Abstract

Purpose

Petroleum hydrocarbons have created numerous problems for water resources. The main objective of this study was focused on the application of advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) in treatment of effluent of petroleum contaminated soil washing operation.

Methods

The AOP process in the present study was run with Fe2+/H2O2 (Fenton’s reagent), Fe2+/H2O2/UV (photo-Fenton’s reagent) and UV lamp (medium pressure mercury lamp, 400 W) in the batch-mode reactor at laboratory-scale.

Results

Various parameters and optimized values which could maximize the removal efficiency of COD were: Fe2+ = 0.1 g/L, H2O2 = 1 g/L, pH = 3 and irradiation time of 120 min. Under the optimal conditions, the removal efficiency of COD and TOC were achieved 86.3% and 68% respectively. The results showed that the reaction of the oxidation of diesel fuel by Fenton and photo-Fenton systems followed second-order kinetic model with reaction rate constants (k) of 7 × 10−6 and 3 × 10−6 l/mg min−1 respectively.

Conclusions

The photo-Fenton process can be used as an effective and environmental friendly method in the degradation of petroleum organic compounds.

Keywords: Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), Fe2+/H2O2/UV process, Fe2+/H2O2 process, Chemical oxygen demand (COD), Total organic carbon (TOC)

Introduction

With increasing the crude oil production and petroleum products, petroleum hydrocarbons have become one of the most common pollutants in the soil. These compounds may enter the soil due to leakage, overflow or other events, industrial effluents; or in the form of unwanted byproducts resulting from industrial activities [1]. Such soils cause problems in agricultural activities and ground water quality [2, 3]. Diesel is one of the crude oil fractions and most consuming fuels that may be released into the environment due to storage or misuse. Diesel is mainly a mixture of normal, iso and cyclo-hydrocarbons with 8 to 28 carbon atoms [4]. Due to the speed and relative ease, soil washing is a preferred method for treating such contaminated soils [2, 3]. Soil washing technology with using of different surfactants, raises the solubility of petroleum hydrocarbons in the soil. In this process, the contaminant is transported from the solid phase to the liquid phase [5]. Tween 80 with a very strong absorption capacity of dissolve hydrocarbons as a non-ionic surfactant has been studied to improve the soil washing process [6]. Advanced oxidation processes are an effective way to oxidize organic pollutants to final products such as H2O and CO2 [7]. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have been investigated as a substitute for commonly used treatment methods for petroleum industries effluents. In these processes reactive intermediates such as hydroxyl radicals, break down the hydrocarbons [8, 9] In such processes UV [10], O3/H2O2 [11], O3/UV [10], TiO2 photo-catalysis [12, 13] and Fenton and photo-Fenton are used oxidation agents [14]. As shown in Eq. 1 [15], the Fenton oxidation process is a catalytic H2O2 reaction with iron ions [16] that produces O●H as reactive species [17]:

| 1 |

| 2 |

The presence of hydroxyl radicals in the Fenton reaction has been proven by spin-trapping experiments [18] The Photo-Fenton reaction is a combination of Fenton reagents and ultraviolet radiation that release more radical O●H through the following two reactions: (a) Reduction of Fe3+ ions to Fe2+ as shown in Eq. 3 [19] and (b) Photolysis of peroxide at shorter wavelengths (Eq. 4):

| 3 |

| 4 |

Recently, advanced oxidation processes have become more prominent in refining industrial wastewater due to their high speed and efficiency [20–22]. Also, photo-Fenton process can be considered as one of the most attractive and most successful methods used to remove environmental pollutants [23–27].

The aim of this study is to remove petroleum hydrocarbons in the waste water derived from washing contaminated soil. In this study, the photo-Fenton process in diesel elimination was used to actual soil washing wastewater for the first time. In this regard, the efficiency of both soil washing processes by surfactant and treatment of produced effluent by photo-Fenton system as one of the forms of advanced oxidation processes was investigated. On the other hand, this process is widely used for other organic pollutants such as antibiotics and phenol, but little information is available for the removal of diesel.

