Abstract

Background:

Arthroscopic meniscal surgery is a common orthopaedic procedure in middle-aged patients, but the efficacy of this procedure has been questioned. In this study, we followed up the only randomized controlled trial that has shown a 1-year benefit from knee arthroscopic surgery with an exercise program compared with an exercise program alone.

Purpose:

To (1) evaluate whether knee arthroscopic surgery combined with an exercise program provided an additional 5-year benefit compared with an exercise program alone in middle-aged patients with meniscal symptoms, (2) determine whether baseline mechanical symptoms affected the outcome, and (3) compare radiographic changes between treatment groups.

Study Design:

Randomized controlled trial; Level of evidence, 1.

Methods:

Of 179 eligible patients aged 45 to 64 years, 150 were randomized to either a 3-month exercise program (nonsurgery group) or to the same exercise program plus knee arthroscopic surgery (surgery group) within 4 weeks. Radiographs were assessed, according to the Kellgren-Lawrence grade, at baseline and at the 5-year follow-up. The primary outcome was the change in Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)–Pain (KOOSPAIN) subscore from baseline to the 5-year follow-up. We performed an as-treated analysis.

Results:

A total of 102 patients completed the 5-year questionnaire. At the 5-year follow-up, both groups had significant improvement in KOOSPAIN subscores, although there was no significant change from the 3-year scores. There was no between-group difference in the change in the KOOSPAIN subscore from baseline to 5 years (3.2 points [95% CI, –6.1 to 12.4]; adjusted P = .403). In the surgery group, improvement was greater in patients without mechanical symptoms than in those with mechanical symptoms (mean difference, 18.4 points [95% CI, 8.7 to 28.1]; P < .001). Radiographic deterioration occurred in 60% of patients in the surgery group and 37% of those in the nonsurgery group (P = .060).

Conclusion:

Knee arthroscopic surgery combined with an exercise program provided no additional long-term benefit after 5 years compared with the exercise program alone in middle-aged patients with meniscal symptoms. Surgical outcomes were better in patients without mechanical symptoms than in patients with mechanical symptoms during the preoperative period. Radiographic changes did not differ between treatment groups.

Registration:

NCT01288768 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier).

Keywords: knee arthroscopic surgery, menisci, meniscectomy, middle-aged, radiographic osteoarthritis

Arthroscopic surgery is a common orthopaedic procedure in middle-aged patients with knee symptoms.9,50 However, even in the absence of knee symptoms, in the general population and within this age group, incidental findings of meniscal lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are very common.12 It was suggested that a meniscal injury in middle-aged patients should be considered an indicator of incipient knee osteoarthritis (OA).13 Consequently, the patient’s symptoms might not be caused by a degenerative meniscus alone but might arise from multiple factors attributable to early OA.3 Previously, several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have reported that arthroscopic meniscal surgery provided little or no additional benefit over nonsurgical treatment18,19,22,26,27,53,55 or sham surgery.35,41,47,48 Therefore, the issue of how to treat degenerative meniscal injuries has been recently and extensively debated.7,8,31,38 Systematic reviews have concluded that arthroscopic surgery showed a small benefit of pain relief that lasted for up to 6 months but not 2 years after surgery in middle-aged or older patients with knee pain and degenerative knee disease.5,52,54 Nevertheless, the role of arthroscopic surgery in the treatment of degenerative meniscal tears remains controversial.2,30,33 A recent review concluded that these patients could benefit from arthroscopic meniscectomy but that nonsurgical treatment should be considered first.29 Mechanical symptoms were previously considered an indication for surgery; however, recent data have contradicted this tenet.14,46

The follow-up times of most RCTs on this topic have been limited to a maximum of 2 years,26,27,35,47,53,55 except in 2 studies that reported a 5-year follow-up.19,24 Moreover, most RCTs have evaluated only patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), and only 2 previous RCTs have reported radiographic findings.19,55 Because removing functional meniscal tissue could increase the risk of knee OA,13 additional data are needed regarding the long-term effects, including radiographic changes, of arthroscopic meniscectomy compared with nonoperative treatment.

The present study was the only RCT with comprehensive recruitment from a catchment area, which provided adequate representation of the population33 and demonstrated a statistically and clinically significant positive effect of knee arthroscopic surgery with an exercise program after 1 year compared with an exercise program alone.15 The objectives of the present study were to (1) evaluate whether knee arthroscopic surgery combined with an exercise program provided an additional 5-year benefit compared with an exercise program alone in middle-aged patients with meniscal symptoms, (2) determine whether baseline mechanical symptoms affected the outcome, and (3) compare radiographic changes between treatment groups. We hypothesized that there would be no differences between treatment groups.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Participants were recruited from the orthopaedic department at Linköping University Hospital between 2010 and 2012. For this study, eligibility was determined by 1 orthopaedic surgeon (H.G.), who evaluated all patients referred with a suspected meniscal injury. Inclusion criteria were the following: age 45 to 64 years, symptoms for longer than 3 months, standing radiograph with an Ahlbäck grade of 0 (<50% reduction of the joint space, without consideration of possible osteophytes),1 and prior treatment with physical therapy. Inclusion was based on meniscal symptoms from a medical history and clinical examinations, and MRI was not performed. We believe that MRI is not indicated in the management of this patient population and that treatment should focus on improving symptoms and function. All consecutive patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and did not meet any exclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study (Figure 1). Details about recruitment were published previously.15

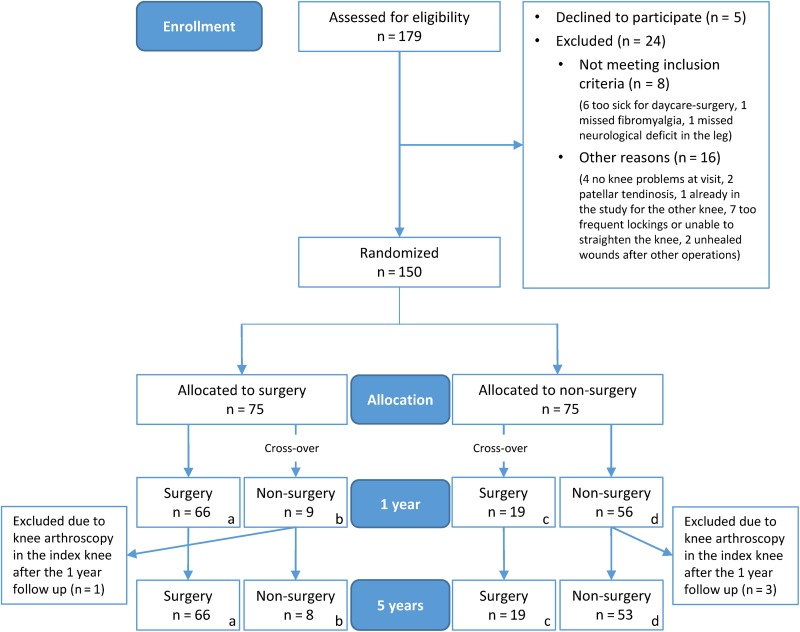

Figure 1.

