Abstract

Temperature is a critical factor of insect population abundance and distribution. Monochamus alternatus Hope (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) is a significant concern since it is transmitted vector of the pinewood nematode posing enormous economic and environmental losses. This pest shows tolerance to heat stress, especially extremely high temperatures. Exposing for 6, 12, 24, 48, or 96 h, the 50% median lethal temperatures (Ltem50) for fourth-instar larvae were 47.5, 45.5, 43.9, 43.4, and 42.3°C, respectively. A total of 63,360 unigenes were obtained from complementary DNA libraries of M. alternatus fourth-instar larvae (kept at 25°C and exposed to 40°C for 3 h) and annotated with six databases. Five hundred sixty-one genes were significantly upregulated, and 245 genes were downregulated after heat stress. The Gene Ontology enrichment analysis showed that most different expression genes are categorized into “protein folding” and “unfold protein binding” terms. In addition, “Longevity regulating pathway-multiple species,” “Antigen processing and presentation” as well as “MAPK signaling pathway” were significantly enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways. Further analysis of different expression genes showed that metabolism processes were suppressed, while ubiquitin proteolytic system, heat shock proteins, immune response, superoxide dismutase, cytochrome P450s, and aldehyde dehydrogenase were induced after heat shock. The stress signaling transduction pathways such as MAPK, Hippo, and JAK-STAT might be central convergence points in M. alternatus heat tolerance mechanism. The expression levels from quantitative real-time PCR of 13 randomly selected genes were consistent with the transcriptome results. These results showed that M. alternatus possessed strong heat tolerance and genes related to protein activity, immune response, and signal transduction composed of a complicated heat tolerance mechanism of M. alternatus. This research provided new insights into the mechanisms of thermal tolerance in other insects and aided in exploring the function of heat resistance-related genes.

Keywords: heat stress, Monochamus alternatus, transcriptome analysis, heat shock proteins, signal transduction, immune system

Introduction

Insects are the most diverse and successful animal population, with essential roles in the terrestrial ecosystems (Foottit and Adler, 2017). The life histories of insects are determined by many abiotic factors, among which temperatures are vital. Temperature can affect the insect population dynamics and geographical distribution by interfering with their development rate and life cycle, as well as the distributions of host plants (Bale et al., 2002). In the face of global warming, frequent extreme temperatures directly or indirectly limit insect survival and affect all physiological and metabolic processes in insects, such as alimentation, digestion, detoxification, mating, growth, and development (Garrad et al., 2016).

Reversely, insects’ geographic distribution is dramatically confined to tolerance ranges to extreme temperature (Jing and Kang, 2004). Researches manifested that 50% median lethal temperature (Ltem50) in 24 h of many insects, especially beetles, is over 40°C (Johnson et al., 2004; Li, 2014; Lü and Liu, 2017). Their impressive ability to thrive under high temperature is due to their plastic responses, including behavioral avoidance of extreme temperature by, for example, changing their period of activity within a day or shifting their feeding positions on a plant (Huey, 2002; Kuhrt et al., 2006; Dillon et al., 2009), and physiological adjustments, such as diapause, enhancing their fitness and survival rates under stressful temperature conditions.

There is an increasing interest in investigating insects’ adaptive mechanisms against extreme temperatures. Heat stress can trigger conserved modulating genes, which involved in cellular activities, such as metabolism, protein folding, transport, and degradation (Feder and Hofmann, 1999). Most of the genes encoding cytochrome P450s (P450), antioxidative enzymes, and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) are significantly upregulated after heat exposure (Wei et al., 2015; Zhang Y.H. et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017). Constant high-temperature stress is simultaneously capable of inducing genes related to traditional cryoprotectants to protect cells from damage (Wang et al., 2014). Notably, heat shock proteins (HSPs) served as molecular chaperones, reported in Drosophila melanogaster, Glyphodes pyloalis, and Anaphothrips obscurus, are responsible for heat tolerance (Colinet et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2017; Guo and Feng, 2018). In addition, insects could cope with extremely high temperatures by employing immune response and signal transduction (Li et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2017).

De novo transcriptome assembly has been widely applied to detect and identify differential genes under different experimental conditions (He et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017, 2018; Chen et al., 2018), enabling researchers to understand the molecular mechanism of action from a transcriptomics perspective. Different expression gene (DEGs) profiling in this technique presents the advantages of precision, economy, and repeatability, and has been widely used in plants to explore genes related to heat resistance (Li et al., 2015; Yan et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2017), while in insects, comparative transcriptome analysis related to heat responses has been only applied in several species, including G. pyloalis, Cryptolaemus montrouzieri, and Bombyx mori (Wang et al., 2014; Zhang Y.H. et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017).

The pine sawyer beetle, Monochamus alternatus Hope (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), is the primary vector of the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Steiner et Buhrer) Nickle (Aphelenchida: Parasitaphelenchidae), which is the causative agent of devastating pine wilt disease (Mamiya and Enda, 1972) in China and other East Asian countries. The disease, native to North America, was firstly found in Nanjing City, Jiangsu Province, in 1982, and spread over another 15 provinces by 2018 (Hu and Wu, 2018). The occurrence of pine wilt disease is closely related to the wide distribution of M. alternatus, which rests with its strong tolerance to high temperature. As in many parts of China, the maximum temperatures in natural forests often exceed 40°C in summer, and days with temperature over 40°C have been increasing in the last few years (Zhang W. et al., 2015). Therefore, the particular survival mechanism under extremely high temperatures of M. alternatus is needed to be clarified. Although a tentative work of M. alternatus has ever revealed the upregulation of three MaHSPs at 35 and 40°C (Cai et al., 2017), the comprehensive mechanisms of response to heat stress in M. alternatus remained to be further explored by transcriptome sequencing.

In the present study, we conducted the bioactivity of Ltem50 from 6 to 96 h in M. alternatus. We conducted a comparative transcriptomic analysis between M. alternatus larvae exposed at normal and high temperatures to identify the significantly upregulated and downregulated genes related to heat tolerance. We performed an analysis of differential expression genes as well as pathways, and qRT-PCR to validate the RNA-seq data. We aimed to provide a basis for the adaptive mechanism of heat tolerance in M. alternatus and aided in exploring the function of heat resistance-related genes.

Materials and Methods

Insects and Heat Exposure

Second- and third-instar larvae of M. alternatus were collected from host trees, Pinus massoniana, in Jiujiang city, Jiangxi Province, China, and reared individually on an artificial diet at constant temperature 25°C ± 0.5°C, 60% ± 5% relative humidity in darkness as described by Chen et al. (2017). Three-day old molted fourth-instar larvae reared separately in sterile containers (height: 4.2 cm; diameter: 3.5 cm) were exposed to an environmental chamber within a range of temperatures (35, 40, 42.5, 45, 50°C) and held at the temperature for 6, 12, 24, 48, and 96 h, respectively. In total, 1500 fourth-instar larvae (20 × 5 temperature-treatment × 5 time-treatment × 3 replicate) were used in this study. Following incubation for the desired period, containers were transferred to 25°C for recovery. After 48 h, the survival of M. alternatus larvae was counted and those were considered to be dead if no movement was observed when prodded with a dissecting needle (Johnson et al., 2004; Li et al., 2018).

In many parts of China, the summer extreme high temperature (about 40°C) usually lasts for 3–4 h. To perform transcriptomic analysis similar to the natural condition, 3-day-old molted fourth-instar larvae were exposed to 40°C for 3 h as the heat treatment group. Larvae were reared at 25°C as a control group. Each treatment was repeated three times. After the thermal treatment, the three larvae from each group were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for subsequent experiments.

