Abstract

Cadmium (Cd) is a toxic heavy metal that induces irregularity in numerous lipid metabolic pathways. Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a model to study lipid metabolism, has been used to establish the molecular basis of cellular responses to Cd toxicity in relation to essential minerals and lipid homeostasis. Multiple pathways sense these environmental stresses and trigger the mineral imbalances specifically calcium (Ca) and zinc (Zn). This review is aimed to elucidate the role of Cd toxicity in yeast, in three different perspectives: (1) elucidate stress response and its adaptation to Cd, (2) understand the physiological role of a macromolecule such as lipids, and (3) study the stress rescue mechanism. Here, we explored the impact of Cd interference on the essential minerals such as Zn and Ca and their influence on endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipid metabolism. Cd toxicity contributes to lipid droplet synthesis by activating OLE1 that is essential to alleviate lipotoxicity. In this review, we expanded our current findings about the effect of Cd on lipid metabolism of budding yeast.

Keywords: Cadmium, Calcium, Zinc, Lipid, OLE1, Lipid droplets, Yeast

Introduction

Cadmium (Cd) is a toxic heavy metal, hazardous for both humans and animals and has been declared by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a carcinogen (IARC 1993). Cd possesses a biological half-life of 30 years in humans, because of its high retention and low excretion rate. Exposure to Cd occurs via plant-derived foods, seafood, tobacco smoking, and inhalation of industrially emitted air (Järup and Åkesson 2009). Chronic exposure to Cd causes damage in the cardiovascular, immune, and reproductive systems (Nordberg 2009), and epidemiological data indicate an increase in the risk of prostate, genitourinary, breast, lung, and colon cancers and hepatocellular carcinoma (Luevano and Damodaran 2014). Recently, Cd was shown as a possible etiological factor for human neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease (Chin-Chan et al. 2015).

Cd induces reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and thereby results in oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and altered homeostasis of certain essential metals (Nair et al. 2013; Choong et al. 2014; Pereira et al. 2014; Al Kaddissi et al. 2014). The generated ROS targets biomolecules, such as DNA, lipids, and proteins, and eventually induces cell death. Cd is involved in the inhibition of DNA repair enzymes, deregulation of cell proliferation, interference with the apoptosis, disruption of cell adhesion, signal transduction cascades, autophagy, and tumour suppressor functions (Beyersmann and Hartwig 2008; Wysocki and Tamás 2010; Muthukumar et al. 2011; Xie et al. 2016). Interestingly, the mechanisms involved in metal toxicity detoxification are conserved across all eukaryotic organisms (Huh et al. 2003; Bleackley and MacGillivray 2011).

Cell biology has greatly benefited with yeast as a model system whose genetics and metabolism are well studied. Yeast, due to its protein homology with higher eukaryotes, has provided numerous insights into the genetics and biochemistry of several disorders including lipid-related diseases, signalling pathways, and regulatory networks (Buschini et al. 2003; Koch et al. 2014). Yeast has been extensively exploited using, gene disruptions, protein localization, protein-protein interactions, and functional analysis by genetic interactions, to understand diverse cellular processes (Tong et al. 2004; Henry et al. 2012). In the past few decades, Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been used as a tool to study the mechanism of biological response against numerous toxic metals, including Cd (Jin et al. 2008; Hosiner et al. 2014). The genome-wide screening of gene and protein expression underlying Cd toxicity analysed by microarray (Vido et al. 2001), and proteomics arrays/assays (Brzóska and Moniuszko-Jakoniuk 1998; Fauchon et al. 2002), respectively, revealed Cd interference in several vital metabolisms.

Cd is a toxic metal that interrupts numerous signalling pathways resulting in toxicity. Although, increasing consideration is given to interactions between toxic metals and bio-elements such as zinc (Zn), copper, iron, selenium, and calcium (Ca) (Gardarin et al. 2010), the molecular insight into Cd-induced biological effects is uncertain (Jomova and Valko 2011). Cd has a high affinity for sulphhydryl, carboxyl, and phosphate groups and thereby inhibits enzymes and disrupts various metabolic processes, including lipid metabolism (Rogalska et al. 2009). Understanding the lipid homeostasis is critical because, the imbalance in lipid metabolism leads to cardiovascular diseases, fatty liver, and obesity (Wenk 2005). Despite the importance of lipid metabolism, only limited studies have reported the involvement of lipid pathways in Cd-associated resistance mechanisms.

Lipids rank among the main components present in cell membranes, and Cd exposure alters the lipid levels (Muthukumar et al. 2011; Rajakumar et al. 2016a; Rajakumar et al. 2016b). Recent studies explored the molecular effects of Cd on lipid pathways such as lipid transport and energy metabolism in crabs Sinopotamonhenanense (Liu et al. 2013). The role of Cd in oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, autophagy mechanisms, lipid metabolism, essential metal interference, and numerous signalling pathways has been assessed with various concentrations of Cd in yeast model systems (Table 1). This review focuses on the effect of Cd on lipids and aims to provide the possible mechanism behind stress-associated lipid accumulation using S. cerevisiae as a model organism.

Table 1.

Effects of various concentrations of Cd on the different metabolic pathways in yeast cell

| S. No. | Metal | Concentration | Method | Metabolism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Cadmium sulphate (CdSO4) | 50 μM | Spot test | Phospholipids, lipid droplets, zinc and calcium passage, autophagy, Hog1 pathway, functional profiling screens |

Muthukumar et al. 2011 Muthukumar and Nachiappan 2013 Rajakumar et al. 2016a Rajakumar et al., 2016b Fang et al., 2016 Guo et al. 2016 Rajakumar and Nachiappan 2017 Chang et al. 2018 |

| 3.5 μM | Barcode sequencing (Bar-seq) | Functional profiling screens | Guo et al. 2016 | ||

| 2. | Cadmium chloride (CdCl2) | 10 μM | Spot test | Transcription profiling on target pathways | Hosiner et al. 2014 |

| 100 and 150 μM | Spot test | CWI MAP kinase pathway | Xiong et al. 2015 |

Cadmium uptake and transports in yeast

All living organisms require processes such as detoxification and homeostatic acquisition of metal ions. Cd is one such metal when in excess is detrimental to cells. Since dead cells are not capable of removing cadmium from the medium, the influx of Cd into yeast cells is dependent on active metabolism. Previous reports have suggested that bivalent cation transporters could play a role in Cd influx (Table 2) into the cells (Gomes et al. 2002), among which the zinc transport system is likely to be the most potent candidate. Studies have shown that the high-affinity zinc transporter, Zrt1, is responsible for Cd uptake (Gitan et al. 1998 and Rajakumar et al. 2016b). Additionally, the level of the Cd–GSH complex controls the transport of Cd though the activation of Yap1 and Ycf1 facilitates Cd uptake through Zrt1 (Gomes et al. 2002). Although metal efflux systems have begun to be characterized, metallothionine (MT) and GSH-mediated sequestration aid in neutralizing toxic metals, in eukaryotes (Gomes et al. 2002). Phytochelatin, a GSH polymer synthesized in plants and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, detoxifies heavy metals (Cobbett and Goldsbrough 2002). A few other examples of transporters include Ycf1, a vacuolar membrane ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter and P1B-type heavy metal-transporting ATPase (PCA1) (Eraso et al., 2004; Gomes et al., 2002; Adle et al. 2006). Glutathione and/or other cytosolic Cd carriers interact with the PCA1 metal-binding domain to transfer Cd (Eraso et al., 1997 and Gomes et al., 2002; Cobbett and Goldsbrough 2002; Adle et al. 2007). Similarly, organisms have evolved certain defence mechanisms to negotiate the toxic effects of heavy metals. The P1B-type ATPase family and some essential metal transporters extrude toxic metal ions such as Fe, Cu, Zn, Mn, Ca, and Cd from the cell (Adle et al. 2007 and Wysocki and Tamás 2010).

Table 2.

Intracellular or uptake of Cd on yeast cells

| Yeast strains | Concentration of Cd | Incubation (h) | Intracellular/uptake Cd levels | Methods | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg/g | nmol/OD | |||||

| BY4741 | 50 μM CdSO4 | 12 | 0.76 ± 0.92 | ICP-OES | Muthukumar et al. 2011 | |

| BY4741 | 50 μM CdSO4 | 12 | 1.34 ± 1.52 | ICP-OES | Rajakumar et al. 2016a | |

| 3031a | 50 μM CdSO4 | 12 | 0.64 ± 0.89 | ICP-OES | Rajakumar et al. 2016b | |

| BY4741 | 50 μM CdSO4 | 48 | 4.48 ± 3.7 | ICP-OES | Abbà et al. 2011 | |

| BY4741 | 25 μM CdCl2 | 06 | 3.64 ± 0.02 | ICP-AES | Mazzola et al. 2015 | |

| BY4742 | 25 μM CdCl2 | 06 | 3.20 ± 0.00 | ICP-AES | Caetano et al. 2015 | |

Impact of cadmium interference on zinc transporters

The trace element Zn plays a vital role in growth, development, and cell functioning (Singh et al. 2016) and serves as a cofactor for various essential proteins such as lipid metabolism proteins, alcohol dehydrogenase, Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase, chaperones, DNA or RNA polymerases, and ribosomal proteins (Regalla and Lyons 2005). Cd exhibits similar physical and chemical properties with Zn. Exposure to and interference by Cd leads to Zn deficiency and subsequently serious health concerns (Schrey et al. 2000). The displacement of Zn with Cd occurs in some biological processes decreasing intracellular Zn levels and affecting Zn homeostasis (Rajakumar et al. 2016b). Disturbances in Zn balance alter the function and metabolism of lipids.

