. C.B. and F.L. wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Garry DJ, Olson EN. A common progenitor at the heart of development. Cell. 2006;127:1101–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly RG, Brown NA, Buckingham ME. The arterial pole of the mouse heart forms from Fgf10-expressing cells in pharyngeal mesoderm. Developmental cell. 2001;1:435–440. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meilhac SM, Esner M, Kelly RG, Nicolas JF, Buckingham ME. The clonal origin of myocardial cells in different regions of the embryonic mouse heart. Developmental cell. 2004;6:685–698. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saga Y, et al. MesP1 is expressed in the heart precursor cells and required for the formation of a single heart tube. Development (Cambridge, England) 1999;126:3437–3447. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bondue A, Blanpain C. Mesp1: a key regulator of cardiovascular lineage commitment. Circ Res. 2010;107:1414–1427. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bondue A, et al. Mesp1 acts as a master regulator of multipotent cardiovascular progenitor specification. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:69–84. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bondue A, et al. Defining the earliest step of cardiovascular progenitor specification during embryonic stem cell differentiation. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:751–765. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindsley RC, et al. Mesp1 coordinately regulates cardiovascular fate restriction and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in differentiating ESCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.David R, et al. MesP1 drives vertebrate cardiovascular differentiation through Dkk-1-mediated blockade of Wnt-signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:338–345. doi: 10.1038/ncb1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buckingham ME, Meilhac SM. Tracing cells for tracking cell lineage and clonal behavior. Developmental cell. 2011;21:394–409. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen-Gould L, Mikawa T. The fate diversity of mesodermal cells within the heart field during chicken early embryogenesis. Developmental biology. 1996;177:265–273. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei Y, Mikawa T. Fate diversity of primitive streak cells during heart field formation in ovo. Dev Dyn. 2000;219:505–513. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1076>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu SM, et al. Developmental origin of a bipotential myocardial and smooth muscle cell precursor in the mammalian heart. Cell. 2006;127:1137–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moretti A, et al. Multipotent embryonic isl1+ progenitor cells lead to cardiac, smooth muscle, and endothelial cell diversification. Cell. 2006;127:1151–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kattman SJ, Huber TL, Keller GM. Multipotent flk-1+ cardiovascular progenitor cells give rise to the cardiomyocyte, endothelial, and vascular smooth muscle lineages. Developmental cell. 2006;11:723–732. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haraguchi S, et al. Transcriptional regulation of Mesp1 and Mesp2 genes: differential usage of enhancers during development. Mech Dev. 2001;108:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saga Y, et al. MesP1: a novel basic helix-loop-helix protein expressed in the nascent mesodermal cells during mouse gastrulation. Development (Cambridge, England) 1996;122:2769–2778. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitajima S, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Inoue T, Kanno J, Saga Y. Mesp1-nonexpressing cells contribute to the ventricular cardiac conduction system. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:395–402. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckingham M, Meilhac S, Zaffran S. Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:826–835. doi: 10.1038/nrg1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snippert HJ, et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lescroart F, Mohun T, Meilhac SM, Bennett M, Buckingham M. Lineage tree for the venous pole of the heart: clonal analysis clarifies controversial genealogy based on genetic tracing. Circ Res. 2012;111:1313–1322. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.271064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harel I, et al. Distinct origins and genetic programs of head muscle satellite cells. Developmental cell. 2009;16:822–832. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambasivan R, et al. Distinct regulatory cascades govern extraocular and pharyngeal arch muscle progenitor cell fates. Developmental cell. 2009;16:810–821. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lescroart F, et al. Clonal analysis reveals common lineage relationships between head muscles and second heart field derivatives in the mouse embryo. Development (Cambridge, England) 2010;137:3269–3279. doi: 10.1242/dev.050674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris IS, Black BL. Development of the endocardium. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;31:391–399. doi: 10.1007/s00246-010-9642-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai CL, et al. Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Developmental cell. 2003;5:877–889. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanley EG, et al. Efficient Cre-mediated deletion in cardiac progenitor cells conferred by a 3'UTR-ires-Cre allele of the homeobox gene Nkx2-5. Int J Dev Biol. 2002;46:431–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang X, et al. HCN4 Dynamically Marks the First Heart Field and Conduction System Precursors. Circ Res. 2013;113:399–407. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spater D, et al. A HCN4+ cardiomyogenic progenitor derived from the first heart field and human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ncb2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milgrom-Hoffman M, et al. The heart endocardium is derived from vascular endothelial progenitors. Development (Cambridge, England) 2011;138:4777–4787. doi: 10.1242/dev.061192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riley PR, Smart N. Vascularizing the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91:260–268. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma Q, Zhou B, Pu WT. Reassessment of Isl1 and Nkx2-5 cardiac fate maps using a Gata4-based reporter of Cre activity. Developmental biology. 