Abstract

Astrocytes generate robust cytoplasmic calcium signals in response to reductions in extracellular glucose. This calcium signal, in turn, drives purinergic gliotransmission, which controls the activity of catecholaminergic (CA) neurons in the hindbrain. These CA neurons are critical to triggering glucose counter-regulatory responses (CRRs) that, ultimately, restore glucose homeostasis via endocrine and behavioral means. Although the astrocyte low-glucose sensor involvement in CRR has been accepted, it is not clear how astrocytes produce an increase in intracellular calcium in response to a decrease in glucose. Our ex vivo calcium imaging studies of hindbrain astrocytes show that the glucose type 2 transporter (GLUT2) is an essential feature of the astrocyte glucosensor mechanism. Coimmunoprecipitation assays reveal that the recombinant GLUT2 binds directly with the recombinant Gq protein subunit that activates phospholipase C (PLC). Additional calcium imaging studies suggest that GLUT2 may be connected to a PLC-endoplasmic reticular-calcium release mechanism, which is amplified by calcium-induced calcium release (CICR). Collectively, these data help outline a potential mechanism used by astrocytes to convert information regarding low-glucose levels into intracellular changes that ultimately regulate the CRR.

Keywords: counter-regulation, ex vivo brain slice, live cell calcium imaging, low-glucose sensing, solitary nucleus

INTRODUCTION

Glucoregulation is critical for brain function and survival. Glucose sensors in the periphery and in the brain monitor glucose availability (10, 57, 65, 82, 85). These glucose sensors detect glucose deficit and activate glucoregulatory responses that restore glucose levels, referred to as counter-regulatory responses (CRRs) (16). An essential central nervous system (CNS) site for the defense against glucoprivation is the caudal medulla, which contains at least two glucoregulatory sites: the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST) and the ventrolateral medulla (VLM). The NST is the recipient of vagal afferent projections from peripheral glucose sensors (4, 55, 91) and maintains efferent connections necessary for regulating nutrient homeostasis and digestion (3, 9, 17, 18, 52, 68, 88). The NST and VLM are brain sites important for generation of physiological and behavioral responses to glucose deficit. This includes increased feeding as well as elevation of circulating glucagon, corticosteroids, and epinephrine (7, 47, 67). In addition, reduced glucose availability triggers dramatic acceleration of gastric motility, a response that increases availability of ingested carbohydrate for glucose absorption (13, 16, 33, 80).

Hindbrain catecholaminergic (CA) neurons are critically involved in glucoregulatory functions. Selective immunotoxin lesions, gene silencing, chemogenetic activation, and localized glucoprivation have revealed that activation of these CA neurons is necessary for elicitation of feeding, corticosterone secretion, and elevation of adrenal medullary secretion in response to glucose deficit (12, 42, 44, 64, 67). Though earlier studies have suggested glial involvement in brain regulation of blood glucose (38, 47, 89), recent studies have implicated astrocytes as the primary glucosensors responsible for activating hindbrain CA neurons that drive CRRs in reaction to glucose deficit (49, 69, 71).

Live cell ex vivo imaging studies have demonstrated that NST astrocytes increase cytoplasmic calcium (Ca2+) in response to either decreased glucose concentrations or to reductions in cellular glucose utilization by exposure to 2-deoxyglucose (2DG) (49). Physiological studies have suggested that medullary astrocytes are also necessary for the hyperglycemic response to hindbrain cytoglucopenia. Fourth ventricular administration of 2DG to anesthetized rats increase plasma glucose levels (73). Pre-exposure of the fourth ventricle to fluorocitrate [FC; a blocker of astrocytic metabolism (28)] suppressed the glucoprivation-induced increase in blood glucose levels (73). Recent live cell calcium imaging studies in hindbrain slices show that although NST and VLM CA neurons are robustly activated by glucose deficits, their responsiveness is dependent on an initial activation of hindbrain astrocytes and purinergic gliotransmission (71).

Although the involvement of the hindbrain astrocyte in glucoregulation seems clear, the mechanism by which the astrocyte transduces information about the low-glucose state into a robust calcium signal and subsequent gliotransmission is not clear. One problem in understanding the astrocyte mechanism is that it must be fundamentally different from other “classic” glucose sensor mechanisms that also result in increased intracellular calcium. For example, the pancreatic islet β cell responds to elevated glucose availability with increased intracellular calcium. This response is due to extracellular glucose entry through the glucose type 2 transporter (GLUT2). Increased cytoplasmic glucose is rapidly metabolized through glycolysis with subsequent ATP generation that promotes closure of ATP-regulated potassium channels, depolarization, calcium entry, and calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (34, 54, 76). Ironically, the low-glucose sensitive astrocyte may also use GLUT2 as the portal through which intracellular glucose is rapidly dialyzed against a glucose-depleted extracellular space (38, 46, 47). In this case, however, low glucose signals a robust increase in cytoplasmic calcium in the astrocyte, which is opposite the pattern of the β cell (i.e., high glucose evoking increase in cytoplasmic calcium). These findings showcase the utility of the GLUT2 system with coupling to calcium signaling being able to sense both low and high glucose, depending on the cell type.

Finally, live cell imaging data from our laboratory has shown that the astrocyte calcium response to a glucopenic challenge is relatively rapid: on the order of a few minutes. This is significantly more rapid than a passive ER calcium leakage mechanism could explain (35). Once it became clear that the astrocyte calcium signal was dependent on both GLUT2 and initiated by the activation of phospholipase C (PLC), we considered the possibility that GLUT2 may be linked to PLC activation through a “transceptor” mechanism. This possibility has been suggested before (78, 79) and has been reinforced by the discovery that the GLUT2 transporter may have long intracellular loop structures unrelated to the transporter function (25) but serving as a potential adaptor region for cellular transduction mechanisms, such as PLC (81). PLC is normally triggered by G protein GαQ (Gαq) that may serve as a connection between GLUT2 receptor and PLC. To examine this possibility, we conducted in vitro coimmunoprecipitation studies with recombinant proteins to determine if Gαq binds to GLUT2.

The results of the present study provide experimental evidence that, as predicted (38, 46, 47), the GLUT2 transporter is an essential component of the astrocyte glucodetection mechanism. Furthermore, the GLUT2 transporter may be operating as a “transceptor” because it appears that GLUT2 activation could be linked to ER calcium release through the activation of PLC and the ryanodine sensitive CICR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All experimental procedures were conducted with the approval of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed according to the guidelines set forth by the National Institutes of Health. Long-Evans rats of either sex (16 females; 10 males; body weight between 250 and 450 g; age range 3–6 mo) obtained from the Pennington Biomedical Research breeding colony were used in these studies. Animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room under 12:12-h light-dark cycle and provided water and food ad libitum.

Live Cell Calcium Imaging

Prelabeling of NST neurons and astrocytes and preparation of ex vivo hindbrain slices.

Animals were deeply anesthetized with urethane [1.5g/kg ip; ethyl carbamate, Sigma; which readily washes out of ex vivo slices (27)] and placed in a stereotaxic frame. Using aseptic technique, the occipital plate of the skull was removed to expose the medullary brain stem. A micropipette (30-μm tip diameter) filled with 0.4% Cal-520 (AAT Bioquest), 0.3% sulforhodamine 101 (SR101; Sigma Chemical), and 10% pluronic-DMSO (F-127, Invitrogen) in normal Krebs solution (recipe below) was directed toward the medial solitary nucleus using a stereotaxic carrier. Four injections (40 nL each) of the Cal-520/SR101 solution were made unilaterally into the NST at the level of calamus and 0.2, 0.4, and 0.6 mm anterior to calamus; all at a depth of 300 μm below the surface. This injection pattern labeled the entire ipsilateral medial NST.

