Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this study is to describe medications most commonly studied in pediatric polypharmacy research by pharmacologic classes and disease using a scoping review methodology.

Methods:

A search of electronic databases was conducted in July 2019 that included Ovid Medline, PubMed, Elsevier Embase, and EBSCO CINAHL. Primary observational studies were selected if they evaluated polypharmacy as an aim, outcome, predictor, or covariate in children 0–21 years of age. Studies not differentiating between adults and children or those not written in English were excluded. Study characteristics, pharmacologic categories, medication classes, and medications were extracted from the included studies.

Results:

The search identified 8,790 titles and after de-duplicating and full text screening, 414 studies were extracted for the primary data. Regarding global pharmacologic categories, central nervous system (CNS) agents were most studied (n=185, 44.9%). The most reported pharmacologic category was the anticonvulsants (n=250, 60.4%) with valproic acid (n=129), carbamazepine (n=123), phenobarbital (n=87) and phenytoin (n=83) being the medications most commonly studied. In studies which reported medication classes (n=105), Serotonin reuptake inhibitors ( n=32, 30.5%), CNS stimulants (n=30, 28.6%) and mood stabilizers (n=27, 25.7%) were the most studied medication classes.

Conclusion:

While characterizing the literature on pediatric polypharmacy in terms of the types of medication studied, we further identified substantive gaps within this literature outside of epilepsy and psychiatric disorders. Medications frequently identified in use of polypharmacy for treatment of epilepsy and psychiatric disorders reveal opportunities for enhanced medication management in pediatric patients.

1. Introduction:

The term “polypharmacy” is generally used to describe the use of multiple medications to treat one or multiple diseases. Polypharmacy usually amounts to ≥ 5 medications used by adults and ≥ 2 medications used by children [1–8]. Pediatric patients may be exposed to >5 medications daily during inpatient stays which may increase their risk for adverse events and drug-drug interactions [9–12]. Polypharmacy is often indicated for treatment of long-term illnesses like psychiatric illnesses [13, 14]. In spite of increased polypharmacy rates, research regarding the effects of long-term use and outcomes is limited, which ultimately decreases the strength of clinical evidence available for creation recommendations on best practices in pediatrics.

Polypharmacy has been well studied in children with psychiatric illnesses with some alarming revelations in increased prescribing patterns [15–18]. United States physician office visits of pediatric patients resulting in the patient receiving a prescription of an antipsychotic medication increased from 201,000 to 1,224,000 between 1995 to 2002 [19]. As prescription rates increase for antipsychotic medications, the chances for polypharmacy may also increase. A study by Lohr et al. examined data from psychiatric pediatric patients enrolled in Kentucky’s Medicaid program between 2012 – 2015 [17]. They found that 39.5% of pediatric patients were prescribed psychiatric polypharmacy for ≥90 days. In this study, stimulants were the most frequently prescribed medications. The most popular two-drug combinations included stimulants with an alpha agonist. Another study published psychiatric polypharmacy findings among pediatric patients using Medicaid data from 29 states. They were able to identify an increase in the use of second-generation antipsychotics while detecting a decrease in the use of antidepressants from 1999 to 2010 [20].

Compelling findings regarding the use of polypharmacy to manage psychiatric illnesses in pediatric patients are not isolated to the United States pediatric population. For example, Lagerberg et al. investigated rates of central nervous system (CNS) polypharmacy with antidepressants in pediatric patients living in Sweden [21]. The authors reported an increase in antidepressant prescribing from 1.4% in 2006 to 2.1% in 2013. In addition, prevalence of polypharmacy increased in the seven years from 52.4% to 62.1%. The most common medication class prescribed in this study was serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). In another study examining psychotropic medication profiles in community youth in Australia, a fifth of the study sample was on polypharmacy (n=37, 19.58%) with antidepressants most commonly prescribed (n=97, 51.32%). The prescribing of antidepressants and antipsychotics by psychiatric staff was mostly off-label [22].

Medication use is also of interest in pediatric polypharmacy in the inpatient setting. Regarding inpatient settings, a study that looked at pediatric polypharmacy in the United States identified that the most common medication exposures were acetaminophen, albuterol, antibiotics, fentanyl, heparin, and ibuprofen [23]. In contrast, a study conducted in India identified anti-infectives as the highest prescribed medication class for their inpatient pediatric hospital and often used in combination with other treatments [24].

The National Survey of Children’s Health finds that 18.5 percent of children have special health care needs, defined as an ongoing or chronic illness that is expected to increase their demand for health services for one year or longer. The prevalence of both Children with Special Health Care Needs (CSHCN) and the use of medications, often as polypharmacy, to manage their conditions is increasing [25]. CSHCN live longer with their illnesses, attributed to various factors including decreased infections, better treatment for high risk illnesses like sickle cell disease and congenital heart disease, decreased mortality in premature infants, genetic drift, and sociodemographic factors [24]. Stemming from rising survival rates are many concerns regarding the therapeutic management of children who receive polypharmacy. Many CSHCN are managed with multiple medications for illnesses such as HIV/AIDS, cystic fibrosis, epilepsy neurodevelopmental disorders, and asthma. As CSHCN may suffer multimorbidity their specific medication combinations have frequently not been studied. Frequently, medications are used off-label, or used for illnesses they have not been studied and approved by the Food and Drug Administration [26]. One consequence of the limitations of the research base is the inability to provide evidence-informed guidance, such as clinical practice guidelines.

Estimating the frequency of illnesses and types of medications most commonly studied is difficult for several reasons. Our research team has demonstrated the variability in the semantics of the literature regarding pediatric polypharmacy such as “multiple medications”, “polytherapy,” and “combination pharmacotherapy,” which may make a review of the literature cumbersome and inaccurate [9]. In addition, studies may address polypharmacy as a secondary or tertiary research aim, making them harder to identify in research synthesis. Many pediatric polypharmacy articles do not list medications names, classes, or pharmacologic categories along with frequencies. If they do, it may be for only one specific illness rather than several occurring simultaneously.

The purpose of this study is to describe medications most commonly studied in pediatric polypharmacy research by pharmacologic classes, and disease conditions using a scoping review methodology. We seek to inspire future research into pharmacotherapy for CSHCN. Uncovering gaps in medications evaluated in pediatric polypharmacy research will ultimately help in the design of research that studies therapeutic options for these medically vulnerable children.