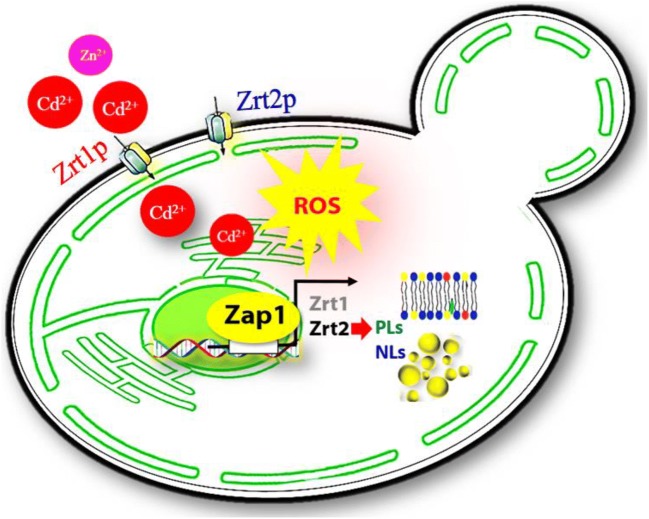

Since the accumulation or depletion of Zn is toxic, the cytosolic Zn level is stringently maintained by influx and efflux mechanisms. The Zn transcription factor ZAP1 activates the Zn transporters; Zrt1p (high affinity) and Zrt2p (low affinity) present in the plasma membrane (Zhao and Eide 1996a; Zhao and Eide 1996b; Ehrensberger and Bird 2011). Further, the vacuolar Zn transporter Zrt3p and the plasma membrane transporter Fet4p also assist in maintaining the cytosolic Zn levels (Eide 2009). Zrt1p is important for Cd uptake in Zn-limited cells, and Zrt1p inactivation averts Cd overload (Gitan et al. 2003). Cd accumulation and Cd-mediated toxicity decrease Zn influx (Brzóska and Moniuszko-Jakoniuk 2001). Zn homeostasis is closely linked to lipid metabolism, and Zn deficiency activates Zap1 and causes lipid accumulation (Han et al. 2001; Singh et al. 2016). Cd exposure to wild-type (WT) yeast cells significantly upregulated Zn transporters, ZRT1 and ZRT2, but reduced the intracellular Zn levels. Intriguingly, the ZRT1 mutant strains were resistant to Cd and prevented Cd overload compared to the WT cells and ZRT2 mutant strains (Gitan et al. 2003; Rajakumar et al. 2016b). During Zn depletion, phospholipid metabolism is regulated by ZAP1 (Zhao and Eide 1996b; Koch et al. 2014), and membrane phospholipids, especially phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and phosphatidylinositol (PI) are altered in S. cerevisiae (Carman and Han 2007; Singh et al. 2016). Cd exposure significantly increased the phospholipids in yeast cells (Muthukumar et al. 2011; Rajakumar et al. 2016a), but decreased phosphatidylcholine (PC), PE, and phosphatidylserine levels in ZRT1 mutant cells.

Concerning Zn homeostasis and phospholipids, the role of Zap1p has been well explored; nevertheless, minimal information is available on the regulation of triacyl glycerol (TAG) metabolism in yeast. Phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase 1 (PAH1) and dipeptidyl peptidase 1 (DPP1) are highly affected under Zn-limiting conditions and regulated at the transcription level by Zap1p (Carman and Han 2007; Koch et al. 2014). The upregulation of the lipid precursor phosphatidic acid (PA) contributes to TAG formation through PAH1. During Zn deficiency, PAH1 is highly activated through ZAP1 (Soto-Cardalda et al. 2012). Zap1 regulates mitochondrial fatty acid (FA) and TAG. The deletion of FA gene ETR1 causes the accumulation of TAG, and the expression of ETR1 in zap1∆ strain restores the TAG level. These results showed that the conceded mitochondrial FA biosynthesis caused a reduction in lipoic acid and loss of mitochondrial function in zap1∆ cells. Additionally, the deletion of ZAP1 increased TAG and resulted in lipid droplet (LD) accumulation in S. cerevisiae. Cd exposure in WT and zrt2∆ cells increased TAG and sterol esters (SE) levels and resulted in LDs with a larger size and increased number (Rajakumar et al. 2016b). Furthermore, Zn-limiting conditions led to ROS accumulation in budding yeast (Wu et al. 2009). ROS generation in WT and zrt2∆ cells increased on Cd exposure; however, zrt1∆ behaved differently. An apparent decrease in intracellular levels of Cd and TAG was seen in zrt1∆ cells. Cd exposure reduced the Zn levels and served as a risk factor for alteration in lipid homeostasis and ROS levels in S. cerevisiae (Rajakumar et al. 2016a). Thus, the plasma membrane transporter Zrt1 appears to be dependent on Zap1 and protects the cells against Cd toxicity, lipid accumulation, and oxidative damage in S. cerevisiae (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A hypothetical pathway elucidating the uptake of Cd via Zn transporter systems Zrt1p and Zrt2p. Zrt1 aids in the uptake the Cd compared to Zrt2 and subsequently ROS and lipid accumulation in S. cerevisiae

Cadmium-induced apoptosis and autophagy in yeast

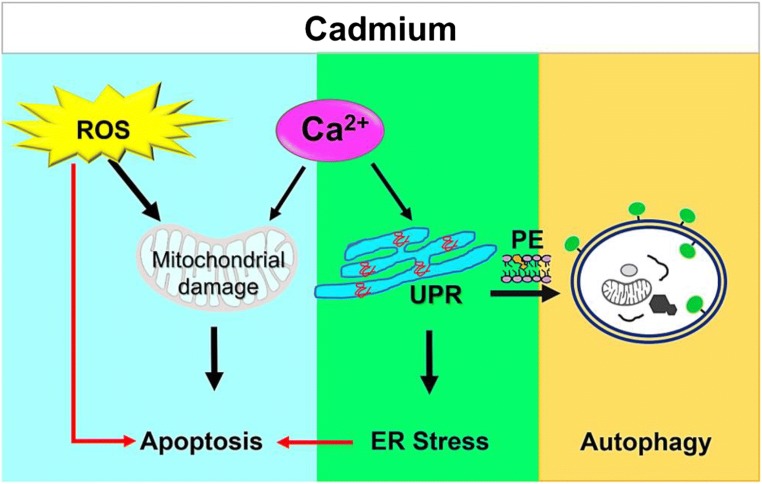

S. cerevisiae is used as a model organism for understanding the process of cell killing and its mechanisms (Carmona-Gutierrez et al. 2010). Both exogenous and intrinsic stresses can cause cell death in yeast (Sharon et al. 2009). Usually toxic metal-induced yeast cell killing mechanism is associated with increased intracellular ROS generation, oxidative stress, and loss in Ca2+ homeostasis (Gomes et al. 2008; Wu et al. 2013).

Cd-induced apoptosis is a result of cellular GSH: GSSG imbalance and heightened levels of intracellular ROS, particularly in yca1 and gsh1 mutants (Nargund et al. 2008). In response to Cd toxicity, the alterations in cellular sulphhydryls may be the major determining factor for cell death (Kim et al. 2003). Transcription factors such as Yap1p, Skn7p, Msn2p, and Msn4p collectively coordinate appropriate responses to different oxidative stressors, by either repressing or upregulating the transcription of specific genes (Lee et al. 1999; Gasch et al. 2000; Temple et al. 2005) and many of these transcription factors are linked to the antioxidant defence mechanism. Yap1p and Skn7p mainly regulate the yeast cell response to Cd toxicity by upregulating transcription of yeast Cd factor YCF1 (Wemmie et al. 1994). ROS induces mitochondrial dysfunction, release of cytochrome c to the cytoplasm, activation of caspase-9, and hydrolysis of specific cellular proteins. Although elevated ROS levels may play a chief role in inducing apoptosis, additional factors such as Ca2+ homeostasis are present (Ruta et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2014); however, the precise pathway remains uncertain.

Besides apoptosis, autophagy plays a pivotal role in Cd-mediated toxicity. Autophagy maintains cellular homeostasis via the removal of damaged organelles and toxic macromolecules and thus prevents the organism from damage and disease (Zhang et al. 2007; Thevenod, 2009; Kroemer et al. 2010; Thorburn 2018). Cd induces ER stress and is associated with degradation of misfolded or damaged proteins. In yeast, Cd toxicity triggers several vacuolar and autophagic responsive genes such as PRB1, LAP4, and PEP4. Another gene, SEC17, which encodes for a membrane protein required for vesicular transport and autophagy is induced in when the cells are exposed to Cd (Hosiner et al. 2014). Additionally, phospholipids, particularly PE, play a major role in autophagosome formation and are reliable markers for autophagy (Nakatogawa et al. 2007). Phospholipids are involved in lipidation of Atg8p. PE depletion causes in the membrane extension around the autophagosomes to lose its integrity (Nebauer et al. 2007). PE accumulation in Cd toxicity was validated by understating the involvement of phosphatidylethanolamine decarboxylase (PSD2) (Muthukumar and Nachiappan, 2013). Under Cd toxicity, PE obtained from PSD2 alone is used for Atg8 lipid conjugation (Atg8–PE). These results suggest that cells were able to tolerate the Cd stress through organelle-specific PE synthesis, and the importance of PE in the assembly of autophagosomes is evident (Muthukumar and Nachiappan, 2013). Thus, xenobiotic metals, like cadmium, interfere with protein folding and degradative mechanisms in living cells, with autophagy and apoptosis targets (Fig. 2). A better understanding of these mechanisms may provide important insights into the contribution of metals and metalloids to protein-misfolding diseases.

Fig. 2.

