Abstract

The HSRA rat is a model of congenital abnormalities of the kidney and urogenital tract (CAKUT). Our laboratory has used this model to investigate the role of nephron number (functional unit of the kidney) in susceptibility to develop kidney disease as 50–75% offspring are born with a single kidney (HSRA-S), while 25–50% are born with two kidneys (HSRA-C). HSRA-S rats develop increased kidney injury and hypertension with age compared with nephrectomized two-kidney animals (HSRA-UNX), suggesting that even slight differences in nephron number can be an important driver in decline in kidney function. The HSRA rat was selected and inbred from a family of outbred heterogeneous stock (NIH-HS) rats that exhibited a high incidence of CAKUT. The HS model was originally developed from eight inbred strains (ACI, BN, BUF, F344, M520, MR, WKY, and WN). The genetic make-up of the HSRA is therefore a mosaic of these eight inbred strains. Interestingly, the ACI progenitor of the HS model exhibits CAKUT in 10–15% of offspring with the genetic cause being attributed to the presence of a long-term repeat (LTR) within exon 1 of the c-Kit gene. Our hypothesis is that the HSRA and ACI share this common genetic cause, but other alleles in the HSRA genome contribute to the increased penetrance of CAKUT (75% HSRA vs. 15% in ACI). To facilitate genetic studies and better characterize the model, we sequenced the whole genome of the HSRA to a depth of ~50×. A genome-wide variant analysis of high-impact variants identified a number of novel genes that could be linked to CAKUT in the HSRA model. In summary, the identification of new genes/modifiers that lead to CAKUT/loss of one kidney in the HSRA model will provide greater insight into association between kidney development and susceptibility to develop cardiovascular disease later in life.

Keywords: genetics, kidney development, kidney disease, mitochondria, solitary kidney

INTRODUCTION

There are more than 40 syndromes that are considered congenital abnormalities of the kidney and urogenital tract (CAKUT) that range from benign malformation of the urogenital system to full failure of organ development (30). As a whole, CAKUT significantly increases the risk of kidney failure in childhood as well as predisposing individuals to future disease, including hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD) (26, 74). In particular, congenital solitary kidney is a relatively common abnormality of the urogenital tract of both males and females. The March of Dimes estimates the frequency of these birth defects to be ~1 per 500 births (https://www.marchofdimes.org). This estimate is supported by several studies of three large populations, including Japanese (82), Taiwanese (80), and Chinese (46).

The fundamental unit of the kidney is the nephron, with the numbers of nephrons that compose each kidney being set at birth and only decline with age or confounding illness. Despite several studies demonstrating a strong inverse correlation between low/reduced nephron numbers and increased susceptibility to hypertension and CKD [reviewed in (52)], establishing a direct connection between nephron number and cardiovascular disease is confounded by the fact that nephron number varies significantly from person to person. Some investigators have shown a fourfold variation in nephron number (34, 62), while others have reported as much as 10-fold variation (5). In the context of CAKUT, the most drastic example of nephron deficiency is that of a person born with a single kidney. However, nephron deficiency can result from trauma (63, 81) as well as kidney donation (31). Based on studies involving these groups of patients, living with a single kidney is highly variable clinically, with some patients experiencing no complications, while others go on to develop kidney failure (85). Recent studies indicate that kidney donation predisposes patients to the development of end-stage renal disease and cardiovascular complications (31, 57). In addition, other studies have found that nephron number can be a predictor of renal function postkidney donation, with low nephron number being significantly correlated with development of long-term proteinuria (28). Unfortunately, a major limitation of investigating the role of nephron number in cardiovascular disease or diabetes in humans is the difficultly in accurately measuring nephron number noninvasively.

Given the potential role of nephron number to contribute to cardiovascular disease in humans, our laboratory employs a unique CAKUT animal model to investigate the role of nephron deficiency and CKD. The HSRA (Heterogeneous Stock-derived model of unilateral Renal Agenesis) rat is an inbred strain that consistently produces 50–75% offspring having a single kidney (HSRA-S), with the remaining pups born with two kidneys (HSRA-C). In addition to agenesis of one kidney, the kidney that does develop exhibits fewer nephrons compared with a single kidney from a control animal (87). Previous work demonstrated that HSRA-S rats develop increased kidney injury and hypertension with age (compared with HSRA-C) (87), but most striking is that they are highly susceptible to hypertension-induced kidney injury (DOCA/1% NaCl) compared with HSRA-C that have undergone uninephrectomy (HSRA-UNX) (86). This seemingly small difference in nephron number between the HSRA-S and HSRA-UNX suggests that slight reductions in nephron number can be an important driver of response to elevated blood pressure, hastening kidney injury and accelerating decline in kidney function.

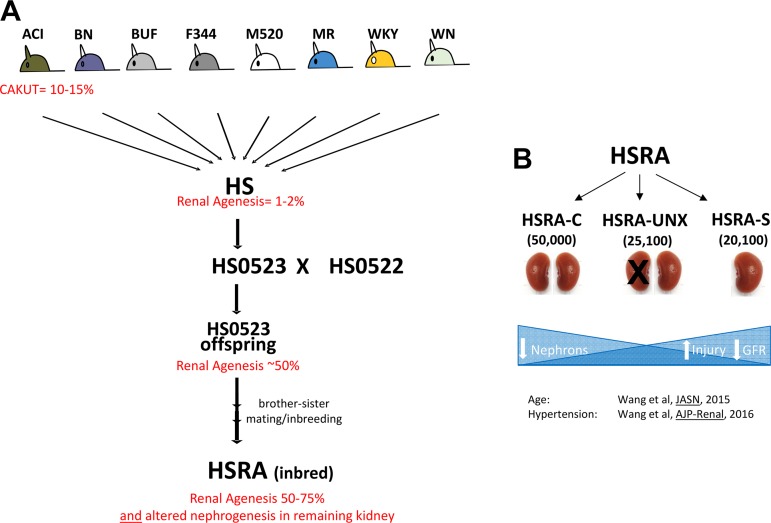

The HSRA rat is derived from the heterogeneous stock model (NIH-HS, denoted from here as HS) (Fig. 1). The HS outbred rat colony was created in 1984 by the National Institutes of Health as a source for genetically segregating animals (11). The HS model was developed via an eight-way cross of different inbred strains to yield a significant number of genetic combinations. The eight strains used for the creation of the HS population were BN/SsN, MR/N, BUF/N, M520/N, WN/N, ACI/N, WKY/N, and F344/N (11). As an outbred strain, the HS population has a range of phenotypes due to a diverse combination of genotypes, allowing for efficient fine-mapping of numerous complex traits (27, 77a, 78). In particular, the study of the HS population identified significant variability in several kidney-related phenotypes; most notable was the identification upon euthanasia of a rat possessing a single kidney (79) (Fig. 1). The parents of this rat were available and subsequently inbred (>20 generations of inbreeding) to establish the HSRA strain (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the origin of the HSRA rat. A: the NIH-HS model was developed via random breeding paradigm to produce the HS rat populations. The incidence of renal agenesis in the HS population is <2%. The ACI strain has a penetrance of 10–15% for the renal agenesis phenotype. The cross between the HS0523 and HS0522 rats resulted in offspring exhibiting >60% penetrance of renal agenesis. These offspring were inbred by brother-sister mating to produce the inbred strain HSRA described in this study that exhibit renal agenesis penetrance of 50–75%. B: the HSRA characteristic reduction of nephron number (~20,000) in the single kidney phenotype as compared with the average number of nephrons (~25,000) in the kidneys in the HSRA individuals not displaying the single kidney phenotype. With decreasing nephron number, we have shown the HSRA to exhibit increased renal injury and decreased renal function, both with age and with superimposed hypertension. HS, heterogeneous stock; HSRA, heterogeneous stock-derived model of unilateral renal agenesis.

As the HSRA was developed from the HS model, which exhibits a defined genetic composition (eight inbred strains), it provides a unique opportunity to map the genetic architecture of the HSRA rat. Thus, a major focus of the current study was to perform whole genome sequencing (WGS) of the HSRA to map its genetic architecture with respect to the eight progenitor strains that compose the HS model. There were several other objectives, including: 1) query all known genes linked to CAKUT in both human and rodent models to determine if sequence variation in any of these genes underlies CAKUT in the HSRA rat, 2) identify potential novel candidate genes linked to CAKUT/nephron number by investigating all genes genome-wide with high-impact sequence variants, and 3) investigate whether the HSRA contains a long-term repeat (LTR) within exon 1 of c-Kit gene linked to CAKUT in the ACI progenitor (72). In summary, the WGS of the HSRA model provides an important first step in establishing the genetic architecture of the model as well as lays the groundwork for future genetic studies to identity gene/modifier that leads to loss of one kidney and nephron deficiency in the HSRA model. These finding will ultimately provide greater insight into link between kidney development and susceptibility to develop renal and/or cardiovascular disease later in life.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animals

All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The HSRA was developed from a single breeding pair of HS rats whose offspring demonstrated a high degree (>60%) of unilateral renal agenesis (79). Brother-sister mating was performed (>20 generations) to establish an inbred strain that demonstrates consistent unilateral renal agenesis in 50–75% of offspring (87). At 6 wk of age, kidney status was determined by abdominal palpation and later confirmed in experimental animals after euthanasia.

