Abstract

Emission characteristics of volatile organic compounds (VOC) emitted from the tank farm of petroleum refinery were evaluated in this study in order to analyze for the potential impacts on health and odor nuisance problems. Estimation procedures were carried out by using the U.S.EPA TANK 4.0.9d emission model in conjunction with direct measurements of gas phase of each stored liquid within aboveground storage tanks. Results revealed that about 61.12% of total VOC emitted from the tank farm by volume were alkanes, in which pentane were richest (27.4%), followed by cyclopentane (19.22%), propene (19.02%), and isobutene (14.22%). Mostly of pentane (about 80%) were emitted from the floating roof tanks contained crude oil corresponded to the largest annual throughput of crude oil as compared with other petroleum distillates. Emission data were further analyzed for their ambient concentration using the AERMOD dispersion model in order to determine the extent and magnitude of odor and health impacts caused by pentane. Results indicated that there was no health impact from inhalation of pentane. However, predicted data were higher than the odor threshold values of pentane which indicated the possibility of odor nuisance problem in the vicinity areas of the refinery. In order to solve this problem, modification of the type of crude oil storage tanks from external floating roof to domed external floating roof could be significant success in reduction of both emissions and ambient concentrations of VOC from petroleum refinery tank farm.

Keywords: AERMOD, Emission, Petroleum refinery, Storage tank, VOC

Introduction

Volatile organic compounds (VOC) are the group of hydrocarbons which currently play an important role as air pollutants in both urban and industrial environments. Some VOC such as benzene, 1,3-butadiene, vinyl chloride, trichloroethylene are considered to have harmful effects on human health, causing acute and chronic poisoning [8, 14, 23]. As for environmental impact, some VOC are served as precursors to ozone, and causing the tropospheric ozone pollution [5].

Petroleum refinery is one of the major industrial source of VOC. Carletti and Giovanni [4] and Wei et al. [35] reported that mostly of VOC were released from the production processes and storage tanks. Emissions from storage tanks can be occurred during filling of the liquid into the tank (refer to filling loss of working loss, Lw) and from the volatilization of the compounds storage in the tank (refer to breathing loss or standing loss, Ls) [22]. Major emission mechanisms caused the standing loss are expansion and contraction of vapor resulted from weather conditions (mostly from changing of ambient temperature and pressure) [2, 3]. The working loss can occur during both of the liquid filling and emptying from the tank. The storage tank release VOC when the vapor pressure within the tank are higher than the relief pressure level caused by rising of storage liquid level of the tank (working loss). During emptying of the tank, the organic vapors are expanded and saturated. Emissions are occurred when the vapor space are greater than their capacities ([18, 33]). Loss of VOC from the storage tanks not only lead to a reduction in the raw materials and products [10, 22] but also give adverse impacts as pollutants in the atmosphere. With regard to this fact, it is necessity to understand the characteristics of VOC emitted in order to find the appropriate measures to reduce the losses and to control the emissions [6, 17, 35, 36]. For example, Wei et al. [35] studied the characteristics of VOC emitted from the petroleum refinery plant and found that 80% of total VOC were attributed by alkanes. Propane was found as the richest compound with the volume mixing ratio of 15.3%, followed by n-butane (11.0%), ethane (9.6%), isobutane (8.4%), n-pentane (6.6%), isopentane (5.8%), and n-hexane (4.7%), respectively. Jovanovic et al. [13] used the US,EPA TANKS model to evaluate the reduction of total VOC emissions under different types of storage tanks and found that total VOC and benzene emissions can be decreased up to 37.6% and 62.7% by changing the storage tank from fix-roof type to floating-roof type. Lu et al. [18] compared the standing loss and working loss from vertical fixed-roof tanks contained p-xylene with measured data. It was found that the calculated LW were well agree with the measured values than the estimated LS. Howari [10] used AERMOD model to evaluate spatial dispersion of VOC from the tank farm under various emission scenarios and found using high performance sealing was the best measure to control VOC emission. In this study, the emission of VOC emitted from storage tanks of the largest petroleum refinery in Thailand were calculated using the U.S.EPA TANKS 4 model. These emissions were used as an input to evaluate the spatial distribution of VOC concentrations in the vicinity of the refinery. Predicted concentrations were further interpreted for potential health impacts and odor nuisance to the communities. The appropriate mitigation measure to reduce those potential impacts were discussed. This study can be served as a tool for management of VOC emissions and concentrations from tank farm of petroleum refineries and petrochemical industries.

Methodology

Study area

The study area is located in Chonburi province (about 81 km East of Bangkok, Thailand). Total area of the refinery is approximately 326.88 ha. The major petroleum products are liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), gasoline, diesel, kerosene and fuel oil. Location of the refinery is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study area

Characteristics of VOC in aboveground storage tank

Direct measurement of gas phase VOC inside the above ground storage tanks were conducted in order to determine their types and concentrations. Totally, they were 63 storage tanks in this refinery. Among them, 9 storage tanks were selected for air samplings. These tanks were chosen to represent the tanks contained different storage liquids in the refinery as show in Table 1. The gas samples within each liquid storage tank were collected into the Tedlar sampling bags. The collected samples were then transferred to the pre-cleaned 6 Liters canister (Entech, USA) at the laboratory prior their analysis. Concentration of individual VOC were quantified following the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s TO-15 standard method [30]. Sample from each canister was loaded into a pre-concentration system (Entech 7200, USA). They were then introduced to a Gas Chromatography (GC) system (Agilent 7890B). Individual compounds were separated using chromatographic temperature programming and detected by a mass spectrometer (MS) system (Agilent 5977A). Target VOC were identified and quantified by using the specific retention time and peak area of the corresponding standard [21]. Peak area was used to quantified the amount of each compound by preparing the calibration curves using different concentrations of VOC standard gases [28].