The Cd-induced apoptosis and autophagy pathways in S. cerevisiae

Calcium impairment causes lipid aberrancy

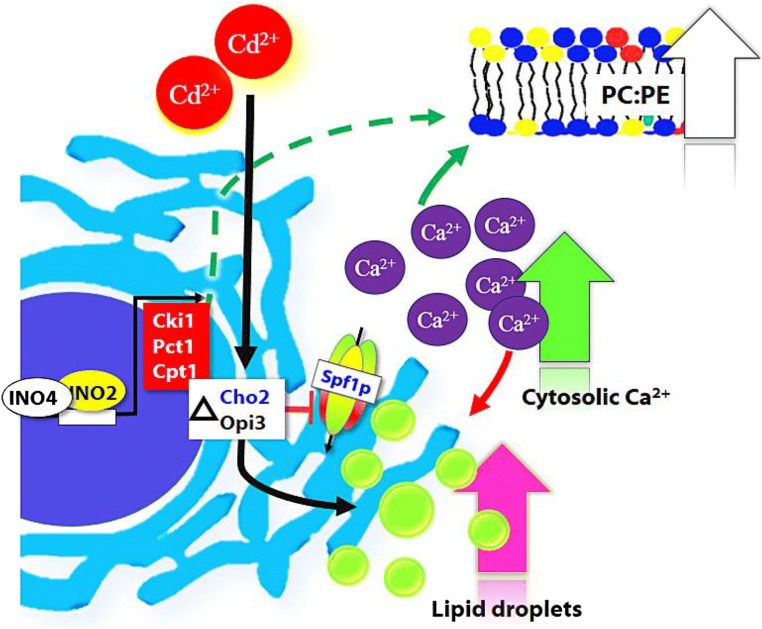

The maintenance of Ca levels in the ER is essential for protein production (Schröder and Kaufman 2005). The ER provides a platform for the cross-talk of many cellular signalling pathways and metabolic regulatory events through Ca fluxes and metabolism (Verkhratsky 2005). Cd interacts with Ca transport in intracellular stores, such as interference in hepatic Ca sequestration in the microsomes (Zhang et al. 1990), or inhibition of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase (SERCA) (Hechtenberg and Beyersmann 1991). The Ca-dependent proteins in the ER have an important role in the maintenance of cellular integrity (Groenendyk et al. 2010). The function of Ca transporters and channels is also modulated by membrane lipid composition, protein-protein interaction, and a range of post-translational modifications (Fu et al. 2011). An alternative theory of ER stress postulates a key role for the downregulation of SERCA2 as a result of ER luminal Ca depletion (Fu et al. 2012). The enhanced ratio of PC/PE in the ER impairs SERCA2 and stimulates ER stress (Fu et al. 2011) indicating a link between lipotoxicity and Ca imbalance. The absence of SERCA in S. cerevisiae led to the discovery of another P-type ATPase, Cod1/Spf1p, that controls the Hmg2p degradation through Ca in the ER (Cronin et al. 2002). These studies indicate a close relationship between the Ca and lipid homeostasis in the ER. The alteration of intracellular Ca and unfolded protein response (UPR) activation are reported in several models of metabolic disease and lipid disequilibrium (Ozcan et al. 2004; Fu et al. 2011; Abhishek et al. 2017). Lipid remodelling occurs as an adaptive stress response and acclimatization during ER stress, but the mechanistic link between lipid aberrancy and Ca imbalance is yet to be elucidated.

The surge in intracellular Ca leads to alteration of phospholipids, especially PC levels. The silencing of phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase accelerated the SERCA activity and reduced ER stress (Jacobs et al. 2010). On exposure of WT yeast cells to Cd, the Kennedy pathway (CKI1, EKI1, and CPT1) and the methylation pathway (CHO2 and OPI3) genes were upregulated for PC synthesis (Rajakumar et al. 2016a). In yeast, the Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets (BioGRIDs) showed a negative genetic interaction of yeast phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase homologue OPI3 with SPF1 and PMR1 (Schuldiner et al. 2005; Jonikas et al. 2009; Surma et al. 2013).

The spf1Δ activated the Ca-responsive genes and significantly increased intracellular Ca levels (Cronin et al. 2002). Some experimental evidence suggests the negative genetic interaction between Opi3 with Spf1 with a high confidence score. Remarkably, SPF1 and PMR1 are downregulated in opi3Δ cells (Rajakumar et al. 2016a). The defects of Pmr1 and Spf1 have implications in protein glycosylation, influence ER stress, and stimulate LD formation in S. cerevisiae (Fei et al. 2009; Cohen et al. 2013). Increase in TAG and LD levels were observed in cho2Δ and opi3Δ cells during Cd exposure (Rajakumar et al. 2016a). In yeast, Cd toxicity modified Ca homeostasis and PC content (lipid alteration) and had an impact on Ca-ATPase in ER (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cd downregulates the SPF1 (ER Ca2+ATPase) and thereby alters phospholipid methylation disrupting lipid homeostasis in S. cerevisiae

The defect in lipid metabolism activated the UPR, suggestive of a compensatory role (Thibault et al. 2012; Surma et al. 2013). Alteration in the ratio of membrane PC/PE resulted in ER stress and Ca imbalance in mice hepatocytes (Fu et al. 2011). The elevation in Kar2p (ER chaperone) expression in opi3Δ cells with or without Cd treatment can be attributed to Ca imbalance or SPF1 downregulation in S. cerevisiae (Rajakumar et al. 2016a). SPF1 is part of the UPR program and regulates Hmg2p degradation in the ER. Mutants lacking SPF1 exhibit defects in membrane protein orientation (Krumpe et al. 2012). The abundance of intracellular Ca-induced lipid aberrancy has an impact on membrane proliferation in S. cerevisiae. Chemical stress induces upregulation of genes involved in phospholipid biosynthesis, cell membrane, and cell wall organization (Murata et al. 2003). Together, these findings demonstrated a relationship between Ca and lipid homeostasis during Cd toxicity.

Mitochondrial dysfunctions are accompanied by PC impairment during Cd stress (Rajakumar et al. (2016a). The physiological and functional interaction of ER with mitochondria accounts for Ca transport and lipid synthesis in the cell (Mitsuhashi et al. 2011; Malhotra and Kaufman 2011). Cd treatment resulted in the fragmentation of mitochondrial structure in opi3Δ and WT strains. PC is essential for Cd tolerance, intracellular membrane maintenance, and preserving mitochondrial morphology (Rajakumar et al. 2016a). The reciprocal relationship with the phospholipids and Ca provides another facet of a stress-regulated mechanism in S. cerevisiae.

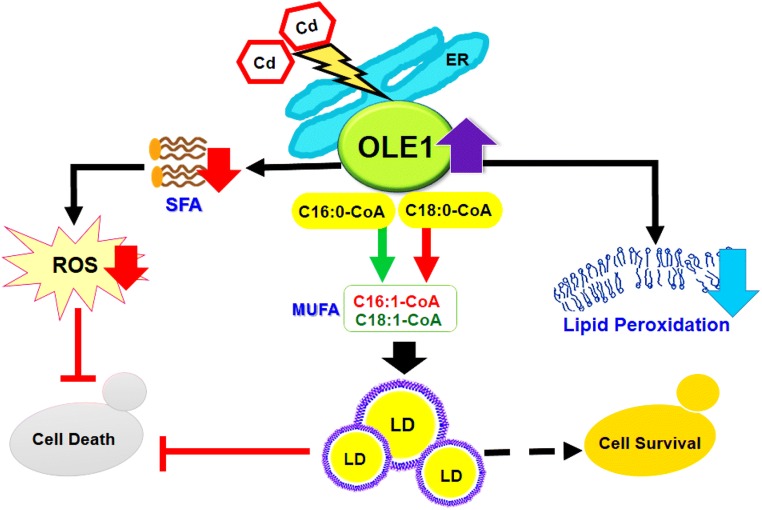

Effect of cadmium on fatty acid desaturase—OLE1

Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) is the key enzyme responsible for the biosynthesis of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) in rats and human (Kim and Ntambi 1999). In S. cerevisiae, OLE1 encodes for the sole delta-9 FA desaturase, with a sequence like that of human SCD1. Ole1 is an ER membrane protein essential for the synthesis of MUFA. The primary products of Ole1p are palmitoleic (16:1) and oleic (18:1) FAs, formed from palmitoyl (16:0) and stearoyl (18:0) CoA, respectively (Martin et al. 2007). This enzyme (Ole1p) mainly contributes towards cell viability and membrane fluidity by regulating the equilibrium of saturated fatty acid (SFA)and unsaturated fatty acid (UFA). In S. cerevisiae, Ole1 is the target of ER-bound transcription factors Spt23p and Mga2p. In response to stimuli, both Spt23p and Mga2p are activated by ubiquitin-dependent processing into their soluble forms and then targeted to the nucleus (Chellappa et al. 2001; Aguilar and De Mendoza 2006). At the transcriptional and mRNA levels, OLE1 is highly regulated and responds to some different stimuli, including a carbon source, nutrient FAs, metal ions, and oxygen levels (Aguilar and De Mendoza 2006 and Martin et al. 2007). Additionally, impairment of lipid storage and membrane damage is an important aspect of Cd stress (Pierron et al. 2007; Rahoui et al. 2010). Alterations in the lipid composition can tolerate Cd stress in S. cerevisiae (Muthukumar et al. 2011; Rajakumar et al. 2016a; Rajakumar and Nachiappan 2017). Hence, lipid-associated pathways may be involved in the mechanisms of Cd damage and resistance.