After these intra-NST injections, a 60-min interval was allowed for adequate dye uptake; the anesthetized rat was decapitated and the brain stem was quickly harvested. The caudal brain stem was glued to an aluminum block and placed in cold (~4°C) carboxygenated (95% O2-5% CO2) cutting solution (see Perfusion solutions). Coronal sections (300 μm thick) were cut through the medulla using a Leica VT1200 tissue slicer equipped with a sapphire knife (Delaware Diamond Knives). The NST is easily identified in these slices due to its lack of myelin; 4–5 slices containing NST were collected from each animal and placed in normal Krebs solution (recipe below), which was bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2 and maintained at a constant temperature of 29°C. Slices were allowed to equilibrate to these conditions for an hour before imaging.

Imaging of NST astrocytes.

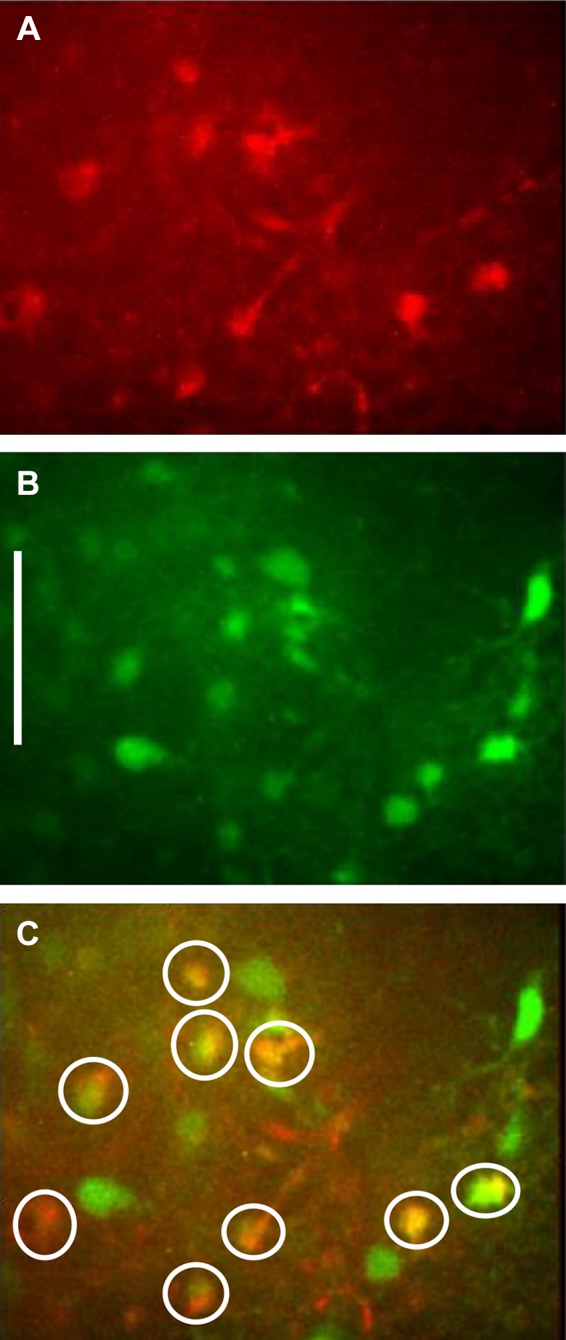

Cal-520 is a calcium reporter dye that labels both neurons and glia, whereas SR101 labels only astrocytes (50, 56) but does not interfere with calcium reporter dye fluorescence (31). Prelabeling with Cal-520 and SR101 allows for discrimination of astrocytes and neurons at the cellular level by comparing images captured using the 488-nm and 561-nm laser lines. At 488 nm, both astrocytes and neurons (i.e., prelabeled with Cal-520) will appear green; at 561 nm, only astrocytes will also appear red. This prelabeling technique made it possible to easily discriminate astrocytes from neurons in a slice preparation which is important given the similarity in size of NST neuronal and astrocytic cell bodies (Fig. 1).

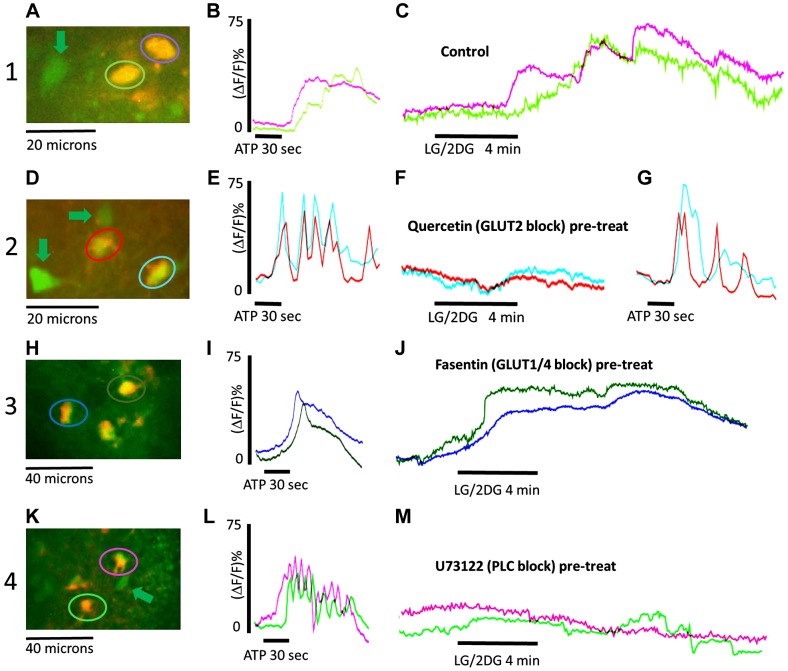

Fig. 1.

Prelabeling with Cal-520 and SR101 allows for discrimination of astrocytes and neurons at the cellular level by comparing images captured using the 488-nm and 561-nm laser lines. A: at 561 nm, only astrocytes (prelabeled with SR101) will appear red. B: at 488 nm, both astrocytes and neurons (i.e., prelabeled with Cal-520) will appear green. C: these dual exposure images confirm the cell types being recorded. Dual labeled cells (astrocytes) are circled in white. The green cells are neurons. Scale bar = 30 μm.

Cal-520/SR101 prelabeled slices were transferred to a custom imaging chamber (70). The recording chamber was continuously perfused at a rate of 2.5 mL/min with normal Krebs (or experimental solution) maintained at a temperature of 33°C. Solutions were carbogenated in individual plastic cups; solenoid valves (ValveLink 8; Automate Scientific, San Francisco, CA) were used to select perfusates to be directed to the slice. Perfusates were delivered through a manifold (Small Parts, Miami Lakes, FL) to a roller pump (Dynamax, Rainin, Woburn, WA) to switch between the normal bathing solution and the challenge or experimental solutions without interruption to perfusion of the slice being monitored. [Additional details about the recording chamber can be found in (72).]

Hindbrain slices were viewed with a Zeiss Axioskop two fixed stage microscope equipped with normal epifluorescence optics as well as with a Yokogawa CSU21 laser confocal scan head and Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera. Prelabeled cells of interest were selected visually with the epifluorescence optics and then confocal images were captured with the ORCA-ER at the rate of one frame per second.

Experimental design.

Once in the recording chamber, hindbrain slices were perfused with normal Krebs solution for a minimum of 10 min. Dual exposure images (i.e., 488 and 591 nm) were collected just before each experimental trial to confirm the cell types being recorded (Fig. 1). All slices were then challenged with a cocktail of 100 μM ATP and 500 μM glutamate to determine which astrocytes in the field were viable; i.e., capable of generating calcium signals (71, 83).

Slices were then challenged with the low-glucose/glucoprivic challenge (recipe below; Krebs solution except 1 mM glucose concentration plus 4 mM 2-deoxy-d-glucose) for 4 min. Changes in intracellular calcium concentrations within Cal-520-prelabeled NST astrocytes and NST neurons in response to different stimuli were recorded using the 488-nm laser line to excite the Cal-520. Increases in intracellular calcium concentrations are reflected as an increase in fluorescence and are indicative of increased cellular activity. During experimental trials, time-lapse images of mixed fields of NST astrocytes and neurons were monitored for their responses to the glucoprivic conditions. Additional prelabeled hindbrain slices were first exposed to one of several transporter or receptor blockers (described in Drug challenges) before the glucoprivic challenge. Time-lapse laser confocal images of changes in intracellular calcium levels of both astrocytes and neurons in response to challenges were captured with the ORCA-ER at a rate of one frame per second.

