Abstract

Background

Postnatal growth restriction in very-preterm infants (VPIs) may have long-lasting effects. Recent evidence suggests that developmental problems in VPIs are related to abnormalities in intestinal microbial communities.

Objective

To investigate the effect on growth outcomes in VPIs of supplementation with Bifidobacterium along with mother's colostrum and breast milk.

Methods

A randomized controlled study was performed on 35 VPIs, born between 24 and 31 weeks of gestation with birth weights <1,500 g. The patients received either daily Bifidobacterium breve supplementation (Bifid group) or vehicle supplement only (placebo group). Parenteral nutrition was initiated with glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids for all of the infants soon after birth. Each infant received their own mother's colostrum within 24 h of birth, and breast milk on subsequent days. Fecal bacteria, organic acids, pH, bile acids, and plasma fatty acids were analyzed.

Results

Seventeen infants were allocated to the Bifid group and 18 to the placebo group; the birth weights and gestational ages did not differ significantly between the two groups. Compared to the placebo group, the Bifid group showed significantly greater and earlier weight gain by 8 weeks; significantly higher total fecal bacterial counts, including bifidobacteria; higher levels of total fecal short-chain fatty acids and nominally (but not significantly) higher concentrations of plasma n−3 fatty acids; and lower levels of total fecal bile acid.

Conclusions

Bifidobacterial supplementation of maternal colostrum and breast milk yielded the establishment of a beneficial microbiota profile, leading to favorable metabolic responses that appeared to provide improved growth in VPIs.

Keywords: Very-preterm infants, Bifidobacterium supplementation, Breast milk, Microbiota, Weight gain

What Is It About?

To investigate the effect on growth outcomes in very-preterm infants (VPIs), supplementation with Bifidobacterium along with mother's colostrum and breast milk was performed on 35 VPIs. Seventeen infants allocated to the bifidobacterial group, in comparison to 18 in the placebo group, showed significantly greater cumulative weight gain by 8 weeks, associated with significantly higher fecal bacterial counts including bifidobacteria and short-chain fatty acids, and nominally higher concentrations of n−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. The conclusive findings demonstrate that Bifidobacterium supplementation of maternal colostrum and breast milk establishes a beneficial microbiota profile, leading to favorable metabolic responses that improve growth in VPIs.

Introduction

Preterm infants are predisposed to serious health complications in both the short and the long term. These effects are due to prematurity and nutrition affecting maturation of the gut microbiota, the gastrointestinal tract, and the immune system. These consequences of prematurity subsequently influence growth and development of the infants [1, 2, 3]. Therefore, preterm infants would benefit from enhanced weight gain, which affects growth and organ development. For this purpose, breast milk is the preferred source of nutrition for preterm infants [4, 5].

Organic acids (short-chain fatty acids and lactic acid) are the end products of bifidobacterial fermentation, particularly of human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs). In the gut, these organic acids can be absorbed into the circulation, where these acids serve as both microbiota-generated calories and important regulatory molecules, such that the host has been estimated to receive 6–10% (or more in infants) of their energy from organic acids [6]. Bile acids are formed by the microbiota from host cholesterol, and these molecules also serve as signaling molecules that bind to distinct receptors [7] that have major impacts on metabolism.

The composition of the gut microbiota thus may be taken to represent a very important contributor, particularly in low-birth-weight infants, to normal growth and development. On this basis, our aim was to investigate the effects of Bifidobacterium supplementation concomitant with early feeding of mother's colostrum and breast milk in very-preterm infants (VPIs), focusing in particular on growth outcomes. We also analyzed the levels of fecal bacterial and related fecal parameters in these infants.

Subjects and Methods

Study Design and Participants

In this blinded, randomized, controlled study, we recruited infants born between 24 and 31 weeks of gestation and with body weights <1,500 g who had been admitted to the NICU (neonatal intensive care unit) of the Okinawa Prefectural Nanbu Children's Medical Center.

The clinical information gathered on each participant included diet and antibiotic administration. The infants were alternately allocated to either of two groups within 24 h of birth, receiving either Bifidobacterium breve supplementation (Bifid group) or vehicle supplement only (placebo group).

