Abstract

Background

Perioperative opioid use is becoming an increasingly concerning topic in total joint arthroplasty (TJA). The current study aims to add to the paucity of prior studies that have detailed perioperative opioid use patterns and the effects of preoperative chronic opioid use among a cohort of total hip arthroplasty (THA) patients.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of 256 consecutive patients who underwent a THA at our institution between February 2016 and June 2016 was performed. Two cohorts were compared: patients deemed 1) preoperative chronic opioid users, and 2) non-chronic users. Variables compared included baseline characteristics, quality metrics, and patients’ opioid use histories 3 months prior to surgery and 6 months following surgery.

Results

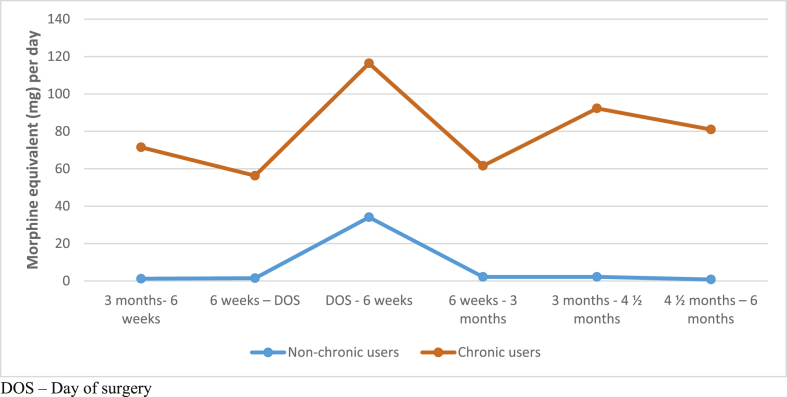

Of the 256 patients, 54 (21.1%) patients were identified as preoperative chronic opioid users. Baseline characteristics including age, gender, BMI, and ASA scores were similar between both cohorts. Discharge disposition, value-based purchasing (VBP) costs, length of stay (LOS), emergency room visits, and postoperative office visits were similar between the two cohorts. Readmission rates (30-day, 90-day, and 6-month) were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the chronic opioid users cohort. By the 6-month postoperative time period, chronic opioid users were consuming approximately 100-times the morphine equivalents than non-chronic users.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrates that a substantial proportion of preoperative chronic opioid users continue to consume large amounts of opioids up to 6-months following THA surgery. Furthermore, preoperative chronic use is significantly associated with poorer quality outcomes, specifically with respect to readmission rates.

Level of evidence

Level II, Prognostic Study.

Keywords: Total hip arthroplasty, Chronic opioid use, Value-based care, Quality outcomes, Opioid epidemic

1. Introduction

The indications for prescribing opioid medications has broadened since their initial intended use of treating pain associated with chronic diseases.1 Since then, recent opioid distribution has been occurring at alarming rates and quantities.2, 3, 4 This is particularly concerning within the total joint arthroplasty (TJA) population in which opioids have become a mainstay component of perioperative pain management regimens.

The harmful health effects of opioid over-use and abuse are well known,5, 6, 7, 8 and the literature on its clinical implications in TJA is quickly growing.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Past studies have associated perioperative chronic opioid use to poorer pain and functional outcomes9,13,14 as well as poorer quality outcomes including longer hospital stay (LOS)14 and higher readmission rates.15,16 Given the current shift towards performance, valued-based care TJA payment models, there is a clear need to better understand the implications of chronic opioid use and improve efforts to better manage these high-risk patients.

