Abstract

Introduction

Accurately diagnosing and treating infants with mild forms of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is important, as the majority of neonates with signs and symptoms of HIE after birth do not meet clinical criteria for moderate or severe disease. Emerging evidence, however, suggests that infants with mild HIE (mHIE) have an increased risk for neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI).

Methods

This retrospective descriptive study examined all inborn infants ≥35 week's gestational age at a single, level III neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in California between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2015. International Classification of Diseases codes were used as a proxy to identify neonates with mHIE but who did not receive therapeutic hypothermia (TH). Short- and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes were documented, including abnormal (1) brain magnetic resonance imaging within 10 days of birth suggestive of HIE, (2) electroencephalogram with electrographic seizures, (3) neurologic discharge examination, or (4) NDI following NICU discharge.

Results

Over the 4-year study period, 25 infants met inclusion criteria. Eight of 25 (32%) infants demonstrated neurologic impairment, defined by an abnormality in at least one of the four categories. The remaining 17 infants were without documented evidence for adverse outcomes.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that children with mHIE are at significant risk for neurologic injury and may benefit from more aggressive interventions. Further prospective studies should be completed to determine the efficacy of TH in this specific patient population.

Keywords: Brain injury, Newborn, Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

What Is It about?

Characterizing outcomes of infants with mild hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (mHIE) has proven elusive to date. In this study, we retrospectively examined International Classification of Diseases codes to identify infants with mHIE but not cooled. A small but significant percentage (32%) of neonates had deleterious short-term outcomes. Our results suggest that untreated infants with mHIE are susceptible to injury. Further studies are needed to help identify if therapeutic hypothermia is efficacious for infants with mHIE.

Introduction

For infants who sustain moderate-to-severe hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) due to perinatal events, therapeutic hypothermia (TH) is the only medical intervention with proven neurodevelopmental benefits when initiated as early as possible within the first 6 h of life [1, 2, 3]. HIE exists on a spectrum, accounting for birth history, clinical exam, and laboratory markers at ≤6 h of life. It is not always clear, therefore, how to best manage patients with milder forms of HIE, although some medical centers are experiencing a clinical drift and cooling these infants [4]. Accurately identifying infants with mild HIE (mHIE) is important, as most infants (>50%) diagnosed with hypoxic brain injury do not meet standard clinical criteria for moderate or severe encephalopathy [5]. Emerging evidence suggests these infants have a heightened risk for adverse short-term outcomes, including an abnormal discharge examination, discontinuous amplitude integrated electroencephalogram (aEEG), brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing hypoxic injury, and long-term neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI), if left untreated [6].

A paucity of peer-reviewed literature has examined medical management and outcomes of infants with mHIE. DuPont et al.[7] used perinatal acidosis in infants ≥36 weeks' gestational age (GA), who did not meet their institution's criteria for TH, to identify mHIE patients. These investigators demonstrated that nearly 1 in 5 infants with mHIE had abnormal short-term outcomes that could be attributed to their acidosis [7]. It is also recognized that brain injury severity can evolve and worsen over time, necessitating serial neurologic exams by experienced providers and consideration for standard aEEG and MRI testing. Similar to other cooling institutions, we have struggled with whether to initiate TH for infants presenting with mHIE. Due to the nature of their encephalopathy, these patients may improve rapidly but be destined to remain on TH protocols for the full 72 h, inhibiting normal neonatal behaviors, parental bonding, and breastfeeding. Moreover, TH may not be the best therapy for infants with mHIE, as a range of other treatment modalities are being evaluated, including erythropoietin, melatonin, and possibly stem cell therapy. In our geographic region, the trend to cool progressively milder cases of HIE has been growing. Given these factors, it is essential to better characterize infants with mHIE who are at risk for adverse NDIs and determine if TH or other treatments may be beneficial.