Table 1.

Characteristics of Vapor in the storage tanks

| No. | Storage liquid | Number of tank | Composition in vapor (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | JET | 6 | Density of vapour 730 kg/m3, 35% Pentane, 33% Cyclopentane, 11.4% Cyclohexane |

| 2. | Heavy vacuum gas oil | 2 | Density of vapour 800 kg/m3, 40.8% Propene, 18.7% Pentane, 14.2% Isobutene |

| 3. | Gasoil | 14 | Density of vapour 740 kg/m3, 32.3% Pentane, 30.4% Cyclopentane, 9.7% Cyclohexane |

| 4. | Kerosene | 3 |

Density of vapour 730 kg/m3, 32% Cyclopentane, 27.3% Pentane, 12.2% Cyclohexane |

| 5. | Crude oil | 16 | Density of vapour 480 kg/m3, 41.3% Pentane, 17% Cyclopentane, 13.4% Propene |

| 6. | Crude slop | 2 | Density of vapour 480 kg/m3, 28.4% Pentane, 17% Cyclopentane, 16% Propene |

| 7. | Fuel oil | 9 | Density of vapour 740 kg/m3, 31.9% Isobutene, 31.7% Propene, 14.6% Pentane |

| 8. | High speed diesel oil | 2 | Density of vapour 740 kg/m3, 34% Pentane, 22.7% Cyclopentane, 16.8% Cyclohexane |

| 9. | Unleaded gasolene | 9 | Density of vapour 620 kg/m3, 44.6% Pentane, 31.3% Cyclopentane, 5.25% Isobutene |

Quality control and quality assurance

Before sampling, Tedlar bags were cleaned by pressurizing with humidified nitrogen and analyzed as blank samples to confirm their cleanliness. Air sampling was performed through a vent of tank by pumping air. After sampling, the air samples in the Tedlar bags were transferred to canister for analysis within 48 h at the laboratory. All canisters were cleaned by filling and evacuating with humidified zero air. Samples were collected firstly in the Tedlar bags before transferring to canisters because the sampling procedure require that the air samples have to be drawn through the heated sampling line to remove moisture and control of the flow rate of the sampling from emission sources which is the limitation of canister sampling system. They were then transferred into pre-concentrator in order to remove moisture, CO2 and other gaseous impurities prior to being analyzed [25]. The sample was analyzed for speciated VOCS concentrations by using Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometer (GC/MS) according to the U.S. EPA Method 15.

Emission inventory

Emission of total VOC released from the fixed and floating roof storage tanks of the refinery were calculated based on the equations used in U.S.EPA TANKS 4.0.9d model. Calculations of emissions were followed the AP-42 section 7.1 Organic liquid storage tanks [33]. Major parameters used in the calculation include vapor pressure, molecular weight of the product, tank characteristics, diurnal temperature, paint factor, tank capacity, and number of turnovers [10].

Annual emissions of total VOC were calculated for each storage tank. These data were used together with VOC profile from the direct measurements to determine the amount of individual VOC species emission.

AERMOD model and its configuration

The dispersion of VOC emissions from aboveground storage tanks are simulated by AERMOD dispersion model. This model was intensively validated and tested for its accuracy in the Eastern region of Thailand where the study area is [12, 15, 19, 26, 27, 29, 34]. Toxic concentrations and odor impacts of pentane at the receptors were estimated by using AERMOD. The AERMOD modelling system used in this study was simulated with a commercial interface, AERMOD View (Version 9.5) (Lakes Environmental Software, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada). It is a steady-state Gaussian plume model properly used to refine dispersion of concentrations for simple and complex terrain for receptors within 50 km of a modelled source [20]. AERMOD has been widely applied for simulating pollutants and evaluating dispersion on the ambient air quality [1, 7, 11, 27]. The model supposes the concentration distribution to be Gaussian in both the vertical and horizontal. In the convective boundary layer (CBL), the horizontal distribution is also assumed to be Gaussian, but the vertical distribution is described with a Bi-Gaussian probability density. AERMOD consists of two pre-processors, AERMET and AERMAP [31, 32]. Region between the earth’s surface and the overlying, free flowing (geostrophic) atmosphere is defined as the atmospheric boundary layer. The fluxes of heat and momentum drive the growth and structure of this boundary layer. The depth of this layer, and the dispersion of pollutants within it, are influenced on a local scale by surface characteristics [31, 32]. The AERMOD meteorological preprocessor (AERMET) deals with the surface characteristics of the land surrounding the site together with the hourly surface meteorological data to produce the parameters that affect dispersion, such as albedo (portion of sunlight that is reflected), Bowen ratio (a measure of moisture available for evaporation), and surface roughness length for dispersion calculations in AERMOD. In this study, local surface characteristics were used as one of the crucial input data for model simulation. The surface roughness length, Bowen ratio and albedo were calculated based on the land-use characteristics obtained from the land-use map of the Department of Land Development of Thailand. Land-use types (e.g., urban area, deciduous/coniferous forest, cultivated land, calm waters) and their seasonal variations were considered covered an area of 25 × 25 km2 (625 km2) from the refinery. In this study, sectors for surface characteristics were defined as a 45-degree arc. A weighted average of characteristics by surface area within a 45-degree sector was used to represent a unique portion of the surface significantly influence the properties of the sector that it occupies. The land-use characteristics were also used to calculate geometric mean of the Bowen ratio covering a modeling domain of 14 × 14 km2 (0.21 for wet season and 0.40 for dry season). The albedo calculated in the same modeling domain with Bowen ratio was 0.14 (arithmetic mean).