Nutritional Management

Parenteral nutrition (PN), by which the infants were provided with glucose (8%; glucose infusion rate: 3–4 mg/kg/day), amino acids (1–1.5 g/kg/day), and fatty acids (Intralipos; high content of n−6: ∼0.5–1 g/kg/day), was initiated for all the infants within the first few hours of life. Each infant received their own mother's colostrum as a trophic feeding within 24 h of birth and breast milk on subsequent days; these feedings were augmented with PN according to the infant's tolerance. PN was stopped when infants tolerated 120 mL/kg/day of enteral feeding and showed sustained growth, defined by gaining at least 15 g/kg/day during the preceding 72 h. All infants were fed their mother's breast milk fortified with HMS-1 (Morinaga, Tokyo, Japan) and medium-chain triglyceride oil. When a mother was not able to supply a sufficient volume of her own breast milk, the infant was nourished partially with preterm formula (GP-P; Morinaga).

Bifidobacterium Supplementation

The infants were provided with once-daily supplementation with B. breve (BBG-01) or an equivalent volume of placebo. BBG-01, a probiotic supplement provided by Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), was packaged as a powder, freeze-dried with corn starch, in a 1-g sachet containing not less than 109 viable cells (CFU [colony-forming units]) of B. breve-strain Yakult bacteria [8]. The vehicle supplement, which consisted of corn starch alone, was provided as an identical powder in identical sachets. The content of each sachet was suspended in 4 mL of water and the corn starch was allowed to settle; 1 mL of the resulting supernatant (containing 2.5 × 108 CFU of the probiotic) was administered via a gastric feeding tube. The placebo was formulated and administered using the same procedure. Dosing was initiated within several hours after birth and continued once daily during the hospital stay. Antibiotics were used primarily to prevent infections due to tracheal intubation or use of a central venous catheter.

Fecal specimens for bacterial analysis were collected on day 1 (meconium), as well as 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks after birth. RNA [9] and DNA [10] were isolated from the fecal specimens using the previously described methods. Bacterial counts were determined using the Yakult Intestinal Flora-SCAN® (YIF-SCAN® [8]; Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd.), a technique that employs the reverse-transcription quantitative PCR [9]. For enumeration of the B. breve strain Yakult, a strain-specific quantitative PCR technique was used [11]. The fecal specimens were tested for fecal organic acid concentrations and pH using the previously described methods [12]. Fecal bile acid profiles were analyzed using liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry [13]. Plasma levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) such as n−3 (eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid) and n−6 (arachidonic acid [AA]) were measured with capillary gas chromatography [14] (SRL, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) using blood obtained from the umbilical cord at birth and at 4 weeks of age.

Primary outcomes included body weight gain and the composite of the measured fecal and plasma outcomes during 8 weeks postpartum. Secondary outcome measures were incidences of serious clinical complications such as necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) or sepsis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS statistics software version 22 (SPSS Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). For between-group comparisons, the two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (for fecal microbiota and organic acid levels) or the two-tailed, unpaired Student t test (for fecal pH, fecal bile acids, and plasma fatty acids) was used to compare differences in continuous variables; the two-tailed Fisher exact probability test was used to compare differences in categorical variables. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Unless otherwise indicated, data are presented as mean ± SD.

Results

Between June 1, 2015, and September 30, 2017, 35 VPIs (17 extremely-low-birth-weight [ELBW] and 18 very-low-birth-weight [VLBW] infants) were recruited to the study; 17 were allocated to the Bifid group and 18 to the placebo group (Table 1). The baseline and early clinical characteristics of the included infants and details on the feedings received in the first few weeks of life were similar between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline and early characteristics of the study participants

| BBG-01 group | Placebo group | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants (male/female) | 17 (6/15) | 18 (7/10) |