The goal of this study was to characterize outcomes of infants with mHIE but who were not cooled, using International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes as a proxy for infants not deemed to have moderate or severe HIE within the first 6 h of life. By including all at-risk infants, we have identified some neonates who had mHIE but were not subsequently treated. Given the difficulty of diagnosing infants with mHIE and its unclear natural progression, we believe results from this study will contribute to the growing body of data regarding current clinical management and outcomes for infants with mHIE.

Methods

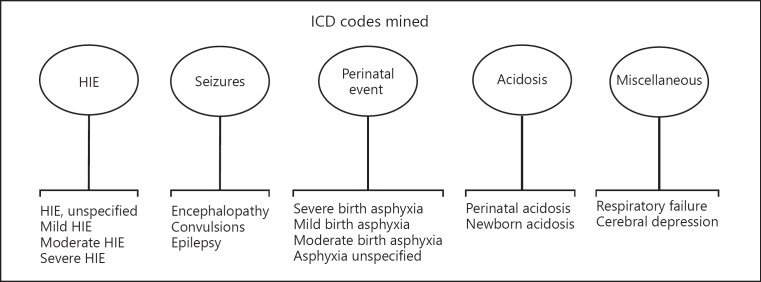

This retrospective descriptive study examined exclusively inborn infants delivered at a level III neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in Southern California. ICD codes were used to identify all infants born between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2015. Search terms included five general umbrella categories: (1) HIE, (2) seizures, (3) perinatal events, (4) acidosis, and (5) miscellaneous, with specific ICD phrases outlined in Figure 1. The electronic medical records (EMR) of infants found to have any of the identified ICD codes were examined and included. Study participants identified by this method had documented neurologic exams performed by a skilled provider within 6 h of birth using modified Sarnat criteria, with most but not all infants exhibiting exam findings consistent with mild encephalopathy within this period. After an infant was found to have an ICD code that matched one of the search terms (Fig. 1), charts were reviewed to determine if they had individual markers that met various aspects of screening criteria listed by the California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative (CPQCC) [8]. These individual markers included any infant ≥35 weeks and ≤6 h of age with at least one of the following risks for encephalopathy: (1) history of acute perinatal event, (2) a 10-min Apgar score ≤6, (3) continued need for positive pressure ventilation for 10 min or history of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or (4) a venous or arterial blood gas sample with pH ≤7.00 or base deficit ≤10 mmol/L. Any infant that had both an ICD search term match with at least one individual CPQCC marker for screening and that did not receive TH was included in the final analysis. For this study, therefore, we defined mHIE as any infant with: (1) documented metabolic acidosis immediately following birth, that (2) fulfilled any screening criteria as outlined by the CPQCC, and (3) exhibited abnormal neurologic findings per modified Sarnat criteria within their hospital course.

Fig. 1.

ICD-10 codes mined between 2012 and 2015.

Exclusion criteria included GA <35 weeks, presence of known chromosomal abnormality, major congenital anomaly, birth weight <1,800 g, infants that lacked a birth history documented in the EMR and infants who received TH. The criteria used to initiate TH were GA ≥36 weeks, ≤6 h of age, and at least one or more of the following: (1) a pH of ≤7.1 or a base deficit of ≥12 mmol/L in a sample of umbilical cord blood or a blood gas obtained during the first hour of life, (2) a 10-min Apgar score of <5, (3) assisted ventilation initiated at birth and continued for at least 10 min, or (4) any neurologic examination indicative of moderate or severe encephalopathy within the first 6 h after birth [9]. Records were reviewed at both the inborn NICU site and at the regional children's medical center where many of these infants later received well-child care, emergency visits, or were acutely hospitalized during the first 2.5 years of life.

