Abstract

Background

The neurotransmitter adenosine has been proposed to be involved in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy, which may be due to the vasoactive properties of the compound. Previous studies have shown that adenosine can affect the tone of retinal arterioles in vitro to induce dilatation mediated by A<sub>2A</sub> and A<sub>2B</sub>receptors and constriction mediated by A<sub>1</sub> and A<sub>3</sub> receptors.

Purpose

To investigate effects of intravenous administration of the adenosine A<sub>2A</sub> receptor agonist regadenoson on the diameter of retinal vessels in vivo.

Method

The diameter responses of larger retinal arterioles and venules were evaluated using the dynamic vessel analyser in 20 normal persons (age 22–31 years) after intravenous administration of the adenosine A<sub>2A</sub> receptor agonist regadenoson during exposure to systemic normoxia and hypoxia.

Results

The diameter of retinal arterioles and venules increased significantly during stimulation with flickering light (p < 0.0001). Regadenoson reduced the flicker-induced dilatation of venules during normoxia (p = 0.0006), but otherwise had no effect on vessel diameters (p > 0.08 for all comparisons).

Conclusions

Intravenous administration of the adenosine A<sub>2A</sub> receptor agonist regadenoson had no significant effect on the diameter of retinal arterioles. Future studies should investigate differential effects of intra- and extravascular administration of adenosine receptor agonists on retinal vessels.

Keywords: Adenosine, A2A receptor, Dynamic vessel analyser, Retinal blood flow, Diameter changes

What Is It about?

The neurotransmitter adenosine can dilate retinal arterioles in vitro mediated by A2A receptors, but it is unknown whether this effect can be elicited in vivo. The present study showed that intravenous administration of the adenosine A2A receptor agonist regadenoson in normal persons reduced dilatation of retinal vessels induced by flickering light (p = 0.0006), but otherwise had no significant effect on the diameter of retinal arterioles. The finding may be related to the route of administration of regadenoson, and future studies should investigate differential effects of intra- and extravascular administration of adenosine receptor agonists on retinal vessels.

Introduction

The purinergic compound adenosine plays important roles in human metabolism by its integration in the nucleic acids of the genome [1], as a constituent of the energy transporter adenosine triphosphate [2], and as an element in the inflammatory response leading to vasodilatation [3]. The metabolism of adenosine is changed in diabetes, and the compound has been proposed to be involved in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy [4], either as a cause of vascular pathology or as a consequence of disturbed retinal vascular function in the disease [5].

Previous in vitro studies have shown that adenosine has dual effects on retinal vascular tone with relaxation mediated by adenosine A2receptors [6] and contraction mediated by adenosine A1 receptors in the perivascular retina and adenosine A3 receptors in the retinal vascular walls [5]. Therefore, it is possible that findings of both hyper- and hypoperfusion in retinal vascular disease could be due to dual effects of adenosine acting on different receptor types. A study in normal humans has shown that intravenous infusion of adenosine increases blood flow in the choroid and the optic nerve head in vivo [7], suggesting a predominant effect mediated by A2 receptors. However, interventional studies using adenosine are limited by the short half-life of the compound within seconds and adverse effects such as dizziness and chest discomfort [8]. The approval of the specific adenosine A2A receptor agonist regadenoson as a pharmacological stress agent with a half-life within minutes has enabled interventions on this specific adenosine receptor type [9]. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to investigate the effects of intravenous infusion of regadenoson on the diameter of larger retinal vessels.

Consequently, diameter changes of retinal vessels in normal persons were studied using the dynamic vessel analyser (DVA) after administration of regadenoson before and during stimulation with flickering light and before and during systemic hypoxia.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was an open prospective interventional study on 20 normal persons.

Test Persons

Twenty-two normal persons (11 males and 11 females) aged 24.7 ± 1.97, 22–31 years (mean ± SD, range), were enrolled from February 2017 to July 2017 after public announcement.

Exclusion criteria were: cardiovascular disease including arterial hypertension defined as systolic blood pressure ≥135 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mm Hg (Danish Cardiologic Society 2017), known pulmonary disease, epilepsy, ocular disease, pregnancy or lactation, daily medication except for contraceptives, and allergy to constituents in the drug used in the experiment. Participation required a normal electrocardiogram (Kohden Cardiofax M; Nihon Kohden Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and blood pressure (Omron 705IT; Omron Healthcare, Kyoto, Japan).

