Abstract

Background

Removal of pentachlorophenol (PCP) from wastewater containing chlorophenols, due to its toxicity, mutagenic and carcinogenic properties, has been attracted much interests of researchers.

Methods

In this research, K10 montmorillonite was modified by silane and imidazole (Im) for increasing the removal percentage of PCP from aqueous solutions. It was characterized by FTIR, XRF, FESEM, EDS, and BET techniques. The influence of different parameters such as initial concentration, contact time, adsorbent dosage, pH, temperature and agitating speed was investigated.

Results

The maximum removal percentage (95%) were obtained for PCP at pH = 4. The isotherm experimental data for pentachlorophenol was best fitted using the Langmuir model and the kinetic studies were better described by the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. The thermodynamic study indicated that the adsorption of PCP by the adsorbent was feasible, spontaneous and exothermic.

Conclusion

In this study, the modified montmorillonite by silane and imidazole is appropriate and low cost adsorbent for increasing of the removal percentage of PCP from aqueous solutions.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40201-019-00414-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pentachlorophenol, Montmorillonite, Removal efficiency, Isotherm and kinetic model

Introduction

In recent years, the increasing development of the industry has caused environmental pollution.The presence of organic compounds in wastewater of the chemical and petrochemical industries is one of the most important environmental challenges [1].

Among the various organic contaminants, chlorophenols are highly toxic and carcinogenic [2]. These compounds are mainly used as fungicides, herbicides, insecticides, pharmaceuticals, paints, preservatives, intermediates, fibers and leathers [3, 4]. The presence of such compounds, even at low concentration, can cause unpleasant taste and smell in drinking water [5]. Pentachlorophenol (PCP) is one of the manufactured chlorinated organic compounds. Owing to its high toxicity and widespread distribution in the environment, it has been listed as a priority pollutant by U.S. Environmental protection Agency (EPA) [6].

According to the recommendation of EPA, the permitted concentration of pentachlorophenol in drinking water is 0.3 μg L−1 [6]. Therefore, its removal from PCP contaminated wastewater is necessary. By considering the above-mentioned facts as well as to prevent and minimize the risks related to PCP, effluent-containing PCP must be treated by an appropriate technique. The performance of various methods has been evaluated for the removal of PCP from contaminated solutions or effluents, including electrochemical oxidation [7], photocatalytic degradation [8], mechanochemical degradation [9], adsorption [10], biological treatment [11], advanced oxidation processes [12], and membrane filtration [13]. Nowadays, the adsorption process is widely used for the removal of recalcitrant organic micro-pollutants such as PCP, due to the convenient design, simple operation, low capital cost, and high removal efficiency [14–16]. A wide variety of materials have been investigated as adsorbents for the removal of pentachlorophenol, such as activated carbon [17], carbon nanotubes [18], activated sludge biomass [19], reed biochar [20], peat–bentonite mixtures [21], pine bark [22], and fungal biomass [23]. Among different adsorbents used to remove PCP from contaminated water, activated carbon has a special place due to its porosity, large surface area, well-developed internal structure, the presence of various functional groups on its surface, and its excellent adsorption capacity. However, high production and regeneration costs are the main disadvantages of activated carbon. Therefore, researchers have paid much attention on the application of low-cost, natural, and environmentally friendly materials to remove pollutants from the environment [24]. In recent years, clay minerals have been widely used as adsorbents for the removal of chemical compounds due to their nontoxicity, high surface area, chemical stability and mechanical property, adsorption capacity, cation exchange capacity [8], low cost, and high efficiency [25]. Nevertheless, clay minerals have a relatively low adsorption capacity for hydrophobic and anionic contaminants due to their negative charge and its surface hydrophilic properties [8].

Montmorillonite (Mt) is a low cost and abundant clay and due to its desirable physical and chemical properties, it is more commonly used as an adsorbent [25]. Mts are layered materials, where each layer is formed by an octahedral central aluminum group between two tetrahedral silicon groups linked together by oxygen atoms [26].

However, due to the presence of the hydration of inorganic cations on the surface, the Mt surface is hydrophilic in nature. For this reason, natural Mt is not a suitable and much effective adsorbent for organic compounds [27]. Therefore, in order to improve the adsorption capacity, it is necessary to change the surface of Mt using organic materials [28]. Organo-functionalization or bonding of silane molecules on the clay surface is one of the modification methods [29]. Adsorption of organic materials by clay modified has been several studied in recent year [30–32].

The advantages of organo clay are high pollutant removal efficiency and it cost effectiveness [28].

In recent years, the silane coupling agent containing silicon compounds have attracted much attention [25]. This process contains the constitution of a covalent bond between the silanol groups from clay minerals with organosilane [33]. On the other hand, changing surface of Mt by silane of agent can increase the hydrophobic and lipophilic properties of the Mt [34].

Hence, in this study, the acid montmorillonite (AMt) with chloropropyl trimethoxy silane (AMt-Cl) following reaction with imidazole (AMt-Cl-Im) was modified. The prepared adsorbent was used to remove pentachlorophenol from aqueous environments. The effect of different operating parameters such as initial PCP concentration, adsorbent dose, contact time, pH of the solution, and agitating speed was also studied.

Material and methods

Materials

PCP (C6HCl5O) of 97% purity was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The original Mt used in this study was purchased from Fluka (USA). Chloropropyl trimethoxysilane, Im, sulfuric acid, dimethylformamide (DMF), toluene, and ethanol were purchase from Merck and used for the modification of the Mt.

