Abstract

The following fictional case is intended as a learning tool within the Pathology Competencies for Medical Education (PCME), a set of national standards for teaching pathology. These are divided into three basic competencies: Disease Mechanisms and Processes, Organ System Pathology, and Diagnostic Medicine and Therapeutic Pathology. For additional information, and a full list of learning objectives for all three competencies, see http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2374289517715040.1

Keywords: pathology competencies, organ system pathology, central nervous system, brain ischemia, stroke, classification of stroke, stroke treatment

Primary Objective

Objective NSC7.1: Stroke. Compare and contrast the 2 major mechanisms for stroke and how treatment differs for each.

Competency 2: Organ System Pathology; Topic NSC: Nervous System—Central Nervous System; Learning Goal 7: Ischemia of the Brain

Patient Presentation

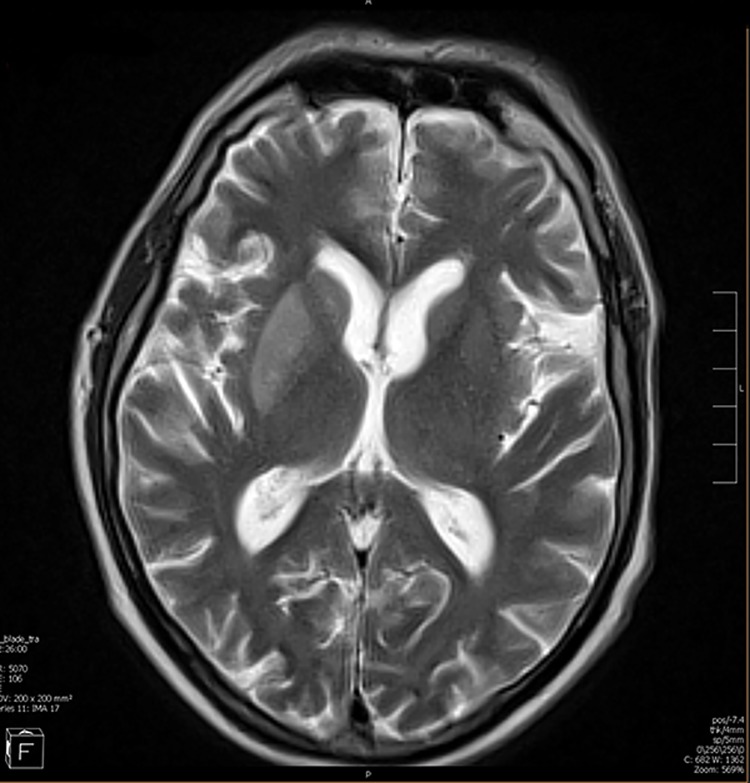

A 63-year-old male presented to the emergency department with a 4-hour history of inability to move his left upper extremity. He received head imaging upon arrival (Figure 1). He reported feeling “fine” prior to the onset of symptoms and had never experienced an episode like this in the past. He was not in pain and did not recall a headache prior to symptom onset. Medical history was significant for a myocardial infarction 6 years ago, hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 2, and hyperlipidemia. Medications included lisinopril, aspirin, metformin, and atorvastatin. However, he stated that he only takes the medications intermittently and last visited a physician 5 years ago. He has also smoked a pack a day for the past 34 years. On physical examination, the patient is alert and oriented times 3, and cranial nerves one through 12 are intact. The left upper extremity exhibits 2 of 5 strength and diminished sensation. Bilateral lower extremities and right upper extremity maintain 5 of 5 strength and intact sensation.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain with no intravenous contrast. In the right lateral portion of the brain an acute thrombotic occlusion of right middle cerebral artery is shown.

Diagnostic Findings

The patient received head imaging shortly upon arrival, as shown in Figure 1.

What Is Seen in the Imaging?

In this patient’s magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head (Figure 1), a bright area can be seen between the anterior and poster portions of the left ventricle that coincides with the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory. When a stroke is suspected, a computed tomography (CT) scan is most commonly the initial imaging test of choice. However, an MRI is often able to identify smaller strokes or the full extent of a larger stroke initially found on CT. In this case, the patient’s neurological left upper extremity deficits are consistent with damage to the left MCA territory of the brain.2

What Is the Most likely Diagnosis in This Patient?

This patient’s sudden onset of monoplegia and extensive history of cardiovascular disease make stroke the most likely diagnosis. However, additional potential diagnoses to consider include brain tumors, seizures, neurological infection, metabolic disorders, and conversion disorder. Imaging such as CTs and MRIs of the head can help identify brain tumors or strokes, electroencephalography can elucidate seizure activity, and laboratory results such as comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood count can identify infection of metabolic disorders. On occasion, psychiatric diagnoses of exclusion such as conversion disorder should be considered.

