Abstract

Background

Different bulking agents are used in the compost of dewatered sludge (DWS). The aim of this study has been using of indigenous bulking agents (IBAs) in the enhancing of the DWS class of municipal wastewater from class B to class A and complementary stabilization of it for production of green manure in Sari city, Iran.

Methods

Three IBAs including the Saccharum Wastes (SW), Citrus Purning Wastes (CPW) and Phragmites Australis (PA) from eight IBAs were selected to be compared with the sawdust (SD) that was as a control bulking agent. Five turned windrow piles were constructed on a full scale and on base of optimal C/N equal 25.All experiments were performed on the base of the standard methods on initial mix and final compost.

Results

Among five windrow piles, P5 was been the best pile with a weighting ratio of DWS to IBAs (DWS: SW: CPW: PA) equal 1: 0.2: 0.24: 0.28. Pile P1 with weighting ratio DWS: SW equal 1: 0.6, Pile P3 with weighting ratio DWS: PA equal 1: 0.84, Pile P2 with weighting ratio DWS: CPW equal 1: 0.73 and Pile P4 with weighting ratio DWS: SD equal 1: 0.57 were placed in the next rounds. The results showed that the class of DWS enhanced to Class A for about 80 to 97 days and complementary stabilization of DWS by IBAs was done well and produced green manure in term of organic matter, potassium, germination index, PH, C/N and electrical conductivity had reached to the Grade 1 of Iran’s manure 10716 standard and in term of phosphorus and moisture had reached to the Grade 2 of this standard. Also heavy metals were below the maximum permissible of standards.

Conclusion

Using of IBAs, had a higher efficiency than the control bulking agent (sawdust) in enhancing sludge class and its stabilization, so that using of them in combination (mix of IBAs) had the highest efficiency and respectively, Saccharum Wastes (SW), Phragmites Australis (PA), Citrus pruning wastes (CPW) were placed in the next round, and sawdust was placed after them. By adding suitable IBAS, with an optimal ratio in turned windrow method, the class of DWS of sari WWTP enhanced to Class A and complementary stabilization of DWS has been well done and the produced green manure has been reached to agricultural standards and can be safely used in agriculture.

Keywords: Enhancing of dewatered sludge class, Class A, Indigenous bulking agents (IBAs), Green manure, Full scale

Introduction

Dewatered sludge (DWS) generated from municipal wastewater treatments, has useful and unuseful applications. One of the most appropriate useful applications of DWS is using from it as manure in agriculture because DWS is known as a biological product compatible with the environment and full of reinforcing nutrients for agricultural soil and it is known as appropriate replace for chemical nitrogen and phosphorus manures [1–3]. But DWS has many pollutants as fecal coliform, salmonella, virus, helminth ova, heavy metals that limit using about it in agriculture [4, 5]. In CFR 40 Provisions part 503 of EPA,DWS is divided to two Class B and Class A. The purpose of the sludge class B regulations is to reduce the fecal coliform to less than 2 million MPN/gD.S weight. Therefore, class B sludge is only used under strictly defined conditions and with strict agricultural constraints. The main purpose of the Class A regulations is to reduce the fecal coliform to less than 1000 MPN/g D.S weight, reduce salmonella to less than 3 MPN/4 g D.S weight, reducing the intestinal virus to less than 1 PFU/4 g D.S weight and the reduction of helminth ova to less than 1 ova/4 g D.S weight. Therefore, Class A sludge does not have any restrictions on agriculture [6, 7].

The Sari wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) in Mazandaran province of Iran has been designed for a population of 420000 people in 4 modules by the MLE aerobic method. The capacity of each module is 24242 cubic meters per day, which is designed for 105,000 people. The first module, which was financed by the World Bank, has been operated since 2014. At present, the first module with a capacity of 19500 cubic meters per day is in operation that is producing 1–3 tone DWS per day. Adding of the next three modules, the amount of DWS produced will be significant. So Enhancing of class of sludge from B to A and useful application of it in agriculture and fertilizing of soil and making money from created manure from the compost of sludge is necessary.

Composting method is a green biotechnology method and can be used to improve the DWS class and stabilization of it [8]. In composting method of dewatered sludge, when C/N ratio is low, is used from bulking agent as Wood Cheeps and Barley Straw [9], Spent Coffee Ground [10], Mushroom Substrate and Wheat Straw [11], Maize Straw [1], Cornstalk [12], rice husk [13], sawdust [14], Dry leaves cypress and pine trees [15] Acacia dealbata [16], Rice Straw [17], Pruning waste [18], Wheat Straw [11] and PMD (Penicillin Mycenyai Dreg) [19].

Sari is the center of mazandaran province in north of Iran and it has Mediterranean weather, High humidity and vigorous plant variation. So are created many Plant wastes in this area that can be used as IBAs. The dominant cultivation of northern Iran is rice and citrus. Millions tons of Rice Straw (RS) and Rice Husk (RH) are produced annually from rice fields, pruning wastes from Citrus gardens (CPW), Saccharum Waste (SW) from saccharum fields. CPW and SW are often burnt and are not useful used and are causing air pollution in the region [20]. Phragmites Autralis (PA), Sambucus ebulus (SE) and Typha latifoila grow along the agricultural fields and the ponds and rivers and roads of the north of the country rapidly and quickly each year, and they are often dried naturally without being used and often are burned by farmers. The Hyrcanian forests of the north of the country produce a huge amount of leaves that are rotten and not used every year. Also Street Trees Leaf (STL) is collected with other solid wastes that not to be used. Therefore, IBAs can be usefully used to produce green manure beneficial to soil fertility and increase crop yields [21].