Among the 22 studied persons, 1 was excluded due to discomfort unrelated to the study procedure or medication, and one due to lack of achievement of hypoxia on the last examination day because of challenges with positioning of the mouthpiece.

Each test person was examined on 2 days separated by at least 24 h, mean 6.1 days, range 1–43 days. The test persons were instructed to avoid consumption of caffeine 24 h before the examinations.

First Examination Day

Clinical Examination

A routine ophthalmological evaluation was performed with measurement of best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) using Early Treatment for Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) charts, measurement of the intraocular pressure (IOP) (Nidek Tonoref II, Japan), and inspection of the eye in a slit lamp. The pupil of the left eye was dilated using phenylephrine (Metaoxedrin 10%, SAD; Amgros I/S, Copenhagen, Denmark), and tropicamide (Mydriacyl 1%; Alcon Nordic A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) scanning (Cirrus HD OCT; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany) was performed using the Macular Cube protocol consisting of 512 vertical and 128 horizontal scans within a 6 × 6 mm area centred on the fovea of the left eye. The central retinal thickness was noted as the average thickness within the central circular area with a diameter of 1 mm. Finally, fundus photography was performed (TRC-50DX; Topcon, Tokyo, Japan) with exposures centred respectively at the optic disk and the fovea of the left eye. The baseline characteristics of the included test persons are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the studied persons (mean ± SD)

| Age, years | 24.6±2.01 |

| MAP, mm Hg | 86.0±9.70 |

| SatO2, % | 99.7±0.70 |

| BCVA (ETDRS letters) | 93.2±7.14/94.7±3.29a |

| IOP, mm Hg | 14.8±3.70/15.2±3.78a |

| CRT, µm | −/263.2±19.71a |

MAP, mean arterial blood pressure; BCVA, best corrected visual acuity; ETDRS, early treatment for diabetic retinopathy study; IOP, intraocular pressure; CRT, central retinal thickness.

Right eye/left (study) eye.

Dynamic Vessel Analyser

The diameter of retinal vessels was measured using the DVA (Imedos Systems UG, Jena, Germany). The apparatus consists of a fundus camera with a video unit connected to a computer allowing the recording of video sequences of the retina during both constant illumination and during stimulation of the retina with flickering light, here set to a frequency of 12.5 Hz. The inbuilt software identifies the transition of contrast between the vessel and the retinal background to calculate the diameter of the vessel 25 times per second for every 10 μm along the segment throughout the examination and displays the diameters in arbitrary units approximately corresponding to micrometres at the retinal plane. The software automatically realigns the image to compensate for saccadic eye movements and interrupts the measurements when the vessel segments cannot be identified, i.e. during blinking.

Examination Procedure

The equipment for electrocardiography, pulse oximetry, and blood pressure measurement was Philips IntelliVue X2 (Philips Medizin Systeme, Böeblingen, Germany). The ECT electrodes were placed on the chest of the test person, and an intravenous cannula (BD VenflonTM Pro Safety, 22-gauge 0.9 × 25 mm; Becton Dickinson Infusion Therapy, Helsingborg, Sweden) was positioned in an antecubital vein of the right arm for drug administration. Every 90 s during the experiment, the blood pressure was measured using an oscillometric technique with a cuff placed on the upper left arm, and systemic oxygen saturation was measured using a pulse oximeter placed on the left index finger. Due to challenges with entering the superficial veins, drug administration was performed in the left arm in 2 test persons with measurement of blood pressure and oxygen saturation on the right arm.