Recent efforts, such as the mandatory documentation of opioid prescriptions to state-wide prescription drug monitoring programs, have helped provide more comprehensive data on the prescribing and dispensing habits of providers and patients compared to historical methods.17, 18, 19 Only one other study has utilized this methodology to investigate the relationship between chronic opioid use and total hip arthroplasty (THA) outcomes.11 The current study aims to better understand this relationship by detailing the perioperative opioid use of THA patients. The study will also investigate the association between preoperative chronic opioid users and value-based metrics. We hypothesize that chronic opioid users will experience significantly poorer results with respect to value-based outcomes when compared to non-chronic users.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

Following Institutional Review Board approval, all patients who underwent THA at our institution from February 2016 to June 2016 were retrospectively reviewed for baseline characteristics, including demographics and perioperative features. Quality metrics as well as a detailed report of perioperative opioid use was collected and analyzed between the time periods 3 months prior to THA until 6 months following surgery. A total of 300 consecutive primary unilateral THA cases were initially identified. Inclusion criteria required patients to be at least 18 years of age, undergoing unilateral primary THA at our institution, and having sufficient data documented in the New York State's Internet System for Tracking Over-Prescribing – Prescription Monitoring Program (I-STOP/PMP).19 I-STOP/PMP is an online portal that enables medical providers to access detailed reports of a patient's opioid prescription history. After excluding all patients who did not have adequate data reported in the PMP, the final cohort of 256 patients was determined. Patients were then grouped into one of two cohorts: 1) preoperative chronic opioid users, 2) preoperative non-chronic opioid users. Patients were identified as chronic opioid users if they had taken a minimum of 20 mg/day morphine-equivalent dose of opioids for at least one consecutive month at any point 3 months prior to surgery. The one-month timeframe of continued opioid use was adapted from a study by Chu et al.6 that demonstrated that opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) development occurs after one month of daily opioid medication use. OIH is an increased sensitivity to pain reported by patients overly exposed to opioids. All patients in both cohorts received the institution's standard perioperative multimodal analgesia protocol.

2.2. Variables, outcome measures, data sources

Baseline characteristics including demographics, perioperative details, perioperative opioid use, and quality metrics were collected and analyzed on all patients from 3 months prior to TJA to 6-months after surgery. Quality measures collected included hospital length-of-stay (LOS), readmission rates, discharge disposition, and costs, measured through value-based purchasing costs (VBP). Value-based purchasing costs is a financial analysis developed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) of the quality of care delivered by hospitals.20 Cost values are composed of the clinical process of care, patient experience, clinical outcomes, and efficiency of each institution. All quality metrics were obtained using our institution's Quality Analytics database. In addition, we gathered information on ER visits and office visits through review of patient charts. All data was collected by a single research fellow in order to minimize inter-observer variability during the chart review process.

The I-STOP/PMP reports on type, dose, and quantity of all opioids prescribed in New York State for one calendar year. The date that the opioid medication was dispensed, the dose, and the number of pills prescribed was collected for each patient at pre-determined time intervals: 3-months – 6-weeks and 6-weeks – date of surgery, pre-operatively; date of surgery – 6-weeks, 6-weeks – 3-months, 3-months – 4.5-months, and 4.5-months – 6-months, post-operatively. The dose of opioid medication was converted into its morphine-equivalent dose (mg/day). We specifically investigated the cohort of patients undergoing THA between February 2016 and June 2016 because of the timeframe in which I-STOP/PMP reports its data. Selecting this 3-month block enabled us to maximize the number of subjects from the 3-month preoperative to 6-month postoperative target time period while adhering to the database's reporting period being restricted to the preceding 12 months of the search entry.

All patients included in the study underwent a primary, unilateral THA using an approach based on surgeon preference. All patients received the institution's standard perioperative multimodal pain management protocol: preoperative oral analgesics consisting of celecoxib, acetaminophen, and pregabalin; intraoperative spinal analgesia (preferable), and general anesthesia as an alternative; prior to wound closure, all patients received a peri-articular analgesic cocktail consisting of Marcaine, liposomal bupivacaine, morphine, and ketorolac; postoperatively, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) use was discouraged for all patients and PRN oral narcotics were administered for breakthrough pain. No standardized pain medication prescribing policies at discharge were in place at our institution throughout the course of this study.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Baseline patient characteristics were summarized using standard descriptive summaries. This included percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. The data was managed using Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Corporation, Richmond WA, USA). Chi-squared tests were utilized to conduct the initial analysis, which involved comparing perioperative details and outcomes between preoperative chronic and non-chronic opioid users. A 2-tailed Student t-test was used to compare the means between the two cohorts. The cutoff for assessing statistical significance was a p-value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were done using SPSS Statistics software (International Business Machine Corporation, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Patient demographics