The terrain preprocessor (AERMAP) uses gridded terrain data to calculate receptor and source elevation data and terrain height scale that are used by AERMOD when calculating air pollutant concentrations [7, 31, 32]. The terrain is characterized by the terrain pre-processor (AERMAP) which also generates receptor grids. Gridded terrain data are used to model the area, where the gridded elevation data is made available to AERMAP in the form of a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data. These data also prove useful when the associated representative terrain influence height has to be calculated for each receptor location. Thus, elevations for both discrete receptors and receptor grids are computed by the terrain pre-processor. Topographical characteristics of the study domain are derived from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM3/SRTM1) with a resolution of 3-arc sec (90 × 90 m2). The 1-years (1st January 2015 to 31st December 2015) meteorological data used in this study were generated by WRF model. The Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) Model computed planetary boundary layer and surface layer parameters required by AERMOD. Planetary boundary layer and surface layer parameters were not directly used due to the absence of local meteorological observations at an hourly interval in the study area. WRF is a mesoscale numerical weather prediction system designed to apply to both meteorological research and numerical weather prediction needs [9]. The model has the ability to simulate and forecast, followed by producing a meteorological profile that reflects either real data or ideal data of the atmospheric condition [16]. This model can generate gridded meteorological parameters horizontally and vertically for a region. In this study, WRF, version 3.7, was configured using a domain with 12-km grid spacing. A total of 27 vertical layers were used. The initial conditions (IC) and lateral boundary conditions (LBC) for the WRF simulation originated from the NARR, which is available every 3 h at a 32-km spatial resolution. The model was initialized every day at 0600 UTC. The physics options used in the WRF runs included WRF Single-Moment (WSM) 5/6-class for microphysics, Yonsei University for Planetary Boundary Layer, Noah for Land-surface model, RRTM/Eta Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory for longwave radiation and MM5 for shortwave radiation schemes and many other combinations. Time-varying sea surface temperature and combined grid-observational nudging were also included in a configuration for WRF simulation. In this study, the surface and upper air meteorology was simulated by WRF model (version 3.7) for a three nested domains with horizontal grid spacing varying from 12 km, 4 km, and 1 km.

Hourly emission rates of pentane calculated from emission equations based on U.S.EPA TANK 4.0 model were used as input data to predict its maximum ground level concentration and spatial distributions over the study domain. AERMOD were simulated to predict the highest 1-h and annual average concentrations of pentane. Predicted annual concentrations were also used to evaluate the extent and magnitude of health impact caused by exposure of pentane emitted from the tank farm. Maximum predicted hourly average concentrations were used to explain the possibility of odor impact caused by pentane in the modeling domain.

Results and discussion

Chemical compositions of vapor in the storage tank

Direct measurements of vapor in the storage tank for each liquid type were conducted. Quantitative and qualitative analysis were carried out following U.S.EPA TO15. Duplicate samplings were performed for each tank and the duplicate analysis was conducted for each samples. Average concentrations of each chemical from different types of petroleum products obtained from the measurements are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Chemical compositions of vapor in the storage tank, (unti: ppbv)

| Chemical name | JET | Heavy vacuum gas oil | Gasoil | Kerosene | Crude oil | Crude slop | Fuel oil | High speed diesel | Unleaded gasoline | SUM | Contribution (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propene | 455 | 8368 | 620 | 96 | 2814 | 2615 | 12,116 | 1265 | 874 | 29,223 | 18.30 |

| Isobutene | 188 | 2906 | 188 | 91 | 1204 | 1228 | 12,185 | 1091 | 929 | 20,010 | 12.53 |

| Pentane | 4865 | 3833 | 2385 | 1219 | 8671 | 4623 | 5562 | 6987 | 7885 | 46,030 | 28.82 |

| Isoprene | 2.7 | 5.0 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 3.5 | 12.9 | 41 | 0.03 |

| Isopropyl alcohol | 143 | 24 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 11 | 4.2 | 7.5 | 4.2 | 13 | 219 | 0.14 |

| Dichloromethane | 77 | 140 | 65 | 70 | 74 | 68 | 70 | 70 | 58 | 692 | 0.43 |

| Cyclopentane | 4504 | 2637 | 2248 | 1433 | 3609 | 2777 | 3564 | 4666 | 5535 | 30,973 | 19.39 |

| Propane, 2-Methoxy-2-Methyl (MTBE) | 12 | 2.7 | 8.0 | 4.3 | 0.0000 | 0.31 | 0.62 | 0.39 | 154 | 182 | 0.11 |

| Hexane | 837 | 568 | 479 | 422 | 1074 | 1128 | 1078 | 1205 | 592 | 7383 | 4.62 |

| Methacrolein | 4.1 | 7.0 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 7.1 | 6.0 | 4.5 | 48 | 0.03 |

| 1-Propanol | 5.1 | 13 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 5.2 | 7.7 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 56 | 0.04 |