So the objective of this research was (1) enhancing of DWS class to Class A and complementary stabilization by IBAs for production of green manure, (2) Prioritizing of IBAs and selection of the best of them (3) determining of appropriate weighting ratios DWS to IBAs, (4) Selection of the best pile.

Materials and methods

This research was done in three stages in the Sari wastewater treatment plant from 2017 to 2018. In order to accurately determine the qualitative characteristics of DWS, initial mix and final compost, the experiments were done in the laboratory of the Sari environmental health school of the mazandaran medical science university.

Determination of fecal coliform and C/N of DWS of the sari WWTP

The first stage was started from April 2017. In this stage, since no qualitative testing had been carried out on DWS in the Sari wastewater treatment plant, it was necessary to test the sludge samples and provide the fecal coliform and C/N of the DWS so that the sludge class to become clear.

Prioritizing of IBAs and determination of weighting ratios of DWS to IBAs

In the second stage, due to the need to bulking agents for composting of DWS, IBAs have been selected. The IBAs selected in this research are Saccharum Wastes (SW), Street Trees Leaf (STL), Rice Straw (RS), Rice Husk (RH), Citrus Purning Wastes (CPW), Phragmites Australis (PA), Sambucus ebulus (SE) and Typha latifoila. In choosing the most appropriate IBAs and prioritizing them, factors such as impact with less weight, C/N, environmental impacts, cost of purchase, transportation cost (availability), need or not need to be crushed, region native farmer favored, availability in all seasons, fast growth and availability in large volumes, no secondary contamination in the compost and delayed decomposition rates are considered. After prioritizing, three IBAs were selected and weighting ratios of DWS to IBAs were determined.

Full scale composting

The third stage of the research was conducted in 2018. At this stage, three more suitable IBAs have been selected and compared with the conventional bulking agent used in the articles (sawdust) as a control. Aerobic compost piles (Windrow) has been used for this research in full scale. The size of the piles was 2 m long, 1.5 m wide and 1.2 m high. The aeration was done inactive (weekly rotation).

One pile for each bulking agent were constructed based on the optimum C/N equal 25 [22, 23]. One pile of weight complex of three IBAs and DWS was constructed based on optimum C/N equal 25.Therefore, five piles were constructed and qualitative tests (parameters for promoting sludge class and sludge stabilization parameters) of the piles were compared and the best pile was selected. The amount of IBAs was determined by measuring carbon and nitrogen and C/N of DWS and IBAs.

The parameters tested in this study include (i) the parameters for determining the sludge class and (ii) the parameters that determine the sludge complementary stabilization and the quality of the produced green manure. Sludge class parameters include fecal coliform, Salmonella and helminth ova. Fecal coliform has been selected as index of sludge class and was measured by MPN standard method 9221 E, Salmonella by counting in culture medium standard method 9260 D, helminth ova according to EPA Guideline PFRP Provisions. The parameters that determine sludge complementary stabilization and the quality of green manure produced include C/N, phosphorus, organic matter, potassium, sodium, moisture, PH, electrical conductivity and temperature. The C/N ratio is selected as index of sludge stabilization. Carbon (TOC) by cold-walkeley-black method, N by Kjeldahl (TKN), organic matters by cold-walkeley-black, phosphorous by Olsen spectrophotometer in wavelength 470 nm, potassium by photometric method in wavelength 598 nm, Sodium by flame photometer method at 598 nm wavelength, moisture by gravimetric method in hot temperature 105 o C for 24 h, pH by SW-9045D potentiometric method, electrical conductivity by conductivity measurement and temperature using a special thermometer for composting measured. In addition to the parameters, heavy metals were also measured by flame atomic absorption method [24].

Results and discussion

Fecal coliform and C/N of DWS of the sari WWTP (first stage of research)

The results of measuring the start of operations on dewatered sludge are described in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Fecal coliform and C/N of DWS of the Sari WWTP

| Present Research | Class B Standard EPA | Class A Standard EPA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal Coliform (MPN/g D.S weight) | 2.37 × 106 | 2 × 106 | 1000 |

| %C | 24.6 | ||

| %N | 1.94 | ||

| C/N | 12.68 |

Considering the results of fecal coliform, it was clear that the Sari DWS class is in the class B of the EPA standard. So the sludge class should be enhanced for safety using in agriculture. Also, due to the low C/N ratio of DWS, it is necessary to add IBAs for increasing of this ratio

Determination of weighting ratios of DWS to IBAs (second phase of the study)

The IBAs was examined and tested and the results of this study are shown in Table 2 and were compared to other articles:

Table 2.

C/N of IBAs of this research in comparing with other bulking agents in articles

| %C | %N | C/N | %C, %N, C/N ratio of references | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Present research | 1–1- Indigenous Bulking Agents (IBAs) | Saccharum Waste (SW) | 44 | 0.163 | 270. | There was no record |

| Rice Husk (RH) | 34.5 | 0.28 | 123 |

C = 40.5, N = 0.75, C/N = 54 [13] C = 37.8, N = 0.6, C/N = 63 [25] C = 39.2, N = 0.339, C/N = 119.4 [26] |

||

| Rice Straw (RS) | 43.2 | 0.41 | 105 |

C = 48.9, N = 0.57, C/N = 85.8 [19] C = 31.2, N = 0.58, C/N = 54 [27] C = 34, N = 0.7, C/N = 48 [17] C = 59, N = 0.9, C/N = 65 [28] |

||

| Citrus Pruning Waste (CPW) | 38.7 | 0.24 | 161 | There was no record | ||

| Street trees leaf (STL) | 39.5 | 0.54 | 73 | C = 41.48, N = 0.676, C/N = 63.9 [26] | ||