Perfusion solutions.

All solutions were freshly prepared on the day of the experiment. Cutting solution contained 110 mM choline chloride, 25 mM NaHCO3, 2.5 mM KCl, 7 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM glucose, and 0.5 mM CaCl2·2H2O. Normal Krebs solution contained 124 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 3.0 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 1.5 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM glucose, and 1.5 mM CaCl2·2H2O. Composition of the low-glucose/glucoprivic challenge solution was identical to the normal Krebs solution with the exception that glucose concentration was only 1 mM with the addition of 4 mM 2DG (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (71).

Drug challenges.

Ten minutes after the ATP/glutamate viability test, one of the following pretreatments were applied to the slice chamber for 10 min: 1) control (10 min of normal Krebs perfusion, no pretreatment); 2) quercetin, a selective blocker of the GLUT2 transporter [50 μM (40)]; 3) phlorizin, a nonselective blocker of sodium-glucose cotransporters [50 μM (40)]; 4) fasentin, a selective blocker of GLUT1/4 transporters [20 μM (87)]; 5) U73122, a selective antagonist of PLC [10 μM (30)]; 6) U73343, an inactive form of U73122 [10 μM (41)]; 7) 2APB, a blocker of intracellular ER IP3 receptors [100 μM (11)]; 8) dantrolene, a blocker of ryanodine channel mediated ER calcium release [10 μM (90)]; or 9) low extracellular calcium (0.2 mM).

Pretreatments were immediately followed by a 4-min glucoprivic challenge of 1 mM glucose + 4 mM 2DG (LG/2DG); a combination previously shown to produce a robust activation of NST astrocytes (71).

Data and statistical analysis of cellular responses of NST astrocytes.

Several previous studies have shown that NST neuron activation following glucopenia is due to the actions of primary astrocyte glucosensors and subsequent purinergic gliotransmission (71). The present study was focused exclusively on astrocyte transduction mechanisms and only astrocyte regions of interest (ROIs) were subjected to postexperiment data analysis. Nikon Elements AR software was used to analyze the confocal live cell fluorescent signals in astrocytes as previously described (49). Individual astrocytes were designated as ROIs and their fluorescence signal over time was captured. Background fluorescence was subtracted from the cellular fluorescence signal. The relative changes in cytoplasmic calcium in the cells were expressed as changes in fluorescence [(ΔF/F)%], where F is the intensity of the baseline fluorescence signal before stimulation, and ΔF is the difference between the peak fluorescence intensity and the baseline signal of each individual ROI.

Data from Cal-520 plus SR101 prelabeled, viable NST astrocytes (n = 450) were evaluated for statistical significance via one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett’s multiple comparison post hoc tests. Significance was set at P < 0.05. All data are reported as means ± SE.

Coimmunoprecipitation Assay

Based on our previous results, we predicted that a general property of GLUT2 is a functional linkage with PLC activation through a “transceptor” mechanism. Given that PLC is normally triggered by G-protein Gαq, we conducted in vitro coimmunoprecipitation studies to determine if recombinant Gαq also binds to recombinant GLUT2.

Five micrograms each of recombinant human Gαq protein (“GNAQ,” Abcam cat. no. ab132889) and recombinant human GLUT2 protein (Novus Biologicals cat. no. H00006514-P01) proteins were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Five micrograms of IgG or anti-GNAQ antibody (rabbit polyclonal; Abcam cat. no. ab75825) were added and samples were incubated overnight at 4◦C with end-over-end rotation. Immunoprecipitation of antigen-antibody complexes was performed by incubation with 20 μL Protein G Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher cat. no. 10004D) for 1 h at 4◦C. The magnetic beads binding to the antigen-antibody complexes were washed twice for 5 min each at 4°C with 0.5 mL of immunoprecipitation buffer [0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris (pH 8)]. After the buffer was removed, beads containing immunoprecipitation complexes were resuspended in 20 μL of NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Thermo Fisher cat. no.NP0007). Samples were denatured, separated by SDS-PAGE on 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Thermo Fisher cat. no.NP0321), and transferred to a PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked for 15 min at room temperature using Membrane Blocking Solution (Thermo Fisher cat. no. 000105), followed by overnight incubation at 4◦C with an anti-GLUT2 antibody (mouse monoclonal; Abcam cat. no. ab85715). Excess (nonbound) antibodies were removed by decanting, and membranes were washed in Tris-buffered saline three times for 5 min each time. Membranes were incubated with secondary antibody (HRP-linked anti-mouse IgG; Cell Signaling Technology cat. no. 7076) for 2 h at room temperature with rotation. Secondary antibody was removed, and membranes were washed in Tris-buffered saline three times for 5 min each time. Chemiluminescence detection was performed using a ChemiDoc Imaging system (Bio-Rad).

RESULTS

Live Cell Imaging

Astrocytes are readily identified in the ex vivo slice preparation as described before (49, 71). “Viable astrocytes” are defined as those identified cells that responded to the ATP-glutamate cocktail with a minimum increase of 10% in calcium fluorescence levels compared with baseline levels. Only viable astrocytes were included in data analyses.

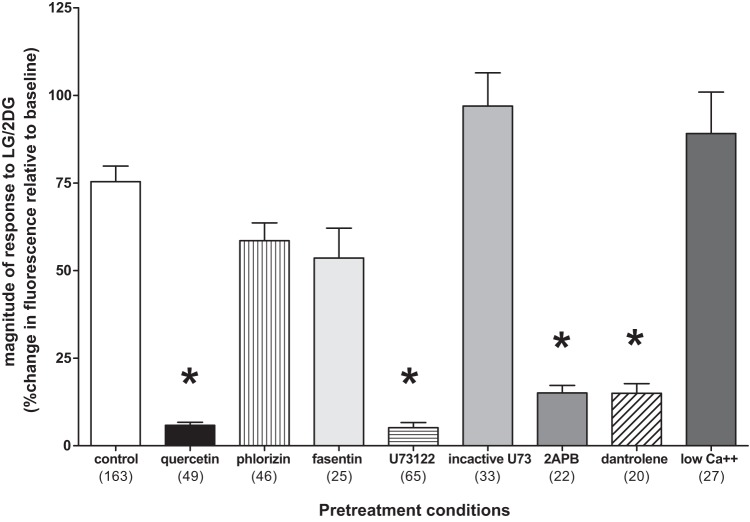

The “control” LG/2DG challenge yielded robust responses in viable astrocytes (Fig. 2). In contrast, pretreatment of hindbrain slices with the selective GLUT2 transporter blocker (quercetin) produced a nearly complete block of the LG/2DG effect, whereas the other transport antagonists phlorizin (SGLT) and fasentin (GLUT1/4) were not effective. Pretreatment with the PLC antagonist (U73122) completely blocked the subsequent effects of the LG/2DG challenge, whereas the inactive enantiomer (U73343) was without effect. Additionally, 2APB (an IP3 antagonist) also blocked the LG/2DG effect as did the ER ryanodine receptor antagonist, dantrolene. Low calcium Krebs did not eliminate the astrocyte response to LG/2DG (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Representative screenshots of identified astrocytes (color-coded encircled) and neurons (green arrows) adjacent to plots of the calcium-induced fluorescence signals over time evoked in these identified astrocytes by exposure to either ATP (viability test) and a glucoprivic [low glucose/2-deoxyglucose (LG/2DG)] challenge. Magnitudes of response to these challenges are reflected in the percent change in fluorescence of each individual astrocyte. Row 1 control conditions: A: screenshot of identified (double-labeled) astrocytes. B: adjacent trace shows the astrocytic responses to short exposure to ATP. C: the subsequent trace is representative of the robust astrocytic responses (color coded to the astrocytes encircled in A) to glucoprivic challenge under control conditions. Row 2 quercetin [glucose type 2 transporter (GLUT2) block] pretreatment: D: screenshot of identified astrocytes. E: adjacent trace are the astrocytic responses to short exposure to ATP. F: the subsequent trace is representative of diminished astrocytic responses (color coded to the astrocytes encircled in D) to glucoprivic challenge following pretreatment of slice with GLUT2 antagonist, quercetin. G: followed by another challenge with ATP to verify that the astrocytes were still viable after the GLUT2 blockade. Results following pretreatment with 2APB, U73122, and dantrolene are qualitatively similar (not shown here), and this is reflected in the summary data in Fig. 3. Row 3 fasentin (GLUT1/4 block) pretreatment: H: screenshot of identified astrocytes. I: adjacent trace showing astrocytic response to short exposure to ATP. J: astrocytes (color coded to cells encircled in H) response to LG/2DG challenge is not different from control. Row 4 U73122 (PLC block) pretreatment: K: screenshot of identified astrocytes. L: adjacent trace shows astrocytic response to short ATP exposure. M: U73122 blocks the effect of glucoprivic challenge on the identified astrocytes (color coded in K). Note that the ATP effect is mediated through a P2Y receptor that is also dependent on phospholipase C (PLC), so those effects are also blocked by U73122 (15) (null trace not shown).