Material and methods

Reagents

N-hexane (Merck) was used for the extraction of diesel. FeSO4.7H2O (Merck) and H2O2 (30% w/v) (Merck) were used in the degradation experiment as the source of hydroxyl radicals. pH of the solutions was adjusted by the addition of H2SO4 (Merck) and NaOH (Merck). NaCl (Merck) was used to reduce emulsion formation during liquid/liquid extraction process. Tween 80 was purchased from Merck co. as synthetic nonionic surfactant in the soil washing experiments.

Soil washing

Sampling and soil preparation

In this study, soil samples were collected from petrol distribution and reservoirs center in Zanjan city (Table 1). The samples were screened by a sieve with pores of 2 mm. 500 g of this soil sample was weighed and washed with distilled water. For this purpose, contaminated soil was rinse off in two steps. For the first step, 125 g of soil samples and 500 ml of distilled water were added to each of four 1000 ml beakers, then, the beaker contents were well mixed. For Stage 2, the supernatants in the beakers (after settling) were evacuated and the above operations repeated. The purpose of these steps was to remove plant and other materials from the soil sample. Then, the soil samples were placed at room temperature for 24 h to lose their moisture. Finally, the specimens were put at 50 °C for 2 h to dry completely. Samples were stored at 4 °C in the refrigerator to be analyzed afterward.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the soil studied

| Organic matter (%) | 6.2 |

|---|---|

| Sand (%) | 38 |

| Silt (%) | 51 |

| Clay (%) | 11 |

| pH (H2O) | 8.7 |

| Density (kgm−3) | 1450 |

| COD (mgkg−1) | 5100–5800 |

Soil washing operation

100 g of dried soil was poured into 2000 mL flasks and 1000 ml distilled water and 1 mL tween 80 were added. The samples were then placed in a shaker incubator at 250 rpm, 2 h and 26.5 °C. After completion of these steps, the flasks were kept at rest for one night to settling. Afterwards, the effluent was separated from the soil sample by overflowing and the soil was poured onto the watch glass to lose moisture at room temperature and then placed in an oven in 50 °C for 2 h to dry completely and ready to be analyzed. The results showed that TPH (Total petroleum Hydrocarbon) removal by nonionic surfactants (Tween 80) in optimal condition was 70–80%. The effluent of this operation was used in the batch-mode photo reactor.

Batch-mode photo reactor

The used reactor in this study with a volume of 2 l is shown in Fig. 1. It contains, a medium pressure UV lamp (400 watts power, radiation dose rate of 3800 μw/cm2 after 10 min, model: UVOX, type: UVC and manufacturer: Arda France) as the source of radiation. The reactor is made up of an internal chamber in which the lamp is placed in the middle with two layers of quartz coated. By passing cool water from these two- coated layers, the cooling operation of the sample is down and the test conditions maintained at ambient temperature. Inside the reactor, a magnetic stirrer was used for complete mixing.

Fig. 1.

Set up of batch-mode photoreactor. (1. Cooling water inlet; 2. Cooling water Outlet; 3. Lamp chamber; 4. UV lamp; 5. Reaction chamber; 6. Dual quartz coverage; 7. Magnet; 8. Sampling valve)

The effluent of washing of petroleum contaminated soil with 3880–4500 mg/L of COD was used in treatments. Experiments were carried out using 500 mL of effluent in the presence of FeSO4.7H2O solution (0.05–0.15 g/L), H2O2 (0.5–1.5 g/L) and different pH in reaction chamber. Samples were collected every 20 min and its COD was determined. Different experimental tests were carried out to determine the effectiveness of operating parameters, including pH, initial Fe ions and peroxide hydrogen concentration, degradation systems, and reaction time on COD and TOC removal. In each test series one parameter was variable and others were constant.

Chemical analysis

TPH measurement in washed soil

Extraction of diesel from the soil was carried out by adding 10 mL of n-hexane/dichloromethane solution (1:1), and 1.0 g sodium chloride, to 10.0 g of prepared soil in an airtight seal glass tube. The mixture was mechanically stirred at 120 rpm for 2 h, then centrifuged and the extract collected. This extraction process was repeated twice. The soil TPH was measured by gas chromatography using an Agilent chromatograph equipped with a HP-5 capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm) and a flame ionization detector (FID) according the test method No. 8015C of EPA.