RNA Isolation, Library Construction, and Sequencing

Insect stored at −80°C was crushed individually with a mortar and pestle and then transferred to a 2-ml centrifuge tube (Sagon Biotech, China). The total RNA of each sample was isolated with 1.5 ml of Trizol reagent (TaKaRa, Japan) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The amount of total RNA was detected using the NanoDrop 2000 (Termo, Waltham, MA, United States). Potential RNA degradation and contamination was monitored on 1% agarose gels.

Three independent experimental replicates were used for transcriptomic analysis. A total of 1 μg of RNA from the heat-treated and control larvae was supplied to construct the complementary DNA (cDNA) libraries by NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kits for Illumina (NEB, United States). The mRNA was fragmented and then primed using random hexamers and used as a template for first-strand cDNA synthesis with reverse transcriptase. After purification, cDNA was ligated at the 3′-end with adenine and sequencing adaptors, followed by PCR amplification to create a cDNA library. The cDNA library was then sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform by Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Biotechnology Co. (Shanghai, China). All raw read sequences were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Short Read Archive database under the accession number of PRJNA548205.

Assembly and Functional Annotation

Before sequence assembly, adaptor sequences, sequences containing ambiguous “N” nucleotides (with a ratio of “N” > 10%) and low-quality sequences (with quality scores < 20) were removed. The transcriptomes were assembled using the Trinity program (Grabherr et al., 2011). Based on clean reads, de novo transcriptome assembly into transcripts without a reference genome was carried out. For homology-based annotation, non-redundant sequences were used to search multiple public databases, including Swiss-Prot1, Pfam2, non-redundant protein database, Eukaryotic Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG3), Gene Ontology (GO4), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)5.

Differentially Expressed Gene Analysis

The expression quantity of each gene (fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped fragments) was estimated by Cuffdiff software (Trapnell et al., 2012) based on the length of this gene and the counts of reads mapped to this gene. A gene was considered to be differentially expressed when the results from the above tests were all significant at P-value < 0.05 (false discovery rate ≤ 0.01) and | log2FC| ≥ 1 by DESeq2. The DEGs were then used for GO and KEGG enrichment analyses. The Goatools6 and Perl scripts were used to implement the statistical enrichment of DEGs in the GO and KEGG pathways. P-value-corrected < 0.05 was the threshold value for significant enrichment results.

qRT-PCR Validation

Thirteen genes were randomly selected to quantify the validity of RNA-seq by qRT-PCR in three duplicates. qRT-PCR was performed using cDNA templates of samples from the control and heat treatment groups. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the PrimeScriptTMII 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa) according to the recommended protocol. To test the integrity of cDNA templates, Ribosomal protein 10 (RPL10) was selected as a housekeeping gene (Li et al., 2018). The qRT-PCR primers (Supplementary Table S1) were designed online7. The cDNA templates in 10-fold dilution series were used to construct a relative standard curve to determine the PCR efficiency, and all primers reached amplification efficiencies of 95–100%.

qRT-PCR was performed in an Applied Biosystem 7500 System (United States) using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The cycling conditions were as follows: (i) 95°C, 30 s; (ii) 95°C, 5 s; (iii) 60°C, 34 s; and (iv) repeat (ii–iii) for 40 cycles. The procedure was followed by an analysis of melting curves ranging from 60°C to 95°C to verify the presence of a single and discrete peak for each reaction product. Each reaction was run in triplicate, and the average threshold cycle (Ct) was calculated for each replicate. The results of qRT-PCRs were analyzed by the 2–ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Statistical Analysis

In heat resistance assays, survival rates were arcsine square-root transformed to normalize variance of the data before analysis. Ltem50 values expressed lethal effects of various levels of temperature in a given period. Probit analysis was performed to estimate these values by SPSS 20.0 software (Finney, 1971).

Results

Heat Tolerance of M. alternatus Fourth-Instar Larvae

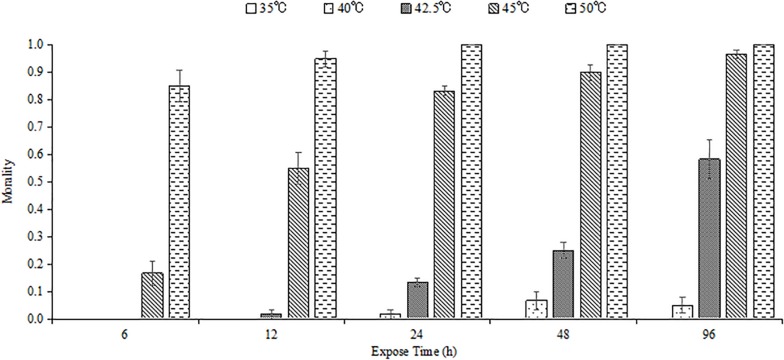

High temperature and exposure duration influenced the survival of M. alternatus larvae, and mortality increased with enhanced temperature and extended exposure time (Figure 1). Most of the fourth-instar larvae could endure 35 and 40°C for all the tested time. No individual survived when exposed to 50°C for 24 h or longer.

FIGURE 1.

Mean mortality of M. alternatus fourth-instar larvae exposed to different high temperatures for 6, 12, 24, 48, and 96 h. Each statistic is the mean of three replicates of 20 larvae per replicate.

Ltem50 values in each experimental time were calculated and are shown in Table 1. Ltem50 of M. alternatus larvae declined with increasing treatment time in general. When exposed for 6, 12, 24, 48, or 96 h, the Ltem50 values for fourth-instar larvae were 47.5, 45.5, 43.9, 43.4, and 42.3°C, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Fifty percent median lethal temperature (Ltem50) for M. alternatus fourth-instar larvae when exposed to a range of temperatures for various durations.

| Exposure | Ltem50 (°C) | Slope | Intercept | Chi-square | P-value |

| time (h) | (95% LCL–UCL) | (χ2) | |||

| 6 | 47.5 (46.9–48.2) | 0.437 | −20.772 | 6.784 | 0.913 |

| 12 | 45.5 (44.8–46.3) | 0.466 | −21.196 | 19.939 | 0.097 |

| 24 | 43.8 (43.4–44.2) | 0.719 | −31.497 | 14.971 | 0.309 |

| 48 | 43.2 (42.2–44.3) | 0.583 | −25.178 | 5.725 | 0.126 |

| 96 | 42.3 (41.9–42.6) | 0.701 | −29.616 | 5.896 | 0.950 |

LCL, lower control limit; UCL, upper control limit.

mRNA Sequencing and Assembly

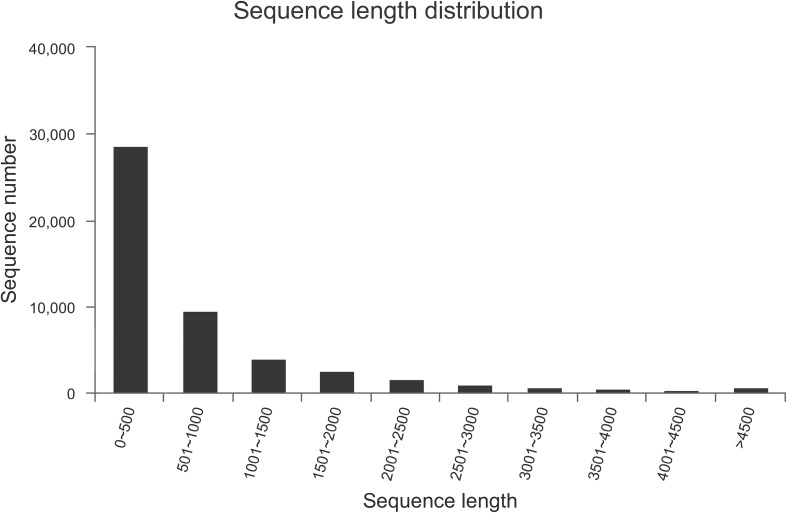

We performed transcriptome sequencing to obtain unigenes information of M. alternatus, and major characteristics of RNA-seq are summarized in Tables 2, 3. We obtained 14.92 Gb of data and 63,360 unigenes in total. The total and average length of these unigenes were 75,544,544 and 819 bp, respectively, and the N50 was 1590 bp. RNA-seq showed high sequencing quality with 38.70% GC content, over 93 and 97% clean reads of Q20 and Q30, respectively (Tables 2, 3). Unigene length distributions were also determined, with most unigenes being <500 bp (Figure 2). The M. alternatus sequences showed 59.05% matches with Anoplophora glabripennis (Supplementary Figure S1). We detected 33,060 coding sequences by performing functional annotations.