Fig. 3.

Averaged magnitude of changes in fluorescence due to intracellular calcium fluxes in hindbrain astrocytes in response to glucoprivic challenge after specific pretreatment conditions (number of astrocytes studied per each group is noted in parentheses). Exposure of astrocytes in hindbrain slices to the various pretreatment conditions produced significant differences in response to subsequent glucoprivic challenge. The “control” low glucose/2-deoxyglucose (LG/2DG) challenge yielded robust responses in viable astrocytes. In contrast, pretreatment of hindbrain slices with the selective glucose type 2 transporter (GLUT2) transporter blocker (quercetin) produced a nearly complete block of the LG/2DG effect, whereas the other transport antagonists phlorizin (SGLT) and fasentin (GLUT1/4) were not effective. Pretreatment with the phospholipase C (PLC) antagonist (U73122) completely blocked the subsequent effects of the LG/2DG challenge, whereas the inactive enantiomer (U73343) was without effect. Additionally, 2APB (an IP3 antagonist) also blocked the LG/2DG effect as did the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) ryanodine receptor antagonist, dantrolene. Low calcium Krebs did not eliminate the astrocyte response to LG/2DG. An overall one-way ANOVA yielded F8,441 = 33.11; P < 0.0001; Dunnett’s posttests: *P < 0.05.

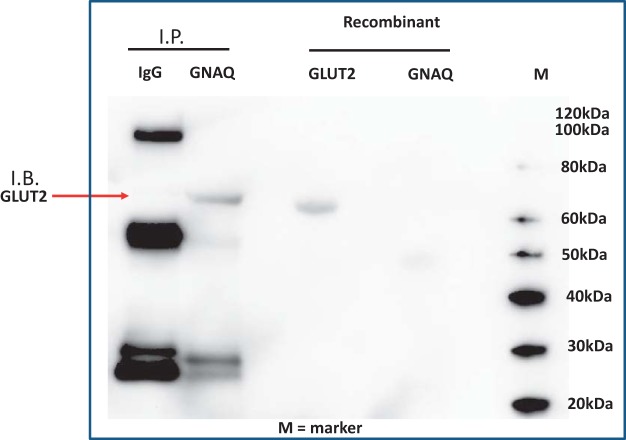

Coimmunoprecipitation Assay

Recombinant GNAQ and GLUT2 proteins were incubated together to determine if physical interaction was possible. We found that GLUT2 could be recovered by immunoprecipitation with an antibody to GNAQ after 30 min of coincubation (Fig. 4). Conducting the reverse coimmunoprecipitation yielded similar results (data not shown). Thus, using this proof of principle of coimmunoprecipitation assay, these two proteins are capable of physical interaction.

Fig. 4.

Detection of a physical interaction between glucose type 2 transporter (GLUT2) and recombinant human Gαq protein (GNAQ). Recombinant GLUT2 and GNAQ were incubated at room temperature for 30 m followed by overnight immunoprecipitation (IP) with antibodies against either normal mouse serum (IgG) or GNAQ. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, detected by immunoblotting (IB) with an antibody targeting GLUT2. The experiment was repeated on three separate occasions. The red arrow indicates detection of GLUT2 after immunoprecipitation using the GNAQ antibody.

DISCUSSION

Our results reinforce the idea that GLUT2 is a necessary component of the astrocyte low-glucose detection mechanism. Specifically, the potent and selective GLUT2 blocker (quercetin) suppressed astrocyte responsiveness to glucoprivation. In contrast, neither the GLUT1/4 antagonist (fasentin) nor the SGLT blocker (phlorizin) affected these astrocytic responses (Fig. 3). Additionally, astrocyte cytoplasmic calcium signals normally generated after a low-glucose challenge were blocked by the PLC antagonist (U73122; but not the inactive form of U73343) and by the ER IP3 receptor blocker (2APB). Together, these results suggest that astrocyte GLUT2 detection of the low-glucose state involves a coupling to ER calcium release through a PLC mechanism. These data further support the notion of GLUT2 as a transceptor put forward by Stolarczyk et al. (78, 79). Finally, glucoprivic activation of ER calcium release was reduced by a ryanodine channel antagonist (dantrolene). However, the glucoprivation-induced calcium wave produced in astrocytes is probably not immediately dependent on the flux of extracellular calcium to the cytoplasm since a 10-fold reduction in the calcium content of the Krebs perfusate had no effect on the astrocyte calcium response to low glucose (Fig. 3).

Glucose detection and coupling to mechanisms regulating cellular excitability have been elegantly described for the pancreatic β cell (54, 74). The critical element of this mechanism is a specialized transmembrane glucose transporter, GLUT2 (38, 46), which is a reversible carrier in that it will transport glucose down a concentration gradient in either direction across the cell membrane. GLUT2 operates at a high relative volume but with a low affinity compared with other hexose transporters, which makes the GLUT2 transporter the critical discriminator of physiological glucose concentrations (38). The physiological consequences of these parameters are that glucose concentrations are rapidly equalized between the extracellular and intracellular compartments for cells that possess a significant number of GLUT2 transporters. Since the GLUT2 transporter is bidirectional, any reduction in extracellular glucose would be rapidly reflected in a reduction in intracellular glucose available for the synthesis of ATP, hence a reduction in β cell insulin secretion (38).

The importance of GLUT2 to physiological glucose detection makes it a convenient marker for the identification of putative glucose-sensing cells. Previous transgenic studies (46, 47) have demonstrated that CNS astrocytes, probably localized to the hindbrain, are essential components of the CRR glucodetection mechanism. The conclusion from these groundbreaking studies was that astrocytes are key elements in the direct sensing of declines in glucose (38, 46, 47): a view supported by recent investigations from our laboratory (49, 71, 73) as well as suggested by earlier studies (89). The present study supports the idea that astrocytic expression of GLUT2 is necessary for proper glucose counter-regulation (46). Figure 2 shows that the normally robust response of astrocytes to produce an increase in intracellular calcium in response to glucoprivation is blocked by 50 μM quercetin, a selective blocker of the GLUT2 transporter (40).

Note that quercetin has been associated with a bewildering array of transduction and transcriptional events related to the suppression of cell growth, especially of transformed cells. This is in addition to its well-known role as a reactive oxygen scavenger (37). However, those effects of quercetin require at least an hour or two to manifest, which is significantly longer than the duration of the current experiments. The transport suppression by quercetin for the GLUT2 transporter is highly selective and is essentially instantaneous (40).

Additionally, if GLUT2 were a critical factor in the generation of a calcium signal in astrocytes, then one might expect that blockade of GLUT2 with quercetin might also produce a calcium signal. However, pilot studies with quercetin alone (data not shown) demonstrated that this reagent produced no change in resting astrocyte calcium. Therefore, quercetin acting as a GLUT2 blocker will have the immediate effect of stopping glucose flux through the transporter and “clamping” the intracellular concentration. If GLUT2 operates as a “transceptor” and flux through the transporter is the important feature of its function, then quercetin should not have an effect of its own.