Synthesis of organo-modified clay

To prepare the organo-modified clay, a 5 g of the Mt was added to 150 mL distilled water. Afterward, 5 mL of sulfuric acid (˃98%) was added to the mixture and stirred for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the mixture was centrifuged to separate the clay from the solution, and then clay was washed with distilled water and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min. Finally, the solid was dried in an oven at 353 K for 24 h. The Organo-functionalization was performed by resuspending 1.5 g of activated Mt in 30 mL of toluene while a mixture of 5.0 mL of the silane dissolved in xylene was added, and the suspension was refluxed under stirring at 363 K for 48 h. After cooling, the product had filtered and then washed with ethanol and toluene. The solid was dried in an oven at 363 K for 28 h. In the next step, 1 g of the clay silation was resuspended in 20 mL DMF and 0.5 g Im had added to the suspension. The mixture was refluxed at 363 K for 28 h. The final product had filtered and then washed with DMF and ethanol. Then, the solid was dried at 373 K for 24 h.

Characterization of the adsorbent

The pore size distribution and specific surface area of the adsorbent were analyzed by the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) and Brunaure–Emmet–Teller (BET) methods, respectively. The chemical composition of the Mt and the acid-activated Mt was determined by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF). The surface functionality of the adsorbent was characterized using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, Bruker Tensor 27, Germany) in the range of 400–4000 cm−1. Particle surface morphology was investigated using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM; MiRA3 TESCAN, Czech Republic). The elemental analysis of the adsorbents was identified using energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS; MiRA3 TESCAN, Czech Republic).

Adsorption experiments

The batch adsorption experiments were carried out to determine the effects of the most important operational parameters on the removal of PCP from aqueous solutions by natural and modified Mt clays. These parameters were adsorbent dosage (10–150 mg), contact time (0–120 min), pH (2–9), adsorbate concentration (5–10 mg/L), agitation speed (100–450 rpm), and temperature (15–45 °C). All the experiments were conducted at room temperature (25 °C) except thermodynamic experiments. At first, a stock solution of PCP was prepared by dissolving pure sample of the solute into distilled water. After preparing 25 mL PCP solution of given concentration and setting pH, a specified amount of the sorbent was added to 50 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. Then, the prepared solutions were shaken on a shaker at a fixed agitating speed at room temperature. After shaking time, the suspensions were centrifuged (3000 rpm for 15 min) and the residual concentration of PCP was analyzed (UV visible; PG-instrument) at 254 nm wavelength.

In this study, the number of total samples based on the investigated parameters and replication was 159. The PCP adsorbed on the adsorbent (adsorption capacity) and the removal efficiency percentages were calculated using the following equations (Eqs.1 and 2):

| 1 |

| 2 |

Where C0 and Ce are the initial and equilibrium concentrations of PCP (mg/L), respectively. V (L) is solution volume, and M (g) is the mass of each adsorbent used.

Determination of pHpzc

pHpzc is one of the most important adsorbent characteristics because it indicates the state of electrical charge dispersion on the surface of adsorbent. In order to determine the pHpzc of the adsorbent, the solid addition method was performed [30]. To perform this method, 30 mL of 0.1 M NaCl solution had added into several 100 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. The initial solution pH (pHi) for each flask was adjusted between 2 to 12. HCl (0.1 M) and NaOH (0.1 M) solutions were used to adjust the solution pH. The optimal dosage of the sorbent was added to each flask and stirred for 24 h. Thereafter, the final pHs (pHf) of the solutions was determined. The pHpzc of the adsorbent was achieved by plotting pHf versus pHi.

Results and discussion

Characterization of the adsorbents

XRF

The XRF analysis was carried out to identify the chemical compositions of the clay and the subsequent chemical changes that occurred due to the acid treatment. Table 1 shows the results of the chemical analysis of the original and the acid treated Mt clay. The analysis showed that the parent Mt contains alumina and silica, which are in major quantities, whereas other oxides such as magnesium, calcium, potassium, and titanium oxides are in trace amounts.

Table 1.

Chemical analysis of the parent montmorillonite and acid-activated montmorillonite

| Sample | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | Na2O | MgO | K2O | TiO2 | MnO | P2O5 | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | ||

| Mt | 65.62 | 13.488 | 3.876 | 0.532 | 0.259 | 2.123 | 1.822 | 0.612 | 0.026 | 0.064 | 11.35 |

| A-Mt | 67.421 | 14.226 | 3.569 | 0.46 | 0.253 | 2.032 | 1.782 | 0.598 | 0.023 | 0.017 | 9.5 |

L.O.I. Loss of ignition

FTIR

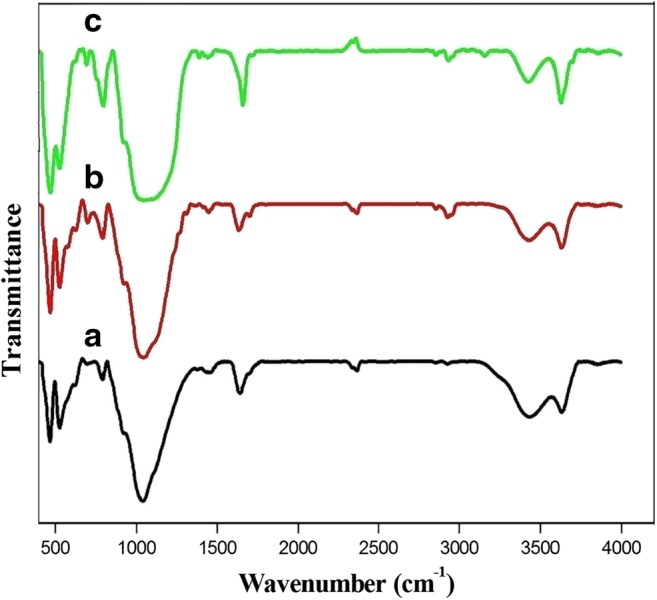

The infrared spectra of the materials before and after organo functionalization of Mt are presented in Fig. 1.The bands at 3628.26 and 3435.63 cm−1 are related to the OH stretching vibration of adsorbed water. In addition, the band at 1641.16 cm−1 is due to the OH bending vibration [35]. The FTIR spectra of acid montmorillonite (Amt) show that the absorption bands at 1039.86 and 467.87 cm−1 are related to Si-O-Si stretching vibrations, respectively [36]. The bands at 790.82 and 527.40 cm−1 identify the stretching and bending vibrations of Si-O-Al, respectively. For the silylated Mt, the bands at 2928.09 and near 2850 cm−1 can be referred to asymmetric and symmetric C-H stretching. The band at 1446.22 cm−1 is attributed to CH2 deformation [37]. The IR bond of 700.85 cm−1 is due to the C-Cl stretching. The adsorption of imidazole is observed at 3156.40 cm−1 attributed to the N-H stretching, 2930.06 cm−1 is due to the C-H asymmetric stretching of the ring, the band at near 2865 cm−1 is related to the C-H symmetric stretching of the ring. The band of 1388.24 cm−1 is related to the C-H bending.