DNA Isolation and WGS

Genomic DNA was isolated from liver (30 mg) from male animals (n = 2) that exhibited the single kidney phenotype with Invitrogen Purelink DNA kit (Invitrogen). Samples that passed quality parameters (e.g., minimum concentration and size range) were used to develop the WGS library. Individual DNA samples were sheared to a size of 500–600 bp by a Covaris M220 Focused-ultrasonicator instrument. Sheared DNA samples were confirmed in the expected size range by using the Qiagen QIAxcel system. A total of 2 μg of the sheared DNA was used as input to construct the Illumina library with the TruSeq DNA PCR-Free kit (Illumina). Before sequencing the library was QC’d with the Qubit Fluorimeter and Qiagen QIAxcel system. The library was paired end-sequenced with NextSeq500 High Output Reagent Kits (300 cycle, PE150) on the Illumina NextSeq 500 platform (2 runs). Read quality was assessed with FastQC and Quack. Reads were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s (NCBI) under BioProject PRJNA574594 and Short Read Archive accession numbers SRR10233452 and SRR10233451, respectively.

Bioinformatics Analysis of WGS Data

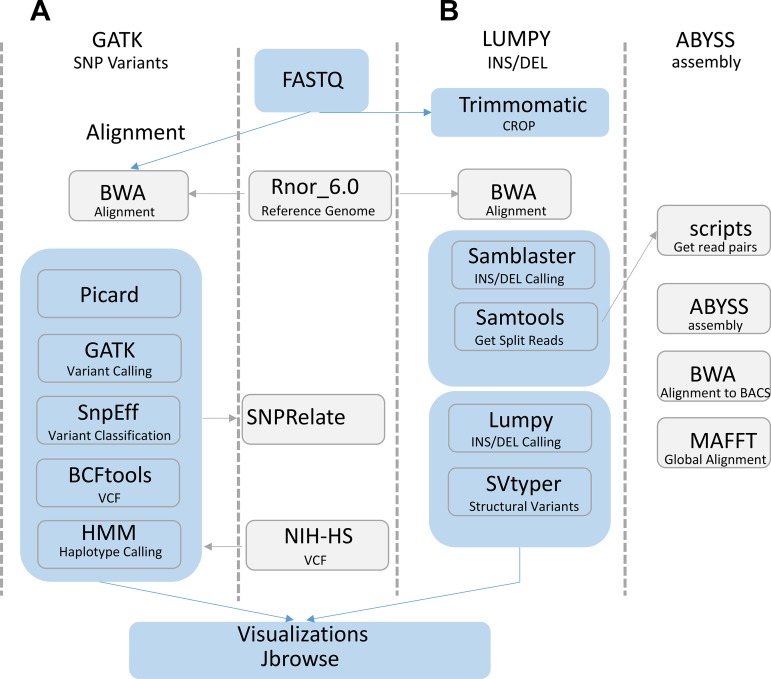

A summary of the bioinformatics analysis pipeline is provided in Fig. 2. A detailed description of the bioinformatics analysis is provided below.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the bioinformatics analysis of HSRA genome. A: the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) pipeline was followed. Reads were aligned to the Rat rn6 reference genome with Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA). The resultant alignments were marked for duplicates and base recalibrated with the Picard and GATK tools. GATK called the variants [single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), insertion/deletion (INDELS)] using the recalibrated bam files and a set of known SNPs (Ensembl release 86). The impact of the predicted variants was determined by the SNPeff program. The HSRA variants were combined with the NIH-HS eight strains data set with BCFtools and subsequently analyzed with SNPRelate and the hidden Markov model (HMM). B: additional variant calling was used to investigate the c-Kit genome region. First the reads were trimmed to a minimum length of 140 bp with Trimmomatic and aligned to the reference genome with BWA. BWA alignments were processed with the LUMPY workflow by the exclusion of duplicate reads and addition of mate tags prior to the identification of split reads with SAMblaster and SAMtools, respectively. The processed alignments used to predict the variants with LUMPY genotypes were assigned with SVtyper. Additionally, custom scripts were used to extract read pairs that contained a split read alignment near the previously reported kit intron 1 insertion. The read pairs were assembled with ABySS and subsequently compared with the reference genome (BN) as well as the BAC segments (ACI, F344) that also span the previously reported insertion.

Genotyping and functional analysis of the HSRA variants.

Reads were aligned to the rat genome (86 ENSEMBL release, version 6.0.86) with Burrows-Wheeler Aligner-superMaximal Exact Matches (BWA-MEM) [version 0.7.17 (44)] using default parameters, and the resulting alignments were merged with SAMtools [version 1.9 (45)]. Read depth was empirically measured in silico by creating a bedgraph for all bases with BEDtools [version 2.27.1 (69)] and analyzing it in the python (version 3.6.2) package pandas [version 0.25.0 (54)]. In silico measure of library insert size was calculated with the Picard program CollectInsertSizeMetrics from the aligned reads.

Variants were called with Genome Analysis Toolkit [GATK, version 4.1.0.0 (53)], following the best practices and protocols for calling and genotyping of reference bases (17, 53). Specifically, read duplications were identified and marked with the Picard MarkDuplicates (version 2.18.14, https://github.com/broadinstitute/picard) program and a base recalibration model was produced, using the ENSEMBL 86 Rat SNPs database as previously identified variants, and applied with the GATK programs BaseRecalibrator and ApplyBQSR, respectively. Using the aspirate level of ploidy for the chromosomes in our sample (i.e., autosomes and unplaced contigs n = 2; X, Y, MT n = 1) we assigned the GATK HaplotypeCaller program called variants and genotypes with the GATK GenotypeGVCFs program (using the “–include-non-variant-sites” parameter in the GenotypeGVCFs program). Variants as well as assigned reference genotypes with a depth <10 were filtered out with GATK VariantFiltration program. Mitochondria genotype calls predicted with the GATK HaplotypeCaller were confirmed by calling variants independently on the Mitochondria with the GATK Mutect2 program (13). Functional impact of the GATK-predicted variants was investigated with SNPeff [version 4.3 (14)] and summarized with SNPsift (13a).

The R Bioconductor package biomart (21, 22) was used to obtain gene annotations [including PFAM (23), INTERPRO (56), GO (1), transmembrane domain (tmhmm) (37), signal peptide (66), and ncoils (51)] for genes containing high-impact variants calls with three or fewer strains. Genes reported to cause CAKUT (83) were mapped to the Rat GENEIDs with the Bioconductor Package Biomart and subsequently investigated for functional impactful polymorphisms. Additionally, to identify candidate genes that could be linked to CAKUT, genes exhibiting high-impact variants were queried. Genes were excluded if no complete genotype data were available across the eight founder strains or there were heterozygous calls (i.e., only homozygous genotype calls were included).

Comparative genomics with the eight HS founder strains.

Variants form the eight HS founder lines were downloaded from links found at https://github.com/shwetaramdas/maskfiles/ (70). Variant calls for the Y chromosome in the eight HS founder lines were removed with BCFtools [version 1.9 (60)] and not used in any analysis as Ramdas et al. 2019 (70) sequenced and genotyped female rats. For compatibility with the Ramdas 2019 et al. data set, HRSA basecalls for the X chromosomes were converted from the haploid calls to diploid calls with the program VCFFilterJS (48). The resulting founder variants and HSRA diploid classified chromosomes were merged and filtered to include only biallelic homozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), as all strains in this study are inbred. A principal component analysis (PCA) plot of the diploid classified chromosomes was generated with the Bioconductor package SNPrelate (91).

A hidden Markov model (HMM), where the hidden states are the founder haplotypes and the observed data are the SNPs, adapted from Mott et al. 2000 (58), was applied to the merged and filtered biallelic homozygous SNPs for the diploid classified chromosomes to create a haplotype mosaic of the HSRA from the eight HS founders. Homozygous SNPs with called genotypes in all the samples were converted to the Hapmap (hmp) format with TASSEL [version 5.0 (8)] and used as input into the HMM. The homozygous SNP genetic distances were estimated by linear interpolation of the previously described sex averaged genetic map described by Littrell et al. 2018 (49) with the approx linear interpolation function in R. The smaller the genetic distance, the smaller the prior probability of founder state transition. The goal of the HMM is to compute the maximum posterior probability {}, where is the probability of the progeny i at SNP locus s descended from founder f. Resulting HMM values for founders with the highest probability above twofold chance (2/8th) (i.e., 1/8*2 = 0.25) were considered significant. To assess the totality of the genomic regions assigned by the HMM the HMM values were linearly interpolated across the chromosomes using the “approx linear interpolation” function in R. The interpolated values were analyzed with the python package pandas, and significant bases were converted to a BEDfile. Positions of continuous significant assignments to each specific strain were merged into blocks with the BEDTools merge function. Visualizations of the haplotype mosaic genome segments of the HSRA rat were created with Circos [version 0.69.3 (38)].

Mitochondria variants in the Ramdas et. al. 2019 (70) data set were phylogenetically analyzed by the conversion of the HS stains haploid calls in the VCF to diploid calls by assigning the highest allele frequency, as the diploid call at that position. Additionally, SNP positions that met two criteria, 1) genotype call for each of the eight HS strains and the HSRA and 2) at least 1 variant among the eight strains, were converted to nucleotide bases as a FASTA format pseudomolecule (limited to sites with variation) for analysis in MEGA X (39). A phylogenetic tree was created for the mitochondria pseudomolecule by an unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) (77) method, and evolutionary distances were computed using the p-distance in MEGA X software. The node branch support values were determined with 1,000 bootstraps replications.

LUMPY.

Additional INDEL variant calling for the HSRA was conducted with the LUMPY variant calling software [version 0.2.13 (43)]. LUMPY analysis was conducted by first cropping the reads to a standard length of 140 bp with Trimmomatic [version 0.36 (6)]. The reads were then aligned to the rat reference genome with BWA and parsed with SAMBLASTER [version 0.1.24 (24)]. Split reads were then extracted from the alignments with the LUMPY script extractSplitReads_BWA-MEM. Additionally, discordant reads were parsed with SAMtools, and the insertion distribution was determined with the LUMPY python script pairend_distro.py. Structural variants were identified with the LUMPY program. Genotypes for the LUMPY structural variants were determined with SVTyper [version 0.2.13 (12)]. For comparative purposes the eight HS strains raw reads were aligned to the rn6 reference genome with BWA and subsequently parsed with the LUMPY extractSplitReads_BwaMem script. Resultant alignments were visualized with JBROWSE [version 1.16.5 (9)].

