Abstract

Production and usage of green and sustainable building materials realizes the desire to integrate more biodegradable, natural, recycled, and renewable resources into the construction industry. The aim is to replace traditionally available construction industry materials due to their environmental impacts through air emissions and waste generation. An observed trend is the production of insulation materials by recycling of industrial, agriculture, construction and demolition (C&D), and municipal solid wastes, thus reducing the environmental burdens of these wastes. While thermal insulation is important in saving energy, sound insulation has drawn much attention in recent years. There are various waste materials that have good thermal and sound properties, enabling effective replacement of traditional materials. This review investigates the use of industrial, agricultural, C&D, and municipal solid wastes to produce innovative thermal and acoustic insulating building materials. The performance of these insulating materials, and the influence of several materials parameters (density, thermal conductivity, sound absorption coefficient) on thermal and acoustic performance are reported after a brief description of each material.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40201-019-00380-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Solid wastes, Recycling, Thermal and sound insulation, Building materials

Introduction

Usage of environmentally friendly materials has significantly increased due to greater attention and awareness of society about the environment, and in particular the impact of the construction industry on it [1]. The application of thermal insulation is an important factor for energy savings in buildings [2]; effective building insulation can reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by over one hundred times versus the emissions incurred in manufacture of these materials. The European Commission’s target is to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 20% by 2020 versus a baseline fig. [3]. Production of insulation materials from recycled waste can be the solution to this problem [4, 5]. At the same time, noise pollution is one of the major concerns in building design because of its impact on human health [6]. With increasing demand for building materials, development of products that can provide better sound and thermal insulation has been become more popular [2].

Building materials that are produced from recycled wastes are now considered as green materials, as opposed to low quality or inexpensive materials according to traditional views. Thus, the production of thermal insulation materials by recycling of industrial, agriculture, construction and demolition (C&D), and municipal solid waste has drawn a lot of attention [7]. It is important to analyze and characterize the recycling of wastes as construction materials [8–10] for thermal or acoustic insulation. Researchers have investigated the potential use of agricultural by-products as thermal and sound insulation [9, 11–13]. Different wastes have been studied as raw material sources to obtain lightweight bricks [14], panels [15–17], or as concrete reinforcement [18, 19]. Table 1 summarize the waste materials that can be used to improve insulation properties.

Table 1.

Waste materials that can be used to improve insulation properties

| Waste type | Materials | References |

|---|---|---|

| Municipal waste | Recycled concrete with cores of textile waste | [15] |

| Recycled cardboard based panels | [16] | |

| Textile fiber waste | [20] | |

| End-of-life rubber waste particles have been made from the mechanical shredding of rubber | [21] | |

| Olive seeds after the separation and extraction of oil added to ground PVC and wood chips (from wood industry) | [22] | |

| Recycled-PET fiber based panels from end consumer of plastic bottle | [17] | |

| Recycled polyester fibers from recycled plastic | [23] | |

| Recycled foam from packaging materials | [24] | |

| Various plastics in municipal waste, such as recycled end-use carpet waste | [7, 24] | |

| Cellulose sound absorbers produced by using extracted cellulose from recycled paper | [25] | |

| Glass waste | [26] | |

| Agricultural waste | Maize husk after separation of the corn | [27] |

| Maize cob after separation of the corn | [27] | |

| Coconut pith with groundnut shell | [27] | |

| Sheep’s waste wool | [1] | |

| Sunflower stalks after the separation and extraction of oil | [28] | |

| Corn peel after separation of corn seed | [29] | |

| Wheat straw board composed of coconut coir and durian peel | [27] | |

| Kenaf binderless board | [27] | |

| Expanded vermiculite and perlite | [27] | |

| Stubble fiber after harvesting of wheat and barley | [30] | |

| Bagasse after extracting sugar | [31] | |

| End-of-Life Tires (ELTs) from cars | [32] | |

| Industrial waste | Recycled fillers including fly ash and bottom ash | [33, 34] |

| Composite from coal fly ash and scrap tire fiber | [13] | |

| Steel slag from the steel production plant | [35] | |

| Cardboard-based panels with recycled cardboard from packaging | [16, 36] | |

| Composite of onion skin and peanut shell fibers, perlite, fly ash, pumice, cement, barite | [37] | |

| Rice husk ash and volcanic ash | [38] | |

| High calcium fly ash concretes with recycled foam | [39] | |

| Elastomeric waste residues consumed in the packaging industry | [40] | |

| Composite of cotton waste, fly ash and barite | [41] | |

| Wood processing by-products waste | [42] | |

| C&D waste | Lightweight expanded clay, crushed bricks, and aggregates foam polystyrene and its waste | [43] |

| Recycled blocks containing C&D | [44] | |

| Construction waste wood used in cement-bonded particleboards | [45] | |

| Recycled concrete blocks and recycled aggregate concrete | [46] |

In buildings, all of the mentioned wastes (Table 1) can potentially replace synthetic thermal and sound insulation materials in the main and partition walls, ceiling, and roofs, leading to savings in virgin materials and cost reduction in the building industry. This review paper reports the current state of research on the conversion of municipal, agricultural, C&D, and industrial wastes into innovative thermal and acoustic insulating building materials. After a brief description of each material taken into account, and the required characteristics of insulation materials, the review reports and assesses how the materials’ properties (density, thermal conductivity, and sound absorption coefficient) influence thermal and sound insulation performance.

Characteristics of insulation materials

Thermal insulation

Thermal insulation materials are designed to reduce the transmission of heat flow through building walls. A building’s internal ambient temperature can be controlled with air conditioning. Application of thermal insulation in buildings is the main technique for reducing the use of air conditioning, therefore saving in energy consumption [9]. The thermal insulation performance of single or combined materials is usually evaluated by thermal conductivity and thermal transmittance. Thermal conductivity defines the heat flow passing through a unit area of the material, 1 m thick, with 1 K difference of temperature between the two sides of the material (Wm−1 K−1). Moreover, it is measured according to EN 12664 [47] and EN 12667 [48], or also ASTM C518 standard [49]. Thermal insulator materials are characterized by having a conductivity lower than 0.07 Wm−1 K−1 [4]. Insulator materials having thermal conductivity under 0.05 Wm−1 K−1 can be considered to be high performing [50]. Multi-layer thermal properties are usually characterized by thermal transmittance [51], which is the heat flow that passes through a unit area of a complex component or inhomogeneous material with a unit of Wm−2 K−1 [52].

There are comparable thermal properties between the corn’s cob, which is an agricultural by-product, and that of extruded polystyrene. Researchers have also carried out studies to produce new insulating material from jute, flax, and hemp. The application of a combination of these natural materials is comparable with conventional thermal and sound insulation materials [11]. Another study showed that bagasse fibers enhance the thermal properties of cement composites [53]. There are several other agricultural by-product materials, such as coconut coir and rice husk, that have shown lower thermal conductivity [54].

Acoustic properties

Sound insulation is expressed by measuring sound reduction index Rw, which can be done according to the ISO 717-1 standard [55]. Rw is the ability of a material to prevent the passage of sound through itself, and it is expressed in dB. The lower the sound reduction indicated, the lower the sound insulation of the structure. The amount of sound insulation by a wall in buildings is evaluated through the standard ISO 10140 [56]. The Rw is measured on real-sized samples, such as windows, partitions, doors, etc. [57].

Sound absorption coefficient (α) is the portion of the absorbed sound from the incident sound to the wall. The sound power absorbed by a material is usually evaluated by Eqs. (1) and (2).

| 1 |

| 2 |

where: Wi: the incident sound power; Wr: sound power reflected by the analyzed material; Wt: the sound power that passes through the material; and Wa: the absorbed sound power.

For small samples, the sound power absorbed by a material is measured by using an impedance tube in compliance with ISO 10534-2 in a laboratory setting [58], while for larger ones (at least 10 m2), this parameter is measured in a spatial reverberation room by ISO 354 (ISO 2003) or by ASTM C423-09a [59].

Open porosity and air movement are the key parameters to absorb sound [60]. Therefore, an interconnected structure is a vitally important parameter to reduce noise and absorb them [40]. As well as, the mass and density of the acoustic insulation materials have a strong relationship with this characteristic. Hence, the ability of sound insulation of heavier components is better than that of lightweight materials.

Wastes converted into building thermal and sound insulation materials

Municipal solid waste into building insulation materials

It is anticipated that by 2025 cities will produce about 2200 million tons per year of solid waste globally (Schiavoni et al. 2016). There are various materials in municipal waste that can be converted to insulation material.

