Abstract

Background

Estimating population-level obesity rates is important for informing policy and targeting treatment. The current gold standard for obesity measurement in the U.S. – the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) – samples < 0.1% of the population and does not target state- or health system-level measurement.

Objective

To assess the feasibility of using body mass index (BMI) data from the electronic health record (EHR) to assess rates of overweight and obesity and compare these rates to national NHANES estimates.

Research Design

Using outpatient data from 42 clinics, we studied 388,762 patients in a large health system with at least one primary care visit in 2011–2012.

Measures

We compared crude and adjusted overweight and obesity rates by age category and ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic, Other) between EHR and NHANES participants. Adjusted overweight (BMI≥25) and obesity rates were calculated via a two-step process. Step one accounted for missing BMI data using inverse probability weighting, while step two included a post-stratification correction to adjust the EHR population to a nationally representative sample.

Results

Adjusted rates of obesity (BMI≥30) for EHR patients were 37.3% (95% CI 37.1–37.5) compared to 35.1% (95% CI 32.3–38.1) for NHANES patients. Among the 16 different obesity class, ethnicity and gender strata that were compared between EHR and NHANES patients, 14 (87.5%) contained similar obesity estimates (i.e. overlapping 95% CIs).

Conclusions

Electronic health records may be an ideal tool for identifying and targeting patients with obesity for implementation of public health and/or individual level interventions.

Keywords: obesity, electronic health records, health-services research

INTRODUCTION

Analysis of electronic health record (EHR) data has the potential to revolutionize how research and patient care are conducted given the massive amount of data that are available for analysis and measurement. One benefit of EHR analyses is that they can identify associations at the health system level that will promote diagnostic and therapeutic interventions at the health system or individual level. EHR data have been used to identify individuals at risk of developing cardiovascular disease1 and diabetes2 with the goal of improving detection and treatment of these conditions before they harm patients. Researchers have also used EHR data to study chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,3 asthma,4 depression,5 and chronic pain.6

Obesity is an ideal disease to target for EHR analyses. It is a leading cause of early mortality in the U.S.7 and, along with its related co-morbidities, costs billions of dollars to treat each year.8 Obesity is also readily identifiable in the EHR given that the criterion for its diagnosis – assessment of body mass index (BMI) - is simple to measure and record during clinic visits. Several studies using EHR data have focused on childhood obesity9 and its association with socioeconomic factors.10–12 Studies on adults have targeted improvement in obesity documentation in the EHR,13–17 community-level determinants of obesity,18 and the likelihood of weight loss maintenance over time.19

One criticism of these analyses has been that selection bias may exist because the sample of patients represented in an EHR dataset may be different than the general population. Flood and colleagues recently investigated this issue for childhood obesity and found that EHR analyses that were weighted and adjusted to account for bias were similar to those documented in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).9 NHANES is widely considered to be the gold standard measurement tool for obesity in the U.S. given that it is the only survey that is nationally representative and includes in-person height and weight measurement rather than self-reports.

In this study, we used EHR data from 42 clinics in a large health care system to identify adults who were overweight or obese and had been evaluated at least once in a primary care clinic. We then compared overweight and obesity rates in the EHR dataset to NHANES survey participants to examine the amount of agreement between samples. We hypothesized that, after adjusting for demographic differences, the prevalence of obesity according to gender and ethnicity would be similar between the two cohorts.

METHODS

We used data from the University of Wisconsin Public Health Information Exchange (PHINEX) database, which includes a HIPAA Privacy Rule compliant limited data set from more than 500,000 patients who are seen in 42 clinics operated by the University of Wisconsin Departments of Family Medicine, Pediatrics, and Internal Medicine.4,20 Each patient in the PHINEX database has at least one documented encounter with a primary care practitioner (family medicine, internal medicine or pediatrics) since 2007. To de-identify each patient, personally identifying information was removed, date of birth was transformed to birth month, and address was transformed to the census block group. Epic EHR Clarity Database (EpicCare Electronic Medical Record, Epic Systems Corp., Verona WI) was the data source for all patients.

Study population

Adult patients in the PHINEX dataset who attended at least one primary care clinic visit between 2011 and 2012 were included in the analysis. This time frame was selected so that our results could be compared to the most recent analysis of NHANES patients, which was published in 2014 by Ogden and colleagues and includes data from the same time period.21 Patients within the PHINEX dataset were excluded if they were younger than 20 years or had missing data on either race/ethnicity or census block group.