Fig. 1.

FTIR spectra of: (a) Mt, (b) Mt-Cl, (c) Mt-Cl-Im

Bet

Specific surface area is an important factor for the determination of the adsorption capacity of adsorbents. The analyses of BET and BJH are used to determine the specific surface area and pore size distribution of the adsorbents, respectively. The specific surface area (SBET), total pore volume (VT), and mean pore diameter (Dp) are presented in Table S1. The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of the raw and organo-modified adsorbents are shown in Fig. S1. Based on IUPAC recommendations, the isotherms of the adsorbents can be classified as type IV, which is typical for mesoporous structures. The hysteresis loop of these samples is similar to type H3, which is typically found in agglomerates of plate-like particles containing slit-shaped [38].

FESEM

The FESEM of the used adsorbent, before and after adsorption of PCP are shown in Fig. 2. The organo-functionalized Mt has nanostructure with a plate-like morphology formed from the stacking of the silicate layers. According to Fig. 2 (a) and (c), it can be clearly observed that after adsorption of PCP, the sorption sites of the organo-functionalized Mt are covered and the holes of the adsorbent were occupied by PCP molecules.

Fig. 2.

FE-SEM images of the adsorbent before (a and b) and after (c and d) PCP adsorption

EDS

As seen 1in Fig. S2, the presence of appropriate elements in the EDS spectra of AMt-Cl and AMt-Cl-Im confirm the successful synthesis of each compound. The EDS analysis of AMt-Cl confirms the presence of carbon and chlorine elements. In this analysis, the weight percent of chlorine and carbon is 1.48 and 4.21%, respectively. The results of the EDS analysis of AMt-Cl-Im show that carbon and nitrogen are 8.29 and1.89%, respectively.

Effect of chemical modification

The effect of the functionalization of Mt on the removal percentage of pentachlorophenol is shown in Fig. S3. As can be observed from the fig. S3, the functionalization can increase the removal percentage. The corresponding values for AMt, AMt-Cl, and AMt-Cl-Im are 16.17, 59.11, and 92.64%, respectively. It can be due to the creation of stronger grafts and forces between the pentachlorophenol molecules and the adsorbent or the enhancement of active adsorption sites in the presence of the silane and imidazole groups.

Effect of adsorbent dosage on PCP adsorption

The effect of adsorbent dosage on the adsorption of PCP from aqueous solutions was investigated and the results are illustrated in Fig. 3. As shown, the removal percentage of PCP increases gradually as the amount of adsorbent is increased, and the adsorption capacity decreases with increasing adsorbent dosage from 0.01 to 0.05 g. The increase in the adsorbent dosage leads to an increase in the adsorbent surface area, which increases the number of adsorption sites available for adsorption of PCP molecules. The decrease in the adsorption capacity can be ascribed to two aspects. Firstly, at a fixed concentration and volume of PCP, the increase in the adsorbent dosage results in unsaturated adsorption sites on the surface of the adsorbent. Secondly, the agglomeration of particles due to higher dosage of the adsorbent may lead to a reduction in the adsorbent capacity due to an increase in diffusional path length [39].

Fig. 3.

Adsorption efficiency and adsorption capacity of the modified montmorillonite at different dosages

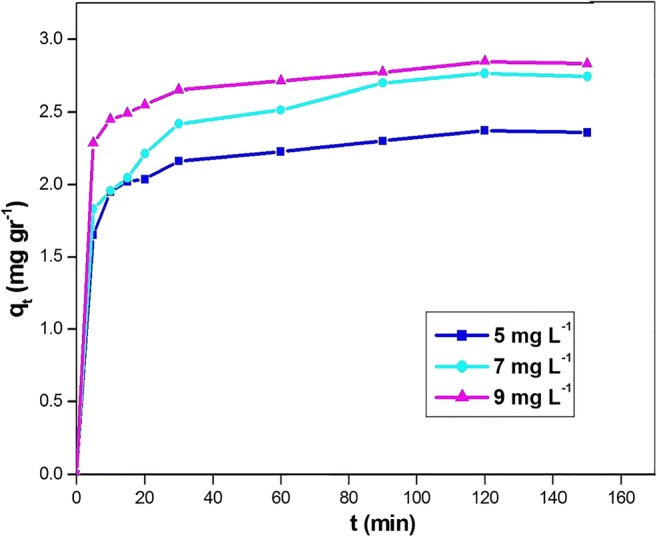

Effect of contact time and initial concentration on PCP adsorption

Figure 4 shows the effect of contact time and initial concentration on the pentachlorophenol adsorption capacity of the functionalized Mt. It can be seen, in all concentrations, the amount of adsorption in the initial minutes is high, then with the passage of time, it gradually decreases, and finally, equilibrium occurs after 2 h. The figure also shows that with the increase in initial concentration, the adsorption capacity increases, which is due to concentration gradient between the prepared solution and surrounding the adsorbent particles. At the first time, the expanded spaces of active sites are accessible and the concentration difference is high. Progressively these spaces are filled with PCP and the concentration gradient tends toward zero [40].

Fig. 4.