| Phragmites Autralis (PA) | 36.4 | 0.32 | 113 | There was no record | ||

| Typha latifoila | 30.5 | 0.69 | 44 | There was no record | ||

| Sambucus ebulus (SE) | 38.7 | 0.656 | 59 | There was no record | ||

| 1–2-control(Blank) Bulking Agent | Sawdust | 45.7 | 0.152 | 300 |

C = 55.19, N = 0.087, C/N = 635 in Fine sawdust, and C = 55.3, N = 0.112, C/N = 493.8 in Coarse sawdust [29] C = 47, N = 0.26,C/N = 181 [16] C = 47,N = 0.26,C/N = 180 [19] C = 50, N = 0.1,C/N = 500 [30] C = 38.7, N = 0.125,C/N = 310 [23] C = 55, N = 1.8,C/N = 30.55 [31] C = 51.1, N = 0.1,C/N = 511 [32] C = 20–50, N = 0.1,C/N = 200–500 [33] |

|

| 2-Other bulking agents in articles | Wood Cheeps |

C = 47.1, N = 0.82, C/N = 57.4 [9] C = 46.3, N = 0.2, C/N = 220 [19] |

||||

| Barely Straw | C = 52.2, N = 1.01, C/N = 51.6 [9] | |||||

| Coniferous Bark | C = 54.5, N = 0.6, C/N = 90.83 [9] | |||||

| Cornstalk | C = 43.9, N = 0.8, C/N = 52.9 [34] | |||||

| Maize Straw | C = 40.6, N = 3.18, C/N = 12.76 [1] | |||||

| Wheat Straw |

C/N = 45.28 [11] |

|||||

| Moshroom Substance | C/N = 33.51 [11] | |||||

| Pruning waste | C = 32,N = 0.71,C/N = 45 [18] | |||||

| Acacia dealbata (Spanish IBA) | C = 52.5, N = 1.26, C/N = 41.7 [16] | |||||

| Dry leaves cypress and pine trees | C = 51.3, N = 0.42, C/N = 122 [15] | |||||

| PMD (Penicillin Mycenyai Dreg) | C = 44.3, N = 7.3, C/N = 5.2 [19] | |||||

| Sugar beet leaves | C = 59.9, N = 3.5, C/N = 17.1 [28] | |||||

Most papers have used Sawdust as bulking agent, with the C/N ratio Equal 200 to 500, which the results of this research are correspond with them. By comparing the amount of sawdust C/N with other bulking agents, it is observed that the amount of C/N of sawdust is higher than other bulking agents. So it can compensate the Shortage of carbon of sludge in a lower weight, which is more economical. For this reason, it has been used as a control bulking agent.

The results of this study showed that saccharum Waste (SW) has a good C/N in comparison with sawdust. The lowest C/N ratio was found for Typha latifoila, which is due to its higher %N than other indigenous bulking agents. The reason why nitrogen is higher in Typha latifoila is due to the desire to absorb and store nitrogen. For this reason, this plant is used as nitrogen absorber in advanced treatment of sewage treatment plans [36, 37].

The results of the prioritization of IBAs before composting and based on the factors mentioned in the materials and methods section and based on the C/N achieved in this section have resulted in the following results:

1-Saccharum Wastes (SW), 2- Citrus Purning Wastes (CPW), 3- Phragmites Australis (PA), 4- Sawdust, 5- Rice Straw (RS), 6- Rice Husk (RH), 7- Street Trees Leaf (STL), 8-Sambucus Ebulus (SE) and 9-Typha Latifoila.

Therefore, from the second stage of the study, three more suitable IBAs included SW, CPW, and PA were selected and compared with the conventional bulking agent used in the papers, Sawdast, as a control.

The most important factor for composting is the C/N ratio, therefore it is considered as the main indicator of sludge stabilization [38]. The ratio of 25 and 50 is suitable for aerobic composting. The optimum range for most organic wastes is from 20 to 25. This ratio for sludge should be in the range of 20–30 [33] or 25–30 [39]. In some articles, this ratio is 30 [40], and in some others it is 25 for the initial mixture of compost [22]. In lower ratios, ammonia is released and microbial activities are delayed and at higher ratios, nitrogen can be a limiting nutrient [21]. The wastewater treatment sludge has a low C/N ratio. In this study, the C/N ratio of DWS was 12.68, that’s a little less than the results of 24 in Alidadi’s paper [23], 29 in Mokhtari’s paper [41], 20.38 in parvaresh’s paper [26] and a little more than the results of 13.7 in Zorpas’paper [31], 10 in Nikaeen’s paper [15]. In this study, the reason for the low C/N ratio of DWS of the Sari is the low nitrogen content associated with the treatment process. The treatment process in WWTP of the sari is a conventional activated sludge with nitrogen removal of the MLE method. In some papers, The C/N ratio of the initial mixture was obtained as a trial and error from the weight ratio of the DWS to the bulking agent [16, 18] while in this study, the optimal ratio was first determined, and then the weight ratio of DWS to IBAs was obtained [22, 23, 29, 41].