Local assembly of the INDEL in c-Kit and ACI bacterial artificial chromosome library comparison.

Read pairs with at least one read flagged as a split read alignment near the c-Kit intron 1 insert (14:35,127,000–35,128,000) by the LUMPY program were identified with SAMtools and custom scripts and then assembled with ABySS (version 2.1.1 (29)]. The resultant assembled contigs were aligned to the rat reference genome (rn6) with BWA; the contig that aligned to both sides of the inspected insert with a region of unaligned bases between the tandem ends was considered for further analysis. The unordered bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) libraries ACI BAC (ACC# AP012486.1) and F344 BAC (ACC# AP012487.1.1) scaffold pseudomolecules were downloaded from NCBI and then broken into contigs with the perl program split.scaffolds.to.contigs.pl. The ACI BAC and F344 BAC contigs was then aligned to the assembled HSRA contig with BWA. The longest resultant BAC contig (ACI, 25,504 bp) was then aligned to the BN reference genome (rn6) to determine the maximum range of chromosome 14 to analyze (14: 35108107–35133612) and extracted with the SAMtools faidx program for comparison. Subsequently, regions of interest, HSRA, ACI BAC, F344 BAC contigs, as well as the reference genome region were aligned with MAFFT [version 7.429 (32)]and visualized with MEGA X.

Bioinformatics code.

Bioinformatics code, data sets, and software used to complete the analysis described in this manuscript can be found in the supplementary documents at URL: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10321298.

RESULTS

WGS, Genotyping, and Variant Classification

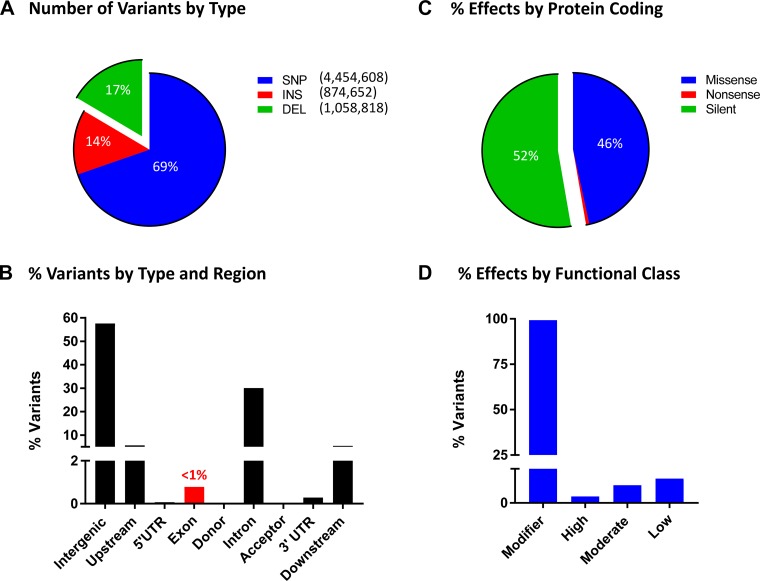

Illumina sequencing resulted in over one billion reads (152 Gbp) and a theoretical coverage of 55×. In total, 93.58% of the reads aligned to the genome, with an average depth of coverage of 47.3×. GATK variant calling resulted in 6,388,078 variants for the HSRA rat, of which 4,454,608 were SNPs, 874,652 were insertions and 1,058,818 were deletions (Fig. 3A). The majority of the variants were called as homozygous (n = 5,370,046) as opposed to heterozygous (n = 1,006,284). The GATK resulted in 2,361,582,221 reference base calls in which the HSRA genotype was the same as the reference sequence. In total 82% of the genome was called as either a variant or reference allele and available for downstream modeling.

Fig. 3.

Summary of HSRA variant types and location. A: percent of HSRA variants by variant type including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertion (INS), and deletion (DEL). B: the location of the variants by each gene regions. Less than 1% (0.8%) of the predicted variants were located within an exon region, while 30.1% of the variants were located within an intronic region. UTR, untranslated region. C: the SNP variant effect on protein coding. The majority were either silent (52.8%) or missense (46.6%), while only 0.7% were nonsense mutation. D: the SNPeff distribution of assigned functional class, most variants were placed in the modifier impact (a generic class of variant effect) in total <1% of the variants had a functional impact of high, low, or moderate.

As expected, the majority of the variants were observed to be in the intergenic region, followed by the introns, with less than 1% of the variants occurring within the exons (Fig. 3B). Of those variants that mapped within the coding regions, 52% were classified as synonymous/silent and 46% were missense variants (Fig. 3C). The overwhelming majority of variants were classified as “modifier” as were noncoding variants or variants affecting noncoding genes mapping with the intergenic region (Fig. 3D). The remainder of the variants (<1%) were classified as low (e.g., synonymous), moderate (e.g., missense), or high impact variants (e.g., stop gained and frameshift variant).

Comparative Sequence Analysis with the Eight HS Founder Strains

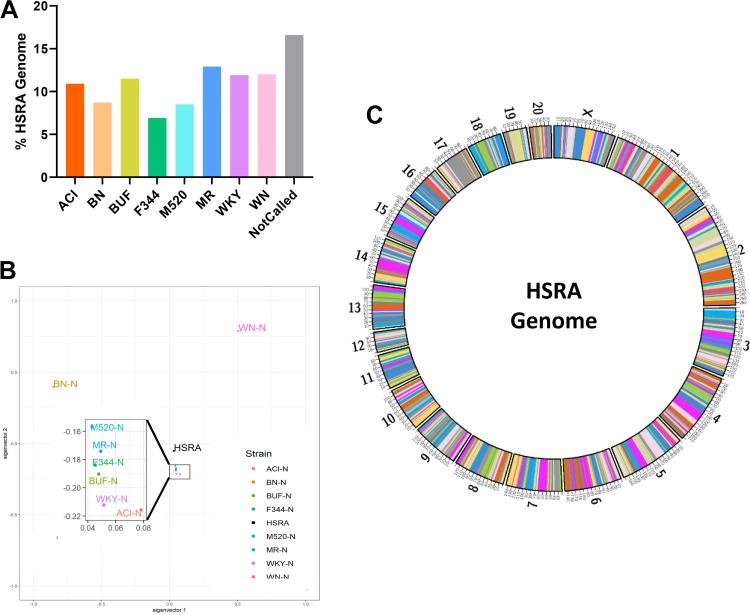

In total, 6,802,632 homozygous SNPs genotypes (either homozygous for reference or alternative) were shared between the HSRA genome and the eight HS founder strains reported by Ramdas et al. (70). Using an HMM, we assigned 2,316,391,512 bps (83.36%) of the HSRA genome to a specific founder strain. The average contribution of each inbred genome to the HSRA was 10.4 ± 0.74%, with the lowest contribution from F344 (6.9%) and largest contribution from WN (Fig. 4A). A PCA plot found that the HSRA rat demonstrated a central location compared with all the founder strains (indicative of it being a mosaic of all eight strains), with six of the founders more closely genetically related compared with the BN and WN (Fig. 4B). As expected, the haplotype regions (average size 3.1 Mb) originating from each strain were randomly distributed throughout the HSRA genome, resulting in the genome-wide mosaic of the founder strains (Fig. 4C). For example, a high-resolution chromosome view (Fig. 5) of chromosome 2 illustrates regions with high probability calls for each founder strain, as well as sharply defined recombination intervals.

Fig. 4.

HSRA genome composition and relatedness to the HS founder strains. A: the percentage of bases of each strain assigned to the HSRA genome by the HMM. The strain with the highest probability was assigned, bases with less than a 25% probability of being assigned to a founder were assigned to the “Not Called” group. B: principal component analysis (PCA) plot using sequence data from autosomal chromosomes was produced by SNPrelate. C: haplotype mosaic of the HSRA genome showing the assignments of founder strains across the HSRA chromosomes.

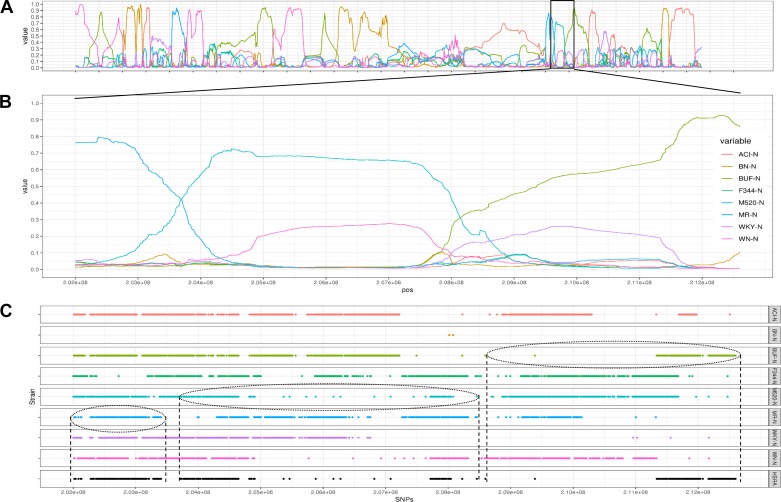

Fig. 5.

High-resolution chromosome view of chromosome 2. A: HMM posterior probabilities for each of the founder strains for entire chromosome 2. B: HMM posterior probabilities of founder of chromosome 2 position 20,200,0000–212,600,000. C: single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) shared by 2 of the 9 strains (HSRA and 8 HS founder strains) are displayed (this subset of SNPs was selected for visual clarity). The vertical dashed lines denote haplotype/recombination intervals.