| Gestational age, weeks | 28.1±3.1 | 28.2±3.3 |

| Birth weight, g (ELBWI:LBWI, n) | 1,049±302 (8:9) | 1,002±289 (9:9) |

| Cesarean delivery | 14 (82.3%) | 15 (83.3%) |

| 5-min Apgar score <6* | 6.4±1.6 | 4.7±1.9 |

| Artificial ventilation | 14 (82.3%) | 16 (88.8%) |

| Duration of ventilation, days* | 11.9±14.1 | 30.7±21.1 |

| Intrauterine infection | ||

| Chorioamnionitis | 3 (17.6%) | 5 (27.8%) |

| PROM >24 h | 4 (23.5%) | 2 (11.1%) |

| IgM >10 | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Antibiotics | ||

| Antibiotics in newborns | Ampicillin + amikacin | Ampicillin + amikacin |

| Early nutrition characteristics | ||

| Parenteral nutrition started | Within a few hours after birth in all | Within a few hours after birth in all |

| Enteral feeding started | Trophic feeding on 1st day in all | Trophic feeding on 1st day in all |

| Type of milk received | ||

| Breast milk plus formula, mixed, n (% of all infants) | 3 (17.6%) | 4 (22.2%) |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | 14 (82.4%) | 13 (72.2%) |

| Fortification | ||

| Added breast milk fortifier started, day of life | 12.9±4.5 | 13.9±3.2 |

| Added MCT oil started, day of life | 10.5±4.0 | 11.4±3.8 |

Values are presented as n (%) or mean ± SD unless stated otherwise. ELBWI, extremely-low-birth-weight infant; IgM, immunoglobulin M; LBWI, low-birth-weight infant; MCT, medium-chain triglyceride; PROM, premature rupture of membranes; SD, standard deviation. * Significant difference (p > 0.05).

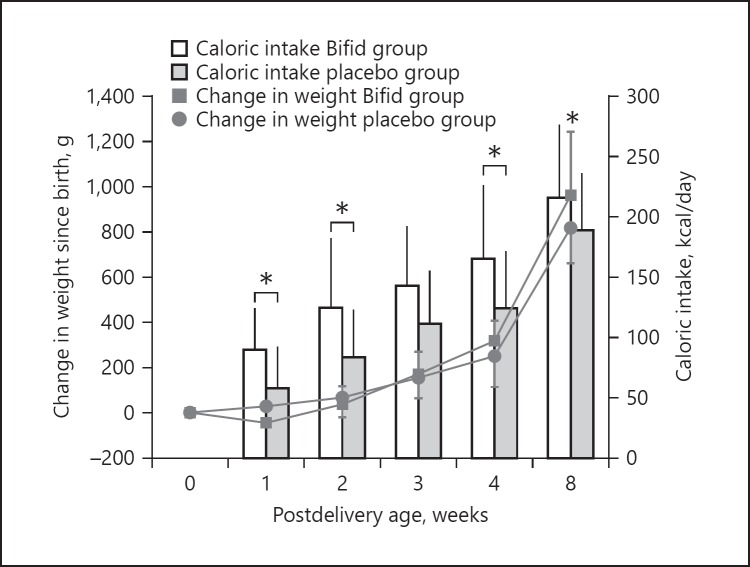

The Bifid group exhibited “catch-up” weight gain, resulting in a significantly larger cumulative body weight gain by 8 weeks (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1) compared to the placebo group. Similarly, the average daily caloric intake by the BBG-01-fed infants was significantly higher at 1, 2, and 4 weeks compared to the placebo group at the respective time points (Fig. 1). This trend continued at 8 weeks (122.6 vs. 119.0 kcal/kg/day for the Bifid and the placebo group, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Change in weight and caloric intake following birth. The BBG-01-fed group (Bifid group) exhibited a significantly greater body weight gain associated with higher caloric intake (compared to the placebo group) by 8 weeks of life (two-tailed, unpaired Student's t test, * p < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Sepsis was observed in 3 infants (16.7%) in the placebo group and no infants in the Bifid group, but this difference did not achieve significance. No infants in either group developed NEC.