In this patient’s case, however, the imaging and significant history of cardiovascular disease make stroke the most likely diagnosis. A stroke is a condition of death of the cells in the brain due to lack of oxygen, which results from either an ischemic or hemorrhagic etiology. Ischemia of the brain is due to the blockage of large or small cranial arterioles leading to hypoxia despite adequate systemic blood supply. Hemorrhagic stroke, however, refers to the hypoperfusion of the brain due to a bleed leading to inadequate blood flow to the insulted region.

Questions/Discussion Points

What Causes an Ischemic Stroke?

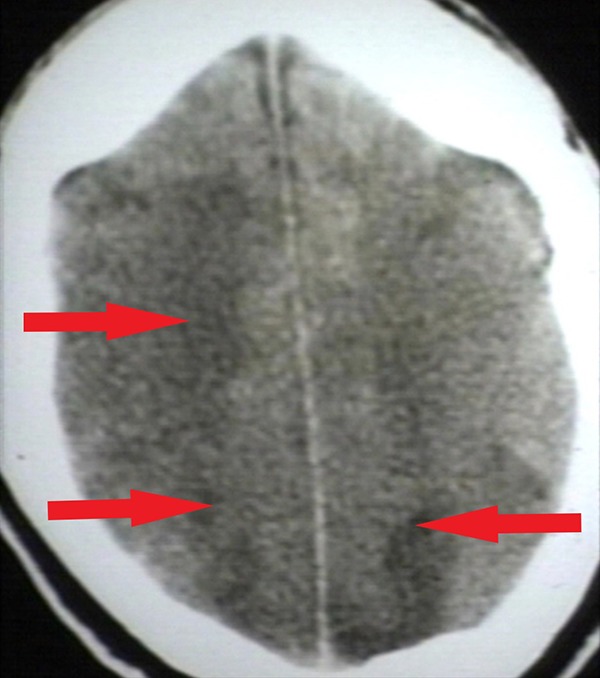

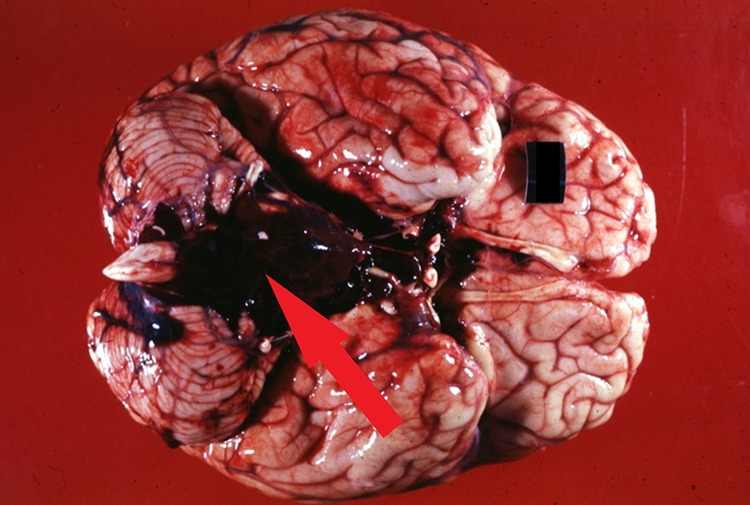

Ischemic strokes are situations in which the arteries to the brain are blocked and prevent blood flow to brain tissue. Ischemic strokes have various etiologies and can affect both large and small vessels in the brain. However, regardless of the etiology, ischemic strokes generally occur in the setting of Virchow triad, which includes turbulence of blood flow, endothelial injury to the vessel (most often arteries), and hypercoagulability (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Brain angiogram showing ischemia of the right middle cerebral artery and temporal lobe area. The hypodense area (arrow) indicates infarcted and dying brain tissue. Reproduced with permission from Dr Peter G Anderson and the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Pathology Education Information Resource (PEIR) Digital Library.

Figure 3.

Gross brain specimen of large ischemic infarct in distribution of the middle cerebral artery. The dark and mottled areas (arrow) on the specimen indicate infarcted and dying brain tissue. Reproduced with permission from Dr Peter G Anderson and the UAB Pathology Education Information Resource (PEIR) Digital Library.

How Can Ischemic Strokes Be Subdivided?

Ischemic strokes can be subdivided into large and small vessel ischemic strokes. Large vessel ischemic strokes can further be subdivided into thrombotic strokes, embolic strokes, and systemic hypoperfusion strokes.