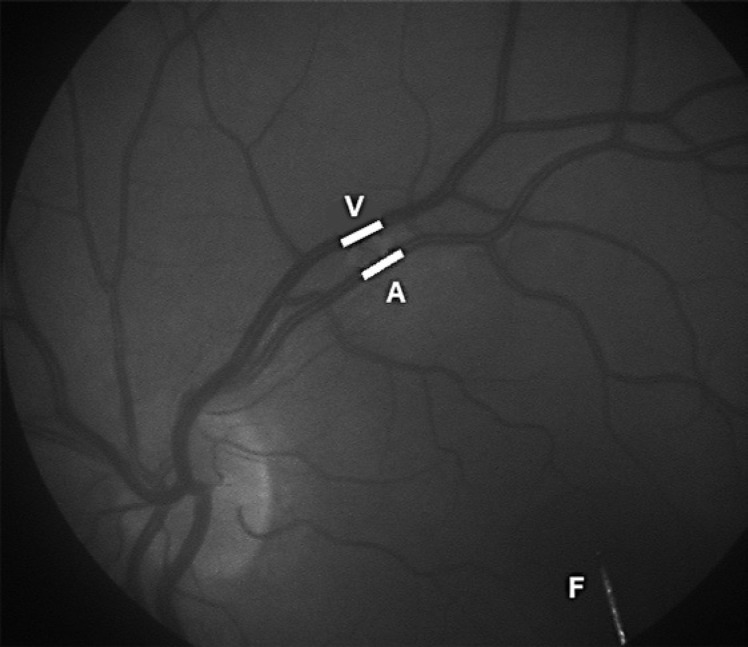

The test person was positioned in front of the DVA camera and was instructed to fixate the end of a bar inside the viewing system of the camera with the left eye. The retina was displayed on the computer monitor, and the most linear segment without branches on the upper or the lower temporal arteriole and its adjoining venule that was clearly separated from other vessels and located between one half and three disk diameters from the optic disk were selected (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Single image from a DVA recording with the vascular segments arteriole (A) and venule (V) chosen for diameter measurements marked with white lines. The tip of the fixation bar (F) is seen to the right.

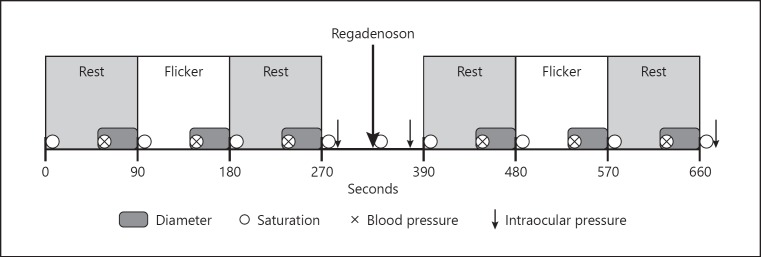

A DVA recording lasted 660 s (Fig. 2). The initial step lasted 270 s consisting of three uninterrupted phases: 90 s of rest, followed by 90 s of flicker light stimulation and another 90 s of rest. Subsequently, the diameter measurements were interrupted for 120 s to allow measurement of the IOP (Icare TA01i or PRO; Vantaa, Finland) and administration of 5 mL of the A2A adenosine receptor agonist regadenoson (Rapiscan; Dupharma A/S, Kastrup, Denmark) in a concentration of 80 µg/mL followed by 10 mL of sodium chloride 9 mg/mL in an antecubital vein. Regadenoson was administered after 320.3 ± 20.1 s (mean ± SD), range 300–400 s, followed by another measurement of the IOP. Subsequently, the diameter measurements were resumed with repetition of the initial step of 270 s, followed by a final measurement of the IOP. The test persons were monitored by a specialist in cardiology or an assistant cardiologic nurse during administration of regadenoson and the following 7 min.

Fig. 2.

The experimental protocol.

The diameter measurements from the proximal 200 µm of the vessel segments from the last 45 s of each phase were sampled. Each DVA examination was saved to allow a later re-analysis.

Second Examination Day

The test person started breathing a hypoxic gas mixture consisting of 12.5% oxygen and 87.5% nitrogen through a silicon mouthpiece connected to a two-way, non-rebreathable valve (Hans Rudolph Inc, Shawnee, KS, USA) with a nose peg that avoided mixing with ambient air. After 10 min, the examination procedure from the first examination day was repeated during continued breathing of the hypoxic gas mixture. The same vascular segments were chosen for the diameter measurements on both examination days in each test person.

Power Calculation

The test-retest variation during diameter measurements with the DVA has previously been estimated to be 0.06% (95% CI: −0.92 to 1.04) with a Pearson correlation of 0.99 (95% CI: 0.98 to 0.99). This indicates that with a two-sided t test and a power of 70%, 17 persons are required to detect a 2% change in vessel diameter. With the included 20 persons, the study achieved a power of 82%.