TABLE 2.

Quality and base content of RNA-seq.

| Sample | Total | Total length | Mean length | N50 | GC |

| number | (bp) | (bp) | (%) | ||

| All unigenes | 63,360 | 75,544,544 | 819 | 1590 | 38.70 |

TABLE 3.

Distribution and quality metrics of unigenes.

| Sample | Control group | Heat shock group |

| Total raw reads (Mb) | 51.79 | 52.97 |

| Total clean reads (Mb) | 50.06 | 51.38 |

| Total clean bases (Gb) | 7.36 | 7.56 |

| Clean reads Q20 (%) | 97.59 | 97.77 |

| Clean reads Q30 (%) | 93.18 | 93.61 |

| Clean reads ratio (%)a | 96.66 | 97.80 |

aQ20/Q30: the ratio of bases, the quality of which is >20/30.

FIGURE 2.

Length and number distribution of unigenes.

Functional Annotation

Moreover, unigenes were annotated with six functional databases described above, and 23,611 (48.21%), 18,257 (37.28%), 17,827 (36.40%), 3647 (7.45%), 13,033 (26.61%), and 13,848 (28.28%) genes were mapped to the six databases, respectively. GO, KEGG, and COG annotation were applied to provide comprehensive functional information for each transcript (Ogata et al., 2000). We annotated 63360 DEGs into three GO categories by GO analysis: biological processes (42.75%), cellular components (45.92%), and molecular function (25.05%). Among which, “cellular process” and “metabolic process” were dominated in the “biological process.” “Cell” and “cell part” were the most representative terms in the “cellular components.” “Binding” and “catalytic activity” were abundant mostly in “molecular function” categories. In addition, 8686 (13.71%) unique transcripts were assigned GO terms from all three categories (Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figure S2). In this study, 19157 unigenes were mapped to 43 secondary pathways. Apart from “Human diseases,” the major pathways in this study were “metabolic pathways” (22.07%). Furthermore, “signal transduction” and “Translation” are the main two secondary pathways (Supplementary Table S3 and Supplementary Figure S3). A total of 1999 unigenes were assigned appropriate COG clusters, which could be classified into 24 functional categories (Supplementary Table S4). Among them, the largest category was “Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis” (15.01%); followed by “Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones” (13.26%).

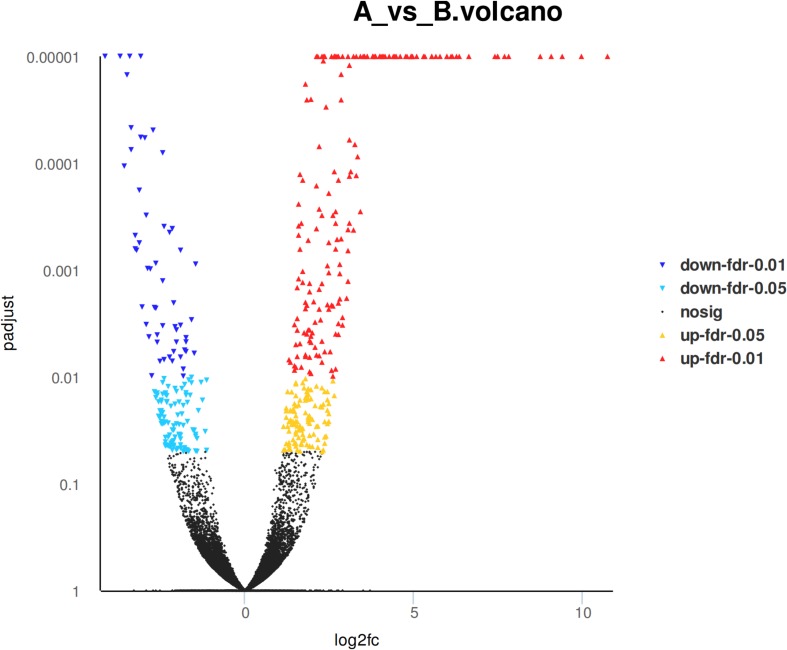

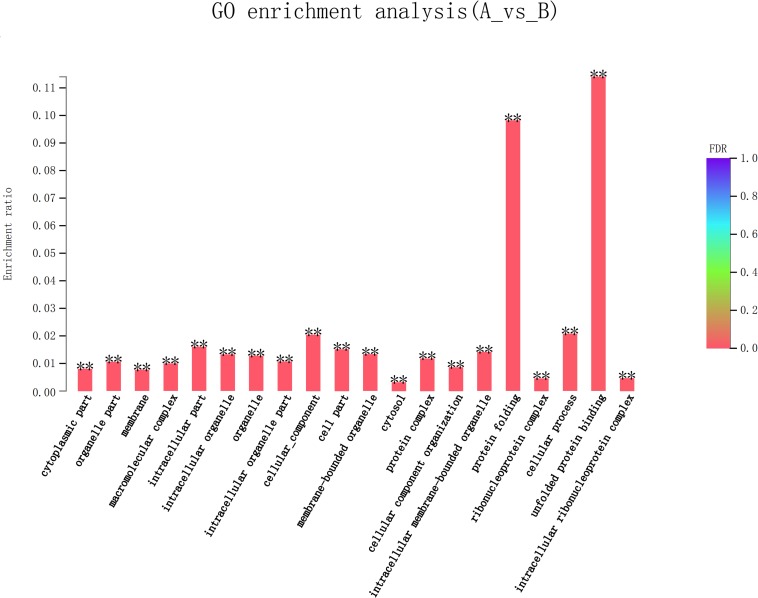

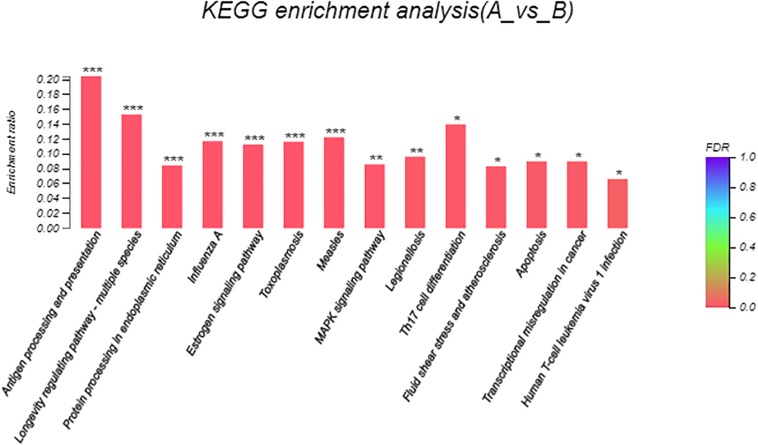

Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

Eight hundred six unigenes were DEGs after heat shock treatment, with a criterion of P-adjust < 0.05 and | log2FC| ≥ 1. There were 545 DEGs upregulated and 261 DEGs downregulated (Figure 3). GO and KEGG enrichment focusing on DEGs could aid in understanding the transcriptional response to heat stress in M. alternatus. Figure 4 shows Top20 GO enrichment terms (P-value < 0.05), which showed that “protein folding” and “unfold protein binding” are highly enriched. Most of these GO enrichment terms are categorized into “cellular components” and “biological processes.” DEGs (P-value < 0.05) were subjected to KEGG enrichment similarly. “Longevity regulating pathway-multiple species” and “Antigen processing and presentation” were the two most significantly enriched KEGG pathways (Figure 5). Notably, the “MAPK signaling pathway” and “Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum” were also dominant among the significantly enriched pathways.