Study variables

Patient characteristics: Patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, type of insurance, census block group of residence during 2012, and BMI were included in the PHINEX dataset. Categorization of patient age followed the scheme described in the Ogden analysis (≥20, 20–39, 40–59, ≥ 60 years). Patient race/ethnicity was categorized as White (non-Hispanic), Black (non-Hispanic), Other (non-Hispanic), and Hispanic. Insurance type included commercial, Medicare, Medicaid, or no insurance. Census block group (600- to 1500- person neighborhoods) was generated by geocoding each patient’s address in the EHR using ESRI® ArcGIS software.22,23 BMI was calculated according to height and weight measurements (weight [kg] / height [m]2) that were documented during the most recent patient encounter in the EHR in 2011 and 2012. If height was missing during that encounter, it was filled in with the median of all height values from the patient’s other encounters as an adult. Patients were then categorized as overweight (BMI 25–29.9) or class I (BMI 30–34.9), II (35–39.9), or III (≥40) obese. If a patient had multiple BMI values present in the EHR from 2011–2012, the last one was selected. If no BMI data were available for a patient, this was coded as missing data. Imputation for missing BMI values was not performed.

Community characteristics: Urbanicity and economic hardship index (EHI) were calculated at the census block group level and linked to the patient’s location of residence. Urbanicity was defined as urban (1–4), suburban (5–8) and rural (9–11) based on the classification system described by ESRI®.24 EHI values, which were based on 5-year estimates from the U.S. Census American Community Survey (2007–2011), were calculated using the Nathan and Adams technique,25,26 which includes six variables: 1) unemployment: percent of people age >16 years who are unemployed; 2) dependency: percent of the population age <18 or >64 years; 3) education: percent of people age >25 without a high school education; 4) income level: per capita income; 5) crowded housing: percent of occupied housing units with more than one person per room; 6) poverty: percent of households below 125% of low-income level. Scores were normalized for all Wisconsin census block groups and ranged from 0 to 100 (100 indicating the maximal degree of comparative hardship).

Analysis

Unadjusted obesity rates from the PHINEX dataset were calculated according to obesity class, age, sex, and ethnicity. Weighted obesity rates from PHINEX were calculated via a two-step process that has been described elsewhere.9 The first step accounted for PHINEX patients with missing BMI data. An inverse probability weighting was performed via a multivariable logistic regression with age (category), race, insurance type, urbanicity, and EHI as predictors and presence of BMI data (yes/no) as the outcome. The final model was chosen via stepwise selection with inclusion of variables at a p-value <0.05. Thus, any patient selected from the PHINEX dataset with covariate value X would have a probability of p(X) that the patient’s BMI information would be present. Patients with covariate value X and BMI data that were not missing represented 1/p(X) patients from the PHINEX dataset. Given this relationship, patients with no missing BMI data could represent similar patients with missing BMI data.27

The second step involved a post-stratification correction28 to adjust the population of patients in the PHINEX dataset into a nationally representative sample using 2012 national census data.29 The inverse probability weight (from the first step) and the post-stratification correction (from the second step) were then multiplied to create a final weight for each patient. Unadjusted and weighted PHINEX obesity rates were reported along with 95% confidence intervals according to age, sex, and race.

Scatterplots were used to visualize the relationship between NHANES and weighted PHINEX rates as well as crude and weighted PHINEX rates. A 45 degree “identity line” was displayed in the scatter plots for a point of reference. Spearman’s rank correlations and a Bland-Altman30 analysis were performed to measure the strength of these relationships.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC). STrengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were followed.31 This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Medicine and Public Health IRB M-2009–1273.

RESULTS

Data from 388,762 patients were included in the analysis. A comparison of crude PHINEX and NHANES sample sizes according to age category, sex, and race/ethnicity is shown in Table 1. The mean sample size for each stratum was 57 times larger (min 3; max 236) for the PHINEX cohort compared to NHANES.

Table 1.

| Age, y | All | White (non-Hispanic) | Black (non-Hispanic) | Other# (non-Hispanic) | Hispanic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHINEX | NHANES | PHINEX | NHANES | PHINEX | NHANES | PHINEX | NHANES | PHINEX | NHANES | |

| Male | ||||||||||

| 20–39 | 66,524 | 941 | 56,713 | 329 | 3,307 | 222 | 3,307 | 154 | 3,197 | 196 |

| 40–59 | 65,034 | 826 | 59,020 | 295 | 2,849 | 215 | 1,624 | 127 | 1,541 | 165 |

| ≥60 | 38,253 | 818 | 36,620 | 337 | 576 | 225 | 633 | 84 | 424 | 154 |

| Female | ||||||||||

| 20–39 | 82,788 | 867 | 70,990 | 301 | 3,812 | 200 | 4,339 | 148 | 3,647 | 185 |

| 40–59 | 71,350 | 901 | 65,624 | 287 | 2,311 | 276 | 1,884 | 136 | 1,531 | 182 |

| ≥60 | 45,250 | 828 | 43,311 | 350 | 661 | 226 | 745 | 84 | 533 | 155 |

Only includes patients with at least one BMI value recorded in the dataset

Includes non-Hispanic “Other” PHINEX dataset patients and non-Hispanic “Asian” NHANES patients.

In multivariable logistic regression analyses, older age, female sex, non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity, commercial insurance/Medicaid status versus no insurance, urban area dwellers compared to suburban or rural, and living in an area with a lower economic hardship index were associated with having a BMI recorded (all p<0.001).