Effect of initial concentration on the adsorption capacity of PCP on modified montmorillonite

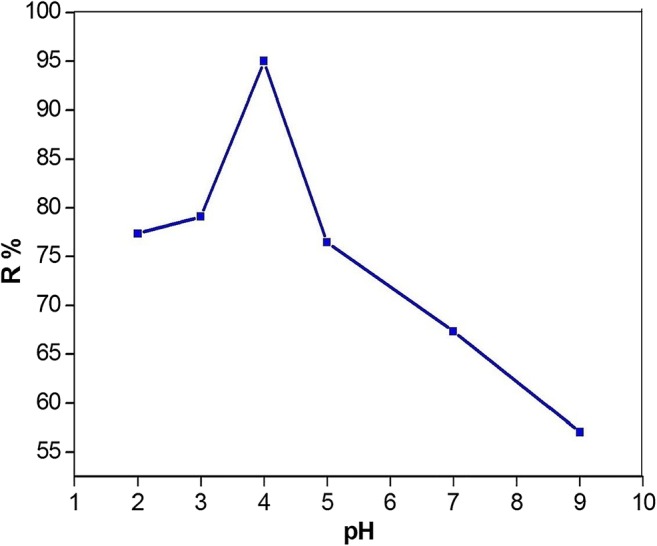

Effect of pH on PCP adsorption

The pH is an effective factor for the adsorption process because it greatly affects the adsorption process efficiency and adsorbent surface charge [41]. As shown in S4 pHpzc for modified Mt was obtained at pH = 6. Therefore, the adsorbent surface at pH values less and more than 6 shows that positive and negative charge, respectively. The effect of pH solution on the sorption of PCP using the modified Mt is illustrated in Fig. 5. The uptake behavior of PCP was studied at different pH from 2 to 9. The adsorbent surface charge depends on the pH of the solution and its pHpzc (zero point charge). At pH < pHpzc the surface charge adsorbent is positive and at pH > pHpzc the surface charge adsorbent is negative. The amount of adsorbed PCP seems to be related to the dissociation constant (pka), which is 4.7. So, the adsorbate is mainly in protonating form at pH < pka and in deprotonated form at pH > pka. Figure 5 shows, the maximum sorption was obtained at pH = 4. The reason can be expressed that the nitrogen imidazole the surface of the adsorbent could easily form a hydrogen bond with hydroxyl of PCP in a molecular state. When the pH of the solution increases (pH > pka), the adsorption of PCP decreased as a result of electrostatic repulsion between the negative charge of adsorbent surface and adsorbate [42].

Fig. 5.

Effect of the solution pH on the adsorption of PCP by modified montmorillonite

Effect of agitating speed on PCP adsorption

Agitation speed is a key parameter in adsorption phenomena because the adsorption rate is controlled by film and pore diffusion. In this work, the effect of agitation speed was investigated from 100 to 450 rpm. As shown in S 5, increasing the agitation rate from 100 to 380 rpm, the PCP removal efficiency increased. The result shows that with the increasing of agitation rate, the adsorption of PCP on the surface of adsorbent easily is performed. Also, the adsorbate diffusion into the interior surface of the modified Mt enhances because of the turbulence increasing [2]. Further increase of agitation rate to 450 rpm reduced the PCP removal, because the excessive turbulence resulted in insufficient interaction time between the adsorbent and adsorbate, hindering adsorption [43].

Adsorption isotherms

Adsorption isotherms are applied to explain the equilibrium between the amount of the adsorbate solution and the residual concentration of adsorbate in liquid phase at a constant temperature. The Langmuir [44], Freundlich and Temkin [45, 46] isotherms are used to describe the equilibrium adsorption. Langmuir model is valid for single-layer adsorption on the adsorbent surface with limited and homogeneous adsorption sites. Langmuir isotherm is defined by the following equation:

| 3 |

Where qm (mg g−1) is the maximum adsorption capacity, Ce (mg L−1) is the equilibrium concentration, qe (mg g−1) is the equilibrium adsorption capacity and KL (L mg−1) is the Langmuir equilibrium constant.

The liner form of the above equation is as follows:

| 4 |

Where, qm and KL are determined from the slope and intercept of the linear plot of versus Ce, respectively.

The Freundlich isotherm model is an empirical equation and valid for the adsorption process that occurs on heterogeneous surfaces. The Freundlich isotherm can be represented by Eq. (5):

| 5 |

The linear form of the Freundlich equation is as follows (Eq. (6)):

| 6 |

Where Kf (Lg−1) and n are represented to the adsorption capacity and intensity of the adsorbent, respectively. These parameters can be determined from the plot of Lnqe versus LnCe.

Another isotherm in the adsorption process is Temkin model. According to this model, the heat of adsorption of all molecules in the layer decreases linearly due to adsorbent and adsorbate interaction. The equation is shown as follows:

| 7 |

Where Ce is the concentration of PCP in equilibrium, R (8.314j mol-1K-1) is the universal gas constant, T(K) is the absolute temperature, BT (J mol−1) is the Temkin constant and AT (L g−1) is the equilibrium binding constant. The AT and BT are obtained by plotting qe versus LnCe.

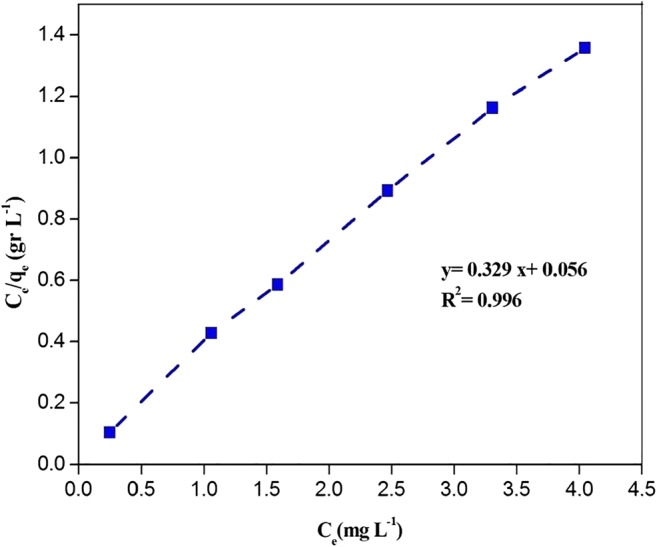

The experimental equilibrium data were fitted to the above adsorption isotherm models. The data of these isotherms are presented in Table 3. According to the correlation coefficients of the adsorption models (Table 2), the adsorption of PCP was excellently described by the Langmuir isotherm(as can be observed by Figure 6) with R2 value of 0.996, indicating a monolayer adsorption of PCP onto the adsorbent.