FIGURE 3.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in M. alternatus between control (A) and heat shock (B) samples.

FIGURE 4.

Top 20 Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between control (A) and heat shock (B) samples. False discovery rate (FDR) < 0.01 was marked as ∗∗.

FIGURE 5.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between control (A) and heat shock (B) samples. FDR < 0.001 was marked as ∗∗∗, FDR < 0.01 was marked as ∗∗, and FDR < 0.05 was marked as ∗.

To further investigate the mechanism in M. alternatus responding to heat, we perform further analyses about DEGs involved in GO and KEGG enrichment. Unigenes related to metabolism, protein aggregation, HSPs, immune response, antioxidant, and detoxification, as well as signal transduction were predicted to deal with heat stress in M. alternatus.

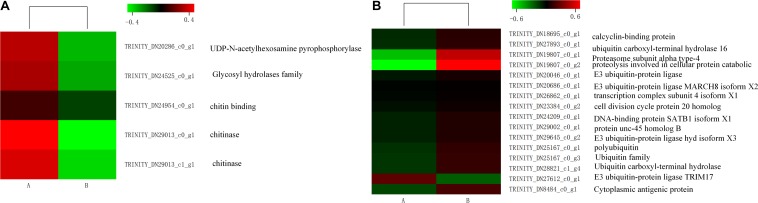

Metabolism Inhibition and Protein Aggregation

Some genes related to carbohydrate metabolism were downregulated, such as amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism, showing in Figure 6A. Interestingly, some unigenes associated with misfolding protein turnover processes were upregulated after heat stress treatment. For example, 15 out of 16 genes encoding ubiquitin were significantly induced in the treatment group (Figure 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Comparative distribution of heat shock protein (HSP)-coding genes between the control (A) and heat shock (B) groups. The color scale denotes the lowest (green) (A) to the highest (red) (B) RPKM values.

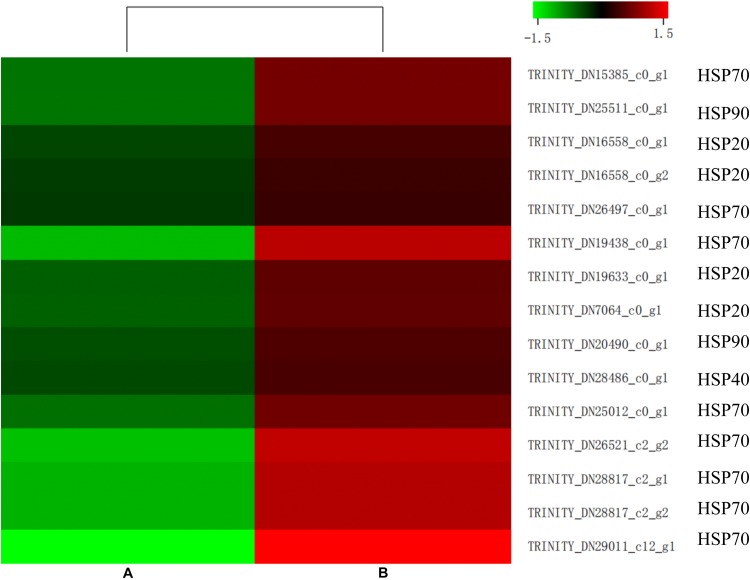

Heat Shock Proteins

Insects can induce a large number of HSPs after heat exposure, implying that these genes play a vital role in the insect’s molecular mechanism to resist high temperatures (Lang et al., 2009). Our research observed a highly transcriptional level of HSPs after heat stress. HSPs, classified into HSP100, HSP90, HSP70, HSP40, and HSP20 family based on its molecular weight, were upregulated (false discovery rate ≤ 0.001) in the heat-treatment group (Figure 7). Among these 15 induced HSPs, 8 were in the HSP70 family, 4 were part of the HSP20 family, but only 1 and 2 were in the HSP40 and HSP90 families, respectively.

FIGURE 7.

Expression level of genes involved in amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism (A) and some genes of ubiquitin (B) in control (A) and heat shock (B) samples. The color scale indicates the lowest (green) to the highest (red) RPKM values.

Immune Response

The RNA-seq analysis revealed that immune-related genes were abundant. A large number of these unigenes were induced in response to heat stress. These genes were mainly involved in pathways related to disease, for example, Epstein–Barr virus infection (13 genes), measles (12 genes), and proteoglycans in cancer (10 genes). Besides, 17 unigenes involved in antigen processing and presentation and 9 unigenes involved in apoptosis were upregulated (Figures 8A,B). Seven genes encoding lysozymes, not belonging to the pathways mentioned above, related to immune defense mechanisms were identified (Figure 8C).

FIGURE 8.

Heatmap of the expression level of antigen processing and presentation (A), apoptosis (B), and genes were involved in lysozymes pathways (C) in control (A) and heat shock samples (B). The color scale indicates the lowest (green) to the highest (red) RPKM values.

Antioxidant and Detoxification

Apart from HSPs, several genes related to antioxidant and detoxification were elicited after heat stress. These genes included one superoxide dismutase (SOD) and three detoxification-related genes, such as genes encoding cytochrome P450s (CYPs) and one gene encoding ALDH (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Changes in the transcriptional expression of genes involved in antioxidant and detoxification of M. alternatus after exposed to 40°C for 3 h.

| Gene ID | Control | Heat shock | Regulated | P-value | Gene description |

| TRINITY_DN19531_c0_g1 | 0.32 | 1.506666667 | Up | 0.0050158 | [Cu–Zn] SOD |

| TRINITY_DN25891_c0_g1 | 20.48666667 | 99.02666667 | Up | 1.56E–07 | CYP18A1 |

| TRINITY_DN26844_c0_g1 | 1.986666667 | 5.003333333 | Up | 0.001263073 | CYP6 |

| TRINITY_DN27264_c2_g2 | 357.3933333 | 556.2533333 | Up | 1.41E–05 | CYP6 |

| TRINITY_DN25440_c0_g2 | 258.4266667 | 867.65 | Up | 3.52E–09 | ALDH |

Stress Signal Transduction

Stress signal transduction plays a vital role in insect heat tolerance. Many pathways related to this process were abundant in this study, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling (13 DEGs), focal adhesion (7 DEGs), Hippo signaling (5 DEGs), PI3K-Akt signaling (5 DEGs), and Janus kinase signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) signaling (4 DEGs) pathways (Supplementary Figure S4).