What Are Thrombotic Strokes?

Thrombotic strokes result from a localized vulnerable or unstable atherosclerotic plaque located in a cranial artery that increases in size and eventually ruptures. Once the cap of the plaque is torn away, the plaque fully ruptures and releases various inflammatory mediators such as macrophages and tissue factor that then initiate thrombus formation. These mediators attract and assemble smooth muscle cells and platelets to stabilize the clot. Repeated plaque ruptures and stabilizations result in narrowing, or stenosis, of the vessel, which increasing the future risk of ischemic stroke.3

What Are Embolic Strokes?

Embolic strokes are a result of a thrombus that is located outside of the brain that breaks and a piece known as an embolus travels to the cranial vasculature and leads to a blockage. These can commonly result from thrombus formation in the heart that is then destabilized by atrial fibrillation.

What Are Hypoperfusion Strokes?

Systemic hypoperfusion strokes result from massive hemorrhage or cardiac pump failure that cause systemic hypotension and therefore, hypoperfusion of the cranial vasculature leading to global brain ischemia (Figures 4 and 5). Watershed zones of the brain are most affected. These watershed zones are areas of the brain that are not directly supplied by major vasculature. They are instead supplied by the branch/connection points of 2 major arteries. Therefore, when blood pressure is low due to systemic hypoperfusion, blood is not able to adequately supply these areas with oxygenation. There are 2 main types of watershed strokes: cortical watershed strokes (anterior cerebral artery-MCA territory and posterior cerebral artery-MCA territory) and internal watershed strokes (lenticulostriate artery territory-MCA territory).4 Other areas of the brain particularly sensitive to global hypoxic-ischemic injury include the Purkinje neurons of the cerebellar cortex, and neurons of hippocampal areas.5

Figure 4.

Graphic representation overlaid on a gross brain specimen showing watershed territory between the middle and anterior cerebral arteries. Middle cerebral artery territory is in red. Anterior cerebral artery is in white. The light pink intersection between the 2 territories is the watershed area. Reproduced with permission from Dr. Peter G Anderson and the UAB Pathology Education Information Resource (PEIR) Digital Library.

Figure 5.

Head CT of major watershed infarction following a man’s hanging. Hypodense areas (arrows) indicate diffuse hypoperfusion and infarction of brain tissue. Reproduced with permission from Dr. Peter G Anderson and the UAB Pathology Education Information Resource (PEIR) Digital Library. CT indicates computed tomography.

What Are the Etiologies of Large Vessel Ischemia?

Large vessel ischemic strokes refer to massive insults to the main branches of the cranial vasculature such as the anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries. Because each branch supplies large portions of the brain, patients can experience dramatic neurological symptoms such as the monoplegia of the left upper extremity seen in the above case. While localized thrombus formation can occur in one of these main branches, sudden onset symptoms can indicate an embolus from another location of the body. For example, insults to cardiac myocytes, such as acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and cardiac aneurysms or abnormal electrical conduction such as arrhythmias lead to pooling and stasis of blood flow in the heart, creating a clot. The heart’s natural beating creates stress on the coagulated clot, eventually causing a piece, or embolus, to break away and continue traveling through the vascular system unimpeded. Because these clots often form in the left atrium or left ventricle, the embolus then travels through the aorta where it can then travel through the left common carotid artery and into the brain vasculature causing a blockage of blood flow. The same can occur with various cardiac tumors, such as myxomas, papillary fibroelastoma, rhabdomyomas, and fibromas as well as infective endocarditis.6,7 A fragment of a tumor or infection can also embolize and cause the same neurological deficits as a blood embolus. Cardiac malformations like a patent foramen ovale can lead to a phenomenon called a paradoxical embolism in which an embolism from the venous system, such as a deep vein thrombosis, can travel directly to the arterial system and lead to an ischemic stroke as well.8

What Are the Etiologies of Small Vessel Ischemia?

Small vessel ischemia refers to insults of the intracerebral arterial system that supplies the deeper structures of the brain such as the basal ganglia, internal capsule, thalamus, and pons. These cerebrovascular events are also known as lacunar strokes and are believed to result from either lipohyalinosis or atheroma formation. Lipohyalinosis, which is thought to be secondary to chronic hypertension, is a process in which hypertrophy of the tunica media and a lipid-fibrin material blocks the arterial lumen. Atheromas can also form at the small vessel origin or parent artery and cause blockage. A rarer cause of lacunar stroke is genetic small vessel disease such as cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) or cerebral autosomal recessive arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. The former stems from a mutation in the Notch 3 gene, while the latter from a mutation in HTRA1;9 in both, the affected small vessels undergo pathologic wall thickening, with CADASIL demonstrating intramural granular, periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-positive material.10 There are 5 classic syndromes associated with lacunar stroke that lack classic “cortical” findings such as aphasia, agnosia, neglect, apraxia, monoplegia, coma, or loss of consciousness.11

What Is the Treatment of an Ischemic Stroke?