Ponsa et al., used from three piles with three weighting ratios of DWS to pruning wastes in ratios of 1: 2, 1: 2.5 and 1: 3 that the C/N ratio of initial mixtures was obtained 10.6, 14.7 and 17.5, and pile 3 with C/N of initial mixtures of 17.5, was been the best pile [18]. Yanez et al., used from 4 piles with 4 weighting ratios of DWS to Acacia Dealbata in ratios of 0: 1, 1: 1, 2: 1 and 3: 1, with an initial C/N ratio of 41.7, 14.6, 11.9 and 10.3 that the pile 2 with the C/N initial mixture equaled 14.6, was the best pile [16]. Roka-Perez et al., used from two piles with two weighting ratios of DWS to rice straw in ratios of 2.6: 1 crushed rice straw and 2.6: 1 uncrushed rice straw, with C/N of initial mixture of 18 and 20, that the pile 1 with C/N initial mixture 18, was been the best pile [17]. Nikaeen et al., used from two piles with two weighting ratios of DWS to dry leaves cypress and pine trees in ratios of 1: 1 and 1: 3, with an initial C/N ratio of 20.4 and 36.9 that pile 2 with a C/N initial mixture equal to 36.9 was been the best pile [15]. Nafez et al., used from three piles with three weighting ratios of DWS to green plant wastes at ratios of 1: 1, 1: 2 and 1: 3, with an initial C/N ratio of 16.6, 28 and 41.3 that the pile2 with C/N of the initial mixture equaled to 28, was the best pile [42]. Parvaresh et al., used from 4 piles with 4 weighting ratios of DWS to sawdust in ratios of 8: 1, 8.5: 1.5, 1: 0.6 and 1: 0.5, with C/N of the initial mixture of 19.54, 20, 31.43 and 31.18 that pile of 3 with C/N of the initial mixture equal 31.43, was been the best pile [26].

It is seen that the initial C/N ratio in the above articles was obtained as a trial and error based on the weight ratio of the DWS to the bulking agent, which resulted in different results. While the optimal ratio must first be determined, then the weight ratio of the DWS to the bulking agent is to be obtained. Ammari et al., started with a C/N ratio of initial mixture of 32.6 [29], Moretti started with 30 [40],Glab started with 30 [1], Tao started with 25 [22] and Alidadi et al., started with 25 [23]. Therefore, in this study, the optimal C/N ratio of the initial mixture is considered equal 25. The C/N amount of DWS in the Sari WWTP was been 12.68. To increase the C/N to an optimum value of 25, IBAs was added to the DWS according to the proper weight ratios as follows:

P1 (SW) = pile 1: The weight ratio of DWS to SW was been 1: 0.6

P2 (CPW) = pile 2: The weight ratio of DWS to CPW was been 1: 0.73

P3 (PA) = pile 3: The weight ratio of DWS to PA was been 1: 0.84

P4 (sawdast) = pile 4: The weight ratio of DWS to SD was been 1: 0.57

P5 (mix of IBAs) = pile5: Weight ratio of DWS to SW to CPW to PA was been 1: 0.2: 0.24: 0.28

In this study, the ratio of C/N at the end of the operation and the final compost was considered to be 15. Because the optimal stabilization of sludge is achieved in C/N equal 15 [6, 17, 23, 40]. The C/N equal 15 represents the complementary stabilization of DWS because the growth of salmonella and coliform in less than 15 is minimized [43].

Initial mixing and final compost (third phase of the study)

After determining the proper proportions of IBAs, compost piles were arranged on the full scale in the sari WWTP, and sludge class tests, sludge stabilization experiments and the quality of green manure were produced, also heavy metals is done on the initial mixture and final compost, which is described in the Tables 3,4,5 and Figs. 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, and 9.

Table 3.

Results of experiments on sludge class parameters in the initial mix and final compost

| Initial mixing | Final Compost | Class B Standard EPA | Class A Standard EPA | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | ||||

| Parameters of Sludge Class | Fecal Coliform (MPN/g D.S weight) | 2.34 × 106 | 2.21 × 106 | 1.83 × 106 | 2.07 × 106 | 2.1 × 106 | 875 | 920 | 890 | 950 | 706 | 2 × 106 | 1000 |

| Salmonella (MPN/4 g D.S weight) | 52 | 35 | 44 | 32 | 48 | <3 | <3 | <3 | <3 | <3 | – | 3 | |

| Helminth ova (Ova/4 g D.S weight) | 385 | 410 | 380 | 368 | 427 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | 1 | |

Table 4.

Results of experiments of sludge stabilization parameters in the initial mixture and final compost

| Initial mixing | Final Compost | 10716 Standard of IRAN- Grade 2 | 10716 Standard of IRAN- Grade 1 | WHO | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | |||||

| Parameters of Sludge complementary Stabilization | %C | – | – | – | – | – | 19.27 | 20.25 | 21.13 | 20.7 | 21.15 | 15 minimum | 25 minimum | – |

| %N | – | – | – | – | – | 1.28 | 1.35 | 1.4 | 1.38 | 1.41 | 1–1.5 | 1.25–1.66 | 0.4–1.5 | |

| C/N | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 10–15 | 15–20 | – | |

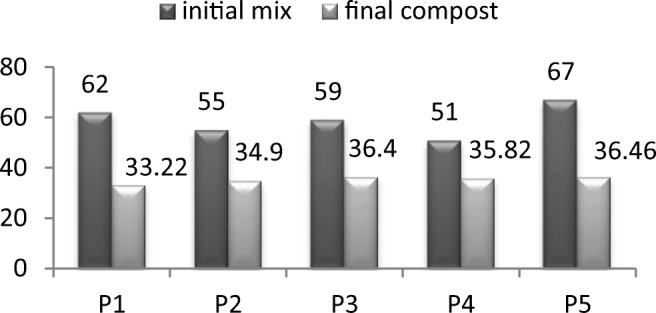

| % Organic Matter | 62 | 55 | 59 | 51 | 67 | 33.22 | 34.9 | 36.4 | 35.82 | 36.46 | 25 minimum | 35 minimum | 10–20 | |

| %P (P2O5) | 1.05 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3–3.8 | 1–3.8 | 0.2–3.8 | |