2. Methods:

We conducted a scoping review according to the framework first proposed by Arksey and O’Malley and enhanced by others [27–33]. A scoping review is a type of knowledge synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question to establish key concepts, types of evidence, and gaps in research related to a field [28]. After specifying the research question, we searched for potentially relevant studies, selected qualifying studies, extracted relevant information, summarized and analyzed the information [34,35].

Our search strategy included both free text and controlled vocabulary for the concepts of polypharmacy (hyperpolypharmacy or hyper-polypharmacy or “hyper polypharmacy” or polypharmacy or poly-pharmacy or poly pharmacy or polytherapy or poly-therapy or “poly therapy” or poly-medication or polymedication or “poly medication” or “multiple medication” or “multiple prescription” or “combination pharmacotherapy”) and children (child or infant or neonate or toddler or adolescent or teen or pediatric or paediatric or school or boy or girl or baby or babies or newborn or juvenile or minors). The initial search was conducted in October 2016. The search was updated in July 2017 and July 2019. The databases searched were Ovid Medline, PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Ovid PsycINFO, Cochrane CENTRAL, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I, and the Web of Science Core Collection. In addition, we hand searched the bibliographies of six review articles and thirty random studies from the selected ones.

Primary observational studies were selected if they evaluated polypharmacy as an aim, outcome, predictor, or covariate in children 0–21 years of age. When a study did not define polypharmacy, our working definition was two or more medications irrespective of duration. Studies not differentiating between adults and children and those not written in English were excluded. Consistent with scoping review methodology, we did not assess the quality of the studies [27]. Two reviewers independently screened each study for inclusion using standardized forms in two phases: title/abstract and full text screening. Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the two reviewers or by the full group of nine reviewers if the two could not agree.

Information was extracted regarding study characteristics: country, year of publication, design, data sources, healthcare setting, and diseases. We also extracted medications, medication classes, and global pharmacologic categories. Medications were classified using the American Hospital Formulary Services (AHFS) Pharmacologic – Therapeutic Classification system [36]. Global pharmacologic categories, for the purpose of this article, represent body systems in which medication classes and then medications were organized. We also extracted information about whether polypharmacy was reported at class or drug level. We extracted up to 12 medications, 10 medication classes, and all pharmacological categories listed in each study. The data extraction was completed by one reviewer and reassessed by a secondary reviewer for accuracy.

We consolidated different medication brands into one generic name, classified medications whose classes were not directly reported in the studies according to the AHFS system and coded all extracted medication classes and pharmacologic categories. We computed the frequency of studies by study characteristics, diseases, and pharmacologic categories. After computing the frequency of medications by diseases, we reported medications occurring most frequently for each disease. Because some studies evaluated more than one disease, these frequencies were not mutually exclusive, hence not every medication listed under each disease was used for treating it, but the medication and disease were evaluated in the same study. EPPI Reviewer 4 (London, 2010) was used for creating screening and extraction forms, assigning studies to reviewers, double screening studies, reconciling differences, data cleaning and report generation. Data analysis was conducted using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary North Carolina).

3. Results:

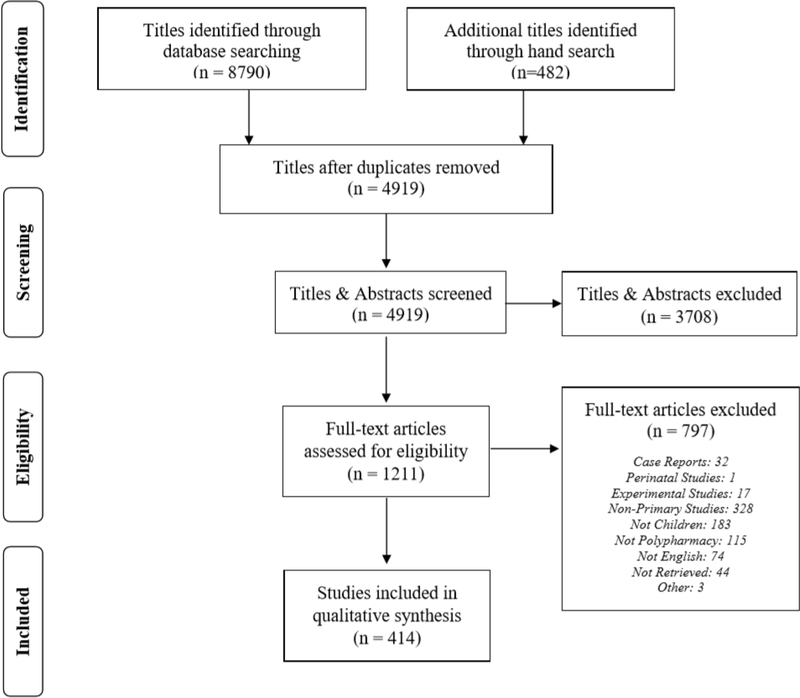

The search strategy identified 8,790 titles (Figure 1). After de-duplicating records, a total of 4,919 studies were screened by using the inclusion criteria. During review of full texts, 1,211 studies were evaluated for further inclusion, which resulted in a total of 414 studies that were extracted for primary data analysis. Table 1 reports the key characteristics of our included articles. Most studies originated in the United States (n=141, 34.1%), India (n= 29, 7.0%), Italy (n=18, 4.4%) or Japan (n=17, 4.1 %). Of the 414 articles identified, 398 (96.1%) reported pharmacologic categories, 105 (25.4%) reported medication classes, and 275 (66.4%) listed medications. A total of 203 (49.0%) articles listed medications from more than one pharmacologic category. Three hundred and fifty three studies reported minimum and maximum age of participants from which we categorized them as those with exclusively children 12 years or less (n=63), adolescents 13 to 21 years (n=24) and a combination of children and adolescents (n=266) (Appendix Table 1). CNS agents were studied across all age groups; psychotropic agents were predominantly studied among adolescents while somatic (anti-infective, analgesic, respiratory, and gastrointestinal) agents were predominantly studied among children.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of studies identified, screened, and extracted, PRISMA 2009

Table. 1.