Data Analysis

The diameter of the retinal vessels was calculated as the mean of the real-time recordings measured during the last 45 s of each 90-s phase. Each DVA examination was replayed from the stored recording with repetition of the manual selection of the vessel segments and the sampling and calculation of diameters. The duplicate determinations of the diameter from phase 1 deviated more than 1% in 37 of 80 (46.3%) diameter measurements. In these cases, a third analysis was performed. For each diameter measurement, data from the two measurements with the smallest deviation from each other were pooled and used for further analysis.

The mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) was calculated as MAP = (1/3 × BPSys) + (2/3 × BPDia), where BPSys was the systolic blood pressure and BPDia the diastolic blood pressure.

The gain factor (GF) was calculated using the following formula: GF = 1 – ((TPintervention × d4intervention)/(TPbaseline × d4baseline) − 1)/((TPintervention – TPbaseline)/TPbaseline), where d is the arterial resting diameter, TP the transmural pressure estimated as 2/3 × MAP – IOP, and the intervention is regadenoson administration, hypoxia, or a combination of these. When GF <1, the change in blood pressure results in a diameter response, so that blood flow increases, and when GF >1, these changes lead to a decrease in blood flow, whereas GF = 1 indicates that a change in blood pressure results in a change in the diameter so that the blood flow is kept constant [10].

Statistical Analysis

Students' paired t test was used to test whether MAP and IOP changed significantly by regadenoson administration, whether the systemic arterial oxygen saturation changed during breathing of the hypoxic gas mixture, and whether systemic hypoxia changed the diameter of the retinal vessels significantly.

One-sample t test was used to test if the GF differed significantly from 1. Repeated measures one-way ANOVA was used to test for differences between the GF. Repeated measures two-way ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons was used to test for differences in the resting diameters and the diameter changes during hypoxia of retinal arterioles and venules, with flicker stimulation as the one variable and regadenoson as the other variable. The multiple comparisons were performed using Fisher's least significant difference test.

Results

During breathing of the hypoxic gas mixture, the systemic arterial oxygen saturation decreased significantly from (mean ± SEM) 99.3 ± 0.2 to 87.8 ± 0.9% (p < 0.0001) and increased significantly after regadenoson administration during both normoxia from 99.3 ± 0.2 to 99.6 ± 0.2% (p = 0.02) and during hypoxia from 87.8 ± 0.9 to 93.6 ± 0.5% (p < 0.0001). The IOP showed no significant change during breathing of the hypoxic gas mixture (p = 0.06) but increased significantly from 17.2 ± 1.0 before to 22.9 ± 1.1 mm Hg (p < 0.0001) after regadenoson administration. The MAP was not affected significantly by any of the interventions (p > 0.05 for all comparisons).

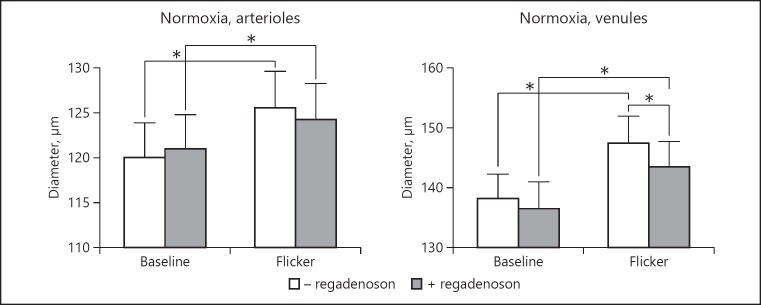

Figure 3 shows that during normoxia the diameter of retinal arterioles and venules increased significantly during stimulation with flickering light, both before and after regadenoson administration (p < 0.0001 for all comparisons). Regadenoson reduced the flicker-induced dilatation of venules (p = 0.0006), but otherwise had no significant effect on vessel diameters (p > 0.08 for all other comparisons).

Fig. 3.

Diameters of retinal arterioles and venules during normoxia, at baseline and during flicker stimulation, before and after administration of regadenoson. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). Error bars indicate SEM.