It remained to be explained how the activity of the GLUT2 transporter in astrocytes can lead to the increase in intracellular calcium following glucoprivation. Others have reported that glucose restriction in cultured astrocytes causes an increase in astrocytic cytoplasmic calcium signals (8, 35). Similar to our earlier studies (49), this increase in cytoplasmic calcium is reversed with the restoration of normal levels of glucose in the perfusion bath. Astrocytes are highly dependent on glycolysis for ATP production; removal of glucose or blocking glucose utilization may rapidly starve astrocytes of glucose for ATP production. With impaired glycolysis and subsequent low ATP following low extracellular glucose availability, the calcium-ATPase pump in the ER of astrocytes fails and ER calcium is released to the cytoplasm (8, 35). Although this mechanism cannot yet be ruled out, it is unlikely that this mechanism is responsible for the cytoplasmic calcium signal seen by our laboratory in in situ NST astrocytes. One reason for doubt is that the response time for astrocytes in our NST slice preparation (49) is less than one-tenth that reported for cultured hippocampal astrocytes (8, 35). That is, our data consistently show that the presentation of a glucoprivic stimulus is followed by an increase in cytoplasmic calcium within ~5 min; the ATP starvation mechanism responsible for elevating calcium in hippocampal astrocytes takes about 2 h (8).

Rapid signaling of glucose status in intact hindbrain astrocytes could involve the action of a GLUT2 -glucose “transceptor,” i.e., a protein that functions as both a transporter and receptor (34, 69, 81). Such constructs are common in yeast, and the coupling of nutrient transporters to G protein transduction mechanisms are important for the rapid metabolic adaptations these organisms must engage to deal with rapid changes in nutrient availability (34). In vertebrates, a GLUT2-based transceptor could detect changes in extracellular glucose concentration and then rapidly initiate a calcium-based transduction event. This system could function somewhat like a membrane G protein-based receptor linked to ER calcium release. Transgenic mice generated to knock down a GLUT2-intracellular loop domain of the sort likely to engage G protein transduction mechanisms yielded animals that demonstrated an inability to detect glucose but left the GLUT2-dependent glucose transport unaffected (78, 79).

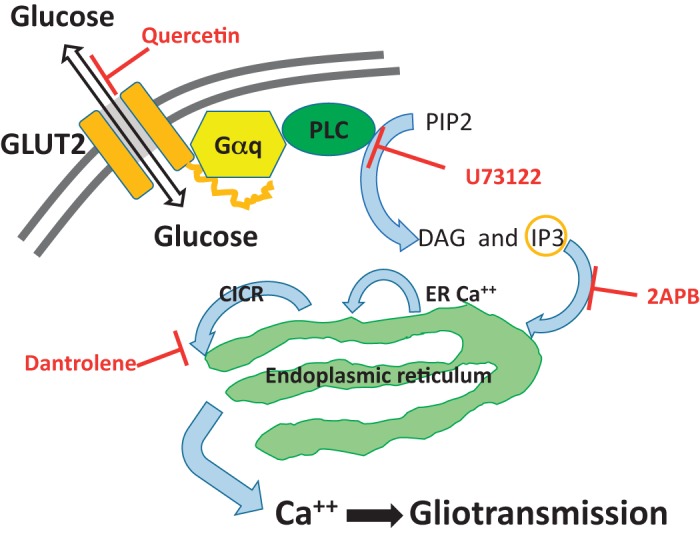

Astrocyte cytoplasmic calcium signals generated after a low-glucose challenge were blocked by the PLC antagonist U73122 and by the ER IP3 receptor blocker 2APB. This suggests that astrocyte GLUT2 detection of the low-glucose state involves a coupling to ER calcium release through a PLC mechanism. Our results showing that the glucoprivic activation of ER calcium release was also reduced by a ryanodine channel antagonist (dantrolene) suggests that the astrocyte response is similar to that reported for the effects of ionomycin (53) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Based on data from the current study, this cartoon representation proposes a hypothetical mechanism of astrocytic transduction of glucoprivic information into gliotransmission.

Although ionomycin was first thought to provoke the physiochemical transport of extracellular calcium to the cytoplasm, it happens that in the astrocyte, the mechanism is more complex. Ionomycin in astrocytes triggers a two-component release of ER calcium: one dependent on PLC and IP3 and the other on ER ryanodine channels. It is thought that the IP3 triggers the initial ER calcium release and that this, in turn, produces a larger CICR via activation of ryanodine channels. The glucoprivation-induced calcium wave produced in hindbrain astrocytes is probably not immediately dependent on the flux of extracellular calcium to the cytoplasm because a 10-fold reduction in the calcium content of the Krebs perfusate had no effect on the astrocyte calcium response to low glucose (Fig. 3).

Although the foregoing pharmacological and imaging data produce a compelling case for a GLUT2 transceptor mechanism linked to ER calcium release through PLC, it is minimally necessary to demonstrate that GLUT2 is coupled with known protein activators of PLC, such as the Gαq GTPase (48). A coimmunoprecipitation assay indeed shows that recombinant GLUT2 and Gαq are capable of physical interaction. This initial work provides a solid basis for future mechanistic studies of the connection between the GLUT2 transporter activity and downstream mechanisms connected with ER calcium signal generation.

At some point it will be necessary to connect cell body calcium signal generation produced by glucopenia with end foot transmission mechanisms. Gliotransmission is, like neurotransmission, carried out at the terminal interface between afferent and efferent cells. Although it is very likely that calcium signals generated within the NST astrocytes in response to glucopenia are propagated to end feet, and that signal triggers what is likely to be purinergic gliotransmission (69, 71, 73), the details still need to be established with certainty. This is because endfoot activation does not always follow calcium changes in the astrocyte cell body (36, 63). Although our current study does not specifically address this issue, our previously published work (see Fig. 8 in Ref. 69) clearly shows that fields of astrocyte cell bodies in the NST and their attendant gliopile are robustly activated by a glucopenic challenge.

Perspectives and Significance

Physiological significance of astrocyte parameter sensing, calcium signaling, and gliotransmission.

Historically, astrocytes have been thought to play a passive role in the control of brain function. That is, the astrocyte was viewed as principally responsible for maintaining the extracellular nutrient, metabolite, and ionic environment for neurons, while also working to recycle released neurotransmitters and their break-down products as metabolic fuel for neurons. Additionally, the astrocyte provides mechanical support, literally providing the “glue” that holds the nervous system together. This view is essentially the same as that proposed by Cajal in his Histologie du système nerveux de l'homme & des vertébrés of 1909 (14). Although the astrocyte is certainly responsible for these basic functions, the role of the glial cell as an active participant in CNS signaling and control has undergone a recent and dramatic expansion (29, 84). The relatively recent discovery of glial-neural interactions that could modify synaptic strength or initiate changes in neuronal excitability (26, 60, 61) were revolutionary, requiring a modern reexamination of the role of glial cells in brain function (6, 77).

It now seems likely that the role of glia in regulating neuronal function is more conditional and circumstantial than had been conceived initially. Some of the earlier reports of functional glial-neural interactions involved strong activation of astrocytes in combined glial-neural culture systems, manipulations that could bias the preparation in favor of a demonstration of a glial effect on neurotransmission. A controversial follow-up study in the mouse strongly suggested that genetic manipulation of putative glial signaling pathways (and intrinsic glial “excitability”) had no significant effects on hippocampal neurotransmission (6). The review article by Savtchouck and Volterra (75), however, provides a very measured and clear discussion on the active transfer of information from astrocytes to neurons and the involvement of Ca2+ in the process. Even so, there is still a considerable debate centered on the inability of results obtained in cortical/hippocampal in vitro culture or transgenic models to be replicated in in vivo models.