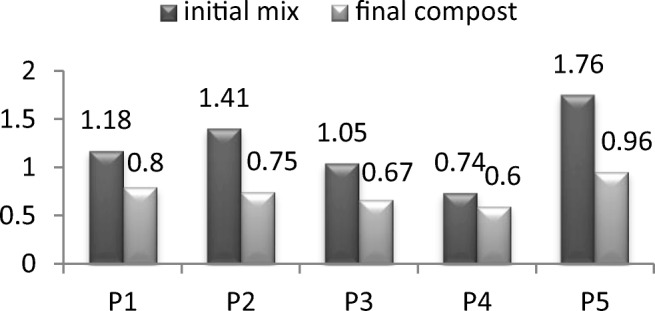

| %K (K2O) | 1.18 | 1.41 | 1.05 | 0.74 | 1.76 | 0.8 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.6 | 0.96 | 0.5–1.8 | 0.5–1.8 | 0.1–2.8 | |

| Electrical Conductivy (ds/m) | 1.43 | 1.65 | 1.47 | 1.51 | 1.72 | 1.64 | 1.71 | 1.48 | 1.72 | 1.8 | 14 maximum | 8 maximum | – | |

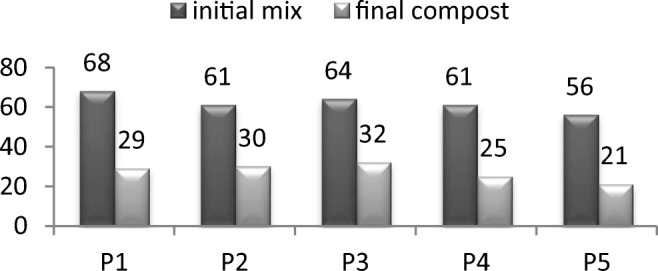

| % Moisture | 68 | 61 | 64 | 61 | 56 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 25 | 21 | 35 maximum | 15 maximum | 30–50 | |

| PH | 7.8 | 7.43 | 7.56 | 7.53 | 8.1 | 7.1 | 7 | 7.02 | 7.31 | 7.4 | 6–8 | 6–8 | 6–9 | |

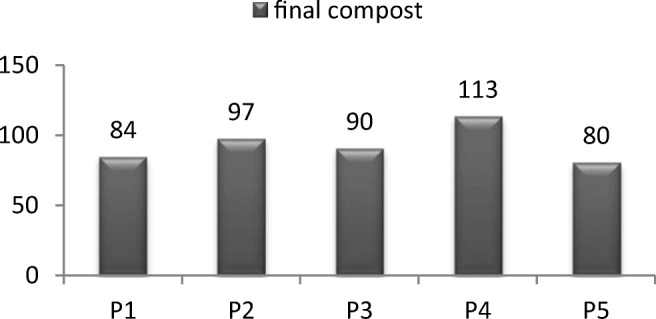

| Stabilization Time (day) | – | – | – | – | – | 84 | 97 | 90 | 113 | 80 | – | – | – | |

| Germination Index | – | – | – | – | – | 83 | 78 | 85 | 78 | 87 | 70 minimum | 70 minimum | – | |

Table 5.

Results of experiments of Heavy Metals in the final compost

| Final Compost | Iran National Standard,No:10716 | EPA Standard | WHO | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | |||||

| Heavy Metals (mg/kg ds) | Cd | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 10 | 39 | 15–40 |

| Pb | 24 | 21 | 23.2 | 25.18 | 24.75 | 200 | 300 | 200–400 | |

| Hg | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 5 | 17 | – | |

| Cr | 48.5 | 48.7 | 47 | 46.7 | 44.2 | 150 | 1200 | – | |

| As | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 10 | 41 | – | |

| Zn | 731 | 710 | 713 | 725 | 756 | 1300 | 2800 | 800–1200 | |

| Cu | 236 | 240 | 261 | 231 | 267 | 650 | 1500 | 90–260 | |

| Ni | 45.4 | 41 | 40 | 40.7 | 47.6 | 120 | 420 | – | |

Fig. 1.

%P in initial mix and final compost of piles

Fig. 2.

%K in initial mix and final compost of piles

Fig. 3.

% organic matters in initial mix and final compost of piles

Fig. 4.

EC of initial mix and final compost of piles

Fig. 5.

%moisture of initial mix and final compost of piles

Fig. 6.

PH of initial mix and final compost of piles

Fig. 7.

Stabilization Time of piles (day)

Fig. 8.

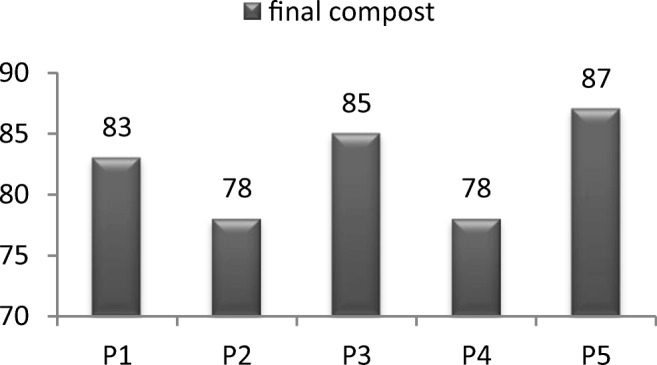

Germination Index of piles

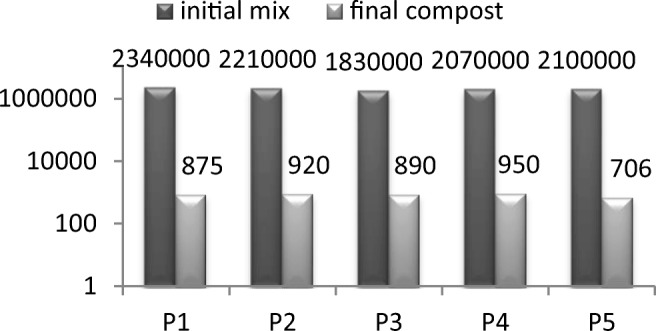

Fig. 9.