Patient enrollment and randomization. Exclusion criteria were locked knee or joint locking for more than 2 seconds more often than once a week, rheumatic or neurological disease, fibromyalgia, replacement of hip or knee joints, or a contraindication for surgery (body mass index >35 kg/m2 or a serious medical illness). Groups analyzed in the as-treated analysis: surgery group = a + c (total of 85 patients) and nonsurgery group = b + d (total of 61 patients).

The patients were randomly allocated to 1 of 2 parallel intervention groups. One group (nonsurgery) received a physical therapy session within 2 weeks, with a functional assessment and instructions for an exercise program. The other group (surgery) received the same physical therapy treatment within 2 weeks plus knee arthroscopic surgery within 4 weeks of inclusion. Any significant meniscal injuries were resected during the arthroscopic procedure. Group allocations were placed in sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes in 15 blocks with a block size of 10. After enrollment, the patient and a nurse opened the envelope. The orthopaedic surgeon who enrolled and assessed patients was blinded to the allocation sequence.

The 5-year follow-up data were analyzed with an as-treated approach. Patients who underwent arthroscopic surgery on the index knee between allocation and the 1-year follow-up were included in the surgery group. Patients who did not undergo arthroscopic surgery on the index knee between allocation and the 5-year follow-up were included in the nonsurgery group. Patients were excluded if they underwent arthroscopic surgery on the index knee after the 1-year follow-up (Figure 1).

Interventions

The exercise program aimed to increase muscle function and postural control. This program lasted for 3 months. The physical therapy sessions were held at an independent physical therapy clinic. Surgery was performed by 1 of 2 experienced arthroscopic surgeons at an independent day surgery clinic. During surgery, patients received general or local anesthetics. Based on their own experience, the surgeons judged whether meniscal resection was indicated. All patients were allowed to perform full weightbearing activities immediately after surgery. Patients were advised to resume the exercise program after surgery. Detailed information about the interventions was previously published.15

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

Before randomization (baseline), the orthopaedic surgeon assessed the symptom history regarding the presence of mechanical symptoms, defined as daily joint catching and/or joint locking for more than 2 seconds over the past month. Then, the patient was isolated to complete the PROM forms, including the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), the EuroQol 5 dimensions (EQ-5D), and the Physical Activity Scale (PAS). Patients completed the same questionnaires at 3 months, 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years after baseline. There were no planned follow-up visits for the patients at the orthopaedic clinic. Patients completed all follow-up questionnaires at home and returned the forms in an envelope with prepaid postage. The primary outcome was the change in the KOOS-Pain (KOOSPAIN) subscore between baseline and the 5-year follow-up. In addition, the change in the KOOSPAIN subscore at 5 years was divided into 3 categories compared with baseline: improved (>10-point higher score), stable (within 10 points), and deteriorated (>10-point lower score). These categories were analyzed to evaluate clinically relevant changes. Detailed information about the outcomes was previously published.15

Radiographic Assessment

Weightbearing radiographs were obtained at baseline and the 5-year follow-up. One radiologist (J.Y.), who was blinded to the allocation and treatment, assessed all radiographs according to the Kellgren-Lawrence grade.25 The grades were as follows: grade 0, no radiographic features of OA present; grade 1, possible osteophytes only; grade 2, definite osteophytes and possible joint space narrowing; grade 3, moderate osteophytes and/or definite narrowing; and grade 4, large osteophytes, severe joint space narrowing, and/or bony sclerosis. Radiographic OA was defined as grade ≥2.44 Deteriorations in radiographic findings were also evaluated according to the Kellgren-Lawrence grade.

Adverse Events

Adverse events were identified with the 5-year questionnaire and a review of the electronic medical records after 3 years. There were no reports of deep venous thrombosis, infections, or other complications during the first 3 years postoperatively. There were 2 revision arthroscopic procedures of the medial meniscus in the surgery group; 1 revision resection was performed at 10 months, and the other was performed at 21 months after inclusion.

Response and Dropout Analysis

We analyzed the patient characteristics and baseline data of the group of patients who responded to the questionnaire (n = 102) compared with those who did not respond (n = 44) at 5 years. A dropout analysis was performed by contacting patients who did not answer the questionnaire at 5 years but did not decline further study participation (n = 28). These patients were asked to participate in a short telephone interview. A physical therapist performed the interview. This interview included questions from the 5-year questionnaire, questions from the PAS, and 3 EQ-5D questions regarding pain (rated on a 3-point scale; eg, no pain, moderate pain, severe pain), knee function (rated on a 10-point scale), and the ability/inability to perform daily activities (eg, limitations/no limitations in daily activities).

Statistical Analysis

We used an as-treated approach in the analyses. Analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 23.0; IBM), and all analyses were 2-sided, with the significance level set at P < .05. Independent-samples t tests were used to analyze cross-sectional between-group differences in PROM scores. Changes in PROM scores at both the 1- and 5-year follow-ups were analyzed with independent-samples t tests and analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs); the respective PROM score at baseline was used as a covariate to generate adjusted P values. In addition, the changes in PROM scores at the 5-year follow-up were analyzed with 2-way ANCOVAs, with the treatment group and mechanical symptoms as factors and the baseline PROM score as the covariate. Group differences in categorical data were analyzed with the Pearson chi-square test or Fisher exact test.

A minimal change of 8 to 10 points was considered clinically important for the KOOSPAIN. Thus, a 10-point change was used as the cutoff to indicate recovery.42 To detect a between-group difference of 10 points (SD, 19) on the KOOSPAIN (α = 0.05; β = 0.8), we included 75 participants in each group; this accounted for a crossover and dropout rate of 33%.

Results

Study Participants

Patients were randomly assigned to either the surgery (n = 75) or nonsurgery (n = 75) group. Moreover, 19 patients (25%) crossed over from the nonsurgery group to undergo surgery. There were 8 patients (11%) allocated to the surgery group who did not go through with the operative procedure. Of the 75 patients who initially were randomized to surgery, 66 underwent surgery (56 underwent partial meniscal resection, 2 underwent removal of degenerated joint cartilage fragments, 1 underwent resection of loose bodies, 1 underwent synovectomy, 1 underwent partial resection of anterior cruciate ligament remnants, and 8 were judged as not needing surgical treatment). Of the 75 patients who initially were randomized to nonsurgical treatment, 19 crossed over and underwent surgery (12 underwent partial meniscal resection, 1 underwent resection of loose bodies, 1 underwent microfracture, 1 underwent partial resection of anterior cruciate ligament remnants, 1 was judged not to need surgical treatment, and there was missing information for 3 patients). A total of 4 patients were excluded from the 5-year follow-up because they underwent arthroscopic surgery in the index knee after the 1-year follow-up. Consequently, 146 patients were available for the as-treated analysis (Figure 1). There was 1 patient in the surgery group who underwent arthroscopic surgery in March 2011 and died in 2014. The 1-year questionnaire was completed by 130 patients (89%), and the 3-year questionnaire was completed by 119 patients (82%). The results from the 1-15 and 3-year14 follow-ups were published previously. The 5-year questionnaire was completed by 102 patients (70%; 66 patients in the surgery group and 36 patients in the nonsurgery group). Weightbearing radiographs were obtained at the 5-year follow-up for 82 patients (56%; 55 patients in the surgery group and 27 patients in the nonsurgery group).