Table 3.

PFO and PSO constants and correlation coefficients for adsorption of PCP on modified montmorillonite

| C0(mgL−1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 2.375 | 0.766 | 0.805 | 0.029 | 0.999 | 2.392 | 0.16805 |

| 7 | 2.765 | 0.034 | 1.337 | 0.907 | 0.998 | 2.816 | 0.08918 |

| 9 | 2.846 | 0.702 | 0.758 | 0.029 | 0.999 | 2.865 | 0.19977 |

Table 2.

Isotherm constants for the adsorption of PCP onto the modified montmorillonite

| Isotherm models | Parameters | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| Langmuir |

qmax = 3.039 KL = 5.876 |

0.996 |

| Freundlich |

KF = 2.588

|

0.889 |

| Temkin |

AT = 250,196.027 BT = 11,854.41 |

0.876 |

Fig. 6.

Langmuir isotherm for adsorption of PCP on the modified montmorillonite

One of the essential factors of Langmuir isotherm is the separation factor, which is described by Weber and Chakravorti (1974) as following:

| 8 |

where C0 (mg L-1) is the initial concentration of the adsorbate (PCP). The separation factor shows the type of adsorption process, which can be irreversible (RL=0), favorable (0<RL<1), Liner (RL=1) and unfavorable (RL>1). The amount of RL for PCP was determined to be between 0 and 1 for various initial concentrations, demonstrating that the sorption of PCP is favorable.

Adsorption kinetics

The evaluation of adsorption kinetics are essential in order to obtain some valuable pieces of information on the factors effecting the reaction pathways, as well as on possible mechanisms controlling the adsorption process, such as surface absorption, chemical reaction and diffusion mechanisms. The kinetics of the adsorption process were analyzed by the pseudo-first order (PFO), pseudo-second-order (PSO) and Weber-Morris models to fit the experimental data.

The liner form of the (PFO) kinetic model can be presented by Eq. (9):

| 9 |

Where qe and qt are the amount of PCP adsorbed (mg g−1) at the equilibrium and time t (min), respectively. Moreover, K1 is the PFO rate constant (min−1). The PFO constant can be measured by plotting Ln(qe – qt) versus t. The amounts of K1 and qe were determined from the slope and intercept of the linear plots, and listed in Table 3.

The PSO model is based on chemisorption on the adsorbent. The liner form of the PSO kinetic model can be expressed as follows [47]:

| 10 |

Where qe is the amount of PCP adsorbed at equilibrium (mg g−1) and K2 is the PSO rate constant. The amount of K2 and qe were determined from the slope and intercept of the plot of versus t. All the parameters associated with this model are presented in Table 3.

In this study, intraparticle diffusion model was used to determine the diffusion mechanism of PCP into the internal porosity of the adsorbent. Weber and Morris suggested a model based on intraparticle diffusion theory which is expressed as:

| 11 |

Based on this equation, adsorption capacity is related to the square root of time. Where kid and C are the diffusion rate constant (mg g−1 min-0.5) and the intercept, respectively. The values of kid and C can be calculated from the slope and intercept of the plot qt versus t0.5. As can be observed in Fig. S7, the removal of pentachlorophenol on the modified Mt for all initial concentrations is faster at the initial minutes of contact time due to film diffusion (external surface adsorption). Then, with increasing of time, it is gradually becomes slow and finally reaches equilibrium. The decreasing of adsorption capacity occurs in two steps. At the first stage, which can be regarded as the external surface adsorption or the instantaneous adsorption, PCP molecules diffuse through the solution to the external surface of the adsorbent. The second stage is a delayed process in which intraparticle diffusion is rate limiting because the outer layers of the adsorbent are covered by PCP molecules. Therefore, the molecules are gradually diffused into the internal layers of the adsorbent, and finally the equilibrium stage starts to take place. It can be concluded that both surface adsorption and intra-particle diffusion were occurred simultaneously during the process and contributed to the adsorption mechanism [25]. Table S2 represents the intraparticle diffusion parameters for the adsorption of PCP at different initial concentrations.

Based on the obtained results (Table 3), the PSO had the highest correlation coefficient and followed a straight line. Moreover, the comparison of the theoretical and experimental PCP uptake (qe,cal, qe,exp) shows that the PSO rate is more accurate than PFO. Therefore, it can be concluded that in this experiment, the PSO is more favorable for PCP uptake. The constants of the PFO and PSO equations are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