Abnormal short-term outcomes were defined as evidence of seizure activity per EEG, as determined by the consulting board-certified pediatric neurologist, MRI findings suggestive of HIE, or abnormal neurologic findings upon discharge examination. Brain MRI with routine clinical sequences was obtained in infants with clinical suspicion for mHIE on a 1.5-T MR system without sedation. Images were reviewed by a board-certified neuroradiologist with 7 years of experience, who remained blinded to clinical outcomes and original reports. Studies were scored using the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development-Neonatal Research Network (NICHD-NRN) scoring system [10, 11] and the Barkovich Basal Ganglia/Watershed (BG/W) score [12]. Sequences included T1, T2, proton density, FLAIR, T2/GRE, and diffusion-weighted sequences. Abnormal neurologic exam at discharge was defined as the presence of aberrations of muscle tone, reflexes, or movements. Discharge exams were performed by various clinicians, including residents, fellows, and nurse practitioners, but were corroborated by board-certified neonatal-perinatal medicine specialists. Completion of EEG and MRI studies was at the discretion of the attending neonatologist, and they were, therefore, not available for all study participants. Abnormal long-term outcome and NDI were defined as an ICD diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional behavioral disorder, or developmental delay as documented in the EMR. No standard neurodevelopmental assessment was performed at follow-up as attendance at high-risk infant follow-up clinic was limited. For the purposes of this study, an infant was considered abnormal and with mHIE if they had an MRI suggestive of HIE, EEG with electrographic seizures, demonstrated deficits on the discharge neurologic exam or evidence of NDI at follow-up. Only some of the infants in the abnormal category had mild encephalopathy on exam within 6 h from birth; others did not. This study was approved with a waiver of informed consent by the medical center's Institutional Review Board. Data were described as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range). Analysis was performed using Student t tests (2-sided) and T and Fischer exact tests. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using R programming language (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

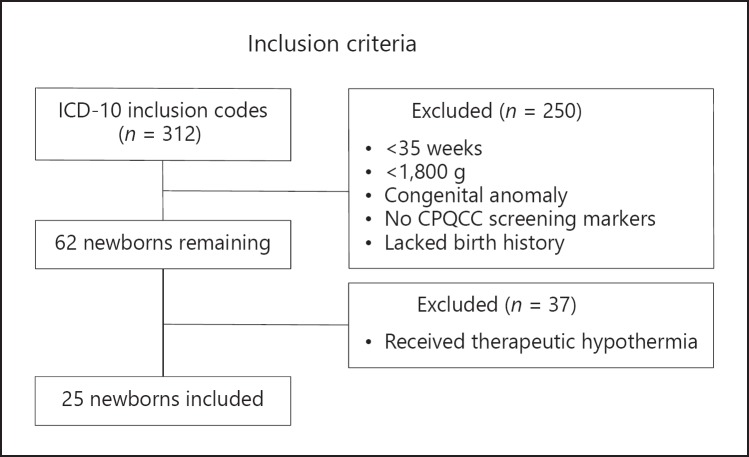

Over a 4-year period, 312 newborns with an ICD diagnosis as listed in Figure 1 were reviewed. Of 62 identified inborn infants who fulfilled our inclusion criteria, 37 completed TH and 25 were selected for final analysis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Inclusion criteria for all infants with ICD-10 codes mined.

There were no statistically significant differences between groups for baseline characteristics, particularly maternal, perinatal, and delivery room categories (Table 1, 2). In our defined study group, 6 of 17 infants with normal outcomes experienced an identified sentinel event at birth compared to no sentinel events documented in infants with abnormal findings on testing or long-term follow-up. Moreover, no statistically significant differences were found between the number of infants born via vacuum- or forceps-assisted birth in the normal versus abnormal cohorts. There was only one infant in the abnormal category that was born via emergency cesarean section (Table 1). Most infants required positive pressure ventilation in the delivery room, although when comparing both groups, this did not reach statistical significance (65% of normal vs. 88% of abnormal cohort, p = 0.36). Arterial pH was also similar between normal and abnormal outcome cohorts (7.06 vs. 7.14, p = 0.11).

Table 1.