| Butanal | 73 | 27 | 25 | 17 | 45 | 35 | 56 | 49 | 44 | 371 | 0.23 |

| Methyl vinyl ketone | 716 | 593 | 445 | 338 | 1040 | 1110 | 1065 | 1470 | 515 | 7292 | 4.57 |

| Chloroform | 3.9 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 11 | 12 | 18 | 12 | 5.1 | 67 | 0.04 |

| Cyclohexane | 1555 | 1055 | 719 | 545 | 2199 | 2421 | 2181 | 3466 | 828 | 14,969 | 9.37 |

| Benzene | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0.00 |

| 1,2-Dichloroethane | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0.00 |

| 1,2-Dichloropropane | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 3.6 | 0.0000 | 6.3 | 0.0000 | 8.4 | 10.6 | 3.2 | 32 | 0.02 |

| Toluene | 27 | 46 | 33 | 23 | 27 | 19 | 24 | 17 | 30 | 246 | 0.15 |

| 1,1,2-Trichloroethane (Vinyl Trichloride) | 82 | 61 | 46 | 67 | 110 | 113 | 110 | 114 | 63 | 766 | 0.48 |

| 3-Hexanone | 47 | 43 | 27 | 34 | 17 | 31 | 29 | 41 | 40 | 309 | 0.19 |

| Hexanal | 25 | 28 | 18 | 16 | 28 | 23 | 28 | 23 | 21 | 210 | 0.13 |

| Ethylbenzene | 3.4 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 3.4 | 16 | 0.01 |

| m/p-Xylene | 15 | 21 | 13 | 11 | 8.0 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 16 | 107 | 0.07 |

| o-Xylene | 7.9 | 10 | 6.3 | 5.4 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 7.8 | 50 | 0.03 |

| Styrene | 15 | 31 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 152 | 0.10 |

| 1,3,5-Trimethylbenzene | 8.2 | 14 | 7.5 | 7.2 | 6.3 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.1 | 8.6 | 70 | 0.04 |

| 1,2,4-Trimethylbenzene | 13 | 22 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 14 | 113 | 0.07 |

| 1,2,3-Trimethylbenzene | 9.4 | 17 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 8.2 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 10 | 86 | 0.05 |

| Total | 159,715 | 100 | |||||||||

Generally, there were 7 compounds dominantly found in every type of liquid stored in the refinery. They were pentane, cyclopentane, propene, isobutene, cyclohexane, hexane and methyl vinyl ketone. Pentane was the most abundant compound mainly found in the storage tank contained jet fuel, gasoil, crude oil, crude slop, high speed diesel oil and unleaded gasoil. Moreover, major compositions of heavy vacuum gas oil and fuel oil were consisted of propene and isobutene. Generally, fraction of chemical compositions of vapor in the storage tank were similar with percentage of major compounds found in their liquid phase. Highest concentrations of VOC were measured from the storage tank contained fuel oil, crude oil, high speed diesel oil and heavy vacuum gas oil, respectively. On the other hand, low concentrations of VOC in vapor where found in the storage tanks contained kerosene and gasoil. Overall characteristics of VOC profile released from the storage tanks in refinery are summarized in Table 3. It was found that about 61.12% of VOC emitted from the storage tank were contributed by alkanes following by alkenes (33.26%).

Table 3.

Group of VOC compound emission from storage tank of petroleum refinery

| Group of compound | Contribution (%) | Major contributed compound |

|---|---|---|

| Alkane | 61.12 | Pentane (27.40%), Cyclopentane (19.22%), Cyclohexane (8.9%) |

| Alkene | 33.26 |

Propene (19.02%), Isobutene (14.22), Isoprene (0.027) |

| Ketone | 4.60 | Methyl vinyl ketone (4.41%), 3-Hexanone (0.19%) |

| Aromatic | 0.54 |

Toluene (0.16%), Styrene (0.1%), 1,2,4-Trimethylbenzene (0.074%) |

| Aldehyde | 0.40 |

Butanal (0.23%), Hexanal (0.13), Methacrolein (0.03%) |

| Alcohol | 0.04 | 1-Propanol (0.04%) |

| Chlorinated hydrocarbon | 0.04 | Chloroform (0.04%) |

| Total | 100.00 |

Emission factors

Results from direct measurements of VOC concentrations in the vapor of storage tanks clearly indicated that pentane was the most abundant compound among measured VOC. Therefore, pentane was selected for further intensive analysis in this study. Emissions of pentane from organic liquid in 63 storage tanks were predicted by U.S.EPA AP-42 estimation equations. Results were presented in Table 4. Total pentane emission was estimated as 309.78 kg/y. About 80.5% of the total pentane emissions from the refinery tank farm were from crude oil tanks. High emission from crude oil tanks were relevant to the largest annual throughput of crude oil stored in the refinery as compared with other petroleum distillates.

Table 4.