Characteristics of pediatric polypharmacy literature

| Characteristic | Number of studies (N=414) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Country | ||

| USA† | 141 | 34.1 |

| India | 29 | 7.0 |

| Italy | 18 | 4.4 |

| Japan | 17 | 4.1 |

| Brazil | 14 | 3.4 |

| Turkey | 14 | 3.4 |

| Canada | 12 | 2.9 |

| UK‡ | 11 | 2.7 |

| Egypt | 9 | 2.2 |

| Poland | 9 | 2.2 |

| Others | 140 | 33.8 |

| Year | ||

| Up to 2000 | 63 | 15.2 |

| 2001–2010 | 132 | 31.9 |

| 2011–2019 | 219 | 52.9 |

| Design | ||

| Case control | 4 | 0.9 |

| Cross sectional | 253 | 61.1 |

| Prospective cohort | 68 | 16.4 |

| Retrospective cohort | 89 | 21.5 |

| Data sources | ||

| Primary | 186 | 44.9 |

| Chart review | 105 | 25.4 |

| Claims | 55 | 13.3 |

| EMR§ | 22 | 5.3 |

| Registry | 19 | 4.6 |

| Others & combinations¶ | 27 | 6.5 |

| Study setting | ||

| Outpatient | 210 | 50.7 |

| Inpatient | 91 | 22.0 |

| Combination | 37 | 8.9 |

| Others | 61 | 14.7 |

| Not reported | 15 | 3.6 |

| Medication classification | ||

| Reported pharmacologic categories | 398 | 96.1 |

| Reported medication class | 105 | 25.4 |

| Reported medications | 275 | 66.4 |

| Reported across >1 medication category | 203 | 49.0 |

USA = United States of America,

UK = United Kingdom,

EMR = Electronic medical record

Other data sources included registries, laboratories, and schools.

Other study settings included foster care facilities, schools, insurance companies, and general population.

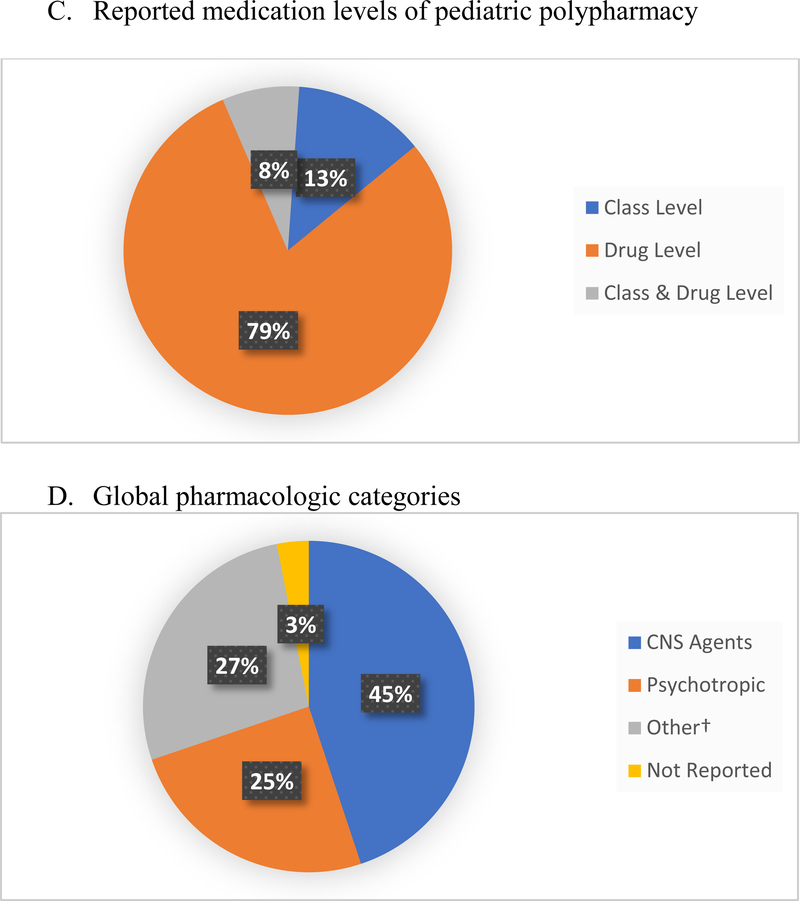

The majority of pediatric polypharmacy literature (n=325 studies, 78.5%) assessed polypharmacy at drug level (Figure 2a). Regarding global pharmacologic categories, central nervous system (CNS) agents (n=185, 44.9%) comprised the majority with psychotropic medications (n=103, 24.9%) the next largest group (Figure 2b). The most frequently reported pharmacologic category in pediatric polypharmacy research were the anticonvulsants (n=250, 60.4%) (Table 2). Next came antipsychotics (n=125, 30.2%), antidepressants (n=108, 26.1%), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medications (ADHD) (n = 88, 21.3%), and anti-anxiety medications (n=52, 12.6%). In the case of anti-infectives, antibiotics were studied more than antifungals - 16.7% vs. 4.6% respectively.

Fig.2.

Reported medication levels of pediatric polypharmacy and global pharmacologic categories

†Other = Global pharmacologic categories included anti-infective, analgesics, cardiovascular, endocrine, gastrointestinal, and respiratory medications.

Table. 2.

Most common pharmacologic categories

| Global category | Number (n = 414) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Central nervous system | ||

| Anticonvulsant | 250 | 60.4 |

| Psychotropic | ||

| Antipsychotic | 125 | 30.2 |

| Antidepressant | 108 | 26.1 |

| ADHD† | 88 | 21.3 |

| Antianxiety | 52 | 12.6 |

| Sedative hypnotic | 41 | 9.9 |

| Bipolar | 32 | 7.7 |

| Mood Stabilizer | 35 | 8.5 |

| Anti-infective | ||

| Antibiotic | 69 | 16.7 |

| Antifungal | 19 | 4.6 |

| Analgesic, anti-inflammatory | ||

| Analgesic (non-opioids) | 32 | 7.7 |

| Opioids | 21 | 5.1 |

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Antihypertensives | 31 | 7.5 |

| Endocrine | ||

| Glucocorticoids | 18 | 4.4 |

| Hormones | 12 | 2.9 |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Gastric Acid Reducers | 26 | 6.3 |