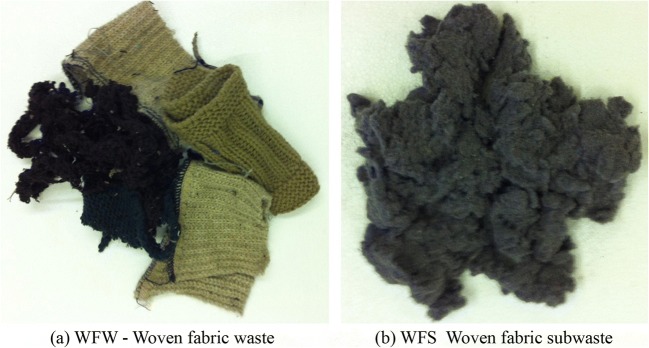

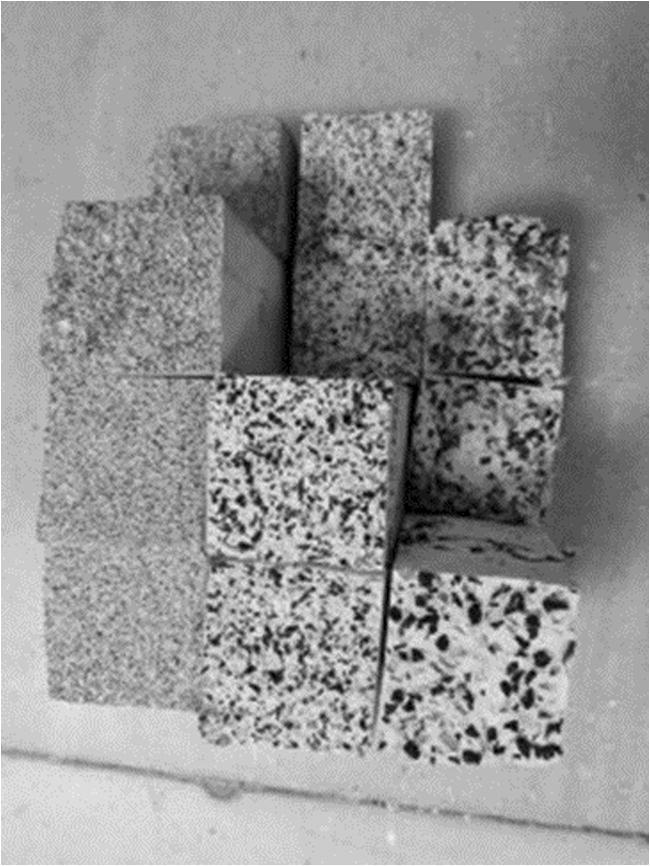

Textile fiber waste, which is composed of 28% C2S, 38% portlandite and 21% of calcite, has been added to natural lime. The textile waste fibers were 4–82 cm long and 0.05–0.4 mm thick. In the sample with lime to water ratio of 1:2, thermal conductivity was 0.25 Wm−1 K-1, and sound absorption coefficient (α) was 0.25 [20]. Thermal property of converted textile waste was 0.033–0.039 Wm−1 K−1 for tablecloth and linter; linter are short fibers clinging to cotton seeds after ginning [61]. The composite materials made up of polyurethane foam and textile fiber have better sound absorption properties compared to pure polyurethane foam [62]. The woven fabric waste and woven fabric sub-waste (Fig. 1) have thermal conductivity of 0.04–0.103 Wm−1 K−1 [63]. In one study that investigated the influence of proportion and particle size of rubber from ELTs, the insulation property was enhanced. The best results were for the finest particle size (0–0.6 mm and water/plaster = 0.77 and plaster/rubber = 0.6) (Fig. 2) [32].

Fig. 1.

Textile waste types studied by Briga-Sa et al. (2013) [63]. Reused with permission from Elsevier (4546730816186)

Fig. 2.

Sections of test pieces classified regarding their percentage of rubber weight and rubber size graduation [32]. Reused with permission from Elsevier (4546731141780)

The thermal conductivity of wood-gypsum-newspaper sandwiched concrete panel, and cement-wood were 0.233, 0.45, and 0.08 Wm−1 K−1, respectively [64–66]. The thermal conductivity of cement composites containing rubber with the density of 430 kg m−3 was 0.47 Wm−1 K−1 for a lightweight insulation panel containing 50% rubber particles [67].; as a result, the cement thermal conductivity was decreased about 60% [21]. The thermal conductivity of expanded shale-based concrete with a density of between 1100 and 1300 kg m−3 was 0.70 Wm−1 K−1 [67].. In cases where crumb rubber was used in concrete panels, these were lighter and had a higher sound absorption and lower heat transfer. Crumb rubber concrete (CRC) panels must have a thermal conductivity less than 0.303–0.476 Wm−1 K−1. Concrete that contains 30% and large-sized crumb rubber No. 6 (3.36 mm) have the lowest value of heat transfer rate. With 20% of No.6 crump rubber, sound absorption coefficient was 0.37. With increasing the rubber content and rubber particle size heat transfer decreases while the sound absorption increases [68], unlike rubber-gypsum composite [67].

Fluff is derived from the shredding of tires and contains ground tire rubber elastomer, metal fibers, and textile. The fibrous layer enhances the sound absorption coefficient (α). Resin causes a reduction in open porosity, which decreases the sound absorption properties. The best acoustic performance has been obtained for a sample with a thickness of 2.28 cm, density of 441 kg m−3, and compaction preset of 0.003 MP. In 2000 Hz, the sound absorption coefficient was 0.99 [69]. The thermal conductivity of composite of concrete containing plastic waste (20% PE) with the density of 606 kg m−3 was 0.663 Wm−1 K−1, and samples with 20% PVC waste with the density of 715 kg m−3 had a thermal conductivity of 0.769 Wm−1 K−1 [70]. Moreover, the thermal conductivity of another sample with 10% PE and 10% PVC, which had a density of 624 kg m−3, was 0.774 Wm−1 K−1.

In the study on various cardboards as sound insulation materials, which was made up of two honeycomb panels filled with cellulose fibers, and having a thickness of 15 mm and 10 mm cells, the sound absorption coefficient (α) was 0.85. On the other hand, in panels made of cylindrical cardboard with a density of 80 kg m−3 and 20 mm total thickness, α was 0.95. This amount is higher than conventional gypsum panel’s sound absorption coefficient (0.5–0.7), with cell diameters from 6 to 10 mm, and thickness of 60–200 mm, which are filled with wool or polyester fibers [71]. Recycled cellulose aerogels of recycled paper have thermal conductivity of 0.032 Wm−1 K−1, and can be an alternative to silica aerogel and sheep wool, which possess thermal conductivity of 0.026 and 0.03–0.04 Wm−1 K−1, respectively (Fig. 3) [72]. The thermal conductivity value can be decreased to 0.029 Wm−1 K−1 after being coated with methyltrimethoxysilane, for enhancement of hydrophobic properties [58]. Cellulose obtained from the paper is a sound absorbing material, and can be formed to obtain adequate noise reduction coefficient (NRC). The thermal conductivity of cellulose with a density of 55 kg m−3 is reportedly 0.039 Wm−1 K−1. NRC of such sound absorber with thickness of 60 mm and density of 36 kg m−3 has been measured to be 0.75 [25].

Fig. 3.

a Recycled cellulose fibers. b Recycled cellulose aerogel. c FE_SEM image of recycled cellulose aerogel Nguyen et al. (2014) [72]. Reused with permission from Elsevier (4546731300473)

In a survey on the performance of insulation panels made up of 38% ground PVC, 33% epoxy, 19% wood chips, and 10% olive seed, the thermal conductivity was lower than other samples with a higher amount of olive seed. Low thermal conductivity coefficients were obtained in those sample groups having more air gaps in the samples. Ultrasonic penetration speed was decreased in samples made up of 0.76 parts plaster and 0.24 parts water [22].

In the case of composites prepared with sand/cement ratio of 2, and 5% coarse sawdust, thermal conductivity was lower than in a sample with greater sand fraction and containing fly ash [42]. The effectiveness of silica-based wastes, rice husk ash, and volcanic ash powders, in thermal isolation, has also been assessed. Thermal conductivity decreases to 0.15 Wm−1 K−1 with an increase in the concentration of the blowing agent. Adding a rice husk ash or volcanic ash to the inorganic polymer composites increases the Si/Al ratio in the pore solution, which reduces the sodium silicate content to produce a suitable porous structure [38].

Using 50/50 proportions of waste wool fibers and RPET fibers, best sound insulation and thermal properties have been achieved. Sound absorption confiscation (α) in this mat is reported to be 0.70 in the frequency range of 50–5700 Hz, and thermal conductivity of this materials was 0.032 Wm−1 K−1 [23]. Recycled carpet pieces have shown adequate acoustic insulation performance, when converted into a granulated mix of industrial carpet waste. Optimum proportion of grain to fiber in this study was 60:40 [7].

Agricultural solid waste into building insulation materials

In the agricultural industry, harvesting and post-harvesting activities generate large quantities of solid waste [73]. Agricultural waste can offer a good alternative to conventional insulation materials: they are renewable annually and compostable, and they naturally have low thermal conductivity [74]. Total yearly agricultural by-product that has been produced in EU-27 in 2000–2002 was 457 million tonnes, about half of which (215 million tonnes) was accepted as by-product [75]. One study has shown only a small difference in thermal insulation values and material density between the samples tested. The performance of wool insulation was comparable to values reported in the literature for other materials such as polystyrene, fiberglass, and cellulose insulation (Fig. 4) [1].

Fig. 4.

Processing steps for manufacturing wool insulation batts Corscadden et al. (2014) [1]. Reused with permission from Elsevier (4546740124625)

The thermal conductivities of the paddy-straw board and coconut pith board, with urea formaldehyde resin as the binding material (6% w/w), were 0.0861 and 0.062, respectively [73]. In a study on an insulating composite made from sunflower stalks particles and chitosan with composition ratio of 4.3% (w/w), thermal conductivity was 0.056 Wm−1 K−1, and α was 0.2 at frequency range of 2500–4000 Hz, which is lower than 0.5 for insulating materials.