COD and TOC analysis

In this study, COD was used as an indicator of the amount of organic pollutants in contaminated wastewaters. According to previous studies [28, 29], Fenton and photo-Fenton reactions cannot proceed at pH > 10; therefore, the reaction was adjusted instantly by adding NaOH to the reaction samples before chemical oxygen demand (COD) analysis. COD of the effluent was measured before and after of photo-Fenton process. The Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) and total organic carbon (TOC) were measured using spectrophotometric method (model HACH DR-5000 and Shimadzu TOC-5000A analyzer) as organic compound indexes [30].

Results and discussion

The effects of initial Fe ions concentration

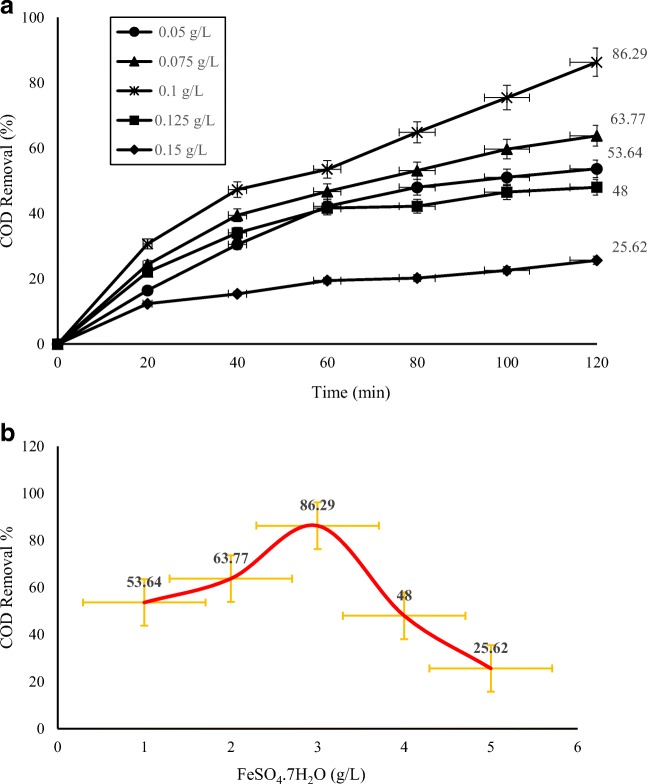

In the first experiments, the optimum initial Fe ion concentration was determined at pH 3 and 25 °C. As illustrated in Fig. 2,a-b, the optimum Fe2+ concentration was found to be 0.1 g/L which resulted in 86.3% COD removal after 120 min of irradiation time. Exceeding the concentration of Fe2+ has a negative effect on the reaction kinetics. The main reason is the fact of reduction the absorption of UV since increasing in iron concentration causes a brown turbidity, which in turn reduces the production of O●H. Fe2+ also reacts with O●H and deactivates them well and can inhibit the reaction rate [27, 31].

Fig. 2.

a Effect of Fe2+ concentration on COD removal in the photo-Fenton process. (UV = 400 W, H2O2 = 1 g/L, pH = 3, COD0 = 3880–4500 mg/L). b COD removal by photo-Fenton process with different dosage of FeSO4.7H2O within 120 min. (UV = 400 W, H2O2 = 1 g/L, pH = 3)

By increasing Fe2+ dose up to 0.1 g/L, the COD removal decreased at the adjusted conditions, after 120 min of reaction time. These observations conform with the results of Kositzi [32] and Tony [33]. In addition, the concentration of Fe2+ should be low because economic and environmental reasons [34].

The effect of initial concentration of peroxide hydrogen

To elucidate the role of H2O2 concentration on the photocatalytic degradation of soil washing wastewater, some experiments were carried out at constant initial pH 3, Fe2+ dose (0.1 g/L) and 25 °C in irradiation time of 120 min. As illustrated in Fig. 3,a-b, photodegradation efficiency using 0.5 and 0.75 g/L of H2O2 were approximately 51 and 65% respectively. Also, this amount of degradation yield at this time was reached to 86.3% when the H2O2 increased from 0.75 to 1 g/L. It is found out that, the optimum H2O2 concentration is 1 g/L which is explained by the effect of the additionally O●H production. Since the amount of generated O●H in the photo-Fenton reaction depends directly on the concentration of H2O2, the H2O2 concentration is an essential factor in the development of the reaction. However, the excessive increase in H2O2 concentration reduces the reaction efficiency by trapping O●H by additional H2O2 molecules [29, 35, 36]. It is reported that the excess H2O2 reacts with the hydroxyl radicals and produces radical hydroperoxyl (HO.2). This effect is named scavenging effect. The hydroperoxyl radicals has lower oxidation potential than hydroxyl radicals and moreover, hydroperoxyl radicals recombine with hydroxyl radicals (Eqs. 5–7) [37–39].