A recent investigation of Cd stress and the adaptive mechanisms of yeast were done by screening a genome-wide essential gene overexpression. OLE1 was associated with high Cd stress (Fang et al. 2016). The WT strains bearing the OLE1 plasmid showed strong Cd resistance as well as more accumulation of intracellular Cd (Fang et al. 2016). On exposure to Cd, OLE1 mRNA levels were significantly increased in the WT (Rajakumar and Nachiappan, 2017), mga2Δ, and spt23Δ strains (Fang et al. 2016). Particularly, the spt23Δ strain showed more tolerance compared to mga2Δ revealing a positive correlation between the OLE1 expression level and Cd resistance. Either with and without OLE1 overexpression, WT yeast cells exposed to Cd stress resulted in a significant increase in MUFA (C16:1 and C18:1) (Fang et al. 2016; Rajakumar and Nachiappan 2017).

The effects of oleic acid on membrane integrity decreased in WT and OLE1 overexpressed strains treated with Cd revealed a relationship between MUFA and Cd stress. Interestingly, Cd induced a high percentage of dead cells, nearly 60% higher than that observed in the mga2Δ control that recovered on supplementation of oleic acid or by overexpression of OLE1 in mga2Δ under Cd stress (Fang et al. 2016).

Cd-induced lipid peroxidation enhanced lipoxygenase activity that is involved in catalysing lipid peroxidation by using membrane lipid components, especially unsaturated FAs, as substrates (Thompson et al. 1998). Compared to saturated FAs, unsaturated FAs contain double bonds that are vulnerable to damage from Cd-induced free radicals, resulting in unsaturated FA peroxidation (Upchurch 2008; Tsaluchidu et al. 2008). OLE1, an oxygen-sensing gene, could be upregulated in response to oxidative stress (Kwast et al. 1999). On Cd treatment, the lipid peroxidation levels were significantly increased in both WT yeast BY4741 (Muthukumar et al. 2011) and mga2Δ strain, and there was a decrease following the overexpression of OLE1 or the addition of oleic acid (Fang et al. 2016). This regulation of OLE1 may help yeast cells to counter lipid peroxidation and membrane damage caused during Cd-induced stress. This finding suggested that regulation of OLE1 in response to Cd stress was associated with oxidative stress and independent of Mga2p and Spt23p (Fang et al. 2016). Delta-9 desaturase present in the rat liver, encoded by SCD1, is a target of Cd and is significantly inhibited by Cd (Kudo et al. 1991). The stress response regulation of OLE1 is an important adaptive response of yeast to counter Cd stress (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

OLE1-facilitated TAG/LD accumulation alleviates the Cd-induced cell death apoptosis in yeast

Lipid droplets alleviate Cd-induced cytotoxicity

Lipotoxicity, the phenomenon of cell death due to lipid imbalance, is a common consequence of the morbidities associated with metabolic syndromes such as obesity, fatty liver, and cardiovascular diseases. The saturated and unsaturated FAs are pro-apoptotic, but cytotoxicity is achieved through different pathways (Garbarino et al. 2009). Cd is associated with a sequence of deteriorating disorders in humans that also cause programmed cell death (Shivapurkar et al. 2003). Programmed cell death is a valuable tool for the elucidation of several key apoptotic regulators in S. cerevisiae (Ligr et al. 1998; Manon 2004). However, the mechanism for Cd-induced lipotoxicity is yet to be defined.

Cd induces oxidative stress that generates ROS and increased lipid accumulation. In oxidative stress, polyunsaturated Fas and other FAs are redistributed from membrane phospholipids to LD and TAGs. Unlike cell membranes, the LD core provides a protective environment that minimizes poly unsaturated FAs peroxidation chain reactions and limits ROS levels (Bailey et al. 2015).

LDs mediate cellular functions other than fat storage and mobilization relevant for energy homeostasis. For example, LDs can participate in protein degradation, histone storage, viral replication, and antibacterial defence (Walther and Farese 2012; Anand et al. 2012). LDs are currently considered to be metabolically active organelles, and during oxidative stress, lipid metabolism is impaired (Cutler et al. 2004; Furukawa et al. 2004). LD biogenesis, by recycling of structural phospholipids into energy-generating substrates, may serve as a survival strategy during stress. The biology of LD has received increasing interest, due to the link between excess lipid storage in certain environmental disturbances of cells.

Avoidance of excess saturated FAs is important in membrane phospholipids and the scavenging of lipotoxicity (Kamphorst et al. 2013). Lipotoxicity resulting from the accumulation of long chain FAs seems to be caused predominantly by saturated FAs (Listenberger et al. 2001). Conversely, oleic acid supplementation that is well-tolerated by the cells leads to triglyceride accumulation and protects the cells against saturated FA-induced lipotoxicity (Listenberger et al. 2003).

In our earlier studies, Cd exposure in S. cerevisiae increased the phospholipids primarily, PC and PE, and induced ER stress (Muthukumar et al. 2011; Muthukumar and Nachiappan 2013; Rajakumar et al. 2016a). There is a functional link between phospholipid metabolism and TAG formation in S. cerevisiae during the various phases of growth. The precursors are channelled towards phospholipid synthesis during membrane formation and towards lipid droplets during storage (Horvath et al. 2011).

Furthermore, FA sensitivity is significantly enhanced in yeast cells that were unable to form LDs (Petschnigg et al. 2009). FAs significantly contributed to the lipid composition. Cd exposure increased the ratio of UFA in WT cells. Interestingly under Cd exposure, the mRNA expression of FA synthesizing genes ACC1 (acetyl-CoA carboxylase1), FAS1 (FA synthase1), and desaturase were upregulated in S. cerevisiae (Rajakumar and Nachiappan 2017).

Upon Cd exposure, there was an insignificant change in the sterol levels while significant alterations were observed in the TAG as well as DAG (Rajakumar and Nachiappan 2017). The TAG is efficiently packed into LDs (Wang 2015). The overload of TAG and SEs contributes to the increased number of LDs in Cd-treated cells. The transcriptional response of genes related to TAG synthesis (LRO1 and DGA1) were upregulated in Cd-treated WT cells (Rajakumar and Nachiappan 2017). FA esterification and storage into LDs protected the cells against free fatty acid (FFA)-induced lipotoxicity. This result is supported by others (Holland et al. 2007).

Defects in LD formation render FFAs toxic (Listenberger et al. 2001). During Cd exposure, a knockout of dga1Δorlro1Δ showed a reduction in the TAG level and accumulated FFA, whereas TAG was accumulated in are1Δ and are2Δ strains. A similar trend in TAG levels was observed in double knockout strains during Cd toxicity (Rajakumar and Nachiappan 2017).

Schizosaccharomyces pombe and S. cerevisiae deficient in a TAG synthesis undergo lipo-apoptosis upon entry into the stationary phase. These cells show promises of apoptotic cell death, including ROS accumulation (Garbarino and Sturley, 2005; Low et al. 2005). The impaired LD synthesis in cells with the dga1Δ or lro1Δ increased ROS generation during Cd exposure. Significant ROS accumulation was observed in single and double mutants of dga1Δ and lro1Δ strains (Rajakumar and Nachiappan 2017). ROS is not only associated with cell death but also plays essential roles in signalling and adaptation to cellular stress (Carmona-Gutierrez et al. 2010).

Excessive accumulation of FFA and its incorporation into phospholipids in various cell membranes caused severe cytotoxicity and lipo-necrosis, whereas neutral lipid storage shielded the cells and alleviated FFA toxicity (Sheibani et al. 2014). Yeast strains that lack all four acyltransferase genes are viable but completely lack neutral lipids and thus present a genetically malleable system to investigate FA-induced cytotoxicity (Garbarino et al. 2009). The TAG mutants (single and double deletion of dga1Δlro1Δ) resulted in both early and late apoptosis during Cd toxicity, whereas the WT and SE mutant cells showed normal physiology (Rajakumar and Nachiappan 2017).

Apoptosis mediated by the overload of FFA and ROS was confirmed in the TAG-deficient cells. This was confirmed with the overexpression of TAG synthesizing genes (DGA1 and LRO1) in LD quadruple mutant strains. When TAG synthesizing genes were overexpressed, TAG levels were increased, FFA levels were ameliorated, and ROS levels decreased (Rajakumar and Nachiappan 2017).Tgl3p, Tgl4p, and Tgl5p are the major TAG lipases of the S. cerevisiae for the degradation of TAG that is stored in LDs (Athenstaedt and Daum 2005). The blockage or defect in TAG hydrolysis rescued the lipotoxicity due to the accumulation of the LDs. Interestingly; Cd toxicity caused the increase in LD number that accumulated TAG in TGL mutants. The TAG accumulation in the double and quintuple knockouts (tgl3Δtgl4Δ, tgl4Δtgl5Δ, and tg13Δtgl4Δtgl5Δare1Δare2Δ) made the cells tolerant to Cd and increased cell growth (Rajakumar and Nachiappan 2017). These data collectively demonstrate that TAG accumulated in the LD buffered the excessive FFA and increased the cell survival during Cd-induced lipotoxicity and cytotoxicity in S. cerevisiae (Fig. 4).