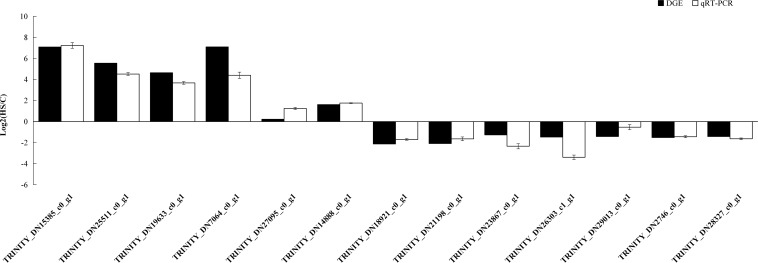

Validation of Data Through qRT-PCR

Hundreds of genes showed significantly different expression levels between the control and heat treatment groups. Thirteen genes were randomly selected to evaluate the accuracy of transcriptome sequencing through qRT-PCR. The results showed that expression levels of genes related to heat stress tolerance were upregulated at 40°C. These genes included those encoding HSP70 (TRINITY_DN15385_c0_g1), HSP90 (TRINITY_DN25511_c0_g1), and HSP20 (TRINITY_DN19633_c0_g1 and TRINITY_DN_7064_c0_g_1). We also found that the expression level of RPL10, used as an internal control, was stable. The expression levels from qRT-PCR of 13 randomly selected genes were consistent with the DEG expression profiling from transcriptomic results (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

qRT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of 13 unigenes. X axis represents the 13 unigenes: TRINITY_DN15385_c0_g1, HSP70; TRINITY_DN25511_c0_g1, HSP70; TRINITY_DN19633_c0_g1, HSP20; TRINITY_DN7064_c0_g1, HSP20; TRINITY_DN27095_c0_g1, glucose dehydrogenase; TRINITY_DN14888 _c0_g1, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; TRINITY_DN18921_c0_g1, general odorant-binding protein; TRINITY_DN21198_c0_g1,beta-1,4-mannosyl-glycoprotein 4-beta-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase TRINITY_DN23867_c0_g1, beta-1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase bre-4; TRINITY_DN26303_c1_g1, glutathione S-transferase; TRINITY_DN29013_c0_g1, glycosyl hydrolase family 18; TRINITY_DN2746_c0_g1, zinc finger protein Elbow-like; TRINITY_DN28327_c0_g1, multidrug resistance-associated protein. The Y axis represents the relative expression levels of genes. Ribosomal protein10 (RPL10) was used as an internal control.

Discussion

High temperatures had adverse effects on insect development and distribution. M. alternatus was mainly distributed in the subtropical and tropical regions, which meant that this pest could continue to thrive in continuous hot weather. Accordingly, we first attempted to investigate the resistance of M. alternatus larvae against high temperatures. As confirmed by bioassay, the Ltem50 of this pest is higher than that of other insects settling in temperature zones. Xylotrechus rusticus was a stem-boring pest that mainly occurred in Northeast of China, and the Ltem50 of this pest was 36.1°C (33.7–38.1°C) in 96 h largely lower than that of M. alternatus (Li, 2014). Similarly, Frankliniella occidentalis, originating from western North America, could not survive after exposure to 41°C for 2 h, whereas over 90% M. alternatus larvae could survive on 40°C for 96 h. The property of strong heat tolerance in M. alternatus evoked great interest from its mechanism responding to high temperature.

RNA-seq could present a comprehensive and accurate gene expression profile for diverse experimental conditions. This technology has been used in M. alternatus recently. A previous study had analyzed the RNA-seq data of larval sawyer beetle treated with insecticide (Wu et al., 2016). Here, we detected 33,060 coding sequences in M. alternatus and observed 806 DEGs after heat treatment, which could contribute to underlying tolerant events in M. alternatus. The specific function of these unigenes could be clarified by six database annotations, especially GO classification, KEGG pathways, and COG terms. Unlike the minor ratio of “cellular component” (28.38%) in previous transcriptome analysis in M. alternatus GO annotation (Wu et al., 2016), this category (45.92%) was predominant in our study, which implied that most of the cells required being repaired after heat stress (Howard et al., 2011; Li et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017). In addition, more KEGG pathways and COG terms related to protein activity and signal transduction were also different from transcriptome data of this beetle treated with insecticide, which all suggested that stress-response mechanisms were diverse in M. alternatus.

GO enrichment analysis allowed us to effectively identify critical biological processes that were associated with heat stress response. After heat exposure, top two highly enriched GO terms of “protein folding” and “unfold protein binding” in M. alternatus provided evidence for the hypothesis that increasing temperature accelerated protein unfolding and initiated molecular chaperones (Day et al., 2002), similarly confirmed by enrichment of “Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum” pathways in KEGG analysis. Supposed by enrichment in the “Antigen processing and presentation” pathway, M. alternatus might struggle with heat stress by immune response. Transcriptome sequencing in B. mori revealed that “longevity regulating pathway–multiple species” pathway was involved in diapause preparation (Chen et al., 2017), whereas this pathway contributed to heat tolerance in our research. The enrichment of the “MAPK signaling pathway” suggested that environmental stress could motivate a signal switch for M. alternatus. Enrichment of DEGs manifested that unigenes involved in protein activity, immune response, and signal transduction might be vital components of M. alternatus heat-response mechanism. Further analysis of DEGs certified this hypothesis and provided new insights for this mechanism as well.

Metabolizable energy was essential for the maintenance of homeostasis and growth (Richard, 1986). Thermal stress above the optimal temperature harmed the insect’s energy reserves and metabolism (Belhadj et al., 2015). When insects were faced with heat stress, the synthesis of most proteins declines, including those of ATPases participating in three primary metabolisms: glycolytic pathway, tricarboxylic acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation. Our analysis of DEGs revealed that many genes related to metabolic processes were repressed. The situation was similar in G. pyloalis exposed to 25 and 40°C (Liu et al., 2017). Due to the inhibition of metabolism, protein degradation could be produced when organisms were exposed to heat shock. Heat treatment could induce protein flour hydrolyzates degradation in Locusta migratoria and produce low-molecular-weight protein (Purschke et al., 2017). Therefore, some genes performing a function in the removal of damaged proteins would be elicited to maintain cellular structures and activities. The ubiquitin proteolytic system (UPS) had a significant cytoprotective role in degrading damaged proteins (Plafker, 2010). In our study, 15 ubiquitin-related unigenes of M. alternatus were upregulated after heat exposure. The results indicated that the UPS could get rid of damaged proteins during insect heat stress.

Similar to ubiquitin, a group of highly conserved proteins, HSPs, could function as molecular chaperones to protect proteins from misfolding and denaturation under heat stress (Montfort et al., 2001; Sun and MacRae, 2005; King and Macrae, 2015). The HSPs were widely distributed in microorganisms, plants, and animals. The large HSP superfamily was commonly classified into several families based on their molecular weight and homologous relationship, including HSP100, HSP90, HSP70, HSP60, HSP40, and HSP20 (Garrido et al., 2012). Since firstly discovered in D. melanogaster larvae, HSPs in many insects have already been identified as heat stress-related factors (Ritossa, 1962; Quan et al., 2017; Guo and Feng, 2018; Wang et al., 2019). In the current study, 15 HSPs were upregulated by heat treatment in M. alternatus. Four HSP20, known as ATP-independent chaperons of M. alternatus, were also induced by heat stress. Function in the first line of cell defense against heat stress, most HSP20 displayed activities in helping the unfolding proteins maintain their correct states, binding to denatured proteins and preventing irreversible protein aggregation when metabolism inhibited (Basha et al., 2012). Interaction between sHsps and Hsp70 is fundamental to the HSP network (King and Macrae, 2015). Hsp70 could remove substrates from sHsps and participates in refolding and degradation, either acting alone or with other HSPs, while this process depends on the energy supplied by the ATPase activity of HSP70. Gene number and expression level of HSP70 were dominant in the induced HSPs, which manifested that HSP70 was the most prominent contributor to thermotolerance in M. alternatus. This finding was consistent with the earlier study by Chen et al. (2014) in Grapholita molesta and Zhang and Denlinger (2010) in Helicoverpa zea. Besides, two HSP90 and an HSP40 were involved in M. alternatus heat resistance. HSP90, having similar roles to those of HSP70, could bind a substrate when in an open conformation, but sequestering of proteins is unlikely when ATP is not restrictive, whereas HSP40 could promote substrate binding to HSP70 and enhance ATP hydrolysis to regulate HSP70 activity (Minami et al., 1996; Yonehara et al., 1996). All these results suggested that HSP20, HSP70, and HSP90, in association with HSP40, formed complex molecular networks to boost protein folding and protect cellular proteins from damage in insects.