A composite material made up of sugarcane waste fibers and polyester has been reported to have a coefficient of absorption greater or equal to 0.5 [76]. Therefore, the acoustic performance of this bio-based composite was considered too low [28]. The thermal conductivity coefficient of an insulation building material made up of sunflower stalk fibers, the spongy parts of sunflower stalks, textile waste, cotton waste, stubble fibers, and epoxy, was 0.1642 Wm−1 K−1. Such value is greater than 0.1; as a result, this material could not be considered as an insulation material according to TS 805 EN 60155 (Fig. 5) [30]. The thermal conductivity values of narrow-leaved cattail fibers, combined with a binder having a density of 200–400 kg m−3, were 0.0438–0.0606 Wm−1 K−1; this is less than comparable fibrous and cellular materials [27].

Fig. 5.

Insulation boards made from sunflower stalk, textile waste and stubble fibers Binici et al. (2013) [30]. Reused with permission from Elsevier (4546740391584)

In one study, hemp fibers were bound through the use of polyester bio component fibers. For hydrophobic treatment of these samples, H6: Hexadecyl trimethoxysilan (HDTMS), T6: Tris (2-methoxy ethoxy) (vinyl) silane (TMEVS), and LUK: Lukofob 39–hydrophobic agent were used for hydrophobization of silicate materials. DR: Draxil 153–hydrophobic agent was used for wood-based materials, and TG: Tagal–impregnation agent was used for textiles. In this study, the samples show satisfactory thermal property (lower than 0.07 Wm−1 K−1) under wetting conditions after hydrophobic treatments with any of the materials mentioned above [6].

Particleboards made from a mixture of Tissue Paper Manufacturing (TPM) waste and corn peel were investigated as thermal and sound insulation layers. Results show that with increasing amount of corn peel the density of the particleboards decreases, which leads to a decrease in thermal conductivity. In the cases where TPM to corn peel ratio was 25 to 75, thermal conductivity was 0.13 Wm−1 K−1; therefore, these materials could be considered as thermal building insulation [29].

Industrial solid waste into building insulation materials

Today’s varied industries produce a significant amount of wastes; as a result, there is urgent need to develop suitable routes to treating or disposing them. Vast amounts of fly ash and bottom ash are generated by burning coal in power plants [77]. The insulation materials that have been made from fly and bottom ash could be not only considered as one option for the sanitary point of view, but also have attractive economic benefits [78].

In a study on coal bottom ash as sound insulation, the designed methodology consisted of determining the intrinsic acoustic properties (tortuosity, open porosity, and static airflow resistivity) of bottom ash-based concretes with different particle sizes. The acoustic absorption coefficient measurements were obtained in an impedance tube and through mathematical equations in the software CARAM. This model describes the acoustic behavior of porous materials. Ash to cement ratio was fixed at 4:1. Moreover, the bottom ash was sieved using 2.5 mm mesh size, generating two fractions. The first one was coarse, E2.1 (7 mm > Dp > 2.5 mm), and the other was fine, E2.2 (Dp < 2.5 mm). The sound absorption was higher in the coarse sample. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the samples tested and their acoustic properties [79].

Table 2.

Characteristics of the samples tested for the determination of the intrinsic properties of the materials and maximum sound absorption coefficient (α) and the frequency, density and thickness of the specimens tested Arenas et al. (2017) [79]

| Material | Particle size (mm) | Specimen code | Thickness | Density (kg m−3) | frequency | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom Ash | 7 > Dp > 2.5 | E2.1.1.1 | 40.30 | 765 | 1241 | 0.93 |

| E2.1.1.2 | 40.25 | 773 | 1278 | 0.93 | ||

| E2.1.1.3 | 80.55 | 780 | 1241 | 0.94 | ||

| E2.1.2.1 | 80.95 | 783 | 603 | 0.94 | ||

| E2.1.2.2 | 80.95 | 781 | 606 | 0.93 | ||

| E2.1.2.3 | 81.10 | 803 | 563 | 0.91 | ||

| E2.1.3.1 | 121.55 | 771 | 356 | 0.94 | ||

| E2.1.3.2 | 121.50 | 796 | 356 | 0.92 | ||

| E2.1.3.3 | 120.30 | 799 | 356 | 0.91 | ||

| Bottom Ash | Dp < 2.5 | E2.2.1.1 | 41.65 | 1242 | 106 | 0.50 |

| E2.2.1.2 | 41.30 | 1259 | 128 | 0.53 | ||

| E2.2.1.3 | 41.10 | 1236 | 106 | 0.45 | ||

| E2.2.2.1 | 82.20 | 1245 | 118 | 0.34 | ||

| E2.2.2.2 | 82.05 | 1263 | 97 | 0.34 | ||

| E2.2.2.3 | 81.90 | 1244 | 118 | 0.36 | ||

| E2.2.3.1 | 123.25 | 1250 | 128 | 0.27 | ||

| E2.2.3.2 | 122.70 | 1255 | 128 | 0.31 | ||

| E.2.2.3.3 | 122.35 | 1255 | 128 | 0.39 |

In a survey on cardboard-based insulation panels, two types of flutes (C and E) with thicknesses of 4.1 and 1.9 mm, respectively, were investigated. Samples with C-flutes showed a thermal conductivity of 0.053 Wm−1 K−1 while the thermal conductivity of E-flute was 0.058 Wm−1 K−1. Thermal conductivity for the E and C-flute are similar to each other despite the significant difference in the percentage of cardboard mass. The E-flute panels with higher density had better sound insulation behavior than the C-flute panels (Fig. 6). Such recycled cardboard panels cannot be considered as the sound insulation material due to the low acoustic absorption [36]. Porous sound absorbers require high open porosity, interconnected pores, and air movement inside [16].

Fig. 6.

Cardboard samples tested: (a) E-flute; (b) C-flute; (c, d, e, f) Concordant, orthogonal 1 × 1 and 2 × 2, and sandwich (4E-10C-4E) samples Asdrubali et al. (2016) [16]. Reused with permission from Elsevier (4546770023990)

In another study, gypsum, vermiculite, fly ash, and polypropylene fibers used to produce insulation board. In the thickness range of 2 and 4 mm, the sound absorption coefficients were 0.3 and 0.8 in the frequency of 1000 to 2000 Hz, respectively, and thus could be considered as sound absorbing the material. On the other hand, these board present low thermal conductivity (0.3 Wm−1 K−1) [34]. Coal fly ash and scrap tire fiber (FA-STF) have also been considered as wall insulation in buildings. The mass ratios for the final mixture design consisted of 66% of fly ash, 8% of tire fiber, and 26% of water. The measure value of thermal conductivity for this insulation material was 0.035 Wm−1 K−1 [13].

Recycle foam (RF) is a type of discarded packaging from household electrical appliances. Thermal conductivities of crushed foam used an aggregate in concrete at added ratio of 0.95, 1.00, and 1.05% were 0.30, 0.29, and 0.27 Wm−1 K−1, respectively [39]. The thermal conductivity values of another lightweight aggregate foamed geopolymer concrete was reported to be 0.47–0.58 Wm−1 K−1 [80]. In a survey on chipboards, which is produced with cotton waste, fly ash, and barite, natural white epoxy resin is used as a binder, and a thermal conductivity of 0.0022 KWm−1 K−1 is achieved. Thermal conductivities of all samples prepared were lower than 0.060, and these samples resisted against sound transmission [41].

In the insulation material production from onion skin and peanut shell fibers, fly ash, pumice, perlite, barite, cement, and gypsum, the results which were presented in Table 3 were notable. The thermal conductivity of pumice (PU) and perlite-added samples and the ultrasonic sound penetration velocity were lower than the others. The thermal conductivity of samples made with onion skins and peanut shells were 3.5–5 times smaller than those of the control, which resulted from the fiber ratios [37].

Table 3.

Physical, thermal and sound properties of onion skin and peanut shell fibers, fly ash, pumice, perlite, barite, cement and gypsum samples [37]

| Sampel | FA50PE50C | BA100C | PE100C | PU100C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition |

FA (50 g) W (25 g) C (50 g) OSPS (150 g) |

BA (100 g) C (50 g) W (25 g) OSPS (150 g) |

PE (100 g) C (50 g) W (25 g) OSPS (150 g) |

PU (100) C (50) W (25) OSPS (150) |

| Density (kg m−3) (CB) | 1150 (L) | 3450 (H) | 1330 | 1590 |

| Sound penetration (kl s−1) (CB) | 0.69 | 1.25 (H) | 0.16 (L) | 0.16 (L) |

| Termal coductivity (Wm−1 K−1) (CB) | 0.081 | 0.313 (H) | 0.062 (L) | 0.078 |

| Sample | PE100G | BA100G | FA15PU15G | |

| Composition |

PE (100) G (100) W (25) |

FA (15) PU (15) G (50) W (25) |

||

| Density (kg m−3) (GB) | 1040 (L) | 3330 (H) | 1500 | |

| Sound penetration (kl s−1) (GB) | 0.1 (L) | 0.7 | 0.81 (H) | |

| Termal coductivity (Wm−1 K−1) (GB) | 0.058 (L) | 0.223 (H) | 0.103 |

FA Fly ash, PE Perlite, C Cement, OSPS Onion skins and peanut shells, W Water, BA Barite, PU Pumice, G Gypsum, CB Cement base, GB Gypsum base