Upregulation of sulphur assimilation pathway and UPR

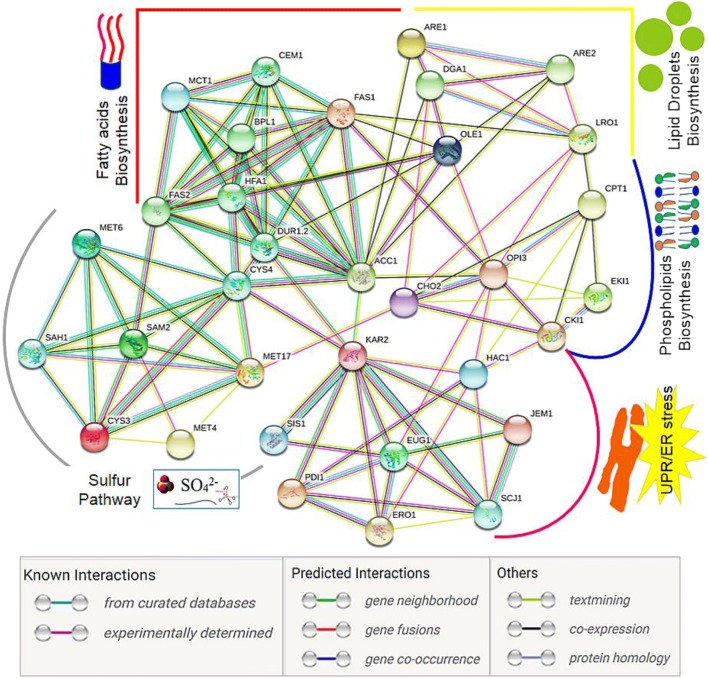

Since Cd cannot be degraded or modified to less toxic forms, it persists in cells and alters cellular homeostasis by provoking oxidative stress and stress response pathways (Ballatori 2002). Apart from these effects, Cd mainly targets the sulphur assimilation pathway and methyl cycle in yeast cells (Mendoza-Cózatl et al. 2005; Sohn et al. 2014). In S. cerevisiae, extracellular sulphate is taken up by sulphate transporters and through the assimilation pathway is reduced to sulphide. The assimilated sulphur will either be incorporated into the sulphur-containing amino acids or into the low-molecular-weight thiol molecules S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and GSH (Wysocki and Tamás 2010). Transcription of the genes encoding the incorporation of assimilated sulphur is regulated by the transcriptional activator Met4p. When cells were subjected to Cd toxicity, MET transcriptional factors like MET4, MET28, MET31, and MET32 were upregulated (Hosiner et al. 2014), indicative of significant links to the sulphur and methyl cycle genes (Tables 3 and 4). SAM regulated de novo PC synthesis genes such as CHO2 and OPI3 that controlled the major membrane phospholipids, PC and PE, in both yeast and mammals (Visram et al. 2018). Deletion of CHO2 and OPI3 induced lipid alterations including TAG, LD accumulation, increased FA content, and altered FA profiles in yeast (Rajakumar et al. 2016a). Additionally, upregulation of phospholipid methyl transferase-encoding genes CHO2 and OPI3 were observed in Cd toxicity. Therefore, using the STRING bioinformatics tool (Jensen et al. 2009), we constructed a protein interaction network in yeast S. cerevisiae. Through applying a cut off on the confidence score from STRING, we used only genes/protein upregulated in Cd stress from different cellular processes such as sulphur pathway, lipid, and FA biogenesis and UPR/ER stress mechanism. The results showed that Acc1, Fas1, and Cho2 directly interact with Cys3, Sam2, and Met17 and also controlled activity of S-adenosyl homocysteine hydrolase (Sah1) (Fig. 5). This data strongly supports the recent findings of S-adenosyl homocysteine as the key trigger of lipid deregulation (Visram et al. 2018). As a response to Cd stress, the host cell’s defence mechanism activates UPR transcription factor and UPR genes and proteins (Table 2) (Gardarin et al. 2010; Wysocki and Tamás 2010; Rajakumar et al. 2016a). Interestingly, the ability of UPR transducers to sense lipid homeostasis disequilibrium is conserved in eukaryotes. Lipid perturbations in yeast induced alterations in protein quality control, with minimal changes to lipid metabolism (Thibault and Ng 2012). Several protein degradation genes control lipid biosynthetic proteins like Rpn4, Ubx2 control Lpl1, and Ole1 activity in yeast (Surma et al. 2013; Weisshaar et al. 2017). The core interaction network contains HAC1 and kar2 interactions between proteins that share with phospholipid synthetic genes OPI3, CKI1, CPT1, and FA enzyme ACC1 (Table 4 and Fig. 5). These results collectively emphasize how Cd-induced cellular processes are interlinked with lipid metabolism.

Table 3.

Significant GO terms associated to the Cd metal stress conditions

| S. No. | GO terms | Proteins | Genes | Transcription factors (TFs) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Sulphur compound metabolism: transsulphuration pathway and methyl cycle | CYS3, SAM2, MET2, MET3, MET5, MET6, MET14, MET16, MET17 | Met4, Met32, Met28 | Hosiner et al. 2014 | |

| 2. | Protein folding and proteasomal degradation/autophagy | Kar2, Atg8, Ape1, Pca1 | PDI1, ERO1, FKB2, MCD1, MPD1, JEM1, KAR2, EUG1, MPD1, LHS1, ATG17 | Hac1, Ire1, Rpn4 | Gardarin et al. 2010; Muthukumar and Nachiappan 2013; Hosiner et al. 2014; Smith et al. 2016 |

| 3. | Lipid and fatty acid metabolism | CHO2, OPI3, CPT1, EKI1, CKI1, ARE1, ARE2, DGA1, LRO1, ACC1, FAS1, OLE1 | Fang et al. 2016; Rajakumar and Nachiappan 2017 |

Table 4.

Protein-protein interaction were analysed with major lipid/fatty acid metabolic related proteins

| Connecting proteins | Phospholipid biosynthesis | Score | Lipid droplet biosynthesis | Score | Fatty acid biosynthesis | Score | Sulphur pathway | Score | UPR | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ACC1 Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 |

OPI3 | 0.524 | DGA1 | 0.786 | FAS1 | 0.999 | CYS4 | 0.901 | KAR2 | 0.630 |

| ARE2 | 0.624 | FAS2 | 0.999 | |||||||

| ARE1 | 0.526 | OLE1 | 0.940 | |||||||

|

FAS1 Fatty acid synthase 1 |

OPI3 | 0.561 | LRO1 | 0.564 | ACC1 | 0.999 | ||||

| FAS2 | 0.999 | |||||||||

| OLE1 | 0.854 | |||||||||

|

FAS2 Fatty acid synthase 2 |

ACC1 | 0.999 | CYS4 | 0.691 | ||||||

| FAS1 | 0.99 | SAM2 | 0.519 | |||||||

| OLE1 | 0.829 | |||||||||

|

OLE1 Fatty acid desaturase |

OPI3 | 0.535 | DGA1 | 0.693 | ACC1 | 0.940 | ||||

| ARE2 | 0.611 | FAS1 | 0.854 | |||||||

| FAS2 | 0.829 | |||||||||

|

OPI3 PL methyl transferase |

CPT1 | 0.997 | LRO1 | 0.591 | FAS1 | 0.561 | HAC1 | 0.607 | ||

| CHO2 | 0.983 | OLE1 | 0.535 | EUG1 | 0.518 | |||||

| CKI1 | 0.794 | ACC1 | 0.524 | |||||||

| EKI1 | 0.687 | |||||||||

|

CHO2 PE methyl transferase |

OPI3 | 0.997 | LRO1 | 0.574 | MET17 | 0.721 | ||||

| CKI1 | 0.782 | DGA1 | 0.524 | |||||||

| CPT1 | 0.763 | |||||||||

| EKI1 | 0.637 | |||||||||

|

CKI1 Choline kinase 1 |

EKI1 | 0.987 | HAC1 | 0.529 | ||||||

| CPT1 | 0.895 | |||||||||

| CHO2 | 0.892 | |||||||||

| OPI3 | 0.794 | |||||||||

|

CPT1 Choline phosphor transferase 1 |

OPI3 | 0.983 | LRO1 | 0.629 | HAC1 | 0.774 | ||||

| CKI1 | 0.895 | |||||||||

| CHO2 | 0.782 | |||||||||

| EKI1 | 0.735 | |||||||||

|

DGA1 Diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 |

CHO2 | 0.524 | LRO1 | 0.998 | ACC1 | 0.786 | ||||

| ARE2 | 0.982 | OLE1 | 0.693 | |||||||

| ARE1 | 0.939 | |||||||||

|

LRO1 Lecithin cholesterol acyl transferase 1 |

CPT1 | 0.629 | DGA1 | 0.998 | FAS1 | 0.564 | ||||

| CHO2 | 0.574 | ARE2 | 0.982 | |||||||

| OPI3 | 0.591 | ARE1 | 0.940 |

Fig. 5.

Network illustrating functional trends of protein participating in dynamic complexes, such as lipid, fatty acid homeostasis, UPR regulations, and transsulphuration pathway

.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Several epidemiologic studies offer the evidence of Cd exposure with adverse effects that induce oxidative stress and is associated with obesity, hyperglycaemia, and type II diabetes (Han et al. 2015; Pizzino et al. 2017). This approach could be useful in endotyping lipid-related disorders, improving exposure assessment, identifying biochemical and transport mechanisms for Cd exposures in S. cerevisiae, and for clarifying the role of the stress scavenging proteins in yeast microbiology.

The ion transport system is essential for Cd influx, accumulation, and toxicity of the cells. This review discusses the involvement of vital metals like Zn and Ca and their transport and homeostatic mechanisms during Cd toxicity. Cd competes for the binding sites of essential metal absorptive and enzymatic proteins (Bridges and Zalups 2005). The replacement of Zn by Cd leads to oxidative stress. The Zn transporters efficiently play a role in LD accumulation during Cd exposure (Rajakumar et al. 2016b). Furthermore, cross-talk regulations of Ca and lipids were observed in yeast cells during Cd stress. Particularly, ER Ca-ATPase SPF1 was downregulated in opi3 deletion strain (Rajakumar et al. 2016a). This result correlated with TAG accumulation during spf1 deletion (Unpublished data) and the LDs effectively rescued the ROS-mediated programmed cell death. This observation showed that LDs play a role in heavy metal-induced oxidative stress. The lipid overload during Cd stress in yeast alleviates the ROS induction and the essential metal imbalances.