The maximum removal efficiency (R%) of various adsorbents for PCP

Thermodynamic studies

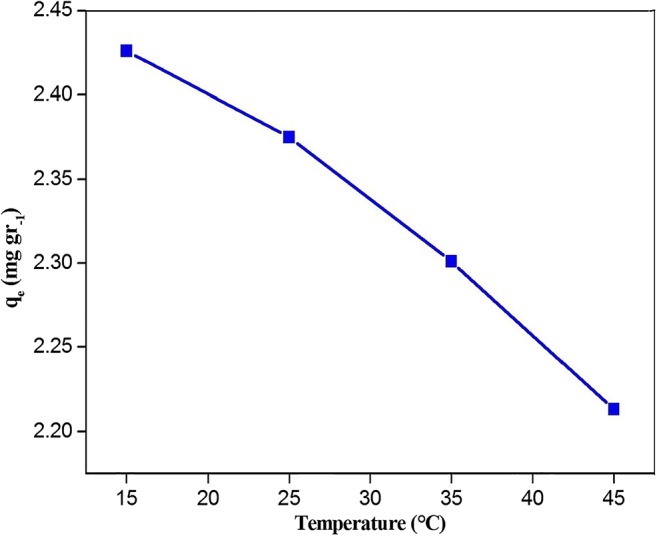

The effect of temperature on the removal efficiency was determined in the temperature range of 15–45 °C. Thermodynamic parameters such as Gibbs free energy change (∆G°), standard enthalpy (∆H°) and standard entropy (∆S°) were calculated by Eqs. (12) and (13):

| 12 |

| 13 |

Where R is the universal gas constant (8.314 j mol−1 K−1), T is the absolute temperature (K) and KL is the thermodynamic equilibrium constant, determined from .

∆S° and ∆H° amounts of the sorption process were respectively obtained from the slope and intercept of plotting Ln versus1/T in Eq.12, respectively. The results were summarized in Table 4. Based on the results, the negative values of ΔG° indicate that the sorption process was thermodynamically feasible and spontaneous. Generally, the ΔG° value is in the range of 0 to 20 kJ/mol and 80 to 400 kJ/mol for physical and chemical adsorptions, respectively [26]. Therefore, the values of ΔG° in this study indicated that the sorption of PCP is physiochemical. The negative and positive values of ΔH° in the adsorption study indicated the exothermic and endothermic natures, respectively [31]. So, the negative value of ΔH° in the present study is a representative of the exothermic process. Additionally, the negative entropy (ΔS°) represents the decrease of randomness at the solid/liquid interface during the adsorption of PCP on to the modified Mt. Furthermore, Fig. 7 shows the decrease in the value of PCP sorption by increasing the temperature.

Table 4.

Thermodynamic parameters for the adsorption of PCP onto the modified montmorillonite

| Temp(K) ΔS°(j/mol K) |

ΔG°(kj/mol) | ΔH°(kj/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 288 | −29.650 | −34.602 | −17.401 |

| 298 | −29.364 | ||

| 308 | −29.163 | ||

| 318 | −29.143 |

Fig. 7.

The effect of various temperatures on the adsorption of PCP (C0 = 5 mg L−1,contact time = 120 min, pH = 4 and the adsorbent dose = 50 mg)

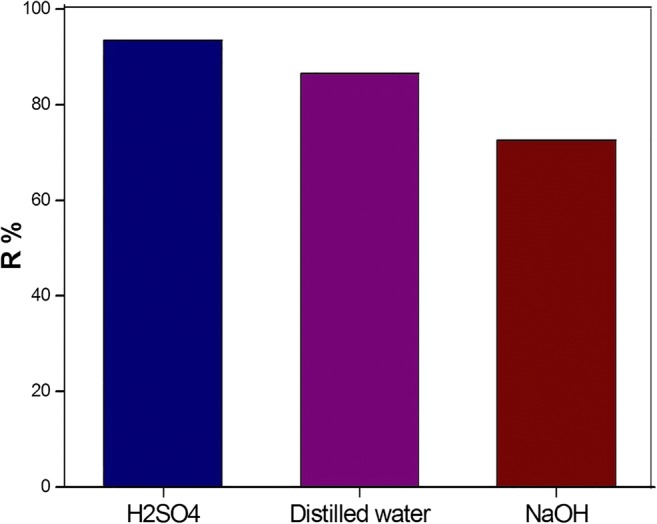

Reusability of the adsorbent

When adsorbent is saturated with an adsorbate, the adsorbent cannot adsorb a contaminant. Consequently, it can be activated to proceed the adsorption capacity. Recovery of adsorbent after the process, for economic and environmental reasons, is one of the most important properties of adsorbents. Regeneration studies were conducted on the PCP through distilled water, sulfuric acid (50 mL, 0.1 M) and sodium hydroxide (50 mL, 0.1 M) at the optimum pH and at room temperature. As depicted in Fig. 8, the regeneration of the adsorbent by sulfuric acid is more appropriate desorption agent compared to other compounds. The removal efficiency of PCP by the sulfuric acid and distilled water regenerated adsorbent to the initial adsorbent was in the range of 95–92.64 and 95–84.7 respectively.

Fig. 8.

Reusability of the modified montmorillonite for PCP (C0 = 5 mg L−1, pH = 4 and adsorbent dose = 50 mg)

Also, after third adsorption-desorption cycle, the removal percentage of PCP was reduced only about 2.36%. Therefore, the modified Mt can be used as an efficient adsorbent for PCP adsorption-desorption process from wastewater contaminated with PCP.

Comparison with other adsorbents

A Comparison of the removal efficiency of PCP on Amt-Cl-Im with other adsorbents in this paper is shown in Table 5. As can be seen that Amt-Cl-Im has a comparatively high removal efficiency to other adsorbents. This comparison shows that the Amt-Im-Cl adsorbent is a proper promising material for PCP removal from aqueous solution.

Conclusion

In this study, modified montmorillonite was prepared for removal of PCP from aqueous solutions. The characteristics of the adsorbent were investigated by various techniques, and the effects of several parameters on the adsorption of PCP onto the modified montmorillonite were studied. Through this study, the optimum value of adsorbent dosage was obtained to be 0.05 g, and the PCP adsorption onto the modified montmorillonite was found to be optimal in pH = 4. The adsorption kinetics was better described by the PSO kinetic model. The regression coefficients obtained for different isotherm models reveals that the Langmuir isotherm provided the best fit to the equilibrium data. The thermodynamic study showed that PCP adsorption onto the adsorbent was physical, exothermic and spontaneous. The regeneration of PCP saturated Mt using H2SO4 solution and then distilled water was the best method to desorb the PCP from the adsorbent. In addition, our results showed that the removal percentage of PCP is reduced by only about 2.36% after the third adsorption-desorption cycles.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 483 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the continuous support from the University of Mazandaran.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ali Akbar Amooey, Email: aliakbar_amooey@yahoo.com, Email: aamooey@umz.ac.ir.