When a patient presents with signs and symptoms of stroke, initial workup includes history of present illness, medical history, current medications, and CT head without contrast to differentiate an ischemic versus hemorrhagic stroke. Computed Tomography head without contrast will allow gross blood to appear bright white on the scan, allowing for ease of identification of an acute hemorrhagic stroke. Once an acute bleed has been ruled out, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is given intravenously to restore blood flow to the infarcted tissue and minimize permanent damage. Current guidelines state that tPA can only be given within a window of 3 to 4.5 hours after symptom onset.12 Other considerations during the acute ischemic stroke period are glucose levels and blood pressure. Hypoglycemia can mimic stroke symptoms and, therefore, should be quickly corrected if identified, while hyperglycemia can worsen outcomes secondary to tissue acidosis, free radical generation, and increased blood brain permeability.13 Blood pressure should also be managed to below 185 mm Hg systolic and below 110 mm Hg diastolic prior to thrombolytic therapy.14 Following acute stabilization, patients suffering from an ischemic stroke must be started on several therapies to reduce adverse sequelae including antithrombotic therapy with aspirin, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin, a secondary antithrombotic therapy such as clopidogrel, high-intensity statin therapy, blood pressure therapy, and lifestyle modifications, such as smoking cessation, weight loss, and diet improvement.13 Because the cause of the ischemic stroke could have been embolic, further workup such as a carotid Doppler and echocardiogram may be indicated to elucidate the origin of the embolus and prevent future strokes.

What Are the Causes of Hemorrhagic Stroke?

The second major category of stroke is hemorrhagic stroke. This can be further subdivided into intracranial hemorrhage, in which the bleeding occurs directly into the brain, or subarachnoid hemorrhage, in which the bleeding occurs between the brain and the meningeal coverings. Intracranial hemorrhage can be caused by hypertension and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), which is an important risk factor in the elderly individual. Intracranial hemorrhage in the setting of hypertension can be associated with the bursting of Charcot-Bouchard aneurysms, small outpouchings found in the lenticulostriate vessels of the basal ganglia leading to deficits associated with damage to deep brain structures. The intracranial hemorrhage leads to not only hypoperfusion of the area but also a mass effect due to the growing hematoma, causing direct mechanical injury as well. These bleeds can be difficult to differentiate from an ischemic stroke clinically, but they can present with nausea, vomiting, and seizures. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy represents a vasculopathy in which pathologic forms of a-β peptide deposit into the walls of cerebrovasculature in the form of a-β amyloid. While hypertensive bleeds most often involve the vasculature of deep cerebral structures, hemorrhages associated with CAA tend to originate from superficial cerebral cortical and leptomeningeal vasculature, producing a distinctive pattern of superficial lobar hemorrhage. While CAA may arise on its own in elderly patients, it may often be seen in conjunction with Alzheimer disease neuropathological change.15

A subarachnoid hemorrhage can occur secondary to berry aneurysms and vascular malformations which can bleed very quickly (Figures 6 and 7). The rapid bleeding then spreads into the CSF and quickly increases intracranial pressure. Patients with a subarachnoid hemorrhage do not necessarily present with focal neurological deficits, but instead have alarming symptoms such as the classic “thunderclap” headache or “worst headache of my life” and can quickly progress to coma or death.13

Figure 6.

Gross brain specimen of subarachnoid bleed (arrow) likely secondary to a berry aneurysm in the anterior communicating artery. Reproduced with permission from Dr. Peter G Anderson and the UAB Pathology Education Information Resource (PEIR) Digital Library.

Figure 7.

Computed tomography head subarachnoid bleed. The hyperdense bright white area (arrow) is the acute bleed filling up the normally black subarachnoid cisterns and sulci. Reproduced with permission from Dr Peter G Anderson and the UAB Pathology Education Information Resource (PEIR) Digital Library.

What Is the Treatment for Hemorrhagic Strokes?

Because hemorrhagic strokes can present similarly to ischemic strokes, the initial workup includes history of present illness, medical history, current medications, and CT head without contrast. In the case of a hemorrhagic bleed, the CT will show a hyperdensity representing the acute bleed (Figures 8 and 9). These patients have a strong contraindication against tPA, which would worsen the bleeding risk. Additionally, it is unclear if reducing blood pressure improves outcomes in the setting of hemorrhagic stroke since decreasing blood pressure may lead to increased hypoperfusion to the surrounding parenchyma. Current guidelines only suggest aggressive BP management of systolic is above 200 mm Hg or the diastolic is above 150 mm Hg.16 The medical team may then suggest surgical intervention such as clipping or endovascular coiling to prevent rebleeding from an aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation removal.13

Figure 8.