Patient Characteristics and Baseline Data

Patient characteristics, including OA severity, and baseline data are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The groups were not significantly different in patient characteristics at baseline (Table 1). However, at baseline, the PROMs showed that the surgery group scored lower than the nonsurgery group on the KOOSPAIN (mean difference, –6.8 [95% CI, –12.5 to 1.1]; P = .020), KOOS–Activities of Daily Living (KOOSADL) (mean difference, –6.9 [95% CI, –13.1 to –0.7]; P = .029), KOOS–Sports (KOOSSPORTS) (mean difference, –10.5 [95% CI, –17.8 to –3.2]; P = .008), and KOOS–Quality of Life (KOOSQoL) (mean difference, –5.7 [95% CI, –11.0 to –0.4]; P = .036) (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics at Baselinea

| Surgery (n = 85) | Nonsurgery (n = 61) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 55 ± 5 | 54 ± 6 | .443b |

| Sex, male/female, n | 43/42 | 39/22 | .109c |

| Duration of knee pain, median (IQR), mo | 7 (8) | 7 (8) | .839d |

| OA severity (Kellgren-Lawrence grade) | .369e | ||

| 0 | 30 (38) | 15 (25) | |

| 1 | 18 (23) | 19 (32) | |

| 2 | 31 (39) | 25 (42) | |

| 3 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | |

| Sudden onset of pain | 47 (56) | 32 (55) | .927c |

| Mechanical symptoms | 58 (69) | 32 (54) | .071c |

| Age <55 y | 42 (49) | 32 (53) | .716c |

| Moderate to high physical activity level (PAS 4-6) | 27 (33) | 19 (33) | .960c |

aValues are shown as n (%) unless otherwise indicated. IQR, interquartile range; OA, osteoarthritis; PAS, Physical Activity Scale.

bIndependent-samples t test.

cPearson chi-square test.

dMann-Whitney U test.

eFisher exact test.

TABLE 2.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Scoresa

| Baseline | 1 y | 3 y | 5 y | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Nonsurgery | P Value | Surgery | Nonsurgery | P Value | Surgery | Nonsurgery | P Value | Surgery | Nonsurgery | P Value | |

| KOOSPAIN | ||||||||||||

| n | 84 | 60 | 78 | 48 | 70 | 44 | 65 | 35 | ||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 53.5 (50.0 to 56.9) |

60.2 (55.4 to 65.1) |

.020 | 84.3 (80.8 to 87.8) |

79.1 (74.1 to 84.1) |

.085 | 82.4 (77.8 to 87.0) |

80.1 (73.5 to 86.7) |

.557 | 79.3 (74.2 to 84.4) |

86.0 (79.7 to 92.2) |

.111 |

| KOOSSYMPTOMS | ||||||||||||

| n | 83 | 60 | 78 | 48 | 71 | 44 | 66 | 36 | ||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 58.5 (54.9 to 62.0) |

62.7 (57.6 to 67.9) |

.176 | 82.1 (78.7 to 85.5) |

78.9 (73.7 to 84.0) |

.274 | 82.5 (78.2 to 86.8) |

78.5 (72.5 to 84.4) |

.269 | 77.1 (72.1 to 82.1) |

85.6 (80.0 to 91.3) |

.034 |

| KOOSADL | ||||||||||||

| n | 83 | 59 | 78 | 48 | 71 | 42 | 64 | 36 | ||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 63.2 (59.3 to 67.2) |

70.2 (65.3 to 75.1) |

.029 | 86.9 (83.3 to 90.6) |

82.9 (77.9 to 87.9) |

.188 | 86.5 (82.3 to 92.2) |

81.9 (75.5 to 88.2) |

.203 | 83.9 (79.3 to 88.5) |

87.9 (82.3 to 93.4) |

.283 |

| KOOSSPORTS | ||||||||||||

| n | 83 | 59 | 78 | 48 | 71 | 44 | 65 | 35 | ||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 26.4 (22.4 to 30.5) |

36.9 (30.3 to 43.6) |

.008 | 57.2 (51.2 to 63.3) |

58.9 (51.0 to 66.7) |

.744 | 61.5 (54.3 to 68.6) |

61.9 (52.7 to 71.1) |

.948 | 57.7 (50.5 to 64.9) |

65.9 (55.6 to 76.2) |

.186 |

| KOOSQoL | ||||||||||||

| n | 84 | 59 | 78 | 48 | 71 | 44 | 65 | 36 | ||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 31.8 (28.6 to 35.0) |

37.5 (33.0 to 42.0) |

.036 | 64.3 (59.2 to 69.4) |

60.4 (53.7 to 67.1) |

.348 | 69.6 (63.8 to 75.5) |

66.8 (59.2 to 74.4) |

.547 | 65.3 (59.4 to 71.2) |

68.1 (59.4 to 76.7) |

.585 |

| EQ-5D | ||||||||||||

| n | 83 | 59 | 78 | 48 | 68 | 41 | 65 | 36 | ||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 0.61 (0.55 to 0.66) |

0.65 (0.59 to 0.71) |

.264 | 0.83 (0.78 to 0.87) |

0.83 (0.79 to 0.87) |

.873 | 0.86 (0.82 to 0.90) |

0.80 (0.73 to 0.87) |

.134 | 0.81 (0.76 to 0.86) |

0.86 (0.81 to 0.91) |

.181 |

| EQ-VAS | ||||||||||||

| n | 82 | 58 | 77 | 47 | 68 | 42 | 64 | 34 | ||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 60.9 (56.5 to 65.2) |

65.9 (60.2 to 71.5) |

.157 | 77.2 (73.2 to 81.3) |

76.1 (71.7 to 80.5) |

.716 | 78.7 (74.2 to 83.2) |

76.9 (71.6 to 82.2) |

.623 | 79.0 (75.1 to 83.0) |

83.5 (79.0 to 88.0) |

.160 |

aData are based on the total cohort of patients at each evaluation time point. Bolded values indicate statistical significance (P < .05). ADL, activities of daily living; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5 dimensions; EQ-VAS, EuroQol visual analog scale; KOOS, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; QoL, quality of life.