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

Fig. 3.

a Effect of H2O2 concentration on COD removal in the photo-Fenton process. (UV = 400 W, (FeSO4.7H2O)opt = 0.1 g/L, pH = 3). b COD removal by photo-Fenton process with different dosage of H2O2 within 120 min. (UV = 400 W, (FeSO4.7H2O)opt = 0.1 g/L, pH = 3)

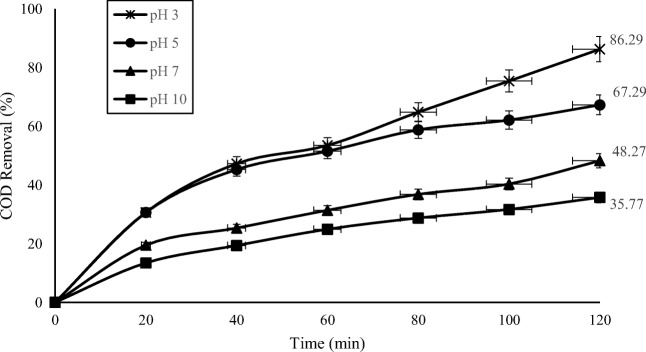

The effect of pH value

According to Fig. 4, a maximum COD removal of 86.3% was obtained at pH 3. Many studies have examined the effect of pH in the treatment of oil waste through the photo-Fenton system [10, 20, 21]. In addition, inorganic carbon concentration and Fe (II) hydrolytic speciation are strongly influenced by the pH value. The activity of photo-Fenton system is maximum within the pH range of 2.8 to 3. pH affects the oxidation efficiency through the effect on the production of less photoactive form of hydroxide (Fe(OH2)) [21, 40]. At pH values higher than 6, iron precipitates in the form of hydroxide, as a result of reducing available Fe (II) and reducing the transmission of ultraviolet radiation, degradation will be greatly reduced. The dissociation and spontaneous decomposition of hydrogen peroxide is another reason for the inefficiency of degradation at high pH values [27, 40].

Fig. 4.

Effect of pH on COD removal in the photo-Fenton process. (UV = 400 W, (H2O2)opt = 1 g/L, (FeSO4.7H2O)opt = 0.1 g/L)

For pH values below 3, the hydroxyl radical production will be reduced due to hydroxyl-radicals scavenging by H+ ions [41]. In addition, the activity of Fenton in acidic medium is low because the generation of stable oxonium ions (H3O2+) [35].