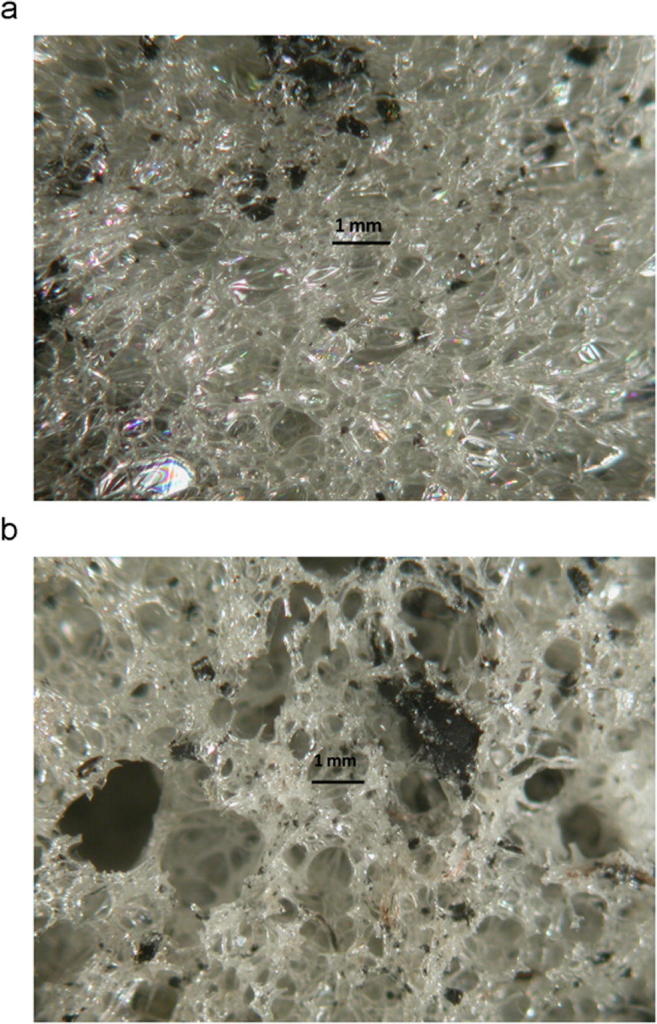

In panels made from waste residue particles and foaming binder, a mix of PVC grains and nylon fibers from PVC-backed carpet and tire shredded residue was used (Fig. 7) [40]. PU foam adhesive was used as a binder. Shredded residue samples showed good sound absorption coefficient with the low open porosity (67%) and binder loading of 10%, and had thermal conductivity of 0.06 Wm−1 K−1 and high density (495 kg m−3). Moreover, the sound absorption was 4 DLa and sound impact insulation was 135 dB. There is a direct relationship between open porosity and sound absorption. On the other hand, there is an adverse relationship between the polyol and open porosity. For example, with increasing amount of polyol, with molecular weight 2000 Da, in the binder and an increase in density (334 kg m−3), open porosity was decreased to 75% and the thermal conductivity was 0.043 Wm−1 K−1. Moreover, the sound insulation and sound absorb were 128 dB and 2 DLa, respectively. In the samples with carped shredded (40:60 fiber: grain) at a binder loading of 10%, the density, open porosity, thermal conductivity, sound insulation, and sound absorb were 366 kg m−3, 75%, 0.06 Wm−1 K−1, 134 dB, and 2DLa, respectively. The sound absorption was improved due to the increase of binder, causing a decrease of the density and an increase of the open porosity. By increasing the ratio of fiber-to-grain, the open porosity and sound absorption were decreased, while the thermal conductivity was increased. Moreover, increasing the fiber size led to an increase in tortuosity; therefore, the open porosity, thermal conductivity, and sound absorption were increased. Sound absorption was increased due to the general increase in open porosity. On the other hand, with decreasing the open porosity, the thermal conductivity was decreased [40].

Fig. 7.

a Closed cell structure observed with tire shred residue compounded with the low molecular weight PU2 binder. b Open cell structure observed with tire shred residue compounded with the high molecular weight PU2 binder [40]. Reused with permission from Elsevier (4546770206236)

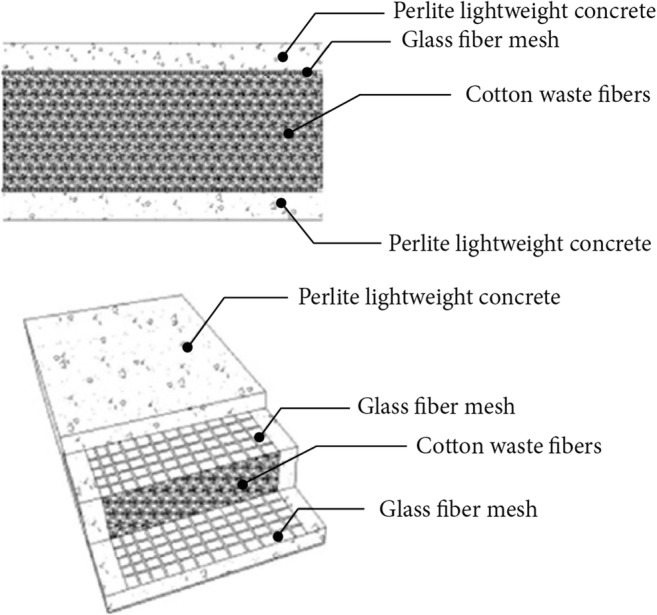

Cotton fibers are classified as natural fibers and they represent a vast amount of waste in the textile industry, but also possess low thermal conductivity, low density, and low cost. Glass fiber mesh was used in order to keep the waste fibers in a central layer within lightweight concrete. In this investigation, all the specimens were constructed using perlite concrete, and had thermal conductivity in the range of 0.1–0.3 Wm−1 K−1, which is lower than 0.3 Wm−1 K−1 in previous studies (Fig. 8) [15].

Fig. 8.

2D and 3D display of the waste-fiber/glass-fiber/perlite-concrete specimens and their components [15]. Reused under CC BY 3.0 license

C&D waste into building insulation materials

C&D management is one of the major sustainability issues worldwide [81]. Some of the environmental impacts are the contamination of water resources and soil, which result in environmental and economic impacts due to unsanitary waste disposal [82]. Yet, the recycling rate of C&D reaches as high as 75% in some European countries [83]. Two types of recycled aggregates have been obtained from construction waste, which have been classified according to their size: fine recycled aggregate (FRA) (0–10 mm) and coarse recycled aggregate (CRA) (10–80 mm). Table 4 is a water/solid ratio and physical, sound and thermal properties of samples. Blocks with fine and coarse recycled aggregates (HR) have a low thermal conductivity (0.66 Wm−1 K−1), which is not lower than a medium-weight concrete. The recycled aggregates increase α to 0.5 at 5000 Hz [44].

Table 4.

Water/solid ratio, physical, sound, and thermal properties of samples [44]

| Mixture | Water/solids ratio | density | PC*a | FRA | FA*b | CRA | CA*c | Conductivity (Wm−1 K−1) |

Sound absorption (α) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H0*d | 0.09 | 2088 | 20 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 30 | – | 0.1 (H0) in 1500 Hz and 0.25 (H0) in 5000 Hz |

| H-FRA20 | 0.12 | 1790 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 0 | 30 | – | – |

| H-FRA40 | 0.18 | 1750 | 20 | 40 | 10 | 0 | 30 | – | – |

| H-FRA50 | 0.20 | 1710 | 20 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 30 | – | – |

| H-CRA20 | 0.14 | 1820 | 20 | 0 | 50 | 20 | 30 | – | – |

| H-CRA30 | 0.16 | 1500 | 20 | 0 | 50 | 30 | 30 | – | – |

| HR*e | 0.18 | 1590 | 20 | 50 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0.66 (30–70 °C) | 0.15 (H1) in 1500 Hz and 0.5 (H1) in 5000 Hz |

*a= Portland cement (PC); *b = fine aggregate (FA); *c = coarse aggregate (CA); blocks without recycled waste (H0)*d, and with fine and coarse recycled aggregates (HR)*e

A huge amount of waste wood formwork from construction sites is disposed of in landfills every day [84]. Construction waste wood has been investigated for conversion into thermal and noise insulating particleboard. These wastes were granulated and sieved to 2.36–5 mm and 0.3–2.36 mm as coarse aggregates and fine aggregates, respectively. Thermal conductivity was 0.29 Wm−1 K−1, which represented 19% of the thermal conductivity in a concrete board (1.52 Wm−1 K−1) [45]. This amount was comparable with that of solid wood panel (0.24 Wm−1 K−1 at 1.0 g cm−3) [85], but higher than that of waste wood (0.07 Wm−1 K−1) (Fig. 9) [45].

Fig. 9.

Recycling of construction waste wood into noise and thermal insulation cement-bonded particleboards. Adapted from Wang et al. (2016) [45]

In one study, recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) with particle size of 0–10 mm was used to determine thermal conductivity of RAC, and these RCA were used to make recycled concrete block. Recycled coarse aggregates, with particle size over 10 mm, was used to determine the thermal conductivity of large particle recycled concrete (LRC). Crushed waste brick slag was screened to <10 mm, and used to test the thermal conductivity of recycled brick concrete (RbC). Table 5 presents the composition, physical, and thermal characteristic of samples in this study. The amount of recycled aggregate has a high effect on the density and thermal conductivity. Greater density led to greater thermal conductivity. The thermal conductivity of LRC was reduced with increasing amount of the recycled aggregate. The thermal conductivity of RBC was less than that of RCA [46].

Table 5.