PHINEX estimates of overweight and obesity rates

At least one BMI value was present in the dataset for 59.6% (n=192,039) of patients. Females comprised 57.6% (n=110,514) of this cohort. White, Black, Hispanic and Other-race patients comprised 91.2%, 3.3%, 2.4% and 3.1% of the group, respectively. Nearly three-fourths had commercial insurance, while 21.7% had Medicare or Medicaid. More than half (52.4%) lived in a suburban setting, while 28.7% and 19.0% lived in urban or rural settings, respectively.

70.0% (95% CI 69.8–70.2) of adults were overweight or obese, while 37.3% (95% CI 37.1–37.5) were obese (Table 3). The prevalence of severe obesity (class II or III) was 17.0% (95% CI 16.8.−17.1) (Table 4). Black adults had the highest rates of overweight and obesity. 19.6% (95% CI 17.5–21.7) of Black females age 40–59 had class III obesity, compared to 10.5% (95% CI 8.6–12.5) of Hispanic females, 10.0% (95% CI 9.7–10.3) of White females, and 2.3% (95% CI 1.5–3.2) of Other females in the same age category (Table 4).

Table 3.

Prevalence of Overweight or Class I Obesity for Adults Aged 20 or Older by Sex, Age, and Race (PHINEX*, 2011–2012)

| Prevalence Estimate (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted | 20–39y (Crude) | 40–59y (Crude) | >=60y (Crude) | |

| Overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25) | ||||

| All races | ||||

| All | 70.0 (69.8–70.2) | 62.7 (62.3–63.1) | 75.2 (74.9–75.5) | 72.7 (72.4–73.1) |

| Male | 75.4 (75.1–75.7) | 67.2 (66.6–67.8) | 81.8 (81.4–82.3) | 78.2 (77.7–78.8) |

| Female | 64.9 (64.6–65.2) | 58.2 (57.7–58.7) | 68.8 (68.3–69.2) | 68.2 (67.7–68.7) |

| White (non-Hispanic) | ||||

| All | 69.1 (68.9–69.4) | 59.4 (58.9–59.8) | 74.2 (73.9–74.5) | 73.0 (72.7–73.4) |

| Male | 76.3 (76.0–76.6) | 65.6 (65.0–66.3) | 82.8 (82.4–83.2) | 79.9 (79.4–80.4) |

| Female | 62.4 (62.1–62.7) | 52.9 (52.4–53.5) | 65.7 (65.2–66.2) | 67.4 (66.8–67.9) |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | ||||

| All | 77.3 (76.3–78.3) | 72.9 (71.2–74.6) | 82.3 (80.8–83.7) | 77.0 (74.3–79.7) |

| Male | 74.2 (72.5–75.9) | 68.8 (65.8–71.8) | 79.9 (77.6–82.2) | 75.2 (71.1–79.3) |

| Female | 80.0 (78.7–81.3) | 76.8 (74.9–78.8) | 84.3 (82.4–86.2) | 78.3 (74.7–82.0) |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | ||||

| All | 54.2 (52.9–55.5) | 50.0 (48.2–51.8) | 58.8 (56.7–61.0) | 54.7 (51.5–57.9) |

| Male | 60.1 (58.2–62.0) | 56.0 (53.1–58.9) | 66.7 (63.6–69.8) | 57.0 (52.4–61.7) |

| Female | 49.0 (47.3–50.6) | 44.5 (42.2–46.8) | 51.9 (49.1–54.7) | 52.9 (48.5–57.2) |

| Hispanic | ||||

| All | 74.8 (73.5–76.0) | 70.1 (68.3–72.0) | 81.4 (79.5–83.2) | 75.4 (72.0–78.8) |

| Male | 78.4 (76.5–80.2) | 74.1 (71.3–76.9) | 85.2 (82.6–87.7) | 77.7 (72.6–82.8) |

| Female | 71.1 (69.4–72.8) | 65.7 (63.2–68.2) | 77.6 (74.9–80.2) | 73.6 (68.9–78.3) |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30) | ||||

| All races | ||||

| All | 37.3 (37.1–37.5) | 32.0 (31.6–32.3) | 42.0 (41.6–42.4) | 38.1 (37.7–38.5) |

| Male | 37.3 (36.9–37.6) | 31.4 (30.8–32.0) | 42.5 (41.9–43.0) | 38.4 (37.8–39.0) |

| Female | 37.3 (37.0–37.6) | 32.5 (32.0–33.0) | 41.5 (41.1–42.0) | 37.8 (37.2–38.3) |

| White (non-Hispanic) | ||||

| All | 36.2 (35.9–36.4) | 28.8 (28.4–29.2) | 40.8 (40.4–41.2) | 38.0 (37.6–38.4) |

| Male | 37.7 (37.4–38.1) | 29.7 (29.1–30.3) | 43.2 (42.7–43.8) | 39.5 (38.9–40.1) |

| Female | 34.7 (34.4–35.0) | 27.9 (27.4–28.4) | 38.4 (37.9–38.9) | 36.8 (36.3–37.4) |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | ||||