Maternal and perinatal characteristics

| Normal (n = 17) | Abnormal (n = 8) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Age, years | 31.06±6.2 | 31.5±6.1 | 0.88 |

| Ethnicity | 0.81 | ||

| White | 6 (35) | 4 (50) | |

| Asian | 4 (24) | 1 (13) | |

| African-American | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | |

| Hispanic | 5 (29) | 3 (38) | |

| Gestational hypertension | 4 (24) | 2 (25) | 1 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (6) | 2 (25) | 1 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 3 (18) | 2 (25) | 1 |

| Pre-eclampsia | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Twin gestation | 0 (0) | 1 (13) | 0.32 |

| Perinatal characteristics | |||

| Fever | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| GBS+ | 4 (24) | 1 (13) | 0.63 |

| Rupture >18 h | 6 (35) | 3 (38) | 1 |

| PROM (>18 h) | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| PPROM | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 5 (29) | 2 (25) | 1 |

| Maternal antibiotics | 9 (53) | 4 (50) | 1 |

| Abnormal fetal heart rate pattern | 6 (35) | 3 (38) | 1 |

| Sentinel eventa | 6 (35) | 0 (0) | 0.13 |

| Meconium-stained amniotic fluid | 9 (53) | 4 (50) | 1 |

| Shoulder dystocia | 4 (24) | 1 (13) | 1 |

| NSVD | 11 (65) | 4 (50) | 0.67 |

| NSVD with instrumentation (vacuum, forceps) | 2 (12) | 3 (38) | 0.28 |

| C/S | 6 (35) | 4 (50) | 0.67 |

| Emergency C/S | 0 (0) | 1 (13) | 0.32 |

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or n (%). GBS, group B Streptococcus; PPROM, preterm premature rupture of membranes; NSVD, normal spontaneous vaginal delivery; C/S, cesarean section.

Defined as evidence of bloody amniotic fluid, nuchal cord, or cord prolapse.

Table 2.

Neonatal delivery characteristics

| Infant characteristics | Normal (n = 17) | Abnormal (n = 8) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age, weeks | 39.08±1.9 | 39.12±2.2 | 0.96 |

| Birth weight, g | 3,443±745 | 3,164±1,148 | 0.49 |

| Inborn | 17 (100) | 8 (100) | N/A |

| Resuscitation | |||

| Positive pressure | |||

| ventilation | 11 (65) | 7 (88) | 0.36 |

| Chest compressions | 1 (6) | 1 (13) | 1 |

| Apgar score 1 min | 2 [2, 5] | 2 [2, 2] | 0.6 |

| Apgar score 5 min | 6 [5, 7] | 5.5 [5,6] | 0.93 |

| Cord blood gas | |||

| Arterial pH | 7.06±0.8 | 7.14±0.12 | 0.11 |

| Arterial base deficit | 7.91±2.78 | 7.63±3.31 | 0.85 |

| Venous pH | 7.17±0.09 | 7.22±0.14 | 0.32 |

| Venous base deficit | 8.66±3.44 | 6.87±3.16 | 0.29 |

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, n (%), or median [interquartile range].

Seventeen of 25 infants had no evidence of any short- or long-term impairment. Eight of 25 (32%) infants had evidence of impairment as defined by an abnormality in at least one of four categories (Table 3). At least one of the 8 infants met abnormal criteria from each of the individual categories. Seven of 8 (78%) infants had documented brain MRI findings consistent with possible HIE as defined by the NICHD-NRN scoring system [11]. Five had documented 1a injury (minimal cerebral lesions), one had 1b injury (more extensive cerebral lesions), and one had 2a injury (basal ganglia, internal capsule or watershed lesions and no other cerebral lesions). Furthermore, of the 8 infants with adverse outcomes, 3 had abnormal EEG tracings showing seizures and 4 had an abnormal neurologic discharge exam. One infant who had an abnormal MRI but a normal discharge exam was later diagnosed with autism. Another infant who was found to have an abnormal EEG, MRI, and discharge exam was later diagnosed with developmental delay.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the 8 infants with at least 1 abnormal finding