The Ca transporters are modulated by membrane lipid composition, protein-protein interaction, and a range of post-translational modifications (Traaseth et al. 2008; Fu et al. 2011). ER Ca-ATPases play a vital role in cellular Ca homeostasis as well as lipid regulation in the cell (Arruda and Hotamisligil, 2015). Thus, understanding the cross-talk mechanism of Ca and lipid homeostasis in yeast can provide a key factor for targeting strategy for the development of therapeutic drugs to combat human diseases such as metabolic syndromes. Moreover, advance studies are required to elucidate the role of metal transport proteins and lipid under Cd toxicity to alleviate the pollutant in the current eco-system.

In the future, studies need to be focused on the role of Zn and Ca and their transport system on lipid homeostasis. Zn limitation has an impact on signalling with the adverse effect on lipid homeostasis (Wei et al. 2018). The identification of target genes that are involved in Cd transport with impact on lipid homeostasis will provide pharmacotherapy progress to treat diseases caused by zinc and Ca alterations during Cd exposure.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abbà S., Vallino M., Daghino S., Di Vietro L., Borriello R., Perotto S. A PLAC8-containing protein from an endomycorrhizal fungus confers cadmium resistance to yeast cells by interacting with Mlh3p. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39(17):7548–7563. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abhishek A, Benita S, Kumari M, Ganesan D, Paul E, Sasikumar P, Mahesh A, Yuvaraj S, Ramprasath T, Selvam GS. Molecular analysis of oxalate induced endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated apoptosis in the pathogenesis of kidney stone disease. J Physiol Biochem. 2017;73:561–573. doi: 10.1007/s13105-017-0587-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adle DJ, Sinani D, Kim H, Lee J. A cadmium-transporting P1B-type ATPase in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:947–955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609535200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar Pablo S., de Mendoza Diego. Control of fatty acid desaturation: a mechanism conserved from bacteria to humans. Molecular Microbiology. 2006;62(6):1507–1514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Kaddissi S, Legeay A, Elia AC, Gonzalez P, Floriani M, Cavalie I, Massabuau J-C, Gilbin R, Simon O. Mitochondrial gene expression, antioxidant responses, and histopathology after cadmium exposure. Environ Toxicol. 2014;29:893–907. doi: 10.1002/tox.21817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand P, Cermelli S, Li Z, Kassan A, Bosch M, Sigua R, Huang L, Ouellette AJ, Pol A, Welte MA, Gross SP. A novel role for lipid droplets in the organismal antibacterial response. eLife. 2012;1:e00003. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda AP, Hotamisligil GS. Calcium homeostasis and organelle function in the pathogenesis of obesity and diabetes. Cell Metab. 2015;22:381–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athenstaedt K, Daum G. Tgl4p and Tgl5p, two triacylglycerol lipases of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae are localized to lipid particles. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37301–37309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey AP, Koster G, Guillermier C, Hirst EMA, MacRae JI, Lechene CP, Postle AD, Gould AP. Antioxidant role for lipid droplets in a stem cell niche of Drosophila. Cell. 2015;163:340–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballatori N. Transport of toxic metals by molecular mimicry. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:689–694. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyersmann Detmar, Hartwig Andrea. Carcinogenic metal compounds: recent insight into molecular and cellular mechanisms. Archives of Toxicology. 2008;82(8):493–512. doi: 10.1007/s00204-008-0313-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleackley MR, MacGillivray RTA. Transition metal homeostasis: from yeast to human disease. BioMetals. 2011;24:785–809. doi: 10.1007/s10534-011-9451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CC, Zalups RK. Molecular and ionic mimicry and the transport of toxic metals. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;204:274–308. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzóska MM, Moniuszko-Jakoniuk J. The influence of calcium content in diet on cumulation and toxicity of cadmium in the organism. Arch Toxicol. 1998;72:63–73. doi: 10.1007/s002040050470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzóska MM, Moniuszko-Jakoniuk J. Interactions between cadmium and zinc in the organism. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001;39:967–980. doi: 10.1016/S0278-6915(01)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschini A, Poli P, Rossi C. Saccharomyces cerevisiae as an eukaryotic cell model to assess cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of three anticancer anthraquinones. Mutagenesis. 2003;18:25–36. doi: 10.1093/mutage/18.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano Soraia M., Menezes Regina, Amaral Catarina, Rodrigues-Pousada Claudina, Pimentel Catarina. Repression of the Low Affinity Iron Transporter GeneFET4. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2015;290(30):18584–18595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.600742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman GM, Han G-S. Regulation of phospholipid synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by zinc depletion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:322–330. doi: 10.1016/J.BBALIP.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona-Gutierrez D, Ruckenstuhl C, Bauer MA, Eisenberg T, Bü Ttner S, Madeo F. Cell death in yeast: growing applications of a dying buddy. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:733–734. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang N, Yao S, Chen D, Zhang L, Huang J, Zhang L (2018) The Hog1 positive regulated YCT1 gene expression under cadmium tolerance of budding yeast. FEMS Microbiol Lett 365(17) doi: 10.1093/femsle/fny170 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chellappa R, Kandasamy P, Oh C-S, Jiang Y, Vemula M, Martin CE. The membrane proteins, Spt23p and Mga2p, play distinct roles in the activation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae OLE1 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43548–43556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107845200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin-Chan M, Navarro-Yepes J, Quintanilla-Vega B. Environmental pollutants as risk factors for neurodegenerative disorders: Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:124. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choong G, Liu Y, Templeton DM. Interplay of calcium and cadmium in mediating cadmium toxicity. Chem Biol Interact. 2014;211:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobbett C, Goldsbrough P. Phytochelatins and metallothioneins: roles in heavy metal detoxification and homeostasis. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53:159–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100301.135154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Y, Megyeri M, Chen OCW, Condomitti G, Riezman I, Loizides-Mangold U, Abdul-Sada A, Rimon N, Riezman H, Platt FM, Futerman AH, Schuldiner M. The yeast P5 type ATPase, Spf1, regulates manganese transport into the endoplasmic reticulum. PLoS One. 2013;8:e85519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin SR, Rao R, Hampton RY. Cod1p/Spf1p is a P-type ATPase involved in ER function and Ca2+ homeostasis. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:1017–1028. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler RG, Kelly J, Storie K, Pedersen WA, Tammara A, Hatanpaa K, Troncoso JC, Mattson MP. Involvement of oxidative stress-induced abnormalities in ceramide and cholesterol metabolism in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2070–2075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305799101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensberger KM, Bird AJ. Hammering out details: regulating metal levels in eukaryotes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:524–531. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eide DJ. Homeostatic and adaptive responses to zinc deficiency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18565–18569. doi: 10.1074/JBC.R900014200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eraso P, Martinez-Burgos M, Falcon-Perez JM, Portillo F, Mazon MJ. Ycf1-dependent cadmium detoxification by yeast requires phosphorylation of residues Ser(908) and Thr(911) FEBS Lett. 2004;577:322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z, Chen Z, Wang S, Shi P, Shen Y, Zhang Y, Xiao J, Huang Z. Overexpression of OLE1 enhances cytoplasmic membrane stability and confers resistance to cadmium in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;83:AEM.02319–AEM.02316. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02319-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauchon M, Lagniel G, Aude J-C, Lombardia L, Soularue P, Petat C, Marguerie G, Sentenac A, Werner M, Labarre J. Sulfur sparing in the yeast proteome in response to sulfur demand. Mol Cell. 2002;9:713–723. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei W, Wang H, Fu X, Bielby C, Yang H. Conditions of endoplasmic reticulum stress stimulate lipid droplet formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem J. 2009;424:61–67. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S, Yang L, Li P, Hofmann O, Dicker L, Hide W, Lin X, Watkins SM, Ivanov AR, Hotamisligil GS. Aberrant lipid metabolism disrupts calcium homeostasis causing liver endoplasmic reticulum stress in obesity. Nature. 2011;473:528–531. doi: 10.1038/nature09968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S, Watkins SM, Hotamisligil GS. The role of endoplasmic reticulum in hepatic lipid homeostasis and stress signaling. Cell Metab. 2012;15:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, Nakayama O, Makishima M, Matsuda M, Shimomura I. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1752–1761. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J, Sturley SL. Homoeostatic systems for sterols and other lipids. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:1182–1185. doi: 10.1042/BST20051182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J, Padamsee M, Wilcox L, Oelkers PM, D’Ambrosio D, Ruggles KV, Ramsey N, Jabado O, Turkish A, Sturley SL. Sterol and diacylglycerol acyltransferase deficiency triggers fatty acid-mediated cell death. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:30994–31005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.050443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardarin A, Chédin S, Lagniel G, Aude J-C, Godat E, Catty P, Labarre J. Endoplasmic reticulum is a major target of cadmium toxicity in yeast. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:1034–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasch AP, Spellman PT, Kao CM, Carmel-Harel O, Eisen MB, Storz G, Botstein D, Brown PO. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:4241–4257. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitan RS, Luo H, Rodgers J, Broderius M, Eide D. Zinc-induced inactivation of the yeast ZRT1 zinc transporter occurs through endocytosis and vacuolar degradation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28617–28624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitan RS, Shababi M, Kramer M, Eide DJ. A cytosolic domain of the yeast Zrt1 zinc transporter is required for its post-translational inactivation in response to zinc and cadmium. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39558–39564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes DS, Fragoso LC, Riger CJ, Panek AD, Eleutherio EC. Regulation of cadmium uptake by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1573:21–25. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenendyk J, Sreenivasaiah PK, Kim DH, Agellon LB, Michalak M. Biology of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the heart. Circ Res. 2010;107:1185–1197. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Ganguly A, Sun L, Suo F, Du LL, Russell P. Global fitness profiling identifies arsenic and cadmium tolerance mechanisms in fission Yeast. G3 (Bethesda) 2016;6(10):3317–3333. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.033829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han GS, Johnston CN, Chen X, Athenstaedt K, Daum G, Carman GM. Regulation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae DPP1-encoded diacylglycerol pyrophosphate phosphatase by zinc. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10126–10133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Ha K, Jeon J, Kim H, Lee K, Kim D. Impact of cadmium exposure on the association between lipopolysaccharide and metabolic syndrome. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:11396–11409. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120911396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hechtenberg S, Beyersmann D. Inhibition of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca (2+)-ATPase activity by cadmium, lead and mercury. Enzyme. 1991;45:109–115. doi: 10.1159/000468875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry SA, Kohlwein SD, Carman GM. Metabolism and regulation of glycerolipids in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2012;190:317–349. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.130286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland WL, Brozinick JT, Wang L-P, Hawkins ED, Sargent KM, Liu Y, Narra K, Hoehn KL, Knotts TA, Siesky A, Nelson DH, Karathanasis SK, Fontenot GK, Birnbaum MJ, Summers SA. Inhibition of ceramide synthesis ameliorates glucocorticoid-, saturated-fat-, and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2007;5:167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath SE, Wagner A, Steyrer E, Daum G. Metabolic link between phosphatidylethanolamine and triacylglycerol metabolism in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1811:1030–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosiner D, Gerber S, Lichtenberg-Fraté H, Glaser W, Schüller C, Klipp E. Impact of acute metal stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One. 2014;9:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh W-K, Falvo JV, Gerke LC, Carroll AS, Howson RW, Weissman JS, O’Shea EK. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC Cadmium and cadmium compounds. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1993;58:119–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs RL, Zhao Y, Koonen DPY, Sletten T, Su B, Lingrell S, Cao G, Peake DA, Kuo M-S, Proctor SD, Kennedy BP, Dyck JRB, Vance DE. Impaired de Novo choline synthesis explains why phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase-deficient mice are protected from diet-induced obesity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22403–22413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.108514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järup L, Åkesson A. Current status of cadmium as an environmental health problem. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;238:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Stark M, Chaffron S, Creevey C, Muller J, Doerks T, Julien P, Roth A, Simonovic M, Bork P, von Mering C. STRING 8—a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D412–D416. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin YH, Dunlap PE, McBride SJ, Al-Refai H, Bushel PR, Freedman JH. Global transcriptome and deletome profiles of yeast exposed to transition metals. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jomova K, Valko M. Advances in metal-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Toxicol. 2011;283:65–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonikas MC, Collins SR, Denic V, Oh E, Quan EM, Schmid V, Weibezahn J, Schwappach B, Walter P, Weissman JS, Schuldiner M. Comprehensive characterization of genes required for protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 2009;323:1693–1697. doi: 10.1126/science.1167983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphorst JJ, Cross JR, Fan J, de Stanchina E, Mathew R, White EP, Thompson CB, Rabinowitz JD. Hypoxic and Ras-transformed cells support growth by scavenging unsaturated fatty acids from lysophospholipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8882–8887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307237110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y-C, Ntambi JM. Regulation of stearoyl-CoA desaturase genes: role in cellular metabolism and preadipocyte differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;266:1–4. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SC, Cho MK, Kim SG. Cadmium-induced non-apoptotic cell death mediated by oxidative stress under the condition of sulfhydryl deficiency. Toxicol Lett. 2003;144(3):325–336. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(03)00233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch Barbara, Schmidt Claudia, Daum Günther. Storage lipids of yeasts: a survey of nonpolar lipid metabolism inSaccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia pastoris, andYarrowia lipolytica. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2014;38(5):892–915. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Marino G, Levine B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell. 2010;40:280–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumpe K, Frumkin I, Herzig Y, Rimon N, Özbalci C, Brügger B, Rapaport D, Schuldiner M. Ergosterol content specifies targeting of tail-anchored proteins to mitochondrial outer membranes. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:3927–3935. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo N, Nakagawa Y, Waku K, Kawashima Y, Kozuka H. Prevention by zinc of cadmium inhibition of stearoyl-CoA desaturase in rat liver. Toxicol. 1991;68:133–142. doi: 10.1016/0300-483X(91)90016-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwast KE, Burke PV, Staahl BT, Poyton RO. Oxygen sensing in yeast: evidence for the involvement of the respiratory chain in regulating the transcription of a subset of hypoxic genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5446–5451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Godon C, Lagniel G, Spector D, Garin J, Labarre J, Toledano MB. Yap1 and Skn7 control two specialized oxidative stress response regulons in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16040–1604610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligr M, Madeo F, Fröhlich E, Hilt W, Fröhlich K-U, Wolf DH. Mammalian Bax triggers apoptotic changes in yeast. FEBS Lett. 1998;438:61–65. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listenberger LL, Ory DS, Schaffer JE. Palmitate-induced apoptosis can occur through a ceramide-independent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14890–14895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listenberger LL, Han X, Lewis SE, Cases S, Farese RV, Ory DS, Schaffer JE. Triglyceride accumulation protects against fatty acid-induced lipotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3077–3082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630588100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Yang J, Li Y, Zhang M, Wang L. Cd-induced apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway in the hepatopancreas of the freshwater crab Sinopotamon henanense. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low C, Liew L, Pervaiz S, Yang H. Apoptosis and lipoapoptosis in the fission yeast. FEMS Yeast Res. 2005;5:1199–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.femsyr.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luevano J, Damodaran C. A review of molecular events of cadmium-induced carcinogenesis. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2014;33:183–194. doi: 10.1615/JEnvironPatholToxicolOncol.2014011075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra JD, Kaufman RJ. ER stress and its functional link to mitochondria: role in cell survival and death. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004424–a004424. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manon S. Utilization of yeast to investigate the role of lipid oxidation in cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6:259–267. doi: 10.1089/152308604322899323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CE, Oh C-S, Jiang Y. Regulation of long chain unsaturated fatty acid synthesis in yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:271–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola Daiane, Pimentel Catarina, Caetano Soraia, Amaral Catarina, Menezes Regina, Santos Claudia N., Eleutherio Elis, Rodrigues-Pousada Claudina. Inhibition of Yap2 activity by MAPKAP kinase Rck1 affects yeast tolerance to cadmium. FEBS Letters. 2015;589(19PartB):2841–2849. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Cózatl D, Loza-Tavera H, Hernández-Navarro A, Moreno-Sánchez R. Sulfur assimilation and glutathione metabolism under cadmium stress in yeast, protists and plants. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:653–671. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhashi S, Ohkuma A, Talim B, Karahashi M, Koumura T, Aoyama C, Kurihara M, Quinlivan R, Sewry C, Mitsuhashi H, Goto K, Koksal B, Kale G, Ikeda K, Taguchi R, Noguchi S, Hayashi YK, Nonaka I, Sher RB, Sugimoto H, Nakagawa Y, Cox GA, Topaloglu H, Nishino I. A congenital muscular dystrophy with mitochondrial structural abnormalities caused by defective de novo phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:845–851. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Watanabe T, Sato M, Momose Y, Nakahara T, Oka S, Iwahashi H. Dimethyl sulfoxide exposure facilitates phospholipid biosynthesis and cellular membrane proliferation in yeast cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33185–33193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300450200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumar K, Nachiappan V. Phosphatidylethanolamine from phosphatidylserine decarboxylase 2 is essential for autophagy under cadmium stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2013;67:1353–1363. doi: 10.1007/s12013-013-9667-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumar K, Rajakumar S, Sarkar MN, Nachiappan V. Glutathione peroxidase 3 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae protects phospholipids during cadmium-induced oxidative stress. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2011;99:761–771. doi: 10.1007/s10482-011-9550-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair AR, Degheselle O, Smeets K, Van Kerkhove E, Cuypers A. Cadmium-induced pathologies: where is the oxidative balance lost (or not)? Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:6116–6143. doi: 10.3390/ijms14036116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatogawa H, Ichimura Y, Ohsumi Y. Atg8, a ubiquitin-like protein required for autophagosome formation, mediates membrane tethering and hemifusion. Cell. 2007;130:165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargund AM, Avery SV, Houghton JE. Cadmium induces a heterogeneous and caspase-dependent apoptotic response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Apoptosis. 2008;13:811–82110. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebauer R, Rosenberger S, Daum G. Phosphatidylethanolamine, a limiting factor of autophagy in yeast strains bearing a defect in the carboxypeptidase Y pathway of vacuolar targeting. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16736–16743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611345200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg GF. Historical perspectives on cadmium toxicology. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;238:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcan U, Cao Q, Yilmaz E, Lee A-H, Iwakoshi NN, Ozdelen E, Tuncman G, Görgün C, Glimcher LH, Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2004;306:457–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1103160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira C, Miguel Martins L, Saraiva L. LRRK2, but not pathogenic mutants, protects against H2O2 stress depending on mitochondrial function and endocytosis in a yeast model. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:2025–2031. doi: 10.1016/J.BBAGEN.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petschnigg J, Wolinski H, Kolb D, Zellnig G, Kurat CF, Natter K, Kohlwein SD. Good fat, essential cellular requirements for triacylglycerol synthesis to maintain membrane homeostasis in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:30981–30993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.024752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierron F, Baudrimont M, Bossy A, Bourdineaud J, Brethes D, Elie P, Massabuau J. Impairment of lipid storage by cadmium in the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) Aquat Toxicol. 2007;81:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzino G, Irrera N, Bitto A, Pallio G, Mannino F, Arcoraci V, Aliquò F, Minutoli L, De Ponte C, D’andrea P, Squadrito F, Altavilla D. Cadmium-induced oxidative stress impairs glycemic control in adolescents. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2017/6341671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahoui S, Chaoui A, El Ferjani E. Membrane damage and solute leakage from germinating pea seed under cadmium stress. J Hazard Mater. 2010;178:1128–1131. doi: 10.1016/J.JHAZMAT.2010.01.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumar S, Nachiappan V. Lipid droplets alleviate cadmium induced cytotoxicity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Toxicol Res. 2017;6:30–41. doi: 10.1039/C6TX00187D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumar S, Bhanupriya N, Ravi C, Nachiappan V. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and calcium imbalance are involved in cadmium-induced lipid aberrancy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2016;21:895–906. doi: 10.1007/s12192-016-0714-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumar S, Ravi C, Nachiappan V. Defect of zinc transporter ZRT1 ameliorates cadmium induced lipid accumulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metallomics. 2016;8:453–460. doi: 10.1039/C6MT00005C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regalla Lisa M., Lyons Thomas J. Topics in Current Genetics. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2005. Zinc in yeast: mechanisms involved in homeostasis; pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rogalska J, Brzóska MM, Roszczenko A, Moniuszko-Jakoniuk J. Enhanced zinc consumption prevents cadmium-induced alterations in lipid metabolism in male rats. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;177:142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruta LL, Popa VC, Nicolau L, Danet AF, Iordache V, Neagoe AD, Farcasanu IC. Calcium signaling mediates the response to cadmium toxicity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:3202–3212. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrey P, Wittsiepe J, Budde U, Heinzow B, Idel H, Wilhelm M, Wilhelm M. Dietary intake of lead, cadmium, copper and zinc by children from the German North Sea island Amrum. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2000;203:1–9. doi: 10.1078/S1438-4639(04)70001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder M, Kaufman RJ. ER stress and the unfolded protein response. Mutat Res. 2005;569:29–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuldiner M, Collins SR, Thompson NJ, Denic V, Bhamidipati A, Punna T, Ihmels J, Andrews B, Boone C, Greenblatt JF, Weissman JS, Krogan NJ. Exploration of the function and organization of the yeast early secretory pathway through an epistatic miniarray profile. Cell. 2005;123:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon A, Finkelstein A, Shlezinger N, Hatam I. Fungal apoptosis: function, genes and gene functions. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33:833–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheibani S, Richard VR, Beach A, Leonov A, Feldman R, Mattie S, Khelghatybana L, Piano A, Greenwood M, Vali H, Titorenko VI. Macromitophagy, neutral lipids synthesis, and peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation protect yeast from “liponecrosis”, a previously unknown form of programmed cell death. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:138–147. doi: 10.4161/cc.26885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivapurkar N, Reddy J, Chaudhary PM, Gazdar AF. Apoptosis and lung cancer: a review. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:885–898. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Yadav KK, Rajasekharan R. ZAP1-mediated modulation of triacylglycerol levels in yeast by transcriptional control of mitochondrial fatty acid biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol. 2016;100:55–75. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N, Wei W, Zhao M, Qin X, Seravalli J, Kim H, Lee J. Cadmium and secondary structure-dependent function of a degron in the Pca1p cadmium exporter. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:12420–12431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.724930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn MJ, Yoo SJ, Oh D-B, Kwon O, Lee SY, Sibirny AA, Kang HA. Novel cysteine-centered sulfur metabolic pathway in the thermotolerant methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Cardalda A, Fakas S, Pascual F, Choi H-S, Carman GM. Phosphatidate phosphatase plays role in zinc-mediated regulation of phospholipid synthesis in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:968–977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.313130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surma MA, Klose C, Peng D, Shales M, Mrejen C, Stefanko A, Braberg H, Gordon DE, Vorkel D, Ejsing CS, Farese R, Simons K, Krogan NJ, Ernst R. A lipid E-MAP identifies Ubx2 as a critical regulator of lipid saturation and lipid bilayer stress. Mol Cell. 2013;51:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple MD, Perrone GG, Dawes IW. Complex cellular responses to reactive oxygen species. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:319–32610. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevenod F. Cadmium and cellular signaling cascades: to be or not to be? Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;238:221–239. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault G., Ng D. T. W. The Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Degradation Pathways of Budding Yeast. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2012;4(12):a013193–a013193. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault G, Shui G, Kim W, McAlister GC, Ismail N, Gygi SP, Wenk MR, Ng DTW. The membrane stress response buffers lethal effects of lipid disequilibrium by reprogramming the protein homeostasis network. Mol Cell. 2012;48:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JE, Froese CD, Madey E, Smith MD, Hong Y. Lipid metabolism during plant senescence. Prog Lipid Res. 1998;37:119–141. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7827(98)00006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorburn A. Autophagy and disease. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(15):5425–5430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R117.810739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong AHY, Lesage G, Bader GD, Ding H, Xu H, Xin X, Young J, Berriz GF, Brost RL, Chang M, Chen Y, Cheng X, Chua G, Friesen H, Goldberg DS, Haynes J, Humphries C, He G, Hussein S, Ke L, Krogan N, Li Z, Levinson JN, Lu H, Ménard P, Munyana C, Parsons AB, Ryan O, Tonikian R, Roberts T, Sdicu A-M, Shapiro J, Sheikh B, Suter B, Wong SL, Zhang LV, Zhu H, Burd CG, Munro S, Sander C, Rine J, Greenblatt J, Peter M, Bretscher A, Bell G, Roth FP, Brown GW, Andrews B, Bussey H, Boone C. Global mapping of the yeast genetic interaction network. Science. 2004;303:808–813. doi: 10.1126/science.1091317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traaseth NJ, Ha KN, Verardi R, Shi L, Buffy JJ, Masterson LR, Veglia G. Structural and dynamic basis of phospholamban and sarcolipin inhibition of Ca (2+)-ATPase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3–13. doi: 10.1021/bi701668v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsaluchidu S, Cocchi M, Tonello L, Puri BK. Fatty acids and oxidative stress in psychiatric disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-S1-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch RG. Fatty acid unsaturation, mobilization, and regulation in the response of plants to stress. Biotechnol Lett. 2008;30:967–977. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9639-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A. Physiology and pathophysiology of the calcium store in the endoplasmic reticulum of neurons. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:201–279. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vido K, Spector D, Lagniel G, Lopez S, Toledano MB, Labarre J. A proteome analysis of the cadmium response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8469–8474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008708200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visram M, Radulovic M, Steiner S, Malanovic N, Eichmann TO. Wolinski H, Rechberger GN, Tehlivets O. Homocysteine regulates fatty acid and lipid metabolism in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:5544–5555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.809236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther TC, Farese RV., Jr Lipid droplets and cellular lipid metabolism. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:687–714. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061009-102430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C-W. Lipid droplet dynamics in budding yeast. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:2677–2695. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1903-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XH, Liu H, Yi HL. Involvement of ROS and calcium in cadmium-induced yeast cell death. Acta Sci Circumst. 2014;34:1869–1873. [Google Scholar]