| All | 50.1 (48.9–51.3) | 45.8 (43.9–47.7) | 56.0 (54.1–57.9) | 48.0 (44.8–51.3) |

| Male | 41.1 (39.2–43.0) | 37.5 (34.4–40.6) | 46.4 (43.6–49.3) | 38.5 (33.9–43.1) |

| Female | 57.9 (56.3–59.5) | 53.6 (51.3–56.0) | 64.3 (61.8–66.8) | 54.8 (50.3–59.2) |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | ||||

| All | 20.0 (19.0–21.0) | 19.2 (17.7–20.6) | 21.5 (19.7–23.2) | 19.0 (16.5–21.5) |

| Male | 19.1 (17.5–20.6) | 18.3 (16.0–20.6) | 21.3 (18.6–24.0) | 16.6 (13.1–20.1) |

| Female | 20.8 (19.4–22.1) | 19.9 (18.1–21.8) | 21.7 (19.3–24.0) | 20.9 (17.4–24.5) |

| Hispanic | ||||

| All | 39.5 (38.1–40.9) | 36.3 (34.3–38.2) | 44.8 (42.5–47.2) | 38.1 (34.2–42.0) |

| Male | 39.8 (37.7–42.0) | 36.6 (33.6–39.7) | 44.5 (40.9–48.1) | 40.6 (34.6–46.6) |

| Female | 39.2 (37.3–41.0) | 35.9 (33.4–38.5) | 45.2 (42.0–48.3) | 36.1 (31.0–41.2) |

PHINEX=University of Wisconsin Public Health INformation EXchange database

Table 4.

Prevalence of Class II and III Obesity for Adults Aged 20 or Older by Sex, Age, and Race (PHINEX*, 2011–2012)

| Prevalence Estimate (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted | 20–39y (Crude) | 40–59y (Crude) | >=60y (Crude) | |

| Obesity class II and III (BMI ≥ 35) | ||||

| All races | ||||

| All | 17.0 (16.8–17.1) | 14.8 (14.5–15.1) | 19.7 (19.4–20.0) | 16.1 (15.8–16.4) |

| Male | 14.5 (14.3–14.8) | 12.5 (12.1–13.0) | 17.1 (16.7–17.5) | 13.7 (13.3–14.1) |

| Female | 19.2 (19.0–19.5) | 17.1 (16.7–17.5) | 22.2 (21.8–22.6) | 18.1 (17.6–18.5) |

| White (non-Hispanic) | ||||

| All | 16.2 (16.0–16.4) | 13.1 (12.8–13.4) | 18.9 (18.6–19.1) | 16.2 (15.9–16.5) |

| Male | 14.7 (14.5–15.0) | 11.7 (11.2–12.1) | 17.5 (17.1–18.0) | 14.5 (14.1–14.9) |

| Female | 17.6 (17.4–17.8) | 14.6 (14.2–15.0) | 20.1 (19.7–20.5) | 17.6 (17.1–18.0) |

| Black(non-Hispanic) | ||||

| All | 27.4 (26.3–28.5) | 26.1 (24.4–27.7) | 31.0 (29.2–32.7) | 23.3 (20.6–26.1) |

| Male | 19.0 (17.5–20.6) | 19.2 (16.6–21.7) | 21.2 (18.9–23.6) | 14.1 (10.8–17.4) |

| Female | 34.6 (33.0–36.1) | 32.6 (30.4–34.8) | 39.5 (37.0–42.0) | 29.9 (25.8–33.9) |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | ||||

| All | 6.6 (5.9–7.2) | 7.0 (6.1–7.9) | 6.6 (5.5–7.6) | 5.6 (4.1–7.1) |

| Male | 6.1 (5.2–7.1) | 6.3 (4.9–7.7) | 6.4 (4.7–8.0) | 5.1 (3.0–7.1) |

| Female | 7.0 (6.1–7.8) | 7.6 (6.4–8.8) | 6.7 (5.3–8.2) | 6.0 (4.0–8.1) |

| Hispanic | ||||

| All | 16.3 (15.2–17.4) | 14.8 (13.4–16.2) | 19.8 (17.9–21.7) | 13.2 (10.4–15.9) |

| Male | 13.6 (12.1–15.1) | 12.8 (10.7–15.0) | 16.1 (13.5–18.7) | 10.0 (6.3–13.6) |

| Female | 19.0 (17.6–20.5) | 17.0 (15.0–18.9) | 23.5 (20.8–26.2) | 15.7 (11.8–19.5) |