| Infant | MRI DOL | MRI NICHD-NRN score | EEG with seizures | Abnormal discharge exam | Adverse ND outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 1a | − | no | autism | |

| 2 | 6 | 1a | No | no | no | |

| 3 | 7 | 2a | − | hypotonia and head lag | no | |

| 4 | − | − | − | axial hypotonia | no | |

| 5 | 4 | 1a | yes | no | no | |

| 6 | 3 | 1a | yes | axial hypotonia | no | |

| 7 | 4 | 1b | yes | truncal hypotonia | Health and developmental delay | |

| 8 | 10 | 1a | − | no | no |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; DOL, day of life; NICHD-NRN, National Institute of Child Human Development-Neonatal Research Network; EEG, electroencephalogram; ND, neurodevelopmental.

Discussion

Perinatal asphyxia remains one of the most devastating causes of neurologic injury in neonatal patients due primarily to the posthypoxic pathophysiologic adaptations that occur approximately 6–48 h after the initial injury. It is the posthypoxic pathophysiologic adaptations to injury that are generally targeted by cooling therapies and treatments, as this phase is believed to be critical in the development of poor long-term outcomes in infants with initial diagnoses of mHIE [13, 14].

Because early neonatal hypothermia trials were designed to select infants with the highest probability of poor outcomes, patients with mHIE were typically excluded [1]. Presently, no recommended or proven treatment modality exists for infants who sustain mHIE [15]. DuPont et al.[7] demonstrated that 20% of newborns with perinatal acidemia and a neurologic exam consistent with mHIE had abnormal short-term outcomes attributable to their encephalopathy, such as seizures, death from progressive asphyxial insult, abnormal MRI findings consistent with HIE, abnormal neurologic examination at discharge, gastrostomy tube feeding, or nippling difficulties in the neonatal period. Our study affirms DuPont group's findings, with 32% of our study population exhibiting abnormal findings on MRI, EEG, discharge examination, and/or demonstrating NDI at up to 2.5-year follow-up. Seven infants with brain MRIs exhibited injury consistent with HIE, with one found to have an MRI NICHD-NRN score of 2a suggesting lesions involving watershed infarcts in the frontal cortex bilaterally [16].

Our study is unique in that all infants reviewed were inborn and, therefore, not subjected to inherent difficulties that occur when studying outborn patients, such as interobserver differences in neurologic examination findings or inability to accurately identify or define neurologic changes that may occur over time due to multiple provider assessments. Since neonatal encephalopathy is a dynamic process, anoxic injury may worsen over hours to days with progression from mild to moderate or even severe encephalopathy, and the ability of the modified Sarnat exam to adequately predict which infants with mHIE will subsequently develop adverse long-term outcomes remains troubling [7, 17]. The modified Sarnat exam evaluates autonomic function, complex reflexes, level of consciousness, muscle tone, and tendon reflexes to classify neonatal HIE into three categories: stage I (mild), stage II (moderate), and stage III (severe) [17]. In DuPont group's study, the predictive ability of each component of the modified Sarnat examination, and even combinations of two categories, was a poor predictor of abnormal short-term outcomes consistent with more severe encephalopathy in infants classified as mHIE [7].

Very recent studies have addressed long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes for infants with mHIE. The PRIME study completed by Chalak et al. [6] in 2018 suggests untreated neonates with mHIE have worse developmental outcomes compared to their healthy term counterparts, with 16% of untreated infants with mHIE exhibiting disabilities at 18–22 months. Conversely, developmental outcomes were found to be similar between healthy term infants and neonates with mHIE who completed TH in a 2019 publication by Rao et al. [18]. Infants with mHIE who are treated with standard, routine TH protocols exhibit signs of distress and/or shivering for the 72-h treatment course, which may be traumatic for medical personnel and/or family members. While TH is considered a generally safe and effective therapy for infants with moderate and severe forms of HIE, this therapy lacks true equipoise for neonates with mHIE [15]. Reported side effects of TH include sclerema neonatorum, hypovolemia, glucose instability, pulmonary hypertension, and multisystem organ dysfunction [19, 20, 21]. Further studies are therefore required to determine if infants with mHIE benefit from standard TH protocols, or if modifications in cooling time and/or temperature could yield similar or more promising results with less physical discomfort.