Known Genes and Novel Candidate Genes Involved in CAKUT

Of the 42 known genes linked to CAKUT in humans, five genes contained high impact variants in the HSRA (Table 1). However, for these five genes, the high impact variants were mostly shared between the HSRA and all eight HS founder strains. To perform a genome-wide search for genes that could be associated with CAKUT/altered kidney development in the HSRA, we compared genes with high impact variants by the number of shared alleles between founders and HSRA. In total, 228 genes demonstrated high impact variants that had the potential to cause a protein truncation, loss of function, or trigger nonsense mediated decay (Supplemental Table S1; https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10321298). Of these, 78% of the high impact calls were shared between three to seven of the founders and the HSRA, suggesting that these were more common variants. In contrast, only 22% of the variant calls were either unique to one strain or shared between two founders and the HSRA, suggesting these variants were more rare and perhaps more likely to be associated with the CAKUT trait. Table 2 provides a detailed description of these genes, shared alleles between the eight founders, predicted impact, and evidence of urogenital and/or kidney expression. There were a number of genes with evidence of urogenital expression as well as demonstrate expression to specific regions of the kidney (glomerulus, tubules, or both) (Table 2). For example, high impact variants were identified in several genes involved in urogenital/kidney development, Frs2 (HSRA = BUF/N = WKY/N) and Hoxc5 (HSRA = BUF/N = MR), as well as Rhpj (HSRA = WN/N), a gene involved in cell division and communication between adjacent cells.

Table 1.

Genes linked to CAKUT in humans

| Gene | Gene Name |

|---|---|

| Autosomal recessive | |

| Ace | Angiotensin I-converting enzyme |

| Agt | Angiotensinogen |

| Agtr1 | Angiotensin II receptor, type 1 |

| Chrm3 | Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M3 |

| Fras1 | ECM protein FRAS1 |

| Frem1 | FRAS1-related ECM protein 1 |

| Frem2 | FRAS1-related ECM protein 2 |

| Grip1 | Glutamate receptor interacting protein 1 |

| Hpse2 | Heparanase 2 |

| Itga8 | Integrin-a8 |

| Lrig2 | Leucine-rich repeats and Ig-like domains 2 |

| Ren | Renin |

| Trap1 | Heat shock protein 75 (also known as TNF receptor–associated protein 1) |

| Autosomal dominant | |

| Bmp4 | Bone morphogenic protein 4 |

| Chd1L | Chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 1 like |

| Crkl | CRK-like proto-oncogene, adaptor protein |

| Dstyk | Dual serine/threonine and tyrosine protein kinase |

| Eya1 | Eyes absent homolog 1 |

| Gata3 | GATA binding protein 3 |

| Hnf1B | HNF homeobox B |

| Muc1 | Mucin 1 |

| Nrip1 | Nuclear receptor interacting protein 1 |

| Pax2 | Paired box 2 |

| Pbx1 | Pbx homeobox 1 |

| Ret | Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase receptor Ret |

| Robo2 | Roundabout, axon guidance receptor, homolog 2 (Drosophila) |

| Sall1 | Sal-like protein 1 (also known as spalt-like transcription factor 1) |

| Six2 | Six homeobox 2 |

| Six5 | Six homeobox 5 |

| Slit2 | Slit homolog 2 |

| Sox17 | Transcription factor SIX-17 |

| Srgap1 | Slit-Robo Rho GTPase activating protein 1 |

| Tbx18 | T-box transcription factor TBX18 |

| Tnxb | Tenascin XB |

| Umod | Uromodulin |

| Upk3A | Uroplakin 3A |

| Wnt4 | Protein Wnt-4 |

| Additional Genes | |

| Greb1l | GREB1-Like Retinoic Acid Receptor Coactivator |

| Foxp1 | Forkhead Box P1 |

Genes highlighted in boldface were observed to demonstrate high impact variant calls in the HSRA strain. However, all these high impact calls were also exhibited across all the other progenitor inbred strains used to develop the HS model.

Table 2.

Genes in the HSRA that exhibit high impact variant calls and shared between 1 or 2 HS founder strains

| HS Progenitors Strains |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shared Allele | Chr | Position | Gene Name | HSRA | ACI | BN | BUF | F344 | M520 | MR | WKY | WN | Variant Effect | Urogenital Expression | Human Protein Atlas | Kidney Location |

| 2 | 1 | 89017534 | U2af1l4 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | frameshift | ++ | ++++ | both |

| 2 | 1 | 100470951 | Aspdh | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | frameshift | + | ++ | tubules |

| 2 | 1 | 166675147 | Art2b | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | splice | + | +++ | both |

| 2 | 1 | 168868863 | Olr125 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | frameshift | |||

| 2 | 1 | 169683683 | Olr162 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | frameshift | |||

| 2 | 1 | 172616017 | Olr262 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | frameshift | |||

| 2 | 1 | 172752951 | Olr268 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | frameshift | |||

| 2 | 1 | 227904559 | Gm8369 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | splice | + | ||

| 2 | 1 | 281755911 | Prlhr | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | start lost | + | + | |

| 2 | 2 | 44718009 | Skiv2l2 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | stop gained | +++ | +++ | both |

| 2 | 2 | 205581428 | Ampd1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | splice | + | + | |

| 2 | 3 | 16117532 | Olr404 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | frameshift | |||

| 2 | 3 | 22657842 | Lhx2 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | frameshift | + | + | |

| 2 | 5 | 128732597 | Osbpl9 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | splice | +++ | +++ | |

| 2 | 6 | 102460160 | Zfyve26 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | splice | ++ | ++ | both |

| 2 | 6 | 137301332 | Cep170b | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | splice | +++ | ||

| 2 | 7 | 60162530 | Frs2 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | splice | +++ | ++ | |

| 2 | 7 | 129969865 | Mlc1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 1/1 | frameshift | + | + | |

| 2 | 7 | 144628308 | Hoxc5 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | frameshift | +++ | +++ | both |

| 2 | 11 | 60907018 | Gtpbp8 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 1/1 | start lost | +++ | +++ | both (low G) |

| 2 | 13 | 68360281 | Hmcn1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | start lost | ++ | ++ | both (low G) |

| 2 | 15 | 45931473 | Ints6 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | stop gained | ++ | +++ | tubules |

| 2 | X | 48213467 | Thoc1 | 1/1 | ./. | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | frameshift | +++ | ||

| 1 | 1 | 88022673 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | splice | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 129186994 | Igf1r | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | frameshift | +++ | +++ | tubules |

| 1 | 1 | 213132353 | Olr304 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | frameshift | |||

| 1 | 1 | 218420781 | Tpcn2 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | splice | ++ | +++ | both (low T) |

| 1 | 1 | 219392086 | Gpr152 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | stop gained | +++ | ||

| 1 | 4 | 71796326 | Tas2r135 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | frameshift | |||

| 1 | 4 | 113497127 | Pole4 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | frameshift | ++ | +++ | both (low G) |

| 1 | 4 | 179398636 | Lrmp | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | frameshift | +++ | ++ | |

| 1 | 5 | 4879511 | Rbpj | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | frameshift | +++ | +++ | both |

| 1 | 7 | 58403765 | Zfc3h1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | frameshift | +++ | ||

| 1 | 8 | 87709562 | Myo6 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | splice | ++ | ++ | both (low G) |

| 1 | 9 | 100166049 | Aqp12a | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | frameshift | + | – | |

| 1 | 11 | 61234925 | Cfap44 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | frameshift | +++ | ++ | |

| 1 | 12 | 48028993 | Myo1h | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | frameshift | ++ | + | |

| 1 | 12 | 48167557 | Acacb | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | splice | ++ | ++ | tubules |

| 1 | 12 | 48360475 | Dao | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | splice | ++ | + | tubules |

| 1 | 14 | 76866336 | Zfp518b | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | stop gained | ++ | ||

| 1 | 15 | 43392227 | Adra1a | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | frameshift | + | + | |

| 1 | 18 | 63546089 | Cep192 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | splice | ++ | +++ | both |

| 1 | 18 | 76710904 | Rbfa | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | 0/0 | splice | ++ | +++ | both |

| 1 | 19 | 58595346 | Pcnx2 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | frameshift | ++ | +++ | both |

| 1 | X | 45411547 | Ptges3l1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 | frameshift | n/a | ||

0/0, homozygous genotype for reference allele; 1/1, homozygous genotype for alternative allele; +, low expression; ++, moderate expression; +++ high expression based on relative expression levels from the TISSUES Database (https://tissues.jensenlab.org/Search) and The Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/). Genes highlighted in boldface are interesting candidates as discussed in the text.

c-Kit Gene and Association with CAKUT

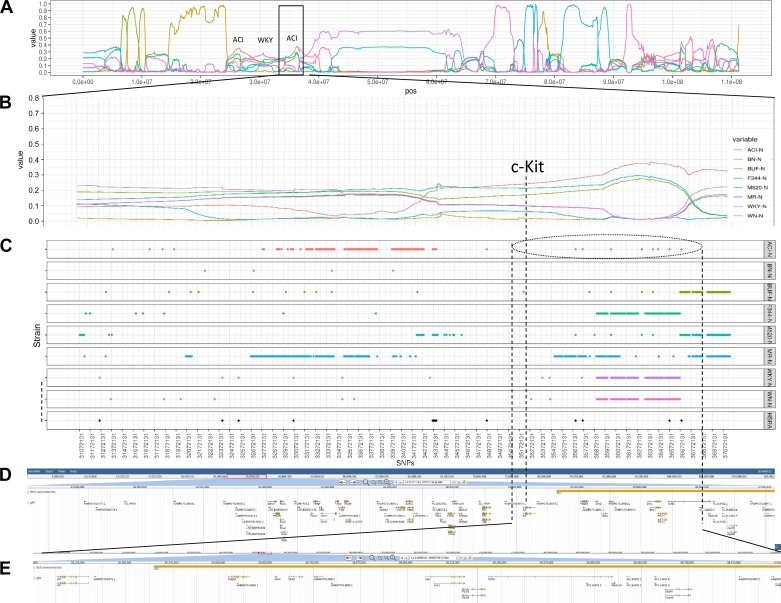

Previous work based on linkage analysis and congenic strain analysis identified an LTR within intron 1 of c-Kit as a likely candidate for CAKUT exhibited in the ACI. Since the ACI rat served as one of the founders of the HSRA model (and exhibits CAKUT), it was expected that they shared a common haplotype around c-kit (Fig. 6). Based on the HMM (SNP-based analysis), the region that contains c-Kit in the HSRA is mostly likely derived from the ACI, whereas the upstream and downstream genome could be called definitely as WKY/N or BN/N, respectively. Additionally, the c-Kit region appears highly similar across all the strains (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

High-resolution chromosome view of chromosome 14 and c-kit region. A: HMM posterior probabilities for each of the founder strains for entire chromosome 14. B: HMM posterior probabilities of founders near the c-kit gene region (chromosome 14 position 31,072,131–37,149,638). C: SNPs shared by 2 of the 9 strains (HSRA and 8 HS founder strains). D: JBROWSE gene track of the rat reference gff file for the c-kit gene region. E: an enlarged view of the JBROWSE gene track of the c-kit gene region.