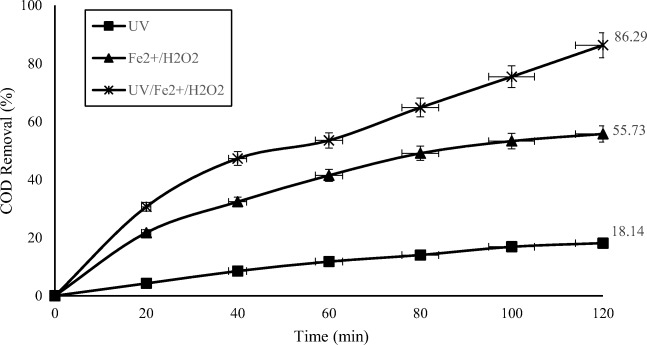

Comparison of different degradation systems

In this study, the efficacy of 3 methods of UV, Fe2+/ H2O2 and, UV/ Fe2+/H2O2, for refining effluent of petroleum contaminated soils washing operation, were compared. According to the results of this experiment during 2 h, UV radiation alone does not have any significant effect on the removal of organic compounds. According to the Fig. 5, the removal efficiency of UV radiation alone was 18.14%. As previous studies have also shown, ultraviolet photolysis alone was not able to completely degraded organic pollutants [42, 43]. In Chiavone’s study, when UV radiation was alone used for treating diesel contaminated wastewaters, a removal efficiency of 28% was observed. The difference is due to the fact that in Chiavone’s study, synthetic wastewater with a low turbidity level was used [14]. The application of Fenton (Fe/H2O2) and photo-Fenton (UV/Fe/H2O2) processes had a removal efficiency of 55.7% and 86%, respectively (Fig. 5) which H2O2 plays a major role in both processes because, it is a strong oxidant and produces hydroxyl radicals. The efficiency of Fenton process for the removal of diesel was less than the process of photo-Fenton which is similar to the previous results obtained in other studies [44, 45]. In comparison, the photo-Fenton system has the benefits of more efficiency and also the need for lower iron content, and subsequently low sludge production [14, 21, 46].

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the performance of different processes (alone) for COD removal. (UV = 400 W, (H2O2)opt = 1 g/L, (FeSO4.7H2O)opt = 0.1 g/L, pH = 3)

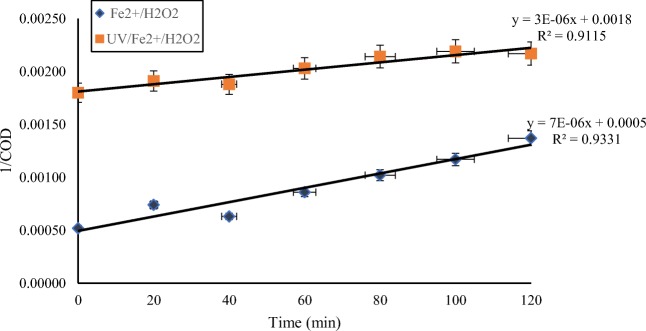

Kinetic study of various degradation systems

In the present study first- and second- order reactions kinetics were used to study the COD removal kinetics by Fenton, photo-Fenton and UV light oxidation processes. The expressions guiding the reaction kinetics are presented below:

First-order reaction kinetics:

| 8 |

Second order reaction kinetics:

| 9 |

where k1 (min−1) and k2 (l/mg min−1) represent the kinetic rate constants of first- and second-order reaction kinetics, respectively and t is the reaction time [47].

The following linier equations are derived from eqs. 5 and 6:

| 10 |

| 11 |

The values of the regression coefficients for second order of Fenton and photo-Fenton processes were 0.93 and 0.91 respectively (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Determination of second-order rate constants (k) in removal of COD by Fe/H2O2 and UV/Fe/H2O2 systems in the optimal conditions. (UV = 400 W, (H2O2)opt = 1 g/L, (FeSO4.7H2O)opt = 0.1 g/L, pH = 3)

Similar results were received in the studies of Hameed et.al [48] and Sekaran et.al [49] While most researchers have shown that the Fenton oxidation process follows the first order kinetics [50–52], the results of our study was different. S.K. Leong has reported that the second order kinetics is the predominant in the photo-Fenton systems [53].

TOC removal by UV/Fe/H2O2 process

Figure 7 shows the TOC reduction in the process of photo-Fenton. The results demonstrated that the reduction of TOC is significantly lower than the COD reduction. Similar results are reported in some literatures [54, 55]. Originally, the operation parameters are based on COD removal. In order to optimize the effective parameters, removal of TOC was performed to confirm the results of the removal of COD. The results showed that the removal efficiency of total organic carbon was 68% during 120 min.

Fig. 7.

TOC changes versus effluent of petroleum contaminated soil washing removal rate in the photo-Fenton process. (UV = 400 W, (H2O2)opt = 1 g/L, (FeSO4.7H2O)opt = 0.1 g/L, pH = 3)

Conclusion

In the present study, the performance of Photo- Fenton process (Fe2+/H2O2/UV) as an AOP on degradation of organic compounds in the effluent of petroleum contaminated soil washing process have been investigated. The obtained optimum conditions for maximize COD and TOC removal (86.3% and 68% respectively) consist 0.1 g/L Fe2+, 1 g/L H2O2, pH 3 and reaction time of 120 min. In comparison, the UV photolysis and the Fenton reaction removed only 18.14% and 55.7% of COD, respectively. These results demonstrate the prominence of the combined usage of H2O2, Fe2+ ions and UV radiation in the photo-Fenton process for the degradation of the petroleum hydrocarbons in the aqueous solutions. According to the results the COD oxidation through the Fenton and photo-Fenton systems has a second-order kinetics and the reaction rate constants were 7 × 10−6 and 3 × 10−6 l/mg min−1 respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank associate professor Mohammad Hossein Rasoulifard from Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Sciences, University of Zanjan for their research advice.