Composition, physical and thermal characteristic of samples [46]

| Groups | Water | Cement | Recycled coarse aggregate 5–10 mm | Natural coarse aggregate 5–10 mm | Recycled fine aggregate 0–5 mm | Natural fine aggregate 0–5 mm | Natural aggregate >10 mm | Recycled concrete aggregate >10 mm | Thermal conductivity (Wm−1 K−1) | Density (kg m−3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAC-1 | 130 | 325 | 395 | 592 | 263 | 395 | – | – | 1.0568 | 1955 |

| RAC-2 | 130 | 289 | 706 | 303 | 471 | 202 | – | – | 0.8336 | 1794 |

| RAC-3 | 130 | 260 | 1036 | – | 684 | – | – | – | 0.7392 | 1619 |

| RAC-4 | 140 | 350 | 676 | 290 | 644 | – | – | – | 0.8262 | 1768 |

| RAC-5 | 140 | 311 | 989 | – | 264 | 396 | – | – | 0.8464 | 1868 |

| RAC-6 | 140 | 280 | 403 | 605 | 470 | 202 | – | – | 0.9358 | 1903 |

| RAC-7 | 150 | 375 | 945 | – | 441 | 189 | – | – | 0.7350 | 1788 |

| RAC-8 | 150 | 333 | 388 | 582 | 647 | – | – | – | 0.9300 | 1832 |

| RAC-9 | 150 | 300 | 693 | 297 | – | 396 | – | – | 0.9348 | 1871 |

| RbC-1 | 130 | 325 | – | – | 658 | – | 987 | – | 1.0114 | 1981 |

| RbC-2 | 130 | 325 | – | – | 658 | – | 494 | 494 | 0.7678 | 1760 |

| RbC-3 | 130 | 325 | – | – | 658 | – | – | 987 | 0.8148 | 1617 |

| LRC-1 | 130 | 325 | 592 | 395 | 395 | 263 | – | – | 1.3990 | 2195 |

| LRC-2 | 130 | 325 | 296 | 691 | 197 | 461 | – | – | 1.0848 | 2094 |

| LRC-3 | 130 | 325 | – | 987 | – | 658 | – | – | 1.0114 | 1981 |

Comparative analysis of the thermal and sound performance of unconventional insulation materials

Tables 6, 7, 8, and 9 are thermal and sound properties of insulation materials made up municipal solid, agricultural, industrial, and C&D waste, respectively.

Table 6.

Thermal and sound properties of insulation materials made from municipal solid waste

| Type | Density (kg m−3) | Conductivity (Wm−1 K−1) | Sound Absorption (α) | sound absorption frequencies (Hz) | Composite | Particle board | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSW | Textile fiber waste blundered with natural hydraulic lime | 716 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 500–4500 | – | 1 | [20] |

| Cement composites containing rubber | 1150 | 0.47 | NA | – | 1 | – | [21] | |

| Recycled cellulose aerogels | 40 | 0.032 | NA | – | – | 1 | [71] | |

| Gypsum with olive seed and wood chips | . | 0.074 | 0.023 kl s−1 | 50–60 | 1 | – | [22] | |

| Plaster–rubber mortars | 653 | 0.14 | 85 dB | 1000 | 1 | – | [32] | |

| Woven fabric waste | 440 | 0.04 | NA | – | – | 1 | [63] | |

| Rice husk ash and volcanic ash powders | NA | 0.16 | NA | – | – | 1 | [38] | |

| 50% Wool and 50% recycled polyester | 62.50 | 0.032 | 0.71 | 50–5700 | – | Mat | [23] | |

| Recycled PET | 66.66 | 0.033 | 0.69 | 50–5700 | – | Mat | [23] | |

| Recycled wool | 62.5 | 0.032 | 0.61 | 50–5700 | – | Mat | [23] | |

| 10% PE + 10 PVC + mortar | 624 | 0.774 | NA | – | 1 | – | [70] | |

| Recycled carpet (grain/ fiber = 60:40) | 277 | NA | 55 dB | 1000 | – | Mat | [7] | |

| Recycled cardboard 50 mm thinks | 50 | NA | 0.85 | 100–600 | – | Panel | [16] | |

| Cardboard tube (slit = 4 mm, distance = 20 mm) | 80 | NA | 0.95 | 100–600 | – | Panel | [16] | |

| Crumb rubber (30%) concrete panel | 2030 | 0.29 | NA | – | 1 | – | [68] | |

| Crumb rubber (20%) concrete panel | 2110 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 1000 | 1 | – | [68] | |

| 50% recycled polyurethane +50% textile | 65 | NA | 0.6 | 250–2000 | – | 1 | [62] | |

| Cellulose from recycled paper | 55 | 0.039 | NA | – | – | 1 | [25] | |

| Cellulose from recycled paper | 36 | NA | 0.75 | >500 | – | 1 | [25] | |

| Rubber particles and fluff | 441 | NA | 0.9 | 2000 | – | 1 | [69] |

N.A. not available

Table 7.

Thermal and sound properties of insulation materials made from agricultural solid waste

| Materials | Density (kg m−3) | Conductivity (Wm−1 K−1) | Sound absorption (α) | sound absorption frequencies (Hz) | composite | Particleboard | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maize husk | 310 | 0.095 | NA | – | – | 1 | [73] |

| Maize cob | 320 | 0.096 | NA | – | – | 1 | [73] |

| Paddy straw | 190 | 0.062 | NA | – | – | 1 | [73] |

| Coconut pith | 290 | 0.0861 | NA | – | – | 1 | [73] |

| Groundnut shell | 540 | 0.15 | NA | – | – | 1 | [73] |

| Cereal straw | 100 | 0.055 | NA | – | – | Bales | [75, 86] |

| Hemp | 44 | 0.045 | 0.6 (30 cm) | > 150 | – | 1 | [75, 86] |

| Jute fiber | 35 | 0.05 | NA | – | – | 1 | |

| Wood fiber | 150 | 0.045 | NA | – | – | 1 | [75] |

| Cork | 130 | 0.05 | NA | – | – | 1 | [87] |

| Cork | 130 | 0.049 | NA | – | – | 1 | [87] |

| Cork | 151 | 0.039 | 0.39 | – | *a | [75] | |

| Coconut | 95 | 0.045 | NA | – | – | 1 | [75] |

| Flax | 50 | 0.041 | NA | – | – | 1 | [75] |

| Cellulose | 70 | 0.037 | 1 (65 cm) | 5000 | – | Loose fill *a | [86] |

| Cellulose | 30 | 0.04 | NA | – | – | Loose fill *a | [88] |

| Cellulose | 138 | 0.047 | NA | – | – | Loose fill *a | [75] |

| Sheep wool (Romanov) | 22.1 | 0.0072 | NA | – | – | Mat | [1] |

| Sheep wool (Suffolk) | 22.7 | 0.0068 | NA | – | – | Mat | [1] |

| Sheep wool (North Country Cheviot) | 23 | 0.0066 | NA | – | – | Mat | [1] |

| Sheep wool (commercial 1)*b | 21.9 | 0.006 | NA | – | – | Mat | [1] |

| Sheep wool (commercial 2) | 22 | 0.0065 | NA | – | – | Mat | [1] |

| Sheep wool | 58.82 | 0.0315 | 0.75 (1.7 cm) | 50–5700 | – | Mat | [25] |

| Sunflower stalks particles and chitosan | 175 | 0.057 | 0.2 | 1 | – | [28] | |

| TPM/corn (100:0) | 980 | 0.25 | NA | – | – | 1 | [29] |

| TPM/corn (75:25) | 969 | 0.19 | NA | – | – | 1 | [29] |

| TPM/corn (50:50) | 789 | 0.14 | NA | – | – | 1 | [29] |

| TPM/corn (25:75) | 726 | 0.13 | NA | – | – | 1 | [29] |

| FEF (hemp 100% without treatment | 38 | 0.062 | NA | – | – | 1 | [6] |

| H6 with HDTMS (85%), C = 6% | 39 | 0.058 | NA | – | – | 1 | [6] |

| T6 with TMEVS (98%), | 38 | 0.061 | NA | – | – | 1 | [6] |

| LUK with Lukofob 39, | 40 | 0.064 | NA | – | – | 1 | [6] |

| DR with Draxil 153 | 29 | 0.062 | NA | – | – | 1 | [6] |

| TG with Tagal 100 | 29 | 0.067 | NA | – | – | 1 | [6] |

| Cattail fiber | 300 | 0.052 | NA | – | – | 1 | [27] |

| SSFCTSE*c | 143 | 0.1642 | NA | – | – | 1 | [89] |

| Rice husk | 162.5 | 0.051 | NA | – | – | 1 | [90, 91] |

| Rice husk | 170 | 0.070 | 0.87 | 3600 | – | 1 | [92] |

| Coconut coir | 325 | 0.066 | NA | – | – | 1 | [53, 90] |

| Bagasse | 115 | 0.048 | NA | – | – | 1 | [9, 90] |

| Corn cob | 315 | 0.097 | NA | – | – | 1 | [90, 91] |

| Durian peel | 637.5 | 0.107 | NA | – | 1 | [90, 93] | |

| Oil palm leaves | 900 | 0.179 | NA | – | – | 1 | [94] |

| Cotton stalk | 300 | 0.07 | NA | – | – | 1 | [95] |

| Durian peel and coconut coir | 583.5 | 0.1 | NA | – | – | 1 | [86, 90] |

| Kenaf board | 100 | 0.054 | 0.95 (4 cm) | 2000 | – | 1 | [17] |

| Linen fibers | 35 | 0.038 | NA | – | – | 1 | [73] |

| Corn cob | – | – | 0.153–0.450 | 125–2000 | 1 | – | [96] |

| Shredded sunflower stalks | – | – | 0.139–0.481 | 125–2000 | 1 | – | [96] |

| Sheep wool balls | – | – | 0.107–0.456 | 125–2000 | 1 | – | [96] |

N.A. not available

*aData from existing NFI materials (Spanish)

*btwo different commercial breed mixes

*cspongy parts of sunflower stalks, cotton waste, textile waste, stubble fibers, and epoxy

Table 8.