Gross brain specimen of intracranial hemorrhagic stroke. Reproduced with permission from Dr. Peter G Anderson and the UAB Pathology Education Information Resource (PEIR) Digital Library.

Figure 9.

Computed tomography head showing bright white area (arrow) representative of an acute bleed in the setting of an intracranial hemorrhagic stroke in the putamenal area. Reproduced with permission from Dr Peter G Anderson and the UAB Pathology Education Information Resource (PEIR) Digital Library.

Teaching Points

Ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes can be differentiated by CT head without contrast. Bright white blood on CT scan without contrast indicates acute bleeding secondary to hemorrhage and acts as a contraindication to tPA therapy.

In addition to hypoperfusion damage, hemorrhagic strokes can cause mechanical injury due to the mass effect of the growing hematoma.

Watershed zones, which are supplied by branch/connection points of 2 major arteries, are important sections of the brain that are highly susceptible to infarcts secondary to hypoperfusion.

Ischemic strokes can be caused by thrombosis, embolus, or hypoperfusion.

Hemorrhagic stroke can be subdivided into intracranial and subarachnoid bleeds.

Treatment for ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes are vastly different, especially in terms of anticoagulation and blood pressure management guidelines.

Presenting symptoms can vary depending on type and location of stroke. Both ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke can result in neurological deficits, but hemorrhagic stroke may show nausea, vomiting, and seizures secondary to mass effect.

The presentation of a “thunderclap” headache can indicate need for emergency surgical intervention for a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The article processing fee for this article was funded by an Open Access Award given by the Society of ‘67, which supports the mission of the Association of Pathology Chairs to produce the next generation of outstanding investigators and educational scholars in the field of pathology. This award helps to promote the publication of high-quality original scholarship in Academic Pathology by authors at an early stage of academic development.

ORCID iD: Stacy G. Beal  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0862-4240

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0862-4240

References

- 1. Knollmann-Ritschel BEC, Regula DP, Borowitz MJ, Conran R, Prystowsky MB. Pathology competencies for medical education and educational cases. Acad Pathol. 2017;4 doi:10.1177/2374289517715040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Birenbaum D, Bancroft LW, Felsberg GJ. Imaging in acute stroke. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:67–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Furie B, Furie BC. Mechanisms of thrombus formation. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:938–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mangla R, Kolar B, Almast J, Ekholm SE. Border zone infarcts: pathophysiologic and imaging characteristics. RadioGraphics. 2011;31:1201–1214. doi:10.1148/rg.315105014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Busl KM, Greer DM. Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury: pathophysiology, neuropathology and mechanisms. NeuroRehabilitation. 2010;26:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kitts D, Bongard FS, Klein SR. Septic embolism complicating infective endocarditis. J Vasc Surg. 1991;14:480–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rao A. Cardiac Tumors. Kenilworth, NJ: Merck Manuals; 2018. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/cardiovascular-disorders/cardiac-tumors/cardiac-tumors. Accessed May 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Windecker S, Stortecky S, Meier B. Paradoxical embolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:403–415. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ruchoux M, Maurage C. CADASIL: cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:947–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ito S, Takao M, Fukutake T, et al. Histopathologic analysis of Cerebral Autosomal Recessive Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy (CARASIL): a report of a new genetically confirmed case and comparison to 2 previous cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2016;75:1020–1030. doi:10.1093/jnen/nlw078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shi Y, Wardlaw JM. Update on cerebral small vessel disease: a dynamic whole-brain disease. BMJ. 2016;1:83–92. doi:10.1136/svn-2016-000035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hughs R, Tadi P, Bollu P. TPA Therapy. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482376/#_NBK482376_pubdet_. Accessed May 18, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Filho J, Mullen M. Initial assessment and management of acute stroke. 2019. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/initial-assessment-and-management-of-acute-stroke#H100191313. Accessed May 20, 2019.

- 14. Powers W, Rabinstein A, Ackerson T, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46–e110. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brenowitz WD, Nelson PT, Besser LM, Heller KB, Kukull WA. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and its co-occurrence with Alzheimer’s disease and other cerebrovascular neuropathologic changes. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:2702–2708. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Caceres JA, Goldstein JN. Intracranial hemorrhage. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2012;30:771–794. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]