Abbreviations

- AOPs

Advanced oxidation processes

- COD

Chemical oxygen demand

- TOC

Total organic carbon

- GC

Gas chromatography

Funding

The present work was part a Master thesis entitled “performance evaluation of photo-Fenton process in the treatment of soil washing wastewater”, which was financially supported by Zanjan University of Medical Sciences.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm no conflicts of interest associated with this publication.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed to publish this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No human samples were used in this study and all experiments were chemically and in laboratory scale.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tsai T, Kao C. Treatment of petroleum-hydrocarbon contaminated soils using hydrogen peroxide oxidation catalyzed by waste basic oxygen furnace slag. J Hazard Mater. 2009;170(1):466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.04.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu W. Remediation of contaminated soils by surfactant-aided soil washing. Practice Periodical of Hazardous, Toxic, and Radioactive Waste Management. 2003;7(1):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan FI, Husain T, Hejazi R. An overview and analysis of site remediation technologies. J Environ Manag. 2004;71(2):95–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu D-Y, Kang N, Bae W, Banks MK. Characteristics in oxidative degradation by ozone for saturated hydrocarbons in soil contaminated with diesel fuel. Chemosphere. 2007;66(5):799–807. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng D, Lorenzen L, Aldrich C, Mare P. Ex situ diesel contaminated soil washing with mechanical methods. Miner Eng. 2001;14(9):1093–1100. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahn C, Kim Y, Woo S, Park J. Soil washing using various nonionic surfactants and their recovery by selective adsorption with activated carbon. J Hazard Mater. 2008;154(1–3):153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farzadkia M, Dehghani M, Moafian M. The effects of Fenton process on the removal of petroleum hydrocarbons from oily sludge in shiraz oil refinery, Iran. J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2014;12(1):31. doi: 10.1186/2052-336X-12-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng Y, Englehardt JD. Treatment of landfill leachate by the Fenton process. Water Res. 2006;40(20):3683–3694. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tony MA, Zhao Y, Fu J, Tayeb AM. Conditioning of aluminium-based water treatment sludge with Fenton’s reagent: effectiveness and optimising study to improve dewaterability. Chemosphere. 2008;72(4):673–677. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coelho A, Castro AV, Dezotti M, Sant’Anna G., Jr Treatment of petroleum refinery sourwater by advanced oxidation processes. J Hazard Mater. 2006;137(1):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreozzi R, Caprio V, Insola A, Marotta R, Sanchirico R. Advanced oxidation processes for the treatment of mineral oil-contaminated wastewaters. Water Res. 2000;34(2):620–628. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gernjak W, Maldonado M, Malato S, Caceres J, Krutzler T, Glaser A, et al. Pilot-plant treatment of olive mill wastewater (OMW) by solar TiO2 photocatalysis and solar photo-Fenton. Sol Energy. 2004;77(5):567–572. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li G, Zhao X, Ray MB. Advanced oxidation of orange II using TiO2 supported on porous adsorbents: the role of pH, H2O2 and O3. Sep Purif Technol. 2007;55(1):91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galvão SAO, Mota AL, Silva DN, Moraes JEF, Nascimento CA, Chiavone-Filho O. Application of the photo-Fenton process to the treatment of wastewaters contaminated with diesel. Sci Total Environ. 2006;367(1):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pignatello JJ, Oliveros E, MacKay A. Advanced oxidation processes for organic contaminant destruction based on the Fenton reaction and related chemistry. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2006;36(1):1–84. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fenton HJH. LXXIII.—oxidation of tartaric acid in presence of iron. Journal of the chemical society. Transactions. 1894;65:899–910. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miró P, Arques A, Amat A, Marin M, Miranda M. A mechanistic study on the oxidative photodegradation of 2, 6-dichlorodiphenylamine-derived drugs: photo-Fenton versus photocatalysis with a triphenylpyrylium salt. Appl Catal B Environ. 2013;140:412–418. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang J, Bank JF. Scholes CP. Subsecond time-resolved spin trapping followed by stopped-flow EPR of Fenton reaction products. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115(11):4742–4746. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faust BC, Hoigné J. Photolysis of Fe (III)-hydroxy complexes as sources of OH radicals in clouds, fog and rain. Atmos Environ Part A. 1990;24(1):79–89. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molkenthin M, Olmez-Hanci T, Jekel MR, Arslan-Alaton I. Photo-Fenton-like treatment of BPA: effect of UV light source and water matrix on toxicity and transformation products. Water Res. 2013;47(14):5052–5064. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun J-H, Sun S-P, Fan M-H, Guo H-Q, Lee Y-F, Sun R-X. Oxidative decomposition of p-nitroaniline in water by solar photo-Fenton advanced oxidation process. J Hazard Mater. 2008;153(1–2):187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiburtius ERL, Peralta-Zamora P, Emmel A, Leal ES. Degradation of BTXs by advanced oxidative processes. Química Nova. 2005;28(1):61–64. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Jin W, Zhao Y, Zhang G, Zhang W. Enhanced catalytic degradation of methylene blue by α-Fe2O3/graphene oxide via heterogeneous photo-Fenton reactions. Appl Catal B Environ. 2017;206:642–652. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lima MJ, Silva CG, Silva AM, Lopes JC, Dias MM, Faria JL. Homogeneous and heterogeneous photo-Fenton degradation of antibiotics using an innovative static mixer photoreactor. Chem Eng J. 2017;310:342–351. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boruah PK, Sharma B, Karbhal I, Shelke MV, Das MR. Ammonia-modified graphene sheets decorated with magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles for the photocatalytic and photo-Fenton degradation of phenolic compounds under sunlight irradiation. J Hazard Mater. 2017;325:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernández-Francisco E, Peral J, Blanco-Jerez L. Removal of phenolic compounds from oil refinery wastewater by electrocoagulation and Fenton/photo-Fenton processes. Journal of Water Process Engineering. 2017;19:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebrahiem EE, Al-Maghrabi MN, Mobarki AR. Removal of organic pollutants from industrial wastewater by applying photo-Fenton oxidation technology. Arab J Chem. 2017;10:S1674–S16S9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dehghani M, Shahsavani E, Farzadkia M, Samaei MR. Optimizing photo-Fenton like process for the removal of diesel fuel from the aqueous phase. J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2014;12(1):87. doi: 10.1186/2052-336X-12-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tony MA, Purcell PJ, Zhao Y. Oil refinery wastewater treatment using physicochemical, Fenton and photo-Fenton oxidation processes. J Environ Sci Health A. 2012;47(3):435–440. doi: 10.1080/10934529.2012.646136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tiburtius ERL, Peralta-Zamora P, Emmel A. Treatment of gasoline-contaminated waters by advanced oxidation processes. J Hazard Mater. 2005;126(1–3):86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tony MA, Zhao Y, Purcell PJ, El-Sherbiny M. Evaluating the photo-catalytic application of Fenton's reagent augmented with TiO2 and ZnO for the mineralization of an oil-water emulsion. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part A. 2009;44(5):488–493. doi: 10.1080/10934520902719894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kositzi M, Poulios I, Malato S, Caceres J, Campos A. Solar photocatalytic treatment of synthetic municipal wastewater. Water Res. 2004;38(5):1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2003.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tony MA, Purcell PJ, Zhao Y, Tayeb AM, El-Sherbiny M. Photo-catalytic degradation of an oil-water emulsion using the photo-Fenton treatment process: effects and statistical optimization. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part A. 2009;44(2):179–187. doi: 10.1080/10934520802539830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramirez JH, Maldonado-Hódar FJ, Pérez-Cadenas AF, Moreno-Castilla C, Costa CA, Madeira LM. Azo-dye Orange II degradation by heterogeneous Fenton-like reaction using carbon-Fe catalysts. Appl Catal B Environ. 2007;75(3–4):312–323. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Babuponnusami A, Muthukumar K. A review on Fenton and improvements to the Fenton process for wastewater treatment. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. 2014;2(1):557–572. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubio-Clemente A, Torres-Palma RA, Penuela GA. Removal of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in aqueous environment by chemical treatments: a review. Sci Total Environ. 2014;478:201–225. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.12.