Thermal and sound properties of insulation materials made from industrial solid waste

| Type | Materials | Density (kg m−3) |

Conductivity (Wm−1 K−1) | Sound absorption (α) |

sound absorption frequencies (Hz) | Composite | Particleboard | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial waste | Fly ash board *a | 850 | 0.3 | 0.8 (4 cm) | 1500 | 1 | [34] | |

| Fly ash board with tire fiber | – | 0.035 | NA | – | 1 | – | [13] | |

| Bottom ash-based concretes (1)*b | 765–779 | NA | 0.93–0.91 | 356–1241 | 1 | – | [79] | |

| Bottom ash-based concretes (2)*c | 1242–1255 | NA | 0.50–0.39 | 106–128 | 1 | – | [79] | |

| Recycled cardboard | – | 0.053–0.058 | 60 dB | 900–1600 | – | 1 | [16, 36] | |

| Shredded tire (90%) with elastomeric waste (10%) | 495 | 0.06 | 4 DLa | 100–5000 | – | 1 | [40] | |

| Shredded carpet (90%) with elastomeric waste (10%) | 366 | 0.06 | 2DLa (α > 0.9 in fiber length > 6 mm) | 100–5000 | – | 1 | [40] | |

| Chipboards (cotton waste, fly ash and barite) | – | 2.2 | NA | – | 1 | – | [41] | |

| Onion skin and peanut shell fibers, fly ash, pumice, perlite, barite, cement (C) and gypsum (G) | 1040 (G)-1330 (C) | 0.058 (G)-0.062 (C) | 0.16 (C)-0.1 (G) (kl s−1) | – | 1 | – | [60] | |

| Light weight concert with Cotton waste | 1050 | 0.2 | – | – | – | 1 | [15] | |

| Paper Mill Waste | – | 0.4 | – | – | – | 1 | [97] | |

| perlite wastes | 408–476.5 | 0.076–0.095 | – | – | – | 1 | [98] | |

| polystyrene | – | – | 0.123–0.447 | 125–2000 | 1 | – | [96] | |

| PET | – | – | 0.108–0.496 | 125–2000 | 1 | – | [96] |

N.A. not available

*afly ash board contain vermiculite, Gypsum, and fiber

*b7 mm > diameter of particle>2.5 mm

*cdiameter of particle<2.5 mm

Table 9.

Thermal and sound properties of insulation materials made from C&D and municipal solid waste

| Materials | Density (kg m−3) | Conductivity (Wm−1 K−1) | Sound absorption (α) | Composite | Particleboard | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycled mixed concretes | NA | 0.66 (H1) | 0.1 (H0), 0.15 (H1) in 1500 Hz and 0.25 (H0), 0.5 (H1) in 5000 Hz | – | 1 | [44, 99] |

| Construction waste wood cement composite | 1540 | 0.29 | NA | – | 1 | [45] |

| Recycled aggregate cement composite | 1619 | 0.73 | NA | 1 | – | [46] |

| Cement with wood byproduct (coarse sawdust 5%) | NA | 0.62 | NA | 1 | – | [42] |

| plaster and Wood Shavings (10%) | 1166 | 0.17 | 0.218 (500–2000 Hz) | 1 | – | [100] |

| plaster and Wood Shavings Perforated (10%) | <1166 | NA | 0.435 (500–2000 Hz) | 1 | – | [100] |

| plaster and Wood Shavings (20%) | 954 | 0.16 | 0.255 (500–2000 Hz) | 1 | – | [100] |

| plaster and Wood Shavings Perforated (20%) | <954 | NA | 0.439 (500–2000 Hz) | 1 | – | [100] |

| plaster and Sawdust (10%) | 1187 | 0.21 | 0.255 (500–2000 Hz) | 1 | – | [100] |

| plaster and Sawdust Perforated (10%) | <1187 | NA | 0.447 (500–2000 Hz) | 1 | – | [100] |

| plaster and Sawdust (20%) | 1044 | 0.17 | 0.360 (500–2000 Hz) | 1 | – | [100] |

| plaster and Sawdust Perforated(20%) | <1044 | NA | 0.473 (500–2000 Hz) | 1 | – | [100] |

| Marble powder (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35%) | 1590–2050 | 0.4 | NA | 1 | – | [101] |

| Glass powder (20–35%) and palm oil fly ash (20–35%) | 338.7–1628 | 0.39 | NA | 1 | – | [102] |

| Sawdust (5–20 vol%), wood ash (5–15 vol%), and lime mud (5-15 vol%) | 1380–2080 | 0.55–1.12 | NA | 1 | – | [103] |

N.A. not available

From MSW, the recycled cellulose aerogel, recycled PET, recycled wool, and woven fabric waste have good properties on thermal conductivity [104]. From the agricultural waste category, cellulose, sheep wool, kenaf board, cork, hemp, and wood fiber have good properties on thermal conductivity and hemp, kenaf fiber, and cellulose have good sound absorption properties. From industrial waste category, composite of fly ash, tire fiber, recycled cardboard, shredded carpet, tire, and recycled elastomeric waste have good properties on thermal conductivity, while fly ash and fiber tire, bottom ash based concrete, shredded tire, and elastomeric fiber have good sound absorption properties [105]. From C&D waste category, construction waste wool cement composite has a good property on thermal conductivity and recycled mixed concrete has a good sound absorption property in high frequency.

Conclusion

In this overview, it can be concluded that many wastes in the various categories and production source including municipal, agricultural, industrial, and C&D can be used as a thermal and sound insulation material. A common observation has been that with decreasing the density, thermal performance of materials generally increases. Moreover, with increasing the density, sound insulation property generally increased. Improved thermal conductivity, sound absorption and sound insulation properties resulted from the use of dense double walls filled with the porous materials. In general, increasing the open porosity leads to increase in sound absorption but in the cases that the open porosity was decreased, thermal conductivity decreased as well. It appears that utilization of two layers, one of which has open porosity and another having closed porosity with low density can improve thermal and sound absorption properties. In the majority of cases, thermal conductivity and sound absorption properties were improved with increasing the thickness of materials. As a result, it should be noted that the production of low thickness materials with better insulation properties could be considered as a research priority.

It is essential to conduct more investigation about the feasibility of utilizing municipal, agricultural, industrial, and C&D wastes as alternative materials in place of high cost synthetic raw materials, such as aggregates and synthetic insulation layers in buildings. Research can be done to enhance the physical and chemical properties of these alternative insulation layers. The different insulation layers must be made in a way that the disassembly and recycling of them be made more practical. Considering the environmental aspects, the combined use of natural and green materials in the future must attract more attention, in order to develop green buildings and promote recycling and re-utilization of all kinds of wastes.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 320 kb)

(PDF 320 kb)

(PDF 319 kb)

(PDF 320 kb)

(PDF 320 kb)

(PDF 321 kb)

(PDF 320 kb)