| Obesity Class III (BMI ≥ 40) | ||||

| All races | ||||

| All | 7.4 (7.3–7.5) | 6.7 (6.5–6.9) | 8.8 (8.6–9.0) | 6.3 (6.1–6.5) |

| Male | 5.5 (5.4–5.7) | 5.1 (4.8–5.4) | 6.7 (6.4–7.0) | 4.5 (4.2–4.7) |

| Female | 9.1 (8.9–9.3) | 8.4 (8.1–8.7) | 10.8 (10.5–11.1) | 7.9 (7.6–8.2) |

| White (non-Hispanic) | ||||

| All | 6.9 (6.8–7.0) | 5.7 (5.5–5.9) | 8.4 (8.2–8.6) | 6.3 (6.1–6.5) |

| Male | 5.5 (5.3–5.6) | 4.5 (4.2–4.8) | 6.8 (6.5–7.1) | 4.7 (4.5–5.0) |

| Female | 8.2 (8.1–8.4) | 6.9 (6.6–7.2) | 10.0 (9.7–10.3) | 7.5 (7.3–7.8) |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | ||||

| All | 13.0 (12.1–13.8) | 13.2 (11.9–14.5) | 14.3 (12.9–15.6) | 10.0 (8.0–11.9) |

| Male | 7.5 (6.5–8.5) | 7.9 (6.1–9.6) | 8.2 (6.7–9.8) | 5.1 (3.0–7.1) |

| Female | 17.7 (16.5–18.9) | 18.2 (16.4–20.0) | 19.6 (17.5–21.7) | 13.4 (10.4–16.5) |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | ||||

| All | 2.4 (2.0–2.8) | 2.8 (2.2–3.4) | 2.3 (1.7–3.0) | 1.7 (0.9–2.5) |

| Male | 2.3 (1.7–2.9) | 2.6 (1.6–3.5) | 2.4 (1.3–3.4) | 1.5 (0.3–2.6) |

| Female | 2.5 (2.0–3.0) | 2.9 (2.2–3.7) | 2.3 (1.5–3.2) | 1.9 (0.7–3.1) |

| Hispanic | ||||

| All | 7.2 (6.5–8.0) | 6.7 (5.7–7.7) | 8.6 (7.3–9.9) | 5.5 (3.7–7.4) |

| Male | 5.7 (4.7–6.8) | 5.7 (4.3–7.2) | 6.7 (4.9–8.5) | 2.9 (0.9–5.0) |

| Female | 8.7 (7.7–9.8) | 7.8 (6.4–9.2) | 10.5 (8.6–12.5) | 7.6 (4.8–10.4) |

PHINEX=University of Wisconsin Public Health INformation EXchange database

PHINEX vs. NHANES estimates of overweight and obesity rates

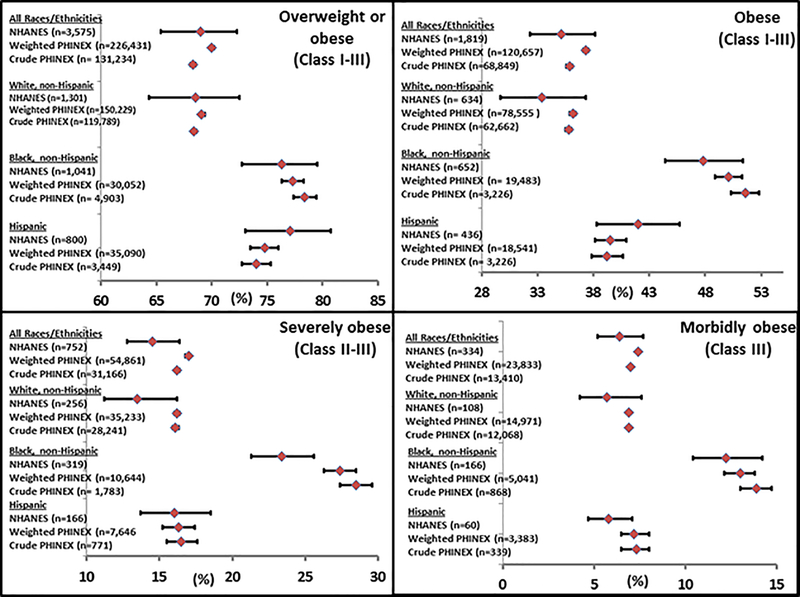

Among the 16 different obesity class, ethnicity and gender strata that were compared between EHR and NHANES patients, 14 (87.5%) contained similar obesity estimates (i.e. overlapping 95% CIs; Figure 1). PHINEX dataset confidence intervals were smaller for all estimates. For example, 68.5% (95% CI 64.3–72.5) of White adults in NHANES had a BMI ≥ 25 versus 69.1% (95% CI 68.9–69.4) and 68.4% (95% CI 68.2–68.6) in the weighted and crude PHINEX analyses, respectively.

Figure 1.

Overweight and obesity rates for NHANES, weighted PHINEX, and crude PHINEX (2011–2012)

There were small differences between the PHINEX and NHANES participants with Class II or III obesity, particularly for Black adults. Only 23.4% (95% CI 21.3–25.6) of Black adults in NHANES had Class II or III obesity vs. 27.4% (95% CI 26.3–28.5) in the weighted PHINEX analysis and 28.5% (95% CI 27.4–29.6) in the crude PHINEX analysis. Class III obesity estimates were statistically similar between NHANES and PHINEX participants.