Contribution of pentane emissions from storage tank of petroleum refinery

| No. | Storage liquid | Tank type | Number of tank | Total throughput (103 m3/y) | Pentane emission (kg/y) | Contribution (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Crude oil | Floating roof | 16 | 15,530.27 | 249.51 | 80.54 |

| 2. | Unleaded gasoline | Floating roof | 9 | 2845.26 | 48.49 | 15.67 |

| 3. | Crude slop | Floating roof | 2 | 348.25 | 9.34 | 3.015 |

| 4. | JET | Fixed roof | 6 | 3313.56 | 1.17 | 0.37 |

| 5. | Gasoil | Fixed roof | 14 | 7468.82 | 0.79 | 0.26 |

| 6. | Fuel oil | Fixed roof | 9 | 1389.41 | 0.21 | 0.06 |

| 7. | Kerosene | Fixed roof | 3 | 147.083 | 0.21 | 0.07 |

| 8. | High speed diesel oil | Fixed roof | 2 | 959.70 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| 9. | Heavy vacuum gas oil | Fixed roof | 2 | 16.49 | 0.000008 | 0.0000025 |

| Total | 63 | 31,885.81 | 309.78 | 100.00 | ||

Dispersion modeling results

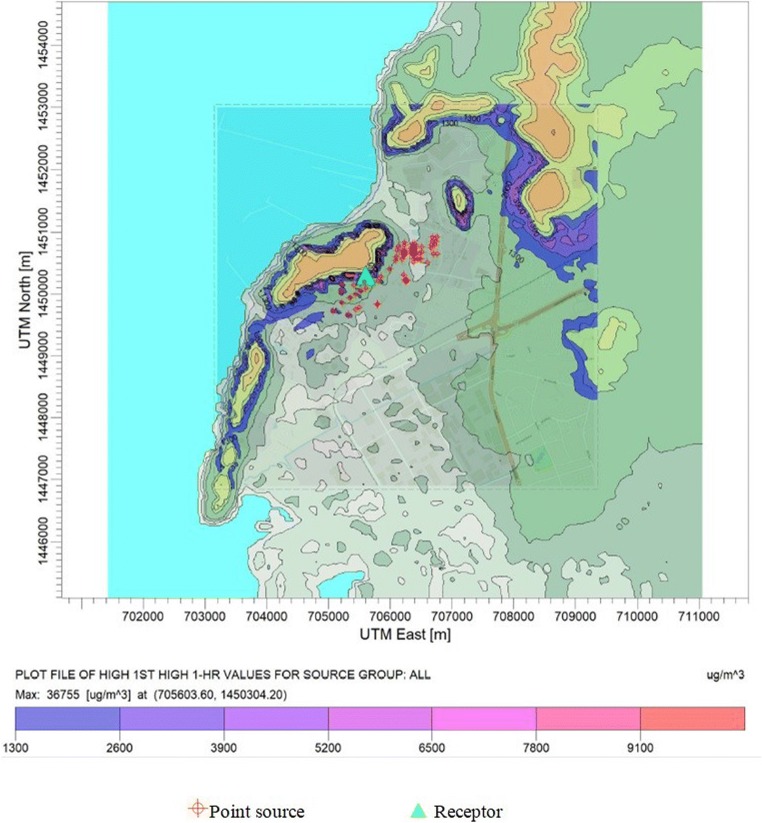

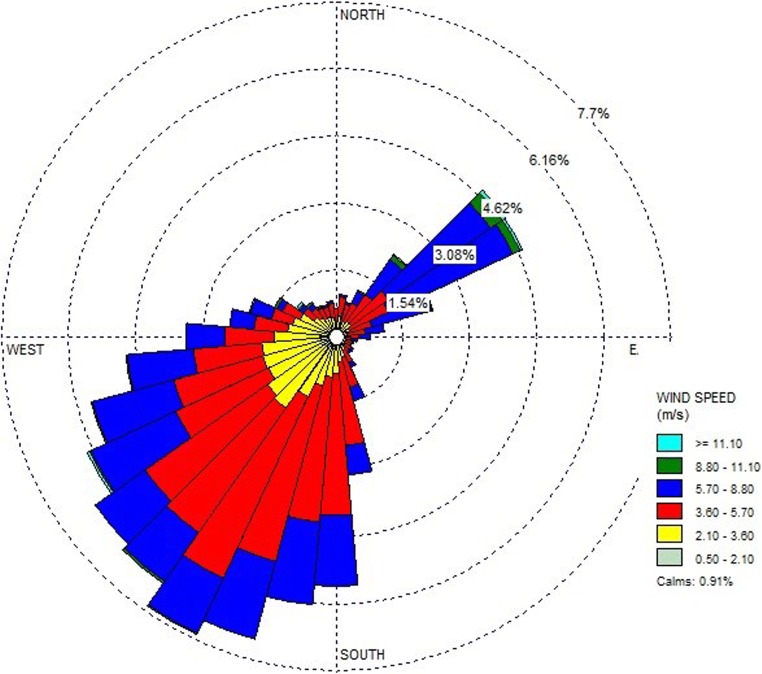

AERMOD was applied to simulate the highest ambient ground level concentration on 1-h and annual average of pentane to the area surrounding the refinery facility. Ambient concentrations of pentane were predicted for a period of 8760 h equivalent to 1 year using hourly synoptic meteorological data of the year 2015. In order to evaluate odor occurrence, the highest values of 1-h average concentrations were analyzed as illustrated in Fig. 2. The highest predicted ground level concentration was 36,755 μg/m3 exceeding the odor threshold of 6492 μg/m3. This peak’s concentration was predicted close to pentane major source (Crude oil tank). High predicted concentrations were also predicted at the hills located in the modeling domain which indicated the influence of elevation of topographical characteristics to the predicted concentrations. It should be discussed that spatial distributions of ambient ground level concentrations were also relevant to wind characteristics in the study area. This is due to the fact that AERMOD has been developed base on the Gaussian plume dispersion. Predicted ground level concentrations are directly relevant to the base elevation of the receptors. As for the wind directions, spatial distribution of the maximum 1-h concentrations illustrated in Fig. 2 indicated that high concentrations were found in relevant with the prevailing winds (southwestern and northeastern directions) presented as wind rose diagram as shown in Fig. 3. Sirithian et al. [24] also reported similar finding which indicated that the major factors governed the possibility of high concentrations of air pollution were topographical characteristics and wind directions.