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

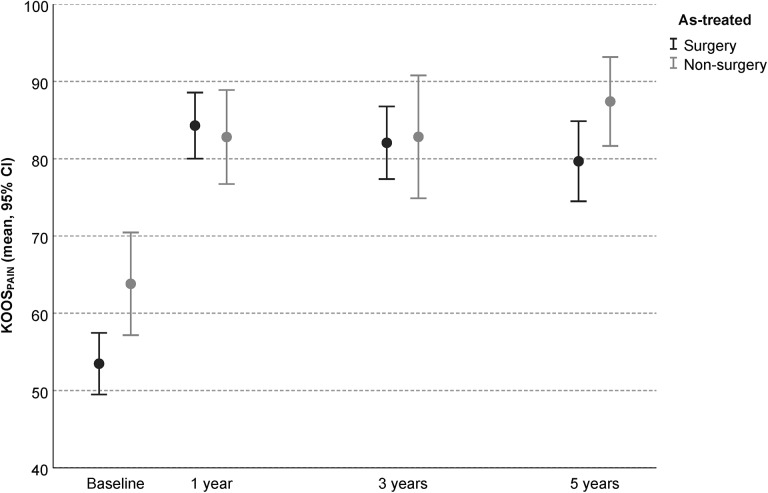

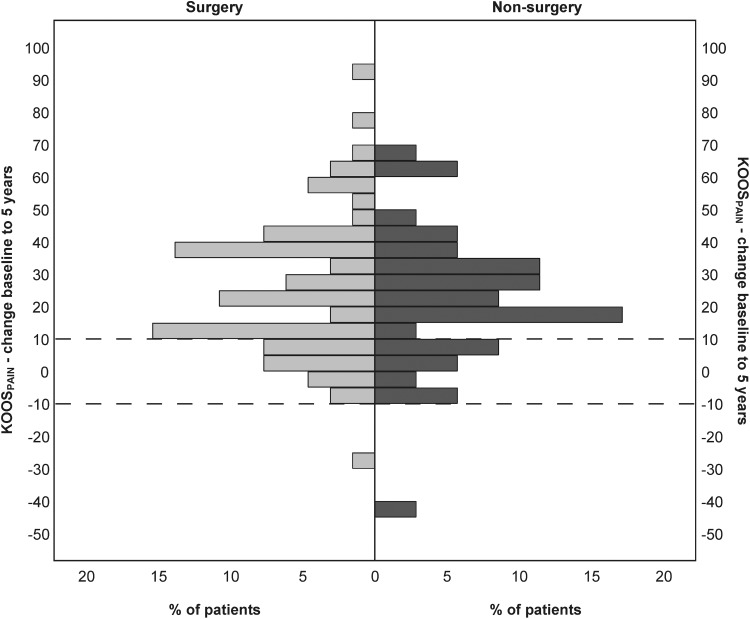

The groups showed no difference in the change in the KOOSPAIN subscore from baseline to 5 years in either the unadjusted or adjusted analysis (P = .500 and P = .403, respectively) (Table 3 and Figure 2). The surgery group improved more than the nonsurgery group on the KOOSPAIN from baseline to 1 year according to the unadjusted analysis (difference in mean change, 11.8 [95% CI, 3.6 to 19.9]; P = .005), but this difference was no longer significant in the adjusted model when the baseline KOOSPAIN subscore was considered a covariate (adjusted P = .194). There was a difference between groups in the change in the KOOSPAIN subscore from 3 to 5 years in favor of the nonsurgery group (difference in mean change, 5.8 [95% CI, –0.2 to 11.7]; P = .058; adjusted P = .038) (Table 3). Greater than a 10-point improvement on the KOOSPAIN at 5 years was observed in 75% (n = 49) of patients in the surgery group compared with 74% (n = 26) of patients in the nonsurgery group. Only 1 patient in each group (2% in the surgery group and 3% in the nonsurgery group) reported a deterioration of more than 10 points on the KOOSPAIN at 5 years (P > .999) (Figure 3).

TABLE 3.

Change in Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Scoresa

| Baseline to 1 yb | Baseline to 5 y | 3 to 5 y | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Nonsurgery | Between- Group Difference |

Adjusted P Valuec |

Surgery | Nonsurgery | Between- Group Difference | Adjusted P Valuec | Surgery | Nonsurgery | Between- Group Difference | Adjusted P Valued | |

| KOOSPAIN | ||||||||||||

| n | 62 | 33 | 65 | 35 | 61 | 31 | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 31.1 (26.4 to 35.8) |

19.4 (12.3 to 26.5) |

11.8 (3.6 to 19.9) |

.194 | 25.8 (20.2 to 31.3) |

22.6 (15.1 to 30.2) |

3.2 (–6.1 to 12.4) |

.403 | –1.2 (–4.5 to 2.2) |

4.6 (–0.8 to 10.0) |

5.8 (–0.2 to 11.7) |

.038 |

| P value | .005 | .500 | .058 | |||||||||

| KOOSSYMPTOMS | ||||||||||||

| n | 61 | 33 | 65 | 36 | 63 | 32 | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 25.0 (21.2 to 28.8) |

18.3 (11.8 to 24.7) |

6.7 (–0.2 to 13.6) |

.321 | 17.9 (12.9 to 22.9) |

19.9 (13.2 to 26.7) |

2.0 (–6.2 to 10.3) |

.124 | –4.0 (–7.7 to –0.3) |

3.9 (–0.8 to 8.6) |

7.9 (1.8 to 14.1) |

.008 |

| P value | .057 | .625 | .011 | |||||||||

| KOOSADL | ||||||||||||

| n | 62 | 32 | 64 | 35 | 61 | 31 | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 23.7 (19.2 to 28.2) |

12.7 (7.0 to 18.5) |

11.0 (3.5 to 18.4) |

.116 | 20.4 (15.4 to 25.4) |

14.0 (7.0 to 20.9) |

6.4 (–2.0 to 14.9) |

.975 | –1.0 (–4.6 to 2.6) |

3.9 (–1.5 to 9.4) |

4.9 (–1.4 to 11.2) |

.141 |

| P value | .004 | .134 | .124 | |||||||||

| KOOSSPORTS | ||||||||||||

| n | 62 | 33 | 65 | 34 | 62 | 31 | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 32.2 (25.5 to 38.8) |

23.8 (14.0 to 33.6) |

8.4 (–3.0 to 19.8) |

.767 | 30.7 (23.9 to 37.6) |

24.3 (13.6 to 35.0) |

6.4 (–5.7 to 18.5) |

.934 | –2.4 (–7.4 to 2.6) |

0.8 (–8.6 to 10.1) |

3.1 (–6.4 to 12.7) |

.372 |

| P value | .148 | .296 | .514 | |||||||||

| KOOSQoL | ||||||||||||

| n | 62 | 33 | 65 | 35 | 62 | 32 | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 33.1 (26.8 to 39.4) |

24.3 (16.2 to 32.4) |

8.8 (–1.6 to 19.2) |

.416 | 33.7 (27.3 to 40.1) |

27.1 (18.6 to 35.6) |

6.6 (–4.0 to 17.2) |

.816 | –3.2 (–8.0 to 1.6) |

0.2 (–6.7 to 7.1) |

3.4 (–4.8 to 11.6) |

.433 |

| P value | .095 | .217 | .409 | |||||||||

| EQ-5D | ||||||||||||

| n | 61 | 32 | 64 | 35 | 59 | 30 | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 0.24 (0.18 to 0.31) |

0.15 (0.08 to 0.22) |

0.10 (–0.01 to 0.20) |

.782 | 0.22 (0.14 to 0.29) |

0.17 (0.09 to 0.25) |

0.04 (–0.07 to 0.16) |

.313 | –0.03 (–0.08 to 0.01) |

0.05 (–0.03 to 0.13) |

0.08 (–0.00 to 0.17) |

.117 |

| P value | .076 | .433 | .062 | |||||||||

| EQ-VAS | ||||||||||||

| n | 60 | 31 | 63 | 33 | 59 | 30 | ||||||

| Mean (95% CI) | 15.8 (10.4 to 21.2) |

10.2 (4.3 to 16.2) |

5.6 (–3.0 to 14.2) |

.870 | 18.4 (13.8 to 23.1) |

16.7 (10.2 to 23.2) |

1.7 (–6.1 to 9.6) |

.479 | –0.1 (–4.3 to 4.0) |

4.5 (–0.0 to 9.0) |

4.6 (–2.0 to 11.2) |

.105 |

| P value | .199 | .663 | .169 | |||||||||

aBolded values indicate statistical significance (P < .05). ADL, activities of daily living; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5 dimensions; EQ-VAS, EuroQol visual analog scale; KOOS, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; QoL, quality of life.

bData from the cohort of patients who answered the questionnaire at baseline, the 1-year follow-up, and the 5-year follow-up.

cAdjusted for overall mean scores at baseline.

dAdjusted for overall mean scores at the 3-year follow-up.