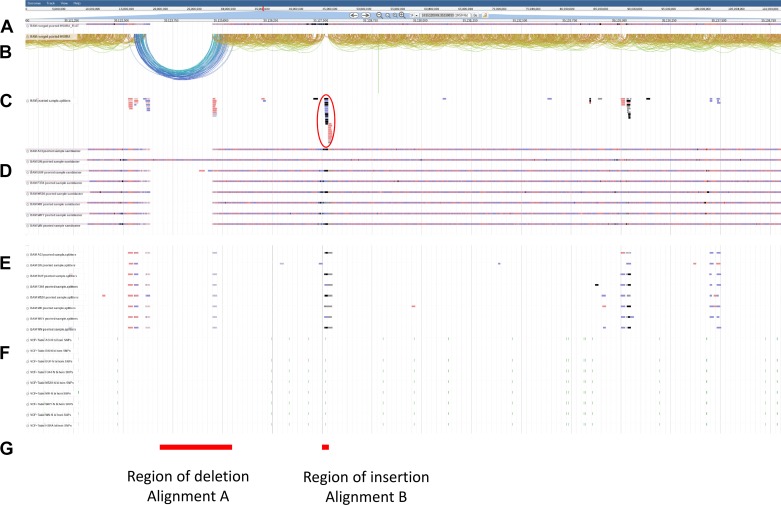

Bioinformatics analysis using LUMPY (not an SNP-based analysis) predicted a total of 42,203 deletions, 12,177 tandem duplications, and 3,324 inversions across the genome. With regard to the region around c-kit, a 1,568 bp deletion was identified within intron 1 of c-kit upstream of the previously identified insertion. Unfortunately, regardless of the bioinformatics pipeline, neither the GATK nor LUMPY pipelines made a definitive call of the presence of the insertion; however, an analysis of the split read bam files for the HSRA and HS founder strains did indicate an insertion event at that location (Fig. 7). Specifically, the HSRA and the ACI demonstrate an insertion at this location, consistent with the previously published data on the ACI. However, the insertion was not unique to the HSRA and ACI and was present in the other founders with the exception of the BN/N, which demonstrated a deletion.

Fig. 7.

Read alignment around the c-Kit intron 1 region for HSRA and NIH-HS founders. A: compact view of the HSRA BWA alignment. B: paired arch view of the HSRA BWA alignment. C: HSRA BWA alignments identified as split reads in the LUMPY analysis. D: compact view of the 8 HS founder strains BWA alignments. E: BWA alignments identified as split reads in the Lumpy analysis for 8 HS founder strains. F: SNP locations for the 8 HS founder strains and the HSRA. G: regions of interest investigated by alignments with previously described BAC libraries and local assembly of the HSRA split reads.

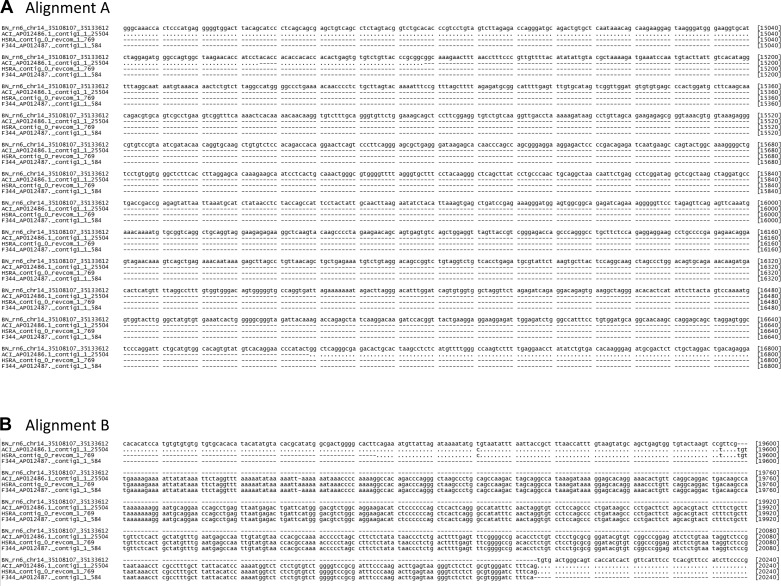

To confirm the detected c-kit insertion and deletion within intron 1, we aligned short read sequence data from the HSRA and founders as well as BAC for ACI and F344 against the BN reference genome assembly. The ACI sequence from the BAC confirmed the deletion. Additionally, the BAC-derived sequences for ACI and F344 both shared the insertion found from using the WGS data. (Fig. 8). In total, the sequence composition of the ACI, F344, and HSRA insertion sequenced was almost identical. The only difference in the HSRA assembly and ACI was a 1 bp deletion in the ACI that was not present in the HSRA; this deletion was also shared with the F344 sequence. In total, based on whole genome and the independent BAC data set, the INS/DEL in intron 1 and surrounding genome are consistent between the HSRA and ACI.

Fig. 8.

Alignment of BAC libraries in c-Kit intron 1 deletion for BN, ACI, and F344. MAFFT alignment of the BN reference sequence (chromosome 14: 35,108,107–35,133,612), ACI assembled BAC contig 1 (full length: 1–25,504), HSRA assembled contig of split read pairs (full length: 1–769), and F344 assembled BAC contig 1 (full length: 1–584). Dashes (-) represent gaps, and dots (·) represent identical sequences to the reference. A: the sequence segments over the ACI deletion in respect to the BN from alignment position 14,881 to 16,800 (alignment A from Fig. 7). B: the sequence segments over the ACI, HSRA, and F344 insertion in respect to the BN from alignment position 19,441 to 20,240 (alignment B from Fig. 7).

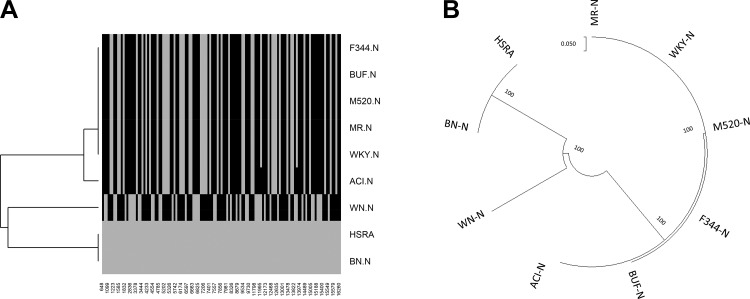

Mitochondrial Genome of the HSRA and Eight Founders

An analysis of the mitochondrial genome sequences from the eight founders of the HS strain identified a total of 127 polymorphic variants compared with BN/N reference. Interestingly, five of the strains (MR/N, BUF/N, M520/N, WKY/N, and F344/N) had the same genotypes for all 127 variants (Fig. 9A), while ACI/N exhibited two additional variants compared with BN/N. The HSRA demonstrated the same mitochondrial genome as the BN/N, distinct from the ACI. In total, phylogenetic analysis of the mitochondria resulted in three clades: 1) HSRA and BN, 2) WN, and 3) the other six strains (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

Phylogenetic analysis of the HSRA mitochondria and 8 HS founders. A: a dendrogram of the SNP locations and states (gray, reference allele; black, variant) of the 127 positions for the HSRA and 8 HS founder strains. B: an unrooted phylogenetic tree. The relationship of the HSRA and the other 8 HS founder strains based upon the phylogenetic analysis as described in material and methods.

DISCUSSION

As an outbred model, the HS rat population’s diverse genotypes, resulting from the segregation of genome segments derived from the eight founders (BN/SsN, MR/N, BUF/N, M520/N, WN/N, ACI/N, WKY/N, and F344/N), generate phenotypic variability that allows for efficient genetic mapping of complex traits, including diabetes (77a), adiposity (33), and despair-like behavior (27), among others. An alternative use of the genetic/phenotype diversity in the HS model is to select for specific traits of interest and concentrate those alleles (e.g., susceptibility or resistance) into a single strain. For example, low‐capacity running and high‐capacity running strains are outbred lines generated by selective breeding the HS for differences in aerobic capacity in response to speed‐ramped treadmill running time to exhaustion (35). Similarly, in working with a population of HS animals to investigate cardiovascular and renal traits, Solberg Woods et al. (79) identified a family of HS rats that demonstrated a high incidence of CAKUT/renal agenesis (6/9 offspring). Subsequently, this family was used as the founder population to develop the HSRA model (>20 generation brother-sister breed) demonstrating a high incidence of unilateral renal agenesis ranging between 50 and 75% in offspring (87). The HSRA also variably exhibits other CAKUT such as ipsilateral absence of sex organs (e.g., testis, epididymis, and seminal vesicles in males).