| Antiemetic | 12 | 2.9 |

| Respiratory | ||

| Asthma | 32 | 7.7 |

| Other | ||

| Supplements | 20 | 4.8 |

ADHD = Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

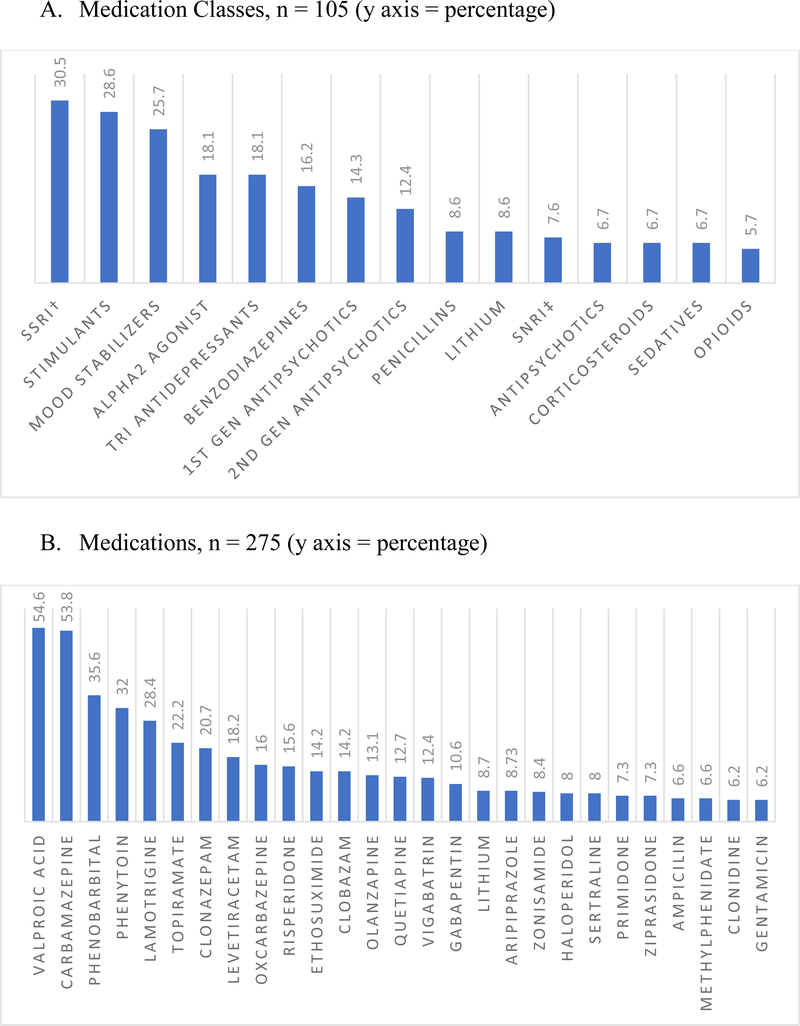

Of the 105 articles that reported medication classes, serotonin reuptake inhibitors were the most studied medication class (n=32, 30.5%), followed by CNS stimulants (n=30, 28.6%), and mood stabilizers (n=27, 25.7%) (Figure 3a). Beyond treatment for psychological or epileptic illnesses, penicillins (8.6%) and opioids (5.7%) were next in frequency. Of all the medications reported in our scoping review, valproic acid was the most studied medication (n = 139, 54.6%). Carbamazepine (n = 147, 53.8%), phenobarbital (n = 98, 35.6%), phenytoin (n = 88, 32.0%), lamotrigine (n = 78, 28.4%) were the next most studied medications among the 275 articles which reported medications (Figure 3b). Coincidentally, the majority of the medications reported were for CNS illnesses, with antibiotics (ampicillin, 6.6%; gentamicin, 6.2%) reported by less than <10% of the studies.

Fig. 3:

Most common medication classes and medications studied in pediatric polypharmacy literature.

† Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake Inhibitor

‡ Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

We investigated the most studied medications by disease (Table 3). For articles that evaluated epilepsy, valproic acid (n = 129) was reported in 64.5% and carbamazepine (n=123) was reported in 61.5% of them. Risperidone was the most listed medication for pediatric polypharmacy articles that studied depression (n=74), bipolar disorder (n=69), and psychosis (n=57) at 29.7%, 33.3%, and 44% respectively. Surprisingly, lithium (n = 12, 17.4%), a treatment of choice for bipolar disorder, was studied to a lesser extent. Articles that reported infectious diseases listed ampicillin and amoxicillin (n = 7, 26.9% each) as the most studied medications.

Table 3:

Percentages of most commonly reported medications in pediatric polypharmacy research by disease condition. Percent of disease is derived from the n of each disease condition and percent of total is derived from overall N (414). Because 53 studies evaluated multiple diseases, some medications may have been listed under disease conditions evaluated in the same study, but not necessarily used for treating them.

| Disease Condition | Medication † | Number | Percent of Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Epilepsy (n=200) |