There are a few limitations to this study. Our work is retrospective and thus prospective determinations of mHIE for study inclusion were not made. Instead, we have attempted to use a combination of ICD codes and later outcomes data as a proxy for infants with mHIE. Additionally, infants with abnormal outcomes were born without a documented sentinel perinatal event, which may indicate an in utero anoxic event. The retrospective nature of this study makes this determination difficult; it is also possible that injury could have occurred outside the standard 6-h intervention window. In addition, discharge neurologic exams were performed by multiple providers including trainees, although each exam was confirmed by the attending neonatologist. There was also variable follow-up data available, often dependent on whether a patient attended a neurodevelopmental clinic appointment or sought inpatient or outpatient care at the regional children's medical center. Proper follow-up and standard neurodevelopmental assessment were lacking. Lastly, not all infants had MRI or EEG performed. Additionally, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) was not included in our review as it is not currently part of the NICHD-NRN scoring system used to determine injury grade. Recent conclusions from a large consortium of pediatric neurologists demonstrated that MRS of the left thalamus within the first 4–14 days after injury was predictive of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes [22]. Because our center does not currently measure this specific value, our neuroradiologist, Dr. Julie Bykowski, determined our routinely measured MRS values were not sufficient for predicting adverse effects in our study subjects.

Conclusion

Neonates with clinical indicators consistent with mHIE are at risk for adverse short-term and, possibly, long-term outcomes. These infants should be further studied to determine clinical factors, biologic markers, or diagnostic indicators that differentiate infants with normal outcomes from those most at risk. Neonates with “mild” HIE need to be included in investigations that evaluate the efficacy of emerging therapies for infants with anoxic encephalopathy. Observed trends of cooling infants with mild encephalopathy, outside a clinical trial or national registry, remain worrisome.

Statement of Ethics

The study was approved by the University of California San Diego Institutional Review Board and its Human Research Protections Program.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding Sources

None.

Author Contributions

Jonathan Reiss was responsible for study design, data collection and manuscript development. Mridu Sinha was responsible for study design, data collection, statistical analysis, and manuscript development. Jeffrey Gold was responsible for study design and manuscript development. Julie Bykowski assisted with MRI analysis and manuscript development. Shelley M. Lawrence was responsible for study design, data analysis, and manuscript development.

References

- 1.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, Tyson JE, McDonald SA, Donovan EF, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005 Oct;353((15)):1574–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps050929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simbruner G, Mittal RA, Rohlmann F, Muche R, neo.nEURO.network Trial Participants Systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: outcomes of neo.nEURO.network RCT. Pediatrics. 2010 Oct;126((4)):e771–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gluckman PD, Wyatt JS, Azzopardi D, Ballard R, Edwards AD, Ferriero DM, et al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2005 Feb;365((9460)):663–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17946-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lodygensky GA, Battin MR, Gunn AJ. Mild Neonatal Encephalopathy-How, When, and How Much to Treat? JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Jan;172((1)):3–4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray DM, O'Connor CM, Ryan CA, Korotchikova I, Boylan GB. Early EEG Grade and Outcome at 5 Years After Mild Neonatal Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2016 Oct;138((4)):e20160659. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalak LF, Nguyen KA, Prempunpong C, Heyne R, Thayyil S, Shankaran S, et al. Prospective research in infants with mild encephalopathy identified in the first six hours of life: neurodevelopmental outcomes at 18-22 months. Pediatr Res. 2018 Dec;84((6)):861–8. doi: 10.1038/s41390-018-0174-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DuPont TL, Chalak LF, Morriss MC, Burchfield PJ, Christie L, Sánchez PJ. Short-term outcomes of newborns with perinatal acidemia who are not eligible for systemic hypothermia therapy. J Pediatr. 2013 Jan;162((1)):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.California Perinatal Quality Care Collaborative Early screening and identification of candidates for neonatal therapeutic hypothermia toolkit. 2015. [Available from: https://www.cpqcc.org/sites/default/files/pdf/toolkit/NeonatalTherapeuticHypothermiaToolkit_02.2015.pdf.