Fig. 2.

Plot file of the highest 1-h average pentane concentration (unit: μg/m3)

Fig. 3.

Wind rose diagram of the year 2015

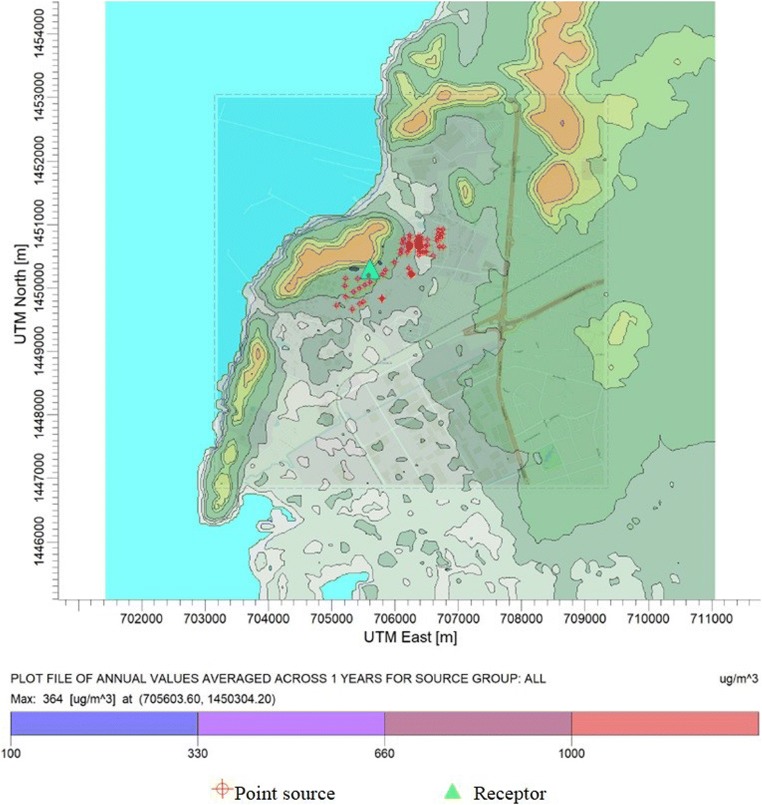

Together with odor analysis, we further analyzed the possibility of health impact caused by pentane emission from the refinery. Predicted annual concentrations of pentane in the study domain were compared with the Provisional Peer Reviewed Toxicity Value (PPRTV) of pentane established by U.S.EPA. Spatial distribution of predicted annual pentane concentration is illustrated in Fig. 4. Results indicated that the highest annual concentration was predicted as 364 μg/m3. This level was not exceeding the PPRTV value of pentane (1000 μg/m3). Therefore, the risk from inhalation exposure of pentane emitted from this refinery could be considered as low level. It should be noted that the ambient ground level concentrations used in this analysis were obtained from the simulation of air model. There were no direct measurements downstream of the tanks. Therefore, the effort to quantify concentrations of interested VOC using both modelling and measuring data prior and after implementations of any mitigation measures will be very much useful information to determine the success of those measures.

Fig. 4.

Plot file of annual values averaged pentane concentration (unit: μg/m3)