Abdoliman Amouei, Email: iamouei1966@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Nayak PS, Singh BK. Removal of phenol from aqueous solutions by sorption on low cost clay. Desalination. 2007;207(1–3):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2006.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen TC, Sapitan JFJF, Ballesteros FC, Lu MC. Using activated clay for adsorption of sulfone compounds in diesel. J Clean Prod. 2016;124:378–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng P, Lang YH, Wang XM. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of pentachlorophenol on reed biochars: pH effect, pyrolysis temperature, hydrochloric acid treatment and isotherms. Ecol Eng. 2016;90:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.01.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nadavala SK, Swayampakula K, Boddu VM, Abburi K. Biosorption of phenol and o-chlorophenol from aqueous solutions on to chitosan–calcium alginate blended beads. J Hazard Mater. 2009;162(1):482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin Q, Liu K, Fu D, Gao H. Effect of chlorine content of chlorophenols on their adsorption by mesoporous SBA-15. J Environ Sci. 2012;24(8):1411–1417. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(11)60924-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devi P, Saroha AK. Simultaneous adsorption and dechlorination of pentachlorophenol from effluent by Ni–ZVI magnetic biochar composites synthesized from paper mill sludge. Chem Eng J. 2015;271:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2015.02.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niu J, Bao Y, Li Y, Chai Z. Electrochemical mineralization of pentachlorophenol (PCP) by Ti/SnO2–Sb electrodes. Chemosphere. 2013;92(11):1571–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Vincenzo JP, Sparks DL. Sorption of the neutral and charged forms of pentachlorophenol on soil: evidence for different mechanisms. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2001;40(4):445–450. doi: 10.1007/s002440010196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Leo P, Pizzigallo MDR, Ancona V, Di Benedetto F, Mesto E, Schingaro E, Ventruti G. Mechanochemical degradation of pentachlorophenol onto birnessite. JHazard Mater. 2016;244:303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Hu X, Liu X, Zhang Y, Zhao Q, Ning P, Tian S. Adsorption behavior of phenol by reversible surfactant-modified montmorillonite: mechanism, thermodynamics, and regeneration. Chem Eng J. 2018;334:1214–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.09.140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cea M, Seaman JC, Jara A, Mora ML, Diez MC. Kinetic and thermodynamic study of chlorophenol sorption in an allophanic soil. Chemosphere. 2010;78(2):86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dos Reis AR, Kyuma Y, Sakakibara Y. Biological Fenton’s oxidation of pentachlorophenol by aquatic plants. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2013;91(6):718–723. doi: 10.1007/s00128-013-1106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong PA, Zeng Y. Degradation of pentachlorophenol by ozonation and biodegradability of intermediates. Water Res. 2002;36(17):4243–4254. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du J, Bao J, Tong M, Yuan S. Dechlorination of pentachlorophenol by palladium/iron nanoparticles immobilized in a membrane synthesized by sequential and simultaneous reduction of trivalent iron and divalent palladium ions. Environ Eng Sci. 2013;30(7):350–356. doi: 10.1089/ees.2011.0318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirmardi M, Mahvi AH, Mesdaghinia A, Nasseri S, Nabizadeh R. Adsorption of acid red 18 dye from aqueous solution using single-wall carbon nanotubes: kinetic and equilibrium. Desalin Water Treat. 2013;51(34–36):6507–6516. doi: 10.1080/19443994.2013.793915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohseni SN, Amooey AA, Tashakkorian H, Amouei AI. Removal of dexamethasone from aqueous solutions using modified clinoptilolite zeolite (equilibrium and kinetic) Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2016;13:2261–2268. doi: 10.1007/s13762-016-1045-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang B, Liu Y, Li Z, Lei L, Zhou J, Zhang X. Preferential adsorption of pentachlorophenol from chlorophenols-containing wastewater using N-doped ordered mesoporous carbon. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2016;23(2):1482–1491. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-5384-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leite AB, Saucier C, Lima EC, Dos Reis GS, Umpierres CS, Mello BL, Shirmardi M, Dias S.L.P, Sampaio CH. Activated carbons from avocado seed: optimisation and application for removal of several emerging organic compounds. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2018; 25: 7647–7661. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Salam MA, Burk RC. Thermodynamics and kinetics studies of pentachlorophenol adsorption from aqueous solutions by multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2010;210(1–4):101–111. doi: 10.1007/s11270-009-0227-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jianlong W, Yi Q, Horan N, Stentiford E. Bioadsorption of pentachlorophenol (PCP) from aqueous solution by activated sludge biomass. Bioresour Technol. 2000;75(2):157–161. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00041-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viraraghavan T, Slough K. Sorption of pentachlorophenol on peat-bentonite mixtures. Chemosphere. 1999;39(9):1487–1496. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(99)00053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brás I, Lemos L, Alves A, Pereira MFR. Sorption of pentachlorophenol on pine bark. Chemosphere. 2005;60(8):1095–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathialagan T, Viraraghavan T. Biosorption of pentachlorophenol from aqueous solutions by a fungal biomass. Bioresources technology. 2009;100(2):549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan J, Zou X, Wang X, Guan W, Li C, Yan Y, Wu X. Adsorptive removal of 2, 4-didichlorophenol and 2, 6-didichlorophenol from aqueous solution by β-cyclodextrin/attapulgite composites: equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamics. Chem Eng J. 2011;166(1):40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2010.09.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo Z, Gao M, Yang S, Yang Q. Adsorption of phenols on reduced-charge montmorillonites modified by bispyridinium dibromides: mechanism, kinetics and thermodynamics studies. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2015;482:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2015.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carvalho WA, Vignado C, Fontana J. Ni (II) removal from aqueous effluents by silylated clays. J Hazard Mater. 2008;153(3):1240–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park Y, Ayoko GA, Frost RL. Characterisation of organoclays and adsorption of p-nitrophenol: environmental application. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;360(2):440–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nourmoradi H, Avazpour M, Ghasemian N, Heidari M, Moradnejadi K, Khodarahmi F, Moghadam FM. Surfactant modified montmorillonite as a low cost adsorbent for 4-chlorophenol: equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic study. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2016;59:244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jtice.2015.07.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sayılkan H, Erdemoğlu S, Şener Ş, Sayılkan F, Akarsu M, Erdemoğlu M. Surface modification of pyrophyllite with amino silane coupling agent for the removal of 4-nitrophenol from aqueous solutions. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;275(2):530–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L, Zhang B, Wu T, Sun D, Li Y. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of chlorophenols onto organoclays in aqueous solution. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2015;484:118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2015.07.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zaghouane-Boudiaf H, Boutahala M. Adsorption of 2, 4, 5-trichlorophenol by organo-montmorillonites from aqueous solutions: kinetics and equilibrium studies. Chem Eng J. 2011;170(1):120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2011.03.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linna S, Tao Q, He H, Zhu J, Yuan P. Loking effect: A novel insight in the silyation of montmorillonite surfaces. Materials Chemistry and physics. 2012;136:292–295. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2012.07.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marjanovic V, Lazarevic S, Jankovic-Castvan I, Potkonjac B, Janackovic D, Petrovic R. Chromium(VI) removal from aqueous solutions using mercaptosilane functionalized sepiolites. Chemical Engineeing Journal. 2011;166:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2010.10.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santos SS, Pereira MB, Almeida RK, Souza AG, Fonseca MG, Jaber M. Silylation of leached-vermiculites following reaction with imidazole and copper sorption behavior. J Hazard Mater. 2016;306:406–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin-Vien D, Colthup NB, Fateley WG, Grasselli JG. The handbook of infrared and Raman characteristic frequencies of organic molecules. Elsevier. 1991.