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chu W, Wong C. The photocatalytic degradation of dicamba in TiO2 suspensions with the help of hydrogen peroxide by different near UV irradiations. Water Res. 2004;38(4):1037–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2003.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.da Rocha ORS, Dantas RF, Bezerra Duarte MM, Lima Duarte MM, da Silva VL. Solar photo-Fenton treatment of petroleum extraction wastewater. Desalin Water Treat. 2013;51(28–30):5785–5791. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dionysiou DD, Suidan MT, Bekou E, Baudin I. Laîné J-M. effect of ionic strength and hydrogen peroxide on the photocatalytic degradation of 4-chlorobenzoic acid in water. Appl Catal B Environ. 2000;26(3):153–171. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Batista APS, Nogueira RFP. Parameters affecting sulfonamide photo-Fenton degradation–iron complexation and substituent group. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem. 2012;232:8–13. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lucas MS, Peres JA. Removal of COD from olive mill wastewater by Fenton's reagent: kinetic study. J Hazard Mater. 2009;168(2–3):1253–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lipczynska-Kochany E. Degradation of nitrobenzene and nitrophenols by means of advanced oxidation processes in a homogeneous phase: photolysis in the presence of hydrogen peroxide versus the Fenton reaction. Chemosphere. 1992;24(9):1369–1380. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moraes JEF, Quina FH, Nascimento CAO, Silva DN, Chiavone-Filho O. Treatment of saline wastewater contaminated with hydrocarbons by the photo-Fenton process. Environmental science & technology. 2004;38(4):1183–1187. doi: 10.1021/es034217f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villa RD, Trovó AG, Nogueira RFP. Environmental implications of soil remediation using the Fenton process. Chemosphere. 2008;71(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Villa RD, Trovó AG, Nogueira RFP. Soil remediation using a coupled process: soil washing with surfactant followed by photo-Fenton oxidation. J Hazard Mater. 2010;174(1–3):770–775. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.09.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang Y-H, Huang Y-J, Tsai H-C, Chen H-T. Degradation of phenol using low concentration of ferric ions by the photo-Fenton process. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2010;41(6):699–704. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun S-P, Li C-J, Sun J-H, Shi S-H, Fan M-H, Zhou Q. Decolorization of an azo dye Orange G in aqueous solution by Fenton oxidation process: effect of system parameters and kinetic study. J Hazard Mater. 2009;161(2–3):1052–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daud N, Akpan U, Hameed B. Decolorization of Sunzol black DN conc. In aqueous solution by Fenton oxidation process: effect of system parameters and kinetic study. Desalin Water Treat. 2012;37(1–3):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karthikeyan S, Gupta V, Boopathy R, Titus A, Sekaran G. A new approach for the degradation of high concentration of aromatic amine by heterocatalytic Fenton oxidation: kinetic and spectroscopic studies. J Mol Liq. 2012;173:153–163. [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Souza DR, Duarte ETFM, de Souza GG, Velani V, da Hora Machado AE, Sattler C, et al. Study of kinetic parameters related to the degradation of an industrial effluent using Fenton-like reactions. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem. 2006;179(3):269–275. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fan X, Hao H, Shen X, Chen F, Zhang J. Removal and degradation pathway study of sulfasalazine with Fenton-like reaction. J Hazard Mater. 2011;190(1–3):493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guedes AM, Madeira LM, Boaventura RA, Costa CA. Fenton oxidation of cork cooking wastewater—overall kinetic analysis. Water Res. 2003;37(13):3061–3069. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(03)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leong SK, Bashah NAA. Kinetic study on COD removal of palm oil refinery effluent by UV-Fenton. APCBEE Procedia. 2012;3:6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bertelli M, Selli E. Kinetic analysis on the combined use of photocatalysis, H2O2 photolysis, and sonolysis in the degradation of methyl tert-butyl ether. Appl Catal B Environ. 2004;52(3):205–212. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ghanbari F, Moradi M, Manshouri M. Textile wastewater decolorization by zero valent iron activated peroxymonosulfate: compared with zero valent copper. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering. 2014;2(3):1846–1851. [Google Scholar]