Much of the controversy concerning the physiological significance of glial-neural interactions is focused on cortex and hippocampus (6, 21, 77). However, there seems to be no such controversy regarding the involvement of astrocytes as chemosensors in other parts of the brain, particularly the hindbrain. A diverse literature has emerged showing that autonomic functions controlled by neuronal circuits in the medulla are powerfully regulated by inputs from chemosensing glial cells. Astrocytes, as they form the blood-brain barrier, are in the ideal position to provide autonomic control circuitry with essential chemosensor data. Indeed, there is nearly complete agreement between ex vivo imaging and in vivo whole animal studies supporting the importance of glial parameter detection to autonomic control. Glial detection of hypoglycemia, hypoxia, hypercapnia, markers of trauma (e.g., thrombin), and immune activation clearly regulate the functions of adjacent autonomic control neurons involved in control of gastric motility, respiration, and cardiovascular and glucoregulatory control (1, 19, 22–24, 31, 32, 43, 51, 62, 69). Furthermore, autonomic glial-neural interactions are not unidirectional. There is also evidence to suggest that the responsiveness of “autonomic” astrocytes in the hindbrain can be regulated by visceral afferent neuronal inputs (2, 50). Astrocytes and their associated hindbrain gliotransmission mechanisms are emerging as full partners with neurons in exerting integrated control over critical autonomic functions (5, 69).

Transceptors and glucose sensing by astrocytes.

Astrocytes in the hindbrain perform important functions as chemosensors. The anatomical relationships between the vasculature, glial cells, and neurons suggest that astrocytes occupy a “gateway” position from the perspective of monitoring material, especially nutrient, flux into the brain. Glial cells, including astrocytes, literally form vascular-neuropil and ventricular-neuropil diffusion barriers. But these cells also possess transport mechanisms that allow the penetration of even large-sized signal molecules, such as cytokines into the neuronal matrix (58). Additionally, small nutrient molecules, such as glucose, ions, and blood gases access the neuropil by passing through or around astrocytes. This arrangement places glial cells in an ideal position to detect the fluxes of physiologically critical solutes and exert early influence on adjacent neural systems dedicated to homeostatic regulation of these agents.

Work from 20 years ago (89) to the present suggests that astrocytes are important sensors of low glucose availability. In turn, astrocytes apparently relay the glucopenic signal to CA neurons in the hindbrain that organize CRR reflex responses via purinergic agonists, such as ATP or adenosine (71). Evidence presented here supports the idea that astrocytes utilize a transceptor mechanism for low glucose sensing that is common to yeast but apparently rare in vertebrates. The proposed astrocyte mechanism bears some similarity to the vertebrate sweet taste detector in that the transmembrane sensor is probably an evolutionary derivative of a transporter linked by G proteins to a PLC-ER calcium signal generator. Of course, the novel feature of the astrocyte sensor is that it causes a robust calcium signal when a nutrient is diminished. Although data from the present study suggest that a GLUT2-Gαq-PLC mechanism is triggered in glucopenic sensitive astrocytes, additional work remains to unravel the molecular basis for the trigger mechanism.

There are several studies suggesting that astrocytes are perhaps the dominant sensors responsible for the detection of low-glucose emergencies. For example, Marty et al. (46) showed that elimination of the GLUT2 transporter in astrocytes eliminated CRR, a finding that certainly suggests primacy. Our recent study (73) demonstrated that local (fourth ventricular) blockade of dorsal medullary astrocyte signaling substantially reduced (but did not completely eliminate) the CRR-mediated hyperglycemia triggered by systemic 2DG. However, there is also strong evidence that peripheral visceral afferent inputs [e.g., carotid bodies (39, 86)] and potential glucose-sensitive neurons in the NST and VLM (66, 67) are sufficient to activate CRRs. Although seeming paradoxical, astrocyte and non-astrocyte glucodetection controls of CRRs are not mutually exclusive. The apparent primacy of astrocyte glucose sensing may be overestimated by the fact that CRR control circuit function (indeed, all neural circuitry) may be critically dependent on astrocytes for the maintenance of basic functionality. So, peripheral and CNS glucopenia sensor input to CRR-relevant hindbrain neurons, although important, may not be effective unless paired with similar signals from adjacent astrocytes. Astrocyte gating of hindbrain synaptic interactions are proven features of astrocyte involvement in autonomic control (20, 29, 45, 59, 83).