Valproic Acid | 129 | 64.5 |

| Carbamazepine | 123 | 61.5 | |

| Phenobarbital | 87 | 43.5 | |

| Phenytoin | 83 | 41.5 | |

| Lamotrigine | 68 | 34.0 | |

| Clonazepam | 52 | 26.0 | |

| Topiramate | 56 | 28.0 | |

| Levetiracetam | 48 | 24.0 | |

| Ethosuximide | 39 | 19.5 | |

| Oxcarbazepine | 36 | 18.0 | |

| Vigabatrin | 34 | 17.0 | |

| Clobazam | 37 | 18.5 | |

| Zonisamide | 23 | 11.5 | |

| Primidone | 20 | 10.0 | |

| Gabapentin | 18 | 9.0 | |

|

Depression (n=74) |

Risperidone | 22 | 29.7 |

| Olanzapine | 18 | 24.3 | |

| Quetiapine | 16 | 21.6 | |

| Sertraline | 14 | 19.0 | |

| Lithium | 12 | 16.2 | |

| Aripiprazole | 10 | 13.5 | |

| Ziprasidone | 8 | 10.8 | |

| Bupropion | 7 | 9.5 | |

|

Bipolar (n=69) |

Risperidone | 23 | 33.3 |

| Quetiapine | 21 | 30.4 | |

| Olanzapine | 20 | 29.0 | |

| Haloperidol | 15 | 21.7 | |

| Aripiprazole | 14 | 20.3 | |

| Ziprasidone | 13 | 18.8 | |

| Lithium | 12 | 17.4 | |

| Carbamazepine | 12 | 17.4 | |

| Valproic Acid | 9 | 13.0 | |

| Lamotrigine | 7 | 10.1 | |

|

ADHD

‡ (n=71) |

Haloperidol | 13 | 18.3 |

| Clonidine | 12 | 17.0 | |

| Methylphenidate | 10 | 14.1 | |

| Chlorpromazine | 7 | 9.9 | |

| Atomoxetine | 7 | 9.9 | |

|

Psychosis (n=57) |

Risperidone | 25 | 44.0 |

| Quetiapine | 20 | 35.1 | |

| Haloperidol | 18 | 31.6 | |

| Aripiprazole | 14 | 24.6 | |

| Ziprasidone | 12 | 21.1 | |

| Sertraline | 9 | 15.8 | |

|

Anxiety (n=57) |

Sertraline | 10 | 17.5 |

| Clonazepam | 6 | 10.5 | |

|

Infections (n=26) |

Ampicillin | 7 | 26.9 |

| Amoxicillin | 7 | 26.9 | |

| Gentamicin | 6 | 23.1 | |

| Vancomycin | 4 | 15.4 |

Disease conditions with a frequency of >25 are represented,

ADHD = Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

We observed global geographical variation among pharmacological categories evaluated in pediatric polypharmacy research. Studies conducted in Europe and Asia predominantly assessed anticonvulsants (76.0% and 72.6% respectively, Appendix Table 2). Psychotropic agents were predominantly evaluated in North America with 59.7% of studies including antipsychotics compared to 20.8%, 6.6%, and 6.5% in Europe, Asia, and Africa, respectively. Antibiotics were predominantly studied in Africa (38.7% of studies), followed by Asia (23.6%), Europe (10.4%), and North America (7.8%).

4. Discussion:

This scoping review describes which medications are most frequently assessed in studies of pediatric polypharmacy by pharmacologic class and disease. We found that approximately 96% of pediatric polypharmacy studies reported pharmacologic categories, more than reports of individual medications or active ingredients. Epilepsy and psychiatric disorders were primarily represented in the research regarding this pediatric population in the USA. Anticonvulsants were the most common global pharmacologic category reported followed by antipsychotics and antidepressant agents. Valproic acid followed by carbamazepine and phenobarbital were the most studied of the specified active ingredients, all are used in the treatment of epilepsy. Despite the current concern about the overprescribing of antibiotics, we found that pediatric polypharmacy articles did not typically focus on medications used to treat infections or other acute diseases [36–47]. Gentamicin, a parenteral aminoglycoside antibiotic typically prescribed in the inpatient setting, appeared in approximately 6% of pediatric polypharmacy research articles.

Asthma, diabetes, obesity, malnutrition, and mental illness are all reported as common chronic illnesses in children living in the US [40]. Even among the majority of pediatric polypharmacy research within the US, we discovered that medications used for the management of these disease states were studied infrequently. This is particularly surprising for asthma for which multiple medications are often prescribed. Research in pediatric polypharmacy has nearly doubled since the year 2000, and yet, there are limited reports on polypharmacy in children with multiple chronic or acute illnesses. This observation may exist because multiple illnesses in pediatric patients are uncommon. There are chronic illnesses that affect children to some degree that are not studied in pediatric polypharmacy like HIV and cancer which warrant attention. Because of the prevalence of many illnesses outside of mental health disorders in this patient population, we feel there is an urgent call for targeted research with aims to improve pharmacologic management for somatic illnesses. What are the health risks and consequences of combination therapy for multiple disease states in pediatric patients? How do these combined treatments affect development, functional status, quality of life, and mortality? These are important questions clinicians and researchers should be assessing regarding pediatric polypharmacy. However, to date the majority of pediatric polypharmacy research revolves around treatment for epilepsy and psychiatric disorders.

Even though there is a plethora of research involving polypharmacy in children with epilepsy or psychiatric disorders, continuous evaluation is still warranted due to factors that affect overall pharmacotherapy outcomes for these patients [40]. Further research can elucidate the impact of many factors including age, diversity of illness patterns, significant drug interactions, medication sensitivity due to pharmacokinetic differences, and limited therapeutic options in pediatrics [41]. Despite polypharmacy having some benefits in pediatric patients, treatment with polypharmacy creates an evolving situation for monitoring health risks and outcomes [42,43]. Patients on polypharmacy can experience changes in the effectiveness of their medications when transient illnesses require the addition of other medications, such as in the case of infections, which then produce side effects that may worsen the symptoms of the primary illness [44]. For example, carbapenem antibiotics can decrease the serum level of valproic acid thereby leading to new onset seizures. [45,46]. In other situations, patients may develop or have worsening of another illness due to the effect of treatment of the primary chronic illness. For example, children with epilepsy treated with phenobarbital can experience ADHD symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and behavioral problems as a result of the treatment. If such patients also have ADHD, which is comorbid with epilepsy in nearly 30% of children, a worsening of ADHD symptoms can be expected [47, 48]. Another example are children who are treated with antipsychotic medications, such as clozapine, olanzapine, and risperidone. These children are at an increased risk to develop symptoms of metabolic syndrome consisting of weight gain, uncontrolled glycemia levels, and lipidemia, which may require further treatment [49]. Evidence shows an increased risk for the development of diabetes for pediatric patients on antipsychotics [50]. Yet, published studies are scarce regarding the co-pharmacologic treatment of these disease states and their side effects.

Table 3 lists the most common medications researched in pediatric polypharmacy by disease with epilepsy being our most researched polypharmacy chronic illness. One reason that epilepsy is more commonly studied is because polytherapy is often times indicated to treat this chronic illness. Pharmacotherapy management of epilepsy and mental illness is always challenging in children due to unlicensed and off-label use of medications and the diversity in pharmacokinetics related to the wide range of ages in pediatrics [43, 51]. We note that several medications were reported for treatment of more than one chronic illness. For instance, haloperidol was studied in patients with bipolar disease as well as ADHD. Further, valproic acid was studied in epilepsy, bipolar disorder and ADHD. Some medications listed are considered off-label treatment, which may also explain why they are listed with these disease states. Olfson and colleagues reported an increase in the off-label prescribing of antipsychotics for treatment of ADHD young people in the United States [52].

Drug interactions are also very common for some antiepileptic agents compared to others. For instance, oxcarbazepine has fewer drug-drug interactions compared to carbamazepine [53]. Some disease states, such as refractory epilepsy, also require more than two medications to decrease the risk of undesirable drug effects [54]. Valproic acid, carbamazepine, phenobarbital and phenytoin have been reported frequently in this scoping review, while safer therapy practice suggests their replacement by newer antiepileptic therapies which have lower side effects and fewer drug interactions [55]. This is not always possible due to the higher cost and limited availability of newer drugs all over the world.