Fecal Coliform of initial mix and final compost of piles

Fecal coliform

Fecal coliform is the main index of the determination of sludge class is based on the provisions of CFR 40 Section 503 of the EPA standard [7]. For class B sludge, reaching to the PSRP standard of sludge and reduction in fecal coliform to less than 2 million MPN/g dry weights is considered. For Class A sludge, reaching for the PFRP standard of sludge and reduction in fecal coliform to less than 1000 MPN/g dry weight is considered. In this research, the fecal coliform of DWS of Sari WWTP was 2.37 × 106 MPN/g dry weights that was in range of Class B that was in accordance with those reported by Hait and Moretti [6, 40].

The results of the final composting showed that the use of suitable IBAs with optimal ratios in turned windrow method could reduce fecal coliforms and enhance the class of DWS of the sari WWTP to Class A standards [44]. Even in comparison with the control bulking agent, sawdust, the percentage of removal of fecal coliform was also higher, so that the highest percentage of fecal coliform removal was related to pile P5 and respectively piles P1, P2, P4 and P3 were placed in the next round.

Salmonella

Another indicator of the sludge class, based on the EPA standard, is the reduction of salmonella to less than 3 MPN/4 g D.S weight [6, 7]. The salmonella of the initial mix of piles was from 32 to 52 MPN per 4 MPN/4 g D.S weight, which was much higher than the EPA standard [43]. The results of the final composting showed that the use of IBAs could convert salmonella and enhance the class of DWS of the sari WWTP to Class A standards that was in accordance with those reported by Bazrafshan et al. [45]. Even in comparison with the control bulking agent, sawdust, had a higher percentage of salmonella removal, so that the highest salmonella removal percentage was related to pile P5 and respectively piles P1, P2, P3 were placed in the next round and the lowest percentage of removal was related to pile P4.

Helminth ova

Another indicator of the sludge class in accordance with the EPA standard is to reduce the helminth ova to less than 1 ova/4 g D.S [6, 7]. The number of parasite eggs of initial mix of piles were from 368 to 427 that was in accordance with those reported by Navarro et al. for Developing countries [46]. The results of the final composting showed that the use of IBAs, with optimal ratios in turned windrow method, could reduce helminth ova and enhance the class of DWS of the sari WWTP to Class A standards.

Organic matters

In this research, the percentage of organic matters in the initial mix of piles was from 51 to 67 that was in accordance with those reported by Ponsa, Roka-Perez and Zorpas [17, 18, 34]. The results of the final composting showed that the use of IBAs, with optimal ratios in turned windrow method, could perfectly stabilize the DWS. Even in comparison with the sawdust has a higher stabilization, so that the highest percentage of organic matter removal or, in other words, the highest mineralization rate of organic matters related to pile P5 and respectively P1, P2 and P3 were in the next and the lowest percentage of mineralization related to P4. Finally, the highest percentage of organic matters belonged to the P5 and respectively P3, P4, P2 and P1 were in the next. The produced manure in terms of organic matters was in the Grade 1 of Iran’s manure 10716 standard because the percentage of organic matters of the final compost in all piles was in the range of at least 35% of this standard.

Phosphorus

In this research, the percentage of phosphorus in the initial mix of piles was from 0.6 to 1.2 that was in accordance with those reported by Cai and Rihani [27, 28]. The percentage of final compost phosphorous in all of the piles was not been in the range of 1–3.8% of the Grade 1 of Iran’s manure 10716 standard, but it was been in the range of 0.3–3.8% of grade 2 of this standard and the created manure in terms of percentage of phosphorus was in Iran’s manure Grade 2. Because phosphorus of IBAs was very low compared to DWS [16, 17]. The highest percentage of phosphorus in final compost was related to pile P2 and respectively P1, P5, P3 and then P4 were in the next.

Potassium

In this research, the percentage of potassium in the initial mix of piles was from 0.74 to 1.76 that was in accordance with those reported by Rihani [28] and Roca-Peres [17]. By adding IBAs to DWS, potassium content increased because based on references, bulking agents have more potassium content than DWS [17, 28]. So the final compost of P5 has the most potassium and respectively P1, P2, P3 and P4 were in next round. Total potassium content of the final compost in all of the piles was been in the range of 0.5–1.8% of the Grade 1 of Iran’s manure 10716 standard and the created manure in terms of percentage of potassium content was in Iran’s manure Grade 1.

Electrical conductivity & PH

In this research, electrical conductivity of the initial mix of piles was from 1.43 to 1.72 d.s/m that was in accordance with those reported by Zhang [19]. Electrical conductivity of the final compost of all the piles was in the range of maximum 8 manure of Grade 1 of Iran’s 10716 standard. PH of the final compost of all the piles was been in the range of 6–8 manure of Grade 1 of this standard. So the produced manure in terms of electrical conductivity and PH was at the level of manure of Grade 1 of Iran.

Moisture

The percentage of moisture of the initial mix of piles was from 56 to 68 that was in accordance with those reported by Kulikowska [9]. The percentage moisture of compost in all piles was not been in the maximum range of 15% of the Grade 1 of Iran’s manure 10716 standard, but was been in the maximum range of 35% of Grade 2 of this standard that was in accordance with those reported by Villasenor [47]. So the manure is in terms of moisture content was in Iran’s manure Grade 2.

Complementary stabilization time

One of the most important parameters of IBAs’s comparison is Complementary Stabilization Time. Any IBA can stabilize DWS at a lower time, is better. The index of compost Stabilization is reaching to C/N equal 15 [6]. In this study, the least Stabilization time was for the P5 and then P1 and the greatest Stabilization time was for P4. Because available carbon (containing the simpler glucose and sucrose sugars) of sacharum wastes is more than sawdust, which have a faster degradation than cellulose and lignin in sawdust. Also Stabilization time of P1 and then pile P3 and then pile P2 were less than the pile P4.