Fecal Microbiota

The fecal microbiota analysis results are shown in Table 2. The total bacterial counts in meconium were similar in the two groups. In the meconium of the two groups, almost no obligate anaerobes, including Bifidobacterium, were found, but facultative anaerobes such as Lactobacillus were detected. At 1 week of life, the total fecal bacterial count in the Bifid group was significantly elevated to 109 cells/g feces (compared to the count in the placebo group at the same time point), and Bifidobacterium was the predominant genus among the bacteria in the Bifid group. However, the total bacterial count in the placebo group did not reach 1010 cells/g feces by 8 weeks of life. The colonization of the placebo group with BBG-01 was suspected to represent contamination that presumably occurred during the formulation and administration processes.

Table 2.

Changes in fecal microbiota counts and prevalence in preterm infants during the first 8 weeks after birth

| Meconium |

Week 1 |

Week 2 |

Week 4 |

Week 8 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBG-01 (14)* counta, % | placebo (14) count, % | BBG-01 (11) count, % | placebo (12) count, % | BBG-01 (16) count, % | placebo (15) count, % | BBG-01 (17) count, % | placebo (18) count, % | BBG-01 (15) count, % | placebo (15) count, % | |

| Total bacteria | 6.9±2.5 (79) | 7.0±2.2 (86) | 9.4±1.4b (100) | 8.3±1.7 (100) | 9.9±0.7 (100) | 8.8±1.9 (100) | 10.0±0.6b (100) | 9.3±0.9 (100) | 10.1±0.5 (100) | 9.7±0.8 (100) |

| Obligate anaerobes | ||||||||||

| Clostridium coccoides group | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) |

| Clostridium leptum subgroup | ND (0) | 5.3±0.1 (14) | ND (0) | 5.3 (17) | 5.4 (6) | 5.3 (7) | 6.4 (6) | 5.5 (6) | 5.8±0.3 (27) | 5.9±0.6 (20) |

| Bacteroides fragilis group | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) |

| Bifidobacterium | 7.7±2.1 (21) | ND (0) | 9.0±1.5 (91)cc | 9.9 (8) | 9.6±1.0 (100)cc | 10.5±0.5 (27) | 9.4±1.1 (100)cc | 8.7±2.4 (22) | 9.4±1.7 (93)cc | 9.4±1.1 (60) |

| Atopobium cluster | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) |

| Prevotella | ND (0) | ND (0) | 5.2 (9) | 5.4 (8) | 5.3 (6) | ND (0) | 5.6 (12) | ND (0) | ND (0) | 5.5 (7) |

| Clostridium perfringens | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) |

| Clostridium difficile | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | 7.8 (8) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | 5.2 (13) |

| Facultative anaerobes | ||||||||||

| Enterobacteriaceae | 7.8±1.7 (36) | 7.8±2.0 (50) | 8.8±1.2 (64) | 7.6±1.9 (83) | 8.0±1.4 (63) | 8.1±1.5 (67) | 8.8±1.4 (88) | 8.2±1.9 (89) | 9.2±1.1 (87) | 9.3±0.9 (93) |

| Enterococcus | 6.8±3.2 (29) | 9.2 (14) | 8.3±1.4 (55) | 8.2±2.0 (50) | 7.9±2.0 (56) | 7.7±2.2 (33) | 8.5±1.5 (59) | 7.9±2.1 (67) | 7.0±1.9 (53) | 7.7±1.7 (80) |

| Staphylococcus | 5.5±1.5 (64) | 5.5±1.7 (64) | 7.6±1.4 (100) | 7.0±1.5 (100) | 7.3±1.6 (100) | 7.6±1.6 (100) | 7.5±1.0 (100) | 7.3±1.0 (100) | 7.2±1.0 (100) | 6.9±1.3 (100) |

| Lactobacillus | 3.3±0.7 (21) | 3.3 (14) | 4.6 (9) | 3.8 (17) | 3.5±1.1 (25) | 4.1 (13) | 3.9 (6) | 4.4±1.2 (22) | 3.9±0.5 (20) | 4.8±2.1 (27) |

| Aerobes | ||||||||||

| Pseudomonas | 4.2 (7) | ND (0) | 5.7 (18) | 4.2 (8) | 4.2 (13) | 4.0 (7) | 4.4±0.5 (18) | 5.1±0.7 (17) | 4.1 (7) | 5.7±0.8 (20) |

| Administered bacteria | ||||||||||

| Bifidobacterium breve strain Yakult | 7.1 (7) | ND (0) | 8.5±0.8 (91)cc | ND (0) | 8.8±0.8 (100)cc | 9.7 (13) | 8.7±0.7 (100)cc | 9.2 (6) | 8.4±1.0 (87)cc | 9.1±0.7 (27) |