GRANTS

We acknowledge funding support we received for the work described in this paper from National Institutes of Health Grants NS60664 and DK108765 and The John S. McIlhenny Professorship.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.C.R., S.J.B., J.J.C., S.R., and G.E.H. conceived and designed research; R.C.R., S.J.B., J.J.C., and G.E.H. performed experiments; R.C.R., S.J.B., J.J.C., and G.E.H. analyzed data; R.C.R., S.J.B., J.J.C., and G.E.H. interpreted results of experiments; R.C.R., S.J.B., J.J.C., and G.E.H. prepared figures; R.C.R. and G.E.H. drafted manuscript; R.C.R., S.R., and G.E.H. edited and revised manuscript; R.C.R., S.J.B., J.J.C., S.R., and G.E.H. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accorsi-Mendonça D, Bonagamba LGH, Machado BH. Astrocytic modulation of glutamatergic synaptic transmission is reduced in NTS of rats submitted to short-term sustained hypoxia. J Neurophysiol 121: 1822–1830, 2019. doi: 10.1152/jn.00279.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accorsi-Mendonça D, Zoccal DB, Bonagamba LG, Machado BH. Glial cells modulate the synaptic transmission of NTS neurons sending projections to ventral medulla of Wistar rats. Physiol Rep 1: e00080, 2013. doi: 10.1002/phy2.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adachi A, Kobashi M, Funahashi M. Glucose-responsive neurons in the brainstem. Obes Res 3, Suppl 5: 735S–740S, 1995. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adachi A, Shimizu N, Oomura Y, Kobáshi M. Convergence of hepatoportal glucose-sensitive afferent signals to glucose-sensitive units within the nucleus of the solitary tract. Neurosci Lett 46: 215–218, 1984. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agulhon C, Boyt KM, Xie AX, Friocourt F, Roth BL, McCarthy KD. Modulation of the autonomic nervous system and behaviour by acute glial cell Gq protein-coupled receptor activation in vivo. J Physiol 591: 5599–5609, 2013. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.261289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agulhon C, Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD. Hippocampal short- and long-term plasticity are not modulated by astrocyte Ca2+ signaling. Science 327: 1250–1254, 2010. doi: 10.1126/science.1184821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrew SF, Dinh TT, Ritter S. Localized glucoprivation of hindbrain sites elicits corticosterone and glucagon secretion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R1792–R1798, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00777.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnold S. Estrogen suppresses the impact of glucose deprivation on astrocytic calcium levels and signaling independently of the nuclear estrogen receptor. Neurobiol Dis 20: 82–92, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balfour RH, Hansen AM, Trapp S. Neuronal responses to transient hypoglycaemia in the dorsal vagal complex of the rat brainstem. J Physiol 570: 469–484, 2006. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.098822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bohland M, Matveyenko AV, Saberi M, Khan AM, Watts AG, Donovan CM. Activation of hindbrain neurons is mediated by portal-mesenteric vein glucosensors during slow-onset hypoglycemia. Diabetes 63: 2866–2875, 2014. doi: 10.2337/db13-1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bootman MD, Collins TJ, Mackenzie L, Roderick HL, Berridge MJ, Peppiatt CM. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) is a reliable blocker of store-operated Ca2+ entry but an inconsistent inhibitor of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release. FASEB J 16: 1145–1150, 2002. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0037rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briski KP, Ibrahim BA, Tamrakar P. Energy metabolism and hindbrain AMPK: regulation by estradiol. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 17: 129–136, 2014. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2013-0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bulatao E, Carlson A. Contributions to the physiology of the stomach: influence of experimental changes in blood sugar level on gastric hunger contractions. Am J Physiol 69: 107–115, 1924. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1924.69.1.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cajal SRy Histology of the Nervous System. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centemeri C, Bolego C, Abbracchio MP, Cattabeni F, Puglisi L, Burnstock G, Nicosia S. Characterization of the Ca2+ responses evoked by ATP and other nucleotides in mammalian brain astrocytes. Br J Pharmacol 121: 1700–1706, 1997. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cryer PE. Symptoms of hypoglycemia, thresholds for their occurrence, and hypoglycemia unawareness. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 28: 495–500, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dallaporta M, Bonnet MS, Horner K, Trouslard J, Jean A, Troadec JD. Glial cells of the nucleus tractus solitarius as partners of the dorsal hindbrain regulation of energy balance: a proposal for a working hypothesis. Brain Res 1350: 35–42, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dallaporta M, Himmi T, Perrin J, Orsini JC. Solitary tract nucleus sensitivity to moderate changes in glucose level. Neuroreport 10: 2657–2660, 1999. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199908200-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erlichman JS, Leiter JC, Gourine AV. ATP, glia and central respiratory control. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 173: 305–311, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fellin T, Pascual O, Haydon PG. Astrocytes coordinate synaptic networks: balanced excitation and inhibition. Physiology (Bethesda) 21: 208–215, 2006. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00161.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiacco TA, Agulhon C, Taves SR, Petravicz J, Casper KB, Dong X, Chen J, McCarthy KD. Selective stimulation of astrocyte calcium in situ does not affect neuronal excitatory synaptic activity. Neuron 54: 611–626, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Funk GD. The ‘connexin’ between astrocytes, ATP and central respiratory chemoreception. J Physiol 588: 4335–4337, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.200196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gourine AV, Kasparov S. Astrocytes as brain interoceptors. Exp Physiol 96: 411–416, 2011. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.053165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gourine AV, Kasymov V, Marina N, Tang F, Figueiredo MF, Lane S, Teschemacher AG, Spyer KM, Deisseroth K, Kasparov S. Astrocytes control breathing through pH-dependent release of ATP. Science 329: 571–575, 2010. doi: 10.1126/science.1190721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guillemain G, Loizeau M, Pinçon-Raymond M, Girard J, Leturque A. The large intracytoplasmic loop of the glucose transporter GLUT2 is involved in glucose signaling in hepatic cells. J Cell Sci 113: 841–847, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halassa MM, Haydon PG. Integrated brain circuits: astrocytic networks modulate neuronal activity and behavior. Annu Rev Physiol 72: 335–355, 2010. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hara K, Harris RA. The anesthetic mechanism of urethane: the effects on neurotransmitter-gated ion channels. Anesth Analg 94: 313–318, 2002. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200202000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassel B, Paulsen RE, Johnsen A, Fonnum F. Selective inhibition of glial cell metabolism in vivo by fluorocitrate. Brain Res 576: 120–124, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90616-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Astrocyte control of synaptic transmission and neurovascular coupling. Physiol Rev 86: 1009–1031, 2006. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermann GE, Nasse JS, Rogers RC. Alpha-1 adrenergic input to solitary nucleus neurones: calcium oscillations, excitation and gastric reflex control. J Physiol 562: 553–568, 2005. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.076919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hermann GE, Rogers RC. TNF activates astrocytes and catecholaminergic neurons in the solitary nucleus: implications for autonomic control. Brain Res 1273: 72–82, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hermann GE, Van Meter MJ, Rood JC, Rogers RC. Proteinase-activated receptors in the nucleus of the solitary tract: evidence for glial-neural interactions in autonomic control of the stomach. J Neurosci 29: 9292–9300, 2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6063-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hermann GE, Viard E, Rogers RC. Hindbrain glucoprivation effects on gastric vagal reflex circuits and gastric motility in the rat are suppressed by the astrocyte inhibitor fluorocitrate. J Neurosci 34: 10488–10496, 2014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1406-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holsbeeks I, Lagatie O, Van Nuland A, Van de Velde S, Thevelein JM. The eukaryotic plasma membrane as a nutrient-sensing device. Trends Biochem Sci 29: 556–564, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kahlert S, Reiser G. Requirement of glycolytic and mitochondrial energy supply for loading of Ca2+ stores and InsP(3)-mediated Ca2+ signaling in rat hippocampus astrocytes. J Neurosci Res 61: 409–420, 2000. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khakh BS, McCarthy KD. Astrocyte calcium signaling: from observations to functions and the challenges therein. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7: a020404, 2015. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan F, Niaz K, Maqbool F, Ismail Hassan F, Abdollahi M, Nagulapalli Venkata KC, Nabavi SM, Bishayee A. Molecular targets underlying the anticancer effects of quercetin: an update. Nutrients 8: 529, 2016. doi: 10.3390/nu8090529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klip A, Hawkins M. Desperately seeking sugar: glial cells as hypoglycemia sensors. J Clin Invest 115: 3403–3405, 2005. doi: 10.1172/JCI27208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koyama Y, Coker RH, Stone EE, Lacy DB, Jabbour K, Williams PE, Wasserman DH. Evidence that carotid bodies play an important role in glucoregulation in vivo. Diabetes 49: 1434–1442, 2000. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.9.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwon O, Eck P, Chen S, Corpe CP, Lee JH, Kruhlak M, Levine M. Inhibition of the intestinal glucose transporter GLUT2 by flavonoids. FASEB J 21: 366–377, 2007. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6620com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee GS, Subramanian N, Kim AI, Aksentijevich I, Goldbach-Mansky R, Sacks DB, Germain RN, Kastner DL, Chae JJ. The calcium-sensing receptor regulates the NLRP3 inflammasome through Ca2+ and cAMP. Nature 492: 123–127, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature11588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li AJ, Wang Q, Elsarelli MM, Brown RL, Ritter S. Hindbrain catecholamine neurons activate orexin neurons during systemic glucoprivation in male rats. Endocrinology 156: 2807–2820, 2015. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin LH, Moore SA, Jones SY, McGlashon J, Talman WT. Astrocytes in the rat nucleus tractus solitarii are critical for cardiovascular reflex control. J Neurosci 33: 18608–18617, 2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madden CJ, Stocker SD, Sved AF. Attenuation of homeostatic responses to hypotension and glucoprivation after destruction of catecholaminergic rostral ventrolateral medulla neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R751–R759, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00800.