Germination index

The germination index indicates the presence or absence of phytotoxic compounds in the compost and is used to determine the contamination rate of plants from compost [48–50]. In this research, is used from the cress. The final compost germination index in all of the piles is more than at least 70 in the Grade 1 of Iran’s manure 10716 standard and the produced manure in terms of germination index is in this range that was in accordance with those reported by Guo [21]. So the compost of all piles was manure and phytotoxic-free. Comparison of the piles showed that there is little difference in the germination index between the piles. However, the highest germination index was related to pile P5, and respectively P3, P1, P2 and finally P4 had the lowest germination index.

Heavy metals

The heavy metal parameter is not a component of sludge class and sludge stabilization. However, it has been measured as a control parameter to ensure that the manure is safe [51]. Because it may have been entered into the sewage collection network from the local industrial manufactures. In this research, the final compost of piles was less than the results of other papers [3, 17, 52, 53]. Also the heavy metals of the final compost of all piles were in the range of Iran’s 10716 standard. Because at present there are no heavy metals manufacturing companies in the region studied,that previous study of this author on heavy metals of DWS of the Sari WWTP confirm it [54] .

Conclusion

It can be concluded that by adding suitable IBAS, with optimal ratios in turned windrow method, the class of DWS of sari WWTP can be enhanced to Class A for about 80 to 97 days. Also during this time, the complementary stabilization of DWS has been well done and the produced green manure has been reached to agricultural standards and can be safely used in agriculture. The prioritization of IBAs before composting showed that the most suitable IBA was the Saccharum Waste (SW), and respectively CPW, PA, SD, RS, RH, STL, SE, and TL were placed in the next rounds. The results after composting of them with optimal ratios showed that the use of IBAs, had a higher efficiency than the control bulking agent (sawdust) in enhancing sludge class and its stabilization, so that using of them in combination (mix of IBAs) had the highest efficiency and, respectively, Saccharum Waste (SW), Phragmites Australis (PA), Citrus pruning waste (CPW) were placed in the next round, and sawdust was placed after them.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank from the Mazandaran Wastewater Company for financially supporting and Faculty of health of the Mazandaran Medical Science University for collaboration of this research project (Project No: 2551/150).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors would like to declare that there is no conflict of interest with this research and in the publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Głąb T, et al. Effects of co-composted maize, sewage sludge, and biochar mixtures on hydrological and physical qualities of sandy soil, in Geoderma. Elsevier BV. 2018:27–35.

- 2.Komilis D, Kontou I, Ntougias S. A modified static respiration assay and its relationship with an enzymatic test to assess compost stability and maturity. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102(10):5863–5872. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu L-A, et al. High-rate composting of barley dregs with sewage sludge in a pilot scale bioreactor. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99(7):2210–2217. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosquera-Losada MR, Muñoz-Ferreiro N, Rigueiro-Rodríguez A. Agronomic characterisation of different types of sewage sludge: Policy implications. Waste Manag. 2010;30(3):492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fountoulakis MS, et al. Fate and effect of linuron and metribuzin on the co-composting of green waste and sewage sludge. Waste Manag. 2010;30(1):41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hait S, Tare V. Optimizing vermistabilization of waste activated sludge using vermicompost as bulking material. Waste Manag. 2011;31(3):502–511. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith S. A critical review of the bioavailability and impacts of heavy metals in municipal solid waste composts compared to sewage sludge. Environ Int. 2009;35(1):142–156. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Białobrzewski I, et al. Model of the sewage sludge-straw composting process integrating different heat generation capacities of mesophilic and thermophilic microorganisms. Waste Manag. 2015;43:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2015.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulikowska D, Sindrewicz S. Effect of barley straw and coniferous bark on humification process during sewage sludge composting. Waste Manag. 2018;79:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2018.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hao Z, Yang B, Jahng D. Spent coffee ground as a new bulking agent for accelerated biodrying of dewatered sludge. Water Res. 2018;138:250–263. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meng L, et al. Improving sewage sludge composting by addition of spent mushroom substrate and sucrose. Bioresour Technol. 2018;253:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang D, et al. Performance of co-composting sewage sludge and organic fraction of municipal solid waste at different proportions. Bioresour Technol. 2018;250:853–859. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu Z, et al. The distinctive microbial community improves composting efficiency in a full-scale hyperthermophilic composting plant. Bioresour Technol. 2018;265:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai L, et al. Bacterial communities and their association with the bio-drying of sewage sludge. Water Res. 2016;90:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikaeen M, et al. Respiration and enzymatic activities as indicators of stabilization of sewage sludge composting. Waste Manag. 2015;39:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2015.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yañez R, Alonso JL, Díaz MJ. Influence of bulking agent on sewage sludge composting process. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100(23):5827–5833. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roca-Perez L, et al. Composting rice straw with sewage sludge and compost effects on the soil–plant system. Chemosphere. 2009;75:781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ponsá S, Pagans E, Sánchez A. Composting of dewatered wastewater sludge with various ratios of pruning waste used as a bulking agent and monitored by respirometer. Biosyst Eng. 2009;102(4):433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2009.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang S, et al. Effectiveness of bulking agents for co-composting penicillin mycelial dreg (PMD) and sewage sludge in pilot-scale system. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;23(2):1362–1370. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-5357-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai C-H, Chen K-S, Wang H-K. Influence of rice straw burning on the levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in agricultural county of Taiwan. J Environ Sci. 2009;21(9):1200–1207. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(08)62404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo R, et al. Effect of aeration rate, C/N ratio and moisture content on the stability and maturity of compost. Bioresour Technol. 2012;112:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.02.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tao J, et al. Composition of waste sludge from municipal wastewater treatment plant. Procedia Environ Sci. 2012;12:964–971. doi: 10.1016/j.proenv.2012.01.372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alidadi H, Parvaresh AR. Combined Compost and Vermicomposting Process in The Treatment and Bioconversion of Sludge. Iran J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2005;2(4). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Zazouli MA, D.S . Solid waste & compost Sampling and analysis Guideline. Tehran: Avaye ghalam; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mori T, Narita A. Composting of municipal sewage sludge mixed with rice hulls. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 1981;27(4):477–486. doi: 10.1080/00380768.1981.10431303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parvaresh A, Shahmansouri MR, Alidadi H. Determination of carbon/nitrogen ratio and heavy metals in bulking agents used for sewage composting. Iran J Public Health. 2004;33:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cai Q-Y, et al. Concentration and speciation of heavy metals in six different sewage sludge-composts. J Hazard Mater. 2007;147(3):1063–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.01.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rihani M, et al. In-vessel treatment of urban primary sludge by aerobic composting. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101(15):5988–5995. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ammari T. Composting sewage sludge amended with different sawdust proportions and textures and organic waste of food industry – assessment of quality. Environ Technol. 2012;33(14):1641–1649. doi: 10.1080/09593330.2011.641589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gea T, et al. Optimal bulking agent particle size and usage for heat retention and disinfection in domestic wastewater sludge composting. Waste Manag. 2007;27(9):1108–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zorpas AA, Loizidou M. Sawdust and natural zeolite as a bulking agent for improving quality of a composting product from anaerobically stabilized sewage sludge. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99(16):7545–7552. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Omrani GA. Management Collection Transportaton Sanitary Landfill Composting. Tehran: Azad University scientific publishings center; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tchobanglous G, Teisn H, Vigil S. Integrated Solid Waste Management: Engineering principles and management issues. 1. Tehran: Khaniran; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang D, et al. Co-biodrying of sewage sludge and organic fraction of municipal solid waste: role of mixing proportions. Waste Manag. 2018;77:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asgharzadeh F, et al. Evaluation of cadmium, Lead and zinc content of compost produced in Babol composting plant. Iranian Journal Of Health Sciences. 2014;2(1):62–67. doi: 10.18869/acadpub.jhs.2.1.62. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang X, et al. Nutrient Removal in Pilot-Scale Constructed Wetlands Treating Eutrophic River Water: Assessment of Plants, Intermittent Artificial Aeration and Polyhedron Hollow Polypropylene Balls. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2008;197(1–4):61–73. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Picard CR, Fraser LH, Steer D. The interacting effects of temperature and plant community type on nutrient removal in wetland microcosms. Bioresour Technol. 2005;96(9):1039–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang JI, Hsu T-E. Effects of compositions on food waste composting. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99(17):8068–8074. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar M, Ou Y-L, Lin J-G. Co-composting of green waste and food waste at low C/N ratio. Waste Manag. 2010;30(4):602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moretti SML, Bertoncini EI, Abreu-Junior CH. Composting sewage sludge with green waste from tree pruning. Sci Agric. 2015;72(5):432–439. doi: 10.1590/0103-9016-2014-0341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mokhtari M, et al. Evaluation of Stability Parameters in In-Vessel Compositing of Municipal Solid Waste.Iran. J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2011;8(4):325–332.