Preterm infants with a birth weight <1,500 g. ND, not detected.

For all columns: number of samples examined (%; bacterial detection rate).

For all columns: log10 cells/g feces, mean ± SD (SD is not presented for bacteria detected in 2 subjects or fewer).

p < 0.05 (vs. placebo), two-tailed non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test.

p < 0.01 (vs. placebo), two-tailed Fisher's exact probability test.

Fecal Organic Acid Concentrations and pH

The total organic acid concentrations in the meconium did not differ significantly between the two groups, but these values were significantly lower than those in healthy term infants [12]. In the Bifid group, from 1 to 8 weeks of life, the fecal concentrations of total organic acid, and those of lactic and acetic acids, were significantly elevated (Table 3), but the fecal pH values were significantly lower, compared with the values in the placebo group at the respective time points. The concentrations of the other organic acids were low or undetectable in the fecal samples from both groups.

Table 3.

Changes in fecal organic acid levels, pH, total bile acids, and plasma fatty acids in preterm infants during the first 8 weeks after birth

| Meconium |

Week 1 |

Week 2 |

Week 4 |

Week 8 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic acids | BBG-01 (16)* counta, % | placebo (15) count, % | BBG-01 (14) count, % | placebo (14) count, % | BBG-01 (17) count, % | placebo (17) count, % | BBG-01 (17) count, % | placebo (18) count, % | BBG-01 (15) count, % | placebo (17) count, % |

| Total organic | ||||||||||

| acids in feces, µmol/g feces | 16.2±13.5 (100) | 19.0±21.5 (93) | 30.3±21.2b (100) | 9.4±8.5 (100) | 32.9±24.4 (100) | 19.6±24.8 (100) | 36.7±20.0b (100) | 23.3±14.5 (100) | 52.3±29.8b (100) | 35.9±27.4 (100) |

| Succinic acid | 3.3 (13) | 8.9±15.3 (20) | 1.8±3.1 (43) | 1.4 (14) | 1.5±1.7 (76) | 2.2±2.1 (41) | 5.0±3.6 (76) | 3.6±2.8 (72) | 4.4±3.5 (80) | 5.1±3.3 (94) |

| Lactic acid | 2.8±1.8 (56) | 1.3±0.6 (40) | 8.0±4.2b (71) | 2.1±0.4 (29) | 10.6±8.7 (76) | 8.0±11.8 (65) | 6.3±4.5 (88) | 6.4±5.6 (72) | 10.8±17.6 (100) | 7.4±8.1 (82) |

| Formic acid | 2.2 (13) | 0.6±0.5 (40) | 3.2±3.0 (57) | 0.5±0.2 (36) | 2.6±1.5 (53) | 1.9±1.5 (47) | 1.5±1.8 (29) | 0.8±0.6 (28) | 1.5±1.6 (53) | 1.6±1.5 (35) |

| Acetic acid | 14.6±13.5 (88) | 16.2±18.6 (93) | 21.9±15.7b (100) | 8.1±8.7 (100) | 22.0±16.6 (100) | 12.6±14.2 (100) | 25.6±15.2b (94) | 14.5±10.3 (100) | 35.1±18.1bb (100) | 22.2±18.6 (100) |

| Propionic acid | 18.3 (6) | ND (0) | ND (0) | 1.2 (7) | 1.5±0.2 (18) | 0.9 (6) | 4.2±4.7 (59) | 2.7±2.3 (50) | 2.9±2.2 (73) | 3.2±2.1 (71) |