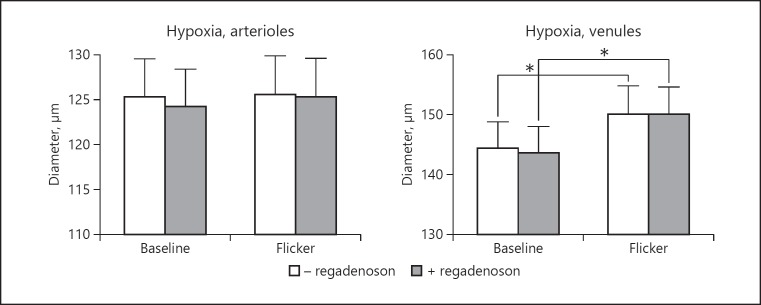

Figure 4 shows diameters of retinal vessels during hypoxia. Hypoxia significantly increased the diameter of retinal arterioles and venules at baseline (p < 0.0008 for both comparisons). Flicker stimulation significantly increased the diameter of venules (p < 0.0001) but not of arterioles (p = 0.50). Regadenoson had no effect on the diameters at any of the interventions (p > 0.26 for all comparisons).

Fig. 4.

Diameters of retinal arterioles and venules during hypoxia, at baseline and during flicker stimulation, before and after administration of regadenoson. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). Error bars indicate SEM.

There was no significant difference (p = 0.6) between the GF during the interventions which was (mean ± SEM) 0.28 ± 0.36 during regadenoson administration, 0.58 ± 1.52 during hypoxia, and −0.85 ± 1.35 during the two interventions together. None of the GF values deviated significantly from one or zero (p > 0.06 for all comparisons).

Discussion

The present interventional study using the adenosine A2A receptor agonist regadenoson was performed on younger normal individuals, which ensured that diameter changes of retinal arterioles would not be reduced by the increased stiffness of the vessels that occurs with age [11]. It is a limitation that the diameter responses were obtained after short-term interventions on oxygenation, metabolism, and adenosine receptors, which probably differ from the long-term responses that might be active in normal and pathological diameter responses of retinal vessels in vivo. The rate of degradation of regadenoson implied that the plasma concentration had declined significantly already 1–4 min after intravenous administration of the compound [9]. Accordingly, measurements of the vessel diameter had to be performed rapidly after the administration of the compound, as is required for the diagnostic use of regadenoson in cardiology [12]. However, it was unnecessary to use continuous infusion of the compound that is pertinent for the study of vasoactive effects of adenosine which is degraded within seconds [8].

Stimulation of the retina with flickering light increases metabolism and leads to hypoxia in the retinal tissue [13], whereas hypoxia induced by breathing of a hypoxic gas mixture and administration of regadenoson also affects the systemic vascular system that supplies the retina. These effects may include changes in systemic oxygen saturation and IOP, as observed in the present study. The diameter response of retinal arterioles during hypoxic breathing should ideally be corrected for such effects, and the influence of the IOP can be corrected by calculating the GF. If this factor is 1, it can be concluded that changes in the diameter of retinal resistance vessels are balancing changes in the driving blood pressure so that the blood flow is kept constant [14]. The variability of the calculated GF values in the present study may have obscured possible differences in this parameter among the interventions. However, a lack of influence of the systemic circulation on the findings is supported by the finding of no significant difference between the GF calculated from the changes in arterial diameter and driving blood pressure from baseline to flicker stimulation and systemic hypoxia with and without regadenoson administration.

The fact that flicker stimulation increased the diameter of both retinal arterioles and venules during normoxia and venules during hypoxia confirms previous findings [15, 16]. The lack of effect of flicker stimulation on the diameter of arterioles during hypoxia is analogous to studies showing that changes in oxygen saturation are correlated with changes in flicker-induced dilatation of retinal arterioles during both hypoxia [15, 16, 17] and hyperoxia [18]. The reduction in flicker-induced dilatation of retinal venules induced by regadenoson during normoxia may be a similar paradoxical effect, where a potential dilating stimulus reduces the effect of another dilating stimulus [16]. The mechanisms underlying these diameter responses of retinal vessels when flicker stimulation is added to hypoxia or regadenoson administration require further investigation.