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martín ED, Fernández M, Perea G, Pascual O, Haydon PG, Araque A, Ceña V. Adenosine released by astrocytes contributes to hypoxia-induced modulation of synaptic transmission. Glia 55: 36–45, 2007. doi: 10.1002/glia.20431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marty N, Dallaporta M, Foretz M, Emery M, Tarussio D, Bady I, Binnert C, Beermann F, Thorens B. Regulation of glucagon secretion by glucose transporter type 2 (glut2) and astrocyte-dependent glucose sensors. J Clin Invest 115: 3545–3553, 2005. doi: 10.1172/JCI26309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marty N, Dallaporta M, Thorens B. Brain glucose sensing, counterregulation, and energy homeostasis. Physiology (Bethesda) 22: 241–251, 2007. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00010.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCudden CR, Hains MD, Kimple RJ, Siderovski DP, Willard FS. G-protein signaling: back to the future. Cell Mol Life Sci 62: 551–577, 2005. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4462-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McDougal DH, Hermann GE, Rogers RC. Astrocytes in the nucleus of the solitary tract are activated by low glucose or glucoprivation: evidence for glial involvement in glucose homeostasis. Front Neurosci 7: 249, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McDougal DH, Hermann GE, Rogers RC. Vagal afferent stimulation activates astrocytes in the nucleus of the solitary tract via AMPA receptors: evidence of an atypical neural-glial interaction in the brainstem. J Neurosci 31: 14037–14045, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2855-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McDougal DH, Viard E, Hermann GE, Rogers RC. Astrocytes in the hindbrain detect glucoprivation and regulate gastric motility. Auton Neurosci 175: 61–69, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mizuno Y, Oomura Y. Glucose responding neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius of the rat: in vitro study. Brain Res 307: 109–116, 1984. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Müller MS, Obel LF, Waagepetersen HS, Schousboe A, Bak LK. Complex actions of ionomycin in cultured cerebellar astrocytes affecting both calcium-induced calcium release and store-operated calcium entry. Neurochem Res 38: 1260–1265, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Newgard CB, McGarry JD. Metabolic coupling factors in pancreatic beta-cell signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem 64: 689–719, 1995. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Niijima A. The effect of D-glucose on the firing rate of glucose-sensitive vagal afferents in the liver in comparison with the effect of 2-deoxy-D-glucose. J Auton Nerv Syst 10: 255–260, 1984. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(84)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Kerr JN, Helmchen F. Sulforhodamine 101 as a specific marker of astroglia in the neocortex in vivo. Nat Methods 1: 31–37, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nmeth706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oomura Y, Yoshimatsu H. Neural network of glucose monitoring system. J Auton Nerv Syst 10: 359–372, 1984. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(84)90033-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pan W, Hsuchou H, Jayaram B, Khan RS, Huang EY, Wu X, Chen C, Kastin AJ. Leptin action on nonneuronal cells in the CNS: potential clinical applications. Ann NY Acad Sci 1264: 64–71, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06472.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pascual O, Casper KB, Kubera C, Zhang J, Revilla-Sanchez R, Sul JY, Takano H, Moss SJ, McCarthy K, Haydon PG. Astrocytic purinergic signaling coordinates synaptic networks. Science 310: 113–116, 2005. doi: 10.1126/science.1116916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pasti L, Volterra A, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G. Intracellular calcium oscillations in astrocytes: a highly plastic, bidirectional form of communication between neurons and astrocytes in situ. J Neurosci 17: 7817–7830, 1997. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07817.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perea G, Navarrete M, Araque A. Tripartite synapses: astrocytes process and control synaptic information. Trends Neurosci 32: 421–431, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rajani V, Zhang Y, Jalubula V, Rancic V, SheikhBahaei S, Zwicker JD, Pagliardini S, Dickson CT, Ballanyi K, Kasparov S, Gourine AV, Funk GD. Release of ATP by pre-Botzinger complex astrocytes contributes to the hypoxic ventilatory response via a Ca2+ -dependent P2Y1 receptor mechanism. J Physiol 596: 3245-3269, 2018. doi: 10.1113/JP274727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reeves AM, Shigetomi E, Khakh BS. Bulk loading of calcium indicator dyes to study astrocyte physiology: key limitations and improvements using morphological maps. J Neurosci 31: 9353–9358, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0127-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reyes BA, Estacio MA, I’Anson H, Tsukamura H, Maeda KI. Glucoprivation increases estrogen receptor alpha immunoreactivity in the brain catecholaminergic neurons in ovariectomized rats. Neurosci Lett 299: 109–112, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(01)01490-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ritter RC, Slusser PG, Stone S. Glucoreceptors controlling feeding and blood glucose: location in the hindbrain. Science 213: 451–452, 1981. doi: 10.1126/science.6264602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ritter S, Dinh TT, Li AJ. Hindbrain catecholamine neurons control multiple glucoregulatory responses. Physiol Behav 89: 490–500, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ritter S, Li AJ, Wang Q, Dinh TT. Minireview: The value of looking backward: the essential role of the hindbrain in counterregulatory responses to glucose deficit. Endocrinology 152: 4019–4032, 2011. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rogers RC, Hermann GE. Brainstem control of gastric function. In: Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract, edited by Johnson LR. (4th ed.). Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic, 2012, p. 861–891. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rogers RC, Hermann GE. Hindbrain astrocytes and glucose counter-regulation. Physiol Behav 204: 140–150, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rogers RC, Hermann GE. Tumor necrosis factor activation of vagal afferent terminal calcium is blocked by cannabinoids. J Neurosci 32: 5237–5241, 2012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6220-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rogers RC, McDougal DH, Ritter S, Qualls-Creekmore E, Hermann GE. Response of catecholaminergic neurons in the mouse hindbrain to glucoprivic stimuli is astrocyte dependent. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 315: R153–R164, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00368.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rogers RC, Nasse JS, Hermann GE. Live-cell imaging methods for the study of vagal afferents within the nucleus of the solitary tract. J Neurosci Methods 150: 47–58, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rogers RC, Ritter S, Hermann GE. Hindbrain cytoglucopenia-induced increases in systemic blood glucose levels by 2-deoxyglucose depend on intact astrocytes and adenosine release. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 310: R1102–R1108, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00493.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rorsman P, Ashcroft FM. Pancreatic β-cell electrical activity and insulin secretion: of mice and men. Physiol Rev 98: 117–214, 2018. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Savtchouk I, Volterra A. Gliotransmission: beyond black-and-white. J Neurosci 38: 14–25, 2018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0017-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schuit FC, Huypens P, Heimberg H, Pipeleers DG. Glucose sensing in pancreatic beta-cells: a model for the study of other glucose-regulated cells in gut, pancreas, and hypothalamus. Diabetes 50: 1–11, 2001. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith K. Neuroscience: settling the great glia debate. Nature 468: 160–162, 2010. doi: 10.1038/468160a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stolarczyk E, Guissard C, Michau A, Even PC, Grosfeld A, Serradas P, Lorsignol A, Pénicaud L, Brot-Laroche E, Leturque A, Le Gall M. Detection of extracellular glucose by GLUT2 contributes to hypothalamic control of food intake. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E1078–E1087, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00737.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stolarczyk E, Le Gall M, Even P, Houllier A, Serradas P, Brot-Laroche E, Leturque A. Loss of sugar detection by GLUT2 affects glucose homeostasis in mice. PLoS One 2: e1288, 2007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stunkard AJ, Wolff HG, Plescia A. Studies on the physiology of hunger. I. The effect of intravenous administration of glucose on gastric hunger contractions in man. J Clin Invest 35: 954–963, 1956. doi: 10.1172/JCI103355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tisi R, Baldassa S, Belotti F, Martegani E. Phospholipase C is required for glucose-induced calcium influx in budding yeast. FEBS Lett 520: 133–138, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02806-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Van Cauter E, Blackman JD, Roland D, Spire JP, Refetoff S, Polonsky KS. Modulation of glucose regulation and insulin secretion by circadian rhythmicity and sleep. J Clin Invest 88: 934–942, 1991. doi: 10.1172/JCI115396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vance KM, Rogers RC, Hermann GE. PAR1-activated astrocytes in the nucleus of the solitary tract stimulate adjacent neurons via NMDA receptors. J Neurosci 35: 776–785, 2015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3105-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Volterra A, Meldolesi J. Astrocytes, from brain glue to communication elements: the revolution continues. Nat Rev Neurosci 6: 626–640, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nrn1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Watts AG, Donovan CM. Sweet talk in the brain: glucosensing, neural networks, and hypoglycemic counterregulation. Front Neuroendocrinol 31: 32–43, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wehrwein EA, Basu R, Basu A, Curry TB, Rizza RA, Joyner MJ. Hyperoxia blunts counterregulation during hypoglycaemia in humans: possible role for the carotid bodies? J Physiol 588: 4593–4601, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.197491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wood TE, Dalili S, Simpson CD, Hurren R, Mao X, Saiz FS, Gronda M, Eberhard Y, Minden MD, Bilan PJ, Klip A, Batey RA, Schimmer AD. A novel inhibitor of glucose uptake sensitizes cells to FAS-induced cell death. Mol Cancer Ther 7: 3546–3555, 2008. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yettefti K, Orsini JC, el Ouazzani T, Himmi T, Boyer A, Perrin J. Sensitivity of nucleus tractus solitarius neurons to induced moderate hyperglycemia, with special reference to catecholaminergic regions. J Auton Nerv Syst 51: 191–197, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(94)00130-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Young JK, Baker JH, Montes MI. The brain response to 2-deoxy glucose is blocked by a glial drug. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 67: 233–239, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(00)00315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhao F, Li P, Chen SR, Louis CF, Fruen BR. Dantrolene inhibition of ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels. Molecular mechanism and isoform selectivity. J Biol Chem 276: 13810–13816, 2001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhou SY, Lu YX, Owyang C. Gastric relaxation induced by hyperglycemia is mediated by vagal afferent pathways in the rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G1158–G1164, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00067.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]