| Butyric acid | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) | 0.1 (7) | ND (0) | ND (0) | 4.8 (6) | ND (0) | ND (0) | ND (0) |

| Meconium |

Week 4 |

Week 8 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bile acids | BBG-01 (9) | placebo (10) | BBG-01 (16) | Placebo (10) | BBG-01 (12) | Placebo (10) | |||||

| Total bile acids in feces, µmol/g | 8.64±2.6 | 8.99±5.1 | 0.27±0.2b | 2.78±1.3 | 0.26±0.36b | 2.19±0.9 | |||||

| Umbilical cord |

Week 4 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty acids in plasma | BBG-01 (16) | placebo (18) | BBG-01 (13) | placebo (17) | ||||||

| DGLA, µg/mL | 36.7±18 | 31.7±13 | 51.8±9b | 46.4±21 | ||||||

| AA, µg/mL | 156.2±41 | 164.9±61 | 172.2±46 | 179.4±83 | ||||||

| EPA, µg/mL | 7.5±4 | 5.8±2 | 18.1±10 | 15.8±7 | ||||||

| DHA, µg/mL | 57.5±26 | 48.9±17 | 72.0±26 | 66.7±22 | ||||||

Preterm infants with a body weight <1,500 g. ND, not detected.

For all columns: number of samples examined (%: bacterial detection rate).

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01 (vs. placebo), non-parametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, two-tailed unpaired Student's t test.

Plasma PUFA Concentrations

The concentrations of plasma n−6 PUFAs and n−3 PUFAs in the infants of the two groups exhibited nominal increases from the first day through 4 weeks of life (Table 3). A comparison of the 4-week values between the two groups indicated that the concentrations of all of these fatty acids (with the exception of AA) were nominally higher in the Bifid group.

Fecal Bile Acid Concentration

The values of total bile acid in the Bifid group at 4 and 8 weeks of life were significantly lower than those in the placebo group at the respective time points (Table 3).

Discussion and Conclusion

We here present comprehensive data from a double-blind, randomized, controlled study of B. breve supplementation concomitant with early feeding with maternal colostrum and breast milk during the first 8 weeks postpartum in ELBW and VLBW infants with birth weights <1,500 g.

VPIs are known to suffer from various deficiencies in intestinal functions leading to increased susceptibility to inflammatory diseases [1, 2, 3]. Colostrum contains a larger range of growth factors, anti-inflammatory components, and anti-infective components than mature milk [15]. Higher concentrations of specific HMOs, including α1,2 fucosylated oligosaccharides, in human colostrum may be linked to protection of newborns from NEC-related pathogens [5, 16]. Therefore, it would be greatly desirable to initiate trophic feeding using the mother's colostrum in ELBW and VLBW infants, as was done in the present study; notably, neither NEC nor sepsis developed in the B. breve supplementation group.

We found that the fecal Bifidobacterium in the Bifid group became the dominant species among the fecal bacteria from 1 week of life, an effect that persisted, together with increasing commensal bacterial numbers, until 8 weeks of life. Consistent with the dominance of Bifidobacterium, the total fecal organic acid concentrations were significantly elevated in the Bifid group. The significantly larger cumulative weight gain in the Bifid group by 8 weeks of life was consistent with the observation of higher caloric intake in infants provided with Bifidobacterium supplementation. Notably, the increased number of bacteria in the distal intestine is expected to facilitate the fermentation of undigested carbohydrates (e.g., HMOs) to produce additional short-chain fatty acids, which in turn can be utilized for de novo synthesis of lipids and glucose [17, 18, 19] for use as the main energy source by the host. The concentrations of all of the measured plasma n−3 and n−6 PUFAs (with the exception of AA) exhibited an upward trend from birth to 4 weeks of life, an effect that was nominally greater in the Bifid group than in the control group; this observation may contribute, at least in part, to the higher caloric intake by the Bifidobacterium-supplemented infants.