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Corscadden K, Biggs J, Stiles D. Sheep's wool insulation: a sustainable alternative use for a renewable resource? Resour Conserv Recycl. 2014;86:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2014.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Homoud MS. Performance characteristics and practical applications of common building thermal insulation materials. Build Environ. 2005;40(3):353–366. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2004.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuchí A, Sweatman P. Una visión-país para el sector de la edificación en España. Hoja de ruta para un nuevo sector de la vivienda. 2011. pp. 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asdrubali F, D'Alessandro F, Schiavoni S. A review of unconventional sustainable building insulation materials. Sustain Mater Technol. 2015;4:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peruzzi L, Salata F, de Lieto Vollaro A, de Lieto Vollaro R. The reliability of technological systems with high energy efficiency in residential buildings. Energy and Buildings. 2014;68:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2013.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zach J, Hroudová J, Brožovský J, Krejza Z, Gailius A. Development of thermal insulating materials on natural base for thermal insulation systems. Procedia Engineering. 2013;57:1288–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2013.04.162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rushforth I, Horoshenkov K, Miraftab M, Swift M. Impact sound insulation and viscoelastic properties of underlay manufactured from recycled carpet waste. Appl Acoust. 2005;66(6):731–749. doi: 10.1016/j.apacoust.2004.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez-Garcia J, Lippke B, Briggs D, Wilson JB, Bowyer J, Meil J. The environmental performance of renewable building materials in the context of residential construction. Wood Fiber Sci. 2007;37:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinto J, Paiva A, Varum H, Costa A, Cruz D, Pereira S, Fernandes L, Tavares P, Agarwal J. Corn's cob as a potential ecological thermal insulation material. Energy and Buildings. 2011;43(8):1985–1990. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2011.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Binici H, Aksogan O, Shah T. Investigation of fibre reinforced mud brick as a building material. Constr Build Mater. 2005;19(4):313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2004.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korjenic A, Petránek V, Zach J, Hroudová J. Development and performance evaluation of natural thermal-insulation materials composed of renewable resources. Energy and Buildings. 2011;43(9):2518–2523. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2011.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paiva A, Pereira S, Sá A, Cruz D, Varum H, Pinto J. A contribution to the thermal insulation performance characterization of corn cob particleboards. Energy and Buildings. 2012;45:274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2011.11.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van de Lindt J, Carraro J, Heyliger P, Choi C. Application and feasibility of coal fly ash and scrap tire fiber as wood wall insulation supplements in residential buildings. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2008;52(10):1235–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2008.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raut S, Ralegaonkar R, Mandavgane S. Development of sustainable construction material using industrial and agricultural solid waste: a review of waste-create bricks. Constr Build Mater. 2011;25(10):4037–4042. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2011.04.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aghaee K, Foroughi M. Mechanical properties of lightweight concrete partition with a core of textile waste. Advances in Civil Engineering. 2013;2013:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2013/482310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asdrubali F, Pisello A, D'alessandro F, Bianchi F, Fabiani C, Cornicchia M, et al. Experimental and numerical characterization of innovative cardboard based panels: thermal and acoustic performance analysis and life cycle assessment. Build Environ. 2016;95:145–159. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2015.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ingrao C, Giudice AL, Tricase C, Rana R, Mbohwa C, Siracusa V. Recycled-PET fibre based panels for building thermal insulation: environmental impact and improvement potential assessment for a greener production. Sci Total Environ. 2014;493:914–929. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fangueiro R, Marques P, Pereira CG. Directionally oriented fibrous structures for llghtweight concrete elements reinforcement. ICSA. 2010. pp. 1462–1469. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hejazi SM, Sheikhzadeh M, Abtahi SM, Zadhoush A. A simple review of soil reinforcement by using natural and synthetic fibers. Constr Build Mater. 2012;30:100–116. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2011.11.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.del Mar Barbero-Barrera M, Pombo O, de los Angeles Navacerrada M. textile fibre waste bindered with natural hydraulic lime. Compos Part B. 2016;94:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benazzouk A, Douzane O, Mezreb K, Laidoudi B, Quéneudec M. Thermal conductivity of cement composites containing rubber waste particles: experimental study and modelling. Constr Build Mater. 2008;22(4):573–579. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2006.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Binici H, Aksogan O. Eco-friendly insulation material production with waste olive seeds, ground PVC and wood chips. Journal of Building Engineering. 2016;5:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jobe.2016.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patnaik A, Mvubu M, Muniyasamy S, Botha A, Anandjiwala RD. Thermal and sound insulation materials from waste wool and recycled polyester fibers and their biodegradation studies. Energy and Buildings. 2015;92:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2015.01.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Del Rey R, Alba J, Arenas JP, Sanchis VJ. An empirical modelling of porous sound absorbing materials made of recycled foam. Appl Acoust 2012;73(6–7):604–609.

- 25.Yeon J-O, Kim K-W, Yang K-S, Kim J-M, Kim M-J. Physical properties of cellulose sound absorbers produced using recycled paper. Constr Build Mater. 2014;70:494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.07.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ducman V, Mladenovič A, Šuput J. Lightweight aggregate based on waste glass and its alkali–silica reactivity. Cem Concr Res. 2002;32(2):223–226. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8846(01)00663-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luamkanchanaphan T, Chotikaprakhan S, Jarusombati S. A study of physical, mechanical and thermal properties for thermal insulation from narrow-leaved cattail fibers. APCBEE Procedia. 2012;1:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.apcbee.2012.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mati-Baouche N, De Baynast H, Lebert A, Sun S, Lopez-Mingo CJS, Leclaire P, et al. Mechanical, thermal and acoustical characterizations of an insulating bio-based composite made from sunflower stalks particles and chitosan. Ind Crop Prod. 2014;58:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lertsutthiwong P, Khunthon S, Siralertmukul K, Noomun K, Chandrkrachang S. New insulating particleboards prepared from mixture of solid wastes from tissue paper manufacturing and corn peel. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99(11):4841–4845. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Binici H, Eken M, Kara M, Dolaz M, editors. An environment-friendly thermal insulation material from sunflower stalk, textile waste and stubble fibers: International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA); 2013, 2013. IEEE

- 31.Panyakaew S, Fotios S, editors. 321: Agricultural Waste Materials as Thermal Insulation for Dwellings in Thailand: Preliminary Results. 25 Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture, Dublin; 2008.

- 32.Herrero S, Mayor P, Hernández-Olivares F. Influence of proportion and particle size gradation of rubber from end-of-life tires on mechanical, thermal and acoustic properties of plaster–rubber mortars. Mater Des. 2013;47:633–642. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2012.12.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kearsley E, Wainwright P. The effect of high fly ash content on the compressive strength of foamed concrete. Cem Concr Res. 2001;31(1):105–112. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8846(00)00430-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leiva C, Arenas C, Vilches L, Alonso-Fariñas B, Rodriguez-Galán M. Development of fly ash boards with thermal, acoustic and fire insulation properties. Waste Manag. 2015;46:298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Y-l Y, Li G-z, X-s X, Z-j Z. Properties and microstructures of plant-fiber-reinforced cement-based composites. Cem Concr Res. 2000;30(12):1983–1986. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8846(00)00376-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asdrubali F, Pisello A, D’Alessandro F, Bianchi F, Cornicchia M, Fabiani C. Innovative cardboard based panels with recycled materials from the packaging industry: thermal and acoustic performance analysis. Energy Procedia. 2015;78:321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2015.11.652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Binici H, Aksogan O. Insulation material production from onion skin and peanut shell fibres, fly ash, pumice, perlite, barite, cement and gypsum. Materials Today Communications. 2017;10:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2016.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.NGouloure ZN, Nait-Ali B, Zekeng S, Kamseu E, Melo U, Smith D, et al. Recycled natural wastes in metakaolin based porous geopolymers for insulating applications. Journal of Building Engineering. 2015;3:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jobe.2015.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Posi P, Ridtirud C, Ekvong C, Chammanee D, Janthowong K, Chindaprasirt P. Properties of lightweight high calcium fly ash geopolymer concretes containing recycled packaging foam. Constr Build Mater. 2015;94:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.07.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benkreira H, Khan A, Horoshenkov KV. Sustainable acoustic and thermal insulation materials from elastomeric waste residues. Chem Eng Sci. 2011;66(18):4157–4171. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2011.05.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Binici H, Gemci R, Kucukonder A, Solak HH. Investigating sound insulation, thermal conductivity and radioactivity of chipboards produced with cotton waste, fly ash and barite. Constr Build Mater. 2012;30:826–832. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2011.12.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corinaldesi V, Mazzoli A, Siddique R. Characterization of lightweight mortars containing wood processing by-products waste. Constr Build Mater. 2016;123:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laukaitis A, Žurauskas R, Kerien J. The effect of foam polystyrene granules on cement composite properties. Cem Concr Compos. 2005;27(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2003.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leiva C, Solís-Guzmán J, Marrero M, Arenas CG. Recycled blocks with improved sound and fire insulation containing construction and demolition waste. Waste Manag. 2013;33(3):663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang L, Chen SS, Tsang DC, Poon CS, Shih K. Value-added recycling of construction waste wood into noise and thermal insulating cement-bonded particleboards. Constr Build Mater. 2016;125:316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.08.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu L, Dai J, Bai G, Zhang F. Study on thermal properties of recycled aggregate concrete and recycled concrete blocks. Constr Build Mater. 2015;94:620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.07.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.EN B. 12664 . Thermal performance of building materials and products. Determination of thermal resistance by means of guarded hot plate and heat flow meter methods dry and moist products of medium and Low thermal resistance. London: British Standards Institution; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 48.ISO E. 12667 . Dry and moist products of medium and low thermal resistance. 2001. Thermal performance of building materials and products-determination of thermal resistance by means of guarded hot plate and heat flow meter methods-products of high and medium thermal resistance. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Standard A. C518–10, 2010,“Standard Test Method for Steady-State Thermal Transmission Properties by Means of the Heat Flow Meter Apparatus. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2010, 10.1520/C0518-10.

- 50.Vollaro RDL, Guattari C, Evangelisti L, Battista G, Carnielo E, Gori P. Building energy performance analysis: a case study. Energy and Buildings. 2015;87:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2014.10.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li FG, Smith A, Biddulph P, Hamilton IG, Lowe R, Mavrogianni A, et al. Solid-wall U-values: heat flux measurements compared with standard assumptions. Build Res Inf. 2015;43(2):238–252. doi: 10.1080/09613218.2014.967977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.ISO E. 13786: 2007--thermal performance of building components--dynamic thermal characteristics--calculation methods. International Organization for Standardization 2007.

- 53.Onésippe C, Passe-Coutrin N, Toro F, Delvasto S, Bilba K, Arsène M-A. Sugar cane bagasse fibres reinforced cement composites: thermal considerations. Compos A: Appl Sci Manuf. 2010;41(4):549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesa.2010.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Madurwar MV, Ralegaonkar RV, Mandavgane SA. Application of agro-waste for sustainable construction materials: a review. Constr Build Mater. 2013;38:872–878. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.ISO B. 717-1: 1997 Acoustics-Rating of sound insulation in buildings and of building elements. Part 1. Airborne sound insulation. European standard. 1996.

- 56.ISO E. 10140–2: 2010,". ISO Acoustics--Laboratory measurement of sound insulation of building elements--Part 2: Measurement of airborne sound insulation. 2010:1–13.

- 57.Pispola G, Horoshenkov KV, Asdrubali F. Transmission loss measurement of consolidated granular media (L) J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;117(5):2716–2719. doi: 10.1121/1.1886365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Normalización OId . ISO 10534-2 acoustics, determination of sound Abosorption coefficient and impedance in impedance tubes: part 2, transfer-function method. ISO. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGrory M, Cirac DC, Gaussen O, Cabrera D, Engineers G, editors. Sound absorption coefficient measurement: re-examining the relationship between impedance tube and reverberant room methods. In: Proceedings of acoustics, vol. 2012.