- 36.Senturk HB, Ozdes D, Gundogdu A, Duran C, Soylak M. Removal of phenol from aqueous solutions by adsorption onto organomodified Tirebolu bentonite: equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic study. J Hazard Mater. 2009;172(1):353–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eren E, Afsin B, Onal Y. Removal of lead ions by acid activated and manganese oxide-coated bentonite. JHazard Mater. 2009;161(2–3):677–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren L, Zhang J, Li Y, Zhang C. Preparation and evaluation of cattail fiber-based activated carbon for 2, 4dichlorophenol and 2, 4, 6-trichlorophenol removal. Chem Eng J. 2011;168(2):553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2011.01.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Panda AK, Mishra BG, Mishra DK, Singh RK. Effect of sulphuric acid treatment on the physico-chemical characteristics of kaolin clay. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2010;363(1–3):98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2010.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali AM, Akbar AA, Shahram G. Adsorption of direct yellow 12 from aqueous solutions by an iron oxide-gelatin nanoadsorbent; kinetic, isotherm and mechanism analysis. Journal Cleaner Production. 2017;170:570–580. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takdastan A, Mahvi AH, Lima EC, Shirmardi M, Babaei AA, Goudarzi G, Neisi A, Farsani MH, Vosoughi M. Preparation, characterization, and application of activated carbon from low-cost material for the adsorption of tetracycline antibiotic from aqueous solutions. Water Sci Technol. 2016;7:2349–2363. doi: 10.2166/wst.2016.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou L, Pan S, Chen X, Zhao Y, Zou B, Jin M. Kinetics and thermodynamics studies of pentachlorophenol adsorption on covalently functionalized Fe3O4@ SiO2–MWCNTs core–shell magnetic microspheres. Chem Eng J. 2014;257:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2014.07.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen GC, Shan XQ, Wang YS, Wen B, Pei ZG, Xie YN, Liu T, Pignatello JJ. Adsorption of 2, 4, 6 trichlorophenol by multi-walled carbon nanotubes as affected by cu (II) Water Res. 2009;43(9):2409–2418. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Langmuir I. The constitution and fundamental properties of solids and liquids. Part I.Solids. J. Am. Chem Soc. 1916;38:2221–2295. doi: 10.1021/ja02268a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamdaoui O, Naffrechoux E. Modeling of adsorption isotherms of phenol and chlorophenols onto granular activated carbon Part I . Two-parameter models and equations allowing determination of thermodynamic parameters. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007;147:381–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ho YS, Mckay G. A comparison of chemisorption kinetic models applied to pollutant removal on various sorbents. Process Safe. Environ. Prot. 1998;76:332–40. doi: 10.1205/095758298529696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peng S, Tang Z, Jiang W, Wu D, Hong S, Xing B. Mechanism and performance for adsorption of 2-chlorophenol onto zeolite with surfactant by one-step process from aqueous phase. Science of the Total Environment. 2017;581:550–58. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.12.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang, B., Xu, D., Wu, X., Li, Z., Lei, L., & Zhang, X. Efficient removal of pentachlorophenol from Wastewater by novel hydrophobically modified thermo-sensitive hydrogels. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry. 2015; 25: 67-72.

- 49. Kuśmierek K, Idźkiewicz P, Świątkowski A, Dąbek L. Adsorptive removal of pentachlorophenol from aqueous solutions using powdered eggshell. Archives of Environmental Protection.2017; 43(3):10-16.

- 50.Bosso L, Lacatena F, Cristinzio G, Cea M, Diez M C, Rubilar O. Biosorption of pentachlorophenol by Anthracophyllum discolor in the form of live fungal pellets. New biotechnology. 2015; 32(1): 21-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 483 kb)