Bacteria in the small intestine generate deconjugated bile acids, which enhance fat digestion and absorption. Bile acids then are absorbed through high-affinity active transport in the distal ileum, known as an enterohepatic circulation, but some amount of bile acid escapes into the large intestine and is lost in the feces. This bile acid metabolism appeared to result in a significant decrease in the total fecal bile acid concentration in the Bifid group, probably due to more efficient enterohepatic circulation of the increased levels of deconjugated bile acids [20]. Indeed, bile acids now are appreciated to serve as versatile signaling molecules that bind to distinct receptors known as TGR5 and FXR, both of which have a major impact on host metabolism, including energy and glucose homeostasis [21].

The above-mentioned results of the present study establish a causal relationship between the state of microbial community development and improved growth in infants, in particular VPIs.

Our study had at least two limitations. First, this study was a single-center study where the hospital staff and the included patients and their parents may not have been free from bias related to administration of BBG-01 or placebo. Second, the sample size and the duration of this study may not have been sufficient to fully evaluate the effects of BBG-01 supplementation. However, our results demonstrated that early bifidobacterial (BBG-01) supplementation, together with parenteral support and early enteral feeding with the infants' own mothers' colostrum and breast milk, may be associated with improved short-term growth outcomes, highlighting the benefits of microbiota establishment in preterm infants. While BBG-01 supplementation appeared to provide considerable energy from organic acids, as well as the beneficial effects of fatty acids and bile acids, these effects alone may not be sufficient to explain the infants' “catch-up” in cumulative weight gain. However, to our knowledge, there are no reports of adverse safety issues associated with BBG-01 supplementation [22].

In conclusion, bifidobacterial supplementation, concomitant with early feeding with maternal colostrum and breast milk, yielded the establishment of a beneficial microbiota profile. The associated changes in fecal organic acid levels, fecal pH, and bile acid levels appeared to provide improved growth in preterm infants.

Statement of Ethics

Written parental consent was obtained for all participants. All research was performed according to the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration, and the trial protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committees of both the Children's Medical Center and the Juntendo University Hospital. This clinical trial was performed following registration with the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/; registration No. UMIN000005412).

Disclosure Statement

T. Takahashi, H. Tsuji, and T. Asahara are salaried employees of Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by a grant from Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

Author Contributions

T. Oshiro: data collection, analysis, and interpretation; Y. Yamashiro: study design, manuscript editing, and supervision; T. Takahashi: supplying resources and manuscript drafting. All other authors analyzed the measurements of the investigated subjects.

Acknowledgments

We thank the physicians, nurses, dietitians, and enrolled patients and their families at the participating NICU (Department of Pediatric Neonatology, Okinawa Prefectural Nanbu Medical Center and Children's Medical Center, Okinawa, Japan) for their cooperation and assistance in conducting the trial. We also express our sincere appreciation to Norikatsu Yuki, Akira Takahashi, and Yukiko Kado of the Yakult Central Institute for their help with the analyses of intestinal microbiota and measurements of fecal organic acid concentrations and pH values.