Crude and weighted PHINEX overweight and obesity rates were plotted by ethnicity, gender and BMI cutoff (Supplemental Digital Content). Overweight and obesity rates for NHANES and PHINEX participants were also plotted. The Spearman rank correlation coefficients for these two analyses were 0.996 and 0.997, respectively. Bland-Altman analyses indicated that the mean difference between crude PHINEX and weighted PHINEX rates was 0.23 (95% limit of agreement between −1.72 to 2.17); the mean difference between NHANES and weighted PHINEX rates was 2.55 (95% limit of agreement from −5.98 to 11.08).

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that the electronic health record may be a useful tool for assessing adult obesity at the individual and health system level. Compared to NHANES, which is considered the gold standard obesity measurement instrument in the U.S., adjusted rates of overweight and obesity in our EHR dataset were similar in 14 of 16 obesity class and ethnicity strata. Sample sizes in the EHR dataset were, on average, 50 times larger within each stratum which allowed for more precise estimates (smaller confidence intervals) than the NHANES dataset.

Having accurate and actionable obesity data available at the population level is critical. Historically, obesity trends in the U.S. have been assessed by surveys, which track obesity along with other determinants of health, such as smoking and dietary habits. Nationally, the CDC administers NHANES, which includes personal interviews, physical exams, laboratory testing and nutritional assessments.32 CDC also administers the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) through personal household interviews.33 Findings from the recently published 2015 NHIS survey documented a 30.4% obesity rate in the U.S., a record high.34

At the state-level, the CDC leads the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), which is a cross-sectional telephone survey conducted by state health departments.35 For 2014, BRFSS data indicated that the obesity rate was 31.2% in Wisconsin.36 The Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW) has also been available for the past 20 years.37 Administered by the University of Wisconsin-Madison, SHOW includes annual household surveys of Wisconsin residents who are followed longitudinally and is modeled after NHANES. Analyses of more than 3,000 SHOW participants from 2008–2013 reveal a 39.4% rate of obesity in Wisconsin,38 a 20% increase compared to the BRFSS telephone survey data for Wisconsin.

While each of the aforementioned survey instruments is valuable, they all have their limitations. NHANES and SHOW include actual measurement of height and weight to generate an individual’s BMI, they require household visits and are relatively expensive. According to the CDC, expenses for NHANES are more than $30 million annually, and there are concerns about whether funding will be adequate in the future.39 This limits the number of individuals NHANES can sample, which is approximately 5,000 people annually in 15 counties across the U.S.39 The NHIS and BRFSS, on the other hand, obtain their BMI estimates by asking participants about their height and weight, either in person or via the telephone, respectively. One concern with this type of self-reporting is that it may underestimate obesity prevalence rates because participants tend to overestimate their height and underestimate their weight.40

One benefit of using EHR data to identify patients with obesity is that it does not require significant amounts of additional investment. While the initial purchase of the EHR may cost millions for large health systems,41 EHR studies can be completed by analytics personnel and/or researchers at that institution. Further, calculation of BMI does not require additional clinical effort outside of what is already occurring in clinical care, as height and weight measurements are obtained as part of routine clinical care.

A second benefit of EHR analyses is that they provide actionable information at both the individual and health system levels. For example, in this analysis, which included data from 2011 and 2012, 40% of patients in the EHR did not have a BMI recorded. By comparison, more than 95% of patients in the Veterans Health Administration system were screened for obesity using BMI in 2010.42 Health system-level education and training of providers and information technology solutions might be effective in improving BMI measurement during primary care visits. Baer and colleagues recently reported the results of their cluster-randomized trial of 23 clinical teams which assessed the impact of adding features to the EHR that were designed to improve outpatient assessment and management of obesity.43

Obesity data from the EHR could also be used to target high risk individuals. Zimmerman and colleagues examined the feasibility of using the EHR to identify pre-diabetic patients and provide lifestyle modification counseling.2 Of those who did not have a diagnosis of diabetes, more than half were identified as pre-diabetic in the EHR analysis and fewer than one-third had documentation of lifestyle counseling by a provider. The authors concluded that EHR-initiated patient outreach could be effective. Patients with severe obesity who have recently developed an obesity-related comorbidity, such as diabetes, or gained a significant amount of weight could trigger an alert to the primary care provider to discuss obesity treatment options. This type of intervention is not feasible with state and national surveys given that they are not directly incorporated into a health system.

Our study has several important limitations. BMI data were manually entered by health care professionals and may be less reliable than data explicitly obtained for research or public health purposes, where data are typically double-entered and subjected to validity checks. Further, we did not impute BMI for the 40% of patients with missing BMI data. We weighted the sample for missing data and adjusted the population distribution to reflect a nationally representative population. This weighting technique could have introduced bias into the results although Figure 1 suggests that the impact of weighting the PHINEX rates was modest. Further, unmeasured confounding may be present our stepwise logistic regression model, and thus our results may not be generalizable to other datasets.