- Wei CC, Luo Z, Hogstrand C, Xu YH, Wu LX, Chen GH, Pan YX, Song YF. Zinc reduces hepatic lipid deposition and activates lipophagy via Zn2+/MTF-1/PPARα and Ca2+/CaMKKβ/AMPK pathways. FASEB J. 2018;32:6666–6680. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisshaar N, Welsch H, Guerra-Moreno A, Hanna J. Phospholipase Lpl1 links lipid droplet function with quality control protein degradation. Mol Biol Cell. 2017;28:716–725. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-10-0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wemmie JA, Szczypka MS, Thiele DJ, Moye-Rowley WS. Cadmium tolerance mediated by the yeast AP-1 protein requires the presence of an ATP-binding cassette transporter-encoding gene, YCF1. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32592–32597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk MR. The emerging field of lipidomics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:594–610. doi: 10.1038/nrd1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C-Y, Roje S, Sandoval FJ, Bird AJ, Winge DR, Eide DJ. Repression of sulfate assimilation is an adaptive response of yeast to the oxidative stress of zinc deficiency. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27544–27556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki R, Tamás MJ. How Saccharomyces cerevisiae copes with toxic metals and metalloids. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34:925–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Shao M, Lai L, Liu Y, Fan J. Inhibition of autophagy contributes to the toxicity of cadmium telluride quantum dots in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016;11:3371–3383. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S108636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong B, Zhang L, Xu H, Yang Y, Jiang L. Cadmium induces the activation of cell wall integrity pathway in budding yeast. Chem Biol Interact. 2015;240:316–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang GH, Yamaguchi M, Kimura S, Higham S, Kraus-Friedmann N. Effects of heavy metal on rat liver microsomal Ca (2+)-ATPase and Ca2+ sequestering. Relation to SH groups. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2184–2189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Qi H, Taylor R, Xu W, Liu LF, Jin S. The role of autophagy in mitochondria maintenance: characterization of mitochondrial functions in autophagy-deficient S. cerevisiae strains. Autophagy. 2007;3:337–346. doi: 10.4161/auto.4127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Eide D. The ZRT2 gene encodes the low affinity zinc transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23203–23210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Eide D. The yeast ZRT1 gene encodes the zinc transporter protein of a high-affinity uptake system induced by zinc limitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:2454–2458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]