- 9.Papile LA, Baley JE, Benitz W, Cummings J, Carlo WA, Eichenwald E, et al. Committee on Fetus and Newborn Hypothermia and neonatal encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2014 Jun;133((6)):1146–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okereafor A, Allsop J, Counsell SJ, Fitzpatrick J, Azzopardi D, Rutherford MA, et al. Patterns of brain injury in neonates exposed to perinatal sentinel events. Pediatrics. 2008 May;121((5)):906–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutherford M, Ramenghi LA, Edwards AD, Brocklehurst P, Halliday H, Levene M, et al. Assessment of brain tissue injury after moderate hypothermia in neonates with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy: a nested substudy of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010 Jan;9((1)):39–45. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70295-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barkovich AJ, Hajnal BL, Vigneron D, Sola A, Partridge JC, Allen F, et al. Prediction of neuromotor outcome in perinatal asphyxia: evaluation of MR scoring systems. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998 Jan;19((1)):143–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Disdier C, Chen X, Kim JE, Threlkeld SW, Stonestreet BS. Anti-Cytokine Therapy to Attenuate Ischemic-Reperfusion Associated Brain Injury in the Perinatal Period. Brain Sci. 2018 Jun;8((6)):E101. doi: 10.3390/brainsci8060101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagberg H, Mallard C, Ferriero DM, Vannucci SJ, Levison SW, Vexler ZS, et al. The role of inflammation in perinatal brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015 Apr;11((4)):192–208. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nair J, Kumar VH. Current and Emerging Therapies in the Management of Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy in Neonates. Children (Basel) 2018 Jul;5((7)):E99. doi: 10.3390/children5070099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrasco M, Perin J, Jennings JM, Parkinson C, Gilmore MM, Chavez-Valdez R, et al. Cerebral Autoregulation and Conventional and Diffusion Tensor Imaging Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Neonatal Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy. Pediatr Neurol. 2018 May;82:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarnat HB, Sarnat MS. Neonatal encephalopathy following fetal distress. A clinical and electroencephalographic study. Arch Neurol. 1976 Oct;33((10)):696–705. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1976.00500100030012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao R, Trivedi S, Distler A, Liao S, Vesoulis Z, Smyser C, et al. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Neonates with Mild Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy Treated with Therapeutic Hypothermia. Am J Perinatol. 2019 Jan; doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaRosa DA, Ellery SJ, Walker DW, Dickinson H. Understanding the Full Spectrum of Organ Injury Following Intrapartum Asphyxia. Front Pediatr. 2017 Feb;5:16. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarkar S, Barks JD, Bhagat I, Donn SM. Effects of therapeutic hypothermia on multiorgan dysfunction in asphyxiated newborns: whole-body cooling versus selective head cooling. J Perinatol. 2009 Aug;29((8)):558–63. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahni R, Sanocka UM. Hypothermia for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Clin Perinatol. 2008 Dec;35((4)):717–34. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lally PJ, Montaldo P, Oliveira V, Soe A, Swamy R, Bassett P, et al. MARBLE consortium. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy assessment of brain injury after moderate hypothermia in neonatal encephalopathy a prospective multicentre cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2019 Jan;18((1)):35–45. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30325-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]