Selection bias may exist given that patients who visited a primary care provider in 2011 or 2012 may have been different from those who did not. Although rates were similar between EHR and NHANES patients for nearly all ethnicities and obesity classes, weighted PHINEX rates were generally higher than NHANES rates. This difference was most pronounced for non-Hispanic Black adults with severe obesity who had adjusted PHINEX rates that were 4% points higher than NHANES. This may reflect selection bias in either the EHR dataset or NHANES, given that NHANES generated national obesity estimates using data from only 5,181 patients (3% of the EHR sample size). Alternatively, both datasets may reflect the populations they were designed to measure.

When obesity class, sex and race-ethnicity risk sets were arrayed by prevalence magnitude, this study suggested that there was little selection bias when a large clinical population (PHINEX) was compared to a nationally representative non-clinical population (NHANES). Adjusted and crude estimates of the clinic population were all very near to the 1:1 “identity line” (Spearman rank correlation 0.996), and similar results were found when adjusted clinical population estimates were compared to weighted NHANES (Spearman rank correlation 0.977). In this comparison, fourteen of the 16 risk sets demonstrated excellent agreement, as indicated by minimal mean differences in the Bland-Altman analyses. The two risk sets with the greatest disagreement were sub-populations that were likely to have a higher intrinsic heterogeneity between PHINEX and NHANES: non-Hispanic Other males and females. These findings replicate other studies4,9 demonstrating good agreement between non-clinical populations and electronic health record derived prevalence estimates. Despite this, it is possible that national obesity rates are impacted by geographic region independent of the patient characteristics we have analyzed. This could limit the generalizability of this study.

In summary, the electronic health record may be an ideal tool for identifying and targeting patients with obesity who may benefit from population or individual-based interventions, such as public health campaigns, behavioral interventions, or bariatric surgery. Given the limitations of state and national-level survey instruments, providers, health systems, and health services researchers should consider using EHR analyses as a source of real-time data to improve the care that is offered to patients with obesity.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental digital content. Crude PHINEX rates and NHANES rates compared to weighted PHINEX rates according to BMI class

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study population with a BMI value recorded (n=192,039)

| Gender | |

| Female | 57.6% (110,514) |

| Male | 42.4% (81,525) |

| Age category | |

| 20–39 | 30.7% (58,879) |

| 40–59 | 39.2% (75,231) |

| ≥60 | 30.1% (57,929) |

| Race | |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 91.2% (175,182) |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 3.3% (6,255) |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | 3.1% (5,941) |

| Hispanic | 2.4% (4,661) |

| Insurance type | |

| Commercial | 75.9% (145,831) |

| Medicare/ Medicaid | 21.7% (41,714) |

| No Insurance | 2.3% (4,494) |

| Urbanicity | |

| Urban | 28.7% (55,052) |

| Suburban | 52.4% (100,569) |

| Rural | 19.0% (36,418) |

| Economic Hardship Index | |

| Median score (IQR) | 24.2 (21.6–27.2) |

| BMI category | |

| Underweight (<18) | 0.9% (1,706) |

| Normal weight (18–24.9) | 30.8% (59,099) |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 32.5% (62,385) |

| Class I obesity (30–34.9) | 19.6% (37,683) |

| Class II obesity (35–39.9) | 9.3% (17,756) |

| Class III obesity (≥40) | 7.0% (13,410) |

Acknowledgments

Disclosure of funding: Effort on this study was made possible by a Research Career Scientist award from the Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) Health Services Research & Development Service to Dr. Voils (RCS 14-443). The research reported/outlined here was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service. Dr. Funk is a VA HSR&D Career Development awardee at the Madison VA. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Hanrahan and was supported by Mission Aligned Management Allocation Funds from the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest for the past three years.

This work has not been presented elsewhere.