It was notable that previous studies have certified that HSPs could act as a regulator of immune response (Mehlen et al., 1996; Ravagnan et al., 2001). When blocking HSP70 with special antibody, the production of immune activity (TNF-α released from macrophages) decreased and mammalian HSPs could bind with antigenic peptides (Udono, 1993; Zhou et al., 2018). Therefore, the immune system might be raised by HSPs to cope with heat stress together in M. alternatus. In expectation, many unigenes involved in immune response, such as “antigen processing and presentation,” “apoptosis” and “lysozymes,” were exactly induced in the current study. In addition, the homeostasis between cell proliferation and apoptosis were essential for insect survival, while heat stress could activate the excessive occurrence of organisms apoptosis (Takayama et al., 2003; Cui et al., 2016). Practically, the insect immune system was the major effector system to regulate apoptosis. “Antigen processing and presentation” and “lysozymes” were suggested to play a role in the body defense against infection, whereas heat stress might increase disease and impaired longevity; thus, the induction of these genes also certified that the immune response might be evoked directly by heat stress.

In addition to metabolism inhibition and protein degradation, high temperatures could cause oxidative damage, elevating intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that undermined cellular environmental homeostasis and biological functions of some proteins (Monaghan et al., 2009). To prevent damage from ROS, insects have evolved antioxidant defense mechanisms. SOD was the most important antioxidant enzymes in the enzyme defense system against ROS. SOD catalyzed the disputation of superoxide radicals into oxygen (O2) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2); then H2O2 was converted by other antioxidant enzymes (catalase and peroxidases) into oxygen and water (H2O) (Kang et al., 2017). A previous study found that not only the activity of SOD but also the transcriptional expression of SOD encoding genes were increased significantly when exposed to high temperatures, and the deletion of the SOD gene could produce heat susceptible rice (Pirillo et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017). We detected the upregulation of two SOD genes in the 40°C-treatment M. alternatus larvae as well, which revealed that SOD contributed to the ROS-scavenging system in M. alternatus during heat stress.

Heat stress can induce the production of toxic substances other than oxidative damage. Antioxidant and detoxification mechanisms could work together to cope with heat stress. CYPs catalyzed a broad range of oxidative substances, including insecticides, plant secondary metabolites, and some oxidative substances induced by heat exposure (Daborn et al., 2007; Niu et al., 2011). In the present study, upregulation of CYPs in M. alternatus, similar to other organisms treated with heat stress, certified this role of CYPs (Liu et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2017). In addition to CYPs, organisms produced ALDHs in response to a suite of environmental stresses that perturb metabolism, including salinity, dehydration, desiccation, and cold and heat shock (Kirch et al., 2004). The increased expression of genes related to detoxification in M. alternatus suggested that CYPs and ALDHs were critical in the oxidative processes derived from heat stress.

Stress-responsive signal transduction pathways could connect the environmental stress with the organism to induce most of these defensive reactions described above (Kawasaki et al., 2002; Ludwig et al., 2005). Sensing the stress signals and transmitting them to cellular machinery to activate adaptive responses are referred to as stress signal transduction (Kawasaki et al., 2002). When suffering from heat stress, organisms could activate various stress-responsive signal transduction pathways, such as PI, Notch, MAPK, Hippo, and JAK-STAT signaling pathways. P38A-MAPK pathways could be activated by diverse stress in mice (Bassi et al., 2014). The activated MAPK could trigger additional signal components to regulate gene expression, cytoskeleton-associated proteins, or enzyme activities, or target certain signal proteins for degradation (Xiong and Zhu, 2001). Therefore the upregulation of heat-responsive genes, including UPS, HSPs, SOD, and CYPs, might be activated by MAPK pathways in M. alternatus. JAK-STAT had an important role in the control of immune response, and dysregulation of this signaling was associated with various immune disorders (Shuai and Liu, 2003). Hippo signaling pathway as a central mechanism that regulated tissue homeostasis in species spanning from Drosophila to mammals and the dysregulation of Hippo signaling underlies various human diseases (Pan, 2010). The upregulation of these two pathways related to immune response indicated that signal pathways might also pose an immune response in M. alternatus. Thus, the stress signaling transduction might be central convergence points in M. alternatus heat tolerance mechanism.

The heat tolerance mechanism of M. alternatus was complicated and involved lots of genes and pathways. M. alternatus could perceive stress signals by MAPK, Hippo, and JAK-STAT signaling pathways and activate heat shock response. UPS and HSPs could protect protein misfolding and get rid of damaging proteins produced by abnormal metabolism and superabundant ROS. Immune response could be either raised by HSPs or induced directly by stress to contribute to this process. In addition, antioxidant and detoxification mechanisms could cooperate to deal with oxidative damage.

Conclusion

Here, we determined the Ltem50 of M. alternatus larvae by bioassay to confirm its heat resistance. A total of 63,360 unigenes were obtained, and 806 DEGs were identified in M. alternatus after heat stress by RNA-seq. The GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis indicated that DEGs participated in the “protein unfolding” and “binding,” “immune response,” and “signal transduction” pathways. Further analysis of 545 upregulated and 261 downregulated DEGs revealed that genes related to metabolism, UPS, HSPs, antioxidants, detoxification, immune response, and signal transduction might work together to defend heat stress in M. alternatus, which could be confirmed via more in-depth functional verification experiments. In conclusion, our study provides new insights into the tolerant events underlying heat resistance in M. alternatus and other insects, which could contribute to exploring the function of heat resistance-related genes.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA548205.

Ethics Statement

There was no requirement to seek ethical approval to carry out the work described above. However, the use of insects in the above experiments was kept to a minimum.

Author Contributions

HL conceived and designed the experiments. HL, XZ, HQ, XH, and JT performed the experiments. HL and DH wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Shouyin Li, Ruixu Chen, and Cong Chen of Nanjing Forestry University for assistance with our experiments.