References

- 1.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Adams-Chapman I, Fanaroff AA, Hintz SR, Vohr B, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network Neurodevelopmental and growth impairment among extremely low-birth-weight infants with neonatal infection. JAMA. 2004 Nov;292((19)):2357–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saigal S, Stoskopf B, Streiner D, Paneth N, Pinelli J, Boyle M. Growth trajectories of extremely low birth weight infants from birth to young adulthood: a longitudinal, population-based study. Pediatr Res. 2006 Dec;60((6)):751–8. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000246201.93662.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kusuda S, Fujimura M, Uchiyama A, Totsu S, Matsunami K, Neonatal Research Network, Japan Trends in morbidity and mortality among very-low-birth-weight infants from 2003 to 2008 in Japan. Pediatr Res. 2012 Nov;72((5)):531–8. doi: 10.1038/pr.2012.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dallas DC, Smink CJ, Robinson RC, Tian T, Guerrero A, Parker EA, et al. Endogenous human milk peptide release is greater after preterm birth than term birth. J Nutr. 2015 Mar;145((3)):425–33. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.203646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moles L, Manzano S, Fernández L, Montilla A, Corzo N, Ares S, et al. Bacteriological, biochemical, and immunological properties of colostrum and mature milk from mothers of extremely preterm infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Jan;60((1)):120–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNeil NI. The contribution of the large intestine to energy supplies in man. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984 Feb;39((2)):338–42. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/39.2.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawamata Y, Fujii R, Hosoya M, Harada M, Yoshida H, Miwa M, et al. A G protein-coupled receptor responsive to bile acids. J Biol Chem. 2003 Mar;278((11)):9435–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okazaki T, Asahara T, Yamataka A, Ogasawara Y, Lane GJ, Nomoto K, et al. Intestinal microbiota in pediatric surgical cases administered Bifidobacterium breve: A randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016 Jul;63((1)):46–50. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuda K, Tsuji H, Asahara T, Matsumoto K, Takada T, Nomoto K. Establishment of an analytical system for the human fecal microbiota, based on reverse transcription-quantitative PCR targeting of multicopy rRNA molecules. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009 Apr;75((7)):1961–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01843-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Fujimoto J, Kado Y, Takada T, Matsumoto K, et al. Quantitative PCR with 16S rRNA-gene-targeted species-specific primers for analysis of human intestinal bifidobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004 Jan;70((1)):167–73. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.167-173.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujimoto J, Tanigawa K, Kudo Y, Makino H, Watanabe K. Identification and quantification of viable Bifidobacterium breve strain Yakult in human faeces by using strain-specific primers and propidium monoazide. J Appl Microbiol. 2011 Jan;110((1)):209–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuji H, Oozeer R, Matsuda K, Matsuki T, Ohta T, Nomoto K, et al. Molecular monitoring of the development of intestinal microbiota in Japanese infants. Benef Microbes. 2012 Jun;3((2)):113–25. doi: 10.3920/BM2011.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naritaka N, Suzuki M, Sato H, Takei H, Murai T, Kurosawa T, et al. Profile of bile acids in fetal gallbladder and meconium using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chim Acta. 2015 Jun;446:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozawa A, Takayanagi K, Fujita T, Hirai A, Hamazaki T, Terano T, et al. Tamura Yasushi, Kumagai A. Determination of long chain fatty acids in human total plasma lipids using gas chromatography (in Japanese with English abstract) Bunseki Kagaku. 1982;31((2)):87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner CL. Amniotic fluid and human milk: a continuum of effect? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002 May;34((5)):513–4. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200205000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Underwood MA, Gaerlan S, De Leoz ML, Dimapasoc L, Kalanetra KM, Lemay DG, et al. Human milk oligosaccharides in premature infants: absorption, excretion, and influence on the intestinal microbiota. Pediatr Res. 2015 Dec;78((6)):670–7. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolever TM, Brighenti F, Royall D, Jenkins AL, Jenkins DJ. Effect of rectal infusion of short chain fatty acids in human subjects. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989 Sep;84((9)):1027–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimura I, Ozawa K, Inoue D, Imamura T, Kimura K, Maeda T, et al. The gut microbiota suppresses insulin-mediated fat accumulation via the short-chain fatty acid receptor GPR43. Nat Commun. 2013;4((1)):1829. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergman EN. Energy contributions of volatile fatty acids from the gastrointestinal tract in various species. Physiol Rev. 1990 Apr;70((2)):567–90. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vlahcevic ZR, Heuman DM, Hylemon PB. Physiology and pathophysiology of enterohepatic circulation of bile acids. In: Zakim D, Boyer T, editors. Hepatology: A Textbook of Liver Disease. 3rd ed. Volume 1. Philadelphia (PA): Sunders; 1996. pp. 376–417. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas C, Pellicciari R, Pruzanski M, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K. Targeting bile-acid signalling for metabolic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008 Aug;7((8)):678–93. doi: 10.1038/nrd2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitajima H, Hirano S. Safety of Bifidobacterium breve (BBG-01) in preterm infants. Pediatr Int (Roma) 2017 Mar;59((3)):328–33. doi: 10.1111/ped.13123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]