In total, 256 consecutive patients undergoing THA at our institution were included in this study. Of these patients, 54 (21.2%) were identified as preoperative chronic opioid users, while 202 (78.9%) were identified as non-chronic users. Baseline characteristics including age, gender, BMI, and ASA scores were similar between the two cohorts. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographics between preoperative non-chronic and chronic THA opioid users, as well as between preoperative chronic THA opioid users who went on to change opioid use status 6 months following surgery.

| Demographics | Preoperative |

Postoperative (6-months) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-chronic opioid users (n = 202) | Chronic opioid users (n = 54) | p-value | Users cured of chronic use (n = 41) | Persistent chronic users (n = 13) | p-value | |

| Gender, F:M | 112:90 | 27:27 | 0.509 | 24:17 | 3:10 | 0.026 |

| Mean Age (SD) | 63.7 (10.9) | 60.8 (10.1) | 0.079 | 61.9 (10.1) | 58.2 (10.2) | 0.256 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 29.9 (7.3) | 31.2 (7.1) | 0.244 | 31.3 (6.9) | 31.0 (8.1) | 0.896 |

| ASA score: n (%) | 0.383 | 0.009 | ||||

| 1 | 4 (2.0) | 3 (5.6) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (15.4) | ||

| 2 | 116 (57.4) | 28 (51.9) | 26 (63.4) | 2 (15.4) | ||

| 3 | 78 (38.6) | 21 (38.9) | 13 (31.7) | 8 (61.5) | ||

| 4 | 4 (2.0) | 2 (3.7) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Mean ASA score (SD) | 2.5 (1.7) | 2.4 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.57) | 2.7 (0.95) | ||

ASA – American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI – Body mass index; SD – Standard deviation.

A sub-analysis was performed on the preoperative chronic users cohort (Table 1). This cohort was stratified into two groups: 1) patients who had been cured of their chronic opioid use habits 6 months following surgery, 2) patients who remained persistent chronic opioid users by this time point. A significantly higher prevalence of males (37.0%) remained persistent users compared to their female counterparts (11.1%) (p = 0.026). A significantly higher percentage of ASA score >2 were observed in the persistent users cohort (p = 0.009). Age and BMI were similar between the two cohorts.

3.2. Quality outcomes: preoperative chronic opioid users

Quality measures, including discharge disposition, hospital LOS, 30-day readmissions, 90-day readmissions, 6-month readmissions, ER visits, and hospital value-based-purchasing (VBP), were assessed and compared between the two cohorts. The mean LOS, discharge disposition, and number of ER visits were similar for the two groups (Table 2). The preoperative chronic opioid users demonstrated higher mean VBP costs and office visits than non-chronic users, although not to a significant degree. Non-chronic users had significantly lower rates of 30-day (p = 0.031), 90-day (p = 0.043), and 6-month readmissions (p = 0.046).

Table 2.

– Comparison of quality outcomes between preoperative non-chronic and chronic THA opioid users, as well as between preoperative chronic THA opioid users who went on to change opioid use status 6 months following surgery.

| Quality Metrics | Preoperative |

Postoperative (6-months) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-chronic opioid users (n = 202) | Chronic opioid users (n = 54) | p-value | Users cured of chronic use (n = 41) | Persistent chronic users (n = 13) | p-value | |

| Discharge disposition (%) | 0.779 | 0.080 | ||||

| HHS | 178 (88.1) | 45 (83.3) | 35 (85.4) | 10 (76.9) | ||

| Home with self-care | 3 (1.5) | 1 (1.9) | 0 | 1 (7.7) | ||

| SNF | 17 (8.4) | 7 (13.0) | 6 (14.6) | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Inpatient rehabilitation | 4 (2.0) | 1 (1.9) | 0 | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Mean LOS, days (SD) | 2.4 (1.3) | 2.4 (1.2) | 0.998 | 2.2 (0.9) | 3.1 (1.6) | 0.010 |