Conclusions

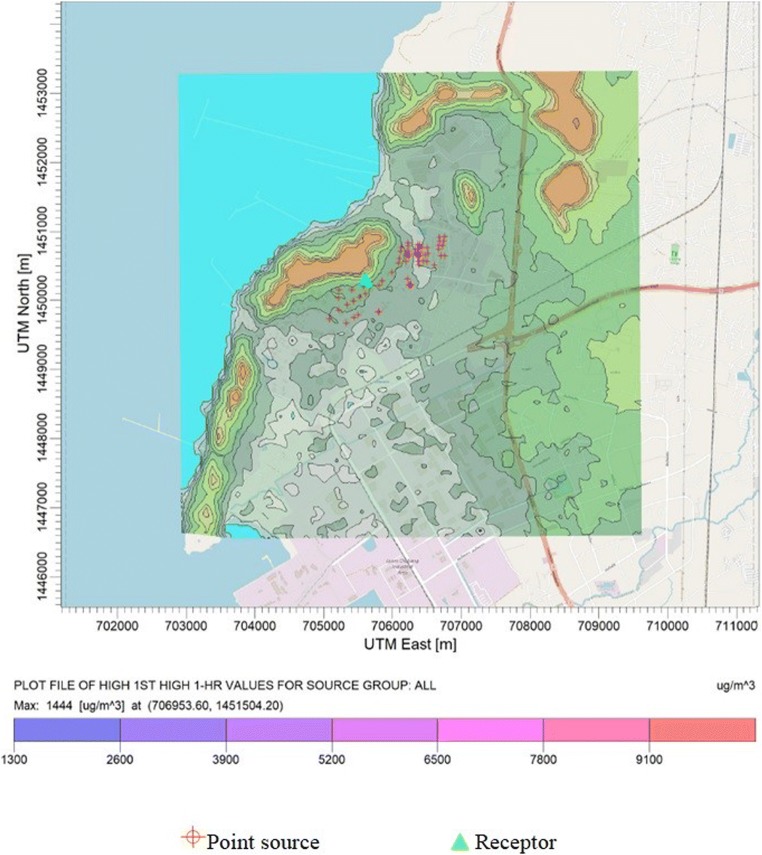

The storage tanks have been considered as the remarkable source of volatile organic compounds (VOC) emitted from the petroleum refinery. Profiles of VOC emitted from the tank farm of refinery were evaluated using both direct measurements and emission factor calculations. Alkanes were found as the most abundant VOC released from the tank farm of the refinery. Their emissions were mostly contributed by pentane. The storage tanks which contained crude oil were found as the major emission source of pentane (about 80% of total pentane emission) due to their largest annual throughput. Pentane emissions were further used as input data to predict for their ground level concentrations using AERMOD dispersion model. Spatial distributions of 1-h average predicted concentration was compared with pentane odor threshold in order to evaluate the occurrence of odor nuisance and health impact caused by the petroleum refinery tank farm. This finding can be used to assist in setting up appropriate mitigation measures to control emissions from the tank farm in order to achieve controlling of odor nuisance from the refinery. To meet this objective, as for example, we further analyzed the benefit of modification of the crude oil storage tank farm from external floating roof to domed external floating roof. As for emission reduction, by implementing this measure, total pentane emission from the tank farm could be reduced up to 96% from its existing value. Ambient concentrations of pentane in the vicinity around the petroleum refinery were also significantly decreased as show in Fig. 5. Highest predicted 1-h average concentrations were not higher than the odor threshold of pentane hence the odor nuisance problem can be well managing by implementing this mitigation measure. This study clearly indicated that understanding of emission characteristics is crucial factor for the management of ambient concentrations of air pollutants. Therefore, it was necessity to evaluate both of the emissions from the sources and the concentrations in the environment when managing air pollution in order to set up appropriate mitigation measures to controlling and managing of emission sources. The emission data acquired under this study can also be used to support the evaluation of emission rate from petroleum refinery storage tanks for the Pollutant Release and Transfer Registration (PRTR) system which several governments and international organizations currently attempt to use as a tool to support the voluntary emission reduction of pollutants particularly in the developing countries.

Fig. 5.

Predicted 1-h average concentration of pentane (after modification of crude oil tanks)

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted in collaboration with the Environmental Research and Training Center (ERTC) under the Department of Environmental Quality Promotion (DEQP) of Thailand. The authors would like to thank ERTC in providing measurement data from experiments for this analysis. The Ph.D. scholarship was granted by the Research and Researchers for Industries-RRI of The Thailand Research Fund. This study was partially supported for publication by the China Medical Board (CMB), Center of Excellence on Environmental Health and Toxicology (EHT), Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University, Thailand.

Compliance with ethical standards

Declaration

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Highlights

• Characteristics of VOC emissions from petroleum refinery were elucidated.

• Health and odor impacts from VOC losses from refinery tank farm were quantified

• Measure to prevent loss from refinery tank farm and its benefit on environment was illustrated.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abdelrasoul A, Khan AR, Al-Hadad A. Oil refineries emissions impact on urban localities using AERMOD. Am J Environ Sci. 2010;6(6):505–515. doi: 10.3844/ajessp.2010.505.515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckman JR. Breathing losses from fixed-roof tanks by heat and mass transfer diffusion. Ind Eng Chem Process Des Dev. 1984;23(3):472–479. doi: 10.1021/i200026a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beckman JR, Gllmer JR. Model for predicting emissions from fixed-roof storage tanks. Ind Eng Chem Process Des Dev. 1981;20(4):646–651. doi: 10.1021/i200015a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carletti S, Giovanni DN. 9th International Conference on Environmental Engineering. 2014. Evaluation of fugitive emissions of hydrocarbons from a refinery during a significant pollution episode. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cerón-Bretón JG, Cerón-Bretón RM, Kahl JDW, Ramírez-Lara E, Aguilar-Ucán CA, Montalvo-Romero C, Ortínez-Alvarez JA. Carbonyls in the urban atmosphere of Monterrey, Mexico: sources, exposure, and health risk. Air Qual Atmos Health. 2016;10(1):53–67. doi: 10.1007/s11869-016-0408-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang JI, Lin C-C. A study of storage tank accidents. J Loss Prev Process Ind. 2006;19(1):51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jlp.2005.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, Carter KE. Modeling potential occupational inhalation exposures and associated risks of toxic organics from chemical storage tanks used in hydraulic fracturing using AERMOD. Environ Pollut. 2017;224:300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai H, Jing S, Wang H, Ma Y, Li L, Song W, Kan H. VOCS characteristics and inhalation health risks in newly renovated residences in Shanghai, China. Sci Total Environ. 2017;577:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henmi T, Flanigan R, Padilla R. Development and application of an evaluation method for the WRF mesoscale model. Army research laboratory. 2005:ARL–TR3657.

- 10.Howari FM. Evaporation losses and dispersion of volatile organic compounds from tank farms. Environ Monit Assess. 2015;187(5):273. doi: 10.1007/s10661-015-4456-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayadipraja E, Daud A, Assegaf A, Maming M. The application of the AERMOD model in the environmental health to identify the dispersion area of total suspended particulate from cement industry stacks. J Res Med Sci. 2016:2044–9.