Figure 2.

Mean Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)–Pain subscore at baseline, 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years according to treatment group.

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients in each treatment group who showed the indicated change in the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)–Pain subscore from baseline to 5 years. Dotted horizontal lines indicate a 10-point change from baseline.

There were no between-group differences from baseline to 5 years in the change in KOOS-symptoms (KOOSSYMPTOMS), KOOSSPORTS, KOOSADL, or KOOSQoL subscores (P > .05). The surgery group showed more improvement than the nonsurgery group on the KOOSADL from baseline to 1 year according to the unadjusted analysis (difference in mean change, 11.0 [95% CI, 3.5 to 18.4]; P = .004), but this difference was not significant in the adjusted model, with the baseline KOOSADL subscore as a covariate (adjusted P = .116). There were no between-group differences from baseline to 1 year in the change in any of the other KOOS subscores (P > .05) (Table 3). There were no between-group differences from baseline to 5 years or from baseline to 1 year in the change in the EQ-5D or EuroQol visual analog scale (EQ-VAS) scores (P > .05) (Table 3). There was a difference between groups in the change in the KOOSSYMPTOMS subscore from 3 to 5 years in favor of the nonsurgery group (difference in mean change, 7.9 [95% CI, 1.8 to 14.1]; P = .011; adjusted P = .008) (Table 3).

At the 5-year follow-up, the surgery group scored lower on the KOOSSYMPTOMS compared with the nonsurgery group (mean difference, –8.5 points [95% CI, –16.4 to –0.7]; P = .034). There were no between-group differences in any of the other KOOS subscores at 5 years (Table 2). At the 1-year follow-up, there were no between-group differences in any of the KOOS subscores (Table 2). There were no between-group differences in EQ-5D or EQ-VAS scores at either the 5- or 1-year follow-up (Table 2).

The 2-way ANCOVA on the change in the KOOSPAIN subscore at 5 years, after controlling for the effect of the KOOSPAIN at baseline, indicated that treatment had a nonsignificant main effect (P = .967), mechanical symptoms had a significant main effect (P = .026), and the interaction between treatment and mechanical symptoms had a significant effect (P = .020) (Table 4). Mechanical symptoms had an effect on the change in the KOOSPAIN subscore at 5 years but only in the surgery group; a significantly larger improvement was observed in patients without compared with those with mechanical symptoms (within-group mean difference, 18.4 [95% CI, 8.7 to 28.1]; P < .001) (Table 5). The 2-way ANCOVA on the change in the KOOSSYMPTOMS subscore at 5 years, after controlling for the effect of the KOOSSYMPTOMS at baseline, indicated that treatment had a nonsignificant main effect (P = .389), mechanical symptoms had a nonsignificant main effect (P = .279), and the interaction between treatment and mechanical symptoms had a significant effect (P = .040) (Table 4). Mechanical symptoms had an effect on the change in the KOOSSYMPTOMS subscore at 5 years but only in the surgery group; a significantly larger improvement was observed in patients without compared with those with mechanical symptoms (within-group mean difference, 12.1 [95% CI, 2.7 to 21.4]; P = .012) (Table 5). The 2-way ANCOVA on the change in the KOOSADL subscore at 5 years, after controlling for the effect of the KOOSADL at baseline, indicated that treatment had a nonsignificant main effect (P = .451), mechanical symptoms had a nonsignificant main effect (P = .100), and the interaction between treatment and mechanical symptoms had a significant effect (P = .019) (Table 4). The effect of mechanical symptoms on the change in the KOOSADL subscore at 5 years was only observed in the surgery group; a significantly larger improvement was observed in patients without compared to patients with mechanical symptoms (within-group mean difference, 14.2 [95% CI, 5.6 to 22.8]; P = .001) (Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Results of 2-Way Analyses of Covariancea

| df | F Value | P Value | Partial η2 Value | R 2 Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in KOOSPAIN as DV (n = 99) | 0.361 | ||||

| Treatment group | 1 | 0.002 | .967 | 0.000 | |

| Mechanical symptoms | 1 | 5.100 | .026 | 0.051 | |

| Treatment group × mechanical symptoms | 1 | 5.634 | .020 | 0.057 | |

| KOOSPAIN at baseline (covariate) | 1 | 31.713 | <.001 | 0.252 | |

| Change in KOOSSYMPTOMS as DV (n = 100) | 0.291 | ||||

| Treatment group | 1 | 0.749 | .389 | 0.008 | |

| Mechanical symptoms | 1 | 1.183 | .279 | 0.012 | |

| Treatment group × mechanical symptoms | 1 | 4.322 | .040 | 0.044 | |

| KOOSSYMPTOMS at baseline (covariate) | 1 | 30.708 | <.001 | 0.244 | |

| Change in KOOSADL as DV (n = 98) | 0.403 | ||||

| Treatment group | 1 | 0.572 | .451 | 0.006 | |

| Mechanical symptoms | 1 | 2.761 | .100 | 0.029 | |

| Treatment group × mechanical symptoms | 1 | 5.706 | .019 | 0.058 | |

| KOOSADL at baseline (covariate) | 1 | 38.440 | <.001 | 0.292 | |

| Change in KOOSSPORTS as DV (n = 98) | 0.154 | ||||

| Treatment group | 1 | 0.019 | .890 | 0.000 | |

| Mechanical symptoms | 1 | 2.123 | .148 | 0.022 | |

| Treatment group × mechanical symptoms | 1 | 0.487 | .487 | 0.005 | |

| KOOSSPORTS at baseline (covariate) | 1 | 11.143 | .001 | 0.107 | |

| Change in KOOSQoL as DV (n = 99) | 0.204 | ||||

| Treatment group | 1 | 0.346 | .558 | 0.004 | |

| Mechanical symptoms | 1 | 2.003 | .160 | 0.021 | |

| Treatment group × mechanical symptoms | 1 | 1.817 | .181 | 0.019 | |

| KOOSQoL at baseline (covariate) | 1 | 15.048 | <.001 | 0.138 | |

| Change in EQ-5D as DV (n = 98) | 0.554 | ||||

| Treatment group | 1 | 0.455 | .502 | 0.005 | |

| Mechanical symptoms | 1 | 0.312 | .578 | 0.003 | |

| Treatment group × mechanical symptoms | 1 | 0.839 | .362 | 0.009 | |

| EQ-5D at baseline (covariate) | 1 | 109.670 | <.001 | 0.541 | |

| Change in EQ-VAS as DV (n = 95) | 0.487 | ||||

| Treatment group | 1 | 0.155 | .695 | 0.002 | |

| Mechanical symptoms | 1 | 1.310 | .255 | 0.014 | |

| Treatment group × mechanical symptoms | 1 | 0.489 | .486 | 0.005 | |

| EQ-VAS at baseline (covariate) | 1 | 81.599 | <.001 | 0.476 |

aADL, activities of daily living; DV, dependent variable; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5 dimensions; EQ-VAS, EuroQol visual analog scale; KOOS, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; QoL, quality of life.