A unique advantage of the HSRA is the ability to address physiological questions, such as what is the cardiovascular and renal impact of loss of one kidney (renal agenesis) compared with normal two-kidney littermates. In the HSRA, this can be directly addressed without experimentally removing a kidney and on the same genetic background (Fig. 1). The model also allows direct comparison between congenital versus acquired (e.g., removal due to kidney donation, trauma, or cancer) as a kidney can be experimentally removed from two-kidney littermates. In particular, our group has conducted several studies on age-related impact of CAKUT/renal agenesis in development of renal disease (87), susceptibility to hypertension (86), and diabetes (15). However, there has been no investigation of the genetic basis of CAKUT and/or altered nephrogenesis in the HSRA model. Thus, the major objective of the current study was to perform WGS of the HSRA to map its genetic architecture with respect to the eight progenitor strains that compose the HS model, i.e., investigate whether genes linked to human CAKUT demonstrate deleterious variants, identify new candidate genes that could be involved in CAKUT, and lay the groundwork for future genetics mapping/linkage studies.

The sequencing of the HSRA generated a high-resolution mosaic of its genome structure, providing the ability to identify SNP and INDEL in the HSRA compared with the reference genome. Subsequently, variants were classified by location (e.g., intergenic, coding, intron, etc.), putative impact on protein coding (synonymous, nonsynonymous), and predicted impact on noncoding regions (splicing, frameshift, stop/start site, and untranslated region). In total, the number of SNP and INDEL, along with predicted effects, was consistent with sequence data from other inbred strains (2, 70). As the HSRA was selectively bred from the HS, the sequencing data more importantly provided the ability to track the origin of the sequence variation/haplotype blocks derived from the HS founders (BN/SsN, MR/N, BUF/N, M520/N, WN/N, ACI/N, WKY/N, and F344/N). This appears to be novel finding with respect to development of an inbred strain from the HS population. While the genomes of numerous inbred strains have been sequenced (2), a comparison of the genomes provides information only on what alleles/haplotypes are shared/different across the strains, not the specific origin of the haplotypes as illustrated by the HMM (eight inbred strains and the HSRA).

Urogenital and kidney development (nephrogenesis) is coordinated via complex interactions among numerous transcription/growth factors and intracellular signaling molecules (85). The kidney originates from a reciprocal interaction between distinct cell types within the intermediate mesoderm of which arise three successive pairs of renal structures (pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros). As the permanent kidney develops from the metanephros (i.e., ureteric bud invades the metanephric mesenchyme), the fate of the mesonephros is to become part of the epididymis, vas deferens, and seminal vesicles in males and in females, atrophies, to become part of the ovaries. Thus, there are common developmental pathways to the urogenital and renal system which explains why there is wide phenotypic variability associated with CAKUT.

There are at least 15 recessive and 25 dominant genes that have been linked to CAKUT in humans and rodent models (83). Of these, there are several that have been directly linked with renal agenesis, including Eya1 (90), Fras (36), Frem (61), Greb1l (73), and Ret (3, 76). In the current study, the majority (37/42) of these genes were not found to exhibit any predicted deleterious variants in the HSRA. There were five genes (Fras1, Frem, Grip1, Hnf1b, and Six2) that did demonstrate high impact calls; however, these variants were shared by all eight HS founder strains. This finding suggests that it is unlikely that any of these genes underlie CAKUT/renal agenesis in the HSRA as it would also be expected that founders with these variants would similarly exhibit CAKUT, which they do not (excluding ACI).

The curation and analysis of genes exhibiting high impact variants identified a number of novel genes that may be linked to CAKUT and kidney development. For the kidney, a key stage in development is the induction of the UB into the MM, which is controlled by glial-derived neurotrophic factor (Gdnf) and the tyrosine kinase receptor c-Ret, along with the co-receptor GFRα1. The levels and spatial expression of Gdnf play a central role in initiating budding and are regulated by multiple transcription and growth factors. A comprehensive list of genes and pathways involved in kidney development has been reviewed extensively by others (64). In total, these studies have established that alterations in spatiotemporal expression of many genes/proteins can impact kidney development (ranging from its complete absence to altered/reduced nephrogenesis). Based on the assumption that the causative allele/variants for CAKUT would likely be unique and only shared between the HSRA and one or two of the HS founders, candidate genes were assessed based on their level of urogenital expression and localization in the kidney.

A number of interesting candidate genes (Frs2, Hoxc5, and Rbpj) were identified that exhibit relatively high expression in the urogenital system and the kidney compared (based on databases searches) with the others (n = 46), as well as strong experimental/mechanistic evidence to demonstrate a central role in development. First, FRS2, also known as fibroblast growth factor receptor substrate 2, has been shown to interact with RET (via binding to tyrosine 1062) in the presence of activated GDNF (42). While mutations in Frs2 have not been associated with CAKUT, the fibroblast growth factor pathway has been shown to play an important role in kidney development (20, 84). Genetic knockout of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (Fgfr2) leads to a significant reduction in nephron number compared with wild type (25, 68). By 1 yr of age, mutant mice exhibit a significant increase in systolic blood pressure and more glomerular/tubular injury versus controls (67). The findings of this study are consistent with the characterization of the HSRA model as single kidney animals demonstrate reduced nephron number (in the remaining kidney) and are prone to develop hypertension and kidney injury (86, 87).

Second, Hoxc5 belongs to the homeobox family of genes, which are a highly conserved family of transcription factors that play an important role in morphogenesis (65). Mammals possess four similar homeobox gene clusters, HoxA, HoxB, HoxC, and HoxD, which are located on different chromosomes and consist of 9–11 genes arranged in tandem. Hox genes have been linked with urogenital and kidney development (88). For example, in HoxAc/− mutant animals, a significant proportion of mice (surviving birth) develop variable degrees of unilateral or bilateral polycystic kidneys (18). This is consistent with previous studies in animals lacking the HoxD cluster (19). In addition, Hoxa11, Hoxa13, Hoxc10, and Hoxc11 have also been associated with CAKUT (83). While there is no direct known involvement of Hoxc5 in urogenital/renal development, it is an interesting candidate gene based on the known involvement of other Hox genes in urogenital/kidney development.

Lastly, recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J region (RBPJ) is a major downstream effector of the evolutionarily conserved Notch signaling pathway. The notch pathway has been linked with kidney development in numerous studies [as reviewed in (4) and (50)]. For example, renal stromal cells derived from the FOXD1 (Forkhead Box D1) lineage differentiate into cells that compose the kidney arterioles, including mesangial cells and pericytes; however, deletion of Rbpj in these cells results in significant kidney abnormalities (7, 47). Thus, RBPJ is essential for proper formation and maintenance of the kidney vasculature and glomeruli, suggesting that it is a potential candidate gene linked to CAKUT/altered nephrogenesis in the HSRA.

Interestingly, the ACI founder of the HS model exhibits CAKUT in 10–15% of offspring with the genetic cause being attributed to the presence of an LTR within intron 1 of c-Kit gene. An obvious hypothesis is that both HSRA and ACI share this common genetic cause and that other factors in the HSRA genome (from the other founders) contribute to increased penetrance of CAKUT (75% in the HSRA vs. 15% in ACI). A major finding of this study is that the HSRA genome contains the insertion within intron 1 of c-Kit linked to CAKUT in the ACI progenitor (72). More so, the region around the c-kit locus [established by linkage analysis (75)] is consistent with the HSRA being derived from the ACI genome, suggesting the models share a common genetic factor that leads to CAKUT. However, the sequence comparison shows that the HSRA and ACI are not the only strains that exhibit the insertion, it is also present in almost all of the founder animals (excluding the BN/N). The presence of the insertion in the other founders, including BUF/N, F344/N, M520/N, MR/N, WKY/N, and WN/N, which do not exhibit CAKUT or renal agenesis, suggests it is unlikely causative to the CAKUT trait in ACI and HSRA.

An analysis of the mitochondrial genome from the HSRA and eight HS founders showed that most of the inbred strains share the same mitochondrial genome; however, the HSRA mitochondria appear to originate from the BN, which is quite distinct from the others. The impact on mitochondrial genome variation on complex disease is not well studied, but there have been a few studies that suggest that mitochondrial variation leads to altered mitochondrial function (16, 55, 59). In Buford et al. (10), mitochondrial DNA-encoded variants were found to be associated with variation in systolic blood pressure and mean arterial pressure among older adults. Additionally, differences in the mitochondrial genome were identified between the Dahl salt-sensitive (S) rat (model of hypertension and kidney disease) and the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) (41). An S.SHRmt conplastic strain (mitochondria of the S rat was substituted with that of the SHR) demonstrated a significant increase in mitochondrial DNA copy number, decreased reactive oxygen species, increased aerobic treadmill running capacity, and an increase in survival compared with the S rat (40). While it is likely that the causative genetic factor/s responsible for CAKUT in HSRA are located on the nuclear genome, a tempting hypothesis is that differences in the mitochondrial genome between the HSRA and ACI could play a role in the observed difference in penetrance of the CAKUT/altered nephrogenesis. It is expected that future analysis of a conplastic strain for the HSRA and ACI (e.g., swapping the ACI mitochondria with HSRA/BN mitochondria in the ACI) will provide insight into the potential role the mitochondria is playing in CAKUT/renal agenesis phenotype.