Recently, a study conducted in Australia found that of 262 epileptic pediatric patients, 55.3% were prescribed polytherapy with an average of three medications [56]. Confirmed by our research, the most commonly prescribed antiepileptic medication was valproic acid. Intrigued by their results, the authors conducted a systematic review of the literature and were unable to find any trials that compared mono therapy versus polytherapy and efficacy or neurobehavioral outcomes of polytherapy as a primary outcome. Similarly, Anderson et al., studied adverse drug reactions to antiepileptic medications at a children’s hospital in the United Kingdom (UK) and found that valproic acid along with carbamazepine were their most prescribed medications [57]. They also reported that 25% (n = 45 of 180) of their epileptic patients were on polytherapy and of those on polytherapy 60% (n = 27 of 45) had adverse drug reactions versus only 21% (n =29 of135) of those on monotherapy. Regarding drug-related problems and adverse drug reactions, a study conducted in a Hong Kong pediatric ward found the overall incidence of drug related problems to be 21% and patients were more likely to experience drug-related problems if they were prescribed ≥ five medications [58]. Rashed et al., found the incidence of drug-related problems to be 45.2% among pediatric patients in a UK and Saudi Arabian hospital with polypharmacy as a potential risk factor [59]. This data accurately displays some of the risks of polypharmacy in various countries, which warrants making the management of pediatric polypharmacy a worldwide concern.

A pragmatic approach to address the concerns of the effects of polypharmacy in pediatrics while also fostering further research is to utilize medication therapy management (MTM). MTM has established positive therapeutic and economic outcomes in adult and geriatric patients [60–62]. MTM is process where a health-care specialist performs an extensive medication review to improve therapeutic outcomes while also detecting any medication related problems [63]. MTM is already supported for targeted patients through US national programs as a part of Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Plans and Medicare Advantage Plan, however this approach has not been extended to pediatric patients who qualify for Medicaid coverage. With the increased rates of children with epilepsy and psychiatric disorders being treated with polypharmacy, this vulnerable patient population should be added to the list of patients in need of this service as a part of national insurance programs. Globally, the addition of reimbursable MTM practices, or similar medication monitoring programs, to national health-care systems may help to identify positive and negative outcomes while also providing solutions. While polypharmacy may be needed to treat complex illnesses, increased monitoring and diligence in detecting adverse drug events will play an important role in positive health outcomes in pediatric patients.

This report emphasizes the great need for further pediatric polypharmacy research, especially when combining illnesses and the multitude of medications used to manage them. Our scoping review had some limitations, which may influence the generalizability of these results to all children. We grouped and classified the medications based on what was found in the study report; not all of the studies followed the standardized method. The lack of global classifications and inconsistency might have influenced generalizability. Because we extracted up to 12 medications per study, we may have left out some medications in studies reporting more than 12. Seventy-one studies reported more than 12 medications. In accordance with scoping review methodological frameworks, no assessment of quality was performed for included studies, which inherently limits our knowledge about credibility of each study. We were unable to evaluate whether the number of medications used in a patient represented rational pharmacotherapy. Another limitation when interpreting this study is that neuropsychiatric illnesses tend to cluster in the same patient; thus, disaggregating treatment effects, positive or not, is often challenging.

5. Conclusion:

Polypharmacy continues to be a challenging topic to research in the pediatric population. While identifying that the most studied medications were for the treatment of epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, we note gaps within this literature for somatic chronic illnesses. We encourage further research investigating polypharmacy used for somatic illnesses. Medications frequently identified in use of polypharmacy for treatment of epilepsy and psychiatric disorders reveal opportunities for enhanced medication management in pediatric patients. Not all prescribing of polypharmacy for pediatric patients is irrational, yet we believe vigilance in monitoring is necessary for safety. MTM may be a pragmatic, real world approach to improving practice and outcomes in pediatric patients with complex illnesses.

Key points:

Epilepsy and psychiatric disorders are primarily represented in the pediatric polypharmacy research.

Valproic acid followed by carbamazepine and phenobarbital were the most studied medications, which were all used in the treatment of epilepsy.

The clinical literature in these areas do not address the many drug combinations used in practice. Further clinical research including the evaluation of medication management approaches, are needed to improve care for children with special health care needs.

Acknowledgements:

We thank our expert stakeholders whose contribution at different stages of the project improved our research protocol, data quality, interpretation, and reporting: Dr. Joseph Calabrese, Dr. Faye Gary, Dr. Cynthia Fontanella, and Dr. Mai Pham. Thank you to Ms. Jennifer Staley, Dr. Sharon Meropol, Dr. Shari Bolen, and Dr. Almut Winterstein for their integral part in developing our methodology. We are also grateful to Ms. Courtney Baker, Ms. Rujia Liu who conducted a great amount of study screening, data extraction, data cleaning, quality checks, processing, and analysis. Finally, we show appreciation to Ms. Tenerica Madison for her help in the development of our charts.

Funding: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland): KL2TR002547; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development: K23 HD091295

Appendix Table 1:

Distribution of medication categories by age groups studied

| Medication categories | Children studies (Age <= 12), N=63 |

Adolescent Studies (Age 13–21), N=24 |

Both Children and Adolescent Studies, N=266 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central nervous agents | 33 (52.4) | 8 (33.3) | 165 (62.0) |

| Psychotropic agents | 9 (14.3) | 16 (66.7) | 101 (38.0) |

| Anti-infective | 31 (60.32) | 1 (4.2) | 30 (11.3) |

| Analgesics | 22 (35.0) | 2 (8.3) | 22 (8.3) |

| Respiratory | 19 (30.2) | 1 (4.2) | 18 (6.8) |

| Gastrointestinal | 17 (27.0) | 2 (8.3) | 18 (6.8) |

Appendix Table 2:

Most common pharmacologic categories in pediatric polypharmacy research by continent

| Pharmacologic category | Africa N=31 | Asia N=106 |

Europe N=96 | North America N=154 | Other† N=27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central nervous system | |||||

| Anticonvulsant | 17 (54.8) | 77 (72.6) | 73(76.0) | 68 (44.2) | 15 (55.6) |

| Sedatives/Hypnotic | 1(3.2) | 2 (1.9) | 11 (11.5) | 24(15.6) | 3(11.1) |

| Opioids | 0(0) | 1 (0.9) | 5(5.2) | 13(8.4) | 2(7.4) |

| Psychotropic | |||||

| Antipsychotic | 2(6.5) | 7(6.6) | 20(20.8) | 92(59.7) | 4(14.8) |

| Antidepressant | 2(6.5) | 7(6.6) | 19(19.8) | 77 (50.0) | 3(11.1) |

| ADHD‡ | 2(6.5) | 3(2.8) | 9(9.4) | 70(45.5) | 4(14.8) |

| Antianxiety medications | 0(0) | 1(0.9) | 10(10.4) | 40(26.0) | 1(3.7) |

| Bipolar medications | 2(6.5) | 0(0) | 2(2.1) | 28(18.2) | 0(0) |

| Mood stabilizer | 1(3.2) | 4(3.8) | 3(3.1) | 27(17.5) | 0(0) |

| Somatic diseases | |||||

| Antibiotic | 12(38.7) | 25(23.6) | 10(10.4) | 12(7.8) | 10(37.0) |

| Antihypertensive | 1(3.2) | 0(0) | 8(8.3) | 17(11.0) | 5(18.5) |

| Asthma medications | 2(6.5) | 7(6.6) | 5(5.2) | 13(8.4) | 5(18.5) |

| Analgesic (non-opioids) | 6(19.4) | 11(10.4) | 3(3.1) | 8(5.2) | 4(14.8) |

| Gastric acid reducers | 1(3.2) | 6(5.7) | 6(6.3) | 8(5.2) | 5(18.5) |

| Food supplements | 3(9.7) | 3(2.8) | 6(6.3) | 4(2.6) | 4(14.8) |

| Antifungal | 3(9.7) | 2(1.9) | 4(4.2) | 7(4.6) | 3(11.1) |

| Glucocorticoids | 1(3.2) | 2(1.9) | 2(2.1) | 9(5.8) | 4(14.8) |

Other Continents=south America and Australia

ADHD= Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: The authors, Alexis Horace, Negar Golchin, Elia M Pestana Knight, Neal V Dawson, Xuan Ma, James A. Feinstein, Hannah K. Johnson, Lawrence Kleinman, Paul M. Bakaki, certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

References:

- 1.Ahmed B, Nanji K, Mujeeb R, Patel MJ. Effects of polypharmacy on adverse drug reactions among geriatric outpatients at a tertiary care hospital in Karachi: A prospective cohort study. PloS One 2014; 9(11): e112133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, Naganathan V, Waite L, Seibel M J, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65(9): 989–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helal SI, Megahed HS, Salem SM, Youness ER. Monotherapy versus polytherapy in epileptic adolescents. Macedonian J Med Sci 2013; 6(2): 174–177. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatrics 2017;17(1): doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poudel P, Chitlangia M, Pokharel R. Predictors of poor seizure control in children managed at a tertiary care hospital of Eastern Nepal. Iranian J Child Neurol 2016;10(3): 48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasu RS, Iqbal M, Hanifi S, Moula A, Hoque S, Rasheed S, et al. Level, pattern, and determinants of polypharmacy and inappropriate use of medications by village doctors in a rural area of Bangladesh. ClinicoEcon Outcomes Res 2014;CEOR(6): 515–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug-related problems. British J Clin Pharm 2006; 63(2): 187–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakaki P, Horace A, Dawson N, et al. Defining pediatric polypharmacy: a scoping review. PLoS ONE 2018;13(11): e0208047. 10.1371/journal.pone.0208047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feudtner C, Dai D, Hexem KR, Luan X, Metjian TA. Prevalence of polypharmacy exposure among hospitalized children in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012; 166(1): 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feinstein J, Dai D, Zhong W, Freedman J, Feudtner C. Potential drug-drug interactions in infant, child, and adolescent patients in children’s hospitals. Pediatr 2015; 135(1): 399–e108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurian J, Mathew J, Sowjanya K, et al. Adverse Drug Reactions in Hospitalized Pediatric Patients: A Prospective Observational Study. Indian J Pediatr 2016. May;83(5):414–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai D, Feinstein J, Morrison W, et al. Epidemiology of polypharmacy and potential-drug-drug interactions among pediatric patients in intensive care units of U.S children’s hospitals. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016;17(5): e2018–e288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg JF, Brooks JO, Kurita K, et al. Depressive illness burden associated with complex polypharmacy in patients with bipolar disorder: findings from the STEP-BD. J Clin Psychiatr 2009;70(2):155–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preskorn SH, Lacey RL. Polypharmacy: When is it rational? J Psychiatr Pract 2007;13(2):97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fontanella CA, Warner LA, Phillips GS, Bridge JA, et al. Trends in psychotropic polypharmacy among youths enrolled in Ohio Medicaid, 2002–2008. Psychiatr Serv 2014; 65(11):1332–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Procyshyn RM, SU J, Eibe D, Liu AY, Panenka WJ, et al. Prevalence and patterns of antipsychotic use in youth at the time of admission and discharge from an inpatient psychiatric facility. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2014;34(1):17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohr DW, Creel L, Feygin Y, et al. Psychotropic polypharmacy among children and youth receiving Medicaid, 2012–2016. J Manag Spec Pharm. 2018;24(8):736–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soria SR, Lui X, Hincapie-Castillo JM, Zambrano D, et al. Prevalence, time, trends, and utilization patterns of psychotropic polypharmacy among pediatric Medicaid beneficiaries, 1999–2010. Psychiatr Serv 2018;69(8):919–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olfson M, Banco C, Lui L, et al. National Trends in Outpatient Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Antipsychotic Drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatr 2006;63:679–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soria R, Liu X, Hincapie-Castillo JM, et al. Prevalence, time trends, and utilization patterns of psychotropic polypharmacy among pediatric Medicaid beneficiaries, 1999–2010. Psychiatic Serv 2018;69(8):919–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagerberg T, Molero Y, D’Onofrio BM, et al. Antidepressant prescription patterns and CNS polypharmacy with antidepressants among children, adolescents, and young adults: A population-based study in Sweden. European Child & Adolesc Psychiatr. 2018; doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-01269-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dharni A & Coates D Psychotropic medication profile in a community youth mental health service in Australia. Children and Youth Service Review. 2018;90:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feudtner C, Dai D, Hexem K, et al. Prevalence of polypharmacy exposure among hospitalized children in the united states. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012;166(1):9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senthilselvi R, Boopana M, Sthyan L, et al. Drug utilization pattern in paediatric patients in a secondary care hospital. Int J Pharm & Pharm Sci. 2019;11: 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Survey of Children’s Health (2016 – 2018). In: Data Resource Center for Child & Adolescent Health. https://www.childhealthdata.org/browse/survey?s=2&y=28&r=1. Accessed 31 October 2019.