TABLE 5.

Change in Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Scores From Baseline to 5 Years by Mechanical Symptomsa

| Surgery | Nonsurgery | Between-Group Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KOOSPAIN | |||

| No mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 20 | 15 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 36.6 (28.4 to 44.7) | 26.9 (17.4 to 36.4) | 9.7 (–3.1 to 22.4) |

| P value | .136 | ||

| Mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 45 | 19 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 18.2 (12.8 to 23.5) | 27.5 (19.3 to 35.7) | –9.3 (–19.2 to 0.5) |

| P value | .063 | ||

| Within-group difference | |||

| Mean (95% CI) | 18.4 (8.7 to 28.1) | –0.6 (–13.0 to 11.9) | |

| P value | <.001 | .925 | |

| KOOSSYMPTOMS | |||

| No mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 19 | 16 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 25.1 (17.3 to 33.0) | 20.6 (11.7 to 29.4) | 4.6 (–7.2 to 16.4) |

| P value | .445 | ||

| Mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 46 | 19 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 13.1 (8.0 to 18.2) | 24.2 (16.4 to 32.1) | –11.1 (–20.5 to –1.8) |

| P value | .020 | ||

| Within-group difference | |||

| Mean (95% CI) | 12.1 (2.7 to 21.4) | –3.6 (–15.6 to 8.3) | |

| P value | .012 | .545 | |

| KOOSADL | |||

| No mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 20 | 16 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 28.3 (21.1 to 35.5) | 17.1 (9.0 to 25.2) | 11.2 (0.1 to 22.3) |

| P value | .049 | ||

| Mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 44 | 18 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 14.1 (9.4 to 18.8) | 19.8 (12.4 to 27.2) | –5.7 (–14.5 to 3.1) |

| P value | .199 | ||

| Within-group difference | |||

| Mean (95% CI) | 14.2 (5.6 to 22.8) | –2.7 (–13.6 to 8.2) | |

| P value | .001 | .622 | |

| KOOSSPORTS | |||

| No mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 20 | 14 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 37.6 (25.5 to 49.8) | 32.4 (17.0 to 47.8) | 5.2 (–15.1 to 25.5) |

| P value | .611 | ||

| Mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 45 | 19 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 24.5 (16.5 to 32.5) | 27.9 (15.7 to 40.2) | –3.4 (–18.1 to 11.2) |

| P value | .641 | ||

| Within-group difference | |||

| Mean (95% CI) | 13.1 (–1.3 to 27.6) | 4.5 (–15.2 to 24.1) | |

| P value | .073 | .652 | |

| KOOSQoL | |||

| No mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 20 | 15 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 41.6 (31.1 to 51.1) | 31.5 (19.0 to 43.9) | 10.2 (–6.5 to 26.8) |

| P value | .229 | ||

| Mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 45 | 19 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 27.4 (20.5 to 34.3) | 31.3 (20.6 to 41.9) | –3.9 (–16.6 to 8.8) |

| P value | .547 | ||

| Within-group difference | |||

| Mean (95% CI) | 14.2 (1.8 to 26.7) | 0.2 (–16.0 to 16.5) | |

| P value | .026 | .978 | |

| EQ-5D | |||

| No mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 19 | 15 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 0.23 (0.15 to 0.31) | 0.22 (0.13 to 0.32) | 0.01 (–0.12 to 0.14) |

| P value | .886 | ||

| Mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 45 | 19 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 0.17 (0.12 to 0.23) | 0.24 (0.15 to 0.32) | –0.07 (–0.17 to 0.04) |

| P value | .201 | ||

| Within-group difference | |||

| Mean (95% CI) | 0.06 (–0.04 to 0.16) | –0.02 (–0.14 to 0.11) | |

| P value | .239 | .819 | |

| EQ-VAS | |||

| No mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 19 | 14 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 21.2 (15.1 to 27.3) | 20.3 (13.2 to 27.4) | 0.9 (–8.5 to 10.3) |

| P value | .846 | ||

| Mechanical symptoms | |||

| n | 44 | 18 | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 15.6 (11.6 to 19.6) | 18.9 (12.6 to 25.3) | –3.3 (–10.8 to 4.2) |

| P value | .385 | ||

| Within-group difference | |||

| Mean (95% CI) | 5.6 (–1.7 to 12.9) | 1.3 (–8.2 to 10.9) | |

| P value | .133 | .779 |

aBolded values indicate statistical significance (P < .05). Adjusted for overall mean scores at baseline. ADL, activities of daily living; EQ-5D, EuroQol 5 dimensions; EQ-VAS, EuroQol visual analog scale; KOOS, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; QoL, quality of life.

At the 5-year follow-up, a moderate to high level of physical activity was reported by a lower proportion of the surgery group compared with the nonsurgery group (41% vs 66%, respectively; P = .018). None of the groups showed a significant change in physical activity level from baseline to 5 years (surgery, P = .481; nonsurgery, P = .057).

Radiographic Findings

At the 5-year follow-up, 78% of patients in both the surgery and nonsurgery groups displayed radiographic OA (P = .967). Among the 64 patients who had no available radiographs at the 5-year follow-up, 22 patients (10 patients in the surgery group and 12 patients in the nonsurgery group) had grade ≥2 OA, according to the Kellgren-Lawrence grade, at baseline. From baseline to the 5-year follow-up, radiographic deterioration, assessed according to the Kellgren-Lawrence grade, occurred in 60% of the surgery group and 37% of the nonsurgery group. The difference between groups was nonsignificant (P = .060).

Response and Dropout Analysis

Of the 146 patients available for the as-treated analysis, 44 (30%) did not respond to the questionnaire at 5 years, including 19 patients (22%) in the surgery group and 25 (41%) in the nonsurgery group (P = .016). Of the 44 nonresponders, 2 had died and 14 had declined further participation. There was no significant difference between responders and nonresponders regarding sex, age, duration of knee pain, knee function, mechanical symptoms, or radiographic OA at baseline (P > .05). The response rate at 5 years was higher among patients with moderate to high levels compared with those with low levels of physical activity at baseline (83% vs 66%, respectively; P = .037). There was no significant difference between responders and nonresponders in any of the KOOS subscores, the EQ-5D score, or the EQ-VAS score at baseline (P > .05).

Of the 28 patients eligible for dropout analysis, 24 could be reached, and all agreed to participate in a short telephone interview. Knee surgery was performed in 25% of patients who discontinued study participation and 64% of patients who completed study participation (P = .004). These groups were not significantly different in knee pain, knee function, or physical activity level at 5 years (P > .05).