The HSRA rat via several physiological studies has provided novel insight into the role of kidney loss/reduced nephron number in the development of cardiovascular and renal disease. The detailed mapping of the genetic architecture of the HSRA model and the identification of genes carrying deleterious variants provide important information on potential genes/modifiers associated with CAKUT/loss of one kidney. Definitive identification of the causative gene will require genetic analysis using a very large HS population (as CAKUT occurs at extremely low incidence at ~1–2%) and/or linkage analysis using the HSRA. In summary, it is our hope that a better understanding of the genetic architecture of the HSRA model of CAKUT will ultimately provide novel insight into genes and pathways involved in urogenital and renal development in humans.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01HL-137673 (M. R. Garrett). The work performed through the University of Mississippi Medical Center Molecular and Genomics Facility is supported, in part, by funds from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH, including Mississippi INBRE (P20GM-103476), Center for Psychiatric Neuroscience (CPN)-COBRE (P30GM-103328) and Obesity, Cardiorenal and Metabolic Diseases-COBRE (P20GM-104357). High performance computing via the Magnolia Cluster is supported by The University of Southern Mississippi/NSF under the Major Research Instrumentation Program Grant ACI1626217.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.C.J. and M.R.G. conceived and designed research; A.C.J. performed experiments; K.C.S., A.C.J., and M.R.G. analyzed data; K.C.S., M.B.C., W.Y., and M.R.G. interpreted results of experiments; K.C.S. and M.R.G. prepared figures; K.C.S., M.B.C., A.C.J., and M.R.G. drafted manuscript; K.C.S., M.B.C., A.C.J., and M.R.G. edited and revised manuscript; K.C.S., M.B.C., A.C.J., W.Y., and M.R.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G; The Gene Ontology Consortium . Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 25: 25–29, 2000. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atanur SS, Diaz AG, Maratou K, Sarkis A, Rotival M, Game L, Tschannen MR, Kaisaki PJ, Otto GW, Ma MC, Keane TM, Hummel O, Saar K, Chen W, Guryev V, Gopalakrishnan K, Garrett MR, Joe B, Citterio L, Bianchi G, McBride M, Dominiczak A, Adams DJ, Serikawa T, Flicek P, Cuppen E, Hubner N, Petretto E, Gauguier D, Kwitek A, Jacob H, Aitman TJ. Genome sequencing reveals loci under artificial selection that underlie disease phenotypes in the laboratory rat. Cell 154: 691–703, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attié-Bitach T, Abitbol M, Gérard M, Delezoide A-L, Augé J, Pelet A, Amiel J, Pachnis V, Munnich A, Lyonnet S, Vekemans M. Expression of the RET proto-oncogene in human embryos. Am J Med Genet 80: 481–486, 1998. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barak H, Surendran K, Boyle SC. The Role of Notch Signaling in Kidney Development and Disease, in Notch Signaling in Embryology and Cancer (Reichrath J, Reichrath S, editors). New York, NY: Springer US, 2012, p. 99–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertram JF, Douglas-Denton RN, Diouf B, Hughson MD, Hoy WE. Human nephron number: implications for health and disease. Pediatr Nephrol 26: 1529–1533, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30: 2114–2120, 2014. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyle SC, Liu Z, Kopan R. Notch signaling is required for the formation of mesangial cells from a stromal mesenchyme precursor during kidney development. Development 141: 346–354, 2014. doi: 10.1242/dev.100271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradbury PJ, Zhang Z, Kroon DE, Casstevens TM, Ramdoss Y, Buckler ES. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics 23: 2633–2635, 2007. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buels R, Yao E, Diesh CM, Hayes RD, Munoz-Torres M, Helt G, Goodstein DM, Elsik CG, Lewis SE, Stein L, Holmes IH. JBrowse: a dynamic web platform for genome visualization and analysis. Genome Biol 17: 66, 2016. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0924-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buford TW, Manini TM, Kairalla JA, McDermott MM, Vaz Fragoso CA, Chen H, Fielding RA, King AC, Newman AB, Tranah GJ. Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variants Associated With Blood Pressure Among 2 Cohorts of Older Adults. J Am Heart Assoc 7: e010009, 2018. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carl HP, Spuhler K. Development of the National Institutes of Health Genetically Heterogeneous Rat Stock. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 8: 477–479, 1984. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1984.tb05706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiang C, Layer RM, Faust GG, Lindberg MR, Rose DB, Garrison EP, Marth GT, Quinlan AR, Hall IM. SpeedSeq: ultra-fast personal genome analysis and interpretation. Nat Methods 12: 966–968, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, Sivachenko A, Jaffe D, Sougnez C, Gabriel S, Meyerson M, Lander ES, Getz G. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol 31: 213–219, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Cingolani P, Patel VM, Coon M, Nguyen T, Land SJ, Ruden DM, Lu X. Using Drosophila melanogaster as a Model for Genotoxic Chemical Mutational Studies with a New Program, SnpSift. Front Genet 3: 35, 2012. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang L, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, Land SJ, Lu X, Ruden DM. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 6: 80–92, 2012. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cobb MB, Wu W, Johnson AC, Attipoe EM, Garrett MR. Abstract P1124: Nephron Deficiency and Hyperglycemic Renal Injury Using a Novel One Kidney Rat Model. Hypertension 74, Suppl 1: AP1124, 2019. doi: 10.1161/hyp.74.suppl_1.P1124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coskun PE, Beal MF, Wallace DC. Alzheimer’s brains harbor somatic mtDNA control-region mutations that suppress mitochondrial transcription and replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 10726–10731, 2004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403649101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, Philippakis AA, del Angel G, Rivas MA, Hanna M, McKenna A, Fennell TJ, Kernytsky AM, Sivachenko AY, Cibulskis K, Gabriel SB, Altshuler D, Daly MJ. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet 43: 491–498, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di-Poï N, Koch U, Radtke F, Duboule D. Additive and global functions of HoxA cluster genes in mesoderm derivatives. Dev Biol 341: 488–498, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di-Poï N, Zákány J, Duboule D. Distinct roles and regulations for HoxD genes in metanephric kidney development. PLoS Genet 3: e232, 2007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Giovanni V, Walker KA, Bushnell D, Schaefer C, Sims-Lucas S, Puri P, Bates CM. Fibroblast growth factor receptor-Frs2α signaling is critical for nephron progenitors. Dev Biol 400: 82–93, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durinck S, Moreau Y, Kasprzyk A, Davis S, De Moor B, Brazma A, Huber W. BioMart and Bioconductor: a powerful link between biological databases and microarray data analysis. Bioinformatics 21: 3439–3440, 2005. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Durinck S, Spellman PT, Birney E, Huber W. Mapping identifiers for the integration of genomic datasets with the R/Bioconductor package biomaRt. Nat Protoc 4: 1184–1191, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Gebali S, Mistry J, Bateman A, Eddy SR, Luciani A, Potter SC, Qureshi M, Richardson LJ, Salazar GA, Smart A, Sonnhammer ELL, Hirsh L, Paladin L, Piovesan D, Tosatto SCE, Finn RD. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res 47, D1: D427–D432, 2019. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faust GG, Hall IM. SAMBLASTER: fast duplicate marking and structural variant read extraction. Bioinformatics 30: 2503–2505, 2014. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hains D, Sims-Lucas S, Kish K, Saha M, McHugh K, Bates CM. Role of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 in kidney mesenchyme. Pediatr Res 64: 592–598, 2008. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318187cc12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harambat J, van Stralen KJ, Kim JJ, Tizard EJ. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in children. Pediatr Nephrol 27: 363–373, 2012. [Erratum in Pediatr Nephrol 27: 507, 2012] doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1939-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holl K, He H, Wedemeyer M, Clopton L, Wert S, Meckes JK, Cheng R, Kastner A, Palmer AA, Redei EE, Solberg Woods LC. Heterogeneous stock rats: a model to study the genetics of despair-like behavior in adolescence. Genes Brain Behav 17: 139–148, 2018. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Issa N, Vaughan LE, Denic A, Kremers WK, Chakkera HA, Park WD, Matas AJ, Taler SJ, Stegall MD, Augustine JJ, Rule AD. Larger nephron size, low nephron number, and nephrosclerosis on biopsy as predictors of kidney function after donating a kidney. Am J Transplant 19: 1989–1998, 2019. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackman SD, Vandervalk BP, Mohamadi H, Chu J, Yeo S, Hammond SA, Jahesh G, Khan H, Coombe L, Warren RL, Birol I. ABySS 2.0: resource-efficient assembly of large genomes using a Bloom filter. Genome Res 27: 768–777, 2017. doi: 10.1101/gr.214346.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain S, Chen F. Developmental pathology of congenital kidney and urinary tract anomalies. Clin Kidney J 12: 382–399, 2018. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfy112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasiske BL. Outcomes after living kidney donation: what we still need to know and why. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 335–337, 2014. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30: 772–780, 2013. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keele GR, Prokop JW, He H, Holl K, Littrell J, Deal A, Francic S, Cui L, Gatti DM, Broman KW, Tschannen M, Tsaih S-W, Zagloul M, Kim Y, Baur B, Fox J, Robinson M, Levy S, Flister MJ, Mott R, Valdar W, Solberg Woods LC. Genetic Fine-Mapping and Identification of Candidate Genes and Variants for Adiposity Traits in Outbred Rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 26: 213–222, 2018. doi: 10.1002/oby.22075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keller G, Zimmer G, Mall G, Ritz E, Amann K. Nephron number in patients with primary hypertension. N Engl J Med 348: 101–108, 2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koch LG, Britton SL. Divergent selection for aerobic capacity in rats as a model for complex disease. Integr Comp Biol 45: 405–415, 2005. doi: 10.1093/icb/45.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kohl S, Hwang D-Y, Dworschak GC, Hilger AC, Saisawat P, Vivante A, Stajic N, Bogdanovic R, Reutter HM, Kehinde EO, Tasic V, Hildebrandt F. Mild recessive mutations in six Fraser syndrome-related genes cause isolated congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1917–1922, 2014. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013101103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 305: 567–580, 2001. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res 19: 1639–1645, 2009. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol 35: 1547–1549, 2018. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumarasamy S, Gopalakrishnan K, Abdul-Majeed S, Partow-Navid R, Farms P, Joe B. Construction of two novel reciprocal conplastic rat strains and characterization of cardiac mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 304: H22–H32, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00534.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumarasamy S, Gopalakrishnan K, Shafton A, Nixon J, Thangavel J, Farms P, Joe B. Mitochondrial polymorphisms in rat genetic models of hypertension. Mamm Genome 21: 299–306, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s00335-010-9259-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurokawa K, Iwashita T, Murakami H, Hayashi H, Kawai K, Takahashi M. Identification of SNT/FRS2 docking site on RET receptor tyrosine kinase and its role for signal transduction. Oncogene 20: 1929–1938, 2001. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Layer RM, Chiang C, Quinlan AR, Hall IM. LUMPY: a probabilistic framework for structural variant discovery. Genome Biol 15: R84, 2014. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-6-r84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H. Toward better understanding of artifacts in variant calling from high-coverage samples. Bioinformatics 30: 2843–2851, 2014. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup . The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079, 2009. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li ZY, Chen YM, Qiu LQ, Chen DQ, Hu CG, Xu JY, Zhang XH. Prevalence, types, and malformations in congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract in newborns: a retrospective hospital-based study. Ital J Pediatr 45: 50, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s13052-019-0635-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin EE, Sequeira-Lopez MLS, Gomez RA. RBP-J in FOXD1+ renal stromal progenitors is crucial for the proper development and assembly of the kidney vasculature and glomerular mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F249–F258, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00313.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindenbaum P, Redon R. bioalcidae, samjs and vcffilterjs: object-oriented formatters and filters for bioinformatics files. Bioinformatics 34: 1224–1225, 2018. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Littrell J, Tsaih S-W, Baud A, Rastas P, Solberg-Woods L, Flister MJ. A High-Resolution Genetic Map for the Laboratory Rat. G3 (Bethesda) 8: 2241–2248, 2018. doi: 10.1534/g3.118.200187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Z, Chen S, Boyle S, Zhu Y, Zhang A, Piwnica-Worms DR, Ilagan MX, Kopan R. The extracellular domain of Notch2 increases its cell-surface abundance and ligand responsiveness during kidney development. Dev Cell 25: 585–598, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 252: 1162–1164, 1991. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luyckx VA, Brenner BM. Clinical consequences of developmental programming of low nephron number. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 0: ar.24270, 2019. doi: 10.1002/ar.24270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, DePristo MA. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 20: 1297–1303, 2010. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McKinney W. Data structures for statistical computing in python. In: Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, 2010, p. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mehta P, Mellick GD, Rowe DB, Halliday GM, Jones MM, Manwaring N, Vandebona H, Silburn PA, Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Sue CM. Mitochondrial DNA haplogroups J and K are not protective for Parkinson’s disease in the Australian community. Mov Disord 24: 290–292, 2009. doi: 10.1002/mds.22389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mitchell AL, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, Blum M, Bork P, Bridge A, Brown SD, Chang H-Y, El-Gebali S, Fraser MI, Gough J, Haft DR, Huang H, Letunic I, Lopez R, Luciani A, Madeira F, Marchler-Bauer A, Mi H, Natale DA, Necci M, Nuka G, Orengo C, Pandurangan AP, Paysan-Lafosse T, Pesseat S, Potter SC, Qureshi MA, Rawlings ND, Redaschi N, Richardson LJ, Rivoire C, Salazar GA, Sangrador-Vegas A, Sigrist CJA, Sillitoe I, Sutton GG, Thanki N, Thomas PD, Tosatto SCE, Yong SY, Finn RD. InterPro in 2019: improving coverage, classification and access to protein sequence annotations. Nucleic Acids Res 47, D1: D351–D360, 2019. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mjøen G, Hallan S, Hartmann A, Foss A, Midtvedt K, Øyen O, Reisæter A, Pfeffer P, Jenssen T, Leivestad T, Line P-D, Øvrehus M, Dale DO, Pihlstrøm H, Holme I, Dekker FW, Holdaas H. Long-term risks for kidney donors. Kidney Int 86: 162–167, 2014. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mott R, Talbot CJ, Turri MG, Collins AC, Flint J. A method for fine mapping quantitative trait loci in outbred animal stocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 12649–12654, 2000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230304397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naing A, Kenchaiah M, Krishnan B, Mir F, Charnley A, Egan C, Bano G. Maternally inherited diabetes and deafness (MIDD): diagnosis and management. J Diabetes Complications 28: 542–546, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Narasimhan V, Danecek P, Scally A, Xue Y, Tyler-Smith C, Durbin R. BCFtools/RoH: a hidden Markov model approach for detecting autozygosity from next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 32: 1749–1751, 2016. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nathanson J, Swarr DT, Singer A, Liu M, Chinn A, Jones W, Hurst J, Khalek N, Zackai E, Slavotinek A. Novel FREM1 mutations expand the phenotypic spectrum associated with Manitoba-oculo-tricho-anal (MOTA) syndrome and bifid nose renal agenesis anorectal malformations (BNAR) syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 161A: 473–478, 2013. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nyengaard JR, Bendtsen TF. Glomerular number and size in relation to age, kidney weight, and body surface in normal man. Anat Rec 232: 194–201, 1992. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092320205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paparel P, N’Diaye A, Laumon B, Caillot JL, Perrin P, Ruffion A. The epidemiology of trauma of the genitourinary system after traffic accidents: analysis of a register of over 43,000 victims. BJU Int 97: 338–341, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.05900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patel SR, Dressler GR. The genetics and epigenetics of kidney development. Semin Nephrol 33: 314–326, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patterson LT, Potter SS. Hox genes and kidney patterning. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 12: 19–23, 2003. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods 8: 785–786, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Poladia DP, Kish K, Kutay B, Bauer J, Baum M, Bates CM. Link between reduced nephron number and hypertension: studies in a mutant mouse model. Pediatr Res 59: 489–493, 2006. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000202764.02295.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Poladia DP, Kish K, Kutay B, Hains D, Kegg H, Zhao H, Bates CM. Role of fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 and 2 in the metanephric mesenchyme. Dev Biol 291: 325–339, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26: 841–842, 2010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ramdas S, Ozel AB, Treutelaar MK, Holl K, Mandel M, Woods LCS, Li JZ. Extended regions of suspected mis-assembly in the rat reference genome. Sci Data 6: 39, 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41597-019-0041-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Samanas NB, Commers TW, Dennison KL, Harenda QE, Kurz SG, Lachel CM, Wavrin KL, Bowler M, Nijman IJ, Guryev V, Cuppen E, Hubner N, Sullivan R, Vezina CM, Shull JD. Genetic etiology of renal agenesis: fine mapping of Renag1 and identification of Kit as the candidate functional gene. PLoS One 10: e0118147, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sanna-Cherchi S, Khan K, Westland R, Krithivasan P, Fievet L, Rasouly HM, Ionita-Laza I, Capone VP, Fasel DA, Kiryluk K, Kamalakaran S, Bodria M, Otto EA, Sampson MG, Gillies CE, Vega-Warner V, Vukojevic K, Pediaditakis I, Makar GS, Mitrotti A, Verbitsky M, Martino J, Liu Q, Na Y-J, Goj V, Ardissino G, Gigante M, Gesualdo L, Janezcko M, Zaniew M, Mendelsohn CL, Shril S, Hildebrandt F, van Wijk JAE, Arapovic A, Saraga M, Allegri L, Izzi C, Scolari F, Tasic V, Ghiggeri GM, Latos-Bielenska A, Materna-Kiryluk A, Mane S, Goldstein DB, Lifton RP, Katsanis N, Davis EE, Gharavi AG. Exome-wide Association Study Identifies GREB1L Mutations in Congenital Kidney Malformations. Am J Hum Genet 101: 789–802, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seikaly MG, Ho PL, Emmett L, Fine RN, Tejani A. Chronic renal insufficiency in children: the 2001 Annual Report of the NAPRTCS. Pediatr Nephrol 18: 796–804, 2003. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shull JD, Lachel CM, Strecker TE, Spady TJ, Tochacek M, Pennington KL, Murrin CR, Meza JL, Schaffer BS, Flood LA, Gould KA. Genetic bases of renal agenesis in the ACI rat: mapping of Renag1 to chromosome 14. Mamm Genome 17: 751–759, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s00335-006-0004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Skinner MA, Safford SD, Reeves JG, Jackson ME, Freemerman AJ. Renal aplasia in humans is associated with RET mutations. Am J Hum Genet 82: 344–351, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sneath PHA, Sokal RR. Numerical taxonomy. The principles and practice of numerical classification. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 77a.Solberg Woods LC, Holl KL, Oreper D, Xie Y, Tsaih S-W, Valdar W. Fine-mapping diabetes-related traits, including insulin resistance, in heterogeneous stock rats. Physiol Genomics 44: 1013–1026, 2012. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00040.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Solberg Woods LC, Palmer AA. Using Heterogeneous Stocks for Fine-Mapping Genetically Complex Traits, in Rat Genomics (Hayman GT, Smith JR, Dwinell MR, Shimoyama M, editors). New York, NY: Springer New York, 2019, p. 233–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Solberg Woods LC, Stelloh C, Regner KR, Schwabe T, Eisenhauer J, Garrett MR. Heterogeneous stock rats: a new model to study the genetics of renal phenotypes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F1484–F1491, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00002.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tain Y-L, Luh H, Lin C-Y, Hsu C-N. Incidence and Risks of Congenital Anomalies of Kidney and Urinary Tract in Newborns: A Population-Based Case-Control Study in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore) 95: e2659, 2016. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]