Previous in vivo studies have shown that intravenous infusion of adenosine can increase the pulse amplitude in the central retina and the blood flow in the choroid and the optic nerve head, which can be assumed to be a result of vasodilatation in the choroidal resistance vessels [7]. The observed lack of effect of the adenosine analogue regadenoson on the diameter of retinal arterioles may potentially be due to a too low concentration of the compound for a vasoactive effect to have been elicited. Although the employed concentration of regadenoson can affect coronary function [8, 19], the sensitivity of retinal arterioles to the compound may be lower than that of arterioles in the systemic circulation [20]. Previous studies have shown that adenosine has affinity to a number of adenosine receptor types [21] and that the dilating effect of the compound requires functional Na-K pumps and KATP channels [22]. Additionally, adenosine may be a final common mediator of other compounds with vasodilating properties such as glutamate and ATP [23, 24]. Alternatively, the lack of effect on retinal vessels may be related to the route of administration of regadenoson. Thus, it has been shown that adenosine-induced dilatation of retinal vessels requires that the compound is administered extravascularly [5, 6], whereas intravascular administration of the compound has no effect on vessel diameter [25] or blood flow in the retina [26, 27]. This is in accordance with the present in vivo findings where intravascular administration of regadenoson had no effect on the diameter of larger retinal vessels. Therefore, it might be hypothesized that a vasoactive effect of regadenoson could be achieved if the compound was administered intravitreally to act on the extraluminal side of the vessels as observed with adenosine in newborn pigs [28]. This hypothesis should be investigated further.

In conclusion, the present study has shown that intravenous administration of the adenosine A2Areceptor agonist regadenoson has no effect on the diameter of retinal arterioles but can reduce flicker-induced dilatation of venules during normoxia in normal persons in vivo. Future studies should investigate differential effects of intra- and extravascular administration of specific adenosine receptor agonists. This might point to possible roles for adenosine receptors as targets for the treatment of retinal vascular disease such as diabetic retinopathy.

Statement of Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Scientific Ethics, the Danish Health and Medicines Agency, and the Danish Data Protection Agency, and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants before enrolment.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The study was supported by the VELUX Foundation, the Jochum and Marie Jensen Foundation, the August Frederik Wedell Erichsen Foundation, and the Synoptik Foundation.

Author Contributions

L.P., H.E.B., and T.B. conceived the idea; A.D.J., L.P., and H.E.B. performed the experiments; A.D.J., L.P., and T.B. analysed the data; and A.D.J., L.P., H.E.B., and T.B. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Research Nurse Karin Møller Pedersen is thanked for qualified assistance during the investigations.

References

- 1.Chen K, Zhao BS, He C. Nucleic acid modifications in regulation of gene expression. Cell Chem Biol. 2016 Jan;23((1)):74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mishra P, Chan DC. Metabolic regulation of mitochondrial dynamics. J Cell Biol. 2016 Feb;212((4)):379–87. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201511036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerrero A. A2A adenosine receptor agonists and their potential therapeutic applications. An update. Curr Med Chem. 2018;25((30)):3597–612. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666180313110254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liou GI, Ahmad S, Naime M, Fatteh N, Ibrahim AS. Role of adenosine in diabetic retinopathy. J Ocul Biol Dis Infor. 2011 Jun;4((1-2)):19–24. doi: 10.1007/s12177-011-9067-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riis-Vestergaard MJ, Misfeldt MW, Bek T. Dual effects of adenosine on the tone of porcine retinal arterioles in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014 Mar;55((3)):1630–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hein TW, Yuan Z, Rosa RH, Jr, Kuo L. Requisite roles of A2A receptors, nitric oxide, and KATP channels in retinal arteriolar dilation in response to adenosine. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005 Jun;46((6)):2113–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polska E, Ehrlich P, Luksch A, Fuchsjäger-Mayrl G, Schmetterer L. Effects of adenosine on intraocular pressure, optic nerve head blood flow, and choroidal blood flow in healthy humans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003 Jul;44((7)):3110–4. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al Jaroudi W, Iskandrian AE. Regadenoson: a new myocardial stress agent. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Sep;54((13)):1123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garnock-Jones KP, Curran MP. Regadenoson. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2010;10((1)):65–71. doi: 10.2165/10489040-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frederiksen CA, Jeppesen P, Knudsen ST, Poulsen PL, Mogensen CE, Bek T. The blood pressure-induced diameter response of retinal arterioles decreases with increasing diabetic maculopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006 Oct;244((10)):1255–61. doi: 10.1007/s00417-006-0262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeppesen P, Gregersen PA, Bek T. The age-dependent decrease in the myogenic response of retinal arterioles as studied with the Retinal Vessel Analyzer. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004 Nov;242((11)):914–9. doi: 10.1007/s00417-004-0945-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Medicines Agency Rapiscan (regadenoson) Retrieved October 10, 2018 https://www.ema.europa.eu/medicines/human/EPAR/rapiscan.