- 60.Schiavoni S, Bianchi F, Asdrubali F. Insulation materials for the building sector: a review and comparative analysis. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2016;62:988–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.05.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hadded A, Benltoufa S, Fayala F, Jemni A. Thermo physical characterisation of recycled textile materials used for building insulating. Journal of Building Engineering. 2016;5:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jobe.2015.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tiuc A-E, Vermeşan H, Gabor T, Vasile O. Improved sound absorption properties of polyurethane foam mixed with textile waste. Energy Procedia. 2016;85:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2015.12.245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Briga-Sa A, Nascimento D, Teixeira N, Pinto J, Caldeira F, Varum H, et al. Textile waste as an alternative thermal insulation building material solution. Constr Build Mater. 2013;38:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.08.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bekhta P, Dobrowolska E. Thermal properties of wood-gypsum boards. Holz als Roh-und Werkstoff. 2006;64(5):427–428. doi: 10.1007/s00107-005-0074-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ng S-C, Low K-S. Thermal conductivity of newspaper sandwiched aerated lightweight concrete panel. Energy and Buildings. 2010;42(12):2452–2456. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2010.08.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Panyakaew S, Fotios S. New thermal insulation boards made from coconut husk and bagasse. Energy and Buildings. 2011;43(7):1732–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2011.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Demirboğa R, Gül R. The effects of expanded perlite aggregate, silica fume and fly ash on the thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete. Cem Concr Res. 2003;33(5):723–727. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8846(02)01032-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sukontasukkul P. Use of crumb rubber to improve thermal and sound properties of pre-cast concrete panel. Constr Build Mater. 2009;23(2):1084–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2008.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maderuelo-Sanz R, Nadal-Gisbert AV, Crespo-Amorós JE, Parres-García F. A novel sound absorber with recycled fibers coming from end of life tires (ELTs) Appl Acoust. 2012;73(4):402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.apacoust.2011.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ruiz-Herrero JL, Nieto DV, López-Gil A, Arranz A, Fernández A, Lorenzana A, et al. Mechanical and thermal performance of concrete and mortar cellular materials containing plastic waste. Constr Build Mater. 2016;104:298–310. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sequeira S, Evtuguin DV, Portugal I. Preparation and properties of cellulose/silica hybrid composites. Polym Compos. 2009;30(9):1275–1282. doi: 10.1002/pc.20691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nguyen ST, Feng J, Ng SK, Wong JP, Tan VB, Duong HM. Advanced thermal insulation and absorption properties of recycled cellulose aerogels. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2014;445:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2014.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sampathrajan A, Vijayaraghavan N, Swaminathan K. Mechanical and thermal properties of particle boards made from farm residues. Bioresour Technol. 1992;40(3):249–251. doi: 10.1016/0960-8524(92)90151-M. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bakhshoodeh R, Alavi N, Mohammadi AS, Ghanavati H. Removing heavy metals from Isfahan composting leachate by horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetland. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2016;23(12):12384–12391. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Palumbo M, Avellaneda J, Lacasta A. Availability of crop by-products in Spain: new raw materials for natural thermal insulation. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2015;99:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Putra A, Abdullah Y, Efendy H, Farid WM, Ayob MR, Py MS. Utilizing sugarcane wasted fibers as a sustainable acoustic absorber. Procedia Engineering. 2013;53:632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2013.02.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jayaranjan MLD, Van Hullebusch ED, Annachhatre AP. Reuse options for coal fired power plant bottom ash and fly ash. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2014;13(4):467–486. doi: 10.1007/s11157-014-9336-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kizgut S, Cuhadaroglu D, Samanli S. Stirred grinding of coal bottom ash to be evaluated as a cement additive. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects. 2010;32(16):1529–1539. doi: 10.1080/15567030902780378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arenas C, Leiva C, Vilches L, Ganso JG. Approaching a methodology for the development of a multilayer sound absorbing device recycling coal bottom ash. Appl Acoust. 2017;115:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.apacoust.2016.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu MYJ, Alengaram UJ, Jumaat MZ, Mo KH. Evaluation of thermal conductivity, mechanical and transport properties of lightweight aggregate foamed geopolymer concrete. Energy and Buildings. 2014;72:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2013.12.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Agamuthu P. Challenges in sustainable management of construction and demolition waste. London: SAGE Publications Sage UK; 2008. Challenges in sustainable management of construction and demolition waste. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mercader-Moyano P, Marrero M, Solís-Guzmán J. Montes Delgado MVd, Ramírez de Arellano Agudo A. Cuantificación de los recursos materiales consumidos en la ejecución de la cimentación. Inf Constr. 2010;62(517):125–132. doi: 10.3989/ic.09.000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kanellopoulos A, Nicolaides D, Petrou MF. Mechanical and durability properties of concretes containing recycled lime powder and recycled aggregates. Constr Build Mater. 2014;53:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.11.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.EPD H. Monitoring of Solid Waste in Hong Kong: Waste Statistics for 2013. Environmental Protection Department, Hong Kong. 2015.

- 85.Yu H-X, Fang C-R, Xu M-P, Guo F-Y, Yu W-J. Effects of density and resin content on the physical and mechanical properties of scrimber manufactured from mulberry branches. J Wood Sci. 2015;61(2):159–164. doi: 10.1007/s10086-014-1455-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Asdrubali F. Survey on the acoustical properties of new sustainable materials for noise control. Tampere: Proceedings of Euronoise; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Asdrubali F, editor. The role of life cycle assessment (LCA) in the design of sustainable buildings: thermal and sound insulating materials. Euronoise 2009; 2009.

- 88.Bribián IZ, Capilla AV, Usón AA. Life cycle assessment of building materials: comparative analysis of energy and environmental impacts and evaluation of the eco-efficiency improvement potential. Build Environ. 2011;46(5):1133–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2010.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Binici H, Eken M, Dolaz M, Aksogan O, Kara M. An environmentally friendly thermal insulation material from sunflower stalk, textile waste and stubble fibres. Constr Build Mater. 2014;51:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.10.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Xu J, Sugawara R, Widyorini R, Han G, Kawai S. Manufacture and properties of low-density binderless particleboard from kenaf core. J Wood Sci. 2004;50(1):62–67. doi: 10.1007/s10086-003-0522-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yarbrough DW, Wilkes KE, Olivier PA, Graves RS, Vohra A. Apparent thermal conductivity data and related information for rice hulls and crushed pecan shells. Thermal Conductivity. 2005;27:222–230. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Buratti C, Belloni E, Lascaro E, Merli F, Ricciardi P. Rice husk panels for building applications: thermal, acoustic and environmental characterization and comparison with other innovative recycled waste materials. Constr Build Mater. 2018;171:338–349. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.03.089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Al-Juruf R, Ahmed F, Alam I, Abdel-Rahman H. Development of heat insulating materials using date palm leaves. J Therm Insul. 1988;11(3):158–164. doi: 10.1177/109719638801100304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.X-y Z, Zheng F, Li H-g, C-l L. An environment-friendly thermal insulation material from cotton stalk fibers. Energy and Buildings. 2010;42(7):1070–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2010.01.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Khedari J, Nankongnab N, Hirunlabh J, Teekasap S. New low-cost insulation particleboards from mixture of durian peel and coconut coir. Build Environ. 2004;39(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2003.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Oancea I, Bujoreanu C, Budescu M, Benchea M, Grădinaru CM. Considerations on sound absorption coefficient of sustainable concrete with different waste replacements. J Clean Prod. 2018;203:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pathak CS, Mandavgane SA. Application of recycle paper mill waste (rpmw) as a thermal insulation material. Waste and biomass valorization. 2018. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tsaousi G, Profitis L, Douni I, Chatzitheodorides E, Panias D. Development of lightweight insulating building materials from perlite wastes. Mater Constr. 2019;69(333):175. doi: 10.3989/mc.20198.12517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Park SB, Seo DS, Lee J. Studies on the sound absorption characteristics of porous concrete based on the content of recycled aggregate and target void ratio. Cem Concr Res. 2005;35(9):1846–1854. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pedreño-Rojas M, Morales-Conde M, Pérez-Gálvez F, Rodríguez-Liñán C. Eco-efficient acoustic and thermal conditioning using false ceiling plates made from plaster and wood waste. J Clean Prod. 2017;166:690–705. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Phonphuak N, Kanyakam S, Chindaprasirt P. Utilization of waste glass to enhance physical–mechanical properties of fired clay brick. J Clean Prod. 2016;112:3057–3062. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Raut AN, Gomez CP. Development of thermally efficient fibre-based eco-friendly brick reusing locally available waste materials. Constr Build Mater. 2017;133:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.12.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Madrid M, Orbe A, Carré H, García Y. Thermal performance of sawdust and lime-mud concrete masonry units. Constr Build Mater. 2018;169:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.02.193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bakhshoodeh R, Alavi N, Paydary P. Composting plant leachate treatment by a pilot-scale, three-stage, horizontal flow constructed wetland in Central Iran. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24(30):23803–23814. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-0002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Singh H, Singh Y. Editors. Applications of recycled and waste materials in infrastructure projects. International conference on sustainable waste management through design; 2018. Springer.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 320 kb)

(PDF 320 kb)

(PDF 319 kb)

(PDF 320 kb)

(PDF 320 kb)

(PDF 321 kb)

(PDF 320 kb)