- 26.Hoon D, Taylor MT, Kapadia P, Gerhard T, et al. Trends in off-label drug use in ambulatory settings: 2006–2015. Pediatr 2019; 144(4): 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kern S Challenges in conducting clinical trials in children: approaches for improving performance. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2009: 2(6): 609–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arksey H, O’Malley LO. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005; 8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, et al. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67(12):1291–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13(48):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13(3):141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levac D, Colquhoun H, Brien KKO. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5(69):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods 2014; 5(4):371–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khalil H, Peters M, Godfrey CM, Mcinerney P, Soares CB, Parker D. An evidence-based approach to scoping reviews. Worldviews Evidence-Based Nurs 2016;13(2):118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bakaki P, Staley J, Liu R, Dawson N, Golchin N, Horace A, et al. A transdisciplinary team approach to scoping reviews: the case of pediatric polypharmacy. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18(1):102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Society of Health System Pharmacists. American Hospital Formulary Services Pharmacologic – Therapeutic Classification. 2018. https://www.ahfsdruginformation.com/ahfs-pharmacologic-therapeutic-classification/#1455219636269-43966bc3-86a3. Accessed 1 November 2018.

- 37.Grijalva CG, Nuorti JP, Griffin MR. Antibiotic prescription rates for acute respiratory tract infections in US ambulatory settings. JAMA 2009;307(7):758–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donnelly JP, Baddley JW, Wang HE. Antibiotic utilization for acute respiratory tract infections in U.S. emergency departments. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014;58(3):1451–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Bartoces M, Enns EA, File TM, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010–2011. JAMA 2016;315:1864–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torpy J, Campbell A, Glass R. Chronic diseases of children. JAMA 2010; 303(7): 682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patsalos PN. Drug interactions with the newer antiepileptic drugs (AEDs)--Part 2: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions between AEDs and drugs used to treat non-epilepsy disorders. Clin Pharmacokinet 2013;52(12):1045–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balan S, Hassali MA, Mak VSL. Challenges in pediatric drug use: a pharmacist point of view. Res Social Adm Pharm 2017;13(3):653–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gallego JA, Nielsen J, De Hert M, Kane JM, Correll CU. Safety and tolerability of antipsychotic polypharmacy. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2012;11(4):527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lochmann van Bennekom, Gijsman HJ, Zitman FG Antipsychotic polypharmacy in psychotic disorders: A critical review of neurobiology, efficacy, tolerability and cost effectiveness. J Psychopharmacol 2013;27(4):327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sander JW, Perucca E. Epilepsy and comorbidity: infections and antimicrobials usage in relation to epilepsy management. Acta Neurol Scan Suppl 2003;180:16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miranda MJ, Ahmad BB. Treatment of Rolandic epilepsy. Ugeskr Laeger 207;179(48). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Ool JS, Snoeijen-Schouwenaars FM, Schelhaas HJ, Tan IY, Aldenkamp AP, Hendriksen JGM A systematic review of neuropsychiatric comorbidities in patients with both epilepsy and intellectual disability. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;60:130–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verrotti A, Moavero R, Panzarino G, Di Paolantonio C, Rizzo R, Curatolo P The challenge of pharmacotherapy in children and adolescents with epilepsy-ADHD comorbidity. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38(1):1 – 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fedorowicz VJ, Fombonne E. Metabolic side effects of atypical antipsychotics in children: a literature review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(5): 533–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andrade SE, Lo JC, Roblin D, Fouayzi H, Connor DF, Penfold RB, et al. Antipsychotic medication used among children and risk of diabetes mellitus. Pediatr. 2011;128:1135–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Braüner JV, Johansen LM, Roesbjerg T, Pagsberg AK: Off-label prescription of psychopharmacological drugs in child and adolescent psychiatry. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2016;36:500–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Treatment of young people with antipsychotic medications in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72(9):867–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rutecki PA, Gidal BE. Antiepileptic drug treatment in the developmentally disabled: treatment considerations with the newer antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy Behav 2002;3(6S1):24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Belousova ED. Perampanel in treatment of refractory partial epilepsy in adolescents and adults: results of international multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III studies. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova 2014;114(8):32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ilies D, Huet AS, Lacourse E, Roy G, Stip E, Amor LB. Long-term metabolic effects in French-Canadian children and adolescents treated with second-generation antipsychotics in monotherapy or polytherapy: A 24-month descriptive retrospective study. Can J Psychiatry 2017;62(12):827–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Plevin P, Jureidini J, Howell S, Smith N. Paediatric antiepileptic polytherapy: systematic review of efficacy and neurobehavioral effects and a tertiary centre experience. Acta Paediatr. 2018; https://doi-org.ezproxy.lsuhsc.edu/10.1111/apa.14343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anderson M, Egunsola O, Cherrill J, Millward C, Choonara I. A prospective study of adverse drug reactions to antiepileptic drugs in children. BMJ Open 2015, 596: 008298. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rashed AN, Wilton L, Lo CC, Kwong BY, Leung S, Wong IC. Epidemiology and potential risk factors of drug-related problems in Hong Kong paediatric wards. BJCP 2014;77(5):873–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rashed AN, Neubert A, Tomlin S, et al. Epidemiology and potential associated risk factors of drug-related problems in hospitalised children in the United Kingdom and Saudi Arabia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68(12):1657–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schwartz EJ, Turgeon J, Patel J, Patel P, Shah H, Issa AM, et al. Implementation of a standardized medication therapy management plus approach within primary care. J Am Board Fam Med 2017;30(6):701–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wittayanukorn S, Westrick SC, Hansen RA, et al. Evaluation of medication therapy management services for patients with cardiovascular disease in a self-insured employer health plan. J Manag Care Pharm 2013;19(5):385–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramalho de Oliveira D, Brummel AR, Miller DB. Medication therapy management: 10 years of experience in a large integrated health care system. J Manag Car Pharm 2010, 16(3):185–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Leadership for Medication Management. https://www.accp.com/docs/govt/advocacy/Leadership%20for%20Medication%20Management%20-%20MTM%20101.pdf. Accessed 23 January 2019.