Discussion

The present 5-year follow-up of a randomized study on knee arthroscopic surgery and an exercise program versus only an exercise program in middle-aged patients with meniscal symptoms showed no differences between groups from baseline to 5 years in the changes in the KOOSPAIN subscore or on knee joint radiographs. At the 1-year follow-up, knee arthroscopic surgery provided more benefit compared with no surgery; surgery provided a larger reduction in pain from baseline to 3 months and 1 year.15 This superior improvement in the primary outcome (KOOSPAIN) did not persist at the 3-year follow-up in the surgery group14 but persisted in patients who had no mechanical symptoms at baseline.14 The present study showed that, at the 5-year follow-up, even in this subgroup, the positive effect of knee arthroscopic surgery was no longer significant. These results were consistent with a previous systematic review on arthroscopic surgery for the degenerative knee; in that review, they concluded that surgery provided a short-term benefit (up to 6 months) but no benefit after 1 year or longer.52

The potential beneficial effects of knee arthroscopic surgery must be weighed against short-term adverse effects, such as postoperative infections or deep venous thrombosis,52 and long-term negative effects, such as an increased risk of posttraumatic OA.6,13 The present study found no short-term complications, consistent with previous studies in which postoperative complications were rare.5,16,52 However, meniscal tissue resection leads to altered knee joint loading, which increases the contact pressure on the remaining tissues in the joint.4,51 Therefore, meniscectomy might increase the risk of subsequent cartilage injuries.10,37,39,40

The indication for surgery might be a potential confounding factor40 because underlying degenerative joint disease increases the risk of future cartilage degradation. In the present study, radiographic deterioration was not significantly different between the surgery and nonsurgery groups; however, we observed a tendency to detect radiographic deterioration in a larger proportion of patients in the surgery group compared with the nonsurgery group. Nevertheless, an equal proportion in both groups had radiographic OA at the 5-year follow-up. Previous RCTs found a similar result regarding radiographic deterioration between surgery and nonsurgery groups.19,55 In the present study, only 1 patient in each group reported that knee pain worsened by more than 10 points on the KOOSPAIN at 5 years. The low proportions of patients (<5%) and the equivalent incidence between groups suggested that meniscectomy did not increase the risk of clinical deterioration at 5 years.

For many years, arthroscopic meniscal surgery has been a common procedure9,50; nevertheless, its use in treating degenerative meniscal injuries in middle-aged patients has been challenged.7,8,31,38 Consequently, the rates of arthroscopic meniscal procedures have declined in recent years.34,36 Recently, a clinical guideline for degenerative knee disease and meniscal tears strongly recommended against arthroscopic surgery in nearly all patients with degenerative knee disease.45 Therefore, nonsurgical treatment should be the first-line treatment3,29; indeed, in the present study, prior physical therapy was an inclusion criterion. Exercise therapy and meniscectomy were shown to be equally effective in reducing knee pain and increasing function and performance in patients with degenerative meniscal injuries. In addition, exercise is more effective than surgery for increasing muscle strength.49 The mechanisms underlying the effects of exercise interventions include increased muscle strength, enhanced proprioception, and improved range of motion.43 When the effects of nonsurgical treatment are unsatisfactory, arthroscopic partial meniscectomy can be considered3,29,33 because some subgroups of patients are known to benefit from arthroscopic surgery.21 It remains a challenge in clinical decision making to identify which subgroups of patients with degenerative meniscal injuries are most likely to benefit from knee arthroscopic surgery. Ideally, surgical decision making should be individualized.28 A recent systematic review concluded that long symptom duration, radiological evidence of knee OA, and resection of >50% of the meniscus were prognostic factors associated with a worse clinical outcome from meniscectomy.11 In the present study, patients with preoperative self-reported mechanical symptoms had worse outcomes from knee arthroscopic surgery than patients without these symptoms. This finding was clinically important because mechanical symptoms have been considered a valid indication for arthroscopic surgery in patients with degenerative knee disease.20,32 Our results were consistent with a recent study that found that, among patients with degenerative knees, mechanical symptoms were associated with a less favorable outcome from knee arthroscopic surgery.46 A plausible interpretation of these findings could be that mechanical symptoms indicate general knee degeneration rather than an isolated meniscal injury.17,46 It should be noted that the present study did not include patients with meniscal root tears that were repaired.

This study has some important strengths, including our evaluations of both PROMs and radiographic findings during the 5-year follow-up. Previous RCTs had only at most 2-year follow-up times,23,26,27,35,47,55 with the exception of 2 studies with a 5-year follow-up.19 When patients are followed for at least 5 years, it is vital to anticipate the possibility that OA might develop. However, most RCTs evaluated only PROMs that focused on pain and function; only 2 previous RCTs have reported radiographic findings.19,55 In addition, the present study has the following strengths: strict inclusion criteria, a single-center study with access to a majority of the population, the characteristics of the health care system within the catchment area were known and described, exercise instructions were administered by physical therapists experienced in knee rehabilitation, and almost all eligible patients agreed to participate in the study.33 Furthermore, at baseline, the allocation sequence was concealed from the orthopaedic surgeon who enrolled and assessed patients. In addition, 1 radiologist, who was blinded to the allocation and treatment, assessed all the radiographs both at baseline and at the 5-year follow-up. Thus, the enrolling orthopaedic surgeon and the radiologist were blinded to the treatment groups.

This study also has several limitations. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. First, the patients were not blinded to the treatment. Moreover, 25% of patients in the nonsurgery group crossed over to undergo surgery, and 11% crossed over in the other direction. The as-treated analysis was used to analyze the effect of the treatment. There were significant differences in KOOS subscores between groups at baseline: the surgery group had more pain and worse function than the nonsurgery group. Presumably, patients with worse symptoms were more likely to undergo surgery. However, although group differences were significant, they were small, and they only reached clinical significance on the KOOSSPORTS. Furthermore, only 70% of patients completed the 5-year questionnaire. There were lower response rates in the nonsurgery group that may have affected the results. Nevertheless, the dropout analysis showed that the nonresponders did not differ from participants regarding knee pain, knee function, and physical activity level at 5 years.

In conclusion, knee arthroscopic surgery combined with an exercise program provided no additional long-term benefit after 5 years compared with an exercise program alone in middle-aged patients with meniscal symptoms. Patients without mechanical symptoms experienced better surgical outcomes than those with mechanical symptoms. Radiographic evidence of bone changes showed no difference between treatment groups.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the orthopaedic surgeons Magnus Lundberg and Jonas Holmertz at Medicinskt Centrum, Linköping, for performing the arthroscopic procedures. They also thank the physical therapists Johan Carlsson, Peter Edenholm, Marcus Egelstig, and Marie Ryding-Ederö at Linköping Health Care for performing the physical therapy assessments. They thank the physical therapist Frida Andersson for performing the dropout analysis.

Footnotes

Final revision submitted November 4, 2019; accepted November 11, 2020.

The authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the ethics committee at Linköping University (dnr: 2010/6-31).