Funding. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC1200400), Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX19-1083), and National Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. 31170606 and 31470650.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2019.01568/full#supplementary-material

References

- Bale J. S., Masters G. J., Hodkinson I. D., Awmack C., Bezemer T. M., Brown V. K. (2002). Herbivory in global climate change research: direct effects of rising temperature on insect herbivores. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 8 1–16. 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2002.00451.x 22928417 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basha E., O’Neill H., Vierling E. (2012). Small heat shock proteins and α-crystallins: dynamic proteins with flexible functions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 37 106–117. 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi R., Rudyk O., Burgoyne J., Eaton P., Marber M. S. (2014). 3 can redox-sensitive cysteines in P38A-MAPK modulate activation during stress? Heart 100(Suppl. 1), 3–12. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-305297.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belhadj S. I., Najar T., Ghram A., Abdrrabba M. (2015). Heat stress effects on livestock: molecular, cellular and metabolic aspects, a review. J. Anim. Physiol. A Anim. Nutr. 100 401–412. 10.1111/jpn.12379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z., Chen J., Cheng J., Lin T. (2017). Overexpression of three heat shock proteins protects Monochamus alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) from thermal stress. J. Insect Sci. 17 1–17. 10.1093/jisesa/iex08228082349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. H., Zheng Y. J., Zhong Y. D., Wu Y. F., Li Z. T., Xu L. A., et al. (2018). Transcriptome analysis and identification of genes related to terpenoid biosynthesis in Cinnamomum camphora. BMC Genomics 19 550–565. 10.1186/s12864-018-4941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Xu X., Li Y., Wu J. (2014). Characterization of heat shock protein 90, 70 and their transcriptional expression patterns on high temperature in adult of Grapholita molesta (Busck). Insect Sci. 21 439–448. 10.1111/1744-7917.12057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R. X., Wang L. J., Lin T., Wei Z. Q., Wang Y., Hao D. J. (2017). Rearing techniques of Monochamus alternatus Hope (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) on artificial diets. J. Nanjing For. University 41 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. R., Jiang T., Zhu J., Xie Y. C., Tan Z. C., Chen Y. H., et al. (2017). Transcriptome sequencing reveals potential mechanisms of diapause preparation in bivoltine silkworm, Bombyx mori, (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D Genomics Proteomics. 24 68–78. 10.1016/j.cbd.2017.07.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colinet H., Overgaard J., Com E., Sørensen J. G. (2013). Proteomic profiling of thermal acclimation in Drosophila Melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43 352–365. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2013.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Hao Y., Li J., Bao W., Li G., Gao Y. (2016). Chronic heat stress induces immune response, oxidative stress response, and apoptosis of finishing pig liver: a proteomic approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17 393–417. 10.3390/ijms17050393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daborn P. J., Lumb C., Boey A., Wong W., Ffrench-Constant R. H., Batterham P. (2007). Evaluating the insecticide resistance potential of eight Drosophila melanogaster cytochrome P450 genes by transgenic overexpression. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37 512–519. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day R., Bennion B. J., Ham S., Daggett V. (2002). Increasing temperature accelerates protein unfolding without changing the pathway of unfolding. J. Mol. Biol. 322 189–203. 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00672-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon M. E., Wang G., Garrity P. A., Huey R. B. (2009). Thermal preference in Drosophila. J. Therm. Biol. 34 109–119. 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2008.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder M. E., Hofmann G. E. (1999). Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: evolutionary and ecological physiology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 61 243–282. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney D. J. (1971). Probit Analysis, 3rd Edn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ), 999–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Foottit R. G., Adler P. H. (2017). Insect Biodiversity (Science and Society) | | Insect Biodiversity Informatics. Hoboken: Wiley, 593–602. [Google Scholar]

- Garrad R., Booth D. T., Furlong M. J. (2016). The effect of rearing temperature on development, body size, energetics and fecundity of the diamondback moth. Biol. Entomol. RES. 1 1–7. 10.1017/S000748531500098X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido C., Paul C., Seigneuric R., Kampinga H. H. (2012). The small heat shock proteins family: the long forgotten chaperones. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 44 1588–1592. 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr M. G., Haas B. J., Yassour M., Levin J. Z., Thompson D. A., Amit I., et al. (2011). Full-length transcriptome assembly from rna-seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29 644–652. 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X. J., Feng J. N. (2018). Comparisons of expression levels of heat shock proteins (hsp70 and hsp90) from Anaphothrips obscurus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in Polymorphic adults exposed to different heat shock treatments. J. Insect Sci. 18 1–10. 10.1093/jisesa/iey059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B., Li Y. J., Ni Z. X., Xu L. A. (2017). Transcriptome sequencing and SNP detection in Phoebe chekiangensis. PeerJ 5:e3193 10.7717/peerj.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard A. C., Mcneil A. K., Mcneil P. L. (2011). Promotion of plasma membrane repair by vitamin E. Nat. Commun. 2 597–605. 10.1038/ncomms1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. J., Wu X. Q. (2018). Research progress on the mechanism of pine response to the infection of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Chin. Bull. Life Sci. 30 559–666. [Google Scholar]