| Mean VBP costs (SD) | 4955.1 (3952.8) | 5501.1 (4573.1) | 0.384 | 5434.4 (4400.9) | 5711.5 (5138.2) | 0.850 |

| 30-day readmission (%) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (5.6) | 0.031 | 1 (2.4) | 2 (15.4) | 0.076 |

| 90-day readmission (%) | 6 (3.0) | 5 (9.3) | 0.043 | 2 (4.9) | 3 (23.1) | 0.049 |

| 6-month readmission (%) | 13 (6.4) | 8 (14.8) | 0.046 | 4 (9.8) | 4 (30.8) | 0.063 |

| # ER visits (%) | 11 (5.4) | 2 (3.7) | 0.605 | 1 (2.4) | 1 (7.7) | 0.233 |

| Avg Office visits (SD) | 2.1 (1.7) | 2.4 (1.5) | 0.239 | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.7) | 0.286 |

ER – Emergency room; - HHS - Home with healthcare services LOS – Length of stay; SD – Standard deviation; SNF - Skilled nursing facility; VBP – Value-Based Purchasing.

3.3. Quality outcomes: persistent chronic opioid users 6 months postoperatively

A sub-analysis was performed to evaluate quality outcomes among preoperative chronic opioid users who remained persistent chronic users versus patients who discontinued their chronic use habits 6 months postoperatively. The average LOS among the persistent chronic users was significantly higher (3.1 days versus 2.2 days; p = 0.010) (Table 2). Higher 90-day (p = 0.049) readmission rates were also observed in the persistent opioid using cohort, while 30-day (p = 0.076) and 6-month readmissions (p = 0.063) trended toward higher rates.

3.4. Perioperative opioid use patterns

In total, 846 prescriptions were filled by the patients in this study. On average, each patient received 3.3 prescriptions (range, 1–26) and 278.3 pills (range, 6–4874) during the study's 9-month time period. The most commonly filled prescriptions by average number of prescriptions per patient included oxycodone-acetaminophen, oxycodone, tramadol, and hydrocodone-acetaminophen, in that order. For each pre- and postoperative interval, preoperative chronic opioid users received significantly more opioid prescriptions and higher morphine-equivalent doses than non-chronic users (p < 0.001) (Table 3). Additionally, the percentage of each cohort filling prescriptions was significantly higher for chronic users as compared to non-chronic users in every time interval except for date of surgery – 6-weeks postoperative (p = 0.481).

Table 3.

Comparison of opioid use patterns between preoperative non-chronic and chronic THA opioid users over each preoperative and postoperative time interval.

| % of cohort filling prescriptions |

Average # of prescriptions filled |

Morphine equivalent per day |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-chronic users | Chronic users | p-value | Non-chronic users | Chronic users | p-value | Non-chronic users | Chronic users | p-value | ||

| Preop | 3 months- 6 weeks | 8.9% | 92.6% | <0.001 | 0.1 | 1.9 | <0.001 | 1.2 | 70.3 | <0.001 |

| 6 weeks – DOS | 4.5% | 64.8% | <0.001 | 0.1 | 1.0 | <0.001 | 1.5 | 54.8 | <0.001 | |

| Postop | DOS - 6 weeks | 95.0% | 92.6% | 0.481 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 0.020 | 34.1 | 82.3 | <0.001 |

| 6 weeks - 3 months | 14.9% | 55.6% | <0.001 | 0.2 | 1.3 | <0.001 | 2.2 | 59.4 | <0.001 | |

| 3 months - 4 ½ months | 10.4% | 63.0% | <0.001 | 0.1 | 1.6 | <0.001 | 2.2 | 90.1 | <0.001 | |

| 4 ½ months – 6 months | 6.8% | 51.9% | <0.001 | 0.1 | 1.2 | <0.001 | 0.8 | 80.2 | <0.001 | |

DOS – Day of surgery.