References

- 1. Ahlback S. Osteoarthrosis of the knee: a radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh). 1968:(suppl 277):7–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Azam M, Shenoy R. The role of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in the management of degenerative meniscus tears: a review of the recent literature. Open Orthop J. 2016;10:797–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beaufils P, Becker R, Kopf S, et al. Surgical management of degenerative meniscus lesions: the 2016 ESSKA meniscus consensus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(2):335–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bedi A, Kelly NH, Baad M, et al. Dynamic contact mechanics of the medial meniscus as a function of radial tear, repair, and partial meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(6):1398–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brignardello-Petersen R, Guyatt GH, Buchbinder R, et al. Knee arthroscopy versus conservative management in patients with degenerative knee disease: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e016114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brophy RH, Gray BL, Nunley RM, Barrack RL, Clohisy JC. Total knee arthroplasty after previous knee surgery: expected interval and the effect on patient age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(10):801–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buchbinder R. Meniscectomy in patients with knee osteoarthritis and a meniscal tear? N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1740–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carr A. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee. BMJ. 2015;350:H2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009;11:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eichinger M, Schocke M, Hoser C, Fink C, Mayr R, Rosenberger RE. Changes in articular cartilage following arthroscopic partial medial meniscectomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(5):1440–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eijgenraam SM, Reijman M, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, van Yperen DT, Meuffels DE. Can we predict the clinical outcome of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(8):514–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Englund M, Guermazi A, Gale D, et al. Incidental meniscal findings on knee MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(11):1108–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Englund M, Roemer FW, Hayashi D, Crema MD, Guermazi A. Meniscus pathology, osteoarthritis and the treatment controversy. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8(7):412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gauffin H, Sonesson S, Meunier A, Magnusson H, Kvist J. Knee arthroscopic surgery in middle-aged patients with meniscal symptoms: a 3-year follow-up of a prospective, randomized study. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(9):2077–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gauffin H, Tagesson S, Meunier A, Magnusson H, Kvist J. Knee arthroscopic surgery is beneficial to middle-aged patients with meniscal symptoms: a prospective, randomised, single-blinded study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(11):1808–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hame SL, Nguyen V, Ellerman J, Ngo SS, Wang JC, Gamradt SC. Complications of arthroscopic meniscectomy in the older population. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(6):1402–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hare KB, Stefan Lohmander L, Kise NJ, Risberg MA, Roos EM. Middle-aged patients with an MRI-verified medial meniscal tear report symptoms commonly associated with knee osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop. 2017;88(6):664–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Herrlin S, Hallander M, Wange P, Weidenhielm L, Werner S. Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(4):393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Herrlin SV, Wange PO, Lapidus G, Hallander M, Werner S, Weidenhielm L. Is arthroscopic surgery beneficial in treating non-traumatic, degenerative medial meniscal tears? A five year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(2):358–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jevsevar DS, Yates AJ, Jr, Sanders JO. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karpinski K, Muller-Rath R, Niemeyer P, Angele P, Petersen W. Subgroups of patients with osteoarthritis and medial meniscus tear or crystal arthropathy benefit from arthroscopic treatment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(3):782–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1675–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Katz JN, Losina E. Surgery versus physical therapy for meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(7):677–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Katz JN, Shrestha S, Losina E, et al. Five-year outcome of operative and non-operative management of meniscal tear in persons greater than 45 years old [published online August 20, 2019]. Arthritis Rheumatol. doi:10.1002/art.41082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16(4):494–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(11):1097–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kise NJ, Risberg MA, Stensrud S, Ranstam J, Engebretsen L, Roos EM. Exercise therapy versus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tear in middle aged patients: randomised controlled trial with two year follow-up. BMJ. 2016;354:i3740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krych AJ, Stuart MJ, Levy BA. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lamplot JD, Brophy RH. The role for arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in knees with degenerative changes: a systematic review. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(7):934–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Losina E, Dervan EE, Paltiel AD, et al. Defining the value of future research to identify the preferred treatment of meniscal tear in the presence of knee osteoarthritis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lubowitz JH, Provencher MT, Rossi MJ. Could the New England Journal of Medicine be biased against arthroscopic knee surgery? Part 2. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):654–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lyman S, Oh LS, Reinhardt KR, et al. Surgical decision making for arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in patients aged over 40 years. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(4):492–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Malmivaara A. Validity and generalizability of findings of randomized controlled trials on arthroscopic partial meniscectomy of the knee. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018;28(9):1970–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mattila VM, Sihvonen R, Paloneva J, Fellander-Tsai L. Changes in rates of arthroscopy due to degenerative knee disease and traumatic meniscal tears in Finland and Sweden. Acta Orthop. 2016;87(1):5–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moseley JB, O’Malley K, Petersen NJ, et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(2):81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Parker BR, Hurwitz S, Spang J, Creighton R, Kamath G. Surgical trends in the treatment of meniscal tears: analysis of data from the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery certification examination database. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(7):1717–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Petty CA, Lubowitz JH. Does arthroscopic partial meniscectomy result in knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review with a minimum of 8 years’ follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(3):419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Price A, Beard D. Arthroscopy for degenerate meniscal tears of the knee. BMJ. 2014;348:G2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roemer FW, Kwoh CK, Hannon MJ, et al. Partial meniscectomy is associated with increased risk of incident radiographic osteoarthritis and worsening cartilage damage in the following year. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(1):404–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rongen JJ, Rovers MM, van Tienen TG, Buma P, Hannink G. Increased risk for knee replacement surgery after arthroscopic surgery for degenerative meniscal tears: a multi-center longitudinal observational study using data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(1):23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Roos EM, Hare KB, Nielsen SM, Christensen R, Lohmander LS. Better outcome from arthroscopic partial meniscectomy than skin incisions only? A sham-controlled randomised trial in patients aged 35-55 years with knee pain and an MRI-verified meniscal tear. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e01946 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Roos EM, Lohmander LS. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Runhaar J, Luijsterburg P, Dekker J, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Identifying potential working mechanisms behind the positive effects of exercise therapy on pain and function in osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(7):1071–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schiphof D, Oei EH, Hofman A, Waarsing JH, Weinans H, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Sensitivity and associations with pain and body weight of an MRI definition of knee osteoarthritis compared with radiographic Kellgren and Lawrence criteria: a population-based study in middle-aged females. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(3):440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Siemieniuk RAC, Harris IA, Agoritsas T, et al. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee arthritis and meniscal tears: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2017;357:J1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sihvonen R, Englund M, Turkiewicz A, Jarvinen TL. Mechanical symptoms as an indication for knee arthroscopy in patients with degenerative meniscus tear: a prospective cohort study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(8):1367–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus placebo surgery for a degenerative meniscus tear: a 2-year follow-up of the randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(2):188–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2515–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Swart NM, van Oudenaarde K, Reijnierse M, et al. Effectiveness of exercise therapy for meniscal lesions in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19(12):990–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thorlund JB, Hare KB, Lohmander LS. Large increase in arthroscopic meniscus surgery in the middle-aged and older population in Denmark from 2000 to 2011. Acta Orthop. 2014;85(3):287–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thorlund JB, Holsgaard-Larsen A, Creaby MW, et al. Changes in knee joint load indices from before to 12 months after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: a prospective cohort study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(7):1153–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Thorlund JB, Juhl CB, Roos EM, Lohmander LS. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee: systematic review and meta-analysis of benefits and harms. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(19):1229–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. van de Graaf VA, Noorduyn JCA, Willigenburg NW, et al. Effect of early surgery vs physical therapy on knee function among patients with nonobstructive meniscal tears: the ESCAPE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1328–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. van de Graaf VA, Wolterbeek N, Mutsaerts EL, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy or conservative treatment for nonobstructive meniscal tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(9):1855–1865. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yim JH, Seon JK, Song EK, et al. A comparative study of meniscectomy and nonoperative treatment for degenerative horizontal tears of the medial meniscus. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1565–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]