2008;323:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou B, et al. Epicardial progenitors contribute to the cardiomyocyte lineage in the developing heart. Nature. 2008;454:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature07060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou B, von Gise A, Ma Q, Rivera-Feliciano J, Pu WT. Nkx2-5- and Isl1-expressing cardiac progenitors contribute to proepicardium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;375:450–453. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van den Ameele J, et al. Eomesodermin induces Mesp1 expression and cardiac differentiation from embryonic stem cells in the absence of Activin. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:355–362. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costello I, et al. The T-box transcription factor Eomesodermin acts upstream of Mesp1 to specify cardiac mesoderm during mouse gastrulation. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1084–1091. doi: 10.1038/ncb2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christiaen L, et al. The transcription/migration interface in heart precursors of Ciona intestinalis. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2008;320:1349–1352. doi: 10.1126/science.1158170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lossie AC, Nakamura H, Thomas SE, Justice MJ. Mutation of l7Rn3 shows that Odz4 is required for mouse gastrulation. Genetics. 2005;169:285–299. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.034967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura H, Cook RN, Justice MJ. Mouse Tenm4 is required for mesoderm induction. BMC Dev Biol. 2013;13:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-13-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cruz C, et al. Induction and patterning of trunk and tail neural ectoderm by the homeobox gene eve1 in zebrafish embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3564–3569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000389107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hart AH, et al. Mixl1 is required for axial mesendoderm morphogenesis and patterning in the murine embryo. Development (Cambridge, England) 2002;129:3597–3608. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.15.3597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Acampora D, et al. OTX1 compensates for OTX2 requirement in regionalisation of anterior neuroectoderm. Gene expression patterns : GEP. 2003;3:497–501. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dush MK, Martin GR. Analysis of mouse Evx genes: Evx-1 displays graded expression in the primitive streak. Developmental biology. 1992;151:273–287. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsang TE, et al. Lim1 activity is required for intermediate mesoderm differentiation in the mouse embryo. Developmental biology. 2000;223:77–90. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niederreither K, et al. Embryonic retinoic acid synthesis is essential for heart morphogenesis in the mouse. Development (Cambridge, England) 2001;128:1019–1031. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sucov HM, et al. RXR alpha mutant mice establish a genetic basis for vitamin A signaling in heart morphogenesis. Genes & development. 1994;8:1007–1018. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Both I, et al. Foxh1 is essential for development of the anterior heart field. Developmental cell. 2004;7:331–345. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bertrand N, et al. Hox genes define distinct progenitor sub-domains within the second heart field. Developmental biology. 2011;353:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lickert H, et al. Baf60c is essential for function of BAF chromatin remodelling complexes in heart development. Nature. 2004;432:107–112. doi: 10.1038/nature03071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kume T, Jiang H, Topczewska JM, Hogan BL. The murine winged helix transcription factors, Foxc1 and Foxc2, are both required for cardiovascular development and somitogenesis. Genes & development. 2001;15:2470–2482. doi: 10.1101/gad.907301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dunwoodie SL, Rodriguez TA, Beddington RS. Msg1 and Mrg1, founding members of a gene family, show distinct patterns of gene expression during mouse embryogenesis. Mech Dev. 1998;72:27–40. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nomura-Kitabayashi A, et al. Hypomorphic Mesp allele distinguishes establishment of rostrocaudal polarity and segment border formation in somitogenesis. Development (Cambridge, England) 2002;129:2473–2481. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seo S, Kume T. Forkhead transcription factors, Foxc1 and Foxc2, are required for the morphogenesis of the cardiac outflow tract. Developmental biology. 2006;296:421–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kubalak SW, Miller-Hance WC, O'Brien TX, Dyson E, Chien KR. Chamber specification of atrial myosin light chain-2 expression precedes septation during murine cardiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16961–16970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferdous A, et al. Nkx2-5 transactivates the Ets-related protein 71 gene and specifies an endothelial/endocardial fate in the developing embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:814–819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807583106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kataoka H, et al. Etv2/ER71 induces vascular mesoderm from Flk1+PDGFRalpha+ primitive mesoderm. Blood. 2011;118:6975–6986. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-352658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rasmussen TL, et al. ER71 directs mesodermal fate decisions during embryogenesis. Development (Cambridge, England) 2011;138:4801–4812. doi: 10.1242/dev.070912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palencia-Desai S, et al. Vascular endothelial and endocardial progenitors differentiate as cardiomyocytes in the absence of Etsrp/Etv2 function. Development (Cambridge, England) 2011;138:4721–4732. doi: 10.1242/dev.064998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Misfeldt AM, et al. Endocardial cells are a distinct endothelial lineage derived from Flk1+ multipotent cardiovascular progenitors. Developmental biology. 2009;333:78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.