Six months following surgery, 15 patients (5.9%) were identified as chronic opioid users. Of these patients, 13 patients were preoperative chronic users while 2 were previously identified as non-chronic users prior to their surgery. Almost 27% of patients who were chronically using opioids prior to surgery stopped filling prescriptions all together by 6-months postoperatively. However, the morphine-equivalent consumption did not decrease for the preoperative chronic users cohort by this time point (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Between date of surgery – 6-weeks post-operation, chronic opioid users were being prescribed 1.6 times more prescriptions than the non-chronic users (p = 0.020) (Table 3). By the 6-weeks – 3-months, 3-months – 4.5-months, and 4.5 – 6-months postoperative time points, this increased to 6.5 times (p < 0.001), 16 times (p < 0.001), and 12 times (p < 0.001), respectively. At the 6-month postoperative time point, 51.9% of chronic users were still filling prescriptions as compared to 6.8% of non-chronic users (p < 0.001). At this same time point, chronic users were utilizing 80.2 mg morphine-equivalents per day, whereas non-chronic users were using 0.8 mg morphine-equivalents per day (p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

– Comparison of the morphine-equivalent opioid doses consumed between preoperative non-chronic and chronic THA opioid users over each preoperative and postoperative time interval.

4. Discussion

The current opioid epidemic is an increasing concern within the TJA population. Not only are these patients at risk to its harmful side effects,5, 6, 7, 8 poorer perioperative outcomes have been linked to chronic usage. The magnitude of the matter has been reflected by recent legislative efforts to better regulate the distribution patterns of opioid medications, as well as researching methods to prevent and manage dependency.21,22 One such effort has been the implementation of mandatory state-wide opioid registries, which have become an important resource for obtaining objective reports on the type, frequency, and dosages that patients are being prescribed and dispensed these medications. We used our state's prescription drug-monitoring database19 to provide a detailed account of the opioid use patterns of a consecutive cohort of patients undergoing THA, as well as their effects on quality outcomes following the procedure. Our findings demonstrate that a substantial proportion of preoperative chronic opioid users continue to consume large amounts of opioids up to 6 months following surgery. Furthermore, preoperative chronic use is significantly associated with poorer quality outcomes, specifically with respect to readmission rates.

Both the overall cohort of preoperative chronic opioid users as well as the preoperative chronic users who remained persistent chronic users at 6 months following surgery were about 3 years younger than their non-chronically using counterparts. Previous studies have supported these findings by identifying that younger age was a risk factor for higher opioid consumption following TJA,23 which may be explained by the higher reports of pain levels following these procedures among this population.24 Male gender was also found to be significantly more prevalent among persistent chronic opioid users. Interestingly, prior studies have identified females to be at higher risk for being persistent chronic opioid users,25,26 while other studies have relatedly shown that higher rates of females experience acute and chronic pain following THA than their male counterparts.24,27

In the current climate of performance-based payment models in TJA, value-based care will continue to be a point of emphasis. Among the common quality metrics used to evaluate the value of care, which include LOS, discharge disposition, and readmission rates, a common trend of increased readmission rates were observed in the preoperative chronic users cohort as well as the persistent chronic users cohort. Interestingly, almost a quarter of persistent chronic opioid users were readmitted within 90 days of surgery while almost a third of this cohort was readmitted within 6 months of surgery. Additionally, the LOS of the persistent opioid users cohort was almost a full day longer than preoperative users who discontinued their chronic opioid use habits within 6 months of surgery. Higher levels of in-hospital opioid consumption has been identified as a risk factor for long term opioid use as well as prolonged LOS. Although determining the exact relationship between increased LOS and persistent opioid use is beyond the focus of this study, the findings related to poorer perioperative quality outcomes among chronic opioid users reinforces the need to better identify and manage this at-risk population.