References

- 1.Persell SD, Dunne AP, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Electronic health record-based cardiac risk assessment and identification of unmet preventive needs. Med Care 2009;47:418–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmermann LJ, Thompson JA, Persell SD. Electronic health record identification of prediabetes and an assessment of unmet counselling needs. J Eval Clin Pract 2012;18:861–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Price D, West D, Brusselle G, et al. Management of COPD in the UK primary-care setting: an analysis of real-life prescribing patterns. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014;9:889–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomasallo CD, Hanrahan LP, Tandias A, et al. Estimating Wisconsin asthma prevalence using clinical electronic health records and public health data. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Innes H, Lewsey J, Smith DJ. Predictors of admission and readmission to hospital for major depression: A community cohort study of 52,990 individuals. J Affect Disord 2015;183:10–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tian TY, Zlateva I, Anderson DR. Using electronic health records data to identify patients with chronic pain in a primary care setting. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013;20:e275–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 2004;291:1238–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, et al. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w822–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flood TL, Zhao YQ, Tomayko EJ, et al. Electronic health records and community health surveillance of childhood obesity. Am J Prev Med 2015;48:234–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nau C, Schwartz BS, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Community socioeconomic deprivation and obesity trajectories in children using electronic health records. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23:207–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomayko EJ, Flood TL, Tandias A, et al. Linking electronic health records with community-level data to understand childhood obesity risk. Pediatr Obes 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz BS, Stewart WF, Godby S, et al. Body mass index and the built and social environments in children and adolescents using electronic health records. Am J Prev Med 2011;41:e17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baer HJ, Cho I, Walmer RA, et al. Using electronic health records to address overweight and obesity: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2013;45:494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bordowitz R, Morland K, Reich D. The use of an electronic medical record to improve documentation and treatment of obesity. Fam Med 2007;39:274–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krist AH, Woolf SH, Frazier CO, et al. An electronic linkage system for health behavior counseling effect on delivery of the 5A’s. Am J Prev Med 2008;35:S350–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schriefer SP, Landis SE, Turbow DJ, et al. Effect of a computerized body mass index prompt on diagnosis and treatment of adult obesity. Fam Med 2009;41:502–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang JW, Kushner RF, Cameron KA, et al. Electronic tools to assist with identification and counseling for overweight patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:933–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roth C, Foraker RE, Payne PR, et al. Community-level determinants of obesity: harnessing the power of electronic health records for retrospective data analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2014;14:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fildes A, Charlton J, Rudisill C, et al. Probability of an Obese Person Attaining Normal Body Weight: Cohort Study Using Electronic Health Records. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e54–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guilbert TW, Arndt B, Temte J, et al. The theory and application of UW ehealth-PHINEX, a clinical electronic health record-public health information exchange. WMJ 2012;111:124–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, et al. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA 2014;311:806–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.What is geocoding? ArcGIS Pro. esri®. Accessed June 3, 2016 Available at http://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/help/data/geocoding/what-is-geocoding-.htm.

- 23.Geocoding using ArcGIS & TIGER/LINE shapefiles. United States Census Bureau; Accessed June 2, 2016 Available at https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/education/brochures/Geocoding.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tapestry Segmentation Methodology. esri®. Accessed August 12, 2015 Available at http://www.esri.com/library/whitepapers/pdfs/esri-data-tapestry-segmentation.pdf.

- 25.Nathan RP, Adams C. Understanding Central City Hardship. Political Science Quarterly 1976;91:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nathan RP, Adams CF. Four Perspectives on Urban Hardship. Political Science Quarterly 1989;104:483–508. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin D, Little RJ. Statistical analysis with missing data: Wiley Series in Probability Statistics, 2nd ed. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet 2007;370:851–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vintage 2012 Bridged-Race Postcensal Population Estimates. National Centers for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control; Accessed August 12, 2015 Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/bridged_race/data_documentation.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chhapola V, Kanwal SK, Brar R. Reporting standards for Bland-Altman agreement analysis in laboratory research: a cross-sectional survey of current practice. Ann Clin Biochem 2015;52:382–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 2014;12:1495–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahluwalia N, Dwyer J, Terry A, et al. Update on NHANES Dietary Data: Focus on Collection, Release, Analytical Considerations, and Uses to Inform Public Policy. Adv Nutr 2016;7:121–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.About the National Health Interview Survey. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; Accessed May 30, 2016 Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Early release of selected estimates based on data from the National Health Interview Survey, 2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; Accessed May 29, 2016 Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/releases/released201605.htm#6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Centers for Disease Control; Accessed May 25, 2016 Available at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/. [Google Scholar]

- 36.BRFSS Prevalence & Trends Data. Centers for Disease Control; Accessed May 3, 2016 Available at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Survey of the Health of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health; Accessed May 20, 2016 Available at http://www.med.wisc.edu/show/about-survey-of-the-health-of-wisconsin/36193. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eggers S, Remington PL, Ryan K, et al. Obesity in Wisconsin: Findings from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin. WMJ, in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Report of the NHANES Review Panel to the NCHS Board of Scientific Counselors: Executive Summary. Centers for Disease Control; Accessed 2016, May 30 Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/bsc/nhanesreviewpanelreportrapril09.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowlin SJ, Morrill BD, Nafziger AN, et al. Validity of cardiovascular disease risk factors assessed by telephone survey: the Behavioral Risk Factor Survey. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:561–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.OpenVistA costs one-tenth of Epic — so why don’t more hospitals choose it? Politico. Accessed March 20, 2016 Available at http://www.medsphere.com/resources/news/medsphere-in-the-news/3501-openvista-costs-one-tenth-of-epic-%E2%80%94-so-why-don%E2%80%99t-more.

- 42.Kahwati LC, Lance TX, Jones KR, et al. RE-AIM evaluation of the Veterans Health Administration’s MOVE! Weight Management Program. Transl Behav Med 2011;1:551–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baer HJ, Wee CC, DeVito K, et al. Design of a cluster-randomized trial of electronic health record-based tools to address overweight and obesity in primary care. Clin Trials 2015;12:374–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental digital content. Crude PHINEX rates and NHANES rates compared to weighted PHINEX rates according to BMI class