- 42.Nafez A, Nikaeen M. Evaluation of Stability and Maturity Parameters in Wastewater Sludge Composting with Different Aeration on Strategies and a Mixture of Green Plant Wastes as Bulking Agent. Fresenius Environ Bull:PSP 2015. 24.

- 43.Dumontet S, Dinel H, Baloda S. Pathogen reduction in sewage sludge by composting and other biological treatments. Biol Agric Hortic. 1999;16:409–430. doi: 10.1080/01448765.1999.9755243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramirez Coutiño V, et al. Evaluation of the composting process in digested sewage sludge from a municipal wastewater treatment plant in the city of San Miguel de Allende, Central Mexico. Rev Int Contam Ambie. 2013;29:89–97. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edrissbazrafshan, et al. Co-composting of dewatered sewage sludge with sawdust. Pak J Biol Sci. 2006;9(8):1580–1583. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2006.1580.1583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Navarro I, Jiménez B. Evaluation of the WHO helminth eggs criteria using a QMRA approach for the safe reuse of wastewater and sludge in developing countries. Water Sci Technol. 2011;63(7):1499–1505. doi: 10.2166/wst.2011.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Villaseñor J, Rodríguez L, Fernández FJ. Composting domestic sewage sludge with natural zeolites in a rotary drum reactor. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102(2):1447–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang L, Sun X. Changes in physical, chemical, and microbiological properties during the two-stage co-composting of green waste with spent mushroom compost and biochar. Bioresour Technol. 2014;171:274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.08.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.An C-J, et al. Performance of in-vessel composting of food waste in the presence of coal ash and uric acid. J Hazard Mater. 2012;203-204:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meunchang S, Panichsakpatana S, Weaver RW. Co-composting of filter cake and bagasse; by-products from a sugar mill. Bioresour Technol. 2005;96(4):437–442. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zazouli MA, et al. Evaluation of cow manure effect as bulking agent on concentration of heavy metals in municipal sewage sludge vermicomposting. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2015;25(124):152–69.

- 52.Shamuyarira K, Gumbo J. Assessment of heavy metals in municipal sewage sludge: a case study of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(3):2569–2579. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110302569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zorpas AA, Inglezakis VJ, Loizidou M. Heavy metals fractionation before, during and after composting of sewage sludge with natural zeolite. Waste Manag. 2008;28(11):2054–2060. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aghili SM, et al. Heavy metal concentrations in dewatered sludge of wastewater treatment Plant in Sari, Iran. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2019;28(170):152–9.