Past studies have investigated potential interventional strategies targeted at preoperative opioid use, which provide insight into improving upon existing management protocols. These include the use of preoperative risk-stratification instruments to identify high-risk patients,28 and tapering preoperative opioid doses during the months leading up to surgery.9 Also, the use of multimodal analgesia and regional anesthesia protocols while discouraging the use of in-hospital opioid consumption and patient-controlled analgesia have shown to decrease postoperative opioid use while decreasing LOS.29,30

State-wide opioid registries have been an underutilized resource for investigating perioperative opioid use among the TJA population. Only one study to date has used this resource for this purpose.11 This study by Zarling et al.11 demonstrated that 64% of preoperative chronic opioid users were still filling prescriptions 1-year following TJA while only 22% of non-chronic users were doing so by the same time point. In the current study, 51.9% of preoperative chronic users were filling prescriptions 6 months postoperatively while only 6.8% of non-chronic users were filling prescriptions at this time point. The 3-month postoperative period has been commonly cited as the point at which the most improvement in pain occurs since the preoperative stage among THA patients.31, 32, 33 However, in the current study, the morphine-equivalent doses consumed among the non-chronic opioid users cohort did not reach consumption levels below preoperative levels until the 6-month period while morphine-equivalent doses continued to remain above preoperative levels by the 6-month time point in the preoperative chronic opioid users cohort.

These delays in opioid consumption reductions relative to expected pain improvement may be explained by a couple of factors. One, as patients adapt to changes in lower-extremity biomechanics following the procedure, unnatural loads on contralateral joints may initiate or exacerbate pain,34, 35, 36, 37, 38 and thus require prolonged pain management. Another explanation for the unexpectedly high opioid prescribing patterns following surgery is the over-prescribing habits of providers. In fact, prior studies have identified that up to 70% of opioids prescribed to patients undergoing surgery are never taken.,39 [40] The authors of these studies attribute potential over-prescribing habits to a number of factors including efforts by providers to maximize patient satisfaction, the lack of knowledge of providers in knowing the amount of pills needed to relieve postoperative pain, and the desire by providers to reduce inconvenience (for both the patient and provider) in return visits to the clinic solely for prescription refills. A final explanation to the observed prolonged elevated opioid prescribing patterns, which is specific to the preoperative chronic opioid use cohort, is the paradoxical effect of OIH.6 OIH has been defined by previous studies as a phenomenon in which patients chronically taking opioid medications for over a month actually become hypersensitive to pain.

Overall, the issues of perioperative opioid use are multifactorial and therefore difficult to address. Much of the process in controlling patient's pain postoperatively starts from the preoperative stages. Protocols that can better assess patient's opioid use status preoperatively allow concerning patterns of opioid use to be addressed on a patient-to-patient basis. Dealing with postoperative pain in light of this information can be difficult but can be tempered with proper patient education and management of patient expectations. In addition, a multimodal approach to analgesia may afford additional options to help avoid over-prescribing opioid medications. While opioids may not be able to be completely avoided, a multimodal approach can allow for a lower dosage and frequency which may aid in tapering doses.

4.1. Limitations

There are a few limitations to the study. First, the study was conducted using a retrospective study design. The inherent nature of retrospectively collecting data makes it susceptible to data collection errors and biases while limiting the study from controlling for all variables involved. The researchers have made their best efforts to objectively collect and analyze the data, and have reduced inter-observer variability and biases by having only one investigator be responsible for all of the data collection and analysis. Second, 24 different surgeons were involved with performing the study's THA procedures, which may have led to some variability with respect to prescribing patterns between surgeons. Although all patients in both cohorts received the institution's standard perioperative multimodal analgesia protocol, there are currently no pain medication prescribing policies in place at discharge. We are not aware of any institutions in which such policies are implemented, thus, the potential surgeon-prescribing variability may not be relevant as they fall outside of the norms of standard care.