- 13.Riva CE, Logean E, Falsini B. Visually evoked hemodynamical response and assessment of neurovascular coupling in the optic nerve and retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2005 Mar;24((2)):183–215. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaya MY, Petersen L, Bek T. Lack of effect of nitroglycerin on the diameter response of larger retinal arterioles in normal persons during hypoxia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016 Feb;254((2)):277–83. doi: 10.1007/s00417-015-3227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen L, Bek T. Diameter changes of retinal arterioles during acute hypoxia in vivo are modified by the inhibition of nitric oxide and prostaglandin synthesis. Curr Eye Res. 2015 Jul;40((7)):737–43. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2014.954676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen L, Bek T. Preserved pressure autoregulation but disturbed cyclo-oxygenase and nitric oxide effects on retinal arterioles during acute hypoxia in diabetic patients without retinopathy. Ophthalmologica. 2016;235((2)):114–20. doi: 10.1159/000443147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palkovits S, Told R, Boltz A, Schmidl D, Popa Cherecheanu A, Schmetterer L, et al. Effect of increased oxygen tension on flicker-induced vasodilatation in the human retina. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014 Dec;34((12)):1914–8. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osol G, Halpern W. Myogenic properties of cerebral blood vessels from normotensive and hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1985 Nov;249((5 Pt 2)):H914–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.5.H914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iskandrian AE, Bateman TM, Belardinelli L, Blackburn B, Cerqueira MD, Hendel RC, et al. ADVANCE MPI Investigators Adenosine versus regadenoson comparative evaluation in myocardial perfusion imaging: results of the ADVANCE phase 3 multicenter international trial. J Nucl Cardiol. 2007 Sep-Oct;14((5)):645–58. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2007.06.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao G, Linke A, Xu X, Ochoa M, Belloni F, Belardinelli L, et al. Comparative profile of vasodilation by CVT-3146, a novel A2A receptor agonist, and adenosine in conscious dogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003 Oct;307((1)):182–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ralevic V, Burnstock G, Verkhratsky A. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev. 1998 Sep;50((3)):413–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeppesen P, Aalkjaer C, Bek T. Adenosine relaxation in small retinal arterioles requires functional Na-K pumps and K(ATP) channels. Curr Eye Res. 2002 Jul;25((1)):23–8. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.25.1.23.9966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmgaard K, Aalkjaer C, Lambert JD, Bek T. N-methyl-D-aspartic acid causes relaxation of porcine retinal arterioles through an adenosine receptor-dependent mechanism. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008 Oct;49((10)):4590–4. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmgaard K, Aalkjaer C, Lambert JD, Bek T. ATP-induced relaxation of porcine retinal arterioles depends on the perivascular retinal tissue and acts via an adenosine receptor. Curr Eye Res. 2007 Apr;32((4)):353–9. doi: 10.1080/02713680701229646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alder VA, Su EN, Yu DY, Cringle SJ, Yu PK. Asymmetrical response of the intraluminal and extraluminal surfaces of the porcine retinal artery to exogenous adenosine. Exp Eye Res. 1996 Nov;63((5)):557–64. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Portellos M, Riva CE, Cranstoun SD, Petrig BL, Brucker AJ. Effects of adenosine on ocular blood flow. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995 Aug;36((9)):1904–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirao M, Oku H, Goto W, Sugiyama T, Kobayashi T, Ikeda T. Effects of adenosine on optic nerve head circulation in rabbits. Exp Eye Res. 2004 Nov;79((5)):729–35. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gidday JM, Park TS. Microcirculatory responses to adenosine in the newborn pig retina. Pediatr Res. 1993 Jun;33((6)):620–7. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199306000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]