- 12.Jittra N, Pinthong N, Thepanondh S. Performance evaluation of AERMOD and CALPUFF air dispersion models in industrial complex area. Air Soil Water Res. 2016;8:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jovanovic J, Jovanovic M, Jovanovic A, Marinovic V. Introduction of cleaner production in the tank farm of the Pancevo oil refinery, Serbia. J Clean Prod. 2010;18(8):791–798. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kampeerawipakorn O, Navasumrit P, Settachan D, Promvijit J, Hunsonti P, Parnlob V, Ruchirawat M. Health risk evaluation in a population exposed to chemical releases from a petrochemical complex in Thailand. Environ Res. 2017;152:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khamyingkert L, Thepanondh S. Analysis of industrial source contribution to ambient air concentration using AERMOD dispersion model. EnvironmentAsia. 2016;9(1):28–36. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar A, Patil R, Dikshit A, Kumar R. Application of WRF model for air quality modelling and AERMOD – a survey. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2017;17:1925–1937. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2016.06.0265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin T-Y, Sree U, Tseng S-H, Chiu KH, Wu C-H, Lo J-G. Volatile organic compound concentrations in ambient air of Kaohsiung petroleum refinery in Taiwan. Atmos Environ. 2004;38(25):4111–4122. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2004.04.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu C, Huang H, Chang S, Hsu S. Emission characteristics of VOC from three fixed-roof p-xylene liquid storage tanks. Environ Monit Assess. 2013;185(8):6819–6830. doi: 10.1007/s10661-013-3067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malakan W, Keawboonchu J, Thepanondh S. Comparison of AERMOD performance using observed and prognostic meteorological data. EnvironmentAsia. 2018;11(2):38–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mokhtar MM, Hassim MH, Taib RM. Health risk assessment of emissions from a coal-fired power plant using AERMOD modelling. Process Saf Environ Prot. 2014;92(5):476–485. doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2014.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niu Z, Zhang H, Xu Y, Liao X, Xu L, Chen J. Pollution characteristics of volatile organic compounds in the atmosphere of Haicang District in Xiamen City, Southeast China. J Environ Monit. 2012;14(4):1145–1152. doi: 10.1039/c2em10884d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rota R, Frattini S, Astori S, Paludetto R. Emissions fromfixed-roof storage tanks: modeling and experiments. Ind EngChem Res. 2001;40:5847–5857. doi: 10.1021/ie010111m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rovira E, Cuadras A, Aguilar X, Esteban L, Borras-Santos A, Zock JP, Sunyer J. Asthma, respiratory symptoms and lung function in children living near a petrochemical site. Environ Res. 2014;133:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sirithian, D., Thepanondh, S., Laowagul, W., & Morknoy. (2017). Atmospheric dispersion of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from open burning of agricultural residues in Chiang Rai, Thailand. Air Qual Atmos Health 10, 861–871.

- 25.Sirithian D, Thepanondh S, Sattler ML, Laowagul W. Emissions of volatile organic compounds from maize residue open burning in the northern region of Thailand. Atmos Environ. 2018;176:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.12.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thawonkaew A, Thepanondh S, Sirithian D, Jinawa L. Assimilative capacity of air pollutants in an area of the largest petrochemical complex in Thailand. Int J of GEOMATE. 2016;11(23):2162–2169. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thepanondh, S., Outapa, P., Saikomol, S. (2016). Evaluation of dispersion model performance in predicting SO2 concentrations from petroleum refinery complex. Int J of GEOMATE, 11(23), 2129–2135.

- 28.Truong SCH, Lee M-I, Kim G, Kim D, Park J-H, Choi S-D, Cho G-H. Accidental benzene release risk assessment in an urban area using an atmospheric dispersion model. Atmos Environ. 2016;144:146–159. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.08.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tunlathorntham S, Thepanondh S. Prediction of ambient nitrogen dioxide concentrations in the vicinity of industrial complex area, Thailand. Air Soil Water Res. 2017;10:1–11. doi: 10.1177/1178622117700906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. EPA: Compendium method TO-15 determination of volatile organic compounds (VOC) in air collected in specially-prepared canisters and analyzed by GC/MS. 1999

- 31.U.S. EPA: AERMOD: description of model formulation. https://www3.epa.gov/scram001/7thconf/aermod/aermod_mfd.pdf (2004a) Accessed 26 June 2018.

- 32.U.S. EPA: User's guide for the AERMOD meteorological preprocessor (AERMET). https://www3.epa.gov/scram001/7thconf/aermod/aermetugb.pdf (2004b) Accessed 26 Jan 2019.

- 33.U.S. EPA: Compilation of air pollutant emission factors AP-42. Fifth ed., vol. 1, chapter 7: Organic liquid storage tanks. https://www3.epa.gov/ttn/chief/ap42/ch07/final/c07s01.pdf (2006) Accessed 26 June 2018.

- 34.U.S. EPA: AERMOD model formulation and evaluation. https://www3.epa.gov/ttn/scram/models/aermod/aermod_mfed.pdf (2018) Accessed 26 June 2018.

- 35.Wei W, Cheng S, Li G, Wang G, Wang H. Characteristics of volatile organic compounds (VOC) emitted from a petroleum refinery in Beijing, China. Atmos Environ. 2014;89:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weli V, Itam NI. Impact of crude oil storage tank emissions and gas flaring on air/rainwater quality and weather conditions in Bonny Industrial Island, Nigeria. Open Journal of Air Pollution. 2016;5:44–54. doi: 10.4236/ojap.2016.52005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]