5. Conclusions

As hospitals continue to refine their practices with the goal of maximizing the quality of care delivered, opioid use among TJA patients has been a focus of improvement. State-wide opioid registries provide an important resource for obtaining detailed histories of patients’ perioperative opioid use habits and monitoring their effects on patient outcomes. The current study demonstrates that a substantial proportion of preoperative chronic opioid users continue to consume large amounts of opioids for prolonged periods following surgery. Given the poorer quality outcomes associated with these patients, specifically with respect to readmission rates, the proper risk-stratification and interventional methods targeting this population must be further investigated.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Schwarzkopf is a paid consultant for Intellijoint, Smith & Nephew, Corin USA, Stryker. Dr. Vigdorchik is a paid consultant for Intellijoint, Corin USA, and Stryker. The rest of the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcot.2019.04.027.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Boudreau D., Von Korff M., Rutter C.M. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. Dec. 2009;18(12):1166–1175. doi: 10.1002/pds.1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) CDC grand rounds: prescription drug overdoses - a U.S. epidemic. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Jan. 2012;61(1):10–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eriksen J., Sjøgren P., Bruera E., Ekholm O., Rasmussen N.K. Critical issues on opioids in chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. Nov. 2006;125(1):172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furlan A.D., Sandoval J.A., Mailis-Gagnon A., Tunks E. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: a meta-analysis of effectiveness and side effects. CMAJ (Can Med Assoc J) May 2006;174(11):1589–1594. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saunders K.W., Dunn K.M., Merrill J.O. Relationship of opioid use and dosage levels to fractures in older chronic pain patients. J Gen Intern Med. Apr. 2010;25(4):310–315. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1218-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu L.F., Clark D.J., Angst M.S. Opioid tolerance and hyperalgesia in chronic pain patients after one month of oral morphine therapy: a preliminary prospective study. J Pain. Jan. 2006;7(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris B.J., Mir H.R. The opioid epidemic: impact on orthopaedic surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. May 2015;23(5):267–271. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menendez M.E., Ring D., Bateman B.T. Preoperative opioid misuse is associated with increased morbidity and mortality after elective orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. Jul. 2015;473(7):2402–2412. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4173-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen L.-C.L., Sing D.C., Bozic K.J. 2016. Preoperative Reduction of Opioid Use before Total Joint Arthroplasty. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sing D.C., Barry J.J., Cheah J.W., Vail T.P., Hansen E.N. 2016. Long-Acting Opioid Use Independently Predicts Perioperative Complication in Total Joint Arthroplasty. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarling B.J., Yokhana S.S., Herzog D.T., Markel D.C. Preoperative and postoperative opiate use by the arthroplasty patient. J Arthroplast. 2016 Oct;31(10):2081–2084. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.03.061. Epub 2016 Apr 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franklin P.D., Karbassi J.A., Li W., Yang W., Ayers D.C. Reduction in narcotic use after primary total knee arthroplasty and association with patient pain relief and satisfaction. J Arthroplast. Sep. 2010;25(6):12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.M. G. Zywiel, D. A. Stroh, S. Y. Lee, P. M. Bonutti, and M. A. Mont, “Chronic Opioid Use Prior to Total Knee Arthroplasty.” [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Pivec R., Issa K., Naziri Q., Kapadia B.H., Bonutti P.M., Mont M.A. Opioid use prior to total hip arthroplasty leads to worse clinical outcomes. Int Orthop. Jun. 2014;38(6):1159–1165. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2298-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams J., Kester B.S., Bosco J.A., Slover J.D., Iorio R., Schwarzkopf R. The association between hospital length of stay and 90-day readmission risk within a total joint arthroplasty bundled payment initiative. J Arthroplast. Sep. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramos N.L., Karia R.J., Hutzler L.H., Brandt A.M., Slover J.D., Bosco J.A. The effect of discharge disposition on 30-day readmission rates after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. Apr. 2014;29(4):674–677. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monte A., Heard K., Hoppe J., Vasiliou V., Gonzalez F. The accuracy of self-reported drug ingestion histories in emergency department patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55(1):33–38. doi: 10.1002/jcph.368. 15AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roane T.E., Patel V., Hardin H., Knoblich M. Discrepancies identified with the use of prescription claims and diagnostic billing data following a comprehensive medication review. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(2):165–173. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.I-STOP/Prescription Monitoring Program (PMP) Internet System for Tracking Over-prescribing/Prescription Monitoring Program. 2013. https://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/narcotic/prescription_monitoring/ Available: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallis L. “21st century cures act—a cure-all for patients? AJN, Am. J. Nurs. Jul. 2016;116(7):19. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000484926.27907.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . 2017. Integrating & Expanding Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Data: Lessons from Nine States.https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pehriie_report-a.pdf [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petre B.M., Roxbury C.R., McCallum J.R., DeFontes K.W., Belkoff S.M., Mears S.C. Pain reporting, opiate dosing, and the adverse effects of opiates after hip or knee replacement in patients 60 Years old or older. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2012;3(1):3–7. doi: 10.1177/2151458511432758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu S.S., Buvanendran A., Rathmell J.P. Predictors for moderate to severe acute postoperative pain after total hip and knee replacement. Int Orthop. Nov. 2012;36(11):2261–2267. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1623-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inacio M.C.S., Hansen C., Pratt N.L., Graves S.E., Roughead E.E. Risk factors for persistent and new chronic opioid use in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh J.A., Lewallen D. Predictors of pain and use of pain medications following primary Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA): 5,707 THAs at 2-years and 3,289 THAs at 5-years. BMC Muscoskelet Disord. May 2010;11(90) doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nikolajsen L., Brandsborg B., Lucht U., Jensen T.S., Kehlet H. Chronic pain following total hip arthroplasty: a nationwide questionnaire study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. Apr. 2006;50(4):495–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boraiah S., Joo L., Inneh I.A. Management of modifiable risk factors prior to primary hip and knee arthroplasty: a readmission risk assessment tool. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. Dec. 2015;97(23):1921–1928. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu S.W., Szulc A.L., Walton S.L., Davidovitch R.I., Bosco J.A., Iorio R. Liposomal bupivacaine as an adjunct to postoperative pain control in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. Jul. 2016;31(7):1510–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu S., Szulc A., Walton S., Bosco J., Iorio R. Pain control and functional milestones in total knee arthroplasty: liposomal bupivacaine versus femoral nerve block. Clin Orthop Relat Res. Jan. 2017;475(1):110–117. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4740-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenguerrand E., Wylde V., Gooberman-Hill R. Trajectories of pain and function after primary hip and knee arthroplasty: the ADAPT cohort study. PLoS One. Feb. 2016;11(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halket A., Stratford P.W., Kennedy D.M., Woodhouse L.J. Using hierarchical linear modeling to explore predictors of pain after total hip and knee arthroplasty as a consequence of osteoarthritis. J Arthroplast. Feb. 2010;25(2):254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis A.M., Perruccio A.V., Ibrahim S. The trajectory of recovery and the inter-relationships of symptoms, activity and participation in the first year following total hip and knee replacement. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. Dec. 2011;19(12):1413–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foucher K.C., Wimmer M.A. 2011. Contralateral Hip and Knee Gait Biomechanics Are Unchanged by Total Hip Replacement for Unilateral Hip Osteoarthritis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shakoor N., Hurwitz D.E., Block J.A., Shott S., Case J.P. Asymmetric knee loading in advanced unilateral hip osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. Jun. 2003;48(6):1556–1561. doi: 10.1002/art.11034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shakoor N., Block J.A., Shott S., Case J.P. Nonrandom evolution of end-stage osteoarthritis of the lower limbs. Arthritis Rheum. Dec. 2002;46(12):3185–3189. doi: 10.1002/art.10649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sayeed S.A., Trousdale R.T., Barnes S.A., Kaufman K.R., Pagnano M.W. Joint arthroplasty within 10 years after primary charnley total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthoped. Aug. 2009;38(8):E141–E143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horstmann T., Listringhaus R., Haase G.-B., Grau S., Mündermann A. Changes in gait patterns and muscle activity following total hip arthroplasty: a six-month follow-up. Clin Biomech. Aug. 2013;28(7):762–769. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodgers J., Cunningham K., Fitzgerald K., Finnerty E. Opioid consumption following outpatient upper extremity surgery. J. Hand Surg. Am. Apr. 2012;37(4):645–650. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hill M.V., McMahon M.L., Stucke R.S., Barth R.J. Wide variation and excessive dosage of opioid prescriptions for common general surgical procedures. Ann Surg. Apr. 2017;265(4):709–714. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.