- Huey R. B. (2002). Plants versus animals: do they deal with stress in different ways? Integr. Comp. Biol. 42 415–423. 10.1093/icb/42.3.415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing X. H., Kang L. (2004). Overview and evaluation of research methodology for insect cold hardiness. Entomol. Knowledge. 40 7–10. 10.1109/JLT.2003.821766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. A., Valero K. A., Wang S., Tang J. (2004). Thermal death kinetics of red flour beetle (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 97 1868–1873. 10.1603/0022-0493-97.6.1868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J. Y., Lee D. S., Park S. K., Jeong S. H., Jong M. K., Gi J. H., et al. (2017). Cognitive function of Artemisia argyi H. Fermented by Monascus purpureus under TMT-induced learning and memory deficits in ICR mice. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 3 1–16. 10.1155/2017/5809370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki L., Olivia S., Shiozaki K., Aguirre J. (2002). SakA MAP kinase is involved in stress signal transduction, sexual development and spore viability in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 45 1153–1163. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03087.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A. M., Macrae T. H. (2015). Insect heat shock proteins during stress and diapause. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 60 59–75. 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirch H. H., Bartels D., Wei Y., Schnable P. S., Wood A. J. (2004). The aldh gene superfamily of arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 9 371–377. 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhrt U., Samietz J., Dorn S. (2006). Plant architecture, hail nets and thermal behavior influencing developmental rate and modeling of the codling moth. Acta Hortic. 707:24 10.17660/ActaHortic.2006.707.24 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R. P., Bayne C. J., Camara M. D., Cunningham C., Jenny M. J., Langdon C. J. (2009). Transcriptome profiling of selectively bred Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas families that differ intolerance of heat shock. Mar. Biotechnol. 11 650–668. 10.1007/s10126-009-9181-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., He X. Y., Tao R., Gong X. Y., Chen H. J., Hao D. J. (2018). cDNA cloning and expression profiling of small heat shock protein genes and their response to temperature stress in Monochamus alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). Acta Entomol. Sin. 61 749–760. [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Ye L., Lan T., Yu M., Liang J., Zhong B. (2012). Comparative proteomic and phosphoproteomic analysis of the silkworm (Bombyx mori) posterior silk gland under high temperature treatment. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39 8447–8456. 10.1007/s11033-012-1698-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Xu X. W., Li Y., Wang H. M., Li Z. L., Li Z. X. (2015). Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals differential transcription in heat-susceptible and heat-tolerant pepper (Capsicum annum L.) cultivars under heat stress. J. Plant Biol. 58 411–424. 10.1007/s12374-015-0423-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. W. (2014). Tolerance to Temperature Stresses of Grey Tiger Longicorn Beetle (Xylotrechus rusticus L.) and Its Potential Range in China. Haidian: Beijing forestry university. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Wei Y., Xu L., Hao Y., Chen X., Zhou Z. (2017). Transcriptomic profiling reveals differentially expressed genes associated with pine wood nematode resistance in masson pine (Pinus massoniana lamb.). Sci. Rep. 7 4693–4707. 10.1038/s41598-017-04944-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Li A., Chen C., Cai G., Zhang L., Guo C., et al. (2018). De novo transcriptome sequencing in Passiflora edulis sims to identify genes and signaling pathways involved in cold tolerance. Forests 8 435–449. 10.3390/f8110435 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Su H., Li R., Li X., Xu Y., Dai X., et al. (2017). Comparative transcriptome analysis of Glyphodes pyloalis walker (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) reveals novel insights into heat stress tolerance in insects. BMC Genomics 18:974. 10.1186/s12864-017-4355-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-△△CT method. Methods 25 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü J. H., Liu S. (2017). Influence of acclimation to sublethal temperature on heat tolerance of Tribolium castaneum(Herbst) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) exposed to 50°C. PLoS One 12:e0182269. 10.1371/journal.pone.0182269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig A. A., Saitoh H., Felix G., Freymark G., Miersch O., Wasternack C., et al. (2005). Ethylene-mediated cross-talk between calcium-dependent protein kinase and mapk signaling controls stress responses in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 10736–10741. 10.1073/pnas.0502954102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamiya Y., Enda N. (1972). Bursaphelenchus mucronatus n. sp. (Nematoda: Aphelenchoididae) from pine wood and its biology and pathogenicity to pine trees. Nematologica 25 353–361. 10.1163/187529279X00091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlen P., Schulze-Osthoff K., Arrigo A. P. (1996). Small stress proteins as novel regulators of apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 271 16510–16514. 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami Y., Hohfeld J., Ohtsuka K., Hartl F. U. (1996). Regulation of the heat-shock protein 70 reaction cycle by the mammalian DnaJ homolog, Hsp40. J. Biol. Chem. 271 19617–19624. 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan P., Metcalfe N. B., Torres R. (2009). Oxidative stress as a mediator of life history trade-offs: mechanisms, measurements and interpretation. Ecol Lett. 12 75–92. 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01258.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montfort R. L. M., Slingsby C., Vierling E. (2001). Structure and function of the small heat shock protein/alpha-crystallin family of molecular chaperones. Adv. Protein Chem. 59 105–156. 10.1016/S0065-3233(01)59004-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu G., Rupasinghe S. G., Zangerl A. R., Siegel J. P., Schuler M. A., Berenbaum M. R. (2011). A substrate-specific cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, CYP6AB11, from the polyphagous navel orangeworm (Amyelois transitella). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 41 244–253. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2010.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata H., Goto S., Sato K., Fujibuchi W., Bono H., Kanehisa M. (2000). KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27 29–34. 10.1093/nar/28.1.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan D. (2010). The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev. Cell. 19 491–505. 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirillo S., Einschlag F. S. G., Ferreira M. L., Rueda E. H. (2010). Eriochrome blue black and fluorescein degradation by hydrogen peroxide oxidation with horseradish peroxidase and hematin as biocatalysts. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 66 63–71. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plafker S. M. (2010). Oxidative stress and the ubiquitin proteolytic system in age-related macular degeneration. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 664 447–456. 10.1007/978-1-4419-1399-9_51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purschke B., Meinlschmidt P., Horn C., Rieder O., Henry J. (2017). Improvement of techno-functional properties of edible insect protein from migratory locust by enzymatic hydrolysis. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 244 999–1013. 10.1007/s00217-017-3017-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quan G., Duan J., Ladd T., Krell P. J. (2017). Identification and expression analysis of multiple small heat shock protein genes in spruce budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana (L.). Cell Stress Chaperones 23 141–154. 10.1007/s12192-017-0832-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravagnan L., Gurbuxani S., Susin S. A., Maisse C., Daugas E., Zamzami N., et al. (2001). Heat-shock protein 70 antagonizes apoptosis-inducing factor. Nat. Cell Biol. 3 839–843. 10.1038/ncb0901-839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard D. (1986). Effects of ovarian hormones on energy balance and brown adipose tissue thermogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. 250:R245-9. 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.250.2.R245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Yan B. Y., Lou X. P., Ma H. S., Ruan S. L. (2017). Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals the transcriptional alterations in heat-resistant and heat-sensitive sweet maize (Zea mays L.) varieties under heat stress. BMC Plant Biol. 17:26. 10.1186/s12870-017-0973-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai K., Liu B. (2003). Regulation of JAK–STAT signalling in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3 900–911. 10.1038/nri1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., MacRae T. H. (2005). Small heat shock proteins: molecular structure and chaperone function. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62 2460–2476. 10.1007/s00018-005-5190-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama S., Reed J. C., Homma S. (2003). Heat-shock proteins as regulators of apoptosis. Oncogene 22 9041–9047. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Hendrickson D. G., Sauvageau M., Goff L., Rinn J. L., Pachter L. (2012). Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with rna-seq. Nat. Biotechnol. 31 46–53. 10.1038/nbt.2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udono H. (1993). Heat shock protein 70-associated peptides elicit specific cancer immunity. J. Exp. Med. 178 1391–1396. 10.1084/jem.178.4.1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Fang Y., Wang L., Zhu W., Ji H., Wang H., et al. (2014). Transcriptome analysis of theBombyx mori fat body after constant high temperature treatment shows differences between the sexes. Mol. Biol. Rep. 41 6039–6049. 10.1007/s11033-014-3481-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. R., Wang C., Ban F. X., Zhu D. T., Liu S. S., Wang X. W. (2019). Genome-wide identification and characterization of HSP gene superfamily in whitefly (Bemisia tabacl)and expression profiling analysis under temperature stress. Insect Sci. 1 44–57. 10.1111/1744-7917.12505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei D., Jia F. X., Tian C. B., Tian Y., Smagghe G., Dou W., et al. (2015). Comparative proteomic analysis of Bactrocera dorsalis (hendel) in response to thermal stress. J. Insect Physiol. 74 16–24. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2015.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Zhu X., Liu Z., Shao E., Zhang F. (2016). Identification of genes relevant to pesticides and biology from global transcriptome data of Monochamus alternatus Hope (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) larvae. PLoS One 11:e0147855. 10.1371/journal.pone.0147855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L., Zhu J.-K. (2001). Abiotic stress signal transduction in plants: molecular and genetic perspectives. Physiol. Plant 112 152–166. 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2001.1120202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Yu L., Xuan J. P., Lu Y., Lu S. J., Zhu W. M. (2016). De novo transcriptome sequencing and gene expression profiling of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) leaves under heat stress. Sci. Rep. 6:19473. 10.1038/srep19473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonehara M., Minami Y., Kawata Y., Nagai J., Yahara I. (1996). Heat-induced chaperone activity of HSP90. J. Biol. Chem. 271 2641–2645. 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Denlinger D. L. (2010). Molecular characterization of heat shock protein 90, 70 and 70 cognate cDNAs and their expression patterns during thermal stress and pupal diapause in the corn earworm. J. Insect Physiol. 56 138–150. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2009.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Chang X. Q., Hoffmann A. A., Zhang S., Ma C. S. (2015). Impact of hot events at different developmental stages of a moth: the closer to adult stage, the less reproductive output. Sci. Rep. 5:10436. 10.1038/srep10436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. H., Wu H. S., Xie J. Q., Jiang R. X., Deng C. S., Pang H. (2015). Transcriptome responses to heat- and cold-stress in ladybirds (Cryptolaemus montrouzieri Mulasnt) analyzed by deep-sequencing. Biol Res. 48:66. 10.1186/s40659-015-0054-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Yu H. Y., Zhang W., Ahmad F., Hu S. N., Zhao L. L., et al. (2018). Comparative analysis of the Monochamus alternatus immune system. Insect Sci. 25 581–603. 10.1111/1744-7917.12453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA548205.